BREED specifications for pure-bred/pedigree dogs are laid down by the organisations that register and judge dogs, such as the Kennel Club of the UK (KCUK) and the Kennel Union of South Africa (KUSA), as well as the umbrella body the Fédération Cynologique Internationale (FCI). Reproductive isolation between breeds results because animals can only be registered as a specific breed if they have five previous generations of ancestors registered as the same breed, creating a ‘breed barrier’ which promotes genetic differences among breeds. This genetic isolation in a population of UK dogs (Mellanby and others 2013) has been demonstrated previously. The lowest heterozygosities of around 0.5 were found for breeds such as the German shepherd dog, rottweiler and boxer dog, indicative of a reasonably high level of inbreeding. Labrador retrievers and border collies had heterozygosities of around 0.7, indicating greater genetic diversity. The Jack Russell terrier is not a registered breed with the KCUK. This group had a heterozygosity of close to 0.8 and maintained a high degree of genetic variability.

The authors were interested to assess whether dog breeds in another country had similar levels of genetic isolation. Three popular breeds were chosen, which showed differing heterozygosities in the UK: the German shepherd dog, the labrador retriever and the Jack Russell terrier (Mellanby and others 2013). Breed specifications for the labrador retriever were identical for the KCUK and the KUSA, whereas the specification for the German shepherd dog in South Africa is taken from the FCI criteria rather than the KCUK criteria which are very similar. The Jack Russell is not a KCUK-registered breed (Mellanby and others 2013) but is registered with the KUSA, conforming to the breed standard of the Australian National Kennel Council. Therefore, it might be expected to show less genetic diversity in South Africa due to the need to conform to breed specifications. Breed standards are available at https://www.thekennelclub.org.uk/services/public/breed/Default.aspx and http://www.kusa.co.za/index.php/documents/breed-standards.

Genotypes using 15 microsatellite markers were established for 14 labrador retrievers, 26 German shepherd dogs and 35 Jack Russell terriers from South Africa, using the previously published protocol (Ogden and others 2011, Mellanby and others 2013). Calculations of heterozygosity and relative genetic distance were performed as described (Mellanby and others 2013). Table 1 shows the calculated heterozygosities and genetic distance for the animals from South Africa, compared with the results for UK dogs. Heterozygosities did not differ between countries, but the pairwise FST values were lower for South African dogs, indicating that the UK dogs have experienced greater genetic isolation (an FST of 1 indicates complete isolation). Other studies also using microsatellites have achieved comparable heterozygosities. For example, Irion and others (2003) found heterozygosities of 0.64 and 0.78 for labrador retrievers and Jack Russell terriers, respectively, based on 100 microsatellite markers, and Leroy and others (2009) observed heterozygosities of 0.56 and 0.60 for German shepherd dogs and labrador retrievers, respectively. Wade (2011) reported heterozygosity of 0.31 in labrador retrievers using single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) markers (unknown number). The lower heterozygosity with SNP markers is consistent with the biallelic nature of SNPs which reduces the maximum possible heterozygosity for each SNP to 0.5, compared with the multiallelic microsatellite markers used here with maximum heterozygosity ranging from 0.84 (six alleles) to 0.95 (20 alleles).

TABLE 1:

Estimated heterozygosities (HE)and genetic distances (FST) for South African dogs

| Breed | HE* | FST* with |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Jack Russell terrier | Labrador retriever | ||

| Jack Russell terrier | 0.76 (0.76) | ||

| Labrador retriever | 0.68 (0.68) | 0.042 (0.064) | |

| German shepherd dog | 0.57 (0.54) | 0.087 (0.153) | 0.106 (0.201) |

HE is a measure of the genetic diversity in the population; a high HE value indicates that many individuals are heterozygous at many loci, consistent with a low level of inbreeding. FST is an estimate of the genetic differentiation between two populations. A high value indicates that the two populations are genetically isolated. Values were calculated using the programme GENALEX (Peakall and Smouse 2006).

*Values in brackets for UK dogs (from Mellanby and others 2013).

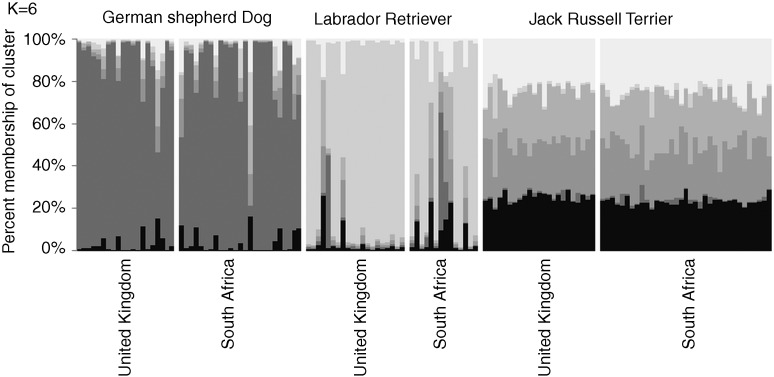

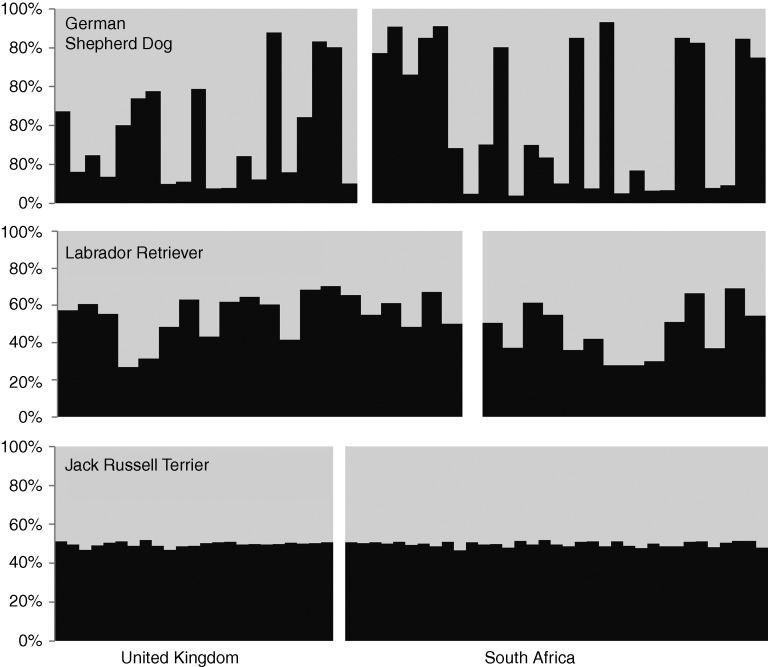

The software STRUCTURE (Pritchard and others 2000) was then used to identify the mixture of ancestral groups in each dog. This program uses genotype data from many loci to investigate population structure. Results allow the inference of distinct populations within an admixed group. In each STRUCTURE run the number of population subgroups (K) is specified and runs are repeated at increasing values of K until no further substructure is detected. The lowest value of K which detects all subpopulations is a measure of the number of population subgroups in the data set. Analyses were run as described (Mellanby and others 2013) using the results for 15 microsatellite markers, and both South African dogs and the UK dogs previously reported by Mellanby and others (2013) were included. Fig 1 shows the outcome of this analysis when K (number of contributing subpopulations) was set at 6. The result was the same with higher values of K. This analysis showed that within a breed the dogs were genetically very similar regardless of the country. Jack Russell terriers showed equal contributions from different subpopulations, whereas labrador retrievers and German shepherd dogs each showed 90 per cent contribution from a single subpopulation. Jack Russell terriers had very little contribution from either of the subpopulations predominant in the labrador retrievers or German shepherd dogs, as might be expected given the very different phenotype and ancestry of these dogs. The admixture of subpopulations within a breed was the same regardless of country, showing that the breeds have not diverged greatly. To further test this, each breed was subjected individually to STRUCTURE analysis. There was no evidence of stratification based on country of origin at K=2 or higher K values (Fig 2). As previously reported (Mellanby and others 2013), misclassification of dog breed was common with four of the South African labrador retrievers and one of the German shepherd dogs showing mixed breed ancestry, whereas several others had a 50 per cent contribution from one subpopulation suggesting a one parent of the associated breed and one of another breed or mixed breed background.

FIG 1:

STRUCTURE analysis of three dog breeds from the UK and South Africa. Genotypes for 15 microsatellites for dogs of all three breeds from South Africa and the UK were entered into the program STRUCTURE and the analysis run with a burn-in period of 100,000 replications and a run of 500,000 replications (Mellanby and others 2013). Runs were repeated between two and five times for each value of K to assess the stability of the population structure detected. The results are shown for a typical run with K=6. Each vertical column represents a different dog, whereas the shades of grey represent six different subpopulations in the admixture. The y axis shows the proportional of the genotype attributed to each subpopulation for each dog

FIG 2:

STRUCTURE analysis within dog breeds from the UK and South Africa. The input data were the same as for Fig 1, but the input contained only the results for a single breed. Burn-in, run and replications were the same as for Fig 1. Results are shown for K=2. The relative proportion of each population in each dog is shown in dark and light grey.; the outcome was similar for higher values of K

This analysis shows that the assignment of dogs to pedigree classes on the basis of genotype is robust across the two countries and there is little evidence for genetic drift within breeds, reflecting the similarity of the breed standards between the two countries. This may be maintained by the import of dogs from other countries and the exchange of semen for artificial insemination. Artificial insemination from cryopreserved domestic dog semen has been available since the 1960s (Thomassen and Farstad 2009) and use of artificial insemination has increased among pedigree dog breeders as technologies have developed to preserve and transport semen. Although this could benefit the breed and enhance genetic diversity by varying the sires used by a breeder, it is also seen as a cost-effective method to maximise the number of progeny of popular sires (Thomassen and Farstad 2009), hence restricting the gene pool. Worldwide use of semen from a small number of sires may have the effect of maintaining the homogeneity of the breed across geographically separated regions. The heterozygosity of the Jack Russell has been maintained in South Africa, indicating that registration as a breed and the need to conform to breed standard has not reduced genetic diversity at this point.

Thus, the geographical isolation of the two countries has not apparently led to genetic divergence within the breeds examined, suggesting that there is minimal reproductive isolation and considerable genetic exchange. Consequently, an important implication of this study is that genetic diseases detected in a breed (Asher and others 2009, Summers and others 2010) are likely to be found in both countries and could be transmitted from founders in either country, exacerbated by the use of artificial insemination, limiting the number of sires.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the owners of the dogs included in this study for agreeing to participate. This study was partly funded by a Clinical Pump Priming Grant from the Roslin Institute to DNC, RJM, KMS, JPS, Mark Bronsvoort and Andreas Lengeling, a grant from Petsavers to RJM and DNC and a Genesis-Faraday SPARK award to RO, RJM, DNC and Ross McEwing. The Roslin Institute is supported by BBSRC Institute Strategic Grant funding.

References

- ASHER L., DIESEL G., SUMMERS J. F., MCGREEVY P. D. & COLLINS L. M. (2009) Inherited defects in pedigree dogs. Part 1: disorders related to breed standards. Veterinary Journal 182, 402–411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IRION D.N., SCHAFFER A.L., FAMULA T.R., EGGLESTON M.L., HUGHES S.S. & PEDERSEN N.C. (2003) Analysis of genetic variation in 28 pedigree dog breed populations with 100 microsatellite markers. The Journal of Heredity 94, 81–87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LEROY G., VERRIER E., MERIAUX J.C. & ROGNON X. (2009) Genetic diversity of dog breeds: within-breed diversity comparing genealogical and molecular data. Animal Genetics 40, 323–332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MELLANBY R. J., OGDEN R., CLEMENTS D. N., FRENCH A. T., GOW A. G., POWELL R., CORCORAN B., SCHOEMAN J. P. & SUMMERS K. M. (2013) Population structure and genetic heterogeneity in popular dog breeds in the UK. Veterinary Journal 196, 92–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OGDEN R., MELLANBY R. J., CLEMENTS D., GOW A. G., POWELL R. & MCEWING R. (2011) Genetic data from 15 STR loci for forensic individual identification and parentage analyses in UK domestic dogs (Canis lupus familiaris). Forensic Science International. Genetics 6, e63–e65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PEAKALL R. & SMOUSE P.E. (2006) GENALEX6: genetic analysis in Excel. Population genetic software for teaching and research. Molecular Ecology Notes 6, 288–295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- PRITCHARD J. K., STEPHENS M. & DONNELLY P. (2000) Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics 155, 945–959 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SUMMERS J. F., DIESEL G., ASHER L., MCGREEVY P. D. & COLLINS L. M. (2010) Inherited defects in pedigree dogs. Part 2: Disorders that are not related to breed standards. Veterinary Journal 183, 39–45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- THOMASSEN R. & FARSTAD W. (2009) Artificial insemination in canids: a useful tool in breeding and conservation. Theriogenology 71, 190–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WADE C.M. (2011) Inbreeding and genetic diversity in dogs: results from DNA analysis. Veterinary Journal 189, 183–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]