Abstract

Background

People with opioid dependence and HIV are concentrated within criminal justice settings (CJS). Upon release, however, drug relapse is common and contributes to poor HIV treatment outcomes, increased HIV transmission risk, reincarceration and mortality. Extended-release naltrexone (XR-NTX) is an evidence-based treatment for opioid dependence, yet is not routinely available for CJS populations.

Methods

A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of XR-NTX for HIV-infected inmates transitioning from correctional to community settings is underway to assess its impact on HIV and opioid-relapse outcomes.

Results

We describe the methods and early acceptability of this trial. In addition we provide protocol details to safely administer XR-NTX near community release and describe logistical implementation issues identified. Study acceptability was modest, with 132 (66%) persons who consented to participate from 199 total referrals. Overall, 79% of the participants had previously received opioid agonist treatment before this incarceration. Thus far, 65 (49%) of those agreeing to participate in the trial have initiated XR-NTX or placebo. Of the 134 referred patients who ultimately did not receive a first injection, the main reasons included a preference for an alternative opioid agonist treatment (37%), being ineligible (32%), not yet released (10%), and lost upon release before an receiving their injection (14%).

Conclusions

Study findings should provide high internal validity about HIV and opioid treatment outcomes for HIV-infected prisoners transitioning to the community. The large number of patients who ultimately did not receive the study medication may raise external validity concerns due to XR-NTX acceptability and interest in opioid agonist treatments.

Keywords: opioid dependence, HIV, Vivitrol, prisoners, Extended-Release Naltrexone, randomized controlled trial

Introduction1

The dramatic growth in the U.S. inmate population over the last three decades has resulted from the increased detention of individuals for drug-related offenses and recidivist offenders. As a result, those with substance use disorders (SUDs) with or at risk for HIV infection are concentrated within the criminal justice system (CJS). The prevalence of HIV and AIDS is 3- and 4-fold greater, respectively, among incarcerated persons compared to the general population [1, 2]. In 2004, the U.S. Department of Justice reported that 53% of state prisoners met DSM-IV criteria for drug abuse or dependence, 56% reported regular use in the month prior to their offence, specifically, 13.1% reported using heroin and opiates [3, 4]. In a study conducted in CT, among HIV-infected prisoners with SUDs, 61% met criteria for opioid dependence [5-8].

The revolving door of prisons and jails results in 12 million people being released annually to communities, oftentimes with undiagnosed or untreated medical conditions [9]; including one-sixth of the nearly 1.2 million people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWH) [2]. Though HIV-infected prisoners markedly reduce HIV-1 RNA levels and achieve markedly high levels viral suppression (VS) during incarceration due to the availability of combination antiretroviral therapy (cART) and the structure of the facilities [10-12], these benefits are lost soon after release [10, 13, 14], especially due to drug and alcohol relapse [15], especially heroin. The negative consequences of opioid relapse for HIV-infected patients include poor retention in care [14, 16-18], cART adherence [5, 6] and increased recidivism to prison/jail [19, 20]. This, is in addition to the increased early mortality risk upon release [21-26], mostly associated with opioid overdose [22, 25-27], affirms the need for evidence-based transitional interventions.

According to the International Association of Physicians in AIDS Care (IAPAC) guidelines, only directly administered antiretroviral therapy (DAART) is effective for transitioning HIV-infected prisoners [28]. One randomized controlled trial (RCT) of DAART for released prisoners, however, showed that for the subset meeting criteria for opioid dependence, those retained on buprenorphine post-release markedly increased their likelihood of achieving VS [7, 8], suggesting that medication-assisted therapies (MATs) might be a more effective and less costly strategy for released prisoners with HIV and opioid dependence. Despite there being three FDA-approved pharmacological treatments for opioid dependence, methadone (MMT), buprenorphine (BMT) and extended-release naltrexone (XR-NTX), with rare exception, have they not been empirically tested as transitional care for released prisoners [29-33]. Despite preliminary successes using MAT among HIV seronegative subjects [31, 32, 34, 35], these treatments have not been deployed systematically within the CJS [36-39] nor deployed to optimize HIV treatment, as recommended by the IAPAC for PLWH and SUDs in the community [28].

As part of the National Institute of Drug Abuse’s (NIDA) initiative to examine the impact of the seek, test, treat, and retain model of care (STTR) for criminal justice populations [40], this study directly examines the ability of XR-NTX to effectively “treat and retain” opioid dependent prisoners through the post-release transitional period. To test whether XR-NTX effectively stabilizes patients through this precarious post-release period, we have implemented a novel double-blind, placebo-controlled RCT of XR-NTX among opioid dependent HIV-infected prisoners and jail detainees transitioning to the community, with an examination of both HIV and substance abuse treatment outcomes.

Methods

Study Design

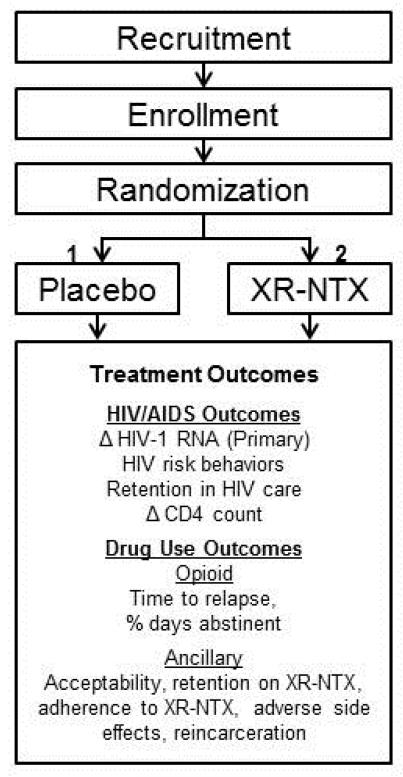

Project NEW HOPE (Needing Extended-release Wellness Helping Opioid dependent People Excel) is a multi-site, double-blind, placebo-controlled RCT of XR-NTX among opioid dependent HIV-infected prisoners and jail detainees transitioning to the community. The study design is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Study Design

Ethical Oversight

Institutional Review Boards (IRB) at Yale University, Waterbury Hospital and Baystate Medical Center, and research committees at Hampden County Correctional Centers (HCCC) and the Connecticut Department of Correction (CTDOC) reviewed and approved all study procedures. The study is registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov (NCT01246401). Additional protections were provided by the Office of Human Research Protections (OHRP) at the Department of Health and Human Services and a Certificate of Confidentiality (CoC) was obtained.

Research Goals

Given the high rate of relapse to opioid use upon release [41] and its association with poor HIV treatment outcomes [15, 42], this study’s aim is to examine if using an evidence-based treatment for opioid dependence improves HIV and substance abuse treatment outcomes in the post-release period. Outcomes include HIV-related outcomes (HIV-1 RNA levels, including VS, CD4 count, cART adherence, retention in HIV care); substance abuse outcomes (time to opioid relapse, percent of opioid negative urine screens, opioid craving); recidivism and re-arrests; adverse side effects; and HIV risk behaviors (sexual and drug-related risks). The primary outcome is the proportion achieving VS (HIV-1 RNA<400 copies/mL) 6 months post-release. Additional detail regarding the outcomes of interest can be found in the Analytical Plan section.

Sample Size and Power Calculations

Sample size calculations were based on the primary outcome of the proportion of participants who achieve VS 6 months after release, based on 2:1 randomization; increased allocation to the XR-NTX arm was justified to assess for adverse side effects. Sample size requirements for a Type I error rate of 0.05 and power of 80% estimated by preliminary data from our prison-release data suggests that approximately 60% of inmates leave prison with VS [10]. Of note, more recent data suggest that VS upon release is 70% [12]. Using an intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis and assuming a baseline VS of 60% [10], 150 subjects would be required for a difference of 25% between the two treatment arms if randomized 2:1 (XR-NTX=100 and placebo=50).

Study Procedures

Recruitment and Screening

Recruitment started in 2011 and will continue until 2015 in all prisons and jails by Infectious Disease Nurses (IDN), who coordinate all HIV-related care for HIV-infected inmates. Initial study criteria includes: 1) being HIV-seropositive; 2) returning to three sites in Connecticut (New Haven, Hartford, Waterbury [2012 and 2013 only] or Massachusetts (Springfield only); 3) meets DSM-IV criteria for opioid dependence (using the Rapid Opioid Dependency Scale) based on information 12 months prior to their current incarceration [43]; 4) able to provide informed consent; 5) speaks English or Spanish; and 6) 18 years or older. Those meeting screening criteria were asked to sign a release of information (ROI) so that research staff can meet and inform them about the research study and undergo informed consent procedures. For PLWH and released to the community without being assessed, referrals from the community were allowed from HIV clinicians and drug treatment providers, case managers and through self-referrals using approved flyers and advertisements if made within 30 days of release to the community.

Eligibility Process

After receiving the ROI, Research Staff scheduled an appointment with the inmate in a confidential setting to assess additional eligibility criteria. If the inmate was eligible for the study, the study staff member described the study and enrolled the participant. Additional inclusion criteria includes: 1) not participating in a pharmacotherapy or adherence trial in the previous 30 days; and 2) within 30 days of release from prison or jail. Exclusion criteria included: 1) threatening behavior toward study staff or other participants; 2) pending federal charges; 3) prescription of opioid pain medications or expressing a need for them; 4) known hypersensitivity to naltrexone, PLG (polylactide-co-glycolide), arboxymethylcellulose, or any other components of the diluent and 5) medication contraindications that included: a) already enrolled in an opioid substitution therapy program; b) aspartate aminotransferase (AST) or alanine aminotransferase (ALT) elevations (>5x upper limit of normal); c) evidence of Child Pugh Class C cirrhosis; or d) breastfeeding, pregnant or unwilling to use contraception (women).

Informed Consent and Enrollment

Upon completion of eligibility determination, the study research member completed informed consent procedures and assessed the participant’s willingness to enroll in the study, including receiving six monthly injections, where the first was administered approximately 7 days prior to release and then attend monthly interviews over twelve months post-release. To ensure that there was no real or perceived coercion for enrollment during incarceration, all participants underwent a second written informed consent process upon release from the correctional facility to confirm their interest in study participation. For those that were referred from the community or were released unexpectedly, the initial injection was administered at the study sites after completing the baseline interview and medical chart review.

Covariate and Outcome Measures

Screening and Intervention Measures

After informed consent completion, all enrolled participants underwent baseline assessments, follow-up interviews and laboratory assessments monthly for 12 months. Please refer to Table 1 for the measures, main outcomes assessed, and the study timeline.

Table 1.

Study Activity and Measures

| Study Activity | Study Time Point in Months from Day of Release from Incarceration | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||||||

| −3 | −1 week |

0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | |

| Study Activity | |||||||||||||||

| Screening for Eligibility | × | ||||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Medical Chart Review | × | ||||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Randomization | × | ||||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Injection and Clinical Interview |

× | × | × | × | × | × | |||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Research Interview | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | |

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Demographic Information | |||||||||||||||

| Demographic Questions* | × | ||||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Housing Questions* | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × |

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Health Care Status | |||||||||||||||

| HIV quality of life (SF-12)* [71] |

× | × | × | × | × | ||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Current Medications | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | |

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Prescription Refill | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | |

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Prison Medical Record (Medication, cART regimen, HCV antibody, medication allergies) |

× | ||||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Visual Analog Scale [51] | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | |

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Previous Experience with Alcohol and Drug Treatment |

× | ||||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Mental Health | |||||||||||||||

| Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI)* [72-74] |

× | ||||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Correctional Medical Record Diagnoses |

× | ||||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Brief Symptom Inventory-18 (BSI-18) [75-77] |

× | × | × | × | × | ||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Drug and Alcohol Use | |||||||||||||||

| Rapid Opioid Dependence Screen [43] |

× | ||||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Addiction Severity Index Lite* [78-80] |

× | × | × | × | × | ||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Drug Urine Toxicology Screening |

× | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | |

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test* [54, 81-82] |

× | ||||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Timeline Recall [83, 84] | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | |

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Opioid Craving | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × |

|

| |||||||||||||||

| DSM-IV Criteria using MINI [73] |

× | ||||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Blood Alcohol Content via Breathalyzer |

× | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | ||

|

| |||||||||||||||

| HIV Risk Behaviors | |||||||||||||||

| Sexual Risk Behaviors* [85] | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | × | |

|

| |||||||||||||||

|

HIV Biological Outcome

Measures |

|||||||||||||||

| HIV-1 RNA level* | × | × | × | × | × | ||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||

| CD4 Count* | × | × | × | × | × | ||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||

| HIV genotype* | × | × | |||||||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Other Laboratory Tests | |||||||||||||||

| Liver Function Tests (AST, ALT) |

× | × | × | × | × | × | × | ||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Renal Function Tests (BUN, Creatinine) |

× | × | × | × | × | × | × | ||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Side Effects | |||||||||||||||

| Systemic Assessment for Treatment Emergent Effects Intervention (SAFTEE) [44, 86] |

× | × | × | × | × | × | × | ||||||||

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Payments | |||||||||||||||

| Research Interviews** | $20 | $20 | $20 | $20 | $40 | $20 | $20 | $40 | $30 | $30 | $60 | $30 | $30 | $60 | |

|

| |||||||||||||||

| Clinical Interviews** | $10 | $10 | $10 | $10 | $10 | $10 | |||||||||

Seek, Test, Treat & Retain Harmonized measure

Payment for interviews completed in the correctional facilities were paid after release.

Legend: cART=combination antiretroviral therapy; CJS=criminal justice system; ALT=alanine aminotransferase; AST=aspartate aminotransferase; BUN=blood urine nitrogen

Process Measures

In addition to the measures noted in Table 1, qualitative information was assessed to address:

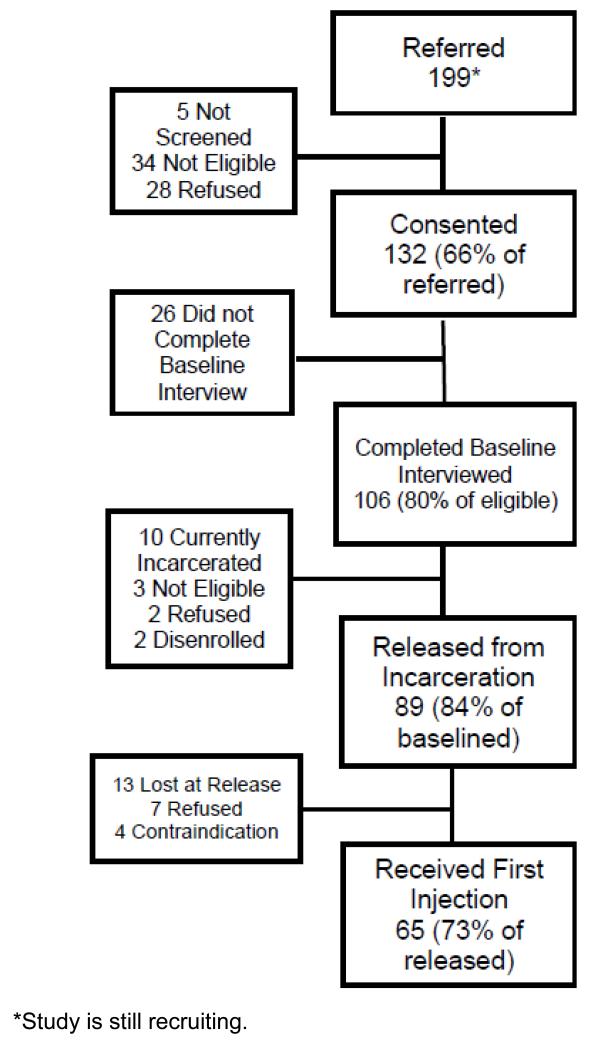

Acceptance of study involvement to determine if this injectable, long-acting opioid dependence treatment would be acceptable given the other treatments available in the community, yet not available during incarceration. Of the initial 199 participants referred to the study, 132 (66%) signed consent forms while still incarcerated. The main reason for ineligibility was not meeting criteria for opioid dependence during the screening process (47%) (Table 2). Of the 132 that signed informed consent forms, 106 (80%) completed baseline interviews, providing insight into the acceptability of involvement in this study and potentially for XR-NTX as an intervention to prevent relapse (see Figure 2).

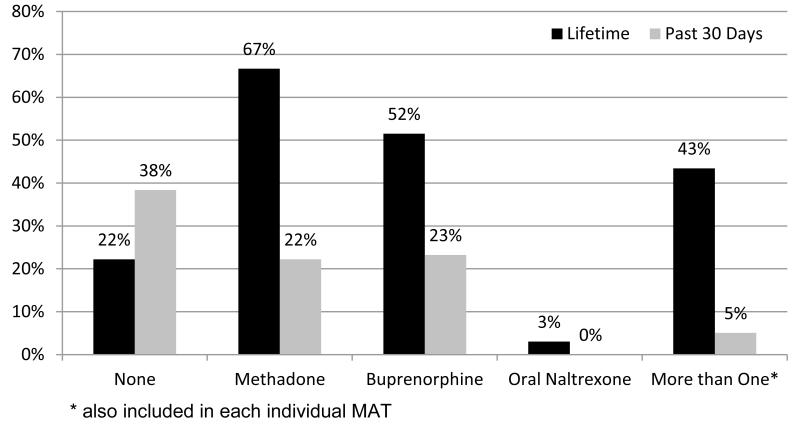

Acceptability of opioid antagonist treatment in persons with experience with opioid agonist treatments and thus evaluating whether this FDA-approved treatment will be accepted by those with experience with prior opioid agonist treatments. The main reason for refusal in the different stages of enrollment in this study was a preference for another form of MAT (34%) (Table 2). Thus far, 79% (79/100) of the participants in the study have self-reported previous experience with MMT or BMT (Figure 3).

Acceptability of injections by assessing how many participants who agree to participate in the study and complete baseline interviews will actually agree to receive an initial injection. Thus far in this on-going trial, of those who have completed baseline interviews 84% (89/106) were released from incarceration, and 73% (65/89) received their initial injection near the day of release.

Attrition from intervention, to assess whether participants will remain in the assigned study arm and adhere to the study medication, thus focusing on persistence of monthly injections in a placebo-controlled trial. For participants wishing to switch to another form of treatment, including but not limited to another form of MAT or inpatient treatment, s/he will continued to be followed for the duration of the study but will receive no further XR-NTX injections.

Tolerability and adverse event monitoring is assessed by recording the number and frequency of adverse events monitored using the Systemic Assessment For Treatment Emergent Effects Intervention (SAFTEE) [44].

Ancillary encounters, are assessed and include additional services that participants may request including clinical/medical services, counseling and case management services such as food, shelter, insurance, drug/alcohol counseling or detoxification, mental illness treatment, and medical insurance enrollment.

Constant communication with study staff at all study sites is required with CTDOC and HCCC personnel, and participants.

Table 2.

Reasons for refusal or ineligibility of study participation

| Before Initial Consent | |

|

| |

| Total Not Screened | 5 |

| Refused screening, does not want treatment | 2 |

| Released before being seen | 1 |

| Refused without a reason given | 1 |

| Not interested in participating a study | 1 |

|

| |

| Total Ineligible | 34 |

| Does not meet DSM-IV criteria for OD | 16 |

| Enrolled in another research study | 1 |

| On methadone + refused | 1 |

| Will be released out of catchment areas | 7 |

| Medical need for pain medication | 8 |

| Cirrhosis + refused | 1 |

|

| |

| Total Refused | 28 |

| Wants another form of treatment | 8 |

| Refused to sign consent - may want BMT on release | 1 |

| Study fatigue | 2 |

| Does not want injections | 1 |

| Concerned about current health issues and possible | |

| complications | 2 |

| Does not want treatment | 2 |

| Afraid of needles and does not want treatment | 1 |

| Does not want placebo | 2 |

| No reason given/not interested | 3 |

| Does not want NTX | 1 |

| No reason for refusal +Elevated LFTs | 1 |

| Released before consented, wanted to think about it | 1 |

| Refused + being released out of area | 3 |

|

| |

| After Initial Consent, Prior to release from prison | |

|

| |

| Total Disenrolled | 2 |

| Behavior issues | 1 |

| Passed away in prison (unrelated to study/health) | 1 |

|

| |

| Total Refused | 13 |

| Wants another form of treatment | 5 |

| Advised by family not to enroll, released out of area, possible | |

| need pain meds | 1 |

| Does not think he needs treatment, and will not be | |

| released early | 1 |

| Does not have time, does not need the money | 1 |

| Concerned about current health issues doesn’t want | |

| complications | 1 |

| “I don’t want to feel like a lab rat” | 1 |

| Refused - no reason given | 3 |

|

| |

| Total Ineligible | 6 |

| Liver Failure/Elevated LFTs | 2 |

| Found to be unable to consent (memory/cognition issues) |

1 |

| Cirrhosis, wants methadone & medical need for pain meds | 1 |

| On methadone | 2 |

|

| |

| After Initial Consent, After release from prison | |

|

| |

| Total Lost upon release, reasons missed injections | 13 |

| Released too quickly post referral | 1 |

| Refused injection in prison, and moved upon release | 1 |

| Released to parole unexpectedly | 3 |

| Released unexpectedly | 8 |

|

| |

| Total Refused | 7 |

| Wants another form of treatment | 3 |

| Moving out of area | 1 |

| Transportation issues | 1 |

| No reason given | 2 |

Abbreviations: OD Opioid Dependence; BMT Buprenorphine Maintenance Treatment; NTX Naltrexone; LFTs Liver Function Tests.

Figure 2.

Study Flow of Current Acceptability

Figure 3.

Previous Experience with Medication Assisted Therapy (N=99)

Randomization and Dispensing

All study medication packages (active drug and placebo) were provided and prepared by Alkermes, Inc. and randomized and dispensed by the Yale-New Haven Hospital or Baystate Medical Center Investigational Drug Service (IDS) pharmacists in a blinded manner. Participants were randomized 2:1 prior to their release from the correctional facility by the IDS pharmacist, to XR-NTX or placebo. IDS pharmacists stored, distributed and labeled study medications using participant identification numbers. To maintain the double-blinded condition of the study design, placebo microspheres were used instead of naltrexone, and vials containing the microspheres were tinted amber to mask the color differences in the solution. To control for covariates potentially associated with the outcomes, covariate adaptive randomization was used [45-47]. These covariates included: 1) community release site (greater New Haven, Hartford, or Springfield areas); and 2) being prescribed or not prescribed cART.

Intervention

Study Procedures

Injections were optimally initiated prior to correctional release, thereby introducing specific challenges and issues during the implementation process. These issues are later described in this paper and in Table 3. After release, participants are followed for 12 months, receiving an additional 5 injections and 13 interviews. Please see Table 1 for the study timeline for study and injection interviews.

Table 3.

Study Implementation Issues

| Harmonized Data Measures & Multisite Data Transfers | ||

|---|---|---|

| Obstacle | Action Taken | Knowledge Gained |

| 1) Creating interviews using harmonized data measures |

Collaboration with NIDA and 11 additional grantees on selecting and implementing harmonized measures. http://www.drugabuse.gov/researchers/research- resources/data-harmonization-projects/seek-test-treat- retain. |

Strong communication and attention to detail was needed to ensure the correct measures were collected at the appropriate times. Study participants complained that surveys were too long. |

| 2) Deidentification of data |

In order to comply with HIPAA regulations, all data were deidentified before data transfers to NIDA and from Baystate to Yale. Yale Information Technology Services (ITS) and Human Research Protection Program were consulted ensure all data transfers meet HIPAA regulations. |

Prior to data collection, Yale Human Research Protection Program policies were explored to ensure data collected for the harmonization was compliant with HIPAA regulations and ensured that all data to be transferred was deidentified as required. Each site maintained a link between study number and personal identities. |

| 3) Multisite data collection |

To ensure all data was properly protected, the Yale ITS encrypted file transfer was used on a quarterly basis to transfer data from Baystate Medical Center to Yale AIDS Program. Once the data was received into the office, it was saved on the Yale secure server. |

Collaboration from different departments within Yale University and updates of new services to safeguard protected data. Yale ITS and Baystate ITS needed to ensure that computers and programs were compatible with encryption software and interview software. |

| 4) Coordination of multiple review board review and approval |

Upon creation of the study protocol to be submitted, reviewed and approved by multiple review boards, a review of the different institutions’ policy to reduce the number of amendments and changes required before approval. Communication with Yale IRB (as primary site) to assist with coordination of federal approvals required for this vulnerable population. |

Approval from the primary institution was required before other approvals were able to be gained. Communication with the different institutions before a final protocol is submitted is essential to receive the appropriate approvals in a timely manner. This resulted in a process that approached 12 months. |

| Recruitment and Facility Staff Trainings | ||

| Obstacle | Action Taken | Knowledge Gained |

| 5) Educational sessions on medication assisted therapies |

Interactive information sessions were conducted throughout the study to inform the correctional staff of newly FDA approved injectable formulation of NTX and of other pharmacotherapies approved for the treatment of opioid dependence. Addressing concerns and questions regarding the different treatments. |

Correctional staff was updated and given a refresher of current treatments for opioid dependence. This opened another line of communication with the correctional staff. |

| Changes in Department of Corrections Policies | ||

| Obstacle | Action Taken | Knowledge Gained |

| 6) Methadone Maintenance Program in two facilities |

In CT one of the men’s facilities and the women’s facility offered those with a short sentence entering the facility on a methadone maintenance program to continue during their incarceration. Additional attention was paid to those on methadone and some participants became ineligible for the study. This change went into effect July 2012. |

Changes in availability of alternative medication assisted therapies altered willingness to participate in the study. |

| 7) XR-NTX initiation and referral |

A pilot program for XR-NTX starting prior to release with community maintenance was created and made available for residents with alcohol or opioid addictions in the addiction treatment facility of the HCCC starting in April 2013. Prior to this, education of staff and residents on options for medically assisted treatment and community treatment sites was done in all the HCCC facilities. |

In the few instances where routine XR-NTX treatment and placebo controlled trial were both immediately available, patients elected the routine treatment, suggesting that patients’ preferences may influence outcomes. |

| 8) Naloxone in MA | Routine overdose prevention education including intranasal naloxone training and access was expanded in the HCCC facilities and after incarceration program. |

Overdose prevention and naloxone training was welcomed by this population. Concerns about overdose if participants were late for injections should include naloxone prescription and availability. |

| 9) Change in sentences from Risk Reduction Earned Credit program |

Changes in policy changing the release date unexpectedly for participants. Increased monitoring and communication with the DOC was needed to ensure changes in a participant’s release date were known and interviews and injections could be administered before he/she was released. This change went into effect October 2011. There was also a change in earned days from 5 to 10 in MA. |

Communication with the DOC staff is essential to the implementation and continuation of a study that initiates in the correctional facility. |

| 10) Reduction in the number of HIV- infected inmates |

Recruitment to those on parole or probation was expanded in 2013 in an attempt to increase enrollment numbers. |

With decreasing numbers in general inmate populations and increase in various medication- assisted therapies for HIV-infected inmates and alternative correctional programs (halfway houses and drug programs), alternative recruitment strategies are needed to capture those involved in the criminal justice system. |

| Participant Health | ||

| Obstacle | Action Taken | Knowledge Gained |

| 11) Required DSMB |

A DSMB was created with three board certified Infectious Disease doctors at Yale to ensure the safety of the study participants and study performance. |

|

| 12) Education of overdose risk |

Education tools were developed to protect against overdose at the end of the injection period and if a participant missed an injection. This protocol contained a treatment agreement and visual aid reviewed and signed by the participant acknowledging the education received from the risk education. |

These educational sessions and tools, allowed to participants to fully understand the severity of the risk to overdose and death if they should relapse. Treatment agreements were used a treatment plans. |

| 13) Relapse to Opioid Use |

To protect against withdrawal symptoms, should a participant relapse to opioid use before his/her next injection an extensive protocol was developed utilizing self-reported opioid use, urine toxicology screen results, an antagonist challenge and if needed a community buprenorphine detoxification. |

These protocols have been modified for community based administration of XR-NTX. |

Legend: NIDA=National Institute on Drug Abuse; DOC=Department of Correction; CR=Clinical Researcher;

CMHC=Correctional Managed Health Care; XR-NTX=Extended-release naltrexone; HCCC=Hampton County Correctional Center; IRB=Internal Review Board; DSMB=Data Safety Management Board.

(1) Pre-Release

After enrollment, a baseline interview was completed using a computer-assisted survey instrument (CASI) [48, 49, 52, 53]. To ensure participant confidentiality, CASI was selected based on our previous prison studies [50, 54] to allow inmates to respond to sensitive questions about drug and alcohol use and HIV risk behaviors. See Table 1 for the list of instruments administered during the baseline interview. Before final enrollment and the first injection, a clinical researcher (CR) reviewed the inmate’s medical record to ensure s/he does not have Child Pugh Class C cirrhosis or other contraindications to XR-NTX and administered the study medication. In order to ensure that the correctional facility was aware of the inmates’ enrollment and administration of the study medication, a sticker and “order” were placed in the medical chart with a brief summary of the study drug’s possible side effects and the toll-free number to call should an inmate experience any perceived side effects. If a participant was released without receiving an injection prior to release or was referred from the community, the study medication was administered within 30 days post-release, including for those who relapsed to opioids before the first injection.

(2) Day of Release

On the expected day of release the research assistant (RA) met and transported the participant to the study site. Additionally, participants completed a brief interview to document any change in their health and behaviors while they were in the correctional facility including study drug injection experience and potential side effects, as well as undergoing phlebotomy, alcohol breathalyzer assessments, drug urine screening, and update their contact information. To improve retention, participants were paid a “bonus” payment for showing up immediately after release (see Table 1), and a RA accompanied the participants to a site of their preference (home, shelter, short-term housing, etc.) and inquired about any other local spots where they are likely to spend time during the course of the study.

(3) Monthly Research Visits

Over 12 months, participants meet the RA every month for CASI interviews, phlebotomy, drug urine screens, urine pregnancy tests for female participants, alcohol breathalyzer assessments, and cART adherence assessments using the Visual Analog Scale (VAS) [51]. During the intervention phase (6 months) of the study, adverse side effects were assessed and all participants received a brief 15-minute medical management (MM) counseling intervention [52].

(4) Injection Procedures

Following the initial injection, five total injections are administered, each approximately 28 days apart. At each visit, participants met with a CR who assessed side effects from the previous injection, conducted a brief physical assessment focusing on signs of liver damage, pertinent medical history, review of liver function tests (LFTs) and assessment of other contraindications for XR-NTX including potential opioid use, acute hepatitis, current prescription of opioid medications, anticipated need for prescription opioid medications, pregnancy, and breastfeeding. Given that this study is focused on opioid dependent individuals, some of whom were receiving placebo, special attention was paid to participants actively using opioids. We also showed participants a time-dependent graph, provided by Alkermes, Inc., to illustrate the risk of overdose given the falling blood levels of XR-NTX. Participants then signed a study agreement acknowledging their understanding of an increased risk of injury or death due to opioid overdose if they did not receive their next injection at or around 4 weeks after the previous injection.

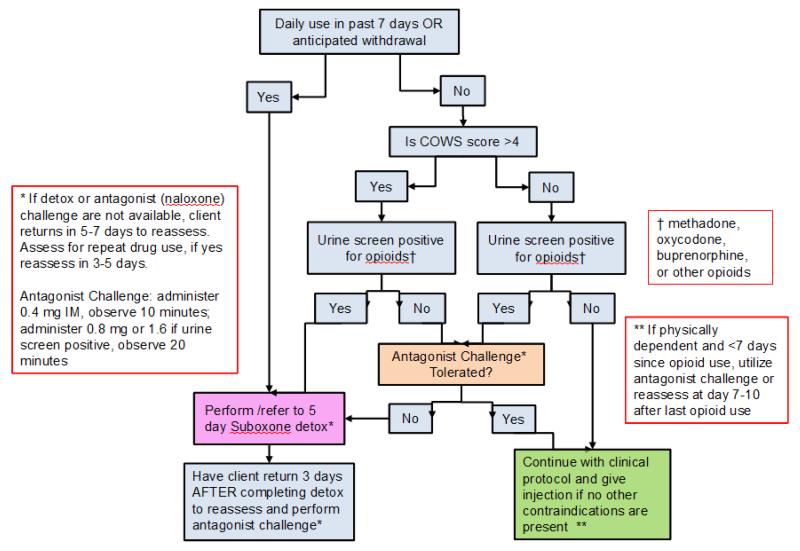

(5) Recent Opioid Use Protocol

All CRs were trained in the study protocol that included extensive protections for participants to avoid precipitating opioid withdrawal (see Figure 4). For participants actively using opioids (within 7 previous days) but is not found to be physically dependent, s/he was given an antagonist (naloxone) challenge (0.4mg intramuscular) and if there were no signs of withdrawal in 10 minutes an additional dose (0.8mg) was administered. Opioid withdrawal signs and symptoms are monitored using the Clinical Opioid Withdrawal Scale (COWS) [53]. If the antagonist challenge caused opioid withdrawal symptoms, participants undergo a 5-day buprenorphine supervised withdrawal protocol. If the antagonist challenge does not precipitate withdrawal, the injection of the study medication is administered if no other contradictions were present. The community detoxification protocol used was based on the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) Tip 40 for a 5-day buprenorphine detox protocol (8mg BID on day 1; 16mg QD on day 2; 12 mg QD on day 3; 8mg on day 4; and then 4mg on day 5) then off of buprenorphine for 3 to 5 days, with daily monitoring on the days off buprenorphine. Upon completion of the supervised withdrawal procedures, participants are then reassessed for injection of the study medication.

Figure 4.

Clinical Management of study participants and ongoing opioid use

(6) Counseling Visits

Irrespective of randomization during the intervention phase (6 months post-release), as part of the 45-minute injection preparation process, all participants receive a standardized monthly brief counseling intervention for opioid dependence, modified from the Medical Management (MM) procedures used in the COMIBINE trial for alcohol dependence [52, 54, 55]. This modified 15–minute MM, conducted by the CR, reviews medication and health information including opioid pharmacotherapy, laboratory results, drug use and prior counseling in addition to briefly counseling patients about the hazards of using opioids. If participants were perceived as failing the existing treatment program, they were referred to more intensive community-based counseling and/or treatment by our on-site substance abuse counselors. In addition, all participants are offered voluntary weekly 12-step counseling sessions held at all of the study sites as well as individualized cognitive behavioral counseling sessions by a licensed behavioral health specialist [56-58]. Use of the voluntary cognitive behavioral counseling interventions is monitored for final study analysis.

Payments

Please refer to Table 1 for subject compensation. Participants were paid for contributing their time to the research activities and not for receiving study medication. The form of participant payment was changed from gift cards to cash in 2013 in response to patient preferences for payment.

Specific Safety Protocols

During the intervention phase of the study, participants are monitored regularly for injection-related side effects, changes in LFTs and renal function, and new contraindications to XR-NTX including pregnancy and opioid relapse and withdrawal [59]. Prior to administration of the study medication, the CR reviews his/her current medications, medical diagnoses, laboratory and drug urine screening results. If a participant develops Grade 4 hepatotoxicity (defined as LFTs >10 times the upper limit of normal with clinical symptoms or signs of hepatotoxicity), Child Pugh Class C cirrhosis, or becomes pregnant, then injections are stopped and the participant is unblinded. As an additional safety precaution, all participants’ primary care providers are sent letters confirming study enrollment, including basic study information that the participant may be receiving XR-NTX or placebo, length of study enrollment, date of initial injection, possible side effects, a statement that opioid pain medication should be avoided, and contact information should s/he have any questions or concerns. Given that two thirds of participants receive XR-NTX, safety wallet cards are provided to all participants to give to any healthcare providers should they require emergency pain medications in the setting of a possible opioid antagonist effect from XR-NTX and possible requirements of pain medication during an emergency. For individuals found to be actively using alcohol and/or drugs, they are referred for additional community-based drug or alcohol treatment.

Analytic Plan

The analytic plan for this study is similar to another similarly designed XR-NTX trial that focuses on pre-release prisoners with HIV and alcohol use disorders [60]. Below is a brief description of the planned analysis.

HIV Treatment Outcomes

The primary study outcome is to compare the proportion of participants achieving VS under the threshold of <400 copies/mL and <50 copies/mL at study month 6 (end of the intervention) using chi-square tests and odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals in the two groups. All participants that completed a baseline interview are considered enrolled and followed for the 12 months, using an ITT analysis, all those with missing values will be imputed as failure (no VS). The trial is on-going and thus results are not currently known.

Secondary HIV treatment outcomes include: mean change in CD4 count and HIV-1 RNA level as a repeated measure at all time points post-release. Changes in log10 HIV-1 RNA will be fitted to a linear regression with interval censoring to account for the large number of censored values owing to HIV-1 RNA at the lower limits of detection at baseline and at follow-up. Missing values will be imputed depending on whether values meet missing at random assumptions. A general linear model including baseline CD4 count and HIV-1 RNA as covariates will assess mean change in the log10 CD4 count from baseline to follow-up month 12.

Similarly, CD4 counts have been strongly associated with survival and risk for development of opportunistic infections. Therefore, it is the goal to maintain or improve CD4 count. It will not, however, be a primary endpoint as CD4 count benefits may persist after loss of adherence. Analysis of change in mean/median CD4 count from baseline to months 6 and 12 will use the Wilcoxon rank test, stratified by variables such as cART experience. Spearman’s rank correlation will test for associations between a wide range of variables with a binomial distribution.

Substance Abuse Outcomes

Several drug relapse variables will be examined. The first drug use variable will be “time to opioid relapse”. Subjects are interviewed monthly using time-line follow-back (TLFB) [65]. Multiple variables will be used to determine opioid use including drug urine screens, positive naloxone challenge results, and a timeline recall method to ascertain the date of first use. Both a median time-to-relapse will be calculated as well as Kaplan Meier time-to-event analysis performed. Significance will be tested using the log rank test and Wilcoxin statistics. The second variable will be a calculation of mean duration of time being drug-free. Each month, a recall of days where illicit drugs were used will be calculated from the TLFB method. For each individual, a mean drug-free interval will be calculated. These drug variables will be calculated for opioids, cocaine and for “any” drug as an exploratory analysis. Last, the proportion of positive drug urine screening results over the 6 months of the intervention will be measured. Missing drug urine screen results will be adjudicated in the following sequential manner: 1) self-report at monthly visits; and 2) last value carried forward if no self-report was available and the next value was the same as the previous one; 3) alternative strategies will explore missing values as positive as well as imputing values based on whether data are missing at random or not. The percent of opioid-free urine screenings over the six-month examination period will compared between the two groups after transforming outcome to means and compared statistically using Mantel-Haenszel Chi Square.

Implementation Issues

When working with the CJS there are unique implementation and logistical concerns that were overcome during the course of this study. Various concerns were addressed in a similar study but were again encountered here [60]. Listed below and in Table 3 are some of the additional barriers that were encountered and overcome during this study.

Review Board Protocol Approval: Multiple submissions to the Yale Human Investigational Board, Baystate Medical Center IRB, the Director of Research at HCCC, CTDOC Research Advisory Committee, and Waterbury Hospital IRB were required to ensure each facility was operating under the same systematic study protocol, and to ensure any and all issues were addressed by the each institution. Although initial approval from all of the review boards was approximately 6 months, a total of 12 months was needed to coordinate the changes and obtain final OHRP approval and a CoC (see Obstacle 4 in Table 3).

Data Safety Monitoring Board (DSMB): Per NIDA request, a DSMB, expanded and more stringent than the original Data Safety Monitoring Plan, was created which included three board certified Infectious Disease doctors at Yale Medical School to conduct interim monitoring of the study’s risk. Also included in the DSMB was a protocol detailed with the precautions used in the study to monitor for side effects, liver damage, risk of overdose, and other aspects of the study. Responsibilities of the DSMB include reviewing the study performance, evaluation of study quality, and recommending the continuation of the ongoing study (see Obstacle 11 in Table 3).

Correctional Facility Information Sessions: Board-certified Addiction Medicine physicians conducted information sessions throughout the study regarding XR-NTX and other pharmacological treatments available in the community for those with opioid dependence. These interactive sessions allowed the correctional staff to learn about the differences in the treatments, how they are administered, safety information, and updates of treatment use. When this study was initiating recruitment, XR-NTX was newly approved by the FDA for opioid dependence; questions from the staff were expected and addressed (see Obstacle 5 in Table 3).

Coordination Between Multiple Sites: In order to ensure timely and secure data transfer, a quarterly schedule was created for data transfers from Baystate Medical Center. Encrypted data transfer systems provided by Yale University Information Technology Services were used to ensure participants information was protected in a HIPAA approved manor (see Obstacles 2 and 3 in Table 3).

Reduction of HIV-infected Inmate Population: During the study submission process, the average daily census of HIV-infected inmates in the CTDOC, where a majority of the participants were recruited was 320 [62]. This number was substantially reduced by 16.6% over the time of the study (personal communication, C. Gallagher CTDOC, September 4, 2014) as a consequence of several other projects that aimed to reduce recidivism by providing other MAT for HIV-infected inmates transitioning to the community (see Obstacle 10 in Table 3).

Changes in Department of Correction Policy: At the end of 2011 and beginning of 2012 two major changes occurred in the CTDOC policy. MMT was made available in one of the men’s jail facilities the women’s correctional facility in CT for those with a short sentence and entered the facility while on MMT. A pilot program in the Massachusetts drug and alcohol rehabilitation facilities supervised by the HCCC, began to offer XR-NTX treatment. Additionally, those incarcerated with specific non-violent charges were given the ability to earn five days off of their sentence for each month of “good behavior” with the Risk Reduction Earned Credit program. In HCCC there was an increase in number of sentence reduction days earned from 5 to 10 days (see Obstacles 6-9 in Table 3).

Summary

It is possible that the negative attitudes by correctional providers, stigma, diversion concerns, poor adherence, and additional restrictive licenses of using an opioid agonist for treating opioid dependence may be possible reasons why they are not widely deployed in the CJS [29, 33, 63]. XR-NTX provides an alternative treatment as an opioid antagonist, which does not require additional certifications or licenses to administer and store these medications unlike agonist treatments [63, 65]. The monthly dosing schedule of injections could potentially reduce adherence concerns with daily oral medications and eliminate the concerns of diversion. Additionally, the protective properties of XR-NTX and the long-acting half-life may reduce the risk of overdose upon release from the correctional system when administered prior to release. Although other forms of MAT are widely available in the U.S., including BMT, MMT, and XR-NTX, no studies have compared these MATs for released prisoners and MMT must be initiated ~6 months pre-release in order to achieve effective doses [66, 67]. For most prisoners who are not tolerant to opioids upon release, BMT and XR-NTX are preferred options. Both medications, however, differ with regard to pharmacology, route of administration (sublingual versus injection), duration of effect (daily versus monthly), benefits on alcohol disorders (XR-NTX) and opioid craving (BMT), side effects, cost, impact on retention and patient preferences. Moreover, prison administrators favor XR-NTX over BMT due to its lack of dependence (“being addicted”), but patients may reject it for other reasons. Thus comparative effectiveness studies are urgently needed to inform patient-centered treatment options that involved informed patient decision-making.

As part of the STTR model by NIDA, this is the first double-bind, placebo-controlled clinical trial of XR-NTX for opioid dependent, HIV-infected persons involved in the CJS. The novel use of XR-NTX within the CJS as a conduit for HIV care will strengthen the current evidence of the effectiveness of XR-NTX. Concerns regarding hepatic safety of XR-NTX have been expressed prior to initiating this intervention given the impact of cART on liver function and the high rate of Hepatitis C virus co-infection. New evidence, however, now provides assurances of XR-NTX safety in HIV-infected patients on cART [68, 69]. Given the consequences of relapse to opioid use after release from the correctional system, XR-NTX can prevent relapse, and prevent the spiral of poor care leading to increased HIV risk behaviors, poor adherence to cART, and possible risk of infecting those in the community.

Findings from this study may show the benefits of initiating opioid treatment prior to release as a way to improve HIV treatment by preventing and reducing drug use. Also of note, this study provided an opportunity to develop a safety and clinical protocol for the use of XR-NTX for opioid dependence within the community including the monitoring of opioid relapse and opioid withdrawal and use of a community detoxification protocol with buprenorphine prior to reinitiating injection with XR-NTX that may be used by others in similar research settings or for routine clinical use. Additionally, the preliminary findings of acceptability for this form of opioid dependence treatment may not be generalizable to all those involved in the CJS.

This study was designed to provide good internal validity by controlling for known confounders, by having a target sample size powered to detect the difference in primary outcome using a similar sample, using validated measurements, and by using statistical methods that have been proven to reduce Type I and Type II errors. The nature of this population may lead to a threat to the external validity of this study as seen in the modest acceptability of XR-NTX thus far in this on-going study. Given the large number of those who refused at different stages of the study there is a potential threat to the external validity of the treatment and desire to enroll in the study. Unlike the initial large clinical trial where other forms of MAT are not available [70], a large percentage of the population (79%) reported a previous experience with other forms of MAT and the main reason for refusal was “the desire for treatment using another form of MAT”. This “choice” allows for the opportunity to participate in an informed decision regarding their form of MAT prior to release, which may reduce opioid relapse and the negative consequences that occur from active drug use thereby increasing the external validity of the study. With the recent changes to the DSM-V and the availability of newer, office-based treatments for opioid use disorders, we now require a reassessment of transitional care for opioid dependent patients in the CJS.

Acknowledgements

The funding for this research is provided by NIDA (R01DA030762, SAS) for research and for career development (K02 DA032322 for SAS and K24 DA017059 for FLA). Both study medication and placebo were provided free from an investigator-initiated grant from Alkermes, Inc. The authors would also like to thank the study participants, research staff, CTDOC and HCCC for making this study possible.

Footnotes

Clinical Trial number: NCT01246401

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Abbreviations; Substance use disorders (SUDs); criminal justice system (CJS);combination antiretroviral treatment (cART); CD4+ T lymphocyte (CD4); viral suppression (VS); methadone (MMT); buprenorphine (BMT); Naltrexone (NTX); Extended-release naltrexone (XR-NTX); medication assisted therapy (MAT); National Institute of Drug Abuse (NIDA); National Institute of Health (NIH); seek, test, treat and retain (STTR); Randomized Control Trial (RCT); Internal Review Board (IRB); Connecticut Department of Correction (CTDOC); Hampton County Correctional Center (HCCC); Office of Human Research Protections (OHRP); Certificate of Confidentiality (CoC); intention-to-treat (ITT); Infectious Disease Nurse (IDN); release of information (ROI); Research Assistant (RA); Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI); Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT); Systemic Assessment For Treatment Emergent Effects Intervention (SAFTEE); computer-assisted survey (CASI); Investigational Drug Service (IDS); Clinician Researcher (CR); liver function test (LFT); clinical opioid withdrawal scale (COWS) Medical Management (MM).

Bibliography

- [1].Maruschak L, Beavers R. HIV in Prisons, 2007-08. In: Bureau of Justice Statistics, editor. Bureau of Justice Statistics Bulletin. U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs; Washington, D.C.: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- [2].Spaulding AC, Seals RM, Page MJ, Brzozowski AK, Rhodes W, Hammett TM. HIV/AIDS among inmates of and releasees from US correctional facilities, 2006: declining share of epidemic but persistent public health opportunity. PloS one. 2009;4:e7558. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Cepeda JA, Springer SA. Encyclopedia of Criminology and Criminal Justice. Springer; 2014. Drug Abuse and Alcohol Dependence Among Inmates; pp. 1147–59. [Google Scholar]

- [4].Mumola CJ, Karberg JC. Drug Use and Dependence, State and Federal Prisons, 2004. US Department of Justice; 2006. Document NCJ 213530. [Google Scholar]

- [5].Altice FL, Tehrani AS, Qiu J, Herme M, Springer SA. Directly Administered Antriretroviral Therapy (DAART) is Superior to Self-Administered Therapy (SAT) Among Released HIV+ Prisoners: Results from a Randomized Controlled Trial 18th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; Boston, MA. 2011. Abstract K-131. [Google Scholar]

- [6].Saber-Tehrani AS, Springer SA, Qiu J, Herme M, Wickersham J, Altice FL. Rationale, study design and sample characteristics of a randomized controlled trial of directly administered antiretroviral therapy for HIV-infected prisoners transitioning to the community - a potential conduit to improved HIV treatment outcomes. Contemp Clin Trials. 2012;33:436–44. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2011.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Springer SA, Qiu J, Saber-Tehrani AS, Altice FL. Retention on buprenorphine is associated with high levels of maximal viral suppression among HIV-infected opioid dependent released prisoners. PloS one. 2012;7:e38335. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Springer SA, Chen S, Altice FL. Improved HIV and substance abuse treatment outcomes for released HIV-infected prisoners: the impact of buprenorphine treatment. Journal of urban health : bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine. 2010;87:592–602. doi: 10.1007/s11524-010-9438-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Hammett TM, Harmon MP, Rhodes W. The burden of infectious disease among inmates of and releasees from US correctional facilities, 1997. American journal of public health. 2002;92:1789–94. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.11.1789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Springer SA, Pesanti E, Hodges J, Macura T, Doros G, Altice FL. Effectiveness of antiretroviral therapy among HIV-infected prisoners: reincarceration and the lack of sustained benefit after release to the community. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2004;38:1754–60. doi: 10.1086/421392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Springer SA, Friedland GH, Doros G, Pesanti E, Altice FL. Antiretroviral treatment regimen outcomes among HIV-infected prisoners. HIV clinical trials. 2007;8:205–12. doi: 10.1310/hct0804-205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Meyer JP, Cepeda J, Wu J, Trestman RL, Altice FL, Springer SA. Optimization of Human Immunodeficiency Virus Treatment During Incarceration: Viral Suppression at the Prison Gate. JAMA internal medicine. 2014;174:721–9. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2014.601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Stephenson BL, Wohl DA, Golin CE, Tien HC, Stewart P, Kaplan AH. Effect of release from prison and re-incarceration on the viral loads of HIV-infected individuals. Public health reports. 2005;120:84–8. doi: 10.1177/003335490512000114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Althoff AL, Zelenev A, Meyer JP, Fu J, Brown SE, Vagenas P, et al. Correlates of retention in HIV care after release from jail: results from a multi-site study. AIDS and behavior. 2013;17(Suppl 2):S156–70. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0372-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Krishnan A, Wickersham JA, Chitsaz E, Springer SA, Jordan AO, Zaller N, et al. Post-release substance abuse outcomes among HIV-infected jail detainees: results from a multisite study. AIDS Behav. 2013;17:S171–80. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0362-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Krishnan A, Ferro EG, Weikum D, Vagenas P, Lama JR, Gonzales P, et al. Communication Technology Use and mHealth Acceptance among HIV-infected Men who have Sex with Men in Peru: Implications for HIV Prevention and Treatment. AIDS care. 2014 doi: 10.1080/09540121.2014.963014. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Baillargeon J, Giordano TP, Rich JD, Wu ZH, Wells K, Pollock BH, et al. Accessing antiretroviral therapy following release from prison. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2009;301:848–57. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Meyer JP, Althoff AL, Altice FL. Optimizing Care for HIV-Infected People Who Use Drugs: Evidence-Based Approaches to Overcoming Healthcare Disparities. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2013;57:1309–17. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Levasseur L, Marzo JN, Ross N, Blatier C. Frequency of re-incarcerations in the same detention center: role of substitution therapy. A preliminary retrospective analysis. Annales de medecine interne. 2002;153:1S14–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Fu JJ, Herme M, Wickersham JA, Zelenev A, Althoff A, Zaller ND, et al. Understanding the revolving door: individual and structural-level predictors of recidivism among individuals with HIV leaving jail. AIDS and behavior. 2013;17(Suppl 2):S145–55. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0590-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Binswanger IA, Blatchford PJ, Lindsay RG, Stern MF. Risk factors for all-cause, overdose and early deaths after release from prison in Washington state. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2011;117:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Binswanger IA, Stern MF, Deyo RA, Heagerty PJ, Cheadle A, Elmore JG, et al. Release from prison--a high risk of death for former inmates. The New England journal of medicine. 2007;356:157–65. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa064115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Harding-Pink D. Mortality following release from prison. Medicine, science, and the law. 1990;30:12–6. doi: 10.1177/002580249003000104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Harding-Pink D, Fryc O. Risk of death after release from prison: a duty to warn. Bmj. 1988;297:596. doi: 10.1136/bmj.297.6648.596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Merrall EL, Kariminia A, Binswanger IA, Hobbs MS, Farrell M, Marsden J, et al. Meta-analysis of drug-related deaths soon after release from prison. Addiction. 2010;105:1545–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.02990.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Binswanger IA, Blatchford PJ, Mueller SR, Stern MF. Mortality after prison release: opioid overdose and other causes of death, risk factors, and time trends from 1999 to 2009. Annals of internal medicine. 2013;159:592–600. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-159-9-201311050-00005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Krinsky CS, Lathrop SL, Brown P, Nolte KB. Drugs, detention, and death: a study of the mortality of recently released prisoners. The American journal of forensic medicine and pathology. 2009;30:6–9. doi: 10.1097/PAF.0b013e3181873784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Thompson MA, Mugavero MJ, Amico KR, Cargill VA, Chang LW, Gross R, et al. Guidelines for improving entry into and retention in care and antiretroviral adherence for persons with HIV: evidence-based recommendations from an International Association of Physicians in AIDS Care panel. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156:817–33. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-156-11-201206050-00419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Smith-Rohrberg D, Bruce RD, Altice FL. Review of corrections-based therapy for opiate-dependent patients: Implications for buprenorphine treatment among correctional populations. Journal of Drug Issues. 2004;34:451–80. [Google Scholar]

- [30].Springer S. Commentary on Larney (2010):A call to action–opioid substitution therapy as a conduit to routine care and primary prevention of HIV transmission among opioid-dependent prisoners. Addiction. 2010;105:224–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02893.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Kinlock TW, Gordon MS, Schwartz RP, Fitzgerald TT, O’Grady KE. A randomized clinical trial of methadone maintenance for prisoners: results at 12 months postrelease. Journal of substance abuse treatment. 2009;37:277–85. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2009.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Coviello DM, Cornish JW, Lynch KG, Boney TY, Clark CA, Lee JD, et al. A Multisite Pilot Study of Extended-Release Injectable Naltrexone Treatment for Previously Opioid-Dependent Parolees and Probationers. Substance Abuse. 2011;33:48–59. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2011.609438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Friedmann PD, Taxman FS, Henderson CE. Evidence-based treatment practices for drug-involved adults in the criminal justice system. Journal of substance abuse treatment. 2007;32:267–77. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Magura S, Lee JD, Hershberger J, Joseph H, Marsch L, Shropshire C, et al. Buprenorphine and methadone maintenance in jail and post-release: a randomized clinical trial. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2009;99:222–30. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Center on Budget and Policy Priorites . The Number of Uninsured Americans is at an All-Time High. Washington, D.C.: [March 1, 2008]. Accessed from http://www.cbpp.org/8-29-06health.htm on. [Google Scholar]

- [36].Chandler RK, Fletcher BW, Volkow ND. Treating drug abuse and addiction in the criminal justice system: improving public health and safety. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2009;301:183–90. doi: 10.1001/jama.2008.976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Fletcher B, Lehman W, Wexler H, Melnick G, Taxman F, Young D. Measuring collaboration and integration activities in criminal justice and substance abuse treatment agencies. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2009;103(Suppl 1):S54–S64. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Nunn A, Zaller N, Dickman S, Trimbur C, Nijhawan A, Rich JD. Methadone and buprenorphine prescribing and referral practices in US prison systems: results from a nationwide survey. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2009;105:83–8. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Gordon MS, Kinlock TW, Schwartz RP, Fitzgerald TT, O’Grady KE, Vocci FJ. A randomized controlled trial of prison-initiated buprenorphine: Prison outcomes and community treatment entry. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2014;142:33–40. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].National Institute of Drug Abuse Seek, Test, Treat and Retain. 2012 Feb; Retrieved January 20, 2014: http://www.drugabuse.gov/researchers/research-resources/data-harmonization-projects/seek-test-treat-retain.

- [41].Kinlock TW, Gordon MS, Schwartz RP, O’Grady KE. A Study of Methadone Maintenance For Male Prisoners: 3-Month Postrelease Outcomes. Criminal justice and behavior. 2008;35:34–47. doi: 10.1177/0093854807309111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Springer SA, Spaulding AC, Meyer JP, Altice FL. Public health implications for adequate transitional care for HIV-infected prisoners: five essential components. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2011;53:469–79. doi: 10.1093/cid/cir446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Wickersham JA, Azar MM, Cannon CM, Altice FL, Springer SA. Development of a brief measure of opioid dependece: the rapid opioid dependence screen (RODS) Journal of Correctional Health Care. 2014 doi: 10.1177/1078345814557513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Levine J, Schooler NR. SAFTEE: a technique for the systematic assessment of side effects in clinical trials. Psychopharmacology bulletin. 1986;22:343–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].International Harm Reduction Development Program (IHRD) of the Open Society Institute (OSI) Barriers to Access: Medication-Assisted Treatment and Injection-Driven HIV Epidemics. In: Open Society Institute (OSI), editor. Open Society Institute; New York, NY: 2008. pp. 1–5.http://wwwsorosorg/initiatives/health/focus/ihrd/articles_publications/publications/barriers_20080215/barriersfootnotes040808pdf [Google Scholar]

- [46].Scott NW, McPherson GC, Ramsay CR, Campbell MK. The method of minimization for allocation to clinical trials. a review. Controlled clinical trials. 2002;23:662–74. doi: 10.1016/s0197-2456(02)00242-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Kang M, Ragan BG, Park JH. Issues in outcomes research: an overview of randomization techniques for clinical trials. Journal of athletic training. 2008;43:215–21. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-43.2.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Tideman RL, Chen MY, Pitts MK, Ginige S, Slaney M, Fairley CK. A randomised controlled trial comparing computer-assisted with face-to-face sexual history taking in a clinical setting. Sexually transmitted infections. 2007;83:52–6. doi: 10.1136/sti.2006.020776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Caldwell DH, Jan G. Computerized assessment facilitates disclosure of sensitive HIV risk behaviors among African Americans entering substance abuse treatment. The American journal of drug and alcohol abuse. 2012;38:365–9. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2012.673663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Azbel L, Wickersham JA, Grishaev Y, Dvoryak S, Altice FL. Burden of infectious diseases, substance use disorders, and mental illness among Ukrainian prisoners transitioning to the community. PloS one. 2013;8:e59643. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0059643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Amico KR, Fisher W, Cornman D, Shuper P, Redding C, Konkle-Parker D, et al. Visual analog scale of ART adherence: association with 3-day self-report and adherence barriers. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes and human retrovirology : official publication of the International Retrovirology Association. 2006;42:455–9. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000225020.73760.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Pettinati H, Weiss R, Miller WR, Donovan D, Ernst D, BJ R. Medical Management Treatment Providing Pharmacotherapy as Part of the Treatment for Alcohol Dependence. In: NIAAA, editor. DHHS; Bethesda, MD: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- [53].Tompkins DA, Bigelow GE, Harrison JA, Johnson RE, Fudala PJ, Strain EC. Concurrent validation of the Clinical Opiate Withdrawal Scale (COWS) and single-item indices against the Clinical Institute Narcotic Assessment (CINA) opioid withdrawal instrument. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2009;105:154–9. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism . Helping Patients Who Drink Too Much: A Clinician’s Guide. In: NIAAA, editor. NIAAA; 2005. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- [55].Anton RF, O’Malley SS, Ciraulo DA, Cisler RA, Couper D, Donovan DM, et al. Combined pharmacotherapies and behavioral interventions for alcohol dependence: the COMBINE study: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2006;295:2003–17. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.17.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Copenhaver MM, Bruce RD, Altice FL. Behavioral counseling content for optimizing the use of buprenorphine for treatment of opioid dependence in community-based settings: a review of the empirical evidence. The American journal of drug and alcohol abuse. 2007;33:643–54. doi: 10.1080/00952990701522674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Copenhaver M, Avants SK, Warburton LA, Margolin A. Intervening effectively with drug abusers infected with HIV: taking into account the potential for cognitive impairment. Journal of psychoactive drugs. 2003;35:209–18. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2003.10400002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Miller WR, Arciniega LT. Combined behavioral intervention manual: A clinical research guide for therapists treating people with alcohol abuse and dependence: US Department of Health and Human Services. National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- [59].Vivitol (R) Alkermes, Inc; Waltham, MA: 2013. package instert. [Google Scholar]

- [60].Springer SA, Altice FL, Herme M, Di Paola A. Design and methods of a double blind randomized placebo-controlled trial of extended-release naltrexone for alcohol dependent and hazardous drinking prisoners with HIV who are transitioning to the community. Contemp Clin Trials. 2013;37:209–18. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2013.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Copersino ML, Meade CS, Bigelow GE, Brooner RK. Measurement of self-reported HIV risk behaviors in injection drug users: comparison of standard versus timeline follow-back administration procedures. Journal of substance abuse treatment. 2010;38:60–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2009.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Maruschak L. HIV in prisons, 2001-2010. Bureau of Jstive Statistics. 2012 [Google Scholar]

- [63].Rich JD, Boutwell AE, Shield DC, Key RG, McKenzie M, Clarke JG, et al. Attitudes and practices regarding the use of methadone in US state and federal prisons. Journal of urban health : bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine. 2005;82:411–9. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jti072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Krupitsky EM, Blokhina EA. Long-acting depot formulations of naltrexone for heroin dependence: a review. Current opinion in psychiatry. 2010;23:210–4. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e3283386578. 10.1097/YCO.0b013e3283386578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Gastfriend DR. Intramuscular extended-release naltrexone: current evidence. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2011;1216:144–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05900.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Wickersham JA, Marcus R, Kamarulzaman A, Zahari MM, Altice FL. Implementing methadone maintenance treatment in prisons in Malaysia. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2013;91:124–9. doi: 10.2471/BLT.12.109132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Wickersham JA, Zahari MM, Azar MM, Kamarulzaman A, Altice FL. Methadone dose at the time of release from prison significantly influences retention in treatment: Implications from a pilot study of HIV-infected prisoners transitioning to the community in Malaysia. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2013;132:378–82. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Mitchell MC, Memisoglu A, Silverman BL. Hepatic safety of injectable extended-release naltrexone in patients with chronic hepatitis C and HIV infection. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2012;73:991–7. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2012.73.991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Vagenas P, Di Paola A, Herme M, Lincoln T, Skiest DJ, Altice FL, et al. An evaluation of hepatic enzyme elevations among HIV-infected released prisoners enrolled in two randomized placebo-controlled trials of extended release naltrexone. Journal of substance abuse treatment. 2014;47:35–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2014.02.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Krupitsky E, Nunes EV, Ling W, Illeperuma A, Gastfriend DR, Silverman BL. Injectable extended-release naltrexone for opioid dependence: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, multicentre randomised trial. Lancet. 2011;377:1506–13. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60358-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Delate T, Coons SJ. The discriminative ability of the 12-item short form health survey (SF-12) in a sample of persons infected with HIV. Clinical therapeutics. 2000;22:1112–20. doi: 10.1016/S0149-2918(00)80088-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Amorim P, Lecrubier Y, Weiller E, Hergueta T, Sheehan D. DSM-IH-R Psychotic Disorders: procedural validity of the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI). Concordance and causes for discordance with the CIDI. European psychiatry : the journal of the Association of European Psychiatrists. 1998;13:26–34. doi: 10.1016/S0924-9338(97)86748-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Sheehan D, Lecrubier Y, Harnett-Sheehan K, Janavs J, Weiller E, Bonors L, et al. Reliability and Validity of the MINI International Neuropsychiatric Interview (M.I.N.I.): According to the SCID-P. Eur Psychiat. 1997;12:232–41. [Google Scholar]

- [74].Lecrubier Y, Sheehan DV, Weiller E, Amorim P, Bonora I, Sheehan KH, et al. The Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview (MINI). A short diagnostic structured interview: Reliability and validity according to the CIDI. Eur Psychiat. 1997;12:224–31. [Google Scholar]

- [75].Wang J, Kelly BC, Booth BM, Falck RS, Leukefeld C, Carlson RG. Examining factorial structure and measurement invariance of the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI)-18 among drug users. Addictive behaviors. 2010;35:23–9. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Derogatis LR. BSI 18, Brief Symptom Inventory 18: Administration, scoring and procedures manual: NCS Pearson. 2001. Incorporated. [Google Scholar]

- [77].Derogatis LR. Brief symptom inventory 18 (BSI-18) manual. NCS Assessments; Minnetonka, MN: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- [78].McLellan AT, Kushner H, Metzger D, Peters R, Smith I, Grissom G, et al. The Fifth Edition of the Addiction Severity Index. Journal of substance abuse treatment. 1992;9:199–213. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(92)90062-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Rosen C, Henson B, Finney J, Moos R. Consistency of self-administered and interview-based Addiction Severity Index composite scores. Addiction. 2000;95:419–25. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.95341912.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Cacciola JS, Alterman AI, McLellan AT, Lin Y-T, Lynch KG. Initial evidence for the reliability and validity of a “Lite” version of the Addiction Severity Index. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2007;87:297–302. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2006.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Barbor ea. The AUDIT, Guidelines for use in primary care. World health organization; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- [82].Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, de la Fuente JR, Grant M. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO Collaborative Project on Early Detection of Persons with Harmful Alcohol Consumption--II. Addiction. 1993;88:791–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Sobell LC, Toneatto T, Sobell MB, Leo GI, Johnson L. Alcohol abusers’ perceptions of the accuracy of their self-reports of drinking: implications for treatment. Addictive behaviors. 1992;17:507–11. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(92)90011-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Sobell LC, Sobell MB. Handbook of Psychiatric Measures. American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC: 2000. Alcohol Timeline Followback (TLFB) pp. 477–9. [Google Scholar]

- [85].Fisher JD, Fisher WA, Cornman DH, Amico RK, Bryan A, Friedland GH. Clinician-delivered intervention during routine clinical care reduces unprotected sexual behavior among HIV-infected patients. Journal of acquired immune deficiency syndromes. 2006;41:44–52. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000192000.15777.5c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Johnson BA, Ait-Daoud N, Roache JD. The COMBINE SAFTEE: a structured instrument for collecting adverse events adapted for clinical studies in the alcoholism field. J Stud Alcohol Suppl. 2005:157–67. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2005.s15.157. discussion 40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]