Abstract

Patients with end stage or terminal HCC are those presenting with tumors leading to a very poor Performance Status (ECOG 3–4) or Child–Pugh C patients with tumors beyond the transplantation threshold. Among HCC patients, 15–20% present with end stage or terminal stage HCC. Their median survival is less than 3–4 months. The management of end stage or terminal HCC is only symptomatic and no definitive tumor directed treatment is indicated. Patients with end stage or terminal HCC should receive palliative support including management of pain, nutrition and psychological support. In general, they should not be considered for participating in clinical trials. This review focuses on palliative care of terminal stage HCC.

Keywords: hepatitis B virus (HBV), hepatitis C (HCV), hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC)

Abbreviations: ACS, anorexia-cachexia syndrome; CBT, cognitive-behavioral therapy; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCC, hepatocellular carcinoma; HCV, hepatitis C virus; QOL, quality of life; RT, radiotherapy; THC, tetrahydrocannabinol; WBRT, whole-brain radiation therapy

Worldwide, HCC is the fifth most common of all malignancies and causes approximately one million deaths annually worldwide.1 Incidence of HCC is highest in Africa and Asia, where viral hepatitis is endemic. According to the age adjusted HCC incidence per 100,000 population per annum, different geographic regions can be divided into three incidence zones: low (<5), intermediate (between 5 and 15), high (>15).2 Most Asian countries are in intermediate or high incidence zones of HCC. The prevalence of HCC in India varies from 0.2% to 1.6%.3,4 The geographic model of HCC occurrence is frequently correlated with the etiologic factors. Hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection is the most common etiologic factor in high incidence areas, while hepatitis C (HCV) infection is more prevalent in the low incidence areas.5,6 Unlike other low incidence zone, in India HBV is the main etiological factor associated with HCC.7–10

In west, majority of HCC are diagnosed incidentally during routine evaluation. However, in India, HCC is often diagnosed at advanced stages and prognosis is generally poor when the tumor is unresectable.8,9 This extremely guarded prognosis is frequently coupled with severe symptom occurrence including pain, fatigue, anorexia, and ascots.11 This in turn impacts patients' quality of life (QOL) and functional status.

The purpose of this article is:

-

1)

to describe the current state of the science on symptom management in terminal HCC

-

2)

to propose an evidence based consensus on best palliative care in terminal HCC

Definition of terminal Hepatocellular Carcinoma

Patients with end stage or terminal HCC are those presenting with tumors leading to a very poor Performance Status (ECOG 3–4) or Child–Pugh C patients with tumors beyond the transplantation threshold,12 which correspond to patient with BCLC class D.

Among HCC patients, 15–20% present with end stage or terminal stage HCC.8,9 Their median survival is less than 3–4 months.8,13,14 The pooled estimate of terminal stage HCC 1-year survival rate was 11% (95% CI, 4.7–22; range, 0–57%), in a meta analysis.15 Due to such dismal prognosis, the management of end stage or terminal HCC is only symptomatic and no definitive tumor directed treatment is indicated. Patients with end stage or terminal HCC should receive palliative support including management of pain, nutrition and psychological support. In general, they should not be considered for participating in clinical trials.

Consensus Statement

Patients end stage or terminal HCC have a poor survival and should receive palliative support including management of pain, nutrition and psychological support. In general, they should not be considered for participating in clinical trials [Level of evidence 2 b, Grade of recommendation B].

What is palliative care?

Palliative care is an approach that improves the quality of life of patients and their families facing the problem associated with life-threatening illness, through the prevention and relief of suffering by means of early identification and impeccable assessment and treatment of pain and other problems, physical, psychosocial, and spiritual.16

HCC patients in the terminal stage of disease may present with a variety of symptoms related to decompensated cirrhosis including ascites, variceal bleeding, peripheral edema, and hepatic encephalopathy. Besides these symptoms, abdominal pain has been reported as the most common symptom (approx 2/3rdof patients), which originated from enlarged tumor mass and was characterized as dull visceral pain.9,17 Other common complaints include fatigue or weakness, peripheral edema, cachexia, ascites, dyspnea, anorexia, and vomiting.9,17 Patients diagnosed with HCC were found to have the third highest reported level of psychological distress or depression among patients with 14 other types of cancer.18

The concept of symptom clusters has recently gained prominence. Symptom clusters consist of 2 or more symptoms that are related to each other and that occur together.19,20 The clusters are composed of stable groups of symptoms, are relatively independent from other clusters, and may uncover specific underlying dimensions of symptoms. Symptoms within a cluster may or may not share a common etiology, and the relationship among symptoms within a cluster is associative rather than causal.19 The exploration of potential symptom clusters is critical to the development of effective symptom management strategies for HCC patients. Furthermore, it is well-documented that unrelieved symptoms have a negative effect on patient outcomes, including functional status, mood states, and quality of life (QOL).21 This understanding is of particular importance in caring for terminal stage HCC patients.

Delivery of supportive care for HCC includes pain management, nutrition management, symptom management, psychosocial needs and advanced disease issues.

Pain management in terminal stage Hepatocellular Carcinoma

Pain in HCC can be either from disease or treatment, but irrespective of the cause it is very common and significant cause of morbidity. The pain of HCC tends to be most prominent in the right upper quadrant and described as deep, aching, sharp or stabbing. It may be intermittent and often is referred to the shoulder. Abdominal pain may be categorized as parietal (from inflammation of the visceral lining) or visceral (from spasm, contraction or distension of organs). Abdominal pain in HCC is due primarily to visceral involvement that originates from a primary or metastatic lesion involving the abdominal or pelvic viscera.22 The treatment of pain in HCC patients begins with a comprehensive assessment of the clinical characteristic of visceral pain. Referred visceral pain in HCC is often found in the right shoulder.22 A numeric pain scale should be used to assess pain and, recognizing its often transient nature it needs to be reassessed frequently.

Specific Drugs Use in Cirrhosis

The choice of appropriate analgesic agents requires a thorough understanding of their pharmacokinetic and side effect profiles. Susceptibility to adverse effects increases with worsening liver function due to altered pharmacokinetics and hemodynamic changes.

Nonselective NSAIDs

NSAIDs are associated with an increased risk of variceal hemorrhage, impaired renal function, and the development of diuretic resistant ascites. Thus, NSAIDs (including aspirin) should generally be avoided in patients with advanced chronic liver disease or cirrhosis.23

Selective COX-2 Inhibitors

Selective COX-2 inhibitors are associated with a decreased incidence of gastrointestinal and renal toxicity as compared to nonselective NSAIDs. However, they have been associated with an increased incidence of adverse cardiovascular events. However, these agents should not be used in patients with advanced liver disease or cirrhosis because data are limited on their use in such patients.24

Opioids

A variety of opioids are used for pain control. Opioids are the drugs of choice for visceral pain. As a general rule, these medications are metabolized through hepatic oxidation and glucuronidation. The clearance of opioids depends upon plasma protein binding, hepatic blood flow, and hepatic enzyme capacity. Oxidative enzyme pathways and opioids clearance are impaired in cirrhosis, which may lead to the accumulation of toxic metabolites.

Morphine undergoes rapid glucuronidation in the liver with subsequent systemic metabolism. Although glucuronidation is usually preserved despite diminished liver function, studies have demonstrated that the clearance of morphine is delayed in patients with cirrhosis by 35–60 percent.25,26 In addition, morphine has increased oral bioavailability in patients with advanced chronic liver disease or cirrhosis secondary to reduced first pass hepatic metabolism.26 Thus, morphine must be used with caution in patients with advanced chronic liver disease or cirrhosis to avoid accumulation. A twofold increase in the interval of administration has been recommended.27 If oral forms of morphine are used, the dose must be decreased to account for the increased bioavailability. In a patient with cirrhosis with concomitant renal failure, morphine should be avoided as an accumulation of hydrophilic metabolites can lead to seizure activity, respiratory depression, and hepatic encephalopathy.

Meperidine is metabolized extensively in the liver, and its clearance is significantly affected by hepatic dysfunction. In patients with cirrhosis, the plasma clearance is diminished by 50 percent and the half life doubles after a single intravenous dose of 0.8 mg/kg.28,29 In addition, it is highly bound to serum protein and has unpredictable analgesic effects and an increased risk of toxicity in patients with cirrhosis.30 Thus, meperidine should be avoided in patients with advanced chronic liver disease or cirrhosis.

Codeine requires the oxidative enzyme capacity of the liver to convert it to its active metabolites, potentially decreasing its effectiveness in patients with advanced chronic liver disease or cirrhosis.

Tramadol also requires conversion to O-desmethyltramadol by hepatic oxidation so the analgesic effects of this drug may be unpredictable.31

Fentanyl is a lipid soluble synthetic opioid that is about 80–100 times as potent as morphine. It is converted by hydroxylation and dealkylation in the liver into inactive and nontoxic metabolites. In a study of patients with histologically confirmed cirrhosis, the pharmacokinetics of fentanyl were unchanged when compared to healthy subjects.32 However, the patients with cirrhosis in this study had normal serum albumin and the prothrombin times were only slightly abnormal. It is not known if the metabolism of fentanyl is affected in patients with severe hepatic dysfunction.

Oxycodone is a derivative of opium that has similar opioid effects to morphine. Oxycodone is metabolized in the liver and excreted by the kidneys. In patients with mild to moderate hepatic dysfunction showed that peak plasma concentrations of oxycodone is 50 percent greater compared to those in healthy controls. Oxycodone should be used with caution in patients with advanced chronic liver disease or cirrhosis, and if used, it should be administered at reduced doses and prolonged dosing intervals.

Hydromorphone is a hydrogenated ketone of morphine that is metabolized by the liver. This opiate lacks toxic metabolites, but is five times stronger than morphine. In patients with advanced chronic liver disease or cirrhosis, the elimination of hydromorphone is impaired and the half life is prolonged. Hydromorphone, like oxycodone, should be used with caution in patients with advanced chronic liver disease or cirrhosis, and if used, it should be administered at reduced doses and prolonged dosing intervals.

Methadone is a long-acting opioid. In a study of patients with mild to moderate cirrhosis, the pharmacokinetic profiles of methadone were unchanged compared to healthy individuals.33 Although the half life of methadone in patients with severe cirrhosis can be mildly prolonged, drug disposition is not significantly altered.33 Thus, methadone appears to be safe in patients with advanced chronic liver disease or cirrhosis, at least for short-term administration.

Acetaminophen (Paracetamol)

Acetaminophen is an effective and safe analgesic for patients with chronic liver disease, provided that they do not actively drink alcohol. While doses up to 4 g per day appear to be safe, it is frequently recommended that patients with cirrhosis or advanced chronic liver disease limit acetaminophen intake to 2 g per day, in part because of concern over altered metabolism of acetaminophen in the setting of chronic liver disease.34 Acetaminophen appears to be safe in patients with advanced chronic liver disease or cirrhosis when used at the recommended doses. In one study, six patients with chronic liver disease were given 4 g per day for five days. There was no evidence of drug accumulation or hepatotoxicity in these subjects.35 In another trial by the same author, 20 patients with cirrhosis were given 4 g per day for 13 days.36 Only one patient developed abnormal liver enzymes. After the labs returned to normal, the same patient was subsequently challenged with 10 and 14 day courses of 4 g per day of acetaminophen without incident. It was thought that the earlier biochemical deterioration in this patient was not related to acetaminophen use.

Corticosteroids

In palliative care, glucocorticoids are often used to alleviate symptoms such as pain, nausea, fatigue, anorexia, and malaise, and improve overall quality of life. A large body of clinical experience suggests that glucocorticoids may be beneficial for a variety of types of pain, including neuropathic and bone pain, pain associated with capsular expansion or duct obstruction, pain from bowel obstruction, pain caused by lymph edema, and headache caused by increased intracranial pressure, although few randomized trials have been conducted to assess the analgesic properties of glucocorticoids, and the quality of the evidence is very low.37 The mechanism of analgesia probably relates to reduction of tumor-related edema, anti-inflammatory effects, and direct effects on nociceptive neural systems. Dexamethasone is usually preferred for the management of cancer-related pain, presumably because of its long half life and relatively low mineralocorticoid effects. However, there is no empiric evidence that this drug is either safer or more effective in the cancer population than any other glucocorticoid. Prednisone and methylprednisolone are acceptable alternatives. A typical regimen for patients with cancer-related pain is 1–2 mg of dexamethasone orally or parenterally twice daily; this may be preceded by a larger loading dose of 10–20 mg. Patients may do well with lower or higher doses, or with once-daily rather than twice-daily dosing. Regardless of the regimen that is selected, the intent is usually for ongoing chronic use in the setting of advanced illness. In this situation, the risk of long-term toxicity, which includes myopathy, immunocompromise, psychotomimetic effects, and hypoadrenalism, is attenuated by limited life expectancy and the need to address the multiple sources of suffering. Originally developed for the treatment of emerging epidural spinal cord compression (including cauda equina syndrome), a brief period of high-dose glucocorticoids is appropriate for any “pain crisis”, which is defined as severe and escalating pain that is not responding sufficiently to an opioid. In such cases, a typical regimen consists of a dexamethasone loading dose of 50–100 mg intravenously, which may be followed by 12–24 mg four times daily; this dose is then tapered over one to three weeks.

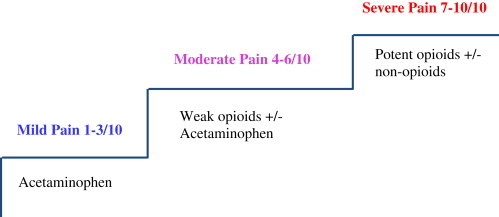

A stepwise approach to management of cancer pain that includes both opioid and nonopioid drugs has been codified in the World Health Organization's (WHO) “analgesic ladder” approach to cancer pain management. There are no studies specifically assessing pain management in HCC patients, but like other cancer-related pain WHO pain management ladder may also be useful in management of pain in HCC. However, caution must be exercised for specific drugs as above [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

World Health Organization (WHO) analgesic ladder [modified for HCC].

One systematic review of RCTs of opioids for cancer pain [not specifically in HCC patients] showed fair evidence for the efficacy of transdermal fentanyl and poor evidence for morphine, tramadol, oxycodone, methadone, and codeine.38 Patients may be started on morphine or oxycodone and the morphine equivalence dose to control pain is calculated before switching patient to Transdermal fentanyl patch.

For some specific pain due to organ involvement local treatment may be required, for e.g. pain due to bone metastasis local radiotherapy and cementoplasty may be effective.

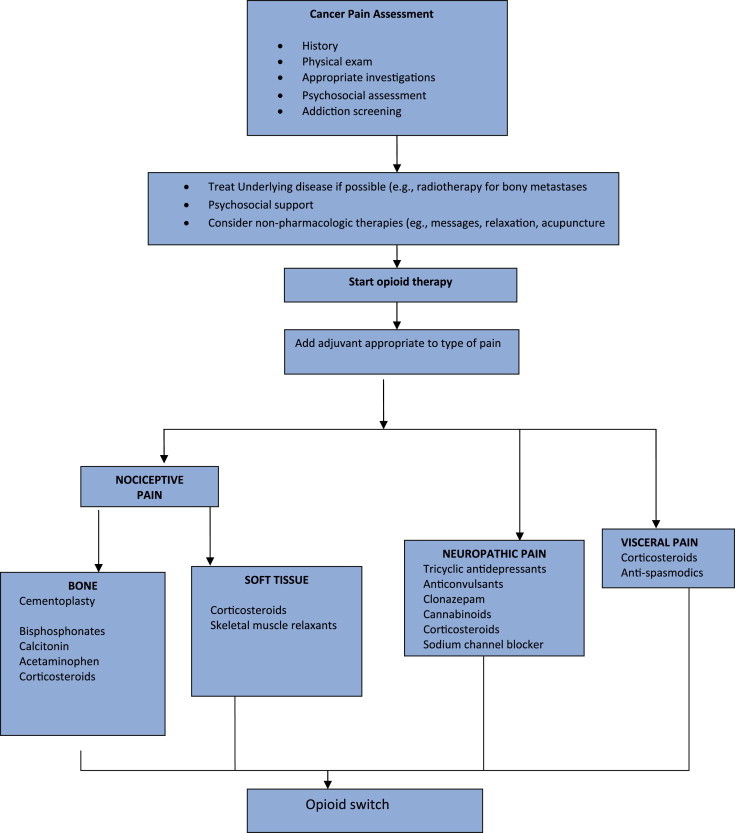

Figure 2 shows the general pain management strategies in palliative care for terminal stage HCC.

Figure 2.

General pain management strategies in palliative care for terminal stage HCC.

General Pain Management Strategies that should be kept in mind include:

-

•

Continuous pain requires continuous analgesia; prescribe regular dose versus as and when required.

-

•

Start with regular short-acting opioids and titrate to effective dose over a few days before switching to slow release opioids.

-

•

Once pain control is achieved, long-acting (q12h oral or q3days transdermal) agents are preferred to regular short-acting oral preparations for better compliance and sleep.

-

•

Always provide appropriate breakthrough doses of opioid medication, ∼10% of total daily dose dosed q1h prn.

-

•

Incident pain (e.g., provoked by activity) may require up to 20% of the total daily dose, given prior to the precipitating activity.

-

•

Record patient medications consistently

Consensus Statement

Morphine and derivatives are the first choice and fentanyl is an excellent option in patients with impaired liver functions [Level of evidence 5, Grade of recommendation D].

Role of radiotherapy in terminal stage Hepatocellular Carcinoma

Physicians have long overlooked radiotherapy (RT) for HCC as radiation might induce fatal hepatic toxicity at doses lower than the therapeutic doses.39 However, such limitation has been overcome by recent developments in RT technology involving precise delivery of focused high-dose on partial volume of the liver.40

Patients with HCC in terminal stage need full symptomatic palliation for local disease or distant metastasis. The most frequent sites of metastases from HCC are the lungs and lymph nodes, followed by the skeletal system.41,42 Palliative RT is indicated for metastasis to lymph node, bone, brain, or other sites.

In one retrospective study from china on 13 HCC patients with pulmonary metastases, 23 out of a total of 31 pulmonary metastatic lesions received EBRT. In 12/13(92.3%) patients, significant symptoms were completely or partially relieved. An objective response was observed in 10/13(76.9%) of the subjects by computed tomography imaging. The median progression-free survival for all patients was 13.4 months.41 However, appropriate selection of candidates for such therapy is important, as patients with terminal stage HCC have very limited life expectance.

For lymph node metastases from HCC, RT doses of 45 Gy or higher have been suggested to achieve a significant response. Response rates ranging from 60 to 76% have been reported in retrospective studies.43,44

For painful bone metastasis, various retrospective studies have shown that RT showed complete pain relief in 50% of patients and partial pain relief in 80%–90%.45–47

One Japanese study that evaluated the therapeutic effects of RT on spinal metastases from HCC, reported the ambulatory rate of 85% after 3 months and 63% after 6 months, and the local progression-free rate was 53% after 3 months and 47% after 6 months.48 Only accelerated radiotherapy can be proposed in such situations.

Percutaneous cementoplasty is also an effective treatment for painful bone metastasis from hepatocellular carcinoma Percutaneous cementoplasty can provide pain relief and improvement of quality of life, though without survival benefits, for HCC patients with painful bone metastasis.49

Brain metastasis from HCC is extremely rare. Choi et al carried out a retrospective review of 62 patients. Seventeen of them were treated with whole-brain radiation therapy (WBRT) alone, 10 others with gamma knife surgery alone, 6 patients surgical resection only, and 5 patients with surgical resection followed by WBRT. The median survival time was 6.8 weeks (95% confidence interval, 3.8–9.8 weeks) since diagnosis of brain metastasis. Treatment modality, number of brain lesions, and Child–Pugh classification represented significant prognostic factors for survival.50 In terminal stages HCC with brain metastases, stereotaxic radiotherapy may be proposed in highly selected cases.

Consensus Statement

Radiotherapy can be used to alleviate pain in patients with bone metastasis and relieve of symptoms from pulmonary or lymph node metastases [Level of evidence 4, Grade of recommendation C].

Percutaneous cementoplasty is also an effective treatment for painful bone metastasis from hepatocellular carcinoma [Level of evidence 4, Grade of recommendation C].

Nutrition management in terminal stage Hepatocellular Carcinoma

Malnutrition is commonly encountered in patients with liver disease, especially those with end-stage processes. Patients with liver diseases, especially decompensated cirrhosis, commonly have weight loss and muscle wasting. This problem is due to a variety of underlying processes, including poor caloric and other nutrient intake, problems with the assimilation and absorption of ingested nutrients, and abnormalities in metabolism. Nutritional status assessment is important for identifying the risk of deteriorating quality of life or functional status, in patients with HCC.51 Prognostic nutritional index, has been found to be independently associated with overall survival in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma.52 It is known that patients with weight loss and muscle wasting have poorer clinical outcomes than patients without such weight loss or muscle wasting. As a consequence, efforts have been made to supply nutrients with the intent of improving the nutritional status.

There are only few RCTs on nutritional intervention in HCC patients; with none specifically in terminal stage HCC. One trial of parenteral nutrition53 and five of supplements54–58 included patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. The current data do not compellingly justify the routine use of parenteral nutrition, enteral nutrition, or oral nutritional supplements in these patients.59

As there are no trials of nutritional intervention in terminal stage HCC, the decision for or against artificial nutrition (enteral or parenteral) is especially difficult in palliative care of such patients who have entered their final phase of life. Quality of life is certainly the most important criteria in patients with terminal cancer in general and is mainly dependent on nutritional status.60

Nutritional intervention should be considered in cases of low energy intake for a longer period of time.61 As terminal HCC patients may also have fluid retention and ascites, oral supplementation should be preferred. Home enteral and parenteral nutrition not only allows the patients to be at home, but also is more cost-effective than in-patient care. If life expectancy is < 3 months and/or Karnofsky-Index <50%, the indication for parenteral nutrition should be thoroughly reviewed. However, implementation of home parenteral nutrition should be always seen in context of the patients' wish, medical condition, family and therapeutic objectives. During the very final phase of life, hydration with 1000–1500 mL (i.v. or s.c.) of isotonic saline is often sufficient. At the very final time of life, at least every decision on therapeutic interventions should base on the individual situation and needs of the patients.

Consensus Statement

Routine artificial nutrition is not justified in patients in the terminal stage HCC [Level of evidence 5, Grade of recommendation D].

In individual cases, dietary counseling and artificial nutrition can slow down nutritional deprivation, avoid dehydration and improve the quality of life [Level of evidence 5, Grade of recommendation D].

Symptom management in terminal stage Hepatocellular Carcinoma

Symptom management in terminal stage HCC includes management of anorexia, fatigue, ascites, nausea/vomiting, pruritus and constipation.

Anorexia–Cachexia

Weight loss is a frequent problem in HCC patients. Cachexia can be separated into primary (metabolic) and secondary (starvation) cachexia. Anorexia is besides weight loss, a leading symptom of the primary metabolic cachexia syndrome, therefore a common term for cancer wasting syndrome is anorexia-cachexia syndrome (ACS)62]. The diagnosis of ACS is based on simple assessment of weight loss and anorexia, but currently no established tools or guidelines are available to distinguish primary and secondary cachexia. Other parameters, such as hypoalbuminemia, asthenia, chronic nausea, reduced caloric intake, or clinical judgment of reduced muscle and fat mass can serve as additional criteria for the presence of cachexia.62 These criteria can be helpful in HCC patients with relevant fluid retention (ascites, edema) where the extent of weight loss is masked by the accumulation of excess fluid.

A thorough assessment of potential contributors such as chronic nausea, constipation, early satiety, taste alterations, and depression should be done. Many RCTs have demonstrated that megestrol acetate (doses ranging from 160 to 1600 mg/day) significantly improves appetite when compared to placebo.63 Artificial nutrition such as total parenteral nutrition is frequently used but has not been shown to increase lean body mass.64 Individualized dietary counseling in recent RCTs in cancer patients is effective in improving patient's food intake, nutritional status, and QOL.65

Fatigue

One common and distressing symptom in cancer patients is fatigue.

In-depth assessment of the following contributing factors should be done: pain, emotional distress, sleep disturbance, anemia, nutritional deficiencies, deconditioning, and comorbidities.66 Treating these factors as an initial approach may increase the tolerability of fatigue. Pharmacologic interventions are targeted toward the contributing factor associated with fatigue for example, antidepressants when depression is a cause of fatigue, and psychostimulants to increase energy level. There is some evidence in the literature to support the use of methylphenidate in reducing fatigue in advanced cancer.67 The efficacy of non-pharmacologic interventions such as aerobic exercise on fatigue reduction has been proven by a recent meta-anlysis,68 although there are no studies in terminal stage HCC. Counseling on proper sleep hygiene and energy conservation tips are helpful self-care strategies that patients can utilize at home. A careful review of patients' medications may identify adverse effects that aggravate fatigue.

Ascites

The accumulation of ascites is a result of an imbalance in the normal state of influx and efflux of fluid from the peritoneal cavity. Symptoms related to ascites include increased intra-abdominal pressure, abdominal wall discomfort, dyspnea, anorexia, early satiety, nausea and vomiting, esophageal reflux, pain, and peripheral edema. Diuretics remain the standard in management of ascites. A potassium-sparing diuretic in combination with a loop diuretic is helpful in the treatment of ascites secondary to hepatic cirrhosis. Abdominal paracentesis can be used for quick symptomatic relief and may be used in HCC patients when diuretics are either ineffective or requires a significant lag period prior to efficacy.

Nausea and Vomiting

Nausea and vomiting could be either chemotherapy/radiation-related or non-chemotherapy and non-radiotherapy-related nausea/vomiting. An approach that is based upon the clinically determined mechanism of emesis has been suggested, although many of the guidelines for terminal stage cancer are not supported by good quality evidence.69,70 Patients should be advised to take small frequent meals. For patients with opioid-related nausea, opioid rotation is an appropriate choice. For patients with gastroparesis, metoclopramide is a reasonable first choice, glucocorticoids may provide benefit for patients with elevated intracranial pressure, and for patients with malignant bowel obstruction, symptomatic improvement may be seen with glucocorticoids and octreotide.

A 5-HT3 antagonist such as ondansetron or an anticholinergic agent such as scopolamine, or an antihistamine, such as meclizine, may be used. The use of medical marijuana for refractory nausea in terminally ill patients is very controversial. Medical use of marijuana is legal in several countries, including the Netherlands and Canada. Dronabinol is a prescription form of tetrahydrocannabinol (THC), one of the active agents in marijuana. It can be legally prescribed. However, there can be disturbing central nervous system side effects, particularly among older individuals.

Pruritus

Pruritus, can range in severity from mild, to moderate in which sleep is disturbed, to extreme in which the lifestyle of the patient is completely disrupted. The pathogenesis of pruritus is unknown but several hypotheses have been proposed, including bile acid accumulation and increased opioidergic tone. As a general rule, treatment should be based upon the severity of the pruritus. In mild cases, pruritus can often be controlled by nonspecific measures such as warm baths and emollients with or without an antihistamine. However, these measures often fail when the pruritus is moderate to severe and often accompanied by excoriations. For moderate to severe pruritus, or mild pruritus that does not respond to the above measures, cholestyramine or colestipol can be tried. Many patients cannot tolerate these or find them unpalatable. Rifampin may be tried in these patients. Opiate antagonists such as naltrexone can be used in refractory cases.71

Constipation

Bowel movements vary in frequency between individuals, ranging from one every third day to three per day. The term constipation has varied meanings for different people. For some, it may mean that stools are too hard or too small, or that defecation is too difficult or infrequent. The first three complaints are difficult to quantify in clinical practice; the last can be measured and compared to the general population. Risk factors for constipation in patients with a serious or life-threatening illness include advanced disease, older age, decreased physical activity, low fiber diet, depression, and cognitive impairment. Medications which can cause or exacerbate constipation include opioids, calcium channel blockers, diuretics, anticholinergic drugs, iron, serotonin antagonists, and chemotherapy (e.g Vinka alkaloids, cisplatin, thalidomide). There are also neural (e.g., epidural spinal cord compression) and metabolic abnormalities (hypercalcemia, hypokalemia and hypothyroidism) which may cause or contribute to constipation.

Opioid prescription must be linked to a bowel program. If taking opioids regularly, must use bowel regimen regularly, do not wait for severe constipation to start. Treatment of constipation initially starts with addressing underlying, potentially reversible factors. If a reversible cause cannot be identified and modified, symptomatic treatment is appropriate. Pharmacologic treatments including bulk-forming laxatives (cellulose, psyllium, bran), osmotic laxatives (lactulose, sorbitol, polyethylene glycol, magnesium hydroxide, magnesium citrate), surfactants (docusate), stimulant laxatives (senna, bisacodyl, castor oil) may be helpful.72,73 Enemas and/or suppositories may be indicated for distal fecal impaction or if a patient has not had bowel movement for three days or more. Bulk agents such as psyllium are typically not used in advanced disease. Patients with refractory opioid-induced constipation may benefit from the use of methylnaltrexone, but it requires parenteral administration. Oral naltrexone has minimal systemic absorption and can be a convenient oral agent for treating opioid-induced constipation.

Psychosocial issues in terminal stage Hepatocellular Carcinoma

Psychosocial and spiritual concerns are nearly universal among patients who are conscious as they near the end of life.

Prerequisites for Addressing Psychosocial and Spiritual Issues

Management of psychosocial and spiritual issues at the end of life presumes control of physical suffering and a secure and supportive relationship between the patient and his or her clinicians. Physical discomfort is one of the greatest concerns as patients with a terminal illness anticipate dying. Effective symptom management allows patients and their families to focus on maintaining hope, reaffirming important connections, and attaining a sense of completion. Also Psychological, social and spiritual factors may exacerbate physical suffering. The relationship between patient and clinician can be an important source of solace for patients and their families, and should be as cordial as possible.

Concerns of Terminally Ill Patients

Some common concerns voiced by patients with terminal illness include the meaning of the illness, spiritual uncertainty, loss and grief, fear of increasing dependency on other, uncertainty and fear about the future and worried about loved ones. Keeping these concerns in mind can help the clinician to diagnose, acknowledge, anticipate, and respond effectively to patient and family distress.74

Methods of Coping

Terminal illness inevitably evokes great distress in patients and families and clinicians, engendering fear, anxiety, anger, dread, sadness, helplessness, and uncertainty. Hope permits patients and their families to cope with these difficult emotions and helps them endure the stresses of treatment. One goal of physical and psychosocial intervention is to improve coping by identifying difficulties that can be ameliorated.75 Family and social support is an important component of coping.

Denial is a psychological mechanism by which a patient rejects either completely or in part the repercussions and effects of an illness (or treatment) thus avoiding painful feelings such as hopelessness, fear, anxiety, grief, and anger. If denial is interfering with care, relationships or end-of-life planning, the clinician should address it gently. If denial is constructive, enhancing the patient's life without adversely affecting relationships or care, it should not be confronted.

Financial pressures can be an important factor in the ability of patients and their families to cope with terminal illness, which should be addressed.

Psychosocial Complications

The will to live may fluctuate at the very end of life as a result of grief, the physical toll taken by the illness, and/or spiritual, family, and personality issues. Depression, anxiety, or organic mental disorders may contribute to this instability.

Cancer patients with adjustment disorder may respond to brief psychotherapy that addresses cancer-related stressors by teaching coping skills and focusing upon immediate problems. Successful treatment of depression or anxiety in cancer patients often requires a combination of pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic interventions.76 Many antidepressants are available to treat patients with cancer, however caution should be exercised in terminal HCC patients in view of deranged liver functions. Nonpharmacologic interventions for depressed cancer patients include crisis intervention, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT), and support groups. The mainstay of pharmacotherapy for anxiety disorders is a benzodiazepine, but these have severe side effects in cirrhotic patients. Lorazepam, oxazepam, and temazepam are preferred due to their primary elimination by glucuronidation, which is selectively spared in the presence of liver disease. Nonpharmacologic interventions for anxiety include supportive psychotherapy and behavioral interventions (e.g., relaxation and guided imagery). The standard approach for managing delirious cancer patients includes determining and correcting underlying causes, and management of symptoms. Low dose haloperidol is effective for treatment of delirium that includes agitation, paranoia, and fear.

Consensus Statement

Management of psychosocial and spiritual issues should be a part of the care of terminal HCC patients [Level of evidence 5, Grade of recommendation D].

Conflicts of interest

All authors have none to declare.

References

- 1.McCracken M., Olsen M., Chen M.S., Jr. Cancer incidence, mortality, and associated risk factors among Asian Americans of Chinese, Filipino, Vietnamese, Korean, and Japanese ethnicities. CA Cancer J Clin. 2007;57:190–205. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.57.4.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bosch F.X. Global epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma. In: Okuda K., Tabor E., editors. Liver Cancer. Churchill Livingstone; New York: 1997. pp. 13–27. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Annual Report 1987. National Cancer Registry Programme. New Delhi, Indian Council of Medical Research, 1990.

- 4.Jayant K., Rao R.S., Nene B.M., Dale P.S. Rural Cancer Registry; Barshi: 1994. Rural cancer registry at Barshi-report 1988–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Park Y.M. Hepatocellular carcinoma in Asia. In: Sarin S.K., Okuda K., editors. Hepatitis B and C. Carrier to Cancer. Elsevier Sciences; India: 2002. pp. 268–271. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pyrsopoulos N., Reddy R.K. Hepatocellular carcinoma in Asia. In: Sarin S.K., Okuda K., editors. Hepatitis B and C. Carrier to Cancer. Elsevier Sciences; India: 2002. pp. 363–364. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Asim M., Sarma M.P., Kar P. Aetiological and molecular profile of hepatocellular cancer from India. Int J Cancer. 2013 Jul 15;133(2):437–445. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Paul S.B., Chalamalasetty S.B., Vishnubhatla S. Clinical profile, etiology and therapeutic outcome in 324 hepatocellular carcinoma patients at a tertiary care center in India. Oncology. 2009;77:162–171. doi: 10.1159/000231886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kumar R., Saraswat M.K., Sharma B.C., Sakhuja P., Sarin S.K. Characteristics of hepatocellular carcinoma in India: a retrospective analysis of 191 cases. QJM. 2008 Jun;101:479–485. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcn033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kumar M., Kumar R., Hissar S.S. Risk factors analysis for hepatocellular carcinoma in patients with and without cirrhosis: a case-control study of 213 hepatocellular carcinoma patients from India. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22:1104–1111. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2007.04908.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhu A.X. Hepatocellular carcinoma: are we making progress? Cancer Invest. 2003;21:418–428. doi: 10.1081/cnv-120018233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.European Association for the Study of the Liver, European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer EASL-EORTC clinical practice guidelines: management of hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2012;56:908–943. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2011.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Llovet J.M., Brú C., Bruix J. Prognosis of hepatocellular carcinoma: the BCLC staging classification. Semin Liver Dis. 1999;19:329–338. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1007122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cabibbo G., Maida M., Genco C. Natural history of untreatable hepatocellular carcinoma: a retrospective cohort study. World J Hepatol. 2012;27(4):256–261. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v4.i9.256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cabibbo G., Enea M., Attanasio M., Bruix J., Craxì A., Cammà C. A meta-analysis of survival rates of untreated patients in randomized clinical trials of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2010;51:1274–1283. doi: 10.1002/hep.23485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.http://www.who.int/cancer/palliative/definition/en/. Accessed 19.12.12.

- 17.Lin M.H., Wu P.Y., Tsai S.T., Lin C.L., Chen T.W., Hwang S.J. Hospice palliative care for patients with hepatocellular carcinoma in Taiwan. Palliat Med. 2004;18:93–99. doi: 10.1191/0269216304pm851oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zabora J., BrintzenhofeSzoc K., Curbow B., Hooker C., Piantadosi S. The prevalence of psychological distress by cancer site. Psychooncology. 2001;10:19–28. doi: 10.1002/1099-1611(200101/02)10:1<19::aid-pon501>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim H.J., McGuire D.B., Tulman L., Barsevick A.M. Symptom clusters: concept analysis and clinical implications for cancer nursing. Cancer Nurs. 2005;28:270–282. doi: 10.1097/00002820-200507000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ryu E., Kim K., Cho M.S., Kwon I.G., Kim H.S., Fu M.R. Symptom clusters and quality of life in Korean patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Nurs. 2010;33(1):3–10. doi: 10.1097/NCC.0b013e3181b4367e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miaskowski C., Dodd M., Lee K. Symptom clusters: the new frontier in symptom management research. J Natl Cancer Inst Monographs. 2004;32:17–21. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgh023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mercadante S. Abdominal pain. In: Ripamonti C., Bruera E., editors. Gastrointestinal Symptoms in Advanced cancer Patients. Oxford University Press, Inc; New York: 2002. pp. 223–234. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hamilton J, Runyon B, Bonis P, et al. Management of pain in patients with cirrhosis. uptodateonline.com. http://uptodateonline.com/online/content/topic.do?topicKey=cirrhosi/11256&selectedTitle =1∼150&source=search result. Updated May 21, 2009.

- 24.Clària J., Kent J.D., López-Parra M. Effects of celecoxib and naproxen on renal function in nonazotemic patients with cirrhosis and ascites. Hepatology. 2005;41:579–587. doi: 10.1002/hep.20595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Crotty B., Watson K.J., Desmond P.V. Hepatic extraction of morphine is impaired in cirrhosis. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1989;36:501–506. doi: 10.1007/BF00558076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hasselström J., Eriksson S., Persson A. The metabolism and bioavailability of morphine in patients with severe liver cirrhosis. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1990;29:289–297. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1990.tb03638.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mazoit J.X., Sandouk P., Zetlaoui P., Scherrmann J.M. Pharmacokinetics of unchanged morphine in normal and cirrhotic subjects. Anesth Analg. 1987;66:293–298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Klotz U., McHorse T.S., Wilkinson G.R., Schenker S. The effect of cirrhosis on the disposition and elimination of meperidine in man. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1974;16:667–675. doi: 10.1002/cpt1974164667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pond S.M., Tong T., Benowitz N.L. Presystemic metabolism of meperidine to normeperidine in normal and cirrhotic subjects. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1981;30:183–188. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1981.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chandok N., Watt K.D. Pain management in the cirrhotic patient: the clinical challenge. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85:451–458. doi: 10.4065/mcp.2009.0534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tegeder I., Lötsch J., Geisslinger G. Pharmacokinetics of opioids in liver disease. Clin Pharm. 1999;37:17–40. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199937010-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Haberer J.P., Schoeffler P., Couderc E., Duvaldestin P. Fentanyl pharmacokinetics in anaesthetized patients with cirrhosis. Br J Anaesth. 1982;54:1267–1270. doi: 10.1093/bja/54.12.1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Novick D.M., Kreek M.J., Arns P.A. Effect of severe alcoholic liver disease on the disposition of methadone in maintenance patients. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1985;9:349–354. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1985.tb05558.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lewis J.H., Stine J.G. Review article: prescribing medications in patients with cirrhosis – a practical guide. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;37:1132–1156. doi: 10.1111/apt.12324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Benson G.D. Acetaminophen in chronic liver disease. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1983;33:95–101. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1983.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zimmerman H.J., Maddrey W.C. Acetaminophen (paracetamol) hepatotoxicity with regular intake of alcohol: analysis of instances of therapeutic misadventure. Hepatology. 1995;22:767–773. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Paulsen Ø., Aass N., Kaasa S., Dale O. Do corticosteroids provide analgesic effects in cancer patients? A systematic literature review. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2013;46:96–105. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2012.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Koyyalagunta D., Bruera E., Solanki D. A systematic review of randomized trials on the effectiveness of opioids for Cancer pain. Pain Physician. 2012;15:ES39–ES58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ingold J.A., Reed G.B., Kaplan H.S., Bagshaw M.A. Radiation hepatitis. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1965;93:200–208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lawrence T.S., Ten Haken R.K., Kessler M.L. The use of 3-D dose volume analysis to predict radiation hepatitis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1992;23:781–788. doi: 10.1016/0360-3016(92)90651-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jiang W., Zeng Z.C., Zhang J.Y., Fan J., Zeng M.S., Zhou J. Palliative radiation therapy for pulmonary metastases from hepatocellular carcinoma. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2012;29:197–205. doi: 10.1007/s10585-011-9442-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nakashima T., Okuda K., Kojiro M. Pathology of hepatocellular carcinoma in Japan. Cancer. 1983;51:863–877. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19830301)51:5<863::aid-cncr2820510520>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yoon S.M., Kim J.H., Choi E.K. Radioresponse of hepatocellular carcinoma-treatment of lymph node metastasis. Cancer Res Treat. 2004;36:79–84. doi: 10.4143/crt.2004.36.1.79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zeng Z.C., Tang Z.Y., Fan J. Consideration of role of radiotherapy for lymph node metastases in patients with HCC: retrospective analysis for prognostic factors from 125 patients. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;15(63):1067–1076. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.03.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Seong J., Koom W.S., Park H.C. Radiotherapy for painful bone metastases from hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Int. 2005;25:261–265. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2005.01094.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kaizu T., Karasawa K., Tanaka Y. Radiotherapy for osseous metastases from hepatocellular carcinoma: a retrospective study of 57 patients. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:2167–2171. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1998.00614.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.He J., Zeng Z.C., Tang Z.Y. Clinical features and prognostic factors in patients with bone metastases from hepatocellular carcinoma receiving external beam radiotherapy. Cancer. 2009 Jun 15;115:2710–2720. doi: 10.1002/cncr.24300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nakamura N., Igaki H., Yamashita H. A retrospective study of radiotherapy for spinal bone metastases from hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2007;37:38–43. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyl128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kodama H., Aikata H., Uka K. Efficacy of percutaneous cementoplasty for bone metastasis from hepatocellular carcinoma. Oncology. 2007;72(5–6):285–292. doi: 10.1159/000113040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Choi H.J., Cho B.C., Sohn J.H. Brain metastases from hepatocellular carcinoma: prognostic factors and outcome: brain metastasis from HCC. J Neurooncol. 2009;91:307–313. doi: 10.1007/s11060-008-9713-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hsu W.C., Tsai A.C., Chan S.C., Wang P.M., Chung N.N. Mini-nutritional assessment predicts functional status and quality of life of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma in Taiwan. Nutr Cancer. 2012;64:543–549. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2012.675620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pinato D.J., North B.V., Sharma R. A novel, externally validated inflammation-based prognostic algorithm in hepatocellular carcinoma: the prognostic nutritional index (PNI) Br J Cancer. 2012;106:1439–1445. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fan S.T., Lo C.M., Lai E.C., Chu K.M., Liu C.L., Wong J. Perioperative nutritional support in patients undergoing hepatectomy for hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:1547–1552. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199412083312303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.San-in Group of Liver Surgery Long-term oral administration of branched chain amino acids after curative resection of hepatocellular carcinoma: a prospective randomized trial. Br J Surg. 1997;84:1525–1531. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800841109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Meng W.C., Leung K.L., Ho R.L., Leung T.W., Lau W.Y. Prospective randomized control study on the effect of branched-chain amino acids in patients with liver resection for hepatocellular carcinoma. Aust N Z J Surg. 1999;69(11):811–815. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1622.1999.01701.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Poon R.T., Yu W.C., Fan S.T., Wong J. Long-term oral branched chain amino acids in patients undergoing chemoembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma: a randomized trial. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;19(7):779–788. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2004.01920.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kobashi H., Morimoto Y., Ito T. Effects of supplementation with a branched-chain amino acid-enriched preparation on event-free survival and quality of life in cirrhotic patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. A multicenter, randomized controlled trial (Abstract) Gastroenterology. 2006;130:A497. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Takeshita S., Ichikawa T., Nakao K. A snack enriched with oral branched chain amino acids prevents a fall in albumin in patients with liver cirrhosis undergoing chemoembolization for hepatocellular carcinoma. Nutr Res. 2009;29:89–93. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2008.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Koretz R.L., Avenell A., Lipman T.O. Nutritional support for liver disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012 May 16;5:CD008344. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD008344.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ravasco P., Monteiro-Grillo I., Vidal P.M., Camilo M.E. Cancer: disease and nutrition are key determinants of patients’ quality of life. Support Care Cancer. 2004;12:246–252. doi: 10.1007/s00520-003-0568-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ockenga J., Valentini L. Review article: anorexia and cachexia in gastrointestinal cancer. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;22:583–594. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02628.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Del Fabbro E., Dalal S., Bruera E. Symptom control in palliative care–part ii: cachexia/anorexia and fatigue. J Palliat Med. 2006;9:409–421. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.9.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lopez A., Roque Figuls M., Cuchi G. Systematic review of megestrol acetate in the treatment of anorexiacachexia syndrome. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2004;27:360–369. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2003.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Muscaritoli M., Bossola M., Aversa Z., Bellantone R., Rossi Fanelli F. Prevention and treatment of cancer cachexia: new insights into an old problem. Eur J Cancer. 2006;42:31–41. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2005.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ravasco P., Monteiro-Grillo I., Vidal P.M., Camilo M.E. Dietary counseling improves patient outcomes: a prospective, randomized, controlled trial in colorectal cancer patients undergoing radiotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:1431–1438. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mock V. Evidence-based treatment for cancer-related fatigue. J Natl Cancer Inst Monographs. 2004;32:112–118. doi: 10.1093/jncimonographs/lgh025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bruera E., Valero V., Driver L. Patient-controlled methylphenidate for cancer fatigue: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:2073–2078. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.8506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Puetz T.W., Herring M.P. Differential effects of exercise on cancer-related fatigue during and following treatment: a meta-analysis. Am J Prev Med. 2012 Aug;43(2):e1–24. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lichter I. Results of antiemetic management in terminal illness. J Palliat Care. 1993;9:19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Stephenson J., Davies A. An assessment of aetiology-based guidelines for the management of nausea and vomiting in patients with advanced cancer. Support Care Cancer. 2006;14:348–353. doi: 10.1007/s00520-005-0897-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bergasa N.V. Pruritus in chronic liver disease: mechanisms and treatment. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2004 Feb;6(1):10–16. doi: 10.1007/s11894-004-0020-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Tarumi Y., Wilson M.P., Szafran O., Spooner G.R. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of oral docusate in the management of constipation in hospice patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2013;45:2–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2012.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hawley P.H., Byeon J.J. A comparison of sennosides-based bowel protocols with and without docusate in hospitalized patients with cancer. J Palliat Med. 2008;11:575–581. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2007.0178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bruhn J.G. Therapeutic value of hope. Southampt Med J. 1984;77:215–219. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Block S.D. Perspectives on care at the close of life. Psychological considerations, growth, and transcendence at the end of life: the art of the possible. JAMA. 2001;285:2898–2905. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.22.2898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Williams S., Dale J. The effectiveness of treatment for depression/depressive symptoms in adults with cancer: a systematic review. Br J Cancer. 2006;94:372–390. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6602949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]