Abstract

Immune function relies on an appropriate balance of the lymphoid and myeloid responses. In the case of neoplasia, this balance is readily perturbed by the dramatic expansion of immature or dysfunctional myeloid cells accompanied by a reciprocal decline in the quantity/quality of the lymphoid response. In this review, we seek to: (1) define the nature of the atypical myelopoiesis observed in cancer patients and the impact of this perturbation on clinical outcomes; (2) examine the potential mechanisms underlying these clinical manifestations; and (3) explore potential strategies to restore normal myeloid cell differentiation to improve activation of the host antitumor immune response. We posit that fundamental alterations in myeloid homeostasis triggered by the neoplastic process represent critical checkpoints that govern therapeutic efficacy, as well as offer novel cellular-based biomarkers for tracking changes in disease status or relapse.

Keywords: Cancer, Aberrant myelopoiesis, IRF-8, MDSC

Introduction

In two landmark reviews of cancer biology by Hanahan and Weinberg [1, 2], it has become clear that tumors do not grow in a silo and cannot transition to malignancy without the aid of host-derived, extrinsic factors. Molecular interactions between tumor cells, stroma and cells of the immune system shape the character of the tumor microenvironment and alter the aggressive nature of the disease.

It is well recognized that tumor-derived factors (TDFs), cloaked in the form of cytokines, chemokines and inflammatory messengers like prostaglandins, act in paracrine or systemic fashion to ‘reprogram’ non-cancerous host cells to exacerbate rather than ameliorate disease progression [3]. Many of these TDFs are myelopoietic factors or bear myelopoietic activities, making the myeloid compartment a major target of this ‘tumor reconditioning.’ Myelopoiesis is a tightly regulated process of cellular development occurring in the bone marrow. Consequently, chronic exposure of the bone marrow microenvironment to aphysiologic levels of ordinarily tightly regulated myelopoietic-like growth factors corrupts the normal process of myeloid cell development and differentiation.

A hallmark manifestation of cancer-induced myeloid dysfunction is an abundant expansion and accumulation of myeloid cells reflecting virtually all myeloid lineages. Many of the resulting myeloid cell types are either halted at an immature state or, if they undergo maturation, they have functional defects, thus failing to provide meaningful host defense. Often these expanded myeloid populations are termed myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) because of their ability to inhibit innate and adaptive immune responses. Therefore, if we can improve our understanding of the molecular bases by which neoplasia alters normal myelopoiesis, this may improve how we utilize anticancer therapies that require a competent myeloid compartment, which is a focus of this review.

The myeloid compartment is critical for the antitumor immune response

The immune system is an indispensable element for protection from neoplastic disease. It is comprised of two major interdependent cellular compartments, lymphoid and myeloid. While the lymphoid arm plays a key role in cancer cell destruction, the myeloid arm is essential to fully activate the lymphoid arm. Ordinarily, the myeloid arm, which consists of monocytes, macrophages, neutrophils and dendritic cells (DC), plays essential roles in host defense against pathogens, including cancer, through a variety of innate and adaptive immune functions. However, in the cancer setting, the normal process of myeloid cell production or differentiation is profoundly compromised, resulting in the accumulation of defective myeloid populations. Myeloid deficiencies can occur at developmental and/or functional levels in essentially all myeloid lineages. To distinguish ‘normal’ myeloid cells from their dysfunctional counterparts, the latter populations have been variously renamed MDSCs, tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), tumor-associated neutrophils (TANs), immature DCs or tolerogenic DCs. These classifications are largely based on surface marker expression and assays (in vitro and/or in vivo) that measure how they affect immune activation or tumor growth.

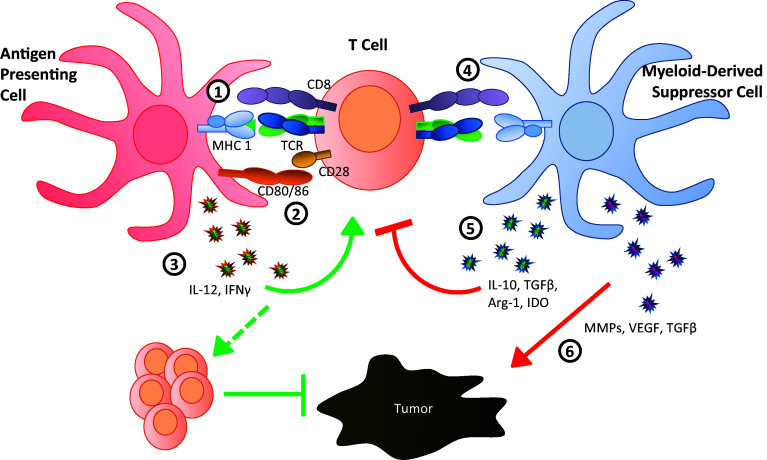

Alterations in the myeloid compartment drive the neoplastic process through three major mechanisms [4, 5]; two are immune system-dependent, and the third is immune system-independent (Fig. 1). First, in the cancer setting, myeloid cells fail to display normal features of myeloid differentiation [5]. Thus, they lack the ability to behave as professional antigen-presenting cells (APCs) for the activation and maintenance of tumor-specific T cell responses. Through a number of mechanisms, these APCs are unable to supply the three fundamental requirements for T cell recognition/activation; that is, they fail to provide adequate levels of: (1) major histocompatibility complex (MHC)/antigen expression, (2) co-stimulation or (3) pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin (IL)-12. Secondly, such myeloid populations not only impair T cell activation in a passive manner, but also in an active manner through the production of factors such as IL-10, arginase-1, indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) or transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) [6]. Thus, in the event that T cell activation does occur, these factors actively suppress the intensity and potency of the resultant T cell response. Additionally, several factors produced by MDSCs such as IL-10 and IL-6 have been shown to drive the production of T regulatory (Treg) cells [3]. Expansion of Treg cells, in turn, can suppress effector T cells within the tumor microenvironment. Thirdly, such myeloid populations can produce a variety of chronic inflammatory mediators, such as matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) and/or TGF-β, which directly nurture primary tumor growth or progression to metastasis [4]. It is for this latter reason that tumors are often characterized as ‘wounds that do not heal’ [7]. While such stromal repair mechanisms are appropriate for recovery from tissue damage following acute inflammation, this same host defense response is counter-productive in the context of neoplasia because it actually fuels the neoplastic process. Altogether, myeloid dysfunction can promote tumor progression through immune suppression, tissue remodeling, angiogenesis or combinations of these mechanisms.

Fig. 1.

Myeloid cells bridge pro-tumor and antitumor immune responses. In a mature, activated state myeloid cells can serve as effective antigen-presenting cells (left, red) to stimulate naïve T cells (center, orange) through the provision of antigen on MHC (1) concurrent with co-stimulation via CD80/CD86 (2) as well as production of inflammatory cytokines IL-12 and IFNγ (3). The convergence of these three signals activates the T cell which undergoes clonal expansion and trafficking to the site of pathogenesis (tumor), where T cells are capable of suppressing tumor growth through induction of apoptosis. Alternately, myeloid cells in an immature or aberrant state of activation behave as myeloid-derived suppressor cells (right, blue) and are unable to effectively stimulate naïve T cells (4) due to reduced antigen processing/presentation or down-regulated co-stimulatory molecules. Additionally, these cells produce cytokines such as IL-10 and TGFβ, as well as other molecules such as Arg-1 and IDO, that directly suppress T cell function and inhibit proliferation (5). These factors can also drive the expansion of T regulatory cells, further contributing to effector T cell suppression. Finally, independent of immune-based effects, MDSC have also been shown to directly promote tumor growth through production of MMPs, VEGF and TGFβ (6)

Atypical expansion of myeloid cells is associated with human neoplasia

Evidence for atypical myelopoiesis, characterized by the elevation of one or more myeloid subsets in the bone marrow or periphery (blood or spleen), has been documented in patients reflecting a range of tumor types. Prior to the widespread use of flow cytometry, atypical myelopoiesis was most readily identified as leukocytosis or monocytosis (affecting neutrophils and/or monocytes) by complete blood count [8–15]. The advent of multi-color flow cytometry has allowed for a more comprehensive analysis and identification of specific cellular subsets/phenotypes. Using phenotypic panels shown in Table 1, increased frequencies of at least one ‘immature’ or ‘suppressive’ myeloid subset in the peripheral blood have been identified in patients with melanoma [16–22], sarcoma [21, 23, 24], head and neck cancer [21, 25–28], brain tumors [22, 24, 29], thyroid cancer [30], lung cancer [21, 25, 26, 31–38], breast cancer [21, 25, 30, 31, 39–41], cervical and ovarian cancer [24, 31], renal cell carcinoma [22, 24, 42–45], prostate cancer [46, 47], hepatocellular carcinoma [31, 48–50] and gastrointestinal cancers [20–22, 26, 30, 31, 46, 50–55] (including esophagus, stomach, pancreas, bladder/urinary tract and colorectal cancer) compared to healthy controls or patients with other non-malignant disorders. Atypical myelopoiesis has also been described in hematologic malignancies, including multiple myeloma [56], chronic lymphocytic leukemia [24], mantle cell lymphoma [57], B cell lymphoma [24], and acute myeloid leukemia (AML) or chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) [58, 59]. Undoubtedly, AML or CML are the most extreme examples of deregulated myelopoiesis as these represent neoplastic malignancies of the myeloid compartment.

Table 1.

Subsets identified as dysregulated in human cancers

| Cell name | Clinical markers | Associated tumor |

|---|---|---|

| ‘MDSC’ | CD11b+HLA-DRlow/−CD14+ [18, 65] | Melanoma |

| HLA-DRlow/−CD14+ [19, 28, 38] | Melanoma, squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck | |

| Lin−CD11b+HLA-DR−CD33+ [21] | Multiple solid tumor types | |

| HLA-DR−CD33+CD14+/−CD15+/− [22] | Glioblastoma | |

| CD66b+CD125−HLA-DR−CD33+CD11b+/−CD16+/− [26] | Multiple solid tumor types | |

| CD11b+HLA-DRlow/−CD33+CD14+CD34+ [27] | Squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck | |

| CD11b+CD33+CD14− [30, 33, 50, 59] | Multiple solid tumor types, chronic myeloid leukemia, renal cell carcinoma | |

| CD11b+CD33+CD14+CD15low/−IL-4Rα+S100A9+ [34] | Non-small cell lung cancer | |

| CD11b+CD33+CD14−CD15+IL-4R+IFNγR+ [36] | Non-small cell lung cancer | |

| CD11b+CD33+CD15+ [37] | Non-small cell lung cancer | |

| CD33+HLA-DR− [39] | Breast cancer | |

| CD45+CD13+CD33+CD14−CD15− [40] | Breast cancer | |

| CD11b+HLA-DR−CD33+ [43] | Renal cell carcinoma | |

| Lin−CD11b+HLA-DR−CD33+ CD18+CD31+ClassI+CD1a+CD10+ [44] | Renal cell carcinoma | |

| Six subsets: 1: CD14+IL-4Rα+, 2: CD15+IL-4Rα+, 3: Lin−HLA-DR−CD33+, 4: CD14+HLA-DR− /lo, 5: CD11b+CD14−CD15+ and 6: CD15+FSCloSSChi [45] | Renal cell carcinoma | |

| HLA-DRlow/−CD14+ [46, 48] | Hepatocellular carcinoma | |

| Linlow/−HLA-DR−CD33+ [49, 64] | Renal cell carcinoma, melanoma, hepatocellular carcinoma | |

| CD11b+HLA-DR−CD33+CD14− [51] | Esophageal cancer | |

| SSChighLin−CD11b+HLA-DRlowCD14−CD15+CD33+ [52] | Gastric cancer | |

| Lin−/lowCD11b+HLA-DR−CD14−CD15−CD33+CD13+CD39+CD66b− [55] | Colorectal cancer | |

| CD11b+CD14−CD15+ [63] | Uveal melanoma | |

| Monocytic MDSC | CD11b+HLA-DRlowCD33+CD14+ [16] | Melanoma |

| Lin−HLA-DR−CD14+ [17] | Melanoma | |

| CD14+IL-4Rα+ [20] | Colon carcinoma | |

| CD11b+HLA-DR−CD33+CD14+CD15+ [35] | Non-small cell lung cancer | |

| CD11b+HLA-DR−CD33+CD14+CD124+ [41] | Breast cancer | |

| HLA-DR−CD33+CD14+ [42] | Clear cell renal cancer | |

| HLA-DRlow/−CD14+ [46] | Prostate cancer | |

| Lin−CD11b+HLA-DRlow/−CD33+CD14+ [47] | Prostate cancer | |

| Lin-HLA-DR−CD14+ [53] | Pancreatic cancer | |

| CD11b+HLA-DR-CD33+CD14+ [58] | Chronic myeloid leukemia | |

| PMN-MDSC | CD11b+HLA-DR−CD33+CD14−CD15+ [35] | Non-small cell lung cancer |

| Lin−CD11b+HLA-DRlow/−CD33+CD15+ [47] | Prostate cancer | |

| Granulocytic MDSC | CD11b+CD14−CD15+CD66b+CD124+ [41] | Breast cancer |

| Lin−CD11b+HLA-DR−CD33+CD15+ [53] | Pancreatic cancer | |

| CD11b+HLA-DR−CD33+CD14− [58] | Chronic myeloid leukemia | |

| Neutrophils | CD11b+HLA-DR−CD33loCD14−CD15+CD66b+ [29] | Glioblastoma |

| Suppressive fibrocytes | CD11b+HLA-DR+CD14−CD15+CD66b+CD123−CD11chiCD127+ [23] | Pediatric sarcoma |

| Monocyte precursors | HLA-DR−CD14+ [24] | Multiple solid and hematopoietic tumor types |

| Immature myeloid cells | Lin-HLA-DR−CD13+/−CD14−CD11c+/− [25] | Multiple solid tumor types |

| Lin-CD33intCD34+CD133+CD15+ [31] | Multiple solid tumor types | |

| CD11b+CD33+CD79a+ [32] | Lung cancer |

The fact that deregulated myelopoiesis is such a common occurrence in neoplasia has led to the notion that such myeloid alterations may have prognostic value [6]. While this notion is appealing, it is complicated by the extreme cellular heterogeneity of the myeloid response and the lack of a uniform definition for the ‘cells of interest.’ This is particularly true in the case of ‘MDSCs’ (Table 1); at minimum, however, these cells are thought to be cluster of differentiation (CD)11b+ human leukocyte antigen-DR (HLA-DR)low/− and broadly characterized morphologically as granulocytic-like and monocytic-like cells reflecting a range of differentiation patterns. Indeed, reduced expression of MHC class II molecules, such as HLA-DR, is likely to impair the ability of these cells to present antigenic determinants for effective CD4+ T cell activation. The diversity of phenotypes identified in the literature is due at least in part to the notion that particular subsets may be expanded in a tumor-dependent manner [60]. Importantly, phenotypic analyses of MDSC subsets in cancer patients have been supported by histochemical and morphological methodologies using cytospin samples [23, 33, 34, 36, 40, 44] or colony or tube forming growth assays [25, 55, 61].

Expanded myeloid subsets in cancer patients display immunosuppressive functions

While we have characterized circulating ‘MDSCs’ as a telling characteristic of tumor-induced perturbations in myelopoiesis, it is important to note that numerous studies have described the infiltration of these as well as other myeloid populations in the tumor microenvironment [11, 13, 20, 27–29, 31, 40, 51, 53, 55, 61, 62], implicating a key role for these expanded populations in driving pro-tumor behavior locally.

Ostensibly, several studies have attempted to link MDSC frequency with function, primarily by ex vivo co-culture of these cells with autologous T cells. ‘MDSCs’ isolated from cancer patients fail to stimulate autologous T cells [23, 25, 48] and, as their name suggests, can directly suppress T cell proliferation [18–20, 22, 26–29, 34, 37, 38, 40, 44, 47, 48, 52, 55, 58] as well as production of effector cytokines IL-2 [21], IL-12 [51], and interferon (IFN)-γ [19, 21, 22, 25, 26, 28, 29, 33, 34, 38, 40, 44, 48, 52]. These cells are associated with higher expression or production of immunosuppressive molecules such as programmed death-ligand l (PD-L1) [28, 59], IL-4 receptor [34, 51], IL-10 [34, 40], reactive oxygen species [27, 38, 44], IDO [40, 55], arginase-1 [19, 22, 27, 29, 34–36, 48, 51–53, 55, 58, 59], TGF-β [18, 28, 40], tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α [34, 44], granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF) [22, 44] and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) [19, 23, 34, 36, 44, 47, 52]. When phenotypically similar cells are isolated from healthy donors, they fail to demonstrate these suppressive functions [60]. These functions have been strongly related to MDSC biology observed in mouse models [6, 39] as well as those induced from human cells in culture systems [31]. Thus, while the phenotypic definition of MDSCs remains complex, it is not surprising that elevated frequencies of myeloid cells negatively correlate with tumor stage [16, 19, 21, 27, 31, 40, 49, 51, 52], metastatic burden [21, 38, 40, 51, 55, 63], response to therapy [14, 21, 33, 34, 36, 38, 43, 64] and progression-free or overall survival [10, 11, 13–15, 31, 34, 38, 39, 45, 47, 52, 57, 65]. These observations justify future work to better understand how this atypical myeloid phenomenon can be utilized either singly or in combination with other clinical features to improve diagnostic or prognostic merit.

An authentic biomarker should be able to predict changes in disease status before overt clinical changes in pathology. Prospective studies on the early changes in myeloid phenotypes or populations in patients at high risk of tumor development remain to be reported. However, melanoma patients in early stage disease (i.e., stage I/II) already show significant alterations in their myeloid compartment compared to ‘healthy volunteers’ [16]. Interestingly, in addition to neoplastic disease, MDSCs can be induced and expanded under diverse inflammatory or pathologic conditions [66]. Thus, these data suggest that alterations in the frequencies of MDSCs and/or their function may have prognostic implications under a broader array of diseases or disorders. Combining myeloid cell analysis with conventional cancer screening could clarify the role of myeloid aberrations as contributing factors for disease progression and their utility for predicting changes in disease status. It is noteworthy that myeloid cells, particularly MDSCs, increase with age [51, 67], which we posit contributes to the rise in cancer incidence with age.

We believe that a better understanding of the molecular events that cause such alterations in myeloid biology will identify novel prognostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets to improve responses during immune surveillance and cancer immunotherapy. This paradigm is built on the rationale that ‘myeloid health’ impacts the antitumor immune response, and instrumental to ‘myeloid health’ are appropriate developmental and maturational cues which are subverted during tumor development.

‘Myeloid health’ begins in the bone marrow

Currently, the principal method for assessing the myeloid response in cancer patients relies on analysis of peripheral blood and more rarely on tumor biopsies (Table 2). However, more meaningful and potentially earlier changes may be better detected in the bone marrow, the likely origin of these MDSC populations. To the best of our knowledge, only one study assessed atypical myelopoiesis in the bone marrow of solid tumor patients; a case study of a G-CSF-secreting sarcoma that resulted in such a burst in myeloproliferation for which a bone marrow biopsy was taken to rule out a myeloid leukemia [9].

Table 2.

Tissues assessed for changes in myeloid populations from patients with solid tumors

Myelopoiesis is a tightly controlled process by which myeloid cells develop from multipotent hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) in the bone marrow [68–71]. HSCs constitute an extremely rare population which undergoes a series of sequential steps of differentiation to give rise to more committed progenitors. These include multipotent progenitors (MPPs), common myeloid progenitors (CMPs) and granulocyte–monocyte progenitors (GMPs) which can be distinguished based on surface marker expression, responsiveness to particular cytokines and their ability to further differentiate along restricted lineages [31, 72, 73]. Ultimately, these progenitors give rise to immature myeloid cells which can undergo further differentiation into mature granulocytes, monocytes/macrophages and DCs within the bone marrow or following egress to the periphery. It is important to note that certain DC subsets have unique developmental programs and can be derived from lymphoid progenitors [3, 71].

The maintenance of HSCs within the bone marrow and developmental decisions to undergo myelopoiesis are governed by both cell-intrinsic and cell-extrinsic signals. The ability to respond to such signals is genetically regulated by a series of transcription factors, namely PU box binding transcription factor PU.1, CCAAT/enhancer binding protein-α (C/EBPα) and interferon regulatory factor-8 (IRF-8) which generally act in concert to oversee myeloid cell fate [68, 70]. While the bone marrow was once thought to be a ‘protected’ compartment, it is now clear that HSCs and their progeny can sense and respond to a number of signals emanating from the periphery [72, 73]. Thus, transcription factors instrumental for normal myeloid cell development, differentiation and function can be targets of TDFs. In turn, such TDFs may impair the expression of such ‘master’ regulators, which ultimately affect the fate of the resulting myeloid response.

IRF-8 as a key regulator of myeloid ‘health’ and a target of TDFs

Certain transcription factors have achieved designation as ‘master’ regulators for their ability to direct key cellular programs integral to cellular identity, such as the distinct expression patterns in T helper subsets (Th) of T box transcription factor T-bet in CD4+ Th1 T cells, GATA-binding protein 3 (GATA-3) in Th2 T cells and RAR-related orphan receptor γt (RORγt) in CD4+ Th17 cells [74]. A number of transcription factors have been implicated in regulating myeloid biology [68]; however, we and others argue for IRF-8 as a myeloid ‘master’ regulator.

IRF-8 is now well regarded as an indispensable transcription factor for lineage commitment of GMPs to either monocytes/macrophages or granulocytes. Elegant studies in IRF-8−/− mice reveal that IRF-8 deficiency causes profound myeloid defects, notably those affecting macrophage, granulocytic and DC development/differentiation [75–82]. Such IRF-8−/− mice also show a substantial reduction in the number of mature macrophages [79], with the remaining macrophages being functionally impaired [83, 84]. The importance of IRF-8 in myeloid development and function is not limited to mouse models; IRF-8 is also indispensable for human monocyte and DC development [85]. A point mutation in the DNA binding domain (K108E) results in decreased numbers of circulating monocytes and DCs, while another point mutation (T80A) results in a selective reduction in circulating CD11c+ CD1c+ DCs.

IRF-8 is not only critical in myeloid biology at a developmental level, but also a functional level. In fact, a number of genes essential to normal myeloid function are IRF-8-dependent and include those required for pathogen clearance such as lysozyme M, cystatin C, cathepsin C and RNase L [86, 87], as well as the production of chemokines/cytokines necessary for effective stimulation of Th1 responses such as IL-12, IFN-γ [75, 81, 88, 89], IL-18 and RANTES (CCL5) [83, 90, 91]. Additionally, IRF-8-deficient myeloid cells have defects in the expression of components important for antigen processing and presentation, such as the transporters associated with antigen processing (TAP)-1 or TAP-2 [78, 92, 93]. Finally, IRF-8 is intimately involved in connecting a number of innate signaling pathways, including those downstream of IFN-γ, toll-like receptors (TLRs), IL-12 and type I IFNs [76, 83, 94–99]. Thus, loss of IRF-8 generates an overabundance of immature and/or defective myeloid cells, which lack the characteristics critical for generating effective adaptive immune responses.

Interestingly, the myeloproliferative phenotype observed in IRF-8−/− mice bears a striking similarity to the myeloid phenotypes observed in cancer models. IRF-8−/− myeloid cells show a high degree of genetic overlap with MDSCs isolated from tumor-bearing mice [39]. We have also observed in breast cancer patients that IRF-8 expression inversely correlates with MDSC frequency, suggesting that suppression of IRF-8 during the neoplastic process may underlie MDSC expansion in at least certain patients with solid cancers [39]. Moreover, cancer patients harbor defective DC subsets [5, 25], which may be another potential negative consequence of IRF-8 downregulation. IRF-8 is also greatly decreased in patients with CML and correlates with disease progression [100]. Thus, we posit that IRF-8 is downregulated during neoplasia and may serve as a functionally relevant and reliable indicator of the health of the myeloid arm. Of note, in addition to the loss of IRF-8 expression, other transcription factors, such as C/EBPβ has been reported to positively influence the accumulation of MDSCs in tumor-bearing mice [101]. A potential regulatory interaction between IRF-8 and C/EBPβ as well as with other modulators of MDSC biology (e.g., S100A8/9, CHOP, HMGB1 and osteopontin), however, remains to be investigated [102].

TDFs act at all stages of myeloid development to co-opt this arm of the immune response to the benefit of the tumor [3, 4]. TDFs such as HMGB1 and S100A8/9 within the tumor microenvironment have been implicated in direct suppression of myeloid function and/or maintenance of myeloid cells in an immature state. Additionally, certain TDFs, such as IL-6, VEGF, G-CSF or granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), have the potential to act at a systemic level and are often elevated in the sera of patients and tumor-bearing mouse models [5]. Many of these TDFs have been shown to activate the transcription factors, signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT)-3 and/or STAT5, to impair myeloid cell differentiation and drive their expansion [3]. Indeed, high levels of STAT3 activation within MDSC subsets from solid cancer patients have been identified [19, 27, 40, 103]. Moreover, we have recently demonstrated that IRF-8 expression can be directly regulated by the activation of these STATs, and the loss of IRF-8 leads to subsequent MDSC accumulation [39]. We hypothesize that the cellular source of myeloid expansion likely originates within the bone marrow compartment due to the important role IRF-8 plays in maintaining myeloid balance at the GMP stage of development (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Tumor induction of aberrant myelopoiesis occurs among progenitor cells within the bone marrow. Myelopoiesis proceeds through stepwise differentiation in the bone marrow (purple shaded cells). At the GMP stage, the transcription factor IRF-8 serves as a key regulator of development, controlling both the quantity and character of the myeloid output, such that high expression of IRF-8 favors the monocytic lineage (red cell) and overall reduced myeloid numbers. Tumors secrete a variety of factors such as G-CSF that act in a systemic way to reduce IRF-8 within progenitor cells, releasing myelopoiesis from IRF-8 control such that the granulocytic lineage (blue cell) undergoes hyperplasia, leading to increased immature suppressive cells to promote tumor growth

Therapies to target myeloid defects in cancer

Given the importance of MDSCs and other atypical myeloid responses in cancer, it is not surprising that considerable interest has been devoted to strategies aimed at eliminating them or abrogating their pro-tumor activities. ‘Conventional’ therapies have shown transient decreases in myeloid cell populations following treatment, including surgical resection [46] or radiotherapy [104], but this may not be consistent across tumor types [42, 46]. Some studies have assessed myeloid cells following conventional chemotherapy [105]. Generally, low-dose chemotherapy appears to enhance DC function and stimulate protective immune responses. However, MDSC numbers and/or function have been assessed in few chemotherapy clinical trials and have shown mixed results. For example, in two trials of breast cancer patients treated with cyclophosphamide in conjunction with other chemotherapeutics, one trial witnessed a decrease in MDSCs [41], while another showed an increase in MDSCs [21]. Myeloid responses following common ‘first-line’ therapies deserve better assessment, as treatment related disturbance of the myeloid compartment may be associated with cancer recurrence or development of secondary hematologic malignancies.

Interventions that target atypical myelopoiesis or the functional consequences of atypical myelopoiesis are currently under development in preclinical or clinical trials. This includes technologies to reduce myeloid cell trafficking to the tumor site through inhibition of the colony-stimulating factor (CSF)-1 receptor signaling pathway or blockade of CCL2/CCR2, CXCL2/CXCR2, CXCL12/CXCR4 interactions, blockade of myeloid suppressive mechanisms such as cyclooxygenase (COX)-2, amino-bisphosphonates or phosphodiesterase (PDE)-5 inhibitors, as well as nonspecific signaling inhibitors to abrogate proliferation such as tyrosine kinase or peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR)-γ inhibitors [6]. Additionally, drugs known to activate toll-like receptors (TLRs), such as CpG, decrease MDSCs in preclinical tumor models [106]. Various other cytotoxic drugs are also being tested for their ability to suppress myeloproliferation, but these remain relatively nonspecific.

In mouse models, depletion of MDSCs has been generally accomplished by the use of antibodies that target the surface markers Gr-1 or Ly6G [107]. However, since these markers are not MDSC-specific, normal myeloid populations such as monocytes, granulocytes or DCs can be negatively impacted. Nonetheless, for ‘proof-of-concept,’ this strategy has helped to strengthen the causal relationship between MDSC numbers and suppression of antitumor responses. More recently, a novel MDSC-peptide binding approach, termed ‘peptibodies,’ has been developed that appears to more preferentially target and deplete MDSCs compared to anti-Gr-1 antibody administration [108]. Importantly, MDSC depletion was accompanied by significant antitumor effects. These new findings reinforce the concept that depleting MDSCs has great therapeutic promise.

Perhaps the most specific and functionally relevant therapies proposed to target myeloid defects would be development of neutralizing antibodies for the cytokine drivers of aberrant myelopoiesis, G-CSF and GM-CSF. Although neutralizing antibodies for G-CSF [109, 110] and GM-CSF [111] have shown promise in mouse models, these reagents have yet to be developed for use in cancer clinical trials [6]. We have shown a strong functional association between G-CSF production and development of suppressive MDSC-like cells in mice, even in the absence of tumor [110], primarily through the suppression of IRF-8 [39]. Antithetically, a number of therapeutic regimens include exogenous administration of G-CSF or GM-CSF following or concurrent with chemotherapy [112, 113]. These cytokines are often included to reduce therapy-associated neutropenia and susceptibility to infection, though they have also been used as adjuvants alone or in combination with immunotherapeutic vaccines. There is some evidence of benefit using these strategies, but these studies largely lack characterization of the myeloid response before and after therapy [113].

An alternative, mechanistically justified, approach to reducing aberrant myelopoiesis would be therapies that enhance IRF-8 expression, either by activating transcription factors which subsequently induce IRF-8 such as STAT-1 [94] or by paired box protein PAX-5 [114] or direct targeting of IRF-8. We have seen that the level of IRF-8 in myeloid cells correlates strongly with response to immunotherapy [39]. One promising therapeutic appears to be all-trans retinoic acid (ATRA). In vitro experiments with ATRA have demonstrated this drug increases the expression of IRF-8 and is dependent on the phosphorylation of STAT-1 [115]. ATRA abrogated MDSC-mediated immunosuppression and directed differentiation of myeloid cells toward functional APCs [44]. A clinical trial of ATRA in lung cancer showed significant decreases in MDSCs which improved immune response to DC-based vaccination [116]. Success of this therapy highlights the potential for other drugs capable of stimulating IRF-8, and screening drugs based on their ability to activate transcription factors such as IRF-8 may be an effective drug development strategy.

Therapeutics that can correct myeloid defects could be an important tool in advancing cancer therapies. Indeed, recent advances in cancer immunotherapy were hailed as the biomedical breakthrough of 2013 [117], reflecting the development and use of novel strategies to drive activation of T cell responses, such as DC-based vaccines or immune checkpoint inhibitors. Despite great promise in animal models, clinical trials and clinical use of DC vaccines have yielded mixed results [118]. For example, a recent report highlights the difficulty in generating DC-based vaccines from patients with preexisting suppressive myeloid cells [24]. Such cells are resistant or refractory to standard activation protocols that were often developed with cells from healthy donors.

Another approach to immunotherapy, ‘checkpoint inhibitors’ or antibodies designed to block signaling molecules that downregulate T cell activation, has garnered impressive results in clinical trials and now in clinical practice in some but not all patients. Undoubtedly, the mechanistic basis for this differential therapeutic outcome is likely to be complex, but may be related at least in part to defects in the myeloid response. Consistent with this notion, some studies have assessed changes in myeloid responses following checkpoint inhibitor therapy of solid tumors. In melanoma patients, blockade of cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated protein-4 (CTLA-4) by ipilumimab resulted in reductions in the frequencies of suppressive myeloid populations [17] but changes in MDSC did not appear to be significant in prostate cancer [119]. Another CTLA-4 blocking antibody (tremelumimab) in combination with IFN-α resulted in a significant reduction in myeloid populations in metastatic melanoma patients [120]. PD-L1 is also a target for checkpoint blockade. Although there is clinical evidence of increased PD-L1 on suppressive myeloid populations [28, 59], no clinical trials have yet looked at changes in myeloid cells following PD-L1 blockade. Future directions are likely to continue to focus on combination therapies which ‘suppress the suppressors’ in order to optimally ‘activate the activators.’

Conclusions

It is very clear that atypical myelopoiesis is evident in patients with various cancer types, including those of non-hematopoietic and hematopoietic origins. While elevations in cell numbers are one thing, it is important to note that functional studies when performed have validated their pro-tumor behavior. Thus, changes in circulating myeloid cell frequencies may represent novel prognostic markers for patient outcomes. However, whether such changes can be detected very early on, particularly when MDSC are at low frequencies, during the course of disease or disease relapse remains unknown, meriting additional research to confirm MDSC as bona fide biomarkers, and to clarify potential limits of their use in neoplasia as well as other inflammatory or pathologic conditions. Moreover, since such developmental defects are likely initiated in bone marrow progenitors, it is tempting to speculate that the bone marrow may actually be the most reliable site for prognostic intent. However, additional evidence on the strength of changes in progenitor populations is needed to justify adoption of this more invasive testing site for patients with solid cancers. Nonetheless, advances in our fundamental understanding of the molecular bases for tumor-induced atypical myelopoiesis will likely lead to the identification of new therapeutic paradigms for clinical cancer care.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Institute of Health Grant R01CA140622 (to Scott I. Abrams), an Alliance Development Award from the Roswell Park Alliance Foundation (to Scott I. Abrams), Department of Defense Award W81XWH-11-1-0394 (to Scott I. Abrams) and National Institute of Health Training Grant T32CA085183 (to Colleen S. Netherby).

Conflict of interest

Authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Abbreviations

- AML

Acute myeloid leukemia

- APC

Antigen-presenting cell

- ATRA

All-trans retinoic acid

- CD

Cluster of differentiation

- C/EBPα

CCAAT/enhancer binding protein α

- CML

Chronic myeloid leukemia

- CMP

Common myeloid progenitors

- COX

Cyclooxygenase

- CTLA-4

Cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated protein 4

- DC

Dendritic cell

- GATA-3

GATA-binding protein 3

- G-CSF

Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor

- GMP

Granulocyte–monocyte progenitors

- GM-CSF

Granulocyte–macrophage colony-stimulating factor

- HLA-DR

Human leukocyte antigen-DR

- HSC

Hematopoietic stem cell

- IDO

Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase

- IFN

Interferon

- IL

Interleukin

- iNOS

Inducible nitric oxide synthase

- IRF-8

Interferon regulatory factor 8

- MDSC

Myeloid-derived suppressor cells

- MHC

Major histocompatibility complex

- MMP

Matrix metalloproteinase

- MPP

Multi-potent progenitor

- PAX5

Paired box protein Pax-5

- PDE

Phosphodiesterase

- PD-L1

Programmed death-ligand 1

- PPARγ

Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ

- PU.1

PU box binding transcription factor PU.1

- RANTES

Regulated on activation, normal T cell expressed and secreted

- RORγt

RAR-related orphan receptor γ t

- STAT

Signal transducer and activator of transcription

- TAM

Tumor-associated macrophage

- TAN

Tumor-associated neutrophil

- TAP

Transporter associated with antigen processing

- T-bet

T box transcription factor

- TDF

Tumor-derived factor

- TGF-β

Transforming growth factor-β

- Th

T helper subset

- TLRs

Toll-like receptors

- TNFα

Tumor necrosis factor α

- Tregs

T regulatory cells

- VEGF

Vascular endothelial growth factor

References

- 1.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144(5):646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. The hallmarks of cancer. Cell. 2000;100(1):57–70. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81683-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gabrilovich DI, Ostrand-Rosenberg S, Bronte V. Coordinated regulation of myeloid cells by tumours. Nat Rev Immunol. 2012;12(4):253–268. doi: 10.1038/nri3175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ostrand-Rosenberg S, Sinha P, Beury DW, Clements VK. Cross-talk between myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSC), macrophages, and dendritic cells enhances tumor-induced immune suppression. Semin Cancer Biol. 2012;22(4):275–281. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2012.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gabrilovich D. Mechanisms and functional significance of tumour-induced dendritic-cell defects. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4(12):941–952. doi: 10.1038/nri1498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Talmadge JE, Gabrilovich DI. History of myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013;13(10):739–752. doi: 10.1038/nrc3581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schafer M, Werner S. Cancer as an overhealing wound: an old hypothesis revisited. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9(8):628–638. doi: 10.1038/nrm2455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shoenfeld Y, Tal A, Berliner S, Pinkhas J. Leukocytosis in non hematological malignancies–a possible tumor-associated marker. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 1986;111(1):54–58. doi: 10.1007/BF00402777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dorn C, Bugl S, Malenke E, Muller MR, Weisel KC, Vogel U, Horger M, Kanz L, Kopp HG. Paraneoplastic granulocyte colony-stimulating factor secretion in soft tissue sarcoma mimicking myeloproliferative neoplasia: a case report. BMC Res Notes. 2014;7:313. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-7-313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schmidt H, Bastholt L, Geertsen P, Christensen IJ, Larsen S, Gehl J, von der Maase H. Elevated neutrophil and monocyte counts in peripheral blood are associated with poor survival in patients with metastatic melanoma: a prognostic model. Br J Cancer. 2005;93(3):273–278. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Donskov F, von der Maase H. Impact of immune parameters on long-term survival in metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24(13):1997–2005. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.03.9594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Paesmans M, Sculier JP, Lecomte J, Thiriaux J, Libert P, Sergysels R, Bureau G, Dabouis G, Van Cutsem O, Mommen P, Ninane V, Klastersky J. Prognostic factors for patients with small cell lung carcinoma: analysis of a series of 763 patients included in 4 consecutive prospective trials with a minimum follow-up of 5 years. Cancer. 2000;89(3):523–533. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20000801)89:3<523::aid-cncr7>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carus A, Ladekarl M, Hager H, Pilegaard H, Nielsen PS, Donskov F. Tumor-associated neutrophils and macrophages in non-small cell lung cancer: no immediate impact on patient outcome. Lung Cancer. 2013;81(1):130–137. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2013.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee Y, Kim SH, Han JY, Kim HT, Yun T, Lee JS. Early neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio reduction as a surrogate marker of prognosis in never smokers with advanced lung adenocarcinoma receiving gefitinib or standard chemotherapy as first-line therapy. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2012;138(12):2009–2016. doi: 10.1007/s00432-012-1281-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen MH, Chang PM, Chen PM, Tzeng CH, Chu PY, Chang SY, Yang MH. Prognostic significance of a pretreatment hematologic profile in patients with head and neck cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2009;135(12):1783–1790. doi: 10.1007/s00432-009-0625-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rudolph BM, Loquai C, Gerwe A, Bacher N, Steinbrink K, Grabbe S, Tuettenberg A. Increased frequencies of CD11b(+) CD33(+) CD14(+) HLA-DR(low) myeloid-derived suppressor cells are an early event in melanoma patients. Exp Dermatol. 2014;23(3):202–204. doi: 10.1111/exd.12336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meyer C, Cagnon L, Costa-Nunes CM, Baumgaertner P, Montandon N, Leyvraz L, Michielin O, Romano E, Speiser DE. Frequencies of circulating MDSC correlate with clinical outcome of melanoma patients treated with ipilimumab. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2014;63(3):247–257. doi: 10.1007/s00262-013-1508-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Filipazzi P, Valenti R, Huber V, Pilla L, Canese P, Iero M, Castelli C, Mariani L, Parmiani G, Rivoltini L. Identification of a new subset of myeloid suppressor cells in peripheral blood of melanoma patients with modulation by a granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulation factor-based antitumor vaccine. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(18):2546–2553. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.08.5829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Poschke I, Mougiakakos D, Hansson J, Masucci GV, Kiessling R. Immature immunosuppressive CD14+ HLA-DR−/low cells in melanoma patients are Stat3hi and overexpress CD80, CD83, and DC-sign. Cancer Res. 2010;70(11):4335–4345. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-3767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mandruzzato S, Solito S, Falisi E, Francescato S, Chiarion-Sileni V, Mocellin S, Zanon A, Rossi CR, Nitti D, Bronte V, Zanovello P. IL4Ralpha+ myeloid-derived suppressor cell expansion in cancer patients. J Immunol. 2009;182(10):6562–6568. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Diaz-Montero CM, Salem ML, Nishimura MI, Garrett-Mayer E, Cole DJ, Montero AJ. Increased circulating myeloid-derived suppressor cells correlate with clinical cancer stage, metastatic tumor burden, and doxorubicin-cyclophosphamide chemotherapy. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2009;58(1):49–59. doi: 10.1007/s00262-008-0523-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Raychaudhuri B, Rayman P, Ireland J, Ko J, Rini B, Borden EC, Garcia J, Vogelbaum MA, Finke J. Myeloid-derived suppressor cell accumulation and function in patients with newly diagnosed glioblastoma. Neuro Oncol. 2011;13(6):591–599. doi: 10.1093/neuonc/nor042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang H, Maric I, DiPrima MJ, Khan J, Orentas RJ, Kaplan RN, Mackall CL. Fibrocytes represent a novel MDSC subset circulating in patients with metastatic cancer. Blood. 2013;122(7):1105–1113. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-08-449413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Laborde RR, Lin Y, Gustafson MP, Bulur PA, Dietz AB. Cancer vaccines in the world of immune suppressive monocytes (CD14(+)HLA-DR(lo/neg) Cells): the gateway to improved responses. Front Immunol. 2014;5:147. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Almand B, Clark JI, Nikitina E, van Beynen J, English NR, Knight SC, Carbone DP, Gabrilovich DI. Increased production of immature myeloid cells in cancer patients: a mechanism of immunosuppression in cancer. J Immunol. 2001;166(1):678–689. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.1.678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brandau S, Trellakis S, Bruderek K, Schmaltz D, Steller G, Elian M, Suttmann H, Schenck M, Welling J, Zabel P, Lang S. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells in the peripheral blood of cancer patients contain a subset of immature neutrophils with impaired migratory properties. J Leukoc Biol. 2011;89(2):311–317. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0310162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vasquez-Dunddel D, Pan F, Zeng Q, Gorbounov M, Albesiano E, Fu J, Blosser RL, Tam AJ, Bruno T, Zhang H, Pardoll D, Kim Y. STAT3 regulates arginase-I in myeloid-derived suppressor cells from cancer patients. J Clin Invest. 2013;123(4):1580–1589. doi: 10.1172/JCI60083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chikamatsu K, Sakakura K, Toyoda M, Takahashi K, Yamamoto T, Masuyama K. Immunosuppressive activity of CD14+ HLA-DR− cells in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Cancer Sci. 2012;103(6):976–983. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2012.02248.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sippel TR, White J, Nag K, Tsvankin V, Klaassen M, Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK, Waziri A. Neutrophil degranulation and immunosuppression in patients with GBM: restoration of cellular immune function by targeting arginase I. Clin Cancer Res. 2011;17(22):6992–7002. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-1107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ohki S, Shibata M, Gonda K, Machida T, Shimura T, Nakamura I, Ohtake T, Koyama Y, Suzuki S, Ohto H, Takenoshita S. Circulating myeloid-derived suppressor cells are increased and correlate to immune suppression, inflammation and hypoproteinemia in patients with cancer. Oncol Rep. 2012;28(2):453–458. doi: 10.3892/or.2012.1812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu WC, Sun HW, Chen HT, Liang J, Yu XJ, Wu C, Wang Z, Zheng L. Circulating hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells are myeloid-biased in cancer patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(11):4221–4226. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1320753111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Luger D, Yang YA, Raviv A, Weinberg D, Banerjee S, Lee MJ, Trepel J, Yang L, Wakefield LM. Expression of the B-cell receptor component CD79a on immature myeloid cells contributes to their tumor promoting effects. PLoS One. 2013;8(10):e76115. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang S, Fu Y, Ma K, Liu C, Jiao X, Du W, Zhang H, Wu X. The significant increase and dynamic changes of the myeloid-derived suppressor cells percentage with chemotherapy in advanced NSCLC patients. Clin Transl Oncol. 2014;16(7):616–622. doi: 10.1007/s12094-013-1125-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Feng PH, Lee KY, Chang YL, Chan YF, Kuo LW, Lin TY, Chung FT, Kuo CS, Yu CT, Lin SM, Wang CH, Chou CL, Huang CD, Kuo HP. CD14(+)S100A9(+) monocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells and their clinical relevance in non-small cell lung cancer. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186(10):1025–1036. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201204-0636OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Heuvers ME, Muskens F, Bezemer K, Lambers M, Dingemans AM, Groen HJ, Smit EF, Hoogsteden HC, Hegmans JP, Aerts JG. Arginase-1 mRNA expression correlates with myeloid-derived suppressor cell levels in peripheral blood of NSCLC patients. Lung Cancer. 2013;81(3):468–474. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2013.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu CY, Wang YM, Wang CL, Feng PH, Ko HW, Liu YH, Wu YC, Chu Y, Chung FT, Kuo CH, Lee KY, Lin SM, Lin HC, Wang CH, Yu CT, Kuo HP. Population alterations of l-arginase- and inducible nitric oxide synthase-expressed CD11b+/CD14(−)/CD15+/CD33+ myeloid-derived suppressor cells and CD8+ T lymphocytes in patients with advanced-stage non-small cell lung cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2010;136(1):35–45. doi: 10.1007/s00432-009-0634-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Srivastava MK, Bosch JJ, Thompson JA, Ksander BR, Edelman MJ, Ostrand-Rosenberg S. Lung cancer patients’ CD4(+) T cells are activated in vitro by MHC II cell-based vaccines despite the presence of myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2008;57(10):1493–1504. doi: 10.1007/s00262-008-0490-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Huang A, Zhang B, Wang B, Zhang F, Fan KX, Guo YJ. Increased CD14(+)HLA-DR (−/low) myeloid-derived suppressor cells correlate with extrathoracic metastasis and poor response to chemotherapy in non-small cell lung cancer patients. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2013;62(9):1439–1451. doi: 10.1007/s00262-013-1450-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Waight JD, Netherby C, Hensen ML, Miller A, Hu Q, Liu S, Bogner PN, Farren MR, Lee KP, Liu K, Abrams SI. Myeloid-derived suppressor cell development is regulated by a STAT/IRF-8 axis. J Clin Invest. 2013;123(10):4464–4478. doi: 10.1172/JCI68189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yu J, Du W, Yan F, Wang Y, Li H, Cao S, Yu W, Shen C, Liu J, Ren X. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells suppress antitumor immune responses through IDO expression and correlate with lymph node metastasis in patients with breast cancer. J Immunol. 2013;190(7):3783–3797. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Verma C, Eremin JM, Robins A, Bennett AJ, Cowley GP, El-Sheemy MA, Jibril JA, Eremin O. Abnormal T regulatory cells (Tregs: FOXP3+, CTLA-4+), myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs: monocytic, granulocytic) and polarised T helper cell profiles (Th1, Th2, Th17) in women with large and locally advanced breast cancers undergoing neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) and surgery: failure of abolition of abnormal treg profile with treatment and correlation of treg levels with pathological response to NAC. J Transl Med. 2013;11:16. doi: 10.1186/1479-5876-11-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wald G, Barnes KT, Bing MT, Kresowik TP, Tomanek-Chalkley A, Kucaba TA, Griffith TS, Brown JA, Norian LA. Minimal changes in the systemic immune response after nephrectomy of localized renal masses. Urol Oncol. 2014;32(5):589–600. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2014.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang Z, Zhang Y, Liu Y, Wang L, Zhao L, Yang T, He C, Song Y, Gao Q. Association of myeloid-derived suppressor cells and efficacy of cytokine-induced killer cell immunotherapy in metastatic renal cell carcinoma patients. J Immunother. 2014;37(1):43–50. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0000000000000005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kusmartsev S, Su Z, Heiser A, Dannull J, Eruslanov E, Kubler H, Yancey D, Dahm P, Vieweg J. Reversal of myeloid cell-mediated immunosuppression in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(24):8270–8278. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Walter S, Weinschenk T, Stenzl A, Zdrojowy R, Pluzanska A, Szczylik C, Staehler M, Brugger W, Dietrich PY, Mendrzyk R, Hilf N, Schoor O, Fritsche J, Mahr A, Maurer D, Vass V, Trautwein C, Lewandrowski P, Flohr C, Pohla H, Stanczak JJ, Bronte V, Mandruzzato S, Biedermann T, Pawelec G, Derhovanessian E, Yamagishi H, Miki T, Hongo F, Takaha N, Hirakawa K, Tanaka H, Stevanovic S, Frisch J, Mayer-Mokler A, Kirner A, Rammensee HG, Reinhardt C, Singh-Jasuja H. Multipeptide immune response to cancer vaccine IMA901 after single-dose cyclophosphamide associates with longer patient survival. Nat Med. 2012;18(8):1254–1261. doi: 10.1038/nm.2883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brusa D, Simone M, Gontero P, Spadi R, Racca P, Micari J, Degiuli M, Carletto S, Tizzani A, Matera L. Circulating immunosuppressive cells of prostate cancer patients before and after radical prostatectomy: profile comparison. Int J Urol. 2013;20(10):971–978. doi: 10.1111/iju.12086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Idorn M, Kollgaard T, Kongsted P, Sengelov L, Thor Straten P. Correlation between frequencies of blood monocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells, regulatory T cells and negative prognostic markers in patients with castration-resistant metastatic prostate cancer. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2014;63(11):1177–1187. doi: 10.1007/s00262-014-1591-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hoechst B, Ormandy LA, Ballmaier M, Lehner F, Kruger C, Manns MP, Greten TF, Korangy F. A new population of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in hepatocellular carcinoma patients induces CD4(+)CD25(+)Foxp3(+) T cells. Gastroenterology. 2008;135(1):234–243. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shen P, Wang A, He M, Wang Q, Zheng S. Increased circulating Lin(-/low) CD33(+) HLA-DR(−) myeloid-derived suppressor cells in hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Hepatol Res. 2014;44(6):639–650. doi: 10.1111/hepr.12167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yazawa T, Shibata M, Gonda K, Machida T, Suzuki S, Kenjo A, Nakamura I, Tsuchiya T, Koyama Y, Sakurai K, Shimura T, Tomita R, Ohto H, Gotoh M, Takenoshita S. Increased IL-17 production correlates with immunosuppression involving myeloid-derived suppressor cells and nutritional impairment in patients with various gastrointestinal cancers. Mol Clin Oncol. 2013;1(4):675–679. doi: 10.3892/mco.2013.134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gao J, Wu Y, Su Z, Amoah Barnie P, Jiao Z, Bie Q, Lu L, Wang S, Xu H. Infiltration of alternatively activated macrophages in cancer tissue is associated with MDSC and Th2 polarization in patients with esophageal cancer. PLoS One. 2014;9(8):e104453. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0104453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang L, Chang EW, Wong SC, Ong SM, Chong DQ, Ling KL. Increased myeloid-derived suppressor cells in gastric cancer correlate with cancer stage and plasma S100A8/A9 proinflammatory proteins. J Immunol. 2013;190(2):794–804. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Khaled YS, Ammori BJ, Elkord E. Increased levels of granulocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells in peripheral blood and tumour tissue of pancreatic cancer patients. J Immunol Res. 2014;2014:879897. doi: 10.1155/2014/879897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bazhin AV, Shevchenko I, Umansky V, Werner J, Karakhanova S. Two immune faces of pancreatic adenocarcinoma: possible implication for immunotherapy. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2014;63(1):59–65. doi: 10.1007/s00262-013-1485-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zhang B, Wang Z, Wu L, Zhang M, Li W, Ding J, Zhu J, Wei H, Zhao K. Circulating and tumor-infiltrating myeloid-derived suppressor cells in patients with colorectal carcinoma. PLoS One. 2013;8(2):e57114. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Romano A, Conticello C, Cavalli M, Vetro C, La Fauci A, Parrinello NL, Di Raimondo F. Immunological dysregulation in multiple myeloma microenvironment. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:198539. doi: 10.1155/2014/198539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.von Hohenstaufen KA, Conconi A, de Campos CP, Franceschetti S, Bertoni F, Margiotta Casaluci G, Stathis A, Ghielmini M, Stussi G, Cavalli F, Gaidano G, Zucca E. Prognostic impact of monocyte count at presentation in mantle cell lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 2013;162(4):465–473. doi: 10.1111/bjh.12409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Giallongo C, Parrinello N, Tibullo D, La Cava P, Romano A, Chiarenza A, Barbagallo I, Palumbo GA, Stagno F, Vigneri P, Di Raimondo F. Myeloid derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) are increased and exert immunosuppressive activity together with polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs) in chronic myeloid leukemia patients. PLoS One. 2014;9(7):e101848. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0101848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Christiansson L, Soderlund S, Svensson E, Mustjoki S, Bengtsson M, Simonsson B, Olsson-Stromberg U, Loskog AS. Increased level of myeloid-derived suppressor cells, programmed death receptor ligand 1/programmed death receptor 1, and soluble CD25 in Sokal high risk chronic myeloid leukemia. PLoS One. 2013;8(1):e55818. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Solito S, Marigo I, Pinton L, Damuzzo V, Mandruzzato S, Bronte V. Myeloid-derived suppressor cell heterogeneity in human cancers. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2014;1319:47–65. doi: 10.1111/nyas.12469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pak AS, Wright MA, Matthews JP, Collins SL, Petruzzelli GJ, Young MR. Mechanisms of immune suppression in patients with head and neck cancer: presence of CD34(+) cells which suppress immune functions within cancers that secrete granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor. Clin Cancer Res. 1995;1(1):95–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Duechler M, Peczek L, Zuk K, Zalesna I, Jeziorski A, Czyz M. The heterogeneous immune microenvironment in breast cancer is affected by hypoxia-related genes. Immunobiology. 2014;219(2):158–165. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2013.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Achberger S, Aldrich W, Tubbs R, Crabb JW, Singh AD, Triozzi PL. Circulating immune cell and microRNA in patients with uveal melanoma developing metastatic disease. Mol Immunol. 2014;58(2):182–186. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2013.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Finkelstein SE, Carey T, Fricke I, Yu D, Goetz D, Gratz M, Dunn M, Urbas P, Daud A, DeConti R, Antonia S, Gabrilovich D, Fishman M. Changes in dendritic cell phenotype after a new high-dose weekly schedule of interleukin-2 therapy for kidney cancer and melanoma. J Immunother. 2010;33(8):817–827. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e3181ecccad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Weide B, Martens A, Zelba H, Stutz C, Derhovanessian E, Di Giacomo AM, Maio M, Sucker A, Schilling B, Schadendorf D, Buttner P, Garbe C, Pawelec G. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells predict survival of patients with advanced melanoma: comparison with regulatory T cells and NY-ESO-1- or melan-A-specific T cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20(6):1601–1609. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-2508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Gabrilovich DI, Nagaraj S. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells as regulators of the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9(3):162–174. doi: 10.1038/nri2506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Verschoor CP, Johnstone J, Millar J, Dorrington MG, Habibagahi M, Lelic A, Loeb M, Bramson JL, Bowdish DM. Blood CD33(+)HLA-DR(−) myeloid-derived suppressor cells are increased with age and a history of cancer. J Leukoc Biol. 2013;93(4):633–637. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0912461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rosmarin AG, Yang Z, Resendes KK. Transcriptional regulation in myelopoiesis: hematopoietic fate choice, myeloid differentiation, and leukemogenesis. Exp Hematol. 2005;33(2):131–143. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2004.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhu J, Emerson SG. Hematopoietic cytokines, transcription factors and lineage commitment. Oncogene. 2002;21(21):3295–3313. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Friedman AD. Transcriptional regulation of granulocyte and monocyte development. Oncogene. 2002;21(21):3377–3390. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Iwasaki H, Akashi K. Myeloid lineage commitment from the hematopoietic stem cell. Immunity. 2007;26(6):726–740. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Nagai Y, Garrett KP, Ohta S, Bahrun U, Kouro T, Akira S, Takatsu K, Kincade PW. Toll-like receptors on hematopoietic progenitor cells stimulate innate immune system replenishment. Immunity. 2006;24(6):801–812. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.King KY, Goodell MA. Inflammatory modulation of HSCs: viewing the HSC as a foundation for the immune response. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11(10):685–692. doi: 10.1038/nri3062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Vahedi G, Poholek AC, Hand TW, Laurence A, Kanno Y, O’Shea JJ, Hirahara K. Helper T-cell identity and evolution of differential transcriptomes and epigenomes. Immunol Rev. 2013;252(1):24–40. doi: 10.1111/imr.12037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Schiavoni G, Mattei F, Sestili P, Borghi P, Venditti M, Morse HC, 3rd, Belardelli F, Gabriele L. ICSBP is essential for the development of mouse type I interferon-producing cells and for the generation and activation of CD8alpha(+) dendritic cells. J Exp Med. 2002;196(11):1415–1425. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tailor P, Tamura T, Kong HJ, Kubota T, Kubota M, Borghi P, Gabriele L, Ozato K. The feedback phase of type I interferon induction in dendritic cells requires interferon regulatory factor 8. Immunity. 2007;27(2):228–239. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gabriele L, Ozato K. The role of the interferon regulatory factor (IRF) family in dendritic cell development and function. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2007;18(5–6):503–510. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2007.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Tamura T, Tailor P, Yamaoka K, Kong HJ, Tsujimura H, O’Shea JJ, Singh H, Ozato K. IFN regulatory factor-4 and -8 govern dendritic cell subset development and their functional diversity. J Immunol. 2005;174(5):2573–2581. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.5.2573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Holtschke T, Lohler J, Kanno Y, Fehr T, Giese N, Rosenbauer F, Lou J, Knobeloch KP, Gabriele L, Waring JF, Bachmann MF, Zinkernagel RM, Morse HC, 3rd, Ozato K, Horak I. Immunodeficiency and chronic myelogenous leukemia-like syndrome in mice with a targeted mutation of the ICSBP gene. Cell. 1996;87(2):307–317. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81348-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Scheller M, Foerster J, Heyworth CM, Waring JF, Lohler J, Gilmore GL, Shadduck RK, Dexter TM, Horak I. Altered development and cytokine responses of myeloid progenitors in the absence of transcription factor, interferon consensus sequence binding protein. Blood. 1999;94(11):3764–3771. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Tsujimura H, Tamura T, Ozato K. Cutting edge: IFN consensus sequence binding protein/IFN regulatory factor 8 drives the development of type I IFN-producing plasmacytoid dendritic cells. J Immunol. 2003;170(3):1131–1135. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.3.1131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Schiavoni G, Mattei F, Borghi P, Sestili P, Venditti M, Morse HC, 3rd, Belardelli F, Gabriele L. ICSBP is critically involved in the normal development and trafficking of Langerhans cells and dermal dendritic cells. Blood. 2004;103(6):2221–2228. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-09-3007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Scharton-Kersten T, Contursi C, Masumi A, Sher A, Ozato K. Interferon consensus sequence binding protein-deficient mice display impaired resistance to intracellular infection due to a primary defect in interleukin 12 p40 induction. J Exp Med. 1997;186(9):1523–1534. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.9.1523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Fehr T, Schoedon G, Odermatt B, Holtschke T, Schneemann M, Bachmann MF, Mak TW, Horak I, Zinkernagel RM. Crucial role of interferon consensus sequence binding protein, but neither of interferon regulatory factor 1 nor of nitric oxide synthesis for protection against murine listeriosis. J Exp Med. 1997;185(5):921–931. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.5.921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Hambleton S, Salem S, Bustamante J, Bigley V, Boisson-Dupuis S, Azevedo J, Fortin A, Haniffa M, Ceron-Gutierrez L, Bacon CM, Menon G, Trouillet C, McDonald D, Carey P, Ginhoux F, Alsina L, Zumwalt TJ, Kong XF, Kumararatne D, Butler K, Hubeau M, Feinberg J, Al-Muhsen S, Cant A, Abel L, Chaussabel D, Doffinger R, Talesnik E, Grumach A, Duarte A, Abarca K, Moraes-Vasconcelos D, Burk D, Berghuis A, Geissmann F, Collin M, Casanova JL, Gros P. IRF8 mutations and human dendritic-cell immunodeficiency. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(2):127–138. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1100066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Tamura T, Thotakura P, Tanaka TS, Ko MS, Ozato K. Identification of target genes and a unique cis element regulated by IRF-8 in developing macrophages. Blood. 2005;106(6):1938–1947. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-01-0080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Dror N, Alter-Koltunoff M, Azriel A, Amariglio N, Jacob-Hirsch J, Zeligson S, Morgenstern A, Tamura T, Hauser H, Rechavi G, Ozato K, Levi BZ. Identification of IRF-8 and IRF-1 target genes in activated macrophages. Mol Immunol. 2007;44(4):338–346. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2006.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wang IM, Contursi C, Masumi A, Ma X, Trinchieri G, Ozato K. An IFN-gamma-inducible transcription factor, IFN consensus sequence binding protein (ICSBP), stimulates IL-12 p40 expression in macrophages. J Immunol. 2000;165(1):271–279. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.1.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Giese NA, Gabriele L, Doherty TM, Klinman DM, Tadesse-Heath L, Contursi C, Epstein SL, Morse HC., 3rd Interferon (IFN) consensus sequence-binding protein, a transcription factor of the IFN regulatory factor family, regulates immune responses in vivo through control of interleukin 12 expression. J Exp Med. 1997;186(9):1535–1546. doi: 10.1084/jem.186.9.1535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Liu J, Ma X. Interferon regulatory factor 8 regulates RANTES gene transcription in cooperation with interferon regulatory factor-1, NF-kappaB, and PU.1. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(28):19188–19195. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602059200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Mullins DW, Martins RS, Elgert KD. Tumor-derived cytokines dysregulate macrophage interferon-gamma responsiveness and interferon regulatory factor-8 expression. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2003;228(3):270–277. doi: 10.1177/153537020322800305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Tamura T, Yanai H, Savitsky D, Taniguchi T. The IRF family transcription factors in immunity and oncogenesis. Annu Rev Immunol. 2008;26:535–584. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.26.021607.090400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Driggers PH, Ennist DL, Gleason SL, Mak WH, Marks MS, Levi BZ, Flanagan JR, Appella E, Ozato K. An interferon gamma-regulated protein that binds the interferon-inducible enhancer element of major histocompatibility complex class I genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87(10):3743–3747. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.10.3743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kanno Y, Kozak CA, Schindler C, Driggers PH, Ennist DL, Gleason SL, Darnell JE, Jr, Ozato K. The genomic structure of the murine ICSBP gene reveals the presence of the gamma interferon-responsive element, to which an ISGF3 alpha subunit (or similar) molecule binds. Mol Cell Biol. 1993;13(7):3951–3963. doi: 10.1128/mcb.13.7.3951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Nguyen H, Hiscott J, Pitha PM. The growing family of interferon regulatory factors. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 1997;8(4):293–312. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6101(97)00019-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Tamura T, Ozato K. ICSBP/IRF-8: its regulatory roles in the development of myeloid cells. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2002;22(1):145–152. doi: 10.1089/107999002753452755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Politis AD, Ozato K, Coligan JE, Vogel SN. Regulation of IFN-gamma-induced nuclear expression of IFN consensus sequence binding protein in murine peritoneal macrophages. J Immunol. 1994;152(5):2270–2278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Zhao J, Kong HJ, Li H, Huang B, Yang M, Zhu C, Bogunovic M, Zheng F, Mayer L, Ozato K, Unkeless J, Xiong H. IRF-8/interferon (IFN) consensus sequence-binding protein is involved in Toll-like receptor (TLR) signaling and contributes to the cross-talk between TLR and IFN-gamma signaling pathways. J Biol Chem. 2006;281(15):10073–10080. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507788200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Weisz A, Marx P, Sharf R, Appella E, Driggers PH, Ozato K, Levi BZ. Human interferon consensus sequence binding protein is a negative regulator of enhancer elements common to interferon-inducible genes. J Biol Chem. 1992;267(35):25589–25596. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Schmidt M, Nagel S, Proba J, Thiede C, Ritter M, Waring JF, Rosenbauer F, Huhn D, Wittig B, Horak I, Neubauer A. Lack of interferon consensus sequence binding protein (ICSBP) transcripts in human myeloid leukemias. Blood. 1998;91(1):22–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Marigo I, Bosio E, Solito S, Mesa C, Fernandez A, Dolcetti L, Ugel S, Sonda N, Bicciato S, Falisi E, Calabrese F, Basso G, Zanovello P, Cozzi E, Mandruzzato S, Bronte V. Tumor-induced tolerance and immune suppression depend on the C/EBPbeta transcription factor. Immunity. 2010;32(6):790–802. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Thevenot PT, Sierra RA, Raber PL, Al-Khami AA, Trillo-Tinoco J, Zarreii P, Ochoa AC, Cui Y, Del Valle L, Rodriguez PC. The stress-response sensor chop regulates the function and accumulation of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in tumors. Immunity. 2014;41(3):389–401. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Zhang W, Pal SK, Liu X, Yang C, Allahabadi S, Bhanji S, Figlin RA, Yu H, Reckamp KL. Myeloid clusters are associated with a pro-metastatic environment and poor prognosis in smoking-related early stage non-small cell lung cancer. PLoS One. 2013;8(5):e65121. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Postow MA, Callahan MK, Barker CA, Yamada Y, Yuan J, Kitano S, Mu Z, Rasalan T, Adamow M, Ritter E, Sedrak C, Jungbluth AA, Chua R, Yang AS, Roman RA, Rosner S, Benson B, Allison JP, Lesokhin AM, Gnjatic S, Wolchok JD. Immunologic correlates of the abscopal effect in a patient with melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(10):925–931. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1112824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Chen G, Emens LA. Chemoimmunotherapy: reengineering tumor immunity. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2013;62(2):203–216. doi: 10.1007/s00262-012-1388-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.James BR, Anderson KG, Brincks EL, Kucaba TA, Norian LA, Masopust D, Griffith TS. CpG-mediated modulation of MDSC contributes to the efficacy of Ad5-TRAIL therapy against renal cell carcinoma. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2014;63(11):1213–1227. doi: 10.1007/s00262-014-1598-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Bronte V, Serafini P, Apolloni E, Zanovello P. Tumor-induced immune dysfunctions caused by myeloid suppressor cells. J Immunother. 2001;24(6):431–446. doi: 10.1097/00002371-200111000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Qin H, Lerman B, Sakamaki I, Wei G, Cha SC, Rao SS, Qian J, Hailemichael Y, Nurieva R, Dwyer KC, Roth J, Yi Q, Overwijk WW, Kwak LW. Generation of a new therapeutic peptide that depletes myeloid-derived suppressor cells in tumor-bearing mice. Nat Med. 2014;20(6):676–681. doi: 10.1038/nm.3560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Shojaei F, Wu X, Qu X, Kowanetz M, Yu L, Tan M, Meng YG, Ferrara N. G-CSF-initiated myeloid cell mobilization and angiogenesis mediate tumor refractoriness to anti-VEGF therapy in mouse models. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106(16):6742–6747. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0902280106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Waight JD, Hu Q, Miller A, Liu S, Abrams SI. Tumor-derived G-CSF facilitates neoplastic growth through a granulocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cell-dependent mechanism. PLoS One. 2011;6(11):e27690. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Bayne LJ, Beatty GL, Jhala N, Clark CE, Rhim AD, Stanger BZ, Vonderheide RH. Tumor-derived granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor regulates myeloid inflammation and T cell immunity in pancreatic cancer. Cancer Cell. 2012;21(6):822–835. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.04.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Reeves G. Overview of use of G-CSF and GM-CSF in the treatment of acute radiation injury. Health Phys. 2014;106(6):699–703. doi: 10.1097/HP.0000000000000090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Kaufman HL, Ruby CE, Hughes T, Slingluff CL., Jr Current status of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor in the immunotherapy of melanoma. J Immunother Cancer. 2014;2:11. doi: 10.1186/2051-1426-2-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Nutt SL, Morrison AM, Dorfler P, Rolink A, Busslinger M. Identification of BSAP (Pax-5) target genes in early B-cell development by loss- and gain-of-function experiments. EMBO J. 1998;17(8):2319–2333. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.8.2319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Dimberg A, Karehed K, Nilsson K, Oberg F. Inhibition of monocytic differentiation by phosphorylation-deficient Stat1 is associated with impaired expression of Stat2, ICSBP/IRF8 and C/EBPepsilon. Scand J Immunol. 2006;64(3):271–279. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2006.01827.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Iclozan C, Antonia S, Chiappori A, Chen DT, Gabrilovich D. Therapeutic regulation of myeloid-derived suppressor cells and immune response to cancer vaccine in patients with extensive stage small cell lung cancer. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2013;62(5):909–918. doi: 10.1007/s00262-013-1396-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Couzin-Frankel J. Breakthrough of the year 2013. Cancer immunotherapy. Science. 2013;342(6165):1432–1433. doi: 10.1126/science.342.6165.1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Rolinski J, Hus I. Breaking immunotolerance of tumors: a new perspective for dendritic cell therapy. J Immunotoxicol. 2014;11(4):311–318. doi: 10.3109/1547691X.2013.865094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Jochems C, Tucker JA, Tsang KY, Madan RA, Dahut WL, Liewehr DJ, Steinberg SM, Gulley JL, Schlom J. A combination trial of vaccine plus ipilimumab in metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer patients: immune correlates. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2014;63(4):407–418. doi: 10.1007/s00262-014-1524-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Tarhini AA, Butterfield LH, Shuai Y, Gooding WE, Kalinski P, Kirkwood JM. Differing patterns of circulating regulatory T cells and myeloid-derived suppressor cells in metastatic melanoma patients receiving anti-CTLA4 antibody and interferon-alpha or TLR-9 agonist and GM-CSF with peptide vaccination. J Immunother. 2012;35(9):702–710. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e318272569b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Tarhini AA, Edington H, Butterfield LH, Lin Y, Shuai Y, Tawbi H, Sander C, Yin Y, Holtzman M, Johnson J, Rao UN, Kirkwood JM. Immune monitoring of the circulation and the tumor microenvironment in patients with regionally advanced melanoma receiving neoadjuvant ipilimumab. PLoS One. 2014;9(2):e87705. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Wu P, Wu D, Ni C, Ye J, Chen W, Hu G, Wang Z, Wang C, Zhang Z, Xia W, Chen Z, Wang K, Zhang T, Xu J, Han Y, Zhang T, Wu X, Wang J, Gong W, Zheng S, Qiu F, Yan J, Huang J. gammadeltaT17 cells promote the accumulation and expansion of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in human colorectal cancer. Immunity. 2014;40(5):785–800. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Annels NE, Shaw VE, Gabitass RF, Billingham L, Corrie P, Eatock M, Valle J, Smith D, Wadsley J, Cunningham D, Pandha H, Neoptolemos JP, Middleton G. The effects of gemcitabine and capecitabine combination chemotherapy and of low-dose adjuvant GM-CSF on the levels of myeloid-derived suppressor cells in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2014;63(2):175–183. doi: 10.1007/s00262-013-1502-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Monk P, Lam E, Mortazavi A, Kendra K, Lesinski GB, Mace TA, Geyer S, Carson WE, 3rd, Tahiri S, Bhinder A, Clinton SK, Olencki T. A phase I study of high-dose interleukin-2 with sorafenib in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma and melanoma. J Immunother. 2014;37(3):180–186. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0000000000000023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Kudo-Saito C, Yura M, Yamamoto R, Kawakami Y. Induction of immunoregulatory CD271+ cells by metastatic tumor cells that express human endogenous retrovirus H. Cancer Res. 2014;74(5):1361–1370. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-1349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]