SUMMARY

The steep dependence of exocytosis on Ca2+ entry at nerve terminals implies that voltage control of both Ca2+ channel opening and the driving force for Ca2+ entry are powerful levers in sculpting synaptic efficacy. Using fast, genetically encoded voltage indicators in dissociated primary neurons, we show that at small nerve terminals K+ channels constrain the peak voltage of the presynaptic action potential (APSYN) to values much lower than those at cell somas. This key APSYN property additionally shows adaptive plasticity: manipulations that increase presynaptic Ca2+ channel abundance and release probability result in a commensurate lowering of the APSYN peak and narrowing of the waveform, while manipulations that decrease presynaptic Ca2+ channel abundance do the opposite. This modulation is eliminated upon blockade of Kv3.1 and Kv1 channels. Our studies thus reveal that adaptive plasticity in the APSYN waveform serves as an important regulator of synaptic function.

INTRODUCTION

The flow of information in neural circuits is primarily regulated by modulation of synaptic efficacy. Exocytosis of chemical neuro-transmitters is triggered by elevation of intracellular Ca2+ in the vicinity of the exocytosis machinery (Pumplin et al., 1981). This process is highly nonlinear, typically showing a 3rd–5th power-law relationship between Ca2+ influx and exocytosis (Ariel and Ryan, 2010; Augustine et al., 1985; Borst and Sakmann, 1998; Dodge and Rahamimoff, 1967; Mintz et al., 1995; Schneggen-burger and Neher, 2000; Scimemi and Diamond, 2012). The time course and magnitude of Ca2+ influx through voltage-gated calcium channels (VGCCs) is therefore poised to have enormous influence on chemical neurotransmission. At typical CNS synapses, presynaptic Ca2+ influx is mediated by CaV2.1 and CaV2.2 VGCCs (Ariel et al., 2012; Takahashi and Momiyama, 1993; Wheeler et al., 1994), so-called high-voltage-activated channels that require large membrane depolarizations to drive them to the open state. The presynaptic action potential(APSYN) controls the fraction of Ca2+ channels that open and the temporal envelope of the driving force for Ca2+ entry by rapid coordination of Na+ and K+ channel opening (NaV and KV, respectively) (Hille, 2001; Hodgkin and Huxley, 1952). The highly nonlinear influence of Ca2+ on exocytosis thus dictates that modest changes in AP properties have a large influence on synapse function.

Details of the action potential waveform have largely been deduced from cell somas and certain giant nerve terminals (Bean, 2007). Measurements of the AP peak in these experimental conditions recorded values (~40 mV) approaching the reversal potential for Na+ ions (Bean, 2007). As expected, blockade of KVs does not impact the AP peak mainly because it is dominated by Na+ flux (Alle et al., 2009). Given the typical voltage activation of VGCCs, such membrane potentials would likely drive virtually 100% of channels to an open state, leading to an all-or-none type calcium influx at synapses. Quantitative determinations of APSYN magnitude have largely been carried out in electrically accessible nerve terminals (Boudkkazi et al., 2011; Taschenberger and von Gersdorff, 2000), many of which have specialized architectures that carry out high-fidelity relay operations (Forsythe and Barnes-Davies, 1993). However, much less is known about the amplitude and kinetics of the AP at more typical small en passant CNS boutons. Recent optical measurements found that the somatic AP and APSYN at distal boutons have different shapes in cortical neurons and are differentially influenced by KV channels (Foust et al., 2011; Rowan et al., 2014).

Here we made use of recent developments in fast (400 μs) genetically encoded fluorescent voltage indicators (Kralj et al., 2012, Maclaurin et al., 2013) to carry out measurements at single en passant boutons in dissociated hippocampal neurons where somatic AP waveforms are known to operate in the 1.5–2.5 ms regime (Abdul-Ghani et al., 1996; Gong et al., 2008; Kralj et al., 2012; Mitterdorfer and Bean, 2002). We show that unlike at the cell soma, the APSYN peak is heavily influenced by KV function. Use of ionophore-based calibration allowed us to estimate this peak APSYN membrane potential at ~+7 mV, placing it in a regime that would enable very efficient modulatory control of Ca2+ currents through changes in KV function. We go on to show that such control is manifest in adaptive plasticity, where changes in nerve terminal VGCC abundance result in changes in APSYN wave-form that in turn serve to maintain release properties in a useful operating range.

RESULTS

Archaerhodopsin-Based Recordings of Action Potentials at Single Nerve Terminals

Although optical recordings of membrane voltage using electro-chromic dyes have been successfully used, their utility has been restricted. Labeling cells by injection techniques or the eventual internalization of extracellular membrane dyes by their nature limits the complexity and length of experiments (Bradley et al., 2009; Foust et al., 2011; Popovic et al., 2011; Sabatini and Regehr, 1997). Genetically encoded optical membrane potential indicators in principle circumvent these technical barriers. It was recently discovered that Archaerhodopsin (Arch) emits fluorescence that is linearly proportional to membrane potential with rapid response kinetics (Maclaurin et al., 2013). This opens the door to detailed measurements of action potential (AP) waveforms in subcellular regions that are not amenable to electrode-based recordings (Peterka et al., 2011). When expressed in dissociated primary hippocampal neurons, Arch-GFP localizes to all regions of the cell (Figure 1A), including dendrites, fine axonal arbors, and presynaptic boutons. Although the quantum yield for Arch fluorescence when excited at 640 nm is low, its far-red fluorescence emission and excellent voltage sensitivity makes it feasible to image this probe even at synaptic boutons (Figure 1A inset). When imaged at high-time resolution (2 kHz), the bouton fluorescence showed distinct time-locked spikes when a train of APs were triggered using field stimulation (Figure 1B). Measurements from single boutons showed that the signal-to-noise ratio associated with detecting individual spikes was ~4:1, and averaging over several hundred trials resulted in very-high-fidelity recordings of the apparent AP waveform (Figure 1C). To confirm that these presynaptic voltage spikes were indeed APs, we varied the strength of the field stimulus and found that the spikes appeared in an expected all-or-none fashion as one presumably crosses a minimal threshold for AP initiation (Figures S1A and S1B, available online). Furthermore, these signals were dependent on Na+ channel function as the spikes were eliminated in the presence of Tetrodotoxin (TTX) (Figure 1C), revealing a small direct field-stimulus impact on the local membrane potential. The presence of the direct-field stimulus-driven membrane potential change suggests that the recorded spike waveform is the superposition of the propagating AP with the direct field stimulus-driven change in membrane potential. Although in principle these two components could sum nonlinearly, we reasoned that the direct field stimulus contribution is sufficiently small that a linear approximation would hold, allowing one to recover the AP waveform from the recorded spike by subtracting the signal obtained in the presence of TTX (Figure 1D). We tested the validity of this assumption by comparing AP waveforms generated by opposite polarity field stimuli at the same boutons (Figure S1C). These experiments showed that provided the field stimulus-driven membrane potential change was less than 10% of the AP peak, its polarity did not influence the shape of the extracted AP waveform (Figures S1C and S1D), and thus the linear superposition assumption was valid (Figure S1E). All subsequent analysis was restricted to recordings that satisfied this criterion. As one can improve the signal to noise by averaging over many trials, it is important to determine if this impacts the ability to accurately extract AP parameters. Previous use of electrochromic dye indicators to follow neuronal activity suffered from considerable phototoxicity, so we examined the stability of the signals across trials under our recording conditions. These experiments demonstrated that Arch appears to have remarkable photostability, as the spike amplitude is stable over the entire imaging period (~100,000 frames, 400 trials) (Figures 1E and 1F). A second concern is whether any temporal jitter associated with each trial might lead to significant broadening of the averaged signal. We chose a subset of experiments with the highest signal to noise for single trial spikes (>9:1) and used spline fitting (Figure S1F) to determine the AP width from each trial and compared the average spline fit value of the full width at half maximum (FWHM) across 400 trials with the FWHM of the average trace (Figure 1G). Similar analysis across a population of boutons showed that the FWHMs calculated using these two approaches were statistically indistinguishable (1.4% ± 4.6%, n = 6). For a more accurate estimate of both peak ΔF/F values and the FWHM during an action potential, we also corrected the traces for the low-pass filtering imposed by the time resolution of Arch’s response to Vm changes, which could lead to underestimation of AP peak and overestimation of FWHM values (Figure S1G, see Experimental Procedures). Using these approaches, we characterized the APSYN from a collection of boutons. On average, APSYN reached a peak fluorescence over baseline of 0.45 ± 0.03 ΔF/F and had a FWHM of 2.27 ± 0.26 ms (n = 24).

Figure 1. Optical Measurements of Action Potential Waveforms.

(A) Montage of several fields (GFP fluorescence) from a dissociated hippocampal neuron expressing Arch-GFP. Red arrow represents a typical region of measurements of presynaptic waveforms. Scale bar, 10 μm. Inset image showing the Arch fluorescence of two en passant boutons; scale bar, 2 μm.

(B) Arch fluorescence intensity of the boutons shown in (A) stimulated with single stimuli at 8 Hz. Red arrow indicates stimulation.

(C) Average AP recorded from the boutons shown in (A) with (red) and without (black) the addition of TTX.

(D) Action potential after subtraction of direct field effect (black minus red as shown in B).

(E) Individual single bouton peak ΔF/F for 390 consecutive trials shows no apparent rundown.

(F) Representative consecutive 8 Hz 50-trial averages of the presynaptic AP waveform spaced for clarity.

(G) FWHM extracted from each of 400 single trials at a single bouton with spline fitting (see Experimental Procedures and Figure S1F) compared to the the FWHM of the trial averaged AP waveform (dashed line).

Presynaptic Bouton AP Is Controlled by KV1 and KV3.1 Potassium Channels

In general, the value of the AP peak and the speed of repolarization are dictated by the abundance and kinetics of Na+ and K+ channels in different cellular regions. In order to determine which K+ channels control the AP waveform, we used a combination of pharmacology and shRNA-based knockdown. Previous reports indicate that APs in axons mainly rely on a combination of Shaker (KV1) and Shaw (KV3) family K+ channels as well as calcium-activated K+ channels (BKCa) under some conditions (Alle et al., 2011; Boudkkazi et al., 2011; Debanne et al., 2011; Deng et al., 2013; Foust et al., 2011; Johnston et al., 2010; Kole et al., 2007). We found that APSYN was completely insensitive to the BKCa channel blocker iberiotoxin (IBX, 100 nM; Figures 2A and 2B) or to removal of external calcium (data not shown). In contrast, application of 1 mM tetraethylammonium (TEA), an inhibitor of KV3 and KV1 channels (Gutman et al., 2005), led to increases in the peak APSYN (109% ± 8%) as well as the FWHM (2.99 ± 0.58 ms) (Figures 2A and 2B). Similarly, application of dendrotoxin-K (DTX, 100 nM), a blocker of KV1.1, KV1.2, and KV1.6 family K+ channels, also led to an increase in the APSYN peak (113% ± 8%) and FWHM (3.84 ± 0.60 ms; Figures 2A and 2B). Both toxins also eliminated the after-hyperpolarization. Simultaneous addition of both toxins led to roughly additive effects on the peak APSYN (133% ± 9%) as well as the FWHM (4.51 ± 0.60 ms; Figures 2A and 2B). In contrast, dual application of DTX and TEA impacted the FWHM (increase of 48% ± 18%; Figure 2C), but not the amplitude (Figure 2D) of the somatic AP waveform. These findings were consistent with previous measurements using patch-clamp recordings at the cell body (Kole et al., 2007; Mitterdorfer and Bean, 2002; Storm, 1987). None of these KV toxins significantly altered the resting baseline fluorescence of Arch (p = 0.89, n = 7 pre- and post-TEA and DTX application; data not shown), indicating that resting membrane potential was unaltered by blockade of these KVs.

Figure 2. K+ Channel Modulation of Presynaptic Action Potential Waveform.

(A) Population average AP waveforms from synaptic boutons in control (black; n = 24) in the presence of iberiotoxin (Iberia, 100 nM, magenta; n = 6), tetraethylammonium chloride (TEA, 1 mM, red; n = 9), dendrotoxin-K (DTX, 100 nM, blue; n = 13), and a combination of TEA and DTX (green; n = 10). Somatic APs are shown under control conditions (gray) and in the presence of a combination of TEA and DTX (teal; n = 6). Peaks are normalized to control waveforms for boutons and soma, respectively; all dashed lines display SE of AP peak measurements.

(B) Average FWHM of the action potential waveforms shown in (A).

(C) Percent change in FWHM after application of TEA and DTX at the bouton (92% ± 31%) and soma (48% ± 18%).

(D) Average percent change in peak amplitude of the action potential waveforms after application of TEA and DTX at the bouton and soma. All error bars shown are mean ± SEM; *p < 0.05 and **p < 0.01 using ANOVA comparison with Turkey’s post hoc comparisons to determine significance.

In order to verify the conclusions based on pharmacological blockade, we made use of shRNA-mediated knockdown of KV3 and KV1 channels. As previous studies demonstrated that KV3.1b is preferentially trafficked to axons (Xu et al., 2007), we chose this isoform for shRNA targeting. We recorded the APSYN waveform in neurons simultaneously transfected with Arch and shRNA directed to KV3.1b and then examined the impact of TEA application on waveform characteristics (Figure 3A). These experiments demonstrated that KV3.1b KD increased APSYN amplitude (116% ± 10%) to values similar to those of control amplitude after treatment with TEA. Moreover, the addition of TEA no longer impacted the APSYN waveform in KV3.1b knock-down (KD) neurons (Figures 3A–3C). A number of KV1 family members have been reported to be potentially present in axons, in particular KV1.1 (Smart et al., 1998). Next, we recorded APSYN in neurons expressing shRNA-targeting Kv1.1 before and after DTX treatment. Loss of KV1.1 led to APSYN peak values (120% ± 5%) that were similar to controls treated with DTX, although we found that the resulting APSYN retained some sensitivity to further DTX application (Figures 3D and 3E) and maintained a FWHM similar to controls (2.81 ± 0.26 ms for Kv1.1 KD without DTX). Quantitative immunofluorescence staining against KV1.1 demonstrated that shRNA transfection led to >90% depletion of this protein (Figure S2). Thus, it seems likely that the remaining DTX sensitivity might arise from KV1 heterotetramers assembling from alternate subfamily members (for example KV1.2, KV1.3, KV1.6, etc.). Taken together, these results strongly indicate that KV3 and KV1 both serve to control the APSYN waveform.

Figure 3. KV3.1b and KV1 Control the Presynaptic AP.

(A) Population average APSYN recordings in control (left, n = 9) and shRNA targeting KV3.1b-expressing (right, n = 7) neurons. Population average APs for these two groups are shown in black and overplayed with APs recorded in the presence of TEA (red) for comparison. AP waveforms were also measured in the presence of a KV1 blocker (DTX) in both control and shRNA Kv3.1b cells in the absence (blue) and in the presence (green) of TEA.

(B) Ratio of peak AP waveform amplitude after addition of TEA for control and shRNA-targeted knockdown of Kv3.1b (shKv3.1b) normalized to pretreatment.

(C) FWHM measurements of the AP waveforms for control and shRNA KV3.1b neurons before and after inclusion of TEA.

(D) Ratio of peak AP waveform amplitude after addition of DTX for control and shRNA-targeted knockdown of Kv1.1 (shKv1.1) normalized to pretreatment (n = 13).

(E) FWHM measurements of the AP waveforms for control and shRNA Kv1.1 neurons before and after inclusion of DTX. All bar graphs shown are mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05.

The most striking feature of these experiments was the differential impact of KV blockade on the amplitude of APSYN compared to the somatic waveform. Indeed, if the action potentials both had amplitudes closer to the Na+ reversal potential, it is difficult to imagine how the Arch signal could rise 33% without exceeding it. To address this question, we attempted to locally calibrate Arch to estimate AP amplitudes in terms of voltage in different cellular regions.

Calibration of Arch Fluorescence Signals

Meaningful comparison of Arch responses in different regions cannot be made in the absence of local calibration. This is because only Arch fluorescence arising from copies of the indicator in the plasma membrane reflect Vm, but the total fluorescence reflects contrbutions from both the plasma membrane and intracellular compartments. To correct for variations in the surface fraction of Arch in different cellular regions, we developed an iononophore-based approach based on previous studies (Maric et al., 1998). We recorded AP waveforms subcellulary (soma or axon) and subsequently applied gramicidin, a cation-selective pore, to collapse the membrane potential (Vm) to 0 mV (Meunier, 1984; Podleski and Changeux, 1969) while monitoring the fluorescence change in the same subcellular regions (Figures 4A and 4B). This approach necessarily ignores possible differences in resting Vm in different regions, and given that the PNa/PK of gramicidin is ~3.5 (Hille, 2001) it may not fully bring Vm to 0. However, with these caveats in mind one can then compare the gramicidin response to the magnitude of the AP waveform at the subcellular level in a region-specific fashion. The mean ΔF/F response of gramicidin at boutons was 41.4% ± 2.8% (n = 6) and at somas was 15.6% ± 4% (n = 6). This difference likely reflects greater contributions in total fluorescence from intracellular compartments in the soma compared to the bouton. Comparison of the somatic AP peak amplitude with the somatic gramicidin response indicated that the somatic AP response was always ~50% larger than the latter (Figure 4C), while APSYN reached an amplitude that was roughly equivalent to the peak of the gramicidin response (Figure 4C). With the assumption that VREST = −65 mV (see Experimental Procedures) and that gramicidin collapses Vm to 0 in both regions, these data provide a local calibration for Arch (ΔF/FmV−1). The somatic calibration factor was 0.24% ± 0.09% ΔF/FmV−1, while the bouton calibration factor was 0.63% ± 0.03% ΔF/FmV−1. Using these calibration factors, we estimated the somatic AP peak at 37.6 ± 8.1 mV (Figures 4D and 4E), in close agreement with most electrophysiological measurements (Bean, 2007). In contrast, using the same approach at boutons we estimate that the APSYN reaches a peak of 6.8 ± 4.9 mV (Figures 4D and 4E).

Figure 4. Subcellular Calibration of Archaerhodopsin Fluorescence.

(A and B) Example action potential waveform recorded from en passant boutons (A) and a soma (B) with corresponding traces of Arch fluorescence during extracellular application of gramicidin bringing resting membrane potential (VREST) to ~0 mV (V0). Gramicidin trace has been filtered (5 Hz) for clarity from a 1 kHz recording.

(C) Average AP peak height normalized to corresponding gramicidin traces for individual boutons (1.03 ± 0.07; n = 6) and somas (1.53 ± 0.17; n = 6).

(D) Average paired recordings from the same neurons at the bouton and soma (n = 9) converted from fluorescence to mV based on this calibration.

(E) Average AP peak voltage of APs shown in (D). All bar graphs shown are mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05.

It is possible that either the presence of Arch or possible proton pumping by Arch might lead to underestimates of the APSYN peak. We tested for this possibility in three ways. First, we coexpressed WT Arch (fused to a nonfluorescent GFP, ArchDARK) with VAMP-mOr2 to mark synaptic boutons and loaded the transfected and adjacent untransfected boutons with Fluo5F (Figure S3A). Overlays of single AP-driven Ca2+ and Arch signals showed that the Ca2+ signal began to rise with minimal delay after the start of the AP reaching 55% ± 6% (n = 9) of the Ca2+ signal peak by the peak of the AP, almost identical to values previously obtained at similar recording temperatures (30°C; Sabatini and Regehr, 1996). Comparisons of the peak single AP-driven Ca2+ influx in Arch-transfected and untransfected boutons had identical amplitudes (0.73 ± 0.15 versus 0.71 ± 0.19, n = 9 and 11 cells, respectively; Figure S3B), indicating that expression of Arch did not impair Ca2+ influx and by extension did not alter the AP waveform. Second, we measured the efficacy of AP-driven exocytosis in boutons coexpressing ArchDARK and vGlut-pHluorin in the presence and absence of 640 nm illumination (Figures S3C–S3F). These experiments showed that the imaging conditions used to measure Arch fluorescence do not impact synaptic efficacy. Third, we compared the ratio of AP and gramicidin responses at somas and boutons using a non-pumping, but somewhat slower (~4-fold slower time resolution), variant of Arch (Arch EEQ; Gong et al., 2013). Using this mutant, we found that both somatic and bouton APs normalized to their gramicidin responses were lower than what we obtained with WT Arch (Figures S3G and S3H). We suspect that this discrepancy arises from the slower time resolution of this variant. Nonetheless, the ratio of the two gramicidin-normalized responses was ~1.33, similar to the 1.50 value obtained with WT Arch. These results indicate that complications from light-induced proton pumping under the conditions used here are likely minimal. The significant impact of KV blockade on APSYN, but not the somatic AP peak, taken together with our gramicidin-based calibration estimates indicate that the presynaptic action potential in these small boutons likely reaches a significantly lower Vm at its peak than that at cell somas.

Superlinear Control of Presynaptic Calcium Entry by KV3 and KV1

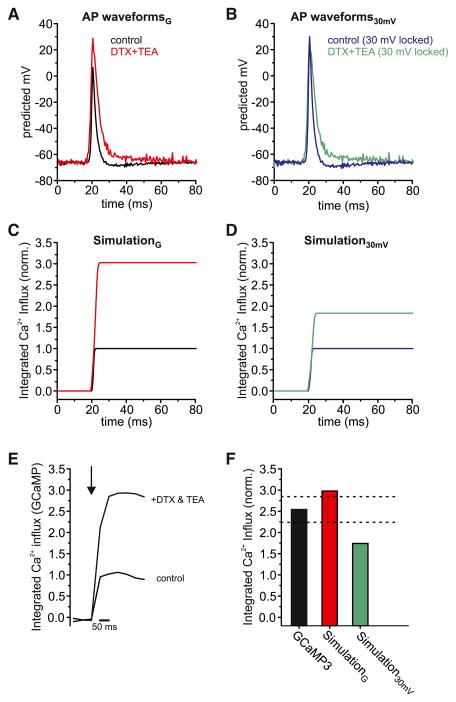

Voltage-gated Ca2+ channels open through a series of voltage-dependent transitions from the closed states (Li et al., 2007). Therefore, the rate of depolarization, the peak amplitude, and the FWHM can all have strong influences on AP-driven Ca2+ influx (Bischofberger et al., 2002; Borst and Sakmann, 1999; Sabatini and Regehr, 1997). The lower-amplitude APSYN waveform is well poised to allow significant nonlinear modulation of Ca2+ influx since it would tend to drive fewer VGCCs to the open state. In order to estimate how changes in APSYN waveforms might be expected to impact Ca2+ influx, we used previous measurements of the voltage-dependent gating properties of VGCCs (Li et al., 2007) to calculate the impact on integrated Ca2+ influx under KV blockade (see Experimental Procedures). We compared two different scenarios: in the first scenario we utilized waveforms with and without KV1 and KV3 blockade based on our gramicidin calibration (AP waveformsG with peak amplitudes of 28.7 ± 6.1 mV and 6.8 ± 3.8 mV, respectively; Figure 5A); in the second scenario we utilized APSYN with fixed 30 mV amplitudes and only varied the time courses (AP waveforms30mV; Figure 5B), more similar to what one would expect at cell somas. These two simulations predicted dramatically different estimates on the impact of Kv blockade on total Ca2+ influx: our gramicidin-based simulations predicted a ~3-fold increase in Ca2+ influx, while the fixed 30 mV amplitude simulation predicted only a ~1.7-fold increase after toxin blockade (Figures 5C and 5D). We tested these predictions by measuring Ca2+ influx before and after Kv blockade using a genetically encoded calcium sensor (GCaMP3) that naturally integrates [Ca2+] over short time scales (Figure 5E). We measured a 2.54 ± 0.29-fold (n = 9) increase in Ca2+ influx after application of KV-blocking toxins (Figure 5F). These value most closely match our numerical estimates of calcium influx using the gramicidin-calibrated AP waveforms (Figure 5F). Thus, the large changes in Ca2+ influx we observe are most accurately predicted if the starting AP waveform peaks at a much lower Vm than typically observed at cell somas.

Figure 5. Presynaptic Ca2+ Entry Controlled by KV3 and KV1.

(A) Peak-aligned gramicidin-calibrated APSYN waveforms (AP waveformsG) for control (black) and after DTX/TEA treatment (red).

(B) Peak-aligned waveforms from (A) normalized to maintain a constant peak (30 mV; AP waveforms30mV) before (blue) and after DTX/TEA treatment (green).

(C) Corresponding numerical estimates of the impact of DTX/TEA-driven changes in waveform on integrated Ca2+ influx based on known VGCC gating properties for our gramicidin-based APSYN (SimulationG).

(D) Corresponding numerical estimates of the impact of DTX/TEA-driven changes in waveform on integrated Ca2+ influx based on known VGCC gating properties for 30 mV locked amplitude (Simuation30mV).

(E) Representative measured (GCaMP3) single AP-driven presynaptic Ca2+ influx averaged for six trials (spaced at 30 s intervals) from boutons under control conditions and with the combination of TEA and DTX.

(F) Average single AP-driven bouton Ca2+ influx normalized to control conditions from n = 9 cells after application of DTX and TEA (black); dashed line represents measured SE. Red and green bars are the numerical estimates for the impact of DTX/TEA blockade on Ca2+ influx using our gramicidin-calibrated (SimulationG; red) or 30 mV amplitude (Simulation30mV; green) waveforms.

Modulation of Presynaptic Calcium Channel Abundance Leads to Adaptive Changes in the Presynaptic AP Waveform

The potent control of Kv channels on the APSYN peak opens the possibility for APSYN to serve as a substrate for modulation that could impact Ca2+ influx and release probability (Pr). Such control could work synergistically with direct modulation of VGCC function or abundance in controlling synaptic transmission. We previously showed that the abundance of presynaptic VGCCs is determined in a rate-limiting fashion by the availability of the VGCC subunit α2δ (Hoppa et al., 2012). α2δ’s are a family of GPI-anchored proteins whose expression drives presynaptic VGCCs accumulation and increased release probability (Pr), while removal leads to loss of presynaptic VGCCs and decreased Pr. We demonstated that part of the increase arose from changing the proximity of VGCCs to release sites (Hoppa et al., 2012), which could be expected from an increased density of channels at active zones. However, we expected that changing the number of active zone VGCCs would also increase total Ca2+ influx, which could also drive increases in Pr. Instead, we found that this increase in Pr was accompanied by lower AP-driven presynaptic Ca2+ influx as if the system had partially compensated for the closer coupling of VGCCs to release sites. We speculate that this could result from changes in APSYN confounding simple correlations of AP-driven Ca2+ influx and active zone VGCC abundance. We therefore compared APSYN measurements in control conditions with those where we coexpressed Arch with either overexpression of α2δ-1 (+α2δ-1) or an shRNA targeting α2δ-1. These experiments revealed that expression of α2δ strongly influenced the APSYN waveform: increasing α2δ expression lowered the APSYN peak amplitude and narrowed the FWHM, whereas the loss of α2δ did the opposite (Figures 6A–6C). Comparison of the α2δ overexpression with the shRNA knockdown across a population of neurons showed that genetic manipulation of VGCC abundance leads to an ~11 mV modulation (based on our gramicidin calibrations) in the APSYN peak amplitude and an ~800 μsec change in the FWHM. Thus, the APSYN waveform shows strong adaptive plasticity associated with changes in VGCC abundance. This modulation appears to be specific to the APSYN waveform, as direct comparisons of the somatic AP waveform between control and overexpression of α2δ showed no difference (Figures S4A–S4C).

Figure 6. Adaptive Plasticity of Action Potential Waveforms Mediated by KV3/KV1.

(A) Population average APSYN waveforms from control (black, n = 24), α2δ-1-overexpressing (red, n = 15), and α2δ-1-shRNA-expressing (blue, n = 11) neurons.

(B and C) Average peak (6.8 ± 3.8, 1.22 ± 2.6, and 13.95 ± 3.3 mV) and FWHM measurements (2.27 ± 0.26, 1.77 ± 0.11, and 2.72 ± 0.18 ms) of the associated AP waveforms shown in (A) for control, α2δ and shRNA α2δ conditions, respectively.

(D) Population average APSYN in the presence of DTX and TEA from control (black, n = 10), α2δ-1-overexpressing (red, n = 9), and α2δ-1-shRNA-expressing (blue, n = 9) neurons.

(E) Average peak voltage (28.7 ± 6.1, 24.8 ± 7.3, 27.0 ± 4.8) measurements of the AP waveforms shown in (D) (for control, α2δ, and shRNA α2δ conditions, respectively).

(F) FWHM (4.51 ± 0.56, 4.38 ± 0.62, and 4.98 ± 0.57 ms) measurements of the AP waveforms shown in (D) (for control, α2δ, and shRNA α2δ conditions, respectively).

These changes in APSYN suggest that the α2δ-induced regulation potentially acts through one of the KV channels primarily responsible for sculpting this waveform. If so, blocking these K+ channels should eliminate modulation imparted by α2δ. To test this hypothesis, we examined APSYN in the presence of the KV1 and KV3 channel blockers TEA and DTX for control, +α2δ-1, and shRNA targeting α2δ-1 neurons (Figure 6D). These experiments demonstrated that the modulation of APSYN conferred by α2δ was eliminated after KV3 and KV1 blockade: under KV blockade, both the peak and FWHM of APSYN are statistically identical for control, +α2δ-1, and shRNA targeting α2δ-1 neurons (Figures 6E and 6F).

Since blockade of both KV3 and KV1 eliminates the associated changes in APSYN driven by α2δ manipulation, one can use these same conditions to examine how α2δ manipulation impacts Ca2+ influx disentangled from any impact on APSYN. We measured Ca2+ influx using GCaMP3 in the presence of TEA + DTX and compared this for neurons cotransfected with either α2δ-1 or α2δ-1 shRNA. These experiments showed that overexpressing α2δ-1 led to a 33% increase, while depleting α2δ-1 led to a 40% decrease in Ca2+ influx (Figure 7A). Assuming that α2δ-1 does not alter VGCC gating properties, this predicts that overexpression or depletion of α2δ-1 led to a net gain of 1.31 ± 0.10 or a net decrease of 0.59 ± 0.09 in synaptic plasma membrane VGCC abundance, respectively (Figure 7B). We showed that changes in presynaptic Ca2+ influx imparted by Kv blockade were in excellent numerical agreement with the quantitative model of VGCC gating driven by our measured APSYN waveforms (Figure 5). We sought to determine if the changes in APSYN driven by α2δ manipulations would also lead to predictable changes in Ca2+ influx, taking into account the above predicted impact on VGCC surface abundance. GCaMP3-based measurements showed that α2δ-1 overexpression or shRNA-based α2δ-1 depletion resulted in a 40% or 20% decrease of presynaptic Ca2+ influx, respectively (Figure 7C). These measures were in excellent quantitative agreement with numerical estimates of integrated Ca2+ influx simulation based on VGCC gating (Figure 7C) driven by our measured APSYN under these conditions (Figure 6A), corrected for the separate changes in VGCC plasma membrane abundance driven by α2δ (Figure 7B). These data demonstrate that control of APSYN can dramatically alter Ca2+ influx, even lowering the influx despite increases in VGCC abundance.

Figure 7. Adaptive Plasticity in APSYN Compensates for Changes in Ca2+ Channel Density to Control Ca2+ Influx.

(A) Average integrated AP-driven Ca2+ influx measured from synaptic boutons in the presence of DTX and TEA from control (black, n = 9), α2δ-1-overexpressing (red, n = 8), and α2δ-1-shRNA-expressing (blue, n = 9) neurons. Bar graphs shown are mean ± SEM. *p < 0.05 using ANOVA comparison with Turkey’s post hoc comparisons to determine significance.

(B) Extrapolated relative density of presynaptic Cave channels normalized to control (black) for α2δ overexpression (red) and targeted knockdown with shRNA (blue). Bar graphs shown are mean ± SEM

(C) Average integrated Ca2+ influx measured from synaptic boutons stimulated with one action potential for α2δ overexpression (red) and targeted knockdown with shRNA (blue) as measured by GCaMP3 (solid bars with SEM shown by dashed lines) normalized to control for clarity. Corresponding numerical estimates predicting the integrated Ice for the gramicidin-calibrated waveforms (Simulation) corrected for changes in presynaptic VGCC abundance (striped bar graphs) are shown adjacently for comparison.

Adaptive changes in presynaptic function have previously been documented at the Drosophila neuromuscular junction, where the system responds rapidly to acute changes in the efficacy of neurotransmission (Müller and Davis, 2012). We wondered if the phenomena uncovered here might reflect a similar homeostatic response to modifications in neurotransmitter release. To test this idea, we examined the APSYN waveform at nerve terminals in which exocytosis, and hence neurotransmission, had been eliminated by chronic expression of tetanus toxin light chain (TeTx LC) that cleaves VAMP-2 (Schiavo et al., 1992). One might expect this manipulation to trigger increases in APSYN FWHM and peak similar to that obtained by removal of α2δ. In contrast, these experiments revealed that TeTx LC expression did not change AP waveform, indicating that the adaptive plasticity sculpting APSYN is not driven by changes in exocytosis (Figure S5). Rather, the adaptive plasticity controlling APSYN appears to be directly related to changes in VGCC abundance.

DISCUSSION

The AP waveform encodes parameters that transduce electrical information into a chemical signal via VGCCs. The relative Nav and Kv channel abundance and their biophysical properties are critical in determining the AP shape and amplitude. Relatively little is known about how the Nav/Kv balance is achieved, maintained, or potentially exploited for modulatory purposes. This is particularly true of small en passant presynaptic boutons where standard electrophysiological approaches are not easily applied. To examine the characteristics of the AP at small CNS en passant boutons, we made use of the discovery that the light-sensing protein Arch can be excited to generate fluorescence emission whose intensity is linearly proportional to Vm. Although this protein has typically been exploited to drive hyperpolarizing proton currents with light, we think this is unlikely to be playing a significant role in our experiments for several reasons: first, the red excitation used here is much less efficient than the optimum proton-pumping yellow wavelengths; second, the long time scales of exposure (10 s prior to recordings and recordings that last ~50 s) are known to typically inactivate proton pumping; third, we found that these same imaging conditions had no impact on action potential-driven exocytosis; fourth, we found good agreement with a non-proton-pumping mutant of Arch when comparing the gramicidin normalized ΔF/F AP amplitudes in somas versus boutons. The nonpumping variant of Arch, however, has an ~4-fold slower time resolution (Gong et al., 2013) and was not used for further experiments.

Kv Channels Play an Important Role in Controlling AP Amplitude at Synapses

To understand how APSYN might be controlled quantitatively, we devised an ionophore-based calibration scheme allowing approximate subcellular calibration. The absolute accuracy of this approach relies upon the assumption that the resting Vm is uniform throughout the cell. To our knowledge, there is no simple method to examine this question; however, potential differences could not account for the observed differences in the AP peak/gramicidin ratio in the two cell compartments we measured. The closeness of the APSYN peak with the gramicidin response clearly indicates that the peak cannot reach voltages significantly greater than 0 mV, while at cell somas the AP peak clearly significantly exceeds 0 mV. We cannot directly measure if gramicidin brings Vm to 0 mV at boutons as previously reported at neuronal soma (Maric et al., 1998); however, the slight bias in gramicidin selectivity for K+ ions would likely lead to an overestimate of the magnitude of the response and therefore not alter our conclusions. Furthermore if the resting Vm in nerve terminals was significantly lower than that at cell somas, it would imply that the absolute magnitude of APSYN is undersestimated but not alter our conclusion that the peak does not significantly exceed 0 mV. Our observations that KV1/KV3 channel blockade leads to a significant increase in peak height (>30%) strongly implies that the APSYN peak must normally lie well below the Na+ reversal potential at synaptic boutons. Finally, numerical estimates of how these waveforms would influence VGCC gating shows that our independent measurements of synaptic Ca2+ were best explained by lower-amplitude APSYN waveforms (Figures 5F and 7C).

Our findings that the AP peak at en passant synapses (7 mV) lies far below optimal value for maximum open probability of Ca2+ channels (~40 mV) stands in contrast to classic studies in the squid stellate ganglion, a giant nerve terminal that carries out a flight response. Measurements of Ca2+ influx and presynaptic AP waveforms in the squid giant synapse demonstrated that at its peak APSYN reaches a value that will open virtually all available synaptic VGCC, albeit with a low driving force for Ca2+ influx, thus driving large Ca2+ currents during the falling phase of the AP (Augustine et al., 1985; Katz and Miledi, 1967; Llinás et al., 1981). We speculate that the main difference may simply be due to a lower relative Na+ channel density in the en passant boutons studied here. Indeed, at other giant synapses where APSYN reaches high positive values, the AP appears to be boosted by specific preterminal Na+ enrichments (Leão et al., 2005; Engel and Jonas, 2005; Hu and Jonas, 2014). Interestingly, these latter synapses share a common feature with squid stellate ganglion: they contain multiple active zones and usually discharge a large quantity of vesicles upon activation. Under these conditions, the influence of KV channels on Ca2+ influx is more modest, since it only controls the duration that VGCCs are open, in agreement with computational estimates based on detailed kinetic models of calcium channel opening (Bischofberger et al., 2002). Thus, action potentials that are dominated by NaV are very reliable transducers of electrical signaling but at the expense of modulation of the waveform and, in turn, Ca2+ influx. Our measurements were made in dissociated cultures of hippocampal neurons that lose the inherent circuit architecture found in vivo. Such conditions may therefore make comparisons with recordings in more intact systems difficult. However, recordings of somatic AP waveforms in acute hippocampal slices report AP shapes very similar to the values we report here (Meeks et al., 2005).

Functional Consequences of Low-Voltage Action Potentials

We speculate that many neurons in the brain with small en passant synapses and single active zones that dominate the hippocampus and cortex are optimized for much greater modulation of Ca2+ influx by relying on a predominance of KV channels and the resulting lower-amplitude APs. Interestingly, we found two conditions impacted the peak of APSYN that were accompanied by changes in Ca2+ influx, consistent with our low-voltage AP model. In the first case, blockade of KV3.1 and KV1.1 led to an ~30% increase in APSYN amplitude and an ~300% increase in Ca2+ influx. This increase was in excellent agreement with independent numerical simulations of Ca2+ influx with waveforms whose amplitudes change from +7 to + 28 mV in addition to the observed changes in FWHM. In the second case, overexpression of α2δ led to decreases in APSYN amplitude and FWHM that led to ~45% decreases in Ca2+ influx, despite the ~30% increase in presynaptic VGCC abundance (see below). We found that the two dominant channels that dictate AP waveform in the synapse were the fast-activating KV1 and KV3 channels. These channels are classically low- and high-voltage activated, respectively, and it is therefore surprinsing that both seem to constrain the APSYN peak. This suggests that the activation threshold for Kv3 channels in the axon may be lower than that reported from recordings in cell somas or nonneuronal cells.

Adaptive Plasticity in the APSYN Waveform

Modifications in APSYN upon α2δ manipulation may represent a way to maintain Pr in a useful operating range when VGCC numbers are altered. We previously found that α2δ expression resulted in closer coupling of VGCCs to release sites, which alone would have driven increases in Pr. Our experiments show that such changes also drive compensatory changes in APSYN, resulting in higher Pr with less total Ca2+ influx. These changes in APSYN are entirely eliminated by KV3.1/KV1.1 blockade. We further used the KV3.1/KV1.1 blockade to measure Ca2+ entry since this separates changes associated with different APs. We conclude that although overexpression of α2δ can almost triple the total abundance of CaV2.1, it likely only leads to an ~30% increase in surface VGCCs, while suppression of α2δ expression leads to an ~40% decrease (assuming no significant impact of these conditions on VGCC gating). These studies imply that the ability to increase the surface abundance of VGCCs is limited. The molecules and mechanisms that set this limit are currently unknown, but the experimental paradigm introduced here should prove useful in future molecular investigations.

The availability of robust optical tools allowed us to investigate unique features or the presynaptic AP waveform that revealed several consequential principles: (1) the presynaptic AP peak amplitude is much smaller than that measured at the soma; (2) this amplitude allows a wider range of modulation of the waveform and AP-driven Ca2+ entry; and (3) the presynaptic waveform displays adaptive plasticity in response to changes in VGCC abundance. We expect that the approaches developed here to investigate the control of presynaptic action potentials will prove indispensable for further molecular dissection of Ca2+ channel function in the presynaptic milieu.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Culture

Hippocampal CA1–CA3 regions were dissected with dentate gyrus removed from ~36 hr-old Sprague-Dawley rats, dissociated (bovine pancreas trypsin; 5 min at room temperature [RT]), and plated onto polyornithine-coated cover-slips inside a 6-mm diameter cloning cylinder as previously described (Hoppa et al., 2012). Calcium phosphate-mediated gene transfer was used to transfect 7-day-old cultures with the described plasmids (below) as previously described (Ariel and Ryan, 2010). Sprague-Dawley rats met with the approval of Weill Cornell Institutional Review.

Plasmids

Arch-GFP was acquired from Addgene (Plasmid 22217: FCK-Arch-GFP) and cotransfected at a 5:4 ratio with other cDNA. “Dark-Arch,” which contains a TYG-to-GGG mutation in the eGFP chromophore that reduces the quantum yield, was kindly provided by A. Cohen (Harvard University). The vGlut-pHluorin construct is as previously described (Balaji and Ryan, 2007). Physin-GCaMP3 was kindly provided by Loren Looger. GFP-Archaerhodopsin-3 (Arch) Plasmid and Arch-EEQ mutant were acquired from Addgene. The TeTx LC sequence was PCR amplified from a plasmid kindly provided by M. Dong (Harvard Medical School) and inserted into a pcDNA3 vector. shRNAs for rat KV1.1 and KV3.1b were based on the following sequences: rat KV1.1, TAGTTCTCCTAACTTAGCCTCTGACAGTG; rat KV3.1b, ACCTTC GAGTTCCTCATGCGTGTTGTCTT. These sequences were provided in host vectors from OriGene USA.

Live-Cell Imaging and Stimulation Conditions

All experiments were performed at 30°C using a custom-built objective heater. Coverslips were mounted in a rapid-switching, laminar-flow perfusion and stimulation chamber on the stage of a custom-built laser-scanning confocal microscope. The total volume of the chamber was ~75 μl and was perfused at a rate of 400 μl/min. During imaging, cells were continuously perfused in a standard saline solution containing the following in mM: 119 NaCl, 2.5 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 2 MgCl2, 25 HEPES (buffered to pH 7.4), 30 glucose, 10 μM 6-cyano-7-nitroquinoxaline-2,3-dione (Research Biochemicals), and 50 μM D,L-2-amino-5-phosphonovaleric acid (Research Biochemicals). TTX was used at a concentration of 300 nM (Alomone Labs). Iberiotoxin (IBX), Tetrodotoxin (TTX), Conotoxin MVIIC (Cono), and Dendrotoxin-K (DTX) were supplied by Alomone Labs. All toxins were kept as 1000× stock solutions in water for no more than 30 days stored at −20°C before use. Tetraethylammonium chloride (TEA) was procured from Sigma and stored at RT. Working concentrations were as follows: 100 nM for IBX, 300 nM for TTX, 3 μM for Cono, 100 nM for DTX, and 1 mM for TEA. All toxins were applied for 2 min (except iberiotoxin, which was applied for 5 min) before any measurements in live-cell experiments. Chemicals were purchased from Sigma, except where noted.

Timing between TTX application and washout experiments was ~8 min. For all measurements of APSYN, we used a three-part selection criteria to select region of interest (ROI) for APSYN measurement. First, all our measured boutons were >300 μm from the soma and included distinct tiny swellings (<2 μm diameter) indicative of en passant boutons. Second, we engaged in three rounds of trial averaging before, during, and after application of TTX. We only proceeded in our measurements if there was TTX sensitivity as well as a full recovery of spike firing after TTX washout to validate the measured spikes at action potential waveforms. As a third criteria, we also assayed shape and stability of the axon over these trials with termination of experiments if there was any swelling or large movement of the axon over the recording period.

Stimulus Control

Action potentials were evoked by passing 1 ms current pulses, yielding fields of ~12 V/cm (unless otherwise noted) through the chamber via Platinum/Iridium electrodes. For averaging across many trials in Arch recordings, the stimulus was locked to defined frame number intervals using a custom-built 14-bit hardware counter. Unless otherwise noted, trial averaging of AP waveforms were derived from 390 stimuli delivered at ~8 Hz. For lower time resolution experiments (vGlut-pHluorin, GCamP3) stimuli were controlled through software counting via a USB-DAQ (Texas Instruments; NI-DAQ mx 6501) programmed in Labview.

Wide-Field Imaging

Specimens of Archaerhodopsin-transfected neurons were illuminated by a 637 nm laser 140 mW (Coherent OBIS Laser) with HQ620/60× and 660LP dichroic (Chroma) through a 40× 1.3 NA Zeiss Fluar Objective and a custom beam expander to provide an ~25 μm diameter spot with a final power density of ~2,250 W/cm2. Archaerhodopsin fluorescent emission was collected through a HQ700/75 m filter (Chroma) and captured with an IXON3 897 camera (Andor) in a cropped sensor mode (10 MHz readout, 500 ns pixel shift speed) to achieve 2 kHz frame rate imaging (exposure time of 485 μs) over an 85 × 27 pixel area with the use of an intermediate image plane mask (Optomask, Cairn Research) to prevent light exposure of nonrelevant pixels. Light was collected through an HQ700/75 m filter (Chroma). Measurements using vGlut-pHluorin were measured as previously described (Ariel and Ryan, 2010). For combined measurements of pHluorin and Arch, we used a custom set of optical filters made by Chroma, with a zet488/640 dichroic and dual-band excitation filter 500/60 and 620/60×. Solid-state diode pumped 488 or 561 nm lasers (both 100 mW; Coherent Sapphire) that were shuttered using acousto-optic tunable filters. Light was collected through a zet405/488/640 m filter (Chroma). For all combined pHluorin and Arch experiments, an additional 514/30 emission filter was inserted into the optical pathway to block any possible light contamination from strong 640 nm illumination. For these experiments, fluorescent emission was captured at 1 kHz for increased field of view. Optical measurements of Ca2+ using linearization of GCaMP3 and measurements of exocytosis using vGlut-pHluorin were achieved as previously described (Hoppa et al., 2012). Briefly, GCaMP3 fluorescence was collected with an exposure time of 49.72 ms and images acquired at 20 Hz, while pHluorin fluorescence was collected with an exposure time of 18.72 ms acquired at 50 Hz. Combined measurements of ArchDARK and Fluo5F were acquired at 1 kHz using identical filter sets as described for vGpH and Arch above. After finding a responsive axonal branch expressing VAMP-mOrange2 with boutons for firing action potentials, the dish was loaded with Fluo5F-AM dye (1 μg/ml) for 10 min at 30°C and then washed with perfusion with standard Tyrodes saline as described above for 20 min. Ca2+ Influx and AP waveform were then measured using time-locked stimulation.

Local Calibration of Arch Fluorescence

Local calibration of Arch was achieved by measuring the change in fluorescence (ΔF/F) of cell somas or presynaptic boutons in response to application of gramicidin (G5002, Sigma). Gramicidin stock solution was prepared by dissolving in MeOH (10 mg/ml) stored at 4°C. Stock was added to a saline solution containing (in mM) 156 NaCl, 2 KCl, 10 HEPES (pH 7.1), 10 glucose, 10 μM CNQX, 50 μM AP-5, with a final gramicidin concentration of 200 μg/ml. In order to increase measurement accuracy, we increased the imaging area to 100 × 40 pixels and an exposure time of 975.6 μs (1 kHz acquisition). The response was determined from the average fluorescence over 3 s of data in the plateau region of the response. As gramicidin is permeant to monovalent cations, this should collapse Vm to 0 mV. To obtain an approximate calibration, we assumed the resting potential prior to gramicidin application was −65 mV, which is in agreement with most measurements and is expected from the Goldman Hodgkin Katz equation with intracellular concentrations of the following (in mM): 140 K+, 20 Na+, 18 Cl−; with associated permeabilities (p) of 1.0:0.05:0.45 for pK+:pNa+:pCl−, respectively. These data indicate that at boutons the effective sensitivity of Arch provides a change in fluorescence (ΔF/F) corresponding to 0.63%/mV, while at cell somas it was 0.24%/mV.

Image and Data Analysis

Images were analyzed in ImageJ (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij) by using custom-written plugins (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/plugins/time-series.html). Stimulation with 300 nM TTX was used to isolate the field stimulation from AP signal and was subtracted from our AP recordings at the soma and bouton. ΔF/F values of the AP were calculated after background subtraction. Measurements of background were measured using a square 10 × 10 pixel ROI. Finally, AP waveforms were corrected for the temporal resolution of Arch by deconvolution using an FFT-based algorithm in Origin Pro 8 with a normalized 500 μs exponential response function. Automated peak and FWHM analyses were carried out using Origin Pro 8’s peak-fitting algorithm. To determine the FWHM of AP waveforms in individual trials, spline fitting (Matlab, Mathworks) using a cubic smoothing B-spline to interpolate between frames at an over-sampled time resolution of 10 μs was used.

Immunofluorescence and Quantification

To quantify the efficiency of shRNA-mediated KD, neurons were fixed for 10 min with 1% paraformaldehyde and blocked with TBS containing 4% nonfat dry milk and 0.3% Triton X-100 for 30 min and incubated with the primary antibody at 1:1,000 in TBS with 4% nonfat dry milk at 4°C overnight. Alexa 488-, Alexa 546-, and Alexa 647-conjugated secondary antibodies were applied in primary antibody incubated samples with different color combinations as needed. Immunofluorescence images of fixed cells were acquired using an epifluorescence microscope with an EMCCD camera. Expression levels of KV1 were measured using an anti-KV1.1 antibody (NeuroMab, UC Davis/NIH) at cell bodies corrected for background in surrounding regions to avoid possible spatial overlap with other cells. This was compared to the fluorescence intensity in nontransfected (GFP-negative) cell bodies.

Numerical Simulation of Calcium Influx for Different AP Waveforms

The multistate model of the closed and open states of VGCCs at nerve terminals (states Sn, where n = 0–4 are closed states and n = 5 is an open state) (Li et al., 2007) as described by the following: for n = 0, dSn(t)/dt = −k+n(V)*Sn + k−n+1(V)*Sn+1(t); for n = 1–3, dSn(t)/dt = k+n−1(V)*Sn−1(t) − k−n(V)*Sn(t) −k+n(V)*Sn + k−n+1(V)*Sn+1(t); for n = 4, dSn(t)/dt = k+n−1(V)*Sn−1(t) − k−n(V)*Sn(t) − k+n*Sn + k−n+1*Sn+1(t); for n = 5 (open state), dO(t)/dt = k+4*S4(t)−k−o*O(t); where for n = 0–3, k+n(V) = αne(V(t)/Vn); for n = 4, k+4 = α4; for n = 1–4, k−n(V) = βne(−V(t)/Vn); and for n = 5, k−5 = β5.

These differential equations were integrated numerically with a fourth-order Runge-Kutta method in Berkeley Madonna with V(t) defined by the different AP waveforms as described. The results are plotted as the integrated value of Ca influx, where Ca(t) = (55 mv − V(t))* (0.8*OCav2.2(t) + 0.2*OCav2.1(t)).

The different channel contributions were taken as 80% N-type (Cav2.2) and 20% P-type (Cav2.1) using the gating parameters as determined in Li et al. (2007), and an effective reversal potential of 55 mV was assumed. We adjusted the rate constants determined in Li et al. (2007) for the fact that our measurements are carried out at 30°C while the gating measurements were carried out at 23°C. A temperature factor of two was therefore used in all rate constants.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Daniel Hochbaum and Adam Cohen (Harvard University) for supplying Dark Arch cDNA and helpful conversation for its use. We thank Julia Marrs for assistance preparing DNA plasmids and cell culture assistance. We would like to thank members of the Ryan lab and Jeremy Dittman for discussions. This work was supported by grants from the NIH (MH085783) to T.A.R. and the Revson Foundation (M.B.H.).

Footnotes

Supplemental Information includes five figures and can be found with this article online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2014.09.038.

References

- Abdul-Ghani MA, Valiante TA, Pennefather PS. Sr2+ and quantal events at excitatory synapses between mouse hippocampal neurons in culture. J Physiol. 1996;495:113–125. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alle H, Roth A, Geiger JR. Energy-efficient action potentials in hippocampal mossy fibers. Science. 2009;325:1405–1408. doi: 10.1126/science.1174331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alle H, Kubota H, Geiger JR. Sparse but highly efficient Kv3 outpace BKCa channels in action potential repolarization at hippocampal mossy fiber boutons. J Neurosci. 2011;31:8001–8012. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0972-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ariel P, Ryan TA. Optical mapping of release properties in synapses. Front Neural Circuits. 2010:4. doi: 10.3389/fncir.2010.00018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ariel P, Hoppa MB, Ryan TA. Intrinsic variability in Pv, RRP size, Ca(2+) channel repertoire, and presynaptic potentiation in individual synaptic boutons. Front Synaptic Neurosci. 2012;4:9. doi: 10.3389/fnsyn.2012.00009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Augustine GJ, Charlton MP, Smith SJ. Calcium entry and transmitter release at voltage-clamped nerve terminals of squid. J Physiol. 1985;367:163–181. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1985.sp015819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balaji J, Ryan TA. Single-vesicle imaging reveals that synaptic vesicle exocytosis and endocytosis are coupled by a single stochastic mode. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:20576–20581. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707574105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bean BP. The action potential in mammalian central neurons. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8:451–465. doi: 10.1038/nrn2148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bischofberger J, Geiger JR, Jonas P. Timing and efficacy of Ca2+ channel activation in hippocampal mossy fiber boutons. J Neurosci. 2002;22:10593–10602. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-24-10593.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borst JG, Sakmann B. Calcium current during a single action potential in a large presynaptic terminal of the rat brainstem. J Physiol. 1998;506:143–157. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1998.143bx.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borst JG, Sakmann B. Effect of changes in action potential shape on calcium currents and transmitter release in a calyx-type synapse of the rat auditory brainstem. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1999;354:347–355. doi: 10.1098/rstb.1999.0386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boudkkazi S, Fronzaroli-Molinieres L, Debanne D. Presynaptic action potential waveform determines cortical synaptic latency. J Physiol. 2011;589:1117–1131. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.199653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley J, Luo R, Otis TS, DiGregorio DA. Submillisecond optical reporting of membrane potential in situ using a neuronal tracer dye. J Neurosci. 2009;29:9197–9209. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1240-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debanne D, Campanac E, Bialowas A, Carlier E, Alcaraz G. Axon physiology. Physiol Rev. 2011;91:555–602. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00048.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng PY, Rotman Z, Blundon JA, Cho Y, Cui J, Cavalli V, Zakharenko SS, Klyachko VA. FMRP regulates neurotransmitter release and synaptic information transmission by modulating action potential duration via BK channels. Neuron. 2013;77:696–711. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodge FA, Jr, Rahamimoff R. Co-operative action a calcium ions in transmitter release at the neuromuscular junction. J Physiol. 1967;193:419–432. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1967.sp008367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engel D, Jonas P. Presynaptic action potential amplification by voltage-gated Na+ channels in hippocampal mossy fiber boutons. Neuron. 2005;45:405–417. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.12.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forsythe ID, Barnes-Davies M. The binaural auditory pathway: membrane currents limiting multiple action potential generation in the rat medial nucleus of the trapezoid body. Proc Biol Sci. 1993;251:143–150. doi: 10.1098/rspb.1993.0021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foust AJ, Yu Y, Popovic M, Zecevic D, McCormick DA. Somatic membrane potential and Kv1 channels control spike repolarization in cortical axon collaterals and presynaptic boutons. J Neurosci. 2011;31:15490–15498. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2752-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong B, Liu M, Qi Z. Membrane potential dependent duration of action potentials in cultured rat hippocampal neurons. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2008;28:49–56. doi: 10.1007/s10571-007-9230-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong Y, Li JZ, Schnitzer MJ. Enhanced Archaerhodopsin Fluorescent Protein Voltage Indicators. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e66959. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutman GA, Chandy KG, Grissmer S, Lazdunski M, McKinnon D, Pardo LA, Robertson GA, Rudy B, Sanguinetti MC, Stühmer W, Wang X. International Union of Pharmacology. LIII Nomenclature and molecular relationships of voltage-gated potassium channels. Pharmacol Rev. 2005;57:473–508. doi: 10.1124/pr.57.4.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hille B. Ion channels of excitable membranes. 3. Sunderland, Mass., U.S.A: Sinauer; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Hodgkin AL, Huxley AF. A quantitative description of membrane current and its application to conduction and excitation in nerve. J Physiol. 1952;117:500–544. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1952.sp004764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoppa MB, Lana B, Margas W, Dolphin AC, Ryan TA. α2δ expression sets presynaptic calcium channel abundance and release probability. Nature. 2012;486:122–125. doi: 10.1038/nature11033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu H, Jonas P. A supercritical density of Na(+) channels ensures fast signaling in GABAergic interneuron axons. Nat Neurosci. 2014;17:686–693. doi: 10.1038/nn.3678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston J, Forsythe ID, Kopp-Scheinpflug C. Going native: voltage-gated potassium channels controlling neuronal excitability. J Physiol. 2010;588:3187–3200. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2010.191973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz B, Miledi R. A study of synaptic transmission in the absence of nerve impulses. J Physiol. 1967;192:407–436. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1967.sp008307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kole MH, Letzkus JJ, Stuart GJ. Axon initial segment Kv1 channels control axonal action potential waveform and synaptic efficacy. Neuron. 2007;55:633–647. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.07.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kralj JM, Douglass AD, Hochbaum DR, Maclaurin D, Cohen AE. Optical recording of action potentials in mammalian neurons using a microbial rhodopsin. Nat Methods. 2012;9:90–95. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leão RM, Kushmerick C, Pinaud R, Renden R, Li GL, Taschenberger H, Spirou G, Levinson SR, von Gersdorff H. Presynaptic Na+ channels: locus, development, and recovery from inactivation at a high-fidelity synapse. J Neurosci. 2005;25:3724–3738. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3983-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Bischofberger J, Jonas P. Differential gating and recruitment of P/Q-, N-, and R-type Ca2+ channels in hippocampal mossy fiber boutons. J Neurosci. 2007;27:13420–13429. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1709-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Llinás R, Steinberg IZ, Walton K. Presynaptic calcium currents in squid giant synapse. Biophys J. 1981;33:289–321. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(81)84898-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maclaurin D, Venkatachalam V, Lee H, Cohen AE. Mechanism of voltage-sensitive fluorescence in a microbial rhodopsin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:5939–5944. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1215595110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maric D, Maric I, Smith SV, Serafini R, Hu Q, Barker JL. Potentiometric study of resting potential, contributing K+ channels and the onset of Na+ channel excitability in embryonic rat cortical cells. Eur J Neurosci. 1998;10:2532–2546. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1998.00284.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meeks JP, Jiang X, Mennerick S. Action potential fidelity during normal and epileptiform activity in paired soma-axon recordings from rat hippocampus. J Physiol. 2005;566:425–441. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.089086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meunier FM. Relationship between presynaptic membrane potential and acetylcholine release in synaptosomes from Torpedo electric organ. J Physiol. 1984;354:121–137. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1984.sp015367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mintz IM, Sabatini BL, Regehr WG. Calcium control of transmitter release at a cerebellar synapse. Neuron. 1995;15:675–688. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90155-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitterdorfer J, Bean BP. Potassium currents during the action potential of hippocampal CA3 neurons. J Neurosci. 2002;22:10106–10115. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-23-10106.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller M, Davis GW. Transsynaptic control of presynaptic Ca2+ influx achieves homeostatic potentiation of neurotransmitter release. Curr Biol. 2012;22:1102–1108. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.04.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peterka DS, Takahashi H, Yuste R. Imaging voltage in neurons. Neuron. 2011;69:9–21. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podleski T, Changeux JP. Effects associated with permeability changes caused by gramicidin A in electroplax membrane. Nature. 1969;221:541–545. doi: 10.1038/221541a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popovic MA, Foust AJ, McCormick DA, Zecevic D. The spatio-temporal characteristics of action potential initiation in layer 5 pyramidal neurons: a voltage imaging study. J Physiol. 2011;589:4167–4187. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.209015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pumplin DW, Reese TS, Llinás R. Are the presynaptic membrane particles the calcium channels? Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1981;78:7210–7213. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.11.7210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowan MJ, Tranquil E, Christie JM. Distinct Kv channel subtypes contribute to differences in spike signaling properties in the axon initial segment and presynaptic boutons of cerebellar interneurons. J Neurosci. 2014;34:6611–6623. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4208-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabatini BL, Regehr WG. Timing of neurotransmission at fast synapses in the mammalian brain. Nature. 1996;384:170–172. doi: 10.1038/384170a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabatini BL, Regehr WG. Control of neurotransmitter release by presynaptic waveform at the granule cell to Purkinje cell synapse. J Neurosci. 1997;17:3425–3435. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-10-03425.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiavo G, Benfenati F, Poulain B, Rossetto O, Polverino de Laureto P, DasGupta BR, Montecucco C. Tetanus and botulinum-B neurotoxins block neurotransmitter release by proteolytic cleavage of synaptobrevin. Nature. 1992;359:832–835. doi: 10.1038/359832a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneggenburger R, Neher E. Intracellular calcium dependence of transmitter release rates at a fast central synapse. Nature. 2000;406:889–893. doi: 10.1038/35022702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scimemi A, Diamond JS. The number and organization of Ca2+ channels in the active zone shapes neurotransmitter release from Schaffer collateral synapses. J Neurosci. 2012;32:18157–18176. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3827-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smart SL, Lopantsev V, Zhang CL, Robbins CA, Wang H, Chiu SY, Schwartzkroin PA, Messing A, Tempel BL. Deletion of the K(V)1.1 potassium channel causes epilepsy in mice. Neuron. 1998;20:809–819. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)81018-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storm JF. Action potential repolarization and a fast after-hyperpolarization in rat hippocampal pyramidal cells. J Physiol. 1987;385:733–759. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1987.sp016517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi T, Momiyama A. Different types of calcium channels mediate central synaptic transmission. Nature. 1993;366:156–158. doi: 10.1038/366156a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taschenberger H, von Gersdorff H. Fine-tuning an auditory synapse for speed and fidelity: developmental changes in presynaptic waveform, EPSC kinetics, and synaptic plasticity. J Neurosci. 2000;20:9162–9173. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-24-09162.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wheeler DB, Randall A, Tsien RW. Roles of N-type and Q-type Ca2+ channels in supporting hippocampal synaptic transmission. Science. 1994;264:107–111. doi: 10.1126/science.7832825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu M, Cao R, Xiao R, Zhu MX, Gu C. The axon-dendrite targeting of Kv3 (Shaw) channels is determined by a targeting motif that associates with the T1 domain and ankyrin G. J Neurosci. 2007;27:14158–14170. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3675-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.