Summary

Fibroblast activation protein (FAP) has long been known to be expressed in the stroma of breast cancer. However, very little is known if the magnitude of FAP expression within the stroma may have prognostic value and reflect the heterogeneous biology of the tumor cell. An earlier study had suggested that stromal FAP expression in breast cancer was inversely proportional to prognosis. We, therefore, hypothesized that stromal FAP expression may correlate with clinicopathologic variables and may serve as an adjunct prognostic factor in breast cancer. We evaluated the expression of FAP in a panel of breast cancer tissues (n=52) using a combination of immunostain analyses at the tissue and single cell level using freshly frozen or freshly digested human breast tumor samples respectively. Our results showed that FAP expression was abundantly expressed in the stroma across all breast cancer subtypes without significant correlation with clinicopathologic factors. We further identified a subset of FAP positive or FAP+ stromal cells that also expressed CD45, a pan-leukocyte marker. Using freshly dissociated human breast tumor specimens (n=5), we demonstrated that some of these FAP+ CD45+ cells were CD11b+CD14+MHC-II+ indicating that they were likely tumor associated macrophages (TAMs). Although FAP+CD45+ cells have been demonstrated in the mouse tumor stroma, our results demonstrating that human breast TAMs expressed FAP was novel and suggested that existing and future FAP directed therapy may have dual therapeutic benefits targeting both stromal mesenchymal cells and immune cells such as TAMs. More work is needed to explore the role of FAP as a potential targetable molecule in breast cancer treatment.

1. Introduction

Although cancer drug development has traditionally targeted tumor cells, emphasis is beginning to shift towards inclusion of the tumor microenvironment for discovery of novel therapeutic approaches [1]. Among the cellular components in the tumor microenvironment, various non-immune cells such as stromal mesenchymal cells have emerged as critical players in promoting tumor proliferation, neovascularization, invasion, and metastasis [2]. As cancer stromal cells lack the genetic instability that is characteristic of tumor cells, they may exhibit a reduced capacity for development of drug resistance and immune escape and are, therefore, appropriate targets for drug development, complementing and, likely, enhancing efficacy of conventional cancer therapy.

Cancer associated fibroblasts (CAFs) are one of the most common stromal cell types within the tumor. These CAFs characteristically adopt spindle-shaped cell morphology when placed in culture and express fibroblast markers such as fibroblast specific protein (FSP) [3], α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA), and fibroblast activation protein (FAP) [4–7]. FAP is a homodimeric integral membrane serine proteinase. Unlike FSP and other common fibroblast markers, FAP is a cell-surface protein rendering it a targetable molecule whereby novel therapeutic strategies that either 1) inhibit the FAP function (i.e. protease activity), or 2) deplete cells that express FAP within the tumor microenvironment have shown promising anti-tumor effects [8–12]. Therefore, in this study, we sought to characterize the expression pattern of FAP in a cohort of breast cancer with heterogeneous characteristics to determine whether the expression of FAP within breast cancer stroma may correlate with conventional prognostic factors and thus have prognostic value. Our hypothesis was based on a previous study that suggested that FAP expression in breast cancer was inversely correlated with breast cancer prognosis [13].

Using immunohistochemistry (IHC) to characterize FAP expression in a panel of breast cancer samples (n=52), we found that FAP was abundantly expressed in the vast majority (85.4 ± 13.8%) of stromal cells in all of our tumor samples [13]. We did not observe significant correlation between the levels of FAP expression and clinicopathologic variables in this study. Further characterization of these FAP expressing stromal cells revealed a subpopulation that also expressed CD45, a pan-leukocyte marker. Using flow cytometry to analyze single cell suspensions derived from freshly procured human breast cancer samples, we demonstrated that some of these FAP+CD45+ cells also expressed markers for macrophages including CD14, CD11b, CD114 and HLA-DR, suggesting that some of these FAP+CD45+ cells may represent tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs). Our finding that TAMs express FAP suggested that existing targeted strategies against FAP [9–12, 14–18] may have dual effects against stromal fibroblasts and TAMs.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Patients and Clinical Characteristics of Study Cohort

Women with newly diagnosed breast cancer undergoing breast cancer surgery at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania were asked to participate in a tissue bank protocol that had been approved by our Institutional Review Board. Our study cohort included 52 patients treated at our institution between 2008 and 2011. Breast tumors were stratified into three subgroups according to receptor expression: Group 1 was comprised of hormone receptor (HR) positive or HR+ breast cancer which is defined by the expression of either estrogen receptor (ER) or progesterone receptor (PR) and lacks Her2-neu (Her2) expression (n=25); Group 2 (n=7) was comprised of Her2-neu positive or Her2+ breast cancer which expressed Her2-neu as determined by IHC and/or fluorescence in situ hybridization with (n=2) or without expression (n=5) of ER or PR; and group 3 was comprised of TNBC which lacked expression of ER, PR, or Her2 (n=20). To ensure a balanced proportion of the less common TNBC which typically represents only about 20% of all diagnosed breast cancer patients, we included all banked TNBC (n=20) from our entire banked tumor samples during our study period 2008 – 2011. We then included 25 unselected consecutively banked ER+ breast cancers and 7 Her2+ breast cancers in our analyses. All data collection and analyses were adherent to Institutional Review Board approved protocols.

2.2. Immunohistochemistry analyses

ER, PR, and Her2 expression were evaluated by standard IHC staining techniques on formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded (FFPE) breast cancer tissue samples for all participants as part of standard pathology evaluation at our institution. The FDA approved PharmDx ER and PR test kits and HercepTest (DAKO, Carpinteria, CA) were used to evaluate ER, PR and Her2 expression strictly following the manufacturers’ guidelines on formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded section at the time of the routine pathologic evaluation of the surgical specimen. The tests were reported as negative if Allred score was 2 or less for ER and PR and 0 or 1+ for Her2. Only cases with sufficient tumor tissue were studied. Fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) was performed using PathVision HER2 DNA probe kit (Abbott, Late County, IL) on all TNBC and cases with Her2 2+ equivocal results on IHC to evaluate HER2 amplification. No Her2 amplification (HER2/CEP17 ratio <1.8) was detected in any TNBC in our series.

For evaluation of FAP, α-SMA, EpCAM, and CD45 expression, IHC was performed using cryostat sections (8 μm thick) of freshly frozen tumor tissues embedded in OCT. The sections were fixed with acetone at −20°C for 15 min and air-dried at room temperature for 15 min. Endogenous peroxidases were quenched with 0.3% hydrogen peroxide/PBS washes. Tissue sections were blocked with normal goat serum and then with Avidin and Biotin. Primary antibody or isotype matched controls in 3% (w/v) bovine serum albumin was applied to tissues at concentration of 10 μg/ml at room temperature for 50 minutes. Sections were then incubated with appropriate secondary antibodies, washed, and incubated with diaminobenzidine and counterstained with hematoxylin. Staining results were evaluated by our pathologists, who were blinded to the clinical characteristics of the tumor tissues. Quantification of FAP expression on IHC was scored by 3 parameters: 1) proportion of stromal cells with positive stain (%) calculated as the mean % of (+) stromal cells from 3 high-power fields; 2) intensity of the stain (1+, 2+, 3+), and 3) H score (0–300) as the product of % positive tumor cells and intensity as described in a previous study [19]. Antibodies used in our IHC analyses included EpCAM (clone 9C, biolegend), CD45 (clone F10–89–4, Serotec), and FITC conjugated anti-αSMA (Clone 1A4, Sigma). Anti-human FAP (Clone F19) [4, 5, 20] was purified from hybridoma supernatants as described [5, 16, 21].

2.3. Tissue dissociation and flow cytometry analyses

Breast cancer tissue excised at the time of surgery was sent without delay to pathology laboratory where our surgical pathologists conducted gross examination and inking of the tumor specimen. Under the supervision of the surgical pathologist on duty, tumor tissue was taken from the center of the tumor and normal breast tissue was taken from normal tissue away from the tumor proper with special attention to ensure that proper margin assessment was achieved. For studies involving normal breast tissue obtained from women undergoing reduction mammoplasty, the tissues were also immediately sent to pathology laboratory for gross examination. A small portion of normal breast tissue was procured and processed for our studies while the remaining breast tissues were subjected to routine pathology evaluation.

The fresh tumor tissues were stored in ice cold DMEM/F12 medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), penicillin and streptomycin and kept on ice at 4°C until ready to be processed (within 4 hours from the time of excision). Samples were minced into 1-mm fragments using scissors and/or scalpels and digested using type I collagenase at 1 mg/ml (Sigma) in PBS for 1h at 37 °C. Dissociated cells were filtered through a 70 m nylon strainer, pelleted and subjected to flow cytometry analyses. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells were obtained by leukapheresis/elutriation, as described [22], and stained in parallel with freshly dissociated tumor samples. Flow cytometry was performed on an LSRII (BD Biosciences, San Jose), using three anti-FAP antibodies: polyclonal rabbit anti-human FAP antibody (Abcam); polyclonal sheep anti-human FAP antibody (R&D), and mouse monoclonal anti-human FAP antibody (F19) [5, 16, 21], plus appropriate secondary antibodies. Samples were stained along with the following anti-human antibodies CD14, CD45 (HI30), CD11b (ICRF44), HLA-DR (L243) and CD114 (LMM741), which were all purchased from Biolegend. Propidium iodide (PI) was used to exclude dead cells and flow cytometry analyses were performed and compared with isotype-matched controls.

2.4 Statistical analysis

Clinical characteristics, including age at diagnosis, histologic types (ductal vs. lobular), tumor size, tumor grade, and number of involved (+) axilla nodes were compared. Pair-wise comparison was done using two-tail t-test for age and tumor size, and fisher exact test for histologic types, tumor grade (II vs. III) and number of (+) axilla nodes (none vs. one or more). Continuous variables including tumor size and number of positive nodes, the intensity and % distribution of FAP and α-SMA in the stroma were compared and Pearson correlation coefficients were computed. The Spearman correlation coefficients were also computed for ordinal variables (tumor subtype and tumor grade). Two-tailed p-value was computed when the correlation coefficient was significantly different from 0.

3. Results

3.1. FAP is a robust stromal cell marker regardless of breast cancer subtypes

An earlier study using archival breast cancer tissues had reported that a lower level of FAP expression was associated with a worse clinical outcome [13]. These results suggested that FAP expression in breast cancer stroma is heterogeneous and may correlate with clinicopathologic factors such as tumor size, tumor grade, axilla nodal involvement and tumor subtypes. Among these prognostic markers, we are particularly interested in the possible correlation of FAP expression and specific tumor subtypes, in particular TNBC. If such correlation exists, FAP may represent a potentially targetable molecule especially for tumor subtype that lacks targeted therapy such as TNBC. We, therefore, evaluated the expression of FAP in a breast cancer cohort that was stratified into three major breast cancer subtypes as described in the method section. The clinical characteristics of the study cohort across the three subtypes were listed in Table 1 and were noted to be similar except for tumor size and tumor grade (Table 1). Women with Her2+ and TNBC breast cancer had significantly larger tumors and higher tumor grade (p=0.0221 and 0.000642 respectively) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics of breast cancer study cohort

| Overall | HR+ | Her2+ | TNBC | p-value (ANOVA) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 52 | 25 | 7 | 20 | |

|

| |||||

| Age at diagnosis | 54 ± 16 | 56 ± 17 | 53 ± 15 | 52 ± 15 | 0.669 |

|

| |||||

| Histology | |||||

| Invasive ductal carcinoma invasive lobular | 49 | 24 | 6 | 19 | |

| carcinoma | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| ductal carcinoma in situ | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

|

| |||||

| Tumor size (cm) | 3.7 ± 2.9 | 3.2 ± 1.6 | 6.4 ± 6.2 | 3.3 ± 1.7 | 0.0221 |

| mean ± standard deviation | |||||

| T1< 2 cm | 12 | 7 | 1 | 4 | |

| T2 2.1 – 5 cm | 31 | 14 | 3 | 14 | |

| T3> 5 cm | 9 | 4 | 3 | 2 | |

|

| |||||

| Tumor grade | 7.5 ± 1.3 | 6.8 ± 1.3 | 7.4 ± 1.1 | 8.4 ± 0.8 | 0.0006418 |

| I | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | |

| II | 17 | 13 | 3 | 1 | |

| III | 26 | 8 | 2 | 16 | |

| not assessed | 6 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

|

| |||||

| No. of involved axilla node(s) | 3.4 ± 5.1 | 4.1 ± 5.3 | 3.0 ± 3.1 | 2.6 ± 5.5 | 0.6289 |

| 0 | 18 | 5 | 2 | 11 | |

| 1–2 | 13 | 8 | 1 | 4 | |

| 3–5 | 9 | 5 | 2 | 2 | |

| ≥6 | 10 | 6 | 1 | 3 | |

| not assessed | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | |

|

| |||||

| Receptor status | |||||

| ER+ | 27 | 25 | 2 | 0 | |

| PR+ | 21 | 21 | 0 | 0 | |

| Her2+ | 7 | 0 | 7 | 0 | |

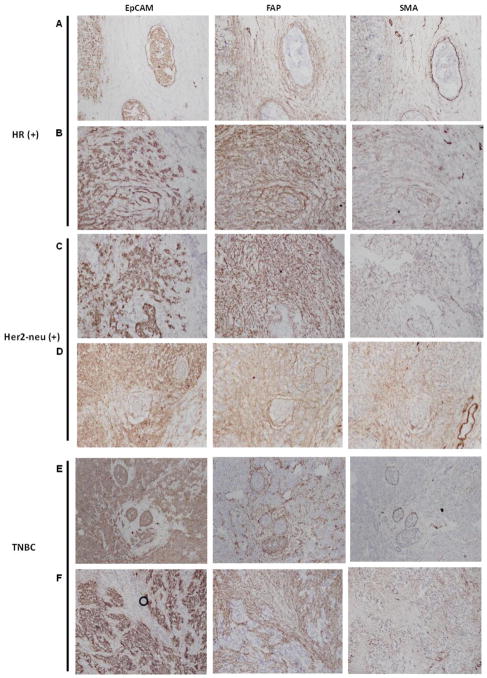

IHC analyses were then performed using consecutive tissue sections from each of our 52 tumor samples so as to compare the expression and distribution of two stromal cell markers, FAP and α-SMA, and an epithelial cell marker, EpCAM, within the tumor parenchyma. Representative IHC results from each breast cancer subtype were shown in Fig. 1. The tumor stroma was easily identified since stromal cells were strongly stained by FAP whereas tumor epithelial cells were strongly stained by EpCAM. We observed that FAP was abundantly expressed in the stromal cells in all three breast cancer subtypes while the expression of α-SMA within the stroma appeared less abundant and more variable (Fig. 1). The proportion of stromal cells (%) staining positive for FAP and α-SMA were quantified and tabulated along with the intensity of IHC stain (1, 2 and 3 in ascending degree of intensity) and the H-score (defined as the product of % and intensity) (Table 2). FAP was abundantly expressed in > 70% of stromal cells in 46 of 52 tumor samples. Overall, the mean proportion of tumor stromal cells staining positive for FAP was 85.4 ± 13.8% while a smaller proportion (29.6 ± 30.3%) of tumor stromal cells stained positive for α-SMA. Comparison of the % stromal distribution of FAP and α-SMA across subtypes did not yield any significant correlation. In addition, univariate and multivariate analyses were performed to compare the stromal cell distribution and staining intensity of FAP and α-SMA across other prognostic variables such as tumor size, grade and number of positive (affected) axilla lymph nodes. Univariate analyses results (p-values) were summarized in Table 3. Only the intensity of FAP IHC staining significantly correlated with tumor grade in univariate analysis (p-value = 0.02091369) (Table 3) and in multivariate analysis (p-value = 0.01264) (data not shown). Overall, our results demonstrated that higher tumor grade (a poor prognostic factor) was associated with stronger FAP IHC stain intensity. However, the proportion (%) of stromal cells staining positive for FAP or α-SMA did not correlate with any other conventional clinicopathologic factors examined in this study.

Figure 1. Evaluation of EpCAM (epithelial cell marker), FAP, and α-SMA expression by IHC in three breast cancer subtypes (HR+, Her2+ and TNBC) as described in the method section.

Each row represents IHC results from a unique breast cancer sample. Rows A & B: representative IHC staining patterns in HR+ breast cancer; rows C & D: representative IHC staining patterns in Her2+ breast cancer; Rows E & F: representative IHC staining patterns in TNBC. Of note, circle in Row F under EpCam is an artifact caused by a trapped air bubble.

Table 2.

Stromal distribution of FAP and α-SMA according to tumor subtypes

| overall | HR+ | Her2 + | TNBC | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n=52 | n= 25 | n=7 | n=20 | ||

| (mean ± standard deviation) | |||||

| FAP | |||||

| % (+) stroma cells | 85.4±13.80 | 86.2 ± 12.7 | 85.0 ± 18.7 | 84.4 ± 14.8 | 0.9193 |

| intensity (1+, 2+, 3+) | 2.2±0.48 | 2.2 ± 0.5 | 2.0 ± 0.0 | 2.4 ± 0.5 | 0.06241 |

| H-score (%*intensity) | 193.5±58.22 | 186.8 ± 54.1 | 170 ± 37.4 | 210.6 ± 66.8 | 0.2443 |

| SMA | |||||

| % (+) stroma cells | 29.6±30.28 | 30.4 ± 33.1 | 44.2 ± 25.0 | 24.3 ± 27.7 | 0.3697 |

| intensity (1+, 2+, 3+) | 1.4±0.80 | 1.4 ± 0.9 | 1.7 ± 0.5 | 1.3 ± 0.8 | 0.625 |

| H-score (%*intensity) | 57.8±66.37 | 60.8 ± 75.3 | 84.2 ± 55.7 | 46.25 ± 56.9 | 0.4573 |

Table 3.

p-values from univariate analyses comparing distribution of stroma markers with tumor size, grade and number of positive axilla nodes

| Tumor size | Tumor Grade (p-values) | No. of Positive nodes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| FAP | |||

| % (+) stroma cells | 0.5321779 | 0.9267936 | 0.8469087 |

| intensity | 0.3043792 | 0.02091369 | 0.4374885 |

| index | 0.2874708 | 0.2510948 | 0.5105135 |

| SMA | |||

| % (+) stroma cells | 0.2103918 | 0.5844424 | 0.4965176 |

| intensity | 0.1741343 | 0.3084001 | 0.4909281 |

| index | 0.2483643 | 0.4972089 | 0.5173598 |

3.2. A subset of FAP+ tumor stromal cells co-expressed CD45 and markers for macrophages

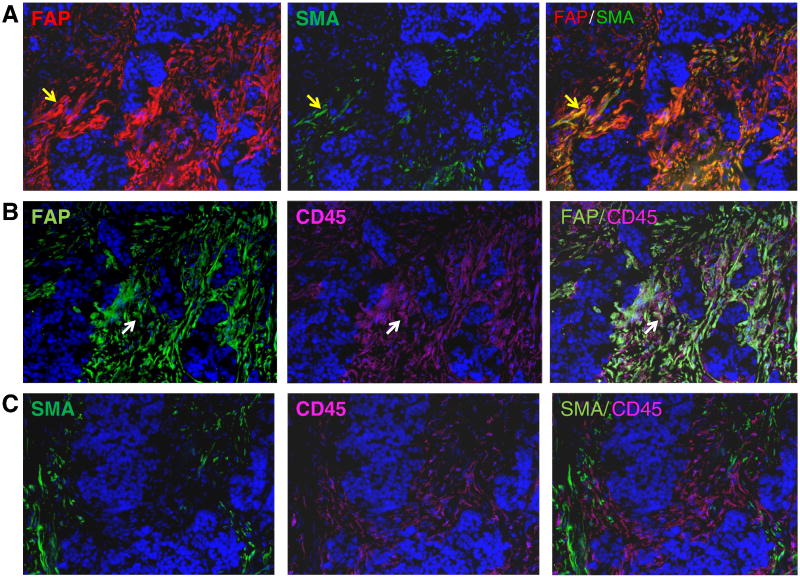

Our results demonstrated that over 85% of stromal cells expressed FAP while only ~30% of stromal cells expressed α-SMA and suggested that the majority of these stromal cells were not myofibroblasts since they lacked α-SMA expression. To further characterize these FAP+ stromal cells, we stratified them based on the presence or absence of α-SMA expression into 3 subsets: 1) FAP+ α-SMA+, 2) FAP+ α-SMA−, and 3) FAP− α-SMA+ and performed additional immunoflourescence staining using a third antibody against CD45, to help discern leukocytes from other cellular components within the stroma. Consecutive tumor tissue sections were stained with the following antibodies that were linked to three different fluorochromes: anti-FAP (red), anti-α-SMA (green), and anti-CD45 (pink). As shown in Fig. 2, double positive FAP+α-SMA+ stromal cells were easily identified within the stroma as depicted by cells that were stained yellow due to the overlapping of both red and green fluorochromes in the same cell (yellow arrow, Fig. 2, Row A). FAP- α-SMA+ stromal cells, i.e. cells which would only be stained green by anti-α-SMA were not identified in this tumor section. When we performed double staining using anti-FAP and anti-CD45 antibodies in serial consecutive tumor sections from the same tumor, we noted that abundant stromal cells were stained positive by CD45 and that a subset of these stromal cells were stained positive for both FAP and CD45, i.e. FAP+CD45+, as depicted by cells staining white (white arrow, Fig. 2, Row B). In addition, we noted that there was no colocalization of CD45 and α-SMA in any stromal cells in this particular tumor sample (Fig. 2, Row C). Our results indicated that double positive FAP+CD45+ cells most likely lacked α-SMA expression since none of the CD45+ cells exhibited α-SMA expression in this tumor sample (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Co-localization of FAP, SMA, and CD45 expression within breast cancer stroma by immunofluorescent (IF) staining.

All three rows represent IF results in consecutive tissue sections from the same breast cancer tissue sample. Row A, dual color IF staining of breast cancer stroma with FAP (red) and SMA (green) identified a subset of stromal cells that were double positive (yellow) as depicted by yellow arrow. Row B, dual color IF staining of breast cancer stroma with FAP (green) and CD45 (pink) identified a subset of stromal cells that were double positive (white) as depicted by white arrow. Row C, dual color IF staining of breast cancer stroma with SMA (green) and CD45 (pink) demonstrated that very few stromal cells, if any, co-expressed both SMA and CD45.

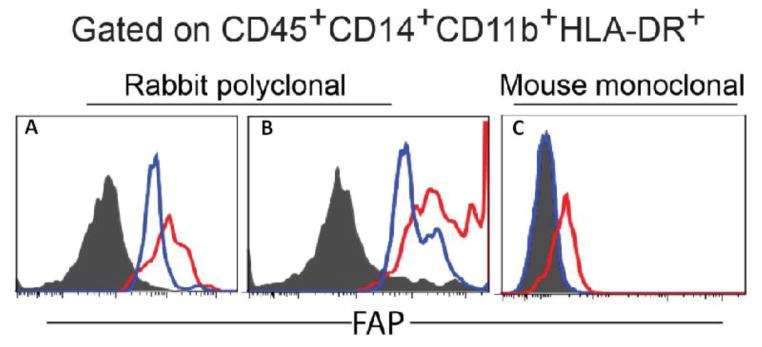

These FAP+CD45+ stromal cells were further characterized by staining single cell suspensions derived from freshly dissociated tumor samples (n=5) with a panel of leukocyte lineage markers and analyzed using multi-parameter flow cytometry. Anti-FAP antibodies, along with a panel of leukocyte cell surface markers including CD45, CD14, CD11b, HLA-DR, and CD114, were used to stain freshly dissociated human breast tumor cells. After gating for CD45, CD14, CD11b and HLA-DR expression, we observed that there was a subset of tumor-derived cells that expressed FAP as detected by rabbit polyclonal anti-FAP antibody (Fig. 3A & B). Similar results were obtained using a mouse monoclonal anti-FAP antibody, F19 (Fig. 3C) and sheep polyclonal anti-FAP antibody (R&D) (supplementary Fig. 1). FAP expression was also demonstrated in a small subset of monocytes in peripheral blood but expression of which was weaker than the presumed tumor associated macrophages derived from human breast cancer. Our results indicated that a subset of CD45+ cells derived from human breast cancer expressed FAP along with common markers of macrophages, i.e. CD14, CD11b, and HLA-DR, suggesting that they may be TAMs.

Figure 3. Tumor-associated macrophages expressed FAP.

FAP expression in CD45+CD14+CD11b+HLA-DR+ macrophages was examined in freshly dissociated single cell suspension of three different human breast cancer specimens, using peripheral blood from 3 different healthy donors as controls and two different anti-FAP antibodies. Panels A & B depict flow cytometry histogram results using polyclonal rabbit anti-human FAP (AbCAM) as the primary antibody to detect FAP expression in two different human breast cancer samples; Secondary antibody used was donkey anti-rabbit antibody (Jackson ImmunoResearch). Open blue, histogram of peripheral blood macrophages from different donors; open red, histogram of individual tumor sample depicting the presence of FAP+ tumor associated macrophages; solid grey, secondary antibody alone. For panel C, primary antibody used was PE-conjugated F19 mouse monoclonal anti-human FAP. Open blue, histogram of peripheral blood macrophages from a third donor; open red, histogram of a third tumor sample again depicting the presence of FAP+ tumor-associated macrophages; solid grey, unstained.

4. Discussion

As there is mounting evidence to support the concept that FAP plays a critical role in the tumor microenvironment, [10, 12, 23], there has been much interest in exploiting FAP as a therapeutic target specific for the tumor microenvironment [9, 11, 17, 24]. In addition to its relative specific expression within the tumor stroma, the expression of FAP may have prognostic value as demonstrated in a 2010 study [23] that identified a stromal gene signature whereby overexpression of any one of the five genes, including FAP, was associated with worse outcome in human esophageal adenocarcinoma. Whether FAP has similar prognostic significance in breast cancer is yet to be determined.

As FAP expression within the breast cancer stroma has been shown to be heterogeneous and may have prognostic value [13], we hypothesize that the level of FAP expression within the stroma may correlate with conventional clinicopathologic variables including tumor size, grade, number of involved lymph nodes, and breast cancer subtypes and may reflect the heterogeneous biology of the tumor cells. A significant correlation between FAP and breast cancer subtype, if it exists, may be clinically relevant since FAP directed therapy may be considered in tumors that exhibit higher level of FAP expression. However, our results showed that the proportion of stromal cells staining positive for FAP on IHC was consistently high at 85.4 ± 13.8% across all three breast cancer subtypes (Table 2). Whereas in the 2001 study [13], it was concluded that abundant FAP stromal expression was associated with better prognosis, our results, however, demonstrated that a higher FAP IHC intensity significantly correlated with higher tumor grade, a prognostic factor known to be associated with worse prognosis, in both univariate (Table 3) and multivariate analyses (not shown). Although our results cannot be directly compared with the 2001 study, our results appeared to, but not necessarily, contradict the 2001 study especially since we lacked long-term follow up data in this study.

Our discordant results may be attributed to two major differences in methodology: 1) Archival formalin fixed paraffin embedded (FFPE) tumor tissues were predominantly used in the 2001 study to correlate FAP expression with breast cancer outcome while fresh frozen OCT embedded tumor sections were used sparingly to validate FAP expression within the stroma in a limited number of cases. In contrast, all of our analyses were carried out on freshly frozen OCT embedded breast cancer tissues. The use of archival vs. fresh frozen tumor tissue sections may have contributed to the differences in IHC staining results; and 2) the anti-FAP antibody used in our study was a mouse monoclonal anti-FAP antibody, F19 [5, 20], while the 2001 study mainly used a rat anti-seprase monoclonal antibodies [25] in their archival tumor set (n=115). The F19 antibody was used on a smaller subset of fresh tumor samples for validation. As the specificity of anti-FAP antibodies have been shown to be highly variable especially when FFPE tissue sections were used [26], we, from the outset of our study, restricted our analyses to freshly frozen breast tumor tissues embedded in OCT to avoid the specificity issues that are anticipated with FFPE tissues.

Further characterization demonstrated that the majority of the FAP+ stromal cells lacked α-SMA expression. In addition, some of these FAP+ cells also expressed CD45 (Fig. 2), a pan-leukocyte marker, which suggested that some of these FAP+CD45+ cells may either be 1) fibrocytes that are known to express FAP and are derived from bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells which were recently shown to express FAP [18]; or 2) leukocytes. Multi-parametric flow cytometry analyses using a panel of leukocyte markers identified a subpopulation of FAP+CD45+ cells within the tumor that co-expressed CD14 (Fig. 3), a marker of macrophages but not fibrocytes [27, 28]. This subset of FAP+CD45+ cells also expressed CD11b, HLA-DR (Fig. 3) and CD114 (supplementary Fig) which are markers typically expressed by macrophages suggesting that at least some of these FAP+CD45+ cells may be TAMs.

To the best of our knowledge, human TAMs were not known to express FAP until this study although the presence of FAP+CD45+ cells have been reported in mouse tumors [12]. A recent study demonstrated that the abrogation of FAP+CD45+ cells in a mouse tumor model resulted in stunted tumor growth. These FAP+CD45+ cells were presumably fibrocytes. However, our data suggested that at least a portion of these FAP+CD45+CD14+ cells could be bonafide immune leukocytes, i.e. TAMs. Therefore, ablation of FAP+ cells may have resulted in the abrogation of stromal fibrocytes and/or TAMs resulting in the observed anti-tumor effects in these mouse models. Since stromal cells and TAMs have both been shown to promote tumor growth through multiple mechanisms that may include immune suppression, it may be of interest in the future to determine whether the growth inhibitory effects observed previously [12] could be attributed to the ablation of FAP+CD45− mesenchymal stromal cells that are presumably fibrocytes or FAP+CD45+CD14+ that are presumably TAMs, or both.

In conclusion, our results suggest that FAP is abundantly expressed in breast cancer stroma and that drugs that target FAP may not only target stromal mesenchymal cells but may also target TAMs within the tumor microenvironment. More work is needed to dissect the role of FAP in various subpopulations within the tumor microenvironment.

Supplementary Material

FAP expression in HLA-DR+ CD114+ macrophages was examined in freshly dissociated single cell suspension of human breast cancer using R&D polyclonal sheep-anti-human FAP (huFAP) antibody as the primary antibody (panel A). Isotype-matched control, sheep IgG is shown in panel B. The spectrum is overlaid to show FAP expression (red tinted) relative to the isotype-matched control (blue).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Tumor Tissue and Biospecimen Bank (TTAB) of the Abramson Cancer Center, Perelman School of Medicine of University of Pennsylvania, for assisting in tumor tissue collection. This research was, in part, funded by the NCI Cancer Center Support Grant (2-P30-CA-016520-35) (J. Tchou), the Linda and Paul Richardson Breast Cancer Research Funds (J. Tchou), 2013 Exceptional Project Award from the Breast Cancer Alliance (J. Tchou), PHS grant RO1CA141144 (E. Puré), Ludwig Institute for Cancer Research (E. Puré) and a START fellowship from the Cancer Research Institute (A. Lo).

Footnotes

Competing interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Author’s contributions

J. Tchou, J. Conejo-Garcia and E. Puré designed the study; J. Tchou, P Zhang, YT Bi, C Satija, R Marjumdar, TL Stephen, A Lo, HY Chen, C Mies, and J Conejo-Garcia performed the experiments described in this study; J. Tchou, TL Stephen, A Lo, J Conejo-Garcia, C. H. June, and E. Puré contributed to the writing of the manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Pardoll D, Drake C. Immunotherapy earns its spot in the ranks of cancer therapy. J Exp Med. 2012;209:201–209. doi: 10.1084/jem.20112275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sugimoto H, Mundel TM, Kieran MW, Kalluri R. Identification of fibroblast heterogeneity in the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Biol Ther. 2006;5:1640–1646. doi: 10.4161/cbt.5.12.3354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rettig WJ, Garin-Chesa P, Healey JH, Su SL, Ozer HL, Schwab M, Albino AP, Old LJ. Regulation and heteromeric structure of the fibroblast activation protein in normal and transformed cells of mesenchymal and neuroectodermal origin. Cancer Res. 1993;53:3327–3335. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rettig WJ, Su SL, Fortunato SR, Scanlan MJ, Raj BK, Garin-Chesa P, Healey JH, Old LJ. Fibroblast activation protein: purification, epitope mapping and induction by growth factors. Int J Cancer. 1994;58:385–392. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910580314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Levy MT, McCaughan GW, Abbott CA, Park JE, Cunningham AM, Muller E, Rettig WJ, Gorrell MD. Fibroblast activation protein: a cell surface dipeptidyl peptidase and gelatinase expressed by stellate cells at the tissue remodelling interface in human cirrhosis. Hepatology. 1999;29:1768–1778. doi: 10.1002/hep.510290631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Park JE, Lenter MC, Zimmermann RN, Garin-Chesa P, Old LJ, Rettig WJ. Fibroblast activation protein, a dual specificity serine protease expressed in reactive human tumor stromal fibroblasts. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:36505–36512. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.51.36505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Loeffler M, Kruger JA, Niethammer AG, Reisfeld RA. Targeting tumor-associated fibroblasts improves cancer chemotherapy by increasing intratumoral drug uptake. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:1955–1962. doi: 10.1172/JCI26532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.LeBeau AM, Brennen WN, Aggarwal S, Denmeade SR. Targeting the cancer stroma with a fibroblast activation protein-activated promelittin protoxin. Mol Cancer Ther. 2009;8:1378–1386. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-1170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Santos AM, Jung J, Aziz N, Kissil JL, Pure E. Targeting fibroblast activation protein inhibits tumor stromagenesis and growth in mice. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:3613–3625. doi: 10.1172/JCI38988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wen Y, Wang CT, Ma TT, Li ZY, Zhou LN, Mu B, Leng F, Shi HS, Li YO, Wei YQ. Immunotherapy targeting fibroblast activation protein inhibits tumor growth and increases survival in a murine colon cancer model. Cancer Sci. 2010;101:2325–2332. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2010.01695.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kraman M, Bambrough PJ, Arnold JN, Roberts EW, Magiera L, Jones JO, Gopinathan A, Tuveson DA, Fearon DT. Suppression of antitumor immunity by stromal cells expressing fibroblast activation protein-alpha. Science. 2010;330:827–830. doi: 10.1126/science.1195300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ariga N, Sato E, Ohuchi N, Nagura H, Ohtani H. Stromal expression of fibroblast activation protein/seprase, a cell membrane serine proteinase and gelatinase, is associated with longer survival in patients with invasive ductal carcinoma of breast. Int J Cancer. 2001;95:67–72. doi: 10.1002/1097-0215(20010120)95:1<67::aid-ijc1012>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adams S, Miller GT, Jesson MI, Watanabe T, Jones B, Wallner BP. PT-100, a small molecule dipeptidyl peptidase inhibitor, has potent antitumor effects and augments antibody-mediated cytotoxicity via a novel immune mechanism. Cancer Res. 2004;64:5471–5480. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hofheinz RD, al-Batran SE, Hartmann F, Hartung G, Jager D, Renner C, Tanswell P, Kunz U, Amelsberg A, Kuthan H, Stehle G. Stromal antigen targeting by a humanised monoclonal antibody: an early phase II trial of sibrotuzumab in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Onkologie. 2003;26:44–48. doi: 10.1159/000069863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mersmann M, Schmidt A, Rippmann JF, Wuest T, Brocks B, Rettig WJ, Garin-Chesa P, Pfizenmaier K, Moosmayer D. Human antibody derivatives against the fibroblast activation protein for tumor stroma targeting of carcinomas. Int J Cancer. 2001;92:240–248. doi: 10.1002/1097-0215(200102)9999:9999<::aid-ijc1170>3.0.co;2-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Narra K, Mullins SR, Lee HO, Strzemkowski-Brun B, Magalong K, Christiansen VJ, McKee PA, Egleston B, Cohen SJ, Weiner LM, Meropol NJ, Cheng JD. Phase II trial of single agent Val-boroPro (Talabostat) inhibiting Fibroblast Activation Protein in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Cancer Biol Ther. 2007;6:1691–1699. doi: 10.4161/cbt.6.11.4874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tran E, Chinnasamy D, Yu Z, Morgan RA, Lee CC, Restifo NP, Rosenberg SA. Immune targeting of fibroblast activation protein triggers recognition of multipotent bone marrow stromal cells and cachexia. J Exp Med. 2013;210:1125–1135. doi: 10.1084/jem.20130110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tchou J, Wang LC, Selven B, Zhang H, Conejo-Garcia J, Borghaei H, Kalos M, Vondeheide RH, Albelda SM, June CH, Zhang PJ. Mesothelin, a novel immunotherapy target for triple negative breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012;133:799–804. doi: 10.1007/s10549-012-2018-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garin-Chesa P, Old LJ, Rettig WJ. Cell surface glycoprotein of reactive stromal fibroblasts as a potential antibody target in human epithelial cancers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990;87:7235–7239. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.18.7235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Welt S, Divgi CR, Scott AM, Garin-Chesa P, Finn RD, Graham M, Carswell EA, Cohen A, Larson SM, Old LJ, et al. Antibody targeting in metastatic colon cancer: a phase I study of monoclonal antibody F19 against a cell-surface protein of reactive tumor stromal fibroblasts. J Clin Oncol. 1994;12:1193–1203. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1994.12.6.1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cubillos-Ruiz JR, Martinez D, Scarlett UK, Rutkowski MR, Nesbeth YC, Camposeco-Jacobs AL, Conejo-Garcia JR. CD277 is a negative co-stimulatory molecule universally expressed by ovarian cancer microenvironmental cells. Oncotarget. 2010;1:329–338. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Saadi A, Shannon NB, Lao-Sirieix P, O’Donovan M, Walker E, Clemons NJ, Hardwick JS, Zhang C, Das M, Save V, Novelli M, Balkwill F, Fitzgerald RC. Stromal genes discriminate preinvasive from invasive disease, predict outcome, and highlight inflammatory pathways in digestive cancers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:2177–2182. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909797107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cheng JD, Cohen SJ, Stzempkowski-Brun B, Magalong K, Christiansen VJ, McKee PA, Alpaugh RK, Lee H, Weiner LM, Meropol NJ. Phase II pharmacodynamic study of the fibroblast activation protein inhibitor Val-boro-Pro in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2006;24:3594. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pineiro-Sanchez ML, Goldstein LA, Dodt J, Howard L, Yeh Y, Tran H, Argraves WS, Chen WT. Identification of the 170-kDa melanoma membrane-bound gelatinase (seprase) as a serine integral membrane protease. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:7595–7601. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.12.7595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jacob M, Chang L, Pure E. Fibroblast activation protein in remodeling tissues. Curr Mol Med. 2012;12:1220–1243. doi: 10.2174/156652412803833607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Abe R, Donnelly SC, Peng T, Bucala R, Metz CN. Peripheral blood fibrocytes: differentiation pathway and migration to wound sites. J Immunol. 2001;166:7556–7562. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.166.12.7556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pilling D, Fan T, Huang D, Kaul B, Gomer RH. Identification of markers that distinguish monocyte-derived fibrocytes from monocytes, macrophages, and fibroblasts. PLoS One. 2009;4:e7475. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

FAP expression in HLA-DR+ CD114+ macrophages was examined in freshly dissociated single cell suspension of human breast cancer using R&D polyclonal sheep-anti-human FAP (huFAP) antibody as the primary antibody (panel A). Isotype-matched control, sheep IgG is shown in panel B. The spectrum is overlaid to show FAP expression (red tinted) relative to the isotype-matched control (blue).