Abstract

Study question

S-Nitrosoglutathione is an endogenous airway smooth muscle relaxant. Increased airway S-Nitrosoglutathione breakdown occurs in some asthma patients. We asked whether patients with increased airway catabolism of this molecule had clinical features that distinguished them from other asthma patients.

Methods

We measured S-Nitrosoglutathione reductase expression and activity in bronchoscopy samples from 66 subjects in the Severe Asthma Research Program. We also analysed phenotype and genotype data from in the program as a whole.

Results

Airway S-nitrosoglutathione reductase activity was increased in asthma patients (p = 0.032). However, only a subpopulation was affected, and this subpopulation was not defined by a “severe asthma” diagnosis. Subjects with increased activity were younger, had higher Immunoglobulin E and an earlier onset of symptoms. Consistent with a link between S-Nitrosoglutathione biochemistry and atopy, 1) interleukin 13 increased S-Nitrosoglutathione reductase expression, and 2) subjects with an S-Nitrosoglutathione reductase single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) previously associated asthma had higher Immunoglobulin E than those without this SNP. Expression was higher in airway epithelium than in smooth muscle, and was increased in regions of the asthmatic lung with decreased airflow.

Answer to the question

An early-onset, allergic phenotype characterizes the asthma population with increased S-Nitrosoglutathione reductase activity.

Introduction

S-Nitrosoglutathione (GSNO) is one of a class of endogenous S-NO bond-containing species (S-nitrosothiols) that serve as signalling molecules and airway smooth muscle relaxants (1–5). Nitrosylating and denitrosylating enzymes regulate the formation and breakdown of S-nitrosothiols (4–8). In the cellular environment, S-nitrosylated proteins are in transnitrosation equilibria with reduced glutathione (GSH) (4–8). Thus, enzymatic denitrosylation of GSNO depletes S-nitrosylated proteins in a given cell or compartment. The most extensively studied denitrosylating enzyme in the lung is GSNO reductase, also known as alcohol dehydrogenase 5 (ADH5; 4–6, 9–10).

Levels of GSNO and other S-nitrosothiols are decreased in the airway lining fluid of many patients with mild asthma, and intratracheal levels are profoundly low in children with acute asthmatic respiratory failure (10, 11). The GSNO reductase-deficient mouse is protected from methacholine-induced bronchoconstriction (9) and endogenous S-nitrosothiols prevent tachyphylaxis to β2-adrenergic agonists (3). Further, inhaled GSNO decreases airway levels of IL4, IL5, IL6, IL13 and other mediators associated with allergic airway inflammation (5). Indeed, GSNO reductase gene single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNP’s) are associated with increased asthma incidence in specific human asthma subpopulations (12–14). Thus, it is suggested that GSNO replacement—and/or the inhibition of GSNO reductase—could attenuate asthma symptoms in humans (15).

Of concern, however, is that long-term treatment aimed at substantially increasing airway levels of S-nitrosothiols in patients who already have normal levels could theoretically predispose them to adverse consequences (16–18) or could paradoxically increase airway hyper-responsiveness at higher doses (5). Further, most patients with mild asthma have normal airway levels of epithelial GSNO reductase activity (10). Therefore, not all asthma patients should be treated with S-nitrosothiol repletion or GSNO reductase inhibition. Here, our goal has been to identify the determinants of increased GSNO reductase activity and the phenotypic features of this subpopulation of asthma patients. With this information, personalized therapy might be envisioned to those most likely to respond.

Personalized asthma treatment is particularly important for severe asthma. Patient response to standard therapies, including leukotriene receptor antagonists and inhaled corticosteroids, is sub-optimal in many patients with severe asthma (19, 20). Targeting likely responders will likely decrease both the cost and the toxicity of treatment. Further, severe asthma patients are defined as those who are highly symptomatic despite these treatments; these patients may particularly benefit from a medical approach in which responsiveness is suspected based on a clinical phenotype, diagnostic testing is performed, and targeted treatment is given. Here, we have begun to approach this type of paradigm by studying the phenotype of the asthma subpopulation with increased airway GSNO reductase activity.

Methods

Subjects

Non-smoking subjects with severe and non-severe asthma, as well as healthy controls, enrolled in the Severe Asthma Research Program (SARP) underwent previously described characterization procedures (19) using the ATS consensus pane definition of (20). A subpopulation underwent hyperpolarized helium (HHe-3) MRI imaging (21). Not all subjects underwent all tests. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board at the SARP centres, and participants provided informed consent.

Bronchoscopy

Adult subjects underwent flexible bronchoscopy with BAL and endobronchial biopsies of segmental carinae, using our published methods (22). Children with severe asthma underwent bronchoscopy for clinical indications according to a shared sample protocol at Emory University (23). Biopsies were paraffin embedded and subjected to immunohistochemistry and hematoxylin/eosin staining. At Emory, the lavage fluid was aspirated in initial and terminal phase fractions (23). To identify well- and poorly-ventilated lung regions, three subjects scheduled for bronchoscopy underwent hyperpolarized helium (HHe-3) MRI (see below); within 12 hours, biopsies were performed in airways with and without ventilatory defects.

Imaging

Subjects underwent HHe-3 MRI according to an established protocol (21, 27).

Biochemical assays

GSNO reductase was measured as NADH-dependent loss of GSNO over time using two separate methods with strong concordance: 1) mass spectrometry, and 2) spectrophotometry (16, 24).

Cell culture

Primary human airway smooth muscle (HASM) cells from the Panettieri lab were cultured as previously described (25). Normal human bronchial epithelial cells (NHBE, Lonza) were grown as monolayers, and primary human bronchial epithelial cells were grown at air-liquid interface as previously described (26). Cystic fibrosis bronchial epithelial (CFBE41o-) and A549 cell lines were grown as previously described (17, 26).

Immunoblot

GSNO reductase AB (1:1000) (Protein Tech Group # 11051-1-AP) and second HRP 1:10.000 was used to immunostain for HASM, and CFBE cells. Additionally, airway expression was confirmed using a separate polyclonal rabbit anti-GSNO reductase AB (kind gift of Dr. L. Que [9, 10]) with goat anti-rabbit secondary AB (BIORAD # 172-1019).

Immunohistochemistry

Tissue sections were immunoblotted with GSNO reductase AB (1:1000) (Protein Tech Group # 11051-1-AP) using secondary goat anti-rabbit (1: 10,000; Protein Tech Group #11051-1-AP; 30 min, RT) and ABC reagent (Vector Labs) for 30 min, (RT), as described (17) and scored from 0 (absent) to 4+ (intense staining) by two observers (BG and WGT) blinded to the diagnosis.

SNP Genotyping and assessment

The ADH5 genotypes were acquired from the Illumina Human1M-Duo DNA BeadChip. Hardy-Weinberg Equilibrium was tested for quality control.

Statistical analysis

By univariate analysis, we studied the relationship between GSNO reductase activity and risk factors. A t-test or non-parametric rank-sum test was used for two-sample comparison of continuous variables, a Fisher exact test was used for two-sample comparison of categorical variables, and analysis of variance was used for categorical variables with more than two categories. A p value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The statistical analyses were carried out in SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

Subjects

We studied 52 adults (12 healthy controls, 25 non-severe asthma, and 15 severe asthma) and 14 children (2 healthy controls, 6 non-severe asthma, and 6 severe asthma) (Table 1). These subjects were enrolled at 5 different sites participating in SARP. Through site-specific protocols, subsets of subjects underwent specific procedure (biopsy, bronchoalveolar lavage [BAL] and/or MRI). BAL’s were performed in the right middle lobe or lingula. Except where directed by MRI, biopsies were performed at a mainstem, third or fourth generation carina contralateral to the BAL site. Genetic analysis was additionally performed on 914 asthma subjects and 344 controls obtained from sites participating in SARP.

Table 1.

Characteristics of subjects who underwent bronchoscopy

| Control | Non-severe asthma | Severe asthma | ANOVA | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adults: SARP-wide | ||||

| N (M/F) | 12 (7/5) | 25 (8/17) | 15 (6/9) | NS |

| Age (y) | 27 ± 5.9 | 32 ± 11 | 39 ± 17 | P < 0.02 |

| Race (C/AA/As/O/M) | 10/1/1/0/0 | 20/3/0/1/1 | 9/3/0/0/3 | NS |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 26 ± 4.8 | 27 ± 5.6 | 29 ± 6.8 | NS |

| pre-bronchodilator FEV1 (%) | 95 ± 8.9 | 90 ± 14 | 67 ± 20 | P < 0.0001 |

| pre-bronchodilator FVC (%) | 100 ± 11 | 96 ± 13 | 82 ± 15 | P < 0.0006 |

| pre-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC | 0.79 ± 0.05 | 0.78 ± 0.1 | 0.67 ± 0.09 | P < 0.0006 |

| pc20 MC (mg/ml) | 41 ± 16 | 6.8 ± 11.4 | 2.8 ± 6.0 (n=9) | P < 0.0001 |

| IgE, blood (IU/ml) | 32 ± 36 | 407 ± 1147 (n=24) | 230 ± 290 (n=14) | NS |

| On any inhaled steroid | 0% | 48% | 100% | |

| Number of positive skin reactions | 1.2 ± 1.9 | 4.2 ± 3.0 (n=24) | 4.1 ± 2.2 (n=13) | P < 0.01 |

| Children | ||||

| N (M/F) | 2 (0/2) | 6 (4/2) | 6 (3/3) | NS |

| Age (y) | 16 ± 0.7 | 11 ± 3.2 | 11 ± 4.2 | NS |

| Race (C/AA) | 2/0 | 5/1 | 1/5 | P < 0.004 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 33 ± 15 | 22 ± 10 | 17 ± 3.4 | P < 0.05 |

| pre-bronchodilator FEV1 (%) | 95 ± 0.7 | 100 ± 15 | 76 ± 19 | NS |

| pre-bronchodilator FVC (%) | 94 ± 5.7 | 106 ± 17 | 82 ± 26 | NS |

| pre-bronchodilator FEV1/FVC | 0.88 ± 0.04 | 0.87 ± 0.09 | 0.65 ± 0.14 | P < 0.009 |

| IgE, serum (kU/L) | 67 ± 78 | 140 ± 148 | 1025 ± 1081 | NS |

| On any inhaled steroid | 0% | 83% | 100% |

M, male; F, female; C, Caucasian; AA, African-American; As, Asian; O, Other; M, Multiple; BMI, body mass index; FEV1, forced expiratory volume; FVC, forced vital capacity; pc20, provocative concentration causing a 20% fall in FEV1, MC, methacholine; NS, not significant. Note that values are reported as group mean ± standard deviation. All parameter’s n’s are consistent unless otherwise noted.

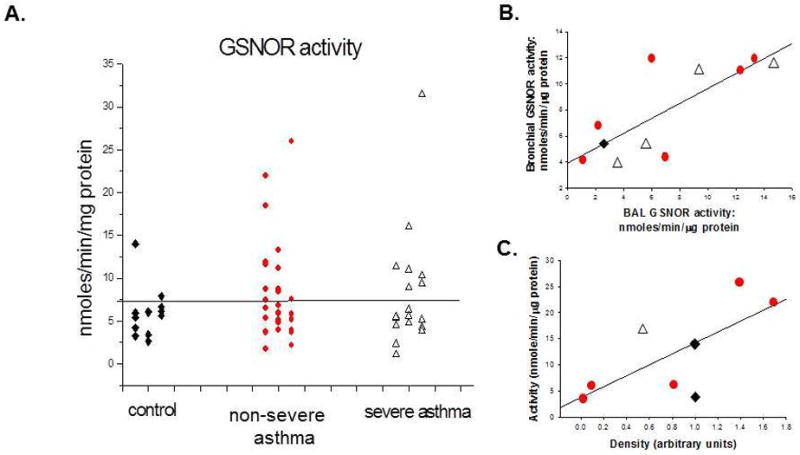

GSNO reductase activity

We measured GSNO reductase activity in 54 BAL cell lysates (16 patients with severe asthma, 25 with non-severe asthma, and 13 controls). Overall mean values did not differ between the three groups (p = NS). There was a subpopulation of 44% of the asthma patients with levels > 7.5 nmole/min/μg protein (more in asthma than controls; p = 0.032; Figure 1A). We performed immunoblot for GSNO reductase on a subpopulation of 9 BAL samples (one control, one severe and seven non-severe). There was a weak concordance between measures of GSNO reductase activity in airway vs alveolar lavage samples (n = 11; r2 = 0.61; Figure 1B and 1C) and between BAL GSNO reductase expression and activity (r2 = 0.54; Figure 1C) - consistent with a previous report (10). Activity did not vary with BAL cell count, differential or other parameters.

Figure 1. S-Nitrosoglutathione (GSNO) reductase activity in asthma.

A. GSNO reductase activity was measured in the bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) cell lysate of 54 subjects, including 13 control subjects, and 25 subjects with non-severe asthma and 16 subjects with severe asthma. Severe and non-severe asthma did not differ (p = ns). A greater proportion of subjects with asthma had high activity (>7.5 nmole/min/μg protein) than did controls (p = 0.032). B. A subset of subjects underwent analysis of an early (proximal) and late (distal) lavage fraction. Activities were weakly correlated between these two fractions (r2 = 0.61). C. Consistent with the previous report, activity was roughly correlated with protein expression (measured by immunoblot, densitometry) (r2 = 0.54). Activity was not correlated with BAL cell type (p = NS). Diamonds: controls; Circles: non-severe asthma; Triangles: severe asthma.

Tissue GSNO reductase expression

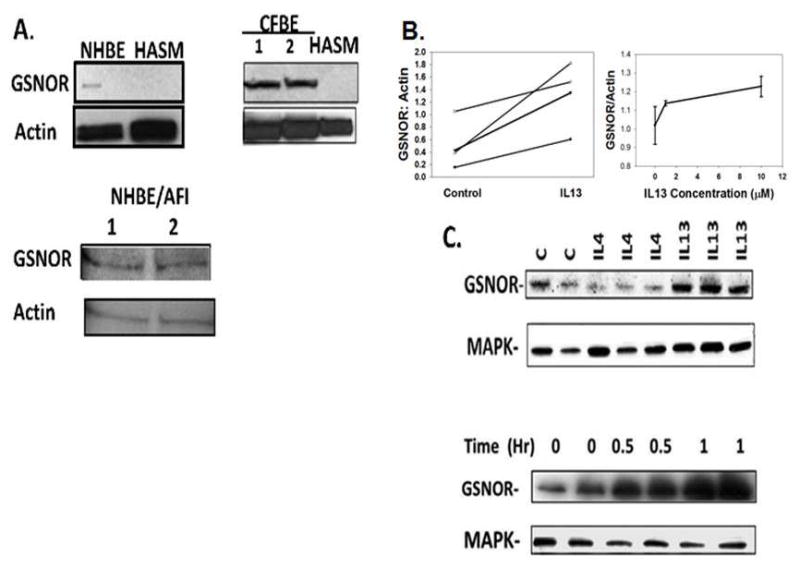

Next, we studied GSNO reductase tissue expression in random endobronchial biopsies (i.e., not directed by HHe3 imaging; n = 18, including 6 severe asthma, 4 non-severe asthma and 8 controls). There was less GSNO reductase expression in smooth muscle cells than in epithelial cells (p < 0.05) (Figure 2). However, GSNO reductase immunoreactivity did not differ between asthma and control patients in epithelial, smooth muscle or inflammatory cells. Immunoreactivity localized primarily to the apical regions of airway epithelial cells of healthy lung. This was not the case in epithelium from asthmatic subjects, where immunoreactivity localized to basal cells (Figure 2). Consistent with these data, HASM cells expressed less GSNO reductase, relative to protein load control, than NHBE cells in cultured monolayers, NHBE cells grown as pseudostratified epithelium at AFI, and the established airway cell lines CFBE (cystic fibrosis bronchial epithelial) (Figure 3A). Of note, Interleukin (IL) 13 increased epithelial GSNO reductase expression in severe asthma native BAL cell pellets ex vivo, and in cultured epithelial cells in vitro, whereas IL4 was not effective (Figure 3B, C).

Figure 2. GSNO reductase expression is primarily epithelial cells.

Lower lobe biopsy sections were embedded in paraffin and immunostained for S-Nitrosoglutathione reductase as described in the Methods. A. Control lung showing GSNO reductase immunoreactivity in the pseudostratified airway epithelium (100X). B. C. Non-severe asthma showing a similar distribution of GSNO reductase activity, particularly in the apex of the pseudostratified epithelium, less in basal membrane and smooth muscles. D.E. Severe asthma showing loss of epithelium and thickening of the basal membrane. Severe asthma (100X); note more prominent staining of the epithelium than of the smooth muscle. F. Control immunostaining of non-severe asthma showing absence of immunoreactivity in the absence of primary antibody.

Figure 3. GSNO reductase expression is greater in human airway epithelial cells than smooth muscle cells and is increased by interleukin (IL) 13.

A. Immunoblots were performed on human normal bronchial epithelial cells (NHBE), both in monolayer culture and cultured at air-fluid interface (AFI). Studies were also performed on established cultures of human cystic fibrosis bronchial epithelial cells (CFBE) and on primary human airway smooth muscle (HASM) cells from six patients with asthma. Expression was greater in epithelial cells than in HASM cells, though there was variability in HASM expression. B. Left: freshly spun BAL cell pellets from severe asthma patients was exposed to interleukin IL 13 (10 ng/mL; 4 hr.) ex vivo. GSNO reductase expression was increased by interleukin-13 (n = 4; p < 0.05). Right: IL 13 incubation (2 hr.) also increased GSNO reductase expression in A549 cells in a dose-dependent manner. C. IL13, but not IL4, increased GSNO reductase expression (10 ng/mL each; 4 hr. p = 0.05 by ANOVA) relative to load control, and IL13 (10 ng/mL) also caused a time-dependent, 2-fold increase in GSNO reductase expression after 2 hours.

Consistent with previous reports (21, 27), HHe-3 imaging showed regions focal ventilatory defects in the lungs of subjects with severe asthma (n = 3), Figure 4. In Figure 4A (coronal image) and 4B (transverse image) ventilation defects are shown at baseline in stable, severe asthma patient. In C, a second image acquired after albuterol administration shows only moderate improvement in the left upper lobe ventilation defect. Image-guided endobronchial biopsy done in the segmental airways supporting well-ventilated lung region (green arrows, Figure 4A) showed relatively preserved epithelial integrity, less GSNO reductase immunoreactivity and less inflammation (Figure 4G,H,I) than biopsy taken from airways supporting region with focal ventilatory defects (red arrows, Figure 4A,D,E,F). Overall, when epithelium was present, it was immunostained more for GSNOR (3–4/4 in obstructed airways vs 2–3/4 in non-obstructed airways).

Figure 4. Regional inhomogeneity of inflammation and GSNO reductase expression in a severe asthma patient.

On the day of hyperpolarized helium MRI scanning (21,27), the radiologist reported to the bronchoscopist the regions of good ventilation and poor ventilation to guide the biopsies. Green represents areas of good ventilation, and red represents poor ventilation. In A (coronal image) and B (transverse image) ventilation defects are shown at baseline in this stable, severe asthma patient. In C, a second image acquired after albuterol administration shows only moderate improvement in the left upper lobe ventilation defect. D and E. Inflammation and epithelial injury with increased GSNO reductase expression in the poorly ventilated lung unit (D, 40X; E, 100X). F. H&E staining in a sample from the poorly ventilated lung unit shows inflammation. G and H. GSNO reductase immunoreactivity in a sample from the well ventilated lung unit (G, 40X; H, 100X). I shows preserved airway epithelium, though thickened basement membrane, in a sample from the well ventilated lung unit (40X).

Phenotype analysis of patients with increased GSNO reductase activity

We next analysed the clinical phenotype of well-characterized SARP patients with evidence for increased airway GSNO reductase activity. Of the asthmatic subjects with BAL GSNO reductase activity measures, 31 were fully characterized in the SARP database (Table 2). Those with GSNO reductase activity over 7.5 nmole/min/μg protein had higher IgE (p=0.01) and were diagnosed with asthma and allergies at a younger age (p=0.02). Also, they were younger, had lower BMI, had lower daytime sleepiness snores on OSA screening and were less likely to have exercise-induced symptoms (each p < 0.05). Asthmatic subjects with increased GSNO reductase activity did not have a significantly lower methacholine PC20 (1.02 [0.92]) than those with low GSNO reductase activity (4.32 [6.79], p = 0.22).

Table 2.

Relationship between GSNO reductase activity and risk factors: univariate analysis of subjects with complete datasets.

| Below 7.5 (Mean, SD) (N=19) | Above 7.5 (Mean, SD) (N=12) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (Age at enrolment into SARP, years) | 38.65 (10.5) | 24.29 (8.9) | 0.001 |

| BMI | 29.71 (5.7) | 24.09 (7.0) | 0.021 |

| Gender: | 0.174 | ||

| Female * | 17 | 8 | |

| Male | 2 | 4 | |

| Severity (Subject Classification): | 0.36 | ||

| Not Severe | 11 (35.5%) | 9 (29.0%) | |

| Severe | 8 (25.8%) | 3 (9.7%) | |

| Number of years have had asthma: Screening Questionnaire | 23.95 (10.80) | 17.17 (5.94) | 0.032 |

| Age when allergies developed: Atopic Diseases | 13.31 (11.60) (n=16) | 5.18 (4.84) (n=11) | 0.020 |

| Sleep Apnoea Score: Sleep and Daytime Alertness | 29.19 (7.25) (n=16) | 19.70 (4.03) (n=10) | 0.001 |

| Baseline predrug FEV1, litres | 2.40 (0.75) | 3.10 (1.12) | 0.044 |

| Predicted FEV1/FVC: Hankinson | 0.83 (0.03) | 0.85 (0.02) | 0.007 |

| Log10 IgE: Blood | 1.78 (0.64) (n=18) | 2.47 (0.66) (n=12) | 0.008 |

| Asthma symptoms aused by routine physical activity: Provoking Factors | 13 (44.8%) | 2 (6.9%) | 0.008 |

Using one-sample proportions exact test, there was a greater proportion of females in the < 7.5 category than in the > 7.5 category (p=0.001).

GWAS data from the SARP

One well-studied SNP in the GSNO reductase promoter associated with good responsiveness to β2 adrenergic treatment (rs 1154400; ref 13) was available on the Illumina IMDuo chip used in the SARP. This SNP is in a region associated with protection from asthma in Caucasian populations (13–15) and the C/C genotype was associated with improved asthma outcomes and β2 responsiveness in an African American population (13); the authors, however, did not measure airway GSNOR activity. The rs1154400 genotypes were in the Hardy Weinberg equilibrium in the SARP population. Of the subjects who had both BAL GSNO reductase analysis and GWAS, none with high GSNO reductase activity in BAL had the C/C genotype, but the differences did not achieve significance because of sample size. In the SARP population as a whole, those asthmatics with C/T and T/T genotypes were more allergic than those with the C/C genotype (IgE 362 ± 846 IU/mL I6/ml [n = 7.52 IU/ml] vs 245 ± 374 IU/mL [n = 76]; p = 0.028); and, of those with a positive skin prick test, wheal diameters were greater to Dermatophagoyetes farinae (10.8 mm ± 6.0mm [n = 449] vs 8.8± 4.5 mm [n = 42], p = 0.009). Note that the C/T and C/T genotype patients had lower EBC pH than C/C (7.7 ± 0.8 [n = 449] vs. 8.0 ± 0.5 [n = 45], p = 0.0004), consistent with data that high EBC formic acid levels may be associated with increased airway GSNO reductase activity (28). Consistent with the Moore data (22), though C/C did not differ from C/T-T/T with regard to baseline FEV1 (p = NS), FEV1 after four and six puffs of albuterol was higher in the C/C group than in the C/T-T/T group (four puffs: 91.7 +/− 17.3 % predicted [n = 81] vs 86.0 +/− 20.0 % [n = 697], p = 0.013; and six puffs: 92.7 +/− 17.1% [n = 72] vs 87.4 +/− 20.2% [n = 697], p = 0.034). The genotype groups did not differ in terms of age, gender or BMI.

Discussion

GSNO and other S-nitrosothiols cause airway smooth muscle relaxation in humans and other species (2, 4, 29–31). Levels of S-nitrosothiols are low, and activity of GSNO reductase is high, in the airways of children with severe asthma who are experiencing an acute exacerbation associated with respiratory failure (11). Here, we studied airway GSNO reductase expression and activity in stable outpatients with severe and non-severe asthma.

Activity of GSNO reductase was increased in the bronchoalveolar lavage cells of some stable outpatients with asthma. However, it was normal in many severe asthma patients: increased activity is not a defining pathophysiological feature of severe asthma. Consistent with the work of Que, et al. (10), activity was also normal in the bronchoalveolar lavage of a large proportion of stable, non-severe asthmatics. Our data extend the observation to cases of severe asthma. In part, this is likely because there is population heterogeneity in GSNO reductase expression that is genetically determined. Previous studies have shown that increased airway GSNO reductase activity—and associated SNPs—are present only in a minority of patients with asthma (10, 12–14).

There is interest in treating asthma patients with GSNO reductase inhibition. Because a substantial chronic excess of S-nitrosothiols in the context of nitrosative stress has the potential to be associated with adverse effects (5,16–18), it is important to target nitrosothiol repletion only to those patients who have an airway S-nitrosothiol deficiency and/or excessive GSNO catabolism associated with asthma. The SARP data suggest a specific phenotype. Patients with increased expression were more allergic, with earlier onset of asthma and allergies. They were younger and smaller, with less OSA. They were not, however, more “severe” (20). This proposed phenotype will require validation.

In a mouse model, GSNO inhalation modestly suppresses both Th1 and Th2 cytokine responses, including IL13 production, to antigen (5). We also found that SARP subjects with a GSNO reductase-associated SNP associated with impaired β2 responsiveness in the study by Moore (12) were more allergic. As predicted by Whalen (3), data from Choudry and co-workers show that asthma and impaired β2 responsiveness are associated with genotypes causing GSNO reductase gain-of-function. Here, we have confirmed the finding that the bronchodilator responsiveness of subjects with C/C was great than that of subjects with CT/and T/T (12). This process may feed forward in asthma. Increased Th2 activation and IL13 production would further increase GSNO reductase expression and activity (ref 5 and our data), particularly favouring increased GSNO reductase expression in allergic patients (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Proposed scheme showing the effect of increased GSNO reductase on asthma.

A subset of patients, as previously reported (10, 12–14) has a diathesis to have increased GSNO reductase expression. This is driven by allergic airway inflammation. In turn, this causes a decrease in airway GSNO levels that leads to smooth muscle constriction (1–7, 29–31) and further increase in Th2 cytokine expression (5).

Bronchoscopic results can be flawed in asthma patients. Here, we have shown that GSNO reductase activity levels in patients may have reflected the lung region sampled, not simply overall phenotype. In our preliminary studies, expression was not uniform throughout the airway. One possible explanation is that the regional variations in expression result from treatment: inhaled corticosteroids may access the well-ventilated units, inhibiting inflammation and GSNO reductase expression. A previous HHe-3 study has shown that roughly 50% of poorly ventilated lung units have persistent defects (21), perhaps reflecting chronic lack of therapy. It is also possible that some airways—like the skin—have inherently different patterns of inflammation. Either way, it is important to recognize that there may be substantial intrasubject airway heterogeneity. Ongoing studies in the SARP and other programs are investigating this regional variability more prospectively.

Further, bronchoscopy is not without expense and potential risk. Therefore, non-invasive biomarkers may prove useful for diagnosing the high-GSNO reductase phenotype in clinic. Possibly consistent with low pH in the non-C/C genotype population, our previous data suggest that increased breath condensate formic acid levels might be a non-invasive marker for increased GSNO reductase activity (28). We have also previously shown that inhaled GSNO increases exhaled NO, followed by time-dependent decay (32). Therefore, an inhalational challenge with GSNO may test for the presence and/or the disinhibition of GSNO reductase activity in human asthmatics: the greater the activity of GSNO reductase, the higher the FENO after challenge. Airway homogeneity, in turn, could be assayed using different FENO flow rates. We believe that this kind of challenge testing—and/or breath condensate formic acid testing— may prove clinically useful to identify severe asthma patients who could be candidates for S-nitrosothiol replacement and/or inhibition of GSNO reductase.

Note that we found increased GSNO reductase activity in asthmatics was not significantly associated with methacholine PC20, though there was a trend in this direction. This could be explained by corticosteroid treatment. In our study 83% of patients with non-severe and 100% of patients with severe asthma received inhaled steroids. In the study by Que, et al. (10), only subjects with mild asthma were included, and they did not receive either high-dose inhaled or oral corticosteroids.

In summary, we found marked heterogeneity in GSNO reductase activity in subjects with both severe and non-severe asthma. Increased GSNO reductase activity is not, in general, the cause of severe asthma. We also present evidence that patients with increased airway GSNO reductase activity may have a more allergic phenotype. If validated, this high GSNO reductase phenotype could be suspected clinically based on history and physical exam and confirmed with genetic analysis and/or with biomarker testing in the lung function laboratory. This information, in turn, can be used to personalize treatment. We believe that this paradigm will be of increasing value in subspecialty asthma management.

Acknowledgments

Funding: NIH Severe Asthma Research Program Grant #5U10HL109250-02 (Gaston, PI); NIH Program Project Grant #5P01HL101871-02 (Gaston, PI); NIH R01 Grant #5RO1-HL059337-12 (Gaston, PI); NIH R01 Grant #HL097796 (Panettieri, PI); NIEHS P30 ES013508 (Panettieri, PI) NIH RO1 HL66479 (de Lange, PI)

SARP coordinators

Footnotes

Take home message: Asthma patients with increased airway activity of S-nitrosoglutathione reductase have early-onset asthma and are highly allergic.

References

- 1.Gaston B, Reilly J, Drazen JM, Fackler J, Ramdev P, Arnelle D, Mullins ME, Sugarbaker DJ, Chee C, Singel DJ, Loscalzo J, Stamler JS. Endogenous nitrogen oxides and bronchodilator S-nitrosothiols in human airways. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:10957–10961. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.23.10957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gaston B, Drazen JM, Jansen A, Sugarbaker DA, Loscalzo J, Stamler JS. Relaxation of human bronchial smooth muscle by S-nitrosothiols in vitro. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1994;268:978–984. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Whalen EJ, Foster MW, Matsumoto A, Ozawa K, Violin JD, Que LG, Nelson CD, Benhar M, Keys JR, Rockman HA, Koch WJ, Daaka Y, Lefkowitz RJ, Stamler JS. Regulation of beta-adrenergic receptor signalling by S-nitrosylation of G-protein-coupled receptor kinase 2. Cell. 2007;129(3):511–522. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gaston B, Doctor A, Singel D, Stamler JS. S-Nitrosothiol signalling in respiratory biology. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006;173:1186–1193. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200510-1584PP. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Foster M, Yang Z, Potts E, Foster W, Que L. S-nitrosoglutathione supplementation to ovalbumin-sensitized and -challenged mice ameliorates methacholine-induced bronchoconstriction. Am J Phyisol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2011;301:739–744. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00134.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 6.Fang K, Johns R, Macdonald T, Kinter M, Gaston B. S-Nitrosoglutathione breakdown prevents airway smooth muscle relaxation in the guinea-pig. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Molec Biol. 2000;279:L716–L21. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2000.279.4.L716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Forster MW, Hess DT, Stamler JS. Protein S-nitrosylation in health and disease: a current perspective. Trends Mol Med. 2009;15:391–404. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2009.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu L, Hausladen A, Zeng M, Heitman J, Stamler JS. A metabolic enzyme for S-nitrosothiol conserved from bacteria to humans. Nature. 2001;410:490–494. doi: 10.1038/35068596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Que LG, Liu L, Yan Y, Whitehead GS, Gavett SH, Schwartz DA, Stamler JS. Protection from experimental asthma by an endogenous bronchodilator. Science. 2005;308:1618–1621. doi: 10.1126/science.1108228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Que L, Zhonghui Y, Stamler JS, Lugogo NL, Kraft M. S-nitrosoglutathione reductase: an important regulator inhuman asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180:226–231. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200901-0158OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gaston B, Sears S, Woods J, Hunt J, Ponaman M, McMahon T, Stamler J. Bronchodilator S-nitrosothiol deficiency in asthmatic respiratory failure. Lancet. 1998;351:1317–19. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)07485-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu H, Romieu I, Sienra-Monge JJ, Estela Del Rio-Navarro B, Anderson DM, Jenchura CA, Li H, Ramirez-Aguilar M, Del Carmen Lara-Sanchez I, London SJ. Genetic variation in S-nitrosoglutathione reductase (GSNOR) and childhood asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120(2):322–328. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.04.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moore PE, Ryckman KK, Williams SM, Patel N, Summar ML, Sheller JR. Genetic variants of GSNOR and ADRB2 influence response to albuterol in African-American children with severe asthma. Ped Pulmonol. 2009;44(7):649–654. doi: 10.1002/ppul.21033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Choudhry S, Que LG, Yang Z, Liu L, Eng C, Kim SO, Kumar G, Thyne S, Chapela R, Rodriguez-Santana JR, Rodriguez-Cintron W, Avila PC, Stamler JS, Burchard EG. GSNO reductase and beta2-adrenergic receptor gene-gene interaction: bronchodilator responsiveness to albuterol. Pharmacogenetics and Genomics. 2010;20(6):351–358. doi: 10.1097/FPC.0b013e328337f992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Green LS, Chun LE, Patton AK, Sun X, Rosenthal GJ, Richards JP. Mechanism of inhibition for N6022, a first-in-class drug targeting S-nitrosoglutathione reductase. Biochem. 2012;51(10):2157–2168. doi: 10.1021/bi201785u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Palmer L, Doctor A, Chhabra P, Sheram ML, Laubach V, Gaston B. S-Nitrosothiols signal hypoxia-mimetic vascular pathology. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:2592–2601. doi: 10.1172/JCI29444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marozkina NV, Wei C, Yemen S, Wallrabe H, Nagji AS, Liu L, Morozkina T, Jones DR, Gaston B. S-nitrosoglutathione reductase in human lung cancer. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2012 Jan;46:63–70. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2011-0147OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wei W, Li B, Hanes MA, Kakar S, Chen X, Liu L. S-Nitrosylation from GSNOR deficiency impairs DNA repair and promotes hepatocarcinogenesis. Sci Transl Med. 2010;2:19(ra)13. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3000328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moore WC, Bleecker ER, Curran-Everett DC, Teague WG, Li H, Li X, D’Agostino R, Jr, Castro M, Curran-Everett D, Fitzpatrick AM, Gaston B, Jarjour NN, Sorkness R, Calhoun WJ, Chung KF, Comhair SA, Dweik RA, Israel E, Peters SP, Busse WW, Erzurum SC, Bleecker ER. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute’s Severe Asthma Research Program. Characterization of the severe asthma phenotype by the NHLBI Severe Asthma Research Program. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;119:405–413. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.11.639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Busse WW, Banks-Schlegel S, Wenzel SE. Pathophysiology of severe asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2000;106(6):1033–1042. doi: 10.1067/mai.2000.111307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.De Lange EE, Altes TA, Patrie JT, Battiston JJ, Juersivich AP, Mugler JP, 3rd, Platts-Mills TA. Changes in regional airflow obstruction over time in the lungs of patients with asthma: evaluation with 3He MR imaging. Radiology. 2009;250(2):567–575. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2502080188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Moore WC, Evans MD, Bleecker ER, Busse WW, Calhoun WJ, Castro M, Chung KF, Erzurum SC, Curran-Everett D, Dweik RA, Gaston B, Hew M, Israel E, Mayse ML, Pascual RM, Peters SP, Silveira L, Wenzel SE, Jarjour NN National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute’s Severe Asthma Research Group. Safety of investigative bronchoscopy in the Severe Asthma Research Program. J Allerg Clin Immunol. 2011;128:328–336. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.02.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fitzpatrick AM, Brown LA, Holguin F, Teague WG. Nitric oxide oxidation products are increased in the epithelial lining fluid of children with severe asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124:990–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.08.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gow A, Doctor A, Mannick J, Gaston B. S-Nitrosothiol measurements in biological systems. J Chromatog B. 2007;851:140–151. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2007.01.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Amrani Y, Syed F, Huang C, Li K, Liu V, Jain D, Keslacy S, Sims MW, Baidouri H, Cooper PR, Zhao H, Siddiqui S, Brightling CE, Griswold D, Li L, Panettieri RA., Jr Expression and activation of the oxytocin receptor in airway smooth muscle cells: Regulation by TNFα and IL-13. Respir Res. 2010;11:104. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-11-104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Marozkina NV, Yemen S, Borowitz M, Liu L, Plapp M, Sun F, Islam R, Erdmann-Gilmore P, Townsend RR, Lichti C, Mantri S, Clapp P, Randell S, Gaston B, Zaman K. Hsp70/Hsp90 organizing protein as an S-nitrosylation target of corrector therapy in cystic fibrosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:11393–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909128107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fain SB, Gonzalez-Fernandez G, Peterson ET, Evans MD, Sorkness RL, Jarjour NN, Busse WW, Kuhlman JE. Evaluation of structure-function relationships in asthma using multidetector CT and hyperpolarized He-3 MRI. Acad Radiol. 2008 Jun;15(6):753–62. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2007.10.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Greenwald R, Fitzpatrick AM, Gaston B, Marozkina NV, Erzurum S, Teague WG. Breath formate is a marker of airway S-nitrosothiol depletion in severe asthma. PLoS One. 2010 Jul 30;5(7):e11919. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bannenberg G, Xue J, Engman L, Cotgreave I, Moldéus P, Ryrfeldt A. Characterization of bronchodilator effects and fate of S-nitrosothiols in the isolated perfused and ventilated guinea pig lung. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1995;272:1238–1245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Janssen LJ, Premji M, Hwa L, Cox G, Kshavjee S. NO+ but not NO radical relaxes airway smooth muscle via cGMP-independent release of internal Ca2+ Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2000;278:899–905. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.2000.278.5.L899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Perkins W, Pabelick C, Warner DO, Jones KA. cGMP-independent mechanism of airway smooth muscle relaxation induced by S-nitrosoglutathione. Am J Physiol. 1998;275:468–474. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.1998.275.2.C468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Snyder A, McPherson ME, Hunt JF, Johnson M, Stamler JS, Gaston B. Acute effects of aerosolized S-nitrosoglutathione in cystic fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165:922–926. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.165.7.2105032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]