Abstract

Background and Aims Globally, zinc deficiency is one of the most important nutritional factors limiting crop yield and quality. Despite widespread use of foliar-applied zinc fertilizers, much remains unknown regarding the movement of zinc from the foliar surface into the vascular structure for translocation into other tissues and the key factors affecting this diffusion.

Methods Using synchrotron-based X-ray fluorescence microscopy (µ-XRF), absorption of foliar-applied zinc nitrate or zinc hydroxide nitrate was examined in fresh leaves of tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) and citrus (Citrus reticulatus).

Key Results The foliar absorption of zinc increased concentrations in the underlying tissues by up to 600-fold in tomato but only up to 5-fold in citrus. The magnitude of this absorption was influenced by the form of zinc applied, the zinc status of the treated leaf and the leaf surface to which it was applied (abaxial or adaxial). Once the zinc had moved through the leaf surface it appeared to bind strongly, with limited further redistribution. Regardless of this, in these underlying tissues zinc moved into the lower-order veins, with concentrations 2- to 10-fold higher than in the adjacent tissues. However, even once in higher-order veins, the movement of zinc was still comparatively limited, with concentrations decreasing to levels similar to the background within 1–10 mm.

Conclusions The results advance our understanding of the factors that influence the efficacy of foliar zinc fertilizers and demonstrate the merits of an innovative methodology for studying foliar zinc translocation mechanisms.

Keywords: Nutrient absorption, foliar zinc application, short-distance nutrient transport, veins, X-ray fluorescence microscopy, XRF, Zn movement, crop nutrition, tomato, Solanum lycopersicum, Citrus reticulatus

INTRODUCTION

Zinc (Zn) deficiency is one of the five most important micronutrient deficiencies in humans, affecting approximately one-third of the global population (IZINCG, 2004). The foliar application of Zn fertilizer is one of the important treatments to safeguard crop yield and fortify Zn intake for human nutrition (Cakmak, 2008). However, the mechanisms of foliar uptake are comparatively poorly understood and current understanding of the factors that influence the ultimate efficacy of foliar applications remains incomplete (Fernández et al., 2013). Investigation of the foliar uptake of Zn is needed for the development of foliar Zn fertilizers that have improved penetration/movement, are long-lasting and have low phytotoxicity.

The foliar uptake of Zn first requires the movement/absorption of the Zn across the cuticle and/or through the stomatal cavity (Fernández and Brown, 2013). Both the cuticle and the stomata appear to be of importance for the uptake of inorganic nutrients (Eichert et al., 2008), although many uncertainties remain. For the cuticle, the penetration of apolar liphophilic compounds can be described using the dissolution–diffusion model, but the mechanisms of the penetration of hydrophilic polar solutes are not fully understood (for a review see Fernández and Brown, 2013). Given that the uptake of nutrients first requires movement across the cuticle and/or through the stomatal cavity, it is not surprising that this uptake is influenced by the characteristics of the leaf surface, including the thickness of the wax layer and the distribution of stomata and trichomes (Schreiber and Schönherr, 1993; Schönherr, 2006; Eichert and Goldbach, 2008). Interestingly, the densities of trichomes and stomata are typically differentially distributed in the adaxial and abaxial surfaces and can vary substantially among species (Schilmiller et al., 2008). It is also known that leaf age and nutrient deficiency can substantially influence the surface structure of leaves (Hauke and Schreiber, 1998; Fernández et al., 2008; Shi and Cai, 2009). However, comparatively little is known regarding the relationships among leaf surface structural characteristics (including those induced by leaf age or by Zn deficiency) and Zn penetration and diffusion into the leaf (Loneragan et al., 1976; Zhang and Brown, 1999a; Fernández and Brown, 2013).

After the movement (absorption) of foliar-applied Zn through the leaf surface, the overall efficacy of this Zn depends upon the subsequent loading of the Zn into the foliar vascular systems (consisting of interconnected veins of minor to primary classes) and its subsequent translocation via the phloem of primary veins into the other growing tissues of the plant (Loneragan et al., 1976; Marschner, 1995; Zhang and Brown, 1999b; Fernández and Brown, 2013). However, there remains much that is unknown regarding the initial movement of newly absorbed Zn into the vascular vein system and its subsequent retranslocation out of sprayed leaves into other plant parts (for recent reviews see Fernández and Brown, 2013; Fernández et al., 2013).

Recent advances in synchrotron-based techniques now allow in situ analysis of the distribution (and speciation) of metals and metalloids in hydrated and fresh plant tissues with no observable damage (Lombi et al., 2011). The Maia detector system represents a new generation of X-ray fluorescence (XRF) detector that provides unprecedented capability to investigate low concentrations of trace elements in hydrated plant samples (Kirkham et al., 2010). Given that it is approximately 10- to 100-fold faster than traditional XRF detectors, it can be used to study trace metal uptake and distribution in highly hydrated tissues such as fresh roots (Kopittke et al., 2011, 2012, 2014). For the examination of foliar-applied Zn, some previous studies have used autoradiography to provide data on the spatial distribution of Zn following foliar application (Wallihan and Heymann-Herschberg, 1956; Marešová et al., 2012). Synchrotron-based µ-XRF offers several advantages, including improved spatial resolution and greater flexibility in regard to the analysis of the data.

Therefore, the aim of the present study was to use µ-XRF to provide in situ quantitative data on the absorption and short-distance movement of foliar-applied Zn using hydrated and fresh leaves. Using both tomato and citrus, Zn diffusion characteristics were compared between (1) plant species, (2) abaxial and adaxial leaf surfaces, (3) leaves of differing age, (4) leaves of differing Zn status and (5) leaves of differing Zn forms. The aim was to gather information on the factors that influence the efficacy of foliar Zn fertilizers, to assist in improving plant growth in Zn-deficient conditions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plant growth

Plants were grown in a glasshouse at The University of Queensland (St Lucia, Australia) during autumn with a diurnal temperature range of 25–30 °C. Seeds of Roma tomato (Solanum lycopersicum ‘Roma’) were rinsed with deionized water and then germinated on moistened towel paper which was soaked with 0·5 mm CaSO4.2H2O at 25 °C in the dark. After germination, the tomato seedlings were cultured in one-third strength nutrient solution in the glasshouse. When the second true leaf was nearly fully expanded, seedlings of uniform appearance and size were transplanted into continuously aerated full strength nutrient solution in 5-L pots lined with plain polythene bags for 2 weeks. The full-strength basal nutrient solution used in the experiments contained (µm): NH4NO3, 2000; KNO3, 2800; Ca(NO3)2, 1600; MgSO4, 1000; KH2PO4, 100; K2HPO4, 100; Fe-EDTA, 40; NaCl, 8; MnSO4, 2; CuSO4, 0·5; Na2MoO4, 0·08; ZnSO4, 1; H3BO3, 10 (Huang et al., 2008). For tomato, some plants were grown with Zn included in the basal solution (‘Zn-sufficient’) whilst other plants were grown without Zn in the basal solution (‘Zn-deficient’). Macronutrient stocks were purified to remove residual Zn by complexation with 8-hydroxyquinoline (Oxine) in chloroform at pH 5·5 (Hewitt, 1966). Deionized water used in the glasshouse was further purified by consecutively passing it through a column packed with resin (Cartridge type C114, ELGA LabWater) to prepare all chemical and nutrient solutions used in the glasshouse experiments. Solution pH in all pots was maintained between 5·5 and 6·5 using 1 mm HCl.

Citrus (Citrus reticulatus ‘Imperial’) plants were purchased from a commercial nursery and transferred into 20-L pots filled with potting mix and basal nutrients for at least 1 month of acclimation in the glasshouse. All citrus plants were grown with Zn included in the basal nutrients of the soil culture (i.e. Zn-sufficient).

Leaf incubation and Zn treatment

Four types leaves were selected as follows: (1) the youngest fully expanded leaf (YFEL) from Zn-deficient tomato; (2) the YFEL from Zn-sufficient tomato; (3) the YFEL from Zn-sufficient citrus; and (4) the oldest leaf (i.e. above the cotyledon) from Zn-sufficient tomato. One day prior to sampling, the leaves were surface-rinsed with deionized water and blotted dry in order to remove dust from the leaf surface. The following day, the leaves were cut at the base of the petiole. The petioles of the leaves were immediately immersed in a Zn-free nutrient solution in a plastic centrifuge vial (1·5 mL) that was fixed inside an incubation chamber (Vu et al., 2013). At the same time, another set of four leaves from the same positions was collected for digestion and tissue analysis.

The leaves were treated and incubated in the same manner as described in Vu et al. (2013). After ∼1 h of acclimation in the laboratory, the leaves were either (1) treated with 12–16 droplets (5 µL each) of 400 mgZn L−1 as Zn(NO3)2 or Zn hydroxide nitrate (ZnHN) suspensions (∼30–50 mgL−1) in two rows on the central region of each leaf surface (rows were at right angles to the midrib vein), or (2) sprayed with Zn(NO3)2 or ZnHN (the latter only for the YFEL of Zn-sufficient citrus and tomato). These treatments were applied to either the adaxial or the abaxial leaf surface. Thus, the experiment consisted of combinations of the following treatment factors: four types of leaves (YFEL from Zn-deficient tomato, YFEL from Zn-sufficient citrus, YFEL from Zn-sufficient tomato, and oldest leaf from Zn-sufficient tomato); two forms of Zn [Zn(NO3)2 or ZnHN]; leaf surface side (adaxial or abaxial); and two methods of Zn application (droplets or spray; Supplementary Data Table S1), with a total of 22 treatment units (including controls). In relevant controls, no Zn was applied directly to the foliage. After loading, the droplets on leaf surfaces were allowed to evaporate (while their petioles remained in the bathing solution) before being placed inside incubation chambers. In all tests, the droplets applied to leaf surfaces remained in position without movement because of the small droplet size and surface tension. The ZnHN suspension droplets adhered well to the surfaces (Vu et al., 2013). No free droplets of water/solution were visible on leaf surfaces during incubation.

The ZnHN suspension was prepared as described by Li et al. (2012). Leaves were then cultured in an incubator (TRISL-490-1VW, Thermoline Scientific, Australia) with controlled temperature and light conditions (12 h at 22 °C light/12 h dark at 18 °C) for 24 h. The leaves were then transported in Petri dishes in a cooled (10 °C) container to the Australian Synchrotron, Melbourne. The petioles of the leaves remained in contact with the Zn-free nutrient solution during transport to maintain turgor.

Synchrotron-based X-ray fluorescence microscopy

The leaf surface was thoroughly washed with a running jet-stream consisting of a mixture of 2 % HNO3 and 3 % ethanol and rinsed with deionized water to remove the Zn residues from the leaf surface (Vu et al., 2013). Leaves were analysed at the X-ray fluorescence microscopy (XFM) beamline using an in-vacuum undulator to produce a brilliant X-ray beam. A silicon-111 monochromator and Kirkpatrick–Baez mirrors were used to deliver a monochromatic focused beam of around 2 × 2 µm2 onto the specimen (Paterson et al., 2011). The XRF emitted by the specimen was collected using the 384-element Maia detector placed in backscatter geometry (Kirkham et al., 2010). For all scans, samples were analysed continuously in the horizontal direction (on the fly).

The washed leaves were blotted dry using paper tissue before being cut in half. One half of a leaf (without the midrib) was placed between two pieces of 4-µm thick Ultralene film, forming a tight seal around the leaf to limit dehydration. For each sample, two scans were performed. The first scan (‘survey scan’) was comparatively rapid and aimed to (1) examine the entire sample and (2) identify the portion of the leaf surface to which the Zn had been applied (to allow a more detailed scan). The second scan (‘detailed scan’) was performed on a smaller area of the tissues surrounding the portion of the leaf to which the Zn had been applied. This detailed scan was conducted with a smaller pixel size and a lower dwell (to increase both spatial resolution and sensitivity). For the survey scan, the transit time per 100-µm pixel was 12 ms (scanning velocity 8·2 mms−1), and hence maps of 20 × 70 mm could generally be collected within ∼30 min. For the detailed scan, the transit time per 15-µm pixel was 7·3 ms (scanning velocity 2·0 mms−1), and hence maps of 5 × 10 mm could generally be collected within ∼90 min. Following the survey scan and the detailed scan, the leaves were checked for damage using light microscopy. As found for highly hydrated roots analysed using this technique (Kopittke et al., 2011), there was no visible evidence of damage following examination using µ-XRF.

The XRF event stream was analysed using GeoPIXE (Ryan and Jamieson, 1993; Ryan, 2000). Projected Zn concentrations were obtained by correcting the areal concentration using sample thickness. Given that the thickness of the veins varied substantially, the thickness at a given point was first measured under a light microscope (×400), and then the thickness was calculated for other points along the vein using the Compton scatter.

Leaf vein order definition

The vein orders of a leaf in this study was defined as follows: the midrib is the first vein order, hereafter termed ‘1° vein’, with smaller veins successively branching from the midrib termed 2° (major vein), 3°, 4°, 5°, 6°, 7° and so forth (or minor veins, which are not associated with midribs) (Sack et al., 2012). Changes in projected Zn concentrations along the selected veins obtained by XRF were fitted using an exponential regression with Origin (OriginPro 8). When examining changes in the concentration of Zn within leaf tissues, an equation was fitted of the general form:

| (1) |

where Zn is the tissue Zn concentration, b is the maximum tissue concentration of Zn, c is a strength coefficient, D is distance and h is a shape coefficient (Kinraide, 1999).

Zn analysis

Leaf samples collected for background Zn analysis were dried at 68 °C for 72 h and digested in concentrated nitric acid and H2O2 mixture at 125 °C with a microwave oven (START-D Microwave Digestion System, Milestone, Italy) (Huang et al., 2004). Zinc concentrations in the digested solution were quantified by inductively coupled optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES, Vista Liberty Varian). Standard reference material (NIST1515 apple leaves) samples were included in acid digestion and Zn analysis together with all the experimental samples for accuracy assurance.

RESULTS

Leaf characterization

The Zn concentration in the YFELs of Zn-sufficient tomato (2·57 µg g−1, fresh mass basis) was similar to that in the mature (older) leaves of Zn-sufficient tomato plants (2·45 µg g−1) but higher than that in the YFELs of Zn-deficient tomato (1·77 µg g−1; Supplementary Data Table S2). Indeed, this Zn concentration in the YFELs of Zn-deficient tomato (equivalent to 10 µg g−1 on a dry mass basis) is lower than those reported to be adequate for unlimited growth (Huett et al., 1997). The concentration of Zn in citrus YFELs (5·65 µg g−1) was higher than in tomato (2·57 µg g−1), although values were similar when expressed on a dry mass basis (Supplementary Data Table S2).

The density of stomata on the abaxial (18 445 cm−2) surface of YFELs from Zn-sufficient tomato plants was ∼12-fold higher than that on the adaxial (1517 cm−2) surface, while mature leaves had much lower stomatal density (44 cm−2) than YFELs (Supplementary Data Table S3). The YFELs from Zn-deficient tomato plants had stomatal density around 117 cm−2 on the adaxial leaf surface. In addition, the abaxial leaf surface of YFELs from Zn-sufficient tomato leaves had more than twice as many trichomes as the adaxial surface. Zinc deficiency and leaf ageing significantly decreased the density of trichomes (Supplementary Data Table S3). The citrus leaves did not have stomata on the adaxial leaf surface but had stomata (493 cm−2) on the abaxial leaf surface.

Absorption of Zn through the leaf surface

As demonstrated by the highly elevated Zn concentrations compared with the baseline, the foliar application of Zn-containing solution resulted in penetration and retention (absorption) of the applied Zn through the leaf surface (e.g. Fig. 1, Supplementary Data Fig. S1, Table 1). Indeed, analyses using µ-XRF revealed that the average projected volumetric concentration of Zn in the tissues immediately below where the droplets had been applied increased from ∼0·5–1 to ≤560 µg cm−3 (Table 1). However, substantial differences were observed between treatments.

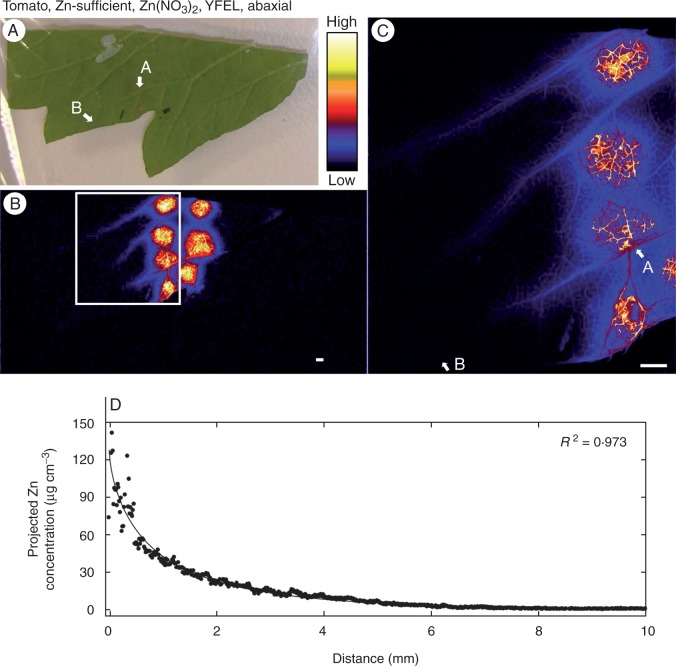

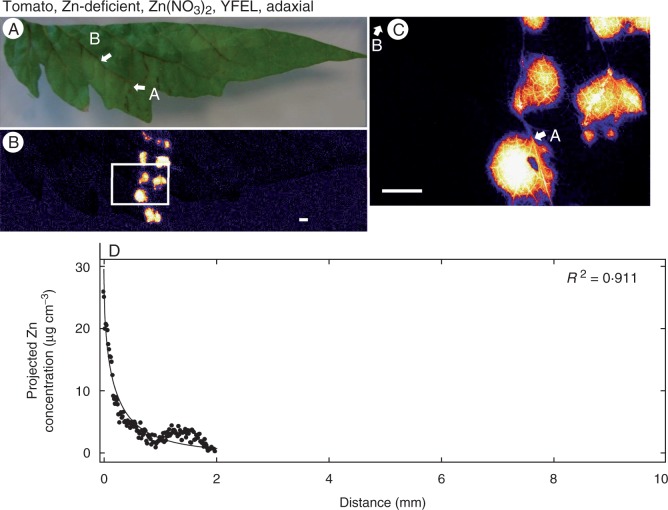

Fig. 1.

Zinc concentration of the youngest fully expanded leaf (YFEL) of tomato (abaxial surface from the Zn-sufficient treatment) to which droplets of Zn(NO3)2 had been applied. (A) Image of half of a tomato leaf captured using a digital camera. (B) Survey (overview) scan of leaf in (A) using µ-XRF. (C) Detailed scan of the area indicated by the white rectangle in (B). (D) Projected Zn concentration along the vein from point A to point B as shown in (C). Brighter colours correspond to higher Zn concentrations. Scale bars = 1 mm.

Table 1.

Changes in projected concentrations of Zn in leaf tissues of tomato and citrus to which droplets of either Zn(NO3)2 or ZnHN were applied to the abaxial or adaxial surface (for the control there was no foliar-applied Zn). Plants were grown in the presence (Zn-sufficient) or absence (Zn-deficient) of Zn in the rooting medium, and the leaves examined were either the youngest fully expanded leaf (YFEL) or a mature leaf. Using µ-XRF analysis, average concentrations of Zn were determined either in the tissues underneath where the droplet was applied or in tissues at least 5 mm from where the droplet was applied. For the strength coefficient (c), eqn 1 was fitted for projected concentrations along the length of a vein. Concentrations are reported on a fresh mass basis

| Zn(NO3)2 |

ZnHN |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concentration under droplet (µg cm−3), mean ± s.d. | Baseline leaf concentration (µg cm−3), mean ± s.d. | c (95 % confidence interval) | Concentration under droplet (µg cm−3), mean ± s.d. | Baseline leaf concentration (µg cm−3), mean ± s.d. | c (95 % confidence interval) | ||||

| Tomato | Zn-sufficient | YFEL | Abaxial | 560 ± 150 | 0·88 ± 0·22 | 0·81 (0·71, 0·91) | 220 ± 17 | 0·81 ± 0·22 | 0·67 (0·62, 0·71) |

| Zn-sufficient | YFEL | Adaxial | 230 ± 200 | 0·88 ± 0·18 | 0·49 (0·46, 0·51) | 87 ± 41 | 0·96 ± 0·07 | 0·45 (0·43, 0·46) | |

| Zn-deficient | YFEL | Adaxial | 310 ± 150 | <0·5 | 5·4 (4·3, 6·6) | 180 ± 64 | < 0·5 | 1·6 (1·5, 1·7) | |

| Zn-sufficient | Mature | Adaxial | 320 ± 110 | <0·5 | 3·2 (2·8, 3·6) | 220 ± 24 | < 0·5 | 0·38 (0·32, 0·44) | |

| Citrus | Zn-sufficient | YFEL | Abaxial | 6·0 ± 8·7 | 1·1 ± 0·27 | – | 1·7 ± 0·50 | 1·0 ± 0·29 | – |

| Zn-sufficient | YFEL | Adaxial | 3·7 ± 0·40 | 0·57 ± 0·14 | – | 2·1 ± 0·87 | 0·90 ± 0·39 | – | |

Firstly, as expected, differences were observed between the two plant species. The magnitude of the increase in the concentrations of Zn in the tissues immediately below where the droplets had been applied were substantially greater for tomato than for citrus. Indeed, e.g. projected volumetric concentrations increased 600-fold from 0·88 to 560 µg cm−3 for tomato (Table 1, Fig. 1B, C) but only ∼5-fold for citrus (from 1·1 to 6·0 µg cm−3) (Table 1, Fig. 2A, C) when droplets of Zn(NO3)2 were applied to the abaxial surfaces of the YFELs.

Fig. 2.

Zinc concentration of the youngest fully expanded leaf (YFEL) of citrus to which droplets of Zn(NO3)2 had been applied. (A) Image of half a leaf (top, abaxial; bottom, adaxial) captured using a digital camera. (B) Survey scan of the leaf in (A) using µ-XRF. A detailed scan of either the (C) abaxial surface as indicated by the white rectangle or (D) the adaxial surface as indicated by the red rectangle. The projected Zn concentration along the vein from point A to B as shown in (C) for either (E) the abaxial surface or (F) the adaxial surface. Brighter colours correspond to higher Zn concentrations. Scale bars = 1 mm.

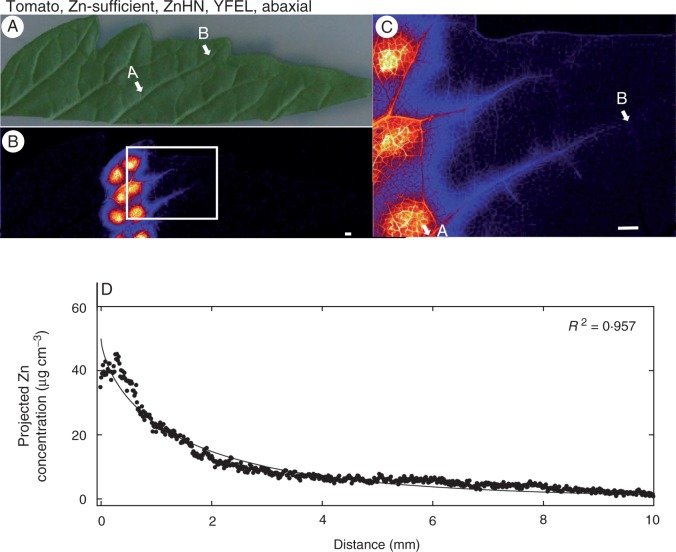

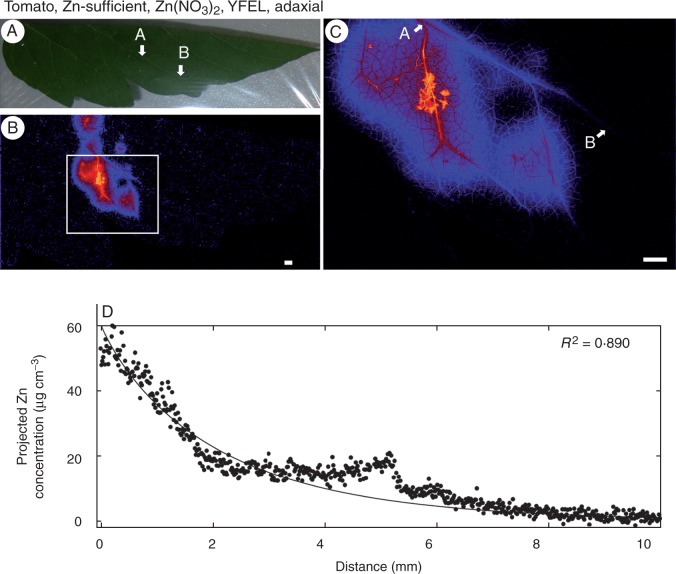

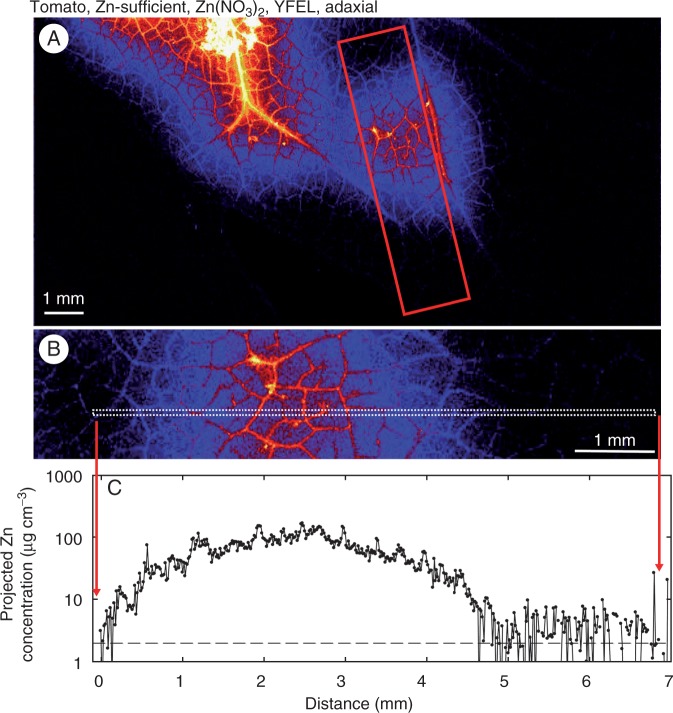

Although both Zn(NO3)2 and ZnHN resulted in substantial increases in Zn concentrations in the tissues underlying the droplets (particularly in tomato), the extent to which this Zn moved through the leaf surface varied. Across all treatments, it was observed that the concentration of Zn in the underlying tissues was approximately 2-fold higher for Zn(NO3)2 than for ZnHN (Table 1). For example, in the YFELs of Zn-sufficient tomato, the application of droplets of Zn(NO3)2 to the abaxial leaf surface resulted in an increase in average projected volumetric concentrations of Zn from 0·88 to 560 µg cm−3 (Table 1, Fig. 1B, C) but ZnHN resulted in an increase from 0·81 to 220 µg cm−3 (Table 1, Fig. 3B, C). Similarly, for the adaxial surface of the YFELs of tomato, the application of Zn(NO3)2 increased projected volumetric concentrations of Zn to 230 µg cm−3 (Table 1, Fig. 4B, C) whilst ZnHN increased tissue concentrations to 87 µg cm−3 (Table 1, Supplementary Data Fig. S2).

Fig. 3.

Zinc concentration of the youngest fully expanded leaf (YFEL) of tomato (abaxial surface from the Zn-sufficient treatment) to which droplets of ZnHN had been applied. (A) Image of half a leaf captured using a digital camera. (B) Survey (overview) scan of the leaf in (A) using µ-XRF. (C) Detailed scan of the area indicated by the white rectangle in (B). (D) Projected Zn concentration along the vein from point A to point B as shown in (C). Brighter colours correspond to higher Zn concentrations. Scale bars = 1 mm.

Fig. 4.

Zinc concentration of the youngest fully expanded leaf (YFEL) of tomato (adaxial surface from the Zn-sufficient treatment) to which droplets of Zn(NO3)2 had been applied. (A) Image of half a leaf captured using a digital camera. (B) Survey (overview) scan of the leaf in (A) using µ-XRF. (C) Detailed scan of the area indicated by the white rectangle in (B). (D) Projected Zn concentration along the vein from A to point B as shown in (C). Brighter colours correspond to higher Zn concentrations. Scale bars = 1 mm.

The surface of the leaf to which the Zn was applied was also important in influencing the extent to which Zn was absorbed (particularly for tomato), with more Zn moving through abaxial surfaces than through adaxial surfaces. For tomato, the concentration of Zn in the underlying tissues was ∼2-fold higher when the Zn was applied to the abaxial surface (560 µg cm−3; Table 1, Fig. 1B, C) than to the adaxial surface (230 µg cm−3; Table 1, Fig. 4B, C). This effect appeared to be independent of whether the Zn was supplied as Zn(NO3)2 or ZnHN, with the tissues containing 220 µg cm−3 when supplied with ZnHN to the abaxial surface (Table 1, Fig. 3B, C) but only 87 µg cm−3 when supplied to the adaxial surface (Table 1; Supplementary Data Figs S2 and S3). The relative importance of abaxial surfaces versus adaxial surfaces in citrus was less clear due to the much lower absorption of Zn in these leaves (Table 1).

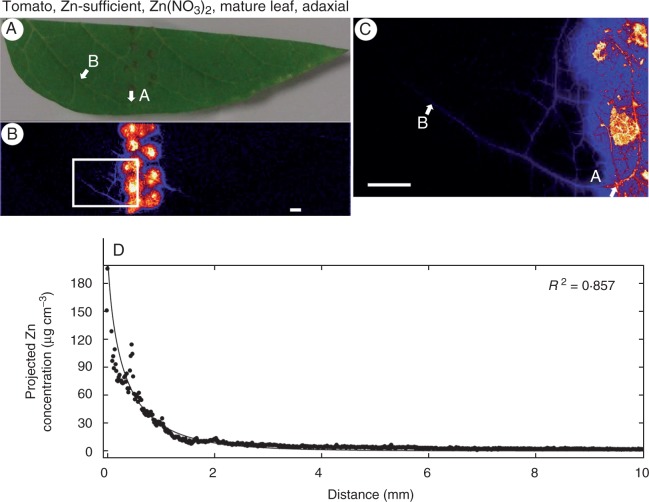

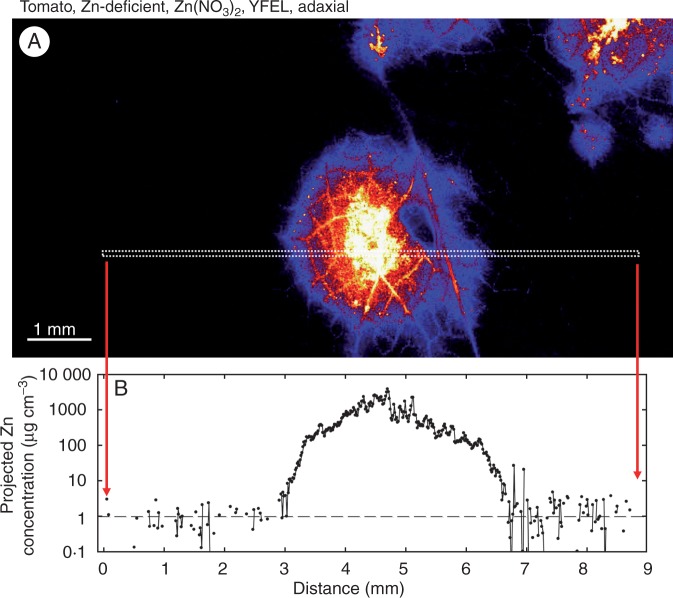

Finally, neither the Zn status of the plant nor the age of the leaf appeared to influence the magnitude of the movement of Zn through the leaf surface. For example, when Zn(NO3)2 was supplied to the adaxial surfaces of tomato leaves, the projected concentration of Zn in the underlying tissues was similar in the Zn-sufficient YFEL (230 µg cm−3; Table 1, Fig. 4B, C) and in the Zn-sufficient mature leaf (320 µg cm−3; Table 1, Fig. 5B, C) and the Zn-deficient YFEL (310 µg cm−3; Table 1, Fig. 6B, C).

Fig. 5.

Zinc concentration of a mature leaf of tomato (adaxial surface from the Zn-sufficient treatment) to which droplets of Zn(NO3)2 had been applied. (A) Image of half a leaf captured using a digital camera. (B) Survey (overview) scan of the leaf in (A) using µ-XRF. (C) Detailed scan of the area indicated by the white rectangle in (B). (D) Projected Zn concentration along the vein from point A to point B as shown in (C). Brighter colours correspond to higher Zn concentrations. Scale bars = 1 mm.

Fig. 6.

Zinc concentration of the youngest fully expanded leaf (YFEL) of tomato (adaxial surface from the Zn-deficient treatment) to which droplets of Zn(NO3)2 had been applied. (A) Image of half a leaf captured using a digital camera. (B) Survey (overview) scan of leaf in (A) using µ-XRF. (C) Detailed scan of the area indicated by the white rectangle in (B). (D) Projected Zn concentration along the vein from point A to point B as shown in (C). Brighter colours correspond to higher Zn concentrations. At a distance >2 mm, concentrations were below the detection limit. Scale bars = 1 mm.

Redistribution of Zn within the leaf tissues

Although the foliar application of Zn often increased projected concentrations in the underlying tissues in tomato ∼>100-fold (and 2- to 5-fold in citrus) (Table 1), the subsequent redistribution of this Zn within the leaf tissues appeared to be limited.

Firstly, we considered how the concentration of Zn within the interveinal tissues changed as the distance from the droplet increased. This is important given that it is this Zn in the interveinal tissues that could potentially be loaded into the vascular tissues for further transport. Therefore, whilst avoiding higher-order veins (2° or 3°), projected volumetric concentrations were examined across a transect that encompassed the tissues to which the Zn-containing droplet had been applied (for the purposes of this analysis, these tissues are termed ‘interveinal’ although they still include lower-order (∼4–7°) veins (Fig. 7). For example, consider the YFEL of tomato supplied with Zn(NO3)2 on the adaxial surface (Fig. 7, and also see Fig. 4B, C). As expected, projected volumetric concentrations underneath the droplet were typically 100 µg cm−3 (Fig. 7B, C). However, it was noted that the tissue concentration of Zn decreased rapidly with increasing distance from the site of application. Indeed, assuming that this Zn droplet was 2 mm in diameter (data not shown, but see Supplementary Data Figs S1 and S4 for an example), the concentration of Zn in the interveinal tissues decreased to background levels within ∼1·5–3 mm of the edge of the droplet (Fig. 7, Supplementary Data Fig. S4). A similar trend was observed for YFELs of tomato supplied with ZnHN (Supplementary Data Fig. S5). Although the movement of Zn within the interveinal tissues was highly limited, it was also influenced by the treatment. Specifically, in leaves of Zn-deficient plants, the movement of Zn was restricted to an even greater extent (Fig. 8). In these Zn-deficient leaves, projected volumetric concentrations of Zn returned to background levels within ∼0·5–1 mm of the edge of the droplet [for Zn(NO3)2 see Fig. 8; for ZnHN see Supplementary Data Fig. S6].

Fig. 7.

Zinc concentration across an area of a tomato leaf (adaxial surface from the Zn-sufficient treatment) to which droplets of Zn(NO3)2 had been applied (see Fig. 4 also). (A) Detailed scan. (B) Close-up of the area indicated by the red rectangle in (A). (C) Concentration of Zn across the region indicated by the white dashed rectangle in (B). In (C) the horizontal dashed line represents the background concentration of Zn (Table 1). Brighter colours correspond to higher Zn concentrations.

Fig. 8.

Zinc concentration across a traverse of a tomato leaf (adaxial surface from the Zn-deficient treatment) to which droplets of Zn(NO3)2 had been applied (see also Fig. 6). (A) Detailed scan. (B) Concentration of Zn across the region indicated by the white dashed rectangle in (A). In (B) the horizontal dashed line represents the background concentration of Zn (Table 1). Brighter colours correspond to higher Zn concentrations.

Secondly, it was possible to examine the concentration of Zn within the vascular tissues immediately below the Zn-containing droplet. This analysis is important because it is the movement of Zn into these vascular tissues that allows subsequent loading into the higher-order veins for the wider movement of Zn. In this regard, it was noted that these lower-order (∼4–7°) veins typically contained a projected volumetric Zn concentration that was ∼2–10-fold higher than that of the surrounding tissues. For example, when Zn(NO3)2 was applied to the adaxial surface of YFELs of tomato, projected volumetric concentrations in the lower-order veins underneath the droplet were ∼2-fold higher than in the tissues immediately adjacent to them (Figs 7 and 8). Similarly, when Zn(NO3)2 (or ZnHN) was applied to the abaxial surface of Zn-sufficient YFELs of tomato, projected volumetric concentrations in the lower-order veins underneath the droplet (∼1000–2000 µg cm−3) were 10-fold higher than those in the tissues immediately adjacent to them (100–200 µg cm−3; Supplementary Data Figs S4, S5 and S6).

Thirdly, the movement of Zn away from the droplet within higher-order (2° and 3°) veins was examined. Although Zn moved a greater distance in the vascular tissues than in the interveinal tissues (e.g. Fig. 1), it could be seen that the concentration of Zn in the vascular tissues also decreased comparatively rapidly (in contrast, examine the movement of Zn within the vascular tissue of a root, shown in Supplementary Data Fig. S7). To further examine the movement of Zn within vascular tissues, regressions were fitted using eqn 1, where the strength coefficient (c) indicates how quickly the concentration of Zn in the vein decreases (higher values of c indicating a more rapid decrease in Zn). It was noted in all instances that the concentration of Zn within the vascular tissues decreased substantially within <5–10 mm to concentrations similar to background levels for the vascular tissues (Figs 1–6). Although the movement of Zn within the vascular tissues was limited, differences were observed between treatments. Examination of the values for c in Table 1 showed that the Zn status of the plant was the most important factor influencing the distance moved by Zn within the vascular tissues. For example, for YFELs of tomato that had had Zn(NO3)2 applied to the adaxial surface, the concentration of Zn within the vascular tissues decreased by 50 % after 1·4 mm for the Zn-sufficient plant (c = 0·49) but by 50 % after 0·1 mm for the Zn-deficient plant (c = 5·4) (Table 1, Figs 4 and 6).

Finally, we also examined the distribution of Zn within YFELs that had been sprayed with Zn(NO3)2 or ZnHN across the entire abaxial or adaxial surface (Supplementary Data Fig. S8). As expected, the movement of Zn into the leaf tissues was greater than when only single droplets were applied, with uptake of Zn greater for tomato than for citrus (Supplementary Data Fig. S8). Again, it was noted that the concentration of Zn was higher in the vascular tissues than in the interveinal tissues.

DISCUSSION

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to utilize µ-XRF for the in situ examination of Zn in hydrated and fresh leaves to which Zn in soluble and suspension forms has been applied. Foliar uptake of Zn uptake is considered to be a two-phase process: (1) passive diffusion through the leaf surface (penetration across the cuticle and cell walls of the epidermis); and (2) uptake of solutes in the leaf cells and/or phloem for transport (Fernández and Eichert, 2009). In the present study, the use of synchrotron-based µ-XRF has allowed an assessment of both the movement of Zn through the leaf surface into the underlying tissues and its subsequent redistribution within the leaf.

The overall pattern of the behaviour of foliar-applied Zn was similar regardless of the treatment imposed, although the different treatments did influence the extent to which these various processes occurred. Following its foliar application, Zn moved through the leaf surface, with the concentrations in the underlying tissues increasing by up to 5-fold in citrus or 600-fold in tomato (Table 1). Next, once the Zn had moved through the leaf surface, we then examined three processes that are of importance for the subsequent redistribution of Zn within the leaf: (1) the redistribution of Zn within the interveinal tissues themselves; (2) the movement of Zn from the interveinal tissues into the adjacent lower-order veins; and (3) the movement of Zn into the higher-order veins for its subsequent redistribution through the leaf. Firstly, the redistribution of Zn (away from the location of the foliar-applied Zn) through the interveinal tissues was found to be highly restricted, with projected volumetric concentrations of Zn decreasing to background levels within ≤3 mm of the edge of the Zn-containing droplet (Figs 7 and 8). Secondly, although this redistribution of Zn through the interveinal tissues was highly restricted, Zn was moved into the lower-order veins underlying the foliar-applied Zn: concentrations of Zn in these lower-order veins were up to ∼2- to 10-fold higher than in the surrounding interveinal tissues (Figs 7 and 8). Finally, as expected, after the Zn had been moved into the higher-order veins, the distance moved by the Zn was greater than that observed in the surrounding interveinal tissues (e.g. see Fig. 1). However, even within higher-order veins, the movement of Zn was comparatively restricted, with concentrations in these veins decreasing to concentrations similar to the background within 1–10 mm (Figs 1–6). Interestingly, Zn concentration peaks coincided with portions of the veins that intersect with other veins, which may be entry points for increased Zn loading into the vein. Further tracing examination is required to confirm this assumption.

Redistribution of Zn within tomato and citrus leaves is highly limited

As noted above, following its movement through the leaf surface, the movement of the foliar-applied Zn was highly restricted. This pattern of Zn movement in leaves is in contrast to that observed for Zn in roots (Supplementary Data Fig. S7) or in leaves for some other foliar-applied nutrients. For example, using autoradiography to study 32P applied to leaves of bean (Phaseolus vulgaris), Koontz and Biddulph (1957) found substantial translocation of P within 24 h (e.g. see Fig. 11 of Koontz and Biddulph, 1957). However, the limited movement of foliar-applied Zn observed in the present study is similar to that observed previously for Zn, with only 5–20 % of the Zn taken up following foliar fertilization typically remobilized within the phloem (Fernández et al., 2013). For example, Zhang and Brown (1999b) found that only 5·4 % of the Zn absorbed by the leaf was transported out of the treated leaves in pistachio (Pistachio vera). Similarly, Swietlik and LaDuke (1991) found no evidence of Zn movement from leaves of Citrus aurantium. A total of 120 d after foliar application to citrus, Sartori et al. (2008) reported that only 14 % of the absorbed Zn had been translocated from the applied leaves to other plant tissues. In a manner similar to the present study, other authors have used autoradiography to examine the spatial distribution of foliar-applied Zn. For example, Marešová et al. (2012) studied Zn in leaves of tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) and hop (Humulus lupulus) and found that >99 % of the foliar-applied Zn was retained within tissues to which it had been directly applied (by immersion in a ZnCl2 solution) and that <1 % was transported to non-immersed tissues. Similarly, when Wallihan and Heymann-Herschberg (1956) applied 65Zn as single drops to surfaces of citrus leaves, their autoradiograms indicate that there was comparatively little movement of the Zn, but the greatest movement occurred when the Zn-containing droplet was applied to the midrib. It is recognized that there would be high proportions of Zn droplets directly located on veins of leaves fully sprayed in the field. As a result, it may be hypothesized that the transport effectiveness of foliar absorbed Zn out of a treated leaf may be rate-limited by the Zn concentration gradient in the midrib, which is the cumulative product of the spatial distribution of the Zn uptake intensity and internal diffusivity of the Zn specific to leaf physiology/biochemistry and Zn chemical forms. This should be tested in further studies.

This very limited movement of foliar-applied Zn (observed in the present study but also previously by other authors) occurs for two reasons: (1) high binding capacity of leaf cells for Zn (Zhang and Brown, 1999a, b) and/or (2) limited/conditional mobility in the phloem (Marschner, 1995). Indeed, it is known that the negative charges of the cell wall and cuticle have a high affinity for Zn2+ and that, following its foliar application, much of the absorbed Zn is in exchangeable forms rather than soluble forms (Zhang and Brown, 1999a; Fernández et al., 2013). This is in contrast to Zn taken up by roots, which is largely complexed with ligands, including organic acids or amino acids (Cakmak, 2000; Haydon and Cobbett, 2007; Kopittke et al., 2011). While this strong binding of foliar-absorbed Zn limits its subsequent movement, this observation does not necessarily imply that foliar application of Zn cannot be effective in improving growth. Indeed, even though the redistribution of Zn observed in the present study was highly restricted, our experimental data for tomato indicate that it is still sufficeint to increase both shoot and root mass substantially in Zn-deficient plants when the whole leaf surfaces of two or three mature leaves were fully covered with foliar spray of ZnHN droplets in a follow-up glasshouse experiment (Y. Du, unpubl. data). Similarly, for wheat (Triticum aestivum) it was reported that whilst the translocation of foliar-applied Zn was small it was sufficient to improve growth (Haslett et al., 2001). Regardless, whilst translocation of Zn would indeed otherwise increase the potential for a whole-plant benefit, the application of foliar Zn would still have local benefits (e.g. see Zn concentrations when applied as a spray, shown in Supplementary Data Fig. S8). These may suggest that repeated application of soluble Zn fertilizers is necessary to achieve meaningful growth and agronomic effects in the field, through increasing spatial coverage of canopy or foliar surface area and/or temporal re-application across extended developmental stages, such as the flowering stage (Fernández et al., 2013).

Factors that influence the absorption of Zn and its redistribution

The plant species had a marked effect on the absorption of foliar-applied Zn, with the concentrations in the underlying tissues increased by an average of up to only 5-fold in citrus but up to 600-fold in tomato (Table 1). Indeed, in contrast to that observed with tomato (Table 1, Fig. 1), there were generally no significant effects on the movement of Zn in the higher-order veins of citrus leaves, regardless of the treated leaf surface or the form of the Zn that was applied (Table 1, Fig. 2). Reduced absorption of Zn into leaves of citrus results from the thickness of the cuticular wax layer on citrus leaves, this being an important barrier (Riederer and Schreiber, 1995).

The surface to which the Zn was applied (abaxial or adaxial) was also one of the important factors influencing the absorption of Zn, with the concentration of Zn in the underlying tissues ∼2-fold higher when applied to the abaxial leaf surface regardless of the Zn chemical form applied or the species (Table 1, Figs 1 and 4). In tomato, although stomata and trichomes are present on both the adaxial and abaxial surfaces, their density is substantially higher on the abaxial than the adaxial surface (Supplementary Data Table S3). This is particularly important given that the aqueous pathways (or polar pathways) for the penetration of inorganic ions (such as Zn2+) through the cuticle are located in the cuticular ledges at the base of trichomes, guard cells and cuticles over anticlinal cell walls of stomata (Schönherr, 2006). Similar observations have been reported by other authors, with the absorption of Ca and Na on the surface of stomatous leaf surfaces significantly higher than on astomatous leaf surfaces of apple (Malus domestica) (Schlegel and Schonherr, 2002; Burkhardt et al., 2012). For leaves of citrus, stomata are only present on the abaxial surface. However, in the present study the relative importance of application to adaxial surfaces versus abaxial surfaces in citrus was unclear due to the comparatively low movement of Zn through the surfaces of these leaves (Table 1).

As reported previously, plant Zn status was found to influence the movement of Zn within the leaf tissue, although it did not influence the initial movement of Zn through the leaf surface (Table 1). For example, in Zn-deficient plants the redistribution of Zn was restricted both in the interveinal tissues (Figs 7 and 8) but also in the higher-order veins (Figs 4 and 6). Firstly, the observation that Zn deficiency did not influence the initial absorption of Zn is in agreement with the findings of Erenoglu et al. (2002), who stated that the foliar absorption of 65Zn was not influenced by Zn nutritional status. The finding that the Zn status of the plant did impact upon the subsequent redistribution of the foliar-absorbed Zn is also in agreement with the previous observations that Zn is more easily mobilized in Zn-sufficient leaves than in Zn-deficient leaves (Longnecker and Robson, 1993). This limitation of foliar Zn movement in Zn-deficient leaves may be caused by the effects of Zn deficiency on cellular membrane structure and functions, such as the density and functionality of ion pumps. Zinc deficiency disrupts the integrity of leaf cell membranes and their permeability to inorganic ions (Cakmak, 2000). The impairments in the integrity of leaf cell membranes of Zn-deficient plants may also cause alterations in the activity of membrane-bound proton-pumping enzymes and ion channels (Cakmak, 2000), thus affecting nutrients across the plasma membranes. Zinc transporters such as ZIP4, cation diffusion facilitator (MTP1), heavy metal ATPase (HMA2, HMA4) and yellow stripe-like (YSL1, YSL3) proteins, which are primarily located in leaf cell membranes (Grotz and Guerinot, 2006; Waters et al., 2006), may be affected structurally and functionally in Zn-deficient leaves, thus limiting Zn loading into the phloem. In addition, cuticles and cell walls of leaves are strong sinks for Zn binding, resulting in low Zn mobilization out of the treated leaves, particularly under Zn deficiency conditions (Kannan and Charnel, 1986; Marschner, 1995; Zhang and Brown, 1999b).

The chemical form of the Zn was found to influence its absorption through the leaf surface, with tissue concentrations ∼2-fold higher when Zn(NO3)2 was used rather than ZnHN (Table 1). This is not unexpected given that the solubility of ZnHN in saturation phase is ∼30–50 mg Zn L−1 (Li et al., 2012), whilst Zn(NO3)2 was applied at 400 mgL−1. Given that foliar Zn absorption is a passive diffusion process driven by a concentration gradient (Fernández and Eichert, 2009), it is not surprising that Zn concentrations in leaves treated with Zn(NO3)2 were higher than in leaves to which the ZnHN suspension was applied. Importantly, the permeability of polar pathways in the cuticle is closely related to ambient humidity (Schönherr, 2001; Schönherr and Luber, 2001; Schreiber et al., 2001) and the dissolution of ZnHN would have only occurred at a relative humidity above its point of deliquescence (87 %). Given that the relative humidity during incubation was maintained >95 % in the present study, cuticle permeability would not have become a limiting factor for the penetration of Zn if it was available in aqueous phase on the leaves, and the dissolution of ZnHN would have been at its maximal rate.

In conclusion, in the present study we have provided quantitative data on the spatial distribution (absorption and short-distance movement) of Zn in hydrated and fresh leaves of tomato. Due to physiological differences in the leaves (particularly the cuticles), the absorption of the foliar-applied Zn differed substantially between tomato and citrus, with Zn concentrations in tissues underlying the Zn-containing droplet up to ∼600-fold higher than in the surrounding tissues for tomato but only 5-fold in citrus. Regardless of the treatment, once the Zn had been absorbed, there was comparatively little subsequent movement of the Zn within the leaf tissue. Indeed, within the interveinal tissues, Zn concentrations decreased to background levels within <3 mm from the Zn source. Despite the loading of Zn into the lower-order veins in the tissues underlying the Zn-containing droplet (with Zn concentrations in these lower-order veins being up to 10-fold higher than in the surrounding interveinal tissues), the movement of Zn within the higher-order veins was also limited (reducing to concentrations similar to the background within <5–10 mm). Movement of foliar-applied Zn within the leaf tissues was reduced even further in Zn-deficient leaves. The information provided here advances our understanding of the factors that influence the efficacy of foliar Zn fertilizers and their interactions with plant foliage characteristics.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary data are available online at www.aob.oxfordjournals.org and consist of the following. Table S1: treatments used to investigate the foliar absorption and short-distance movement of Zn. Table S2: bulk concentration of Zn in leaves of tomato and citrus. Table S3: Densities of stomata and trichomes on leaves of tomato and citrus. Fig. S1: abaxial surface of a youngest fully expanded leaf of Zn-sufficient tomato to which Zn(NO3)2 was applied. Fig. S2: adaxial surface of a youngest fully expanded leaf of Zn-sufficient tomato to which ZnHN was applied. Fig. S3: adaxial surface of a youngest fully expanded leaf of Zn-deficient tomato to which ZnHN was applied. Fig. S4: transect across the abaxial surface of a youngest fully expanded leaf of Zn-sufficient tomato to which Zn(NO3)2 was applied. Fig. S5: transect across the abaxial surface of a youngest fully expanded leaf of Zn-sufficient tomato to which ZnHN was applied. Fig. S6: Transect across the adaxial surface of a youngest fully expanded leaf of Zn-deficient tomato to which ZnHN was applied. Fig. S7: concentrations of Zn in the root of cowpea (Vigna unguiculata) exposed to 40 µm Zn in solution culture. Fig. S8: abaxial and adaxial surfaces of tomato and citrus leaves sprayed with Zn(NO3)2 and ZnHN.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the Australian Synchrotron for technique support of XFM beamline (AS131/XFMFI/5835) and Dr Lu Zhao for help with ICP analysis of Zn in tomato leaves. This work was supported by Australian Research Council (ARC) and AgriChem Liquid Fertilizers Pty Ltd (LP0989217) and the ARC Future Fellowship scheme (FT120100277 and LP130100741).

LITERATURE CITED

- Burkhardt J, Basi S, Pariyar S, Hunsche M. 2012. Stomatal penetration by aqueous solutions - an update involving leaf surface particles. New Phytologist 196: 774–787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cakmak I. 2000. Tansley Review No. 111. Possible roles of zinc in protecting plant cells from damage by reactive oxygen species. New Phytologist 146: 185–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cakmak I. 2008. Enrichment of cereal grains with zinc: agronomic or genetic biofortification? Plant and Soil 302: 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Eichert T, Goldbach GD. 2008. Equivalent pore radii of hydrophilic foliar uptake routes in stomatous and astomatous leaf surfaces – further evidence for a stomatal pathway. Physiologia Plantarum 132: 491–502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichert T, Kurtz A, Steiner U, Goldbach HE. 2008. Size exclusion limits and lateral heterogeneity of the stomatal foliar uptake pathway for aqueous solutes and water-suspended nanoparticles. Physiologia Plantarum 134: 151–160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erenoglu B, Nikolic M, Romheld V, Cakmak I. 2002. Uptake and transport of foliar applied zinc (65Zn) in bread and durum wheat cultivars differing in zinc efficiency. Plant and Soil 241: 25–57. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández V, Brown PH. 2013. From plant surface to plant metabolism: the uncertain fate of foliar-applied nutrients. Frontiers in Plant Science 4: 1–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández V, Eichert T. 2009. Uptake of hydrophilic solutes through plant leaves: current state of knowledge and perspectives of foliar fertilization. Critical Reviews in Plant Sciences 28: 36–38. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández V, Eichert T, Del Rio V, et al. 2008. Leaf structural changes associated with iron deficiency chlorosis in field-grown pear and peach: physiological implications. Plant and Soil 311: 161–172. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández V, Sotiropoulos T, Brown P. 2013. Foliar fertilization: scientific principles and field practices. Paris: International Fertilizer Association. [Google Scholar]

- Grotz N, Guerinot ML. 2006. Molecular aspects of Cu, Fe and Zn homeostasis in plants. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta 1763: 595–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haslett BS, Reid RJ, Rengel Z. 2001. Zinc mobility in wheat: uptake and distribution of zinc applied to leaves or roots. Annals of Botany 87: 379–386. [Google Scholar]

- Hauke V, Schreiber L. 1998. Ontogenetic and seasonal development of wax composition and cuticular transpiration of ivy (Hedera helix L.) sun and shade leaves. Planta 207: 67–75. [Google Scholar]

- Haydon MJ, Cobbett CS. 2007. Transporters of ligands for essential metal ions in plants. New Phytologist 174: 499–506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt EJ. 1966. Sand and water culture methods used in the study of plant nutrition. Farnham Royal, UK: Commonwealth Agricultural Bureaux. [Google Scholar]

- Huang L, Bell RW, Dell B, Woodward J. 2004. Rapid nitric acid digestion of plant material with an open-vessel microwave system. Communications in Soil Science and Plant Analysis 35: 427–440. [Google Scholar]

- Huang LB, Bell RW, Dell B. 2008. Evidence of phloem boron transport in response to interrupted boron supply in white lupin (Lupinus albus L. cv. Kiev Mutant) at the reproductive stage. Journal of Experimental Botany 59: 575–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huett DO, Maier NA, Sparrow LA, Piggott TJ. 1997. Vegetables. In: Reuter DJ, Robinson JBD. eds. Plant analysis: an interpretation manual. Collingwood, Australia: CSIRO, 385–464. [Google Scholar]

- IZiNCG 2004. Assessment of the risk of zinc deficiency in populations and options for its control. Food Nutrition Bulletin 25 (1 Suppl 2): S99–S203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kannan S, Charnel A. 1986. Foliar absorption and transport of inorganic nutrients. Critical Reviews in Plant Sciences 4: 341–375. [Google Scholar]

- Kinraide TB. 1999. Interactions among Ca2+, Na+ and K+ in salinity toxicity: quantitative resolution of multiple toxic and ameliorative effects. Journal of Experimental Botany 50: 1495–1505. [Google Scholar]

- Kirkham R, Dunn PA, Kuczewski AJ, et al. 2010. The Maia spectroscopy detector system: engineering for integrated pulse capture, low-latency scanning and real-time processing. AIP Conference Proceedings 1234: 240–243. [Google Scholar]

- Koontz H, Biddulph O. 1957. Factors affecting absorption and translocation of foliar applied phosphorus. Plant Physiology 32: 463–470. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopittke PM, Menzies NW, de Jonge MD, et al. 2011. in situ distribution and speciation of toxic Cu, Ni and Zn in hydrated roots of cowpea. Plant Physiology 156: 663–673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopittke PM, de Jonge MD, Menzies NW, et al. 2012. Examination of the distribution of arsenic in hydrated and fresh cowpea roots using two- and three-dimensional techniques. Plant Physiology 159: 1149–1158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopittke PM, de Jonge MD, Wang P, et al. 2014. Laterally resolved speciation of arsenic in roots of wheat and rice using fluorescence-XANES imaging. New Phytologist 201: 1251–1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li P, Xu ZP, Hampton MA, et al. 2012. Control preparation of zinc hydroxide nitrate nanocrystals and examination of the chemical and structural stability. Journal of Physical Chemistry C 116: 10325–10332. [Google Scholar]

- Lombi E, de Jonge MD, Donner E, et al. 2011. Fast x-ray fluorescence microtomography of hydrated biological samples. PLoS One 6: e20626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loneragan JF, Snowgall K, Robson AD. 1976. Remobilization of nutrients and its significance in plant nutrition. In: Wardlaw IF, Passioura JB. eds. Transport and transfer process in plants. New York: Academic Press, 463–469. [Google Scholar]

- Longnecker NE, Robson AD. 1993. Distribution and transport of zinc in plants. In: Robson AD. ed. Zinc in soils and plants: Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer, 79–91. [Google Scholar]

- Marešová J, Remenárová L, Horník M, Pipíška M, Augustín J, Lesný J. 2012. Foliar uptake of zinc by vascular plants: radiometric study. Journal of Radioanalytical and Nuclear Chemistry 292: 1329–1337. [Google Scholar]

- Marschner H. 1995. Mineral nutrition of higher plants. London: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Paterson DJ, de Jonge MD, Howard DL, et al. 2011. The X-ray fluorescence microscopy beamline at the Australian Synchrotron. AIP Conference Proceedings 1365: 219–222. [Google Scholar]

- Riederer M, Schreiber L. 1995. Waxes: the transport barriers of plant cuticles. In: Hamilton RJ. ed. Waxes: chemistry, molecular biology and functions. Dundee, UK: Oily Press, 130–156. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan CG. 2000. Quantitative trace element imaging using PIXE and the nuclear microprobe. International Journal of Imaging Systems and Technology 11: 219–230. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan CG, Jamieson DN. 1993. Dynamic analysis: on-line quantitative PIXE microanalysis and its use in overlap-resolved elemental mapping. Nuclear Instruments and Methods in Physics Research Section B: Beam Interactions with Materials and Atoms 77: 203–214. [Google Scholar]

- Sack L, Scoffoni C, McKown AD, et al. 2012. Developmentally based scaling of leaf venation architecture explains global ecological patterns. Nature Communications 3: 837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sartori RH, Boaretto AE, Villanueva FCA, Fernandes HMG. 2008. Foliar and radicular absorption of 65Zn and its redistribution in citrus plant. Revista Brasileira De Fruticultura 30: 523–527. [Google Scholar]

- Schilmiller AL, Last RL, Pichersky E. 2008. Harnessing plant trichome biochemistry for the production of useful compounds. Plant Journal 54: 702–711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlegel TK, Schonherr J. 2002. Selective permeability of cuticles over stomata and trichomes to calcium chloride. Acta Horticulturae (ISHS) 594: 91–96. [Google Scholar]

- Schönherr J. 2001. Cuticular penetration of calcium salts: effects of humidity, anions, and adjuvants. Journal of Plant Nutrition and Soil Science 164: 225–231. [Google Scholar]

- Schönherr J. 2006. Characterization of aqueous pores in plant cuticles and permeation of ionic solutes. Journal of Experimental Botany 57: 2471–2491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schönherr J, Luber M. 2001. Cuticular penetration of potassium salts: effects of humidity, anions, and temperature. Plant and Soil 236: 117–122. [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber L, Schönherr J. 1993. Determination of foliar uptake of chemicals: influence of leaf surface microflora. Plant, Cell and Environment 16: 743–748. [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber L, Skrabs M, Hartmann KD, Diamantopoulos P, Simanova E, Santrucek J. 2001. Effect of humidity on cuticular water permeability of isolated cuticular membranes and leaf disks. Planta 214: 274–282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi GR, Cai QS. 2009. Photosynthetic and anatomic responses of peanut leaves to zinc stress. Biologia Plantarum 53: 391–394. [Google Scholar]

- Swietlik D, LaDuke JV. 1991. Productivity, growth, and leaf mineral composition of orange and grapefruit trees foliar-sprayed with zinc and manganese. Journal of Plant Nutrition 14: 129–142. [Google Scholar]

- Vu DT, Huang LB, Nguyen AV, et al. 2013. Quantitative methods for estimating foliar uptake of zinc from suspension-based Zn chemicals. Journal of Plant Nutrition and Soil Science 176: 764–775. [Google Scholar]

- Wallihan EF, Heymann-Herschberg L. 1956. Some factors affecting absorption and translocation of zinc in citrus plants. Plant Physiology 31: 294–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters BM, Chu HH, DiDonato RJ, et al. 2006. Mutations in Arabidopsis Yellow Stripe-Like1 and Yellow Stripe-Like3 reveal their roles in metal ion homeostasis and loading of metal ions in seeds. Plant Physiology 141: 1446–1458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang QL, Brown PH. 1999a. The mechanism of foliar zinc absorption in pistachio and walnut. Journal of the American Society for Horticultural Science 124: 312–317. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang QL, Brown PH. 1999b. Distribution and transport of foliar applied zinc in pistachio. Journal of the American Society for Horticultural Science 124: 433–436. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.