Abstract

Highly regulated expression of the negative co-stimulatory molecule CTLA-4 on T-cells modulates T-cell activation and proliferation. CTLA-4 is preferentially expressed in Th2 T-cells, whose differentiation depends on the transcriptional regulator GATA3. Sezary syndrome (SS) is a T-cell malignancy characterized by Th2 cytokine skewing, impaired T-cell responses, and over-expression of GATA3 and CTLA-4. GATA3 is regulated by phosphorylation and ubiquitination. In SS cells, we detected increased polyubiquitinated proteins and activated GATA3. We hypothesized that proteasome dysfunction in SS T cells may lead to GATA3, and CTLA-4 over-expression. To test this hypothesis, we blocked proteasome function with bortezomib in normal T-cells, and observed sustained GATA3 and CTLA-4 upregulation. The increased CTLA-4 was functionally inhibitory in a mixed lymphocyte reaction (MLR). GATA3 directly transactivated the CTLA-4 promoter, and knockdown of GATA3 mRNA and protein inhibited CTLA-4 induction mediated by bortezomib. Finally, knockdown of GATA3 in patient’s malignant T-cells suppressed CTLA-4 expression. Here we demonstrate a new T-cell regulatory pathway that directly links decreased proteasome degradation of GATA-3, CTLA-4 upregulation, and inhibition of T-cell responses. We also demonstrate the presence of the GATA3/CTLA-4 regulatory pathway in fresh neoplastic CD4+ T-cells. Targeting of this pathway may be beneficial in SS and other CTLA-4-overexpressing T-cell neoplasms.

INTRODUCTION

Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte antigen 4 (CTLA-4, CD152) is a T cell surface protein with homology to CD28 and binds with high affinity to the B7 family of costimulatory ligands (Boulougouris et al., 1998; Brunet et al., 1987; Carreno et al., 2000; Keilholz, 2008; Linsley et al., 1991; Linsley et al., 1992a; Linsley et al., 1992b; Teft et al., 2006; Waterhouse et al., 1996; Waterhouse et al., 1995). CTLA-4 functions by transmitting inhibitory signals to the nucleus and sequestering B7 molecules to control the proliferation of surrounding cells (Carreno et al., 2000; Oosterwegel et al., 1999). Additionally CTLA-4 plays a critical role in the regulation of T cells responses via its expression on regulatory T-cells (Treg) (Jonuleit et al., 2001; Takahashi et al., 2000). CTLA-4 knock-out mice develop a severe lymphoproliferative disorder and exhibit immune hyperactivation (Tivol et al., 1995; Waterhouse et al., 1995). Polymorphisms within the non-coding regions of the CTLA-4 gene leading to reduced mRNA levels have been linked to autoimmune diseases (Balic et al., 2009; Kavvoura et al., 2007; Lee et al., 2005).

Recent studies have shown that GATA3, a T-cell transcription factor, regulates Th2 T-cell differentiation (Cook and Miller, 2010; Hwang et al., 2010; Nakata et al., 2010; Yagi et al., 2011; Zhu, 2010), but its relationship with CTLA-4 is unclear. CTLA-4 has been shown to be increased in normal Th2 T cells and in malignant T-cells from Sezary syndrome (SS), a type of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL) with a Th2-bias (Chong et al., 2008; Hahtola et al., 2006; Nebozhyn et al., 2006; Wong et al., 2006). This raises the hypothesis that in SS and other mature CD4+ T cell malignancies, increased expression of CTLA-4, and Th2 cytokine skewing may be due to aberrant or dysregulated expression of GATA3. GATA3 is highly regulated by post-translational mechanisms and has been shown to be modulated by the proteasome pathway and by phosphorylation (Yamashita et al., 2005). We have previously shown an important role of the NFAT1 transcription factor in the regulation of CTLA-4 expression in normal T cells (Gibson et al., 2007). However, we hypothesize that additional transcription factors and regulatory pathways likely play a role in the induction and expression of CTLA-4.

In this report, we present evidence showing that GATA3 regulates CTLA-4 expression and suggest that the proteasome pathway plays an important role in GATA3 regulation. We also demonstrate that SS T-cells have increased levels of polyubiquinated proteins compared to normal T-cells and higher levels of GATA3, suggesting that abnormal proteasome regulation of GATA3 may provide a mechanism for the increased CTLA-4 expression in SS. To test this hypothesis, we inhibited proteasome function in normal T-cells with bortezomib and observed sustained expression of CTLA-4 in normal CD4+ T-cells, mimicking the expression pattern observed in SS. The increased CTLA-4 resulting from bortezomib-mediated proteasome dysfunction is paralleled by increased GATA3 expression. Furthermore, we demonstrate that GATA3 can transactivate the CTLA-4 promoter and is directly involved in the regulation of CTLA-4 transcription in normal CD4+ T-cells. Knockdown of GATA3 decreased bortezomib-induced CTLA-4 expression. Taken together, this work introduces a new mechanism for CTLA-4 regulation in SS T-cells and provides a potential mechanistic link between the abnormal expression of GATA3 and increased CTLA-4 expression.

RESULTS

CTLA-4 and GATA3 expression is increased in Sezary syndrome (SS) T-cells

To study the role of GATA3 in regulating CTLA-4 expression, levels of GATA3 and CTLA-4 were measured in total RNA isolated from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) from patients with SS and controls (normal, healthy donors and psoriasis patients). CTLA-4 expression was stimulated with PMA/A23187, direct activators of cytoplasmic T cell signaling pathways that bypass defective surface signaling (Wong et al., 2006). From qRT-PCR analysis, CTLA-4 transcription in SS samples was induced to a level that was higher than normal PBMCs (Figure 1a). Expression of CTLA-4 in PBMCs from psoriasis was similar to normal controls, suggesting that increased CTLA-4 expression in Sezary cells was independent of chronic T-cell activation secondary to inflammation.

Figure 1. Sezary cells show dysregulation of CTLA-4, GATA-3 and proteasome activity relative to psoriasis and normal controls.

(A) CTLA-4 and (B) GATA3 mRNA levels are increased in PBMCs isolated from Sezary patients (triangles, n=6) relative to psoriasis (squares, n=6) and normal (diamonds, n=6) controls that were stimulated with PMA/A23187 for the indicated time points as measured by qRT-PCR. Results are shown as the average fold increase over unstimulated normal cells ± SEM (* p < 0.05). (C) Immunoblot analysis of purified CD4+ T cell lysates from unstimulated normal donor (n = 2) CD4+ T cells and Sezary (n = 5) patients using antibodies to probe for total GATA3, phospho-GATA3, total ubiquitin, and actin, as described in the Materials and Methods.

Consistent with previous reports (Nebozhyn et al., 2006), qRT-PCR showed that GATA3 transcript was increased significantly in SS PBMCs, both at rest and following stimulation (p< 0.005, Figure 1b). Immunoblot analysis of GATA3 protein levels in whole-cell extracts from unstimulated PBMCs of SS patients (n=5) confirmed a correlation between GATA3 protein levels and increased GATA3 transcription (Figure 1c, top panel). Additionally, we also measured the level of phospho-GATA3 (p-GATA3), the transcriptionally active form, which has been suggested to play a role in CTLA-4 expression in normal T cells (Yamashita et al., 2005). We found that total protein extract from SS patients showed an increase in the level of p-GATA3 compared to normal T cells (Figure 1c).

CTLA-4 has also been shown to be regulated by NFAT1 and FoxP3 (Gibson et al., 2007; Hori et al., 2003; Wu et al., 2006). However, analysis of NFAT1 and FoxP3 expression by qRT-PCR and immunoblot analysis did not reveal significant differences between SS and normal T cells (data not shown).

Although GATA3 has been shown to be regulated by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway (Yamashita et al., 2005), proteasome function has not been evaluated in SS. When total ubiquitin from whole cell extracts was measured by immunoblot, a significant increase in poly-ubiquinated proteins in SS cells compared to normal controls was measured (Figure 1c).

Proteasome inhibitor induces CTLA-4 expression

Increased levels of poly-ubiquitinated proteins in SS T-cells suggested that altered proteasome function might play a role in enhancing GATA3 and CTLA-4 expression. To determine whether proteasome dysfunction alone is sufficient to alter regulation of CTLA-4 in T cells, proteasome activity was inhibited in normal CD4+ T cells using bortezomib, a specific inhibitor of the 26S proteasome (Adams and Kauffman, 2004). Normal CD4+ T cells were stimulated with PMA/A23187 in the presence of 10 μM bortezomib, and surface-bound CTLA-4 was assessed by flow cytometry (Figure 2a). In bortezomib-treated CD4+ T cells, membrane-bound CTLA-4 was higher than in untreated CD4+ T cells (46.31% treated CD4+ vs. 13.32% untreated CD4+).

Figure 2. Proteasome inhibition with bortezomib augments CTLA-4 surface expression.

(A) Bortezomib increases CTLA-4 surface expression on normal primary CD4+ T cells after stimulation with 10 μM bortezomib (right panel) compared to untreated cells (left panel). Results are representative of at least 6 independent experiements. (B) CTLA-4 expression on PMA/A23187-stimulated normal primary T cells derived from a normal donor treated with 0 μM (red), 0.1 μM (green), and 10 μM (blue) of bortezomib over 3 to 12 h as assessed via flow cytometry. Results are representative of 4 independent experiments. (C) Summary of average CTLA-4 surface expression from the 4 individuals in (B) ± SEM in (B) (**p<0.005).

To study the kinetics of CTLA-4 expression following PMA/A23187 stimulation and bortezomib treatment, a time-course study was performed (Figures 2b and 2c). Untreated CD4+ T cells exhibited a peak in CTLA-4 expression between 3 to 6 h after stimulation, with a subsequent rapid decline in CTLA-4. Incubation with bortezomib led to a sustained higher level of CTLA-4 expression that persisted beyond 12 h after stimulation (Figure 2b and 2c). Another proteasome inhibitor, ALLN, mediated an equivalent increase in CTLA-4 expression (data not shown) and demonstrated that the effect is not from non-specific property of bortezomib and is from modulation of the proteasome pathway.

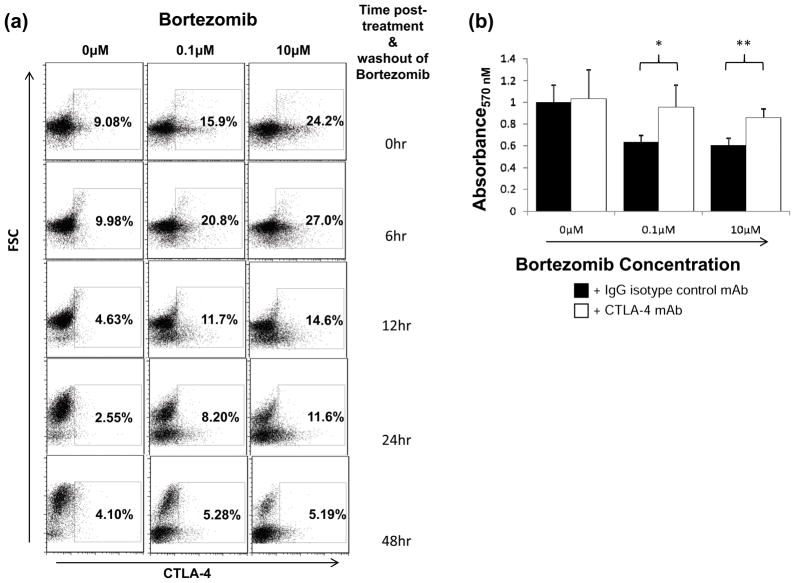

Bortezomib-induced CTLA-4 expression suppresses T cell proliferation

To determine whether increased surface CTLA-4 in bortezomib-treated cells could functionally suppress T cell proliferation, a mixed lymphocyte reaction (MLR) was performed. Purified CD4+ T cells were incubated for 9 h with 0, 0.1 and 10 μM of bortezomib and PMA/A23187 followed by washing, which resulted in 9.1%, 15.9% and 24.2% CTLA-4 expression, respectively. Although CTLA-4 expression diminished within 12 h without bortezomib or PMA/A23187, CTLA-4 expression remained elevated in 11.6% of cells at the 10 μM bortezomib-treated population after 24 h (Figure 3a). In MLR assays, the bortezomib-treated cells suppressed proliferation more effectively than untreated cells (Figure 3b). Culturing with anti-CTLA-4 blocking antibody increased proliferation in bortezomib-treated samples, while samples without bortezomib were unaffected, confirming a CTLA-4 specific, bortezomib-dependent mechanism.

Figure 3. Elevated CTLA-4 with bortezomib suppresses T cell proliferation.

(A) Primary CD4+ T cells were isolated and treated with 0, 0.1 and 10 μM bortezomib concomitant with PMA/A23187 stimulation over a 9 h incubation. Cells were washed 3x and returned to culture media without bortezomib or PMA/A23187. CTLA-4 levels were measured at the indicated time points. (B) Bortezomib-treated (0.1 μM and 10 μM) CD4+ cells expressing higher levels of CTLA-4 better suppress proliferation compared to untreated cells (0 μM) expressing lower levels of CTLA-4. Washed cells were plated at 5x104/well of a 96-well plate and stimulated with an equal amount of mytomycin C-treated allogenic PBMCs as detailed in the Materials and Methods. Samples were supplemented with 0.5 μg IgG control (black bars) or CTLA-4 blocking antibody (white bars). After 7 days, proliferation was measured by the MTS assay as described in Materials and Methods, and proliferation was measured via absorbance at 570 nM. Results are presented as the averages of quintuplicate samples ± SEM and are representative of three independent experiments (**p<0.005).

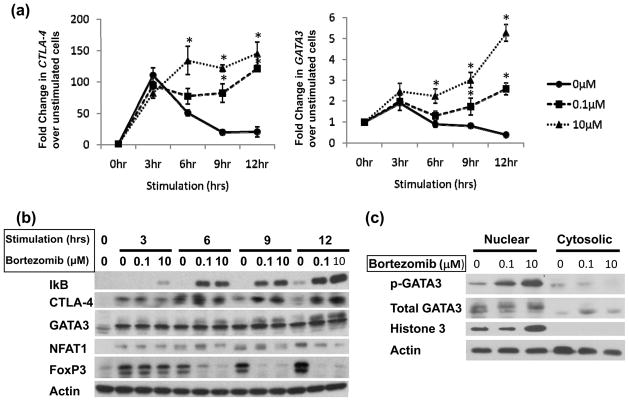

Proteasome inhibition leads to increased CTLA-4 and GATA3 transcription

To study the effect of bortezomib-induced proteasome dysfunction on CTLA-4 and GATA3 transcription, qRT-PCR was performed to measure mRNA levels in stimulated cells in the presence and absence of bortezomib (Figure 4a). While CTLA-4 expression peaked 3 h after stimulation in bortezomib-untreated CD4+ T-cells, expression in bortezomib pretreatment at various concentrations (0, 05uM, 1 uM, 5uM, and 10μM) led to CTLA-4 increase that peaked 12 h after simulation (Supplementary Figure 1). This paralleled the GATA3 gene expression profile and was consistent with a previous report (Yamashita et al., 2005). When the mRNAs for other transcription factors reported to participate in CTLA-4 expression were analyzed (Gibson et al., 2007; Wu et al., 2006), neither NFAT1 nor FoxP3 expression differed in the presence of bortezomib (Supplemental Figure 2a,b).

Figure 4. Bortezomib differentially regulates T cell transcription factor expression.

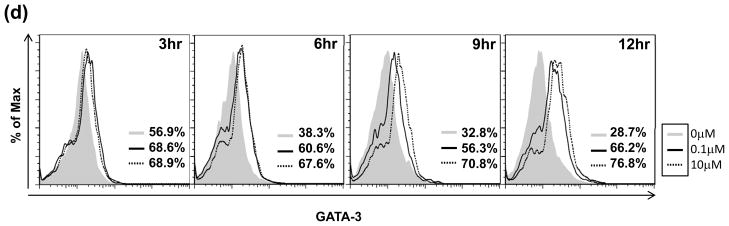

(A) Transcript levels of CTLA-4 (left panel) and GATA3 (right panel) are increased with bortezomib. Normal primary CD4+ T cells were purified as described in Materials and Methods followed by treatment with bortezomib (0.1 μM, dashed line with square; 10 μM, dotted line with triangle) or untreated (solid line with circle) and concomitant stimulation with PMA/A23187 over a 12 h time course. Total RNA was isolated for qRT-PCR analysis as previously described. Results are the averages of 4 individual normal donors analyzed by qPCR normalized to B2M and presented as the fold increase over unstimulated normal cells ± SEM *p<0.05, **p<0.005. (B) Immunoblot analysis of lysates of normal CD4+ T cells stimulated in a time course with PMA/A23187 and treated with bortezomib for CTLA-4, GATA3, NFAT1 and FOXP3. Results are representative of 3 independent experiments. (C) Phospho-GATA3 levels increase with bortezomib. Nuclear and cytosolic fractions were isolated from primary CD4+ T cells following treatment with 0, 0.1 and 10 μM of bortezomib and stimulation for 6 h with PMA/A23187. (D) Intracellular flow analysis of total GATA3 levels after treatment and stimulation as in (A) show that GATA3 remains elevated 12 h after bortezomib treatment and stimulation Results are representative of 3 independent experiments.

T-cell transcription factors are differentially regulated by proteasome inhibition

To investigate whether proteasome inhibition affected the protein stability of NFAT1, FoxP3 or GATA3, whole-cell lysates from normal CD4+ T cells were analyzed by immunoblot (Figure 4b). IκB served as a control to monitor the efficiency of proteasome inhibition. Consistent with flow cytometry analyses of surface-bound CTLA-4, bortezomib induced a sustained increase in CTLA-4 protein expression at each time point. NFAT1 protein was not increased with bortezomib, but at high bortezomib concentrations, a modest reduction was observed. Untreated samples showed enhanced FoxP3 expression over the time course, but expression was abrogated with bortezomib (Figure 4b).

After prolonged stimulation in the presence of bortezomib, a higher molecular weight species of GATA3 appeared, suggesting post-translational modification (Figure 4b). GATA3 has been shown to be regulated by phosphorylation to form the transcriptionally active protein (Maneechotesuwan et al., 2007). To confirm the nature of the higher molecular weight band, nuclear and cytosolic fractions were isolated from T cells stimulated for 6 h after treatment with bortezomib. When analyzed for phospho(p)-S308 GATA3 by immunoblots (Figure 4c), a significant band corresponding to p-S308 GATA3 was detected after bortezomib treatment in the nuclear fraction that was greater than the corresponding level in the cytosolic fractions. Total histone H3 immunoblot served as a control to confirm the efficiency of isolating nuclear and cytosolic fractions. Finally, intracellular flow analysis of total GATA3 levels in stimulated cells after bortezomib treatment confirmed that GATA3 remained elevated 12 h after bortezomib treatment and stimulation (Figure 4d).

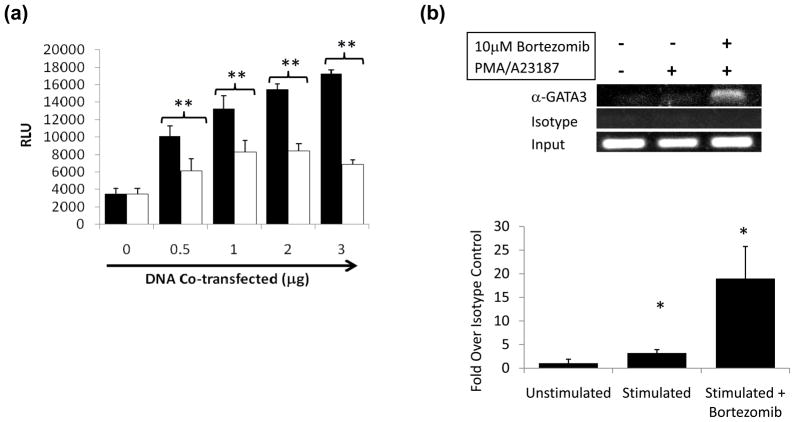

GATA3 enhances CTLA-4 expression through interaction with the proximal promoter

To address whether GATA3 can directly affect CTLA-4 transcription, a CTLA-4 promoter reporter assay was performed by co-transfecting a GATA3 expression vector with luciferase reporter plasmids (pGL3) containing the proximal CTLA-4 promoter into Jurkat T cells (Gibson et al., 2007). Co-transfection of increasing amounts of GATA3 plasmid led to a dose-dependent increase in CTLA-4 reporter gene activity using a pGL3 construct with 380 bp of the proximal CTLA-4 promoter (p<0.005, Figure 5a). Similar results were obtained with a 1kb CTLA-4 pGL3 promoter reporter construct (data not shown). Co-transfection of GATA3 with the SV40 pGL3 control vector or a promoterless vector did not increase luciferase activity, demonstrating that the effect is CTLA-4-specific (data not shown).

Figure 5. GATA3 associates with and enhances activity of the proximal CTLA-4 promoter.

(A) GATA3 stimulates the CTLA-4 promoter in a transient transfection assay. A 380 bp CTLA-4 promoter luciferase construct (Gibson et al., 2007) was cotransfected with increasing concentrations of plasmid containing GATA3 (black bars) or vector control sequence (white bars) into Jurkat cells using Lipofectin as described in Materials and Methods. Luciferase assay was performed, and relative light units (RLU) were calculated. Results are averages of 3 independent experiments ± SEM (**p<0.005). (B) GATA3 associates with the CTLA-4 promoter. ChIP was performed with antibodies to GATA3 and an isotype control (top and middle panel, respectively). Input DNA is also shown (bottom panel). Crosslinks were reversed, and the DNA was purified for amplification with primers spanning the CTLA-4 promoter, and PCR products were electrophoresed on an agarose gel.

To determine whether GATA3 interacts with the endogenous CTLA-4 promoter in primary T cells, we performed chromatin immunoprecipitation assays (ChIP). Using an antibody to GATA3, we co-immunoprecipitated the CTLA-4 promoter in the presence of bortezomib (Figure 5b). This suggests that GATA3 interacts with the CTLA-4 promoter in vivo.

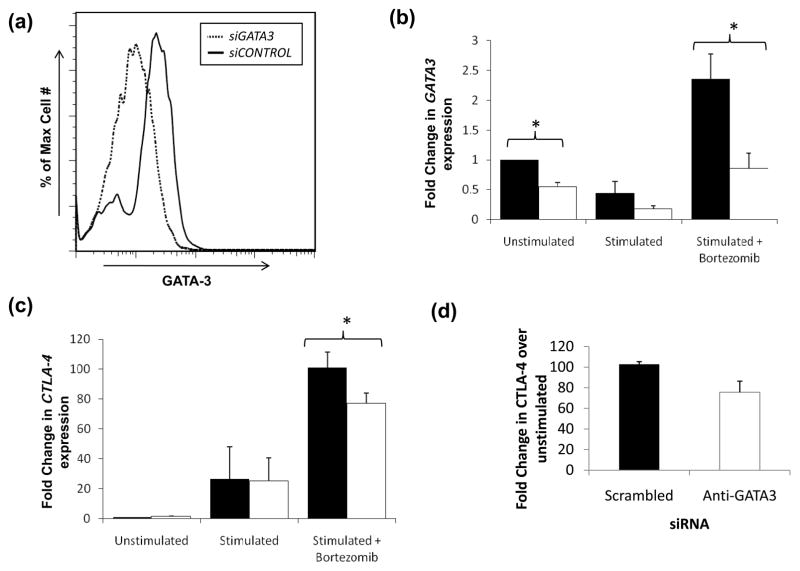

Targeting of GATA3 by siRNA suppresses CTLA-4 transcription

To verify the role of GATA3 in CTLA-4 expression in bortezomib-treated CD4+ T cells, we targeted GATA3 expression with siRNA. Primary CD4+ T-cells were nucleoporated with GATA3-specific or control scrambled siRNA, rested for 18 h, then stimulated in the presence or absence of 10 μM bortezomib for 9 h. GATA3 expression was reduced by approximately 50% with targeted siRNA at both the mRNA and protein levels (Figure 6a and 6b). In these experiments, transcript levels of CTLA-4 in bortezomib-treated cells were diminished by 23.6% when GATA3 was depleted (P<0.05) but not with stimulation alone (Figure 6c). IL-4, a GATA3-dependent gene, served as control and was reduced consistently (average of 40.9%, p<0.05) by mRNA qRT-PCR (Supplementary Figure 3a). Expression of the internal control GAPDH was unaffected by GATA3-specific siRNA in the same samples (Supplementary Figure 3b).

Figure 6. GATA3 knockdown by siRNA leads to decreased CTLA-4 transcription.

(A) siRNA specific against GATA3 (siGATA3, dotted line) knocks down GATA3 expression compared to control siRNA (siCONTROL) induced in the presence of bortezomib. Analysis of GATA3 protein was conducted by intracellular flow. Using the Amaxa system, 107 fresh CD4+ T cells were electroporated with 20 pmol control or GATA3-targeted SMARTpool siRNA (Dharmacon) as described in Materials and Methods. Cells were rested for 18 h followed by stimulation for 9 h with and without 10 μM bortezomib. Transcript levels of (B) GATA3 and (C) CTLA-4 under the conditions established in (A) were measured by qPCR for samples treated with siCONTROL (black bars) or siGATA3 (white bars) as previously described. Results are presented as averages of three independent experiments ± SEM (*p<0.05). (D) CTLA-4 expressing SS cells show reduction of CTLA-4 when GATA3 is targeted by GATA-specific siRNA as described in Materials and Methods. (E) CTLA-4 expressing PTCL cells show suppression of CTLA-4 when GATA3 is knockdown with GATA-specific siRNA.

We next determine the role of GATA3 in regulating CTLA-4 expression in fresh malignant T cells. In primary CD4+CD45RO+CTLA4+ PBMCs from a patient with SS and a patient with another type of CTLA-4 overexpressing mature CD4+ T cell leukemia, nucleofection of siRNA against GATA3 suppressed CTLA-4 expression (Figure 6d,e). Nucleofection of scrambled siRNA did not suppress CTLA-4 expression. These studies support a role of GATA3 in CTLA-4 regulation in T-cell malignancies.

DISCUSSION

SS is characterized by a defect of cellular immunity, low production of IFN-γ, IL-12 and other Th1 cytokines (Chong et al., 2008). SS is associated with a Th2-skewed cytokine profile with an increased expression of GATA3 and CTLA-4 (Kießling et al., 2011; Nebozhyn et al., 2006; Wong et al., 2006). However, the mechanism leading to GATA3 and CTLA-4 overexpression in SS has not been well characterized. In this study, we show that excessive polyubiquitination of proteins can be detected in T-cells from patients with SS, and establish a mechanistic link between proteasome dysfunction and overexpression of GATA3 and CTLA-4 in fresh malignant T-cells.

To better understand the interplay between the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway and GATA3 and CTLA-4, we inhibited proteasome function in normal T-cells using bortezomib. Cell lines such as Jurkat, Hut78, Hut 102 did not express CTLA-4, thus primary cells were chosen (Data not shown). In CD4+ T cells, we showed that surface-bound CTLA-4 expression increased in the presence of bortezomib and that GATA3 regulates CTLA-4 transcription. The increase was not due to bortezomib-induced apoptosis in the time period necessary for CTLA-4 induction (Supplementary Figure 4). Additionally, we showed that an increase in phosphorylation of GATA3 at S308, the transcriptionally active form, accompanied this response in the presence of bortezomib. We demonstrated via luciferase assays, ChIP analysis, and siRNA knockdown experiments that GATA3 transactivated and interacted with the CTLA-4 promoter. Moreover, in primary malignant T-cells that overexpressed CTLA-4, knockdown of GATA3 could suppress CTLA-4 expression. Taken together, these data delineate a novel regulatory mechanism by which proteasome inhibition increased CTLA-4 expression through the stabilization and activation of GATA3. As CTLA-4 inhibits T cell proliferation, we then addressed whether the increased surface-bound CTLA-4 in bortezomib-treated cells affected T cell proliferation. Bortezomib-treated cells showed sustained surface expression of functionally active CTLA-4 over long intervals and MLR assays showed increased suppression by bortezomib-treated cells, thus supporting the immunsuppression seen in T cell malignancies that overexpress CTLA-4.

We also identified a novel mechanism for CTLA-4 transcriptional regulation: the interaction between GATA3 and the proximal promoter of the CTLA-4 gene. This mechanism is supported indirectly by van Hamburg et al. with studies of a GATA3 overexpressing mouse model in which CTLA-4 expression was increased (van Hamburg et al., 2009). However we showed directly in human T cells in transient promoter reporter assays that transfection of GATA3 augmented luciferase activity with 380 bp of the CTLA-4 promoter, suggesting that GATA3 acted at the proximal CTLA-4 promoter. ChIP assay results further supported this mechanism. Sequence alignment identified three potential GATA3 binding sites within the CTLA-4 proximal promoter. However, DNA-binding assays did not show GATA3 interacting with these sequences (data not shown). Alternatively, GATA3 may not be in direct contact with DNA. Previous studies have shown that GATA3 can act cooperatively with NFAT1 to activate Th2 cytokines at NFAT sites (Avni et al., 2002). There is evidence for direct interaction between NFAT1 and GATA3 as demonstrated by immunocoprecipitation studies (Klein-Hessling et al., 2008). These findings are consistent with the detection of GATA3 by ChIP in a region where we have previously shown that NFAT1 plays a role (Gibson et al., 2007).

Targeted inhibition of GATA3 by siRNA led to a reduction in GATA3 mRNA and protein and reduced expression of CTLA-4. This was a functionally significant reduction, as confirmed by the measured effect on the GATA3-dependent Th2 cytokine IL-4 in T cells. The statistically significant reduction in CTLA-4 after GATA3 knockdown validates the importance of the role of GATA3 in CTLA-4 activation in cells treated with bortezomib. Furthermore, inactivating GATA3 in primary neoplastic T cells can reduce CTLA-4 expression and support the role of dysregulated GATA3 in the increased CTLA-4 in T-cell malignancies. An additional level of proteasome inhibition affecting expression of GATA3 may be via the modulation of protein kinases responsible for GATA3 activation, as phospho-GATA3 increases in a dose-dependent manner with bortezomib. These data show that both stabilization of GATA3 protein and increased phosphorylation contribute to increased CTLA-4 transcription.

In summary, we demonstrate that proteasome inhibition in T-cells leads to increased GATA3 expression, transcriptional upregulation and stabilization of surface-bound CTLA-4, and suppression of normal T-cell growth in a MLR. This regulatory pathway has significant relevance for T-cell malignancies that overexpress CTLA-4, such as SS, which may be characterized by accumulation of polyubiquitinated proteins, by increased GATA3 and CTLA-4 expression and by defective T-cell responses. Thus, the GATA3-CTLA-4 regulatory pathway described in this report may serve as a therapeutic target for SS and other lymphoid malignancies characterized by CTLA-4 mediated immune dysregulation.

Material and Methods

Isolation of primary CD4+ T cells and PBMCs

All patients provided informed consented under an approved research protocol in accordance of the Declaration of Helsinki Protocols and an approved institutional review board where specimen were collected: the Henry Ford Hospital and the Ohio State University. All patient samples were obtained from patients with established diagnosis of Sezary Syndrome defined as erythroderma, lymphadenopathy and circulating Sezary cells. The T cell populations from SS patients were analysed previously by flow cytometry and showed near homogeneity (93% to 99% CD4+CD45RO+). In the samples analyzed, we observed the loss of CD7 and CD26 levels by flow cytometry or by qRT-PCR. Normal CD4+ T cells were purified from leukopacks purchased from the Red Cross using CD4+ T-cell Rosette Sep (#15062, Stem Cell Technologies) as described per the manufacturer’s protocol. PBMCs from normal donors and Sezary patients were isolated using Ficoll as previously described (Wong et al., 2006).

Cell culture

Cells were maintained in RPMI-1640 with 10% fetal FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. All T cell stimulations were performed with 50 ng/mL PMA and 1 μg/mL A23187. Bortezomib (Millennium Pharmaceuticals) was prepared at a stock concentration of 2.5 mM.

RNA isolation, cDNA preparation, and quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was isolated from PBMCs and used to generate cDNA and perform qRT-PCR as previously described (Wong et al., 2006). Expression levels were normalized relative to B2-microglobulin (B2M) for mRNA samples using the 2-ddCt method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001). Primers are shown in Supplementary Table I.

Protein lysates preparation and immunoblot analysis

Protein lysates were prepared, electrophoresed, probed, and visualized as previously described (Wong et al., 2006). The following primary antibodies were utilized for the immunoblots: GATA3 (Abcam ab32858), phospho-GATA3 (Abcam ab61052), Actin (Santa Cruz sc-1616, clone I-19), NFAT1 (Santa Cruz sc-7296, clone 4G6-G5), FoxP3 (Abcam ab20034, clone 236A/E7), polyubiquitin (Cell Signaling 3936, clone P4D1), phospho-I B-α (S32) (Cell Signaling 2859, clone 14D4), CTLA-4 (Beckman Coulter IM2070, clone BNI3), or histone 3 (Cell Signaling 9717S, clone 3H1). Specific proteins were detected with an appropriate secondary Ab (Santa Cruz sc-2354 and Pierce 32460 and 32430) at 1:2000 dilution in I-Block for 1.5 h.

Flow cytometric analysis

Cells were stained for CD4+ (clone 13B8.2) and CTLA-4 (clone BNI3) from (Beckman Coulter IM2636U and BD 555853, respectively) for 20 min followed by washing with PBS and analysis on a FACS Calibur. Intracellular expression was performed according to the manufactuer’s instructions (eBioscience) to detect FoxP3 and GATA3 (eBioscience 12-9966-42, clone TWAJ). Data was analyzed with FlowJo software.

Mixed lymphocyte reaction

Primary CD4+ T cells were PMA/A23187 stimulated with 0, 0.1 and 10 μM bortezomib for 9 h and allogeneic PBMCs were treated with 50 μg/mL mitomycin C for 30 min. Washed cells were then plated in a 96-well flat bottom plate at 5x105 PBMCs mixed with 5x105 CD4+ cells per well in RPMI 1640 medium with 10% fetal bovine serum. Samples were treated with 0.5 μg CTLA-4 blocking antibody or mouse IgG2a control (Beckman Coulter IM2070 and A55763, respectively). After 7 days, an MTS assay (Promega G5421) was peformed, and proliferation was measured via the A 570.

Plasmids and reporter transcription analysis

CTLA-4 promoter constructs were cloned into the pGL3 luciferase vector as previously described (Gibson et al., 2007). Promoterless pGL3 Basic and SV40-driven pGL3 Control were used as controls. The GATA3 expression vector was kindly received from Dr. Gerd Blobel. E1A 12S WT and mutant constructs were described previously (Wong and Ziff, 1994). Jurkat cells were seeded in 6 well plates at 1.5x106 cells per sample in serum-free RPMI-1640. 1 μg CTLA-4 380 bp luciferase construct was transfected into each sample with increasing concentrations (0, 0.5, 1, 2 and 3 μg) GATA3 expression vector or vector control plasmid in triplicate using Lipofectin (Invitrogen) per the manufacturer’s protocol. Cells were lysed in luciferase lysis buffer (25 mM glycylglycine, 15 mM MgSO4, 4 mM EGTA, 1% Triton X-100) with DTT added to 1 mM immediately prior to use, and equal protein concentrations were subjected to luciferase analysis. The luciferase level was determined using a Lumat LB 9501 luminometer as described previously (Ausubel et al., 2003).

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay

Cells treated as indicated and fixed for 10 min in 1% formaldehyde to crosslink protein and DNA complexes. The reaction was quenched with the addition of 1.25 M glycine for 5 min. Cells were pelleted and resuspended in RIPA buffer (50 mM Tris pH 7.4, 150 mM NaCl, 1% NP-40, 1% SDS). Samples were sonicated to shear DNA fragments to within 200–1000 bp, centrifuged to remove cellular debris, and diluted 10-fold with ChIP dilution buffer to reduce SDS concentration. Immunoprecipitations were performed using the ChIP Assay Kit (Millipore), antibodies to GATA3 (Santa Cruz), and isotype control antibodies (Millipore), as necessary. Immunoprecipitated DNA fragments were purified with QiaQuick gDNA columns (Qiagen) and evaluated by PCR or qRT-PCR with primers specific to the CTLA-4 promoter as indicated in Supplementary Table I.

Nucleic acid electroporation

Primary CD4+ T cells were electroporated with 107 cells using the Amaxa system at a setting of U014 and the Amaxa Human T Cell Kit for each sample. Expression plasmids for GATA3 or control vector were electroporated at 2 μg/sample. siRNA was electroporated at 20 pmol/sample SmartPool siRNA directed at GATA3 or off-target control (Dharmacon). After electroporation, cells were transferred to RPMI 1640 culture media with 10% fetal bovine serum and allowed to rest for 18 h.

Statistical analysis

A Student’s t-test (2-tailed, unequal variance) was used to analyze the significance of differences between two experimental groups. Data with a p value of 0.05 or less were considered to be significant.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The work was supported by funds from the National Cancer Institute P30 supplement to the OSU Comprehesive Cancer Center, funds from the James Cancer Hospital and OSU Dermatology Research funds.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: None

References

- Adams J, Kauffman M. Development of the proteasome inhibitor Velcade (Bortezomib) Cancer Invest. 2004;22:304–311. doi: 10.1081/cnv-120030218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ausubel FM, Brent R, Kingston E, Moore DD, Seidman JG, Smith JA, et al. Current Protocols in Molecular Biology. Wiley; New York: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Avni O, Lee D, Macian F, Szabo SJ, Glimcher LH, Rao A. T(H) cell differentiation is accompanied by dynamic changes in histone acetylation of cytokine genes. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:643–651. doi: 10.1038/ni808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balic I, Angel B, Codner E, Carrasco E, Perez-Bravo F. Association of CTLA-4 polymorphisms and clinical-immunologic characteristics at onset of type 1 diabetes mellitus in children. Hum Immunol. 2009;70:116–120. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2008.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boulougouris G, McLeod JD, Patel YI, Ellwood CN, Walker LS, Sansom DM. Positive and negative regulation of human T cell activation mediated by the CTLA-4/CD28 ligand CD80. J Immunol. 1998;161:3919–3924. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunet JF, Denizot F, Luciani MF, Roux-Dosseto M, Suzan M, Mattei MG, et al. A new member of the immunoglobulin superfamily--CTLA-4. Nature. 1987;328:267–270. doi: 10.1038/328267a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carreno BM, Bennett F, Chau TA, Ling V, Luxenberg D, Jussif J, et al. CTLA-4 (CD152) can inhibit T cell activation by two different mechanisms depending on its level of cell surface expression. J Immunol. 2000;165:1352–1356. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.3.1352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chong BF, Wilson AJ, Gibson HM, Hafner MS, Luo Y, Hedgcock CJ, et al. Immune function abnormalities in peripheral blood mononuclear cell cytokine expression differentiates stages of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma/mycosis fungoides. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:646–653. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-0610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook KD, Miller J. TCR-dependent translational control of GATA-3 enhances Th2 differentiation. J Immunol. 2010;185:3209–3216. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0902544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson HM, Hedgcock CJ, Aufiero BM, Wilson AJ, Hafner MS, Tsokos GC, et al. Induction of the CTLA-4 gene in human lymphocytes is dependent on NFAT binding the proximal promoter. J Immunol. 2007;179:3831–3840. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.6.3831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahtola S, Tuomela S, Elo L, Hakkinen T, Karenko L, Nedoszytko B, et al. Th1 response and cytotoxicity genes are down-regulated in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:4812–4821. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-0532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hori S, Nomura T, Sakaguchi S. Control of regulatory T cell development by the transcription factor Foxp3. Science. 2003;299:1057–1061. doi: 10.1126/science.1079490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang SS, Lee S, Lee W, Lee GR. GATA-binding protein-3 regulates T helper type 2 cytokine and ifng loci through interaction with metastasis-associated protein 2. Immunology. 2010;131:50–58. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2010.03271.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonuleit H, Schmitt E, Stassen M, Tuettenberg A, Knop J, Enk AH. Identification and functional characterization of human CD4(+)CD25(+) T cells with regulatory properties isolated from peripheral blood. J Exp Med. 2001;193:1285–1294. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.11.1285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kavvoura FK, Akamizu T, Awata T, Ban Y, Chistiakov DA, Frydecka I, et al. Cytotoxic T-lymphocyte associated antigen 4 gene polymorphisms and autoimmune thyroid disease: a meta-analysis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:3162–3170. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-0147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keilholz U. CTLA-4: negative regulator of the immune response and a target for cancer therapy. J Immunother. 2008;31:431–439. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e318174a4fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kießling MK, Oberholzer PA, Mondal C, Karpova MB, Zipser MC, Lin WM, et al. High-throughput mutation profiling of CTCL samples reveals KRAS and NRAS mutations sensitizing tumors toward inhibition of the RAS/RAF/MEK signaling cascade. Blood. 2011;117:2433–2440. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-09-305128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein-Hessling S, Bopp T, Jha MK, Schmidt A, Miyatake S, Schmitt E, et al. Cyclic AMP-induced chromatin changes support the NFATc-mediated recruitment of GATA-3 to the interleukin 5 promoter. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:31030–31037. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805929200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee YH, Harley JB, Nath SK. CTLA-4 polymorphisms and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE): a meta-analysis. Hum Genet. 2005;116:361–367. doi: 10.1007/s00439-004-1244-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linsley PS, Brady W, Urnes M, Grosmaire LS, Damle NK, Ledbetter JA. CTLA-4 is a second receptor for the B cell activation antigen B7. J Exp Med. 1991;174:561–569. doi: 10.1084/jem.174.3.561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linsley PS, Greene JL, Tan P, Bradshaw J, Ledbetter JA, Anasetti C, et al. Coexpression and functional cooperation of CTLA-4 and CD28 on activated T lymphocytes. J Exp Med. 1992a;176:1595–1604. doi: 10.1084/jem.176.6.1595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linsley PS, Wallace PM, Johnson J, Gibson MG, Greene JL, Ledbetter JA, et al. Immunosuppression in vivo by a soluble form of the CTLA-4 T cell activation molecule. Science. 1992b;257:792–795. doi: 10.1126/science.1496399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(−Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maneechotesuwan K, Xin Y, Ito K, Jazrawi E, Lee KY, Usmani OS, et al. Regulation of Th2 cytokine genes by p38 MAPK-mediated phosphorylation of GATA-3. J Immunol. 2007;178:2491–2498. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.4.2491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakata Y, Brignier AC, Jin S, Shen Y, Rudnick SI, Sugita M, et al. c-Myb, Menin, GATA-3, and MLL form a dynamic transcription complex that plays a pivotal role in human T helper type 2 cell development. Blood. 2010;116:1280–1290. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-05-223255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nebozhyn M, Loboda A, Kari L, Rook AH, Vonderheid EC, Lessin S, et al. Quantitative PCR on 5 genes reliably identifies CTCL patients with 5% to 99% circulating tumor cells with 90% accuracy. Blood. 2006;107:3189–3196. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-07-2813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oosterwegel MA, Greenwald RJ, Mandelbrot DA, Lorsbach RB, Sharpe AH. CTLA-4 and T cell activation. Curr Opin Immunol. 1999;11:294–300. doi: 10.1016/s0952-7915(99)80047-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi T, Tagami T, Yamazaki S, Uede T, Shimizu J, Sakaguchi N, et al. Immunologic self-tolerance maintained by CD25(+)CD4(+) regulatory T cells constitutively expressing cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4. J Exp Med. 2000;192:303–310. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.2.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teft WA, Kirchhof MG, Madrenas J. A molecular perspective of CTLA-4 function. Annu Rev Immunol. 2006;24:65–97. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.24.021605.090535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tivol EA, Borriello F, Schweitzer AN, Lynch WP, Bluestone JA, Sharpe AH. Loss of CTLA-4 leads to massive lymphoproliferation and fatal multiorgan tissue destruction, revealing a critical negative regulatory role of CTLA-4. Immunity. 1995;3:541–547. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90125-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Hamburg JP, de Bruijn MJ, Ribeiro de Almeida C, Dingjan GM, Hendriks RW. Gene expression profiling in mice with enforced Gata3 expression reveals putative targets of Gata3 in double positive thymocytes. Mol Immunol. 2009;46:3251–3260. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2009.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waterhouse P, Marengere LE, Mittrucker HW, Mak TW. CTLA-4, a negative regulator of T-lymphocyte activation. Immunol Rev. 1996;153:183–207. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1996.tb00925.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waterhouse P, Penninger JM, Timms E, Wakeham A, Shahinian A, Lee KP, et al. Lymphoproliferative disorders with early lethality in mice deficient in Ctla-4. Science. 1995;270:985–988. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5238.985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong HK, Wilson AJ, Gibson HM, Hafner MS, Hedgcock CJ, Berger CL, et al. Increased expression of CTLA-4 in malignant T-cells from patients with mycosis fungoides -- cutaneous T cell lymphoma. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:212–219. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong HK, Ziff EB. Complementary functions of E1a conserved region 1 cooperate with conserved region 3 to activate adenovirus serotype 5 early promoters. J Virol. 1994;68:4910–4920. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.8.4910-4920.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y, Borde M, Heissmeyer V, Feuerer M, Lapan AD, Stroud JC, et al. FOXP3 controls regulatory T cell function through cooperation with NFAT. Cell. 2006;126:375–387. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yagi R, Zhu J, Paul WE. An updated view on transcription factor GATA3-mediated regulation of Th1 and Th2 cell differentiation. Int Immunol. 2011;23:415–420. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxr029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita M, Shinnakasu R, Asou H, Kimura M, Hasegawa A, Hashimoto K, et al. Ras-ERK MAPK cascade regulates GATA3 stability and Th2 differentiation through ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:29409–29419. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502333200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J. Transcriptional regulation of Th2 cell differentiation. Immunol Cell Biol. 2010;88:244–249. doi: 10.1038/icb.2009.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.