Abstract

Background

The success of antiretroviral therapy (ART) for treating HIV infection is now being turned toward HIV prevention. The Swiss Federal Commission for HIV/AIDS has declared that HIV positive persons who are treated with ART, have an undetectable viral load, and are free of co-occurring sexually transmitted infections (STI) should be considered non-infectious for sexual transmission of HIV. This study examined the implications of these assumptions in a sample of HIV positive individuals who drink alcohol.

Methods

People living with HIV/AIDS (N = 228) were recruited through community sampling and completed confidential computerized interviews, monthly unannounced pill counts for ART adherence, and HIV viral load obtained from medical records.

Results

One hundred eighty five HIV positive drinkers were currently receiving ART and 43 were untreated. Among those receiving ART, one in three were not viral suppressed and one in five had recently been diagnosed with an STI. Adherence was generally suboptimal, including among those assumed less infectious. As many as one in four participants reported engaging in unprotected intercourse with an HIV uninfected partner in the past 4-months. There were few associations between assumed infectiousness and sexual practices.

Conclusions

Less than half of people who drink alcohol and take ART met the Swiss criteria for non-infectiousness. Poor adherence and prevalent STI threaten the long-term potential of using ART for prevention. In the absence of behavioral interventions, the realities of substance use and other barriers place doubt on the use of ART as prevention among alcohol drinkers.

Introduction

Research with untreated HIV serodiscordant couples has shown that sexual transmission of HIV is significantly less likely to occur when HIV is undetectable in peripheral blood plasma. [1, 2] Antiretroviral therapies (ART) effectively suppress HIV replication and have improved the health of people living with HIV/AIDS. Most ART regimens penetrate the genital compartment of the immune system and potentially reduce sexual infectiousness. [3–6] Accumulating evidence for the HIV prevention benefits of ART brought the Swiss Federal Commission for HIV/AIDS to declare that HIV infected persons should be considered non-infectious when peripheral blood plasma viral load is undetectable for at least 6 months and there are no co-occurring sexually transmitted infections (STI). The so called ‘Swiss Statement’ draws directly from studies of men showing that viral load in semen is suppressed and concordant with viral load in blood plasma when assumptions of treatment adherence, viral load and co-occurring STI are met. [7]

The Swiss Statement is now supported by the results of the HIV Prevention Trials Network (HPTN) randomized clinical trial 052, which demonstrated a 96% reduction in HIV transmission following early initiation of ART compared to delayed ART. [8] Early treatment also resulted in improved health for the HIV infected partner. The World Health Organization (WHO) now recommends ART for HIV positive sex partners in HIV serodiscordant couples with less than 350 CD4 cells/cc3 to reduce HIV transmission. The WHO’s position on HIV treatment as prevention is part of a more general movement calling for all HIV infected partners in serodiscordant couples with CD4 cell counts between 500 and 350 cells/cc3 to qualify for ART as a means of curbing HIV transmission.

There are, however, several reasons to question the promise of ART for HIV prevention in real word settings. First, evidence garnered from prospective treatment cohorts, such as the Swiss Cohort Study, and randomized trials including HPTN 052, is contaminated by the intensive attention and clinical care provided to research participants that are rarely achieved in practice. Participants in these studies are carefully monitored for adherence, counseled to use condoms, and routinely tested and treated for co-occurring STI. Selecting serodiscordant couples for research may also introduce biases toward more stable and monogamous relationships that can reduce the risks for co-occurring STI. It is noteworthy that 11 of the 39 HIV infections observed in HPTN 052 were not genetically linked to the sex partner enrolled in the trial.

The assumptions underlying the Swiss Statement are often not realized in the lives of people with HIV/AIDS. Particularly important is the inference that sexual infectiousness mirrors blood plasma infectiousness. A review of 19 studies that investigated the concordance between blood plasma viral load and semen viral load found an average correlation of .44. [9] Thus, as little as 16% of the variance in sexual infectiousness can be discerned from knowing one’s blood plasma viral load. One likely factor in the discordance between blood plasma and semen viral load is co-occurring STI because local inflammation spikes viral shedding in the genital tract. A review of 37 studies found a 12% median point-prevalence of confirmed STI in people living with HIV/AIDS, and the most common STI in people living with HIV were those that cause HIV shedding, specifically Syphilis (median 9.5% prevalence), gonorrhea (9.5%), Chlamydia (5%), and Trichamoniasis (18.8%) [10]. Factors that impede ART adherence and increase risks for STI will therefore undermine the use of ART as HIV prevention. Alcohol is among the most reliable impediments to ART adherence [11, 12] and among the most robust predictors of STI in people living with HIV/AIDS. [13] Alcohol use may therefore pose a particularly significant challenge to employing ART to prevent the spread of HIV.

In the current study, we tested the association between HIV treatment status and HIV transmission risk behaviors in a sample of HIV positive drinkers. Based on previous research of risk compensation in response to HIV treatment [14, 15], we hypothesized that individuals receiving ART would demonstrate higher rates of HIV transmission risk behaviors compared to their untreated counterparts. In a second series of analyses focused on individuals receiving ART, we examined risk behaviors for persons meeting the Swiss Statement criteria for non-infectiousness. We hypothesized that persons who met the Swiss Statement assumptions for non-infectiousness would engage in more unprotected sex behaviors with HIV uninfected partners, potentially offsetting the protective benefits of reduced infectiousness.

Methods

Participants and Recruitment

People living with HIV/AIDS (N = 228) were recruited through community-based strategies that included both targeted clinic recruitment and snowball sampling techniques. Recruitment relied on responses to brochures placed in waiting rooms of AIDS service providers and infectious disease clinics throughout Atlanta, GA as well as an explicit systematic approach to word-of-mouth chain recruitment to extend our sampling. The study entry criteria were (a) 18 years of age or older, (b) HIV positive, and (c) drank any alcohol in the past week.

Measures

Data were collected through three sources; audio-computer assisted structured interviews (ACASI) [16, 17], monthly unannounced pill counts to monitor ART adherence, and chart abstracted viral load and CD4 counts.

Computerized Interviews

Demographic and health characteristics

Participants were asked their gender, sexual orientation, age, years of education, income, ethnicity, and employment status. We also asked participants about their histories of incarceration and substance abuse treatment. Participants self-reported whether they knew their most recent viral load test results and if so whether the result was detectable or undetectable.

Alcohol use

To assess global alcohol use we administered the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT), a 10-item scale designed to measure alcohol consumption and identify risks for alcohol abuse and dependence. [18] The first three items of the AUDIT represent quantity and frequency of alcohol use and the remaining seven items concern problems incurred from drinking alcohol. Scores of greater than 8 indicate high-risk for alcohol use disorders and problem drinking, with demonstrated specificities between .80 and .90.[19] In the current sample, the AUDIT was internally consistent, alpha = .90.

STI Diagnoses

Participants reported whether they had been diagnosed with gonorrhea, Chlamydia, Syphilis, genital herpes (HSV), or Trichomoniasis. Participants who had been diagnosed with an STI were asked the approximate date of their last diagnosis. We used these dates to determine if the diagnosis had occurred within the previous 12 months of the assessment session. We used the same format to assess the occurrence of unexplained genital discharge to detect potentially undiagnosed STI symptoms. We did not, however, include non-specific symptoms in our definition of having contracted an STI.

Sexual risk and protective behaviors

Participants reported vaginal and anal intercourse with and without condoms for HIV seroconcordant and serodiscordant partnerships in the previous 4-months. [20] Participants were instructed to think back over the past 4-months and estimate the number of sex partners and number of sexual occasions in which they practiced each behavior. Data were analyzed within HIV serodiscordant relationships with individual behaviors examined as well as behaviors collapsed across unprotected and protected aggregates. In addition, we calculated the percentage of intercourse occasions in which condoms were used by taking the ratio [condom protected vaginal + condom protected anal intercourse/total vaginal + total anal intercourse].

Unannounced Pill Count Medication Adherence

Participants consented to monthly-unannounced telephone-based pill counts for the duration of the study, constituting a prospective objective measure of adherence. Unannounced pill counts are reliable and valid in assessing medication adherence when conducted in participants’ homes [21] and on the telephone [22, 23]. In this study we conducted unannounced cell-phone based pill counts. Participants were provided with a free cell phone that restricted service for project contacts and emergency use (e.g., 911). Following an in-office training in the pill counting procedure, participants were called at unscheduled times by a phone assessor. Pill counts occurred over 21 to 35 day intervals and were conducted for each of the antiretroviral medications participants were taking. Pharmacy information from pill bottles was also collected to verify the number of pills dispensed between calls. Adherence was calculated as the ratio of pills counted relative to pills prescribed, taking into account the number of pills dispensed.

Chart Abstracted Viral Load and CD4 Cell Counts

We used a participant assisted method for collecting chart abstracted viral load and CD4 cell counts from medical records. Participants were given a form that requested their doctor’s office to provide results and dates of their most recent viral load and CD4 cell counts. These data were therefore obtained directly by the participants from their primary HIV care providers. The form included a place for the provider’s office stamp or signature to assure data authenticity. Participants collected their chart-abstracted data prior to the initial assessment and again at the end of the study, proximal to the final assessment.

Procedures

Following written informed consent participants completed the baseline ACASI assessment, which required approximately 45 min. Participants were then provided with a study cell phone and instructed in its use. We trained participants in the steps required to compete the monthly-unannounced pill counts. Viral load and CD4 cell counts were collected at the start and end of the one-year study. The ACASI was repeated at the 12-month follow-up. Participants were provided with US$20 cash reimbursements for each study activity completed. Data were collected between November 30, 2009 and June 29, 2011. The study was approved by the university Institutional Review Board.

Data Analyses

Two series of analyses were performed to examine the associations between (a) receiving ART and sexual behavior and (b) meeting the Swiss Statement criteria for non-infectiousness and sexual behavior. To address the first question, participants who were being treated with ART were compared to those who were currently not treated. The second set of analyses focused only on those who were receiving ART. We partitioned participants into higher and lower infectiousness groups on the basis of the Swiss Statement criteria. Specifically, participants who either had been diagnosed with an STI during the one-year follow-up period or who were not viral suppressed at either time point obtained from medical records were defined as not meeting the Swiss criteria, or assumed more highly infectious. Participants who were both not diagnosed with an STI and were viral suppressed at baseline and the follow-up were defined as meeting Swiss criteria for non-infectiousness. We used 200 HIV RNA copies per unit of blood plasma to define undetectable viral loads. All analyses were conducted using logistic regression models to obtain odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals.

Results

The total sample included 178 men and 50 women living with HIV/AIDS who were currently drinking alcohol; 55% reported drinking less than once a week, 16% drank 2 to 3 times a week, and 6% drank at least 4 times a week. Forty-three percent of participants reported drinking 1 to 2 drinks during typical drinking days, 22% 3–4 drinks, and 12% 5 or more drinks. A total of 32% of participants had received substance use treatment in their lifetime, with 14% treated for substance use in the past year.

Receiving ART and Sexual Behavior

One hundred eighty five participants were currently receiving ART and 43 were currently untreated. Table 1 shows the demographic and health characteristics of untreated and treated participants. Receiving ART was only associated with less likelihood of having been incarcerated in the previous year. As expected, treatment was associated with having an undetectable viral load at the start and completion of the study. Participants receiving ART were more likely to have been diagnosed with an STI in the past year, although this association only approached significance. In addition, receiving ART was associated with a greater likelihood of having HIV negative and unknown HIV status partners. (see Table 2) This association was significant at Time 1 and was a statistical trend at Time 2. Importantly, treatment status was not significantly associated with engaging in unprotected intercourse with HIV negative partners.

Table 1.

Demographic and health characteristics of HIV positive drinkers who were not receiving ART and those receiving ART.

| Not Receiving ART (N = 43) |

Receiving ART (N = 185) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | OR | 95%CI | |

| Men | 34 | 79 | 144 | 78 | ||

| Women | 9 | 21 | 41 | 22 | 1.07 | 0.47–2.42 |

| Gay identified | 20 | 4 | 103 | 56 | 0.85 | 0.58–1.24 |

| Married | 9 | 21 | 43 | 23 | 1.11 | 0.49–2.50 |

| African-American | 36 | 88 | 172 | 93 | 1.74 | 0.58–5.17 |

| Income < $10,000 | 31 | 72 | 109 | 59 | 1.80 | 0.87–3.73 |

| Employed | 27 | 63 | 139 | 75 | 1.79 | 0.88–3.61 |

| Incarcerateda | 12 | 28 | 23 | 12 | 0.36* | 0.16–0.81 |

| Drug use | 25 | 58 | 104 | 56 | 0.60 | 0.21–1.68 |

| Drug Treatmenta | 8 | 18 | 23 | 12 | 0.92 | 047–1.81 |

| STI diagnosis past year | 5 | 12 | 44 | 24 | 2.37+ | 0.88–6.39 |

| Undetectable Viral load | ||||||

| Time 1 | 14 | 33 | 140 | 76 | 0.15** | 0.07–0.32 |

| Time 2 | 5 | 23 | 141 | 85 | 0.05** | 0.02–0.15 |

| CD4 count > 200 | ||||||

| Time 1 | 27 | 71 | 145 | 80 | 1.64 | 0.74–3.61 |

| Time 2 | 18 | 86 | 143 | 87 | 1.13 | 0.30–4.18 |

|

|

||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | |||

|

|

||||||

| Age | 44.2 | 8.9 | 45.1 | 7.3 | 1.01 | 0.97–1.06 |

| Education | 12.5 | 1.4 | 12.6 | 1.4 | 1.04 | 0.82–1.31 |

| AUDIT Score | 6.7 | 6.2 | 5.5 | 5.8 | 0.96 | .091–1.01 |

Note:

reported for the past year;

p < .01

p < .05

p < .10

Table 2.

Sexual behaviors reported in the previous 4-months among HIV positive drinkers who were not receiving ART and those receiving ART.

| Not Receiving ART (N = 43) |

Receiving ART (N = 185) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Behaviors | N | % | N | % | OR | 95%CI |

| Time 1 | ||||||

| Sex partners 0 | 16 | 37 | 55 | 30 | Reference | |

| 1 | 15 | 35 | 76 | 41 | 0.92 | 0.33–2.52 |

| 2 | 5 | 12 | 28 | 15 | 1.36 | 0.50–3.71 |

| 3+ | 7 | 16 | 26 | 14 | 1.51 | 0.42–5.34 |

| HIV Negative partnersa | 7 | 26 | 63 | 49 | 2.68* | 1.06–6.78 |

| Unprotected sex with HIV negative partnersa | 7 | 26 | 37 | 29 | 1.13 | 0.44–2.91 |

|

|

||||||

| Time 2

|

||||||

| Sex partners 0 | 25 | 58 | 73 | 39 | Reference | |

| 1 | 12 | 28 | 69 | 37 | 0.48 | 0.15–1.54 |

| 2 | 2 | 5 | 19 | 10 | 0.95 | 0.28–3.25 |

| 3+ | 4 | 10 | 24 | 13 | 1.58 | 0.26–9.58 |

| HIV Negative partnersb | 8 | 44 | 58 | 52 | 3.03+ | 0.94–9.78 |

| Unprotected sex with HIV negative partnersb | 2 | 11 | 28 | 25 | 1.52 | 0.46–4.97 |

Sexually active participants at Time 1, Not Receiving ART N = 27, Receiving ART N =130;

Sexually active participants at Time 2, Not Receiving ART N = 18, Receiving ART N =112

Note

p < .05

p < .10

Swiss Criteria for Non-Infectiousness

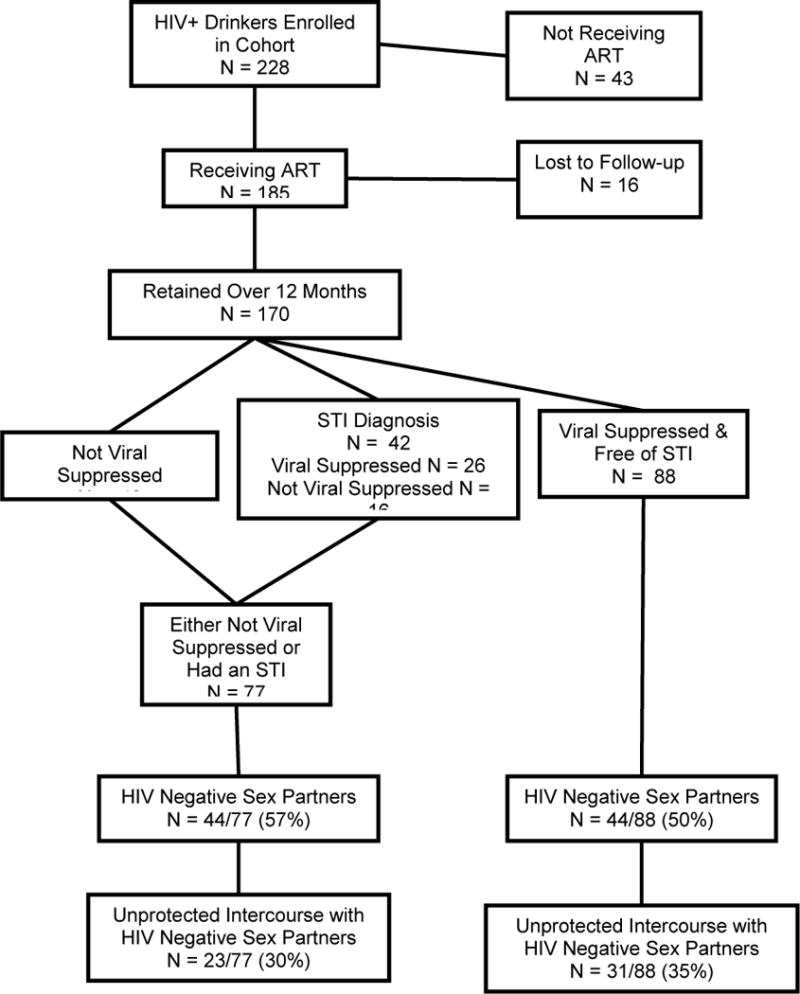

Figure 1 shows the sample breakdown with respect to ART status, viral suppression and STI diagnoses. Among the 228 participants enrolled in the cohort, 43 (18%) were not receiving HIV treatment. The 12-month retention for the remaining 185 ART treated participants was 91% (n = 170). Among those retained over the year, 67% (n=114) had undetectable chart abstracted viral loads at both baseline and 12-month follow-up, whereas 33% (n=56) had detectable virus at either Time 1 or Time 2. In addition, 26 participants who were viral suppressed had been diagnosed with an STI over the 12-month follow-up. Thus, 88 (51%) participants were viral suppressed and STI free, meeting the Swiss Statement criteria for non-infectiousness, defined as lower infectious. The remaining 82 (49%) participants did not meet the Swiss Statement criteria for non-infectiousness and were defined as being higher infectious; 42 had an STI during the 12-months follow-up, 56 were not viral suppressed and 16 were not viral suppressed and had been diagnosed with an STI. The most common STI diagnoses over the 12-months follow-up were genital herpes, Syphilis, and gonorrhea. Among those diagnosed with an STI, 16 had multiple STI diagnoses during the follow-up period. (see Table 3)

Figure 1.

Flow chart for participants receiving HIV treatment, viral suppression and sexually transmitted co-infections.

Table 3.

Demographic and health characteristics among participants defined as higher and lower infectious.

| Higher Infectious (n = 82) |

Lower Infectious (n = 88) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | OR | 95%CI | |||

| Men | 58 | 75 | 68 | 77 | ||||

| Women | 19 | 25 | 20 | 23 | 0.89 | 0.43–1.84 | ||

| Gay identified | 38 | 49 | 53 | 60 | 0.85 | 0.59–1.21 | ||

| Married | 13 | 17 | 29 | 33 | 2.24* | 1.15–5.09 | ||

| African-American | 68 | 88 | 84 | 95 | 2.77 | 0.82–9.41 | ||

| Income <$10,000 | 46 | 60 | 49 | 56 | 1.18 | 0.63–2.19 | ||

| Unemployed | 22 | 30 | 19 | 22 | 1.54 | 0.76–3.12 | ||

| Incarcerateda | 8 | 10 | 10 | 11 | 1.10 | 0.41–2.96 | ||

| Dug use | 46 | 60 | 48 | 55 | 0.80 | 0.43–1.50 | ||

| Drug treatmenta | 8 | 30 | 11 | 29 | ||||

| Previous Year STIs | ||||||||

| Gonorrhea | 11 | 14 | ||||||

| Chlamydia | 6 | 8 | ||||||

| Syphilis | 12 | 16 | ||||||

| Genital herpes (HSV) | 14 | 18 | ||||||

| Trichomoniasis | 4 | 5 | ||||||

| Genital discharge | 8 | 10 | ||||||

| 1 STI diagnosis | 26 | 34 | ||||||

| 2 STI diagnoses | 12 | 16 | ||||||

| 3+ STI diagnoses | 4 | 5 | ||||||

| Any STI Diagnosis | 42 | 55 | ||||||

| CD4 count > 200 | ||||||||

| Time 1 | 54 | 72 | 77 | 90 | 3.32** | 1.41–7.82 | ||

| Time 2 | 54 | 75 | 84 | 97 | 9.33** | 2.62–33.20 | ||

| Chart Abstracted Undetectable Viral load | ||||||||

| Time 1 | 41 | 53 | 88 | 100 | n/a | |||

| Time 2 | 45 | 62 | 88 | 100 | n/a | |||

| Self-report undetectable viral load | ||||||||

| Time 1 | 40 | 52 | 68 | 77 | 1.43 | 0.82–2.49 | ||

| Discrepant with chart | 25 | 32 | 20 | 23 | ||||

| Time 2 | 45 | 63 | 77 | 89 | 3.06** | 1.42–6.57 | ||

| Discrepant with chart | 14 | 20 | 10 | 12 | ||||

|

|

||||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | |||||

|

|

||||||||

| Age | 44.2 | 7.3 | 46.2 | 7.0 | 1.04 | 0.99–1.08 | ||

| Education | 12.4 | 1.4 | 12.7 | 1.4 | 1.15 | 0.93–1.43 | ||

| AUDIT Score | 5.7 | 5.4 | 5.2 | 5.5 | 0.93 | 0.92–1.04 | ||

Note

p < .01

p < .05

With respect to demographics, participants defined as lower infectious were significantly more likely to be married. As expected, lower infectiousness was associated with greater likelihood of a higher CD4 cell count at both time points. There were no other differences between groups for demographic, health, or substance use characteristics. With respect to viral load awareness, participants in both infectiousness groups were not always aware of their viral load and it was common for self-reported viral load to be discrepant from the viral load abstracted from medical records. More than one in four participants at Time 1 reported having a viral load that was discrepant with their most recent medical records viral load. However, at Time 2 significantly more lower infectious participants reported having an undetectable viral load than did the higher infectiousness group and the number of discrepant self-reported and chart abstracted viral loads was less than observed at Time 1.

Infectiousness and ART Adherence

Adherence monitored by unannounced pill counts for the two infectiousness groups is shown in Table 4. Overall, participants, defined as higher infectious demonstrated poorer ART adherence than those in the lower infectious group. Nearly half of higher infectious participants were less than 85% adherent. During the typical month, the average adherence for higher infectious participants was below 80% of pills taken. However, adherence among the lower infectious group was uneven over the year of observation, with more than one in four participants failing to achieve 85% of pills taken each month.

Table 4.

Monthly unannounced pill count ART adherence among participants defined as higher and lower infectious.

| Higher Infectious (n = 82) < 85% Adherent |

Lower Infectious (n = 88) < 85% Adherent |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time | M | SD | N | % | M | SD | N | % | OR | 95%CI |

| 1 | 81.3 | 19.3 | 37 | 51 | 88.6 | 16.8 | 21 | 24 | 10.46** | 1.51–72.2 |

| 2 | 84.4 | 22.3 | 26 | 35 | 85.4 | 20.1 | 25 | 29 | 1.55 | 0.35–6.76 |

| 3 | 79.1 | 26.8 | 28 | 39 | 86.9 | 16.5 | 27 | 32 | 5.18* | 1.12–23.86 |

| 4 | 77.7 | 27.1 | 28 | 41 | 87.9 | 15.7 | 24 | 29 | 9.55** | 1.82–49.80 |

| 5 | 76.6 | 25.9 | 28 | 40 | 87.7 | 19.1 | 22 | 27 | 6.48* | 1.35–30.9 |

| 6 | 79.3 | 27.6 | 26 | 39 | 86.5 | 18.0 | 23 | 27 | 4.11+ | 0.93–18.16 |

| 7 | 81.7 | 23.9 | 24 | 36 | 85.6 | 17.9 | 28 | 32 | 2.51 | 0.53–11.86 |

| 8 | 80.6 | 25.5 | 24 | 35 | 84.1 | 21.9 | 27 | 31 | 1.86 | 0.48–7.15 |

| 9 | 77.2 | 30.7 | 28 | 41 | 85.3 | 18.5 | 27 | 31 | 3.83* | 1.01–14.48 |

| 10 | 70.5 | 33.8 | 34 | 50 | 87.9 | 17.0 | 23 | 26 | 15.38** | 3.43–68.99 |

| 11 | 80.7 | 24.4 | 33 | 47 | 87.6 | 13.9 | 29 | 33 | 8.28* | 1.27–53.65 |

| 12 | 77.9 | 26.7 | 36 | 52 | 86.3 | 16.5 | 32 | 36 | 6.52* | 1.25–33.84 |

| Aggregated over 12 months | ||||||||||

| 78.8 | 0.20 | 37 | 49 | 86.3 | 12.4 | 28 | 32 | 18.30** | 2.29–146.41 | |

Note

p < .01

p < .05

p < .10

Infectiousness and Sexual Behaviors

The majority of participants were currently sexually active at Times 1 and 2. As shown in Table 5, it was common for participants to report more than one sex partner in the previous 4-months at both time points. In addition, nearly half of participants reported HIV negative or unknown HIV status sex partners during those time periods, with as many as half of those with uninfected partners indicating unprotected anal or vaginal intercourse. Between 30% and 60% of intercourse occasions with HIV uninfected sex partners were not protected by condoms. The only significant difference between assumed infectiousness groups was for condom use with uninfected partners at Time 1; lower infectious participants reported less condom use with uninfected partners.

Table 5.

Sexual behaviors at Time 1 and Time 2 among participants defined as higher and lower infectious.

| Higher Infectious (n = 82) |

Lower Infectious (n = 88) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | OR | 95%CI | |

| Time 1 | ||||||

| Sex partners 0 | 21 | 27 | 25 | 28 | Reference | |

| 1 | 27 | 35 | 43 | 49 | 1.51 | 0.56–4.03 |

| 2 | 15 | 20 | 9 | 10 | 2.02 | 0.80–5.11 |

| 3+ | 14 | 18 | 11 | 12 | 0.76 | 0.24–2.39 |

| HIV- partners | 29 | 52 | 30 | 48 | 0.94 | 0.49–2.10 |

| Unprotected sex with HIV- partners | 14 | 25 | 24 | 38 | 1.84 | 0.83–4.06 |

| % Condoms with HIV- partners (M, SD) | 64.4 | 39 | 41.7 | 42.2 | 0.25* | 0.06–0.88 |

| Time 2 | ||||||

| Sex partners 0 | 27 | 35 | 25 | 28 | Reference | |

| 1 | 26 | 34 | 43 | 49 | 0.78 | 0.29–2.06 |

| 2 | 13 | 17 | 7 | 8 | 1.39 | 0.55–3.57 |

| 3+ | 11 | 14 | 13 | 15 | 0.45 | 0.13–1.54 |

| HIV- partners | 24 | 43 | 31 | 49 | 1.29 | 0.62–2.66 |

| Unprotected sex with HIV- partners | 12 | 21 | 13 | 21 | 0.95 | 0.39–2.30 |

| % Condoms with HIV- partners (M, SD) | 64.8 | 41.7 | 74.4 | 33.9 | 1.67 | 0.41–6.80 |

Note; p < .05

Discussion

The current study of HIV positive alcohol drinkers found few differences between those receiving and not receiving ART. Overall, individuals receiving ART were more likely to report sexual partners who were not HIV positive. However, there were no differences in their likelihood to engage in unprotected intercourse with those partners. Among persons receiving ART, one in three were not viral suppressed and one in five had been diagnosed with an STI during the study. In addition, 22% of participants who were viral suppressed during the study had been diagnosed with an STI, increasing their likelihood of sexual infectiousness regardless of having an undetectable viral load in their blood plasma. Poor adherence was observed in nearly one-third of those defined as less infectious, calling into question their assumed infectiousness over time.

Findings from the current study indicate that as many as one in three people living with HIV who drink alcohol and are taking ART engage in unprotected anal or vaginal intercourse with HIV uninfected sex partners. Rates of serodiscordant unprotected sex were similar for persons defined as lower and higher infectious. Thus, suboptimal adherence, multiple sex partners, and inconsistent condom use were common in this cohort of HIV positive alcohol drinkers, suggesting high-risk for increased infectiousness over time. Alcohol-related problems did not differentiate groups, suggesting that lighter and heavier drinkers may not differ in their meeting the assumptions of infectiousness. Research with larger samples of heavy drinkers is needed to confirm these associations. These findings highlight the limitations of applying the Swiss Statement for non-infectiousness to HIV positive drinkers, and perhaps others, receiving ART. Because alcohol use is common among people living with HIV/AIDS [13] and alcohol use is prevalent in developing countries [24], the cautions raised by the current findings may have broad implications for the use of HIV treatment with ART as prevention.

The Swiss Statement unambiguously specifies the circumstances under which a person with HIV should be considered non-infectious. Unfortunately, these conditions do not reflect the realities of many individuals living with HIV/AIDS. The Swiss Statement advises providers to inform their patents that it is no longer necessary to worry about infecting others with HIV when the conditions of non-infectiousness are met. The Statement emphasizes the potential ‘liberating effect’ on patients who are told they are no longer infectious, and the importance of sensitizing patients to the symptoms of STI. However, the majority of empirical support for the Swiss Statement comes from research with heterosexual couples in southern Africa [25, 26], which may not apply equally to men who have sex with men who practice anal intercourse. The HIV transmission dynamics of anal sex differ from vaginal sex in relation to infectivity. Unfortunately, there is also a wide gap between the applicability of these recommendations and what we know about HIV positive persons who drink. Drinkers may be less likely to follow through with medical recommendations and have less diligence in their health care. Further complicating matters is that individuals who believe they are less infectious because they are receiving ART may relax their use of condoms and actually be at greater risk for co-occurring STI. Research from the Swiss Cohort Study supports these concerns, finding that after the publication of the Swiss Statement HIV positive persons were more likely to report unprotected sex with stable sex partners if they were treated with ART and their HIV was suppressed. [27] The conditions of the Swiss Statement should therefore be considered an ideal that will remain difficult to achieve in the context of substance use, mental health problems, poverty, and other significant barriers to adherence and facilitators of contracting STI.

These findings should be interpreted in light of the study limitations. First, the sample was one of convenience and cannot be considered representative of people living with HIV infection. We recruited from multiple clinical services as well as through participant referrals. We cannot therefore know the range of care and clinical services that participants were receiving. In addition, participants were taking a variety of ART combinations and for variable lengths of time. The study also relied on self-report instruments to assess sexual behaviors, substance use, and other participant characteristics. While each of these measures was collected using state of the science procedures, they may still be subject to biases. Self-reported viral load results were often discrepant with medical records, offering a sense for the limitations of self-reported data in general. Socially sensitive behaviors such as sex and substance use assessed by self-report may be underreported, suggesting that rates of risk practices in this study should be considered lower-bound estimates, with actual risks possibly even higher. Another limitation of our study was our definition of non-adherence applied to all medication regimens, which differ in their demand for optimal adherence. [28–30] With these limitations in mind, we believe that the current study results have important implications for efforts to use ART to reduce HIV transmission risks.

The remarkable success of HIV treatments for improving the health and well-being of people living with HIV/AIDS is being extended to preventing new HIV infections. Using ART as prevention is successful in the context of perinatal transmission and stands to reason when applied to sexual transmission risks. However, poor concordance between blood plasma and genital tract viral loads casts a cautious light on the optimism behind using ART as prevention. These doubts are amplified for alcohol drinkers. Alcohol use is a double threat to the efficacy of ART as prevention by impeding treatment adherence and increasing risks for co-occurring STI. Scaling up ART as prevention therefore requires attention to behavior at a similar magnitude given to participants in research cohorts and trials that have deemed the strategy effective. Under-resourcing substance use treatment, routine medical care, and behavioral counseling will undermine the potential for HIV treatment with ART to prevent HIV infections.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by an America Reinvestment and Recovery Act (ARRA) Challenge Grant from the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA) RC1AA018983.

References

- 1.Wawer MJ, et al. Rates of HIV-1 tranmission per coital act, by stage of HIV-1 infection, in Rakai, Uganda. J Infect Dis. 2005;191(9):1403–1409. doi: 10.1086/429411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pinkerton SD. Probability of HIV transmission during acute infection in Rakai, Uganda. AIDS Behav. 2008;12(5):677–84. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9329-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vernazza P, et al. HIV transmission under highly active antiretroviral therapy. Lancet. 2008;372(9652):1806–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61753-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vernazza PL, et al. Effect of antiviral treatment on the shedding of HIV-1 in semen. AIDS. 1997;11:1249–1254. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199710000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kashuba AD, et al. Antiretroviral-drug concentrations in semen: implications for sexual transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43(8):1817–26. doi: 10.1128/aac.43.8.1817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vernazza PL, et al. Potent antiretroviral treatment of HIVinfection results in suppression of the seminal shedding of HIV. AIDS. 2000;14(2):117–121. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200001280-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vernazza P, Hirschel B, Bernasconi E, Flepp M. HIV-positive individuals without additional sexually transmitted diseases (STD) and on effective antiretroviral therapy are sexually non-infectious. Bulletin des médecins suisses. 2008;89(5) [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cohen MS, et al. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(6):493–505. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kalichman SC, DiBerto G, Eaton L. HIV Viral Load in Blood Plasma and Semen: Review and Implications of Empirical Findings. Sex Transm Dis. 2008;35:55–60. doi: 10.1097/olq.0b013e318141fe9b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kalichman SC, Pellowski J, Turner C. Prevalence of sexually transmitted co-infections in people living with HIV/AIDS: systematic review with implications for using HIV treatments for prevention. Sex Transm Infect. 2011;87:183–90. doi: 10.1136/sti.2010.047514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nakimuli-Mpungu E, et al. Depression, Alcohol Use and Adherence to Antiretroviral Therapy in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Systematic Review. AIDS Behav. 2011 doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0087-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hendershot CS, et al. Alcohol use and antiretroviral adherence: review and meta-analysis. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2009;52(2):180–202. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181b18b6e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shuper PA, et al. Alcohol as a correlate of unprotected sexual behavior among people living with HIV/AIDS: review and meta-analysis. AIDS Behav. 2009;13(6):1021–36. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9589-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Crepaz N, Hart TA, Marks G. Highly active antiretroviral therapy and sexual risk behavior: a meta-analytic review. JAMA. 2004;292(2):224–36. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.2.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Eaton LA, Kalichman S. Risk compensation in HIV prevention: implications for vaccines, microbicides, and other biomedical HIV prevention technologies. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2007;4(4):165–72. doi: 10.1007/s11904-007-0024-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gribble JN, et al. The impact of T-ACASI interviewing on reported drug use among men who have sex with men. Subst Use Misuse. 2000;35(6–8):869–90. doi: 10.3109/10826080009148425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Morrison-Beedy D, Carey MP, Tu X. Accuracy of audio computer-assisted self-interviewing (ACASI) and self-administered questionnaires for the assessment of sexual behavior. AIDS Behav. 2006;10(5):541–52. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9081-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saunders JB, et al. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption II. Addictions. 1993;88(6):791–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maisto SA, et al. An empirical investigation of the factor structure of the AUDIT. Psychol Assess. 2000;12(3):346–53. doi: 10.1037//1040-3590.12.3.346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Napper L, et al. HIV Risk Behavior Self-Report Reliability at Different Recall Periods. AIDS Behav. 2009;14:152–161. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9575-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bangsberg DR, et al. Comparing objective measures of adherence to HIV antiretroviral therapy: Electronic medication monitors and unannounced pill counts. AIDS Behav. 2001;5:275–281. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kalichman SC, et al. Monitoring Antiretroviral adherence by unannounced pill counts conducted by telephone: Reliability and criterion-related validity. HIV Clin Trials. 2008;9:298–308. doi: 10.1310/hct0905-298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kalichman SC, et al. Adherence to antiretroviral therapy assessed by unannounced pill counts conducted by telephone. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22:1003–1006. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0171-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kalichman SC, et al. Alcohol use and sexual risks for HIV/AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa: systematic review of empirical findings. Prev Sci. 2007;8(2):141–51. doi: 10.1007/s11121-006-0061-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cohen MS, McCauley M, Gamble TR. HIV treatment as prevention and HPTN 052. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2012;7(2):99–105. doi: 10.1097/COH.0b013e32834f5cf2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Quinn TC, et al. Viral load and heterosexual transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Rakai Project Study Group. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(13):921–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200003303421303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hasse B, et al. Frequency and determinants of unprotected sex among HIV-infected persons: the Swiss HIV cohort study. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;51(11):1314–22. doi: 10.1086/656809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kobin AB, Sheth NU. Levels of adherence required for virologic suppression among newer antiretroviral medications. Ann Pharmacother. 2011;45(3):372–9. doi: 10.1345/aph.1P587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bangsberg DR, Kroetz DL, Deeks SG. Adherence-resistance relationships to combination HIV antiretroviral therapy. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2007;4(2):65–72. doi: 10.1007/s11904-007-0010-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bangsberg DR, Deeks SG. Is average adherence to HIV antiretroviral therapy enough? J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17(10):812–3. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2002.20812.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]