Abstract

Although telomere-binding proteins constitute an essential part of telomeres, in vivo data indicating the existence of a structure similar to mammalian shelterin complex in plants are limited. Partial characterization of a number of candidate proteins has not identified true components of plant shelterin or elucidated their functional mechanisms. Telomere repeat binding (TRB) proteins from Arabidopsis thaliana bind plant telomeric repeats through a Myb domain of the telobox type in vitro, and have been shown to interact with POT1b (Protection of telomeres 1). Here we demonstrate co-localization of TRB1 protein with telomeres in situ using fluorescence microscopy, as well as in vivo interaction using chromatin immunoprecipitation. Classification of the TRB1 protein as a component of plant telomeres is further confirmed by the observation of shortening of telomeres in knockout mutants of the trb1 gene. Moreover, TRB proteins physically interact with plant telomerase catalytic subunits. These findings integrate TRB proteins into the telomeric interactome of A. thaliana.

Keywords: telomerase, telomere, telomere repeat binding (TRB), Arabidopsis thaliana, telomere protein interaction, plant shelterin

Introduction

Telomeres, nucleoprotein structures that form and protect the ends of chromosomes, have been the subject of intense studies for about three decades, starting with a description of the telomere DNA component (Blackburn and Gall, 1978) and the most common system of telomere maintenance by the ribonucleoprotein complex of telomerase (Greider and Blackburn, 1985, 1989). Proteins essential for telomere functions have been described in detail in yeasts and vertebrates. Among protein components of telomeres, the most important is indisputably telomerase itself, but other proteins are necessary to perform other functions of telomeres, such as inhibiting the DNA damage response at telomeres (de Lange, 2009), recruiting telomerase to chromosome ends (Nandakumar et al., 2012), or facilitating telomere replication (Sfeir et al., 2009). Current evidence suggests that these components assemble into two distinct complexes known as shelterin (de Lange, 2005) and CST (composed of CTC1/STN1/TEN1 proteins) complexes (Surovtseva et al., 2009).

Human shelterin consists of six core components: telomeric repeat-binding factor 1 (TRF1), telomeric repeat-binding factor 2 (TRF2), represor/activator protein 1 (RAP1), TRF1-interacting protein (TIN2), TINT1/PIP1/PTOP1 (TPP1), protection of telomeres 1 (POT1). TRF1 and TRF2 anchor the complex to double-stranded telomeric DNA using a specific Myb-like motif termed a telobox (Bilaud et al., 1996), and recruit two other shelterin components, RAP1 and TIN2, to the telomeres. TIN2 further interacts with TPP1 protein, which binds the final shelterin component, POT1. POT1 also binds the G–rich strand of telomeric DNA from either the single-stranded G–overhang or displacement loop (D–loop). In this way, shelterin may bridge the double- and single-stranded parts of telomeric DNA.

The CST complex, consisting of three components (Cdc13, Stn1 and Ten1), was originally described in yeast (Gao et al., 2007) as a telomere-specific replication protein A-like complex that protects single-stranded chromosome termini and regulates telomere replication. Subsequent studies have shown that a CST-like complex also exists in plants and humans and contributes to telomere protection and replication (Surovtseva et al., 2009; Price et al., 2010). According to recent studies, both complexes participate in telomere capping, telomerase regulation and 3′ overhang formation (Giraud-Panis et al., 2010; Pinto et al., 2011; Chen et al., 2012; Wu et al., 2012).

In contrast to the CST complex, no functional and structural equivalent of shelterin has been found in plants. Although many putative shelterin-like protein components have been found in plants (Peska et al., 2011), including those bearing a telobox Myb-like domain at their C–terminus (Hwang et al., 2001, 2005; Karamysheva et al., 2004) or N–terminus (Marian et al., 2003; Schrumpfova et al., 2004), as well as POT1 homologues (Baumann et al., 2002; Kuchar and Fajkus, 2004; Shakirov et al., 2005; Tani and Murata, 2005; Peska et al., 2008), none of these have been shown to specifically associate with telomeres in situ or in vivo.

Molecular components responsible for reversible telomerase regulation in plant cells (Fajkus et al., 1998; Riha et al., 1998) are an attractive target for possible biomedical applications of telomere biology, and are sought primarily at the levels of protein components of plant telomeres, and regulation of the basic telomerase subunits TERT (telomerase reverse transcriptase) and TER (telomerase RNA).

In this study, we investigated the interactions and roles of Single myb histone (Smh) proteins at plant telomeres. Five members of the Smh family are encoded by the A. thaliana genome (TRB1–5). These proteins are specific to plants, and consist of an N–terminal Myb-like domain of the telobox type, which is responsible for specific recognition of double/single-stranded telomeric DNA (Schrumpfova et al., 2004; Hofr et al., 2009), a central histone-like domain, which is involved in non-specific DNA–protein interactions and mediates protein–protein interactions, including formation of homo- and heteromeric complexes of TRB proteins (Mozgova et al., 2008), and a C–terminal coiled-coil domain to which no specific function has yet been attributed. We previously reported that TRB proteins interact via their histone-like domain with POT1b, an A. thaliana homologue of the G–overhang binding protein POT1 (Kuchar and Fajkus, 2004; Schrumpfova et al., 2008; Rotkova et al., 2009). In addition, POT1b also associates with an alternative telomerase nucleoprotein complex in Arabidopsis (Surovtseva et al., 2007; Cifuentes-Rojas et al., 2012). We have previously shown that TRB1 is localized in the nucleus and nucleolus in vivo and shows highly dynamic association with chromatin (Dvorackova et al., 2010). Together, these findings indicate that TRB proteins are promising candidates for plant shelterin-like components.

Here we demonstrate that TRB proteins act as components of a plant telomere-protection complex. Microscopic and chromatin immunoprecipitation techniques showed co-localization of TRB1 with telomeric tracts in vivo and physical interaction of TRB proteins with the N–terminal part of the catalytic subunit of telomerase. In addition, loss of TRB1 protein leads to telomere shortening.

Results

TRB1 co-localizes with telomeres

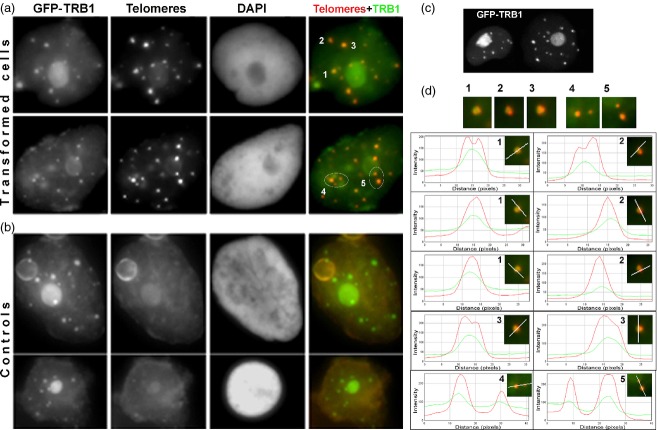

Although a possible association of GFP–TRB1 (35Spro:GFP-TRB1) with the telomere was suggested previously (Dvorackova et al., 2010), whether the nuclear speckles are directly associated with telomeres remained to be determined.

Here, we took advantage of the well-established protocol of Nicotiana benthamiana leaf infiltration and the fact that N. benthamiana has longer telomeres that are easier to visualize compared to Arabidopsis.

As shown in Figure1(c), the localization of transiently transformed TRB1 in N. benthamiana leaf is similar to that observed in Arabidopsis cell cultures, as was shown by Dvorackova et al. (2010), labelling the whole nucleus, with strong nucleolar signal and relatively strong nuclear speckles. Nuclei from transformed leaves were isolated and used for telomere peptide nucleic acid FISH. Fluorescence from GFP–TRB1 remained very bright during the isolation procedure; however, a gentle denaturation step was necessary during the FISH protocol to preserve the integrity of the GFP signal. These FISH results showed that telomeres co-localize or associate with TRB1 speckles in 59% and 31% of cases, respectively, with 90% association overall (Figure1 and Table S1). Telomeric signals sometimes appeared as double dots connected to the TRB1 foci (Figure1d, images 1, 2 and 3), but in other cases co-localize directly with TRB1 (Figure1d, images 4 and 5). These results provide in situ evidence of telomere occupancy by TRB1.

Figure 1.

Co-localization of TRB protein with telomeric probe.Nuclei isolated from N. benthamiana were transformed with 35Spro:GFP-TRB1 construct and hybridized with telomeric peptide nucleic acid (PNA) Cy3-labelled probe.(a) Co-localization between GFP–TRB1 nuclear speckles (green) and telomeric PNA probe (red) is detectable in most of the foci.(b) Control experiment without telomeric probe showing very little background present in the red channel.(c) Confocal image of GFP–TRB1 expression in an N. benthamiana leaf without any further sample processing.(d) Details of co-localizing speckles; ImageJ (http://rsbweb.nih.gov/ij/) was used to create intensity plots for red and green channels.

TRB1 is associated with telomeric sequence in vivo

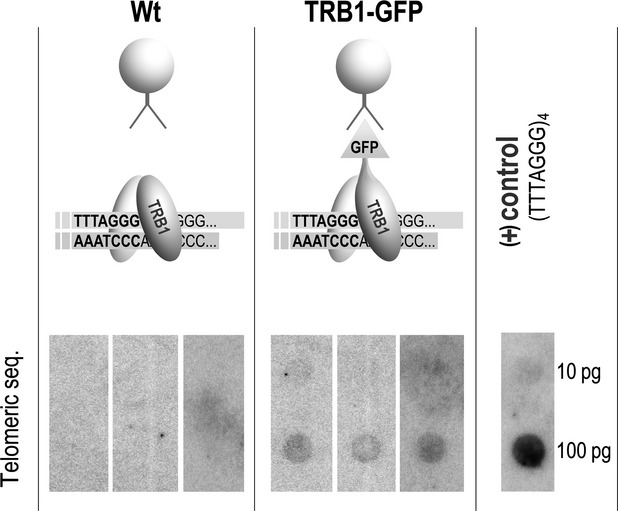

The observed co-localization of TRB1 with telomeric tracts, together with our previous detailed analyses of TRB1 binding to telomeric DNA in vitro (Schrumpfova et al., 2004; Hofr et al., 2009), suggest the possibility that TRB1 protein directly recognizes telomeric repeats and belongs to the core components that shelter telomeres. We used a chromatin immunoprecipitation assay to isolate DNA sequences associated with TRB1 protein. As source material, we used formaldehyde cross-linked seedlings of Arabidopsis plants stably transformed with a TRB1–GFP construct driven by the native promoter (TRB1pro:TRB1-GFP) (Dvorackova et al., 2010). Despite using the native promoter, enhanced levels of TRB1–GFP protein were observed (see below). TRB1–GFP protein was immunoprecipitated from purified nuclei using GFP-Trap A matrix, which contains a single variable antibody domain that recognizes GFP. Non-specific binding of TRB1-GFP to the GFP-Trap A matrix was excluded by precise detection of GFP in all fractions (input, bound, unbound, wash, elution). We have shown that TRB1, but not TRB1-GFP is washed out (Figure S1). DNA co-purifying with TRB1–GFP was dot-blotted onto nylon membranes, and visualized by hybridization with radioactively labelled telomeric probe. Figure2 shows that TRB1 protein is indeed associated with telomeric sequence in vivo, as telomeric sequence was repeatedly detected in TRB1–GFP but not wild-type samples. To demonstrate that the observed enrichment is indeed due to sequence-specific association and not due to the high copy number of the telomeric DNA, we hybridized DNA co-purified with TRB–GFP with a centromeric probe. As our previous results (Dvorackova et al., 2010) showed localization of TRB1 protein in the nucleus and nucleolus, another candidate sequence investigated for association with TRB1 was ribosomal DNA (rDNA). Only negligible enrichment of the centromeric or 18S rDNA probe, in contrast to significant enrichment of the telomeric probe, was observed when comparing each wild-type to TRB–GFP sample (Figure S2).

Figure 2.

TRB1 proteins are associated with telomeric sequence in vivo.DNA cross-linked with TRB1 protein was isolated by ChIP analysis using GFP-Trap A matrix from wild-type (Wt) and TRB1pro:TRB1-GFP plants. Hybridization of isolated DNA with radioactively labelled telomeric oligonucleotide (CCCTAAA)4 in three biologically and technically replicated experiments confirmed the hypothesis that TRB1 protein is associated with telomeric sequence in vivo. As a control, telomeric oligonucleotide (TTTAGGG)4 was dot-blotted on the same membrane and visualized together with immunoprecipitated DNA.

Analysis of TRB1 expression in trb1 mutant, wild-type and TRB1pro:TRB1-GFP-transformed plants

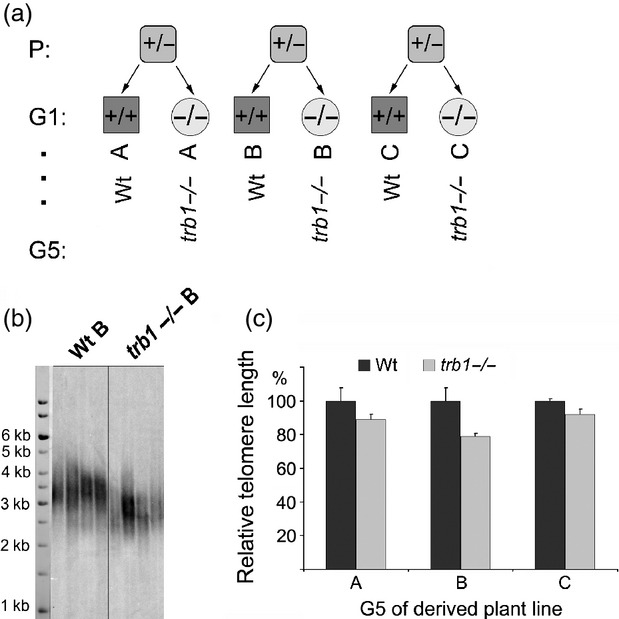

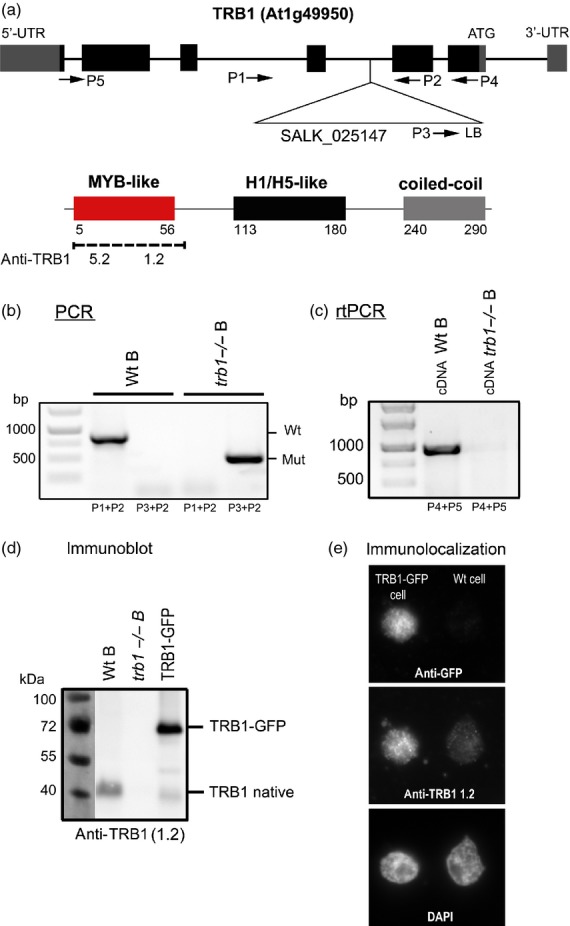

To examine the role of TRB1 in planta, we analysed T–DNA insertion line SALK_025147 (ecotype Col–0). Three parallel wild-type (wild-type) and homozygous trb1 (trb1−/−) lines (A, B and C) were derived from three independent heterozygous plants (see Figure4a). The homozygosity of each parallel wild-type and trb1 mutant plant line was determined by PCR (Figure3b). The T–DNA insertion is located in the second intron (Figure3a), and the absence of trb1 transcript was confirmed by RT–PCR (Figure3c).

Figure 4.

The telomeres are shortened in all three individually derived trb1−/− mutant plant lines.(a) Derivation of three independent plant lines (A, B, C) that were propagated for five generations (G5).(b) Terminal restriction fragment analysis, showing telomere shortening in the trb1−/− mutant line compared with the wild-type control in the fifth generation.(c) Difference in mutant trb1−/− and wild-type telomere lengths in three independent plant lines. Error bars represent standard deviation.

Figure 3.

Expression analysis of TRB1 protein in mutant (trb1−/−), wild-type (Wt) and transformed TRB1pro:TRB1-GFP plants.(a) Schematic illustration of specific primers and T–DNA insertion location within the trb1 gene. The domain location and antibody recognition sites for two specific antibodies developed in our laboratory are shown below.(b) Three individual plant lines (A, B and C) were derived from heterozygous progenitors (as shown in Figure4a). Example of PCR analysis of genomic DNA isolated from Wt plants (primers P3 + P2) and mutant (trb1−/−) plants (primers P1 + P2) of line B.(c) RT–PCR of RNA isolated from Wt and mutant (trb1−/−) plants of line B using primers P4 + P5.(d) Immunodetection by Western blot analysis of TRB1 protein in Wt and mutant (trb1−/−) plants of line B and TRB1pro:TRB1-GFP plant nuclear extracts using specific antibody recognizing the Myb-like domain of TRB1 (anti-TRB1 1.2). The level of native TRB1 protein is lower compared to the TRB1–GFP fusion protein construct expressed under the control of the native promoter.(e) Immunolocalization of TRB1 protein using anti-GFP and anti-TRB1 antibody. The level of native TRB1 protein in the wild-type is very low. The selected plant line does not show GFP labelling in all cells, so some nuclei contain a wild-type level of TRB1 and others show higher expression due to TRB1–GFP. Thus the intensity of signal may be clearly measured as Wt and over-expressing nuclei are present together on one slide and may be clearly distinguished using specific anti-TRB1 protein antibody 1.2 and anti-GFP antibody.

TRB proteins consist of three domains: Myb-like, histone-like and a coiled-coil domain (Figure3a). As no antibody recognizing either TRB proteins or the plant Myb domain of the telobox type is commercially available, we developed specific mouse monoclonal antibodies in our laboratory. Two of them were used in this study: 1.2 (specific to TRB1) and 5.2 (specific for the conservative part of the Myb domain; this also recognizes other TRB proteins). The location of antibody recognition sites within the structure of TRB1 as determined by ELISA (Figure S3) is shown in Figure3(a). Although the conservative part of the telobox Myb domain is also present in Arabidopsis TRF-like family (TRFL) proteins (Karamysheva et al., 2004), these proteins are not recognized by the 1.2 or 5.2 antibodies. The anti-TRB 1.2 or 5.2 antibodies were unable to detect in vitro expressed TRFL2 or 9 or TRP1 (telomeric repeat binding protein 1) from the TRFL family (Figure S4, constructs kindly provided by D.E. Shippen, Department of Biochemistry,Texas A&M University,TX, USA).

Antibody 1.2 was used to detect native TRB1 protein in Arabidopsis plant protein extracts. The natural level of TRB1 protein was clearly observed on Western blots of wild-type plants (Figure3d), but no TRB1 protein was observed for extracts from trb1 mutant plants (Figure3d). In addition, plant lines stably transformed with TRB1–GFP construct under the control of native promoter showed a distinct abundance of TRB1–GFP protein compared to the native TRB1 protein. Various expression levels of native TRB1 protein and TRB1–GFP were also apparent after immunolocalization in vivo (Figure3e), in which TRB1 protein is visualized using either anti-TRB1 1.2 antibody or anti-GFP antibody.

We tested both antibodies by indirect immunofluorescence on trb1 mutant and GFP–TRB1-expressing plants. These experiments showed evenly distributed nuclear and nucleolar signals for both 1.2 and 5.2 antibodies. Antibody 1.2 did not detect any signal in trb1−/− plants, but antibody 5.2 recognizes some epitopes in trb1−/− (Figure S5). However, the generated antibodies do not appear to be of sufficient quality for more demanding immunolocalization or ChIP experiments (as concluded from further testing).

Telomere shortening in trb1 null mutant plants

Derivation of independent wild-type and trb1−/− plant lines from three heterozygous progeny (Figure4a) provided reliable material for phenotypic studies of the trb1 null mutation effect. All six homozygous plant lines were propagated for five generations.

Obvious shortening of telomeres was observed by terminal restriction fragment (TRF) analysis in all three trb1 mutant lines analysed in the fifth generation compared to their segregated wild-type siblings. Hybridization with a radioactively labelled telomeric probe (Figure4b) revealed truncation of telomeric tracts in trb1 lines by approximately 10–20% (Figure4c). The graph represents evaluation in the three biological replicates. Observations in earlier generations of trb1 lines (Figure S6) show mild but progressive shortening that continues through the generations. Despite clear and reproducible telomere shortening in trb1, no significant morphological differences were observed in rosette diameter, leaf number, flowering and seed set when analysing soil-grown wild-type and trb1−/−plants.

TRB proteins interact with telomerase in planta

Our previous finding that TRB1 protein interacts with POT1b and evidence presented here showing that TRB1 co-localizes with telomeric repeats and is involved in regulation of telomere maintenance suggest its possible association with telomerase (Kuchar and Fajkus, 2004; Schrumpfova et al., 2008). We therefore tested the possibility of direct interaction between TRB1 and TERT, as well as the influence of TRB1 on telomerase activity in vitro.

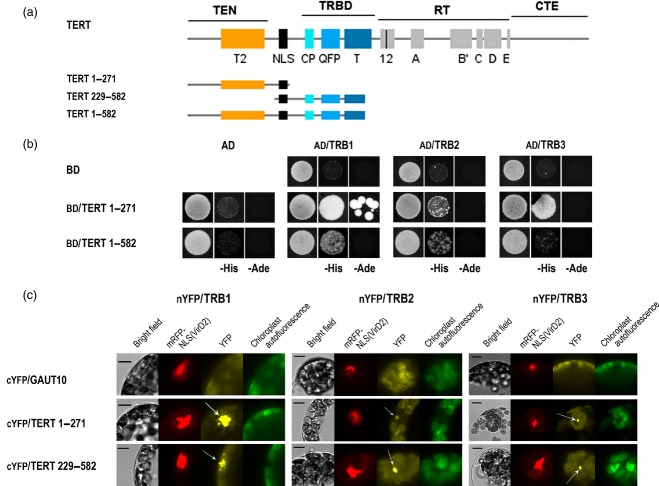

As TERT is a high-molecular-weight protein (approximately 130 kDa), we used TERT fragments containing N–terminal domains associated with distinct telomeric functions (Sykorova and Fajkus, 2009) to detect a possible direct interaction between TERT and TRB proteins (Figure5a). We tested their ability to interact using a GAL4 based yeast two-hybrid system, in which interactions take place inside the nucleus. As shown in Figure5(b), strong interaction between TRB1 and the TERT 1-271 fragment was observed on histidine-deficient plates. This interaction was confirmed under stringent adenine selection. Clear interactions between TRB3 and TERT 1-271 and a weak interaction between TRB2 and TERT 1-271 were also observed under histidine selection. Further testing TRB1 and TRB2 with a longer fragment of TERT (amino acids 1-582) confirmed these interactions.

Figure 5.

TRB proteins interact with plant telomerase (TERT).(a) Schematic depiction of the catalytic subunit of telomerase (TERT) showing evolutionarily conserved motifs. N-terminal fragments containing the telomerase-specific motifs TEN (telomerase essential N–terminal domain) and TRBD (N–terminal RNA-binding domain) were used in protein–protein interaction analysis (amino acid numbering is shown).(b) Yeast two-hybrid system was used to assess interaction of TRB proteins with N–terminal TERT fragments. Two sets of plasmids carrying the indicated segments of TERT fused to either the GAL4 DNA-binding domain (BD) or the GAL4 activation domain (AD) were constructed and introduced into yeast strain PJ69–4a carrying reporter genes His3 and Ade2. Although weak interactions often fail to rescue growth under stringent adenine selection, plausible TRB–TERT interactions were observed on histidine-deficient plates. Co-transformation with an empty vector (AD/BD/vector) served as a negative control.(c) Bimolecular fluorescence complementation confirmed the interaction of TRB proteins with TERT fragments. Arabidopsis leaf protoplasts were co-transfected with 10 μg each of plasmids encoding nEYFP-tagged TRB clones, cEYFP-tagged TERT fragments or Gaut10 (as negative control) and mRFP-VirD2NLS (to label cell nuclei and to determine transfection efficiency). The cells were imaged by epifluorescence microscopy after overnight incubation. Clear nuclear interactions of TRB proteins with TERT fragments are observed on the protoplast images: YFP fluorescence (yellow), mRFP fluorescence (red), chloroplast autofluorescence (green pseudocolor); chloroplast autofluorescence is also visible in the YFP channel (indicated by arrows). Scale bars = 7 μm.

To test whether the interactions observed in a yeast-two hybrid system are reproducible in the plant cell, we used a bimolecular fluorescence complementation assay (BiFC). Arabidopsis protoplasts were transfected with plasmids encoding nYFP-tagged TRB constructs and cYFP-tagged TERT fragments, and a clear intra-nuclear interaction was observed (Figure5c and Figure S7). The TERT fragments used in BiFC (TERT 1-271 and TERT 229-582) overlap with the fragments tested in the yeast two-hybrid system.

The interaction was further verified by co-immunoprecipitation experiments in which proteins were expressed in rabbit reticulocyte lysate from the same vectors used in yeast two-hybrid system. As shown in Figure S8, clear interactions between TRB1 and all three TERT fragments (1-271, 229-582 and 1-582) were observed. Obvious interactions were also detected between TRB3 and TERT 1-271 or TERT 229-582, but only weak interactions were observed between TRB2 and TERT fragments. The generally weaker interactions of TRB2 or TRB3 proteins with TERT fragments in comparison to the corresponding interactions of TRB1 were due to lower expression of TRB2 and TRB3 proteins in rabbit reticulocyte lysate.

To determine whether interaction between TRB proteins and TERT directly influences telomerase activity, we used a telomere repeat amplification protocol (TRAP). In extracts from trb1−/− plants, no changes in telomerase activity or processivity were observed. Correspondingly, no variations in telomerase activity were detected in transformed plants (TRB1pro:TRB1-GFP) expressing higher levels of protein (Figure S9). This observation is in agreement with our previous experiments in which Escherichia coli-expressed and purified TRB2 and TRB3 proteins were added to the TRAP assay (Schrumpfova et al., 2004).

Discussion

The composition of plant shelterin-like complex has long remained elusive due to the high number of candidate proteins with apparently redundant functions (Peska et al., 2011). These obstacles and lack of convincing evidence raised doubts over the existence of such a complex, and its functions have been mostly attributed to the previously described CST complex, which is conserved throughout eukaryotes (Nelson and Shippen, 2012b). However, absence of evidence is not evidence of absence. Our present data suggest the existence of a telomere protein complex that includes plant-specific Smh proteins (termed TRB proteins in Arabidopsis). These proteins interact directly with the catalytic subunit of telomerase: TRB1 protein co-localizes with telomeres, specifically binds telomeric DNA in vitro and in vivo, and TRB1 loss results in telomere shortening. Moreover, TRB proteins also interact with POT1b, a POT1-like orthologue in A. thaliana (Kuchar and Fajkus, 2004; Schrumpfova et al., 2008).

In previous studies, we considered in detail the localization of TRB1 protein, showing that, similar to TRB2 and TRB3, this is a nuclear factor with markedly increased nucleolar labelling and speckles present in the nucleus, especially in Arabidopsis cell cultures transiently transformed with GFP–TRB1 (Dvorackova et al., 2010). We have previously speculated on the telomeric association of GFP–TRB1 speckles, but the low expression of GFP–TRB1 in stably transformed Arabidopsis plants/cultures and the short size of Arabidopsis telomeres impeded its direct demonstration (Dvorackova et al., 2010). In this study, we used a plant system with longer telomeres and sufficient expression of TRB1–GFP protein, and clearly showed that TRB1 co-localizes with telomeres in plant leaves. Close linkage between TRB1 protein and the telomere was further supported by the finding that plant telomeric sequence may be isolated directly from plant seedlings together with TRB1–GFP using the anti-GFP immunoprecipitation system. Specific anti-TRB1 antibodies were also developed and successfully used for detection of TRB1 alone or all TRB proteins in the whole-protein extract by Western blot or ELISA procedures. Using these antibodies, clear nuclear and nucleolar localization of TRB1 protein was demonstrated. Although TRB1 protein need not associate exclusively with telomeres in vivo, the preferential association of TRB1 with the telomeric tracts as described here is in agreement with previous observations using independent approaches (Mozgova et al., 2008; Hofr et al., 2009; Dvorackova et al., 2010). The obvious association of TRB1 with the nucleolus, which contains sub-telomeric clusters of rDNA, may be due to the fact that nucleoli associate with telomeres and telomerase at the cellular level: telomerase assembly occurs in nucleoli in a number of model organisms including plants (Lo et al., 2006; Brown and Shaw, 2008; Kannan et al., 2008), and nucleolus-associated telomere clustering and pairing precede meiotic chromosome synapsis in Arabidopsis thaliana (Armstrong et al., 2001).

The key finding of this work is that TRB proteins interact with the N–terminal part of TERT. This part contains the telomerase-specific motifs TEN (telomerase essential N–terminal domain) and TRBD (N–terminal RNA-binding domain). The most conserved motif, the T–motif, with a high-affinity binding site for the TER subunit, is included in the TRBD domain (Lai et al., 2001). Several distinct functions have been proposed for the TEN domain: e.g. as an anchor during template translocation (Lue, 2005; Wyatt et al., 2007; Sealey et al., 2010), involvement in positioning the 3′ end of a telomeric DNA primer in the active site during nucleotide addition (Jurczyluk et al., 2011), putative mitochondrial localization (Santos et al., 2004), and, last but not least, involvement in protein–protein interactions (Sealey et al., 2011). Hence, the positioning of the region involved in interaction between TERT and TRB proteins in the N–terminal part of telomerase is not surprising. Identification of TRB proteins as the interaction partner of TERT is also supported by the observation that TRB1 protein is present in a group of proteins that were co-purified with the N–terminal part of TERT using tandem affinity purification (P.P.S., J.M., L.D., E.S and J.F., unpublished results).

The observation of TRB/telomerase interaction, together with the previously detected interaction between TRB and POT1b (Kuchar and Fajkus, 2004; Schrumpfova et al., 2008), suggest that TRB proteins are part of the telomeric interactome of A. thaliana. Interaction of POT1b protein with the TRB1 protein is mediated by the central TRB histone-like domain (Schrumpfova et al., 2008), but it is not yet clear how the interaction between telomerase and TRB is mediated. Determination of whether it occurs through the same histone-like domain or the N–terminal Myb domain or C–terminal coiled-coil domain would help to determine mutual exclusion or co-existence of TERT and POT1b association with TRB proteins.

Importantly, POT1b is also an interaction partner of TER2, an alternative telomerase RNA subunit in Arabidopsis (Cifuentes-Rojas et al., 2011, 2012). Together with TERT, dyskerin and Ku, these components form telomerase ribonucleoprotein complex that may participate in telomerase regulation, the DNA damage response and telomere protection, but do not substantially contribute to telomere maintenance (Cifuentes-Rojas et al., 2011, 2012). Therefore, the observation that TRB1 interacts with TERT but its loss or increased expression does not change telomerase activity is not surprising. More importantly, interaction of TRB1 with TERT, together with its affinity for telomeric DNA, indicates a possible role of TRB1 in telomerase recruitment to telomeres. This also explains the observed absence of any direct effect of TRB1 on telomerase activity in the TRAP assay, as this in vitro assay uses a non-telomeric template oligonucleotide that is not recognized by the Myb-like domain of TRB1 (Mozgova et al., 2008).

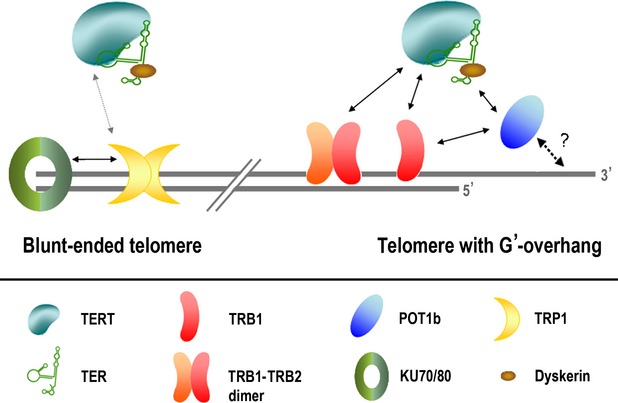

However, POT proteins are not the only putative single-stranded DNA telomere-binding proteins in Arabidopsis, as several other proteins have been identified, e.g. STEP1 (Kwon and Chung, 2004), WHY1 (Yoo et al., 2007a) or CST complex components (Price et al., 2010). Similarly, in addition to the TRB family of proteins, there are also other candidate double-stranded DNA telomere-binding proteins in Arabidopsis, such as TRFL family proteins (Karamysheva et al., 2004). Association of these proteins with telomeres appears not to be mutually exclusive. Presumably, dynamic changes in the composition of telomeric nucleoprotein complexes may reflect the different functional states of telomeres. Two types of plant chromosome ends have been proposed: those with G–overhangs and blunt-ended ones that are recognized by the KU70/80 dimer (Riha et al., 2000; Gallego et al., 2003; Kazda et al., 2012; Nelson and Shippen, 2012a). Thus, the apparently redundant proteins may operate concurrently at telomeres with respect to cell cycle, developmental stage or type of chromosome ends. For example, localization of TRB1 is quite consistent but highly dynamic during interphase; moreover, the level of nuclear-associated TRB1 diminishes during mitotic entry, and it progressively re-associates with chromatin during anaphase/telophase (Dvorackova et al., 2010). Interestingly, our BiFC assay also showed interaction of N–terminal fragments of TERT with TRP1, a member of the TRFL I family (Figure S10) (Hwang et al., 2001; Karamysheva et al., 2004). Importantly, TRP1 also interacts with KU70 (Kuchar and Fajkus, 2004), which is presumably involved in protection of blunt chromosome ends and may also therefore be an integral part of the plant telomere protection complex (Figure6).

Figure 6.

Schematic diagram of observed protein–protein interactions at telomeric ends.Half the telomeric ends in A. thaliana are blunt-ended (Riha et al., 2000; Kazda et al., 2012). Here we show a simplified chart of interactions associated with telomeres. Solid arrows indicate protein–protein interactions that were verified in this study or in previous studies (Kuchar and Fajkus, 2004; Kannan et al., 2008; Schrumpfova et al., 2008; Cifuentes-Rojas et al., 2012; Kazda et al., 2012) using at least two independent approaches (i.e. BiFC, pull-down or yeast-two hybrid assay). The grey arrow indicates a TERT–TRP1 interaction observed only by BiFC. The dashed black arrow shows a presumed interaction between POT1b and telomere single-stranded DNA that has not yet been directly demonstrated. The interaction between POT1b and telomerase is specific for the TER2 isoform of TER, while the other interactions with the telomerase complex are dependent on the catalytic TERT subunit. The diagram suggests the existence of distinct telomerase recruitment pathways for blunt-ended telomeres and telomeres with a G–overhang.

Although it is tempting to draw possible analogies between mammalian shelterin components and the TRB and POT1b proteins involved in a similar plant complex, an alternative interpretation of the function of TRB is possible when considering our data in connection with a recent description of mammalian HOT1 protein (Kappei et al., 2013). This protein shows strikingly similar interactions and functions: it specifically binds double-stranded telomeric DNA repeats, localizes to a subset of telomeres (presumably those that are being elongated), and associates with active telomerase. Thus, HOT1 contributes to the association of telomerase with telomeres and to telomere length maintenance (Kappei et al., 2013). Our findings suggest that TRB proteins may perform similar functions in plant telomeres, i.e. as direct telomere-binding proteins that act as positive regulators of telomere length.

Experimental procedures

Primers

The sequences of all primers and probes used in this study are provided in Table S2.

Plant material and construct generation

The 35Spro:GFP-TRB1 plants and construct have been described previously (Dvorackova et al., 2010). The TRBpro:TRB1-GFP construct was prepared as follows: genomic DNA from A. thaliana Col–0 was isolated using a DNeasy plant mini kit (Qiagen, http://www.qiagen.com/), and used as a template for PCR to amplify the TRB1 genomic sequence including the 5′ UTR. The 3′ UTR was amplified from BAC clone FJ10.16 (Arabidopsis Information Resource, http://www.arabidopsis.org/). We used 0.25 units of Hot Start Phusion polymerase (Finnzymes, http://www.thermoscientificbio.com/finnzymes/) with 0.2 mm dNTPs, 1× HF reaction buffer (Phusion Hot Start II high fidelity DNA polymerase; http://www.thermoscientificbio.com/), 3% dimethylsulfoxide and 0.5 μm of each primer (5′ UTRFw + TRB1 Rev or 3′ UTR Fw + 3′ UTR Rev). The conditions used were in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions (Finnzymes). PCR products were precipitated using poly(ethylene glycol), and cloned into a Gateway multi-site system (Invitrogen, http://www.lifetechnologies.com), together with the GFP tag (GFP in pDONR221, provided by Keke Yi, College of life Sciences, Zhejiang University, China). pKm43GW (Karimi et al., 2005) was used as the destination vector. A. thaliana Col–0 was subsequently transformed by floral dipping (Clough and Bent, 1998), and transformants selected on MS medium containing 30 μg/ml kanamycin were scored for GFP expression.

PCR-based genotyping of plant lines

T–DNA insertion mutant plants of trb1 (SALK_025147) in the Col–0 background were used. To distinguish between wild-type plants and those that were heterozygous or homozygous for the T–DNA insertion in the trb1 gene, we isolated genomic DNA from leaves using NucleoSpin Plant II (Machery Nagel, http://www.mn-net.com/). The genomic DNA was used for PCR analysis with MyTaq DNA polymerase (Bioline, http://www.bioline.com). The conditions used were in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. The primers used were specific for T–DNA (P3 + P2 primers) or the TRB1 gene (P1 + P2 primers). Cycling conditions were 98°C for 1 min (initial denaturation), followed by 30 cycles of 94°C for 30 sec, 58°C for 45 sec and 72°C for 2 min, with a final extension at 72°C for 10 min.

Rt–pcr

Total RNA was extracted from approximately 50 mg of frozen plant tissue using an RNeasy plant mini kit (Qiagen), and RNA samples were treated with TURBO DNA-free (Applied Biosystems/Ambion, http://www.lifetechnologies.com TURBO DNA-free). The quality and quantity of RNA were determined by electrophoresis on 1% w/v agarose gels and by measurement of absorbance using an Implen nanophotometer (http://www.implen.de/). Reverse transcription was performed using random hexamers (Sigma-Aldrich, http://www.sigmaaldrich.com) with 1 μg RNA and Mu-MLV reverse transcriptase (New England Biolabs, https://www.neb.com/). The cDNA obtained was screened by PCR analysis for the presence of trb1 transcripts using MyTaq DNA polymerase (Bioline) with primers P4 and P5. Thermal conditions were 95°C for 1 min (initial denaturation), followed by 30 cycles of 94°C for 45 sec, 55°C for 45 sec and 72°C for 2 min, with a final extension at 72°C for 10 min.

Nicotiana benthamiana transformation, nuclei isolation and FISH

Leaves of 5-week-old N. benthamiana plants were infiltrated with Agrobacterium tumefaciens containing 35Spro:GFP-TRB1 (vector pGWB6, strain LBA4404) (Dvorackova et al., 2010), and 35Spro:p19 (Silhavy et al., 2002) as described by Voinnet et al. (2003). The infiltration medium contained 10 mm MES (pH approximately 5.7) and 10 mm MgCl2. After 3–4 days, leaf discs were checked under a fluorescence microscope, and protoplasts were prepared as described by Yoo et al. (2007b); the digestion medium contained also 0.25% Pectolyase Y23 (Duchefa, http://www.duchefa-biochemie.nl/) in addition to celullase and macerozyme and a 119 μm filter was used for filtration. Protoplasts in W5 buffer were collected by centrifugation at 50 g, and resuspended in NIB (Nuclei Isolation Buffer; 10 mm MES, 0.2M Sucrose, 2.5 mm EDTA,10 mm NaCl, 10 mm KCl 2.5 mm DTT, 0.1 mm Spermine, 0.5 mm Spermidine) to extract nuclei as described by McKeown et al. (2008). Isolated nuclei were then fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min, resuspended in wash buffer (50 mm Tris/Cl, pH 8.5, 5 mm MgCl2, 20% glycerol), 4°C, spun down at 300g and stored in storage buffer (50 mm Tris/Cl, pH 8.5, 5 mm MgCl2, 50% glycerol) at -20°C until use.

Then 20 μl of nuclei were spun on the Superfrost plus microscopic slide (http://www.menzel.de/) at 56 g, and re-fixed in 4% p-formaldehyde in 1× PBS/0.05% Triton X-100 for 15 min. Slides were then treated with RNase (100 μg/ml) for 1 h at 37°C, and hybridized with telomeric Cy3-labelled peptide nucleic acid probe in 65% formamide/20% dextran sulfate/2× SSC at 37°C overnight. Post-hybridization washes were performed at 37°C using 2× SSC. Slides were counter-stained using 4,6–diamidino-2–phenylindole (1 μg/ml), and observed on a Zeiss (http://www.zeiss.cz/) Axioimager Z1 using an AHF filter set.

Immunolocalization

Arabidopsis seeds expressing TRB1pro:TRB1-GFP under the control of the native promoter and trb1 seeds were bleach-sterilized for 10 min, washed in water and sown onto half-strength MS medium/1% agar plates. Seedlings grown under the constant light, at 22°C for 2 weeks, then chopped into small pieces. Protoplasts were prepared as described by Yoo et al. (2007b), and the nuclei and immunolocalization protocols were adapted from those described by McKeown et al. (2008). Slides were first blocked in a mixture of 2× block solution (Roche, http://www.roche.cz)/1× PBS/5% goat serum at room temperature for 30 min, then incubated with primary antibodies [mouse anti-TRB 1.2 or 5.2 or, anti-GFP (Abcam ab290, http://www.abcam.com/), all diluted 1:300] for 2 h at 37°C, and visualized using secondary antibodies A11001 and A21207 (Invitrogen) at 1:500 dilution.

Immunblot analysis

To determine the level of TRB1 protein in plants, we isolated nuclei as described by Bowler et al. (2004). The nuclei were lysed using SDS loading buffer (250 mm Tris/Cl, pH 6.8, 4% w/v SDS, 0.2% w/v bromophenol blue, 20% v/v glycerol, 200 mm β–mercaptoethanol), heated at 80°C for 10 min, and protein extracts were analysed by SDS–PAGE. Proteins were electrophoretically transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane at 360 mA for 1 hour in 192 mm glycine, 25 mm Tris, 0.5% SDS and 10% (v/v) methanol in a Bio-Rad Mini Trans-Blot cell. Ponceau S staining was performed to check the quality of the extracts and to ensure equal gel loading for immunodetection. Membranes were blocked with 5% non-fat dry milk in Tris-buffered saline/Tween, and probed using the monoclonal anti-TRB1 1.2 antibody and the secondary polyclonal horseradish peroxidase-conjugated rabbit anti-mouse immunoglobulins (DAKO, http://www.dako.com), both diluted 1:5000. Immunoreactive bands were visualized using LumiGLO reagent and peroxide (Cell Signaling Technology, http://www.cellsignal.com) on a Fujifilm LAS-3000 CCD system (http://www.fujifilm.com/).

Chromatin immunoprecipitation assay

The ChIP assay was performed as described by Bowler et al. (2004) with modifications. Chromatin extracts were prepared from seedlings treated with 1% formaldehyde. The chromatin from isolated nuclei was sheared to a mean length of 250–500 bp by sonication using a Bioruptor (Diagenode, http://www.diagenode.com) and centrifuged (16 000 g/5 min/4°C). The matrix GFP-Trap A (Chromtec, http://www.chromotek.com) was blocked against non-specific interaction using 200 mm ethanolamine, 1% BSA and the DNA sequences TR10–24–G and TR10–24–C (Table S2), which are not recognized by TRB proteins (Schrumpfova et al., 2004). The pre-treated matrix was incubated with chromatin diluted with ChIP dilution buffer (16.7 mm Tris/Cl, pH 8,0, 1.2 mm EDTA, 167 mm NaCl, 0.1% Triton X–100, phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride and protease inhibitors) at 4°C for 4 h, and subsequently washed with low-salt, high-salt, LiCl and 10 mm Tris (pH = 8,0), 1 mm EDTA (TE) buffers. In contrast to Bowler et al. (2004), the levels of detergents (Triton X–100, Nonidet P-40 and sodium deoxycholate) were reduced to 0.1%. The cross-linking was reversed using 0.2 m NaCl overnight, and was followed by treatment with proteinase K (Serva, http://www.serva.de) treatment, phenol/chlorophorm extraction and treatment with RNase A (Serva) as described by Bowler et al. (2004). ChIP assays were repeated using three biological replicates (plants grown at different times).

Dot-blot assay

DNA isolated using ChIP was diluted into 200 μl of 400 mm NaOH and 10 mm EDTA, and samples were denatured at 95°C for 10 min and cooled on ice. They were then spotted onto Hybond XL membrane (GE Healthcare, http://www3.gehealthcare.com) and subjected to hybridization with sequence-specific probe TR–4C (Table S2). The probe was hybridized in 250 m sodium phosphate, pH 7.5, 7% SDS and 16 mm EDTA overnight at 55°C, and washed with 0.2× SSC + 0.1% SDS. The signal was evaluated using MultiGauge software (Fujifilm). All experiments were performed using three independent biological replicates. Re-hybridization with centromeric and 18S rDNA probes was performed as described previously (Mozgova et al., 2010).

TRAP assay

Protein extracts from 2-week-old seedlings were prepared as described by Fitzgerald et al. (1996). These extracts were subjected to the TRAP assay as described by Fajkus et al. (1998). TS21 was used as the substrate primer for extension by telomerase, and TEL-PR was used as the reverse primer in the subsequent PCR.

TRF analysis

TRF analysis was performed as described previously (Ruckova et al., 2008) using 500 ng genomic DNA isolated from 5–7-week-old rosette leaves using NucleoSpin Plant II (Machery Nagel). Southern hybridization was performed using the end-labelled telomere-specific probe TR–4C (Table S2). Telomeric signals were visualized using an FLA7000 imager (Fujifilm), and a grey-scale intensity profile was generated using MultiGauge software (Fujifilm). Evaluation of fragment lengths was performed using a Gene Ruler 1 kb DNA ladder (Fermentas, http://www.thermoscientificbio.com/fermentas/) as the standard. Mean telomere lengths were calculated as described by Grant et al. (2001).

Yeast two-hybrid analysis

Yeast two-hybrid experiments were performed using the Matchmaker™ GAL4-based two-hybrid system (Clontech, http://www.clontech.com/). cDNA sequences encoding TERT N - terminal fragments comprising amino acids 1-271 and 1-582 were sub-cloned from pDONR/Zeo entry clones (Zachova et al., 2013) into the Gateway-compatible destination vector pGBKT7-DEST (bait vector). The pGBKT7-DEST destination vector that was used in this study was created by Horak et al. (2008) who introduced the Gateway conversion cassette into the original Matchmaker system vector pGBKT7 (Clontech). The pGADT7 prey vectors (Clontech) carrying TRB1, TRB2 and TRB3 have been described previously (Schrumpfova et al., 2008). Each bait/prey combination was co-transformed into Saccharomyces cerevisiae PJ69–4a, and colonies were inoculated into YPD medium and cultivated overnight. Successful co-transformation was confirmed on SD medium lacking Leu and Trp, and positive interactions were selected on SD medium lacking Leu, Trp and His or SD medium lacking Leu, Trp and Ade. Co-transformation with an empty vector served as a negative control for auto-activation. Each test was performed three times using two replicates at a time. In addition, the protein expression levels were verified by immunoblotting.

Bimolecular fluorescence complementation

For PCR amplification of sequences encoding the tested proteins, and to generate restriction site overhangs, Phusion HF DNA polymerase (Finnzymes) was used. The conditions used were in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions. The primers used were F–TRB1/2/3_BstBI, R–TRB1/2/3_SmaI, F–TERT_KpnI, R–RID1+BamHI, F–F2N_KpnI and R–F2N+BamHI, and plasmids encoding the tested proteins were used as templates. The amplified DNA fragments were gel-purified, digested with BstBI/SmaI or KpnI/BamHI (New England Biolabs), and ligated into vectors pSAT1-nEYFP and pSAT1-cEYFP. As a negative control, we used an AtGaut10-cEYFP construct. To quantify transformation efficiency and to label cell nuclei, we co-transfected a plasmid expressing mRFP fused to the nuclear localization signal of the VirD2 protein of A. tumefaciens (mRFP-VirD2NLS; Citovsky et al., 2006). The vectors and the mRFP-VirD2NLS and AtGaut10-cEYFP constructs were kindly provided by Stanton Gelvin (Department of Biological Sciences, Purdue University, IN, USA). Arabidopsis thaliana leaf protoplasts were prepared and transfected as described by Wu et al. (2009). DNA (10 μg of each construct) was introduced into 1 × 105 protoplasts. Transfected protoplasts were incubated in the light at room temperature overnight, and then observed for fluorescence using a Zeiss AxioImager Z1 epifluorescence microscope equipped with filters for YFP (Alexa Fluor 488), RFP (Texas Red) and CY5 (chloroplast autofluorescence).

In vitro translation and co-immunoprecipitation

Proteins were expressed from the same constructs as used in the yeast two-hybrid system with a haemagglutinin tag (pGADT7; TRB1, 2 and 3 proteins) or a Myc tag (pGBKT7; TERT fragments) using a TNT quick coupled transcription/translation system (Promega, https://www.promega.com) in 50 μl reaction volumes according to the manufacturer's instructions. The TRB proteins were radioactively labelled using 35S-Met. The co-immunoprecipitation procedure was performed as described by Schrumpfova et al. (2011). Input, unbound and bound fractions were separated by 12% SDS–PAGE, and analysed using an FLA7000 imager (Fujifilm).

Accession numbers

Sequence data have been deposited in the Arabidopsis Genome Initiative or GenBank/EMBL databases under the following accession numbers: At1g49950 (TRB1), At5g67580 (TRB2, formerly TBP3), At3g49850 (TRB3, formerly TBP2,), At5g16850.1 (TERT), At2g20810 (Gaut10) and At5g59430 (TRP1).

Acknowledgments

We would thank to Dorothy E. Shippen (Department of Biochemistry,Texas A&M University,TX, USA) for donation of TRFL contructs, Stanton B. Gelvin (Department of Biological Sciences, purdue University, IN, USA) for donation of mRFP-VirD2NLS and AtGaut10-cEYFP constructs and his help with initial analysis of BiFC experiments, and Iva Mozgova (Department of Plant Biology and Forest Genetics, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, SW) for discussion and support. The research was supported by the Czech Science Foundation (13-06943S), by project CEITEC (CZ.1.05/1.1.00/02.0068) of the European Regional Development Fund, and project CZ1.07/2.3.00/30.0009 co-financed from European Social Fund and the state budget of the Czech Republic.

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article.

Detection of TRB1–GFP protein by specific anti-TRB1 1.2 antibody in ChIP fractions.

Figure S2. Telomeric sequence is highly enriched compared to centromeric DNA or 18S rDNA.

Figure S3. Location of antibody recognition sites within the structure of TRB1 protein.

Figure S4. Anti-TRB 1.2 and 5.2 antibodies were unable to detect proteins from TRFL family.

Figure S5. Anti-TRB1 1.2 does not detect any signal on trb1−/− plants, but 5.2 recognizes some epitopes in trb1−/−mutant plant lines.

Figure S6. Telomere shortening in trb1−/−plants is progressive.

Figure S7. Whole images of protoplasts (whose segments are shown in Figure 5C) obtained by bimolecular fluorescence complementation.

Figure S8. TRB1, 2 and 3 proteins are able to pull-down TERT fragments.

Figure S9. Telomerase activity or processivity in vitro is not changed in response to TRB1 status.

Figure S10. TRP1 protein interacts with plant telomerase (TERT).

Quantification of TRB1 foci co-localized/associated with telomeric foci.

Table S2. Sequences of all primers and probes used in this study.

References

- Armstrong SJ, Franklin FC, Jones GH. Nucleolus-associated telomere clustering and pairing precede meiotic chromosome synapsis in Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Cell Sci. 2001;114:4207–4217. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.23.4207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann P, Podell E, Cech TR. Human Pot1 (Protection of telomeres) protein: cytolocalization, gene structure, and alternative splicing. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2002;22:8079–8087. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.22.8079-8087.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilaud T, Koering CE, Binet-Brasselet E, Ancelin K, Pollice A, Gasser SM, Gilson E. The telobox, a Myb-related telomeric DNA binding motif found in proteins from yeast, plants and human. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:1294–1303. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.7.1294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackburn EH, Gall JG. Tandemly repeated sequence at termini of extrachromosomal ribosomal RNA genes in Tetrahymena. J. Mol. Biol. 1978;120:33–53. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(78)90294-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowler C, Benvenuto G, Laflamme P, Molino D, Probst AV, Tariq M, Paszkowski J. Chromatin techniques for plant cells. Plant J. 2004;39:776–789. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2004.02169.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown JW, Shaw PJ. The role of the plant nucleolus in pre-mRNA processing. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 2008;326:291–311. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-76776-3_16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen LY, Redon S, Lingner J. The human CST complex is a terminator of telomerase activity. Nature. 2012;488:540–544. doi: 10.1038/nature11269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cifuentes-Rojas C, Kannan K, Tseng L, Shippen DE. Two RNA subunits and POT1a are components of Arabidopsis telomerase. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:73–78. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1013021107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Cifuentes-Rojas C, Nelson ADL, Boltz KA, Kannan K, She XT, Shippen DE. An alternative telomerase RNA in Arabidopsis modulates enzyme activity in response to DNA damage. Genes Dev. 2012;26:2512–2523. doi: 10.1101/gad.202960.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Citovsky V, Lee LY, Vyas S, Glick E, Chen MH, Vainstein A, Gafni Y, Gelvin SB, Tzfira T. Subcellular localization of interacting proteins by bimolecular fluorescence complementation in planta. J. Mol. Biol. 2006;362:1120–1131. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clough SJ, Bent AF. Floral dip: a simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 1998;16:735–743. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1998.00343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dvorackova M, Rossignol P, Shaw PJ, Koroleva OA, Doonan JH, Fajkus J. AtTRB1, a telomeric DNA-binding protein from Arabidopsis, is concentrated in the nucleolus and shows highly dynamic association with chromatin. Plant J. 2010;61:637–649. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2009.04094.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fajkus J, Fulneckova J, Hulanova M, Berkova K, Riha K, Matyasek R. Plant cells express telomerase activity upon transfer to callus culture, without extensively changing telomere lengths. Mol. Gen. Genet. 1998;260:470–474. doi: 10.1007/s004380050918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgerald MS, McKnight TD, Shippen DE. Characterization and developmental patterns of telomerase expression in plants. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:14422–14427. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.25.14422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallego ME, Bleuyard JY, Daoudal-Cotterell S, Jallut N, White CI. Ku80 plays a role in non-homologous recombination but is not required for T-DNA integration in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2003;35:557–565. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2003.01827.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao H, Cervantes RB, Mandell EK, Otero JH, Lundblad V. RPA-like proteins mediate yeast telomere function. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2007;14:208–214. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giraud-Panis MJ, Teixeira MT, Geli V, Gilson E. CST meets shelterin to keep telomeres in check. Mol. Cell. 2010;39:665–676. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant JD, Broccoli D, Muquit M, Manion FJ, Tisdall J, Ochs MF. Telometric: a tool providing simplified, reproducible measurements of telomeric DNA from constant field agarose gels. Biotechniques. 2001;31(1314–1316):1318. doi: 10.2144/01316bc02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greider CW, Blackburn EH. Identification of a specific telomere terminal transferase activity in Tetrahymena extracts. Cell. 1985;43:405–413. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90170-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greider CW, Blackburn EH. A telomeric sequence in the RNA of Tetrahymena telomerase required for telomere repeat synthesis. Nature. 1989;337:331–337. doi: 10.1038/337331a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofr C, Sultesova P, Zimmermann M, Mozgova I, Schrumpfova PP, Wimmerova M, Fajkus J. Single-Myb-histone proteins from Arabidopsis thaliana: a quantitative study of telomere-binding specificity and kinetics. Biochem. J. 2009;419:221–228. doi: 10.1042/BJ20082195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horak J, Grefen C, Berendzen KW, Hahn A, Stierhof YD, Stadelhofer B, Stahl M, Koncz C, Harter K. The Arabidopsis thaliana response regulator ARR22 is a putative AHP phospho-histidine phosphatase expressed in the chalaza of developing seeds. BMC Plant Biol. 2008;8:77. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-8-77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang MG, Chung IK, Kang BG, Cho MH. Sequence-specific binding property of Arabidopsis thaliana telomeric DNA binding protein 1 (AtTBP1) FEBS Lett. 2001;503:35–40. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02685-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang MG, Kim K, Lee WK, Cho MH. AtTBP2 and AtTRP2 in Arabidopsis encode proteins that bind plant telomeric DNA and induce DNA bending in vitro. Mol. Genet. Genomics. 2005;273:66–75. doi: 10.1007/s00438-004-1096-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurczyluk J, Nouwens AS, Holien JK, Adams TE, Lovrecz GO, Parker MW, Cohen SB, Bryan TM. Direct involvement of the TEN domain at the active site of human telomerase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011;39:1774–1788. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq1083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kannan K, Nelson AD, Shippen DE. Dyskerin is a component of the Arabidopsis telomerase RNP required for telomere maintenance. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2008;28:2332–2341. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01490-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kappei D, Butter F, Benda C, et al. HOT1 is a mammalian direct telomere repeat-binding protein contributing to telomerase recruitment. EMBO J. 2013;32:1681–1701. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2013.105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karamysheva ZN, Surovtseva YV, Vespa L, Shakirov EV, Shippen DE. A C–terminal Myb extension domain defines a novel family of double-strand telomeric DNA-binding proteins in Arabidopsis. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:47799–47807. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407938200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karimi M, De Meyer B, Hilson P. Modular cloning in plant cells. Trends Plant Sci. 2005;10:103–105. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2005.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazda A, Zellinger B, Rossler M, Derboven E, Kusenda B, Riha K. Chromosome end protection by blunt-ended telomeres. Genes Dev. 2012;26:1703–1713. doi: 10.1101/gad.194944.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuchar M, Fajkus J. Interactions of putative telomere-binding proteins in Arabidopsis thaliana: identification of functional TRF2 homolog in plants. FEBS Lett. 2004;578:311–315. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon C, Chung IK. Interaction of an Arabidopsis RNA-binding protein with plant single-stranded telomeric DNA modulates telomerase activity. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:12812–12818. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312011200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai CK, Mitchell JR, Collins K. RNA binding domain of telomerase reverse transcriptase. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2001;21:990–1000. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.4.990-1000.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Lange T. Shelterin: the protein complex that shapes and safeguards human telomeres. Genes Dev. 2005;19:2100–2110. doi: 10.1101/gad.1346005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Lange T. How telomeres solve the end-protection problem. Science. 2009;326:948–952. doi: 10.1126/science.1170633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo SJ, Lee CC, Lai HJ. The nucleolus: reviewing oldies to have new understandings. Cell Res. 2006;16:530–538. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7310070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lue NF. A physical and functional constituent of telomerase anchor site. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:26586–26591. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M503028200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marian CO, Bordoli SJ, Goltz M, Santarella RA, Jackson LP, Danilevskaya O, Beckstette M, Meeley R, Bass HW. The maize Single myb histone 1 gene, Smh1, belongs to a novel gene family and encodes a protein that binds telomere DNA repeats in vitro. Plant Physiol. 2003;133:1336–1350. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.026856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKeown P, Pendle AF, Shaw PJ. Preparation of Arabidopsis nuclei and nucleoli. Methods Mol. Biol. 2008;463:67–75. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-406-3_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mozgova I, Schrumpfova PP, Hofr C, Fajkus J. Functional characterization of domains in AtTRB1, a putative telomere-binding protein in Arabidopsis thaliana. Phytochemistry. 2008;69:1814–1819. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mozgova I, Mokros P, Fajkus J. Dysfunction of chromatin assembly factor 1 induces shortening of telomeres and loss of 45S rDNA in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell. 2010;22:2768–2780. doi: 10.1105/tpc.110.076182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nandakumar J, Bell CF, Weidenfeld I, Zaug AJ, Leinwand LA, Cech TR. The TEL patch of telomere protein TPP1 mediates telomerase recruitment and processivity. Nature. 2012;492:285–289. doi: 10.1038/nature11648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson AD, Shippen DE. Blunt-ended telomeres: an alternative ending to the replication and end protection stories. Genes Dev. 2012a;26:1648–1652. doi: 10.1101/gad.199059.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson AD, Shippen DE. Surprises from the chromosome front: lessons from Arabidopsis on telomeres and telomerase; Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol; 2012b. pp. 7–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peska V, Sykorova E, Fajkus J. Two faces of Solanaceae telomeres: a comparison between Nicotiana and Cestrum telomeres and telomere-binding proteins. Cytogenet. Genome Res. 2008;122:380–387. doi: 10.1159/000167826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peska V, Schrumpfova PP, Fajkus J. Using the telobox to search for plant telomere binding proteins. Curr. Protein Peptide Sci. 2011;12:75–83. doi: 10.2174/138920311795684968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto AR, Li H, Nicholls C, Liu JP. Telomere protein complexes and interactions with telomerase in telomere maintenance. Front. Biosci. 2011;16:187–207. doi: 10.2741/3683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price CM, Boltz KA, Chaiken MF, Stewart JA, Beilstein MA, Shippen DE. Evolution of CST function in telomere maintenance. Cell Cycle. 2010;9:3157–3165. doi: 10.4161/cc.9.16.12547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riha K, Fajkus J, Siroky J, Vyskot B. Developmental control of telomere lengths and telomerase activity in plants. Plant Cell. 1998;10:1691–1698. doi: 10.1105/tpc.10.10.1691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riha K, McKnight TD, Fajkus J, Vyskot B, Shippen DE. Analysis of the G–overhang structures on plant telomeres: evidence for two distinct telomere architectures. Plant J. 2000;23:633–641. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2000.00831.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotkova G, Sykorova E, Fajkus J. Protect and regulate: recent findings on plant POT1-like proteins. Biol. Plant. 2009;53:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Ruckova E, Friml J, Prochazkova Schrumpfova P, Fajkus J. Role of alternative telomere lengthening unmasked in telomerase knock-out mutant plants. Plant Mol. Biol. 2008;66:637–646. doi: 10.1007/s11103-008-9295-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos JH, Meyer JN, Skorvaga M, Annab LA, Van Houten B. Mitochondrial hTERT exacerbates free-radical-mediated mtDNA damage. Aging Cell. 2004;3:399–411. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9728.2004.00124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrumpfova P, Kuchar M, Mikova G, Skrisovska L, Kubicarova T, Fajkus J. Characterization of two Arabidopsis thaliana Myb-like proteins showing affinity to telomeric DNA sequence. Genome. 2004;47:316–324. doi: 10.1139/g03-136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrumpfova PP, Kuchar M, Palecek J, Fajkus J. Mapping of interaction domains of putative telomere-binding proteins AtTRB1 and AtPOT1b from Arabidopsis thaliana. FEBS Lett. 2008;582:1400–1406. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2008.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrumpfova PP, Fojtova M, Mokros P, Grasser KD, Fajkus J. Role of HMGB proteins in chromatin dynamics and telomere maintenance in Arabidopsis thaliana. Curr. Protein Peptide Sci. 2011;12:105–111. doi: 10.2174/138920311795684922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sealey DC, Zheng L, Taboski MA, Cruickshank J, Ikura M, Harrington LA. The N–terminus of hTERT contains a DNA-binding domain and is required for telomerase activity and cellular immortalization. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:2019–2035. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp1160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sealey DC, Kostic AD, LeBel C, Pryde F, Harrington L. The TPR-containing domain within Est1 homologs exhibits species-specific roles in telomerase interaction and telomere length homeostasis. BMC Mol. Biol. 2011;12:45. doi: 10.1186/1471-2199-12-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sfeir A, Kosiyatrakul ST, Hockemeyer D, MacRae SL, Karlseder J, Schildkraut CL, de Lange T. Mammalian telomeres resemble fragile sites and require TRF1 for efficient replication. Cell. 2009;138:90–103. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.06.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shakirov EV, Surovtseva YV, Osbun N, Shippen DE. The Arabidopsis Pot1 and Pot2 proteins function in telomere length homeostasis and chromosome end protection. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2005;25:7725–7733. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.17.7725-7733.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silhavy D, Molnar A, Lucioli A, Szittya G, Hornyik C, Tavazza M, Burgyan J. A viral protein suppresses RNA silencing and binds silencing-generated, 21- to 25-nucleotide double-stranded RNAs. EMBO J. 2002;21:3070–3080. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surovtseva YV, Churikov D, Boltz KA, Song XY, Lamb JC, Warrington R, Leehy K, Heacock M, Price CM, Shippen DE. Conserved telomere maintenance component 1 interacts with STN1 and maintains chromosome ends in higher eukaryotes. Mol. Cell. 2009;36:207–218. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surovtseva YV, Shakirov EV, Vespa L, Osbun N, Song X, Shippen DE. Arabidopsis POT1 associates with the telomerase RNP and is required for telomere maintenance. EMBO J. 2007;26:3653–3661. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sykorova E, Fajkus J. Structure–function relationships in telomerase genes. Biol. Cell. 2009;101:375–392. doi: 10.1042/BC20080205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tani A, Murata M. Alternative splicing of Pot1 (Protection of telomere)-like genes in Arabidopsis thaliana. Genes Genet. Syst. 2005;80:41–48. doi: 10.1266/ggs.80.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voinnet O, Rivas S, Mestre P, Baulcombe D. An enhanced transient expression system in plants based on suppression of gene silencing by the p19 protein of tomato bushy stunt virus. Plant J. 2003;33:949–956. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2003.01676.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu FH, Shen SC, Lee LY, Lee SH, Chan MT, Lin CS. Tape-Arabidopsis sandwich – a simpler Arabidopsis protoplast isolation method. Plant Methods. 2009;5:16. doi: 10.1186/1746-4811-5-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu P, Takai H, de Lange T. Telomeric 3’ overhangs derive from resection by Exo1 and Apollo and fill-in by POT1b-associated CST. Cell. 2012;150:39–52. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyatt HD, Lobb DA, Beattie TL. Characterization of physical and functional anchor site interactions in human telomerase. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2007;27:3226–3240. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02368-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo HH, Kwon C, Lee MM, Chung IK. Single-stranded DNA binding factor AtWHY1 modulates telomere length homeostasis in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2007a;49:442–451. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2006.02974.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo SD, Cho YH, Sheen J. Arabidopsis mesophyll protoplasts: a versatile cell system for transient gene expression analysis. Nat. Protoc. 2007b;2:1565–1572. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zachova D, Fojtova M, Dvorackova M, Mozgova I, Lermontova I, Peska V, Schubert I, Fajkus J, Sykorova E. Structure–function relationships during transgenic telomerase expression in Arabidopsis. Physiol. Plant. 2013;149:114–126. doi: 10.1111/ppl.12021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Detection of TRB1–GFP protein by specific anti-TRB1 1.2 antibody in ChIP fractions.

Figure S2. Telomeric sequence is highly enriched compared to centromeric DNA or 18S rDNA.

Figure S3. Location of antibody recognition sites within the structure of TRB1 protein.

Figure S4. Anti-TRB 1.2 and 5.2 antibodies were unable to detect proteins from TRFL family.

Figure S5. Anti-TRB1 1.2 does not detect any signal on trb1−/− plants, but 5.2 recognizes some epitopes in trb1−/−mutant plant lines.

Figure S6. Telomere shortening in trb1−/−plants is progressive.

Figure S7. Whole images of protoplasts (whose segments are shown in Figure 5C) obtained by bimolecular fluorescence complementation.

Figure S8. TRB1, 2 and 3 proteins are able to pull-down TERT fragments.

Figure S9. Telomerase activity or processivity in vitro is not changed in response to TRB1 status.

Figure S10. TRP1 protein interacts with plant telomerase (TERT).

Quantification of TRB1 foci co-localized/associated with telomeric foci.

Table S2. Sequences of all primers and probes used in this study.