Abstract

Objectives

To evaluate clinical remission with subcutaneous abatacept plus methotrexate (MTX) and abatacept monotherapy at 12 months in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis (RA), and maintenance of remission following the rapid withdrawal of all RA treatment.

Methods

In the Assessing Very Early Rheumatoid arthritis Treatment phase 3b trial, patients with early active RA were randomised to double-blind, weekly, subcutaneous abatacept 125 mg plus MTX, abatacept 125 mg monotherapy, or MTX for 12 months. Patients with low disease activity (Disease Activity Score (DAS)28 (C reactive protein (CRP)) <3.2) at month 12 entered a 12-month period of withdrawal of all RA therapy. The coprimary endpoints were the proportion of patients with DAS28 (CRP) <2.6 at month 12 and both months 12 and 18, for abatacept plus MTX versus MTX.

Results

Patients had <2 years of RA symptoms, DAS28 (CRP) ≥3.2, anticitrullinated peptide-2 antibody positivity and 95.2% were rheumatoid factor positive. For abatacept plus MTX versus MTX, DAS28 (CRP) <2.6 was achieved in 60.9% versus 45.2% (p=0.010) at 12 months, and following treatment withdrawal, in 14.8% versus 7.8% (p=0.045) at both 12 and 18 months. DAS28 (CRP) <2.6 was achieved for abatacept monotherapy in 42.5% (month 12) and 12.4% (both months 12 and 18). Both abatacept arms had a safety profile comparable with MTX alone.

Conclusions

Abatacept plus MTX demonstrated robust efficacy compared with MTX alone in early RA, with a good safety profile. The achievement of sustained remission following withdrawal of all RA therapy suggests an effect of abatacept's mechanism on autoimmune processes.

Trial registration number

Keywords: Rheumatoid Arthritis, Methotrexate, DMARDs (biological), Disease Activity

Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a progressive disease characterised by chronic joint inflammation and subsequent structural damage.1 There may be a ‘window of opportunity’ in early RA to alter the course of the disease if tightly controlled, which diminishes once the inflammatory processes are more established.2 If so, this could aid decisions on the use of a combination of biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARD) and conventional synthetic (cs)DMARDs versus step-up therapy in early RA.3 Once RA is well controlled, the ability to sustain remission following the withdrawal of immunomodulatory medications would be an indication of disease modification.

Abatacept, a fusion protein of cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen-4 and immunoglobulin G1, selectively modulates the CD80/CD86:CD28 costimulatory signal required for full T-cell activation.4 Due to a greater impact on naive T cells, there is a rationale for the use of abatacept in early RA; the unique upstream mechanism of abatacept impacts downstream inflammatory mediators and autoantibodies, and may allow removal of drug therapy. In the Abatacept study to Gauge Remission and joint damage progression in methotrexate naïve patients with Early Erosive rheumatoid arthritis (AGREE), after all patients had completed 2 years of abatacept treatment, 50 patients had a dose reduction from 10 mg/kg to 5 mg/kg without change in efficacy.5 In patients with undifferentiated and early RA in the Abatacept study to Determine the effectiveness in preventing the development of rheumatoid arthritis in patients with Undifferentiated inflammatory arthritis and to evaluate Safety and Tolerability (ADJUST), abatacept was withdrawn following 6 months of monotherapy, and maintained inhibition of joint damage progression for 6 months after withdrawal.6 Similarly, in a study of patients with type 1 diabetes, the treatment effect observed with abatacept was maintained for a year following drug withdrawal.7

In this phase 3b trial, we evaluated the efficacy and safety of subcutaneous (SC) abatacept plus methotrexate (MTX), and abatacept monotherapy versus MTX in inducing clinical remission after 12 months in patients with early RA, and their ability to sustain drug-free remission at 18 months. Whereas a few studies have examined the strategy of achieving disease control followed by various de-escalation approaches reducing either steroids, MTX or biologicals,8–17 this is the first study to investigate the possibility of achieving absolute drug-free remission after removing all RA therapies.

Methods

Study design

Assessing Very Early Rheumatoid arthritis Treatment (AVERT) was a phase 3b, randomised, active-controlled trial of 24 months, with a 12-month, double-blind treatment period (see online figure S1 in the supplementary appendix).

The study population included adults (≥18 years old) with active clinical synovitis of ≥2 joints for ≥8 weeks, persistent symptoms for ≤2 years, Disease Activity Score (DAS)28 (C reactive protein (CRP)) ≥3.2 and anticitrullinated peptide (CCP)-2 antibody positivity (see online table S1 in the supplementary appendix). Patients were MTX naive or received MTX (≤10 mg/week) for ≤4 weeks with no MTX for 1 month prior to enrolment. Patients receiving oral corticosteroids were required to be on a stable dose (≤10 mg/day for ≥4 weeks) at initiation and to maintain that dose until month 12.

In the 12-month treatment period, patients were randomised (1:1:1) to abatacept plus MTX, abatacept monotherapy or MTX, stratified by corticosteroid use at baseline (yes/no) using a Centralised Randomisation System. SC abatacept was administered at 125 mg/week. MTX was initiated at 7.5 mg/week and titrated to 15–20 mg/week within 6–8 weeks (≤10 mg/week permitted in patients with intolerance). All patients received concomitant folic acid therapy.

Patients with DAS28 (CRP) <3.2 at month 12 could enter the 12-month withdrawal period, during which all treatment was stopped; abatacept immediately and MTX and steroids tapered over 1 month. Patients with DAS28 (CRP) ≥3.2 discontinued the study.

After month 15, patients in the withdrawal period who experienced a flare of RA defined as two of the following: doubling of tender and swollen joint counts relative to month 12, increase in DAS28 (CRP) ≥1.2 from month 12, or investigator's judgement of RA flare, were eligible to enter a re-exposure period with open-label SC abatacept 125 mg plus MTX.

All patients underwent contrast MRI of the wrist and hand of the major affected upper limb at baseline and at 6, 12, 18 and 24 months.

The study (NCT01142726) was conducted in accordance with Good Clinical Practice.18–20 Bristol-Myers Squibb (the sponsor) provided the study drug, designed the study, conducted the study in collaboration with the principal investigators, collected the data, monitored the conduct of the study and performed statistical analyses.

Outcome measures

For the purpose of this study, DAS-defined remission was DAS28 (CRP) <2.6. Co-primary endpoints were: the proportion of randomised and treated patients in DAS-defined remission at (A) month 12 and (B) months 12 and 18 for abatacept plus MTX versus MTX.

Secondary endpoints included: DAS-defined remission at (A) month 12 and (B) months 12 and 18 for abatacept monotherapy versus MTX; Health Assessment Questionnaire-Disability Index (HAQ-DI) response (≥0.3 points reduction from baseline); osteitis, synovitis and erosion score by MRI; safety and tolerability. Additional assessments are given in the online supplementary information.

Statistical analyses

A sample size of 116 patients per arm yielded 90% power to detect an expected difference of 22% for the first co-primary endpoint. This power estimate assumed that 60% of patients in the abatacept plus MTX arm and 38% of patients in the MTX arm would achieve DAS-defined remission (DAS28 (CRP) <2.6) at month 12. Conditional on achieving the first co-primary endpoint, a sample size of 116 patients per arm yielded 98% power to detect an expected difference of 22% for the second co-primary endpoint. This power estimate assumed that 30% of patients in the abatacept plus MTX arm and 8% of patients in the MTX arm would achieve DAS-defined remission (DAS28 (CRP) <2.6) at both months 12 and 18.

Co-primary endpoints were tested in hierarchical fashion. ORs (with 95% CIs) were calculated for abatacept plus MTX versus MTX using logistic regression adjusted for treatment group, corticosteroid use at baseline (yes/no) and baseline DAS28 (CRP); patients with missing baseline DAS28 (CRP) were not included. All patients who discontinued prior to completing the treatment or withdrawal period were imputed as non-responders for the month 12 or 18 analyses. Patients who entered the re-exposure period during the withdrawal period, prior to month 18, were imputed as non-responders at month 18.

Adjusted mean MRI change from baseline and SE was calculated for all arms using a longitudinal repeated measures model. Safety assessments were based on the intent-to-treat population (patients who received ≥1 dose of study medication). Analysis of other secondary endpoints is described in the online supplementary information.

Details on posthoc analyses of baseline characteristics of patients who achieved DAS-defined remission, the proportions of patients who achieved DAS-defined remission based on these characteristics, and overall treatment effect on mean change from baseline in DAS28 (CRP) are provided in the online supplementary materials.

Results

Results up to the 18-month co-primary endpoint are presented.

Demographics and baseline characteristics

A total of 511 patients were enrolled, and 351 patients at 72 worldwide sites were randomly assigned to treatment (abatacept plus MTX, n=119; abatacept monotherapy, n=116; MTX, n=116) (see online figure S2 in the supplementary appendix). Patients had early RA (mean symptom duration 0.56 years) with highly inflammatory disease (mean tender joint count 13.6, swollen joint count 11.1 and CRP 17.5 mg/L), severe disease activity (mean DAS28 (CRP) 5.4 and HAQ-DI 1.4) and poor prognostic factors (95.2% rheumatoid factor and anti-CCP-2 double positive) (table 1). The numbers of patients entering the withdrawal period were 84/119 (70.6%), 66/116 (56.9%) and 73/116 (62.9%) in the abatacept plus MTX, abatacept monotherapy and MTX arms, respectively (see online figure S2 in the supplementary appendix).

Table 1.

Demographics and baseline characteristics

| Characteristic | Abatacept plus MTX (n=119) |

Abatacept monotherapy (n=116) |

MTX (n=116) |

Total (N=351) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age—year (median) | 46.4±13.2 (45.0) | 45.4±11.9 (45.0) | 49.1±12.4 (49.0) | 47.0±12.6 (47.0) |

| Weight—kg (median) | 73.0±17.7 (68.7) | 72.1±16.8 (69.5) | 74.1±17.1 (71.5) | 73.1±17.2 (69.9) |

| Female sex—number (%) | 95 (79.8) | 89 (76.7) | 89 (76.7) | 273 (77.8) |

| White race—number (%) | 100 (84.0) | 95 (81.9) | 102 (87.9) | 297 (84.6) |

| Geographic region—number (%) | ||||

| North America | 17 (14.3) | 21 (18.1) | 15 (12.9) | 53 (15.1) |

| South America | 26 (21.8) | 24 (20.7) | 25 (21.6) | 75 (21.4) |

| Europe | 47 (39.5) | 42 (36.2) | 48 (41.4) | 137 (39.0) |

| ROW | 29 (24.4) | 29 (25.0) | 28 (24.1) | 86 (24.5) |

| RA symptom duration—year | 0.58±0.50 | 0.59±0.52 | 0.50±0.49 | 0.56±0.50 |

| RA symptom duration <3 months—number (%) | 36 (30.3) | 36 (31.0) | 48 (41.4) | 120 (34.2) |

| RF positive—number (%) | 113 (95.0) | 111 (95.7) | 110 (94.8) | 334 (95.2) |

| Tender joint count (28 joints) | 14.0±7.7 | 14.0±7.6 | 12.8±7.8 | 13.6±7.7 |

| Swollen joint count (28 joints) | 11.2±6.9 | 11.4±7.66 | 10.7±7.0 | 11.1±7.1 |

| CRP—mg/L | 18.1±28.4 | 16.9±23.9 | 17.3±22.4 | 17.5±25.0 |

| Patient global assessment (0–100 mm VAS) | 62.7±21.0 | 57.3±22.4 | 58.2±19.7 | 59.4±21.1 |

| Physician global assessment (0–100 mm VAS) | 58.4±19.1 | 58.7±20.6 | 58.6±20.3 | 58.6±20.0 |

| DAS28 (CRP) | 5.5±1.3 | 5.5±1.1 | 5.3±1.3 | 5.4±1.2 |

| HAQ-DI | 1.5±0.68 | 1.4±0.66 | 1.4±0.65 | 1.4±0.66 |

| Pain (0–100 mm VAS) | 62.4±20.8 | 61.3±21.6 | 59.5±18.3 | 61.1±20.3 |

| Physical function (0–100, Short Form-36 subscale) | 38.5±25.9 | 41.6±25.6 | 39.1±24.5 | 39.7±25.3 |

Plus-minus values are means±SD.

CRP, C reactive protein; DAS, Disease Activity Score; HAQ-DI, Health Assessment Questionnaire-Disability Index; MTX, methotrexate; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; RF, rheumatoid factor; ROW, rest of the world; VAS, visual analogue scale.

Signs and symptoms

Abatacept plus MTX versus MTX during treatment period

Abatacept plus MTX achieved statistically significantly higher rates of DAS-defined remission versus MTX at month 12 (70/115 (60.9%) patients vs 52/115 (45.2%) patients; OR (95% CI) 2.01 (1.18 to 3.43); p=0.010). Numerically higher DAS-defined remission rates were observed in the abatacept plus MTX group versus MTX from day 57, which were maintained over time for the rest of the treatment period (figure 1A). A posthoc analysis of the overall treatment effect over the 12 months of the treatment period in change from baseline in DAS28 (CRP) demonstrated an estimated treatment difference (95% CI) of –0.52 (–0.74 to –0.30) for abatacept plus MTX versus MTX.

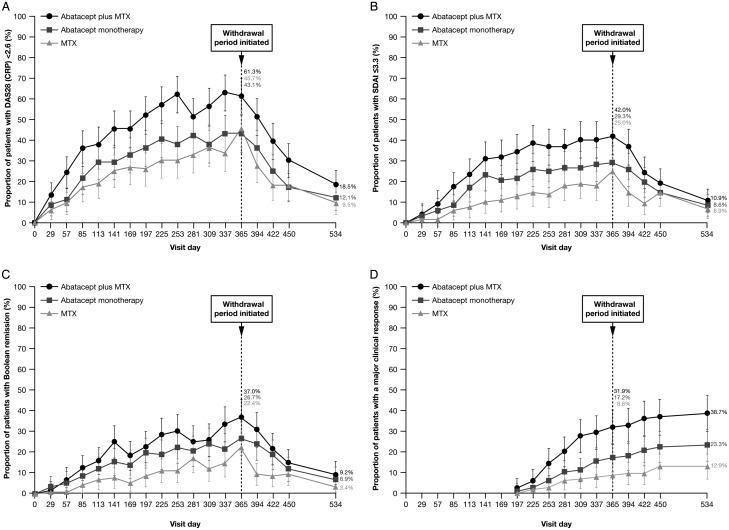

Figure 1.

Efficacy outcomes over time. (A) proportion of patients with DAS-defined remission (DAS28 (CRP) <2.6); (B) proportion of patients with SDAI remission (≤3.3); (C) proportion of patients with Boolean remission (tender joint count ≤1, swollen joint count ≤1, patient global assessment of disease activity ≤1 (0–10 scale), high-sensitivity CRP ≤1 mg/dL); (D) major clinical response (ACR 70 response for a minimum of six consecutive months at any time period prior to the time point). Error bars represent 95% CIs. Missing remission data not due to premature discontinuation and not at day 1 of the treatment period or at day 169 of the withdrawal period were imputed as a remission if the missing value occurred between two observed remissions. Missing ACR response data not due to premature discontinuation and not at day 1 of the treatment period or at day 169 of the withdrawal period were imputed as an ACR response if the missing value occurred between two observed ACR responses. ACR, American College of Rheumatology; CRP, C reactive protein; DAS, Disease Activity Score; MTX, methotrexate; SDAI, Simplified Disease Activity Index.

The proportion of patients achieving other remission endpoints (including Simplified Disease Activity Index (SDAI), Clinical Disease Activity Index (CDAI) and Boolean remission), American College of Rheumatology (ACR) responses and major clinical response (MCR) were numerically greater for abatacept plus MTX versus MTX over time (figure 1 and see online figure S3 in the supplementary appendix); HAQ-DI response rates at month 12 were 65.5% versus 44.0%, respectively (see online table S2 in the supplementary appendix).

Abatacept monotherapy versus MTX during treatment period

Abatacept monotherapy resulted in a similar proportion of patients achieving DAS-defined remission at month 12 compared with MTX (48/113 (42.5%) vs 52/115 (45.2%)). However, over time, DAS-defined remission rates were numerically higher for abatacept monotherapy (figure 1A) at most other time points. In fact, as determined by posthoc analysis, the overall estimated treatment difference (95% CI) between abatacept monotherapy versus MTX in change from baseline in DAS28 (CRP) was –0.26 (–0.11 to –0.48). Additionally, abatacept monotherapy demonstrated numerically higher rates of CDAI, SDAI, Boolean remission and ACR 20/50/70 and MCR rates versus MTX over time (figure 1 and see online figure S3 in the supplementary appendix) and HAQ-DI (see online table S2 in the supplementary appendix).

Abatacept plus MTX and abatacept monotherapy versus MTX during withdrawal period

Abatacept plus MTX achieved statistically significantly higher rates of DAS-defined remission versus MTX at both months 12 and 18 (17/115 (14.8%) patients vs 9/115 (7.8%) patients; OR (95% CI) 2.51 (1.02 to 6.18); p=0.045). The proportion of patients achieving DAS-defined remission at both months 12 and 18 was 14/113 (12.4%) versus 9/115 (7.8%) for abatacept monotherapy and MTX groups, respectively (analysis included only patients with DAS28 (CRP) available at baseline).

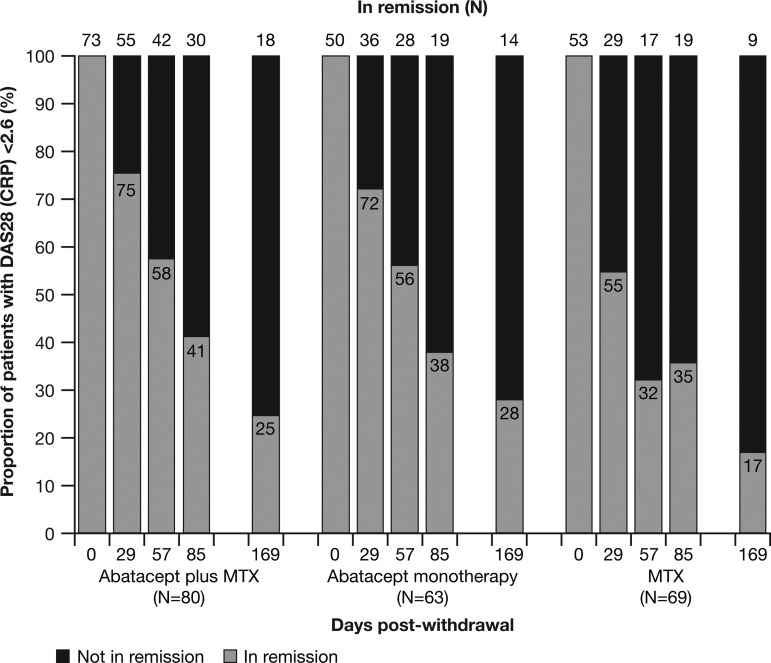

Of the patients who entered the withdrawal period, 73, 50 and 53 patients in each treatment group were in DAS-defined remission at month 12. Of these, 18/73 (24.7%), 14/50 (28%) and 9/53 (17.0%) remained in DAS-defined remission at month 18 (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Proportion of patients in Disease Activity Score (DAS)-defined remission (DAS28 (C reactive protein, CRP) <2.6) during the withdrawal period. The numbers within the bars are percentages. Missing remission data not due to premature discontinuation and not at day 1 of the treatment period or at day 169 of the withdrawal period were imputed as a remission if the missing value occurred between two observed remissions. MTX, methotrexate.

A posthoc analysis indicated that in both abatacept treatment arms the proportions of patients with sustained DAS-defined remission following treatment withdrawal were numerically higher in patients who had lower baseline DAS28 (CRP), lower HAQ-DI and shorter symptom duration; this was not the case in the MTX arm (table 2). The same baseline factors were associated with DAS-defined remission at months 12 and 18 versus DAS-defined remission at month 12 only, also in the abatacept arm (see online table S3 in the supplementary appendix). Patients receiving abatacept also had more time with DAS28 (CRP) <2.6 than patients receiving MTX during the treatment period (10.2 vs 8.1 months for abatacept plus MTX; 8.9 vs 6.6 months for abatacept monotherapy; 5.8 vs 5.7 months for MTX).

Table 2.

Proportion of patients with DAS-defined remission (DAS28 (CRP) <2.6) at both months 12 and 18 by baseline characteristic subgroup (posthoc analyses)

| Baseline characteristic | Abatacept plus MTX (n=119) |

Abatacept monotherapy (n=116) |

MTX (n=116) |

|---|---|---|---|

| DAS28 (CRP) | |||

| Missing—number/N (%) | 1/4 (25.0) | 0/3 (0) | 0/1 (0) |

| ≤Median (5.4)—number/N (%) | 14/56 (25.0) | 12/56 (21.4) | 6/60 (10.0) |

| >Median (5.4)—number/N (%) | 3/59 (5.1) | 2/57 (3.5) | 3/55 (5.5) |

| HAQ-DI, number (%) | |||

| Missing—number/N (%) | 3/6 (50.0) | 1/3 (33.3) | 0/11 (0) |

| ≤Median (1.375)—number/N (%) | 12/58 (20.7) | 10/59 (16.9) | 4/56 (7.1) |

| >Median (1.375)—number/N (%) | 3/55 (5.5) | 3/54 (5.6) | 5/49 (10.2) |

| Symptom duration | |||

| ≤Median (0.37 years)—number/N (%) | 12/58 (20.7) | 7/50 (14.0) | 5/69 (7.2) |

| >Median (0.37 years)—number/N (%) | 6/61 (9.8) | 7/66 (10.6) | 4/47 (8.5) |

| ≤6 months—number/N (%) | 14/70 (20.0) | 11/71 (15.5) | 7/77 (9.1) |

| >6 months—number/N (%) | 4/49 (8.2) | 3/45 (6.7) | 2/39 (5.1) |

| Pain (100 mm VAS) | |||

| Missing—number/N (%) | 3/6 (50.0) | 1/3 (33.3) | 0/11 (0.0) |

| ≤Median (62)—number/N (%) | 11/48 (22.9) | 8/58 (13.8) | 7/60 (11.7) |

| >Median (62)—number/N (%) | 4/65 (6.2) | 5/55 (9.1) | 2/45 (4.4) |

| Erosion | |||

| Missing—number/N (%) | 1/15 (6.7) | 0/14 (0) | 2/13 (15.4) |

| ≤Median (4.5)—number/N (%) | 7/50 (14.0) | 10/58 (17.2) | 4/53 (7.5) |

| >Median (4.5)—number/N (%) | 10/54 (18.5) | 4/44 (9.1) | 3/50 (6.0) |

| ≤Q1 (1.5)—number/N (%) | 4/23 (17.4) | 5/28 (17.9) | 2/30 (6.7) |

| >Q1 (1.5)–Q2 (4.5)—number/N (%) | 3/27 (11.1) | 5/30 (16.7) | 2/23 (8.7) |

| >Q2 (4.5)–Q3 (8.5)—number/N (%) | 8/25 (32.0) | 3/23 (13.0) | 2/23 (8.7) |

| >Q3 (8.5)—number/N (%) | 2/29 (6.9) | 1/21 (4.8) | 1/27 (3.7) |

| Osteitis | |||

| Missing—number/N (%) | 1/15 (6.7) | 0/14 (0) | 2/13 (15.4) |

| ≤Median (0.5)—number/N (%) | 8/54 (14.8) | 10/47 (21.3) | 4/54 (7.4) |

| >Median (0.5)—number/N (%) | 9/50 (18.0) | 4/55 (7.3) | 3/49 (6.1) |

| ≤Q1 (0)—number/N (%) | 6/41 (14.6) | 9/43 (20.9) | 4/49 (8.2) |

| >Q1 (0)–Q2 (0.5)—number/N (%) | 2/13 (15.4) | 1/4 (25.0) | 0/5 (0) |

| >Q2 (0.5)–Q3 (5)—number/N (%) | 7/25 (28.0) | 2/27 (7.4) | 2/26 (7.7) |

| >Q3 (5)—number/N (%) | 2/25 (8.0) | 2/28 (7.1) | 1/23 (4.3) |

| Synovitis | |||

| Missing—number/N (%) | 1/15 (6.7) | 0/14 (0) | 2/13 (15.4) |

| ≤Median (4.5)—number/N (%) | 12/57 (21.1) | 9/52 (17.3) | 4/47 (8.5) |

| >Median (4.5)—number/N (%) | 5/47 (10.6) | 5/50 (10.0) | 3/56 (5.4) |

| ≤Q1 (2)—number/N (%) | 5/30 (16.7) | 4/24 (16.7) | 3/24 (12.5) |

| >Q1 (2)–Q2 (4.5)—number/N (%) | 7/27 (25.9) | 5/28 (17.9) | 1/23 (4.3) |

| >Q2 (4.5)–Q3 (8.5)—number/N (%) | 3/23 (13.0) | 4/33 (12.1) | 1/30 (3.3) |

| >Q3 (8.5)—number/N (%) | 2/24 (8.3) | 1/17 (5.9) | 2/26 (7.7) |

CRP, C reactive protein; DAS, Disease Activity Score; HAQ-DI, Health Assessment Questionnaire-Disability Index; MTX, methotrexate; Q, quartile; VAS, visual analogue scale.

Effect on structural damage

Radiographic changes measured by MRI in each of the treatment groups were consistent with clinical efficacy outcomes. Abatacept plus MTX and abatacept monotherapy resulted in numerically greater decreases from baseline in synovitis and osteitis scores, and abatacept plus MTX resulted in less progression of erosion score than MTX at 12 months (see online figure S4 in the supplementary appendix).

Safety

During the treatment period, adverse events (AE) occurred in 101/119 (84.9%), 93/116 (80.2%) and 96/116 (82.8%) patients treated with abatacept plus MTX, abatacept monotherapy and MTX, respectively (table 3). Serious AEs occurred in 8/119 (6.7%), 14/116 (12.1%) and 9/116 (7.8%) patients; there were 2/119 (1.7%), 5/116 (4.3%) and 3/116 (2.6%) discontinuations due to serious AEs; and serious infections occurred in 1/119 (0.8%), 4/116 (3.4%) and 0 patients, respectively. There were no deaths during the treatment period. During the withdrawal period, two patients died in the MTX arm (uterine neoplasm, renal failure).

Table 3.

Summary of safety in the treatment period*

| Abatacept plus MTX (n=119) |

Abatacept monotherapy (n=116) |

MTX (n=116) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Deaths | 0 | 0 | 0† |

| Adverse events | 101 (84.9) | 93 (80.2) | 96 (82.8) |

| Serious adverse events | 8 (6.7) | 14 (12.1) | 9 (7.8) |

| Discontinuations due to serious adverse events | 2 (1.7) | 5 (4.3) | 3 (2.6) |

| Serious infections | 1 (0.8) | 4 (3.4) | 0 |

| Pneumonia | 1 (0.8) | 1 (0.9) | 0 |

| Limb abscess | 0 | 1 (0.9) | 0 |

| Herpes zoster | 0 | 1 (0.9) | 0 |

| Viral infection | 0 | 1 (0.9) | 0 |

| Malignancies | 1 (0.8) | 2 (1.7) | 1 (0.9) |

| Basal cell carcinoma | 1 (0.8) | 0 | 0 |

| Bowen's disease | 0 | 1 (0.9) | 0 |

| Pulmonary carcinoid tumour | 0 | 1 (0.9) | 0 |

| Invasive ductal breast carcinoma | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.9) |

Includes data up to 56 days after the last dose of study medication.

*All values are number (%).

†Two patients in the MTX arm died during the withdrawal period (uterine neoplasm, renal failure).

MTX, methotrexate.

Discussion

AVERT is the first study to demonstrate that remission can be maintained after rapid withdrawal of all therapy (including csDMARDs, biological DMARDS and corticosteroids) in patients with early RA receiving abatacept plus MTX. Patients treated with abatacept plus MTX achieved significantly higher rates of DAS-defined remission than MTX on-treatment, and a small but significantly higher number of patients achieved sustained, absolute, drug-free, DAS-defined remission following withdrawal of all RA treatment. These results support the hypothesis that early treatment with a T-cell immunomodulator that can impact naive T-cell activation can induce drug-free remission in some patients.21

The results from this study are consistent with those of previous studies of abatacept in early RA, including ADJUST and AGREE.6 22 In AVERT, patients had highly active disease and poor prognostic markers; 95% of patients were anti-CCP-2-positive and rheumatoid factor-positive, a combination associated with enhanced probability of joint damage and disease progression.23 24 Abatacept plus MTX achieved robust efficacy versus MTX, as demonstrated by multiple measures of remission and HAQ-DI, and consistent structural benefits. While joint counts can be subjective and month-by-month variability was evident, the MRI results provide an objective measure of comparative efficacy in support of the clinical endpoints. Additionally, the safety profile observed in this study is consistent with the known safety profile of abatacept,25 with low rates of serious AEs and serious infections, which is relevant for early treatment with biologicals.

AVERT provides a large dataset assessing abatacept monotherapy, which is of interest because many patients cannot tolerate MTX; approximately 30% of patients receive biologicals as monotherapy.26 AVERT showed that a similar number of patients receiving abatacept monotherapy achieved DAS-defined remission versus MTX at month 12. However, the numerically greater benefit on osteitis and synovitis measured by MRI, and the posthoc analysis estimating average efficacy over the 12-month treatment period, are suggestive that abatacept monotherapy may have a greater efficacy benefit compared with MTX. This remains to be confirmed in a prospective, randomised, controlled study.

Following withdrawal of all therapy, a small but significant number of patients sustained drug-free remission following prior treatment with abatacept plus MTX compared with MTX alone. The data indicate that, with abatacept plus MTX treatment, one in four patients was able to maintain drug-free remission through 6 months. This effect is not a consequence of the half-life of abatacept (14.3 days), as assessments were performed up to 6 months after the withdrawal of all treatment (>5 half-lives).27 Moreover, the posthoc analyses of the patients who sustained drug-free remission suggest that patients with shorter symptom duration and lower disease activity at baseline, or longer, sustained, DAS-defined remission prior to treatment withdrawal, were more likely to maintain drug-free remission. These associations were observed specifically in both abatacept arms, suggesting that a biological effect was responsible. Low baseline HAQ-DI, low baseline disease activity, and shorter disease duration are predictors of remission with antitumour necrosis factor agents.28–32 These data, therefore, generate a hypothesis that patients with early RA, with a very short symptom duration and milder disease activity who are possibly presenting within the ‘window of opportunity’, may be able to achieve sustained and complete drug-free remission following treatment with abatacept.

Remission following withdrawal or tapering of RA therapy is an important goal in early RA. The unique study design of AVERT included the rapid withdrawal of all RA treatment, including abatacept, MTX and corticosteroids. Previous studies have examined a variety of treatment withdrawal paradigms with a number of biological agents, but have not assessed the rapid withdrawal of all RA treatment.8–17 Most antitumour necrosis factor withdrawal studies maintained MTX or maintained the biological at half dose. While in many withdrawal studies DAS28 remission was assessed at 6 months after biological withdrawal,8 9 11 12 14 15 in AVERT, assessment of drug-free remission was made by comparing the proportion of patients in DAS-defined remission at both 12 and 18 months. The approach of withdrawing or tapering biological therapy after achievement of remission may reflect a treatment benefit for patients and physicians that could be justifiable given the economic burden of treating patients with early RA. This is especially true if patients who are likely to maintain remission on MTX alone, following biological withdrawal, can be identified prospectively.

The DAS-defined remission cut-off of <2.6, although corresponding to the American Rheumatology Association definition of clinical remission in RA,33 has now been replaced with other measures of remission,34 such as SDAI and Boolean remission, which are also reported here. The cut-off is based on erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and a CRP cut-off has yet to be defined.33 In AVERT, CRP was interchanged with ESR to reduce the variability of the acute phase reactant and aid standardisation across study centres. Data were obtained from patients with early RA with active disease and poor prognostic factors, which limit their generalisability to the overall RA population. The withdrawal analyses were limited by the small number of patients who remained in the withdrawal period. The gradual tapering of RA medication may result in higher remission rates than the rapid withdrawal of all RA therapy applied in AVERT and will be assessed in other trials.

In conclusion, AVERT establishes the benefit of abatacept treatment in combination with MTX in an early RA population, and suggests that, in early RA, drug-free remission may be possible following treatment with abatacept. The novel achievement of sustained remission following withdrawal of all RA therapy in a small but significant number of patients is suggestive of an underlying effect of abatacept's mechanism on autoimmune processes. A withdrawal treatment strategy is a highly desirable goal for patients and physicians in the long-term treatment of RA, and further investigations with abatacept are warranted. Treat-to-remission is now a well-accepted goal of RA therapy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The first draft of the manuscript was prepared by academic and industry authors, with professional medical writing and editorial assistance provided by Stephen Moore, PhD, at Caudex Medical, and funded by Bristol-Myers Squibb. The academic authors vouch for the completeness and accuracy of the data and data analyses, and for the fidelity of the study to the protocol.

Footnotes

Contributors: PE, GRB, VPB, BGC, DEF and TWJH were involved in the conception and design of the study, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data; drafting of manuscript and revising it critically for important intellectual content; final approval of the version to be published. EB and DAW were involved in the conception and design of the study, analysis and interpretation of data; drafting of manuscript and revising it critically for important intellectual content; final approval of the version to be published. CSK was involved in the acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data; drafting of manuscript and revising it critically for important intellectual content; final approval of the version to be published.

Funding: This study was sponsored by Bristol-Myers Squibb.

Competing interests: PE reports receiving consulting fees from AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck, Pfizer, Roche Takeda and UCB; and grant support from AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck, Pfizer, Roche and UCB. GRB reports receiving grant support from Bristol-Myers Squibb, AbbVie, Pfizer, Roche and UCB; consulting fees from Bristol-Myers Squibb, AbbVie, Pfizer, MSD, Medimmune, Roche and UCB; and served on Speakers’ Bureau for Bristol-Myers Squibb, AbbVie, Pfizer, MSD, Roche and UCB. VPB reports receiving grant support from Amgen, Pfizer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Janssen, UCB and Roche/Genentech. BGC reports receiving grant support from Pfizer and Roche-Chugai; and served on Speakers’ Bureau for Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck, Pfizer, Roche-Chugai and UCB. DEF reports receiving grant support from AbbVie, Actelion, Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead, GlaxoSmithKline, National Institutes of Health, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche/Genentech and UCB; consulting fees from AbbVie, Actelion, Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Janssen, Gilead, GlaxoSmithKline, National Institutes of Health, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche/Genentech and UCB; and served on Speakers’ Bureau for AbbVie, Actelion and UCB. EB, CSK and DAW are employees of Bristol-Myers Squibb. TWJH reports receiving consulting fees from Abbott, Biotest, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Crescendo Bioscience, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi-Aventis, Schering-Plough, UCB and Eli Lilly; holding a position of influence on the Meteor Board; grant support from EU & Dutch Arthritis Foundation; served on Speakers’ Bureau for Abbott Laboratories, Biotest, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi-Aventis and Schering-Plough; and travel support from Abbott and Roche.

Ethics approval: The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board or Independent Ethics Committee at each site.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Combe B. Progression in early rheumatoid arthritis. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2009;23:59–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cush JJ. Early rheumatoid arthritis -- is there a window of opportunity? J Rheumatol Suppl 2007;80:1–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singh JA, Furst DE, Bharat A, et al. 2012 update of the 2008 American College of Rheumatology recommendations for the use of disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs and biological agents in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2012;64:625–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Moreland LW, Alten R, Van den Bosch F, et al. Costimulatory blockade in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a pilot, dose-finding, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial evaluating CTLA-4Ig and LEA29Y eighty-five days after the first infusion. Arthritis Rheum 2002;46:1470–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Orencia (250 mg powder for concentrate for solution for infusion) Summary of Product Characteristics 2013. http://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/medicine/19714/SPC/ (accessed 14 Apr 2013).

- 6.Emery P, Durez P, Dougados M, et al. Impact of T-cell costimulation modulation in patients with undifferentiated inflammatory arthritis or very early rheumatoid arthritis: a clinical and imaging study of abatacept (the ADJUST trial). Ann Rheum Dis 2010;69:510–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Orban T, Bundy B, Becker DJ, et al. Co-stimulation modulation with abatacept in patients with recent-onset type 1 diabetes: follow-up one year after cessation of treatment. Diabetes Care 2014;37:1069–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Detert J, Bastian H, Listing J, et al. Induction therapy with adalimumab plus methotrexate for 24 weeks followed by methotrexate monotherapy up to week 48 versus methotrexate therapy alone for DMARD-naive patients with early rheumatoid arthritis: HIT HARD, an investigator-initiated study. Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72:844–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Emery P, Spieler W, Stopinska-Polaszewska M, et al. Assessing maintenance of remission after withdrawal of etanercept plus methotrexate, methotrexate alone, or placebo in early rheumatoid arthritis patients who achieved remission with etanercept and methotrexate: The Prize study. Arthritis Rheum 2013;65(Suppl 10):2689. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huizinga TW, Conaghan PG, Martin-Mola E, et al. Clinical and radiographic outcomes at 2 years and the effect of tocilizumab discontinuation following sustained remission in the second and third year of the ACT-RAY study. Ann Rheum Dis 2014. Published Online First: 28 August 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nam JL, Villeneuve E, Hensor EM, et al. Remission induction comparing infliximab and high-dose intravenous steroid, followed by treat-to-target: a double-blind, randomised, controlled trial in new-onset, treatment-naive, rheumatoid arthritis (the IDEA study). Ann Rheum Dis 2014;73:75–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nishimoto N, Amano K, Hirabayashi Y, et al. Drug free REmission/low disease activity after cessation of tocilizumab (Actemra) Monotherapy (DREAM) study. Mod Rheumatol 2014;24:17–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Quinn MA, Conaghan PG, O'Connor PJ, et al. Very early treatment with infliximab in addition to methotrexate in early, poor-prognosis rheumatoid arthritis reduces magnetic resonance imaging evidence of synovitis and damage, with sustained benefit after infliximab withdrawal: results from a twelve-month randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum 2005;52:27–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smolen JS, Nash P, Durez P, et al. Maintenance, reduction, or withdrawal of etanercept after treatment with etanercept and methotrexate in patients with moderate rheumatoid arthritis (PRESERVE): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2013;381:918–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smolen JS, Emery P, Fleischmann R, et al. Adjustment of therapy in rheumatoid arthritis on the basis of achievement of stable low disease activity with adalimumab plus methotrexate or methotrexate alone: the randomised controlled OPTIMA trial. Lancet 2014;383:321–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van den Broek M, Klarenbeek NB, Dirven L, et al. Discontinuation of infliximab and potential predictors of persistent low disease activity in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis and disease activity score-steered therapy: subanalysis of the BeSt study. Ann Rheum Dis 2011;70:1389–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Villeneuve E, Nam JL, Hensor E, et al. Preliminary results of a multicentre randomised controlled trial of etanercept and methotrexate to induce remission in patients with newly diagnosed inflammatory arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2011;63:S960–1. [Google Scholar]

- 18.ICH Harmonised Tripartite Guideline: Guideline for Good Clinical Practice. J Postgrad Med 2001;47:199–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.[No authors listed]Directive 2001/20/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 4 April 2001 on the approximation of the laws, regulations and administrative provisions of the member states relating to the implementation of good clinical practice in the conduct of clinical trials on medicinal products for human use. Med Etika Bioet 2002;9:12–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Title 21--Food and drugs. Chapter I--Food and Drug Administration Department of Health and Human Services. Subchapter A--General. Part 50 Protection of human subjects. Code of Federal Regulations2013.

- 21.Cutolo M, Nadler S. Advances in CTLA-4-Ig-mediated modulation of inflammatory cell and immune response activation in rheumatoid arthritis. Autoimmun Rev 2013;12:758–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Westhovens R, Robles M, Ximenes AC, et al. Clinical efficacy and safety of abatacept in methotrexate-naive patients with early rheumatoid arthritis and poor prognostic factors. Ann Rheum Dis 2009;68:1870–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goronzy JJ, Matteson EL, Fulbright JW, et al. Prognostic markers of radiographic progression in early rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2004;50:43–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kroot EJ, de Jong BA, van Leeuwen MA, et al. The prognostic value of anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibody in patients with recent-onset rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2000;43:1831–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nash P, Nayiager S, Genovese MC, et al. Immunogenicity, safety, and efficacy of abatacept administered subcutaneously with or without background methotrexate in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: results from a phase III, international, multicenter, parallel-arm, open-label study. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2013;65: 718–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Emery P, Sebba A, Huizinga TW. Biologic and oral disease-modifying antirheumatic drug monotherapy in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2013;72:1897–904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Orencia prescribing information. 2013. http://packageinserts.bms.com/pi/pi_orencia.pdf (accessed 28 Sep 2014).

- 28.Einarsson JT, Geborek P, Saxne T, et al. Sustained remission in anti-TNF treated rheumatoid arthritis patients. Observational data from southern Sweden. Arthritis Rheum 2011;63(Suppl 10):432. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pomirleanu C, Ancuta C, Miu S, et al. A predictive model for remission and low disease activity in patients with established rheumatoid arthritis receiving TNF blockers. Clin Rheumatol 2013;32:665–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Burmester GR, Ferraccioli G, Flipo RM, et al. Clinical remission and/or minimal disease activity in patients receiving adalimumab treatment in a multinational, open-label, twelve-week study. Arthritis Rheum 2008;59:32–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mancarella L, Bobbio-Pallavicini F, Ceccarelli F, et al. Good clinical response, remission, and predictors of remission in rheumatoid arthritis patients treated with tumor necrosis factor-alpha blockers: the GISEA study. J Rheumatol 2007;34:1670–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Furst DE, Pangan AL, Harrold LR, et al. Greater likelihood of remission in rheumatoid arthritis patients treated earlier in the disease course: results from the Consortium of Rheumatology Researchers of North America registry. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2011;63:856–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fransen J, Creemers MC, van Riel PL. Remission in rheumatoid arthritis: agreement of the disease activity score (DAS28) with the ARA preliminary remission criteria. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2004;43:1252–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Felson DT, Smolen JS, Wells G, et al. American College of Rheumatology/European League against Rheumatism provisional definition of remission in rheumatoid arthritis for clinical trials. Ann Rheum Dis 2011;70:404–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.