Abstract

Background

Exercise treatment is recommended for all patients with hip osteoarthritis (OA), but its effect on the long-term need for total hip replacement (THR) is unknown.

Methods

We conducted a long-term follow-up of a randomised trial investigating the efficacy of exercise therapy and patient education versus patient education only on the 6-year cumulative survival of the native hip to THR in 109 patients with symptomatic and radiographic hip OA. Results regarding the primary outcome measure of the trial, self-reported pain at 16 months follow-up, have been reported previously.

Results

There were no group differences at baseline. The response rate at follow-up was 94%. 22 patients in the group receiving both exercise therapy and patient education and 31 patients in the group receiving patient education only underwent THR during the follow-up period, giving a 6-year cumulative survival of the native hip of 41% and 25%, respectively (p=0.034). The HR for survival of the native hip was 0.56 (CI 0.32 to 0.96) for the exercise therapy group compared with the control group. Median time to THR was 5.4 and 3.5 years, respectively. The exercise therapy group had better self-reported hip function prior to THR or end of study, but no significant differences were found for pain and stiffness.

Conclusions

Our findings in this explanatory study suggest that exercise therapy in addition to patient education can reduce the need for THR by 44% in patients with hip OA. ClinicalTrials.gov number NCT00319423 (original project protocol) and NCT01338532 (additional protocol for long-term follow-up).

Keywords: Osteoarthritis, Physcial therapy, Rehabilitation, Orthopedic Surgery

Introduction

Physical activity and patient information is recommended for all patients with osteoarthritis (OA) of the hip and knee as first-line treatment. Total joint replacement surgery is to be considered in cases of advanced disease with severe pain and functional limitations where other treatment options have failed.1 2 Exercise therapy is found to be beneficial in reducing pain and improving function in lower limb OA,3–6 but evidence for this is primarily based on studies including patients with knee OA. In hip OA, exercise interventions have shown promising results,7–9 but the need for high-quality clinical trials with sufficient follow-up time is emphasised.3 4 6 Based on the general consensus that total joint replacement surgery is appropriate only in advanced stages of the disease, joint replacement surgery may be used as an endpoint to evaluate disease progression.10–14 It is unknown whether exercise therapy can influence the progression of OA and thereby reduce the need for total joint replacement.

The main objective of this study was therefore to evaluate the long-term effect of exercise therapy in addition to patient education on the patient's need for total hip replacement (THR). Our null hypothesis was that there would be no difference in cumulative survival of the native hip to THR in patients with hip OA going through exercise therapy and patient education compared with patient education only.

Methods

Study design and patients

This is a long-term follow-up of a randomised, controlled trial evaluating the effect of exercise therapy and patient education in patients with hip OA.9 Inclusion criteria were age between 40 and 80 years, hip pain for at least 3 months, radiographically verified minimum joint space according to Danielsson's criterion15 (<4 mm for patients <70 years, <3 mm for patients >70 years) and Harris Hip Score between 60 and 95 points.16 In patients with bilateral hip OA, the most painful hip was defined as the index joint. Night pain and Harris Hip Score below 60 are used as criteria for THR at our institution.9 Thus, the patients included in the study were not candidates for THR at the time of inclusion, and none of them were on waiting lists for THR. Exclusion criteria were THR in the index joint, knee pain or knee OA, low back pain, rheumatoid arthritis, osteoporosis, cancer, cardiovascular disease unable to tolerate exercise, dysfunction in lower extremities due to accident or disease, pregnancy and not understanding Norwegian. Patient recruitment and screening for inclusion has been described previously, together with the results of the primary outcome measure for this trial.9

Randomisation and treatment groups

All included patients were given three group sessions of a patient education programme developed for patients with hip OA.17 Thereafter they were randomised to either an exercise therapy group or a control group.9 A computer-generated randomisation list (block length 10, allocation ratio 1:1) was conducted by a statistician prior to inclusion. Sequentially numbered, sealed envelopes were used to assign treatment for patients consecutively by a research coordinator not involved in the patient assessment or interventions. Allocation concealment was maintained until written informed consent was obtained, and baseline assessments and patient education sessions were completed. The randomisation sequence was concealed from the study collaborators until treatment was assigned. The exercise therapy programme was specifically designed for patients with hip OA18 and consisted of strengthening, flexibility and functional exercises. Patients in the exercise therapy group performed the exercise programme two to three times per week for 12 weeks, supervised by a physical therapist at least once weekly. Compliance was based on training diaries filled in weekly by the patients in the exercise therapy group during the 12-week intervention period. Attending at least 20 of a total of 24 sessions was defined as satisfactory adherence. Patients in the control group attended a 2-month follow-up visit at the physiotherapy clinic as part of the patient education programme. They did not have access to the exercise therapy programme during the intervention period.

Outcome measures and follow-up

Characteristics of the patients’ included age, gender, height, weight, work status, education level, unilateral or bilateral hip pain, pain duration, minimum joint space and Harris Hip Score.

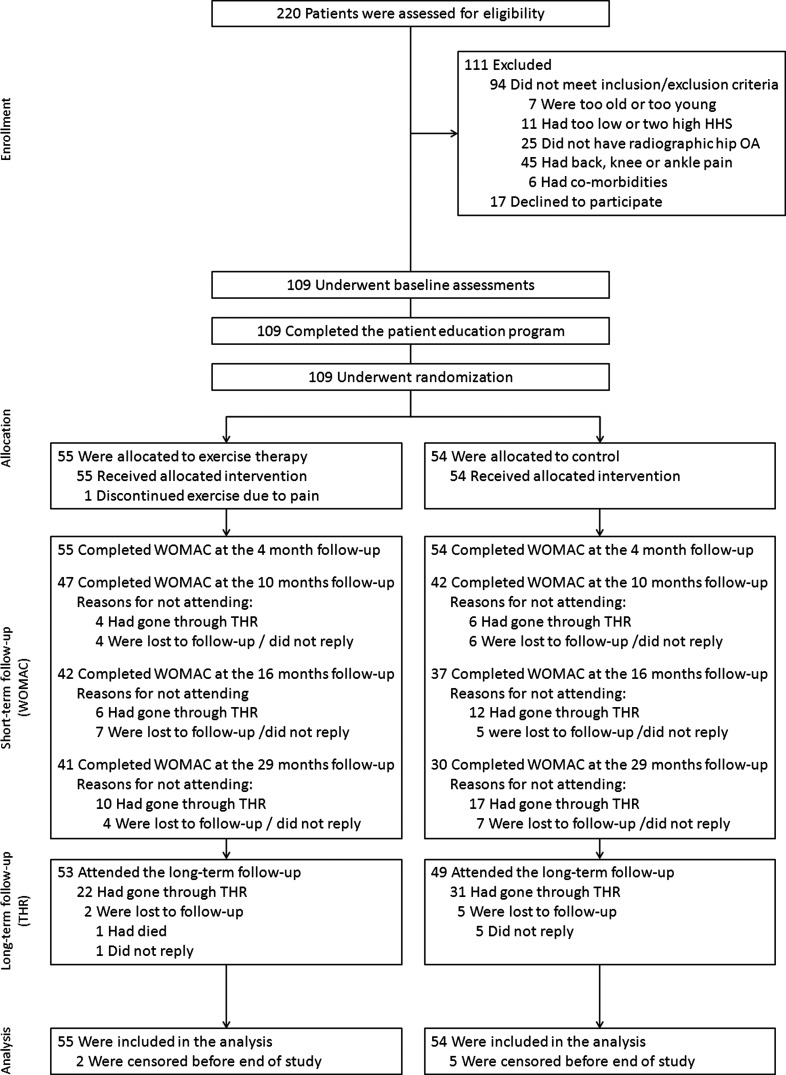

The main outcome measure for this long-term follow-up was survival of the native hip to THR in the index joint. At inclusion all patients were instructed to report if and when they went through THR surgery during the project period. Additionally, data on THR were recorded at follow-ups 4, 10, 16 and 29 months after inclusion and by contacting all patients by telephone in April and May 2011 (figure 1). The outcome assessor was blinded to group allocation. The mean time from inclusion till the end of study at 15 May 2011 was 4.8 years, ranging from 3.6 to 6.1 years.

Figure 1.

Enrolment, randomisation and follow-up of patients.

The Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC)19 and the Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly (PASE)20 were filled in at baseline and at the 4-, 10-, 16- and 29-month follow-up. In this long-term follow-up study, WOMAC was used to assess symptoms and functional limitations prior to THR surgery or end of study. PASE is a brief, self-administered, 7-day recall questionnaire to assess physical activity in older adults. The Norwegian version was used, which consisted of 24 questions giving a total score ranging from 0 to 315.21 Data on training sessions per week were collected at baseline and at 4 months, data on engagement in strength training and flexibility training were collected at 16 and 29 months, and data on physical therapy treatment were collected at 10, 16 and 29 months.

Statistical analysis

Patients were followed until time of THR in the index joint or until death, drop-out or end of study. A Kaplan–Meier survival analysis was constructed to evaluate cumulative 6-year survival, and group difference was tested by the log rank test. THR in the index joint was defined as event, while patients who were lost to follow-up, were dead or were followed until the end of study were treated as censored in the analysis. Time to THR is reported as median and 95% CI. A Cox proportional hazard model was used to calculate HR and 95% CI between groups. No adjusted analysis was conducted due to equality of groups at baseline. Baseline comparisons were performed with Student t tests and χ2 tests. A linear mixed model (variance component model), with time and the interaction of time and group as fixed effects and time as random effect intercept and slope, was used to compare WOMAC scores between the exercise therapy group and the control group over the 29-month follow-up period. A linear mixed model was also applied to compare WOMAC scores prior to THR surgery or end of study between patients who went through THR and patients who did not. The analyses were based on the intention to treat principle. For the outcome measures of physical activity and exercise, mean (SD) or number was calculated, and a linear mixed model was used to compare PASE scores between the exercise therapy group and the control group. p Values below 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Analyses were performed by IBM SPSS Statistics, V.19.0 (IBM Corp., Somers, New York, USA).

Results

Characteristics of the patients

Two hundred and twenty patients were screened for eligibility between April 2005 and October 2007. One hundred and nine patients were included in the trial and randomised to the exercise therapy group or the control group (figure 1). Baseline data were similar in the two intervention groups (table 1). The patients completed a median of 20 (IQR 16–24) exercise sessions over the 12-week period, with 53% completing ≥20 exercise sessions. One patient discontinued exercise after three sessions due to increasing hip pain. No other adverse events were registered.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study patients*

| Exercise therapy group (n=55) | Control group (n=54) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 58.4±10.0 | 57.2±9.8 |

| Female sex, no. (%) | 31 (56.4) | 28 (51.9) |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 24.6±3.2 | 24.9±3.8 |

| Minimum joint space in target joint† (mm) | 2.1±1.0 | 1.9±1.1 |

| Pain duration (months) | 47.3±53.3 | 49.5±50.9 |

| Harris Hip Score‡ | 79.6±7.7 | 76.9±8.2 |

| Bilateral radiographic hip OA, no. (%) | 38 (69.1) | 38 (70.3) |

| THR in contralateral hip at inclusion, no. (%) | 4 (7.3) | 2 (3.7) |

| Hereditary OA/known OA in family, no. (%) | 17 (33.3) | 21 (38.9) |

| >12 years of education, no. (%) | 43 (78.2) | 35 (67.3) |

| Work status | ||

| Employed, no. (%) | 35 (63.6) | 36 (66.7) |

| Sick leave, no. (%) | 8 (14.5) | 5 (9.3) |

| Retired, no. (%) | 12 (21.8) | 9 (16.7) |

| WOMAC score§ | ||

| Pain subscale | 26.0±16.1 | 27.3±17.9 |

| Stiffness subscale | 34.8±23.7 | 34.3±20.5 |

| Physical function subscale | 21.1±15.3 | 23.6±15.7 |

*Plus-minus values are mean±SD. The body mass index is the weight in kilograms divided by the square of the height in metres.

†The minimum joint space in the hip joint was assessed according to Danielsson's criterion.15 For patients older than 70 years, a minimum joint space below 3 mm was characterised as radiographic hip OA. For patients younger than 70 years, a minimum joint space below 4 mm was characterised as radiographic hip OA.

‡The Harris Hip Score is a clinician-administered tool to evaluate hip pain, hip function and hip range of motion.16 An overall score is calculated ranging from 0 to 100, with a lower score indicating more severe disease.

§The Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) comprise three subscales (pain, stiffness and physical function) composed of 24 questions. Scores range from 0 to 100, with a higher score indicating more severe disease.19

OA, osteoarthritis; THR, total hip replacement.

Data on whether THR had been performed were obtained from 102 patients. One patient died and was treated as censored at the time of death. The remaining six patients were treated as censored at the time of last follow-up or contact during the follow-up period. Patients who were censored before the end of study did not differ at baseline from those attending the long-term follow-up.

A total of 41 patients in the exercise therapy group and 30 patients in the control group completed WOMAC at the 29-month follow-up (figure 1). Also, 27 patients had gone through THR prior to the 29-month follow-up and 11 patients were lost to follow-up at the 29-month follow-up.

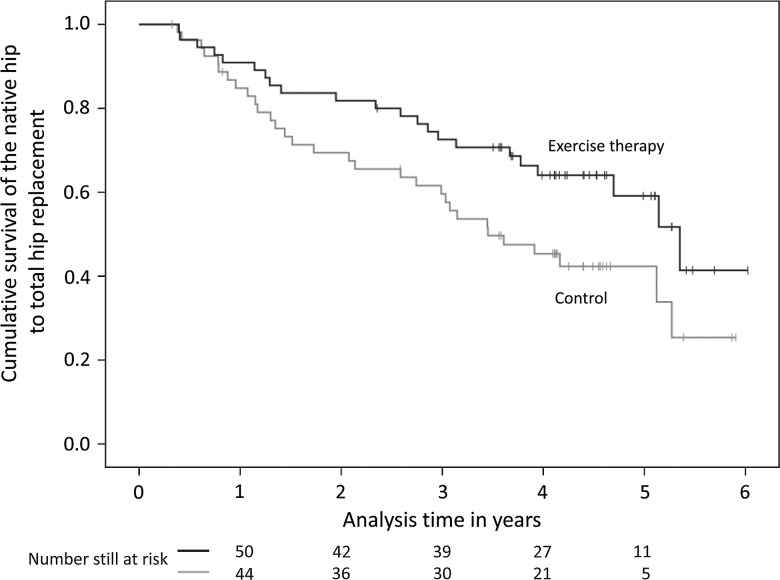

THRs and cumulative survival of native hip

A total of –22 patients in the exercise therapy group and 31 patients in the control group went through THR within the 3.6–6.1 years follow-up period. Estimated median time to THR was 5.4 (CI 4.5 to 6.2) years in the exercise therapy group and 3.5 (CI 2.3 to 4.6) years in the control group. The Kaplan–Maier analysis showed that the cumulative 6-year survival of the native hip to THR was 0.41 in the exercise therapy group compared with 0.25 in the control group (p=0.034) (figure 2). Cox proportional hazard analysis showed that participating in both exercise therapy and patient education had a protective effect against THR compared with patient education only (HR=0.56, CI 0.32 to 0.96, p=0.036). Thirty-five per cent of the patients went through THR surgery at the Oslo University Hospital, and the remaining 65% went through surgery at 1 of 11 other hospitals in the southern parts of Norway. None of the non-operated patients reported to be on waiting list for THR at the end of study.

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier survival estimates over the 6-year follow-up period. The black line represents the exercise therapy group, and the grey line represents the control group. Censored data are marked at each line. The number of patients at risk is given for each year for each group.

Self-reported pain, stiffness and function

Over the 29-month WOMAC follow-up period, the exercise therapy group had significantly better WOMAC physical function scores compared with the control group (p=0.004), but the between-group differences in the WOMAC pain (p=0.083) and WOMAC stiffness (p=0.112) scores did not reach statistical significance (table 2).

Table 2.

Difference in self-reported pain, stiffness and function at baseline and at the 4-, 10-, 16- and 29-month follow-up between the exercise therapy group and the control group, and between the patients who went through THR surgery and the patients who did not*

| Baseline | 4 months | 10 months | 16 months | 29 months | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean difference (95% CI) between the exercise therapy group and the control group | |||||

| WOMAC† | |||||

| Pain | −1.3 (−8.0 to 5.3) | −4.7 (−11.4 to 1.9) | −6.6 (−13.9 to 0.8) | −6.5 (−14.3 to 1.3) | −5.9 (−14.2 to 2.4) |

| Stiffness | 0.5 (−8.0 to 9.1) | −3.5 (−12.0 to 5.0) | −6.3 (−15.8 to 3.2) | −12.5 (−22.5 to −2.5) | −3.9 (−14.6 to 6.7) |

| Physical function | −2.5 (−8.7 to 3.7) | −4.6 (−10.7 to 1.6) | −8.4 (−15.2 to −1.6) | −9.2 (−16.5 to −1.9) | −6.4 (−14.1 to −1.3) |

| Mean difference (95% CI) between the patients who underwent THR‡ (n=53) and the patients who did not (n=56) | |||||

| WOMAC† | |||||

| Pain | 0.1 (−6.4 to 6.7) | 5.6 (−0.9 to 12.1) | 11.9 (4.7 to 19.1) | 9.3 (1.5 to 17.1) | 13.2 (4.6 to 21.8) |

| Stiffness | 4.1 (−4.3 to 12.5) | 9.5 (1.1 to 17.8) | 10.6 (1.3 to 19.9) | 15.2 (5.2 to 25.2) | 12.7 (1.7 to 23.8) |

| Physical function | 5.0 (−0.9 to 11.0) | 8.9 (2.9 to 14.8) | 11.9 (5.3 to 18.4) | 13.3 (6.2 to 20.4) | 15.1 (7.3 to 23.0) |

*Plus-minus values are mean±SD.

†The Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) comprise three subscales (pain, stiffness and physical function) composed of 24 questions. Scores range from 0 to 100, with a higher score indicating more severe disease.19

‡Results for patients who went through THR are preoperative results up until time of surgery.

THR, total hip replacement.

Mean minimum joint space at baseline was 1.5±0.9 mm in patients who went through THR compared with 2.5±1.0 mm in the patients who did not (p<0.01). At baseline there were no significant differences between patients who went through THR and patients who did not in neither WOMAC pain (p=0.967), WOMAC stiffness (p=0.333) nor WOMAC physical function (p=0.092). The 53 patients who underwent THR before the end of study had worse preoperative score in all WOMAC subscales over the 29-month WOMAC follow-up period compared with the patients who did not go through THR or were censored at the end of study (p<0.01) (table 2).

Self-reported physical activity and exercise

The number of self-reported exercise sessions per week was similar in the two groups. At the 16-month follow-up, 75 patients replied to the questions on exercise and physical therapy, and at the 29-month follow-up 70 patients replied (table 3). There was no significant difference in PASE scores between the exercise therapy group and the control group over the 29-month follow-up period (p=0.397).

Table 3.

Self-reported physical activity in the exercise therapy group and the control group at baseline and at the 4-, 10-, 16- and 29-month follow-up*

| Baseline | 4 months | 10 months | 16 months | 29 months | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exercise therapy group | |||||

| PASE score† | 114±43.5 | 115±52.9 | 118±48.6 | 123±50.7 | 120±46.8 |

| Exercise sessions per week | 3.2±2.0 | 3.7±1.9 | |||

| Engaged in strength training—no | 22 | 21 | |||

| Engaged in flexibility training—no | 29 | 27 | |||

| Physical therapy treatment—no | 14 | 16 | 14 | ||

| Control group | |||||

| PASE score† | 123±50.6 | 121±45.4 | 126±57.3 | 133±57.3 | 139±59.2 |

| Exercise sessions per week | 3.2±2.1 | 3.7±2.0 | |||

| Engaged in strength training—no | 24 | 18 | |||

| Engaged in flexibility training—no | 25 | 22 | |||

| Physical therapy treatment—no | 18 | 13 | 20 | ||

*Plus-minus values are mean±SD.

Discussion

Participating in both exercise therapy and patient education resulted in significantly higher 6-year cumulative survival of the native hip to THR compared with patient education only. Thus, the null hypothesis was rejected. The cumulative survival of the native hip was higher in the exercise therapy group from 1 year and throughout the follow-up period.

This is the first study to evaluate whether exercise therapy affects the need for THR in patients with isolated hip OA. One previous study has used total joint replacement as an outcome to compare the effect of individually tailored exercises and usual care in knee and/or hip OA.22 They found that 20% underwent THR in the individually tailored exercise therapy group compared with 45% in the usual care group for those with hip OA. The probability for THR within 5 years was 2.87 (95% CI 1.1 to 7.3) times higher in the usual care group.22 In our study, 40% in the exercise therapy group and 57% in the control group underwent THR, with the control group having 1.80 times higher probability of THR. The somewhat smaller protective effect of exercise in our study may be due to the patients having both symptomatic and radiographic hip OA. Pisters et al22 based inclusion on the clinical criteria of the American College of Rheumatology alone, which does not include radiographic evidence of OA.

Previous studies have reported that 24–53% of patients with symptomatic and radiographic hip OA undergo THR during follow-up ranging from 14 months to 10 years.15 23 24 THR rates have increased steadily during the past four decades,25 which in turn has enlarged healthcare costs substantially.26 Our finding, that exercise therapy enhances the survival of the native hip to THR, is therefore important for healthcare consumption and for patients who may avoid surgery and its potential complications. Some studies have recommended and used total joint replacement as a hard endpoint in OA,10 27–29 but it is debatable whether it can be interpreted as an expression for OA progression. Attempts are requested26 and have been made,30 but still no clearly defined criteria for THR exist. Worse self-reported pain and functional limitations are associated with a higher THR rate,31 but cannot be used to discriminate between patients who are or are not in need of a THR as clinical severity varies widely.30 32 In our study, the patients who went through THR had poorer scores in the WOMAC subscales for pain, stiffness and physical function prior to THR compared with the patients who did not undergo THR. This supports the assumption that the patients who undergo THR surgery have more severe symptoms and functional limitations. Also, the patients who went through THR had smaller minimum joint space at baseline. Abadie et al13 stated that THR is probably the most relevant clinical endpoint for evaluating effect of disease-modifying treatment, but it is potentially biased by non-disease-related factors such as economic factors, availability and geographical differences, comorbidities and contraindications for surgery, and willingness to undergo surgery.12 13 However, in a randomised design study, equal distribution of potential confounding factors is assumed.

Other studies have found beneficial short-term effects of exercise therapy.7 8 No significant difference in self-reported pain was demonstrated in the 16-month follow-up of our trial, but the patients in the exercise therapy group had better self-reported physical function compared with the control group.9 This was supported by the findings in our study, with the exercise therapy group demonstrating better results in WOMAC physical function compared with the control group over the complete 29-month follow-up period (p=0.004), The differences in WOMAC pain (p=0.083) and WOMAC stiffness (p=0.112) did not reach statistical significance. This may indicate that the lower rate and longer time to THR in the exercise therapy group are due to better hip function, with or without the presence of pain. Ten patients in the exercise therapy group and 17 patients in the control group had gone through THR surgery prior to the 29-month follow-up, and it is not unlikely that this uneven distribution of performed THRs has biased the WOMAC results, giving an underestimation of the treatment effect of exercise therapy. Pisters et al22 found no long-term differences in pain and function when comparing individually tailored exercises and usual care, but suggested that patients who underwent THR may have biased the results. Fifty-three per cent of the patients in the exercise therapy group completed ≥20 exercise sessions and were thus regarded as compliant. Data on continuation of the exercise therapy programme after the 12-week intervention period were not obtained, and this must be regarded as a limitation of the study. However, the data on physical activity, exercise and physical therapy treatment suggest that no major between-group differences were present. Self-reported outcome measures lack validity for measuring physical activity and exercise due to recall bias and overestimation of time, frequency and intensity,33 and these data should therefore be interpreted with caution. Better adherence to exercises has been shown to improve long-term results,34 and higher leisure time physical activity may have a protective effect against THR.35

Our study had some limitations. The criteria for when THR surgery was indicated were not specified prior to the start of the study. The criteria used for THR at our institution (night pain and Harris Hip Score below 60 points) are not necessarily used at other hospitals, and the symptom state may differ at time of surgery. Preoperative assessment was not conducted, but pain and physical function were assessed with a mean time of 0.7±0.8 years prior to THR. Calculation of statistical power for this study was not based on survival of the native hip to THR, but rather the WOMAC pain subscale, which was the primary outcome measure of this trial.9

Some caution should be taken when interpreting these results. Our findings are applicable for patients with symptomatic and radiographic hip OA, with mild to moderate symptoms. Patients with severe symptoms and patients with knee or back pain were excluded. Patients recruited to non-surgical treatment trials may have a stronger desire to avoid surgery compared with the general OA population.12 It is debatable whether postponing surgery is beneficial for the patients in the long term.36 37 We argue that for patients with tolerable pain who are able to maintain their desired activity level and who are relatively young postponing surgery is appropriate and may reduce the future need for THR or repetitive THR revision surgery.

Conclusions

Our findings in this explanatory study show that participating in a 12-week exercise therapy programme in addition to patient education can reduce the need for THR or postpone surgery in patients with hip OA. This supports the recommendations stating that exercise therapy should be offered to patients with hip OA as first-line treatment.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the patients who participated in this trial; the physiotherapists Karin Rydevik, Sigmund Ruud, Emilie Jul-Larsen Aas, Marie Moltubakk and Marte Lund for their contribution in leading the patient education programme, supervising the patients during the exercise therapy intervention or conducting the outcome assessments; the research coordinator Kristin Bølstad for study management; and Leiv Sandvik and Ingar Holme for help and advice on statistical procedure and analysis. The Norwegian Sports Medicine Clinic (NIMI), Oslo, Norway, is acknowledged for supporting the Norwegian Research Center for Active Rehabilitation with rehabilitation facilities and research staff.

Footnotes

Correction notice: This article has been corrected since it was published Online First. The affiliation of the last author has been corrected.

Contributors: All authors contributed to the development of the protocol and were involved in the conduct of the study. MAR was responsible for the project funding. LN and LF contributed to clinical screening of participants and LN assessed all radiographs. LF and IS carried out the outcome assessments. IS performed the statistical analysis and drafted the manuscript. All authors revised and approved the final manuscript. MAR acts as a guarantor for this study.

Funding: This study was supported by grants from the former science council at Ullevaal University Hospital, Oslo, and the EXTRA funds from the Norwegian Foundation for Health and Rehabilitation, through the Norwegian Rheumatism Association.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent : Obtained

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the regional medical research ethics committee and was carried out in compliance with the Helsinki Declaration.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Dieppe PA, Lohmander LS. Pathogenesis and management of pain in osteoarthritis. Lancet 2005;365:965–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lohmander LS, Roos EM. Clinical update: treating osteoarthritis. Lancet 2007;370:2082–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang W, Nuki G, Moskowitz RW, et al. OARSI recommendations for the management of hip and knee osteoarthritis: part III: Changes in evidence following systematic cumulative update of research published through January 2009. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2010;18:476–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fransen M, McConnell S, Hernandez-Molina G, et al. Exercise for osteoarthritis of the hip. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2009;3:CD007912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fransen M, McConnell S. Exercise for osteoarthritis of the knee. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2008;4:CD004376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hernandez-Molina G, Reichenbach S, Zhang B, et al. Effect of therapeutic exercise for hip osteoarthritis pain: results of a meta-analysis. Arthritis Rheum 2008;59:1221–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tak E, Staats P, Van HA, et al. The effects of an exercise program for older adults with osteoarthritis of the hip. J Rheumatol 2005;32:1106–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Juhakoski R, Tenhonen S, Malmivaara A, et al. A pragmatic randomized controlled study of the effectiveness and cost consequences of exercise therapy in hip osteoarthritis. Clin Rehabil 2010;25:370–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fernandes L, Storheim K, Sandvik L, et al. Efficacy of patient education and supervised exercise vs patient education alone in patients with hip osteoarthritis: a single blind randomized clinical trial. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2010;18:1237–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dougados M, Gueguen A, Nguyen M, et al. Requirement for total hip arthroplasty: an outcome measure of hip osteoarthritis? J Rheumatol 1999;26:855–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maillefert JF, Hawker GA, Gossec L, et al. Concomitant therapy: an outcome variable for musculoskeletal disorders? Part 2: total joint replacement in osteoarthritis trials. J Rheumatol 2005;32:2449–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Altman RD, Abadie E, Avouac B, et al. Total joint replacement of hip or knee as an outcome measure for structure modifying trials in osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2005;13:13–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abadie E, Ethgen D, Avouac B, et al. Recommendations for the use of new methods to assess the efficacy of disease-modifying drugs in the treatment of osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2004;12:263–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dieppe P. Osteoarthritis: time to shift the paradigm. This includes distinguishing between severe disease and common minor disability. BMJ 1999;318:1299–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Danielsson LG. Incidence and prognosis of coxarthrosis. 1964. Acta Orthop Scandi 1964;66(Suppl):61–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harris WH. Traumatic arthritis of the hip after dislocation and acetabular fractures: treatment by mold arthroplasty. An end-result study using a new method of result evaluation. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1969;51:737–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Klassbo M, Larsson G, Harms-Ringdahl K. Promising outcome of a hip school for patients with hip dysfunction. Arthritis Rheum 2003;49:321–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fernandes L, Storheim K, Nordsletten L, et al. Development of a therapeutic exercise program for patients with osteoarthritis of the hip. Phys Ther 2010;90:592–601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bellamy N, Buchanan WW, Goldsmith CH, et al. Validation study of WOMAC: a health status instrument for measuring clinically important patient relevant outcomes to antirheumatic drug therapy in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee. J Rheumatol 1988;15:1833–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Washburn RA, Smith KW, Jette AM, et al. The Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly (PASE): development and evaluation. J Clin Epidemiol 1993;46:153–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Loland NW. Reliability of the physical activity scale for the elderly (PASE). Eur J Sports Sci 2002;2:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pisters MF, Veenhof C, Schellevis FG, et al. Long-term effectiveness of exercise therapy in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee: a randomized controlled trial comparing two different physical therapy interventions. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2010;18:1019–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ledingham J, Dawson S, Preston B, et al. Radiographic progression of hospital referred osteoarthritis of the hip. Ann Rheum Dis 1993;52:263–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lane NE, Nevitt MC, Hochberg MC, et al. Progression of radiographic hip osteoarthritis over eight years in a community sample of elderly white women. Arthritis Rheum 2004;50:1477–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Singh JA, Vessely MB, Harmsen WS, et al. A population-based study of trends in the use of total hip and total knee arthroplasty, 1969–2008. Mayo Clin Proc 2010;85:898–904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ghomrawi HM, Schackman BR, Mushlin AI. Appropriateness criteria and elective procedures—total joint arthroplasty. N Engl J Med 2012;367:2467–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dougados M, Nguyen M, Berdah L, et al. Evaluation of the structure-modifying effects of diacerein in hip osteoarthritis: ECHODIAH, a three-year, placebo-controlled trial. Evaluation of the Chondromodulating Effect of Diacerein in OA of the Hip. Arthritis Rheum 2001;44:2539–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bruyere O, Honore A, Ethgen O, et al. Correlation between radiographic severity of knee osteoarthritis and future disease progression. Results from a 3-year prospective, placebo-controlled study evaluating the effect of glucosamine sulfate. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2003;11:1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Migliore A, Bella A, Bisignani M, et al. Total hip replacement rate in a cohort of patients affected by symptomatic hip osteoarthritis following intra-articular sodium hyaluronate (MW 1,500–2,000 kDa) ORTOBRIX study. Clin Rheumatol 2012;31:1187–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gossec L, Paternotte S, Bingham CO, III, et al. OARSI/OMERACT initiative to define states of severity and indication for joint replacement in hip and knee osteoarthritis. An OMERACT 10 Special Interest Group. J Rheumatol 2011;38:1765–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lofvendahl S, Bizjajeva S, Ranstam J, et al. Indications for hip and knee replacement in Sweden. J Eval Clin Pract 2011;17:251–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dieppe P, Judge A, Williams S, et al. Variations in the pre-operative status of patients coming to primary hip replacement for osteoarthritis in European orthopaedic centres. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2009;10:19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Svege I, Kolle E, Risberg MA. Reliability and validity of the Physical Activity Scale for the Elderly (PASE) in patients with hip osteoarthritis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2012;13:26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pisters MF, Veenhof C, Schellevis FG, et al. Exercise adherence improving long-term patient outcome in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip and/or knee. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2010;62:1087–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ageberg E, Engstrom G, Gerhardsson de Verdier M, et al. Effect of leisure time physical activity on severe knee or hip osteoarthritis leading to total joint replacement: a population-based prospective cohort study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2012;13:73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fortin PR, Penrod JR, Clarke AE, et al. Timing of total joint replacement affects clinical outcomes among patients with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee. Arthritis Rheum 2002;46:3327–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vergara I, Bilbao A, Gonzalez N, et al. Factors and consequences of waiting times for total hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2011;469:1413–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]