Introduction

Women with a family history of breast cancer (FH+) have elevated cancer worry [1]. Objective breast cancer risk contributes to reports of cancer worry among FH+ women; however, perceived breast cancer risk, which is often overestimated, is a stronger predictor of breast cancer worry [2]. Lazarus and Folkman's paradigm is a helpful model to understand how individuals appraise their vulnerability to breast cancer (perceived risk) [3]. The original framework focused on three major constructs: cognitive appraisal, coping, and daily stress. Primary cognitive appraisal of experienced and anticipated stressors may result in specific types of coping processes, which in turn may influence emotional reactions to stressors [3]. With regard to breast cancer, overestimated cognitive appraisal or perceived risk of breast cancer may result in specific types of coping that are associated with unnecessarily high levels of cancer worry. To date, no research tested the alternative theoretical mediation framework posed by Lazarus and Folkman in the context of cognitive appraisal of breast cancer risk, coping, and breast cancer worry [3]. The current study addressed this gap and tested the hypothesis that increased perceived breast cancer risk was associated with breast cancer worry due to decreased engaged or increased disengaged coping.

Methods

Procedures

Recruitment

This community-based sample included women with a family history of breast cancer and high levels of psychological distress; further information concerning recruitment is described elsewhere [4]. The data analyzed for the current study focus on responses provided at baseline for all participants involved in a 7-month intervention trial.

Measures

Perceived breast cancer risk

Three items (e.g., “On a scale of 0-100, what do you think your chances of getting breast cancer are?”) were used to measure perceived risk for breast cancer [5]. Response categories included a 5-point Likert and 0-100% options. Items were Z-transformed and averaged. Internal consistency was acceptable (Cronbach's α = 0.72).

Breast cancer worry

Two instruments were administered to assess cancer worry. The Cancer Worry scale (CWS) is a 4-item instrument (e.g., “During the past month, how often have thoughts about your chances of getting ovarian or breast cancer affected your mood?”) [6]. Response ranged from 1 (“rarely or not at all”) to 4 (“a lot”). Cronbach's α was 0.68. The 15-item Impact of Events Scale (IES) was also used [7]. Prior to IES items, participants were thought to indicate how their perceived risk for breast cancer affected them. They were then asked the IES items, including “I have had waves of strong feelings about it.” Response ranged from 0 (“not at all”) to 5 (“often”). Standard protocols were used to calculate total summary scores [6-7]. Cronbach's α was. 90. The CWS and IES were strongly associated with each other (r = 0.57, df = 154, p <.0001). Given this, a composite score of cancer worry was calculated from loadings through a factor analysis.

Coping strategies

Participants completed the 28-item Brief COPE [8], which has fourteen two-item subscales, concerning coping strategies since they learned about their risk for breast cancer. Response options ranged from 1 (“I haven't been doing this at all”) to 4 (“I've been doing this a lot”). We did not include denial coping, given Cronbach's α was lower than 0.60; all other scales had adequate reliability in our sample. We conducted a factor analysis with varimax rotation to identify potential higher-order factors among the remaining scales. Two factors emerged: engaged and disengaged coping. All scales had a factor loading of >0.40, except for substance use and venting; these subscales were not used in subsequent analyses. Engaged coping included the following scales: emotional support, instrumental support, positive reframing, planning, acceptance, religion, and active coping (14 items; α = 0.84). Disengaged coping included behavioral disengagement, humor, self-blame, and self-distraction coping (8 items; α = 0.68).

Analysis plan

We assessed relationships between perceived breast cancer risk, higher order coping strategies, and breast cancer worry. The Preacher & Hayes method [9] was used to test mediation. This bootstrap method is a nonparametric resampling procedure that involves sampling from the data set multiple times (5,000 for this study) and generating a sampling distribution. Unstandardized coefficients were determined by the measurement scales of study variables in the model (ranges in Table 1). For comparison, we report traditional tests for mediation (i.e., Sobel test [9]). Given the cross-sectional nature of the data, we tested coping as a mediator in associations wherein perceived breast cancer risk is the independent variable and breast cancer worry is the outcome as well as in associations wherein breast cancer worry is the independent variable and perceived risk is the outcome.

Table 1.

Socio-demographic characteristics and study variables of interest (n= 156)

| Variable | M (SD) |

|---|---|

| Age | 43.25 (10.45) |

| Years of education | 16.76 (2.60) |

| Income | $51-70,000 ($15,000) |

| Number of years with known FH+ status | 7.71 (2.52) |

| Perceived breast cancer risk1 | 0.03 (0.89) |

| Engaged coping2 | 4.21 (1.27) |

| Disengaged coping2 | 3.30 (1.16) |

| Breast cancer worry3 | 13.81 (13.23) |

|

% (n) |

|

| Race/ethnicity | |

| Non-Hispanic White | 80.2% (118) |

| Other | 19.8% (29) |

| % Married | 45.3% (72) |

| % Employed full-time | 68.6% (110) |

Note.

The range was −2 to 2.

The range was 0-8.

Cancer worry scores were developed from an exploratory factor analysis. The range was −2.33 to 3.72.

Results

Table 1 provides sample characteristics (n = 156). Perceived breast cancer risk was negatively correlated with education (r = -0.16, p = .05) and age (r = -0.25, p = .002). No other significant correlations emerged from socio-demographic characteristics and study variables of interest. Given this, we included age and education in all subsequent analyses. Because there were few missing cases (<5%), we used case deletions to accommodate them.

After adjusting for age and education, perceived breast cancer risk was associated with disengaged coping (r = 0.19, p = .02) and breast cancer worry (r=0.33, p <.0001), but not with engaged coping (r = 0.002, p = 0.98). Disengaged coping strategies was positively correlated with breast cancer worry (r = 0.46, p <.0001), as was engaged coping strategies (r = 0.31, p<.0001).

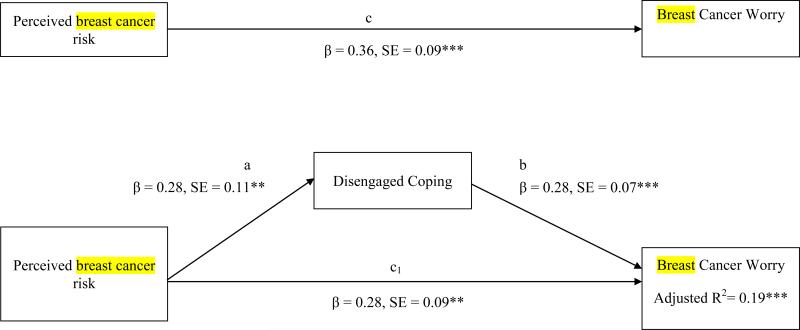

We conducted two separate analyses to assess the mediating role of disengaged coping. Disengaged coping emerged as a significant variable when perceived breast cancer risk was the independent variable and breast cancer worry was the outcome: Mediated Effect = 0.08, 95%CI [.02, .17]. Sobel tests suggested similar findings, Z = 2.04, p = .04, Figure 1. Models wherein breast cancer worry was the independent variable and perceived breast cancer risk was the outcome were not significant: Mediated Effect = .04, 95%CI [-0.02, 0.11]. Findings were similar when Sobel tests were conducted: Z = 0.86, p = .39.

Figure 1.

Mediation model of the relationship of perceived breast cancer risk and breast cancer worry. Age and education are included as covariates. *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

Discussion

The current study is the first to assess coping as a psychological mechanism underlying the relationship between perceived breast cancer risk and breast cancer worry among FH+ women. Our hypotheses were partially supported: perceived breast cancer risk among FH+ women in our sample were partially related to breast cancer worry through coping, and specifically disengaged coping. Nonetheless, coping only partially mediated associations, which coincides with literature concerning the direct effect of appraisal processes (e.g., controllability about personal breast cancer risk) on psychological adaptation [3].

There were several limitations as well as implications for important next steps. Convenience-based recruitment influences the generalizability of these results. Our current study did not collect data concerning variables previously associated with breast cancer worry, such as objective risk [2]. Disengaged coping and a form of engaged coping (e.g., social support) have been shown to moderate associations between objective breast cancer risk (number of family members) and cancer-related distress (e.g., [10]). Given this and our findings, future research should incorporate both objective and perceived breast cancer risk as well as measure overestimation of breast cancer risk. Such work will better elucidate the mediating and moderating effects of coping in response to breast cancer risk. This may be helpful toward future interventions mitigating the effect of overestimated breast cancer risk in terms of elevated breast cancer worry. As a cross-sectional study, we are not able to draw any causal inference and thus are unable to provide a formal test of mediation. It is likely that relationships are complex. For example, relationships may be bidirectional or may be in a direction opposite to the theoretical framework used in this study, although our preliminary findings suggest this is not the case. Longitudinal research is needed to confirm causal relationships suggested by this work. Finally, future research should incorporate early breast cancer detection practices in models to determine the indirect influences of coping on associations between perceived breast cancer risk and breast cancer screening. Finally, our work suggests coping could be a target in psychological interventions for FH+ women with high levels of perceived breast cancer risk.

Keypoints.

The elevated levels of breast cancer worry among women with a family history of breast cancer (FH+) is well-documented.

Previous research has shown cancer worry to be strongly predicted by FH+ women's perceived breast cancer risk, which is often overestimated.

The influence of perceived breast cancer risk on breast cancer worry may be partially due to women's coping strategies in response to breast cancer risk perceptions (mediation).

Among a sample of 156 FH+ women, women with higher perceived breast cancer risk levels used disengaged coping strategies more frequently (e.g., distraction, disengagement) and had greater breast cancer worry.

The current study found evidence to suggest that women with higher levels of perceived breast cancer risk experience greater breast cancer worry partially due to more frequent use of disengaged coping strategies.

Acknowledgments

Data collection was supported by the National Cancer Institute (K07CA107085, P50CA148143, R25CA92408, K01CA154938-01A1). The content does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Cancer Institute/National Institutes of Health.

References

- 1.Cohen M. Breast cancer early detection, health beliefs, and cancer worries in randomly selected women with and without a family history of breast cancer. Psycho-Oncology. 2006;15:873–883. doi: 10.1002/pon.1018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McGregor BA, Bowen D, Ankerst DP, Andersen MR, Yasui Y, Mctiernan A. Optimism, perceived risk of breast cancer, and cancer worry among a community-based sample of women. Health Psychology. 2004;23:339–344. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.23.4.339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Transactional theory and research on emotions and coping. European Journal of Personality. 2006;1:141–169. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Albano DL, Alderman K, Dolan ED, Mcgregor BA. Recruitment into the Health SMART Study: A randomized intervention trial on the effects of stress management on immune function among women at risk for breast cancer. Contemporary Clinical Trials. Under review. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weinstein ND. Accuracy of smokers’ risk perception. Nictoine & Tobacco Research. 1999;1:S123–130. doi: 10.1080/14622299050011721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lerman C, Trock B, Rimer BK, Jepson C, Brody D, Boyce A. Psychological side effects of breast cancer screening. Health Psychology. 1991;10:259–267. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.10.4.259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weiss D. The Impact of Event Scale: Revised. In: Wilson J, Tang C-K, editors. Cross-Cultural Assessment of Psychological Trauma and PTSD. Springer; US: 2007. pp. 219–238. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carver CS. You want to measure coping but your protocol's too long: Consider the Brief COPE. International Journal of Medicine. 1997;4:92–100. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm0401_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Preacher K, Hayes A. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods. 2008;40(3):879–891. doi: 10.3758/brm.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Turner-Cobb JM, Bloor LE, Whittenmore AS, West D, Spiegel D. Disengagement and social support moderate distress among women with a family history of breast cancer. Breast Journal. 2006;12:7–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1075-122X.2006.00178.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]