Abstract

Shear thinning hydrogels are promising materials that exhibit rapid self-healing following the cessation of shear, making them attractive for a variety of applications including injectable biomaterials. In this work, self-assembly is demonstrated as a strategy to introduce a reinforcing network within shear thinning artificially engineered protein gels, enabling a responsive transition from an injectable state at low temperatures with a low yield stress to a stiffened state at physiological temperatures with resistance to shear thinning, higher toughness, and reduced erosion rates and creep compliance. Protein-polymer triblock copolymers capable of the responsive self-assembly of two orthogonal networks have been synthesized by conjugating poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) to the N- and C- termini of a protein midblock decorated with coiled-coil self-associating domains. Midblock association forms a shear-thinning network, while endblock aggregation at elevated temperatures introduces a second, independent physical network into the protein hydrogel. These new, reversible crosslinks introduce extremely long relaxation times and lead to a five-fold increase in the elastic modulus, significantly larger than is expected from transient network theory. Thermoresponsive reinforcement reduces the high temperature creep compliance by over four orders of magnitude, decreases the erosion rate by at least a factor of five, and increases the yield stress by up to a factor of seven. The reinforced hydrogels also exhibit enhanced resistance to plastic deformation and failure in uniaxial compression. Combined with the demonstrated potential of shear thinning artificial protein hydrogels for various uses, including the minimally-invasive implantation of bioactive scaffolds, this reinforcement mechanism broadens the range of applications that can be addressed with shear-thinning physical gels.

Keywords: Hydrogels, Self-Assembly, Stimuli-Responsive Materials, Hybrid Materials, Block Copolymers

1. Introduction

Associative polymers have attracted significant interest for the development of improved rheological modifiers,[1] stimuli-responsive actuators in soft machines,[2] and hydrogels for sustained drug delivery and regenerative medicine.[3] The growing demand for advanced soft materials has given rise to a broad range of physically associating polymer architectures capable of combining a desired chemical functionality with tunable linear and nonlinear mechanical properties. Such physically crosslinked gels are well-suited to help address a variety of materials challenges, such as the delivery of therapeutics and cells in biomaterials that have strict demands on mechanical performance, chemical composition, and biological functionality. For example, in the design of bioactive scaffolds it can be necessary to incorporate specific degradation sites, cell adhesion ligands, and morphogenic regulators for treatment efficacy,[4] while simultaneously providing robust control of mechanical behavior for the desired gel lifetime at the implant site. Physically associating systems, which can exhibit reversible gelation,[5] controlled erosion,[6] and self-healing behavior,[7] have demonstrated the potential to address these complex demands.

One particularly promising application of associative polymers is the development of injectable hydrogels for the minimally-invasive implantation of cells, drugs, and scaffolds.[8, 9] Materials that can easily flow and rapidly set into solid implants after injection can be molded into arbitrary shapes to match a tissue defect and are useful for the retention of homogeneously distributed cellular[10] and molecular[11] cargo at the target site. Shear thinning hydrogels are a class of associative polymers that has demonstrated a number of advantages as injectable biomaterials.[8] These physically-crosslinked gels can be prepared as stable formulations in advance, then shear thin and subsequently recover within seconds after injection. An additional feature of certain shear thinning gels is their cyto-protective behavior during the injection process.[10, 12] This behavior has been attributed to shear banding and plug-flow velocity profiles that limit disruption of the cell membrane during the extensional and shear flows experienced during injection.[13] The mechanical properties of shear thinning associative polymer systems makes them well suited to meet the demanding processing constraints for advanced soft materials.

The use of artificially engineered proteins as injectable associative polymers provides a route for addressing several important challenges in producing biomedically-relevant injectable gels. Biological synthesis of sequence-specific polymers allows for a high level of structural precision,[14] enabling simultaneous control over the hydrogel’s mechanical properties,[15] erosion rate,[16] and biological functionality.[17] As one example, shear thinning injectable gels prepared from telechelic artificial proteins containing coiled-coil associating domains exhibit cyto-protective shear-banding behavior and recover after injection in seconds or less.[12] These proteins act as model associative polymers, where perfectly monodisperse macromolecules interact through the formation of well-defined helical bundles with controlled association number and chain orientation. Through genetic engineering, protein hydrogels can also be easily programmed to incorporate biofunctional signals including cell adhesion ligands[18] and enzymatic degradation sites[19] to provide control over how the gel interacts with the tissue environment at the implant site.

Although promising as highly tunable and bioactive injectable scaffolds, many injectable protein hydrogels and shear-thinning gels generally are limited by their high creep and low toughness. The inability to prevent shear thinning post-injection restricts the use of these materials to applications where the gel will not experience shear or bear significant loads after implantation. To broaden the applicability of these materials, it is necessary to develop strategies for reinforcing these gels while retaining their injectability, rapid recovery, biofunctionality, controlled degradation, and cyto-protective behavior. In particular, a responsive mechanism is required to toughen these gels after the shear thinning behavior is no longer needed.

Significant improvement in the fracture toughness of hydrogels has been achieved through a variety of mechanisms that effectively distribute stress and dissipate energy throughout the gel to prevent or delay crack formation.[20] Hydrated composite soft materials consisting of exfoliated clays[21] or carbon nanotubes[22] have exhibited improved mechanical performance at low to moderate filler weight fractions. Double network gels[20, 23] are a widely-investigated category of materials in which energy is dissipated by sacrificial cleavage of chains in a secondary highly crosslinked network.[24] This mechanism results in materials that can tolerate compressive stresses up to 60 MPa at strains of 95%. The double network paradigm has also been applied to triblock copolymer gels, using ionic crosslinking of the polymer midblock to form the highly crosslinked network.[25] The use of physical interactions in both networks makes energy dissipation reversible, enabling both toughness and fatigue resistance.

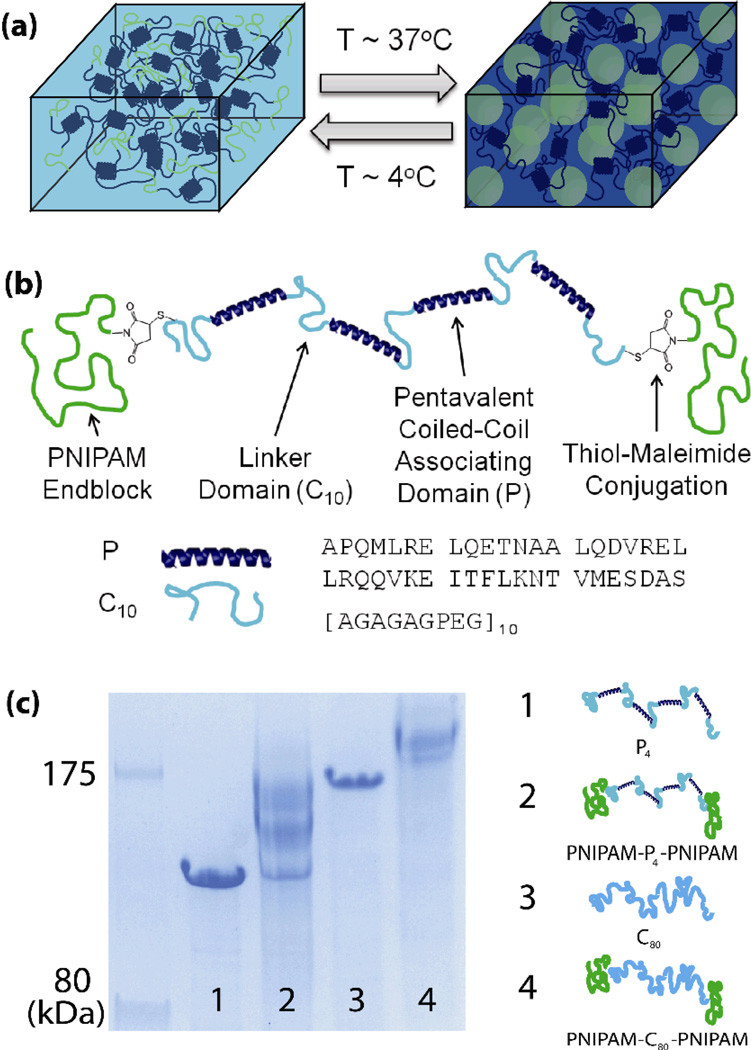

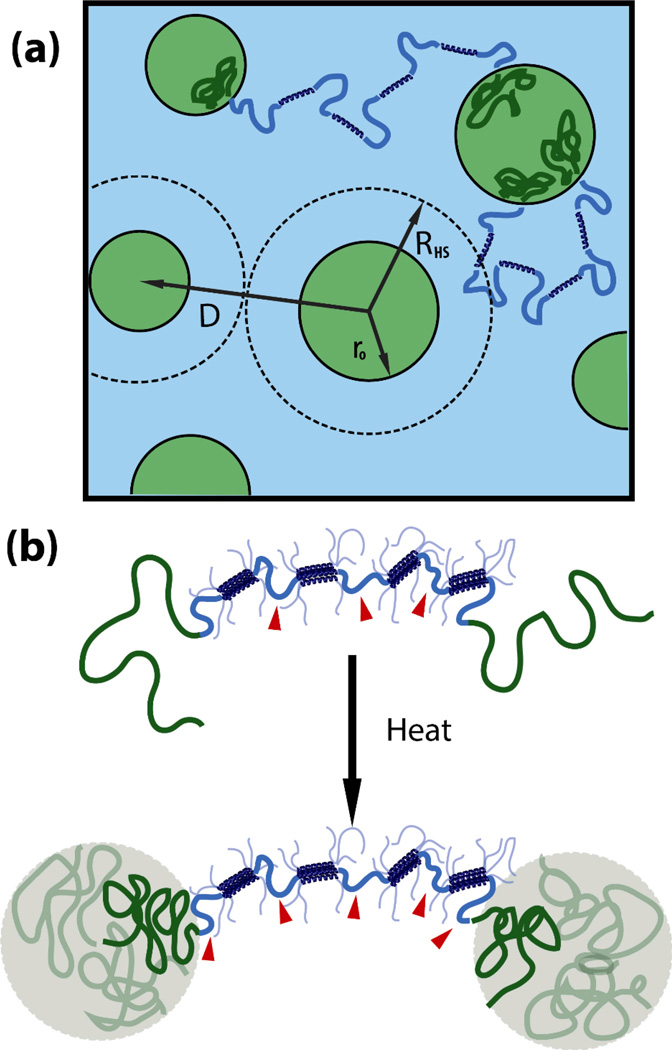

In this work, protein-based hydrogels have been developed that utilize thermoresponsive block copolymer self-assembly to form a second reinforcing network within a shear thinning gel. Using this strategy, the hydrogel responsively transitions from an injectable single network to a dual-network system with improved mechanical performance. Triblock copolymers were synthesized via conjugation of the thermoresponsive polymer poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) (PNIPAM) to the N- and C- termini of an artificially engineered protein with coiled-coil associating domains that forms a shear thinning hydrogel (Figure 1). The hydrophobically associating endblock polymers and the specific interactions of the coiled-coil domains in the midblock act as orthogonal interactions to drive the formation of two independent networks from a single molecule. The structure and linear and nonlinear mechanics of this responsive double physical network are investigated, and endblock self-assembly is shown to lead to a gel-gel transition from a soft, fragile gel at low temperature to a reinforced, tougher gel at physiological temperatures.

Figure 1.

(a) Schematic of responsive self-assembly of PNIPAM triblock copolymer domains within a physically associating protein gel as a responsive mechanism to reinforce shear thinning gels. (b) Molecular design of a hybrid triblock copolymer to achieve the reinforcement behavior. (c) SDS-PAGE showing the purification of bioconjugation of monofunctional PNIPAM to cysteine-flanked midblock proteins. Proteins are shown before (lanes 1 and 3) and after (lanes 2 and 4) the conjugation reaction. MALDI-TOF was used to determine absolute molecular weight of proteins.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Thermoresponsive Self-Assembly

Reinforceable, shear thinning gels from triblock copolymers were prepared by grafting PNIPAM chains near the N and C termini of a gel-forming protein (Figure 1). Inspired by the design of Shull and coworkers,[25] in which a double network hydrogel is formed by adding ionic crosslinks to the midblock of a triblock copolymer gel, this strategy employs orthogonal physical associations that lead to the formation of two networks in the same molecule. However, the use of an endblock polymer with a lower critical solution temperature (LCST) in water and self-associating protein domains that crosslink the midblock leads to a hydrogel that can rapidly respond to environmental or mechanical stimuli. Thermoresponsive self-assembly of the synthetic polymer endblocks forms a larger length scale network, while association of coiled-coil domains within the artificially engineered protein midblock forms a shorter length scale network, as determined by the molecular weight between crosslinks of the polymer chains. Difunctional associative proteins were designed with one cysteine residue at either end of the molecule, enabling site-specific conjugation of PNIPAM blocks via thiolmaleimide coupling. The protein was engineered as a repetitive fusion between homopentameric coiled-coil self-associating domains (P)[16, 27] and solvated, random coil linker domains (C10),[28] forming a molecule with the structure C10(PC10)4, hereafter abbreviated P4. The P domain was chosen because the requirement that an odd number of helices come together to form a bundle promotes interchain associations, leading to gels with a greater number of elastically effective chains.[16] PNIPAM is used because it has a lower critical solution temperature in water with a typical demixing temperature in the physiologically-relevant range at around 32°C.[29, 30] Hybrid block copolymers were prepared from midblocks with and without associating groups (Figure 1c) using proteins with nearly matched molecular weights (Supporting Information, Table S1, Figure S3), denoted PNIPAM-P4-PNIPAM and PNIPAM-C80-PNIPAM, respectively.

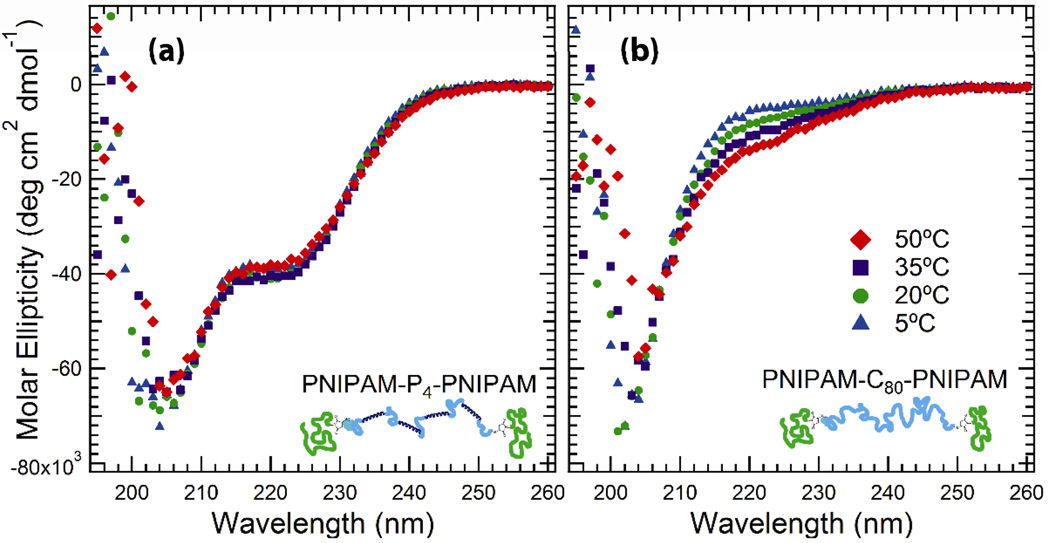

Hydrated PNIPAM-P4-PNIPAM block copolymers form transparent self-supporting gels at both 4°C and when heated to body temperature at a 30% (w/w) concentration, as examined qualitatively through inversion tests. The formation of a viscoelastic solid at low temperatures indicates that the coiled-coil domains in the midblock of PNIPAM-P4-PNIPAM are still associated even in the presence of synthetic polymer endblocks. In contrast, PNIPAM-C80-PNIPAM fails the inversion test and is a viscous liquid at low temperatures, gelling due to endblock association only upon warming. Thermoresponsive self-assembly of the synthetic polymer endblocks does not affect the secondary structure or folding of the associating protein midblocks, as illustrated by circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy (Figure 2). A solution of the unconjugated associative midblock (P4) gives a CD spectrum that is superimposable on that of PNIPAM-P4-PNIPAM, indicating that the helical composition of the midblock is unchanged following conjugation (Supporting Information, Figure S3). As expected, the CD spectrum of PNIPAM-C80-PNIPAM is characteristic of primarily random coil behavior, indicated by the absence of strong features in the 205–230 nm region. No significant change in the molar ellipticity is observed upon heating PNIPAM-P4-PNIPAM between 5°C and 50°C, indicating that the demixing and aggregation of the PNIPAM endblocks does not interfere with the folding of the protein midblock or its ability to associate into a second network independent of the endblock network. These data also confirm that the coiled-coils in the midblock remain folded through 50°C, the maximum temperature examined throughout this study.

Figure 2.

Circular dichroism spectroscopy of (a) PNIPAM-P4-PNIPAM and (b) PNIPAM-C80-PNIPAM at 10 μM in sodium phosphate buffer (100 mm, pH = 7.6).

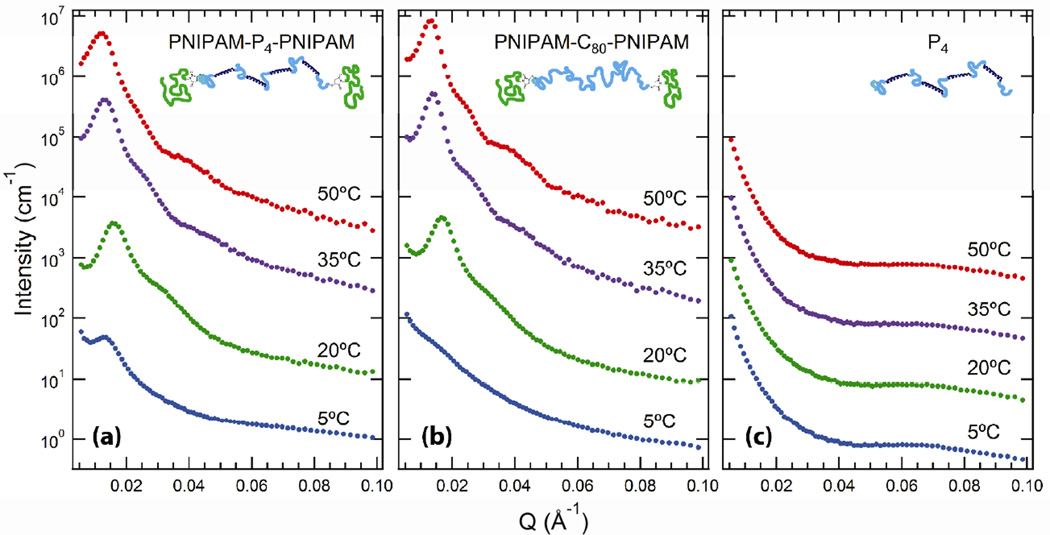

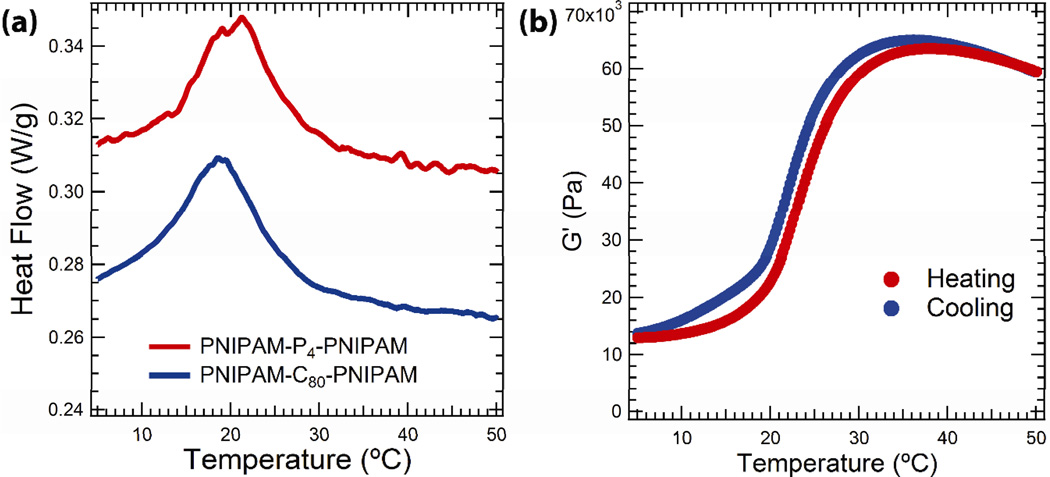

Small-angle neutron scattering (SANS) can be used to study structural transitions from the single-network state where only the protein P domains associate, to the double-network state where both the coiled-coils and the PNIPAM endblocks associate (Figure 3). SANS of 30% PNIPAM-P4-PNIPAM at 5°C reveals a single, low intensity scattering peak. Upon increasing the temperature above 20°C, an intense peak with a high q shoulder is observed indicating the onset of block copolymer self-assembly. The structural transition observed in SANS corresponds to the desolvation of the PNIPAM endgroups, as identified by an endothermic peak in differential scanning calorimetry (DSC; Figure 5a). Further heating up to 35°C results in a shift in the primary scattering peak to lower q, indicating an increase in the characteristic length scale of self-assembly consistent with the increased strength of segregation at elevated temperatures. In addition, sharpening of the high q shoulder with increasing temperature suggests increasing correlations between PNIPAM nanodomains within the gel. Nearly identical structural evolution is observed by SANS in 30% PNIPAM-C80-PNIPAM as compared to the double network PNIPAM-P4-PNIPAM gel (Figure 3b), and SANS of 30% P4 (Figure 3c) reveals no thermoresponsive structural features. These two observations indicate that the responsive structural transition is due to block copolymer microphase separation, and the ultimate nanostructure is not qualitatively altered due to the presence of midblock associations. Depolarized light scattering[31] revealed that PNIPAM-P4-PNIPAM and PNIPAM-C80-PNIPAM gels were isotropic throughout the observed temperature range indicating that self-assembly led to the formation of an isotropic phase of spherical nanodomains, consistent with low endblock weight fractions of approximately 8–10% in both gels (Supporting Information, Figure S4).

Figure 3.

Small angle neutron scattering data for 30% (w/v) (a) PNIPAM-P4-PNIPAM, (b) PNIPAM-C80-PNIPAM, (c) and P4 in deuterated phosphate buffer (100 mm, pH = 7.6). Data collected at different temperatures have been shifted vertically by a factor of 10 for clarity.

Figure 5.

Thermal transitions in hybrid protein block copolymer gels. (a) Differential scanning calorimetry data for hybrid block copolymers in sodium phosphate buffer (100 mm, pH = 7.6) at 30% (w/w) concentration (endotherm up). (b) The plateau modulus of PNIPAM-P4-PNIPAM (30% w/w) plotted as a function of temperature measured by linear oscillatory shear rheology (1% strain, 100 rad s−1, at a heating rate of 1°C min−1).

While the self-assembled structure that forms is nearly identical in thermoresponsive gels with and without midblock associations, the neutron scattering patterns at low temperature show an important difference. The presence of a defined peak in the 5°C trace of PNIPAM-P4-PNIPAM, which is absent in the PNIPAM-C80-PNIPAM gel, suggests that the associative groups in the midblock protein promote the segregation between PNIPAM endblocks and the protein. This observation is consistent with expectations from the theories on the macroscopic phase behavior of associative polymers, which indicate that exchange entropy promotes chain collapse and phase separation.[32] Since microphase separation of PNIPAM results in an effective increase in the concentration of the protein associating domains, endblock segregation should increase the exchange entropy of the associative midblock.The observed weak segregation in PNIPAM-P4-PNIPAM (at 5°C) occurs below the DSC-determined PNIPAM demixing temperature indicating that the endblocks remain hydrated.

Structural evolution in the gels may be quantiatively interrogated by fitting the 1D SANS patterns to a typical model for the structure of triblock copolymer gels. These materials can be modeled as a collection of disordered hard-spheres[33] with a compact core formed from the PNIPAM endblock aggregates and an expansive corona formed by the midblock protein. Neutron scattering contrast originates from the difference between the hydrogenated core/corona and the deuterated solvent, and the collected data can be fit using the analytical expression from the Percus-Yevick model[34] (Supporting Information):

| (1) |

Here, the structure factor, S(q), contains parameters describing the structure of close-packed micelles, with an inter-micellar distance, D = 2 RHS, and a packing fraction, η. The form factor, F(q), contains parameters describing the size of the micellar core radius, ro, and the core size polydispersity parameter, σp. K accounts for the magnitude of the scattering contrast in the system and the additive constant C accounts for the incoherent scattering background.

SANS patterns for the self-assembled gels were fit to Equation 1 (Table 1; full set of fit parameters provided in Supporting Information Table S2). The fits yield values for ro, RHS, and η that are consistent with expectations based on the measured block volume fraction. From simple geometric arguments (Figure 4), the relationship between the fit and measured parameters is given by:

| (2) |

where φPNIPAM is the endblock volume fraction, c is the weight fraction of the hydrogel (0.3), x is the mole fraction of cysteines converted to PNIPAM endblocks, MPNIPAM is 19.2 kDa, and Mprotein is 63.3 kDa and 67.1 kDa for P4 and C80 midblocks, respectively. At 50 °C, when the volume fraction of water in the collapsed PNIPAM domains is expected to be small, the volume fraction calculated from the SANS fit is 0.074 and 0.12 for PNIPAM-P4-PNIPAM and PNIPAM-C80-PNIPAM, respectively, in agreement with the PNIPAM volume fractions of 0.080 and 0.094 calculated from the measured molecular weights and conjugation efficiencies for the protein-polymer conjugates. The packing fraction, η, is within the range expected for tetrahedral and cubic-like packing densities, 0.34 and 0.52, respectively.[35]

Table 1.

Structural parameters for SANS fits to the Percus-Yevick model

|

Temperature [°C] |

RHS [nm][a] |

η[b] |

ro [nm][c] |

σp [nm][d] |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PNIPAM-C80-PNIPAM | 20 | 18.03 ±0.03 | 0.394 ±0.002 | 8.2 ±0.6 | 2.8 ±0.4 |

| 35 | 22.28 ±0.08 | 0.452 ±0.005 | 13.0 ±1.0 | 4.0 ±0.8 | |

| 50 | 22.87 ±0.11 | 0.424 ±0.006 | 15.2 ±0.9 | 4.0 ±0.7 | |

| PNIPAM-P4-PNIPAM | 20 | 18.68 ±0.04 | 0.380 ±0.003 | 7.1 ±0.6 | 2.4 ±0.4 |

| 35 | 22.02 ±0.08 | 0.360 ±0.005 | 12.0 ±0.8 | 3.0 ±0.6 | |

| 50 | 22.73 ±0.10 | 0.327 ±0.005 | 13.8 ±0.8 | 3.3 ±0.6 |

Hard sphere radius (half the intermicellar distance)

Micellar packing fraction

Radius of the condensed PNIPAM core

Polydispersity parameter

Figure 4.

Structural changes due to endblock self-assembly. (a) Schematic of nanostructure above the demixing temperature of the PNIPAM endblocks (green chains), where RHS is the hard sphere radius due to the packing of micelles, ro is the radius of the PNIPAM core, and D is the center-to-center intermicellar distance. (b) The theoretical number of elastically effective chains (indicated by red arrowheads) changes from three to five due to the formation of additional physical crosslinks due to endblock association upon heating.

The size of the nanostructures formed by PNIPAM-P4-PNIPAM and PNIPAM-C80-PNIPAM are very similar, confirming that midblock associations do not significantly perturb the self-assembled nanostructure. Both gels exhibit average domain spacings (D = 2 RHS) of approximately 36–37 nm at 20 °C, which grow to 45–46 nm upon heating to 50 °C. The core radii (ro) almost double over this same temperature range even as the PNIPAM domains continue to exclude water, indicating that the average aggregation number of each domain increases with increasing temperature. The similarity in structure is noteworthy given that in the PNIPAM-P4-PNIPAM gel, reorganization of the midblock coiled-coil associations is required for endblock aggregation and nanostructure growth.

As the temperature is raised from 20 °C to 50 °C, the aggregation number per core increases and the corona thickness decreases, suggesting that midblock chains become compressed in the regions between adjacent, bridged micelles. While increasing temperature leads to the growth of both the hard sphere radius (RHS) and the core radius (ro), the approximate thickness of the corona (Hcorona = RHS – ro) decreases from 11.6 to 8.9 nm and 9.8 to 7.7 nm for PNIPAM-P4-PNIPAM and PNIPAM-C80-PNIPAM, respectively. The root mean square end-to-end distance, , of a single C10 domain is estimated to be between 5.9 and 7.3 nm.[15] Assuming the charges along the midblock are highly screened by the 100 mm phosphate buffer, the C80 midblock is expected to have a root mean square end-to-end distance between 20.1 and 24.9 nm. The corona thicknesses determined from the SANS fitted parameters at 20°C (2 Hcorona) are consistent with these values, suggesting that the initial self-assembled state does not perturb the C80 midblock significantly from its equilibrium chain size in solution. However, at 50°C the corona thickness is 20% smaller, suggesting compression of the midblock chains between adjacent micelles.

2.2. Linear Mechanics

Linear oscillatory shear rheology of 30% PNIPAM-P4-PNIPAM (100 rad s−1, 1% strain, 1°C min−1) demonstrates that the thermoresponsive self-assembly of PNIPAM nanodomains leads to a large, reversible stiffening effect (Figure 5b). The thermoresponsive behavior is reproducible after at least three cycles of heating and cooling. The slight hysteresis observed upon cooling the gel is typically observed in PNIPAM triblock copolymers,[36] and can be attributed to the slower dynamics of PNIPAM remixing upon cooling compared to the demixing upon heating.[29] The onset of stiffening occurs around 20°C, consistent with DSC and SANS, and increases until 35°C. Further heating to 50°C results in a slight drop in the elastic modulus. The temperature dependence of the modulus was found to be independent of heating rate over the range 0.5–2°C min−1, implying that assembly dynamics are not significant over these timescales (Supporting Information, Figure S6).

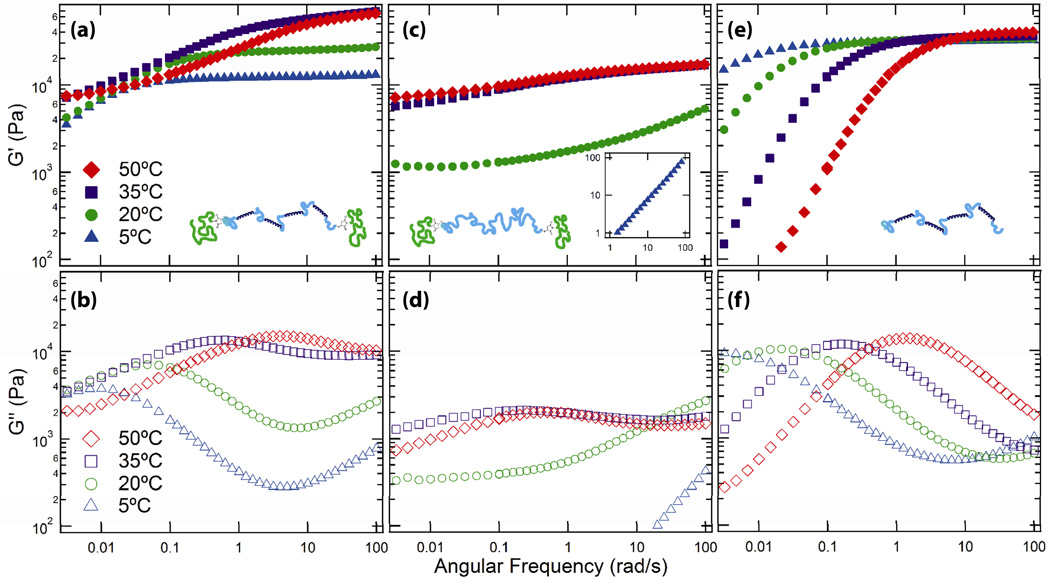

Frequency sweeps as a function of temperature (Figure 6) demonstrate how the protein and the triblock copolymer networks interact to determine the mechanical properties of the gels. At low temperature, the elastic (Figure 6a) and viscous (Figure 6b) moduli of the PNIPAM-P4-PNIPAM gel exhibit features characteristic of a physical hydrogel with a single relaxation time, including a high frequency plateau modulus in G‘ and a low frequency terminal region. With increasing temperature, three effects are observed: an increase in the high frequency elastic modulus, a decrease in the fastest relaxation time at intermediate frequencies, and the onset of non-terminal behavior at low frequency as a second plateau forms. Furthermore, the behavior of the viscous modulus demonstrates a broad increase in dissipation in the frequency range 0.1–100 rad s−1 as the temperature is increased. At high temperatures, no crossover point is observed at low frequency, indicating that the gel retains solid-like behavior for longer experimental times than at lower temperatures.

Figure 6.

Frequency-dependent linear oscillatory shear rheology of the reinforceable gel, PNIPAM-P4-PNIPAM (a) and( b), as well as the two control hydrogels, PNIPAM-C80-PNIPAM (c) and (d), and P4 (e) and (f). Data were collected on 30% (w/w) gels at 1% strain at the indicated temperatures. Storage moduli (G’(ω)) are plotted in panels (a), (c), and (e), while loss moduli (G”(ω)) are plotted in panels (b), (d), and (f). The storage modulus of PNIPAM-C80-PNIPAM at 5°C is off-scale and plotted in the inset in panel (c).

The molecular origin of these changes in mechanical properties is illustrated by the temperature and frequency-dependent response of the two single-network gels. PNIPAM-C80-PNIPAM behaves as a viscous liquid with G′ < G″ (Figure 6c,d) at low temperature and transitions upon heating to a viscoelastic gel with a relaxation time longer than is observable in the experiment, typical for related PNIPAM triblock copolymer gels.[37] Comparison to the rheology of PNIPAM-P4-PNIPAM indicates that endblock self-assembly is responsible for both the low frequency plateau and the increase in high frequency modulus in the triblock materials. In contrast, the P4 single network gel exhibits the frequency response of a physical hydrogel with a single relaxation mechanism at all temperatures (Figure 6e,f). The frequency sweep at low temperature qualitatively matches that of the PNIPAM-P4-PNIPAM gel under similar conditions. The relaxation time decreases by more than two orders of magnitude over a 45°C span in temperature without a change in the plateau modulus. The faster relaxation of the P4 gel at elevated temperatures accounts for the behavior of the PNIPAM-P4-PNIPAM hydrogel at intermediate frequencies: the peak in G“ and first relaxation in G‘ shifts to increasing frequency by a nearly identical factor in the two gels over the same change in temperature. The plateau modulus in the 30% P4 gel (25.1 ± 7.8 kPa) is larger than that of the 30% PNIPAM-P4-PNIPAM gel at 5 °C (13.1 ± 0.5 kPa) because the weight fraction of midblock protein is different between the two. Controlling for the SDS-PAGE estimated endblock conversion, 22% P4 gels have plateau moduli of 14.5 ± 3.8 kPa (Supporting Information, Figure S7).

The frequency-dependent mechanics of the two single-network hydrogels demonstrates that the self-assembled PNIPAM-P4-PNIPAM gels preserve the relaxation behavior of the two independent networks; however, self-assembly of the PNIPAM network in the dual-network system leads to a five-fold increase in the high frequency elastic modulus, from 13.1 ± 0.5 kPa to 65.4 ± 1.9 kPa. This large increase is unexpected based on simple network theories. Assuming that the fraction of elastically effective chains does not change and that hydrogels are prepared from pure triblocks, the maximum predicted increase in modulus due to endblock assembly would be 5/3 (Figure 4); the presence of diblocks leads to a smaller expected thermoresponsive change. Based only on the total number of C10 linker domains that that join two associating functionalities on the same molecule in the unassembled (3) and self-assembled states (4.2, accounting for incomplete endblock conversion), the fraction of elastically effective chains can be calculated in either state using transient network theory for ideal physically-crosslinked polymeric systems in the affine network limit:[38] veff = G′∞/nkT.veff is found to increase from 0.54 ±0.02, consistent with prior studies of similar protein hydrogels,[12, 16] to 1.75 ±0.06.

The large increase in modulus demonstrates that the responsively self-assembled PNIPAM network provides a greater reinforcement effect than can be expected in an ideal crosslinked network. Indeed, the plateau modulus at 35°C for PNIPAM-C80-PNIPAM is 17.5 ±2.9 kPa, which sets the fraction of elastically effective chains at 2.24 ±0.38, indicating that the PNIPAM network itself cannot be adequately described by transient network theory. For concentrated solutions of micelle-forming block copolymers, veff can be larger than unity when the modulus of the resulting gel is not simply related to the number of bridging chains but has contributions from excluded volume interactions between neighboring, close-packed micelles.[39, 40] Comparison of PNIPAM-C80-PNIPAM and PNIPAM-P4-PNIPAM gels indicates that the formation of a micelle network cannot alone account for the increase in plateau modulus to 65.4 kPa; crosslinking of the micelle corona due to protein-protein associations in the midblock also makes significant contributions to the elastic modulus. Theory suggests that entanglements in the micelle corona provide additional contributions to the shear modulus of micellar gels proportional to the number density of these physical crosslinks.[40] A comparison of the plateau moduli for PNIPAM-C80-PNIPAM and PNIPAM-P4-PNIPAM at 35°C indicates that roughly a four-fold increase in modulus can be attributed to the presence of midblock associations (neglecting differences in endblock conversion, which would lower the plateau modulus of PNIPAM-C80-PNIPAM and increase this multiplicative factor). This result suggests that nearly all of the midblock associations are contributing to the elastic response of the PNIPAM-P4-PNIPAM gel above the desolvation temperature, whereas only approximately half do so at 5°C based on the calculation of veff, previously.

2.3. Mechanical Reinforcement and Suppression of Erosion

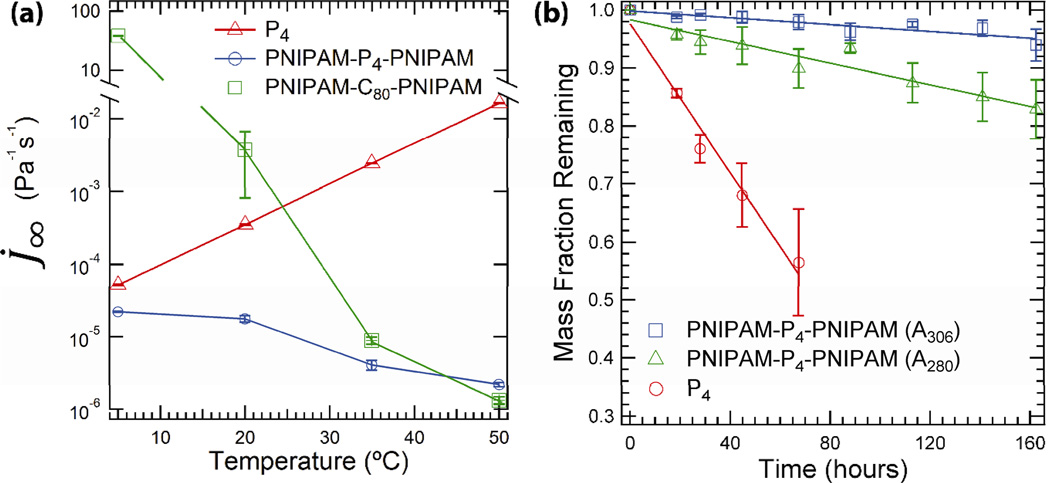

The temperature-dependent creep compliance of PNIPAM-P4-PNIPAM, compared with the unreinforced P4 gel, demonstrates the ability of endblock associations to minimize the rate of deformation under constant applied stress (Figure 7a), enabling gel shape to be maintained under sustained loading. The steady shear rate of compliance (J̇∞) increases exponentially with temperature for P4, which is expected since relaxation in similar leucine zipper hydrogels occurs more rapidly when the strand exchange kinetics are increased.[41] However,J̇∞ for PNIPAM-P4-PNIPAM decreases by an order of magnitude over the same temperature range, having nearly the same value as the PNIPAM-C80-PNIPAM gel by 50°C. The decrease in the rate of compliance originates from the slow mechanisms of endblock pull-out[42] and micelle rearrangement,[40] which are immeasurable by linear oscillatory shear rheology. The longest stress relaxation time (τr) in these materials can be computed from the irrecoverable compliance following creep recovery, Jo, divided by the steady state compliance.[41] At 50°C, τr is 2300 ±300 seconds for PNIPAM-C80-PNIPAM and 3800 ±300 seconds for PNIPAM-P4-PNIPAM, compared with only 18 ±12 seconds for P4. These calculations indicate that the associative midblocks increase the longest stress relaxation time of the block copolymer gels.

Figure 7.

(a) Steady state rate of compliance (J̇∞ = ηo−1) of 30% (w/w) gels plotted as a function of temperature. Lines connecting data points are added to guide the eye. (b) Erosion of 30% (w/w) reinforced and unreinforced hydrogels at 35°C (100 mm phosphate, pH = 7.6). For the reinforced gels, the erosion of both bioconjugate (blue squares) and free protein (green triangles) were monitored over time. Erosion rates determined from linear fits to the data are indicated in the plot.

In addition to creep resistance, engineering the erosion rate of injectable hydrogels is another important design parameter in the development of advanced gels. The effect of introducing additional slowly relaxing physical crosslinks is to significantly slow the erosion of hydrogels, making them more stable in open systems found in physiological environments. The free erosion of reinforced and unreinforced hydrogels at 35°C was measured in excess buffer by monitoring the protein and bioconjugate concentrations spectrophotometrically over the course of one week (Figure 7b). After four days, a P4 gel can no longer be observed at the bottom of the container. The linear mass decay profile of protein, as determined from the A280 signal over time, indicates that both P4 and PNIPAM-P4-PNIPAM gels degrade by surface rather than bulk erosion,[16] but the erosion rate is reduced by greater than a factor of five, from −6.40 ×10−3 hr−1 in the 30% P4 gels to −9.34 ×10−4 hr−1 in the reinforced hydrogels (Figure 7b, red circles and green triangles, respectively). However, the protein released by the reinforced gel does not have the spectral profile of the conjugate polymers, which has a strong absorbance at 306 nm due to the trithiocarbonate group in the PNIPAM endblocks. Monitoring the the gel’s mass loss from the increase in A306 suggests that reinforcement by endblock self-assembly leads to a reduced erosion rate that is lower by more than one order of magnitude (Figure 7b, blue squares). The discrepancy between these two measures indicates that unconjugated protein is being released from the PNIPAM-P4-PNIPAM gel, likely due to the slow hydrolysis of the ester bond that links the thermoresponsive polymer to the associative protein. Tuning the hydrolysis rate of this junction point through changes in the crosslinking chemistry serves as a potential method for tuning the degradation of and release from associative protein hydrogels.

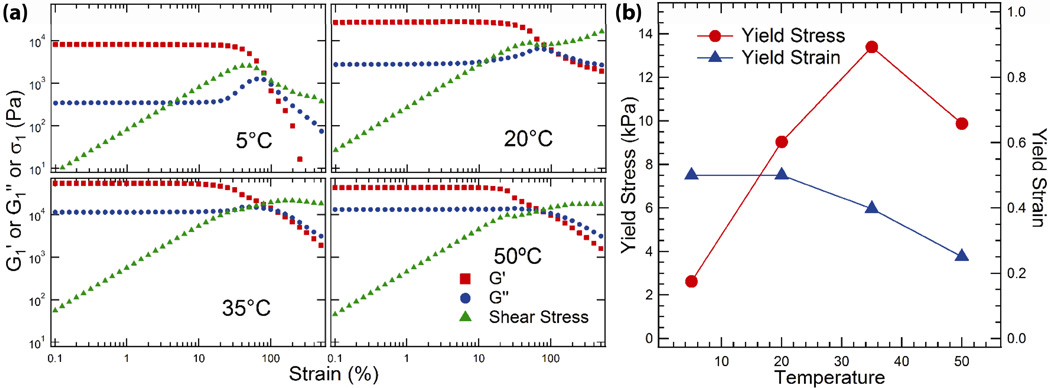

PNIPAM nanodomain self-assembly also has a large impact on the yielding behavior of these materials, as illustrated by strain sweeps in oscillatory shear (at 10 rad s−1) performed into the nonlinear regime (Figure 8a). The nonlinear behavior is significantly different after endblock self-assembly is triggered: the first harmonic G1‘ and G1“ decrease more slowly with increasing strain, and the first harmonic component of the shear stress (σ1) increases slightly instead of decreasing significantly after the yield point. The yield stress and strain were determined from the point at which the shear stress deviated from linearity. A plot of these parameters as a function of temperature (Figure 8b) shows that the yield stress increases seven-fold with increasing temperature and peaks at 35°C, illustrating the ability of endblock self-assembly to trigger a transition from an easily yielding single network to a reinforced double network structure. Lissajous analysis reveals a flattening of the stress-strain curves at all temperatures into the nonlinear regime, confirming that the apparent shear thinning of the gels is due to a yielding mechanism under all conditions (Supporting Information, Figure S8).

Figure 8.

(a) Strain sweeps on 30% (w/w) PNIPAM-P4-PNIPAM in oscillatory shear (10 rad s−1) showing nonlinear dependence of the first harmonic component of the stress (σ1 ≡ |σ*1|), G1’, and G1”. (b) Yield stress and yield strain as a function of temperature.

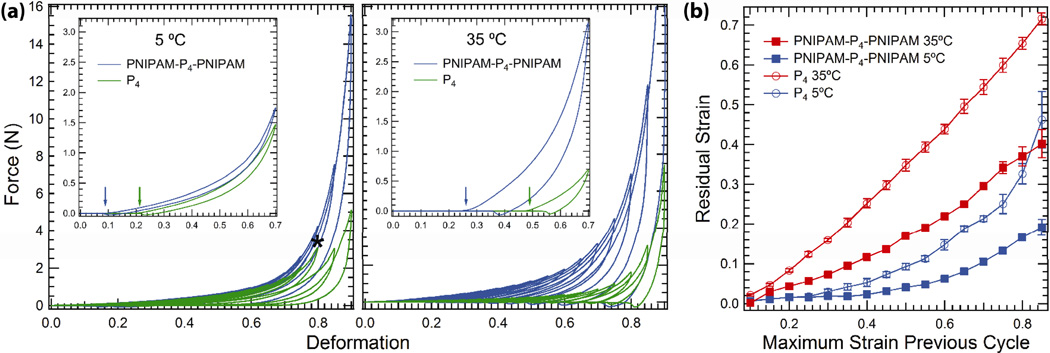

The responsively self-assembled reinforcing domains were also seen to increase gel toughness in uniaxial compression to high deformation, leading to gels with increased stiffness, greater energy dissipation, and improved resistance to plastic deformation at elevated temperatures. Gel samples were subjected to cyclic loading/unloading at 5°C and 35°C to increasing strain at 0.5 mm s−1 (an initial strain rate of approximately 0.13–0.16 s−1) over the range of 10–90% with no wait time between cycles (Figure 9). The compressive moduli, determined from neo-Hookean fits to the data,were found to be 11.8 ±0.9 and 10.2 ±0.7 kPa for the PNIPAM-P4-PNIPAM and P4 gels at 5°C, respectively.[37] The modulus of PNIPAM-P4-PNIPAM increases to 24.8 ±0.5 kPa at 35°C, while P4 softens slightly to 9.1 ±1.0 kPa at the same temperature. At 35°C both gels exhibit increased energy dissipation, as evidenced by the increase in hysteresis between the loading and unloading curves (Figure 9a, insets). In these cyclic compression experiments, fracture could be identified as a sudden increase in hysteresis between loading/unloading. At 5°C, the unreinforced P4 gels fractured by 80% deformation; at 35°C no fracture was observed throughout compression to 90% deformation, but the P4 gels showed significant plastic deformation throughout the test, as indicated by measurements of the change in sample height after each cycle (Figure 9b). At 35°C, P4 gels were flattened significantly by the conclusion of the test, exhibiting very little elastic recovery after each cycle. However, the reinforced PNIPAM-P4-PNIPAM gels demonstrate the ability to resist both fracture and the accumulation of plastic deformation during the cyclic compression test: no fracture is observed throughout compression to 90% deformation and the residual deformation throughout the test is approximately half that of the unreinforced gels. The PNIPAM-P4-PNIPAM gels even continued to slowly recover after compression 90% deformation. Upon waiting three minutes after the final compression cycle, the reinforced gels were found to recover such that the residual deformation was less than 0.3 strain units, indicating that the cyclic compression experiment overestimates the equilibrium residual plastic deformation. In addition to exhibiting improved elastic recovery, the higher modulus and delayed fracture point of the reinforced PNIPAM-P4-PNIPAM hydrogels confirm that endblock self-assembly leads to gels with greater toughness in compression.

Figure 9.

Cyclic compression testing on 30% (w/w) hydrogels at 5°C and 35°C. (a) Characteristic load-deformation curves for the reinforced and unreinforced gels from 10–90% deformation in steps of 5%. Asterisk identifies cycle (green) during which failure occurs in P4 at 5°C. Insets show single loading/unloading step to 70% deformation for each sample. Arrows indicate the re-initiation of contact during the cycle. (b) Plastic deformation of samples was monitored throughout the cyclic procedure by tracking the distance to surface contact.

3. Conclusions

The responsive reinforcement of a shear-thinning protein hydrogel was achieved through the use of block copolymer self-assembly within the associating protein gel to form two orthogonal networks in a single polymeric material. Hybrid protein-polymer block copolymers were synthesized using a grafting-to approach, incorporating specific coiled-coil associations in the midblock protein and hydrophobically aggregating PNIPAM endblock polymers. Circular dichroism and small-angle neutron scattering show that the individual components of this dual-network system were independently responsive, and that structure formation in each network was independent. Triggered microphase separation led to the formation of well-defined spherical nanostructures in the telechelic block copolymer hydrogels without disrupting the secondary structure of the midblock protein domains.

Endblock self-assembly resulted in a thermoresponsive transition from a shear-thinning gel to a reinforced gel, but the impact of this reinforcement mechanism was greater than simply the creation of a more highly crosslinked gel. The gels could be stiffened by up to five-fold, greater than could be expected from transient network theory. This nonlinear increase suggests that both the formation of a percolating network of micelles with PNIPAM cores and an increase in the number of midblock associations contribute to the high temperature modulus. The introduction of physical crosslinks and close-packed micelles with substantially longer relaxation times also led to improved resistance to creep and erosion, counteracting the rapid exchange of midblock associations that occurs at elevated temperatures. Nonlinear rheology demonstrates that the gels will shear thin at low temperatures, and reinforcement can lead to up to a seven-fold increase in the material’s yield stress. Reinforced gels were found to be tougher in compression, having higher moduli and withstanding deformation to higher strains without fracture and with significantly less permanent deformation.

Hydrogels that are responsively tough yet injectable have a number of important applications as high performance load-bearing soft materials. In the minimally-invasive delivery of therapeutics, cells, or bioactive scaffolds in particular, the use of protein-based shear thinning materials provides one method to conveniently biofunctionalize the implant for precise control over its interaction with the target tissue environment. The mechanism for responsive nanostructure formation and mechanical reinforcement explored here takes a step toward achieving these complex goals.

4. Experimental

Polymer Synthesis and Purification

Low polydispersity, monofunctional PNIPAM was synthesized by reversible addition-fragmentation chain transfer (RAFT) polymerization using a chain transfer agent coupled to a furan-protected maleimide, as described previously [43]. Briefly, N-isopropylacrylamide (sublimed), azobisisobutyronitrile (AIBN, recrystallized from methanol), and the chain transfer agent (CTA) [44] were combined in acetonitrile in a 400:0.2:1 ratio. The monomer concentration was fixed at 2 M, and the reaction mixture was degassed by three cycles of freeze-pump-thaw. Polymerization proceeded at 55°C for approximately three hours. The reaction was quenched by cooling rapidly to room temperature and opening the vessel to air. The solvent was removed by rotary evaporation, and the remaining solids dissolved in cold, distilled water and filtered. Polymer was collected following two rounds of thermal precipitation, and dried completely under vacuum. Endgroup deprotection was performed at 120°C under vacuum for 2 hours. Absolute molecular weights were determined using an Agilent 1260 GPC system with three DMF ResiPore columns (resolution up to 400 kDa), a Wyatt Mini-DAWN TREOS 3-angle static light scattering detector, and a Wyatt Optilab T-rEX refractive index detector. The dn/dc of the synthesized polymers was measured to be 0.0761 (±0.0007) mL g−1 at 25 °C (λ = 658.0 nm). The two polymers used in this study had Mn = 19.2 kDa and 20.2 kDa, and PDI’s of 1.08 and 1.04, respectively.

Protein Synthesis

Variants of gel-forming proteins were engineered by alternating the genes of a random coil linker sequence (C10) and a pentameric self-associating coiled-coil sequence (P), based on plasmids prepared previously [12, 16]. The genes were cloned with NheI and SpeI recognition sequences at the 5’ and 3’ ends respectively. Restriction digests with the appropriate enzymes liberate complementary overhangs at both ends, and subsequent ligation yields a single SpeI site at the 3’ end of the insert when the genes have been cloned in the proper orientation. This strategy was used to sequentially assemble C10(PC10)4 and C80. In a final step, the genes were excised and inserted into the pQE9 expression vector (Qiagen), where the multiple cloning site was mutated to include an SpeI recognition sequence flanked by cysteine codons.

The genes were transformed into Escherichia coli (E. coli) strain SG13009 with the pREP4 repressor plasmid. Overnight cultures (5 mL) were used to inoculate expressions in Terrific Broth (1 L). Cells were grown at 37°C to an optical density of 0.9–1.1 and induced with IPTG (1 mm, final concentration). Cells were harvested by centrifugation 6 hours post-induction, and the pellets were stored at −80°C overnight. For each liter of expression, the cells were resuspended on ice in lysis buffer (50 mL; 10 mm Tris, 1 mm EDTA, 100 mm NaCl, pH = 7.5, 5 mm MgCl2). Lysozyme (100 mg) was added, then after 1 hour the suspension was sonicated. Cell debris was removed by centrifugation, and DNAse I and RNAse A (2 mg each) were added to the clarified supernatant and incubated for 2–3 hours at 37°C. Urea (8 m), phosphate (100 mm), and β-mercaptoethanol (BME, 20 mm) were added to the supernatant to denature and reduce the lysate. Proteins were purified from the crude lysate by ammonium sulfate precipitation. For cysteine-flanked C10(PC10)4 (cys-P4), (NH4)2SO4 was added (10 g per 50 mL buffer), incubated for at least 2 hours, then centrifuged at 37°C. To the supernatant, additional (NH4)2SO4 (2.5 g) was dissolved, the solution incubated, and then centrifuged at 37°C once more. For cysteine-flanked C80 (cys-C80), (NH4)2SO4 (14 g per 50 mL) was added in the first precipitation, followed by additional (NH4)2SO4 (3.5 g) in the second cycle to precipitate the desired protein. The protein pellet was resuspended in urea (8 m) with BME (20 mm), dialyzed against water, then lyophilized. Complete digestion of nucleic acids was determined by UV-Vis and protein purity assessed by SDS-PAGE and MALDI-TOF. Yields were typically in excess of 175 mg per liter expression. C10(PC10)4 (P4) was purified selectively from denatured cell lysate by metal affinity chromatography using Ni-NTA resin (Qiagen). Yields were typically 60–80 mg per liter expression.

Bioconjugation and Purification

Thiol-maleimide conjugations were performed in sodium phosphate buffer (100 mm, pH = 8.0), supplemented with EDTA (1 mm). Tris(2-carboxyethylphosphine) (TCEP) was dissolved in the buffer immediately prior to use, at a 10-fold molar excess to the protein. Lyophilized protein (7 mg mL−1) and deprotected PNIPAM (10-fold excess per cysteine) were added to the buffer, and the reaction was allowed to proceed overnight at 4°C with constant stirring. Conjugates were purified from the excess polymer by anion exchange chromatography under denaturing conditions using QAE-Sephadex A-50 resin (GE Healthcare). First, the conjugation reaction mixture was dialyzed 3–4 times against water to remove the phosphate, then urea (6 m) and Tris (20 mm) were added and the pH adjusted to 6.4. Conjugates were bound to the Sephadex column under continuous flow and the concentration of PNIPAM in the flowthrough was monitored spectrophotometrically, since the trithiocarbonate group on the RAFT agent has a strong absorbance in the range 300–310 nm. The resin was washed with excess binding buffer (6 m urea, 20 mm Tris, pH = 6.4) until the A306 signal was indistinguishable from the baseline. Conjugates were eluted using binding buffer supplemented with NaCl (500 mm). The elutions were dialyzed against water, lyophilized, and stored at −20°C. From the SDS-PAGE densitometry-estimated mole fractions of each species (Supporting Information), endblock conjugation was determined to be 61% (±4%) and 83% (±7%) in PNIPAM-P4-PNIPAM and PNIPAM-C80-PNIPAM, respectively. The difference in conjugation efficiency was attributed to the reduced accessibility of cysteine residues in the associating protein (cys-P4) under the reaction conditions used.

Circular Dichroism

Proteins or conjugates were weighed out from lyophilized powders and prepared as solutions (10 μM) in sodium phosphate buffer (100 mm, pH = 7.6). Samples were loaded into a quartz cuvette with a 1 mm path length. Samples were scanned using an Aviv Model 202 Circular Dichroism Spectrometer with a Peltier temperature controller. Scans were collected with 1 nm resolution and an averaging time of 5 seconds.

Small Angle Neutron Scattering

SANS experiments were performed at the Lujan Center at the Los Alamos Neutron Science Center on the Low Q Diffractometer. Deuterated phosphate buffers were prepared with protonated monosodium phosphate monohydrate (0.22% w/v) and protonated disodium phosphate heptahydrate (2.26% w/v) in D2O, targeting 100 mm phosphate buffer at pH = 7.6. Hydrogels were prepared by combining protonated proteins and block copolymers with deuterated buffers in a 30:70 ratio (mass:volume). Samples were allowed to equilibrate at 4°C for 24–48 hours. Homogeneous gels were sealed between two quartz plates separated by a Teflon spacer approximately 0.5 mm thick. Samples were equilibrated for at least 30 minutes at each temperature. Two-dimensional scattering patterns were collected until at least 500,000 events above background. 1D reductions were executed [45] and the data were fit accounting for smearing due the finite collimation and pixel size.

Rheology

Oscillatory shear rheology and shear creep compliance measurements were performed on an Anton Paar MCR-301 stress controlled rheometer in Direct Strain Oscillation mode for pseudo-strain control. The rheometer was outfitted with a Peltier heating system with an environmental enclosure for uniform temperature control. Protein or block copolymer samples (30% w/w) were hydrated in sodium phosphate buffer (100 mm, pH = 7.6). Samples were allowed to swell completely at 4°C for 24–48 hours with periodic mixing and centrifugation until homogenized. Gels were loaded into a sandblasted cone-and-plate geometry using a 25 mm, 1° cone. A mineral oil barrier was used to prevent sample dehydration. Creep measurements were performed for 20 minutes three times per temperature at loads in the linear range, each followed by a recovery step under zero load.

Erosion

Approximately 1.25 mm thick gels were prepared in cylindrical wells 6.4 mm in diameter and 8.5 mm tall by loading the gel (approximately 40 μL, 30% w/w) and making the gel surface flat by centrifugation. Gels were equilibrated briefly at 35 °C and then prewarmed sodium phosphate buffer (250 μL, 100 mm, pH = 7.6) was added to each well. The concentration of material in the supernatant was monitored spectrophotmetrically by continuous sampling over the course of one week at constant temperature in the absence of mechanical disruption. Experiments were performed in quintuplicate.

Uniaxial Compression

Compression experiments were performed using a Texture Technologies Corp. Texture Analyzer with a 5 N load cell and a temperature controlled environmental chamber with membrane humidification. Aluminum platens were covered with teflon sheets, and a layer of mineral oil was used for additional lubrication. Hydrated gels (30% w/w) in sodium phosphate buffer (100 mm, pH = 7.6) were formed into cylindrical plugs in teflon molds approximately 3 mm in diameter and 3–4 mm tall to yield optically clear gels with no macroscopically visible surface artifacts. Gels were placed in the chamber and equilibrated at the specified temperature for approximately 3 minutes prior to the start of compression. Contact was initiated at 0.01 N and the gels were precycled 5 times by ±1% strain. Cyclic loading/unloading was performed at a constant strain rate (0.5 mm s−1) in 5% strain increments from 10–90%. The platen returned to the initial sample height (ho) at the end of each cycle. Experiments were performed in triplicate.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the U.S. Army Research Office under contract W911NF-07-D-0004. SANS measurements were performed at the Lujan Center at the Los Alamos Neutron Science Center (LANSCE). The authors would like to acknowledge Drs. Rex Hjelm and Monica Hartl for assistance with the SANS experiments. Access to a CD spectrophotometer was provided by the Biophysical Instrumentation Facility for the Study of Complex Macromolecular Systems (NSF-0070319 and NIH GM68762), and NMR and MALDI were performed at the MIT Department of Chemistry Instrumentation Facility (DCIF). The authors are grateful to Prof. Gareth McKinley, Ahmed Helal and Dr. Simona Socrate for helpful discussions for compression experiments, and Chris Lam and Mark Belanger for machine shop assistance. MJG is supported by an NIH Interdepartmental Biotechnology Training Program (2-T32-GM08334) and JC is supported by a Summer Undergraduate Research Fellowship (SURF) from Caltech Student-Faculty Programs. Supporting Information is available online from Wiley InterScience or from the author.

Contributor Information

Matthew J. Glassman, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 77 Massachusetts Ave, Room 66-556, Cambridge, MA 02139 (USA)

Jacqueline Chan, 1200 E. California Blvd, Pasadena, CA 91125 (USA).

Bradley D. Olsen, Email: bdolsen@mit.edu, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 77 Massachusetts Ave, Room 66-556m Cambridge, MA 02139 (USA).

References

- 1.a) Winnik MA, Yekta A. Current Opinion in Colloid & Interface Science. 1997;2:424. [Google Scholar]; b) Tripathi A, Tam KC, McKinley GH. Macromolecules. 2006;39:1981. [Google Scholar]

- 2.a) Calvert P. Advanced Materials. 2009;21:743. [Google Scholar]; b) Shin MK, Spinks GM, Shin SR, Kim SI, Kim SJ. Advanced Materials. 2009;21:1712. [Google Scholar]; c) Wu ZL, Gong JP. NPG Asia Mater. 2011;3:57. [Google Scholar]

- 3.a) Hoffman AS. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews. 2002;54:3. doi: 10.1016/s0169-409x(01)00239-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Peppas NA, Huang Y, Torres-Lugo M, Ward JH, Zhang J. Annual Review of Biomedical Engineering. 2000;2:9. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bioeng.2.1.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Yan C, Pochan DJ. Chemical Society Reviews. 2010;39:3528. doi: 10.1039/b919449p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.a) Lutolf MP, Weber FE, Schmoekel HG, Schense JC, Kohler T, Muller R, Hubbell JA. Nature biotechnology. 2003;21:513. doi: 10.1038/nbt818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Lutolf MP, Lauer-Fields JL, Schmoekel HG, Metters AT, Weber FE, Fields GB, Hubbell JA. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2003;100:5413. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0737381100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Lutolf MP, Hubbell JA. Nat Biotech. 2005;23:47. doi: 10.1038/nbt1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Petka WA, Harden JL, McGrath KP, Wirtz D, Tirrell DA. Science. 1998;281:389. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5375.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tae G, Kornfield JA, Hubbell JA, Johannsmann D, Hogen-Esch TE. Macromolecules. 2001;34:6409. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yan C, Altunbas A, Yucel T, Nagarkar RP, Schneider JP, Pochan DJ. Soft Matter. 2010;6:5143. doi: 10.1039/C0SM00642D. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Guvendiren M, Lu HD, Burdick JA. Soft Matter. 2012;8:260. [Google Scholar]

- 9.a) Kretlow JD, Klouda L, Mikos AG. Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews. 2007;59:263. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2007.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Yu L, Ding J. Chemical Society Reviews. 2008;37:1473. doi: 10.1039/b713009k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haines-Butterick L, Rajagopal K, Branco M, Salick D, Rughani R, Pilarz M, Lamm MS, Pochan DJ, Schneider JP. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2007;104:7791. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701980104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jeong B, Bae YH, Lee DS, Kim SW. Nature. 1997;388:860. doi: 10.1038/42218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Olsen BD, Kornfield JA, Tirrell DA. Macromolecules. 2010;43:9094. doi: 10.1021/ma101434a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.a) Aguado BA, Mulyasasmita W, Su J, Lampe KJ, Heilshorn SC. Tissue Engineering Part A. 2012;18(7-8):806. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2011.0391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Yan C, Mackay ME, Czymmek K, Nagarkar RP, Schneider JP, Pochan DJ. Langmuir. 2012 doi: 10.1021/la2041746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.a) Xu C, Breedveld V, Kopeček J. Biomacromolecules. 2005;6:1739. doi: 10.1021/bm050017f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Xu C, Kopeček J. Pharmaceutical Research. 2008;25:674. doi: 10.1007/s11095-007-9343-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shen W, Kornfield JA, Tirrell DA. Soft Matter. 2007;3:99. doi: 10.1039/b610986a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shen W, Zhang K, Kornfield JA, Tirrell DA. Nat Mater. 2006;5:153. doi: 10.1038/nmat1573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liu JC, Heilshorn SC, Tirrell DA. Biomacromolecules. 2004;5:497. doi: 10.1021/bm034340z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wong Po Foo CTS, Lee JS, Mulyasasmita W, Parisi-Amon A, Heilshorn SC. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2009;106:22067. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904851106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Straley KS, Heilshorn SC. Advanced Materials. 2009;21:4148. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gong JP. Soft Matter. 2010;6:2583. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu Y, Zhu M, Liu X, Zhang W, Sun B, Chen Y, Adler H-JP. Polymer. 2006;47:1. [Google Scholar]

- 22.a) Tong X, Zheng J, Lu Y, Zhang Z, Cheng H. Materials Letters. 2007;61:1704. [Google Scholar]; b) Schaefer DW, Justice RS. Macromolecules. 2007;40:8501. [Google Scholar]

- 23.a) Gong J, Katsuyama Y, Kurokawa T, Osada Y. Advanced Materials. 2003;15:1155. [Google Scholar]; b) Shin H, Olsen BD, Khademhosseini A. Biomaterials. 2012;33:3143. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2011.12.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Webber RE, Creton C, Brown HR, Gong JP. Macromolecules. 2007;40:2919. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Henderson KJ, Zhou TC, Otim KJ, Shull KR. Macromolecules. 2010;43:6193. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shen W, Zhang K, Kornfield JA, Tirrell DA. Nat Mater. 2006;5:153. doi: 10.1038/nmat1573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Malashkevich VN, Kammerer RA, Efimov VP, Schulthess T, Engel J. Science. 1996;274:761. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5288.761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McGrath KP, Fournier MJ, Mason TL, Tirrell DA. Journal of the American Chemical Society. 1992;114:727. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Van Durme K, Van Assche G, Van Mele B. Macromolecules. 2004;37:9596. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xia Y, Burke NAD, Stöver HDH. Macromolecules. 2006;39:2275. [Google Scholar]

- 31.a) Balsara NP, Perahia D, Safinya CR, Tirrell M, Lodge TP. Macromolecules. 1992;25:3896. [Google Scholar]; b) Wang H, Newstein MC, Chang MY, Balsara NP, Garetz BA. Macromolecules. 2000;33:3719. [Google Scholar]

- 32.a) Cates ME, Witten TA. Macromolecules. 1986;19:732. [Google Scholar]; b) Semenov AN, Rubinstein M. Macromolecules. 1998;31:1373. [Google Scholar]; c) Dobrynin AV. Macromolecules. 2004;37:3881. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Seitz ME, Burghardt WR, Faber KT, Shull KR. Macromolecules. 2007;40:1218. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kinning DJ, Thomas EL. Macromolecules. 1984;17:1712. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hilbert D, Cohn-Vossen S. Geometry and the Imagination. New York: Chelsea Publishing Co; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li C, Tang Y, Armes SP, Morris CJ, Rose SF, Lloyd AW, Lewis AL. Biomacromolecules. 2005;6:994. doi: 10.1021/bm049331k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sanabria-DeLong N, Crosby AJ, Tew GN. Biomacromolecules. 2008;9:2784. doi: 10.1021/bm800557r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.a) Green MS, Tobolsky AV. The Journal of Chemical Physics. 1946;14:80. [Google Scholar]; b) Annable T, Buscall R, Ettelaie R, Whittlestone D. Journal of Rheology. 1993;37:695. [Google Scholar]

- 39.a) Laflèche F, Durand D, Nicolai T. Macromolecules. 2003;36:1331. [Google Scholar]; b) Pham QT, Russel WB, Thibeault JC, Lau W. Macromolecules. 1999;32:5139. [Google Scholar]; c) Zhulina EB, Borisov OV. Macromolecules. 2012;45:4429. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Semenov AN, Joanny JF, Khokhlov AR. Macromolecules. 1995;28:1066. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shen W, Kornfield JA, Tirrell DA. Macromolecules. 2007;40:689. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yokoyama H, Kramer EJ. Macromolecules. 2000;33:954. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thomas CS, Glassman MJ, Olsen BD. ACS Nano. 2011;5:5697. doi: 10.1021/nn2013673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bays E, Tao L, Chang C-W, Maynard HD. Biomacromolecules. 2009;10:1777. doi: 10.1021/bm9001987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hjelm R., Jnr Journal of Applied Crystallography. 1988;21:618. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.