ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND

Patient decision aids facilitate informed decision making for medical tests and procedures that have uncertain benefits.

OBJECTIVE

To describe participants’ evaluation and utilization of print-based and web-based prostate cancer screening decision aids that were found to improve decisional outcomes in a prior randomized controlled trial.

DESIGN

Men completed brief telephone interviews at baseline, one month, and 13 months post-randomization.

PARTICIPANTS

Participants were primary care patients, 45-70 years old, who received the print-based (N = 628) or web-based decision aid (N = 625) and completed the follow-up assessments.

MAIN MEASURES

We assessed men’s baseline preference for web-based or print-based materials, time spent using the decision aids, comprehension of the overall message, and ratings of the content.

KEY RESULTS

Decision aid use was self-reported by 64.3 % (web) and 81.8 % (print) of participants. Significant predictors of decision aid use were race (white vs. non-white, OR = 2.43, 95 % CI: 1.77, 3.35), higher education (OR = 1.68, 95 % CI: 1.06, 2.70) and trial arm (print vs. web, OR = 2.78, 95 % CI: 2.03, 3.83). Multivariable analyses indicated that web-arm participants were more likely to use the website when they preferred web-based materials (OR: 1.91, CI: 1.17, 3.12), whereas use of the print materials was not significantly impacted by a preference for print-based materials (OR: 0.69, CI: 0.38, 1.25). Comprehension of the decision aid message (i.e., screening is an individual decision) did not significantly differ between arms in adjusted analyses (print: 61.9 % and web: 68.2 %, p = 0.42).

CONCLUSIONS

Decision aid use was independently influenced by race, education, and the decision aid medium, findings consistent with the ‘digital divide.’ These results suggest that when it is not possible to provide this age cohort with their preferred decision aid medium, print materials will be more highly used than web-based materials. Although there are many advantages to web-based decision aids, providing an option for print-based decision aids should be considered.

KEY WORDS: prostate cancer screening, decision aid, informed decision making, shared decision making

INTRODUCTION

Patient decision aids are important tools that can facilitate informed and shared decision making for medical tests and procedures that have uncertain benefits, such as prostate cancer screening.1 Cancer-related organizations, as well as the US Preventive Services Task Force, have encouraged patients to engage in informed and shared decision making with their physician about prostate cancer screening, rather than engage in routine, annual screening.2–4 Men have also expressed a desire for shared decision making for prostate cancer screening5,6 and a need for more information about prostate cancer.7

We recently completed a randomized controlled trial to test the impact of a print-based and a web-based decision aid for prostate cancer screening on behavioral and screening outcomes.8 Users of each decision aid demonstrated better prostate cancer knowledge, less decisional conflict, and more satisfaction with their screening decision than usual care participants. Print and web users differed only on satisfaction with the decision: print users were more likely to be satisfied with their decision than web users. Screening behavior was not impacted by either decision aid at 13 months post-randomization.

In the present paper, we describe men’s assessment of the decision aids and factors that predicted their use and understanding of the tools. Evaluations such as these can help to assess intervention quality,9 understanding of participants’ reception of the intervention,10 and guide future dissemination of the intervention.10 Previous trials of decision aids for prostate cancer screening have reported very favorable participant ratings of decision aid clarity and helpfulness.11–16 Decision aid content was typically rated as neutral (i.e., neither encouraging nor discouraging screening) compared to usual care.11–13,16 Although these studies evaluated patient responses to decision aids, we are aware of no study that has assessed the potential influence of demographic and clinical variables on the likelihood of using and understanding the materials.

We present the results of an in-depth evaluation comparing our print-based and web-based decision aids, including rates of use, patient preference for the decision aid medium, the impact of the decision aids on patient–physician communication, and men’s understanding of the decision aids’ primary message. Due to lower health literacy among older adults, minorities, and less educated adults,17 we expected that age, race, and education would be significant predictors of decision aid use. We also expected that when men’s baseline preference for web versus print materials matched their randomly assigned decision aid, they would be more likely to use the decision aid.

METHODS

Subjects

A detailed description of the subjects and procedures was previously presented.8 Briefly, eligibility criteria included: men 45-70 years old, no history of prostate cancer, English-speaking, ability to provide informed consent, living independently, and having had a primary care outpatient visit within 24 months prior to recruitment. Eligibility was not based on having an upcoming office visit or on having Internet access.

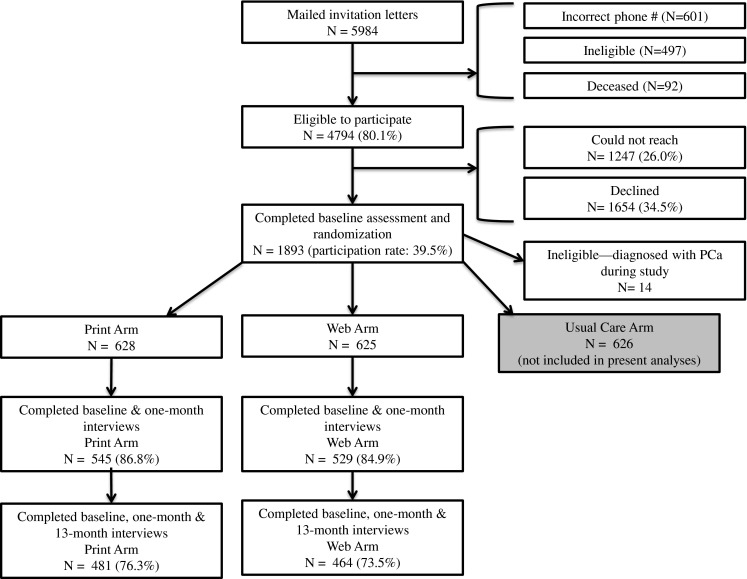

Procedure

This study was approved by the Georgetown/Medstar Oncology Institutional Review Board. We mailed invitation letters to eligible subjects (Fig. 1) and men were subsequently called to confirm eligibility, obtain verbal consent, and to complete the 20-minute baseline telephone interview. At the conclusion of the baseline interview, the interviewer used a computer-generated random allocation sequence to assign participants to the web (N = 625), print (N = 628), or usual care (N = 626) arms. We then mailed participants a written consent form along with either the booklet (print arm) or login information and website URL (web arm). We encouraged men to review the materials prior to the one -month interview. The usual care arm received no decision aid intervention, and therefore will not be described further in this paper. We conducted follow-up telephone assessments at one month and 13 months post-baseline. Data were collected from November 2007 to January 2010.

Figure 1.

Study flowchart.

Description of the Intervention Arms

The two decision aids provided identical content, including facts about the prostate gland and prostate cancer, the benefits and limitations of screening, and the risks and side effects of prostate cancer treatment and monitoring options. The web-based decision aid included six video testimonials that were presented in pairs, one of which focused on the potential benefits of screening and the other on the potential harms of screening. Further, the decision aids encouraged shared decision making with physicians and included a values clarification tool (a ten-item scale on which men identified their preferences about screening). On the web-based decision aid, the questions comprising the values clarification tool appeared at intervals throughout the website and a summary of the responses were presented on a subsequent page. In the print-based decision aid, the values clarification tool was a worksheet that asked all ten questions on one page at the end of the booklet. More information about the decision aids is available.18,19

Measures

Descriptive Variables

We assessed demographics (age, race, education level, employment, income, whether men had a regular physician, insurance, and numeracy20) and clinical characteristics (comorbidities, personal history of cancer, family history of prostate cancer, prostate cancer screening history in one’s lifetime and in the year prior to trial enrollment), and recollection of a prior discussion of prostate cancer screening with a physician.

Decision Aid Evaluation Variables

At baseline, telephone interviewers assessed men’s preference for print-based versus web-based health information, and Internet access and use. We used a series of questions to assess patients’ evaluation of decision aids from our prior work assessing other decision aids16,18 and incorporated other studies’ prostate cancer screening decision aid evaluations.11,12 At the one-month interview, we assessed self-reported use of the materials, ratings of the content, patient–physician communication about the materials, and reasons for not using the materials (see Kassan et al. for web use based on electronic tracking data19). At the 13-month interview, we assessed men’s self-reported use of the materials and patient–physician communication since the one-month follow-up. We created a 3-level variable indicating the agreement between baseline preference for print-based versus web-based materials and randomization arm: 1) baseline preference matched randomization assignment, 2) baseline preference did not match randomization assignment, and 3) those with no baseline preference for either web-based or print-based materials.

Data Analyses

We conducted chi-square tests and ANOVAs to assess for group differences on demographics, clinical characteristics, Internet access, and decision aid evaluation variables. These analyses included participants who completed both the baseline and one-month assessments. Assessment of the 13-month evaluation variables included participants who completed all three assessments. Next, we determined the significant covariates (demographic and clinical characteristics) to include in the logistic regression models, which were age, race, education, screening history prior to enrollment in the trial, and frequency of Internet use. Finally, we conducted logistic regression models to determine the significant predictors of 1) understanding the overall message of the decision aids and 2) decision aid use, separately for web and print arms.

RESULTS

Descriptive Information

Figure 1 presents the study flow chart, the participation rate, and the sample size at each assessment. In Table 1, we present participants’ demographic and clinical characteristics for all participants who completed both the baseline and one-month assessments, stratified by users and non-users within each arm. Compared to non-users, decision aid users in both arms were significantly more likely to be white, highly educated, employed, to have a higher income, and to have answered both numeracy questions correctly. Men who did not use the decision aid in the web arm reported significantly more comorbidities, and users of the website were significantly more likely to have been screened and to have discussed prostate cancer screening with their physician.

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics, by Users and Nonusers of the Decision Aids*

| Print Arm (N = 545) | Web Arm (N = 529) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Users (N = 446) | Nonusers (N = 99) | P value | Users (N = 340) | Nonusers (N = 189) | P value | |

| Age Mean (SD) | 56.8 (6.7) | 56.3 (6.7) | 0.48 | 57.14 (6.9) | 57.4 (6.7) | 0.65 |

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | |||

| Age | 0.47 | 0.66 | ||||

| 45–49 | 73 (16.4) | 21 (21.2) | 55 (16.2) | 25 (13.2) | ||

| 50–59 | 215 (48.2) | 43 (43.4) | 148 (43.5) | 86 (45.5) | ||

| 60–70 | 158 (35.4) | 35 (35.4) | 137 (40.3) | 78 (41.3) | ||

| Race†‡ | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||||

| White | 283 (63.5) | 37 (37.4) | 242 (71.4) | 74 (39.2) | ||

| African-American | 144 (32.3) | 59 (59.6) | 88 (26.0) | 110 (58.2) | ||

| Other | 19 (4.3) | 3 (3.0) | 9 (2.7) | 5 (2.6) | ||

| Site | 0.34 | < 0.001 | ||||

| Georgetown Univ. Hospital | 188 (42.2) | 34 (34.3) | 159 (46.8) | 67 (35.4) | ||

| Washington Hospital Center | 55 (12.3) | 15 (15.2) | 20 (5.9) | 37 (19.6) | ||

| MedStar Physician Partners | 203 (45.5) | 50 (50.5) | 161 (47.4) | 85 (45.0) | ||

| Education‡ | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||||

| High school or less | 78 (17.6) | 39 (39.4) | 47 (13.8) | 59 (31.6) | ||

| Some college or college degree | 194 (43.8) | 40 (40.4) | 134 (39.4) | 77 (41.2) | ||

| Graduate work or degree | 171 (38.6) | 20 (20.2) | 159 (46.8) | 51 (27.3) | ||

| Numeracy‡ | 0.01 | 0.04 | ||||

| Both items incorrect | 88 (20.0) | 19 (19.6) | 54 (16.1) | 40 (21.5) | ||

| One item correct | 127 (28.8) | 42 (43.3) | 89 (26.6) | 61 (32.8) | ||

| Both items correct | 226 (51.2) | 36 (37.1) | 192 (57.3) | 85 (45.7) | ||

| Marital status‡ | 0.18 | 0.001 | ||||

| Married | 305 (68.5) | 61 (61.6) | 256 (75.3) | 116 (61.7) | ||

| Employment status | 0.001 | < 0.001 | ||||

| Employed full-time/part-time | 320 (71.7) | 62 (62.6) | 254 (74.7) | 113 (59.8) | ||

| Not Employed | 40 (9.0) | 22 (22.2) | 20 (5.9) | 37 (19.6) | ||

| Retired | 86 (19.3) | 15 (15.2) | 66 (19.4) | 39 (20.6) | ||

| Income | 0.003 | < 0.001 | ||||

| ≤ 75 k | 133 (34.0) | 44 (53.0) | 91 (29.1) | 82 (52.6) | ||

| 75 k–150 k | 143 (36.6) | 26 (31.3) | 109 (34.8) | 41 (26.3) | ||

| >150 k | 115 (29.4) | 13 (15.7) | 113 (36.1) | 33 (21.2) | ||

| Refused | 55 | 16 | 27 | 33 | ||

| Regular physician | 0.51 | 0.11 | ||||

| Yes | 426 (95.5) | 93 (93.9) | 326 (95.9) | 175 (92.6) | ||

| Health insurance | 0.21 | 0.40 | ||||

| Yes | 439 (98.4) | 99 (100.0) | 336 (98.8) | 185 (97.9) | ||

| Comorbidities‡ (excluding cancer) | 0.20 | 0.02 | ||||

| 0 | 159 (35.8) | 27 (27.3) | 126 (37.1) | 55 (29.3) | ||

| 1 | 141 (31.8) | 32 (32.3) | 110 (32.4) | 53 (28.2) | ||

| ≥ 2 | 144 (32.4) | 40 (40.4) | 104 (30.6) | 80 (42.6) | ||

| Personal cancer history‡ | 0.07 | 0.21 | ||||

| Yes | 49 (11.0) | 5 (5.1) | 55 (16.2) | 23 (12.2) | ||

| Family history of PCa | 0.30 | 0.18 | ||||

| Yes | 79 (18.8) | 22(23.2) | 88 (26.7) | 39 (21.3) | ||

| Don’t Know/Missing | 25 | 4 | 11 | 6 | ||

| Ever screened (prior to RCT enrollment)‡ | 0.006 | 0.001 | ||||

| Yes | 389 (87.4) | 75 (76.5) | 320 (94.1) | 160 (85.1) | ||

| Screened in past 12 months (prior to RCT enrollment)‡ | 0.44 | 0.001 | ||||

| Yes | 269 (60.3) | 55 (56.1) | 240 (71.2) | 105 (55.6) | ||

| Discussion with physician about PCa screening (prior to RCT enrollment)‡ | 0.12 | 0.04 | ||||

| Yes | 330 (74.0) | 65 (66.3) | 262 (77.1) | 130 (68.8) | ||

*Demographics and clinical characteristics have been limited to participants who have completed both the baseline and one-month assessments

†For all other analyses, African-American and other races were collapsed into one ‘non-white’ category. The users and nonusers in both categories still differed significantly (both p’s < 0.001)

‡ The N value does not add up to the total due to missing data

PCa prostate cancer; RCT randomized controlled trial

Baseline Education Preferences and Web Access

At baseline, there was an overall preference for receiving a print-based decision aid (51.7 %) over a web-based decision aid (36.6 %; p <0.001). However, there were no significant group differences regarding preferences for web-or print-based health education materials at baseline) (p = 0.79; Table 2). The majority (90.8 %) had Internet access, and of those, almost all (94.7 %) had a high-speed connection and 70.3 % used the Internet daily. Importantly, there were no significant differences between web and print arms on web access variables (assessed at baseline). Most Internet users (96 %) reported that they used the Internet to obtain health-related information at least a few times a year. Of the 99 men without Internet access, 59.2 % were willing to access the website if assigned to the web arm (e.g., at a friend’s house).

Table 2.

Baseline Education Preferences and Web Access

| Print (n = 545) | Web (n = 529) | All (N =1,074) | P value | |

| Health-Related Information Delivery Preference* | ||||

| Internet | 194 (35.9) | 197 (37.4) | 391 (36.6) | 0.79 |

| Booklet | 285 (52.8) | 267 (50.7) | 552 (51.7) | |

| No Preference | 61 (11.3) | 63 (12.0) | 124 (11.6) | |

| Internet Access | ||||

| No | 55 (10.1) | 44 (8.3) | 99 (9.2) | 0.32 |

| Yes | 490 (89.9) | 485 (91.7) | 975 (90.8) | |

| High Speed Access (N = 975) | ||||

| No | 21 (4.3) | 17 (3.5) | 38 (3.9) | 0.82 |

| Yes | 462 (94.3) | 461 (95.1) | 923 (94.7) | |

| Don’t Know | 7 (1.4) | 7 (1.4) | 14 (1.4) | |

| Use of Internet* | ||||

| Never/Almost never | 75 (13.8) | 71 (13.4) | 146 (13.6) | 0.09 |

| A few times a year | 20 (3.7) | 6 (1.1) | 26 (2.4) | |

| A few times a month | 21 (3.9) | 19 (3.6) | 40 (3.7) | |

| A few times a week | 57 (10.5) | 50 (9.5) | 107 (10.0) | |

| Daily | 371 (68.2) | 383 (72.4) | 754 (70.3) | |

| For those who use the Internet at least a few times a year: | Print (n = 469) | Web (n = 458) | All (N = 927) | |

| Use Internet to obtain health-related Info? | ||||

| Never | 66 (14.1) | 57 (12.4) | 123 (13.3) | 0.81 |

| A few times a year | 234 (49.9) | 224 (48.9) | 458 (49.4) | |

| A few times month | 112 (23.9) | 119 (26.0) | 231 (24.9) | |

| A few times a week | 57 (12.2) | 58 (12.7) | 115 (12.4) | |

| For Those Without Internet Access: | Print (n = 55) | Web (n = 44) | All (N = 99) | |

| If assigned to Web, willing to access website?* | ||||

| No | 17 (30.9) | 16 (37.2) | 33 (33.7) | 0.55 |

| Yes | 35 (63.6) | 23 (53.5) | 58 (59.2) | |

| Unsure | 3 (5.5) | 4 (9.3) | 7 (7.1) |

* The N value does not add up to the total due to missing data

Decision Aid Evaluation Variables

Use of the Booklet and Website

Table 3 presents men’s self-reported use and evaluation of the materials. Almost three-quarters of the overall sample used the decision aids. At both the 1-month and 13-month follow-up assessments, print arm participants were significantly more likely to have read the print-based decision aid, compared to the web arm participants who used the web-based decision aid. Print users self-reported spending a median of 30.0 minutes (range: 5.0–480.0) reviewing the materials, while web users self-reported visiting the website for a median of 40.0 minutes (range: 3.0–240.0; p < 0.05). Approximately two-thirds of users indicated that they read the materials in their entirety (67.0 %). Web users were almost twice as likely to report that they completed the values clarification tool compared to print users (85.6 % vs. 45.2 %; p < 0.001) and that the length of the decision aid was too long (35.2 % vs. 18.1 %; p < 0.001).

Table 3.

Decision Aid Utilization and Evaluation

| Print (n = 545) | Web (n = 529) | All (N = 1,074) | P value | |

| Did you have an opportunity to read the Booklet/Website, since receiving the materials: | ||||

| At the one-month assessment? % Yes | 446 (81.8) | 340 (64.3) | 786 (73.2) | < 0.001 |

| Did you have an opportunity to read the Booklet/Website, since the one-month assessment? | (n = 481) | (n = 464) | (n = 945)† | |

| At the 13-month assessment: % Yes | 237 (49.3) | 127 (27.4) | 364 (38.5) | < 0.001 |

| For those who read the materials prior to the one month assessment: | Print (n = 446) | Web (n = 340) | All (N = 786) | P value |

| Use of Booklet and Website | ||||

| How much time did you spend reading the Booklet/Website? (self-reported; in minutes)§ Median (Range)* | 30.0 (5.0–480.0) | 40.0 (3.0–240.0) | 30.0 (3.0–480.0) | 0.01 |

| How many pages did you read/view? | ||||

| A few pages | 14 (3.1) | 12 (3.5) | 26 (3.3) | 0.14 |

| Some pages | 43 (9.6) | 21 (6.2) | 64 (8.1) | |

| Most pages | 103 (23.1) | 66 (19.4) | 169 (21.5) | |

| All pages | 286 (64.1) | 241 (70.9) | 527 (67.0) | |

| How many times did you read the Booklet/view the Website?§ | ||||

| Once | 280 (62.9) | 214 (62.9) | 494 (62.9) | 1.00 |

| More than once | 165 (37.1) | 126 (37.1) | 291 (37.1) | |

| Did you fill out the values clarification tool? | ||||

| Yes | 201 (45.2) | 291 (85.6) | 492 (62.7) | < 0.001 |

| Missing/Did not recall | 56 | 16 | 72 | |

| How would you rate the length of the Booklet/Website?§ | ||||

| Much/a little too short | 9 (2.0) | 11 (3.3) | 20 (2.6) | < 0.001 |

| Just right | 353 (79.9) | 203 (61.5) | 556 (72.0) | |

| Much/a little too long | 80 (18.1) | 116 (35.2) | 196 (25.4) | |

| Ratings of Decision Aid Content | ||||

| Did you have any trouble reading or understanding the Booklet/Website?§ | ||||

| Yes | 13 (2.9) | 11 (3.2) | 24 (3.1) | 0.80 |

| How helpful was the information for understanding the pros/cons of PCa screening? | ||||

| Not at all helpful | 12 (2.7) | 7 (2.1) | 19 (2.4) | 0.69 |

| Somewhat helpful | 86 (19.3) | 57 (16.8) | 143 (18.2) | |

| Very helpful | 224 (50.2) | 183 (53.8) | 407 (51.8) | |

| Extremely helpful | 124 (27.8) | 93 (27.4) | 217 (27.6) | |

| Do you think the overall message of the Booklet/Website suggested…§ | ||||

| Men should get screened | 157 (35.6) | 87 (25.9) | 244 (31.4) | 0.002 |

| Men should not get screened | 11 (2.5) | 20 (6.0) | 31 (4.0) | |

| Neither screening or not screening | 273 (61.9) | 229 (68.2) | 502 (64.6) | |

| Did the Booklet/Website make you nervous/fearful about PCa screening? | ||||

| Yes | 47 (10.5) | 34 (10.0) | 81 (10.3) | 0.81 |

| Do you think the Booklet/Website influenced your decision about whether to be screened or not for PCa?§ | ||||

| Not at all | 246 (55.5) | 195 (57.7) | 441 (56.5) | 0.25 |

| A little/somewhat | 96 (21.7) | 82 (24.3) | 178 (22.8) | |

| Very much/quite a bit | 101 (22.8) | 61 (18.0) | 162 (20.7) | |

| Patient–Physician Communication | ||||

| Did the Booklet/Website make you think of new questions to ask your physician? (% Yes) | 218 (48.9) | 169 (49.7) | 387 (49.2) | 0.82 |

| When would you prefer to receive an educational Booklet/Website…§ | ||||

| After PCP appointment | 36 (8.6) | 34 (10.2) | 70 (9.3) | 0.00 |

| During PCP appointment | 42 (10.0) | 12 (3.6) | 54 (7.2) | |

| Before PCP appointment | 340 (81.3) | 287 (86.2) | 627 (83.5) | |

| Prefer not to receive materials | 19 | 5 | 24 | |

| Did you discuss your thoughts/concerns about PCa screening with your physician, since receiving the materials? | ||||

| At one month: % Yes | 27 (6.1) | 20 (5.9) | 47 (6.0) | 0.92 |

| Did you discuss your thoughts/concerns about PCa screening with your physician, since the one-month assessment? | (n = 456) | (n = 442) | (n = 898)‡ | |

| At 13 months: % Yes | 196 (43.0) | 211 (47.8) | 407 (45.4) | 0.14 |

| For non-users of the Decision Aids: | Print (n = 99) | Web (n = 189) | All (N = 288) | P value |

| Reason for not reading/viewing materials (Check all that apply):§ | ||||

| Did not have time (% yes) | 62 (62.6) | 96 (51.3) | 158 (55.2) | 0.07 |

| No interest (% yes) | 20 (20.2) | 19 (10.2) | 39 (13.6) | 0.02 |

| Did not receive materials (% yes) | 10 (10.1) | 11 (5.9) | 21 (7.3) | 0.19 |

| Trouble accessing internet (% yes–Web only) | — | 73 (39.0) | 73 (39.0) | — |

| Other (% yes) | 15 (15.2) | 1 (0.5) | 16 (5.6) | — |

| Can you think of anything that would have made it more likely to have read/viewed the materials?§ (% Yes) | 42 (44.7) | 81 (44.8) | 123 (44.7) | 0.99 |

| For those who said yes above: What would have made it more likely? | ||||

| Having more time prior to the interview (Yes) | 27 (64.3) | 43 (53.1) | 70 (56.9) | 0.23 |

| Shorter materials (Yes) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (4.9) | 4 (3.3) | 0.14 |

| Other (Yes) | 15 (35.7) | 35 (43.2) | 50 (40.7) | 0.42 |

*Due to the skewed distribution of time spent on the website, we compared median times spent on the website with the Kruskal-Wallis test

* Participants who answered this question completed all three assessments (baseline, one month, and 13 months)

* Participants who answered this question completed all three assessments (baseline, one month, and 13 months) and also self-reported using a decision aid

* The N value does not add up to the total due to missing data

PCa prostate cancer; PCP primary care physician

Decision Aid Content

Very few participants reported having problems understanding the materials or that the decision aid made them nervous/fearful about screening (Table 3). The majority (79 %) considered the materials very or extremely helpful in understanding the pros and cons of screening, and over 40 % of men in each arm said that the decision aid was influential in their screening decision. Importantly, almost 65 % of the entire sample understood that screening is an individual decision and that the information in the materials was not making a recommendation either for or against screening, with the web arm users more likely to understand this message than print arm users (68.2 % vs. 61.9 %; p < 0.01). However, in a logistic regression analysis controlling for race, education, and frequency of Internet use, we found no group differences regarding comprehension of this message (OR = 0.87, 95 % CI: 0.63, 1.21).

Patient–Physician Communication

In each arm, about one-half of men said that the decision aid raised new questions to ask their physician (Table 3). Over 80 % in each arm indicated they would prefer to receive decision aid materials prior to a physician’s visit, with web users significantly more likely than print users to prefer pre-visit materials (p < 0.001). At one month, 94 % said they had not discussed their thoughts and concerns regarding prostate cancer screening with their physician since reading the materials; this was likely due to men not having had a primary care appointment between review of the decision aid and the one-month interview. However, at 13 months, over 40 % in each arm reported discussing prostate cancer screening with their physician.

Non-Users of the Decision Aids

At the one-month assessment, 288 (26.8 %) men reported that they did not use their assigned decision aid (print arm: n = 99, web arm: n = 189; Table 3). The most frequently cited reasons were lack of time and lack of interest, and for web participants, lack of Internet access.

Predictors of Decision Aid Use at the One-Month Follow-up

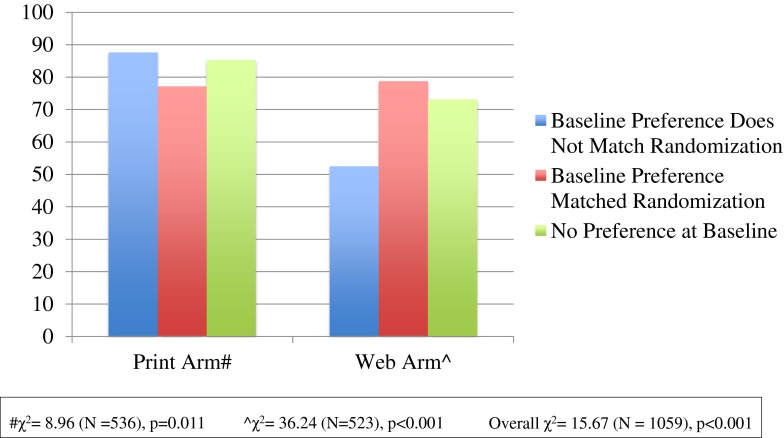

In unadjusted analyses, we assessed whether men’s baseline preference for web-based vs. print-based materials impacted decision aid use (Fig. 2). Use of the website was significantly lower among those who did not receive their preferred medium (52.3 %), compared to those who did receive their preferred medium (78.6 %) or had no preference (73.0 %; p < 0.001; Fig. 2). However, use of the print materials was higher among those who did not receive their preferred medium (87.5 %), compared to those who did receive their preferred medium (77.0 %) or had no preference at baseline (85.2 %; p = 0.01; Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Impact of receiving one’s preferred decision aid medium on decision aid use (N = 1059).

Logistic regression analyses revealed several significant predictors of decision aid use at the one-month assessment (Table 4). Among print arm participants, decision aid use was more likely among white compared to non-white men (OR: 2.13, CI: 1.28, 3.54) and among men with graduate-level education compared to high school or less (OR: 2.37, CI: 1.12, 5.00). Contrary to the unadjusted analyses presented above, having a baseline preference for print materials did not significantly impact decision aid use (Table 4). Among the web arm participants, decision aid use was less likely among men aged 60-70 years compared to those aged 45-49 years (OR: 0.50, CI: 0.25, 0.99), and more likely among white compared to non-white men (OR: 2.94, CI: 1.91, 4.54), men previously screened for prostate cancer prior to enrollment in the trial (OR: 2.82, CI: 1.35, 5.87), and daily Internet users (OR: 3.20, CI: 1.87, 5.49). Confirming the unadjusted analyses presented above, men were almost twice as likely to use the website when the website was their preferred medium (OR = 1.91, CI: 1.17, 3.12; Table 4). When removing web arm participants who reported not having Internet access at any location (n = 44), men were still more likely to use the website when the website was their preferred medium (OR = 1.77, CI: 1.08, 2.90).

Table 4.

Logistic Regression Models of Decision Aid Use for Print and Web Arm Participants (N = 1,059)

| Predictors of decision aid use among Print arm participants (ref = did not use decision aid) (N = 536) | ||||

| Odds Ratio | 95 % Confidence Interval | P value | ||

| Age (ref = 45–49) | ||||

| 50–59 | 1.42 | 0.75 | 2.67 | 0.28 |

| 60–70 | 1.04 | 0.51 | 2.10 | 0.92 |

| Race (ref = non-white) | ||||

| White | 2.13 | 1.28 | 3.54 | 0.00 |

| Education (ref = high school or less) | ||||

| College degree | 1.65 | 0.90 | 3.00 | 0.37 |

| Graduate work or degree | 2.37 | 1.12 | 5.00 | 0.02 |

| Employment (ref = part-time or full-time) | ||||

| Not employed | 0.86 | 0.42 | 1.79 | 0.69 |

| Retired | 1.61 | 0.80 | 3.24 | 0.18 |

| Ever screened for PCa (ref = not screened) | ||||

| Screened | 1.32 | 0.69 | 2.56 | 0.40 |

| Internet Use (ref = never–1/week) | ||||

| Daily | 1.02 | 0.55 | 1.90 | 0.95 |

| Randomization Arm Matches Baseline Preference (ref = no match) | ||||

| Match | 0.69 | 0.38 | 1.25 | 0.22 |

| No Preference at Baseline | 0.79 | 0.34 | 1.87 | 0.60 |

| Predictors of decision aid use among Web arm participants (ref = did not use decision aid) (N = 523) | ||||

| Age (ref = 45–49) | ||||

| 50–59 | 0.54 | 0.29 | 1.02 | 0.06 |

| 60–70 | 0.50 | 0.25 | 0.99 | 0.05 |

| Race (ref = non-white) | ||||

| White | 2.94 | 1.91 | 4.54 | <.001 |

| Education (ref = high school or less) | ||||

| College degree | 0.93 | 0.52 | 1.67 | 0.81 |

| Graduate work or degree | 1.02 | 0.53 | 1.95 | 0.96 |

| Employment (ref = part-time or full-time) | ||||

| Not employed | 0.52 | 0.26 | 1.05 | 0.07 |

| Retired | 1.20 | 0.68 | 2.13 | 0.53 |

| Ever screened for PCa (ref = not screened) | ||||

| Screened | 2.82 | 1.35 | 5.87 | 0.01 |

| Internet Use (ref = never-1/week) | ||||

| Daily | 3.20 | 1.87 | 5.49 | < 0.001 |

| Randomization Arm Matches Baseline Preference (ref = no match) | ||||

| Match | 1.91 | 1.17 | 3.12 | 0.01 |

| No Preference at Baseline | 1.30 | 0.66 | 2.59 | 0.45 |

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

These analyses revealed several notable findings with regard to men’s evaluation and utilization of print-based and web-based prostate cancer screening decision aids. First, almost 75 % of participants utilized a decision aid, which is notable given that the decision aids were not delivered in conjunction with a physician visit. Second, 65 % of the sample understood that the materials were not recommending either for or against screening, which is an increase in understanding from previous decision aid studies.12,14,16 Third, men were significantly more likely to use the print-based compared to the web-based decision aid. However, we also found evidence that use of the decision aid was impacted by receiving one’s preferred decision aid medium: in multivariable models, use of the web-based decision aid was significantly greater among those who preferred web-based materials, while use of the print-based decision aid was not associated with a preference for print materials. Fourth, we found evidence of the digital divide, as race and education were independently associated with use of the print-based decision aid, and age, race, and frequency of internet use were independently associated with use of the web-based decision aid in multivariable analyses. Thus, the medium through which information is delivered, patient preferences for the medium, and patient characteristics are all important factors to consider when delivering tools for helping patients to make an informed medical decision.

To maximize use of decision aids, these results suggest the importance of understanding the target audience’s preference for different media. It also appears that there is still an important role for print-based decision aids: men who did not receive their preferred medium used the print decision aid at a much higher rate than they used the web-based decision aid. Further, there was an overall preference (51.7 %) for print-based materials when asked at baseline, despite the fact that over 90 % of participants had Internet access and over 70 % of the men who had Internet access used the Internet daily. When it is not feasible to offer more than one type of decision aid, our results suggest that print-based decision aids may reach a greater proportion of participants. However, we found that the digital divide variables of race and education impacted the use of the print materials, indicating that efforts are still needed to address these factors that have long hampered health education and informed decision making. In particular, white men were over twice as likely to use either decision aid compared to non-white men, corroborating previous findings suggesting that African-American and other non-white men may be somewhat reluctant to engage in medical decision making.21,22 This finding also reinforces the need for physicians and other clinicians to engage in culturally relevant shared decision making.

Similar to prior studies, participants rated the decision aids favorably for clarity and helpfulness. While participants in the print arm reported that the decision aid was a better length than participants in the web arm, we found few differences between the print and web arms.15 For example, men in each arm had a similar response to the patient–physician communication outcomes and to the decision aid content, with few people reporting difficulty understanding the information and most reporting that the decision aids were very or extremely helpful. In multivariable, adjusted analyses, men were equally likely to understand that the overall message of the decision aid was neutral with regard to screening. However, there were a few important differences, in that men in the web arm were significantly more likely to: 1) use the values clarification tool, 2) spend more time using the decision aid (as well as think it was too long), and 3) prefer to receive the decision aid prior to their primary care appointment. This information can help guide informed and shared decision making by providing decision aids prior to the physician appointment, a suggestion echoed by a recently convened multi-disciplinary panel on improving shared decision making in prostate cancer screening.23 Additionally, efforts to increase men’s use of the values clarification tool in the print arm may benefit from the integration of values clarification questions throughout the decision aid, rather than as a single worksheet. Men in the web arm used the values clarification tool at higher rates than men in the print arm, likely because values clarification questions appeared throughout the website and were summarized at the end, while in the print arm, questions were presented on a single worksheet at the end of the booklet.

The primary study limitation was the necessary reliance on participants’ self-reported use of the decision aids. In the web arm, we compared the self-report data with the results from the tracking software and found some overestimation of decision aid use,19 suggesting the possibility that both arms may have overestimated their use of the decision tools. However, we are unaware of any reason to expect that the degree of overestimation would differ between groups. Another study limitation was the overall participation rate of 39.5 %. However, this rate is typical of decision aid studies that enrolled participants by mail and telephone as opposed to in conjunction with an office visit,11,15 and has the advantage of yielding a sample that is potentially more generalizable, as participants had fewer eligibility restrictions.

In summary, we found that decision aid use was greater in the print arm, but that use was impacted by receiving the decision aid in one’s preferred medium. Variables associated with the digital divide were predictive of use of both the print and the web-based decision aids. With a recent survey of primary care physicians reporting that 80 % routinely discuss prostate cancer screening with their patients,24 it is important to assist patients and physicians in their efforts to engage in informed and shared decision making. These results suggest that delivery of tools for informed decision making should include an assessment of patient preferences for the decision tool medium, and as well as a continued focus on patient characteristics that may limit their use.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the participants who volunteered their time to participate in this study and to thank Susan Marx for her administrative support. Sources of funding include the National Cancer Institute (R01 CA119168-01) and Department of Defense (PC051100) to KLT. Additional support was provided by the Lombardi Comprehensive Cancer Center (LCCC) Biostatistics and Bioinformatics Shared Resource and the LCCC Cancer Center Support Grant. Results from this manuscript will be presented at the 35th Annual Meeting of the Society of Behavioral Medicine, Philadelphia, PA.

Conflicts of Interest

None of the authors have any conflicts of interest or financial disclosures to report.

REFERENCES

- 1.Stacey D, Bennett CL, Barry MJ, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2011;CD001431. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Carter HB, Albertsen PC, Barry MJ, et al. Early detection of prostate cancer: AUA guideline. J Urol. 2013;190:419–26. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2013.04.119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith RA, Brooks D, Cokkinides V, Saslow D, Brawley OW. Cancer screening in the United States, 2013: a review of current American Cancer Society guidelines, current issues in cancer screening, and new guidance on cervical cancer screening and lung cancer screening. CA Cancer J Clin. 2013;63:88–105. doi: 10.3322/caac.21174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.U.S.Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for prostate cancer. Clinical summary of U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation. 2012. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/prostatecancerscreening/prostatefinalsum.pdf. Accessed July 22, 2014.

- 5.Feldman-Stewart D, Brennenstuhl S, Brundage MD. The information needed by Canadian early-stage prostate cancer patients for decision-making: stable over a decade. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;73:437–42. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ilic D, Risbridger GP, Green S. The informed man: attitudes and information needs on prostate cancer screening. J Mens Health Gend. 2005;2:414–20. doi: 10.1016/j.jmhg.2005.10.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Woolf SH, Krist AH, Johnson RE, Stenborg PS. Unwanted control: how patients in the primary care setting decide about screening for prostate cancer. Patient Educ Couns. 2005;56:116–24. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2003.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Taylor KL, Williams RM, Davis K, et al. Decision making in prostate cancer screening using decision aids vs usual care: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Int Med. 2013;173:1704–12. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.9253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Linnan L, Steckler A, editors. Process Evaluations for Public Health Interventions and Research. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oakley A, Strange V, Bonell C, Allen E, Stephenson J. Process evaluation in randomised controlled trials of complex interventions. BMJ. 2006;332:413–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.332.7538.413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Frosch DL, Kaplan RM, Felitti VJ. A randomized controlled trial comparing internet and video to facilitate patient education for men considering the prostate specific antigen test. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18:781–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.20911.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gattellari M, Ward JE. A community-based randomised controlled trial of three different educational resources for men about prostate cancer screening. Patient Educ Couns. 2005;57:168–82. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2004.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lepore SJ, Wolf RL, Basch CE, et al. Informed decision making about prostate cancer testing in predominantly immigrant black men: a randomized controlled trial. Ann Behav Med. 2012;44:320–30. doi: 10.1007/s12160-012-9392-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Taylor KL, Davis JL, III, Turner RO, et al. Educating African American men about the prostate cancer screening dilemma: a randomized intervention. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2006;15:2179–88. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Volk RJ, Jibaja-Weiss ML, Hawley ST, et al. Entertainment education for prostate cancer screening: a randomized trial among primary care patients with low health literacy. Patient Educ Couns. 2008;73:482–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2008.07.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Williams RM, Davis KM, Luta G, et al. Fostering informed decisions: a randomized controlled trial assessing the impact of a decision aid among men registered to undergo mass screening for prostate cancer. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;91:329–36. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2012.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kutner M, Greenberg E, Jin Y, Paulsen C. The Health Literacy of America's Adults: Results From the 2003 National Assessment of Adult Literacy (NCES 2006-483). Available at: http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED493284.pdf. Accessed July 22, 2014. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, National Center for Education Statistics; 2006.

- 18.Dorfman CS, Williams RM, Kassan EC, et al. The development of a web- and a print-based decision aid for prostate cancer screening. BMC Med Inf Decis Making. 2010;10:12. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-10-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kassan EC, Williams RM, Kelly SP, et al. Men's use of an Internet-based decision aid for prostate cancer screening. J Health Commun. 2012;17:677–97. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2011.579688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lipkus IM, Samsa G, Rimer BK. General performance on a numeracy scale among highly educated samples. Med Decis Making. 2001;21:37–44. doi: 10.1177/0272989X0102100105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Levinson W, Kao A, Kuby A, Thisted RA. Not all patients want to participate in decision making. A national study of public preferences. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20:531–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.04101.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murray E, Pollack L, White M, Lo B. Clinical decision-making: Patients' preferences and experiences. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;65:189–96. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2006.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilkes M, Srinivasan M, Cole G, Tardif R, Richardson LC, Plescia M. Discussing uncertainty and risk in primary care: recommendations of a multi-disciplinary panel regarding communication around prostate cancer screening. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28:1410–9. doi: 10.1007/s11606-013-2419-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hall IJ, Taylor YJ, Ross LE, Richardson LC, Richards TB, Rim SH. Discussions about prostate cancer screening between U.S. primary care physicians and their patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26:1098–104. doi: 10.1007/s11606-011-1682-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]