Abstract

Objectives

The purpose of this pilot study was to describe patterns of alcohol consumption among continuing care retirement community(CCRC) residents and to explore the role of drinking motives and affective states on drinking context and consumption.

Method

We utilized a phone-based daily diary approach to survey older adults about their daily alcohol consumption, context of drinking (e.g. drinking alone), positive and negative affect, and their motives for drinking. Data were analyzed descriptively, and regression models were developed to examine associations between sociodemographic factors, affect, drinking context and motives, and alcohol consumption.

Results

CCRC residents drank most frequently at home and were alone almost half of drinking days on average, although the context of drinking varied considerably by participant. Problem alcohol use was rare, but hazardous use due to specific comorbidities, symptoms and medications, and the amount of alcohol consumption was common. Respondents endorsed higher social motives for drinking and lower coping motives. Social motives were associated with decreased likelihood of drinking alone, but negative affect was associated with decreased likelihood of drinking outside one’s home. Coping and social motives were associated with greater consumption, and higher positive affect was associated with lower consumption.

Conclusion

Among CCRC residents, alcohol use may be socially motivated rather than motivated by coping with negative affect. Future research should examine other motives for drinking in older adulthood. Evaluation of older adults living in CCRCs should include attention to health factors beyond problem use as other forms of hazardous use may be common in CCRCs.

Keywords: alcohol consumption, continuing care retirement community, drinking motives, positive affect, negative affect

Introduction

Continuing care retirement communities (CCRCs) provide a variety of residential options for older adults, offering a unique setting with a range of services that are responsive to changing care needs as one ages. Since the 1990s, there has been a rapid growth in the construction of CCRCs, and there are now approximately 1900 nation-wide (Zarem, 2010). CCRCs represent a unique setting for aging-in-place (Resnick, 2003b), and provide residents the ability to stay at one facility even as their health needs change (Shippee, 2009). These facilities offer a single source for long-term care needs, including independent housing, assisted living, and nursing services (American Association of Retired Persons, 2013).

With convenient access to alcohol, drinking may be commonplace for the majority of residents of CCRCs (Resnick, 2003a). Yet, even with the rapid growth of CCRCs in recent years, little research has focused on alcohol use in these settings. Instead, much of the extant research has focused on residential retirement communities, such as Leisure World (Adams, 1995; Paganini-Hill, Kawas, & Corrada, 2007), rather than CCRCs. In some instances, the drinking quantity and frequency of drinking were found to be higher in these semi-structured communities than within general population-based samples (e.g. Adams, 1996). Other research has focused on assisted living programs; for example, Castle, Wagner, Ferguson-Rome, Smith, and Handler (2011) surveyed nurses’ aides who worked in assisted living programs in Pennsylvania. The aides reported that they believed that a majority of residents drank alcohol and that 34% drank daily. Aides in the study believed that 28% of residents ‘made poor choices for alcohol consumption’ and 11% had ‘alcohol abuse problems’. Although study findings are somewhat limited in their reliability due to collateral reporting and poorly defined measures of alcohol use, they remain compelling. Further investigation of alcohol use within different types of retirement communities is needed to better understand whether there are unique patterns of and motives for alcohol use, enabling optimal design of interventions for these settings.

Alcohol and health among older adults

To understand the importance of alcohol use in CCRCs, it is important to recognize the relationship between alcohol use and aging. Alcohol consumption tends to decrease as people age (Moore et al., 2005). However, compared to younger adults, older adults may be at higher risk even while consuming less alcohol because they have higher blood alcohol levels for a given dose of alcohol and have increased brain sensitivity to the effects of alcohol (Vestal et al., 1977). Because of these risk factors, recommended drinking limits for persons aged 65 years and older are lower than for younger individuals; guidelines suggest no more than seven drinks per week and no more than three drinks on a given day (National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism [NIAAA], 2010). Individuals who cross that threshold are considered ‘at-risk’. Older adults also have greater medical comorbidity and take more medications that may increase risks associated with alcohol use (Moore, Whiteman, & Ward, 2007) compared with other age groups. Using this broader definition of risk (i.e. consumption and comorbidities and medications), Moore et al. (2006) identified 18% of men and 5% of women (age 60+) in a nationally representative sample as at-risk drinkers.

Conversely, there are known health benefits of drinking among individuals who do not drink heavily and for whom alcohol is not contraindicated. Low to moderate use of alcohol can lead to positive health outcomes related to cardiovascular disease (Corrao, Rubbiati, Bagnardi, Zambon, & Poikolainen, 2000), cognitive functioning (Stott et al., 2008), and mortality (McCaul et al., 2010). Alcohol use at moderate levels is also linked to decreased functional impairment for older adults (Karlamangla et al., 2009).

Although research has focused on the health effects of alcohol use among older drinkers, less is known about alcohol use among older adult residents of CCRCs and similar independent living settings. More in-depth approaches are necessary to investigate drinking among older adults in these living situations. Psychosocial factors such as drinking motives may be important as these may influence the extent to which alcohol use is an unhealthy response to psychosocial issues such as depression. Conversely, alcohol use may be important as a means of socialization, a core component of successful aging (Depp & Jeste, 2006).

Older adults, drinking motives, and affective states

Drinking motives theory focuses on proximal reasons people drink (Cooper, 1994), which may help us understand alcohol consumption among CCRC residents. These motives can be categorized as a positive reinforcement, such as drinking for social and enhancement reasons, or as a negative reinforcement, such as coping and conformity reasons (Cooper, 1994). These motives are seen as a result of the direct pharmacological effects of drinking and/or the ‘instrumental’ effects of drinking (e.g. social conformity or social enhancement) (Cox & Klinger,2004). If individuals have expectations about the effects of drinking, then their motives will reflect those expectancies. For instance, if alcohol is perceived as a method of decreasing tension, an individual will drink to reduce tension. Alternatively, beliefs about the enhancement or social effects of alcohol (e.g. alcohol facilitates socializing) will be consistent with drinking motives focused on attaining positive experiences. Although much of the research on drinking motives has focused on adolescents and young adults, Cooper’s theory provides a broader conceptualization of the proximal factors associated with alcohol use.

In drinking motives theory, negative affective states are central to understanding alcohol use. Alcohol use among older adults is theorized as a means of coping with painful life experiences and other forms of psychological distress (Folkman, Bernstein, & Lazarus, 1987). Overall, findings in this area vary by the cause of the affective state (Glass, Prigerson, Kasl, & Mendes de Leon, 1995), one’s coping repertoire (Bacharach, Bamberger, Sonnenstuhl, & Vashdi, 2008), drinking history, and measurement of alcohol use (Sacco, Bucholz, & Harrington, 2014). Much less attention has been focused on positive reinforcement motives and drinking among older adults or the notion that alcohol use among older drinkers is motivated by social or enhancement motives rather than coping motives.

Using drinking motives theory as a conceptual framework, we explored alcohol use among older adults in a CCRC. First, we investigated relations between drinking motives (e.g. social) and context of drinking, such as whether a person drank alone or drank outside of their home. Second, we hypothesized that negative affect (as both time-invariant and time-varying covariates) and coping motives (as a time-invariant covariate) would be associated with increased drinking and that positive mood and social motives would be associated with lower levels of consumption. In this study, drinking motives are stable characteristics of the individual that may influence drinking habits. Negative and positive affect are conceptualized as time varying factors that impact the likelihood that one will consume alcohol. Together we conceived of drinking motives interacting with affective states to influence consumption, such as individuals with high coping motives being particularly likely to drink as a result of negative affectivity and, conversely, people with social motives being more likely to drink for social or enhancement reasons. We endeavored to explore these associations of drinking motives in light of the dynamic nature of mood and affect by measuring daily variations in affective states.

Method

Study design and sample

This was a descriptive pilot study conducted at one CCRC located in the Washington, DC suburban area with participants who resided within the independent living level of care. The CCRC has more than 2500 residents with most (88%) in independent living, 8% in assisted living, and 4% in a nursing home; there are multiple venues where alcohol is served. Participants were recruited for this study via flyers, pamphlets, and informational videos. Inclusion criteria included being a current drinker (defined as having an alcoholic beverage within the last two weeks), residing independently within the CCRC, English fluency, and the ability to communicate over the telephone. We focused on independent living as residents at this level of care likely had less disability and greater access to alcohol. Individuals were excluded from the study if they displayed clinically significant cognitive decline as measured by the Mini-Cog Screen (Borson, Scanlan, Chen, & Ganguli, 2003). Of the 81 people who expressed an interest in participating, 77 (95%) were eligible. Among eligible participants, 72 (89%) consented to participate, 3 refused, and 2 were lost to follow up before consenting to participate; 71 (99%) of those who consented to participate completed all aspects of the study. One individual did not complete the eight days, reporting that the protocol was too burdensome.

Procedures

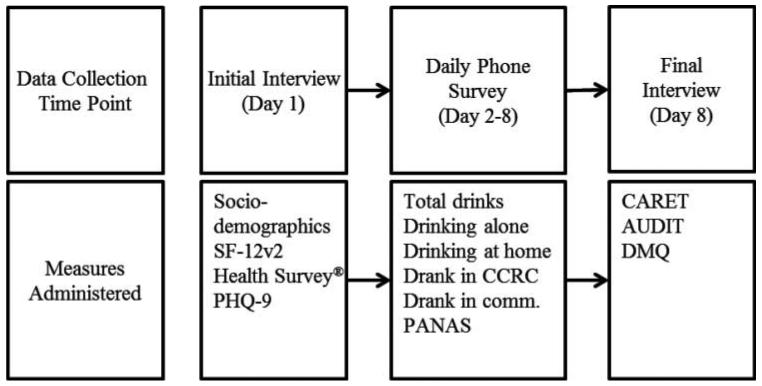

Data were collected from participants in three phases by research assistants: (1) an initial face-to-face interview on day 1, (2) daily surveys administered via telephone on days 2–8, and (3) a final daily survey and telephone interview on day 9 (see Figure 1 for the measures at each phase). The initial face-to-face interview consisted of a Mini-Cog test used for eligibility (Borson et al., 2003), the consent process, and a structured survey instrument. Participants were called every day for eight days beginning the day after the initial interview. During these telephone calls, participants were surveyed about their activities, emotions, and drinking behaviors from the day previous to the call. The final telephone interview included questions about drinking motives, at-risk use of alcohol, and alcohol history. We opted for one-day retrospective phone calls based on pilot research conducted at a different CCRC where handheld devices or written diaries were perceived as being too burdensome among individuals in this age group, and that a morning phone call asking about the previous day was the most feasible option for older adults (Sacco, Smith, Harrington, Svoboda, & Resnick, in press)

Figure 1.

Data collection process.

Four research assistants and the lead author collected daily diary information in a total of 569 phone contacts. Two doctoral level research assistants were responsible for 70% of the daily phone contacts, with the lead author personally making 20% of calls, and two master’s level trainees conducting the final 10%. All interviewers were trained by the primary author on scripted phone surveys and in-person interviews. The lead author observed each research assistant conducting in-person and phone-based interviews on multiple occasions.

Initial face-to-face interview measures

Sociodemographic variables included education, age (in years), gender (0 = female, 1 = male), marital status, and length of residence (in years) at the CCRC.

Health disability

The Medical Outcomes Study SF-12v2® (McHorney, Ware, & Raczek, 1993; Ware & Sherbourne, 1992) was used as a general health screening tool to measure dimensions of health disability over the past four weeks. The SF-12v2® is designed to yield a population-based norm of 50 on a scale of 1–100 with a standard deviation of 10 and contains two major subscales, the Physical Component Scale (PCS) and the Mental Component Scale (MCS). The SF-12v2® is a valid and reliable measure of health status for older adults (Resnick & Nahm, 2001).

Depressive symptoms

The Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9; Kroenke, Spitzer, & Williams, 2001) was used to measure the presence and severity of depressive symptoms. The PHQ-9 contains nine items that ask about the frequency of DSM-IV (Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: Edition IV)-based depression symptoms over the past two weeks. Response options range from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day). Levels of depressive symptoms can be derived from the sum of the nine items: minimal symptoms (0–4), mild symptoms (5–9), moderate symptoms (10–14), and moderately severe symptoms (15–19) and severe symptoms (20+). The PHQ-9 displays good reliability and is a valid measure C of depressive symptoms among older adults in primary care (Phelan et al., 2010). Internal consistency for the current study was acceptable (α = .73).

Daily telephone call measures

Alcohol consumption

Participants were queried regarding drink consumption on the previous day using a standard drink graphic from the NIAAA (2010) provided to them during the in-person interview. In the United States, a standard drink is 0.6 ounces or 14 grams of pure alcohol. This is roughly equivalent to 12 ounces of beer, 8–9 ounces of malt liquor, 4–6 ounces of wine, 3–4 ounces of fortified wine, 2–3 ounces of liqueur or aperitif, or 1.5 ounces of brandy or spirits (National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, 2005). They were also asked about where they were when they drank (i.e. in their home, somewhere else in the CCRC, or in the larger community) and whether they drank alone.

Positive and negative affect

The Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) Short-Form (Mackinnon et al., 1999; Watson, Clark, & Tellegen, 1988) was administered daily. The PANAS Short-Form scale is made up of 10 items, including 5 positive (e.g. excited) and 5 negative (e.g. scared) adjectives that represent dimensions of subjective well-being (Kercher, 1992). The respondents rated their level on these items from 1 (not at all or very slightly) to 5 (extremely) with the previous day as the time-frame. Scores were averaged for both the positive and negative subscales. Internal consistency values for this study were acceptable at α = .70 for positive affect and α = .76 for negative affect. Following Curran and Bauer (2011), PANAS positive and negative affect scales were recoded to create individual mean positive and negative affect scores and deviation scores from each person’s mean on each day. The within person variable represents the level of variation from his or her average positive and negative affect each day. The between person variation quantifies each individual’s mean level of positive and negative affect across the eight days data were collected.

Final telephone interview measures

Drinking motives

Drinking motives were assessed using the Drinking Motives Questionnaire Revised Short-Form (DMQ-R SF; Kuntsche & Kuntsche, 2009) based on the measure originally developed by Cooper (1994). The DMQ measures four types of drinking motives: enhancement, social, conformity, and coping. Enhancement motives refer to drinking to enhance positive mood and social motives refer to drinking for social reasons. Coping refers to drinking to manage negative emotional states and conformity motives are focused on drinking to fit in a specific group. In the DMQ, items relate to the frequency of drinking for specific reasons (e.g. ‘how often do you drink to cheer you up when you are in a bad mood’) over a 12-month timeframe. In the short form of the DMQ, 12 questions are asked, with 3 response options (0 = never, 1 = sometimes, 2 = almost always). We created and scores using the mean values for each subscale. The DMQ measure displays acceptable validity in older adults (Gilson et al., 2013). Internal consistency for the coping and social subscales was acceptable in this study at .74 and .79, respectively. However, internal consistency reliability for the enhancement and conformity subscales was problematic in this study with values well below the acceptable range for Cronbach’s α (.48 and .51, respectively); therefore, these subscales were not included in analyses.

At-risk and unhealthy alcohol use

The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) (Babor, Higgins-Biddle, Saunders, & Monteiro, 2001) and the Comorbidity-Alcohol Risk Evaluation Tool (CARET) (Moore, Beck, Babor, Hays, & Reuben, 2002) were used to screen for unhealthy drinking measured over a 12-month timeframe. The AUDIT is a 10-item measure designed to identify hazardous and harmful drinking in the general population. (Allen, Litten, Fertig, & Babor,1997; Reinert & Allen, 2002); a score of 8 or higher on the AUDIT indicates hazardous or at-risk use. The AUDIT is a broad alcohol screening measure designed for general population use.

Conversely, the CARET was used to assess areas of unhealthy alcohol use specific to older drinkers. The CARET includes quantity and frequency variables and other indicators from the AUDIT, but goes beyond them by assessing for alcohol consumption along with comorbid medical conditions, alcohol use with medications that are contraindicated, exceeding recommended consumption guidelines specific to older adults, and driving after drinking. The CARET, like the AUDIT, measures at-risk drinking, but evaluates consumption and health specific to older adults (see Table 1; Barnes et al., 2010). Because the CARET measures drinking risks across a continuum of use and sets guidelines that are elder specific, it is an appropriate measure to use specifically with CCRC residents. Four dichotomous indicators of alcohol related risk were derived from this measure: exceeding alcohol consumption guidelines, hazardous alcohol and medication co-use, hazardous alcohol with comorbidities, and driving while under the influence.

Table 1.

Risk indicators in the CARET.

| Item | Risk indicators |

|---|---|

| Consumption risk only |

|

| Disease comorbidity | If one has liver disease or pancreatitis

If one has gout or depression

If one has high blood pressure of diabetes

|

| Medication interaction | If one take medications that may cause bleeding, dizziness, or sedation or medication for gastroesophageal reflux, ulcer disease, or depression

If one takes medications for hypertension

|

| Symptom comorbidity | Person sometimes has problems with sleeping, falling, memory,

heartburn, stomach pain, nausea, vomiting, or feel sad /blue

|

| Drinking and driving | Often have problems with sleeping, falling, memory, heartburn, stomach pain, nausea, vomiting or feel sad /blue

|

Note: Data adapted from Barnes et al. (2010).

Data analysis

Data analysis was conducted in three steps. First, univariate and bivariate statistics were generated to describe the sample sociodemographic and person level drinking characteristics. Next, we analyzed the context of drinking, specifically drinking alone and drinking outside one’s home (defined as somewhere else in the CCRC or in the community). Two logistic regression models were used to examine sociodemographic, affective, and motivational influences on drinking alone and drinking outside of the home. Independent variables in these models included sociodemographic variables (i.e. gender, age, marital status, SF-12v2® score), PANAS positive and negative affect (measured as within person deviation and between person differences) and drinking motives. Finally, we estimated two Poisson regression models to predict the number of drinks consumed in a given day. In the first model, sociodemographic variables and PANAS variables were included to examine the role of positive and negative affect on the number of drinks consumed. In the second model, social and coping drinking motives were added.

Generalized estimating equations (GEE; PROC GEN-MOD; SAS Institute Inc, 2008; Zeger & Liang, 1986) with a first-order autoregressive (AR1) correlation structure were estimated for all regression models due the nesting of days within persons. GEE is a regression method that addresses violations to the assumption of independence (i.e. correlated residuals because the data are longitudinal). In GEE, within person errors are allowed to correlate over time; model estimates and standard errors adjust for these correlations. The autoregressive correlation structure estimates correlated errors that are symmetrical and strongest on observations (i.e. days) closest to each other and less correlated as they are farther apart (Hanley, Negassa, Edwardes, & Forrester, 2003).

Results

Sociodemographic characteristics

In the final sample (n = 71), the average age of participants was over 80 years old and almost two-thirds were women (see Table 2). The vast majority of participants were White and college educated. The sample was primarily currently married or widowed. Mean participant SF-12v2® health scores were 46.87 (SD = 10.29), indicating the sample had somewhat poorer health than the general population of adults (t = 2.56, p =.013).

Table 2.

Demographics of CCRC residents (n = 71).

| Variable | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Female | 45 | 63.4 |

| White /Caucasian | 67 | 94.4 |

| Marital status | ||

| Married‡ | 27 | 38.0 |

| Widowed | 35 | 49.3 |

| Divorced | 6 | 8.5 |

| Never married | 3 | 4.2 |

| Depressive symptoms (PHQ-9) | ||

| None | 61 | 85.9 |

| Minimal | 6 | 8.5 |

| Mild | 3 | 4.2 |

| Moderate | 1 | 1.4 |

| AUDIT hazardous use (8+) | 2 | 2.8 |

| CARET alcohol risk | ||

| Consumption risk only | 33 | 46.5 |

| Disease comorbidity | 28 | 39.4 |

| Medication interaction | 44 | 62.0 |

| Symptom comorbidity | 29 | 40.8 |

| Drinking and driving | 3 | 4.2 |

Married or living as if married; PHQ-9 = Patient Health Questionnaire; AUDIT = Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test; CARET = Comor-bidity-Alcohol Risk Evaluation Tool.

Sample demographic characteristics were similar to those of independent living residents at the CCRC, however the study sample was slightly younger (82 vs. 85 years), lived at the site for slightly shorter durations (5.3 vs. 5.6 years), and contained lower percentages of women (63% vs. 67%) and married persons (37% vs. 49%) than the CCRC population as a whole. Differences between the sample and the overall census of the CCRC were likely a result of two factors. We recruited individuals who were current drinkers, a distinct subpopulation that are more likely to be male and younger from population studies of older adults (Moore et al., 2009). Also, all participants resided within independent living, meaning they were healthier and likely younger than nursing home and assisted living participants. In this sense, the study is generalizable to current drinking older adults in CCRCs.

Alcohol-related characteristics

The average percentage of drinking days among participants was 57% (or about four days per week) and the average number of drinks per drinking day was 1.28 (SD = .68; see Table 3). People drank when they were alone 43% of the time on average, with variability (SD = 37.1%) among individuals. People drank most commonly in their apartments (68.71%) or somewhere else in the facility (26.36%). The lowest proportion of drinking occurred off-site (8.27%).

Table 3.

Sample description of CCRC residents (n = 71).

| M | SD | Minimum | Maximum | Range | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 82.00 | 7.23 | 61 | 92 | 31 |

| Length of time at CCRC (years) | 5.32 | 2.87 | .33 | 11 | 10.67 |

| SF-12v2® Physical Component Scale | 46.87 | 10.29 | 16.75 | 60.85 | 44.10 |

| SF-12v2® Mental Component Scale | 54.28 | 7.81 | 33.27 | 68.11 | 34.84 |

| Alcohol use | |||||

| Mean drinks consumed on drinking days | 1.28 | .68 | .5 | 6 | 5.5 |

| Mean of proportion of drinking days | 57.04% | 26.26% | 0 | 100 | 100 |

| Mean of proportion of drinking alone | 43.15% | 37.10% | 0 | 100 | 100 |

| Mean of proportion of drinking in the home | 68.71% | 35.50% | 0 | 100 | 100 |

| Mean of proportion of drinking at the CCRC | 26.36% | 34.43% | 0 | 100 | 100 |

| Mean of proportion of drinking somewhere outside the CCRC | 8.27% | 16.60% | 0 | 66.67 | 66.67 |

| Positive and negative affect† | |||||

| Sample mean of ave. positive affect | 14.38 | 2.57 | 7.63 | 19 | 11.38 |

| Sample mean of ave. negative affect | 6.38 | 1.41 | 4.87 | 12.63 | 7.75 |

| Drinking motives‡ | |||||

| Coping | .63 | .89 | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| Social | 2.11 | 1.69 | 0 | 6 | 6 |

Measured by the PANAS.

Measured by the DMQ-R SF.

Hazardous alcohol use based on AUDIT scores was uncommon (3%) in the sample (see Table 2). The CARET identified larger percentages of at-risk drinkers (see Table 2); 4% to 62% of participants endorsed specific at-risk drinking patterns such as drinking above NIAAA (2010) drinking guidelines and drinking with comorbid conditions or medication that may interact with alcohol. Over 60% of participants endorsed a medication interaction at-risk drinking pattern, making it the most common type of at-risk drinking. Within the sample, social motives showed the highest mean values, but coping-related drinking were weaker motives for drinking in this sample (see Table 3).

Mood and depressive symptoms

Table 3 shows the mean scores for positive and negative affect on the PANAS Short Form. Participants displayed higher mean levels of positive affect than negative affect. Based on the PHQ-9, 84% of the sample did not endorse any depressive symptoms, 8% endorsed minimal depressive symptoms, and only 6% endorsed mild symptoms or greater. Similarly, the MCS of the SF-12v2® indicated 9% at risk of depression, but MCS (M = 54.28) scores were above the norm of 50 for the general population.

GEE models

Results from the GEE models examining sociodemographic factors, affect, and drinking motives in predicting the context of drinking (drinking alone or in the community) are presented in Table 4. Current marital status and social drinking motives emerged as significant predictors of drinking alone. For married individuals, the odds of drinking by themselves were 85% lower (ORadj = .15; p < .001) than for those who were not married. Social drinking motives were inversely associated with drinking alone (ORadj = .73; p = .001), with each one-point increase in social motives associated with a 27% decrease in the odds of drinking alone. All other predictors in the model were not associated with drinking alone.

Table 4.

GEE logit models predicting the context of drinking on days when drinking (n = 324a).

| Drinking alone |

Drinking outside of one’s home |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b | se | z | P | ORb | b | se | z | P | ORb | |

| Female gender | .255 | .367 | .69 | .489 | – | .202 | .414 | 1.01 | .625 | – |

| Age | .039 | .025 | 1.63 | .104 | – | −.036 | .032 | −1.13 | .260 | – |

| Currently married | − 1.91 | .445 | − 4.30 | <001 | .15 | −.210 | .495 | −1.18 | .670 | – |

| SF-12v2® Physical Component Scale | .015 | .020 | .76 | .448 | – | −.023 | .018 | −1.26 | .201 | – |

| Positive affect†(within person) | −.040 | .055 | −.73 | .463 | – | .013 | .045 | .25 | .804 | – |

| Positive affect†(between person) | −102 | .073 | −1.41 | .159 | – | .082 | .086 | .96 | .339 | – |

| Negative affect†(within person) | .143 | .085 | 1.68 | .093 | – | −.174 | .085 | − 2.06 | .039 | .84 |

| Negative affect†(between person) | .192 | .158 | 1.21 | .226 | – | −.125 | .133 | −.94 | .350 | – |

| Coping motives‡ | −187 | .176 | −1.06 | .289 | – | .102 | .170 | .60 | .548 | – |

| Social motives‡ | −.308 | .095 | − 3.24 | .001 | .73 | .076 | .100 | .75 | .451 | – |

| Model fit | QIC = 402.985; QICu = 392.134 | QIC = 411.177; QICu = 397.418 | ||||||||

Measured by the PANAS.

Measured by the DMQ-R SF.

n = 324 for this analysis based on subsamples of drinking days only.

OR only presented for significant effects.

Only one factor predicted drinking outside one’s home within person negative affect, which was associated with a decreased likelihood of drinking outside of one’s home in the CCRC or in the community (ORadj = .84; p = .039). On average, a one-point increase in deviation from one’s negative mean value on a given day was associated with a 16% decrease in the odds of drinking outside one’s home.

Results from the two models exploring the extent to which sociodemographic factors, positive and negative affect, and drinking motives influence the amount people drank on a given day are reported in Table 5. Adjusting for sociodemographic factors (Model 1), higher levels of between person positive affect were associated with less drinking (IRR [Incident Risk Ratio] = .90; p = .028). A one-point increase in one’s average PANAS positive affect scale was associated with 10% lower drinking. When drinking motives were included in the model (Model 2), the role of positive affect persisted (IRR = .91; p = .002). Although there was some decrease in model fit overall based on quasi-likelihood information criterion indices (QIC and QICu; Pan, 2001), both coping and social drinking motives were significant predictors, with each one-point increase in coping drinking motives associated with a 17% increase (IRR = 1.17; p = .038) and each one-point increase in social motives associated with a 16% increase (IRR = 1.16; p .003) in drinking. In addition, we found that lower SF-12v2® PCS disability was associated with greater drinking (IRR = 1.01; p = .035), with each 10-point increase in the SF-12v2® associated with a 10% greater count of drinks on a given day.

Table 5. GEE Poisson models predicting the count of alcoholic beverages (n = 563a).

| Model 1: sociodemographic and PANAS |

Model 2: DMQ added to model |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | b | se | z | P | IRR | b | se | z | P | IRR |

| Gender | −.124 | .217 | −.57 | .568 | .884 | −.216 | .174 | −1.24 | .215 | .81 |

| Age | −.024 | .017 | −1.36 | .174 | .977 | −.023 | .140 | −1.66 | .100 | .98 |

| Currently married | .068 | .272 | .25 | .802 | 1.07 | .123 | .214 | .57 | .567 | 1.13 |

| SF-12v2® PCS | .016 | .010 | 1.65 | .100 | 1.02 | .018 | .009 | 2.11 | .035 | 1.01 |

| Positive affect† (within person) | .019 | .016 | 1.17 | .242 | 1.02 | .019 | .016 | 1.15 | .249 | 1.02 |

| Positive affect† (between person) | −.108 | .029 | − 2.19 | .028 | .900 | −.097 | .032 | − 3.07 | .002 | .91 |

| Negative affect† (within person) | −.027 | .024 | −1.10 | .271 | .973 | −.030 | .026 | −1.17 | .250 | .97 |

| Negative affect† (between person) | −.093 | .064 | −1.44 | .149 | .911 | −.122 | .064 | −1.92 | .055 | .89 |

| Coping motives‡ | .158 | .075 | 2.08 | .038 | 1.17 | |||||

| Social motives‡ | .144 | .050 | 2.88 | .003 | 1.16 | |||||

| Model fit indices | QIC = 1246.265; QICu = 1189.143 | QIC = 1305.159; QICu = 1263.428 | ||||||||

Notes: Models utilized AR(1) autoregressive correlation structure; time (day of the week) included in models as a class variable (not shown); IRR = Incident Risk Ratio;

Measured by the PANAS;

Measured by the DMQ-R SF;

n = 563 based on data from 66 participants over 8 days and 5 participants with data over 7 days.

We were interested in exploring the extent to which motivational effects of alcohol use varied, based on the affective makeup of the individual. To see if coping motives affected consumption among those with higher negative affectivity and social motives among those with higher positive affectivity, we added two interaction terms (not shown). Neither interaction term was significant, suggesting that the influence of drinking motives was relatively uniform across the levels of negative and positive affect.

Discussion

Individuals reporting higher levels of positive affect drank less than those with lower levels of positive affect and although coping and social motives were associated with greater consumption, drinking to cope did not confer a specific risk in this sample. Within person variations, both positive and negative affect were not associated with differences in drinking behavior. Negative or positive affect on a given day was not associated with increased drinking for that day.

Independent living and drinking behavior

Our findings suggest that AUDIT-defined hazardous drinking is rare in this sample, but alcohol use with symptom and disease comorbidities and/or use with contrain-dicated medications (based on the CARET) are more common than heavy drinking or problem drinking (identified by the AUDIT). Findings suggest potential program development opportunities for CCRCs to increase awareness and education around drinking with specific disease comorbidities or medication contraindications.

Despite these identified comorbidities and that nearly half of respondents in the study drank over the recommendations set by NIAAA (2010), few older adults endorsed specific alcohol-related problems. These findings mirror national studies that have found low prevalence of problem or disordered drinking among adults over age 65 (Blazer & Wu, 2009b; Grant et al., 2004), but higher prevalence of at-risk drinking due to consumption levels above guidelines (Barnes et al., 2010; Blazer & Wu, 2009a). Among older adults, the relationship of elder specific drinking guidelines to later health consequences remains uncertain, with some studies demonstrating mortality effects (Moore et al., 2006) and other studies more equivocal about elder specific drinking limits (Lang, Guralnik, Wallace, & Melzer, 2007).

Given the proportion of drinking alone, it would appear that context specific factors such as peer influence and alcohol availability may be less important in influencing drinking among older adults than younger groups. Unlike in adolescent populations (Paschall, Grube, Thomas, Cannon, & Treffers, 2012), alcohol availability may not affect use, and older adults may not be as influenced by peer behavior in the same way as younger populations are. It is possible that peer influences among older adults are a function of social networks more than context specific effects. Older adults who consume alcohol at higher levels may have different social networks (due to health, relative age, etc.) than those who drink less or who abstain completely. The peer effect in older adult drinking may also be different for heavy or problem drinkers than for low risk drinkers (Lemke, Brennan, Schutte, & Moos,2007). Nonetheless, our qualitative research suggests that older adults themselves perceive that their drinking is influenced by their peers (Burruss, Sacco, & Smith, in press). Because much of the work in this area is retrospective and cross-sectional, further research is needed to unpack complex relationships between alcohol use, social networks, contextual specific factors, and drinking.

Drinking motives and older adults

Interestingly, although a large proportion of drinking was done alone, this sample endorsed social motives at the highest levels and coping motives at much lower levels in contrast to the notion that drinking is a means of coping among older adults. Our finding is consistent with other research on older adults that has identified much higher endorsement rates for social motives than for coping motives (Gilson et al., 2013). In our study, social motives were negatively associated with drinking alone suggesting that stated drinking motivation is consistent with behavior.

Both social and coping motives were associated with the amount consumed during a given day. One other published study has identified associations between coping motives and alcohol-related problems among older adults, as well as between social motives and quantity, frequency, and binge drinking (Gilson et al., 2013). Although relatively little is known about the motives for using substances among older adults, it has been proposed that older adults primarily use substances to cope with life changes or transitions, loss, depression, and loneliness – aspects thought of as unique to late life (Schonfeld & Dupree,1991). This literature, however, has focused on older adults’ substance problems and more research is needed on motives for drinking among older adults with less severe (e.g. hazardous) or no drinking problems.

Positive and negative affect and alcohol consumption

Much research has focused on approaches to drinking that emphasize alcohol use as a form of tension reduction among older adults, including the stress and coping and self-medication models (Brennan, Schutte, & Moos,1999; Bryant & Kim, 2013; Hunter & Gillen, 2006; Sacco, Bucholz, & Harrington, 2014). The underlying premise of this research is that negative affectivity in the form of stress or stressful events precipitates drinking (Holahan, Moos, Holahan, Cronkite, & Randall, 2001). Much of the research in this area has tended to focus on either cross-sectional analysis or longer term longitudinal assessment of the role of stress and coping on use and consequences. We did not find temporal relationships between negative affect or positive affect and the amount consumed on a given drinking day. Residents with higher mean levels of positive affect drank less.

There are a number of factors that may explain this finding. Older adults living in the context of a CCRC may experience less mood variability (Carstensen et al., 2011) than younger age groups. In the absence of marked affective variability, reactive drinking may be less common. The relationship between positive and negative affect is also more complex in older adults than it is among younger groups in that positive and negative emotions may coexist more readily (Grüuhn, Lumley, Diehl, & Labouvie-Vief, 2013).

Also, the study sample was made up of older drinkers who did not report alcohol-related problems. Drinking to cope with negative affect may be unique to younger populations of older adults or those with problem drinking histories (Cooper, Frone, Russell, & Mudar, 1995; Gilson et al., 2013). Future research could explore motivational models of drinking among older adults to discern whether daily positive and negative affect influences consumption among problem drinkers. This study suggests that negative affect does not impact consumption but that those with more positive affect drink less.

Limitations

Although this study provides novel insights into drinking patterns specific to older adults, our findings should be interpreted in light of specific limitations. Our sample of older adults was recruited from a single CCRC potentially limiting generalizability to the general population of older adults or to those with identified problem drinking. However, findings may be relevant to a population of current drinking older adults living in CCRCs and other congregate forms of living. A larger number of more representative studies are needed to understand affective and motivational factors that can be generalized to the older adult population living in CCRCs.

Because data collection occurred one time per day, we did not explore the impact of within day variation in affect. Similarly, older adults were asked about the previous day, rather than momentary affect. Recall bias under this protocol was likely less than using methods that require recall over a longer timeframe, but the potential for recall bias was still present. The intensive longitudinal approaches used in this study may induce reactivity among participants (Bolger & Laurenceau, 2013, p. 21), but the use of a daily response schedule may be associated with less reactivity due to habituation (Bolger, Davis, & Rafaeli, 2003). Drinking motives were treated as time invariant, but it is possible that motivations for drinking could vary over time in a given individual.

Conclusions

Alcohol use among older adults living in CCRC settings is largely motivated by the desire for socialization, although residents also report drinking to cope. Harmful drinking may be rare among older adults in these settings but hazardous drinking based on comorbidities, concurrent medication use, and other aging-specific factors may be common. Future research on drinking among those in CCRCs should consider the extent to which hazardous use, broadly defined, leads to harmful outcomes. In considering the role of mood, affect, and drinking among older adults, future research should further explore the relationship between drinking and context with an emphasis on identifying factors that are associated with unhealthy drinking.

Acknowledgments

Funding

This study was supported by a John A. Hartford Scholar Award (Sacco) and by K24AA15957 (awarded to Dr Moore) from the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism, and by P30AG10415 and P30AG028748 and P30AG021684 from the National Institute on Aging.

References

- American Association of Retired Persons . About continuing care retirement communities: Learn where they are and how they work. Author; Washington DC: 2013. Retrieved from http://www.aarp.org_relationships_caregiving-resourcecenter_info-09-2010_ho_continuing_care_retirement_communities.html. [Google Scholar]

- Adams WL. Potential for adverse drug-alcohol interactions among retirement community residents. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1995;43(9):1021–1025. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1995.tb05567.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams WL. Alcohol use in retirement communities. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1996;44(9):1082–1085. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1996.tb02943.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen JP, Litten RZ, Fertig JB, Babor T. A review of research on the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) Alcoholism Clinical & Experimental Research. 1997;21(4):613–619. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Babor TF, Higgins-Biddle J, Saunders JB, Monteiro MG. The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test: Guidelines for use in primary care (2nd ed.) World Health Organization; Geneva: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Bacharach S, Bamberger PA, Sonnenstuhl WJ, Vashdi D. Aging and drinking problems among mature adults: The moderating effects of positive alcohol expectancies and workforce disengagement. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2008;69(1):151–159. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes AJ, Moore AA, Xu H, Ang A, Tallen L, Mirkin M, Ettner SL. Prevalence and correlates of atrisk drinking among older adults: The project SHARE study. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2010;25(8):840–846. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1341-x. doi:10.1007/s11606-010-1341-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blazer DG, Wu LT. The epidemiology of at-risk and binge drinking among middle-aged and elderly community adults: National Survey on Drug Use and Health. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2009a;166(10):1162–1169. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09010016. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09010016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blazer DG, Wu LT. The epidemiology of substance use and disorders among middle aged and elderly community adults: National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2009b;17(3):237–245. doi: 10.1097/JGP.0b013e318190b8ef. doi:10.1097/JGP.0b013e318190b8ef. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger N, Davis A, Rafaeli E. Diary methods: Capturing life as it is lived. Annual Review of Psychology. 2003;54:579–616. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145030. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger N, Laurenceau J-P. Intensive longitudinal methods: An introduction to diary and experience sampling research. Guilford Press; New York, NY: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Borson S, Scanlan JM, Chen P, Ganguli M. The Mini-Cog as a screen for dementia: Validation in a populationbased sample. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2003;51(10):1451–1454. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51465.x. doi:10.10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51465.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan PL, Schutte KK, Moos RH. Reciprocal relations between stressors and drinking behavior: A threewave panel study of late middle-aged and older women and men. Addiction. 1999;94(5):737–749. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.1999.94573712.x. doi:10.1046/j.1360-0443.1999.94573712.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant AN, Kim G. The relation between frequency of binge drinking and psychological distress among older adult drinkers. Journal of Aging and Health. 2013;25(7):1243–1257. doi: 10.1177/0898264313499933. doi:10.1177/0898264313499933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burruss K, Sacco P, Smith CA. Understanding older adults’ attitudes and beliefs about drinking: Perspectives of residents in congregate living. Ageing and Society. in press. doi:10.1017/70144686x14000671. [Google Scholar]

- Carstensen LL, Turan B, Scheibe S, Ram N, Ersner-Hershfield H, Samanez-Larkin GR, Nesselroade JR. Emotional experience improves with age: Evidence based on over 10 years of experience sampling. Psychology and Aging. 2011;26(1):21–33. doi: 10.1037/a0021285. doi:10.1037/a0021285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castle NG, Wagner LM, Ferguson-Rome JC, Smith ML, Handler SM. Alcohol misuse and abuse reported by nurse aides in assisted living. Research on Aging. 2011;34(3):321–336. doi:10.1177/0164027511423929. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML. Motivations for alcohol use among adolescents: Development and validation of a four-factor model. Psychological Assessment. 1994;6(2):117. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.6.2.117. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Frone MR, Russell M, Mudar P. Drinking to regulate positive and negative emotions: A motivational model of alcohol use. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;69(5):990–1005. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.69.5.990. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.69.5.990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrao G, Rubbiati L, Bagnardi V, Zambon A, Poikolainen K. Alcohol and coronary heart disease: A metaanalysis. Addiction. 2000;95(10):1505–1523. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.951015056.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox WM, Klinger E. A motivational model of alcohol use: Determinants of use and change. In: Cox WM, Klinger E, editors. Handbook of motivational counseling: Concepts, approaches, and assessment. Wiley; West Sussex: 2004. pp. 121–138. [Google Scholar]

- Curran PJ, Bauer DJ. The disaggregation of withinperson and between-person effects in longitudinal models of change. Annual Review of Psychology. 2011;62:583–619. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.093008.100356. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.093008.100356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Depp CA, Jeste DV. Definitions and predictors of successful aging: A comprehensive review of larger quantitative studies. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 2006;14(1):6–20. doi: 10.1097/01.JGP.0000192501.03069.bc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman S, Bernstein L, Lazarus RS. Stress processes and the misuse of drugs in older adults. Psychology and Aging. 1987;2(4):366–374. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.2.4.366. doi:10.1037/0882-7974.2.4.366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilson K-M, Bryant C, Bei B, Komiti A, Jackson H, Judd F. Validation of the Drinking Motives Questionnaire (DMQ) in older adults. Addictive Behaviors. 2013;38(5):2196–2202. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.01.021. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2013.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass TA, Prigerson H, Kasl SV, Mendes de Leon CF. The effects of negative life events on alcohol consumption among older men and women. Journals of Gerontology: Series B. 1995;50(4):S205–S216. doi: 10.1093/geronb/50b.4.s205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Dawson DA, Stinson FS, Chou SP, Dufour MC, Pickering RP. The 12-month prevalence and trends in DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence: United States, 1991-1992 and 2001-2002. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2004;74(3):223–234. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.02.004. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grüuhn D, Lumley MA, Diehl M, Labouvie-Vief G. Time-based indicators of emotional complexity: Interrelations and correlates. Emotion. 2013;13(2):226–237. doi: 10.1037/a0030363. doi:10.1037/a0030363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanley JA, Negassa A, Edwardes M.D.d., Forrester JE. Statistical analysis of correlated data using generalized estimating equations: An orientation. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2003;157(4):364–375. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf215. doi:10.1093/aje/kwf215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holahan CJ, Moos RH, Holahan CK, Cronkite RC, Randall PK. Drinking to cope, emotional distress and alcohol use and abuse: A ten-year model. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2001;62(2):190–198. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2001.62.190. doi:10.1037/0021-843x.112.1.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter IR, Gillen MC. Alcohol as a response to stress in older adults: A counseling perspective. Adultspan. 2006;5(2):114–126. doi:10.1002/j.2161-0029.2006.tb00022.x. [Google Scholar]

- Karlamangla AS, Sarkisian CA, Kado DM, Dedes H, Liao DH, Kim S, Moore AA. Light to moderate alcohol consumption and disability: Variable benefits by health status. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2009;169(1):96–104. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn294. doi:10.1093/aje/kwn294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kercher K. Assessing subjective well-being in the oldold: The PANAS as a measure of orthogonal dimensions of positive and negative affect. Research on Aging. 1992;14(2):131–168. doi:10.1177/0164027592142001. [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. The PHQ-9. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2001;16(9):606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsche E, Kuntsche S. Development and validation of the Drinking Motive Questionnaire Revised Short Form (DMQ-R SF) Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2009;38(6):899–908. doi: 10.1080/15374410903258967. doi:10.1080/15374410903258967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang I, Guralnik J, Wallace RB, Melzer D. What level of alcohol consumption is hazardous for older people? Functioning and mortality in US and English national cohorts. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2007;55(1):49–57. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.01007.x. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.01007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemke S, Brennan PL, Schutte KK, Moos RH. Upward pressures on drinking: Exposure and reactivity in adulthood. Journal of Studies on Alcohol & Drugs. 2007;68(3):437–445. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2007.68.437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackinnon A, Jorm AF, Christensen H, Korten AE, Jacomb PA, Rodgers B. A short form of the positive and negative affect schedule: Evaluation of factorial validity and invariance across demographic variables in a community sample. Personality and Individual Differences. 1999;27(3):405–416. doi:10.1016/s0191-8869(98)00251-7. [Google Scholar]

- McCaul KA, Almeida OP, Hankey GJ, Jamrozik K, Byles JE, Flicker L. Alcohol use and mortality in older men and women. Addiction. 2010;105(8):1391–1400. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.02972.x. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.02972.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHorney CA, Ware JE, Jr, Raczek AE. The MOS 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): II. Psychometric and clinical tests of validity in measuring physical and mental health constructs. Medical Care. 1993;31(3):247–263. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199303000-00006. doi:10.1097/00005650-199303000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore AA, Beck JC, Babor TF, Hays RD, Reuben DB. Beyond alcoholism: Identifying older, at-risk drinkers in primary care. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;63(3):316–325. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2002.63.316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore AA, Giuli L, Gould R, Hu P, Zhou K, Reuben D, Karlamangla A. Alcohol use, comorbidity, and mortality. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2006;54:757–762. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00728.x. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00728.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore AA, Gould R, Reuben DB, Greendale GA, Carter MK, Zhou K, Karlamangla A. Longitudinal patterns and predictors of alcohol consumption in the United States. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95(3):458–465. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2003.019471. doi:10.2105/ajph.2003.019471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore AA, Karno MP, Grella CE, Lin JC, Warda U, Liao DH, Hu P. Alcohol, tobacco, and nonmedical drug use in older US adults: Data from the 2001/02 National Epidemiologic Survey of Alcohol and Related Conditions. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2009;57(12):2275–2281. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02554.x. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02554.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore AA, Whiteman EJ, Ward KT. Risks of combined alcohol/medication use in older adults. American Journal of Geriatric Pharmacotherapy. 2007;5(1):64–74. doi: 10.1016/j.amjopharm.2007.03.006. doi:10.1016/j.amjopharm.2007.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism . Helping patients who drink too much: A clinician’s guide. National Institutes of Health; Bethesda, MD: 2005. NIH Publication No. 07-3769. [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism . Rethinking drinking: Alcohol and your health. US Department of Health and Human Services; Bethesda, MD: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Paganini-Hill A, Kawas CH, Corrada MM. Type of alcohol consumed, changes in intake over time and mortality: The leisure world cohort study. Age & Ageing. 2007;36(2):203–209. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afl184. doi:10.1093/ageing/afl184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan W. Akaike’s information criterion in generalized estimating equations. Biometrics. 2001;57(1):120–125. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2001.00120.x. doi:10.2307/2676849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paschall MJ, Grube JW, Thomas S, Cannon C, Treffers R. Relationships between local enforcement, alcohol availability, drinking norms, and adolescent alcohol use in 50 California cities. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2012;73(4):657–665. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2012.73.657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phelan E, Williams B, Meeker K, Bonn K, Frederick J, LoGerfo J, Snowden M. A study of the diagnostic accuracy of the PHQ-9 in primary care elderly. BMC Family Practice. 2010;11(63):1–9. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-11-63. doi:10.1186/1471-2296-11-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinert DF, Allen JP. The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): A review of recent research. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2002;26(2):272–279. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.2002.tb02534.x. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnick B. Alcohol use in a continuing care retirement community. Journal of Gerontological Nursing. 2003a;29(10):22–29. doi: 10.3928/0098-9134-20031001-06. doi:10.3928/0098-9134-20031001-06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnick B. Health promotion practices of older adults: Model testing. Public Health Nursing. 2003b;20(1):2–12. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1446.2003.20102.x. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1446.2003.20102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnick B, Nahm ES. Reliability and validity testing of the revised 12-item Short-Form Health Survey in older adults. Journal of Nursing Measurement. 2001;9(2):151–161. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacco P, Bucholz KK, Harrington D. Gender differences in stressful life events, social support, perceived stress, and alcohol use among older adults: Results from a national survey. Substance Use and Misuse. 2014;49(4):456–465. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2013.846379. doi:10.3109/10826084.2013.846379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacco P, Smith C, Harrington D, Svoboda DV, Resnick B. Feasibility and utility of experience sampling to assess alcohol consumption among older adults. Journal of Applied Gerontology. doi: 10.1177/0733464813519009. in press. doi:10.1177/0733464813519009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute Incorporation . SAS6 STAT 9.2 users guide. Author; Cary, NC: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Schonfeld L, Dupree LW. Antecedents of drinking for early- and late-onset elderly alcohol abusers. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1991;52(6):587–592. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1991.52.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shippee TP. ‘But I am not moving’: Residents’ perspectives on transitions within a continuing care retirement community. The Gerontologist. 2009;49(3):418–427. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnp030. doi:10.1093/geront/gnp030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stott DJ, Falconer A, Kerr GD, Murray HM, Trompet S, Westendorp RG, Ford I. Does low to moderate alcohol intake protect against cognitive decline in older people? Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2008;56(12):2217–2224. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02007.x. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.02007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vestal R, McGuire E, Tobin J, Andres R, Norris A, Mezey E. Aging and ethanol metabolism. Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 1977;21(3):343–354. doi: 10.1002/cpt1977213343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware JE, Jr, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Medical Care. 1992;30(6):473–483. doi:10.1007/bf03260127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson D, Clark L, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1988;54(6):1063–1070. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.6.1063. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zarem J. Today’s continuing care retirement community (CCRC) American Seniors Housing Association; Washington, DC: 2010. Retrieved from http://www.leadingage.org/Report_Provides_Information_on_the_Strengths_and_Challenges_of_CCRCs.aspx. [Google Scholar]

- Zeger SL, Liang K-Y. Longitudinal data analysis for discrete and continuous outcomes. Biometrics. 1986;42(1):121–130. doi:10.2307/2531248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]