Abstract

Despite much research on the beneficial effects of written disclosure, relatively little attention has been paid to specifying the mechanism underlying the effects. Building upon the two theoretical models (the cognitive adaptation model and the emotional exposure-habituation model), this research focused on two aspects of disclosure content—insights and emotions—and examined how women with breast cancer benefit from written disclosure in online support groups. Using survey data collected at baseline and after four months and messages posted in bulletin-board-type online groups in between, we analyzed how the content of disclosive messages predicted health outcomes. Disclosure of insights led to greater improvements in health self-efficacy, emotional well-being, and functional well-being, which was mediated by lowered breast cancer concerns. Disclosure of negative emotions did not have main effects on health outcomes; instead, it weakened the unfavorable association between concerns at baseline and functional well-being at follow-up. Our findings support both theoretical models, but in regard to different aspects of disclosure content.

Keywords: written disclosure, online support groups, breast cancer patients, insights, emotions

Theories of adaptation to trauma (such as cancer diagnosis and treatment) suggest that cognitive and emotional processing of traumatic experience leads to better adjustment (Creamer, Burgess, & Pattison, 1992; Lepore, 2001). One way to enhance cognitive and emotional processing is through communication behavior, i.e., disclosure of trauma-related thoughts and feelings (Pennebaker, 1989). Written disclosure in particular has received accumulating support for its positive impact on adjustment to health problems (Stanton, Danoff-Burg et al., 2002).

Despite much evidence on the beneficial effects of written disclosure, the mechanism underlying the effects remains unclear (Sloan & Marx, 2004a). This research builds upon two theoretical models which have been proposed to explain the mechanism. The cognitive adaptation model (Pennebaker, 1997a; Smyth, True, & Souto, 2001) claims that the benefits of written disclosure are achieved through cognitive resolution of a stressful event and reduction in intrusive thoughts, while according to the emotional exposure-habituation model (Lepore, 1997; Sloan & Marx, 2004b), it is habituation to negative affects and intrusive thoughts about a traumatic event that brings the benefits. Although much previous research has examined these models looking at the effects of disclosure versus non disclosure (e.g., Lange, Schoutrop, Schrieken, & Van de Ven, 2002), examining the actual content of disclosure can offer a more detailed explanation of its mechanism (Creswell et al., 2007). In the current research, we report data that lend support to both models, focusing on the content of disclosure reflected in its language use. We argue that the models are linked to different contents of written disclosure: specifically, we suggest the cognitive adaptation model can explain the benefits of disclosing insights about stressful experience, and the emotional exposure-habituation model the benefits of disclosing negative emotions about it.

The models are tested in the context of online support groups for women with breast cancer. Coping with breast cancer is a traumatic event with physical and psychological impacts (Spiegel, 1997) and active expression of suffering can improve adjustment to it (Stanton et al., 2000). Recent research has shown the benefits of insightful and emotional disclosure in online groups for breast cancer patients (e.g., Lieberman & Goldstein, 2006; Shaw et al., 2006) and awaits explanations on how the benefits are obtained. The data of this research came from a large project (Gustafson et al., 2005a, 2005b) concerning breast cancer patients’ use of online interactive health system, including bulletin-board-type online groups.

Written disclosure and health benefits

Disclosure is a communication process by which individuals verbally reveal their private thoughts, feelings, or experiences (Derlega et al., 1993; Jourard, 1971). Disclosure, especially written disclosure, has gained extensive attention due to its potential health benefits (Smyth, 1998).

The written disclosure paradigm was developed by Pennebaker and colleagues (e.g., Pennebaker & Beall, 1986) to examine the health effects of disclosure in an experimental setting. Typically, those assigned to the experimental condition are asked to write an essay expressing their deepest feelings and thoughts about a traumatic event in their life, while those in the control condition write about innocuous or superficial topics, such as their plans for the day (Smyth & Pennebaker, 2001). Participants in both conditions write for three to five consecutive days.

This written disclosure task has been found to produce significant benefits (Pennebaker, 1989, 1997a, 1997b). According to Smyth’s (1998) meta-analysis, written disclosure was reliably associated with positive health outcomes with a medium effect size among those in sound health. A meta-analysis on individuals with physical or psychiatric disorders (Frisina, Borod, & Lepore, 2004) also showed that written disclosure was associated with health improvements, with a small effect size. Particularly concerning women with breast cancer, Stanton, Danoff-Burg et al. (2002) found that patients who were randomly assigned to the disclosure condition reported fewer negative physical symptoms and fewer medical appointments after three months, than the non-disclosure group. Among prostate cancer patients, Rosenberg et al. (2002) found that written disclosure led to greater improvements in physical symptoms and health care utilization, but not in psychological factors.

Mechanisms underlying the health effects of written disclosure

How can written disclosure about traumatic events lead to physical and psychological gains? Several theoretical models have been offered to explain the mechanism underlying the written disclosure process, awaiting further empirical evidence (Sloan & Marx, 2004a). This study focuses on two models: the cognitive adaptation model (Pennebaker, 1997a; Smyth, True, & Souto, 2001) and the emotional exposure-habituation model (Lepore, 1997; Sloan & Marx, 2004b).

The first model concerns cognitive adaptation to traumatic experiences through written disclosure (Pennebaker, 1997a). Horowitz (1986) suggests recovery from a traumatic experience requires resolution of the discrepancy between one’s existing inner model and the information newly acquired from the traumatic experience. Through written disclosure, individuals gain an opportunity to build cohesive organization and structure to their traumatic experience, which they may not have developed initially (Sloan & Marx, 2004a; Smyth, True, & Souto, 2001). By translating traumatic experience into words, individuals are able to acquire new insight to reframe the experience (Pennebaker & Beall, 1986). Once they reach a cognitive resolution, there is no more reason to continue to ruminate about it. This in turn may lead to decreased stress and improved mental and physical health over a long period of time (Pennebaker, 1989, 1997a).

This model has been typically tested by analyzing the language used in writing about traumas, such as insight words and causal words (Shaw et al., 2006) or the content of disclosure (Cresswell et al., 2007) thought to reflect cognitive processing. For example, the benefits from disclosure were positively associated with an increase in the use of insight words (e.g., understand) and causal words (e.g., reason) over the days of writing (Pennebaker, Mayne, & Francis, 1997; Pennebaker & Seagel, 1999). This model has also been tested by examining changes in the frequency of intrusive or ruminating thoughts (Lepore, Greenberg, Bruno, & Smyth, 2002). To the extent that individuals can cognitively integrate stressful events, they are expected to show a decrease in, or possibly be free from, intrusive thoughts (Lepore, Greenberg et al., 2002). Findings from studies have been mixed, however, such that only one of the two studies in Lange et al. (2002) found the effect of cognitive reappraisal on reduction in intrusive thoughts.

The emotional exposure-habituation model conceptualizes the written disclosure procedure as a context in which individuals are exposed to stressful stimuli (Sloan and Marx, 2004b). Successful results from exposure-based treatments can be achieved when a person experiences intense negative emotion confronting with an aversive stimulus, followed by a gradual decrease in the negative emotion within and between stimulus presentations (Foa & Kozak, 1986). While writing about traumatic events, individuals describe both their experience and responses, and they also have negative affect evoked by remembering the stressful experience (Lepore, Greenberg et al., 2002). Through repeated exposure to the aversive stimuli, the written disclosure process may facilitate habituation to both stimuli and responses, extinguish negative emotional associations, and ultimately bring beneficial outcomes to the writer (Lepore, 1997; Sloan & Marx, 2004a).

Researchers have tested this model by observing the activation and subsequent habituation of negative affect during and across writing sessions (Sloan & Marx, 2004a). The amount of increase in negative mood after disclosure became smaller across days of writing while the amount of decrease in positive mood increased slightly over days (Lepore, Greenberg et al., 2002; but see Kloss & Lisman, 2002). Sloan and Marx (2004b) found physiological activation to the first writing session was related to psychological benefits at follow-up, and subjective reports corresponded with physiological measures. Another method to test this model is examining the patterns and effects of posttraumatic symptoms, such as intrusive thoughts (Sloan & Marx, 2004a). Consistent with the model, some studies found the negative associations of intrusive thoughts with physical and psychological symptoms were weakened by disclosure (Lepore & Greenberg, 2002). Thus, written disclosure reduced unfavorable symptoms by attenuating the negative effects of intrusive thoughts, rather than by decreasing the number of intrusive thoughts (Lepore, 1997).

In sum, both models have been supported to some degree. When two mechanisms were directly compared, Lepore (1997) found support for the exposure-habituation mechanism; however, in one study by Lange et al. (2002), cognitive adaptation was found to be more effective than exposure-habituation. One reason for equivocal evidence for these models could be that more than one model may account for positive effects of disclosure (Sloan & Marx, 2004a). Instead of ruling out one model, this research distinguishes between the subcategories of disclosure by its content and links them to different mechanisms. Specifically, we argue that disclosure of insights about stressful experience can bring benefits through cognitive adaptation, and disclosure of negative emotions surrounding the experience through emotional exposure-habituation.

Health benefits from disclosure in online support groups for breast cancer patients

Being diagnosed with breast cancer and getting treatments is a deeply traumatic experience with physical and psychological impacts (Spiegel, 1997) that often accompanies depression, changes in physical appearance, and decline in subjective quality of life (Ganz, 2000). Suffering from these symptoms may elicit intense emotions in patients and hence facilitate their desire to talk to others experiencing similar problems. Indeed, support groups and group therapy are common and successful resources for breast cancer patients (Lieberman & Goldstein, 2005).

Online support groups, as well as traditional face-to-face groups, are widely used among women diagnosed with breast cancer (Fogel et al., 2002). Breast cancer patients ranked high in the frequency of posting in online groups among those evaluated (Davison, Pennebaker, & Dickerson, 2000). They were also the most emotional and engaging of the sampled groups across different disease contexts, including heart disease, breast cancer, prostate cancer, arthritis, diabetes, and chronic fatigue syndrome (Davison & Pennebaker, 1997).

Several studies have assessed the effects of participation in online support groups for breast cancer patients and found that it can be efficacious in improving their mental health and quality of life (e.g., Lieberman & Goldstein, 2005; Owen et al., 2005). These benefits are conceived as coming from the exchange of supportive communication among peer patients (Lewis, 1999). For a better understanding of these benefits, it would be necessary to focus on one element of communicative participation, such as written disclosure, independent of the receipt of support (Lieberman & Goldstein, 2006). Since expressing concern or support is an effective elicitor of intimate disclosure (Berg & Archer, 1980), supportive communication in online support groups may constitute an open context in which to disclose one’s thoughts and feelings.

The written disclosure paradigm applied to online groups

Posting disclosive messages in asynchronous online groups shares a similarity with written disclosure tasks promoted by Pennebaker (e.g., Pennebaker & Beall, 1986). While writing in either setting, people are likely to stay physically alone without facing visible communication partners, and attend to their inner thoughts and feelings, rarely being interrupted by external factors. Therefore, it would be reasonable to apply the models explaining mechanisms underlying the written disclosure paradigm—cognitive adaptation and emotional exposure-habituation—to the context of online support groups. And applying these models, it is important to examine the content of disclosure in online groups, which reflects the cognitive and emotional processing of breast cancer-related experiences, and look at how it is associated with potential health outcomes.

One distinctive method for the content analysis is to examine linguistic patterns occurring in written disclosure (Owen, Yarbrough, Vaga, & Tucker, 2003). In the research domain on online disclosure and more generally on the written disclosure paradigm, the Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count (LIWC, Pennebaker, Chung, Ireland, Gonzales, & Booth, 2007; Pennebaker & Francis, 1996) has been used widely. LIWC is a computerized text analysis program that searches different words or word fragments in texts and categorizes them into certain dimensions, such as cognitive processing and emotional processing.1 The LIWC analysis has been evaluated to see its validity in analyzing posts in online support groups, including the content validity, concurrent validity, and construct validity (Alpers et al., 2005).

Recent studies have applied LIWC analysis to asynchronous online support groups for breast cancer patients. Owen et al. (2005) assessed whether the use of words in disclosure that contained emotion or cognitive mechanism was associated with changes in health outcomes, using measures such as the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-Breast Cancer Form (FACT-B: a multidimensional quality of life measure consisting of subscales of social well-being, physical well-being, emotional well-being, functional well-being, and breast cancer concerns, Brady et al, 1997) and the Impact of Event Scale (Horowitz, Wilner, & Alvarez, 1979). Disclosure of negative emotions was related to positive changes in emotional well-being and reductions in intrusive thoughts. Disclosure of cognitive processing was positively associated with improvement in emotional well-being. Focusing on insight word categories of LIWC, Shaw et al. (2006) examined the effects on FACT-B (physical well-being, emotional well-being, and breast cancer concerns) and negative mood. Hypotheses gained partial support, such that insightful disclosure in an online group had a positive association with improvement in emotional well-being in the first period, but not in the second period or in the whole time period. Insightful disclosure was associated with lower levels of negative mood in the whole time period, but not with breast cancer concerns and physical well-being. Lieberman and Goldstein (2006) focused on disclosure of negative emotions and examined its effects on FACT-B (physical well-being, functional well-being, and breast cancer concerns) and depression. At 6-month follow-up, expressing negative emotions led to psychosocial improvement not in and of itself, but in the context of cancer. Not all types of negative emotional expression produced equal consequences. Expression of anger was related to higher quality of life and lower depression, but expression of fear and anxiety had opposite relations. Despite the significance of previous findings, however, they have limitations in addressing why and how use of certain words in disclosure is associated with improved outcomes.

Research questions and hypotheses

This research aims to expand and elaborate on previous research on written disclosure in online groups for breast cancer patients. First, this research attempts to replicate findings on the benefits of disclosing insights or negative emotions in online groups (e.g., Lieberman & Goldstein, 2006; Owen et al., 2005; Shaw et al., 2006) and also to examine the understudied aspect of disclosing positive emotions in online groups. More importantly, this research aims to contribute to the literature by providing theoretical explanations about the mechanisms under which insightful and emotional disclosure in online groups brings potential health benefits to disclosers.

We hypothesize that breast cancer patients will experience health benefits through disclosure of insights (H1) and negative emotions (H2) in online support groups, based on previous research. We also hypothesize about the benefit of disclosing positive emotion (H3). A few experimental studies suggest that disclosure of positive aspects of a traumatic or stressful event may be as effective as disclosing deepest thoughts and negative emotions (e.g., King & Miner, 2000; Stanton, Danoff-Burg et al., 2002), and it would be interesting to see whether the finding can be replicated in online support groups for breast cancer patients. The hypotheses concern three types of health outcomes. Health self-efficacy taps into patients’ beliefs about their ability to cope with illness and manage their health. Self-efficacy is specific to tasks and situation in reference to certain goals (Bandura, 1997), and when patients are actively disclosing their insightful thoughts and related emotions, it can strengthen their confidence in their ability to adjust to the disease and achieve health-related goals. Emotional well-being and functional well-being are subcategories of quality of life in breast cancer patients (Brady et al., 1997). Emotional well-being concerns perceived psychological health whereas functional well-being assesses self-reported physical functioning, and both aspects have been studied as important health outcomes of disclosure in online groups:

H1. Written disclosure of insights in online groups will be associated with greater improvements in health outcomes (health self-efficacy, emotional well-being, and functional well-being).

H2. Written disclosure of negative emotions in online groups will be associated with greater improvements in health outcomes.

H3. Written disclosure of positive emotions in online groups will be associated with greater improvements in health outcomes.

Of greater importance to this research is to explore the mechanisms underlying the benefits of writing insightful and emotional disclosure in online groups. This research examines the two models—the cognitive adaptation model and emotional exposure-habituation model—that have been offered to explain mechanisms underlying the effects of written disclosure, and suggests that the models are linked to different contents of written disclosure. Specifically, we hypothesize that disclosure of insights will bring improvements on health outcomes through the mechanism of cognitive adaptation (H4) whereas disclosure of negative emotions will produce benefit through emotional habituation (H5). The hypotheses are posited focusing on the role of intrusive thoughts, defined as unwelcome thoughts or concerns about traumatic experiences (Sloan & Marx, 2004a). Having intrusive thoughts is considered to indicate incomplete accomplishment of cognitive processing of traumas, and each model offers different explanations about the mediating role of intrusive thoughts in the relation between disclosure and adjustment to stressors (Lepore, 1997). Specifically, the cognitive adaptation model posits that disclosure results in a reduction in intrusive thoughts to the extent that people can cognitively integrate stressful events, whereas the emotional habituation model suggests disclosure may not reduce intrusive thoughts but it rather emotionally desensitizes people to those thoughts. In this research, breast cancer concerns is used as a surrogate measure of intrusive thoughts. The hypothesized mechanisms suggest that disclosure of insights will lead to a greater decrease in breast cancer concerns (H4), but disclosure of negative emotions will alleviate unfavorable impacts of breast cancer concerns (H5). The mechanism underlying the effects of disclosing positive emotions is unclear and we pose a research question to see which of the two models gains support in this context (RQ1):

H4. Written disclosure of insights will be associated with fewer breast cancer concerns at follow up, which in turn will be related to greater improvements in health outcomes at follow-up.

H5. Written disclosure of negative emotions will alleviate the negative relations between breast cancer concerns at baseline and health outcomes at follow-up.

RQ1. Does written disclosure of positive emotions bring health benefits by reducing breast cancer concerns or alleviating the negative effect of concerns?

Methods

This research analyzed data collected as part of a larger project (Gustafson et al., 2005a, 2005b). The project aimed at reaching low-income women with breast cancer through Comprehensive Health Enhancement Support System (CHESS), and examining their use of the system and its impacts on their quality of life. CHESS is an online system designed to provide services for information, social support, and decision making to those coping with a health crisis. Of the larger project, this research focused on patients’ participation in bulletin-board-type online groups, as well as their baseline and four-month follow-up surveys.

Participants

Participants were recruited through multiple sources, such as the National Cancer Institute’s Cancer Information Service, hospitals, and self-referral (Gustafson et al., 2005a, 2005b). A key eligibility criterion was income, with those who were living below or at 250% of the official federal poverty line being eligible.2 Other criteria included that they must be within one year of diagnosis or had metastatic breast cancer, not homeless, and capable of reading and understanding an informed consent letter. Participants were asked to fill out surveys at baseline and again after four months. They were told their computer use would be monitored. Participants were loaned a computer with Internet access for four months, and if necessary, telephone lines were provided. They also received in-house computer training to learn how to use CHESS.

Two hundred and eighty-six women were enrolled in the project and about 81% of them (N = 231) completed both baseline and follow-up surveys. Participants were recruited in rural Wisconsin areas from May 2001- April 2003 and in Detroit, Michigan from June 2001 - April 2003. Ninety-five women never posted a disclosive message,3 30 women posted one disclosive message, and 106 women posted two or more. In this research, only those who posted two or more disclosive messages were included for analysis. People may need to write at least a certain number of messages to gain benefits from insightful or emotional disclosure in online groups (Shaw et al., 2006; Shaw et al., 2007). The first disclosive message written by a participant was typically a short introduction about her background, and posting merely one message and not writing again might be insufficient to engage in insightful or emotional processing.4 The demographic and background characteristics of participants are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic and background characteristics of participants

| Project participants (N = 231) |

Posters of two or more disclosive messages (N = 106) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| Mean (SD) | 51.58 (11.81) | 49.08 (11.35) |

| Education | ||

| Mean (SD) | 3.92 ( 1.31) | 3.96 ( 1.22) |

| Level | ||

| 1 Some Junior HS | 0.9% | 0.0% |

| 2 Some HS | 10.4% | 9.4% |

| 3 HS degree | 31.2% | 29.2% |

| 4 Some College | 29.9% | 32.1% |

| 5 Associate or Tech degree | 12.1% | 17.0% |

| 6 BA degree | 12.1% | 9.4% |

| 7 Graduate degree | 3.5% | 2.8% |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| White Americans | 62.3% | 78.3% |

| African Americans | 35.9% | 21.7% |

| Health insurance | ||

| Having insurance | 91.3% | 92.5% |

| Not having insurance | 8.7% | 7.5% |

| Living situation | ||

| Living alone | 27.3% | 34.0% |

| Living with someone else | 72.7% | 66.0% |

| Perceived social support | ||

| Mean (SD) | 2.95 ( .86) | 2.84 ( .84) |

| Stage of cancer | ||

| Early (0, 1, 2) | 70.1% | 66.0% |

| Late (3, 4, or inflammatory) | 29.9% | 34.0% |

| Physical impairment | ||

| Normal with no complaints | 35.1% | 26.4% |

| Normal with minor illness | 39.8% | 46.2% |

| Needed occasional assistance | 19.9% | 20.8% |

| Disabled, needed special care | 5.2% | 6.6% |

Note. Values are either means (and standard deviations in the parentheses) or column percentages, for each background characteristic of participants.

Measures

Outcome and mechanism variables

The variables were assessed by surveys, both at baseline and at 4-month follow-up:

Health self-efficacy. Participants responded to three items on self-efficacy in managing their health during the past seven days: e.g., I am confident that I can have a positive effect on my health. Responses were scored on a five-point scale (0 = disagree very much to 4 = agree very much) and averaged to construct a scale (Cronbach’s alphas = .76 at baseline and .80 at follow-up).

Emotional well-being. Emotional well-being was one component of multidimensional quality of life, measured with FACT-B (Brady et al, 1997).5 Six refined items were assessed on a 5-point scale (0 = not at all to 4 = very much): e.g., I feel sad; I feel like my life is a failure. Responses were reverse coded before they were averaged into a scale (alphas = .86 at baseline and .85 at follow-up) so that a higher score indicates a greater level of well-being.

Functional well-being. Functional well-being was another component of the FACT-B, assessed with five items: e.g., I am able to work (include work at home); I am sleeping well. Responses were scored on a five-point scale (0 = not at all to 4 = very much) and later averaged to construct a scale (alphas = .84 at baseline and .85 at follow-up).

Breast cancer concerns. Breast cancer concerns were measured with eleven items adapted from the FACT-B. Participants were asked to indicate the extent to which they had felt the following during the past seven days: e.g., I worry about effect of stress on illness; I am bothered by a change in weight; I am able to feel like a woman (reverse coded). Responses (0 = not at all to 4 = very much) were averaged into an index (alphas = .74 at baseline and .72 at follow-up).

Disclosure variables

Disclosure variables were constructed, analyzing the messages each person posted in online groups between two waves of surveys. We used a computerized text analysis program LIWC20076 and computed the percentages of words conveying insights, negative emotion, and positive emotion in messages. Percentages of words were computed, rather than raw word counts, to assess how much of a person’s writing is related to cognitive and emotional processes after adjusting for individual differences in the amount of writing (Pennebaker, Mayne, & Francis, 1997).

Disclosure of insights. The percentage of insight words (e.g., think, know, consider7) in disclosive messages was computed for each person, by dividing the number of insight words she used in all her posts by the total word count for all posts.

Disclosure of negative emotions. This variable represented the percentage of negative emotion words (e.g., hurt, nervous, annoyed) used by each participant, i.e., the number of negative emotion words divided by the total word count in the entire body of her posts to online groups.

Disclosure of positive emotions. The percentage of positive emotion words (e.g., love, nice, sweet) was computed in the entire set of disclosive messages posted by each person.

In the following excerpt with a total word count of 67 words, there are 3 insight words (find, finding, and information), 1 negative emotion word (scared), and 4 positive emotion words (positive, thanks, sharing, and positive). Its writer is thus coded as using about 4.5% (= 3 / 67) of insight words, 1.5% of negative emotion words, and 6.0% of positive emotion words in disclosure:

Long road ahead of me, but as I communicate with more CHESSlings, I find myself talking more positive and seeing a future beyond what is still to come. As I have read more messages, I keep finding out more information thanks to everyone sharing. My main objective is to stay positive as much as possible. I’m still scared, but that will pass too. Let’s talk again soon.

Control variables

The analyses included control variables to minimize confounding effects caused by third factors such as demographic and background characteristics. Overall use of CHESS was also controlled so that the influence of disclosure in online groups could be examined over and beyond the effect of using other CHESS services.

Demographics. Demographic information was assessed at baseline: age, the level of highest education (1 = some junior high school to 7 = graduate degree), and race (1 = Whites, 0 = others).

Background characteristics. Baseline survey assessed other background characteristics: having health insurance (1 = yes, 0 = no), stage of cancer (1 = stage 0, 1, or 2 coded as early stage, 0 = stage 3, 4, and inflammatory coded as late stage), living situation (1 = living by oneself, 0 = living with someone else), perceived physical functional impairment (1 = feeling normal with no complaints and able to carry on your usual activities to 4 = disabled, requiring special care and assistance in most activities and in bed more than 50 percent of the daytime), and perceived social support (assessed with six items8 being averaged into a scale, 0 = not at all to 4 = very much).

Overall use of CHESS. Participants’ navigation through websites was tracked and saved in real time, and from this data, the average amount of time spent on CHESS per week during the period they used the system was computed.9

Results

Descriptive analyses

We first checked the descriptive statistics of outcome variables assessed at baseline and at follow-up among those who posted two or more disclosive messages. Health self-efficacy became higher from baseline, M (SD) = 2.79 (.76), to follow-up, M (SD) = 3.05 (.68), at a statistically significant level, t (105) = 3.46, d = .36, p = .001. Such increase was also found with emotional well-being, M (SD) = 2.35(.98) at baseline; M (SD) = 2.70 (.89) at follow-up, t (105) = 3.92, d = .37, p < .001, and with functional well-being, M (SD) = 2.29 (.96) at baseline; M (SD) = 2.48 (.94) at follow-up, t (105) = 2.47, d = .21, p = .015. Breast cancer concerns decreased over time, Ms (SDs) = 1.88 (.72) to 1.74 (.66), t (104) = 2.51, d = .21, p = .014.

Descriptive analyses of disclosure variables were also conducted. Patients wrote on average 29 disclosive messages (SD = 64.2) in online groups. The distribution was skewed to the right with a maximum of 853 posts and median of 17 posts. They used insight words comprising on average 2.5 percent (SD = 1.0) of words in their disclosive messages. The mean for percentage of negative emotion words each person used in disclosure was 1.4% (SD = .7). The mean percentage of positive emotion words used by each person was 5.4% (SD = 2.7).

The longitudinal associations of insightful or emotional disclosure with health outcomes

This study examined the longitudinal impacts of disclosing insights or emotions in online groups on women with breast cancer. We hypothesized that using a higher percentage of insight words (H1), negative emotion words (H2), and positive emotion words (H3) in disclosure will be associated with greater improvements in health outcomes (health self-efficacy, emotional well-being, and functional well-being) at follow-up. The hypotheses were tested with Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) multiple regressions. We employed a regressed change approach following Cohen, Cohen, West, and Aiken’s (2002) suggestion, instead of using a difference score of outcome variables between baseline and follow-up as the dependent variable which may have problems of overcorrection of the postscore by the prescore and susceptibility of ceiling effects (Cohen et al., 2002). In the first step of regressions, the baseline score of health outcome was entered as a control variable. Demographic and background characteristics as well as overall use of CHESS were entered in the next step. In the last step, the percentages of insight words, negative emotion words, and positive emotion words used in disclosure were entered as main predictors. These percentages of words and overall CHESS use were square root transformed to eliminate skewness.

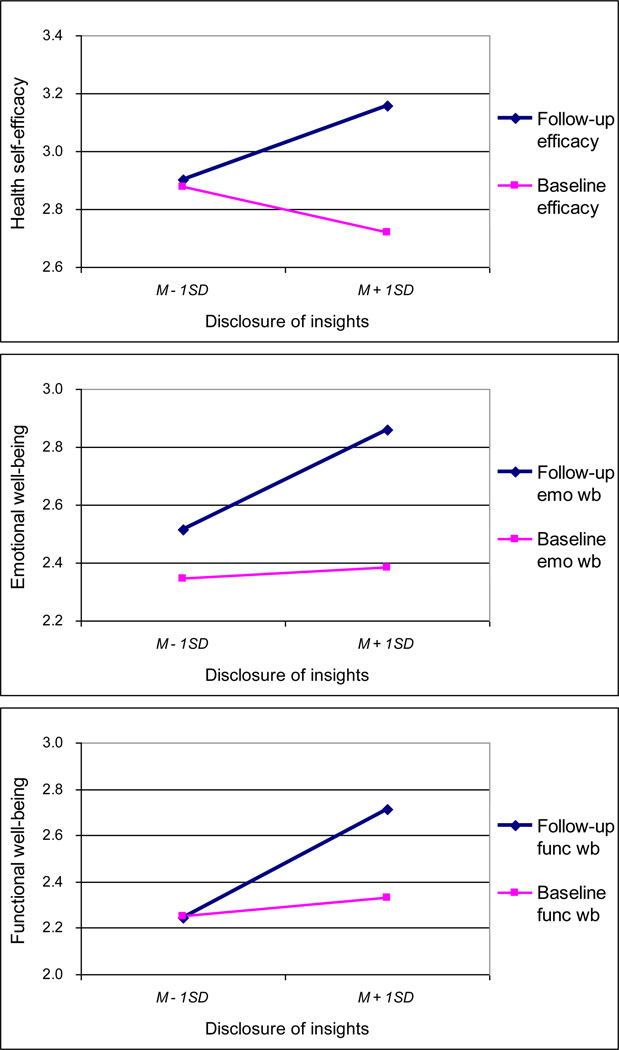

Results showed that disclosure of insights in online support groups brought benefits to disclosers (see Table 2). As patients used a higher percentage of insight words in their disclosive messages, they showed greater improvements in all three outcomes after four months, over and beyond the effects of control variables. These findings are depicted in Figure 1. While the entire sample had improvements in health outcomes from baseline to follow-up, the magnitude of improvements enlarged as people disclosed a greater level of insights. However, the hypothesized associations between disclosure of negative emotions or positive emotions and follow-up health outcomes were not supported.10

Table 2.

Associations between disclosure in online groups and follow-up health outcomes

| Health self-efficacy |

Emotional well-being |

Functional well-being |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline outcomes | |||

| Health self-efficacy | .31*** | ||

| Emotional well-being | .48*** | ||

| Functional well-being | .34*** | ||

| R2 change (%) | 19.3*** | 30.4*** | 40.6*** |

| Control variables | |||

| Age | .11 | .06 | −.02 |

| Education | .08 | .01 | −.15* |

| Ethnicity (White) | −.33*** | −.00 | .07 |

| Health insurance | −.04 | −.02 | .02 |

| Living alone | −.09 | −.08 | −.07 |

| Social support | .05 | .02 | .16 |

| Early stage of cancer | −.13 | −.11 | −.04 |

| Physical impairment | −.25** | −.25** | −.33*** |

| Overall CHESS use | .00 | −.15 | −.03 |

| R2 change (%) | 13.9* | 9.2 | 14.5** |

| Disclosure variables | |||

| Disclosure of insights | .19* | .19* | .25** |

| Disclosure of negative emotions | −.08 | −.01 | .06 |

| Disclosure of positive emotions | −.22** | .11 | .05 |

| R2 change (%) | 7.1* | 3.5 | 6.0** |

Note. N = 106.

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001. Cell entries are standardized final betas.

Figure 1.

Disclosure of insights and improvements in health outcomes

Note. N = 106. The y-axis represents health outcomes assessed at either follow-up or baseline. Follow-up values refer to the predicted values acquired from multiple regressions reported in Table 3 (M = 3.06, SD = .44, health self-efficacy; M = 2.69, SD = .59, emotional well-being; M = 2.48, SD = .74, functional well-being). Baseline values refer to the predicted values from regression disclosure of insights as a predictor with other controls (M = 2.80, SD = .34, health self-efficacy; M = 2.37, SD = .43, emotional well-being; M = 2.29, SD = .67, functional well-being). The x-axis indicates disclosure of insights in online groups (M = 1.53, SD = .41).

Mechanisms underlying the health benefits from insightful or emotional disclosure

Cognitive adaptation: Breast cancer concerns as a mediator of the effects of disclosure

Supporting the cognitive adaptation model, H4 proposed that disclosure of insights will be associated with fewer breast cancer concerns at follow up and thereby produce health benefits. This hypothesis was tested following Baron and Kenny’s (1986) suggestion of path analysis in regression. First, OLS regression was conducted using breast cancer concerns at follow-up as the dependent variable and disclosure variables as predictors, after controlling breast cancer concerns at baseline and other relevant variables. The three disclosure variables accounted for about 4.8 percent of variance in the dependent variable (p = .029), and of them, disclosure of insights had a significant association with a reduction in breast cancer concerns after four months (β = −.23, p = .008). That is, the magnitude of decrease in breast cancer concerns became larger as used a higher percentage of insight words in their disclosure. However, disclosure of negative emotions and positive emotions had no significant associations with fewer concerns at follow-up.

Given that insightful disclosure is associated with fewer breast cancer concerns at follow-up, we proceeded to the next step of path analysis. Regressions were conducted respectively for three health outcomes at follow-up as the dependent variable. We added the follow-up measure of breast cancer concerns as an additional predictor to the models reported in Table 2. Of interest was whether the association between the independent and dependent variables became absent or weaker after controlling the mediator. Follow-up breast cancer concerns was negatively associated with follow-up outcomes of health self-efficacy (β = −.24, p = .016), emotional well-being (β = −.24, p = .013), and functional well-being (β = −.28, p = .000). More importantly, the associations between disclosure of insights and follow-up outcomes became weaker after the follow-up measure of breast cancer concerns was added. The standardized coefficient of disclosure of insights on health self-efficacy changed from .19 to .11 and it became non-significant. Similar patterns were found with emotional well-being (β changed from .19 to .12) and with functional well-being (from .25 to .17).

In addition to the path analysis, more rigorous tests of mediation were conducted using the Sobel test (Sobel, 1982) and the bootstrap approach (Preacher & Hayes, 2004, 2008a, 2008b). Preacher and Hayes (2004, 2008b) argue that the Sobel test becomes less conservative in testing small samples and its assumption about the normal distribution of the indirect effect under the null hypothesis is easily violated. As an alternative method, they recommend using the bootstrap approach (2004, 2008b), that is, empirically bootstrapping the sampling distribution of the indirect effect and obtaining its confidence interval. The SPSS macro for both the Sobel test and the bootstrap approaches, developed by Preacher and Hayes (2008a), was downloaded from the researcher’s webpage11 and used. As Table 3 presents, the Sobel test (with the significance of z values being tested with one-tailed p values) supported that breast cancer concerns at follow-up mediates the relationship between disclosure of insights in online groups and health outcomes at follow-up. The bootstrapping approach showed that the 95% confidence interval for each health outcome did not include 0, and thus, also supported the mediating role of breast cancer concerns.

Table 3.

Mediation of the association between disclosure of insights and follow-up health outcomes through follow-up breast cancer concerns

| Health self-efficacy |

Emotional well-being |

Functional well-being |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct and total effects: Coefficients | |||

| IV on mediator | −.54*** | −.48** | −.48† |

| Mediator on DV | −.24* | −.32* | −.39*** |

| Total effect of IV on DV | 31† | .43* | .58** |

| Direct effect of IV on DV | .18 | .27 | .39* |

| Formal tests of the indirect effect | |||

| Sobel: z value | 1.90* | 1.85* | 2.23* |

| Bootstrapping: 95% CI | .015 – .353 | .031 – .357 | .059 – .407 |

Note. N = 106.

p < .06,

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001.

IV refers to disclosure of insights; mediator is breast cancer concerns at follow-up; DV refers to each of the health outcomes (health self-efficacy, emotional well-being, and functional well-being) assessed at follow-up. Individual background characteristics and baseline variable were also entered in the analyses as covariates. The significance of Sobel z value was tested with one-tailed p values.

Taken together, data supported the cognitive adaptation model with regard to disclosure of insights in online groups, such that the effect of insightful disclosure on health benefits was mediated through fewer breast cancer concerns. Disclosure of negative or positive emotions was not associated with reduced breast cancer concerns. Consistent with our hypothesis, the cognitive adaptation model was supported for disclosure of insights, and not for disclosure of emotions.

Emotional habituation: The impacts of breast cancer concerns alleviated by disclosure

The emotional exposure-habituation model was also tested for a plausible mechanism underlying the effects of written disclosure on health outcomes. H5 posited that disclosure of negative emotions will alleviate the negative associations that breast cancer concerns at baseline has with health outcomes at follow-up. RQ1 asked which mechanism can explain the benefits of disclosing positive emotions; the previous section shows that cognitive adaptation is not a valid explanation, and here we examine emotional habituation in regard to disclosure of positive emotions. OLS multiple regressions were conducted. The dependent variable was each of the health outcomes measured at follow-up. The first step of regressions included disclosure variables (that is, square root transformed percentages of insight words, negative emotion words, and positive emotion words used in disclosive messages)12 and control variables, same as the models in Table 2. In the next step, we added the baseline measure of breast cancer concerns and its cross-products with disclosure variables (after both variables being mean-centered). Table 4 reports final standardized coefficients from the regressions.

Table 4.

Disclosure as a moderator of the effects of baseline breast cancer concerns on follow-up health outcomes

| Health self-efficacy |

Emotional well-being |

Functional well-being |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline outcomes | |||

| Health self-efficacy | .29** | ||

| Emotional well-being | .52*** | ||

| Functional well-being | .35*** | ||

| Control variables | |||

| Age | .11 | .08 | −.02 |

| Education | .12 | .04 | −.11 |

| Ethnicity (White) | −.32*** | −.03 | .10 |

| Health insurance | −.02 | −.02 | .04 |

| Living alone | −.12 | −.06 | −.09 |

| Social support | .05 | .04 | .18* |

| Early stage of cancer | −.13 | −.12 | −.05 |

| Physical impairment | −.15 | −.26* | −.21* |

| Overall CHESS use | −.01 | −.15 | −.03 |

| Disclosure variables | |||

| Disclosure of insights | .12 | .23* | .20* |

| Disclosure of negative emotions | −.03 | −.01 | .14 |

| Disclosure of positive emotions | −.25** | .12 | .04 |

| BC concerns variables | |||

| BC concerns at baseline | −.13 | .07 | −.12 |

| BC concerns x Disclosure of insights | .07 | −.08 | .01 |

| BC concerns x Disclosure of negative emo | .13 | .03 | .18* |

| BC concerns x Disclosure of positive emo | −.14 | −.06 | −.09 |

| R2 change (%) by BC variables | 3.7 | 0.9 | 3.3* |

Note. N = 106.

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001. R2 change values were obtained from the final step in which variables regarding breast cancer concerns (e.g., the baseline score on breast cancer concerns and three interaction terms with disclosure variables) were newly added.

Disclosing negative emotions in online support groups moderated the negative association of baseline breast cancer concerns with one of the follow-up outcomes—functional well-being. By writing a higher percentage of negative emotion words in their disclosure, breast cancer patients were able to weaken the unfavorable effect of breast cancer concerns at baseline on functional well-being at follow-up. For a better understanding of this interaction effect, we calculated the standardized regression coefficients of breast cancer concerns on functional well-being at five different values of disclosure of negative emotion—at the minimum, at one standard deviation below the mean, at the mean, at one standard deviation above the mean, and at the maximum (Cohen et al., 2002). The coefficients were −.33, −.18, −.12, −.07, and .00, respectively. Among those who were less likely to express negative emotions in their disclosure, the negative association between baseline concerns and follow-up functional well-being was stronger. This unfavorable association became weaker as patients expressed a greater level of negative emotions when writing disclosive messages in online groups. However, disclosure of positive emotions did not have interaction effects with baseline concerns, and we failed to address our research question about the associations between positive emotional disclosure and health outcomes. Disclosure of insights also had no interaction with baseline concerns, suggesting that cognitive adaptation (supported in the previous section), not emotional habituation, is a valid mechanism underlying the beneficial impacts of insightful disclosure.

In sum, data provided partial support for the emotional exposure-habituation model with regard to disclosure of negative emotions. The hypothesized interaction effect was found on one of the three outcomes, functional well-being. Consistent with our hypothesis, the emotional exposure-habituation model accounted for benefits from disclosure of negative emotions, and not for those from disclosure of insights. Health benefits from disclosure of positive emotions were not observed in this study, either through cognitive adaptation or through emotional habituation.

Discussions

This study examined whether and how insightful or emotional disclosure in online groups brings potential health benefits to disclosers. Overall, we found that disclosure of insights in online groups had stronger effects on enhancing health benefits than disclosure of emotions did. The positive role of insightful disclosure in online groups for breast cancer patients was also found in past research. Shaw et al. (2006) found insightful disclosure was associated with improved emotional well-being and reduced negative mood at follow-up, but not with breast cancer concerns or physical well-being. Replicating the study, Lieberman (2007) found that insightful disclosure led to better functional well-being and fewer breast cancer concerns at follow-up and showed a trend toward significance on less emotional distress. In the current research, insightful disclosure was significantly associated with all outcomes at follow-up—greater improvements in health self-efficacy, emotional well-being, and functional well-being, and fewer breast cancer concerns.

This research moved forward from previous research in speculating how disclosure of insights can have such beneficial effects on the disclosers. As hypothesized and consistent with the cognitive adaption model (Pennebaker, 1989, 1997a; Smyth, True, & Souto, 2001), disclosure of insights in online groups brought health benefits to breast cancer patients by reducing their breast cancer concerns from baseline to follow-up, which in turn was associated with greater health benefits at follow-up.

The way in which disclosure of negative emotions in online groups had a positive effect on functional well-being was different. Consistent with the emotional exposure-habituation model (Lepore, 1997; Sloan & Marx, 2004b), disclosing a greater level of negative emotions was associated with improvements in functional well-being at follow-up by desensitizing patients to their breast cancer concerns. Negative emotional disclosure did not affect the amount of breast cancer concerns, but it moderated the unfavorable association of breast cancer concerns at baseline with functional well-being at follow-up. However, it is not clear why the moderating role of negative emotional disclosure on other outcomes was not found in this research whereas it was supported in past studies employing experiments (e.g., Lepore, 1997; Lepore & Greenberg, 2002).

To summarize, data lent support to both the cognitive adaptation model and the emotional exposure-habituation model. The results reveal that these two mechanisms do not conflict with each other, but rather work simultaneously through distinct paths of action—either through processing of cognition or through processing of negative emotion. More importantly, the findings suggest that it is important to focus on different aspects of disclosure content that are associated with different mechanisms underlying the benefits from written disclosure. Further research is needed to examine both models simultaneously under a single rubric of reappraisal or regulation, to understand the written disclosure process more fully (Lange et al., 2002; Sloan & Marx, 2004a).

When comparing the effects across health outcomes, enhanced functional well-being was associated with both insightful and negative emotional disclosure whereas improvement in emotional well-being was associated only with insightful disclosure. The result on the impact of insightful disclosure on functional well-being was consistent with previous research on breast cancer patients in online groups (e.g., Lieberman, 2007). However, unlike the current study, other research with breast cancer patients (Owen et al., 2005) found that emotional well-being was also improved by negative emotional disclosure, and we need to consider why this effect was not found in this research with the data from low-income women. It is possible that low-income patients may need other aids (in addition to disclosive writing) to improve the level of their emotional well-being. Further research is necessary to compare across different outcomes in this population.

Disclosure of positive emotions was not found to be associated with health benefits in this research. There was one significant pattern, but the direction was opposite to what our hypothesis predicted, such that the size of increase in health self-efficacy from baseline to follow-up was larger among those who made less positive emotional disclosure in online groups. One possible interpretation is that when breast cancer patients who are undergoing serious illness and problems express higher levels of positive emotions, they are less likely to acknowledge their difficult situation and to try to enhance their efficacy to cope with it. Future research is invited to unravel the effects, either beneficial or detrimental, of disclosing positive emotions among those having serious health problems.

This study investigated disclosive messages posted in online support groups in a home-based natural setting. It is worth mentioning that study participants were not guided on how to write about their cancer experiences and related thoughts and feelings in online support groups, unlike in the written disclosure task paradigm in the laboratory. Even without an explicit guidance, some patients wrote disclosive messages in a desirable way that helped them make sense of their stressful experience and get habituated to the relevant negative emotion. And through this voluntary communication, they were able to gain potential health benefits. These findings suggest the role of online groups in providing contexts in which to disclose about their distressful situation among those coping with serious health concerns.

There are limitations to this study. First, the observed associations of written disclosure with health outcomes do not justify causal claims. There may be other unmeasured confounders that account for the associations. There is a possibility that the association reflects a reverse causal relationship—functional well-being might bring upon disclosure of insights, for example, rather than the other way around. One reasonable way to address this limitation is to statistically control for potential third factors, and in this research, baseline scores of health outcomes and individual background characteristics (e.g., age, education, living status, stage of cancer) were controlled when we investigated the effects of disclosure on health outcomes after four months. Second, a limitation with the coding scheme of posted messages is worth noting. The computerized text analysis has a limitation in grasping the actual contexts in which particular words are used, for example, when positive emotional words are presented in a negative context. Nevertheless, we believe the validity of the coding is reasonable (Pennebaker & Francis, 1996; Pennebaker & Francis, 1999) especially when the number of coded messages is large. Lastly, the breast cancer concerns index used in this research had lower reliability than other measures, and caution is needed in interpreting its interaction terms (especially non significant effects) on health outcomes in a small sample of this research. The interaction effects need to be examined with a more reliable measure in future studies.

Acknowledgements

This publication was made possible by grants from the National Cancer Institute to the Centers of Excellence in Cancer Communication at University of Pennsylvania (P50-CA-095856-06) and at University of Wisconsin, Madison (P50 CA095817-06). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not represent the views of the National Cancer Institute. The authors thank Robert Hornik and Martin Fishbein for suggestions, and also thank Robert Hawkins, Fiona McTavish, Bret Shaw, Suzanne Pingree, and David Gustafson for sharing the unpublished data and Helene McDowell, Gina Landucci, and Haile Berhe for data collection and management.

Footnotes

The inter-rater reliability and external validity of LIWC word categories were supported (Pennebaker & Francis, 1996). The correlations between LIWC ratings and judges’ ratings were .77, .68, and .64, respectively for insight words, negative emotion words, and positive emotion words (Pennebaker, Mayne, & Francis, 1997).

The figure varied by the size of their family, e.g., for a single woman < $21,475 per year and family of four < $44,125 per year.

We preprocessed the set of online posts in order to exclude non-disclosive messages. Disclosive messages were broadly defined as any posts that refer to the self, including one’s experience, thoughts, and feelings. Under this broad definition, disclosive messages can be either descriptive or evaluative (Derlega et al., 1993) and it can be about either first-hand or second-hand experience (e.g., significant others’ experience). The following types of messages were excluded: messages posted as a part of the in-house training process, messages reporting technical problems with CHESS, and messages that were posted a second time right after the same message.

This criterion is comparable to that of previous research (e.g., Shaw et al., 2007).

The FACT-B is composed of the FACT-General (FACT-G) and the Breast Cancer Subscale, so that it can complement the general scale with items specific to breast cancer patients’ quality of life. For reports on its validity, reliability, and sensitivity to clinical change, see articles by Brady et al. (1997) and Cella, Tulsky, and Gray (1993).

LIWC2007 produces eighty output variables through text processing, including 4 general descriptor categories (e.g., total word count, words per sentence), 22 standard linguistic dimensions (e.g., percentage of words in the text that are pronouns, verbs, etc.), and 32 word categories tapping psychological constructs (e.g., affect, cognition, biological processes). For a complete list, see Pennebaker, Chung, Ireland, Gonzales, & Booth (2007)’s LIWC2007 manual.

The default LIWC2007 dictionary consists of about 4,500 words and word stems. The dictionary includes 195 insight words and 499 negative emotion words. For a full list of insight, negative emotion, and positive emotion words, refer to the LIWC program (www.liwc.net).

Perceived availability of social support was measured using six items (alpha = .87): e.g., There are people I could count on for emotional support; There are people I could rely on when I need help doing something; There are people who will help me find out the answers to my questions.

Participants may vary in the amount of use needed to achieve the health benefits they desire. The average usage time per given period predicted health outcomes better than the length of time using CHESS (Han et al., 2009).

There was one significant finding, but it was contrary to our hypothesis, such that writing a higher percentage of positive emotion words in disclosure was negatively associated with health self-efficacy at follow-up.

Disclosure of insights was also included in the model to show that emotional habituation is not a proper explanation for its benefits, whereas cognitive adaptation can explain the benefits (as supported in the previous section).

Contributor Information

Minsun Shim, Department of Speech Communication, University of Georgia.

Joseph N. Cappella, Annenberg School for Communication, University of Pennsylvania

Jeong Yeob Han, Department of Telecommunication, University of Georgia.

References

- Alpers GW, Winzelberg AJ, Classen C, Roberts H, Dev P, Koopman C, Taylor CB. Evaluation of computerized text analysis in an Internet breast cancer support group. Computers in Human Behavior. 2005;21:361–376. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura A. Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York: Freeman; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Berg JH, Archer RL. Disclosure or concern: A second look at liking for the norm-breaker. Journal of Personality. 1980;48:245–257. [Google Scholar]

- Brady M, Cella D, Mo F, Bonomi A, Tulsky D, Lloyd S, et al. Reliability and validity of the functional assessment of cancer therapy-breast quality-of-life instrument. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 1997;15:974–986. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.3.974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cella DF, Tulsky DS, Gray G. The functional assessment of cancer therapy scale: Development and validation of the general measure. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 1993;11:570–579. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.3.570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Cohen P, West SG, Aiken LS. Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences. 3rd ed. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell JD, Lam S, Stanton AL, Taylor SE, Bower JE, Sherman DK. Does self-affirmation, cognitive processing, or discovery of meaning explain cancer-related health benefits of expressive writing? Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2007;33:238–250. doi: 10.1177/0146167206294412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davison KP, Pennebaker JW. Virtual narratives: Illness representation in online support groups. In: Pertie KJ, Weinman JA, editors. Perceptions of Health and Illness: Current Research and Applications. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Overseas Publishers Association; 1997. pp. 463–486. [Google Scholar]

- Davison KP, Pennebaker JW, Dickerson SS. Who talks? The social psychology of illness support groups. American Psychologist. 2000;55:205–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derlega VJ, Metts S, Petronio S, Margulis ST. Self-disclosure. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Kozak M. Emotional processing of fear: Exposure to corrective information. Psychological Bulletin. 1986;99:20–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fogel J, Albert SM, Schnabel F, Ditkoff BA, Neugut AI. Internet use and social support in women with breast cancer. Health Psychology. 2002;21:398–404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisina PG, Borod JC, Lepore SJ. A meta-analysis of the effects of written emotional disclosure on the health outcomes of clinical populations. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2004;192:629–634. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000138317.30764.63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganz PA. Quality of life across the continuum of breast cancer care. Quality of Life Concerns. 2000;6:324–330. doi: 10.1046/j.1524-4741.2000.20042.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustafson D, McTavish F, Stengle W, Ballard D, Jones E, Julesberg K, McDowell H, Landucci G, Hawkins R. Reducing the digital divide for low-income women with breast cancer: A feasibility study of a population-based intervention. Journal of Health Communication. 2005a;10(Supplement 1):173–193. doi: 10.1080/10810730500263281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustafson D, McTavish F, Stengle W, Ballard D, Hawkins R, Shaw B, Jones E, Julesberg K, McDowell H, Chen WC, Volrathongchai K, Landucci G. Use and Impact of eHealth System by Low-income Women With Breast Cancer. Journal of Health Communication. 2005b;10(Supplement 1):195–218. doi: 10.1080/10810730500263257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han JY, Hawkins R, Shaw B, Pingree S, McTavish F, Gustafson D. Unraveling uses and effects of an interactive health communication system. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media. 2009;53:112–133. doi: 10.1080/08838150802643787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz . Stress response syndromes. 2nd Ed. Northvale, NJ: Jason Aronson; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Jourard SM. Self-disclosure: an experimental analysis of the transparent self. New York, NY: Wiley-Interscience; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- King LA, Miner KN. Writing about the perceived benefits of traumatic events: Implications for physical health. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2000;26:220–230. [Google Scholar]

- Kloss JD, Lisman SA. An exposure-based examination of the effects of written emotional disclosure. British Journal of Social Psychology. 2002;7:31–46. doi: 10.1348/135910702169349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lange A, Schoutrop M, Schrieken B, Van de Ven J-P. Interapy: A model for therapeutic writing through the Internet. In: Lepore SJ, Smyth JM, editors. The writing cure: How expressive writing promotes health and emotional well-being. Washington, DC, US: American Psychological Association; 2002. pp. 215–238. [Google Scholar]

- Lepore SJ. Expressive writing moderates the relation between intrusive thoughts and depressive symptoms. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1997;73:1030–1037. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.73.5.1030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lepore SJ, Greenberg MA. Mending broken hearts: Effects of expressive writing on mood, cognitive, processing, social adjustment, and health following a relationship breakup. Psychology and Health. 2002;17:547–560. [Google Scholar]

- Lepore SJ, Greenberg MA, Bruno M, Smyth JM. Expressive writing and health: Self-regulation of emotion-related experience, physiology, and behavior. In: Lepore SJ, Smyth JM, editors. The writing cure: How expressive writing promotes health and emotional well-being. Washington, DC, US: American Psychological Association; 2002. pp. 99–117. [Google Scholar]

- Lepore SJ, Smyth JM. The writing cure: An overview. In: Lepore SJ, Smyth JM, editors. The Writing Cure: How Expressive Writing Promotes Health and Emotional Well-being. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2002. pp. 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis D. Computer-based approaches to patient education: A review of the literature. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 1999;6:272–282. doi: 10.1136/jamia.1999.0060272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman MA. The role of insightful disclosure in outcomes for women in peer-directed breast cancer groups: a replication study. Psycho-Oncology. 2007;16:961–964. doi: 10.1002/pon.1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman MA, Goldstein BA. Self-help On-line: An Outcome Evaluation of Breast Cancer Bulletin Boards. Journal of Health Psychology. 2005;10:855–862. doi: 10.1177/1359105305057319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman MA, Goldstein BA. Not all negative emotions are equal: The role of emotional expression in online support groups for women with breast cancer. Psycho-oncology. 2006;15:160–168. doi: 10.1002/pon.932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray E, Segal D. Emotional processing in vocal and written expression of feelings about traumatic experiences. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1994;7:391–405. doi: 10.1007/BF02102784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen JE, Yarbrough EJ, Vaga A, Tucker D. Investigation of the effects of gender and preparation on quality of communication in Internet support groups. Computers in Human Behavior. 2003;19:259–275. [Google Scholar]

- Owen JE, Klapow JC, Roth DL, Tucker DC. Use of the Internet for information and support: Disclosure among persons with breast and prostate cancer. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2004;27:491–505. doi: 10.1023/b:jobm.0000047612.81370.f7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen JE, Klapow JC, Roth DL, Shuster JL, Bellis J, Meredith R, Tucker DC. Randomized pilot of a self-guided Internet coping group for women with early-stage breast cancer. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2005;30:54–64. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm3001_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennebaker JW. Confession, inhibition, and disease. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. 1989;22:211–244. [Google Scholar]

- Pennebaker JW. Opening up: The Healing Power of Expressing Emotions. New York: Guilford Press; 1997a. Revised version. [Google Scholar]

- Pennebaker JW. Writing about emotional experiences as a therapeutic process. Psychological Science. 1997b;8:162–166. [Google Scholar]

- Pennebaker JW, Beall S. Confronting a traumatic event: Toward an understanding of inhibition and disease. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1986;95:274–281. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.95.3.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennebaker JW, Chung CK, Ireland M, Gonzales A, Booth R. The Development and Psychometric Properties of LIWC2007. 2007 Retrieved January 2008, from http://www.liwc.net/index.php.

- Pennebaker JW, Francis ME. Cognitive, emotional, and language processes in disclosure. Cognition and Emotion. 1996;10:601–626. [Google Scholar]

- Pennebaker JW, Mayne TJ, Francis ME. Linguistic predictors of adaptive bereavement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1997;72:863–871. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.72.4.863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennebaker JW, Seagel JD. Forming a story: The health benefits of narrative. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 1999;55:1243–1254. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4679(199910)55:10<1243::AID-JCLP6>3.0.CO;2-N. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, and Computers. 2004;36:717–731. doi: 10.3758/bf03206553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods. 2008a;40:879–891. doi: 10.3758/brm.40.3.879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Hayes AF. Contemporary approaches to assessing mediation in communication research. In: Hayes AF, Slater MD, Snyder LB, editors. Advanced Data Analysis Methods for Communication Research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2008b. pp. 13–54. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg HJ, Rosenberg SD, Ernstoff MS, Wolford GL, Amdur RJ, Elshamy MR, Bauer-Wu SM, Ahles TA, Pennebaker JW. Expressive disclosure and health outcomes in a prostate cancer population. The International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine. 2002;32:37–53. doi: 10.2190/AGPF-VB1G-U82E-AE8C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlenker BR, Dlugolecki DW, Doherty K. The impact of self-presentations on self-appraisals and behavior: The power of public commitment. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1994;20:20–33. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw BR, Han JY, Kim E, Gustafson D, Hawkins R, Cleary J, McTavish F, Pingree S, Eliasonm P, Lumpkins C. Effects of prayer and religious expression within computer support groups on women with breast cancer. Psycho-Oncology. 2007;16:676–687. doi: 10.1002/pon.1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw BR, Hawkins RP, McTavish F, Pingree S, Gustafson DH. Effects of insightful disclosure within computer mediated support groups on women with breast cancer. Health Communication. 2006;19:133–142. doi: 10.1207/s15327027hc1902_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sloan DM, Marx BP. Taking pen to hand: Evaluating theories underlying the written disclosure paradigm. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2004a;11:121–137. [Google Scholar]

- Sloan DM, Marx BP. A closer examination of the structured written disclosure procedure. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2004b;72:165–175. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.2.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyth JM. Written emotional expression: Effect sizes, outcome types, and moderating variables. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66:174–184. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.1.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyth JM, Pennebaker JW. What are the health effects of disclosure? In: Baum A, Revenson TA, Singer JE, editors. Handbook of Health Psychology. Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc; 2001. pp. 339–348. [Google Scholar]

- Smyth JM, True N, Souto J. Effects of writing about traumatic experiences: The necessity for narrative structuring. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2001;20:161–172. [Google Scholar]

- Spiegel D. Psychosocial aspects of breast cancer treatment. Seminars in Oncology. 1997;24:36–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanton AL, Danoff-Burg S. Emotional expression, expressive writing, and cancer. In: Lepore SJ, Smyth JM, editors. The Writing Cure: How Expressive Writing Promotes Health and Emotional Well-being. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2002. pp. 31–51. [Google Scholar]

- Stanton AL, Danoff-Burg S, Cameron CL, Bishop M, Collins CA, Kirk SB, Sworowski LA. Emotionally expressive coping predicts psychological and physical adjustment to breast cancer. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:875–882. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanton AL, Danoff-Burg S, Sworowski LA, Collins CA, Branstetter AD, Rodriguez-Hanley A, et al. Randomized, controlled trial of written emotional expression and benefit finding in breast cancer patients. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2002;20:4160–4168. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.08.521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winzelberg A. The analysis of an electronic support group for individuals with eating disorders. Computers in Human Behavior. 1997;13:393–407. [Google Scholar]