Abstract

Objectives:

Dolutegravir (DTG) has been studied in three trials in HIV treatment-naive participants, showing noninferiority compared with raltegravir (RAL), and superiority compared with efavirenz and ritonavir-boosted darunavir. We explored factors that predicted treatment success, the consistency of observed treatment differences across subgroups and the impact of NRTI backbone on treatment outcome.

Design:

Retrospective exploratory analyses of data from three large, randomized, international comparative trials: SPRING-2, SINGLE, and FLAMINGO.

Methods:

We examined the efficacy of DTG in HIV-infected participants with respect to relevant demographic and HIV-1-related baseline characteristics using the primary efficacy endpoint from the studies (FDA snapshot) and secondary endpoints that examine specific elements of treatment response. Regression models were used to analyze pooled data from all three studies.

Results:

Snapshot response was affected by age, hepatitis co-infection, HIV risk factor, baseline CD4+ cell count, and HIV-1 RNA and by third agent. Differences between DTG and other third agents were generally consistent across these subgroups. There was no evidence of a difference in snapshot response between abacavir/lamivudine (ABC/3TC) and tenofovir/emtricitabine (TDF/FTC) overall [ABC/3TC 86%, TDF/FTC 85%, difference 1.1%, confidence interval (CI) −1.8, 4.0 percentage points, P = 0.61] or at high viral loads (difference −2.5, 95% CI −8.9, 3.8 percentage points, P = 0.42).

Conclusions:

DTG is a once-daily, unboosted integrase inhibitor that is effective in combination with either ABC/3TC or TDF/FTC for first-line antiretroviral therapy in HIV-positive individuals with a variety of baseline characteristics.

Keywords: dolutegravir, integrase, subgroup, treatment efficacy, treatment-naive

Introduction

Once-daily (q.d.) dolutegravir (DTG) 50 mg in combination with abacavir/lamivudine (ABC/3TC) or tenofovir/emtricitabine (TDF/FTC) is the most recent addition to the list of regimens recommended for treatment-naive HIV-positive individuals [1].

Individual characteristics such as sex, age, race, chronic hepatitis co-infection, and HIV stage, as well as baseline CD4+ cell counts and HIV-1 RNA, can influence the efficacy and tolerability of antiretroviral therapy (ART) [2–5]. We examined the efficacy of DTG across baseline characteristics in HIV-infected individuals participating in three phase III studies [6–9]. In particular, we further examined the relationship between baseline viral load, nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NRTI) backbone, and virologic response.

Methods

Detailed methodology for SPRING-2 (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT01227824), SINGLE (NCT01263015), and FLAMINGO (NCT01449929) has been reported previously [6–8]. In brief, SPRING-2 (N = 822) compared DTG to raltegravir (RAL), SINGLE (N = 833) compared DTG + ABC/3TC to efavirenz (EFV)/TDF/FTC, and FLAMINGO (N = 484) compared DTG to darunavir/ritonavir (DRV/r). SPRING-2 and FLAMINGO used investigator-selected nucleosides (ABC/3TC or TDF/FTC). SPRING-2 and SINGLE were double-blind studies, and virologic failure was defined as confirmed HIV-1 RNA at least 50 copies/ml on or after week 24; FLAMINGO was open-label and its threshold for virologic failure was plasma HIV-1 RNA above 200 copies/ml.

The primary endpoint for each study was the proportion of individuals with plasma HIV-1 RNA below 50 copies/ml at week 48, as codified by the Food and Drug Administration snapshot algorithm [10].

Each study also examined time to treatment or to efficacy-related discontinuation or failure (TRDF and ERDF). The TRDF analysis calculated the time to protocol-defined virologic failure or discontinuation at any time for treatment-related reasons, such as drug-related adverse events, protocol-defined safety stopping criteria, or lack of efficacy. Participants who discontinued for reasons unrelated to treatment were censored at the time of discontinuation. In the ERDF analysis, censoring applied to discontinuations for reasons unrelated to efficacy. Analyses of these secondary endpoints allowed us to assess the impact of each risk factor on the three constituents of the snapshot response (virologic response, tolerability, and administrative dropout).

We examined consistency of primary endpoint treatment differences within each study according to baseline HIV-1 viral load and NRTI backbone, CD4+ cell count, sex, baseline age (<36 or ≥36 years), and race (white or African American/African heritage). We explored the impact of subgroups in a pooled dataset using multivariate binomial regression. For any factor associated with prognosis, we also used the regression model to test whether the effect of DTG was consistent across different levels of that factor.

Cox regression [11] was used to explore the effect of each factor on time to TRDF or ERDF.

All regression models were chosen using stepwise selection with Akaike's information criterion (AIC) [12].

Results

The analysis included data for all 2139 participants from the primary analyses of the individual studies. Baseline characteristics and primary efficacy results have been reported previously [6–8]. Table 1 presents the overall efficacy results (TRDF and ERDF rates) at week 48. In SINGLE and FLAMINGO studies, there was a statistically significant difference in the primary endpoint in favor of DTG [7,8]. A statistically significant difference persisted for the proportion with TRDF in the SINGLE study. There was no significant difference between third agents in the proportion with ERDF.

Table 1.

Summary of efficacy endpoints in therapy-naive participants in phase III studies of dolutegravir.

| SPRING-2 (N = 822) | SINGLE (N = 833) | FLAMINGO (N = 484) | |

| Treatment-related discontinuation = failure | |||

| DTG | 386/411 (93%) | 391/414 (94%) | 238/242 (98%) |

| Comparator | 379/411 (92%) | 365/419 (87%) | 233/242 (96%) |

| Difference (CIa) | 1.2 (−2.6, 5.1) | 7.7 (3.6, 11.7) | 2.4 (−0.7, 5.4) |

| Efficacy-related discontinuation = failure | |||

| DTG | 391/411 (94%) | 396/414 (95%) | 240/242 (99%) |

| Comparator | 383/411 (93%) | 402/419 (95%) | 240/242 (99%) |

| Difference (CIa) | 1.5 (−2.1, 5.1) | 0.2 (−2.9, 3.3) | 0.2 (−1.7, 2.1) |

CI, confidence interval; DTG, dolutegravir.

aDifference based on Kaplan–Meier estimates; CI based on Greenwood's formula.

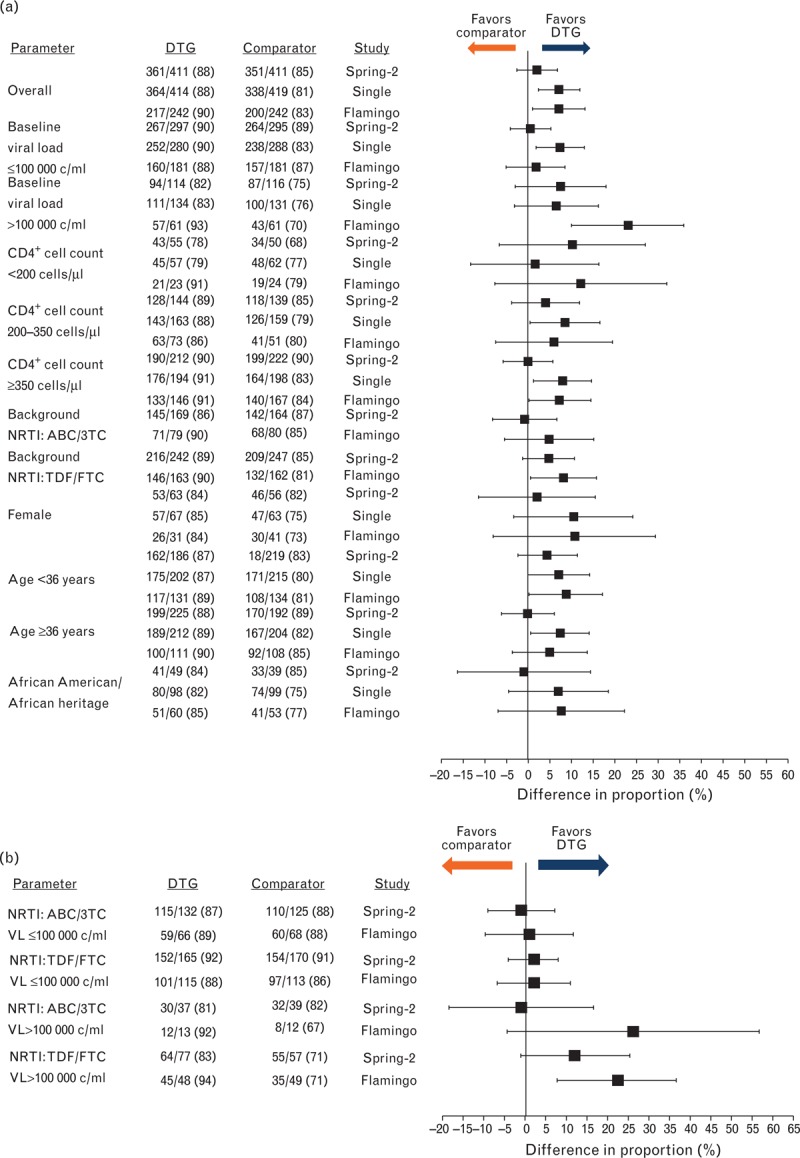

Figure 1a presents the snapshot response rates in each of the subgroups. The response rates for the DTG arms were generally consistent within each subgroup. For example, the response rates for women receiving DTG were between 84 and 85% in the three studies.

Fig. 1.

Snapshot response rates by subgroup in each study; (a) univariate and (b) bivariate summaries by baseline viral load and NRTI backbone.

Specific subgroups for male and white participants are omitted from (a): these subgroups comprised more than 75% of the study populations, and their results mirrored those in the overall population. ABC/3TC, abacavir/lamivudine; DTG, dolutegravir; NRTI, nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor; TDF/FTC, tenofovir/emtricitabine.

In each study, treatment differences between DTG and the comparator were generally consistent across subgroups. For example, in the SPRING-2 study, response rates for DTG and RAL were similar overall, as well as in both men and women; in the SINGLE study, the treatment difference favored DTG overall, as well as in both men and women.

The only notable case of inconsistency in treatment effects across subgroups was in the subgroup of participants in the FLAMINGO study with high viral load at baseline (n = 61 in each arm). In this subgroup, there was a particularly pronounced treatment difference. This was driven both by a higher response rate for those receiving DTG within this study subgroup (compared with the other two trials: 93% versus 83 and 82% in SINGLE and SPRING-2 study, respectively) and a lower response rate for those receiving the comparator (70% receiving DRV/r in FLAMINGO versus 76% receiving EFV/TDF/FTC in SINGLE and 75% receiving RAL in SPRING-2 study). Four participants in the FLAMINGO study experienced ERDF, two of whom had a baseline viral load above100 000 copies/ml: one of these individuals received DTG and the other received DRV/r.

Response in subgroups defined by sex or race should be interpreted with caution due to the small number of participants who were women or non-white. In each of these subgroups, confidence intervals (CIs) around treatment differences were wider than ±12 percentage points. A similar caveat applies to the interpretation of the differences seen in small subgroups defined by the combination of NRTI backbone and baseline viral load (Fig. 1b).

Regression analyses of the snapshot response, and time to TRDF and to ERDF used pooled data from all three studies and are presented in Table 2. The snapshot regression analyses were consistent with the primary analyses of the studies. These analyses revealed the significant effects of the treatment arm: DTG-treated individuals responded comparably with RAL-treated individuals, but significantly better when compared with DRV/r and EFV-treated individuals. Baseline viral load, CD4+ cell count, age, race, risk factor, and hepatitis co-infection were also significantly prognostic of response in these multivariate models (Table 2).

Table 2.

Significant factors in multivariable regression models of each endpoint.

| 1st endpoint: snapshot | 2nd endpoint: time to TRDF | 2nd endpoint: time to ERDF | ||||||||||||

| Effect | Group | Comparator | RD (% points) | CI | P | Pint | HR | 95% CI | P | Pint | HR | 95% CI | P | Pint |

| Age | ||||||||||||||

| ≥ 36 years | < 36 | 3.8 | (1.2, 6.5) | 0.005 | 0.80 | – | – | – | – | |||||

| Baseline viral load | ||||||||||||||

| > 100k | ≤ 100k | − 7.6 | (−11.2, − 4.1) | < 0.001 | 0.02 | 1.9 | (1.38, 2.69) | < 0.001 | 0.028 | 3.1 | (2.01, 4.92) | < 0.001 | 0.632 | |

| Race | ||||||||||||||

| White | Non-white | 4.3 | (0.7, 7.9) | 0.018 | 0.93 | – | – | – | – | |||||

| Third agent | ||||||||||||||

| DRV/r | DTG | − 5.0 | (−9.8, − 0.1) | 0.044 | NA | 2.4 | (0.73, 7.68) | 0.153 | NA | – | – | |||

| EFV | DTG | − 7.0 | (−11, − 3) | < 0.001 | 2.5 | (1.54, 4.08) | < 0.001 | – | – | |||||

| RAL | DTG | − 2.2 | (−5.7, 1.3) | 0.226 | 1.4 | (0.82, 2.29) | 0.223 | – | – | |||||

| CD4 + cell count (cells/μl) | ||||||||||||||

| 200 to < 350 | ≥ 350 | − 1.5 | (−4.5, 1.5) | 0.313 | 0.24 | 1.5 | (1.02, 2.15) | 0.039 | < 0.001 | 1.4 | (0.85, 2.44) | 0.177 | 0.801 | |

| < 200 | ≥ 350 | − 5.6 | (−10.9, − 0.2) | 0.041 | 2.3 | (1.47, 3.49) | < 0.001 | 3.5 | (2.03, 5.87) | < 0.001 | ||||

| Hepatitis coinfection | ||||||||||||||

| Hep B/C | Neither/missing | − 7.6 | (−14.4, − 0.8) | 0.028 | 0.36 | – | – | – | – | |||||

| Risk factor | ||||||||||||||

| Homosexual sex | Neither | 5.04 | (1.8, 8.3) | 0.002 | 0.88 | – | – | – | – | |||||

| IVDU | Neither | − 7.3 | (−18.6, 4) | 0.208 | – | – | – | – | ||||||

| Study | ||||||||||||||

| SINGLE | FLAMINGO | – | – | 3.0 | (1.03, 8.64) | 0.044 | NA | 4.3 | (1.51, 12.06) | 0.006 | NA | |||

| SPRING-2 | FLAMINGO | – | – | 3.5 | (1.22, 10.06) | 0.020 | 6.5 | (2.35, 18.06) | < 0.001 | |||||

DRV/r, darunavir/ritonavir; DTG, dolutegravir; EFV, efavirenz; HR, hazard ratio; IVDU, intravenous drug use; Pint, P value for an interaction between each covariate and treatment; RAL, raltegravir; RD, risk difference.

There was statistically significant evidence of a larger difference between DTG and comparator among participants with a higher viral load. This was attributable to the previously discussed finding in the FLAMINGO study among participants with high baseline viral load. There was no other evidence of inconsistency in snapshot treatment differences across other subgroups.

Pooled analyses revealed no significant difference in snapshot response between ABC/3TC and TDF/FTC overall (ABC/3TC 86%, TDF/FTC 85%, difference 1.1%, 95% CI −1.8, 4.0 percentage points, P = 0.61) or at high viral loads (difference −2.5, 95% CI −8.9, 3.8 percentage points, P = 0.42).

Baseline plasma HIV-1 RNA, CD4+ cell count, third agent (EFV only), and study were associated with time to TRDF. Treatment differences on this endpoint were not consistent across subgroups defined by baseline CD4+ cell count or HIV-1 RNA (P value for interaction <0.05). The Supplemental Digital Content shows Kaplan–Meier plots of time to TRDF by treatment and these factors. The difference in TRDF between DTG versus EFV was most pronounced in participants with high baseline CD4+ cell count and less pronounced in participants with low baseline CD4+ cell count. There was no suggestion of inconsistency across viral load strata after allowance for the CD4+ cell count effect.

There was no significant difference in time to TRDF between the NRTI backbones overall (hazard ratio 0.92, 95% CI 0.57–1.49, P = 0.74) or at high (hazard ratio 1.07, 95% CI 0.58–2.0, P = 0.83) baseline plasma HIV-1 RNA.

Participants with a baseline HIV-1 RNA above 100 000 copies/ml or a baseline CD4+ cell count below 200 cells/μl were at significantly greater risk of ERDF over time. Participants in the FLAMINGO study were less likely to experience virologic failure, largely due to the different virologic failure definition in this study. There was no suggestion of inconsistency of third-agent differences in time to ERDF.

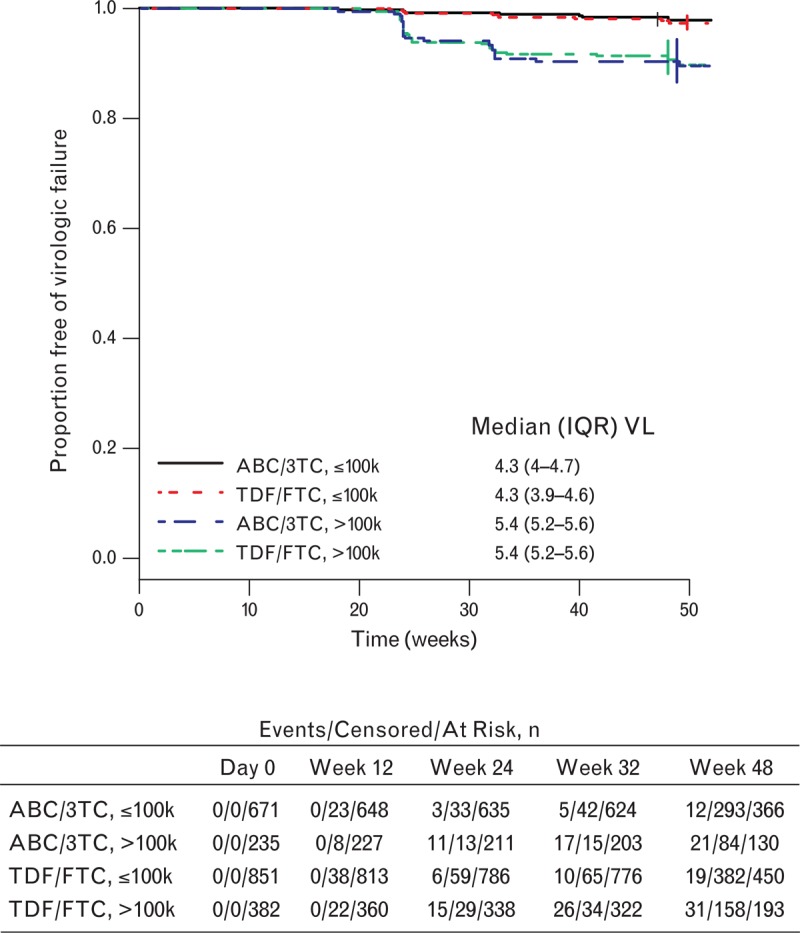

There was no significant difference in the likelihood of ERDF for participants receiving ABC/3TC compared with TDF/FTC overall (hazard ratio 0.90, 95% CI 0.58–1.38, P = 0.63) or at high (hazard ratio 0.95, 95% CI 0.55–1.65, P = 0.86) baseline HIV-1 RNA. This comparison of the NRTIs was supported by Kaplan–Meier curves of time to ERDF stratified by baseline viral load and NRTI (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Kaplan–Meier estimates of time to ERDF stratified by NRTI backbone and baseline plasma HIV-1 RNA (VL) (log10 copies/ml).

The number of events, censored events, and patients at selected intervals are noted below the graph. ABC/3TC, abacavir/lamivudine; IQR, interquartile range of baseline viral load; NRTI, nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor; TDF/FTC, tenofovir/emtricitabine; VL, viral load.

Discussion

Although three individual randomized studies have demonstrated high efficacy and favorable benefit–risk for DTG compared to RAL, EFV, or DRV/r for first-line ART, the sample size of these studies does not allow examination of individual characteristics that might affect virologic response or treatment outcome. By pooling data from more than 2000 clinical trial participants in these studies, we provide new and relevant clinical information on the efficacy of DTG across various treatment subgroups, including backbone NRTI.

The results of these exploratory subgroup analyses support the primary results from the three phase III studies – SPRING-2, SINGLE, and FLAMINGO [6–8].

Treatment differences were largely consistent across subgroups. There was no subgroup in which we observed a response rate for DTG that was significantly lower than that of another third agent. Some significant differences in favor of DTG were more pronounced in certain subgroups (e.g. high viral load in FLAMINGO study for the primary endpoint or TRDF for high CD4+ cell count in SINGLE study) and, by corollary, attenuated in complementary subgroups (low viral load in FLAMINGO study or low CD4+ cell count in SINGLE study). Since these findings were not observed consistently across studies or across endpoints within studies, they do not alter the overall conclusions about efficacy drawn from the studies. The efficacy of DTG versus standard-of-care comparators at week 48 was consistent in subgroups defined by sex, race, and age.

There was some variability in response that applied equally across all treatments. The principal prognostic factors for snapshot response (after third agent) were baseline plasma HIV-1 RNA, baseline CD4+ cell count, age, race, risk factor, and hepatitis co-infection. The effect of the principal factors was not always significant for endpoints that focused on components of the snapshot response. For example, only baseline viral load, CD4+ cell count, and study were predictive of both the time to TRDF endpoint and the purely virologic time to ERDF endpoint. The third agent was associated with time to TRDF, but not to ERDF.

Some studies have shown an association between NRTI backbone and probability of virologic response, including individuals with high baseline viral load [13]. This finding has not been uniformly replicated [14]. The analysis provided herein consisting of pooled data from three studies provides new data comparing ABC/3TC with TDF/FTC. This analysis showed no difference between the two NRTI backbones when coupled with the third agents studied in the SPRING-2, SINGLE, and FLAMINGO studies at low or high viral loads for the primary snapshot endpoint, the TRDF endpoint, and for a pure virologic ERDF endpoint. It is important to note that this comparison was not randomized. Therefore, biases cannot be excluded, in particular, channeling bias, whereby investigator preference for TDF/FTC in individuals with very high viral load could leave the hardest-to-treat participants on that NRTI backbone. However, it is worth noting that analyses of the distribution of baseline viral load by NRTI and viral load subgroup (Fig. 2) do not suggest that among participants with high baseline viral loads, the subgroup taking TDF/FTC had a greater proportion of participants with extremely high baseline viral loads than the subgroup taking ABC/3TC.

The survival analyses presented herein have statistical limitations: the exact time of virologic failure or loss to follow-up is not known precisely; the proportionality of hazards for Cox models cannot be assessed with great power across a number of strata when there are limited failures observed, largely, at a small number of scheduled visits; and the classification of individuals who drop out for reasons unrelated to treatment is problematic. Analyses of the snapshot endpoint share the last problem and ignore the time at which failure occurred. Our statistical models each make different statistical assumptions, but the main findings of this analysis were robust to the methods used.

In conclusion, the efficacy findings from the individual studies were largely consistent across subgroups, including baseline HIV-1 RNA, CD4+ cell count, sex, age, and race. Exploratory analyses did not suggest a difference in response between the NRTI backbones used in these studies. DTG is a q.d. integrase inhibitor without the need for pharmacokinetic boosting that can be used effectively in combination with either TDF/FTC or ABC/3TC in a wide variety of HIV-positive individuals for first-line ART.

Acknowledgements

Funding for this work was provided by ViiV Healthcare. The SPRING-2, SINGLE, and FLAMINGO studies were funded by ViiV Healthcare. All listed authors meet the criteria for authorship set forth by the International Committee for Medical Journal Editors. The authors wish to acknowledge the following individuals for editorial assistance during the development of this manuscript: J.L. Martin-Carpenter.

Author contributions: E.R. was an investigator for SPRING-2 and FLAMINGO studies, and participated in the drafting, critical review, and revision of the manuscript. A.R., Cy.B., and M.G. were investigators for SPRING-2 study and participated in the critical review and revision of the manuscript. J.E. and S.W. were investigators for SPRING-2, SINGLE, and FLAMINGO studies, and participated in the critical review and revision of the manuscript. K.A. was an investigator for SINGLE study, and participated in the critical review and revision of the manuscript. Cl.B. was the sponsor study lead for SPRING-2 and FLAMINGO studies, and K.P. was the sponsor study lead for SINGLE study; both participated in the critical review and revision of the manuscript. R.L.C., S.A., and C.G. conducted the statistical analysis and participated in the drafting, critical review, and revision of the manuscript. W.G.N. contributed to study design and data analysis, and participated in the critical review and revision of the manuscript. The data in this manuscript come from three different clinical trials; all authors were involved in the conduct of or data analysis for one or more of these trials. Therefore, we feel that the inclusion of more than 10 authors for this manuscript is justified. All authors have read and approved the text as submitted to AIDS.

Conflicts of interest

F.R. has received research support from Gilead Sciences, Merck and Tibotec, and consulting fees from Abbott, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead Sciences, GlaxoSmithKline, Janssen-Cilag, Merck, Roche, Schering-Plough, ViiV Healthcare, Theratechnologies and Avexa. A.R. has received honoraria for participation as a consultant, member of advisory boards and provision of continuing education, and has been an investigator in clinical trials for Bristol-Myers Squibb, Merck, Gilead Sciences, ViiV Healthcare, Pfizer, Abbott and Janssen. C.B. has received honoraria for participation as a consultant for Central Texas Clinical Research, for participation as a consultant and lecturer and service on speakers bureaus from Gilead Sciences, and support for travel, accommodations, and meeting expenses from Gilead Sciences that are not related to this study. K.A. has received honoraria for participation as a consultant, fees for participation in review activities such as data monitoring boards and statistical analysis, and support for travel for this study from ViiV Healthcare, and has been an investigator in clinical trials for GlaxoSmithKline. M.G. has received honoraria for participation as a consultant, member of advisory boards and provision of continuing education, and has been an investigator in clinical trials for Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead Sciences, ViiV Healthcare, Pfizer, Abbot, AstraZeneca and Janssen. J.E. Jr has received honoraria for participation as a consultant for Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead Sciences, ViiV Healthcare, Janssen, Abbott and Merck, and has been an investigator in clinical trials for Merck, Bristol-Myers Squibb and ViiV Healthcare. S.W. has served on advisory boards, participated in clinical trials and spoken at CME events for Merck, ViiV Healthcare, Bristol-Myers Squibb, AbbVie, Gilead Sciences and Jannsen.

C.B., K.P., S.A., and C.G. are employees of GSK. R.C. and W.G.N. are employees of ViiV Healthcare.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.US Department of Health and Human Services Panel on Antiretroviral Guidelines for Adults and Adolescents. Recommendation on integrase inhibitor use in antiretroviral treatment-naive HIV-infected individuals. http://aidsinfo.nih.gov/news/1392/hhs-panel-on-antiretroviral-guidelines-for-adults-and-adolescents-updates-recommendations-on-preferred-insti-based-regimens-for-art-naive-individuals [Accessed 16 December 2013] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Branas F, Berenguer J, Sanchez-Conde M, Lopez-Bernaldo de Quiros JC, Miralles P, Cosin J, et al. The eldest of older adults living with HIV: response and adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy. Am J Med 2008; 121:820–824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kumar PN, Rodriguez-French A, Thompson MA, Tashima KT, Averitt D, Wannamaker PG, et al. A prospective, 96-week study of the impact of Trizivir®, Combivir®/nelfinavir and lamivudine/stavudine/nelfinavir on lipids, metabolic parameters and efficacy in antiretroviral-naive patients: effect of sex and ethnicity. HIV Med 2006; 7:85–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tedaldi EM, Absalon J, Thomas AJ, Shlay JC, van den Berg-Wolf M. Ethnicity, race, and gender. Differences in serious adverse events among participants in an antiretroviral initiation trial: results of CPCRA 058 (FIRST Study). J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2008; 47:441–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rockstroh J, Teppler H, Zhao J, Sklar P, Harvey C, Strohmaier K, et al. Safety and efficacy of raltegravir in patients with HIV-1 and hepatitis B and/or C virus coinfection. HIV Med 2012; 13:127–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Raffi F, Rachlis A, Stellbrink H-J, Hardy WD, Torti C, Orkin C, et al. Once-daily dolutegravir versus raltegravir in antiretroviral-naive adults with HIV-1 infection: 48 week results from the randomised, double-blind, noninferiority SPRING-2 study. Lancet 2013; 381:735–743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walmsley SL, Antela A, Clumeck N, Duiculescu D, Eberhard A, Gutierrez F, et al. Dolutegravir plus abacavir-lamivudine for the treatment of HIV-1 infection. N Engl J Med 2013; 369:1807–1818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clotet B, Feinberg J, van Lunzen J, Khuong-Josses M-A, Antinori A, Dumitru I, et al. Once-daily dolutegravir versus darunavir plus ritonavir in antiretroviral-naive adults with HIV-1 infection (FLAMINGO): 48 week results from the randomised open-label phase 3b study. Lancet 2014; 383:2222–2231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raffi F, Jaeger H, Quiros-Roldan E, Albrecht H, Belonosova E, Gatell JM, et al. Once-daily dolutegravir versus twice-daily raltegravir in antiretroviral-naive adults with HIV-1 infection (SPRING-2 study): 96 week results from a randomised, double-blind, noninferiority trial. Lancet Infect Dis 2013; 13:927–935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.US Department of Health and Human Services. Guidance for Industry. Human immunodeficiency virus-1 infection: developing antiretroviral drugs for treatment. http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Guidances/UCM355128.pdf [Accessed 25 February 2014] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Therneau TM, Grambsch PM. Modeling survival data: extending the Cox model. New York: Springer; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Akaike H. Information theory and an extension of the maximum likelihood principle. In: Petrov BN, Csaki F, editors. Second international symposium on information theory. Budapest, Hungary: Akademiai Kiado; 1973. 267–281. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sax PE, Tierney C, Collier AC, Fischl MA, Mollan K, Peeples L, et al. Abacavir-lamivudine versus tenofovir-emtricitabine for initial HIV-1 therapy. N Engl J Med 2009; 361:2230–2240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith KY, Patel P, Fine D, Bellos N, Sloan L, Lackey P, et al. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-matched, multicenter trial of abacavir/lamivudine or tenofovir/emtricitabine with lopinavir/ritonavir for initial HIV treatment. AIDS 2009; 23:1547–1556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.