Abstract

Context:

Low concentrations of estradiol and progesterone are hallmarks of adverse pregnancy outcomes as is maternal obesity. During pregnancy, placental cholesterol is the sole source of sex steroids. Cholesterol trafficking is the limiting step in sex steroid biosynthesis and is mainly mediated by the translocator protein (TSPO), present in the mitochondrial outer membrane.

Objective:

The objective of the study was to investigate the effects of maternal obesity in placental sex steroid biosynthesis and TSPO regulation.

Design/Participants:

One hundred forty-four obese (body mass index 30–35 kg/m2) and 90 lean (body mass index 19–25 kg/m2) pregnant women (OP and LP, respectively) recruited at scheduled term cesarean delivery. Placenta and maternal blood were collected.

Setting:

This study was conducted at MetroHealth Medical Center (Cleveland, Ohio).

Main Outcome Measures:

Maternal metabolic components (fasting glucose, insulin, leptin, estradiol, progesterone, and total cholesterol) and placental weight were measured. Placenta (mitochondria and membranes separated) and cord blood cholesterol values were verified. The expression and regulation of TSPO and mitochondrial function were analyzed.

Results:

Plasma estradiol and progesterone concentrations were significantly lower (P < .04) in OP as compared with LP women. Maternal and cord plasma cholesterol were not different between groups. Placental citrate synthase activity and mitochondrial DNA, markers of mitochondrial density, were unchanged, but the mitochondrial cholesterol concentrations were 40% lower in the placenta of OP. TSPO gene and protein expressions were decreased 2-fold in the placenta of OP. In vitro trophoblast activation of the innate immune pathways with lipopolysaccharide and long-chain saturated fatty acids reduced TSPO expression by 2- to 3-fold (P < .05).

Conclusion:

These data indicate that obesity in pregnancy impairs mitochondrial steroidogenic function through the negative regulation of mitochondrial TSPO.

Early in development, the placenta takes over the ovarian steroidogenic function and becomes the main source of progesterone and estrogen synthesis during pregnancy. Both steroid hormones are involved in the maintenance of pregnancy from the establishment to parturition. Progesterone suppresses the maternal immune system against fetal antigens at the time of implantation. In addition to maintaining the correct uterine environment, progesterone promotes the quiescence of the myometrium, opposing the labor-inducing effects of estrogens, prostaglandins, and oxytocin (1). On the other hand, estradiol facilitates the adaptation of uterine blood flow and myometrial growth, stimulates breast growth, and promotes cervical softening at term (2).

The placental steroidogenesis and metabolism of progesterone and estradiol have to constantly evolve throughout the course of pregnancy to meet an 8-fold increase in maternal circulating levels from 6 weeks to term (3). Lower-than-normal plasma levels of progesterone or estradiol are associated with an increased risk of adverse pregnancy outcome. Progesterone deficiency is associated with a higher probability of abortion and is commonly detected in recurrent miscarriages.

Sex steroids also exert profound effects on adipose tissue and lipid metabolism. Estrogens directly impact adipocyte physiology through the regulation of differentiation (4). Estrogen also promotes and maintains the typical female type of fat distribution that is characterized by accumulation of adipose tissue by lowering lipolysis in the sc fat depot (5). The importance of estrogens in regulating the sc fat accumulation has also been shown in men and menopausal women (6). It has been proposed that the absence of estrogens may be an important obesity-triggering factor (7). Furthermore, estrogen deficiency enhances metabolic dysfunction predisposing to type 2 diabetes, metabolic syndrome, and cardiovascular diseases (8).

In the placenta, as in all steroidogenic tissues, cholesterol is the primary precursor for estrogen and progesterone synthesis. The first and rate-limiting and hormonally regulated step in the biosynthesis of steroid hormones is the transfer of cholesterol from the cytoplasm into the mitochondria. Cholesterol trafficking and import into the mitochondria is facilitated by the steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (StAR) in most steroidogenic tissues. The human placenta does not express StAR, and it has been proposed that the protein metastatic lymph node protein 64 (MLN64) performs the activity of placental cholesterol transporter (9). StAR/MLN64 action requires a complex multicomponent molecular machine on the outer mitochondrial membrane, which includes the 18-kDa translocator protein (TSPO) and the voltage-dependent anion channel (VDAC)-1 (10). TSPO is a high-affinity, cholesterol binding protein localized in the outer mitochondrial membrane, which is expressed in a tissue-specific manner. Recent data indicate that TSPO is a highly regulated protein. The aberrant expression of TSPO has been linked to multiple diseases including cancer and neurodegeneration (11). TSPO expression is increased during adipocyte differentiation and is down-regulated in white and brown adipose tissue of obese mice (12). Obesity is also associated with multiple defects in mitochondrial dynamics and function (13).

Given the decrease in plasma progesterone and evidence of mitochondrial abnormalities in obese individuals, we postulated that sex steroid hormone synthesis is impaired in the placenta of obese women. The primary aim of this study was to assess the regulation of progesterone and estradiol production in lean and obese women. Secondarily, because the placenta does not express STAR, we aimed to characterize the role of cholesterol transporter TSPO as a potential regulator of steroid biosynthesis in pregnancy with obesity.

Subjects and Methods

Human subjects

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of MetroHealth Medical Center (Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, Ohio). A prospective cohort of healthy women with a wide range of pregravid body mass indices (BMI; 19.9–62.3 kg/m2) was recruited at 38.5–40 weeks of pregnancy prior to a scheduled cesarean section. Subjects with multiple gestation, fetal anomalies, intrauterine growth restriction, preeclampsia, and diabetes (preexisting and gestational) were excluded. All subjects provided written informed consent prior to the collection of maternal blood and placenta. Maternal pregravid BMI was obtained from medical records. The anthropometric and metabolic parameters obtained from 234 women and neonates are presented in Table 1. The variables included weight on a calibrated scale and length using a measuring board (14). Each placenta was weighed after the umbilical cord and fetal membranes were trimmed by research staff.

Table 1.

Maternal Characteristics of the Study Cohort

| Maternal Age, y | Gestational Age, wk | Maternal BMI, kg/m2 | Leptin, ng/mL | Insulin, μU/mL | Glucose, mg/dL | HOMA-IR index | Placenta Weight, g | Birth Weight, kg | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lean (BMI < 25 kg/m2) | 28.5 ± 5.9 | 38.9 ± 0.6 | 22.2 ± 1.9 | 25.0 ± 13.3 | 12.4 ± 6.0 | 74 ± 8 | 2.3 ± 1.3 | 650 ± 163 | 3.24 ± 0.46 |

| Obese (BMI > 30 kg/m2) | 27.5 ± 5.8 | 38.9 ± 0.7 | 38.1 ± 6.4 | 71.6 ± 26.5 | 21.7 ± 9.4 | 79 ± 9 | 4.3 ± 2.3 | 669 ± 159 | 3.28 ± 0.47 |

| P value | .2 | .5 | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.0001 | <.001 | <.0001 | .6 | .5 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index pregravid; HOMA-IR, homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance. Data are expressed as means ± SD with 144 obese and 90 lean subjects.

Biological specimen collection

Blood and tissue samples were obtained from 234 women after an 8- to 10-hour fast. Maternal venous blood (10 mL) samples were collected prior to placement of iv lines for hydration before the cesarean section. A 5-mL aliquot was drawn into EDTA tubes, and after separation, plasma was kept frozen (−20°C). The placenta was obtained immediately after the double clamping of the umbilical cord to draw venous fetal blood. Fragments of deep villous tissue (0.5 × 2 cm; ∼1 cm depth from the maternal surface) were removed from cotyledons proximal to the cord insertion. All placental fragments were washed three times in cold sterile PBS and were quickly blotted on sterile gauze to minimize the amount of intervillous blood trapped into the villous tissue. Placenta tissue fragments (∼300 mg) were flash frozen in liquid nitrogen within 10 minutes of delivery and were stored at −80°C for later molecular analysis. Primary trophoblast cells were isolated by sequential trypsin and deoxyribonuclease digestion followed by gradient centrifugation (15).

RNA preparation and real-time PCR

RNA was extracted from placenta tissue using the RNeasy kit (QIAGEN Inc). RNA was reversed transcribed using a Superscript II ribonuclease H-reverse transcriptase system (Invitrogen). TSPO, 17-β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (HSD) Type 1 (17β-HSD1), 3β-HSD1, and actin gene expression levels were measured by real-time PCR using a LightCycler FastStart DNA Master SYBR Green I kit (Roche). Amplifications were performed in duplicate using 20-ng cDNA samples with the following primers pairs: TSPO (NM_000714.5), forward, 5′-tcgcgaccacactcaactac-3′, and reverse, 5′-caaggccctgacagactagc-3′; β-actin (NM_001101), forward, 5′-ggacttcgagcaagagatgg-3′, and reverse, 5′-agcactgtgttggcgtacag-3′; 17β-HSD1 (NM_000413.2), forward, 5′-tccaggtacagcattgacca-3′, and reverse, 5′-gattcaggcttttggtggaa-3′; and 3βHSD1 (NM_000862.2), forward, 5′-tctcagatgacacgcctcac-3′, and reverse, 5′-tcccagctgtagagtggctt-3′. Results were normalized for actin and expressed as fold changes using the ΔΔCt (cycle threshold) method. All reactions were done in eight samples, in duplicates, in each group.

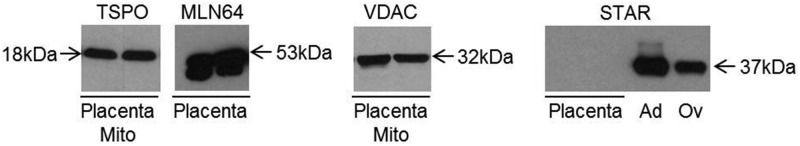

Protein detection by Western blot

Placental homogenates (15 μg/lane) or isolated mitochondria (30 μg/lane) were electrophoresed under denaturing conditions and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Membranes containing placental homogenates were blocked overnight with milk 5% in 1× PBS-0.01% Tween 20 and incubated with anti-β-actin or β-tubulin primary antibodies (1:5000 and 1:2000 dilutions, sc130301 and sc86255, respectively; Santa Cruz Biotechnology) for 1 hour at room temperature or overnight with anti-StAR antibody (number 8449; Cell Signaling Technology) or anti-17β-HSD1 (ab51045; Abcam Inc) or anti-MLN64 (ab3478; Abcam Inc) in 1:1000, 1:100 000, and 1:1000 dilutions, respectively. Goat antirabbit IgG, rabbit (dilutions 1:2000 or 1:25 000 for 17β-HSD1), antimouse (1:2000 dilution), and donkey antigoat (1:2000 dilution) horseradish peroxidase conjugated were used as secondary antibodies. Membranes containing isolated mitochondria were blocked overnight with 5% BSA in 1× PBS-0.01% Tween 20 and incubated overnight with anti-TSPO (number 9530; Cell Signaling Technology) or anti VDAC (ab14734; Abcam Inc) in 1:1000 and 1:50 000 dilutions, respectively. Immunocomplexes were visualized by chemiluminescence (Amersham). Densitometry analysis and quantification were performed using the image analysis software GelAnalyzer (www.gelanalyzer.com/index.html). Mice adrenal gland and ovary lysates were used as the positive control for STAR expression. VDAC was used as loading control for mitochondria samples and β-actin for tissue lysates.

Plasma assays using ELISA

Plasma glucose was assessed by the glucose oxidase method. Plasma insulin was measured using an ELISA (EMD Millipore Corp). Leptin (R&D Systems) was measured using ELISA kits with intraassay coefficients of variation of 6.2%–8.4%. Insulin resistance was estimated using a homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance as a ratio of fasting plasma insulin (microunits per milliliter) to fasting plasma glucose ([millimoles per liter]/22.5) (22). Total plasma cholesterol was measured using an Amplex red cholesterol assay kit (A12216; Invitrogen) and normalized by total protein. Progesterone and estradiol were measured using ELISA kits (ENZO Life Sciences and ALPCO, respectively). All plasma samples were assayed in duplicate.

Cell fractioning for mitochondria and cellular membranes isolation

For the cellular fractioning, frozen placental tissue (5g) was rinsed and minced in ice-cold buffer of 220 mM D-mannitol, 70 mM sucrose, and 5 mM 3[N-morpholino]propanesulfonic acid (MSM). Minced tissue was rinsed twice in MSM buffer and resuspended in MSM+ buffer (MMS plus 2 mM EDTA and 0.2% fatty acid free BSA). Suspension was homogenized with three strokes of a loose-fitting pestle in a Potter-Elvehjem homogenizer at approximately 1000 revolutions per minute. Homogenate was centrifuged at 300 × g at 4°C for 10 minutes and supernatant decanted through gauze. The pellet was resuspended in 10 mL MSM+, homogenized, and centrifuged as above. Again the supernatant was decanted and combined with the first one. At this point cellular debris and nuclei were eliminated and supernatants contain cellular membranes and small vesicles. The combined supernatants were centrifuged at 7000 × g at 4°C for 15 minutes. The supernatant containing the cellular membranes was collected for cholesterol measurements, and the pellet containing the mitochondria fraction was washed in MSM and centrifuged again as before. The final mitochondrial pellet was resuspended in MSM and used for cholesterol measurements and Western blots. Total protein concentration of each fraction was determined using a BCA protein assay kit (catalog number 23227; Pierce).

Citrate synthase activity

Citrate synthase activity was determined as described (16) using a diode array spectrophotometer at a wavelength of 412 nm.

Determination of mitochondrial (mt) DNA copy number

For the quantitative determination of mtDNA content relative to nuclear DNA, specific primers for mitochondrial cytochrome B (cytB) and nuclear β-actin genes were designed. Amplifications were performed in duplicate using 200 ng of DNA samples with the following primers pairs: cytB forward, 5′-CCAACATCTCCGCATGATGAAAC-3′, and reverse, 5′-TGAGTAGCCTCCTCAGATTC-3′, and β-actin forward, 5′-ATC ATG TTT GAG ACC TTC AAC A-3′, and reverse, 5′-CAT CTC TTG CTC GAA GTC CA-3′. For each PCR run, separate standard curves were generated using female genomic DNA. The copy number of the mtDNA cytB in each tested sample was then normalized against that of the β-actin gene to calculate the relative mtDNA copy number. All reactions were done in 12 samples per group, in duplicates.

Cholesterol extraction from cellular fractions and measurement

A mixture of chloroform- isopropanol-Nonidet P-40 (7:11:0.1) was added to each sample followed by homogenization with a vortex. The extract was centrifuged at 15 000 × g for 10 minutes. The organic phase (supernatant) was collected and centrifuged under vacuum to dry and remove the trace amounts of organic solvent. Dried lipids were dissolved in 1× assay diluent from the Amplex Red cholesterol assay kit, and total cholesterol was measured according to manufacturer's instructions (Amplex red cholesterol assay kit, number A12216; Invitrogen). Results were normalized by total protein.

Human trophoblast cell culture

Primary isolated trophoblast cells were plated into 12-well plates at a density of 1.5 × 106 cells/well and cultured overnight in Iscoves's modified DMEM culture medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin at 37°C under 5% CO2. Then DMEM with 10% FBS was used for 4 hours and DMEM with 1% FBS for 1 hour. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) or fatty acids (myristic acid, palmitic acid, and oleic acid) were added into the medium at final concentrations of 100 ng/mL or 400 μM, respectively. PBS and 2% BSA were added to the medium as controls. LPS and all the fatty acids were from Sigma. BSA was fatty acid free.

Statistical analyses

Values are represented as mean ± SD in Table 1 and as mean ± SEM in the figures. Statistical mean differences were calculated by a Student's t test. Statistical significance was set at P < .05.

Results

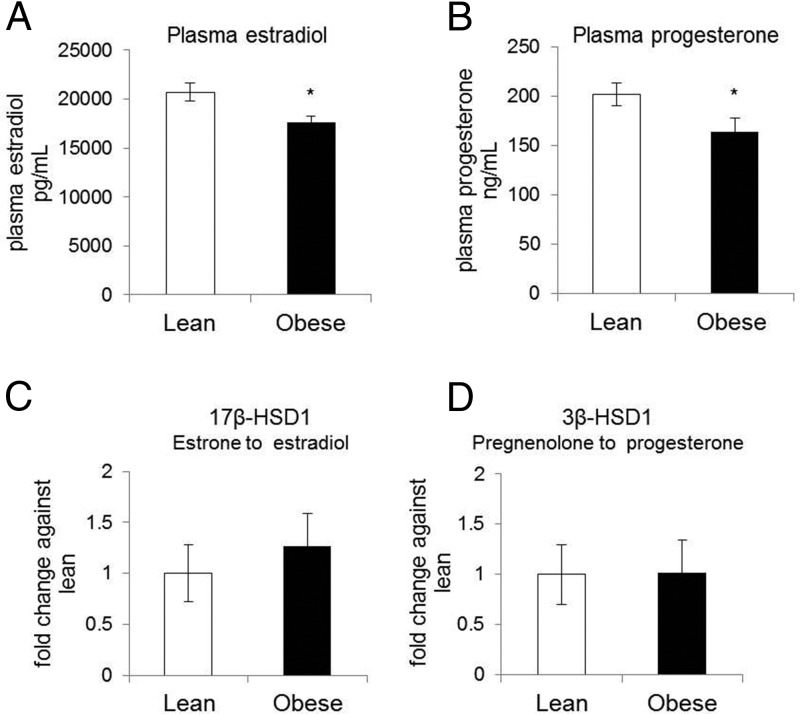

Decreased estradiol and progesterone plasma concentrations in obese pregnant women

To investigate the effect of obesity on circulating sex steroid hormone levels, plasma estradiol and progesterone concentrations were measured in a cohort of 90 lean and 144 obese pregnant women. Characteristics of the cohort (n = 234) are given in Table 1. Obese women (mean BMI 38.8 ± 6.4 kg/m2) were less insulin sensitive (P < .001) and had leptin levels 3-fold higher (P < .0001) than lean women (mean BMI 22.2 ± 1.9 kg/m2). The circulating levels of both estradiol and progesterone were lower in obese compared with lean (17 602 ± 8390 vs 20 725 ± 7472 pg/mL, P < .03, and 164 ± 83 vs 201 ± 79 ng/mL, P < .04, Figure 1, A and B). 17β-HSD1 and 3β-HSD1 are key enzymes involved in the conversion of estrone into estradiol and pregnenolone into progesterone, respectively. There were no significant differences in the expression of both enzymes (Figure 1, C and D) in total placental tissue, suggesting that these enzymes are not involved in the decreased sex steroid concentrations found in the obese women. Expression of the cytochrome P450 (P450 cholesterol side chain cleavage) was also not different in placenta from lean vs obese women (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Plasma estradiol and progesterone concentrations in lean and obese pregnant women and expression of rate limiting enzymes for their synthesis. Estradiol (A) and progesterone (B) plasma concentrations were measured in the study cohort (n = 234) as described in Table 1. C and D, 17β-HSD1 and 3β-HSD1 expression was assayed in RNA isolated from total placental tissue and normalized against β-actin. Results are expressed as fold changes against the lean group, considered as 1. Data are expressed as means ± SEM (n = 8 in each group) with *, P < .001.

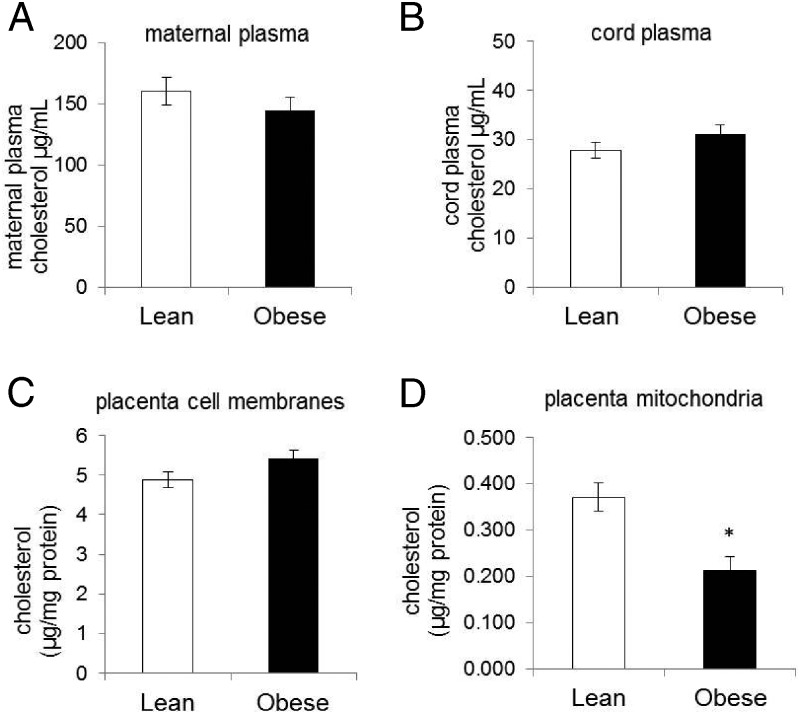

Cholesterol concentration in maternal and cord plasma and in placental subcellular fractions

Cholesterol is the precursor for steroid biosynthesis, and during pregnancy the main source of placental cholesterol is derived from maternal plasma. There was no difference in plasma cholesterol between lean and obese pregnant women (Figure 2A, 160 ± 75 vs 144 ± 74 μg/mL). Fetal cholesterol can also be transported to the placenta and potentially be used in steroidogenesis; however, there were no differences in cholesterol levels in cord plasma derived from neonates of lean and obese women (Figure 1B, 27 ± 12 vs 31 ± 13 μg/mL). Similarly, cholesterol content in placental membranes (plasma membrane and internal cell membranes) was similar in tissue derived from lean and obese women (Figure 2C, 4.88 ± 0.71 vs 5.41 ± 1.3 μg/mg of protein), suggesting that there is no defect of cholesterol transport from plasma of obese women into the placenta. However, mitochondrial cholesterol content was significantly lower in the placenta of obese compared with lean women (Figure 2D, 0.213 ± 0.031 vs 0.371 ± 0.087 μg/mg of protein, P = .01).

Figure 2.

Cholesterol concentration in maternal and cord plasma and in placental cellular fractions. Maternal plasma (A; n = 50) and umbilical cord plasma (B; n = 50) total cholesterol concentrations are shown. Placental tissue was submitted to cell fractionation as described in Materials and Methods, and total cholesterol was measured in the cellular membranes (C; n = 12) and mitochondrial fractions (D; n = 12). Cholesterol content of each fraction of equal volume was measured as described in Materials and Methods and normalized against protein concentration in each sample. Data are expressed as means ± SEM with *, P < .05.

Mitochondrial cholesterol transport in the placenta

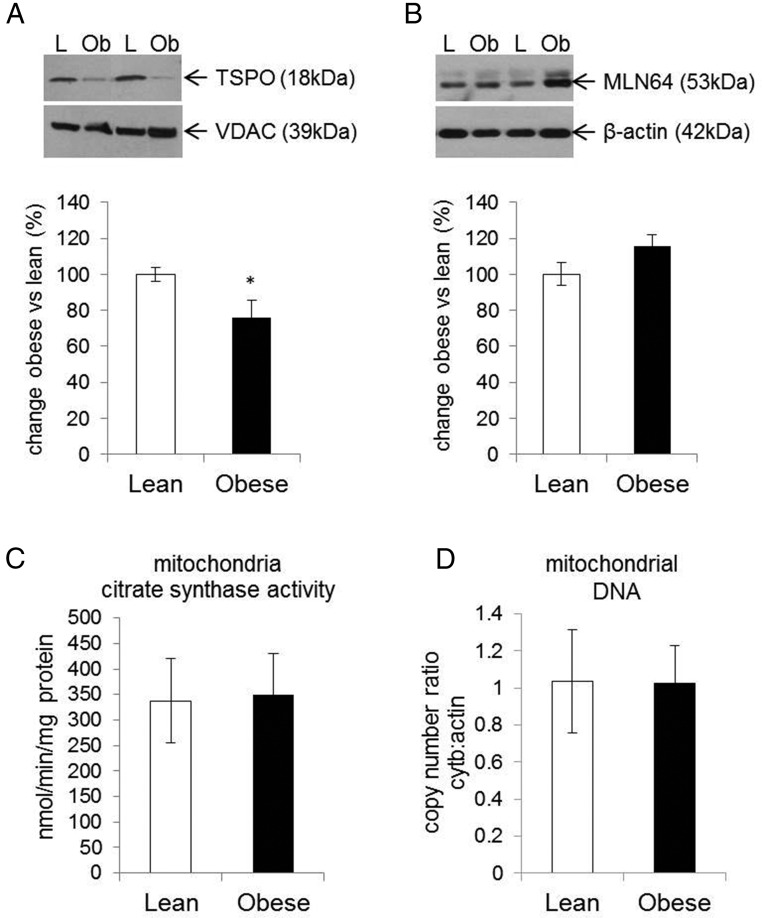

The conversion of cholesterol to pregnenolone, the first step in steroidogenesis, takes place in the mitochondria. The transport of cholesterol from the cytoplasm to the mitochondria is the rate-limiting step in the biosynthesis of steroid hormones. StAR, the classic cholesterol transporter in steroidogenic tissues, is not expressed in the placenta (Figure 3). Instead, the metastatic lymph node protein 64 (MLN64) and the translocator protein 18 kDa (TSPO) are the major placental cholesterol transporters (Figure 3). MLN64 is an integral membrane protein localized to the late endosome and transports cholesterol to several cellular destinations (17). In contrast TSPO is localized in the outer mitochondrial membrane and exclusively transports cholesterol into the mitochondria (18). We hypothesized that regulation of TSPO and/or MLN64 in placenta of obese women could contribute to lower mitochondrial cholesterol. Although there was no difference in MLN64 expression (Figure 4A), TSPO expression was significantly decreased (P < .001) in isolated mitochondria derived from the placenta of obese compared with lean women (Figure 4B).

Figure 3.

Transporters involved in mitochondrial cholesterol trafficking. Protein expression of TSPO and the MLN64/StAR-related lipid transfer domain containing MLN64 was analyzed in the isolated mitochondria and total placental tissue, respectively. The STAR protein expression was verified in total placental tissue. MLN64 and TSPO but not STAR were detected in term human placenta. Protein lysates of mice adrenal glands and ovaries were used as a control for STAR expression. VDAC (loading control) expression was used for the validation mitochondria isolation. Ag, mice adrenal glands; Mito, mitochondria; Ov, mice ovaries.

Figure 4.

Effect of maternal obesity on the expression of placental cholesterol transporters and mitochondria biogenesis. Protein expression of TSPO (A) was characterized in isolated mitochondria and normalized against VDAC (loading control). The MLN64 protein expression (B) was characterized in total placental tissue lysates and normalized against β-actin. Upper panels represent the Western blots and lower graphs the densitometry analysis. Activity of the citrate synthase enzyme was analyzed in isolated mitochondria (C) to confirm mitochondria integrity and as an indirect method for quantification of mitochondria density. Mitochondrial DNA copy number, as a ratio of cytochrome B to β-actin was measured by real-time PCR (D). Results are expressed in obese vs lean group and bars are representative of 12 replicates in each group. Data are expressed as means ± SEM with *, P < .05. L, lean; Ob, obese.

To confirm that the decreased expression of TSPO is not a consequence of lower mitochondria number in placenta derived from obese women, the activity of the citrate synthase enzyme was measured and mtDNA copy number was quantified. The results showed no difference in citrate synthase activity in placental mitochondria derived from lean vs obese women (Figure 4C). The average copy number ratio of mtDNA to nuclear DNA between placenta of lean and obese (Figure 1D) was also not different (1.04 ± 0.28 vs 1.02 ± 0.20), suggesting that obesity is not associated with changes in placental mitochondrial density.

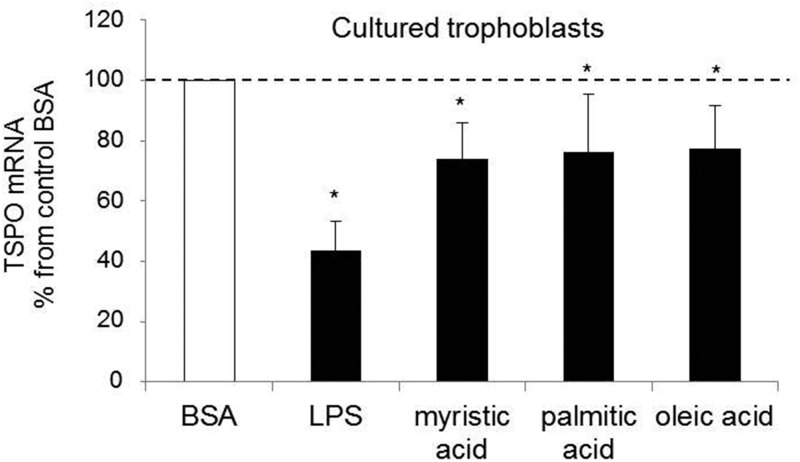

Mechanisms of placental TSPO regulation

Steroidogenesis is inhibited by lipopolysaccharides in Leydig cells (19). We have reported that LPS contributes to placental induced Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) inflammatory signaling in obesity (20). To further investigate TSPO regulation, primary trophoblasts were cultured for 24 hours in the presence of LPS. Treatment with LPS strongly decreased (∼55%, P < .05) TSPO expression (Figure 5). Long-chain saturated fatty acids, myristic acid, palmitate, and oleate, with different degrees of saturation, also had a negative effect in TSPO regulation, leading to a 25% (P < .05) decrease in expression after 24 hours of treatment (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

In vitro regulation of TSPO expression in primary trophoblasts. The TSPO mRNA expression was measured in cultured trophoblast cells treated with BSA (control) or LPS, or palmitic, myristic acid, and oleic acid for 24 hours. The TSPO expression was normalized using β-actin. The data are expressed as means ± SEM, and the statistically significant differences were determined by a Student's t test (*, P < .05.)

Discussion

The primary finding of our study is that the concentrations of estradiol and progesterone are lower in plasma of obese compared with lean pregnant women. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report showing that obesity elicits deficiency in sex steroid hormones during pregnancy. Our results are in line with the plasma concentration of sex steroid hormones being decreased in obese men (21) and in obese menopausal women (6) compared with normal-weight individuals. During pregnancy, sex steroid hormones are exclusively synthesized from placental cholesterol, which essentially relies on maternal supply (22). The initial step of steroidogenesis, the synthesis of pregnenolone from cholesterol, takes place in the mitochondria. Hence, we examined the mechanisms regulating cholesterol availability and placental mitochondrial function as potential culprit for decreased steroid synthesis.

Maternal plasma cholesterol was similar in obese and normal-weight pregnant women. Additionally, there was no difference in the total placental pool of cholesterol, indicating that the uptake of exogenous cholesterol from maternal circulation into the placenta was not impaired in obesity. By contrast, we found a significant decrease in the cholesterol content of placental mitochondrial extracts in obese compared with lean women. Cholesterol trafficking from the outer milieu to the inner mitochondrial membrane is an energy-dependent process that requires highly active mitochondria (23). Mitochondrial matrix citrate synthase activity and mtDNA copy number, used as markers of mitochondria biogenesis, were similar in both groups, suggesting that mitochondrial density was not impaired in obesity. However, obesity induced a down-regulation of the mitochondrial cholesterol transporter TSPO expression at the transcriptional and protein level. TSPO is a protein located on the outer mitochondrial membrane that exhibits a high affinity for cholesterol binding (10). Changes in TSPO expression levels have been observed in a variety of metabolic pathologies and cancers (11). There is a positive association between TSPO, tumor growth, and cell proliferation (24). A role for TSPO has been documented in several key mitochondrial functions, ie, interaction with the mitochondrial player VDAC, mitochondrial energy production, calcium signaling, and the generation of reactive oxygen species (25).

Our findings that decreased TSPO translates into decreased sex steroid synthesis point to a role for TSPO in controlling placenta endocrine function. Mitochondrial abnormalities have been reported in diabetes and metabolic conditions associated with insulin resistance (13). In the placenta, mitochondrial dysfunction with excess production of reactive oxygen species has been reported in obesity (26). The specificity of the obesity-induced mitochondrial alteration was further supported by our observation that the expression of the two placental cytosolic enzymes 17β-HSD1, critical for estradiol formation from estrone, and 3β-HSD1, which catalyzes the conversion of pregnenolone into progesterone, was unchanged in the placenta of obese women.

The down-regulation of placental TSPO is in agreement with a reduction of TSPO in white and brown adipose tissue in obesity (12). However, the mechanisms of TSPO gene regulation remain to be fully understood. A binding element to estradiol in TSPO promoter suggests a negative feedback loop between low estradiol concentration and low TSPO expression (27). Our in vitro results support an effect of bacterial endotoxin LPS as a potential inhibitor of TSPO gene expression. This is in line with mitochondrial steroidogenesis being inhibited by LPS in Leydig cells (19). The ability of long-chain saturated fatty acids to inhibit TSPO expression in cultured trophoblast cells is a novel finding (Figure 5). The transcriptional factor peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ, which is readily expressed on placental cells (28) and activated by palmitate (29), is a potential player in the inhibition of TSPO. This would be in line with the inhibition of TSPO mRNA levels by peroxisome proliferators decrease (30). We have shown that long-chain saturated fatty acids are powerful activators of TLR4 signaling in human placenta cells (Yang X., and S. Hauguel-de Mouzon, personal communication). Progesterone has been implicated to have a functional role in immune response to maintain pregnancy through the regulation of innate immunity. For example, progesterone can inhibit TLR4 expression and nuclear factor-κB activation (31). Taken together, these data suggest that the regulation of TSPO may be multifactorial.

In humans, 17-β-estradiol is the most potent biological estrogen (32). At physiological concentrations, 17-β-estradiol favors insulin sensitivity, whereas deficiency and/or resistance to estradiol provoke insulin resistance. One evidence is that men with estrogen receptor-α deficiency develop insulin resistance and/or glucose intolerance (33). Accordingly, treatment with 17-β-estradiol improves insulin resistance in female mice fed a high-fat diet (34). There is also evidence that estradiol regulates glucose homeostasis through glucose transporter-4 in skeletal muscle and white adipose tissue (35). In our study cohort, the obese women had a homeostasis model assessment resistance index 2-fold higher than in lean (Table 1), suggesting that estradiol deficiency may contribute to higher insulin resistance in obese women.

The required progesterone withdrawal at the time of human parturition is not mediated by changes in circulating progesterone levels (36), suggesting that in obesity, progesterone deficiency may not compromise the initiation of labor. On the other hand, there is substantial evidence to indicate that women with idiopathic recurrent miscarriage may benefit from the immunomodulatory properties of progesterone in early pregnancy (37). Misregulation of the progesterone production in Cyp11a1 transgenic mice results in aberrant implantation, anomalous placentation, and delayed parturition as a result of decreased cholesterol availability (38). It has been demonstrated that progesterone has immune suppressive properties and can inhibit a TLR4-triggered immune response (39). Taken together, these data suggest that progesterone deficiency may contribute to activate innate immunity and inflammatory pathways in the placenta of obese women (40).

Conclusion

Our study points to a key role of the cholesterol transporter TSPO to decrease mitochondrial cholesterol content in the placenta of obese women. This represents a critical alteration of mitochondrial function, which results in placental endocrine deficiency with a decreased synthesis of both progesterone and estradiol. As a whole, the impairment of sex steroids balance in obese women may compromise gestational homeostasis as well as the proper development of the fetoplacental unit.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr C. Hoppel and his group for his helpful contribution to mitochondrial assays. We also thank Joanna Zhou for her valuable contribution with the mitochondrial DNA analysis.

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant HD 22965-19 (to P.C.).

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

Footnotes

- BMI

- body mass index

- cytB

- cytochrome B

- FBS

- fetal bovine serum

- HSD

- hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase

- LPS

- lipopolysaccharide

- MLN64

- metastatic lymph node protein 64

- MSM

- D-mannitol, sucrose, and 3[N-morholino]propanesulfonic acid

- mt

- mitochondrial

- StAR

- steroidogenic acute regulatory protein

- TLR4

- Toll-like receptor 4

- TSPO

- translocator protein

- VDAC

- voltage-dependent anion channel.

References

- 1. Mesiano S. Myometrial progesterone responsiveness and the control of human parturition. J Soc Gynecol Investig. 2004;11(4):193–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Challis JRG, Matthews SG, Gibb W, Lye SJ. Endocrine and paracrine regulation of birth at term and preterm. Endocr Rev. 2000;21(5):514–550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tuckey RC. Progesterone synthesis by the human placenta. Placenta. 2005;26(4):273–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Xu XF, Bjorntorp P. The effects of steroid hormones on adipocyte development. Int J Obes. 1990;14(suppl 3):159–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Pedersen SB, Kristensen K, Hermann PA, Katzenellenbogen JA, Richelsen B. Estrogen controls lipolysis by up-regulating α2A-adrenergic receptors directly in human adipose tissue through the estrogen receptor α. Implications for the female fat distribution. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2004;89(4):1869–1878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lizcano F, Guzman G. Estrogen deficiency and the origin of obesity during menopause. BioMed Res Int. 2014;2014:757461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Clegg DJ. Minireview: the year in review of estrogen regulation of metabolism. Mol Endocrinol. 2012;26(12):1957–1960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Mauvais-Jarvis F. Estrogen and androgen receptors: regulators of fuel homeostasis and emerging targets for diabetes and obesity. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2011;22(1):24–33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Moog-Lutz C, Tomasetto C, Regnier CH, et al. MLN64 exhibits homology with the steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (STAR) and is over-expressed in human breast carcinomas. Int J Cancer. 1997;71(2):183–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Papadopoulos V, Baraldi M, Guilarte TR, et al. Translocator protein (18 kDa): new nomenclature for the peripheral-type benzodiazepine receptor based on its structure and molecular function. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2006;27(8):402–409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Batarseh A, Papadopoulos V. Regulation of translocator protein 18 kDa (TSPO) expression in health and disease states. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2010;327(1–2):1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Thompson MM, Manning HC, Ellacott KL. Translocator protein 18 kDa (TSPO) is regulated in white and brown adipose tissue by obesity. PloS One. 2013;8(11):e79980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sivitz WI, Yorek MA. Mitochondrial dysfunction in diabetes: from molecular mechanisms to functional significance and therapeutic opportunities. Antiox Redox Signal. 2010;12(4):537–577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Catalano PM, Thomas AJ, Avallone DA, Amini SB. Anthropometric estimation of neonatal body composition. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995;173(4):1176–1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Kliman HJ, Nestler JE, Sermasi E, Sanger JM, Strauss JF., 3rd Purification, characterization, and in vitro differentiation of cytotrophoblasts from human term placentae. Endocrinology. 1986;118(4):1567–1582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Matsuoka Y, Srere PA. Kinetic studies of citrate synthase from rat kidney and rat brain. J Biol Chem. 1973;248(23):8022–8030. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Liapis A, Chen FW, Davies JP, Wang R, Ioannou YA. MLN64 transport to the late endosome is regulated by binding to 14–3-3 via a non-canonical binding site. PloS One. 2012;7(4):e34424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fan J, Lindemann P, Feuilloley MG, Papadopoulos V. Structural and functional evolution of the translocator protein (18 kDa). Curr Mol Med. 2012;12(4):369–386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Allen JA, Diemer T, Janus P, Hales KH, Hales DB. Bacterial endotoxin lipopolysaccharide and reactive oxygen species inhibit Leydig cell steroidogenesis via perturbation of mitochondria. Endocrine. 2004;25(3):265–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Basu S, Haghiac M, Surace P, et al. Pregravid obesity associates with increased maternal endotoxemia and metabolic inflammation. Obesity (Silver Spring, Md). 2011;19(3):476–482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Blanchette S, Marceau P, Biron S, Brochu G, Tchernof A. Circulating progesterone and obesity in men. Horm Metab Res. 2006;38(5):330–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pasqualini JR. Enzymes involved in the formation and transformation of steroid hormones in the fetal and placental compartments. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2005;97(5):401–415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Allen AM, Taylor JM, Graham A. Mitochondrial (dys)function and regulation of macrophage cholesterol efflux. Clin Sci (London, England). 2013;124(8):509–515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Shoukrun R, Veenman L, Shandalov Y, et al. The 18-kDa translocator protein, formerly known as the peripheral-type benzodiazepine receptor, confers proapoptotic and antineoplastic effects in a human colorectal cancer cell line. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 2008;18(11):977–988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gatliff J, Campanella M. The 18 kDa translocator protein (TSPO): a new perspective in mitochondrial biology. Curr Mol Med. 2012;12(4):356–368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Roberts VH, Smith J, McLea SA, Heizer AB, Richardson JL, Myatt L. Effect of increasing maternal body mass index on oxidative and nitrative stress in the human placenta. Placenta. 2009;30(2):169–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Veenman L, Gavish M. The role of 18 kDa mitochondrial translocator protein (TSPO) in programmed cell death, and effects of steroids on TSPO expression. Curr Mol Med. 2012;12(4):398–412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Barak Y, Nelson MC, Ong ES, et al. PPAR γ is required for placental, cardiac, and adipose tissue development. Mol Cell. 1999;4(4):585–595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Coll T, Jove M, Rodriguez-Calvo R, et al. Palmitate-mediated downregulation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ coactivator 1α in skeletal muscle cells involves MEK1/2 and nuclear factor-κB activation. Diabetes. 2006;55(10):2779–2787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gazouli M, Yao ZX, Boujrad N, Corton JC, Culty M, Papadopoulos V. Effect of peroxisome proliferators on Leydig cell peripheral-type benzodiazepine receptor gene expression, hormone-stimulated cholesterol transport, and steroidogenesis: role of the peroxisome proliferator-activator receptor α. Endocrinology. 2002;143(7):2571–2583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Flores-Espinosa P, Pineda-Torres M, Vega-Sanchez R, et al. Progesterone elicits an inhibitory effect upon LPS-induced innate immune response in pre-labor human amniotic epithelium. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2014;71(1):61–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pepe G, Albrecht E. Glob. libr. women's med., (ISSN: 1756-2228) 2008; DOI 10.3843/GLOWM.10. Available at: http://www.glowm.com/section_view/item/310.

- 33. Morishima A, Grumbach MM, Simpson ER, Fisher C, Qin K. Aromatase deficiency in male and female siblings caused by a novel mutation and the physiological role of estrogens. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1995;80(12):3689–3698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Riant E, Waget A, Cogo H, Arnal JF, Burcelin R, Gourdy P. Estrogens protect against high-fat diet-induced insulin resistance and glucose intolerance in mice. Endocrinology. 2009;150(5):2109–2117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Barros RP, Gabbi C, Morani A, Warner M, Gustafsson JA. Participation of ERα and ERβ in glucose homeostasis in skeletal muscle and white adipose tissue. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2009;297(1):E124–E133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mesiano S, Chan EC, Fitter JT, Kwek K, Yeo G, Smith R. Progesterone withdrawal and estrogen activation in human parturition are coordinated by progesterone receptor A expression in the myometrium. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87(6):2924–2930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Di Renzo GC, Giardina I, Clerici G, Mattei A, Alajmi AH, Gerli S. The role of progesterone in maternal and fetal medicine. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2012;28(11):925–932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Chien Y, Cheng WC, Wu MR, Jiang ST, Shen CK, Chung BC. Misregulated progesterone secretion and impaired pregnancy in Cyp11a1 transgenic mice. Biol Reprod. 2013;89(4):91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Su L, Sun Y, Ma F, Lu P, Huang H, Zhou J. Progesterone inhibits Toll-like receptor 4-mediated innate immune response in macrophages by suppressing NF-κB activation and enhancing SOCS1 expression. Immunol Lett. 2009;125(2):151–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Challier JC, Basu S, Bintein T, et al. Obesity in pregnancy stimulates macrophage accumulation and inflammation in the placenta. Placenta. 2008;29(3):274–281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]