Abstract

Background and Aims The development of plant secondary metabolites during early life stages can have significant ecological and evolutionary implications for plant–herbivore interactions. Foliar terpenes influence a broad range of ecological interactions, including plant defence, and their expression may be influenced by ontogenetic and genetic factors. This study investigates the role of these factors in the expression of foliar terpene compounds in Eucalyptus globulus seedlings.

Methods Seedlings were sourced from ten families each from three genetically distinct populations, representing relatively high and low chemical resistance to mammalian herbivory. Cotyledon-stage seedlings and consecutive leaf pairs of true leaves were harvested separately across an 8-month period, and analysed for eight monoterpene compounds and six sesquiterpene compounds.

Key Results Foliar terpenes showed a series of dynamic changes with ontogenetic trajectories differing between populations and families, as well as between and within the two major terpene classes. Sesquiterpenes changed rapidly through ontogeny and expressed opposing trajectories between compounds, but showed consistency in pattern between populations. Conversely, changed expression in monoterpene trajectories was population- and compound-specific.

Conclusions The results suggest that adaptive opportunities exist for changing levels of terpene content through ontogeny, and evolution may exploit the ontogenetic patterns of change in these compounds to create a diverse ontogenetic chemical mosaic with which to defend the plant. It is hypothesized that the observed genetically based patterns in terpene ontogenetic trajectories reflect multiple changes in the regulation of genes throughout different terpene biosynthetic pathways.

Keywords: Chemical defence, Eucalyptus globulus, seedlings, foliar terpenes, genetic variation, herbivory, monoterpene, ontogenetic trajectory, plant ontogeny, population divergence, secondary metabolite, sesquiterpene

INTRODUCTION

Ontogenetic development in plants results in changes in the expression of key plant traits (Barton and Koricheva, 2010) such as plant secondary metabolites (PSMs; Barton, 2007; Holeski et al., 2012; Barton and Hanley, 2013). Many PSMs play important roles in the defence of plants against natural enemies and understanding how PSMs and resistance vary across ontogenetic stages offers insight into the selective impacts of herbivores and pathogens on plant traits such as ‘who’ is acting as the selective force, ‘when’ is selection occurring and ‘what’ is the result of selection on the plant traits (e.g. directional or stabilizing selection; Boege and Marquis, 2005).

Patterns in chemical expression across ontogenetic stages appear variable. For example, as some plants age from seedling to juvenile through to adult stages there is an increase in the expression of PSMs (e.g. Elger et al., 2009) whilst others decrease with plant age (e.g. Goodger et al., 2006). Such variability in ontogenetic trajectories may be influenced by plant life-history strategy, investment in defence trait type (chemical, physical and/or tolerance), the type of herbivore or pathogen acting as the selective agent and the timing of enemy attack (Barton and Koricheva, 2010; Massad, 2013; Quintero and Bowers, 2013). The mechanisms behind the different ontogenetic patterns have been explained by two hypotheses. The herbivore selection theory predicts a high level of defence in juvenile plants, followed by a decrease as plants mature and become less susceptible to the reduction in fitness caused by these attacks (Bryant et al., 1992). A contrasting prediction based on the allocation theory suggests that the acquisition and allocation of resources limit the production of defensive secondary compounds in young plants, thereby resulting in an ontogenetic increase in defence (Herms and Mattson, 1992).

Terpenes are a large and diverse group of plant secondary metabolites, and can have pronounced effects on a wide range of ecological interactions. For example, terpenes can influence plant–animal interactions by influencing insect community composition (Xiao et al., 2012), acting as attractants for specific pollinators (Ibanez et al., 2010; Reisenman et al., 2010; Piechowski et al., 2011) or in plant defence (Lawler et al., 2000; Wiggins et al., 2003; Ott et al., 2011). They can mediate plant–plant interactions by having below-ground negative allelopathic effects (Singh et al., 2009; De Martino et al., 2010), affect ecosystem process through promoting fire (Ormeño et al., 2009; Zhao et al., 2011), and they can play important roles in microbial (Safaei-Ghomi and Batooli, 2010; Huang et al., 2012) and fungal interactions (Ludley et al., 2009; Kramer and Abraham, 2012). This is no better seen in the terpene-rich trees of the southern hemisphere genus Eucalyptus (Steinbauer, 2010; Myburg et al., 2014).

Eucalypts are the dominant tree species in many Australian ecosystems, ranging from dwarf mallee forms in high-altitude and semi-arid regions through to tall forest trees in wet forests (Williams and Brooker, 1997). Eucalypt foliage is high in concentration of PSMs including an array of mono- and sesquiterpene compounds (Boland et al., 1991; Brophy and Southwell, 2002; Külheim et al., 2011). These compounds are known to influence a range of interactions with invertebrate (Edwards et al., 1990, 1993; Steinbauer et al., 2004; Östrand et al., 2008; Steinbauer, 2010) and vertebrate (Lawler et al., 1999; Wiggins et al., 2003) herbivores. Terpene concentrations in eucalypts exhibit variation between and within populations (O’Reilly-Wapstra et al., 2002; Wallis et al., 2002; Andrew et al., 2005; Wiggins et al., 2006) and are highly heritable (Doran and Matheson, 1994; Andrew et al., 2005; O’Reilly-Wapstra et al., 2005b, 2011). Despite the ecological importance of eucalypts and the large number of terpene compounds in their foliage, few studies have examined ontogenetic variation of terpene expression across distinct life stages (e.g. seedlings, juvenile and adult stages; O’Reilly-Wapstra et al., 2007; Goodger and Woodrow, 2009) or within a single life stage (McArthur et al., 2010; Goodger et al., 2013a, b; Padovan et al., 2013). In addition, few studies in any system have examined the genetic basis to ontogenetic variation in PSMs (Barton, 2007; O’Reilly-Wapstra et al., 2007; Holeski et al., 2009, 2012). To the best of our knowledge, no studies have explicitly documented genetic variation in the ontogenetic expression of foliar terpenes within the early stages of seedling development (i.e. is there a genetically based difference in the early ontogenetic development of chemical defence within the species). By placing ontogenetic patterns in a genetic framework, we can better understand the evolutionary implications of the development of ecologically important PSMs. In this study, we report on variation in the ontogenetic trajectories of 14 different mono- and sesquiterpene compounds during early development of Eucalyptus globulus seedlings, and identify genetic differences in these trajectories at the population and family levels.

Eucalyptus globulus has been the subject of considerable research on the quantitative genetic control of important plant traits, including terpenes (O’Reilly-Wapstra et al., 2005a, 2011; Külheim et al., 2011; Wallis et al., 2011). This species is heteroblastic and genetic variation has been detected both within and between populations at the juvenile coppice (O’Reilly-Wapstra et al., 2002) and adult (Wallis et al., 2011) leaf stages, and strong correlations between foliar concentrations across life-history stages (juvenile and adult foliage types) have been reported at the population level (O’Reilly-Wapstra et al., 2007). However, little is known of the pattern of expression of terpenes in the important early life stage of the seedling (McArthur et al., 2010; Goodger et al., 2013a), as is the genetically based variation in ontogenetic development in terpenes. Focusing on the development of terpenes during the seedling phase is important as this is when E. globulus are often most vulnerable to herbivory and hence can have significant impacts on tree growth and fitness (Farrow et al., 1994; O’Reilly-Wapstra et al., 2012). Furthermore, few studies have investigated plant defence in the cotyledon stage, and this is important to determine how plant defence changes during the earliest ontogenetic stage (Barton and Koricheva, 2010). Three specific questions were addressed: (1) Is there ontogenetic variation in foliar terpene content of early-stage seedlings? (2) Is there genetically based variation at the population and family level in the ontogenetic trajectory of terpene concentration? (3) Do mono- and sesquiterpenes follow the same ontogenetic trajectory?

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Trial design

The natural range of Eucalyptus globulus has been classified into 13 genetically differentiated geographical races (Dutkowski and Potts, 1999). Populations within these races have been defined as trees growing within 10 km of each other (Potts and Jordan, 1994), and we define family as progeny derived from open-pollinated seed collected from one native tree within a population. We chose three populations from three different geographical races for this study, each represented by ten families. The chosen populations express inherently low and high concentrations of terpenes that confer resistance to mammal browsing (O’Reilly-Wapstra et al., 2004, 2005a). The two Tasmanian populations chosen were St Helens in the north-east of Tasmania (41°15′S, 148°19′E) with low PSM foliar chemistry and Blue Gum Hill in the south-east of Tasmania (43°03′S, 146°52′E) with relatively high PSM foliar chemistry (O’Reilly-Wapstra et al., 2004). A third population, Jeeralang North in the Strzelecki Ranges of Victoria (38°19′S, 146°52′E) also has higher levels of PSM foliar chemistry and low mammal browsing susceptibility (O’Reilly-Wapstra et al., 2004) and was chosen to represent a population that is from a distinct molecular group, to encompass the broad spatial genetic structure of this species (Jones et al., 2013). The trial was grown in a common environment glasshouse that was well ventilated, with no additional lighting, with average temperatures ranging from 21 to 24 °C during the day, and 13·5 to 16·2 °C overnight. Seeds were sown in family lots in October 2009, in polystyrene boxes on soil covered in 0·5 cm vermiculite. Standard low phosphorus potting mix was used, containing slow-release fertilizer (N/P/K 17 : 1·6 : 8·7). These family trays were randomized in the glasshouse and plants grown for 28 d until cotyledons were fully expanded. Cotyledon-stage seedlings were pricked out into separate cells in 8 × 7-cell plastic seed trays. Fourteen cotyledon-stage seedlings per family were pricked out into two consecutive rows in these trays and these two rows comprised a ‘family plot’. Ten such plots of each of the 30 families were pricked out and arranged into ten replicate blocks within the glasshouse. Each family was thus represented as a family plot of 14 plants, with the plot arranged in a random position within each replicate block (3 populations×10 families×14 seedlings×10 replicates = 4200 seedlings in total). Over the course of the experiment, replicates were moved three times to different positions in the glasshouse. The remaining cotyledon-stage seedlings (not used in the replicated design) were harvested to investigate their chemical content. Approximately 60 cotyledon pairs, pooled within family (25 families; insufficient sample size for five families) were harvested, discarding the stem, and placed into a freezer in labelled plastic bags for later chemical analysis.

Leaf harvest

It is important to separate the effect of ontogeny from leaf physiological ageing (Lawrence et al., 2003), as they are two different processes operating within the plant, and are often not separated (Diggle, 2002; Goodger et al., 2013b). Leaf age was accounted for by sampling seedlings at multiple times through their growth, by separating consecutive leaf pairs and then comparing the same aged leaves from different nodes across different harvests of different seedlings within a family plot sampled at different times. Leaves at each node are opposite at this seedling stage and were grouped into pairs (two leaves) to represent a specific ontogenetic and physiological ageing stage (Fig. 1). Seasonal variation (e.g. in photoperiod) is also known to influence terpene content within the Myrtaceae (Simmons and Parsons, 1987; Leach and Whiffin, 1989; Wildy et al., 2000), but although seasonal change could not be fully controlled in this experiment, it is expected to be relatively small and would be confounded in the leaf age by ontogeny interaction term.

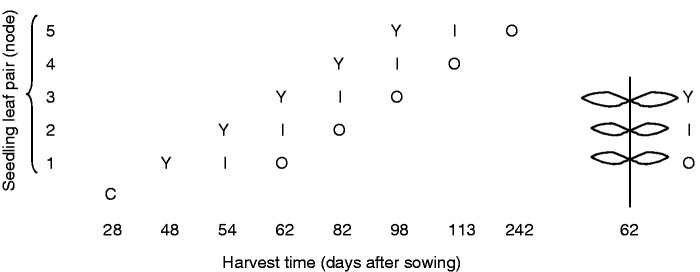

Fig. 1.

Experimental design of the trial indicating the time of leaf harvest, beginning with cotyledon-stage seedlings (C). The first five consecutive true leaf pairs are the ontogenetic stages examined. Leaf pairs were identified as either young (Y), intermediate (I) or old (O) in age to represent the physiological ageing of each leaf. The illustration on the right is an example of the harvested seedling at 62 d with three nodes and three leaf pairs. Each leaf pair per harvest was represented by 30 E. globulus families from three populations (total no. of samples = 450).

Harvesting of seedling leaves began 20 d after sowing and continued for a period of 4 months as each leaf pair became fully expanded (48, 54, 62, 82, 98, 113 d). A final harvest was collected at 8 months (242 d; Fig. 1). As is typical in eucalypt literature (e.g. Brooker and Kleinig, 1999; Goodger et al., 2013a), we define seedlings as the combined cotyledon stage and growth up to five nodes. All leaves were morphologically characteristic of the seedling growth stage of E. globulus, and harvested before the onset of the relatively stable juvenile leaf stage (Jordan et al., 2000). Seedlings were destructively harvested to avoid the possibility of induction affecting subsequent terpene expression. At each harvest, one of the 14 seedlings in each family plot was selected for harvest, with the exception of the first two harvests where the leaves from four seedlings were combined due to their small size. Seedling leaves were cut from the stem using fine tip scissors, placed into labelled bags and kept in a cool box with ice until being transferred to a freezer for later chemical analysis. The bottom leaf pairs on older plants senesced naturally, and so to maintain a balanced statistical design only the top three leaf pairs from each plant were analysed. They were identified as young, intermediate or old in age (Fig. 1).

Foliar terpene analysis

At each harvest time, leaves for chemical analysis were pooled by leaf pair and pooled for each family across replicates to increase the sample quantity (i.e. 3 populations × 10 families = 30 bags of leaves for each leaf pair). Environmental variation within the glasshouse was minimal for the duration of the experiment and therefore pooling each family across replicates was the preferred method to boost sample size, as it still allowed for testing genetic variation at both the population and the family level.

Eight monoterpenes (1,8-cineole, α-pinene, limonene, α-terpineol, α-terpinyl acetate, p-cymene, terpinene-4-ol, 2-hydroxy-1,8-cineole) and six sesquiterpenes (aromadendrene, bicyclogermacrene, alloaromadendrene, α-gurjunene, β-caryophyllene, α-humulene) were quantified. Terpenes were extracted from leaves following a method modified from O’Reilly-Wapstra et al. (2004). Results for 1,8-cineole and α-pinene were expressed in milligrams per gram of dry weight (mg g−1 d. wt) after calibration with reference standards. Total terpenes and the remaining compounds were expressed as mg g−1 d. wt cineole equivalents. Leaves were cut into small pieces (approx. 3–5 mm2) using scissors and approx. 0·25 g weighed in a 20-mL polypropylene tube. Due to the low terpene content of cotyledon-stage seedlings and first true leaves, the fresh leaf sample was doubled to approx. 0·5 g. Entire leaves (including mid-rib) were used for the first three harvests, after which the leaf mid-rib was not included. Fifteen millilitres of dichloromethane (DCM) spiked with an internal standard of n-heptadecane (C17H36) was added to each tube and left for 1 h. The tubes were then placed in an ultrasonic bath to sonicate for 30 min. The extract was decanted into a 50-mL tube and capped. This process was repeated twice more, pooling extracts. The pooled extracts were then mixed thoroughly. A pipette was used to take approx. 1 mL from each sample and placed in high-performance liquid chromatography vials and refrigerated until analysis. The extracts were then analysed by gas chromatography (GC) and GC mass spectrometry (GC-MS). GC analyses were carried out on a Varian-450 GC system with Varian 1177 split/splitless injector and flame ionization detector (FID). The column was a Varian ‘Factor Four’ VF-5 ms (30-m×0·25-mm internal diameter and 0·25-µm film). Carrier gas was nitrogen at 1 mL min−1 constant flow mode. Injections of 1 µL were made using a Varian CP-8400 autosampler and a Varian 1177 split/splitless injector with a 15 : 1 split ratio. The injector temperature was 220 °C, and the FID temperature was 300 °C. The column oven was held at 60 °C for 1 min, then ramped to 220 °C at 6 °C min−1, then to 300 °C at 25 °C min−1 with a 5-min hold at the final temperature. Data were processed with Varian Galaxie software. Preliminary GC-MS analyses on several representative samples were carried out on a Varian 3800 GC system coupled to Varian 1200 triple quadrupole mass spectrometer in single quadrupole mode. The GC conditions were as above except the carrier gas was helium. The ion source was held at 230 °C, and the transfer line at 310 °C. The range from m/z 35 to 350 was scanned four times per second. Data were processed with Varian Chemstation software. Initial compound identifications were made by comparison of both Kovats indices and mass spectra with commercial databases (NIST MS database) and an in-house specialist terpene MS database. The GC processing method was then constructed once the target peaks for integration had been selected. Individual peak areas were then assigned automatically by the Galaxie software, but all assigned peaks were visually inspected to ensure accurate peak integrations and identifications had occurred. Peak area ratios to the internal standard peak were determined, as was the percentage contribution of each targeted peak to the total terpene profile.

Prior to each harvest, plant height (taken from the cotyledon node to the base of the apical leaf), lamina length and leaf shape (length to width ratio) were measured to estimate plant growth. Lamina length and leaf shape were assessed on the top leaf pairs of each seedling. One seedling per family per replicate was measured (n = 300) 1 d prior to each harvest and is presented in Supplementary Data Fig. S1. There was no growth or leaf morphology data for the final harvest at 242 d.

Statistical analysis

All terpene values were log transformed to meet assumptions of normality and homoscedasity. Total mono- and sesquiterpene content was calculated by the sum of the individual compounds. Terpene content of true leaves was analysed for the effects of ontogeny, leaf age and population and family nested within population genetic effects using a mixed-model procedure in SAS (PROC MIXED; SAS Institute Inc. 2002–2008). The fixed effects in the model were population, ontogeny, leaf age and all their interaction terms. Family nested within population and its two-way interaction terms with ontogeny and leaf age were the random effects in the model. These random terms provided the error terms to test for population and associated interaction terms using Wald’s F-test. To estimate the percentage variance explained by the fixed and random terms, all components were fitted into a randomized mixed model (PROC MIXED of SAS) and the variance components for each variable were estimated. Canonical discriminant analysis (PROC DISCRIM of SAS) was used to summarize the multivariate changes in leaf terpene data using the unique combinations of ontogeny (leaf node), age and population as the grouping factor. This analysis was based on nine individual terpene compounds (limonene, α-terpineol, α-humulene, α-gurjunene and bicyclogermacrene were removed due to their high intercorrelations with other compounds).

Variation in seedling height, lamina length and leaf shape was analysed by fitting a mixed model (PROC MIXED of SAS) with population, harvest day and their interaction as the fixed terms and replicate, family within population and the interaction term harvest day by family within population as the random terms. Variation in terpene content of cotyledon-stage seedlings was analysed by fitting a fixed effects model (PROC MIXED of SAS) with population as the fixed term with the random term representing the variation between family pools within populations. While not embedded in the seedling ontogeny experimental design, the families were grown randomly positioned in the same area of the glasshouse, allowing us to make comparisons between terpene content of cotyledon-stage seedlings and the first true leaf pair using a paired t-test.

RESULTS

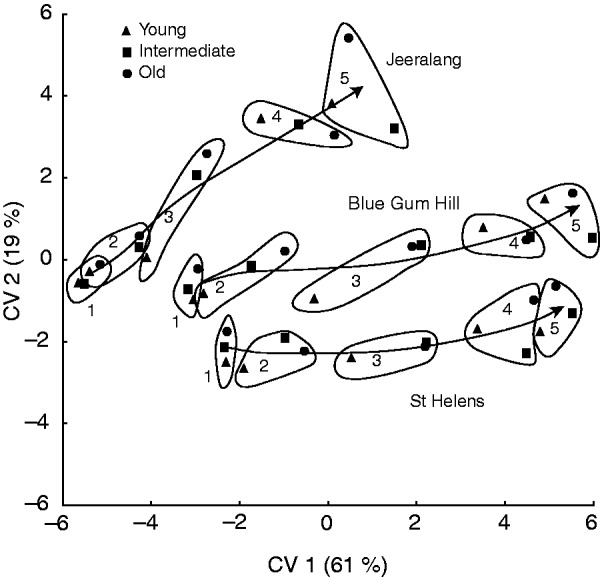

There were highly significant effects of ontogeny, genetics (at both population and family level), leaf age and their interactions on the majority of the terpene compounds in true leaves (Table 1 and Supplementary Data Table S1). Variance components show that population explained the greatest percentage of the variation for total terpenes, and mono- and sesquiterpenes (Table 2). While ontogenetic effects were the next most important factor in explaining variance for total terpenes and sesquiterpenes, family within population was next most important for monoterpenes. Leaf age explained only a small percentage of the terpene variation (Table 2) and this was consistent with the canonical discriminant analysis where all three leaf ages effectively followed the same trajectory with an increase in terpene content through ontogeny (Fig. 2). The canonical discriminant analysis based on nine individual compounds (Fig. 2) showed a strong ontogenetic influence on terpene composition, with population being next most important. Canonical variate (CV) 1 explained the ontogenetic change, accounting for 61 % of the variation (F396,3475 = 11·1, P < 0·001) in terpenes between groups. CV 2 accounted for population differences as well as a component of the ontogenetic change in the Jeeralang population and explained 19 % of the variation (F344,3105 = 7·1, P < 0·001). CV 3 (figure not shown) accounted for 10 % of the variation (F294,2730 = 4·9, P < 0·001), although it mainly explains population variation and did not embody any ontogenetic change.

Table 1.

Results of the mixed model analysis examining the genetic, ontogenetic and leaf age effects on terpene content in the first five consecutive true leaf pairs of E. globulus seedlings

| Population (F2,27) | Ontogeny (F4,108) | Leaf age (F2,54) | Population × Ontogeny (F8,108) | Population × Leaf age (F4,54) | Leaf age × Ontogeny (F8,210) | Population × Leaf age × Ontogeny (F16,210) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total terpenes | 29·0*** | 101·0*** | 32·8*** | 10·6*** | 2·0 | 11·9*** | 3·0*** |

| Total monoterpenes | 34·1*** | 47·0*** | 22·8*** | 13·2*** | 1·6 | 7·8*** | 2·5** |

| Total sesquiterpenes | 44·6*** | 238·2*** | 32·6*** | 8·9*** | 0·4 | 8·6*** | 1·6 |

| Monoterpenes | |||||||

| 1,8-Cineole | 27·3*** | 77·8*** | 23·0*** | 13·2*** | 1·4 | 7·1*** | 1·9* |

| α-Pinene | 23·5*** | 30·7*** | 52·2*** | 7·1*** | 1·4 | 7·2*** | 2·4** |

| Limonene | 33·7*** | 81·2*** | 94·4*** | 9·0*** | 0·7 | 13·7*** | 2·9*** |

| α-Terpineol | 17·4*** | 49·9*** | 22·1*** | 15·7*** | 1·5 | 5·5*** | 1·4 |

| α-Terpinyl acetate | 2·4 | 39·0*** | 1·5 | 17·3*** | 0·7 | 2·6* | 1·6 |

| p-Cymene | 35·3*** | 14·5*** | 12·3*** | 52·7*** | 8·4*** | 13·7*** | 4·5*** |

| Terpinene-4-ol | 33·4*** | 36·8*** | 21·5*** | 6·8*** | 2·0 | 7·8*** | 2·6*** |

| 2-Hydroxy-1,8-cineole | 10·8*** | 22·8*** | 67·9*** | 8·0*** | 8·2*** | 72·8*** | 0·9 |

| Sesquiterpenes | |||||||

| Aromadendrene | 53·7*** | 473·7*** | 10·8*** | 4·9*** | 1·2 | 1·5 | 1·2 |

| Bicyclogermacrene | 50·2*** | 227·4*** | 49·1*** | 5·0*** | 1·2 | 31·4*** | 3·3*** |

| Alloaromadendrene | 64·1*** | 382·2*** | 15·5*** | 2·8** | 0·7 | 0·9 | 0·6 |

| α-Gurjunene | 55·4*** | 304·7*** | 65·5*** | 2·4* | 5·0** | 23·0*** | 2·4** |

| β-Caryophyllene | 0·5 | 302·7*** | 74·8*** | 6·2*** | 0·8 | 4·7*** | 1·0 |

| α-Humulene | 1·9 | 266·2*** | 97·8*** | 1·3 | 4·4** | 8·44*** | 2·9*** |

Compounds are listed in order of dominance within terpene classes. Family within population and its interaction with ontogeny and leaf age were used as the error terms (see Supplementary Data Table S1 for significance of these random terms). Total mono- and sesquiterpene content was calculated by the sum of their individual compounds. Significance of effects: *P < 0·05, **P < 0·01, ***P < 0·001; blank, not significant.

Table 2.

Results of a fully random model showing the percentage contribution of genetic, ontogenetic and leaf age variance component estimates for total terpenes and the two major terpene classes in the first five consecutive true leaf pairs of E. globulus seedlings

| Effect | Total terpenes | Monoterpenes | Sesquiterpenes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Population | 35·0*** | 46·5*** | 39·8*** |

| Ontogeny | 22·0*** | 8·2*** | 35·8*** |

| Leaf age | 1·9*** | 1·4*** | 1·1*** |

| Population × Ontogeny | 6·6*** | 9·2*** | 3·7*** |

| Population × Leaf age | 0·0 | 0·0 | 0·0 |

| Leaf age × Ontogeny | 4·1*** | 2·5*** | 1·7*** |

| Population × Leaf age × Ontogeny | 2·4*** | 1·9** | 0·3 |

| Family(Population) | 11·5*** | 13·0*** | 8·3*** |

| Family(Population) × Ontogeny | 3·2** | 3·3** | 2·5*** |

| Family(Population) × Leaf age | 0·0 | 0·0 | 0·0 |

| Residual | 13·3*** | 13·9*** | 6·8*** |

Total mono- and sesquiterpene content was calculated by the sum of their individual compounds. Significance of effects: **P < 0·01, ***P < 0·001; blank, not significant.

Fig. 2.

Results of the canonical discriminant analysis based on nine terpene compounds showing the chemical trajectory for each E. globulus population, and grouped by leaf age (triangles, circles, squares) and ontogenetic stage (1–5). Within each population, there are clear groupings of ontogeny (represented by the first five consecutive true leaf pairs), despite different leaf ages. The continuous lines for each population show the average across leaf age for each ontogenetic stage (arrows indicate directionality). Cotyledon-stage seedlings were not included in this analysis.

These combined results indicate the importance of genetic and ontogenetic effects on these compounds in the early seedling stages of E. globulus. Leaf age showed a significant two-way interaction with ontogeny, and a three-way interaction with ontogeny and population (Table 1). The two-way interaction may be explained by a one node difference in the young leaves where they showed an ontogenetic change earlier (at node 3) than the older leaves (data not shown). The significant three-way interaction was due to the failure of the St Helens population to reach higher terpene levels in later ontogeny (data not shown). The large effect (F-value) of leaf age by ontogeny interaction on 2-hydroxy-1,8-cineole content is explained by a rapid increase in the terpene content of the ‘old’ leaf pair at the final harvest (day 242) in Jeeralang (data not shown).

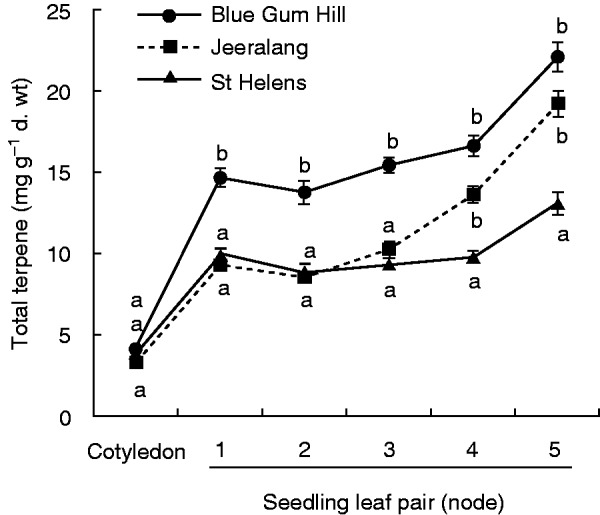

The ontogenetic change in terpene content among the three E. globulus populations varied between terpene compounds. The two Tasmanian populations (Blue Gum Hill and St Helens) showed substantial differences in absolute total terpene and monoterpene content, but they shared a similar magnitude and direction of change through ontogeny (Figs 2–4). The mainland Australian population (Jeeralang), however, differed in the magnitude of change and the direction of trajectory through ontogeny (Figs 2 and 3). This pattern is clear in the development of total terpenes where Jeeralang seedlings initially began their development similar to St Helens but then rapidly increased to express levels more similar to Blue Gum Hill later in ontogeny (from leaf pair 4; Fig. 3). Total terpene content increased from the first to the fifth seedling leaf pair by 7·44 mg g−1 d. wt in Blue Gum Hill (1·5-fold increase) and by 3·13 mg g−1 d. wt in St Helens (1·3-fold increase), compared with a large 9·93 mg g−1 d. wt increase in Jeeralang (2·1-fold increase). The points of rapid change in leaf terpene content did not coincide with the continuous pattern of change in lamina length or leaf shape with node (Supplementary Data Fig. S1B and C). This suggests that the trends in leaf terpene content and leaf morphology throughout early development are independent.

Fig. 3.

Population variation in the ontogenetic development of total foliar terpene in E. globulus seedlings from the cotyledon-stage (C) to node 5. Ontogenetic stage is represented by cotyledons and the first five consecutive true leaf pairs. The figure shows different ontogenetic trajectories of the mainland Australian population, Jeeralang, compared with the two Tasmanian populations, St Helens and Blue Gum Hill. Letters that differ on each ontogenetic trajectory indicate values that are significantly different within population (α = 0.05 after Tukey–Kramer adjustment for multiple comparisons).

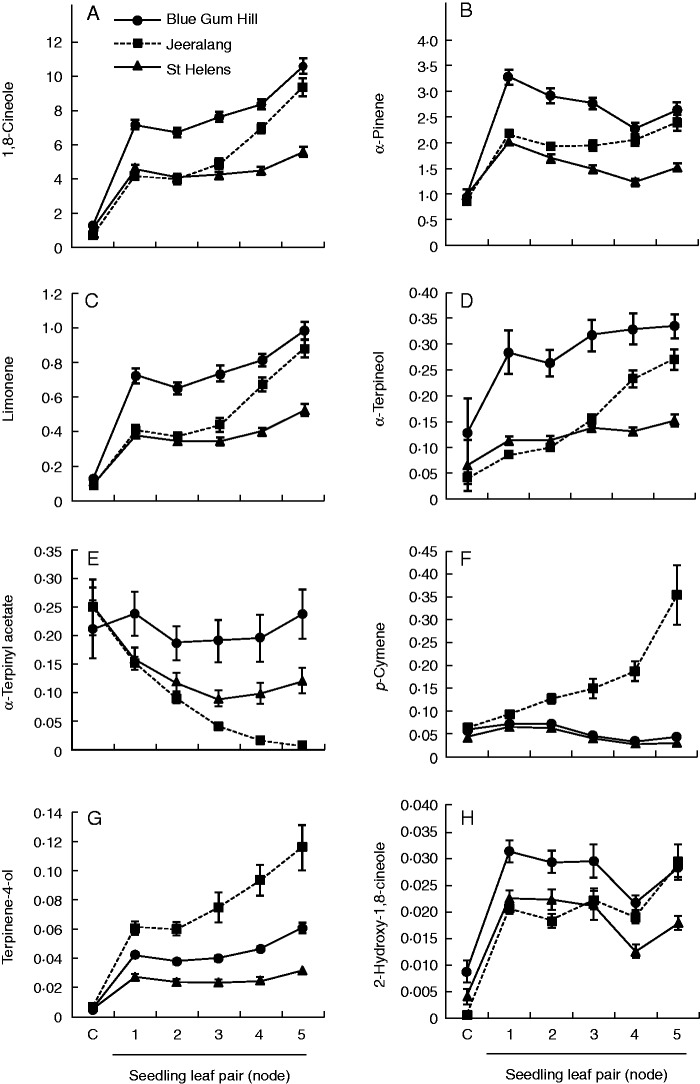

Fig. 4.

Population variation in the early ontogenetic development of eight monoterpene compounds in E. globulus seedlings from the cotyledon-stage (C) to node 5. Least square means and standard errors are based on families represented by a bulk sample across replicates (n = 10). Ontogenetic stage is represented by cotyledons and the first five consecutive true leaf pairs. 1,8-Cineole and α-pinene are expressed as mg g−1 d. wt, whilst all other compounds are expressed as equivalents of 1,8-cineole (mg g−1 d. wt). Mixed model analysis of these results is shown in Table 1.

There were significant population by ontogeny interactions for all terpenes (except α-humulene) in the true leaves, and these showed consistent trends but with differences in the timing and rate of change. p-Cymene was the exception as one population (Jeeralang) differed in the direction of ontogenetic development from the others (Fig. 4). This result was noted by the high population by ontogeny interaction effect in this compound (Table 1). The two Tasmanian populations remained stable in p-cymene content whereas Jeeralang increased after the second ontogenetic stage (Fig. 4F). In contrast, the monoterpenes 1,8-cineole, limonene and α-terpineol (Fig. 4A, C, D) showed similar increases through ontogeny in all populations, but with differences in the timing and rate of change between populations. Decreasing levels were evident in α-terpinyl acetate with a sharp change in Jeeralang, relatively no change in Blue Gum Hill and an intermediate pattern in St Helens (Fig. 4E). The monoterpene α-pinene (Fig. 4B) also initially decreased in content in all populations, but then increased at different rates. The monoterpene terpinene-4-ol (Fig. 4G) showed a similar population ranking to p-cymene with a rapid increase in Jeeralang, whereas the Tasmanian population remained low and was relatively stable. The monoterpene 2-hydroxy-1,8-cineole (Fig. 4H) had a low content in all populations, with very slight decreases in content through ontogeny.

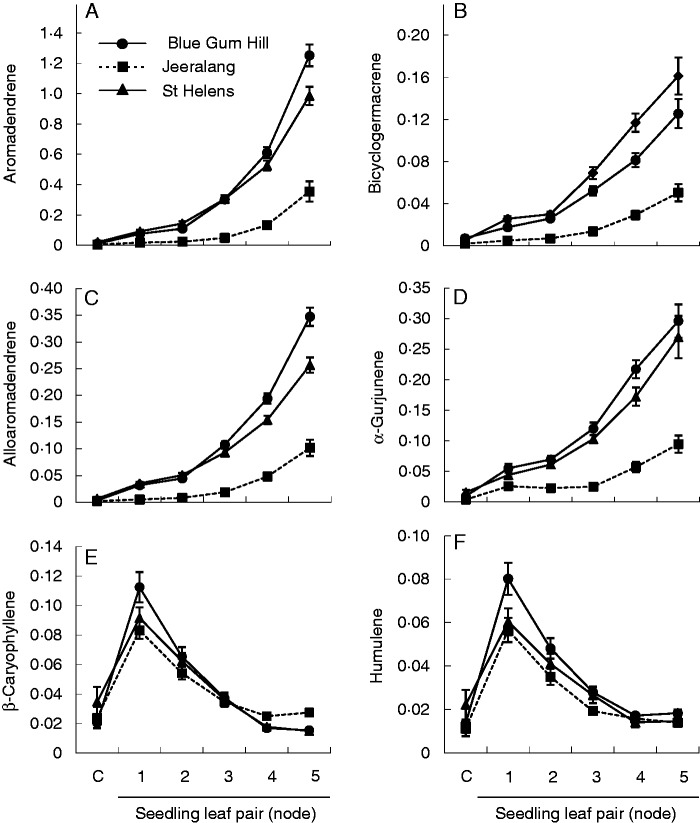

The pattern of change in the sesquiterpenes is explained by both population and ontogeny, as evidenced by the high percentage variation explained by these two factors (Table 2). The strong effect of ontogeny is reflected by the responsiveness of the Tasmanian populations to ontogeny (Fig. 5A–D). Jeeralang moved in the same direction, but there were delayed levels of change in aromadendrene, alloaromadendrene, bicyclogermacrene and α-gurjunene. What is most marked in Fig. 5 is the movement of β-caryophyllene and α-humulene in an opposing trajectory to the other sesquiterpenes (Fig. 5E, F). Populations expressed tighter patterns across ontogeny in these compounds. As a consequence of the opposing trajectories, there was a change in the dominance of sesquiterpene compounds throughout seedling leaf ontogeny.

Fig. 5.

Population variation in the early ontogenetic development of six sesquiterpene compounds in E. globulus seedlings from the cotyledon stage (C) to node 5. Least square means and standard errors are based on families represented by a bulk sample across replicates (n = 10). Ontogenetic stage is represented by cotyledons and the first five consecutive true leaf pairs. Compounds are expressed as equivalents of 1,8-cineole (mg g−1 d. wt). Mixed model analysis of these results is shown in Table 1.

Cotyledon-stage seedlings expressed none of the terpene compounds or only low levels (see Supplementary Data Table S2) and the paired t-test showed content to be significantly different from that the first leaf pair (P > 0·05; Fig. 4A–D, G, H; Fig. 5), except in the monoterpenes α-terpinyl acetate and p-cymene where content was not different from that of the first true leaf pairs (P > 0·05; Fig. 4E, F). Significant population differences at the cotyledon stage were only evident for 1,8-cineole, 2-hydroxy-1,8-cineole and bicyclogermacrene (Table S2). Despite not being significant, many monoterpene compounds showed the same population ranking at the cotyledon-stage seedlings to the true leaves (Fig. 4A, D, F, H), but was less so in the sesquiterpenes (Fig. 5A, C)

DISCUSSION

Genetically based ontogenetic variation in plants has been documented in morphological and reproductive traits (Wiltshire et al., 1998; Jordan et al., 1999; Dechaine et al., 2014) and is evident in foliar chemical traits, as shown here and in other studies (Rehill et al., 2006; O’Reilly-Wapstra et al., 2007; Holeski et al., 2012). Whilst ontogenetic variation in foliar terpene expression has been documented in eucalypts (McArthur et al., 2010; Goodger et al., 2013a, b), this is the first study to show such variation within a genetic framework, at the early stages of eucalypt development. Furthermore, we teased apart the effects of plant genetics, ontogenetic development and leaf age on the expression of mono- and sesquiterpene compounds in an ecologically dominant tree species. This is one of the few studies in any system to pull apart these important factors. We showed that genetic effects (at both the population and the family level) and ontogeny contributed the most to terpene variation in E. globulus seedlings with the Tasmanian populations responding differently from the mainland Australian population. A key finding was evidence that there are differential patterns in the ontogenetic development both between and within the two major terpene classes, mono- and sesquiterpenes. Sesquiterpenes showed a more rapid response and with opposing ontogenetic trajectories in different compounds.

From the development of the first true leaves, variation was seen at both levels of the genetic hierarchy (i.e. population and family within population) with genotypes showing not only differences in absolute amounts of terpenes but also in the manner they changed through ontogeny. The genetic variation seen at the family level within each population is a significant finding as it signals the potential for the ontogenetic trajectories to evolve. These results highlight the potential for selection to act on ontogenetic patterns of change in terpene compounds, to create an ontogenetic chemical mosaic with which to defend the seedling (sensu Iason et al., 2011), and this can vary spatially (e.g. Singer and McBride, 2012) and be under strong genetic control (Holeski et al., 2012).

Many of the individual compounds and the canonical discriminant analysis (terpene composition) indicate that the mainland Australian population Jeeralang expresses a different ontogenetic trajectory from the two Tasmanian populations, St Helens and Blue Gum Hill. Molecular and quantitative genetic studies show that the Tasmanian E. globulus populations have evolved to be significantly different from mainland lineages such as represented by Jeeralang (Steane et al., 2006; Jones et al., 2013). Different chemotypes between mainland and Tasmanian populations noted by Wallis et al. (2011) based on adult leaf (see also O’Reilly-Wapstra et al., 2013) suggest that the populations may involve quite different ontogenetic trajectories as well. In this study, the quantitative differences in the ontogenetic expression of terpenes in populations may reflect different evolutionary histories, with varying selective pressures, such as environmental conditions or levels of herbivory, at different developmental stages (Barton, 2007).

Seedling stages have been shown to have important roles in community structure and dynamics and seedling defence may determine subsequent patterns of plant–herbivore interactions (Barton and Hanley, 2013; Quintero and Bowers, 2013). The quantitative changes demonstrated during seedling ontogeny of E. globulus in this study also have the potential for such ecological consequences. For example, O’Reilly-Wapstra et al. (2005a) showed that a foliar terpene increase of 6·9 mg g−1 d. wt reduced brushtail possum herbivory. In the current study, the increase in total terpene content from the first to the fifth leaf pair (node) of seedlings exceeded this level in both Jeeralang and Blue Gum Hill populations, thus providing potential effects on mammalian herbivory within short developmental stages. Cotyledon-stage seedlings showed a lack of genetically based variation in the majority of terpene compounds, suggesting that this developmental stage is not subject to the same diversifying selective pressures. The overall low terpene investment at the cotyledon stage (except for α-terpinyl acetate) followed by an increase in newly emerging seedling foliage has also been documented in other eucalypt studies (e.g. Goodger et al., 2007; McArthur et al., 2010) and suggests that defence at this early developmental stage is not a priority. This is consistent with the strategy to escape the threat from herbivory by producing many small seeds for mast seedling establishment and rapid growth at this early establishment phase, rather than chemical defence (Herms and Mattson, 1992; Hanley, 1998; Kelly and Sork, 2002). The monoterpene α-terpinyl acetate may play an important functional role in this early growth stage because of high expression in cotyledon-stage seedlings followed by a decline through ontogeny. This role may, for example, involve defence against bacteria and fungi (Silva et al., 2011).

There were clear differences in the way mono- and sesquiterpenes responded to ontogeny. Overall, monoterpenes showed gradual and relatively slow increases in content, whereas sesquiterpenes were more responsive with rapid changes through ontogeny. In addition, there were clear opposing trajectories within sesquiterpenes with two compounds, β-caryophyllene and α-humulene, declining in content. Differential ontogenetic change in terpene compounds has been previously observed in Eucalyptus, both between (Goodger et al., 2013b) and within mono- and sesquiterpene classes (McArthur et al., 2010; Goodger et al., 2013a) and strongly reflects terpene biosynthetic origins. Mono- and sesquiterpenes originate from two separate biosynthetic pathways: the deoxyxylulose phosphate/methylerythritol pathway for the monoterpenes and the mevalonic acid pathway for the sesquiterpenes (Huber and Bohlmann, 2004). The precursors produced in these pathways are then modified by a class of enzymes, known as terpene synthases (TPS), to produce a varied range of terpene structures that are often further modified by secondary processes to produce a diverse range of plant terpenes (Huber and Bohlmann, 2004; Degenhardt et al., 2009; Dewick, 2009). Quantitative variation in individual compounds may be determined by several factors including the number of different TPS in gene families, the fact that many TPS produce a group of products and the ability of plants to regulate the expression of TPS genes (Huber and Bohlmann, 2004).

Many compounds showed tight relationships in their ontogenetic trajectories, particularly those that share a common biosynthetic precursor (Keszei et al., 2010), for example the monoterpenes 1,8-cineole, limonene and α-terpineol (Fig. 4A, C, D), the sesquiterpene compounds aromadendrene, alloaromadendrene, bicyclogermacrene and α-gurjunene (Fig. 5A–D), and β-caryophyllene and α-humulene (Fig. 5E, F). Across the monoterpenes (except p-cymene), the two Tasmanian populations expressed differences in absolute levels through ontogeny, although heir magnitude of change appeared similar, with terpene content changing with the same trajectory. The mainland Australian population, Jeeralang, by contrast, showed a distinct trajectory with the increases in terpene levels occurring at different rates from the Tasmanian populations. The differences in ontogenetic trajectories of the Tasmanian and the mainland Australian populations involve both mono- and sesquiterpene compounds and appears to be due to differences in the regulation of genes which control steps that occur both early and late in the biosynthetic pathways. An example is the ontogenetic increase in the content of the Jeeralang population in the sesquiterpenes aromadendrene, alloaromadendrene, bicyclogermacrene and α-gurjunene, which consistently lagged behind the Tasmanian populations. The similar expression of the three populations in remaining sesquiterpenes, β-caryophyllene and α-humulene, however, suggests that the two latter compounds are not under the same genetic control as the other four. An example of different gene regulation within the monoterpene biosynthetic pathway is the observed rapid decrease in α-terpinyl acetate content in the mainland population Jeeralang. This pattern suggests a marked down-regulation of a gene(s) specifically affecting its synthesis during early E. globulus ontogeny (Fig. 4E). This decline was less evident in the Tasmanian populations, particularly Blue Gum Hill. α-Terpinyl acetate is at its highest levels in the cotyledons, and the rapid decline in levels at subsequent nodes is countered by an increase in α-terpineol. α-Terpinyl acetate is derived from the acetylation of α-terpineol (see Fähnrich et al., 2012), a process which appears to be rapidly undertaken at the cotyledon stage of all provenances. We suggest that this production of α-terpinyl acetate from α-terpineol may have been so rapid during this ontogenetic stage that levels of α-terpineol remained relatively low. While the opposing pattern of ontogenetic change, particularly evident in Jeeralang, may represent a down-regulation of genes controlling this conversion, the possibility cannot be dismissed that it could be the result of back conversion of α-terpinyl acetate to α-terpineol by hydrolysation as the Jeeralang plants mature (see Dewick, 2009).

The contrasting ontogenetic trajectories observed for sesquiterpenes is an important finding and demonstrates how differently compounds can behave. The sesquiterpenes with cyclopropane carbon skeletons (aromadendrene, alloaromadendrene, bicyclogermacrene and α-gurjunene; Keszei et al., 2010) show a tight relationship between compounds with an increasing ontogenetic trajectory. In contrast, the sesquiterpenes with non-cyclopropane carbon skeletons, β-caryophyllene and α-humulene (Fig. 5E, F), exhibited increased synthesis in the first leaf pair, followed by a rapid decline as subsequent leaves developed. Given their structural similarities, an explanation for the two apparent groupings of sesquiterpene compounds is that they are produced by at least two different sesquiterpene synthases. This result is consistent with molecular studies where quantitative trait loci (QTL) for the four sesquiterpenes with positive ontogenetic trajectories were shown to be co-located on the one linkage group (O’Reilly-Wapstra et al., 2011). The two compounds showing a declining trajectory (β-caryophyllene and α-humulene) are known to be produced from a single sesquiterpene synthase in cotton (Yang et al., 2013) and hops (Wang et al., 2008). The remainder of compounds, however, are likely to be a product of the same multi-product sesquiterpene synthase, originating from a common precursor (Keszei et al., 2010). QTL for β-caryophyllene and α-humulene have not yet been identified. This is not the first documented case of the declining patterns of β-caryophyllene and α-humulene through ontogeny, as shown in a study of terpene expression in Salvia officinalis (Dudai et al., 1999). The opposing trajectories of these two sesquiterpene groups provide evidence to support the existence of differential transcription regulation of single versus multi-product sesquiterpene synthases through E. globulus ontogeny. In an evolutionary context, opposing ontogenetic trajectories in terpene compounds may be a product of selection in response to herbivory or pathogen, where some compounds are more useful to defend the plant at particular stages of growth. This strategy allows plants to avoid expending resources on defence when herbivores or pathogens are absent (Simms and Fritz, 1990). For example, Iason et al. (2011) show an invertebrate and two vertebrate herbivores to be probable selective agents at different life stages on several terpene compounds in Scots pine. Studies in other systems have shown β-caryophyllene to have roles in herbivore (Köllner et al., 2008; Huang et al., 2013) and pathogen (Sabulal et al., 2006; Huang et al., 2012) defence. From this evidence we may hypothesize that the initial high content of this compound in the first leaf pairs of E. globulus reflects a short-lived contribution of β-caryophyllene to defence.

In conclusion, we show diverse ontogenetic trajectories by different mono- and sesquiterpene compounds in E. globulus seedlings, with genetic control in ontogenetic trajectories occurring at both the population and the family level. The biosynthetic pathways can explain correlated patterns of terpene change and pleiotropy involving positive and negative changes through ontogeny, with changes in the genetically based regulation of genes appearing to occur within the different pathways. This combined evidence highlights the importance of incorporating genetics and ontogeny in studies of chemical defence. Changing ontogenetic patterns has long been recognized as a key mode of evolution in plants (Barton and Hanley, 2013; Quintero et al., 2013; Dechaine et al., 2014; Hoan et al., 2014), including Eucalyptus (Hudson et al., 2014), but this is one of the few studies in plants (Holeski et al., 2012; Moore et al., 2014) to demonstrate a genetic basis to the different ontogenetic trajectories in chemicals associated with plant defence. The evidence presented here suggests that there exists adaptive opportunities for divergence within species to occur not only through constitutive changes in PSMs, but in ontogenetic trajectories, with the potential to create a spatio-temporal chemical mosaic for plant defence.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary data are available online at www.aob.oxfordjournals.org and consist of the following. Table S1. Significance of random terms in the mixed model analysis used to analyse the terpene attributes at the family level. Table S2. Summary of mean values of terpene attributes determined for E. globulus cotyledon-stage seedlings and the average across all five seedling leaf pairs. Figure S1. Population variation in E. globulus seedling height, leaf length and leaf shape at each assessment time at the top node.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Comments from anonymous reviewers greatly improved the manuscript. We thank Greg Jordan for advice on the experimental design, Hugh Fitzgerald for extraction of foliar terpenes and Natasha Wiggins for assistance in sample preparation for extraction. Paul Tilyard, Helen Stephens, Chi Nghiem, David Bell and Ildiko Zivol helped with potting cotyledon-stage seedlings and picking of the first two harvests. We also thank Ian Cummings and Tracey Winterbottom for maintaining the glasshouse environment and watering the trial. Support for this project came from the CRC for Forestry and an ARC grant to J.O.R-W. (DP120102889).

LITERATURE CITED

- Andrew RL, Peakall R, Wallis IR, Wood JT, Knight EJ, Foley WJ. 2005. Marker-based quantitative genetics in the wild? The heritability and genetic correlation of chemical defenses in Eucalyptus. Genetics 171: 1989–1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton KE. 2007. Early ontogenetic patterns in chemical defense in Plantago (Plantaginaceae): genetic variation and trade-offs. American Journal of Botany 94: 56–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton KE, Hanley ME. 2013. Seedling–herbivore interactions: insights into plant defence and regeneration patterns. Annals of Botany 112: 643–650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton KE, Koricheva J. 2010. The ontogeny of plant defense and herbivory: characterizing general patterns using meta-analysis. American Naturalist 175: 481–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boege K, Marquis RJ. 2005. Facing herbivory as you grow up: the ontogeny of resistance in plants. Trends in Ecology & Evolution 20: 441–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boland DJ, Brophy JJ, House APN. 1991. Eucalyptus leaf oils – use, chemistry, distillation and marketing. Melbourne: ACIAR, CSIRO, Inkata Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brooker MIH, Kleinig DA. 1999. Field guide to eucalypts, Vol. 1, revised edn Melbourne: Bloomings Books. [Google Scholar]

- Brophy JJ, Southwell IA. 2002. Eucalyptus chemistry. In: Coppen JJW, ed. Medicinal and aromatic plants – industrial profiles. eucalyptus: the genus Eucalyptus. London: Taylor & Francis Inc., 102–160. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant JP, Reichardt PB, Clausen TP, Provenza FD, Kuropat PJ. 1992. Woody plant–mammal interactions. In: Rosenthal GA, Berenbaum MR, eds. Herbivores: their interactions with plant metabolites. New York: Academic Press, 344–371. [Google Scholar]

- De Martino L, Mancini E, De Almeida LFR, De Feo V. 2010. The antigerminative activity of twenty-seven monoterpenes. Molecules 15: 6630–6637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dechaine JM, Brock MT, Iniguez-Luy FL, Weinig C. 2014. Quantitative trait loci × environment interactions for plant morphology vary over ontogeny in Brassica rapa. New Phytologist 201: 657–669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Degenhardt J, Köllner TG, Gershenzon J. 2009. Monoterpene and sesquiterpene synthases and the origin of terpene skeletal diversity in plants. Phytochemistry 70: 1621–1637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dewick PM. 2009. Medicinal natural products: a biosynthetic approach, 3rd edn Chichester: John Wiley & Sons Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Diggle PK. 2002. A developmental morphologist’s perspective on plasticity. Evolutionary Ecology 16: 267–283. [Google Scholar]

- Doran JC, Matheson AC. 1994. Genetic parameters and expected gains from selection for monoterpene yields in Petford Eucalyptus camaldulensis. New Forests 8: 155–167. [Google Scholar]

- Dudai N, Lewinsohn E, Larkov O, et al. 1999. Dynamics of yield components and essential oil production in a commercial hybrid sage (Salvia officinalis × Salvia fruticosa cv. Newe Ya'ar No. 4). Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 47: 4341–4345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutkowski GW, Potts BM. 1999. Geographic patterns of genetic variation in Eucalyptus globulus ssp. globulus and a revised racial classification. Australian Journal of Botany 47: 237–263. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards PB, Wanjura WJ, Brown WV, Dearn JM. 1990. Mosaic resistance in plants. Nature 347: 434. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards PB, Wanjura WJ, Brown WV. 1993. Selective herbivory by Christmas beetles in response to intraspecific variation in Eucalyptus terpenoids. Oecologia 95: 551–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elger A, Lemoine DG, Fenner M, Hanley ME. 2009. Plant ontogeny and chemical defence: older seedlings are better defended. Oikos 118: 767–773. [Google Scholar]

- Fähnrich A, Brosemann A, Teske L, Neumann M, Piechulla B. 2012. Synthesis of ‘cineole cassette’ monoterpenes in Nicotiana section Alatae: gene isolation, expression, functional characterization and phylogenetic analysis. Plant Molecular Biology 79: 537–553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrow RA, Floyd RB, Neumann FG. 1994. Inter-provenance variation in resistance of Eucalyptus globulus juvenile foliage to insect feeding. Australian Forestry 57: 65–68. [Google Scholar]

- Goodger JQD, Woodrow IE. 2009. The influence of ontogeny on essential oil traits when micropropagating Eucalyptus polybractea. Forest Ecology and Management 258: 650–656. [Google Scholar]

- Goodger JQD, Gleadow RM, Woodrow IE. 2006. Growth cost and ontogenetic expression patterns of defence in cyanogenic Eucalyptus spp. Trees – Structure and Function 20: 757–765. [Google Scholar]

- Goodger JQD, Choo TYS, Woodrow IE. 2007. Ontogenetic and temporal trajectories of chemical defence in a cyanogenic eucalypt. Oecologia 153: 799–808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodger JQD, Heskes AM, Woodrow IE. 2013a. Contrasting ontogenetic trajectories for phenolic and terpenoid defences in Eucalyptus froggattii. Annals of Botany 112: 651–659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodger JQD, Mitchell MC, Woodrow IE. 2013b. Differential patterns of mono- and sesquiterpenes with leaf ontogeny influence pharmaceutical oil yield in Eucalyptus polybractea R.T. Baker. Trees – Structure and Function 27: 511–521. [Google Scholar]

- Hanley ME. 1998. Seedling herbivory, community composition and plant life history traits. Perspectives in Plant Ecology, Evolution and Systematics 1: 191–205. [Google Scholar]

- Herms DA, Mattson WJ. 1992. The dilemma of plants: to grow or defend. Quarterly Review of Biology 67: 283–335. [Google Scholar]

- Hoan RP, Ormond RA, Barton KE. 2014. Prickly poppies can get pricklier: ontogenetic patterns in the induction of physical defense traits. PLoS One 9: e96796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holeski LM, Kearsley MJC, Whitham TG. 2009. Separating ontogenetic and environmental determination of resistance to herbivory in cottonwood. Ecology 90: 2969–2973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holeski LM, Hillstrom ML, Whitham TG, Lindroth RL. 2012. Relative importance of genetic, ontogenetic, induction, and seasonal variation in producing a multivariate defense phenotype in a foundation tree species. Oecologia 170: 695–707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang M, Sanchez-Moreiras AM, Abel C, et al. 2012. The major volatile organic compound emitted from Arabidopsis thaliana flowers, the sesquiterpene (E)-β-caryophyllene, is a defense against a bacterial pathogen. New Phytologist 193: 997–1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X, Xiao Y, Köllner TG, et al. 2013. Identification and characterization of (E)-β-caryophyllene synthase and α/β-pinene synthase potentially involved in constitutive and herbivore-induced terpene formation in cotton. Plant Physiology and Biochemistry 73: 302–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber D, Bohlmann J. 2004. Terpene synthases and the mediation of plant-insect ecological interactions by terpenoids: a mini-review. In: Cronck Q, Whitton J, Ree R, Taylor I, eds. Plant adaptation: molecular genetics and ecology. Ottawa, Ontario: NRC Research Press, 70–81. [Google Scholar]

- Hudson CJ, Freeman JS, Jones RC, et al. 2014. Genetic control of heterochrony in Eucalyptus globulus. G3: Genes, Genomes, Genetics 4: 1235–1245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iason GR, O’Reilly-Wapstra JM, Brewer MJ, Summers RW, Moore BD. 2011. Do multiple herbivores maintain chemical diversity of scots pine monoterpenes? Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 366: 1337–1345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibanez S, Dötterl S, Anstett MC, et al. 2010. The role of volatile organic compounds, morphology and pigments of globeflowers in the attraction of their specific pollinating flies. New Phytologist 188: 451–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones RC, Steane DA, Lavery M, Vaillancourt RE, Potts BM. 2013. Multiple evolutionary processes drive the patterns of genetic differentiation in a forest tree species complex. Ecology and Evolution 3: 1–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan GJ, Potts BM, Wiltshire RJE. 1999. Strong, independent, quantitative genetic control of the timing of vegetative phase change and first flowering in Eucalyptus globulus ssp. globulus (Tasmanian Blue Gum). Heredity 83: 179–187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan GJ, Potts BM, Chalmers P, Wiltshire RJE. 2000. Quantitative genetic evidence that the timing of vegetative phase change in Eucalyptus globulus ssp. globulus is an adaptive trait. Australian Journal of Botany 48: 561–567. [Google Scholar]

- Kelly D, Sork VL. 2002. Mast seeding in perennial plants: why, how, where? Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 33: 427–447. [Google Scholar]

- Keszei A, Brubaker CL, Carter R, Köllner T, Degenhardt J, Foley WJ. 2010. Functional and evolutionary relationships between terpene synthases from Australian Myrtaceae. Phytochemistry 71: 844–852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Köllner TG, Held M, Lenk C, et al. 2008. A maize (E)-β-caryophyllene synthase implicated in indirect defense responses against herbivores is not expressed in most American maize varieties. Plant Cell 20: 482–494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kramer R, Abraham WR. 2012. Volatile sesquiterpenes from fungi: what are they good for? Phytochemistry Reviews 11: 15–37. [Google Scholar]

- Külheim C, Yeoh SH, Wallis IR, Laffan S, Moran GF, Foley WJ. 2011. The molecular basis of quantitative variation in foliar secondary metabolites in Eucalyptus globulus. New Phytologist 191: 1041–1053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawler IR, Eschler BM, Schliebs DM, Foley WJ. 1999. Relationship between chemical functional groups on Eucalyptus secondary metabolites and their effectiveness as marsupial antifeedants. Journal of Chemical Ecology 25: 2561–2573. [Google Scholar]

- Lawler IR, Foley WJ, Eschler BM. 2000. Foliar concentration of a single toxin creates habitat patchiness for a marsupial folivore. Ecology 81: 1327–1338. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence R, Potts BM, Whitham TG. 2003. Relative importance of plant ontogeny, host genetic variation, and leaf age for a common herbivore. Ecology 84: 1171–1178. [Google Scholar]

- Leach GJ, Whiffin T. 1989. Ontogenetic, seasonal and diurnal variation in leaf volatile oils and leaf phenolics of Angophora costata. Australian Systematic Botany 2: 99–111. [Google Scholar]

- Ludley KE, Robinson CH, Jickells S, Chamberlain PM, Whitaker J. 2009. Potential for monoterpenes to affect ectomycorrhizal and saprotrophic fungal activity in coniferous forests is revealed by novel experimental system. Soil Biology and Biochemistry 41: 117–124. [Google Scholar]

- Massad TJ. 2013. Ontogenetic differences of herbivory on woody and herbaceous plants: a meta-analysis demonstrating unique effects of herbivory on the young and the old, the slow and the fast. Oecologia 172: 1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McArthur C, Loney P, Davies NW, Jordan GJ. 2010. Early ontogenetic trajectories vary among defence chemicals in seedlings of a fast-growing eucalypt. Austral Ecology 35: 157–166. [Google Scholar]

- Moore BD, Andrew RL, Külheim C, Foley WJ. 2014. Explaining intraspecific diversity in plant secondary metabolites in an ecological context. New Phytologist 201: 733–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myburg AA, Grattapaglia D, Tuskan GA, et al. 2014. The genome of Eucalyptus grandis. Nature 510: 356–362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Reilly-Wapstra JM, McArthur C, Potts BM. 2002. Genetic variation in resistance of Eucalyptus globulus to marsupial browsers. Oecologia 130: 289–296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Reilly-Wapstra JM, McArthur C, Potts BM. 2004. Linking plant genotype, plant defensive chemistry and mammal browsing in a Eucalyptus species. Functional Ecology 18: 677–684. [Google Scholar]

- O’Reilly-Wapstra JM, Potts BM, McArthur C, Davies NW. 2005a. Effects of nutrient variability on the genetic-based resistance of Eucalyptus globulus to a mammalian herbivore and on plant defensive chemistry. Oecologia 142: 597–605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Reilly-Wapstra JM, Potts BM, McArthur C, Davies NW, Tilyard P. 2005b. Inheritance of resistance to mammalian herbivores and of plant defensive chemistry in a Eucalyptus species. Journal of Chemical Ecology 31: 519–537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Reilly-Wapstra JM, Humphreys JR, Potts BM. 2007. Stability of genetic-based defensive chemistry across life stages in a Eucalyptus species. Journal of Chemical Ecology 33: 1876–1884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Reilly-Wapstra JM, Freeman JS, Davies NW, Vaillancourt RE, Fitzgerald H, Potts BM. 2011. Quantitative trait loci for foliar terpenes in a global eucalypt species. Tree Genetics and Genomes 7: 485–498. [Google Scholar]

- O’Reilly-Wapstra JM, McArthur C, Potts BM. 2012. Natural selection for anti-herbivore plant secondary metabolites: a Eucalyptus system. In: Iason GI, Dicke M, Hartley S, eds. The ecology of plant secondary metabolites: genes to global processes. London: Cambridge University Press, 10–33. [Google Scholar]

- O’Reilly-Wapstra JM, Miller AM, Hamilton MG, Williams D, Glancy-Dean N, Potts BM. 2013. Chemical variation in a dominant tree species: population divergence, selection and genetic stability across environments. PLoS One 8: e58416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ormeño E, Céspedes B, Sánchez IA, et al. 2009. The relationship between terpenes and flammability of leaf litter. Forest Ecology and Management 257: 471–482. [Google Scholar]

- Östrand F, Wallis IR, Davies NW, Matsuki M, Steinbauer MJ. 2008. Causes and consequences of host expansion by Mnesampela privata. Journal of Chemical Ecology 34: 153–167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ott DS, Yanchuk AD, Huber DPW, Wallin KF. 2011. Genetic variation of Lodgepole pine, Pinus contorta var. latifolia, chemical and physical defenses that affect Mountain pine beetle, Dendroctonus ponderosae, attack and tree mortality. Journal of Chemical Ecology 37: 1002–1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padovan A, Keszei A, Foley WJ, Külheim C. 2013. Differences in gene expression within a striking phenotypic mosaic Eucalyptus tree that varies in susceptibility to herbivory. BMC Plant Biology 13: 29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piechowski D, Dötterl S, Gottsberger G. 2011. Pollination biology and floral scent chemistry of the Neotropical chiropterophilous Parkia pendula. Plant Biology 12: 172–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potts BM, Jordan GJ. 1994. The spatial pattern and scale of variation in Eucalyptus globulus ssp. globulus: variation in seedling abnormalities and early growth. Australian Journal of Botany 42: 471–492. [Google Scholar]

- Quintero C, Bowers MD. 2013. Effects of insect herbivory on induced chemical defences and compensation during early plant development in Penstemon virgatus. Annals of Botany 112: 661–669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quintero C, Barton KE, Boege K. 2013. The ontogeny of plant indirect defenses. Perspectives in Plant Ecology, Evolution and Systematics 15: 245–254. [Google Scholar]

- Rehill BJ, Whitham TG, Martinsen GD, Schweitzer JA, Bailey JK, Lindroth RL. 2006. Developmental trajectories in cottonwood phytochemistry. Journal of Chemical Ecology 32: 2269–2285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisenman CE, Riffell JA, Bernays EA, Hildebrand JG. 2010. Antagonistic effects of floral scent in an insect–plant interaction. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 277: 2371–2379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabulal B, Dan M, Anil JJ, et al. 2006. Caryophyllene-rich rhizome oil of Zingiber nimmonii from South India: Chemical characterization and antimicrobial activity. Phytochemistry 67: 2469–2473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safaei-Ghomi J, Batooli H. 2010. Chemical composition and antimicrobial activity of the volatile oil of Eucalyptus sargentii Maiden cultivated in central Iran. International Journal of Green Pharmacy 4: 174–177. [Google Scholar]

- Silva SM, Abe SY, Murakami FS, Frensch G, Marques FA, Nakashima T. 2011. Essential oils from different plant parts of Eucalyptus cinerea F. Muell. ex Benth. (Myrtaceae) as a source of 1,8-cineole and their bioactivities. Pharmaceuticals 4: 1535–1550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons D, Parsons RF. 1987. Seasonal variation in the volatile leaf oils of two Eucalyptus species. Biochemical Systematics and Ecology 15: 209–215. [Google Scholar]

- Simms EL, Fritz RS. 1990. The ecology and evolution of host-plant resistance to insects. Trends in Ecology and Evolution 5: 356–360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer MC, McBride CS. 2012. Geographic mosaics of species’ association: a definition and an example driven by plant–insect phenological synchrony. Ecology 93: 2658–2673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh HP, Kaur S, Mittal S, Batish DR, Kohli RK. 2009. Essential oil of Artemisia scoparia inhibits plant growth by generating reactive oxygen species and causing oxidative damage. Journal of Chemical Ecology 35: 154–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steane DA, Conod N, Jones RC, Vaillancourt RE, Potts BM. 2006. A comparative analysis of population structure of a forest tree, Eucalyptus globulus (Myrtaceae), using microsatellite markers and quantitative traits. Tree Genetics and Genomes 2: 30–38. [Google Scholar]

- Steinbauer MJ. 2010. Latitudinal trends in foliar oils of eucalypts: environmental correlates and diversity of chrysomelid leaf-beetles. Austral Ecology 35: 204–213. [Google Scholar]

- Steinbauer MJ, Schiestl FP, Davies NW. 2004. Monoterpenes and epicuticular waxes help female autumn gum moth differentiate between waxy and glossy Eucalyptus and leaves of different ages. Journal of Chemical Ecology 30: 1117–1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallis IR, Watson ML, Foley WJ. 2002. Secondary metabolites in Eucalyptus melliodora: field distribution and laboratory feeding choices by a generalist herbivore, the common brushtail possum. Australian Journal of Zoology 50: 507–519. [Google Scholar]

- Wallis IR, Keszei A, Henery ML, et al. 2011. A chemical perspective on the evolution of variation in Eucalyptus globulus. Perspectives in Plant Ecology , Evolution and Systematics 13: 305–318. [Google Scholar]

- Wang G, Tian L, Aziz N, et al. 2008. Terpene biosynthesis in glandular trichomes of hop. Plant Physiology 148: 1254–1266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiggins NL, McArthur C, McLean S, Boyle R. 2003. Effects of two plant secondary metabolites, cineole and gallic acid, on nightly feeding patterns of the common brushtail possum. Journal of Chemical Ecology 29: 1447–1464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiggins NL, McArthur C, Davies NW. 2006. Diet switching in a generalist mammalian folivore: fundamental to maximising intake. Oecologia 147: 650–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wildy DT, Pate JS, Bartle JR. 2000. Variations in composition and yield of leaf oils from alley-farmed oil mallees (Eucalyptus spp.) at a range of contrasting sites in the Western Australian wheatbelt. Forest Ecology and Management 134: 205–217. [Google Scholar]

- Williams JE, Brooker MIH. (eds) 1997. Eucalypts: an introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wiltshire RJE, Potts BM, Reid JB. 1998. Genetic control of reproductive and vegetative phase change in the Eucalyptus risdonii–E. tenuiramis complex. Australian Journal of Botany 46: 45–63. [Google Scholar]

- Xiao Y, Wang Q, Erb M, et al. 2012. Specific herbivore-induced volatiles defend plants and determine insect community composition in the field. Ecology Letters 15: 1130–1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang CQ, Wu XM, Ruan JX, et al. 2013. Isolation and characterization of terpene synthases in cotton (Gossypium hirsutum). Phytochemistry 96: 46–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao F, Shu L, Wang Q, Wang M, Tian X. 2011. Emissions of volatile organic compounds from heated needles and twigs of Pinus pumila. Journal of Forestry Research 22: 243–248. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.