Abstract

A new and efficient total synthesis has been developed to obtain plagiochin G (22), a macrocyclic bisbibenzyl, and four derivatives. The key 16-membered ring containing biphenyl ether and biaryl units was closed via an intramolecular SNAr reaction. All synthesized macrocyclic bisbibenzyls inhibited Epstein-Barr virus early antigen (EBVEA) activation induced by the tumor promoter 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate (TPA) in Raji cells and, thus, are potential cancer chemopreventive agents.

Keywords: Bisbibenzyls, Plagiochin G, Intramolecular SNAr reaction, Cancer chemopreventive agents, Epstein-Barr virus early antigen (EBV-EA)

Cancer, the second leading cause of death in humans, is a group of illnesses resulting from abnormal growth of cells in the body. Many cancer therapies, especially various anticancer agents, have been developed since the beginning of the last century. However, several problems, such as adverse side effects and drug resistance, have also encouraged scientists to explore strategies to prevent premalignant cells from completing the process of carcinogenesis. This concept known as “cancer chemoprevention” has been developed over the past few decades,1 and the Epstein-Barr virus early antigen (EBV-EA) activation assay has been established to quickly evaluate chemopreventive activity in vitro.2-4

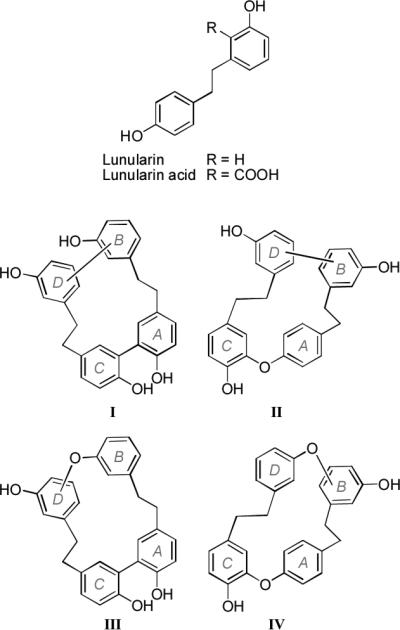

Macrocyclic bisbibenzyls are phenolic natural products that occur mainly in liverworts and exhibit remarkable biological activities, such as 5-lipoxygenase, cyclooxygenase, and calmodulin inhibitory effects, as well as antifungal, anti-HIV, antimicrobial, and cytotoxic activities.5-7 These compounds are divided into four distinct structural types (I−IV, Figure 1),8 each containing four aromatic rings (labelled A−D) and two ethylene bridges, and originate biosynthetically from bibenzyl lunularin or its precursor lunularin acid.7, 9 The plagiochin family of type II macrocyclic bisbibenzyls includes natural plagiochins A−D isolated from the liverwort Plagiochila acanthophylla by Hashimoto et al.10 and plagiochins E−H synthesized by Speicher et al.11

Figure 1.

Four distinct structural types of macrocyclic bisbibenzyls.

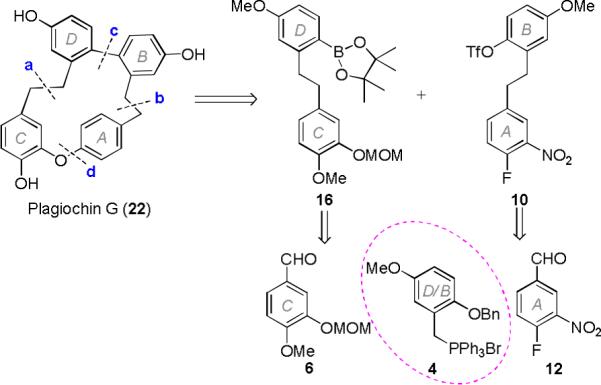

The unusual structures and intriguing biological activities of macrocyclic bisbibenzyls have made them attractive synthetic targets. In 1992, Keseru et al.12 synthesized plagiochins C and D by using a Wurtz-type coupling at position a to close the 16-membered ring (Scheme 1). In 1999, Fukuyama et al.13, 14 used an intramolecular Still-Kelly reaction at position c to accomplish the macrocyclization in the syntheses of plagiochins A and D. “Plagiochin E”, initially reported as a natural product from the liverwort Marchantia polymorpha,15 was totally synthesized in 2009 by Speicher et al., who revised the structure of the isolated “plagiochin E” to that of riccardin D.16, 17 Subsequently, in 2010, Speicher et al. reported the syntheses of plagiochins E−H by employing an intramolecular McMurry reaction at position a as the key macrocyclization step (Scheme 1).11 In 2011, Cortes Morales et al.18 used an intramolecular SNAr reaction at position d to form the 16-membered macrocyclic ring of plagiochin D (Scheme 1). Recently, Jiang et al. prepared plagiochin E using an intramolecular McMurry reaction at position a for the macrocyclization (Scheme 1).19

Scheme 1.

Retrosynthetic analysis of plagiochin G.

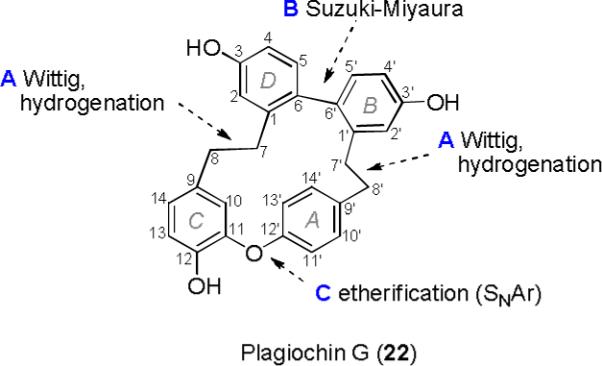

In the course of our ongoing efforts to find bioactive macrocyclic bisbibenzyls, we developed a new route to synthesize plagiochin G and several ester derivatives. We initially synthesized two lunularin presurors (10 and 16), then formed the aryl-aryl bond between rings B and D by using a Pd-catalyzed Suzuki-Miyaura coupling reaction, and finally applied an intramolecular SNAr reaction20 at position d to achieve the key 16-membered ring closure (Scheme 1 and Figure 2). Furthermore, we found that all macrocyclic bisbibenzyls produced by this new route exhibited potential cancer chemopreventive activity. Herein, we report the synthetic details for producing plagiochin G (22) and its derivatives (19−21 and 22a−22d) as well as the evaluation of their cancer chemopreventive activity.

Figure 2.

Construction unit system for the synthesis of plagiochin G.

Chemistry

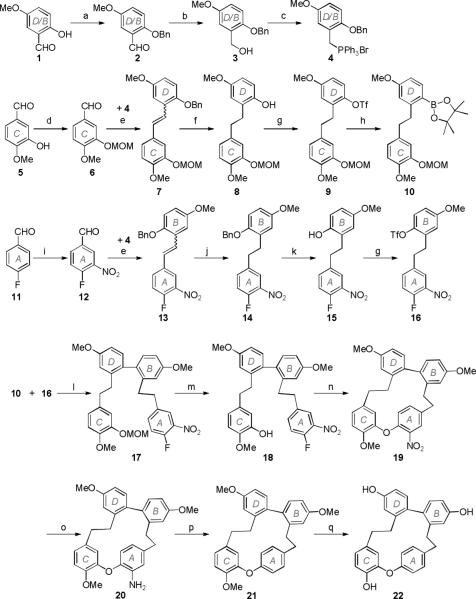

The total synthesis of plagiochin G was achieved in 12.5% overall yield in 14 steps as shown in Scheme 2. Both rings B and D were produced from the commercially available 2-hydroxy-5-methoxybenzaldehyde (1). The phenol moiety of 1 was protected by reaction with benzyl bromide. Then, the aldehyde moiety was reduced to a benzyl alcohol with NaBH4, and the resulting compound (3) was treated with PPh3·HBr to give the phosphonium salt 4.

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of plagiochin G. Reagents and conditions: (a) BnBr, K2CO3, acetone, reflux; (b) NaBH4, MeOH, 0 °C, 20 min, then r.t., 1 h; (c) PPh3·HBr, MeCN, reflux, 1 h; (d) chloromethyl methyl ether, diisopropylethylamine, CH2Cl2, 0 °C, then r.t., 6 h; (e) K2CO3, 18-crown-6, CH2Cl2, reflux, 8 h; (f) Pd/C (10%), 1 bar H2, MeOH, r.t., 24 h; (g) Et3N, CH2Cl2, 0 °C, trifluoromethanesulfonic anhydride, then r.t., 0.5 h; (h) PdCl2(dppf), Et3N, pinacolborane, dioxane, reflux; (i) H2SO4, HNO3, −5 °C, then r.t. 1 h; (j) Wilkinson's catalyst, H2, THF−t-BuOH (1:1), r.t., 24 h; (k) conc. HCl, HOAc, 70 °C, 6 h; (l) EtOH, Na2CO3 (2 M), Pd(PPh3)4, toluene, reflux, 18 h; (m) p-toluenesulfonic acid, MeOH, 40 °C, 4 h; (n) K2CO3, DMF, r.t., 24 h; (o) Pd/C (10%), 1 bar H2, THF, r.t., 4 h; (p) NaNO3 (1.2 M in H2O), NaHSO3 (1.0 M in H2O), EtOH−HOAc (5:4), r.t., 3 h; (q) BBr3 (1 M in CH2Cl2), CH2Cl2, −78 °C, then r.t., 1 h.

Ring C was developed from commercially available 3-hydroxy-4-methoxybenzaldehyde (5). Protection of the phenol moiety with chloromethyl methyl ether yielded compound 6.21 Units 4 and 6 were coupled with a Wittig reaction in the presence of K2CO3 and 18-crown-6 to give the D−C segment 7 (obtained as an E/Z mixture in a ratio of 1:1),22 which was hydrogenated over Pd/C to give the bibenzyl 8. The deprotected hydroxy group in 8 was then converted to the corresponding triflate in 9, which underwent a PdCl2(dppf) mediated conversion to the pinacolboronate ester 10, produced in 62% overall yield from 5.23

The synthesis of the second bibenzyl sub-unit (16) began with commercially available 4-fluorobenzaldehyde (11), corresponding to ring A. Compound 11 was nitrated to yield compound 12, which was linked with phosphonium salt 4 by using a Wittig reaction to give the A−B segment 13 (obtained as an E/Z mixture in a ratio of 7:1).22 The double bond of each isomer was reduced with Wilkinson's catalyst to afford a single compound 14; the benzyl ether was retained under the mild hydrogenation conditions.24 Subsequently, O-debenzylation was accomplished using concentrated HCl in HOAc to yield compound 15,18 and the free hydroxyl group was then converted to a triflate in 16.23

The triflate 16 and the pinacolboronate ester 10 were combined via a aryl-aryl bond between rings B and D by using the Suzuki-Miyaura coupling reaction to afford 17, followed by deprotection of the phenol methoxymethyl ether using p-toluenesulfonic acid. Macrocyclization to give 19 was achieved in 89% yield through an intramolecular SNAr reaction using K2CO3 in DMF at room temperature. Next, the nitro group was removed in a two-step sequence of reduction and deamination18 to give plagiochin trimethyl ether (21). Plagiochin G (22) was finally obtained after cleavage of the methyl ethers.11, 26

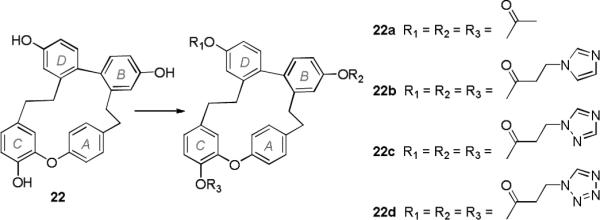

The acetyl ester derivative 22a was prepared by reaction of 22 with acetyl chloride and Et3N in CH2Cl2 with DMAP as a catalyst. Derivatives 22b−22d were synthesized from 22 by esterification with 3-(1H-imidazol-1-yl)propanoic acid, 3-(1H-1,2,4-triazol-1-yl)propanoic acid, and 3-(1H-tetrazol-1-yl)propanoic acid, respectively (Scheme 3).

Scheme 3.

Syntheses of ester derivatives of plagiochin G. Reagents and conditions: (22a) acetyl chloride, Et3N, DMAP, CH2Cl2, r.t., 1 h; (22b/22c/22d) 3-(1H-imidazol-1-yl)propanoic acid/3-(1H-1,2,4-triazol-1-yl)propanoic acid/3-(1H-tetrazol-1-yl)propanoic acid, EDCI, DMAP, CH2Cl2, r.t. 4 h.

Biological evaluation

To evaluate the cancer chemoprevention effects of compounds (19−22 and 22a−22d) in vitro, we assayed the eight compounds for inhibition of EBV-EA activation.27 Glycyrrhetic acid was used as a positive control. In this assay, all tested compounds showed inhibitory effects toward EBV-EA activation without cytotoxicity to Raji cells. As shown in Table 1, plagiochin G (22) exhibited the highest potency with 88%, 45%, and 19% inhibition at 1 × 103, 5 × 102, 1× 102 mol ratio/TPA, respectively, and IC50 value of 481 μM, with highly preserved viability of Raji cells. The four ester derivatives (22a−22d) showed similar inhibitory effects, while the three synthetic precursors (19−21) of 22 were comparably or slightly less potent.

Table 1.

Relative ratioa of EBV-EA activation with respect to positive control (100%) in the presence of 22 and related compounds

| Compound | Compound concentration (mol ratio/TPAb) |

IC50c (μM) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1000 | 500 | 100 | 10 | ||

| 19 | 14.9 ± 0.5 | 58.2 ± 0.7 | 83.1 ± 2.4 | 100 ± 0.5 | 491 |

| 20 | 15.3 ± 0.4 (70) | 59.6 ± 0.6 | 84.6 ± 2.3 | 100 ± 0.4 | 500 |

| 21 | 13.0 ± 0.5 (70) | 56.8 ± 0.5 | 81.1 ± 2.5 | 100 ± 0.5 | 490 |

| 22 | 11.5 ± 0.6 (70) | 54.3 ± 0.6 | 80.1 ± 2.3 | 100 ± 0.5 | 481 |

| 22a | 13.9 ± 0.5 (70) | 57.9 ± 0.5 | 82.4 ± 2.5 | 100 ± 0.6 | 495 |

| 22b | 13.0 ± 0.4 (60) | 55.4 ± 1.5 | 79.1 ± 2.3 | 100 ± 0.5 | 479 |

| 22c | 13.8 ± 0.5 (60) | 56.0 ± 1.6 | 80.0 ± 2.5 | 100 ± 0.3 | 482 |

| 22d | 14.0 ± 0.5 (60) | 57.6 ± 1.4 | 81.6 ± 2.4 | 100 ± 0.5 | 488 |

| Glycyrrhetic acide | 7.4 ± 0.5 (60) | 35.7 ± 0.8 | 83.2 ± 2.0 | 100 ± 0.3 | 413 |

Values represent percentages relative to the positive control value (100%).

TPA concentration is 20 ng/mL (32 pmol/mL).

The molar ratio of compound, relative to TPA, required to inhibit 50% of the positive control activated with 32 pmol TPA.

d Values in parentheses are viability percentages of Raji cells. In all other experiments, viability was >80%.

Positive control.

Conclusions

In this study, a new and efficient total synthesis of 22 and four ester derivatives (22a−22d) was successfully accomplished in 12−16 steps. An intramolecular SNAr reaction was used for the formation of the 16-membered ring. All tested synthetic macrocyclic bisbibenzyls exhibited potential cancer chemopreventive activity as evaluated by an EBV-EA activation assay. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report of macrocyclic bisbibenzyls with cancer chemopreventive activity. The new synthetic route reported herein is an additional effective strategy to construct variously substituted macrocyclic bisbibenzyls and should greatly facilitate our further synthesis and SAR study of cancer-preventative derivatives of 22.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81172956) and by NIH grant CA177584 from the National Cancer Institute awarded to K.H. Lee.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data (experimental section and spectroscopic data) associated with this article can be found, in the online version.

Reference and notes

- 1.Gravitz L. Nature. 2011;471:S5. doi: 10.1038/471S5a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ito Y, Yanase S, Fujita J, Harayama T, Takashima M, Imanaka H. Cancer Lett. 1981;13:29. doi: 10.1016/0304-3835(81)90083-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Itoigawa M, Ito C, Tokuda H, Enjo F, Nishino H, Furukawa H. Cancer Lett. 2004;214:165. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2004.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Suzuki M, Nakagawa-Goto K, Nakamura S, Tokuda H, Morris-Natschke SL, Kozuka M, Nishino H, Lee K-H. Pharm Biol. 2006;44:178. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Asakawa Y. Chemical Constituents of the Hepaticae. Springer; p. 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Asakawa Y, Heidelberger M, Herz W, Zechmeister L. Progress in the Chemistry of Organic Natural Products: Fortschritte der Chemie Organischer Naturstoffe. Springer-Verlag; p. 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Asakawa Y. Chemical Constituents of the Bryophytes. Springer; p. 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harrowven DC, Kostiuk SL. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2012;29:223. doi: 10.1039/c1np00080b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Asakawa Y, Matsuda R. Phytochemistry. 1982;21:2143. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hashimoto T, Tori M, Asakawa Y, Fukazawa Y. Tetrahedron Lett. 1987;28:6295. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Speicher A, Groh M, Hennrich M, Huynh A-M. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2010;2010:6760. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Keseru GM, Mezey-Vandor G, Nogradi M, Vermes B, Kajtar-Peredy M. Tetrahedron. 1992;48:913. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fukuyama Y, Yaso H, Mori T, Takahashi H, Minami H, Kodama M. Heterocycles. 2001;54:259. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fukuyama Y, Yaso H, Nakamura K, Kodama M. Tetrahedron Lett. 1999;40:105. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Niu C, Qu J-B, Lou H-X. Chem. Biodivers. 2006;3:34. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.200690004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Speicher A, Groh M, Zapp J, Schaumlöffel A, Knauer M, Bringmann G. Synlett. 2009;2009:1852. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Toyota M, Nagashima F, Asakawa Y. Phytochemistry. 1988;27:2603. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cortes Morales JC, Guillen Torres A, Gonzalez-Zamora E. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2011:3165. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jiang J, Sun B, Wang YY, Cui M, Zhang L, Cui CZ, Wang YF, Liu XG, Lou HX. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2012;20:2382. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2012.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhu J. Synlett. 1997;1997:133. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oh JH, Kim SJ, Kim JH, Shin DH. US20100143843A1. 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boden RM. Synthesis. 1975;1975:784. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thompson AL, Kabalka GW, Akula MR, Huffman JW. Synthesis. 2005:547. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jourdant A, González-Zamora E, Zhu J. J. Org. Chem. 2002;67:3163. doi: 10.1021/jo025595q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Konoshima T, Konishi T, Takasaki M, Yamazoe K, Tokuda H. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2001;24:1440. doi: 10.1248/bpb.24.1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schaumlöffel A, Groh M, Knauer M, Speicher A, Bringmann G. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2012;2012:6878. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Inhibition of EBV-EA activation assay. Inhibition of EBV-EA activation was assayed using Raji cells (virus nonproducer type), an EBV genome-carrying human lymphoblastoid cell, which were cultivated in 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) RPMI 1640 medium. The indicator cells (Raji, 1 × 106/mL) were incubated at 37°C for 48 h in 1 mL of medium containing n-butyric acid (4 mM as trigger), TPA (32 pM = 20 ng in 2 μL of DMSO as inducer), and various amounts of the test compounds dissolved in 5 μL of DMSO (ca. 0.7% DMSO). Smears were made from the cell suspension. The EBV-EA inducing cells were stained with high titer EBV-EA positive serum from NPC patients and detected by an indirect immunofluorescence technique.25 In each assay, at least 500 cells were counted, and the number of stained cells (positive cells) was recorded. Triplicate assays were performed for each data point. The average EBV-EA induction of the test compound was expressed as IC50 value and as a relative ratio to the positive control experiment (100%), which was carried out with n-butyric acid (4 mM) plus TPA (32 pM). In the experiments, the EBV-EA induction was normally around 35%, and this value was taken as the positive control (100%). n-Butyric acid (4 mM) alone induced 0.1% EA-positive cells. The viability of treated Raji cells was assayed by the trypan blue staining method. The cell viability of the TPA positive control was greater than 80%. Therefore, only the compounds that induced less than 80% (% of control) of the EBV-activated cells (those with a cell viability of more than 60%) were considered able to inhibit the activation caused by promoter substances. Student's t-test was used for all statistical analyses.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.