Abstract

Aims: Myocardial infarction (MI) is a leading cause of death globally. MicroRNAs (miRNAs) have been identified as a novel class of MI injury regulators. Hydrogen sulfide (H2S) is a gaseous signaling molecule that regulates cardiovascular function. The purpose of this study was to explore the role of the miR-30 family in protecting against MI injury by regulating H2S production. Results: The expression of miR-30 family was upregulated in the murine MI model as well as in the primary cardiomyocyte hypoxic model. However, the cystathionine-γ-lyase (CSE) expression was significantly decreased. The overexpression of miR-30 family decreased CSE expression, reduced H2S production, and then aggravated hypoxic cardiomyocyte injury. In contrast, silencing the whole miR-30 family can protect against hypoxic cell injury by elevating CSE and H2S level. Nonetheless, the protective effect was abolished by cotransfecting with CSE-siRNA. Systemic delivery of a locked nucleic acid (LNA)-miR-30 family inhibitor correspondingly increased CSE and H2S level, then reduced infarct size, decreased apoptotic cell number in the peri-infarct region, and improved cardiac function in response to MI. However, these cardioprotective effects were absent in CSE knockout mice. MiR-30b overexpression in vivo aggravated MI injury because of H2S reduction, and this could be rescued by S-propargyl-cysteine (SPRC), which is a novel modulator of CSE, or further exacerbated by propargylglycine (PAG), which is a selective inhibitor of CSE. Innovation and Conclusion: Our findings reveal a novel molecular mechanism for endogenous H2S production in the heart at the miRNA level and demonstrate the therapeutic potential of miR-30 family inhibition for ischemic heart diseases by increasing H2S production. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 22, 224–240.

Introduction

Acute myocardial infarction (MI), which is typically a consequence of coronary artery occlusion, is characterized by a loss of viable cardiac tissue. MIs are followed by interstitial fibrosis and hypertrophy of the nonischemic myocardium, which further deteriorates pump function and induces arrhythmias and sudden death (45). MI is currently one of the leading causes of morbidity and mortality globally, because there are no clinically applicable drugs that effectively treat myocardial ischemic injury (12).

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are endogenous small noncoding RNA acting as negative regulators of gene expression by mRNA degradation or translational repression (1, 8). Growing evidence shows that miRNAs are extensively involved in the pathogenesis of heart diseases (15), including cardiac hypertrophy (30), cardiac fibrosis (36), arrhythmia (43), heart failure (33), and MI (16, 27). The miR-30 family, including miR-30a, miR-30b, miR-30c, miR-30d, and miR-30e, has been shown to alter cell proliferation, differentiation (37), migration, and invasion (6) in various carcinomas. The details of miR-30 involvement in cardiovascular pathophysiology have recently emerged. A study has shown that downregulated miR-30a aggravates angiotensin II-induced myocardial hypertrophy by targeting beclin-1 (26). Wei et al. (42) recently demonstrated that NF-κB positively regulated miR-30b expression in Ang II-induced cardiomyocytes apoptosis, and Bcl-2 was a direct target for miR-30b. Duisters et al. (13) showed that miR-30c is predominantly expressed in fibroblasts and that it can regulate connective tissue growth factors in myocardial matrix remodeling. MiR-30c and miR-30d overexpression has also been proved to induce cardiomyocyte hypertrophy (20). Studies also showed that miR-30 family plays an important role during sprouting angiogenesis by targeted delta-like 4 (DLL4) (3). Furthermore, the upregulation of circulating miR-30a may be used as a potential biomarker for acute myocardial infarction (AMI) (23). Dong et al. (11) also studied AMI and observed that miR-30b-5p and miR-30c expressions were upregulated in the noninfarcted areas of the infarcted heart. These results suggest that miR-30 may be a new pathological factor and therapeutic target for cardiovascular diseases.

Innovation.

We demonstrated for the first time that the miR-30 family was able to regulate hydrogen sulfide (H2S) production in the heart by directly targeting cystathionine-γ-lyase (CSE). This revealed a new molecular control mechanism for endogenous H2S production in the heart at the microRNA level. We also found that miR-30–CSE–H2S axis contributes to protection against cardiomyocyte ischemic injury both in vitro and in vivo by regulating H2S production. This may provide a new potential therapeutic target for ischemic heart disease.

Hydrogen sulfide (H2S), which is the third gaseous mediator alongside carbon monoxide (CO) and nitric oxide (NO) in mammals, has been reported to provide cardioprotection in various models of cardiac injury, including MI (28). Physiologically, H2S is generated from L-cysteine and catalyzed by cystathionine-β-synthase, cystathionine-γ-lyase (CSE), or 3-mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase (32, 40). CSE is the predominant H2S-generating enzyme in the cardiovascular system (25).

A growing body of evidence shows that H2S derived from CSE modulates cardioprotection in myocardial ischemic injury. Transgenic mice with cardiac-restricted overexpression of CSE result in increased H2S production and cardioprotection in response to both acute myocardial ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury (14) and ischemia-induced heart failure (5). In contrast, deficiency of CSE significantly attenuates H2S and results in exacerbating myocardial I/R injury (4). Moreover, our previous studies (38, 39, 46) have shown that CSE expression in the rat heart is significantly reduced at 48 h after MI induction. Qipshidze et al. (28) also found that induction of MI for 4 weeks decreases expression of CSE in mice heart. These findings indicate that lower endogenous levels of H2S that are attributable to the suppression of CSE expression are pathogenic in cardiac ischemic injury. However, the mechanisms for the alterations in CSE expression in these pathological conditions remain unclear. In addition, the molecular mechanism for the regulation of endogenous H2S production in the heart is not yet known.

In this study, we provide a better understanding of the relationship between miR-30 family and H2S production and reveal the mechanism for endogenous H2S production at miRNA level. Furthermore, we clarify the protective effect of miR-30 family inhibition on myocardial ischemic injury by regulating the production of H2S both in vitro and in vivo.

Results

The expressions of CSE and miR-30 family are changed in response to MI

To explore whether miRNAs regulated CSE, we first undertook a bioinformatic approach with targetscan software (www.targetscan.org) and observed that the miR-30 family, including miR-30a, miR-30b, miR-30c, miR-30d, and miR-30e, could potentially target CSE mRNA. The 3′-untranslated region (UTR) of the CSE mRNA contains one binding site for all miR-30 family members among humans, rats, and mice (Fig. 1A).

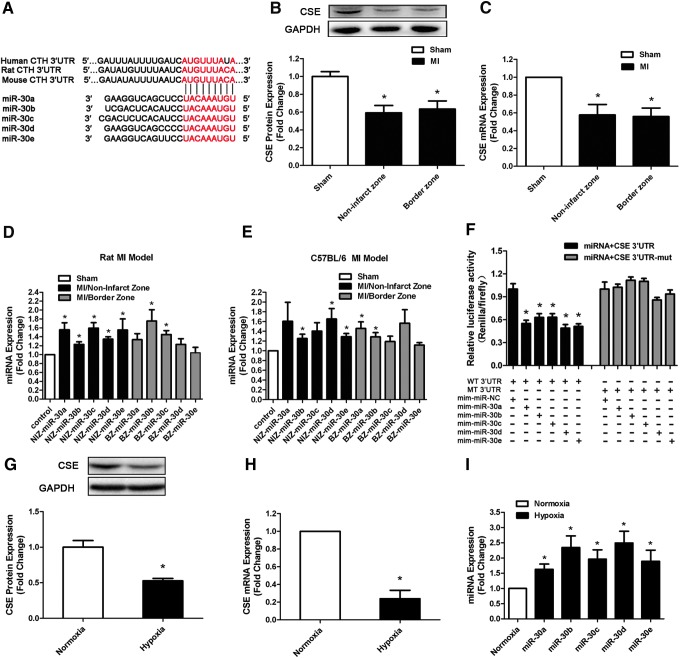

FIG. 1.

CSE is a direct target of miR-30 family. (A) Sequence alignment between the miR-30 family members and the 3′-UTRs of CSE of human, rat, and mouse. The sequences in CSE genes complementary to the miR-30 family seed regions are shown in red. (B) CSE protein and (C) mRNA expression levels in the border and noninfarct zones of all MI rats compared with sham-operated rats at 48 h after MI induction (n=6). (D, E) Real-time polymerase chain reaction shows the aberrant expression of the miR-30 family in different regions of the rat MI model (D) and C57BL/6 mouse MI model (E) compared with sham-operated heart (n=6). (F) Dual-luciferase reporter activities show the interaction between miR-30 family members and CSE 3′-UTRs (n=6). (G) CSE protein, (H) CSE mRNA, and (I) miR-30 family expression levels at 8 h after hypoxia in hypoxic cardiomyocyte model compared with normoxia cell (n=5–6). The data are expressed as mean±standard error of the mean (SEM). *p<0.05 versus sham group or normoxia group. CSE, cystathionine-γ-lyase; MI, myocardial infarction; UTR, untranslated region. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars

Then, we examined CSE expression in different heart regions in a rat MI model at 48 h after MI induction. Real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and Western blot revealed that CSE levels decreased in the remote and border zone regions after MI compared with control tissue from sham-operated animals (Fig. 1B, C). However, all members of the miR-30 family were observed to be upregulated in these two regions of both rat and mouse MI models (Fig. 1D, E). Furthermore, in hypoxic myocardial cell model, we also found that CSE expression was decreased (Fig. 1G, H) and miR-30 family was increased (Fig. 1I) when compared with normoxia group. These results indicated a correlation between increased miR-30 levels and the decrease in CSE expression.

CSE is a direct target of the miR-30 family

To further validate that the miR-30 family is able to directly bind to CSE and inhibit CSE expression, we inserted the full-length 3′-UTR of the CSE transcript into a dual-luciferase expression plasmid (pMir-report) and cotransfected them into HEK293 cells with miR-30 family member mimics or negative control (NC) miRNA. As expected, the cotransfection of miR-30 family members with the reporter construct containing the 3′-UTR segment of the CSE resulted in a significant decrease in luciferase activity, but this was not observed with control miRNA. No effects were observed with a construct containing a mutated segment of the CSE 3′-UTR (seed sequence TGTTTACA was mutated to AGATAAGT) (Fig. 1F). This indicated that CSE transcripts represented a genuine target of the miR-30 family.

MiR-30 family regulates CSE mRNA and protein levels

To determine the role of the miR-30 family in CSE regulation, gain-of-function and loss-of-function approaches were performed in primary neonatal rat myocardial cells. First of all, we transfected cultured myocardial cells with miR-30 family member mimics (50 nM) or an NC miRNA. Forty-eight hours after transfection, we observed a significant negative correlation between all of the miR-30 family member mimics and CSE expression in primary cardiomyocytes. The real-time PCR and Western blot results showed that the overexpression of each miR-30 family member clearly decreased the CSE expression at both the mRNA and protein levels (Fig. 2A, B).

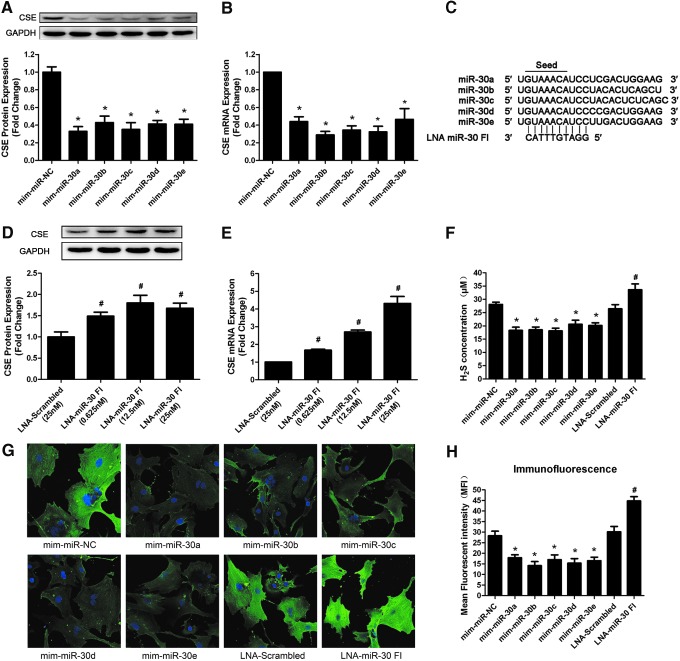

FIG. 2.

Effects of the miR-30 family member mimics and miR-30 family inhibitor (FI) on CSE expression. (A) CSE protein and (B) mRNA expression levels in primary neonatal rat myocardial cells after transfecting with the miR-30 family member mimics for 48 h (n=5). (C) The design of locked nucleic acid (LNA)-miR-30 FI. The miR-30 family FI had a 10-mer LNA-anti-miR that was complementary to the seed region of each miR-30 family member. (D) CSE protein and (E) mRNA levels after transfecting with the LNA-miR-30 FI for 48 h (n=6). (F) The change in the hydrogen sulfide (H2S) concentration in the supernatant after transfecting miR-30 family mimics (50 nM) or the LNA-miR-30 FI (12.5 nM) for 48 h (n=5). (G) Representative immunofluorescent images show the CSE expression levels in primary cardiomyocytes. Green: CSE protein that was stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate, Blue: Cell nucleus stained with DAPI. (H) Quantitative analysis of the mean fluorescence intensity in each group (n=6). The data are expressed as mean±SEM. *p<0.05 versus mim-miR-NC group, #p<0.05 versus LNA-Scrambled group. Magnification ×400. DAPI, 4,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole; NC, negative control. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars

Subsequently, we tested whether knockdown of the whole miR-30 family induced an upregulation of CSE levels. Therefore, we designed a 10-mer locked nucleic acid (LNA)-miR-30 family inhibitor (LNA-miR-30 FI) that was complementary to the seed region of the miR-30 family, as described by Obad et al. (24), which was predicted to target all miR-30 family members (Fig. 2C). The successful knockdown of miR-30 family members was confirmed by real-time PCR. At 25 nM, the LNA-miR-30 FI reduced the expression of the miR-30 family members by ∼70% compared with that in LNA-scrambled control-transfected cells (Supplementary Fig. S1; Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertpub.com/ars), whereas the expression levels of CSE mRNA and protein significantly increased in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2D, E). This experiment demonstrated that specific knockdown of the whole miR-30 family robustly induced the expression levels of CSE mRNA and protein.

The effects of miR-30 mimics and miR-30 FI were also confirmed by immunohistochemistry. As shown in Figure 2G and H, transfection of miR-30 family member mimics resulted in weaker green fluorescence intensity compared with the NC group. However, the green fluorescence intensity in the LNA-miR-30 FI group was stronger than in the LNA-scrambled group.

The H2S concentration in the supernatant after transfection was also determined. It was found that miR-30 family mimics reduced H2S production, whereas LNA-miR-30 FI increased H2S level at 48 h after transfection (Fig. 2F).

The miR-30 family affects hypoxia-induced cardiomyocyte injury

CSE is the main enzyme and plays a major role in catalyzing the production of H2S in the cardiovascular system. We aimed at determining the effects of the miR-30 family on cardiomyocytes under hypoxia condition by regulating CSE expression. Eight hours of hypoxia, the cell viability decreased 35.85%±5.75%, and the lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release significantly increased 86.61%±19.55% when compared with normoxic group (Fig. 3A, B), indicating that the hypoxic conditions were sufficient to induce cardiomyocyte injury in vitro.

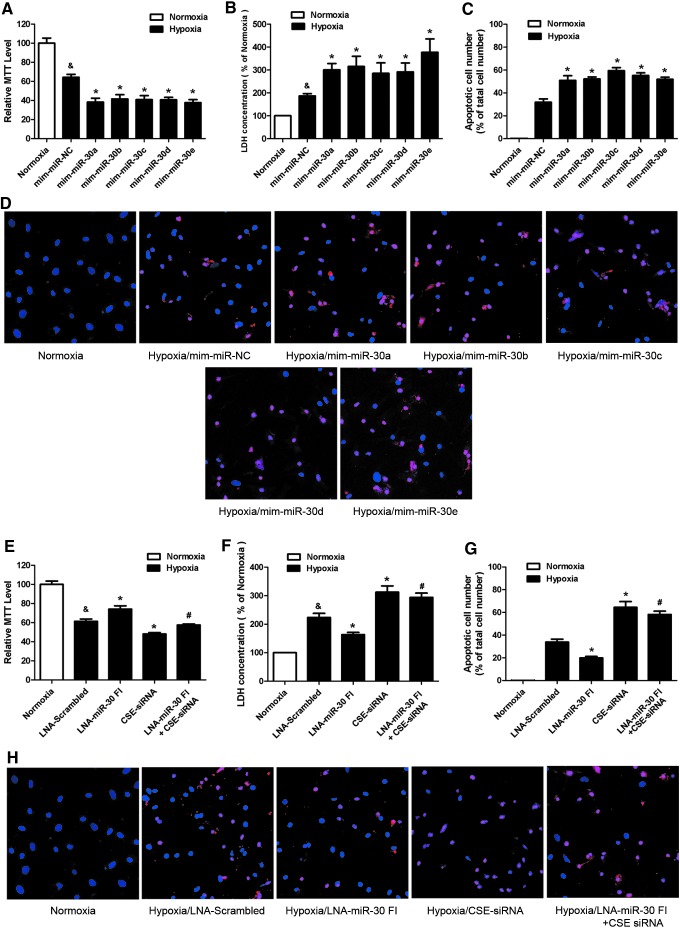

FIG. 3.

The miR-30 family affected hypoxia-induced cardiomyocyte injury. (A) Effects of the miR-30 family mimics on the viability of primary neonatal rat cardiomyocyte subjected to 8 h of hypoxia (n=5). (B) Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release in the supernatant at 8 h after hypoxia (n=5). (C) The apoptotic cell number (%) is represented as a ratio of the number of apoptotic cells to the total cell number (n=5). (D) Representative TUNEL-stained photomicrographs from cells after 8 h of hypoxia. Red color is TUNEL staining representing apoptotic cell; Blue color is the cell nucleus stained by DAPI. (E) Cell viability, (F) LDH release, and (G, H) apoptotic cells' number subjected to 8 h of hypoxia after transfecting with LNA-miR-30 FI and/or CSE-siRNA (n=5–6). The data are expressed as the mean±SEM, *p<0.05 versus mim-miR-NC group or LNA-Scrambled group, #p<0.05 versus LNA-miR-30 FI group, &p<0.05 versus normoxia group. Magnification ×200. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars

Subsequently, using this hypoxic model, we confirmed that upregulation of CSE by an overexpression plasmid (pcDNA3.1-CSE) markedly increased the CSE and H2S level and protected cardiomyocyte against hypoxia injury, determined by 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2, 5-diphenyltetra-zolium (MTT) and LDH assay (Supplementary Fig. S2). On the other hand, blockade of CSE with siRNA significantly reduced the CSE and H2S level and aggravated hypoxia cardiomyocyte injury (Supplementary Fig. S2). In miR-30 transfection groups, we found that the overexpression of each miR-30 family member decreased cell viability and increased LDH release when compared with NC under hypoxic conditions (Fig. 3A, B). On the other hand, the knockdown of the whole miR-30 family with the LNA-miR-30 FI increased cell viability and reduced LDH release (Fig. 3E, F). However, this protective effect was absent after cotransfecting LNA-miR-30 FI with CSE siRNA (Fig. 3E, F).

We also used a TUNEL assay to determine the effects of the miR-30 family in hypoxia-induced apoptosis. The results showed that the number of apoptotic cells significantly increased after transfecting miR-30 family mimics (Fig. 3C, D), but reduced after transfecting the miR-30 FI (Fig. 3G, H) when compared with NC. Nevertheless, the apoptotic cells' number was increased again after cotransfecting miR-30 FI with CSE siRNA (Fig. 3G, H).

Taken together, these data showed that miR-30 overexpression aggravated cardiomyocyte injury during hypoxia and that the LNA-miR-30 FI protected cardiomyocytes against hypoxia-induced injury. Notably, CSE-siRNA abolished the protective effect of LNA-miR-30 FI.

Silencing the miR-30 family protects against MI injury in mice

To investigate whether the beneficial effects existed in in vivo conditions, we knocked down the miR-30 family with a tail vein injection of LNA-miR-30 FI. Scrambled oligo and saline were used as controls. With an LNA-miR-30 FI injection (5 mg/kg) for 3 successive days, real-time PCR analysis revealed a dramatic reduction in miR-30 family expression levels in heart tissue compared with the LNA-scrambled control (Fig. 4A). This indicated that LNA-miR-30 FI efficiently downregulated miR-30 family expression levels in the heart. In parallel, the administration of the LNA-miR-30 FI and not the LNA-scrambled control was associated with greatly increased CSE expression levels in the left ventricle, and the data showed that LNA-miR-30 FI increased the CSE expression in a dose-dependent manner at both the mRNA and protein levels (Fig. 4B, C). In our experiment, 2.5 mg/kg of LNA-miR-30 FI showed the highest efficiency in increasing CSE protein expression in vivo, and was, therefore, chosen in subsequent experiments.

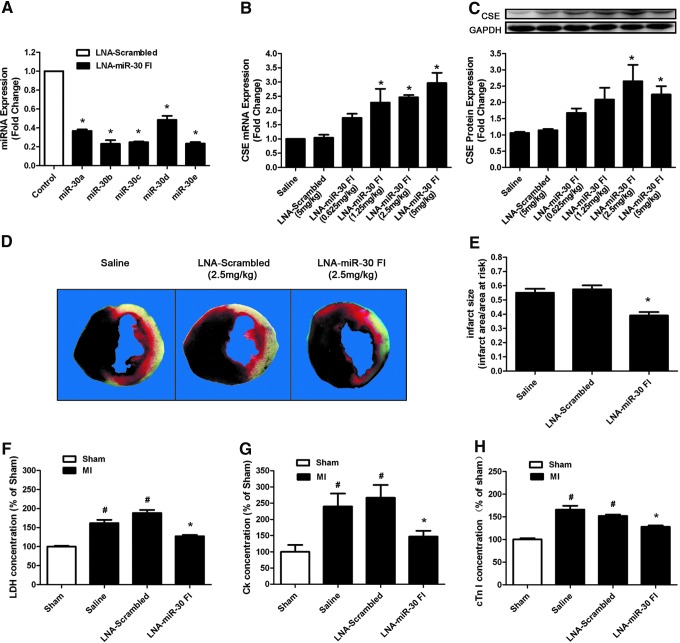

FIG. 4.

LNA-miR-30 FI protects the heart against MI injury in C57BL/6 mice. (A) The expression levels of miR-30 family members in C57BL/6 mouse heart after injecting 5 mg/kg of LNA-miR-30 FI for 3 consecutive days (n=3). (B) CSE mRNA and (C) protein expression levels in the C57BL/6 left ventricle after injecting different concentrations of LNA-miR-30 FI for 3 consecutive days (n=7). (D) Representative heart images that were stained by TTC and Evans blue, C57BL/6 mice were treated with LNA-miR-30 FI (2.5 mg/kg) for 3 consecutive days before MI surgery. The red region is the border zone that was stained by TTC, the white region is the infarct zone that cannot be stained by either TTC or Evans blue, and the black region is the normal tissue that is stained by both TTC and Evans blue. (E) The infarct size is expressed as the ratio of the infarct area and area at risk (n=6). (F–H) The effects of LNA-miR-30 FI on LDH, creatine kinase (CK), and cardiac troponin-I (cTn-I) release in plasma of mice MI model (n=6). The data are expressed as the mean±SEM. *p<0.05 versus LNA-scrambled group, #p<0.05 versus sham group. TTC, triphenyltetrazolium chloride. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars

Next, the hearts treated with LNA-miR-30 FI for 3 days were subjected to coronary occlusion to induce an MI model. The extent of MI was determined at 48 h after surgery, and the results indicated that treatment with LNA-miR-30 FI resulted in a significant decrease in infarct size compared with treatment with either saline or LNA-scrambled control (Fig. 4D, E). The area at risk (AAR) was nearly the same among groups (data not shown).

LDH, creatine kinase (CK), and cardiac troponin-I (cTn-I) are three reliable biomarkers of cardiomyocyte injury. To confirm the degree of cardiomyocyte injury in ischemia, we determined LDH, CK, and cTn-I concentrations in plasma. Consistent with the results of cardiac infarct size, our data showed that LDH, CK, and cTn-I concentrations in plasma were markedly increased in the MI group compared with the sham group, whereas the knockdown of the miR-30 family by LNA-miR-30 FI inhibited the increases in serum LDH, CK, and cTn-I levels that were caused by MI injury (Fig. 4F–H).

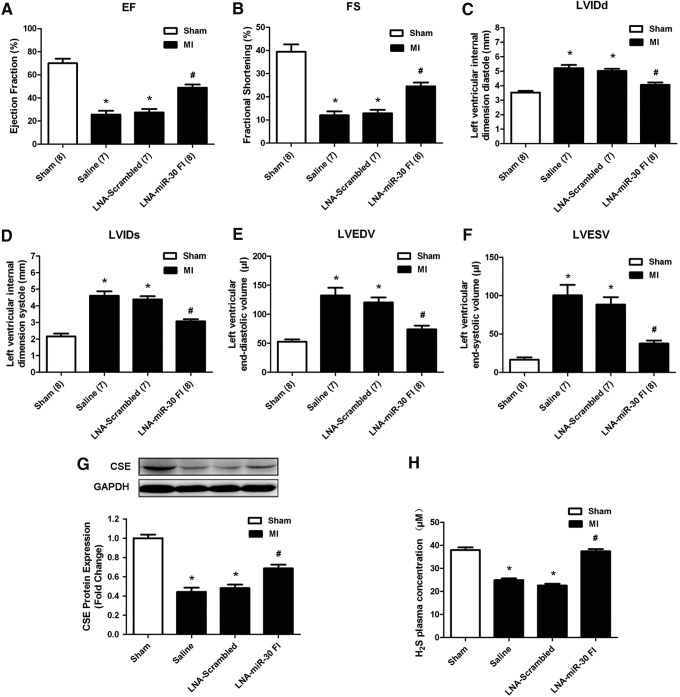

Cardiac function was examined using echocardiography at 5 days after MI surgery. The echocardiography revealed that the left ventricular ejection fraction (EF) and fractional shortening (FS) were significantly decreased (Fig. 5A, B), whereas the left ventricular internal dimension systole (LVIDs), left ventricular internal dimension diastole (LVIDd), left ventricular end-systolic volume (LVESV), and left ventricular end-diastolic volume (LVEDV) were increased in the MI models (Fig. 5C–F), indicating impaired cardiac function. The downregulation of the miR-30 family attenuated the deterioration in left ventricular performance, as indicated by the increased EF and FS, which corresponded with the decreased LVIDd, LVIDs, LVEDV, and LVESV. In contrast, the LNA-scrambled control and vehicle control produced no such effects. The improvement in ischemia injury was in parallel with the increase in CSE expression and H2S concentration in response to LNA-miR-30 FI at 48 h after injury (Fig. 5G, H).

FIG. 5.

LNA-miR-30 FI improved the impaired cardiac function of mice after MI surgery. (A–F) The echocardiography data show the changes in the ejection fraction (EF), and fractional shortening (FS), left ventricular internal dimension diastole (LVIDd), left ventricular internal dimension systole (LVIDs), left ventricular end-diastolic volume (LVEDV), and left ventricular end-systolic volume (LVESV) at 5 days after MI surgery (n=7–8). (G) CSE protein expression levels in the left ventricle and (H) H2S concentration in the plasma of the different MI group (n=5). C57BL/6 mice were treated with LNA-miR-30 FI (2.5 mg/kg) for 3 consecutive days before MI surgery. The data are expressed as the mean±SEM. n=7–8, *p<0.05 versus sham group, #p<0.05 versus LNA-Scrambled group.

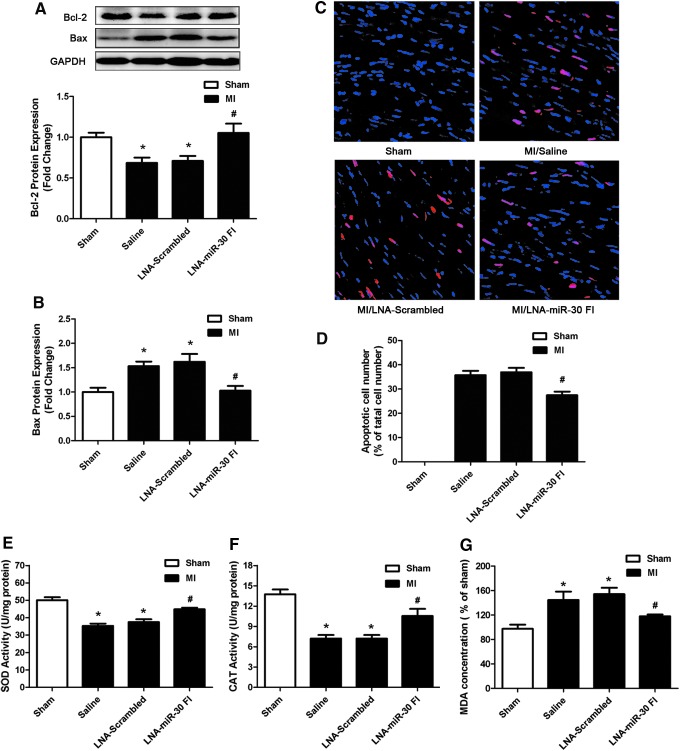

We also examined the effects of LNA-miR-30 FI on Bcl-2 and Bax expression in the left ventricle of the ischemic heart. We observed that downregulation of the whole miR-30 family enhanced Bcl-2 levels and reduced Bax levels after MI injury (Fig. 6A, B). We further examined apoptosis of cardiomyocytes that were subjected to ischemia injury by TUNEL staining in the peri-infarct area of the infarcted heart. Compared with the saline control, LNA-miR-30 FI markedly decreased the apoptosis of cardiomyocytes, while the LNA-scrambled control produced no effects (Fig. 6C, D). In addition, we also found the activities of antioxidant defensive enzymes such as superoxide dismutase (SOD) and catalase (CAT) were decreased in left ventricular tissue of MI control group, but increased after using LNA-miR-30 FI (Fig. 6E, F). An additional biomarker of oxidative stress named malonaldehyde (MDA) was increased in the MI control group, but reduced after treatment with LNA-miR-30 FI (Fig. 6G).

FIG. 6.

LNA-miR-30 FI protects the heart against MI injury by anti-apoptosis and anti-oxidation. (A) Bcl-2 and (B) Bax expression in the left ventricle of different MI group (n=6). (C) Representative TUNEL-stained photomicrographs from cardiomyocytes in the peri-infarct area of the infarcted heart, Red: TUNEL staining representing apoptotic cell; Blue: Cell nucleus stained by DAPI. (D) The apoptotic cell number (%) is represented as a ratio of the number of apoptotic cells to the total cell number (n=6). (E–G) Activities of superoxide dismutase (SOD) and catalase (CAT), and concentration of malonaldehyde (MDA) in left ventricular tissue of different MI groups (n=6). The data are expressed as the mean±SEM. *p<0.05 versus sham group, #p<0.05 versus LNA-Scrambled group. Magnification ×200. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars

Taken together, these data indicated that the systemically applied LNA-miR-30 FI reduced infarct size and improved cardiac function in response to ischemia injury. This corresponds with the increase in H2S production that occurred in response to miR-30 inhibition.

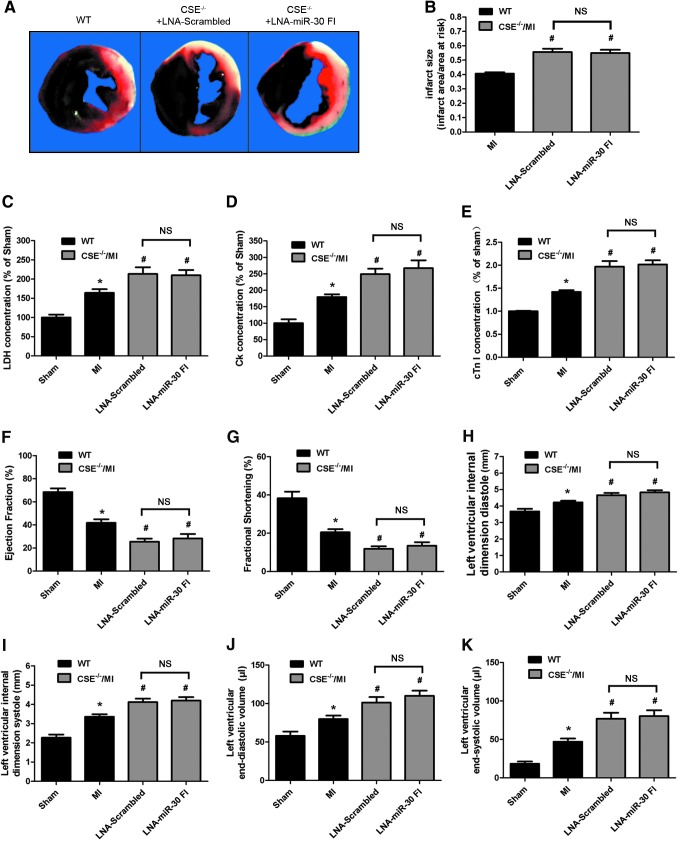

The cardioprotective effect of LNA-miR-30 FI was absent in CSE knockout mice

Furthermore, in order to ascertain whether the protective effect of LNA-miR-30 FI is, indeed, dependent on CSE, CSE knockout mice (CSE−/−) were used to check whether the protective effect is still present after administration of LNA-miR-30 FI. The results showed that CSE protein was absent in heart of CSE−/− mice, endogenous H2S levels in plasma were decreased by about 50% when compared with wild-type (WT) mice. However, there was no significant difference between CSE−/− mice and CSE−/− mice treated with LNA-miR-30 FI (Supplementary Fig. S3).

Deficiency of CSE exacerbates myocardial ischemia injury. Myocardial infarct size was significantly greater in CSE−/− mice MI model as compared with WT control hearts (Fig. 7A, B). In parallel, circulating plasma levels of the LDH, CK, and cTnI evaluated as an additional marker of myocardial injury were significantly increased in CSE−/− mice MI model (Fig. 7C–E). However, administration of LNA-miR-30 FI showed no improvement. There was no difference between CSE−/− mice group and CSE−/− mice administered with LNA-miR-30 FI group (Fig. 7 A–E).

FIG. 7.

The cardioprotective effect of LNA-miR-30 FI was absent in CSE knockout mice (A) Representative heart images that were stained by TTC and Evans blue. (B) The infarct size is expressed as the ratio of the infarct area and area at risk (n=6). (C–E) LDH, CK, and cTn-I release in plasma (n=6). (F–K) Echocardiography data show the changes in LVIDs, LVIDd, LVESV, LVEDV, EF, and FS at 5 days after MI surgery. CSE−/− mice were treated with LNA-miR-30 FI (2.5 mg/kg) for 3 consecutive days before MI surgery (n=8–10). *p<0.05 versus WT sham group, #p<0.05 versus WT MI group. NS, nonsignificant (p>0.05). WT, wild-type. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars

Moreover, LNA-miR-30 FI-treated CSE−/− mice displayed no significant increase in EF, FS as compared with LNA-scrambled treated CSE−/− mice, which displayed significantly decreased EF and FS after MI (Fig. 7F, G). These findings provide direct evidence that LNA-miR-30 FI plays its protective role by regulating the expression of CSE and the production of H2S.

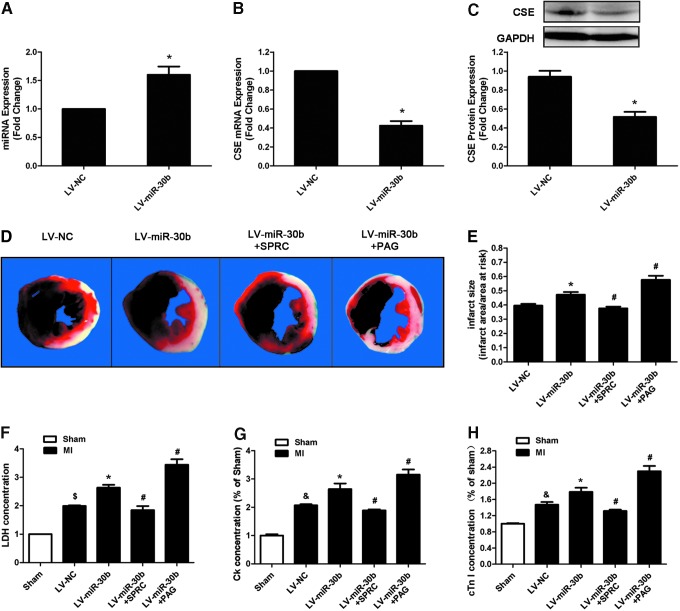

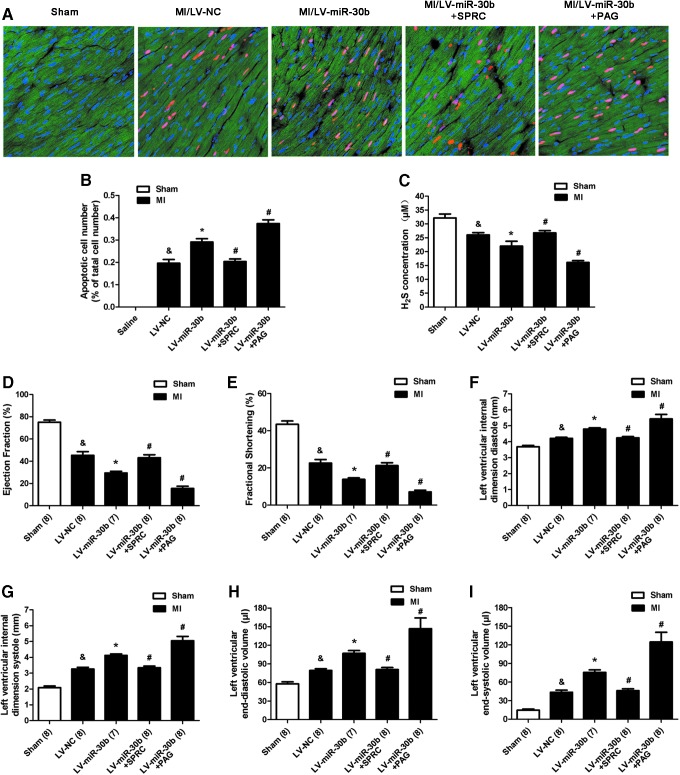

MiR-30b overexpression aggravates MI injury in mice

Since the change of miR-30b expression is the most obvious in both murine MI model and cardiomyocyte hypoxic model (Fig. 1D, E, I), we hypothesize that the increased miR-30b expression levels, occurring in response to ischemic injury, may have the most contribution in the MI model. Thus, to investigate the functional significance of miR-30b in ischemic heart, we tested whether miR-30b overexpression could exacerbate cardiac dysfunction by reducing H2S production. Furthermore, we used S-propargyl-cysteine (SPRC) and Propargylglycine (PAG) to confirm the possible role of CSE-mediated mechanism in the effect of miR-30b on ischemic injury. SPRC is a novel modulator of CSE that has been proved to be able to protect against myocardial ischemia by increasing CSE expression. PAG is an inhibitor that can reduce endogenous H2S production by inhibiting CSE (38, 39).

First, we verified that a single administration of SPRC could increase the expression of CSE and the level of H2S (Supplementary Fig. S4A, B) in plasma, and then protect the cardiac ischemia injury by reducing infarct size (Supplementary Fig. S4C, D) and improving heart function (Supplementary Fig. S5). However, administration of PAG alone could decrease the level of H2S in plasma and aggravate cardiac injury (Supplementary Figs S4 and S5).

Subsequently, we used lentivirus (LV) carrying the precursor of miR-30b to overexpress miR-30b in vivo, at 8 days after infection with 2.5×107 TU lentiviral particles; the expression of miR-30b was significantly increased (Fig. 8A). Correspondingly, CSE expression was decreased at both the mRNA and protein levels (Fig. 8B, C).

FIG. 8.

miR-30b overexpression aggravates MI injury in C57BL/6 mice. (A) miR-30b levels, (B) CSE mRNA and (C) protein levels in the left ventricle of C57BL/6 mice 8 days after injecting LV-miR-30b (n=3). (D) Representative heart images that were stained by TTC and Evans blue. (E) Infarct size that is expressed as a ratio of the infarct area and area at risk at 2 days after MI surgery (n=6). (F–H) LDH, CK, and cTn-I release in plasma of different MI groups treated with LV-miR-30b individually or plus SPRC and PAG (n=6). The data are expressed as mean±SEM. *p<0.05 versus LV-NC group, &p<0.05 versus sham group, #p<0.05 versus LV-miR-30b group. PAG, propargylglycine; SPRC, S-propargyl-cysteine. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars

Then, we used MI model combined with SPRC and PAG to investigate the effect and mechanism of LV-miR-30b on ischemia injury. Two days after MI induction, we observed that miR-30b overexpression increased the infarct area (Fig. 8D, E), the LDH, CK, and cTn-I concentrations (Fig. 8F–H), and also increased the apoptotic cardiomyocyte number in the peri-infarct area compared with the LV-NC group after MI (Fig. 9A, B). Treatment of LV-miR-30b plus SPRC abolished the negative effects of LV-miR-30b on augmentation of infarct size (Fig. 8D, E) and apoptotic cardiomyocyte number (Fig. 9A, B). However, treatment of LV-miR-30b plus PAG further increased infarct size (Fig. 8D, E) and apoptotic cell number (Fig. 9A, B). Moreover, miR-30b overexpression destroyed cardiac function (Fig. 9D–I). LV-miR-30b plus SPRC also rescued the cardiac damage caused by a single administration of LV-miR-30b, but LV-miR-30b plus PAG further exacerbated the cardiac damage (Fig. 9D–I). These results corresponded with the H2S concentration in plasma after administration with LV-miR-30b, SPRC, or PAG. As Shown in Figure 9C, LV-miR-30b decreased the H2S level, whereas administration of LV-miR-30b plus SPRC abrogated the negative effect of LV-miR-30b on H2S level. However, LV-miR-30b plus PAG further decreased the H2S concentration in plasma.

FIG. 9.

miR-30b overexpression aggravates the cardiac function of mice after MI surgery. (A) Representative TUNEL-stained photomicrographs from cardiomyocytes in peri-infarct area of infarcted heart at 2 days after MI surgery. Red color is TUNEL staining representing apoptotic cell; Blue color is the cell nucleus stained by DAPI; Green color shows the location of LV-GFP. (B) The apoptotic cell number (%) is represented as a ratio of the number of apoptotic cells to the total cell number (n=6). (C) H2S concentration in the plasma after administration of LV-miR-30b (2.5×107 TU), individually or plus SPRC and PAG (n=6). (D–I) Echocardiography data shows the changes in LVIDs, LVIDd, LVESV, LVEDV, EF, and FS at 5 days after MI surgery. C57BL/6 mice were treated with LV-miR-30b individually or plus SPRC and PAG (n=7–8). The data are expressed as mean±SEM. &p<0.05 versus sham group, *p<0.05 versus LV-NC group, #p<0.05 versus LV-miR-30b group. Magnification ×200. To see this illustration in color, the reader is referred to the web version of this article at www.liebertpub.com/ars

Discussion

Taken together, our results identified the miR-30 family as potentially important regulators of CSE gene expression. The overexpression of the miR-30 family members decreased CSE expression and H2S production and subsequently aggravated the hypoxia-induced cardiomyocyte injury in vitro. In contrast, downregulation of the entire miR-30 family increased CSE expression and H2S production and protected hypoxia injury in cardiomyocytes. In the in vivo study, we observed that the downregulation of the miR-30 family reduced the infarct size of the heart, which was subjected to coronary artery ligation, and improved the impaired cardiac function by increasing CSE expression and H2S production. The overexpression of miR-30b would aggravate MI injury because of H2S reduction. Our data demonstrated for the first time that the miR-30 family was able to regulate H2S production by directly targeting CSE. These findings revealed a new molecular control mechanism for endogenous H2S production in the heart at the miRNA level. Furthermore, the therapeutic potential of miR-30 family inhibition may open a new avenue for the treatment of ischemic heart diseases.

MiR-30 family members included miR-30a, −30b, −30c, −30d, and −30e, which are encoded by six genes located on human chromosomes 1, 6, and 8. All of them share a common 8-mer conserved seed sequence at their 5′ terminals, but the flanking sequences between the members are substantially different from each other. The miR-30 family is abundantly expressed in the heart under physiological conditions (19). The levels of redundancy suggest a critical functional role for this miRNA family. As shown in Figure 2C, all five members of the miR-30 family have one 8-bp conserved target site in the 3′-UTR of CSE. It has been reported that binding sites with as few as 7 bp of complementarity (seed sequence) to the 5′-end of miRNA are sufficient for regulation in vivo (2, 9). This strongly led us to believe that the 3′-UTR of CSE could be a target of miR-30 family. In addition, we observed that the miR-30 family was upregulated and the CSE expression was downregulated in the remote and border zone of murine MI model as well as in the cardiomyocyte hypoxic model. This result also implied that CSE may be regulated by the miR-30 family, because miRNA is a negative regulator of gene expression (8). As expected, the notion was verified by the results of luciferase assay, gain-of-function and loss-of-function assay.

CSE, which is a predominant H2S-producing enzyme in the cardiovascular system, is responsible for major H2S production in the heart (22, 25). Thus far, there have been only a few publications that have delineated the relationship between miRNAs and H2S production. Yang et al. (44) have observed that miR-21 represses human SP1 protein expression by targeting the 3′-UTRs of the SP1 gene in SMCs, which, in turn, downregulates CSE mRNA expression and indirectly reduces H2S production; this was confirmed by Cindrova-Davies et al. (7) and Toldo et al. (34). In this work, we provided novel evidence that the miR-30 family was able to regulate H2S production by directly targeting CSE. MiR-30 suppresses CSE expression at both mRNA and protein levels, indicating that miR-30 regulates CSE expression by promoting mRNA degradation. On the other hand, Shen et al. (31) and Liu et al. (21) found that H2S participate in different pathological and physiological processes by regulating miRNA expression. These demonstrate that the regulation between H2S and miRNA is mutual.

A growing body of experimental literature has indicated that increased H2S levels exogenously or endogenously protect against MI injury (17, 28), but that decreased H2S levels produced by inhibiting CSE result in aggravated MI injury (1, 38, 46). In this study, we observed that the overexpression of miR-30 family members reduced CSE expression and H2S production. In contrast, the downregulation of the miR-30 family increased CSE expression and H2S production. These findings predicted that miR-30 may participate in MI injury by regulating H2S levels. To confirm this presumption, we used an in vitro model of hypoxic injury and an in vivo MI model and observed that the overexpression of the miR-30 family aggravated hypoxia-induced injury. However, the downregulation of the miR-30 family by LNA-miR-30 FI protected cardiomyocytes in vitro, but this effect was abolished by cotransfecting with CSE-siRNA, indicating that the effect of miR-30 depends on the regulation of CSE. This pointed out that the additional increase in CSE level caused by LNA-miR-30 FI was required to establish the protective effects on cardiomyocytes during hypoxia. Similarly, the downregulation of the miR-30 family by LNA-miR-30 FI in vivo protected mouse heart against MI injury, but this cardioprotective effect was absent in CSE−/− mice model. This indicated that the protective effect of LNA-miR-30 FI, indeed, depends on CSE. Furthermore, the overexpression of miR-30b exacerbated MI injury, and this role of miR-30b can be rescued by SPRC, which is a novel modulator of CSE, or be further aggravated by PAG, which is a selective inhibitor of CSE. These effects were associated with the changes in H2S concentration in plasma, indicating that miR-30 participates in the protection of ischemic injury by regulating H2S production.

The effect of LNA-miR-30 FI on improvement of cardiac function may be attributable to the anti-oxidant action and anti-apoptotic effect of H2S. We previously reported (39) that a modulator of endogenous hydrogen sulfide-SPRC has cardioprotective effects in MI by reducing the deleterious effects of oxidative stress through the modulation of the endogenous H2S level. Similarly, Geng et al. (17) also proposed that H2S protects the heart from isoproterenol-induced ischemic injury, at least in part by scavenging oxygen-free radicals and attenuating lipid peroxidation. Besides, studies also show that H2S has anti-apoptotic properties and is known to increase Bcl-2 and reduce Bax expression (10, 41). Our results showed that LNA-miR-30 FI increased the activities of SOD and CAT, but decreased the MDA levels. Moreover, inhibition of the miR-30 family reduced apoptotic cell numbers in hypoxia cell model and in the peri-infracted region of MI model. In addition, we observed that miR-30 FI administration in vivo increased Bcl-2 and decreased Bax expression. Taken together, we propose that the effects of miR-30 on cardiac function were a consequence of the increase in H2S production induced by miR-30 FI.

Finally, we have shown that the LNA-modified miR-30 FI is efficient in the potent silencing of miR-30 family members both in vitro and in vivo. This indicated that LNA-modified oligos targeting seed region is a good method to inhibit a whole miRNA family simultaneously. Obad et al. (24) have found that 7- to 8-mer fully modified LNA oligonucleotides which target the miRNA seed sequence can inhibit entire miRNA families that share the same seed sequence. Hullinger et al. (18) also observed that using an 8-mer LNA-anti-miR complementary to the miR-15 family seed region dose dependently represses all miR-15 family members in both murine and porcine cardiac tissue. LNA-modified oligonucleotides targeting seed region have become an increasingly and widely used experimental approach to inhibit miRNAs family simultaneously. A practical problem in administering LNA-miRNA inhibitor systemically is the effect on nontarget tissues, in that most miRNAs are expressed in many different tissue types. This could be remedied by oligonucleotide packaging such as lipid formulations and conjugation with high-affinity molecules using nanotechnology for guidance to the target tissues (35). The ability of the LNA-miR-30 FI in protecting cardiomyocytes against ischemic injury suggests the potential of miR-30 as a target for molecular therapy. Normalization of the miR-30 level to the normal range may well be a novel strategy for protecting cardiac ischemic injury.

In conclusion, our study is the first to identify and validate CSE as a target of the miR-30 family and to demonstrate the role of the miR-30 family in MI injury. We propose that the miR-30–CSE–H2S axis contributes to protection against cardiac ischemic injury. The miR-30 family functions during MI may provide additional insights into the role of miRNAs in these processes and establish miR-30 as potential therapeutic targets for ischemic heart diseases.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Healthy male Sprague–Dawley rats (weight, 200–250 g) and C57BL/6 (8–10 weeks old) mice were used for this experiment. The CSE knockout mice were a gift from Shanghai Research Center for Model Organisms, Shanghai, China. CSE-KO and WT control animals used in this study were littermates obtained via heterozygous breeding. Genotype was determined by a single PCR with forward primer (5′-CCTGGATATAAGCGCCAAAG-3′) and reverse primer (5′-AGGAACCAGGGCGTATCTCT-3′). This reaction yields a 309 bp product from a transgenic allele. The forward primer with another reverse prime (5′-GAGAATTCCATTGCTCAGG-3′) produced a 167 bp product from a WT allele. All animal experiments were performed in accordance with the Animal Management Rules of the local authorities and approved by the Animal Research Ethics Committee of the School of Pharmacy of Fudan University.

MI models

Left descending coronary artery ligation was performed to induce MI model as previously reported (46). Detailed description can be found in the online supplementary materials.

Real-time PCR

The total RNA that was enriched with small RNAs was isolated from cultured cardiomyocytes or heart tissue with a mirVanamiRNA isolation kit (Ambion, Austen, TX) according to the manufacturer's instructions. For the quantitative detection of CSE mRNA, the SYBR Green I (Takara, Dalian, China) incorporation method was used with GAPDH as an internal control. The levels of miR-30 family were detected with the TaqMan MicroRNA Assay Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) with U6 as an internal control. More details can be found in the online supplementary materials.

Cell culture

Primary cardiomyocytes were obtained from the ventricles of neonatal Sprague–Dawley rats (1–2 days old) according to the method described by Wang et al. (38). The isolated primary cardiomyocytes were seeded at a density of 1×106 cells/ml in D/F12 that was supplemented with 10% FBS (Gibco, Grand Island, NY), 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 mg/ml streptomycin, and 100 μM 5-bromodeoxyuridine (Sigma, St. Louis, MO). HEK293 cells were cultured in high-glucose Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (Gibco) that was supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. All cells were cultured in a humidified incubator at 37°C with 95% O2 and 5% CO2.

Transfection of miRNA mimics or LNA-miRNA Inhibitor

MiR-30a, miR-30b, miR-30c, miR-30d, and miR-30e mimics and the miRNA mimic Negative Control #1 were obtained from Ambion. The LNA-modified miRNA FI and a scrambled NC were obtained from Exiqon (Vedbaek, Denmark). For details, see the online supplementary materials.

Plasmid construction and transfections

The open reading frame (ORF) of CSE (GenBank ID: NM_017074) was amplified and cloned into the expression vector pcDNA3.1 (+) to obtain pcDNA3.1-CSE plasmid, which was transfected into primary cardiomyocytes with Lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). More details can be found in the online supplementary materials.

Hypoxia cell model

Hypoxia cell model was induced in accordance with the technique described by Rakhit et al. (29). Cardiomyocytes were first placed in a hypoxic solution (NaCl, 116 mM; KCl, 50 mM; CaCl2, 1.8 mM; MgCl2·6H2O, 2 mM; NaHCO3, 26 mM; and NaH2PO4·2H2O, 1 mM) and subsequently incubated in a humidified atmosphere at 37°C in a 3-gas hypoxic chamber that was maintained at 5% CO2, 1% O2, and 94% N2 for 8 h.

Cardiomyocyte survival assays

After exposure to normoxia or hypoxia for 8 h, MTT and TUNEL assay were used to determine cell survival and apopotosis. Detailed description can be found in the online supplementary materials.

LDH, CK, and cTn-I levels

LDH, CK, and cTn-I were detected to evaluate the severity of cardiomyocyte injury. More details can be found in the online supplementary materials.

Antioxidant enzyme analysis

For the determination of antioxidant enzyme activities, 0.1 g left ventricular tissues were homogenized as 1:100 in 50 mM ice-cold potassium phosphate buffers (pH 6.8). MDA, CAT, and SOD were detected by using commercially available kits according to the manufacturer's instructions (Jiancheng Bioengineering Institute, Nanjing, China).

Measurement of H2S concentration

H2S concentration was measured as previously described (38). More details can be found in the online supplementary materials.

Luciferase reporter constructs and luciferase assay

The WT 3′-UTR fragment of CSE that contained the putative binding site for the miR-30 family was obtained by PCR and inserted into a pmiR-RB-REPORT dual luciferase reporter vector (Ribobio, Guangzhou, China). The seed region mutant plasmid was also constructed as a control. Luciferase assays were performed according to the manufacturer's instructions (Promega, Madison, WI). For details, see the online supplementary materials.

Western blot analysis

Total protein samples were extracted from the cultured primary cardiomyocytes and heart tissue for protein immunoblotting as previously described (38). For details, see the online supplementary materials.

Immunofluorescence staining

Forty-eight hours after transfection, cardiomyocytes were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde (Sigma), which was followed by blocking with 3% BSA (Amresco, Solon, OH). The monoclonal mouse anti-CSE primary antibody (Abcam, Cambridge, United Kingdom) was then added, and the cells were incubated for 1 h at room temperature. Then, the cells were incubated with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated secondary antibody (Molecular Probe, Grand Island, NY) in the dark for 1 h. For nuclear staining, the cells were stained with 4,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) for 5 min before examinations for visualization with a laser scanning confocal microscope (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany).

Delivery of the miRNA modulator and drugs

The indicated doses of in vivo LNA-miR-30 FI obtained from Exiqon were intravenously injected into C57BL/6 mice (8–10 weeks old) for 3 consecutive days before MI surgery; LNA-scrambled control or a comparable volume of saline was also injected as a control.

GFP-tagged lentivirus particles carrying the mmu-mir-30b precursor and its control were purchased from GeneChem (Shanghai, China). The lentiviral transduction was conducted according to advice from GeneChem. In brief, 2.5×107 TU of lentivirus particles were diluted in 200 μl saline and administered into the tail vein at 8 days before MI surgery. Meanwhile, 20 mg/kg of SPRC or 15 mg/kg PAG (Sigma) was injected intraperitoneally on a daily basis for 8 days in different groups before surgery.

Infarct size determination

Forty-eight hours after the MI surgery, the mice were anesthetized and a median sternotomy was performed. Evans Blue dye (0.3 ml of a 1.0% solution; Sigma) was injected into the heart from the cardiac apex to delineate the ischemic zone from the nonischemic zone. 0.1% triphenyltetrazolium chloride (TTC, w/v) solution was used to demarcate the viable and nonviable myocardium within the AAR. More details can be found in online supplementary materials.

Echocardiography

Five days after the MI surgery, two-dimensional echocardiography was performed on mice with a Vevo770 ultrasound machine (VisualSonics, Inc., Toronto, Canada) that was equipped with a 10-MHz phased-array transducer to test left ventricular function. A detailed description can be found in online supplementary materials.

Statistical analysis

All data analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 5 software. One-way analysis of variance was used to examine the statistical comparisons among multiple groups. Two-tailed Student's t-tests were performed to examine the statistical significance of the differences between two groups. Differences were considered significant with p<0.05.

Supplementary Material

Abbreviations Used

- AAR

area at risk

- CAT

catalase

- CK

creatine kinase

- CSE

cystathionine-γ-lyase

- cTn-I

cardiac troponin-I

- DAPI

4,6′-diamidino-2-phenylindole

- EF

ejection fraction

- FI

family inhibitor

- FS

fractional shortening

- H2S

hydrogen sulfide

- I/R

ischemia/reperfusion

- LDH

lactate dehydrogenase

- LNA

locked nucleic acid

- LVEDV

left ventricular end-diastolic volume

- LVESV

left ventricular end-systolic volume

- LVIDd

left ventricular internal dimension diastole

- LVIDs

left ventricular internal dimension systole

- MDA

malonaldehyde

- MI

myocardial infarction

- NC

negative control

- PAG

propargylglycine

- SOD

superoxide dismutase

- SPRC

S-propargyl-cysteine

- TTC

triphenyltetrazolium chloride

- UTR

untranslated region

- WT

wild-type

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the National Nature Science Foundation of China (No.: 81402919), the National Basic Research Program of China (973 Program, No.: 2010CB912600), the National Science and Technology Major Project (No.: 2012ZX09501001-003), the key program of National Nature Science Foundation of China (No.: 81330080), and the Key Program of Shanghai Committee of Science and Technology in China (No. 10431900100).

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interest exist.

References

- 1.Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: genomics, biogenesis, mechanism, and function. Cell 116: 281–297, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brennecke J, Stark A, Russell RB, and Cohen SM. Principles of microRNA–target recognition. PLoS Biol 3: e85, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bridge G, Monteiro R, Henderson S, Emuss V, Lagos D, Georgopoulou D, Patient R, and Boshoff C. The microRNA-30 family targets DLL4 to modulate endothelial cell behavior during angiogenesis. Blood 120: 5063–5072, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Calvert JW, Coetzee WA, and Lefer DJ. Novel insights into hydrogen sulfide–mediated cytoprotection. Antioxid Redox Signal 12: 1203–1217, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Calvert JW, Elston M, Nicholson CK, Gundewar S, Jha S, Elrod JW, Ramachandran A, and Lefer DJ. Genetic and pharmacologic hydrogen sulfide therapy attenuates ischemia-induced heart failure in mice. Circulation 122: 11–19, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheng CW, Wang HW, Chang CW, Chu HW, Chen CY, Yu JC, Chao JI, Liu HF, Ding SL, and Shen CY. MicroRNA-30a inhibits cell migration and invasion by downregulating vimentin expression and is a potential prognostic marker in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat 134: 1081–1093, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cindrova-Davies T, Herrera EA, Niu Y, Kingdom J, Giussani DA, and Burton GJ. Reduced cystathionine γ-lyase and increased miR-21 expression are associated with increased vascular resistance in growth-restricted pregnancies: hydrogen sulfide as a placental vasodilator. Am J Pathol 182: 1448–1458, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dalmay T. Mechanism of miRNA-mediated repression of mRNA translation. Essays Biochem 54: 29–38, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doench JG. and Sharp PA. Specificity of microRNA target selection in translational repression. Genes Dev 18: 504–511, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dongó E, Hornyák I, Benkő Z, and Kiss L. The cardioprotective potential of hydrogen sulfide in myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury (Review). Acta Physiol Hung 98: 369–381, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dong S, Cheng Y, Yang J, Li J, Liu X, Wang X, Wang D, Krall TJ, Delphin ES, and Zhang C. MicroRNA expression signature and the role of microRNA-21 in the early phase of acute myocardial infarction. J Biol Chem 284: 29514–29525, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Downey JM. and Cohen MV. Why do we still not have cardioprotective drugs? Circ J 73: 1171–1177, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Duisters RF, Tijsen AJ, Schroen B, Leenders JJ, Lentink V, van der Made I, Herias V, van Leeuwen RE, Schellings MW, Barenbrug P, Maessen JG, Heymans S, Pinto YM, and Creemers EE. miR-133 and miR-30 regulate connective tissue growth factor: implications for a role of microRNAs in myocardial matrix remodeling. Circ Res 104: 170–178, 6p following 178, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elrod JW, Calvert JW, Morrison J, Doeller JE, Kraus DW, Tao L, Jiao X, Scalia R, Kiss L, and Szabo C. Hydrogen sulfide attenuates myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury by preservation of mitochondrial function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104: 15560–15565, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fiedler J, Batkai S, and Thum T. MicroRNA-based therapy in cardiology. Herz 39: 194–200, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fiedler J, Jazbutyte V, Kirchmaier BC, Gupta SK, Lorenzen J, Hartmann D, Galuppo P, Kneitz S, Pena JT, and Sohn-Lee C. MicroRNA-24 regulates vascularity after myocardial infarction. Circulation 124: 720–730, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Geng B, Chang L, Pan C, Qi Y, Zhao J, Pang Y, Du J, and Tang C. Endogenous hydrogen sulfide regulation of myocardial injury induced by isoproterenol. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 318: 756–763, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hullinger TG, Montgomery RL, Seto AG, Dickinson BA, Semus HM, Lynch JM, Dalby CM, Robinson K, Stack C, and Latimer PA. Inhibition of miR-15 protects against cardiac ischemic injury novelty and significance. Circ Res 110: 71–81, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ikeda S, Kong SW, Lu J, Bisping E, Zhang H, Allen PD, Golub TR, Pieske B, and Pu WT. Altered microRNA expression in human heart disease. Physiol Genomics 31: 367–373, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jentzsch C, Leierseder S, Loyer X, Flohrschutz I, Sassi Y, Hartmann D, Thum T, Laggerbauer B, and Engelhardt S. A phenotypic screen to identify hypertrophy-modulating microRNAs in primary cardiomyocytes. J Mol Cell Cardiol 52: 13–20, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu J, Hao D-D, Zhang J-S, and Zhu Y-C. Hydrogen sulphide inhibits cardiomyocyte hypertrophy by up-regulating miR-133a. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 413: 342–347, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu Y-H, Lu M, Hu L-F, Wong PT-H, Webb GD, and Bian J-S. Hydrogen sulfide in the mammalian cardiovascular system. Antioxid Redox Signal 17: 141–185, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Long G, Wang F, Duan Q, Yang S, Chen F, Gong W, Yang X, Wang Y, Chen C, and Wang DW. Circulating miR-30a, miR-195 and let-7b associated with acute myocardial infarction. PLoS One 7: e50926, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Obad S, dos Santos CO, Petri A, Heidenblad M, Broom O, Ruse C, Fu C, Lindow M, Stenvang J, and Straarup EM. Silencing of microRNA families by seed-targeting tiny LNAs. Nat Genet 43: 371–378, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pan LL, Liu XH, Gong QH, Yang HB, and Zhu YZ. Role of cystathionine γ-lyase/hydrogen sulfide pathway in cardiovascular disease: a novel therapeutic strategy? Antioxid Redox Signal 17: 106–118, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pan W, Zhong Y, Cheng C, Liu B, Wang L, Li A, Xiong L, and Liu S. MiR-30-regulated autophagy mediates angiotensin II-induced myocardial hypertrophy. PLoS One 8: e53950, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pan Z, Sun X, Shan H, Wang N, Wang J, Ren J, Feng S, Xie L, Lu C, and Yuan Y. MicroRNA-101 inhibited postinfarct cardiac fibrosis and improved left ventricular compliance via the FBJ osteosarcoma oncogene/transforming growth factor-β1 pathway clinical perspective. Circulation 126: 840–850, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Qipshidze N, Metreveli N, Mishra PK, Lominadze D, and Tyagi SC. Hydrogen sulfide mitigates cardiac remodeling during myocardial infarction via improvement of angiogenesis. Int J Biol Sci 8: 430, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rakhit RD, Edwards RJ, Mockridge JW, Baydoun AR, Wyatt AW, Mann GE, and Marber MS. Nitric oxide-induced cardioprotection in cultured rat ventricular myocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 278: H1211–H1217, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sayed D, Hong C, Chen I-Y, Lypowy J, and Abdellatif M. MicroRNAs play an essential role in the development of cardiac hypertrophy. Circ Res 100: 416–424, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shen J, Xing T, Yuan H, Liu Z, Jin Z, Zhang L, and Pei Y. Hydrogen sulfide improves drought tolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana by MicroRNA expressions. PLoS One 8: e77047, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shibuya N, Tanaka M, Yoshida M, Ogasawara Y, Togawa T, Ishii K, and Kimura H. 3-Mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase produces hydrogen sulfide and bound sulfane sulfur in the brain. Antioxid Redox Signal 11: 703–714, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thum T, Galuppo P, Wolf C, Fiedler J, Kneitz S, van Laake LW, Doevendans PA, Mummery CL, Borlak J, and Haverich A. MicroRNAs in the human heart a clue to fetal gene reprogramming in heart failure. Circulation 116: 258–267, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Toldo S, Das A, Mezzaroma E, Chau VQ, Marchetti C, Durrant D, Samidurai A, Van Tassell BW, Yin C, Ockaili RA, Vigneshwar N, Mukhopadhyay ND, Kukreja RC, Abbate A, and Salloum FN. Induction of MicroRNA-21 with exogenous hydrogen sulfide attenuates myocardial ischemic and inflammatory injury in mice. Circ Cardiovasc Genet 7: 311–320, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Toub N, Malvy C, Fattal E, and Couvreur P. Innovative nanotechnologies for the delivery of oligonucleotides and siRNA. Biomed Pharmacother 60: 607–620, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Van Rooij E, Sutherland LB, Thatcher JE, DiMaio JM, Naseem RH, Marshall WS, Hill JA, and Olson EN. Dysregulation of microRNAs after myocardial infarction reveals a role of miR-29 in cardiac fibrosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 105: 13027–13032, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang J, Guan X, Guo F, Zhou J, Chang A, Sun B, Cai Y, Ma Z, Dai C, Li X, and Wang B. miR-30e reciprocally regulates the differentiation of adipocytes and osteoblasts by directly targeting low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 6. Cell Death Dis 4: e845, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang Q, Liu H-R, Mu Q, Rose P, and Zhu YZ. S-propargyl-cysteine protects both adult rat hearts and neonatal cardiomyocytes from ischemia/hypoxia injury: the contribution of the hydrogen sulfide-mediated pathway. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 54: 139–146, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wang Q, Wang X-L, Liu H-R, Rose P, and Zhu Y-Z. Protective effects of cysteine analogues on acute myocardial ischemia: novel modulators of endogenous H2S production. Antioxid Redox Signal 12: 1155–1165, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang R. Two's company, three's a crowd: can H2S be the third endogenous gaseous transmitter? FASEB J 16: 1792–1798, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang X, Wang Q, Guo W, and Zhu Y. Hydrogen sulfide attenuates cardiac dysfunction in a rat model of heart failure: a mechanism through cardiac mitochondrial protection. Biosci Rep 31: 87–98, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wei C, Li L, and Gupta S. NF-kappaB-mediated miR-30b regulation in cardiomyocytes cell death by targeting Bcl-2. Mol Cell Biochem 387: 135–141, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yang B, Lin H, Xiao J, Lu Y, Luo X, Li B, Zhang Y, Xu C, Bai Y, and Wang H. The muscle-specific microRNA miR-1 regulates cardiac arrhythmogenic potential by targeting GJA1 and KCNJ2. Nat Med 13: 486–491, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yang G, Pei Y, Cao Q, and Wang R. MicroRNA-21 represses human cystathionine gamma-lyase expression by targeting at specificity protein-1 in smooth muscle cells. J Cell Physiol 227: 3192–3200, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yellon DM. and Hausenloy DJ. Myocardial reperfusion injury. N Engl J Med 357: 1121–1135, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhu YZ, Wang ZJ, Ho P, Loke YY, Zhu YC, Huang SH, Tan CS, Whiteman M, Lu J, and Moore PK. Hydrogen sulfide and its possible roles in myocardial ischemia in experimental rats. J Appl Physiol 102: 261–268, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.