Abstract

Maternal behavior is dependent on estrogen receptor-alpha (ERα; Esr1) and oxytocin receptor (OTR) signaling in the medial preoptic area (MPOA) of the hypothalamus, as well as dopamine signaling from the ventral tegmental area (VTA) to forebrain regions. Previous studies in rats indicate that low levels of maternal care, particularly licking/grooming (LG), lead to reduced levels of MPOA ERα and VTA dopamine neurons in female offspring and predict lower levels of postpartum maternal behavior by these offspring. The aim of the current study was to determine the functional impact on maternal behavior of neonatal manipulation of ERα in females that had experienced low vs. high levels of postnatal maternal LG. Adenovirus expressing ESR1 was targeted to the MPOA in female pups from low and high LG litters on postnatal day 2–3. Over-expression of ESR1 in low LG offspring elevated the level of ERα-immunoreactive cells in the MPOA and of tyrosine hydroxylase cells in the VTA to that observed in high LG females. Amongst juvenile female low LG offspring, ESR1 over-expression also decreased the latency to engage in maternal behavior toward donor pups. These results show that virally-mediated expression of ESR1 in the neonatal rat hypothalamus results in lasting changes in ESR1 expression through the juvenile period, and can “rescue” hormone receptor levels and behavior of offspring reared by low LG dams, potentially mediated by downstream alterations within reward circuitry. Thus, the transmission of maternal behavior from one generation to the next can be augmented by neonatal ERα in the MPOA.

Keywords: maternal care, estrogen receptor-alpha, medial preoptic area, ventral tegmental area, dopamine

INTRODUCTION

In humans, early life adversity (abuse, neglect, or disrupted parent-child attachment) predicts an earlier onset of sexual activity (Ellis et al., 1999) and impaired social/emotional development (Manly et al., 2001) whereas nurturing parent-child interactions reduce the incidence of psychiatric dysfunction (Korosi and Baram, 2009; Maselko et al., 2011). These developmental experiences have a lasting impact on brain function and gene expression profiles that have been attributed to epigenetic programming (Gudsnuk and Champagne, 2011). In rats, the impact of mother-infant interactions is no less profound, with low levels of maternal care predicting heightened stress reactivity, impaired cognition, and increased sexual receptivity in adult offspring (Meaney, 2001; Cameron et al., 2008). Low compared to high levels of maternal licking/grooming (LG) experienced in infancy is associated with decreased oxytocin receptor (OTR) and estrogen receptor-alpha (ERα) levels in the medial preoptic area (MPOA) of the hypothalamus in female offspring (Francis et al., 2000; Champagne et al., 2001; Champagne et al., 2003; Peña et al., 2013) and decreased tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) -immunoreactive dopamine neurons in the ventral tegmental area (VTA) (Peña et al., 2014). These neuroendocrine and reward system changes may account for the low levels of maternal care exhibited by offspring of low LG mothers (Francis et al., 1999; Champagne et al., 2003).

Analyses of the developing female hypothalamus indicate that ERα levels within the MPOA are decreased in offspring of low LG mothers by postnatal day 6 (P6) (Champagne et al., 2006; Peña et al., 2013). Among juvenile female offspring, reductions in ERα mRNA levels are evident at the time of weaning and may account for the reduced maternal responsivity observed in low LG females (Peña et al., 2013). We have hypothesized that reduced hypothalamic ERα leads to reduced estrogen sensitivity and OTR in the adult female brain with functional consequences for LG behavior (i.e. pharmacological OTR antagonism reduces LG) (Champagne et al., 2001). However, the functional role of developmental programming of hypothalamic ERα levels by maternal care in the maternal behavior of offspring had yet to be established.

Recently, we have also found reduced levels of dopamine neurons in the VTA at P6 in females reared by low LG dams (Peña et al., 2014). Maternal behavior, a motivated behavior, is dependent upon mesolimbic dopamine signaling and is inhibited by 6-OH-DA lesions in the VTA or nucleus accumbens (NAc) and after lesions severing tracts between the MPOA and VTA (Gaffori and Le Moal, 1979; Numan and Smith, 1984; Hansen et al., 1991). The mesolimbic dopamine system is hormonally sensitive and is a direct neuroanatomical target of estrogen-sensitive oxytocin neurons of the MPOA (Morrell et al., 1984; Shahrokh et al., 2010). Reduced dopamine neurons in the VTA in response to low LG that we have observed during development (Peña et al., 2014) may underlie lower levels of NAc dopamine release in adult dams prior to and during pup LG (Champagne et al., 2004), and therefore contribute to the behavioral perpetuation of maternal phenotype in the next generation. The early postnatal emergence of variation in both ERα and dopamine cell numbers suggests that these alterations develop independently in response to maternal care. However, dopamine neurons treated with estrogen increase neurite growth and TH mRNA in culture (Reisert et al., 1987; Beyer et al., 2003; Ivanova and Beyer, 2003), and transient levels of ERα have been found in the VTA from embryonic day 17 to P20 in rodents (Raab et al., 1995; Raab et al., 1999), indicating that the VTA may be particularly sensitive to estrogen or ERα during early postnatal development.

These previous findings raised two important questions: 1) Are elevated levels of neonatal ERα sufficient to drive maternal behavior? and 2) Does elevated hypothalamic ERα drive changes within the mesolimbic dopamine system? To determine the impact of developmental changes in hypothalamic ERα on subsequent maternal behavior and mesolimbic dopamine system development in the rat, we injected female offspring that had experienced low vs. high levels of maternal LG with an adenovirus expressing the ERα gene (Esr1). Direct targeting of the MPOA with this ERα over-expression vector during postnatal development led to sustained increases in ERα, increased VTA dopamine cell counts, and enhanced maternal behavior – abolishing differences in maternal responsivity predicted by the experience of low vs. high LG. This study suggests that ERα expression is a mechanism of transmission of maternal behavior across generations.

METHODS

Animals

Long Evans rats (Charles River Laboratories) were maintained on a 12 hour light-dark schedule (lights on at 0800h) with food and water provided ad libitum. Adult virgin females (n=40) were mated for one week and singly housed 1–2 days prior to parturition. At weaning (postnatal day 21 – P21) offspring were pair-housed by sex. All procedures were performed in accordance with NIH guidelines and with the approval of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at Columbia University.

Maternal behavior

Home cage maternal behavior was scored as previously described (Champagne et al., 2003). Maternal behavior (n=35 dams) was observed for five 60-minute observation periods daily during P1–6 (see Figure 1A for study design). Behavioral observations were made every 3 minutes during each observation period for a total of 600 observations per litter. Frequency of licking/grooming (LG) behavior was calculated as the number of observations of LG divided by the total number of observations. Low and high LG dams were defined as engaging in LG frequencies that were either one standard deviation below (low LG) or above (high LG) the mean LG of the cohort. Mid LG dams engaged in maternal LG frequencies within one standard deviation of the mean LG of the cohort.

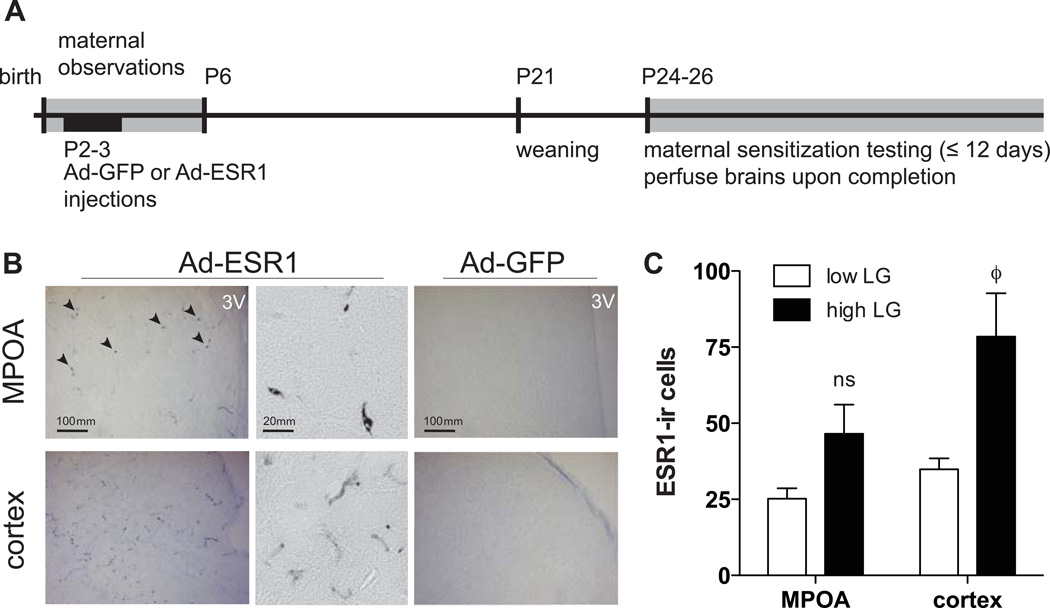

Figure 1. Study design and ESR1 over-expression.

(A) Timeline of maternal observations, virus injections, offspring maternal sensitization behavior testing, and brain collection. (B) ESR1-ir was detected in the MPOA and cortex of females that received neonatal injections of Ad-ESR1 (arrow heads), and not in animals that received Ad-GFP control injections. 3V, third ventricle. Higher magnification of Ad-ESR1 staining reveals primarily cell body staining within MPOA, with more tracts stained in cortical regions. (C) ESR1-ir cell counts in low and high LG offspring within the MPOA and cortex. ϕ, p<0.1 (low vs. high).

Adenovirus

Pre-packaged human type-5 adenoviruses containing human ESR1 (Ad-ESR1, SL100776; NM_000125) or GFP (Ad-GFP, SL100708) under the control of a constitutively active CMV promoter were purchased from SignaGen Laboratories. Both viruses lacked early phase genes E1 and E3 rendering them replication deficient, and had titers of 1×1010~1×1011 PFU/ml. Adenovirus was chosen over other virus types (e.g. HSV, AAV, lentivirus) due to the rapid onset of expression (~ 2 days) after introduction to a host and lasting in vivo expression (~ 9 months) (Hu et al., 2010; Rahim et al., 2011). Pilot testing confirmed that expression could be detected 6 weeks following injection into the neonatal brain.

Adenovirus injections

Neonatal female pups received stereotaxic injections of either Ad-GFP or Ad-ESR1 on P2–3 (see Figure 1A). Prior to injection, pups were cryoanesthetized on wet ice for 15 minutes, until nonresponsive to foot pinch. 10µl Hamilton syringes dedicated to either Ad-GFP or Ad-ESR1 were used to deliver 0.4µl microinjections of virus per animal. Bregma (visible through the skin at this age) was used to guide needle placement. Injections of Ad-GFP or Ad-ESR1 were aimed at the ventral 3rd ventricle to avoid bilateral placement errors that would be difficult to detect after several weeks of rapid growth. Pilot testing with Ad-GFP revealed staining within the MPOA and ventricle walls following injection. The needle was centered at Bregma and lowered to −5mm over the course of 30–40 seconds. Virus was infused via MicroSyringe Pump Controller (World Precision Instruments) at a rate of 4nl/second. After a rest period of 60 seconds, the needle was slowly removed and the pup was transferred to a warming pad to recover (up to 30 minutes). 100% of injected pups survived the procedure. Pups were returned to the home cage and remained un-manipulated, except for weekly cage changes, until weaning. Inclusion in the over-expression group was determined by presence of hESR1 immunostaining.

Juvenile maternal sensitization

Offspring were tested for maternal behavior as juveniles while adenovirus was known to be expressed, and prior to onset of puberty, using a maternal sensitization paradigm. Virgin maternal sensitization latency has previously been shown to correlate strongly with LG frequency observed after parturition (Champagne et al., 2001), and thus maternal sensitization among the juvenile virgin offspring in the current study is proposed as a proxy of subsequent maternal LG behavior. Maternal sensitization involves exposing test subjects to neonates daily until they display maternal behavior (Champagne et al., 2001). Animals were tested daily between 1500h and 1700h beginning on P24–26 (see Figure 1A). Each day, three recently fed, 2–5 day-old pups from a donor litter were placed in three quadrants in the cage (one pup per quadrant) away from the nest site. Test animals were observed for 1 hour for indices of maternal behavior. Donor pups were left in the cage for 23 hours. On test days 2–12, pups from the previous session were removed and replaced with a new set of recently fed pups, thereby commencing another 1-hour test session. Testing continued for 12 consecutive days or until a female displayed full maternal behavior (i.e. retrieved all three test pups, grouped them in the nest, and crouched over them) within the 1-hour test session.

Immunohistochemistry

Upon completion of maternal sensitization testing, animals were terminally anesthetized, transcardially perfused with PBS followed by 4% paraformaldehyde, and brains removed and post-fixed overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde at 4°C. Brains were then cryoprotected in 30% sucrose in PBS at 4°C until isotonic, and stored at −80°C. 35µm coronal sections were sliced and floated into PBS. Hypothalamic and ventral midbrain sections (10–16 per animal) were washed in PBS and blocked with normal serum before incubating in primary antisera at 4°C overnight. In one series of staining, all sections were dual-labeled using fluorescent markers for GFP and ERα (chicken-anti-GFP, 1:1000, Aves Labs; rabbit-anti-ERα, 1:3000, Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Sections were then washed and incubated in a secondary antisera at 4°C overnight (Alexa Fluor 488 goat-anti-chicken and Alexa Fluor 546 donkey-anti-rabbit, 1:1000, Life Technologies). Sections were washed, mounted on gelatin coated slides, and cover-slipped with ProLong Gold Antifade Reagent with DAPI (Life Technologies). In a second series of staining, sections were stained for human ESR1 protein (mouse-anti-hESR1, 1:3000, Life Technologies #49-1002). Signal was amplified with biotinylated goat-anti-mouse (Vectastain) followed by chromogen visualization (Vector SG, Vector Labs). After washing, sections were dehydrated in a series of ethanol washes, cleared with xylene, and coverslipped with DPX. For clarity, total estrogen receptor-alpha will be referred to as “ERα” while virally over-expressed human estrogen receptor-alpha will be referred to as “ESR1.” In a third series of staining, 8–11 slices per animal containing the ventral midbrain were immunofluorescently labeled for tyrosine hydroxylase (TH), an enzyme in the dopamine synthesis pathway and marker of dopamine neurons (primary antibody: rabbit-anti-TH, 1:10,000, Santa Cruz Biotechnology; secondary antibody: Cy2 conjugated donkey-anti-rabbit, 1:2000, Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

Imaging and cell count

Slides were imaged on an Olympus light microscope fitted with fluorescent filters. Anterior-posterior position of each section was noted. Cell counts (immunoreactive cells, -ir) were determined using MCID Core software (InterFocus Imaging Ltd, UK). An observer blind to condition outlined each region of interest for nuclei-specific analysis. Within the ventral midbrain, sub-nuclei of the VTA and substantia nigra (SN) were distinguished as previously reported (Peña et al., 2014) according to (Paxinos and Watson, 2005). Region area and density of immunoreactive cells were also recorded. Statistics were performed on an animal’s mean total cell count per region across slice sections.

Offspring group composition

Maternal LG data from the first two postnatal days were used to anticipate which litters would be low LG or high LG and pups from these initial litters were selected for injection. Up to four females per litter were injected: two with Ad-GFP and two with Ad- ESR1. Breeding generated a total of 35 litters and 20 of these litters were selected for injection as potential low or high LG. A total of 69 pups were injected with virus. Of the 20 litters, analysis of the full week of maternal observations revealed 5 litters to be low LG and 5 litters to be high LG. Two female offspring from 2 low LG litters that did not receive injections were included as low LG controls. No significant difference was found among non-injected and Ad-GFP injected low LG offspring on behavior or ERα-ir cells (p>0.8) and all pups were considered control. Final group sizes were further constrained based on the number of donor pups available for maternal sensitization testing. Resulting offspring group sizes were as follows: 12 low LG (7 control/Ad-GFP, 5 Ad-ESR1), 14 mid LG (6 Ad-GFP, 8 Ad-ESR1) and 18 high LG (7 Ad-GFP, 11 Ad-ESR1). Offspring of mid LG litters showed behavior and ERα cell counts that were intermediate between those of low and high LG litters. However, offspring from these litters began behavioral testing an average of two days after low and high LG offspring and this delay was found to have a significant effect on outcome measures in the analysis. Mid LG offspring were therefore only included in correlation analysis using dam LG frequency as a continuous variable. Offspring were categorized as control or Ad-ESR1 based on the presence of ESR1 staining in the brain, such that only animals that showed ESR1 staining in the brain at any level were included in the Ad-ESR1 group.

Statistics

All statistics were performed using SPSS (PASWS, IBM, version 18.0). Litters were not standardized for size or male/female ratio and these variables were used as covariates in analyses. Main effects and interactions were determined using ANOVA with independent and dependent variables and covariates as noted. Two-tailed student’s t-test was used for single-comparisons between high and low LG animals or between control and over-expression animals. Two-tailed Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated between ERα-ir and maternal behavior or TH-ir. All significance thresholds were set at p<0.05. Analyses were re-run using litter as a covariate to account for potential litter effects and all reported effects were confirmed even when controlling for this factor.

RESULTS

ESR1 over-expression

At the level of the MPOA, ESR1-ir was restricted to 2 mm on either side of the third ventricle, indicating that the virus was taken up by the tissue surrounding the injection site but that spread in the immediate vicinity was moderate and within previously reported range (Figure 1B; (Rahim et al., 2011). There was no significant difference in ESR1-ir cells counted in the MPOA among low and high LG female offspring (p=0.17; Figure 1B, C). ESR1 staining was also detected in the posterior regions of the hypothalamus, the lateral edge of the ventricles, and within the neocortex (Figure 1B). Cortical staining was likely due to adenovirus absorption by dividing cells of the ventricular zone followed by cortical migration. Cortical staining within images at the level of the hypothalamus (Bregma +.24 to −1.92, (Paxinos and Watson, 2005)) was observed in somatosensory and cingulate cortices and to a lesser degree in the piriform cortex. There was a trend in the average cortical ESR1-ir cells counted among low and high LG female offspring (p=0.06; Figure 1C). However, there was not a significant correlation between offspring behavioral measures and ESR1-ir count in the MPOA (p=0.97) or cortex (p=0.40).

ERα immunoreactivity in the MPOA

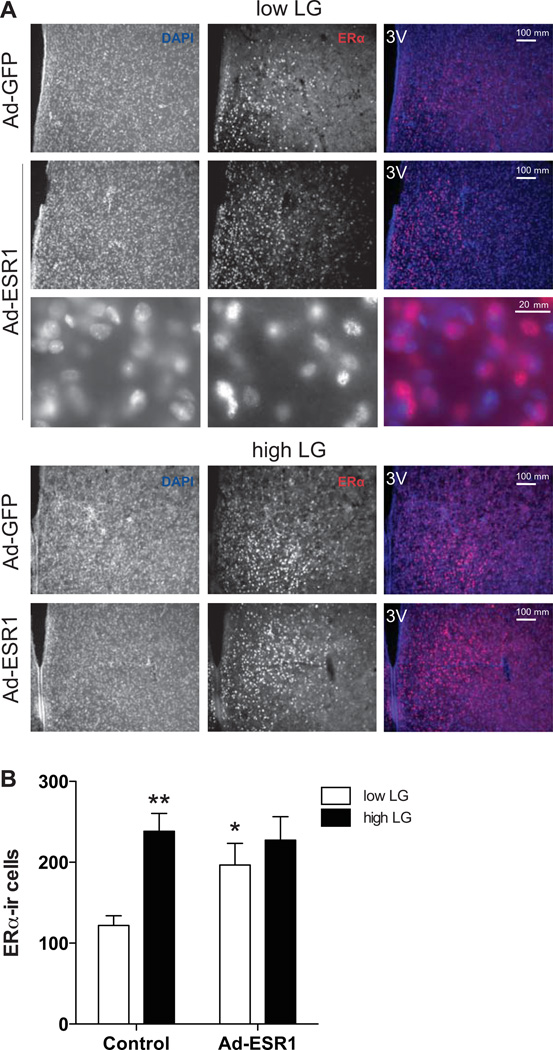

We found a main effect of maternal LG [F(1,29)=5.85, p<0.05)] and trend for an interaction between maternal LG and Ad-ESR1 injection [F(1,29)=3.02, p<0.1, Figure 2 A–B] on ERα levels in the MPOA. Among control females, there were elevated levels of ERα-ir in high compared to low LG females [t(1,12)=4.95, p<0.001]. No significant difference in ERα-ir was found between low and high LG ESR1-injected females (p>0.95). ESR1-injected low LG females had significantly elevated levels of ERα-ir compared to control low LG females [t(1,10)=3.15, p<0.01]. This effect was not observed in high LG females (p>0.37). Among control females, there was a significant correlation between maternal LG frequency experienced from PN1-6 and ERα-ir in the MPOA [analyses included mid LG offspring; R(14)=0.86, p<0.001]. This correlation was not significant in ESR1-injected females (p=0.63). These results indicate that high maternal LG or over-expression of ESR1 is sufficient to increase levels of ERα-ir in the MPOA of females, but that these effects are not additive.

Figure 2. ERα-ir cells in the MPOA of control and Ad-ESR1 low and high LG offspring.

(A) Representative images of total ERα-ir in the MPOA of control and Ad-ESR1 low and high LG offspring. 3V, third ventricle. Higher magnification confirms nuclear ERα-ir. (B) Mean ± SEM cells counted expressing ERα protein in the MPOA. *p<0.05 (compared to control) **p<0.01(low vs. high).

Maternal sensitization behavior

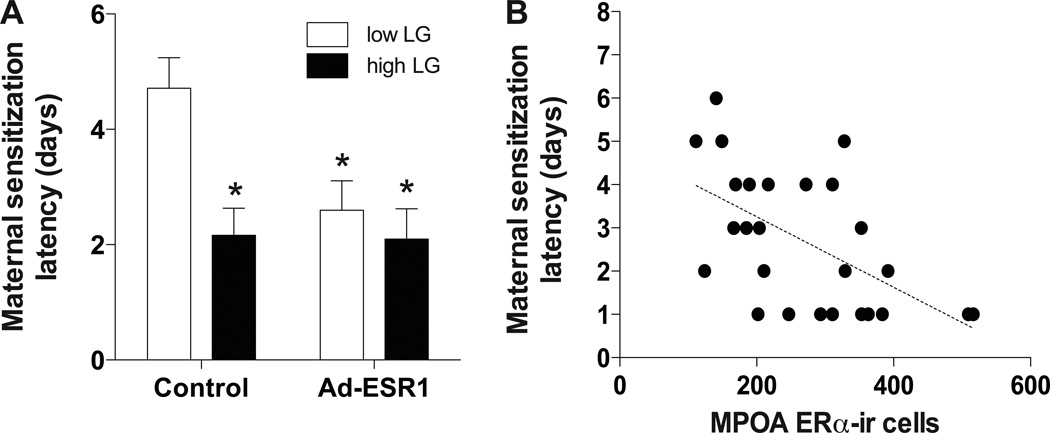

Consistent with our previous findings, female offspring that experienced high compared to low levels of postnatal LG were found to have significantly shorter latencies to maternal sensitization [t(1, 10)=2.77, p<0.05; Figure 3A] and thus enhanced maternal behavior. This group difference was abolished among females that received neonatal ESR1. Among low LG juvenile females, neonatal ESR1 significantly reduced latencies to maternal sensitization compared to controls [t(1, 10)=2.80, p<0.05; Figure 3A], a difference that was not detected among high LG females (p>0.78). The number of ERα-ir cells in the MPOA were significantly correlated with latency to maternal sensitization behavior [R(27)=0.45, p<0.05; Figure 3B]. These results indicate that high maternal LG or over-expression of ESR1 in the brain is sufficient to decrease maternal sensitization latency.

Figure 3. Maternal sensitization latencies of control and Ad-ESR1 low and high LG offspring.

(A) Mean ± SEM latency (days) of juvenile females to show full maternal behavior toward donor pups. *p<0.05 (comparison to low LG control offspring). (B) Correlation between ERα-ir cells in the MPOA with maternal sensitization latency among offspring.

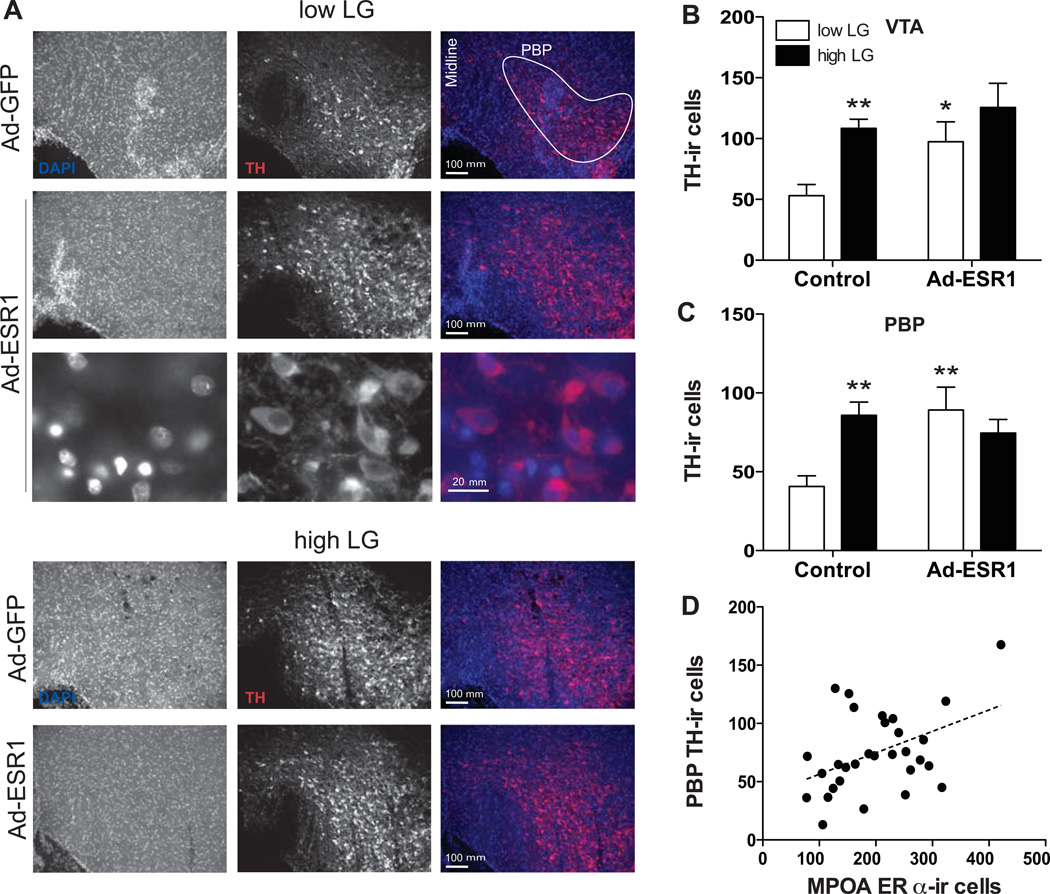

TH immunoreactivity in the ventral midbrain

TH-ir cells were counted within nuclei of the VTA and SN of control and Ad-ESR1 females (Figure 4A). Two-way ANOVA indicated a significant main effect of maternal LG [F(1,29)=4.90, p<0.05; Figure 4B] and of virus [F(1,29)=5.70, p<0.05] on TH-ir cells in the VTA as a whole. This was primarily driven by differences in the parabrachial pigmentosa nucleus of the VTA (PBP), as there were no significant effects observed for any other VTA nucleus. We found a significant interaction between maternal LG and virus [F(1,29)=6.00, p<0.05; Figure 4B] on TH-ir cells counted in the PBP. Further analysis indicated a significant difference between low and high LG control animals in TH-ir cells in the PBP [t(1, 12)=4.17, p<0.01] and entire VTA [t(1, 12)=4.68, p<0.01], such that a greater number of TH-ir cells were found among high LG females. Among low LG females, a greater number of TH-ir cells were found in the PBP of Ad-ESR1 compared to control animals [t(1, 10)=3.34, p<0.01]. These differences were not detected among High LG females (p>0.39). There was also a positive linear correlation between ERα-ir cells in the MPOA and TH-ir cells in the PBP [R(29)=0.44, p<0.05; Figure 4D]. Within the SN, we found elevated TH-ir in the SN-pars compacta dorsal tier (Paxinos and Watson, 2005) among high LG control females [t(1, 12)=2.64, p<0.05] and low LG females that received ad-ESR1 [t(1, 10)=2.38, p<0.05] compared to low LG control females. We did not find a significant effect of maternal care or virus for any other SN nucleus. Finally, the number of TH-ir cells in the PBP was correlated with latency to maternal sensitization behavior [R(29)=0.38, p<0.05]. Together, these findings suggest that there is an effect of maternal LG and of neonatal ERα on midbrain dopamine neurons.

Figure 4. TH-ir cells in the ventral midbrain of control and Ad-ESR1 low and high LG offspring.

(A) Representative images of total TH-ir in the VTA and SN (right hemisphere shown) of control and Ad-ESR1 low and high LG offspring. Higher magnification confirms cytoplasmic TH-ir. Mean ± SEM TH-ir cells counted in the (B) VTA as a whole and (C) PBP of the VTA. *p<0.05, **p<0.01 (comparison to low LG control offspring). (D) Correlation between TH-ir cells in the PBP with ERα-ir cells in the MPOA among offspring.

DISCUSSION

Our results provide the first demonstration that increased ERα in the MPOA during postnatal development is sufficient to facilitate maternal behavior. In previous studies, the experience of high compared to low levels of postnatal LG by females was found to predict higher levels of ERα-ir and mRNA in the MPOA, higher TH-ir in the VTA, shorter latencies to maternal sensitization, and increased frequencies of postpartum LG towards pups (Champagne et al., 2001; Champagne et al., 2003; Champagne et al., 2006; Peña et al., 2013; Peña et al., 2014). Suppression of ERα in the MPOA of adult mice has previously been found to inhibit maternal care, including pup retrieval (Ribeiro et al., 2012) and compliments findings indicating the critical role of the MPOA and estrogen sensitivity within this region for the expression of mother-infant interactions (Fahrbach and Pfaff, 1986; Ogawa et al., 1998). We have previously speculated that LG-associated changes in hormone receptor expression within the developing female hypothalamus are a critical mechanistic link between the experience of maternal care and changes to the maternal brain and behavior in later life, and the current findings provide direct evidence to support this conclusion. Neonatal up-regulation of ERα was capable of mimicking the effects of high levels of maternal LG and shift the neuroendocrine, mesolimbic dopamine, and behavioral development of offspring reared by a low LG mother. Similar to neonatal cross-fostering (Champagne et al., 2003; Champagne et al., 2006), this target-specific intervention was capable of attenuating group differences in behavior. Though LG-associated effects on neuroendocrine systems and subsequent behavior may vary as a function of sex (Kurian et al., 2010) and within-litter variation in LG (Cavigelli et al., 2010), our data are suggestive that LG-induced effects on maternal sensitization in females is significantly regulated by hypothalamic ERα during development.

The hypothalamic neuroendocrine system and the mesolimbic dopamine system are anatomically connected and implicated together in maternal behavior, and we provide evidence that these two systems may be linked at a molecular level by ERα expression during early postnatal development. Estrogen-sensitive oxytocin neurons project from the MPOA and paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus to the VTA, and infusion of oxytocin directly into the VTA induces dopamine release in the NAc (Morrell et al., 1984; Shahrokh et al., 2010). Treatment of ovariectomized females with estradiol increases firing probability in dopamine neurons of the VTA, providing strong physiological evidence for midbrain sensitivity to estrogen (Sakamoto et al., 1993). In both rats and mice, ovariectomy reduces TH-ir cells in the VTA and SN (Johnson et al., 2010). Treatment with estradiol or an ERα agonist normalizes the level of TH-ir cells in the VTA, while ERβ treatment only restores TH-ir cells in the SN of rats (Johnson et al., 2010), which is consistent with our finding that MPOA Ad-ESR1 treatment specifically enhanced VTA TH-ir cells. This hormonal sensitivity of the mesolimbic dopamine system is important for maternal behavior. For example, pups are only able to elicit dopamine release in the NAc of postpartum dams and hormonally primed females (Afonso et al., 2008; Afonso et al., 2009), and pharmacological activation of D1 receptors in the NAc enhances maternal sensitization and pup retrieval in pregnancy-terminated (hormonally primed) females (Stolzenberg et al., 2007). Furthermore, low LG dams have decreased oxytocin neurons projecting from the MPOA and paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus to the VTA (Shahrokh et al., 2010). Our findings of elevated VTA TH-ir among low LG offspring after Ad-ESR1 and of a correlation between ERα-ir and TH-ir suggests that VTA dopamine neuron development may be downstream of hypothalamic ERα expression. Elevated VTA dopamine neuron levels, naturally by LG or artificially via Ad-ESR1, likely contribute to the enhanced maternal behavior observed. However, further studies simultaneously reducing TH levels in the VTA would clarify whether sensitization of maternal behavior is dependent upon developmental effects induced by ERα within the VTA, or whether elevated MPOA ERα alone is sufficient to promote this behavior. In addition, while our findings imply that elevated MPOA ERα expression is sufficient to facilitate onset of maternal behavior, it has yet to be determined whether exclusively increasing the number of dopamine neurons in the VTA during development would have similar effects on this behavioral outcome.

The mechanism of maternal sensitization in pre-pubertal versus cycling, hormonally primed or postpartum females is important to consider. It has been proposed that virgin female rats are not initially maternal due to neophobia toward pups and that continuous pup exposure allows the female to overcome this aversion and show positive-approach responses (Fleming et al., 1999). Interestingly, local hormone receptor levels may still mediate this anxiolytic response. Elevated oxytocin levels are associated with decreased anxiety in addition to increased maternal behavior (Neumann et al., 2000). Thus, estrogen-regulated oxytocin levels may play a role in pup-induced decreases in anxiety (Champagne et al., 2001). Offspring reared by high LG dams have elevated levels of ERα and OTR in the MPOA as juveniles at P21, prior to puberty (Peña et al., 2013). While plasma hormone levels change significantly across juvenile and pubertal development, estradiol and testosterone measured within the hypothalamus are fairly constant from P20 through adulthood (Konkle and McCarthy, 2011), suggesting that the receptor level rather than brain hormone level may be most important for priming a behavioral response. Moreover, experience-dependent maternal behavior has been observed to be estrogen-independent (Stolzenberg and Rissman, 2011), and may involve complex interactions between hormone receptors and dopamine (Afonso et al., 2008). Dopamine has been shown to stimulate ERα (Smith et al., 1993; Olesen et al., 2005), thus providing one mechanism for activation of ERα independent of its traditional ligand estradiol. In cell culture, ERα has also been shown to stimulate TH and other dopaminergic factors (Sabban et al., 2010), so it is possible to have a feed-forward loop between these systems. Thus, prior to puberty and the onset of elevated gonadal hormones, dopamine may play a more significant role in maternal motivated behaviors.

A critical question that has been raised in the context of developmental studies is the mechanism through which the effects of early life experience on brain function and behavior are sustained over time. Steroid hormones are known to have organizational effects on brain development, inducing permanent morphological and molecular changes within a discrete developmental window. In rats, from E18 to P5 there is a critical period for estrogen to masculinize sexually dimorphic brain region morphology, including the MPOA (Rhees et al., 1990; Rhees et al., 1990). While it is a possibility that neonatal ESR1 over-expression induces organizational effects within sexually dimorphic or other downstream brain circuits such as the VTA, it is likely that the enhanced maternal behavior observed is due to the sustained up-regulation of ERα levels in the MPOA consequent to Ad-ESR1. Offspring that have experienced high levels of LG during infancy likewise have sustained elevations in ERα gene expression which is attributed to epigenetic modifications within the Esr1 promoter, including DNA hypomethylation, posttranslational modifications (trimethylation of H3K4 and H3K9), and increased STAT5b (signal transducer and activator of transcription) binding (Champagne et al., 2006; Peña et al., 2013). Importantly, both Ad-ESR1 and high LG achieve their long-term effects through elevations in MPOA ERα, though MPOA-induced effects on downstream targets, such as the mesolimbic dopamine circuit, are a critical feature of the maternal brain and are also thought to induce variations in maternal behavior (Shahrokh et al., 2010). Moreover, the correlation between ERα and maternal responsivity in the pre-pubertal female suggests the possibility of non-ligand dependent activation of ERα, possibly through dopamine-ERα interactions (Olesen et al., 2005).

Regional specificity of ERα-mediated effects on reproductive behavior is an important consideration within the current study, particularly in light of reproductive trade-offs apparent in association with the experience of high vs. low levels of maternal care. Though elevated levels of maternal LG induce increased ERα and estrogen sensitivity in the MPOA, low levels of LG have similar effects within other hypothalamic regions, such as the anteroventral paraventricular nucleus, leading to increased hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal activity, an earlier onset of puberty, and heightened sexual receptivity (Cameron et al., 2008). The targeting of ERα via Ad-ESR1 induced over-expression could provide a valuable tool for determining the region-specific role of ERα in maternal vs. sexual behavior and the limited spread of adenovirus from the site of injection argues for the feasibility of this approach. The cortical expression of Ad-ESR1 is consistent with previous reports of P1 Ad5-GFP injections (Rahim et al., 2011) and with the timing of cortical migration of neurons from the subventriclar zone in the developing brain (Doetsch and Alvarez-Buylla, 1996). Though we have previously found sex-specific effects of maternal care on ERα expression in the prefrontal cortex of juvenile mice (increased in females, decreased in males) (Kundakovic et al., 2013), cortical ERα expression is reduced significantly by the second postnatal week (Prewitt and Wilson, 2007) and we have not observed differences in ERα between the offspring of low vs. high LG mothers within the cortex. Moreover, the role of the cortex in maternal behavior is attributed to the processing of olfactory responses and recognition of offspring rather than pup retrieval and other active maternal responses (Koch and Ehret, 1991; Calamandrei and Keverne, 1994; Ehret and Buckenmaier, 1994).

The transmission of parental behavior across generations has significant implications for the neurobiological and behavioral development of offspring and grand-offspring. In humans, the experience of neglect, maltreatment, or abuse during childhood predicts the occurrence of these behaviors toward the next generation (Pears and Capaldi, 2001; Berlin et al., 2011) and with increased risk of psychiatric dysfunction (Manly et al., 2001). Within the normal range of parenting behavior, infant attachment is predicted by the attachment scores, sensitivity, and intrusiveness of mothers and grandmothers (Benoit and Parker, 1994; Kretchmar and Jacobvitz, 2002). Rhesus macaques deprived of maternal contact display abusive and neglectful maternal behaviors towards offspring (Arling and Harlow, 1967). Abusive or protective parenting among macaques has been found to be consistent across generations, and cross-fostering studies indicate that it is the experience of abusive caregiving rather than genetic or in utero factors which mediate this matrilineal transmission (Maestripieri et al., 2007). Rodent studies have permitted the analyses of the cellular and molecular mechanisms involved in the transmission of maternal behavior and have illustrated the epigenetic impact on the maternal brain of neonatal abuse (Roth et al., 2009) and variations in maternal LG (Champagne et al., 2006). Though future studies will need to confirm the postpartum phenotype of females with induced hypothalamic ERα via Ad-ESR1, and the maternal behavior of their offspring, the current study contributes significantly to our understanding of the inheritance of variation in parental behavior by suggesting the role of maternally-induced transcriptional activity within the brain of offspring rather than DNA sequences in the germline in perpetuating maternal phenotypes from one generation to the next.

Acknowledgements

Grant DP2OD001674-01 from the Office of the Director NIH (FAC)

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

REFERENCES

- Afonso VM, Grella SL, Chatterjee D, Fleming AS. Previous maternal experience affects accumbal dopaminergic responses to pup-stimuli. Brain Res. 2008;1198:115–123. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.12.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Afonso VM, King S, Chatterjee D, Fleming AS. Hormones that increase maternal responsiveness affect accumbal dopaminergic responses to pup- and food-stimuli in the female rat. Horm Behav. 2009;56:11–23. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2009.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arling GL, Harlow HF. Effects of social deprivation on maternal behavior of rhesus monkeys. J Comp Physiol Psychol. 1967;64:371–377. doi: 10.1037/h0025221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benoit D, Parker KC. Stability and transmission of attachment across three generations. Child Dev. 1994;65:1444–1456. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1994.tb00828.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berlin LJ, Appleyard K, Dodge KA. Intergenerational continuity in child maltreatment: Mediating mechanisms and implications for prevention. Child Dev. 2011;82:162–176. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01547.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyer C, Pawlak J, Brito V, Karolczak M, Ivanova T, Kuppers E. Regulation of gene expression in the developing midbrain by estrogen: implication of classical and nonclassical steroid signaling. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003;1007:17–28. doi: 10.1196/annals.1286.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calamandrei G, Keverne EB. Differential expression of Fos protein in the brain of female mice dependent on pup sensory cues and maternal experience. Behav Neurosci. 1994;108:113–120. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.108.1.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron N, Del Corpo A, Diorio J, McAllister K, Sharma S, Meaney MJ. Maternal programming of sexual behavior and hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal function in the female rat. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2210. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cameron NM, Shahrokh D, Del Corpo A, Dhir SK, Szyf M, Champagne FA, Meaney MJ. Epigenetic programming of phenotypic variations in reproductive strategies in the rat through maternal care. J Neuroendocrinol. 2008;20:795–801. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2008.01725.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavigelli SA, Ragan CM, Barrett CE, Michael KC. Within-litter variance in rat maternal behaviour. Behav Processes. 2010;84:696–704. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2010.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champagne F, Diorio J, Sharma S, Meaney MJ. Naturally occurring variations in maternal behavior in the rat are associated with differences in estrogen-inducible central oxytocin receptors. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:12736–12741. doi: 10.1073/pnas.221224598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champagne FA, Chretien P, Stevenson CW, Zhang TY, Gratton A, Meaney MJ. Variations in nucleus accumbens dopamine associated with individual differences in maternal behavior in the rat. J Neurosci. 2004;24:4113–4123. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5322-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champagne FA, Francis DD, Mar A, Meaney MJ. Variations in maternal care in the rat as a mediating influence for the effects of environment on development. Physiol Behav. 2003;79:359–371. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(03)00149-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champagne FA, Weaver ICG, Diorio J, Dymov S, Szyf M, Meaney MJ. Maternal care associated with methylation of the estrogen receptor-alpha1b promoter and estrogen receptor-alpha expression in the medial preoptic area of female offspring. Endocrinology. 2006;147:2909–2915. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Champagne FA, Weaver ICG, Diorio J, Sharma S, Meaney MJ. Natural variations in maternal care are associated with estrogen receptor alpha expression and estrogen sensitivity in the medial preoptic area. Endocrinology. 2003;144:4720–4724. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-0564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doetsch F, Alvarez-Buylla A. Network of tangential pathways for neuronal migration in adult mammalian brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:14895–14900. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.25.14895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehret G, Buckenmaier J. Estrogen-receptor occurrence in the female mouse brain: effects of maternal experience, ovariectomy, estrogen and anosmia. J Physiol Paris. 1994;88:315–329. doi: 10.1016/0928-4257(94)90012-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis BJ, McFadyen-Ketchum S, Dodge KA, Pettit GS, Bates JE. Quality of early family relationships and individual differences in the timing of pubertal maturation in girls: a longitudinal test of an evolutionary model. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1999;77:387–401. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.77.2.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahrbach SE, Pfaff DW. Effect of preoptic region implants of dilute estradiol on the maternal behavior of ovariectomized, nulliparous rats. Horm Behav. 1986;20:354–363. doi: 10.1016/0018-506x(86)90043-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleming AS, O'Day DH, Kraemer GW. Neurobiology of mother-infant interactions: experience and central nervous system plasticity across development and generations. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1999;23:673–685. doi: 10.1016/s0149-7634(99)00011-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis D, Diorio J, Liu D, Meaney M. Nongenomic transmission across generations of maternal behavior and stress responses in the rat. Science. 1999;286:1155–1158. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5442.1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis DD, Champagne FC, Meaney MJ. Variations in maternal behaviour are associated with differences in oxytocin receptor levels in the rat. J Neuroendocrinol. 2000;12:1145–1148. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.2000.00599.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaffori O, Le Moal M. Disruption of maternal behavior and appearance of cannibalism after ventral mesencephalic tegmentum lesions. Physiol Behav. 1979;23:317–323. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(79)90373-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gudsnuk KM, Champagne FA. Epigenetic effects of early developmental experiences. Clin Perinatol. 2011;38:703–717. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2011.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen S, Harthon C, Wallin E, Löfberg L, Svensson K. Mesotelencephalic dopamine system and reproductive behavior in the female rat: effects of ventral tegmental 6-hydroxydopamine lesions on maternal and sexual responsiveness. Behav Neurosci. 1991;105:588–598. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.105.4.588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Z, Zhang Z, Guise T, Seth P. Systemic delivery of an oncolytic adenovirus expressing soluble transforming growth factor-beta receptor II-Fc fusion protein can inhibit breast cancer bone metastasis in a mouse model. Hum Gene Ther. 2010;21:1623–1629. doi: 10.1089/hum.2010.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ivanova T, Beyer C. Estrogen regulates tyrosine hydroxylase expression in the neonate mouse midbrain. J Neurobiol. 2003;54:638–647. doi: 10.1002/neu.10193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson ML, Ho CC, Day AE, Walker QD, Francis R, Kuhn CM. Oestrogen receptors enhance dopamine neurone survival in rat midbrain. J Neuroendocrinol. 2010;22:226–237. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2010.01964.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch M, Ehret G. Parental behavior in the mouse: effects of lesions in the entorhinal/piriform cortex. Behav Brain Res. 1991;42:99–105. doi: 10.1016/s0166-4328(05)80044-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konkle AT, McCarthy MM. Developmental time course of estradiol, testosterone, and dihydrotestosterone levels in discrete regions of male and female rat brain. Endocrinology. 2011;152:223–235. doi: 10.1210/en.2010-0607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korosi A, Baram TZ. The pathways from mother's love to baby's future. Front Behav Neurosci. 2009;3:27. doi: 10.3389/neuro.08.027.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kretchmar MD, Jacobvitz DB. Observing mother-child relationships across generations: boundary patterns, attachment, and the transmission of caregiving. Fam Process. 2002;41:351–374. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.2002.41306.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kundakovic M, Gudsnuk K, Franks B, Madrid J, Miller RL, Perera FP, Champagne FA. Sex-specific epigenetic disruption and behavioral changes following low-dose in utero bisphenol A exposure. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:9956–9961. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1214056110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurian JR, Olesen KM, Auger AP. Sex differences in epigenetic regulation of the estrogen receptor-alpha promoter within the developing preoptic area. Endocrinology. 2010;151:2297–2305. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-0649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maestripieri D, Lindell SG, Higley JD. Intergenerational transmission of maternal behavior in rhesus macaques and its underlying mechanisms. Dev Psychobiol. 2007;49:165–171. doi: 10.1002/dev.20200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manly JT, Kim JE, Rogosch FA, Cicchetti D. Dimensions of child maltreatment and children's adjustment: contributions of developmental timing and subtype. Dev Psychopathol. 2001;13:759–782. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maselko J, Kubzansky L, Lipsitt L, Buka SL. Mother's affection at 8 months predicts emotional distress in adulthood. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2011;65:621–625. doi: 10.1136/jech.2009.097873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meaney MJ. Maternal care, gene expression, and the transmission of individual differences in stress reactivity across generations. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2001;24:1161–1192. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.24.1.1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrell JI, Schwanzel-Fukuda M, Fahrbach SE, Pfaff DW. Axonal projections and peptide content of steroid hormone concentrating neurons. Peptides. 1984;5(Suppl 1):227–239. doi: 10.1016/0196-9781(84)90281-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann ID, Wigger A, Torner L, Holsboer F, Landgraf R. Brain oxytocin inhibits basal and stress-induced activity of the hypothalamo-pituitary-adrenal axis in male and female rats: partial action within the paraventricular nucleus. J Neuroendocrinol. 2000;12:235–243. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2826.2000.00442.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Numan M, Smith HG. Maternal behavior in rats: evidence for the involvement of preoptic projections to the ventral tegmental area. Behav Neurosci. 1984;98:712–727. doi: 10.1037//0735-7044.98.4.712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa S, Eng V, Taylor J, Lubahn DB, Korach KS, Pfaff DW. Roles of estrogen receptor-alpha gene expression in reproduction-related behaviors in female mice. Endocrinology. 1998;139:5070–5081. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.12.6357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olesen KM, Jessen HM, Auger CJ, Auger AP. Dopaminergic activation of estrogen receptors in neonatal brain alters progestin receptor expression and juvenile social play behavior. Endocrinology. 2005;146:3705–3712. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paxinos G, Watson C. The Rat Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Pears KC, Capaldi DM. Intergenerational transmission of abuse: A two-generational prospective study of an at-risk sample. Child Abuse Negl. 2001;25:1439–1461. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(01)00286-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peña CJ, Neugut YD, Calarco CA, Champagne FA. Effects of maternal care on the development of midbrain dopamine pathways and reward-directed behavior in female offspring. Eur J Neurosci. 2014 doi: 10.1111/ejn.12479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peña CJ, Neugut YD, Champagne FA. Developmental timing of the effects of maternal care on gene expression and epigenetic regulation of hormone receptor levels in female rats. Endocrinology. 2013;154:4340–4351. doi: 10.1210/en.2013-1595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prewitt AK, Wilson ME. Changes in estrogen receptor-alpha mRNA in the mouse cortex during development. Brain Res. 2007;1134:62–69. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.11.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raab H, Beyer C, Wozniak A, Hutchison JB, Pilgrim C, Reisert I. Ontogeny of aromatase messenger ribonucleic acid and aromatase activity in the rat midbrain. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1995;34:333–336. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(95)00196-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raab H, Karolczak M, Reisert I, Beyer C. Ontogenetic expression and splicing of estrogen receptor-alpha and beta mRNA in the rat midbrain. Neurosci Lett. 1999;275:21–24. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(99)00723-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahim AA, Wong AM, Ahmadi S, Hoefer K, Buckley SMK, Hughes DA, Nathwani AN, Baker AH, Mcvey JH, Cooper JD, Waddington SN. In utero administration of Ad5 and AAV pseudotypes to the fetal brain leads to efficient, widespread and long-term gene expression. Gene Ther. 2011;19:936–946. doi: 10.1038/gt.2011.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisert I, Han V, Lieth E, Toran-Allerand D, Pilgrim C, Lauder J. Sex steroids promote neurite growth in mesencephalic tyrosine hydroxylase immunoreactive neurons in vitro. Int J Dev Neurosci. 1987;5:91–98. doi: 10.1016/0736-5748(87)90054-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhees RW, Shryne JE, Gorski RA. Onset of the hormone-sensitive perinatal period for sexual differentiation of the sexually dimorphic nucleus of the preoptic area in female rats. J Neurobiol. 1990;21:781–786. doi: 10.1002/neu.480210511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rhees RW, Shryne JE, Gorski RA. Termination of the hormone-sensitive period for differentiation of the sexually dimorphic nucleus of the preoptic area in male and female rats. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1990;52:17–23. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(90)90217-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro AC, Musatov S, Shteyler A, Simanduyev S, Arrieta-Cruz I, Ogawa S, Pfaff DW. siRNA silencing of estrogen receptor expression specifically in medial preoptic area neurons abolishes maternal care in female mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:16324–16329. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1214094109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth TL, Lubin FD, Funk AJ, Sweatt JD. Lasting epigenetic influence of early-life adversity on the BDNF gene. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65:760–769. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.11.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabban EL, Maharjan S, Nostramo R, Serova LI. Divergent effects of estradiol on gene expression of catecholamine biosynthetic enzymes. Physiol Behav. 2010;99:163–168. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2009.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakamoto Y, Suga S, Sakuma Y. Estrogen-sensitive neurons in the female rat ventral tegmental area: a dual route for the hormone action. J Neurophysiol. 1993;70:1469–1475. doi: 10.1152/jn.1993.70.4.1469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shahrokh DK, Zhang TY, Diorio J, Gratton A, Meaney MJ. Oxytocin-dopamine interactions mediate variations in maternal behavior in the rat. Endocrinology. 2010;151:2276–2286. doi: 10.1210/en.2009-1271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith CL, Conneely OM, O'Malley BW. Modulation of the ligand-independent activation of the human estrogen receptor by hormone and antihormone. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:6120–6124. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.13.6120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stolzenberg DS, McKenna JB, Keough S, Hancock R, Numan MJ, Numan M. Dopamine D1 receptor stimulation of the nucleus accumbens or the medial preoptic area promotes the onset of maternal behavior in pregnancy-terminated rats. Behav Neurosci. 2007;121:907–919. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.121.5.907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stolzenberg DS, Rissman EF. Oestrogen-independent, experience-induced maternal behaviour in female mice. J Neuroendocrinol. 2011;23:345–354. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2826.2011.02112.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]