Abstract

Background and objectives

Graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) is associated with kidney injury after hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT). Because plasma elafin levels correlate with skin GVHD, this study examined urinary elafin as a potential marker of renal inflammation and injury.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

Urine was collected prospectively on 205 patients undergoing their first HCT from 2003 to 2010. Collections were done at baseline, weekly through day 100, and monthly through year 1 to measure elafin and urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio (ACR). Associations between urinary elafin levels and microalbuminuria, macroalbuminuria, AKI and CKD, and mortality were examined using Cox proportional hazards or linear regression models. Available kidney biopsy specimens were processed for immunohistochemistry.

Results

Mean urinary elafin levels to day 100 were higher in patients with micro- or macroalbuminuria (adjusted mean difference, 529 pg/ml; P=0.03) at day 100 than in those with a normal ACR (adjusted mean difference, 1295 pg/ml; P<0.001). Mean urinary elafin levels were higher in patients with AKI compared with patients without AKI (adjusted mean difference, 558 pg/ml; P<0.01). The average urinary elafin levels within the first 100 days after HCT were higher in patients who developed CKD at 1 year than in patients without CKD (adjusted mean difference, 894 pg/ml; P=0.002). Among allogeneic recipients, a higher proportion of patients with micro- or macroalbuminuria at day 100 also had grade II-IV acute GVHD (80% and 86%, respectively) compared with patients with a normal ACR (58%; global P<0.01). Each increase in elafin of 500 pg/ml resulted in a 10% increase in risk of persistent macroalbuminuria (hazard ratio, 1.10; 95% confidence interval [95% CI], 1.06 to 1.13; P<0.001) and a 7% increase in the risk of overall mortality (95% CI, 1.02 to 1.13, P<0.01). Renal biopsy specimens from a separate cohort of HCT survivors demonstrated elafin staining in distal and collecting duct tubules.

Conclusion

Higher urinary elafin levels are associated with an increased risk of micro- and macroalbuminuria, AKI and CKD, and death after HCT.

Keywords: chronic kidney disease, hematopoietic cell transplant, microalbuminuria, proteinuria, renal tubular epithelial cells

Introduction

Hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) is frequently complicated by AKI and CKD characterized by albuminuria and proteinuria; however, little is known about pathophysiology. After HCT, kidneys are exposed to systemic inflammation, caused first by conditioning regimens and then by acute and chronic graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), risk factors for post-transplant CKD and thrombotic microangiopathy (1–3). Donor T cells, systemic inflammation, and vascular endothelial injury are key aspects of tissue disease in GVHD (4,5). The paradigm of tissue damage from conditioning therapy and radiation leading to release of inflammatory cytokines and activation of antigen-presenting cells and cytotoxic T lymphocytes resulting in further epithelial damage is thought to be the basis for acute GVHD (6).

Given the association with both acute and chronic GVHD and CKD, we sought to determine whether the renal injury after HCT is secondary to the ongoing inflammatory milieu through use of elafin, a previously identified serum marker of GVHD.

Plasma elafin levels are 4-fold higher in patients with skin GVHD, and higher levels (≥6000 pg/ml) are associated with an almost 2-fold increased risk of death (7). Elafin is a low-molecular-weight inhibitor of neutrophil elastase and proteinase-3, produced by epithelial cells and macrophages in response to infiltration by inflammatory cells, release of proteolytic enzymes, and disruption of epithelial integrity (8). We hypothesized that urinary elafin levels would correlate with micro- and macroalbuminuria, as well as development of AKI and CKD.

Materials and Methods

Patient Selection

Patients older than age 2 years undergoing their first HCT during 2003–2010 were prospectively studied if they (1) had a baseline serum creatinine that was normal for age in children, ≤1.3 mg/dl in women, and ≤1.5 mg/dl in men; (2) were not currently taking angiotensin receptor blockers or angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors; (3) had no history of diabetes; and (4) consented to a protocol approved by the institutional review board of Seattle Children's Hospital and the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center.

HCT Technique

Patients received a conditioning regimen followed by donor hematopoietic cells on day 0. Myeloablative regimens were cyclophosphamide-based (with total-body irradiation or targeted busulfan) for allogeneic transplants; autologous graft recipients received several different regimens. Reduced-intensity conditioning regimens consisted of fludarabine and total-body irradiation, 2–4 Gy (9). The kidneys were not shielded. Allograft recipients received prophylaxis against GVHD with immunosuppressive drugs, usually cyclosporine or tacrolimus plus methotrexate or mycophenolate mofetil (10). Prophylaxis against infections included acyclovir, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, oral fluconazole or itraconazole, and preemptive ganciclovir for cytomegalovirus viremia (11–15). Prophylactic oral ursodiol was given routinely.

Specimen Collection and Analytical Methods

Urine samples were collected (at baseline, then weekly through day 100, and then monthly through the first year after HCT) between 8–10 a.m., iced, and frozen (−80°C) until analysis. Elafin was quantitated in urine using a Luminex 200 instrument to determine the fluorescence intensity of each microbead. A standard curve was created using recombinant elafin standards (R&D Systems). Sample concentrations were calculated using Luminex xPonent software. The intra- and interassay coefficients of variation are ≤10%.

Urinary albumin was determined using an immunoturbidimetric assay with a Cobas c 11 analyzer in untreated urine samples. Urine creatinine was measured on a Roche/Hitachi modular automated clinical chemistry analyzer using an enzymatic method.

Renal Immunohistochemistry

Renal tissue was not available from any of the 205 prospectively studied patients. Under an institutional review board–approved protocol, we identified 26 separate patients who had renal biopsies after HCT (24 with GVHD) and 12 non-HCT patients who underwent biopsy for different indications, including eight allograft kidneys (five sampled at time of allograft reperfusion) and one each of minimal-change nephrotic syndrome; pauci-immune GN with tubulointerstitial inflammation, drug-induced tubulointerstitial nephritis; and uninvolved kidney adjacent to nephroblastoma. These cases were specifically identified to include clinical and pathologic conditions analogous to those seen in the post-HCT setting: proteinuria, drug exposure, and tubulointerstitial nephritis and “normal” (donor kidney at the time of reperfusion and peritumor kidney). Immunohistochemistry of renal tissue for elafin was performed at room temperature using the Dako Autostainer (Carpentaria, CA), anti-P13/Elafin antibody (1:200) (HPA017737; Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), and Mach 2 anti-rabbit horseradish peroxidase–labeled polymer (RHRP520L; Biocare Medical, Concord, CA), visualized with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (Dako) and hematoxylin counterstaining. Concentration-matched isotype control slides were run for each tissue sample (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA). Staining for elafin was scored blindly by one author as negative or positive, with semiquantitative grading of positive biopsy specimens reflecting the extent of tubules showing reaction product as follows: 1+, scattered tubules; 2+, <10%; 3+, 10%–25%, 4+, 25%–50%, 5+, >50%.

Clinical Parameters in HCT Recipients

Clinical data included age, sex, race/ethnicity, indication for HCT, preparative regimen, and conditioning regimen components. Each patient’s BP, medications, and temperature were recorded on the morning of sample collection. Hypertension was defined as BP>140/90 mmHg in adults; >95th percentile for BP based on age, sex, and height in children; or use of antihypertensive medications. History of diabetes, insulin use, myocardial infarction, angina, and congestive heart failure was noted. Acute GVHD was graded as 0–1 and 2–4 (16). AKI was defined as an elevation of 0.3 mg/dl in serum creatinine in 48 hours and/or an increase in serum creatinine of 1.5 times within 7 days from a previous serum creatinine during the first 60 days after HCT. CKD was defined as an eGFR<60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (based on the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease equation in adults and the Schwartz formula in children) and a change in baseline GFR of 10 ml/min per 1.73 m2 at 1 year after HCT. Five patients with a GFR<60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 at enrollment were excluded from analyses involving CKD. The degree of albuminuria was expressed as a urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio (ACR) on a spot urine sample. Normal ACR was <30 mg/g creatinine, microalbuminuria was 30–299 mg/g creatinine, and macroalbuminuria was ≥300 mg/g creatinine.

Statistical Analyses

The associations between urinary elafin levels and AKI, elevated ACR (micro- or macroalbuminuria), and CKD at 1 year were examined. The adjustment variables in each model, chosen a priori, included donor (autologous versus allogeneic), severity of disease (low versus intermediate versus high), patient age at HCT, conditioning intensity (myeloablative versus nonablative), baseline GFR, baseline creatinine, baseline ACR, presence of diabetes, and hypertension (17). For all models that compared mean elafin levels, the arithmetic average of all elafin values up to the appropriate point in time was calculated for each patient, and the means of these averages were compared between the groups in question. Linear regression was used to examine the association between urinary elafin levels and CKD by comparing mean elafin levels through day 100 among those with and without CKD at 1 year in patients who survived and had a GFR measurement at 1 year. In this analysis, mean elafin was used as the dependent variable, with CKD status as an independent variable along with those listed above. The association between AKI and mean elafin was assessed in a similar manner. Among patients who developed AKI, the mean elafin value up to time of AKI was calculated, and among patients without AKI, mean urinary elafin levels through day 60 were used.

Linear regression was also used to assess the association between mean urinary elafin levels and ACR value at day 100, with day 100 ACR categorized as normal, microalbuminuria, or macroalbuminuria. Mean elafin was used as the dependent variable, and the day 100 ACR grouping was an independent variable along with adjustment variables listed above. The day-100 ACR value was taken to be the value on the day closest to day 100 within 80–120 days after HCT, and elafin levels up to this point were used. Persistent macroalbuminuria was defined as the second of two consecutive ACR measurements ≥300 mg/g creatinine in the first 100 days, and this was modeled as a time-to-event endpoint. The association of urinary elafin with persistent macroalbuminuria was assessed with Cox regression, with elafin modeled as both a linear and nonlinear time-dependent covariate. The nonlinear modeling was done through use of a cubic spline with knots at the 5th, 25th, 50th, 75th, and 95th percentiles of all post-HCT elafin values. The association of urinary elafin with the hazards of overall and nonrelapse mortality were assessed in the same way, adjusting for the variables listed above.

Results

Figure 1 demonstrates patient enrollment. Demographic data did not differ between enrollees and those who declined participation. Data for the 205 patients are presented in Table 1. The mean baseline urinary elafin (±SD) was 1902±3754 pg/ml (median, 1260 pg/ml; range, 30–48,273 pg/ml). The median number of post-HCT urinary elafin measurements per patient was 6 (range, 1–19). The mean urinary elafin value among 1512 post-HCT measurements was 1976±1814 pg/ml (median, 1440 pg/ml; range, 3.6–20,179 pg/ml).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of patient enrollment into study protocol.

Table 1.

Patient demographic data and clinical characteristics

| Patient Characteristic | Value |

|---|---|

| Age at transplantation | |

| <20 yr | 26 (13) |

| 20–39 yr | 40 (20) |

| 40–59 yr | 88 (43) |

| ≥60 yr | 51 (25) |

| Median age (range) (yr) | 49.7 (2.2–74.3) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 78 (38) |

| Male | 127 (62) |

| Race | |

| African American | 6 (3) |

| White | 153 (75) |

| Hispanic | 10 (5) |

| Other | 25 (12) |

| Not available | 11(5) |

| Diagnosis | |

| ANL | 63 (31) |

| MDS | 35 (17) |

| CML | 16 (8) |

| NHL | 19 (9) |

| ALL | 20 (10) |

| MM | 13 (6) |

| CLL | 10 (5) |

| AA | 9 (4) |

| Other | 20 (10) |

| Donor type | |

| Allogeneic | 65 (32) |

| Autologous | 37 (18) |

| Unrelated donor | 103 (50) |

| Conditioning regimen | |

| Reduced-intensity regimens (200 cGy) | 36 (18) |

| Myeloablative: CY/TBI 12–13.5 cGy | 15 (7) |

| Myeloablative: BU, CY only | 47 (23) |

| Other myeloablative regimens | 107 (52) |

| Median baseline serum creatinine (range) (mg/dl) | 0.85 (0.20–1.60) |

| Median baseline eGFR (range) (ml/min per 1.73 m2) | 92.93 (66.9–187.5) |

| Median baseline ACR (range) (mg/g) | 7.8 (0.90–1953) |

| Patient CMV serostatus | |

| Positive | 110 (53) |

| Negative | 95 (46) |

| Missing | 1 (<1) |

| Source of stem cells | |

| Bone marrow | 39 (19) |

| PBSC | 148 (72) |

| Cord | 19 (9) |

Unless otherwise noted, values are the number (percentage) of patients. ANL, acute nonlymphocytic leukemia: MDS, myleodysplastic syndrome; CML, chronic myelogenous leukemia; NHL, non-Hodgkin lymphoma; ALL, acute lymphocytic leukemia; MM, multiple myeloma; CLL, chronic lymphocytic leukemia; AA, aplastic anemia; CY, cyclophosphamide; TBI, total-body irradiation; BU, busulfan; ACR, albumin-to-creatinine ratio; CMV, cytomegalovirus; PBSC, peripheral blood stem cell.

Association between Urinary Elafin Levels and ACR

Mean urinary elafin levels through day 100 were statistically significantly different among patients with no albuminuria, microalbuminuria, and macroalbuminuria at day 100 (mean of the average urinary elafin values, 1615, 2168, and 2829 pg/ml, respectively) (Table 2). As the degree of albuminuria increased, mean urinary elafin increased (P<0.001, trend test). These results were qualitatively the same after adjustment for donor, conditioning, baseline GFR, and baseline ACR, and there was no suggestion of an interaction between ACR group and any of these variables. The mean adjusted differences were 529 pg/ml (567 pg/ml unadjusted difference) between normal albuminuria and microalbuminuria (P=0.03) and 1295 pg/ml (1214 pg/ml unadjusted difference) between normal and macroalbuminuria (P<0.001). The correlation coefficient between urinary albumin level and urinary elafin level was R=0.01; when the data were log-transformed, the correlation coefficient was R=0.15.

Table 2.

Summary of average urinary elafin levels (pg/ml) through day-100 albumin-to-creatinine ratio assessment according to day-100 urinary albumin-to-creatinine ratio group

| Day-100 ACR Group | Mean | Median | P Valuea | Trend P Valueb |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| <30 mg/g (n=88) | 1615 | 1287 | — | <0.001 |

| 30–299 mg/g (n=48) | 2168 | 1946 | 0.02 (0.03) | |

| ≥300 mg/g (n=23) | 2829 | 2680 | <0.001 (0.0006) |

P values from linear regression, compared with normal ACR; P values adjusted for baseline GFR, baseline ACR, donor, and conditioning listed in parentheses.

P value from trend test, treating increasing ACR groups as integer values of 1, 2, and 3.

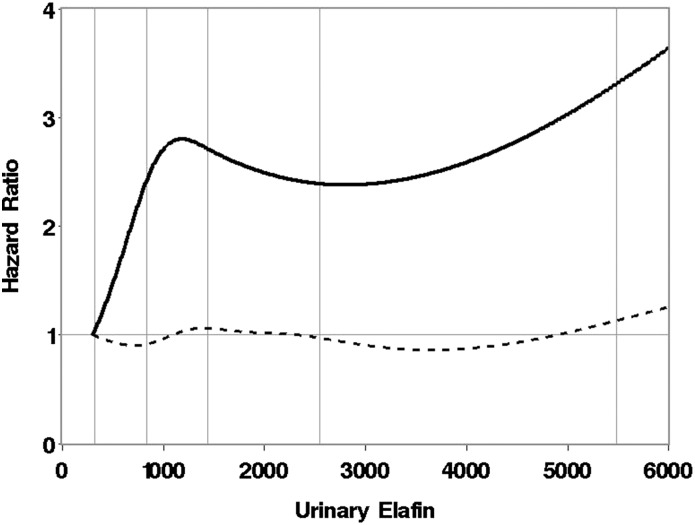

The median time to development of persistent macroalbuminuria (n=33) was 51 days (range, 7–113 days). Increasing urinary elafin was associated with an increased risk of persistent macroalbuminuria, with urinary elafin modeled as a continuous linear time-dependent variable. Each increase in urinary elafin of 500 pg/ml resulted in a 10% increase in risk of persistent macroalbuminuria (hazard ratio, 1.10; 95% confidence interval [95% CI, 1.06 to 1.13; P=0.002)] after adjustment for donor, patient age, baseline GFR, and baseline ACR. The association between elafin and persistent macroalbuminuria is depicted in Figure 2, with urinary elafin modeled as a nonlinear function. This model suggests a minimal effect of elafin level on the risk of persistent macroalbuminuria until urinary elafin reaches roughly 2000 pg/ml, above which the risk of macroalbuminuria steadily increases with increasing urinary elafin levels.

Figure 2.

Risk of persistent macroalbuminuria as a function of urinary elafin level in pg/ml, where elafin is modeled as a cubic spline as described in the Materials and Methods. The vertical lines represent the 5th, 25th, 50th, 75th, and 95th percentiles of elafin values after hematopoietic cell transplantation. Dotted line represents the pointwise 95% lower confidence limit of the hazard ratio. Hazard ratios depicted in the curve are relative to a reference urinary elafin level of 300 pg/ml.

Association between Urinary Elafin and Kidney Injury

AKI developed in 150 of 205 (73%) patients at a median of 11 (range, −10 to 59) days. At least one urinary elafin value was measured after HCT and before onset of AKI in 65 patients. The mean urinary elafin level before and up to the development of AKI was higher in patients with AKI (n=65) (mean, 2266 pg/ml) than in patients without AKI (n=55) (mean, 1599 pg/ml) (P<0.01). After adjustment for donor conditioning, baseline ACR, baseline creatinine, and baseline GFR, the adjusted mean difference between patients with and without AKI decreased from 666 pg/ml to 612 pg/ml (P=0.03). There was no suggestion of an interaction between AKI and any of these factors.

The mean urinary elafin level through day 100 GFR assessment was 2672 pg/ml in patients who had a GFR<60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 and 1878 pg/ml in those with a GFR≥60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (P=0.002) (Table 3). After adjustment for donor conditioning and baseline GFR, the mean difference in elafin values was 819 pg/ml (P=0.003). One hundred thirty-nine patients survived to 1 year, and 113 of these survivors (81%) had a serum creatinine measured at 1 year. The average urinary elafin levels from baseline to 100 days after HCT were 2458 pg/ml in patients who developed CKD at 1 year compared with 1534 pg/ml in patients who did not develop CKD (P<0.001) (Table 3). After adjustment for donor, conditioning, and baseline GFR, this mean difference was 894 pg/ml (P=0.002). There was no suggestion of an interaction between mean elafin level and the adjustment variables or presence of AKI. Analyses were also done using urinary elafin to urinary creatinine ratios, and the results were qualitatively the same (data not shown).

Table 3.

Summary of average urinary elafin levels according to day-100 and 1-year GFR values

| Variable | Patients (n) | Urinary Elafin Level (pg/ml) | P Valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Median | |||

| Day-100 GFR | ||||

| <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 | 40 | 2672 | 2220 | 0.002 (0.003) |

| ≥60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 | 141 | 1878 | 1513 | |

| One-year GFRb | ||||

| <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 | 24 | 2458 | 2125 | <0.001 (0.002) |

| ≥60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 | 89 | 1534 | 1273 | |

P value from two-sample t test; P values adjusted for baseline GFR, donor, and conditioning listed in parentheses.

Among patients who survived to 1 year after hematopoeitc stem cell transplantation.

Association between GVHD and AKI and Macroalbuminuria

Among allogeneic recipients, grade 2–4 GVHD had developed in 58% of patients with a day-100 ACR<30, 80% of patients with an ACR between 30 and 299 at day 100, and 86% of patients with a day-100 ACR>300 (P<0.01; chi-squared test). After adjustment for conditioning, age, and baseline GFR, the global P value for the ACR groups was <0.01. Eighty-one percent of patients with grade 2–4 GVHD developed AKI compared with 62% of patients with grade 0–1 GVHD (P=0.003; chi-squared test). However, after adjustment for the preceding factors, the association between AKI and GVHD was no longer significant (P=0.41 and 0.36).

The mean elafin level up to day 100 among allogeneic patients with grade 0–1 acute GVHD was 1690 pg/ml compared with 2779 pg/ml up to the time of onset of acute GVHD among those with grade 2–4 acute GVHD. After adjustment for baseline GFR and intensity of conditioning, the adjusted mean difference between those with and without GVHD was 1023 pg/ml (P=0.002).

Association between Urinary Elafin Levels and Mortality

Each increase in urinary elafin of 500 pg/ml before day 100 resulted in a 7% increase in the risk of overall mortality (95% CI, 1.02 to 1.13; P<0.01) and a 9% increase in the risk of nonrelapse mortality (95% CI, 1.03 to 1.17; P<0.01) when elafin was modeled as a time-dependent continuous linear function and adjusted for donor, conditioning, age, disease severity, and baseline GFR. With elafin modeled as a time-dependent nonlinear function (using a cubic spline), its adjusted association with the risk of overall mortality is summarized in Figure 3. The association between elafin (as a continuous linear time-dependent covariate) and both overall and nonrelapse mortality appeared to be similar among autologous versus allogeneic transplant recipients (P=0.64 and 0.65, respectively, interaction test).

Figure 3.

Risk of overall mortality as a function of urinary elafin level in pg/ml, where urinary elafin is modeled as a cubic spline as described in the Materials and Methods. The vertical lines represent the 5th, 25th, 50th, 75th, and 95th percentiles of elafin values after hematopoietic cell transplantation. Dotted line represents the pointwise 95% upper and lower confidence limit of the hazard ratio. Hazard ratios depicted in the curve are relative to a reference urinary elafin level of 300 pg/ml.

Renal Histology and Immunohistochemistry in HCT Cases and Non-HCT Biopsy Specimens

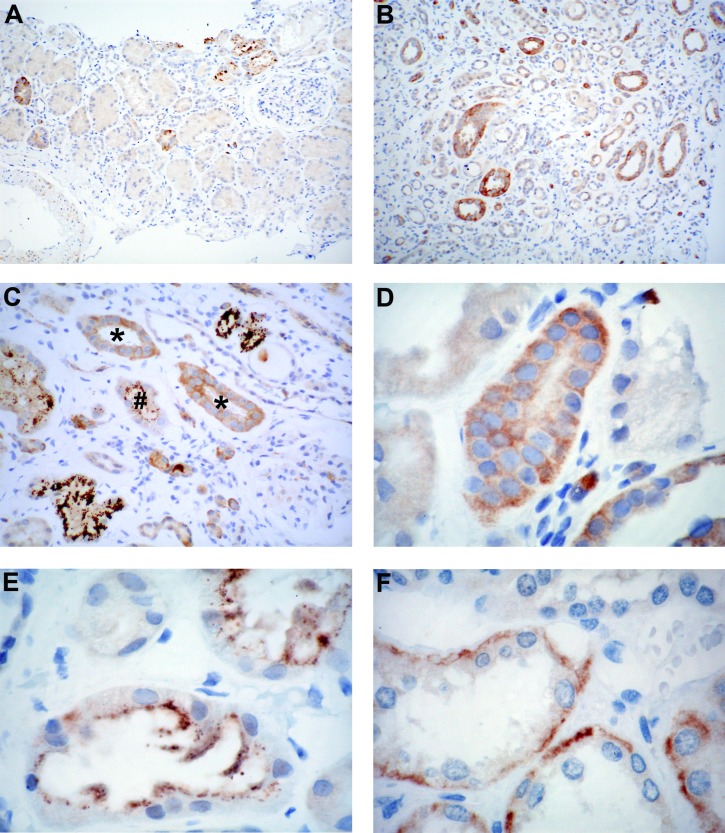

Microalbuminuria or macroalbuminuria at the time of biopsy had been documented in 20 of 26 HCT recipients. Pathologic diagnoses included thrombotic microangiopathy in 10 patients (38%), acute or chronic interstitial nephritis in six (23%), and acute tubular necrosis in 11 (42%) (some biopsy specimens reflected multiple diagnoses). Renal biopsy specimens from HCT recipients with microalbuminuria or macroalbuminuria and elevated creatinine at the time of biopsy demonstrate granular cytoplasmic elafin staining in the distal and collecting tubules (Figure 4, A and B) in 24 of 26 samples (10 of 13 pediatric; 13 of 13 adult), the majority showing 1+ to 2+ diffuse, finely granular cytoplasmic staining within tubular epithelial cells (Figure 4, C and D, Table 4). Some cases (one pediatric and 8 adult) also had 1+ to 4+ coarsely granular cytoplasmic staining that was diffuse or more commonly at the luminal edge (Figure 4, C and E). The latter was more evident in the setting of nearby inflammation and active tubular injury. There was no staining in proximal tubules, recognized by their tall epithelium and basal nuclei, glomeruli, or interstitium (Figure 4A). Samples from non-HCT patients with a renal disorder mostly showed 1+ to 2+ finely granular diffuse cytoplasmic elafin staining within tubular epithelial cells; in five control samples there was also luminal staining. Coarsely granular cytoplasmic staining (1+ to 3+) was coincident in three controls (minimal-change disease, pauci-immune GN, and transplant allograft biopsy) and the sole pattern in the case of tubulointerstitial nephritis. The 2+ finely granular staining in the kidney adjacent to the nephroblastoma was entirely basal in its distribution within the cytoplasm of tubular epithelium (Figure 4F).

Figure 4.

Elafin staining in hematopoietic cell transplantation and control kidney samples. (A and B) Low-power image from case 20 demonstrating the absence of staining in proximal tubules, which are identified by their tall epithelium and basally situated nuclei. Staining of the distal segment is noted in the cortex and medulla, where many profiles of the thin segment of the loop of Henle are clearly evident (3,3′-diaminobenzidine; original magnification, ×100). (C) Intermediate-power image from case 21 shows positive staining in a subset of tubules and negative glomerulus (arrowhead). This case demonstrated several patterns, including diffuse finely (*) and coarsely (upper right and lower left) granular as well as coarse luminal granules (#) (3,3′-diaminobenzidine; original magnification, ×200). (D) Finely granular cytoplasmic staining was most commonly diffusely distributed within the cytoplasm (case 15), whereas coarse granules (E) typically accumulated toward the lumen aspect (case 15) (3,3′-diaminobenzidine; original magnification, ×400). (F) Staining for elafin was rarely restricted to the basal aspect of tubular cells (case 27) (3,3′-diaminobenzidine; original magnification, ×400).

Table 4.

Clinical and pathologic diagnosis of renal biopsy cases and controls and elafin staining

| Patient | Sex | Age at HCT (yr) | Time since HCT at Biospy (d) | Baseline SCr (mg/dl) | SCr at Day 100 after (mg/dl) | ACR at Biopsy (±3 m) (mg/g) | SCr at Time of Biopsy (mg/dl) | Site of Acute GVHD | Site of Chronic GVHD | Biopsy Diagnosis | Elafin Negative | B,D,L Cyto ine Granular Elafin | B,D,L Cyto Coarse Granular Elafin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cases | |||||||||||||

| 1 | F | 14 | 558 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 1510 | 0.6 | None | Skin | TMA | X | ||

| 2 | F | 6 | 303 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 1570 | 0.7 | Skin, gut | Skin | TMA | 1D | ||

| 3 | F | 16 | 100 | 0.7 | 0.9 | 997 | 0.9 | Skin, gut | Skin, gut | ATN | X | ||

| 4 | M | 13 | 165 | 0.7 | 0.5 | 342 | 0.7 | Skin, gut | Gut, oral | TMA | 1 D | ||

| 5 | F | 20 | 1414 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 66 | 1 | Skin, gut | Gut | BK | 1 D | ||

| 6 | F | 9 | 341 | 0.7 | 0.8 | 13.9 | 0.8 | Skin, gut | Gut | CIN | 3 D | ||

| 7 | F | 13 | 76 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 108 | NA | Liver | Oral | CIN, TMA | 2 D | ||

| 8 | M | 14 | 77 | 0.0.5 | 1.1 | Mild proteinuria | 2 | Gut, skin | None | ATN | 2 D | 1 D | |

| 9 | F | 11 | 135 | 0.4 | 0.7 | 374 | 0.9 | Skin | Gut, eye | TMA, AIN | 4 D | ||

| 10 | M | 11 | 677 | 0.5 | 0.6 | 238.6 | 1.9 | Skin, oral | Skin, gut | BK, AIN | 2 D | ||

| 11 | M | 3 | 134 | 0.5 | 0.2 | 103 | 0.5 | Skin | Skin, gut | TMA, ATN | 1 D | ||

| 12 | M | 6 | 1127 | 0.4 | 0.3 | 54 | 2.3 | Gut | Gut | BK | X | ||

| 13 | F | 2 | 83 | 0.5 | 0.4 | 1510 | 0.6 | None | Skin | AIN | 3 D | ||

| 14 | F | 53 | 162 | 0.7 | 2 | 2983.9 | 4.5 | Gut, skin | None | GN, AIN | 2 D | ||

| 15 | F | 44 | 5719 | 0.8 | 1.2 | 1.3 | Skin | None | Rejection, CNI toxicity | 1 D | 4 L | ||

| 16 | M | 63 | 1377 | 0.8 | 1.2 | 112.7 | NA | Gut, skin | Oral, skin, liver | ATN, TBMd | 2 D | 2 L | |

| 17 | F | 52 | 61 | 0.82 | 1.6 | 646.2 | 1.89 | Skin | Gut | TMA, ATN | 1 D | 1 D | |

| 18 | M | 32 | 2817 | 0.8 | 1.9 | 2.3 | Skin | Gut | FGS | 2 D | 1 L | ||

| 19 | M | 32 | 1723 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 7.8 g/ 24 hr | 6.4 | NA | None | TMA, ATN | 4 D | 1 L | |

| 20 | M | 57 | 449 | 0.7 | 1.5 | 28.1 | NA | Skin, gut | Skin, liver | ATN | 2 D | 1 D | |

| 21 | M | 49 | 2362 | 1 | 1 | 3.3 | Nnone | Oral, eye, gut | ATN | 3 D | 4 D, 4 L | ||

| 22 | M | 56 | 399 | 0.9 | 1.4 | 275.2 | 1.6 | Skin | Skin, oral | TMA | 1 D, 1 L | ||

| 23 | M | 70 | 276 | 0.7 | 1 | NA | 2.88 | None | Gut | ATN | 1 D, 1 L | ||

| 24 | M | 56 | 95 | 0.99 | 2.17 | 1.356 g/24hr (9/17/2011, before treatment) | 1.78 | Gut | None, died | ATN | 1 D | ||

| 25 | M | 51 | 1375 | 0.7 | 155.7 | 2.96 | None | None | ATN | 1 D | |||

| 26 | F | 49 | 234 | 0.94 | 1.46 | 332.9 | 2.71 | Gut | None | TMA | 2 D | ||

| Controls | |||||||||||||

| 27 | M | 6 | NL-WT | 2 B | |||||||||

| 28 | M | 13 | TIN-d | 1 D | |||||||||

| 29 | M | 6 | MCNS | 1 D | 1 L | ||||||||

| 30 | F | 10 | PI | 1 D | 3 L | ||||||||

| 31 | TxKa | 2 L | |||||||||||

| 32 | TxKb | 2 D | |||||||||||

| 33 | TxKc | 2 D | 1 D | ||||||||||

| 34 | TxK-0 | 1 D, 4 L | |||||||||||

| 35 | TxK-0 | 1 D | |||||||||||

| 36 | TxK-0 | X | |||||||||||

| 37 | TxK-0 | 1 D, 3 L | |||||||||||

| 38 | TxK-0 | 1 D |

F, female; M, male; HCT, hematopoietic cell transplantation; SCr, serum creatinine; NA, not available; GVHD, graft-versus-host disease; TMA, thrombotic microangiopathy; ATN, acute tubular necrosis; BK, polyoma BK nephropathy; CIN, chronic interstitial nephritis; AIN, acute interstitial nephritis; CNI, calcineurin inhibitor; TBMd, tubular basement membrane deposits; NL-WT, uninvolved kidney near Wilms tumor; TIN-d, drug-induced tubulointerstitial nephritis; MCNS, minimal-change nephrotic syndrome; PI, pauci-iummune GN; TxK, allograft kidney (a, acute T cell–mediated rejection, grade 1A, Banff; b, acute T cell–mediated rejection, grade 1A, and severe interstitial fibrosis and tubular atrophy; no pathologic diagnosis at surveillance); TxK-0, allograft kidney-time 0; cyto, cytoplasmic; D, diffuse; B, basal; L, luminal.

Discussion

Increased levels of urinary elafin were associated with microalbuminuria and persistent macroalbuminuria in the first 100 days after HCT. Elevated urinary elafin levels in the first 100 days were also associated with development of CKD at 1 year after transplant. In addition, higher urinary elafin levels were associated with development of AKI within the first 60 days after HCT. Both overall and nonrelapse mortality were associated with increased urinary elafin levels. We demonstrate the presence of elafin in distal segments of kidneys from HCT patients with renal dysfunction. The staining of distal segments and not glomeruli or proximal tubules leads us to speculate that urinary elafin reflects a local response to injury rather than filtration or excretion by the kidney of circulating elafin. Elafin is produced by epithelial cells in response to inflammation and tissue injury (8,18) and after induction by TNF-α and IL1-β in human airway epithelial cells and keratinocytes (19). Both of these cytokines have been implicated in inflammatory renal disease, such as crescentic GN and CKD (20,21), as well as in acute GVHD (22).

Renal biopsy specimens from our HCT patients revealed thrombotic microangiopathy, acute and chronic interstitial nephritis, and acute tubular necrosis. A histologic diagnosis of kidney GVHD is not typically made because formal pathologic criteria have not yet been established. Recent data postulate that vascular endothelium is a target of GVHD and that diffuse alveolar hemorrhage and thrombotic microangiopathy are manifestations of endothelial acute GVHD (23). Although liver involvement with GVHD is well recognized, renal involvement is not; however, a mouse model of GVHD showed similar expression profiles in liver and kidney of pathways involved with antigen processing and inflammation with CD3+ T cells and expression of vascular cell adhesion molecule and intracellular adhesion molecule, reflecting endothelial injury (24). Our working hypothesis suggests that kidney injury results from inflammatory mediators and cytokines, with tubular and endothelial injury resulting from the systemic inflammatory milieu of GVHD or direct injury mediated by T cells and cytokines. A final common pathway to injury may involve inflammatory mediators, tubular damage, and endothelial damage, ultimately leading to CKD. Our data suggest that urinary elafin predicts renal injury and progression to CKD in the HCT population and may reflect a local epithelial cell response to these events. Thus, urinary elafin may be a useful biomarker of tubular injury in the kidney as well as a marker of progression, a hypothesis to be tested in other settings in which the inflammatory milieu plays an inciting role.

We are unaware of prior studies of elafin in the kidney. However, the expression of molecules similar to elafin (whey acidic protein motifs and secretory leukocyte protease inhibitor) has been demonstrated in renal tissue (25,26). Early acute rejection of renal grafts has been linked to elevated urinary α-1 protease inhibitor, a marker of persistent inflammation of the renal parenchyma (23). Infusions of elafin in animal models of cardiac injury decrease myocyte death, inflammatory damage, and scar formation and preserve cardiac function (19, 27). Randomized trials of elafin infusions are underway in patients on cardiopulmonary bypass and those undergoing renal transplant to decrease cardiac injury and mitigate renal ischemia-reperfusion injury, respectively (8).

A limitation of the current study is an inability to determine whether elafin is produced in the kidney in response to injury or whether it is simply filtered and reabsorbed. We were unable to assess mRNA expression of elafin in the biopsy specimens. We measured simultaneously collected plasma and urinary elafin levels in a subset of patients and found a weak correlation (R=0.32), consistent with our renal production hypothesis. Additional prospective studies that include simultaneous blood and urine collection and renal biopsy specimens from HCT recipients are needed to further delineate whether elafin is locally produced in response to injury in this patient population. We did not investigate other identified markers of tubular injury such as NGAL and KIM-1 which might help to clarify the role of elafin in HCT patients.

We propose that urinary elafin is a marker of ongoing renal inflammation and tubulointerstitial injury, triggered by the inflammatory milieu of acute and chronic GVHD. Ongoing inflammation contributes to the progression of renal injury and ultimate development of CKD. Early identification of patients most at risk for CKD after HCT may provide an opportunity to intervene meaningfully to mitigate long-term renal disease.

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the Experimental Histopathology Shared Resource at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center for their preparation of the slides and performance of immunohistochemistry for elafin.

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disease), award no. 1R01-DK080860-01 (Chronic kidney disease in survivors of hematopoietic cell transplant) received by S.H. Research funding was provided by the National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, grants DK080860, CA018029, and CA015704. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health nor its subsidiary Institutes and Centers.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

References

- 1.Hingorani S, Guthrie KA, Schoch G, Weiss NS, McDonald GB: Chronic kidney disease in long-term survivors of hematopoietic cell transplant. Bone Marrow Transplant 39: 223–229, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Changsirikulchai S, Myerson D, Guthrie KA, McDonald GB, Alpers CE, Hingorani SR: Renal thrombotic microangiopathy after hematopoietic cell transplant: Role of GVHD in pathogenesis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 4: 345–353, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Malone FR, Leisenring WM, Storer BE, Lawler R, Stern JM, Aker SN, Bouvier ME, Martin PJ, Batchelder AL, Schoch HG, McDonald GB: Prolonged anorexia and elevated plasma cytokine levels following myeloablative allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant. Bone Marrow Transplant 40: 765–772, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Luft T, Dietrich S, Falk C, Conzelmann M, Hess M, Benner A, Neumann F, Isermann B, Hegenbart U, Ho AD, Dreger P: Steroid-refractory GVHD: T-cell attack within a vulnerable endothelial system. Blood 118: 1685–1692, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tichelli A, Gratwohl A: Vascular endothelium as ‘novel’ target of graft-versus-host disease. Best Pract Res Clin Haematol 21: 139–148, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li JM, Giver CR, Lu Y, Hossain MS, Akhtari M, Waller EK: Separating graft-versus-leukemia from graft-versus-host disease in allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Immunotherapy 1: 599–621, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paczesny S, Braun TM, Levine JE, Hogan J, Crawford J, Coffing B, Olsen S, Choi SW, Wang H, Faca V, Pitteri S, Zhang Q, Chin A, Kitko C, Mineishi S, Yanik G, Peres E, Hanauer D, Wang Y, Reddy P, Hanash S, Ferrara JL: Elafin is a biomarker of graft-versus-host disease of the skin. Sci Transl Med 2: ra2, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shaw L, Wiedow O: Therapeutic potential of human elafin. Biochem Soc Trans 39: 1450–1454, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carella AM, Champlin R, Slavin S, McSweeney P, Storb R: Mini-allografts: Ongoing trials in humans. Bone Marrow Transplant 25: 345–350, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Doroshow JH, Synold TW: Pharmacologic basis for high-dose chemotherapy. In: Thomas' Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation, 4th Ed., edited by Appelbaum FR, Forman SJ, Negrin RS, Blume KG, West Sussex, United Kingdom, Wiley, Blackwell, 2009, pp 287–315 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown JMY: Fungal infections after hematopoietic cell transplantation. In: Thomas' Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation, 4th Ed., edited by Appelbaum FR, Forman SJ, Negrin RS, Blume KG, West Sussex, United Kingdom, Wiley, Blackwell, 2009, pp 1346–1366 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ho DY, Arvin AM: Varicella-zoster virus infections. In: Thomas' Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation, 4th Ed., edited by Appelbaum FR, Forman SJ, Negrin RS, Blume KG, West Sussex, United Kingdom, Wiley, Blackwell, 2009, pp 1388–1409 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ito JI: Herpes simplex virus infections. In: Thomas' Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation, 4th Ed., edited by Appelbaum FR, Forman SJ, Negrin RS, Blume KG, West Sussex, United Kingdom, Wiley, Blackwell, 2009, pp 1382–1387 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Leather HL, Wingard JR: Bacterial infections. In: Thomas' Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation, 4th Ed., edited by Appelbaum FR, Forman SJ, Negrin RS, Blume KG, West Sussex, United Kingdom, Wiley, Blackwell, 2009, pp 1325–1345 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zaia JA: Cytomegalovirus infection. In: Thomas' Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation, 4th Ed., edited by Appelbaum FR, Forman SJ, Negrin RS, Blume KG, West Sussex, United Kingdom, Wiley, Blackwell, 2009, pp 1367–1381 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martin P, Nash R, Sanders J, Leisenring W, Anasetti C, Deeg HJ, Storb R, Appelbaum F: Reproducibility in retrospective grading of acute graft-versus-host disease after allogeneic marrow transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant 21: 273–279, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sorror ML, Martin PJ, Storb RF, Bhatia S, Maziarz RT, Pulsipher MA, Maris MB, Davis C, Deeg HJ, Lee SJ, Maloney DG, Sandmaier BM, Appelbaum FR, Gooley TA: Pretransplant comorbidities predict severity of acute graft-versus-host disease and subsequent mortality. Blood 124: 287–295, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scott A, Weldon S, Taggart CC: SLPI and elafin: Multifunctional antiproteases of the WFDC family. Biochem Soc Trans 39: 1437–1440, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Alam SR, Newby DE, Henriksen PA: Role of the endogenous elastase inhibitor, elafin, in cardiovascular injury: From epithelium to endothelium. Biochem Pharmacol 83: 695–704, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gupta J, Mitra N, Kanetsky PA, Devaney J, Wing MR, Reilly M, Shah VO, Balakrishnan VS, Guzman NJ, Girndt M, Periera BG, Feldman HI, Kusek JW, Joffe MM, Raj DS, CRIC Study Investigators : Association between albuminuria, kidney function, and inflammatory biomarker profile in CKD in CRIC. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 7: 1938–1946, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Timoshanko JR, Kitching AR, Iwakura Y, Holdsworth SR, Tipping PG: Leukocyte-derived interleukin-1beta interacts with renal interleukin-1 receptor I to promote renal tumor necrosis factor and glomerular injury in murine crescentic glomerulonephritis. Am J Pathol 164: 1967–1977, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Antin JH, Ferrara JL: Cytokine dysregulation and acute graft-versus-host disease. Blood 80: 2964–2968, 1992 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zynek-Litwin M, Kuzniar J, Marchewka Z, Kopec W, Kusztal M, Patrzalek D, Biecek P, Klinger M: Plasma and urine leukocyte elastase-alpha1protease inhibitor complex as a marker of early and long-term kidney graft function. Nephrol Dial Transplant 25: 2346–2351, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sadeghi B, Al-Chaqmaqchi H, Al-Hashmi S, Brodin D, Hassan Z, Abedi-Valugerdi M, Moshfegh A, Hassan M: Early-phase GVHD gene expression profile in target versus non-target tissues: Kidney, a possible target? Bone Marrow Transplant 48: 284–293, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ohlsson S, Ljungkrantz I, Ohlsson K, Segelmark M, Wieslander J: Novel distribution of the secretory leucocyte proteinase inhibitor in kidney. Mediators Inflamm 10: 347–350, 2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moreau T, Baranger K, Dadé S, Dallet-Choisy S, Guyot N, Zani ML: Multifaceted roles of human elafin and secretory leukocyte proteinase inhibitor (SLPI), two serine protease inhibitors of the chelonianin family. Biochimie 90: 284–295, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zaidi SH, Hui CC, Cheah AY, You XM, Husain M, Rabinovitch M: Targeted overexpression of elafin protects mice against cardiac dysfunction and mortality following viral myocarditis. J Clin Invest 103: 1211–1219, 1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]