Abstract

Background

Prophylaxis with hepatitis B immunoglobulin (HBIG) and nucleoside analogs can prevent hepatitis B virus (HBV) recurrence after liver transplant (LT).

Aim

To determine the efficacy and cost of maintaining immunoprophylaxis with HBIG and hyperimmune plasma (HIP) for 6 months after LT.

Material & methods

The study included 22 HBV related LT recipients who were on entecavir and either HBIG or HIP for 6 months. Post transplant HBIG or HIP dose and cost incurred towards prophylaxis were noted. The cost of 200 IU of HBIG at the time of study was Rs 8250/- (US Dollars 135) and that of 2000 IU of HIP was Rs 8000/- (USD 130.7). The loading and maintenance costs at end of 6 months were compared between the two groups. Response to HBIG and HIP was assessed by checking for HBsAg reactivity, anti HBs titer response and HBV DNA viral load.

Statistical analysis

Median and range, Kruskal Wallis (KW) sign rank Sum Test and Correlation Coefficient (r2) was used for analysis.

Results

Thirteen recipients received HBIG and 9 recipients HIP. The anti HBs response to HIP was significantly high compared to HBIG (KW Sign rank Sum test P < 0.05); titers remained high until the study period. Between 8 and 30 days, the titer achieved by both HBIG and HIP was similar (KW Sign rank Sum test not significant). Despite low anti HBs titer of <100 IU/L, none of the recipients on HBIG had HBsAg reactivity while 3 on HIP had transient HBsAg positivity. The total cost with HBIG was 13.9 times the cost of HIP.

Conclusion

HIP immunoprophylaxis in combination with entecavir achieves a high anti HBs titer at a significant low cost during anhepatic and loading phase. HBV reactivation rates with HBIG and HIP is low despite low anti HBs titer.

Keywords: Hepatitis B virus, hepatitis B immunoglobulin, hyper-immune plasma, liver transplantation, HBV recurrence

Abbreviations: anti HBs Ab, anti hepatitis B virus antibody; ESLD, end-stage liver disease; HBIG, hepatitis B immunoglobulin; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HBsAg, hepatitis B surface antigen; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; HCV, hepatitis C virus; HIP, hyper-immune plasma; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; KW, Kruskal Wallis; LT, liver transplantation; USD, US Dollars; NA, nucleos(t)ide analogs

HBV related liver disease is a common indication for liver transplantation (LT) in South Asian countries. Immunoprophylaxis with Hepatitis B immune globulins (HBIG) in combination with nucleos(t)ide analogs (NA), is highly effective in preventing HBV recurrence post LT. On long term follow up, the recurrence rates are low and ranges from 0 to 10%.1–3 The dose of HBIG for immunoprophylaxis is adjusted to maintain an anti HBs antibody titer (anti HBsAb) of more than 100 IU/L. Long term maintenance with HBIG results in an extra monetary burden to the recipient resulting in poor recipient compliance. The cost of 1 mL of 200 IU of HBIG is Rs 8250/- (USD 135).

Worldwide, several strategies have been adopted to circumvent this cost factor and enhance patient compliance. These include, limiting HBIG treatment to 18–24 months after LT and subsequently maintaining with life-long NA therapy either as mono - or combination of two NA,4–7 or alternatively, using low-dose intramuscular HBIG in combination with NA.8–10 A third option alternative has been the use of higher doses of HBIG11–13 in combination with NA in recipients with high pre-transplant HBV DNA levels.14

As to when HBIG can be stopped after LT is not clear and currently centers continue to use HBIG as maintenance therapy.15 An alternative to commercial HBIG, is the use of hyperimmune plasma (HIP) i.e. fresh frozen plasma with high anti HBs titer. This modality of prophylaxis has considerably reduced the cost of immunoprophylaxis.16

The aim of the study was to determine the efficacy of HBIG and HIP in reactivation of HBV infection in LT recipients and to determine the cost benefits between the two regimens.

Methodology

The study is retrospective. All HBV LT recipients operated between August 2009 and January 2013, and on HBIG or HIP prophylaxis for at least 6 months were included in the study. The baseline demographic information such as age, gender, pretransplant HBV DNA viral load, and details of anti virals were noted. Post transplant details of immunoprophylaxis included dose of HBIG or HIP and mode of administration (intravenous or intramuscular). Response to prophylaxis was assessed by Hepatitis B surface Antigen (HBsAg) reactivity, and anti HBs response. HBV DNA viral load was not estimated routinely as this was adding to the cost of the treatment.

The dose of HBIG or HIP given during anhepatic, loading (between one to 7 days), and maintenance phase (i.e. 8–30 days, 31–90 days and 91–180 days) were noted. These were correlated with anti HBs titer on Day 0, Day 7, Day 30, 90 and 180 days. HBsAg reactivity was also noted.

The cost incurred per patient towards immunoprophylaxis on Day 7 and at end of 6 months was calculated and compared. The cost of 200 IU of HBIG was Rs 8250/- (USD 135) and for 2000 IU of HIP this was Rs 8000/- (USD 130.9) (1 USD = Rs 61.2/-).

Recipients were contacted either by mail or direct telephonic conversation until 6 months of follow up for HBsAg status and anti HBs titer. Additional dose of HBIG or HIP was given if the recipient was either HBsAg positive or the anti HBs levels were less than 100 I/L.

Preparation of Hyperimmune Plasma and Administration of HIP

HIP was introduced in January 2012. Voluntary as well as donors related to the recipient who were previously vaccinated for HBV infection were screened for anti HBs levels using enhanced chemiluminescent immunoassay {VITROS ECiQ Immunodiagnostic System (Ortho Clinical Diagnostics), Rochester, NY}. Plasma was collected from donors whose anti HBs titers exceeded 5000 IU/L. All donors fulfilled the donation criteria of Drug and Cosmetic Act (DCA) guidelines.17 All the samples were screened for Hepatitis B and C virus (HBV and HCV), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), syphilis and malarial infection. Nucleic Acid Amplification testing was done for HBV, HCV, and HIV.

After plasmapheresis (using Trima cell separator: Terumo BCT, USA), approximately 400–500 mL leukocyte reduced plasma was collected as per the guidelines. Each unit was divided into aliquots based on donor's anti HBs titer so as to provide 2000 IU in a single dose. These aliquots were stored at −80 °C for a maximum period of one year. The anti HBs level was noted on two occasions: one at the time of donation and second at the time of transfusion.

There were 12 HIP donors for 9 recipients, 10 of whom maintained high anti HBs levels (>20,000 IU/L) for a mean period of 12 months. Two donors with declining anti HBs titer were given a booster dose of HBV vaccination.

HIP Administration

Hyperimmune plasma containing at least 2000 IU/L of anti-HBs was given intravenously within 15–20 min after thawing during the anhepatic phase, and the same dose was repeated for next 7 days. During the maintenance period i.e. until 6 months, HIP was given when anti HBs titer was below 100 IU/L, which was monitored at monthly intervals. Vital parameters like pulse, blood pressure, and body temperature were monitored during transfusion. Non—responders to HIP were considered as “HIP failure” and were reverted to HBIG.

Exclusion Criteria

Recipients with a high pre-transplant viral HBV DNA load i.e. > 2000 IU/mL, co-infection with more than one hepatotropic virus infection, combined liver and kidney transplantation and not reporting for follow up within a month of surgery were excluded.

Ethics committee of the Institution approved the study.

Statistical Analysis

For HBIG and HIP, the median dose, the range and anti HBs titer response was computed for the anhepatic phase, Day 0 to Day 7, and Day 8 to Day 180. Kruskal Wallis (KW) sign rank Sum Test compared the median when the sample size had more than five values in each group. Correlation coefficient was calculated for the dose given and the anti HBs titer response for the respective periods. The cost of HBIG and HIP was calculated (in Rupees and USD) for the loading and maintenance dose.

Results

Twenty six patients with HBV related end stage liver disease (ESLD) had liver transplantation (Deceased donor: 10; Living donor 16). Four recipients on entecavir only were excluded from the analysis.

Of the remaining 22 recipients, 17 were on entecavir, 3 on tenofovir, one each on adefovir and lamivudine respectively prior to transplant. Two patients in addition received PEG interferon. HBV DNA levels were undetectable in all except one patient whose level was 1800 IU/mL. Post transplant, 13 recipients received HBIG and 9 HIP.. Due to cost constraint one recipient on HBIG was switched over to HIP on day 8 after transplant.

The median age, gender distribution, the type of HBV related liver disease and pretransplant antiviral treatment in the two groups is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Recipients on HBIG and HIP.

| Characteristic | HBIG (13) | HIP (9) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESLD + HCC | ESLD | ESLD + HCC | ESLD | |

| DDLT (Nos) | 1a | 5 | 1 | 1 |

| LDLT (Nos) | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 |

| Median age (yrs) | 53.5 (46–71) | 52 (45–67) | 46 (41–54) | 48.5 (46–59) |

| Male:female ratio | 4 men | 4:1 | 5 men | 4 men |

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) in absence of End Stage Liver Disease (ESLD).

Anti HBs Response to HBIG and HIP

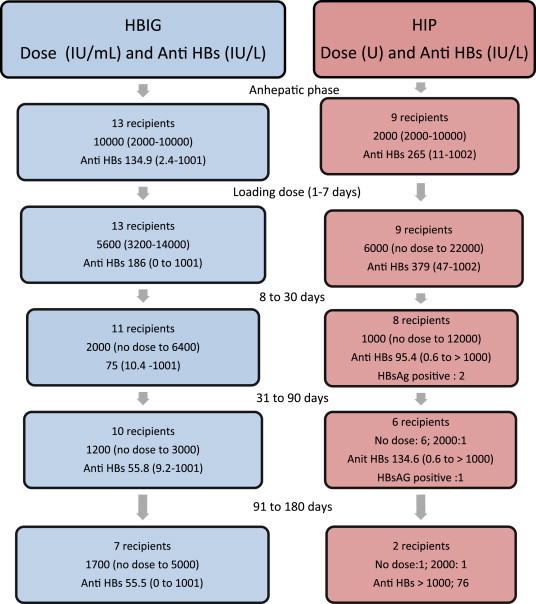

Figure 1 shows the anti HBs titer and HBsAg status in response to HBIG and HIP. There was a greater response to HIP than to HBIG during the various time period (P < 0.05) except between 8 and 30 days, when the titer achieved by both HBIG and HIP were similar (KW Sign rank Sum test not significant).

Figure 1.

HBsAg reactivity and anti HBs response to median dose of HBIG and HIP.

Correlation coefficient (r2) for the total dose of HBIG given during the time intervals 1–7 days, 8–30 days, 31–90 days and 91–180 days with the corresponding anti HBs titer was high at 19.2% at the end of first week indicating that a 19.2% increase in anti HBs titer was due to high dose of HBIG. The correlation was highest at 39.1% at the end of 90 days with a negative impact i.e. 39.1%. For HIP, the highest correlation coefficient was 75% at the end of 180 days. The r2 for all other intervals was positive but less than 5%. However none of the r2 values were significant (due to small sample size).

Figure 1 shows the HBIG and HIP dose, HBsAg reactivity and anti HBs response during the study period.

Dose Dependent Benefits with HBIG Immunoprophylaxis

Nine recipients received an anhepatic dose of 10,000 IU and 4 received 2000 IU. The loading dose ranged from 4800 IU to 12,500 IU. The wide variations in the dose was largely intended to achieve an anti HBs titer of 100 IU/L.

There were 3 dropouts. One recipient who received HBIG for the anhepatic and loading phase was switched over to HIP on 8th day as matched HIP donor was not available for the anhepatic and loading phase. The second recipient was switched over to HIP in the 5th month due to cost constraint and the third expired 52 days after transplant due to sepsis.

The mean anti HBs titer during loading and maintenance phase was 160.5 IU/L and 62.1 IU/L respectively. All samples were negative for HBsAg, despite low anti HBs titer. HBV DNA in 3 recipients was <20 IU/mL in 2 and 1080 IU/mL in the third case at 4th month of follow up.

HIP Immunoprophylaxis

The anhepatic dose varied from 10,000 IU to 2000 IU (Figure 1). The loading dose ranged from no dose to 11 doses with a median of 3 doses. The mean anti HBs titer was 322 IU/L, a value significantly higher than attained by HBIG. For the maintenance phase, 4 recipients did not require any further dose until end of 6 months; these patients were maintained on entecavir. Four other recipients received additional doses of HIP. One recipient was switched over from HBIG to HIP on the 8th day; he required just one dose of 2000 IU of HIP and was further maintained on entecavir. The overall mean anti HBs titer for the maintenance phase was 102 IU/L. Three recipients were transiently positive for HBsAg when the anti HBs titer was 11 IU/L, 1.3 IU/L and 70.6 IU/L respectively. HBV DNA in one of the 3 recipients was <20 IU/mL. Data was not available for the remaining 2.

Cost Benefit of HIP versus HBIG

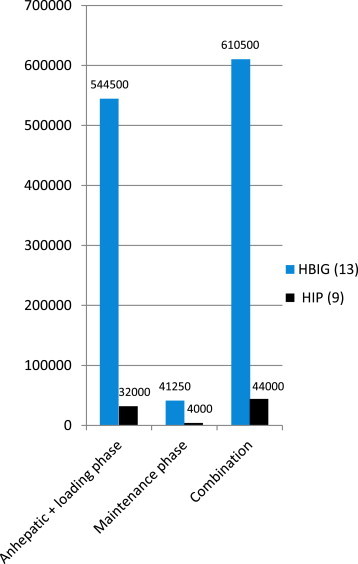

Figure 2 and Table 2 shows the median cost of HBIG and HIP for the anhepatic plus loading and maintenance dose in Indian currency. The median total cost at end of 6 months with HBIG was Rs. 610,500/- (USD 9975.5) and for HIP this was Rs. 44,000 (USD 719). The overall median cost of HBIG was 13.9 times that of HIP.

Figure 2.

Median cost differences between HBIG and HIP in various phases of immunoprophylaxis.

Table 2.

Escalation Rate of HBIG versus HIP for Anhepatic, Loading and Maintenance Dose.

| Type of drug (no. Of pts started) | Anhepatic and loading dose | Maintenance dose | Total of both the doses (range) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Escalation rate | 17.0 times | 4.3 times | 13.9 times |

| KW Sign rank Sum test P value | <0.00001 | <0.00001 | <0.00001 |

Discussion

Commercial HBIG has been a great boon in preventing HBV recurrence after HBV related LT. The optimal HBIG dosage and duration is yet not defined and there is no consensus of opinion on this. Worldwide, an anti HBs antibody titer of 100 IU/L is considered as ideal during long term therapy to prevent HBV recurrence after LT.18 In our study, despite high doses of HBIG, the anti HBs titer seldom reached 100 IU/L. The low anti HBs however, did not result in resurgence of the HBV. This was also our observation in a recently concluded study on anti HBs response to HBIG.19

Several attempts9,10,12,13 have been made in the past to reduce the cost of post LT maintenance prophylaxis against HBV recurrence. These include switching over from intravenous to intramuscular administration of HBIG, prolonging the interval between HBIG dose and finally tailoring the dose without following a fixed time schedule,15,20 HIP has been used in some centers16,20,21 as a cheap and effective alternative to commercial HBIG. The target with any form of treatment has been to attain a safe anti HBs titer (from 300 to 500 IU/L to 100 IU/L).

More recently, studies have looked into long term maintenance with nucleoside analog as monotherapy and risk of HBV recurrence. In one such study, the HBV recurrence risk was 9% at 4 years4; Roche et al13 reported HBV DNA recurrence of 45% at the end of 10 years but with low HBV recurrence risk.

The present study has highlighted the cost incurred with varying doses of HBIG and HIP. All recipients were on entecavir. The outcome of the study has shown that the treatment schedule with HIP was cost effective with good patient compliance. The maintenance dose required was less frequent during the maintenance phase when compared to HBIG. Procurement of HIP was easy as the samples were preserved as fresh frozen plasma and small aliquots were available as and when required by the recipient. A major observation was that the anti HBs titer achieved with HIP was much higher compared to commercial HBIG, particularly after the third month. There were no blood borne transmission of infection or transfusion associated reaction with HIP.

Low anti HBs titer with HBIG was not associated with HBV recurrence in our study. This observation is similar to reports from other centers, where low anti HBs was reported to be not detrimental.9,22,23

World over, there is a recent trend to shift from HBIG related immunoprophylaxis towards monotherapy with anti virals.24 However long term results are awaited from these studies. At present, we believe that until guidelines are available on immune-prophylaxis for post liver transplant HBV recurrence, high anti HBs titer plasma (HIP) is a good and cheap alternative to expensive commercial HBIG when given in combination with nucleoside analogs.

In conclusion, HIP in combination with oral nucleoside analogs seems to have a cost beneficial role in management of chronic HBV infection for the initial 6 months.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have none to declare.

Acknowledgment

The authors are very grateful for the help in data entry and analysis in this study rendered by Mr. Tom Michael, Global Hospitals, Chennai.

References

- 1.Lok A.S. Prevention of recurrent hepatitis B post liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2002;8:867–873. doi: 10.1053/jlts.2002.35780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roche B., Samuel D. Evolving strategies to prevent HBV recurrence. Liver Transpl. 2004;10:S74–S85. doi: 10.1002/lt.20258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Villami F.G. Prophylaxis with anti HBs immune globulins and nucleoside analogues after liver transplantation for HBV infection. J Hepatol. 2003;39:466–474. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(03)00396-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wong S.N., Chu C.J., Howell T. Low risk of hepatitis B virus recurrence after withdrawal of long term hepatitis B immunoglobulins in patients receiving maintenance nucleoside analogue therapy. Liver Transpl. 2007;13:374–381. doi: 10.1002/lt.21041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Neoumov N.V., Lopes A.R., Burra P. Randomised trial of lamivudine versus hepatitis B immunoglobulin for long term prophylaxis of hepatitis B recurrence after liver transplantation. J Hepatol. 2001;34:888–894. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(01)00039-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zheng S., Chen Y., Liang T. Prevention of hepatitis B recurrence using lamivudine or lamivudine combined with hepatitis B immunoglobulin prophylaxis. Liver Transpl. 2006;12:253–258. doi: 10.1002/lt.20701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Angus P.W., Patterson S.J., Strasser S.I., McCaughan G.W., Gane E. A randomized study of adefovir dipivoxil in place of HBIG in combination with lamivudine as post-liver transplantation hepatitis B prophylaxis. Hepatology. 2008;48:1460–1466. doi: 10.1002/hep.22524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Angus P.W., McCaughan G.W., Gane E.J., Crawford D.H., Harley H. Combination low-dose hepatitis B immune globulin and lamivudine therapy provides effective prophylaxis against post transplantation hepatitis B. Liver Transpl. 2000;6:429–433. doi: 10.1053/jlts.2000.8310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gane E.J., Angus P.W., Strasser S. Lamivudine plus low-dose hepatitis B immunoglobulin to prevent recurrent hepatitis B following liver transplantation. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:931–937. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ferretti G., Merli M., Ginanni Corradini S. Low-dose intramuscular hepatitis B immune globulin and lamivudine for long-term prophylaxis of hepatitis B recurrence after liver transplantation. Transpl Proc. 2004;36:535–538. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2004.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shouval D., Samuel D. Hepatitis B immune globulin to prevent hepatitis B virus graft reinfection following liver transplantation: a concise review. Hepatology. 2000;32:1189–1195. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2000.19789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Samuel D., Muller R., Alexander G. Liver transplantation in European patients with the hepatitis B surface antigen. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1842–1847. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199312163292503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roche B., Feray C., Gigou M. HBV DNA persistence 10 years after liver transplantation despite successful anti-HBS passive immunoprophylaxis. Hepatology. 2003;38:86–95. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lake J.R. Do we really need long-term hepatitis B hyperimmune globulin? What are the alternatives? Liver Transpl. 2008;14(suppl 2):S23–S26. doi: 10.1002/lt.21637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coffin C.S., Terrault N.A. Management of hepatitis B in liver transplant recipients. J Viral Hepatol. 2007;14(suppl 1):37–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2893.2007.00916.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bihl F., Rusman S., Gurtner V. Hyperimmune and anti HBs plasma as an alternative to commercial immunoglobulins for prevention of HBV recurrence after liver transplantation. BMC Gastroenterol. 2010;10:1–10. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-10-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Government of India . 1945. Drugs and Cosmetics Rules.http://www.cdsco.nic.in/html/Drugs&cosmeticsAct.pdf amended till 30th June 2005, Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mentha G., Giostra E., Negro F. High-titered anti-HBs fresh frozen plasma for immunoprophylaxis against hepatitis B virus recurrence after liver transplantation. Transpl Proc. 1997;29:2369–2373. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(97)00407-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Varghese J., Reddy M.S., Cherian T., Vijaya S., Jayanthi V., Rela M. Anti HBs response to hepatitis B immunoglobulin prophylaxis in liver transplant recipients. Indian J Gastroenterol. 2014;33:226–230. doi: 10.1007/s12664-014-0457-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Terrault N.A., Vyas G. Hepatitis B immune globulin preparations and use in liver transplantation. Clin Liver Dis. 2003;7:537–550. doi: 10.1016/s1089-3261(03)00045-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Laryea M.A., Watt K.D. Immunoprophylaxis against and prevention of recurrent viral hepatitis after liver transplantation. Liver Transplant. 2012;18:514–523. doi: 10.1002/lt.23408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Iacob S., Hrehoret D., Matei E. Costs and efficacy of “on demand” low-dose immunoprophylaxis in HBV transplanted patients: experience in the Romanian program of liver transplantation. J Gastrointest Liver Dis. 2008;17:383–388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Testino G., Borro P., Sumberaz A. Prophylaxis of hepatitis B virus recurrence after liver transplantation. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2009;18:139–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fung J., Cheung C., Chan S.C. Entecavir monotherapy is effective in suppressing hepatitis B virus after liver transplantation. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:1212–1219. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.06.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]