Abstract

Lacrimal glands of people over 40 years old frequently contain lymphocytic infiltrates. Relationships between histopathological presentation and physiological dysfunction are not straightforward. Data from rabbit studies have suggested that at least two immune cell networks form in healthy lacrimal glands, one responding to environmental dryness, the other to high temperatures. New findings indicate that mRNAs for several chemokines and cytokines are expressed primarily in epithelial cells; certain others are expressed in both epithelial cells and immune cells. Transcript abundances vary substantially across glands from animals that have experienced the same conditions, allowing for correlation analyses, which detect clusters that map to various cell types and to networks of coordinately functioning cells. A core network—expressing mRNAs including IL-1α, IL-6, IL-17A, and IL-10—expands adaptively with exposure to dryness, suppressing IFN-γ, but potentially causing physiological dysfunction. High temperature elicits concurrent increases of mRNAs for prolactin (PRL), CCL21, and IL-18. PRL is associated with crosstalk to IFN-γ, BAFF, and IL-4. The core network reacts to the resulting PRL-BAFF-IL-4 network, creating a profile reminiscent of Sjögren’s disease. In a warmer, moderately dry setting, PRL-associated increases of IFN-γ are associated with suppression of IL-10 and augmentations of IL-1α and IL-17, creating a profile reminiscent of severe chronic inflammation.

Keywords: aging, autoimmunity, chronic inflammation, dacryoadenitis, dry eye, prolactin, Sjögren’s disease*

I. INTRODUCTION

Dry eye disease is one of the most common morbidities eye care specialists are called upon to treat. The etiology is widely recognized as multifactorial. Certain inflammatory processes that arise in the lacrimal glands, most notably Sjögren’s disease,1,2 graft-versus-host disease,3 sarcoidosis,4,5 Wegener’s granulomatosis,6 HTLV-associated dacryoadenitis,7 and HIV-associated diffuse infiltrative lymphocytosis,8,9 are associated with severe physiological dysfunction that leads to keratoconjunctival inflammation. Recent data suggest that many cases of dry eye disease result from age-related decreases in meibomian gland function, impairment of the tear film lipid layer, accelerated evaporation, and increased tear film osmolarity.10–13 Accordingly, some authors have proposed that subsequently diagnosed lacrimal gland physiological dysfunction develops as an untoward consequence of the mechanisms that initially drive compensatory increases in lacrimal fluid production,10,13 but possible cellular bases for such a phenomenon have not yet been proposed.

A glossary of terms used in this review is appended to the article.

A. Inflammation and Physiological Dysfunction: Pathophysiological Diversity

Classic histopathological findings show chronic inflammation to be a normal, almost ubiquitous, concomitant of aging in the lacrimal glands. Waterhouse found lymphocytic infiltrates in 65% of lacrimal glands from women aged 75 years and older.14 Damato et al reported infiltrates in 70% of glands from women and men, mean age 62 ± 17 years.15 They also suggested that cases in which atrophic and fibrotic changes are not associated with notable infiltrates may be the sequelae of previous inflammatory processes. Obata et al reported infiltrates in 69% of palpebral glands and 83% of orbital glands from women and men between 40 and 87 years of age.16 Waterhouse found infiltrates in fewer of glands from elderly men (20%), but, strikingly, he also found that infiltrates begin to appear early in adult life and that they occur at similar rates (22% and 18%, respectively) in glands from women and men younger than 40 years of age. These numbers point to the conclusion that the prevalence of lymphocytic infiltrates is substantially greater than the prevalence of clinical dry eye disease, implying that the infiltrates that commonly develop are immunopathologically diverse, with diverse impacts on lacrimal physiological function. Moreover, as dry eye disease is several-fold more prevalent in women than in men, the disparity between the processes that do and do not cause clinically significant physiological dysfunction must be greater in men.

The contrast between Sjögren’s disease and Mikulicz’s disease17,18 illustrates the principle that some immune cell infiltrates are associated with physiological dysfunction, while others are relatively benign, at least with respect to lacrimal gland physiological function. Moreover, findings from laboratory studies suggest a general principle to account for the difference: Some mediators known to be produced by inflammatory infiltrates cause physiological dysfunction in ex vivo models, some do not, and some may augment fluid production. Nitric oxide (NO) impairs stimulus-secretion coupling in human labial salivary gland acinar cells,19 interleukin (IL)-1 suppresses protein secretion in ex vivo mouse lacrimal gland preparations,20 and both IL-1β and IL-6 suppress ionic currents associated with Cl− secretion and fluid production by a reconstituted rabbit lacrimal acinar epithelial model.21 Similarly, chronic stimulation with certain G protein-coupled receptor agonists, including cholinergic receptor agonists and biogenic amines, can impair both protein secretio 22,23 and Cl− secretion21, and other biogenic amines potentiate Cl− secretion and presumably augment lacrimal fluid production, but impair protein secretion.21–23 Interestingly, in another model, human retinal pigment epithelium, interferon (IFN)-γ enhances ion fluxes related to fluid transport.24

There has been some exploration of the diversity of cellular pathophysiologies associated with lacrimal gland lymphocytic infiltrates.2,5–27 The extent of the diversity is not yet fully established, however. The most common histopathological diagnosis, chronic dacryoadenitis, presents with diverse features, as immune cells may be concentrated in periductal/perivenular foci, or they may pervade large areas formerly occupied by acini, and they may affect a single lobule or most or all lobules; the infiltrates may or may not be accompanied by atrophic changes in the acini, in the ducts, or in both epithelial structures, and by fibrotic changes in the surrounding stromal spaces. Thus, chronic dacryoadenitis likely encompasses a spectrum of immunopathological processes.

B. Epithelial Factors and Development of Immunopathological Infiltrates

The mechanisms that cause noninfectious inflammatory infiltrates to develop in the lacrimal glands are unknown. A concept that has had considerable intellectual appeal is that the steroid reproductive hormones influence the spectrum of paracrine mediators that the gland’s epithelial cells express, and the local mediators in turn influence the balance between inflammatory and immunoregulatory activities in the gland.28 The importance of ongoing, constitutive peripheral immunoregulatory mechanisms is emphasized by the identification of lacrimal epithelial cell internal vesicle trafficking pathways that may constitutively release autoantigens to the lacrimal gland’s stromal spaces.29 Androgen therapy has proven highly beneficial in some murine models of inflammatory lacrimal gland diseases,30 and a preliminary case review study has suggested that androgen supplementation of estrogen-progestin replacement therapy ameliorates signs and symptoms in women with severe dry eye disease.31 Studies have found a number of intriguing clues into how the lacrimal epithelia function as a nexus between hormonal status and local immunological activity; nonetheless, this nexus has remained largely a black box, slow to yield insights into its inner workings.

It is has been known for some time that epithelial cells in apparently healthy lacrimal glands express several important immune-response-related mediators, most notably transforming growth factor (TGF)-β and prolactin (PRL),32,33 the latter being a cytokine as well as a hormone. Both are highly pleiotropic, and, as will be shown in this report, the influences PRL exerts in the lacrimal gland clearly are context-dependent. TGF-β mediates the immunoregulatory actions of natural (TRN-) and adaptive (TH3) T cells, but it also is involved in adaptive mucosal immunity, development of chronic inflammatory responses, and inflammation-associated fibrosis. Evidence from ex vivo studies indicates that TGF-β, secreted by acinar epithelial cells from rat lacrimal glands, directs monocytes to mature as dendritic cells with immunosuppressive- or immunoregulatory functions.34 This finding has been interpreted as suggesting that lacrimal epithelial cell-derived TGF-β orchestrates the ongoing generation of regulatory T cells, assumed to be CD4+, TH3 cells. However, it is not clear how the steroid reproductive hormones might interact with TGF-β to determine susceptibility to immunopathology. In murine lacrimal glands, steroid hormone influences on the expression TGF-β1 and TGF-β2, the isoforms most strongly implicated in immunoregulation, appear modest.3,5–37 Androgens upregulate expression of TGF-β3, but the role TGF-β3 might play in lacrimal immunoregulation has not been investigated.

PRL actions include promoting T cell and B cell proliferation38–40; inducing expression of IFN-γ41; inducing immature dendritic cells to differentiate as antigen presenting cells which promote TH1 activation42; and supporting expression of IL-4.43,44 A high molecular weight form of PRL has been reported to be elevated in biopsied labial salivary glands from patients with Sjögren’s disease, and PRL has been implicated in striking cellular physiological changes in rabbit lacrimal glands45 and ex vivo acinar cell models.46 A study, reported in preliminary form, has linked adenovirus vectormediated, transient, overexpression of PRL to severe, acute immunopathology in rabbit lacrimal glands. However, pregnancy, a state of physiological hyperprolactinemia, has been reported to be associated with immunoarchitectural changes that appear benign.47

Evidence confirms that the steroid reproductive hormones influence the expression of myriad additional genes, many immune response-related, in murine lacrimal glands,36,37 and analyses indicate that the higher levels of androgens in males largely account for gender-related dimorphisms in transcript expression.36 However, the impacts of steroid hormones clearly must be multifactorial, as both androgens and estrogens support expression of genes that are considered pro-inflammatory and genes that are considered anti-inflammatory.36,37

C. Recent Insights from Rabbit Studies

RT-PCR primer and probe sequences have been designed for a number of rabbit immune response-related gene transcripts, and a study using these tools has yielded surprising findings.48 Of 28 lacrimal glands taken from young adult virgin female rabbits that had been raised in an out-of-doors setting, only one gland presented with obvious immunopathological lesions. However, all glands contained mRNAs that typically are associated with innate inflammatory responses, e.g., CXCL8, IL-1α, IL-1β, and IL-6; mRNAs that function in the ectopic immune inductive tissues characteristic of Sjögren’s- and Mikulicz’s diseases, e.g., CCL21, CXCL13, BAFF, IL-4, and IL-1849,50 and mRNA for IL-2, which typically is expressed by TH1 cells. mRNA for IFN-γ, the hallmark cytokine of TH1 responses, was detected in the glands from three of the four groups of animals that were studied.

The abundances of many transcripts varied through wide ranges across the individual glands from each group, but, despite the large intragroup variability, it was possible to discern systematic associations between the median abundances of certain transcripts and the environmental conditions the rabbits had experienced. Median abundances of one cluster of transcripts increased in association with a composite measure of the desiccating influence of the environment during the 30 days before study. In contrast, median abundances of IFN-γ mRNA appeared to decrease in association with increasing desiccating influence. Median abundances of another cluster of transcripts, which included PRL, were highest in the group that had experienced the highest temperature. These associations suggested that the immune cells present in apparently healthy lacrimal glands organize themselves into at least two different networks, one that responds to signals related to environmental dryness, and one that responds to signals related to high environmental temperature. Median abundances of additional transcripts varied across the groups, but with no simple, readily discernible association with either environmental parameter.

II. NEW FINDINGS

We undertook experimental studies and analyses on the premise that information about the composition and behavior of the immune cell networks that form in apparently healthy glands would provide clues into how the most prevalent immunopathological states arise and set the stage for understanding how reproductive steroid hormones influence susceptibility to development of one state or another. The goals were to: 1) determine how expression of selected transcripts is distributed between immune cells and the major epithelial structures; 2) assay transcript abundances in lacrimal glands from an additional group of rabbits, selected as having experienced conditions intermediate between the group that had experienced the driest conditions and the group that had experienced the hottest conditions; 3) elucidate the networks that had formed in the glands from each of the five groups; and 4) assess the separate influences that dryness and high temperature might exert on the networks’ activities. As will be seen, the findings point to a multiplicity of networks, including a core network, which responds adaptively to signals related to dryness and reactively to signals from other cells and networks, and to several cell types which respond concurrently but not necessarily coordinately to signals related to high temperature. The various cells and networks can engage in both positive- and negative crosstalk with each other, and such crosstalk can lead to the emergence of more complex networks.

A. Materials and Methods

1. Animals

All protocols conformed to the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology (ARVO) Resolution on Use of Animals in Ophthalmic Research and were approved by the University of Southern California Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Groups of young adult virgin female New Zealand white rabbits, aged 16–18 weeks and weighing 3.5–4 kg, were acquired from Irish Farms (Norco, CA). Irish Farms is a non-barrier facility, and each group experienced a different combination of humidity and temperature arising from natural meterological variations.

2. Maximal Dryness and High Temperature

Meteorological data recorded at a station located near the Irish Farms facility were obtained from weatherunderground.com. The maximal daily dryness, Δ%H, was defined as 100% – daily low humidity. Mean values of maximal daily dryness and daily high temperature were calculated for the 30 days before each group of animals was moved to the University Vivaria; the mean values are plotted against Δ%H and T as orthogonal axes in Figure 1. Animals were consistently euthanized and necropsied 4 days after arrival at the University Vivaria

Figure 1.

Average daily maximal dryness and high temperature experienced by experimental groups during 30 days before arrival at USC Vivaria. Animals were consistently euthanized and necropsied 4 days after arrival.

3. Designation of Groups and Individual Glands

Lacrimal glands for this study were obtained from five groups of rabbits, designated with the letter V, for virgin, and with superscripts denoting the mean daily maximal dryness and mean daily high temperature, i.e., V58%,17°, V61%,27°, V68%,37°, V72%,32°, and V82%,29°. Group V58%,17° comprised two rabbits; groups V61%,27° and V68%,37° each comprised three rabbits; group V72%,32°, five rabbits; and group V82%,29°, six rabbits. A group of six term-pregnant animals, designated P82%,29°, was obtained at the same time as group V82%,29°. A preliminary analysis has shown that pregnancy exerts significant influences on the abundances of many immune response-related transcripts,51 and a full report of those findings is in preparation. Individual glands were designated according to the sequence in which the rabbits from each group were euthanized—V58%,17°01 and V58%,17°02; V61%,27°01 – V61%,27°03; V68%,37°01 – V68%,37°03; V72%,32°01 - V72%,32°0.5; V82%,29°01 – V82%,29°06; and P82%,29°01 – P82%,29°06—and according to whether they were from the left or right eye, i.e., OS or OD.

4. Tissue Collection and Processing

Inferior lacrimal glands from all groups except V58%,17° were divided into parts placed in RNALater™ for RNA extraction and real time RT-PCR analyses; parts placed in 10% formalin for paraffin embedding and H&E staining; and parts placed in OCT for immunohistochemical staining. The OCT-embedded samples from V68%,37° andV61%,27° were lost in a freezer failure after staining for RTLA and CD18 was completed. Samples from V82%,29° were allocated to several projects, and limited amounts were available for this study.

5. Immunohistochemical Staining and Image Analysis

Frozen sections were stained, examined, and analyzed according to methods that have been described in previous publications.48

6. Laser Capture Microdissection

Samples of epithelial cells from acini, intralobular-, interlobular-, and intralobar ducts, and samples of immune cell accumulations were obtained by laser capture microdissection as described by Ding et al.52

7. RNA Extraction, Reverse Transcription, and Real-Time RT-PCR

Methods for mRNA extraction, reverse transcription, and real-time polymerase chain reaction (PCR) are described elsewhere.53 RNA extracts from the individual glands were analyzed separately. The primer- and probe sequences were based on published rabbit gene sequences. The abundance of each target mRNA in each tissue extract was calculated relative to the abundance of GAPDH mRNA in the same extract. The abbreviations for the transcripts assayed are presented in the Glossary, along with basic information about the transcripts’ products’ roles and the cells that express them.

8. Data Analysis and Presentation

Sigmaplot 12.0 (Systat Software, San Jose, CA) was used for Pearson’s correlation tests and linear- and non-linear regression analyses.

a. Glands That Appeared as Outliers

Four individual glands—V61%,27°02.OS, V68%,37°02.OS, V68%,37°03.OS, and V72%,32°01.OD— stood apart from the other glands in their respective groups by having considerably higher abundances of certain transcripts. Transcript abundances in each of these glands are designated with unique symbols in the figures, and each is discussed as an informative case study.

b. Correlation Analyses

Correlations between transcript abundances among the individual glands of each group were analyzed by Pearson’s test for multiple correlations. Transcript abundances in glands that appeared as outliers were excluded from Pearson’s analyses in order to minimize type 1 and type 2 errors. The numbers of glands for which values were analyzed were: V58%,17°, four; V61%,27°, five; V68%,37°, four; V82%,29°, twelve; V72%,32°, nine. Rows and columns in the table of Pearson’s statistics for each group were organized to maximize the blocks of contiguous cells containing values of P ≤.05. This empirical approach, which required no assumptions about the identities of the cell types that expressed the transcripts, made it possible to discern correlation clusters, i.e., clusters of transcripts whose abundances varied coordinately.

Non-linear regression analyses were performed to identify significant exponential relationships between transcripts:

where x = the abundance of a transcript selected as a reference.

c. Mapping Correlation Clusters to Cells and Networks

The correlation clusters discerned with Pearson’s analyses and clusters of non-linearly- related transcripts were mapped to cell types or to networks of cells on the basis of the data from the laser capture microdissection surveys and published information about cell types that express the various transcripts, summarized in the Glossary. The maps are presented in standard histoarchitectural schemas comprising generic epithelial cells, lymphocytes, and MMΦDC. Variations in abundance of some transcripts, e.g., transcripts expressed by epithelial cells, may reflect variations in the levels of expression in cells whose relative numbers do not vary. Variations in abundance of other transcripts may reflect both variations in the numbers of cells expressing the transcripts and also variations in levels of expression per cell.

In some cases, it was possible to infer hypotheses about the signals responsible for the associations between different transcripts’ abundances. For example, increasing expression of PRL is known to mediate increased expression of IL-4 and increased expression of IFN-γ; increasing expression of IL-4 is known to mediate decreased expression of IFN-γ; and IL-10 and IFN-γ are known to counter-regulate each other’s expression. The analyses also discerned associations that have not been reported previously. The signals that coordinated the programs of expression underlying the new associations are not known, and it is possible that those signals were mediated by products of transcripts that have not been assayed. Therefore, for the purposes of this communication, the generic term, “crosstalk,” is used as a rubric for both the hypothesized and the unknown signals.

As none of the networks has previously been described in lacrimal glands, the names assigned to them were selected to evoke salient network features, whether functions, cell types, or mediators.

d. Judging Whether Networks Might be Intact in Glands that Appear as Outliers

Both linear and nonlinear regression analyses were used to identify cases where transcript abundances in the glands that appeared as outliers were likely to have been subject to the same forms of crosstalk as the other glands of their respective groups.

e. Relationships between Transcript Abundances and Meteorological Variables

In the initial analysis of glands from V58%,17°, V61%,27°, V68%,37°, and V82%,29°, values for all transcripts in the glands that appeared as outliers were excluded from the statistical analyses, and the mean transcript abundances in the remaining glands were tested for significant relationships to a composite variable, the number of desiccating T/H days.48 For the new analyses described in this report, the medians of the entire samples of values from each group were determined, and the 30-day mean high temperature and the 30-day mean dryness ( ) were treated as independent variables. The relationships between median abundances and mean daily high temperature and mean daily dryness were tested using the same exponential growth functions listed above, with or x = T̄ or x= T̄. As will be shown, the exponential functions provided strong, highly significant, empirical descriptions of relationships between several transcripts’ median abundances and either dryness or high temperature.

The functions of exponential growth with dryness and exponential growth with heat also were used as heuristics for describing the behaviors of median transcript abundances over specific domains of the surface when transcripts appeared to have been subject to additional influences in one group or another. As will be seen, the additional influences appeared in many cases as crosstalk arising from cells and networks that expressed other transcripts. When the median abundances and heuristics are plotted against the appropriate axis, the additional influences can be seen as acting in one group or two groups to augment abundance above-, or suppress it below, the value predicted by its heuristic.

B. Histoarchitectural Organization of Transcript Expression

As summarized in Figure 2, the laser capture microdissection survey indicated that mRNAs for lipophilin CL, CCL2, and IL-2 were most abundant in acinar cells, but they also were detectable in immune cell accumulations. mRNAs for PRL and APRIL were most abundant in acinar cells and also abundant in ductal epithelial cells, but much less abundant in immune cell accumulations. TGF-β2 mRNA was localized to ductal epithelial cells and present at similar levels in the three duct segments. CCL4 mRNA was present at similar levels in interlobular duct cells and in immune cell accumulations. IL-1RA mRNA was present at similar levels in interlobular duct cells, intralobar duct cells, and immune cell accumulations. Decorin mRNA was most abundant in immune cell accumulations, but it also was present in acinar cells and in each of the duct segments. mRNAs for TGF-β1, CD25, and BAFF were predominantly localized to immune cells, but they also were detectible in intralobar duct epithelial cells. mRNAs for IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-10 were predominantly localized to immune cell accumulations.

Figure 2.

Histoarchitectural organization of transcript expression: Relative abundances in acini, intralobular ducts, interlobular ducts, and intralobar ducts. Two V82%,29° glands were microdissected with a laser capture system. Two additional glands from term pregnant animals (P82%,29°) also were microdissected; those data will be reported elsewhere. The intensity of shading in each structure is proportional to the transcript’s highest mean relative abundance. Note that the highest abundances of TGF-β1 were found in periductal/perivenular immune cell accumulations, while the highest abundances of TGF-β2 were found in the three duct segments. The highest abundances of CCL2 were found in acinar cells, and the highest abundances of CCL4 were found in interlobular duct cells. The highest abundances of mRNAs for lipophilin CL and for the mitogenic cytokines, IL-2, APRIL, and PRL also were found in acinar cells, and mRNAs for APRIL and PRL were additionally found in cells of all three duct segments.

C. Intergroup Variations, Intragroup Variations, Correlation Clusters, Cells, and Networks

Supplemental Figure 1 presents an overview of relationships between abundances of mRNAs for IFN-γ, IL-4, and IL-1α and abundances of mRNAs for IL-10 and PRL across the glands from each of the five rabbit groups. It also presents relationships between abundances of mRNAs for IL-17A, iNOS, and CD1d and mRNAs for IL-10 and PRL across the glands from the two groups in which they could be assayed, V72%,32° and V82%,29°. Supplemental Figure 2 presents the abundances of transcripts that appeared to be systematically related to dryness, and Supplemental Figure 3 presents the abundances of transcripts that appeared to be systematically related to high temperature exposure. Representative relationships are described in detail in Sections II.D.1 and II.D.2. Supplemental Figure 4 presents the abundances of the transcripts for which simple relationships to dryness or temperature could not be discerned.

The Supplemental Figures demonstrate that many transcripts’ abundances varied considerably across the individual glands of each group. As illustrated in Figure 3, much of the intragroup/intergland variability stemmed from phenomena that were localized within individual glands, as there was little correlation between many transcripts’ abundances in the OS gland and the OD gland from the same animal. Nevertheless, such intragroup/intergland variability was highly systematic in the sense that the abundances of clusters of transcripts varied coordinately. Statistics from Pearson’s multiple correlation tests are presented in Supplemental Tables 1–5; values of P ≤.05 are shaded to highlight the empirical correlation clusters. Nonlinear regression analyses identified additional significant relationships. Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8 present the schemas with the correlation clusters and nonlinear relationships mapped to various cells and networks.

Figure 3.

Transcript abundances in OS and OD lacrimal glands from V82%,29°. The transcripts that showed the largest OS-OD variations were positively associated with a core adaptive-reactive network. The variability between companion glands emphasizes the importance of stochastic events and positive crosstalk at the level of the individual gland.

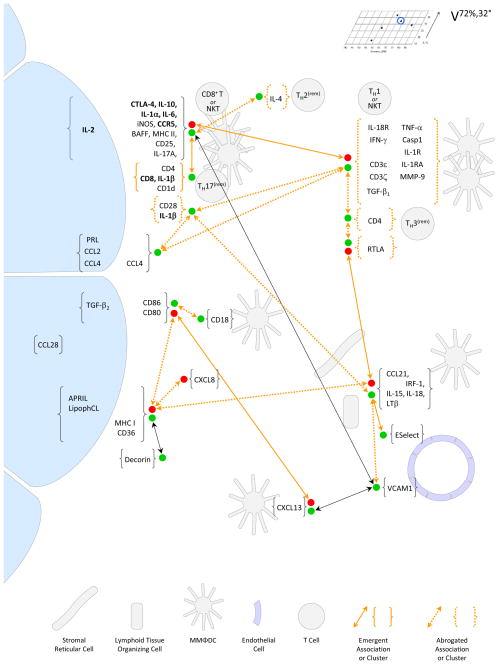

Figure 4.

Schema depicting the correlation clusters detected and the cell types and networks inferred in glands from V58%,17°. Pearson’s correlation statistics and empirical correlation clusters are presented in Supplemental Table 1. Relationships between the abundances of selected transcripts and the abundances of mRNAs for IL-10 and PRL are presented in Figure 9. Brackets { } indicate transcripts that sorted to correlation clusters and parenthesis ( ) indicate transcripts that were assayed but not found to be significantly associated with other transcripts. Green dots (●) indicate positive associations; red dots (●) indicate negative associations. The large cells at the left represent epithelial cells without distinguishing between the acini and the three duct segments analyzed. CCL4 mRNA was found both in interlobular duct epithelial cells and in immune cell accumulations; whether variations at one site are associated with variations at the other has not been determined. Decorin mRNA was detected in acinar cells and in all ductal segments, but it was most abundant in immune cell accumulations, and, for simplicity, it is shown as being localized to immune cell accumulations. In groups that had been exposed to more dryness and higher temperatures (Figure 5 – Figure 8), mRNAs for IL-1β and IL-2; IL-6; CD8; and IL-1α, CTLA-4, and IL-10; and, in most cases, CCR5 sorted to the same correlation cluster, creating the signature of the core, adaptive-reactive network. Theses transcripts are denoted in bold type.

Figure 5.

Schema depicting the correlation clusters detected and the cell types and networks inferred in glands from V61%,27°. Pearson’s correlation statistics are presented in Supplemental Table 2. Relationships between abundances of selected transcript and abundances of mRNAs for CD4 and IL-10 are presented in Figure 10. Details are as described in the legend to Figure 4. The core, adaptive-reactive network developed independently of the TH3-remniscent network, and it generated negative crosstalk to cells—presumably TH1 cells or NKT—that expressed IFN-γ mRNA. TH3-reminiscent network engaged in positive crosstalk with cells—possibly, TH2 cells—that expressed IL-4 mRNA and with cells that expressed mRNAs for CXCL13, Casp1, MMP-9, CCL21, CD3ε, and CD3ζ. The phenomena depicted as emergent were associated with appearance of the frank immunopathological state in gland V61%,27°02.OS. These phenomena might have been triggered either by some adventitious event, such as trauma or infection, or by a stochastic event, such as the coincidence of large numbers of TH2-reminiscent cells and large numbers of cells of the core, adaptive-reactive network giving rise to a new network.

Figure 6.

Schema depicting the correlation clusters detected and the cell types and networks inferred in glands from V68%,37°. Pearson’s correlation statistics are presented in Supplemental Table 3. Details are as described in the legend to Figure 4. Associations between the abundances of mRNAs for PRL, IFN-γ, IL-4, and BAFF are shown in Figure 12.A. Epithelial cells expressing PRL mRNA engaged in positive crosstalk with TH1- reminiscent cells expressing IFN-γ and with TH2-reminicent cells expressing IL-4. They also engaged in negative crosstalk with TH3-reminiscent cells. Negative crosstalk between IL-4-expressing cells and BAFF-expressing cells was abrogated at higher levels of PRL expression, and negative crosstalk between IL-4 expressing cells and IFN-γ-expressing cells emerged at the highest level of PRL expression. The core, adaptive-reactive network initially developed independently of the interplay between cells expressing mRNAs for PRL, IL-4, BAFF, and IFN-γ. The emergent phenomena depicted represent the state in gland V68%,37°02.OS, associated with positive crosstalk between the core, adaptive-reactive network; cells expressing PRL, BAFF, and IL-4; and cells expressing CCL2 and CCL4. These interactions played out in a local setting of concurrently high levels of IL-18 mRNA expression and high levels of CCL21 mRNA expression. With the exception of negative crosstalk between cells expressing CCL21 and cells expressing CXCL13, the resulting transcript expression profile is reminiscent of Sjögren’s ectopic immune inductive tissue. The state that emerged in gland V68%,37°03.OS (not shown) may have been associated with the appearance of and additional source of IL-10 mRNA expression (Figure 12.B).

Figure 7.

Schema depicting the cell types and networks inferred in glands from V72%,32°, based on Pearson’s correlation statistics presented in Supplemental Tables 4 - 6; certain associations that were significant across the entire sample of glands (Supplemental Table 6) are omitted to simplify depiction of the emergent phenomena. Associations between the abundance of IFN-γ mRNA and the abundances of mRNAs for IL-10 and PRL are shown in Figure 13.A. Relationships between the abundances of additional transcripts and the abundances of mRNAs for IL-10 and IFN γ are shown in Figure 14. Details are as described in the legend to Figure 4. The findings presented in Figure 13.A suggest that a critical feature of the initial state was positive crosstalk between epithelial cells expressing PRL mRNA and cells—presumably TH1 cells or NKT cells—expressing IFN-γ mRNA. Rather than abrogating this crosstalk, TH3-reminiscent cells expressing TGF-β2 accumulated coordinately. Emergence of the second state may have depended on abrogation of the PRL mRNA - IFN-γ crosstalk by increasing levels of IL-10 expression, associated with ongoing development of the core, adaptive-reactive network. Emergence of a third state, in gland V72%,32°01.OD, was characterized by disproportionately large increases in the expression of IL-17A, IL-10, CD8, and CD28. As can be seen in Supplemental Figure 1, all three states are characterized by relatively low levels of IL-10 expression and relatively high levels of IL-1α and IL-17A expression.

Figure 8.

Schema depicting the correlation clusters detected and the cell types and networks inferred in glands from V82%,29°. Pearson’s correlation statistics are presented in Supplemental Table 7. The abundance of IFN-γ mRNA (

) was below the limit of detection. Details are as described in the legend to Figure 4. Development of the core, reactive-adaptive network was associated with positive crosstalk to TH2-reminiscent cells, which expressed IL-4; with positive crosstalk to cells that expressed CCL21; and, indirectly, with positive crosstalk to cells that expressed CXCL13. As shown in Figure 11, none of the glands presented with frank immunopathology, but as discussed in Section III, increasing levels of iNOS, IL-1, and IL-6 may come to be associated with physiological dysfunction.

) was below the limit of detection. Details are as described in the legend to Figure 4. Development of the core, reactive-adaptive network was associated with positive crosstalk to TH2-reminiscent cells, which expressed IL-4; with positive crosstalk to cells that expressed CCL21; and, indirectly, with positive crosstalk to cells that expressed CXCL13. As shown in Figure 11, none of the glands presented with frank immunopathology, but as discussed in Section III, increasing levels of iNOS, IL-1, and IL-6 may come to be associated with physiological dysfunction.

1. A Core, Adaptive-Reactive Network

The abundances of mRNAs for IL-1α, IL-10, and CTLA-4 correlated significantly in all five groups (Supplemental Figure 1, Supplemental Tables 1–5). In V61%,27°, V68%,37°, V72%,32°, and V82%,29°, these transcripts sorted to correlation clusters that also included mRNAs for CD8, CTLA-4, IL-1β, and IL-6. In V61%,27°, V72%,32°, and V82%,29°, the correlation cluster also included mRNAs for IL-2 and CCR5. The abundances of mRNAs for IL-17A and iNOS could be assayed only in V72%,32° and V82%,29°; both sorted to the cluster in both groups.

The transcripts in the cluster map to a novel network of diverse cells. IL-10 is classically expressed by TH2 cells, but it also is expressed by TR1 cells, NKT cells, and MMΦDC lineage cells. IL-1α, IL-1β, and IL-6 are classically expressed by MMΦDC lineage cells involved in innate responses; they were expressed primarily in immune cell accumulations (Figure 2), but the identities of the cell types that express them remain to be determined. IL-2 is classically a TH1 cytokine, but IL-2 mRNA was expressed primarily in acinar cells (Figure 2). CTLA-4 is typically expressed by T cells. CD8 is expressed by T cells with conventional—i.e., hypervariable—TCR α-subunits with both effector and regulatory functions; it also may be expressed by NKT cells and MMΦDC lineage cells. CCR5 is the primary receptor for CCL4. IL-17A is typically expressed by eponymous TH17 cells, which are positive for CD4,54 but it also may be expressed by NKT cells and γδ T cells. iNOS can be expressed by various cell types, including, notably, activated MMΦDC lineage cells. As will be shown in Section II.D.1 and II.D.2, the abundance of each of the cluster transcripts can be described as having increased in association with increasing exposure to dryness, and the increases appear adaptive in that they are associated with decreased expression of IFN-γ mRNA. The network reacts to crosstalk from other cells and networks in certain settings. In other settings, it appears to engage with other cells and networks to form more complex networks. Therefore, for the purposes of this report, it will be referred to as the core, adaptive-reactive network.

2. Core, Adaptive-Reactive Network Transcripts in V58%,17°

It is not clear that the core, adaptive-reactive network had formed in V58%,17°. Figure 9 presents abundances of selected transcripts in V58%,17°. The statistical power for V58%,17° is quite low, but, as shown in Figure 4, the core, adaptive-reactive network transcripts appeared to sort to three smaller clusters: 1) mRNAs for IL-1β and IL-2 associated with mRNAs for CD80 and decorin (ρmean=.936, Pmean=.064); 2) mRNAs for IL-1α, IL-10, and CTLA-4 associated with mRNAs for CD28 and CD86 (ρmean=.933, Pmean=.067); and 3) IL-6 mRNA associated with IL-4 mRNA (ρ=.971, P=.029). Apparent cross-correlations between cluster 1 and cluster 2 (ρmean=.850, Pmean=.150) were not statistically significant; possible correlations between CD8 mRNA and the two clusters were, at best, weak (.591 ≥ρ≥.309); and the strongest of the possible associations for CD8 mRNA was with CD25 mRNA (ρ=.922, P=.0779).

Figure 9.

Relationships between abundances of selected transcripts and abundances of mRNAs for IL-10 and PRL in glands from V. G4. Significant associations with IL-10 mRNA are projected onto the back walls. Significant associations with PRL mRNA are projected onto the left side walls.

3. Additional Transcripts Associated with the Core, Adaptive-Reactive Network in V82%,29°

Statistical powers for V61%,27° and V68%,37° are lower than for V82%,29°. As will be discussed in Sections II.C.7 and II.C.8, analyses of transcript abundances in V72%,32° glands, with gland V72%,32°01.OD set aside as an apparent outlier, reveal that the glands sorted to two clusters, comprising, respectively, four glands and five glands, representing two phases of network development. The mean values of Pearson’s ρ and P statistics summarized in Table 1 identify several transcripts that were not likely to have been associated with the core, adaptive-reactive network in V61%,27° or V68%,37° but were significantly associated with it in V82%,29°. Most notably, CD4 mRNA was associated with the network in V82%,29°, but clearly not associated with it in V61%,27° or V68%,37°. mRNAs for CD25, MHC II, BAFF, CD28, PRL, IL-4, CCL2, CCL4, CCL21, and CD4 were significantly associated with the core, adaptive-reactive network in V82%,29°. The data in Table 1 indicate that factors other than differences in the state of the core, adaptive-reactive network’s development accounted for most of the variations in the abundances of mRNAs for CD25 and CD28 in V61%,27°, and for most of the variations in the abundances of mRNAs for MHC II, BAFF, PRL, IL-4, CCL2, and CD4 in V68%,37.

Table 1.

Pearson’s Statistics for Associations with the Core Adaptive-Reactive Network Transcripts: ρ and (P)

Values presented are mean Pearson’s ρ (upper cell) and P (lower cell) statistics for associations between the indicated transcripts’ abundances and the abundances of the core adaptive-reactive network transcripts (mRNAs for IL-10, CD8, CTLA-4, IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-6, and CCR5; values for CCR5 in V68%,37° were excluded due to likely associations with additional networks in that setting).

| mRNA | V61%,27° (n=5) | V68%,37° (n=4) | V82%,29° (n=12) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CD25 | 0.024 (0.901) | 0.623 (0.377) | 0.881 (0.002) |

| MHC II | 0.668 (0.227) | 0.202 (0.767) | 0.790 (0.006) |

| BAFF | 0.338 (0.582) | 0.194 (0.720) | 0.879 (0.001) |

| CD28 | −0.065 (0.849) | 0.478 (0.522) | 0.745 (0.007) |

| PRL | 0.476 (0.426) | 0.072 (0.866) | 0.716 (0.010) |

| IL-4 | −0.602 (0.286) | 0.070 (0.834) | 0.745 (0.007) |

| CCL2 | 0.715 (0.179) | −0.155 (0.800) | 0.788 (0.005) |

| CCL4 | 0.644 (0.246) | 0.611 (0.389) | 0.854 (0.002) |

| CCL21 | −0.555 (0.337) | −0.576 (0.424) | 0.665 (0.027) |

| CD4 | −0.341 (0.578) | −0.033 (0.848) | 0.829 (0.002) |

| Lipoph.CL | — | −0.289 (0.647) | −0.671 (0.023) |

| IL17A | — | — | 0.914 (0.001) |

| iNOS | — | — | 0.849 (0.002) |

Association Significant

Association Significant

Bold Association Appears Unlikely

4. A TH3-Reminiscent Cluster and Network Associations in V61%,27°

Across the first five V61%,27° glands, the numbers of cells positive for the T cell marker, RTLA, and the abundances of mRNAs for TGF-β1, CD4, CD25, CD28, TNF-α, CD80, CD86, CCL21, CD3ε, CD3ζ, CXCL13, and decorin sorted to the same correlation cluster (Figure 10.A). Associations between RTLA+ cells and mRNAs for TGF-β1, CD4, CD25, and CD28 are reminiscent of TH3 cells. Associations between mRNAs for CD86, CD80, and TNF-α are reminiscent of MMΦDC lineage cells. Associations between mRNAs for CCL21, CD3ε, and CD3ζ are reminiscent of T cell inductive tissue, as CCL21 recruits naïve T cells,55 and the CD3ε and CD3ζ subunits of the TCR signaling complex are highly expressed by naïve T cells.56,57 CXCL13, typically expressed by MMΦDC lineage cells, recruits B cells58,59; therefore, the association of CXCL13 mRNA with the TH3-reminiscent cluster transcripts also is reminiscent of immune inductive tissue.

Figure 10.

Relationships between abundances of selected transcripts and abundances of mRNAs for CD4 and IL-10 in glands from V61%,27°. Values for gland V61%,27°02.OS (

) were omitted from the initial regression analyses to minimize both type 1 and type 2 errors. Solid lines indicate range of X-axis values over which regressions were calculated, and dashed lines indicate projections. A. Associations with CD4 mRNA. The number of T cells (RTLA+ cells) and the abundance of CCL21 mRNA increased in approximately constant proportions across the entire sample of glands. Exponential regressions of IL-4 and MMP-9 mRNA abundances across the first five glands fell short of the P <.05 criterion for statistical significance. However, projections of both predicted values in gland V61%,27°01.OS that were near the observed values, and regressions calculated across all six glands were highly significant (dotted lines). B. Lack of a significant association between the abundances of mRNAs for CD4 and IL-10 across the first five V61%,27° glands. C. Associations with IL-10 mRNA. With the exception of CCR5 mRNA, the abundances of core, adaptive-reactive network transcripts in gland V61%,27°02.OS fell within two standard errors of the proportions in the other V61%,27° glands. This finding suggests that the network remained intact as it reacted to positive crosstalk associated with the immunopathological process. Abundances of mRNAs for CCL4, CCL2, CD25, CD28, BAFF, and numbers of bone marrow-derived cells—marked by CD18—were not significantly associated with the core, adaptive-reactive network transcripts across the first five glands but were significantly increased in gland V61%,27°02.OS.

) were omitted from the initial regression analyses to minimize both type 1 and type 2 errors. Solid lines indicate range of X-axis values over which regressions were calculated, and dashed lines indicate projections. A. Associations with CD4 mRNA. The number of T cells (RTLA+ cells) and the abundance of CCL21 mRNA increased in approximately constant proportions across the entire sample of glands. Exponential regressions of IL-4 and MMP-9 mRNA abundances across the first five glands fell short of the P <.05 criterion for statistical significance. However, projections of both predicted values in gland V61%,27°01.OS that were near the observed values, and regressions calculated across all six glands were highly significant (dotted lines). B. Lack of a significant association between the abundances of mRNAs for CD4 and IL-10 across the first five V61%,27° glands. C. Associations with IL-10 mRNA. With the exception of CCR5 mRNA, the abundances of core, adaptive-reactive network transcripts in gland V61%,27°02.OS fell within two standard errors of the proportions in the other V61%,27° glands. This finding suggests that the network remained intact as it reacted to positive crosstalk associated with the immunopathological process. Abundances of mRNAs for CCL4, CCL2, CD25, CD28, BAFF, and numbers of bone marrow-derived cells—marked by CD18—were not significantly associated with the core, adaptive-reactive network transcripts across the first five glands but were significantly increased in gland V61%,27°02.OS.

5. A TH2-Reminiscent Profile in Gland V61%,27°02.OS

Gland V61%,27°02.OS stood apart from the other V61%,27° glands in having large, pathological accumulations containing RTLA+ cells and CD18+ cells.48 It also had higher abundances of mRNAs for CD4 and CCL21, but not of the other TH3-reminiscent cluster transcripts; higher abundances of mRNAs for IL-4 and MMP-9 (Figure 10.A); and higher abundances of other transcripts, as well (Figure 10.B, discussed below). Although elevated, the number of RTLA+ cells and the abundances of mRNAs for CD4 and CCL21 were in the same proportions as in the other V61%,27° glands. The abundances of mRNAs for IL-4 and MMP-9 could be described as having increased exponentially as the abundance of CD4 mRNA increased across the V61%,27° glands. The association between mRNAs for IL-4 and CD4 is reminiscent of TH2 cells. These findings imply that TH2-reminiscent cells accumulated, and MMP-9 expression increased, concurrently with accumulation of TH3-reminiscent cells, but with different kinetics.

Images of sections of V58%,17°, V61%,27°, V68%,37°, and V82%,29° glands stained for RTLA and CD18 have been presented by Mircheff et al. Representative images of V72%,32° glands are presented in Figure 11. The transcript expression profile of gland V61%,27°02.OS implicates cells, possibly of the MMΦDC lineage, expressing high levels of CCR5 mRNA, and T cells expressing high levels of mRNAs for CD4, CD25, and CD28 in the immunopathological process. Therefore, it is notable that more T cells, more CD18+ cells, and higher abundances of transcripts such as IL-4 mRNA, MMP-9 mRNA, and CCL21 mRNA were found in glands from other groups which were free of evident immunopathology (Supplemental Figures 2, 3, and 4).

Figure 11.

Representative sections of V72%,32° glands stained for RTLA and CD18. Images of similarly stained sections of V58%,17°, V61%,27°, V68%,37°, and V82%,29° glands have been presented elsewhere. Immunopathological lesions are not evident in any gland, and gland V72%,32°01.OD, which had higher abundances of numerous transcripts, had fewer than the median number of CD18+ cells and the fewest RTLA+ cells.

6. The Core, Adaptive-Reactive Network and the Inflammatory Process in Gland V61%,27°02.OS

The plot of CD4 mRNA and IL-10 mRNA abundances in Figure 10.B indicates that the core, adaptive-reactive network developed independently of the accumulating TH3-reminiscent cells and TH2-reminiscent cells across the first five V61%,27° glands. Like mRNAs for IL-4 and MMP-9, the core, adaptive-reactive network transcripts were considerably more abundant in gland V61%,27°02.OS than the other V61%,27°glands (Figure 10.B). With the exception of CCR5 mRNA, the core, adaptive-reactive network transcripts’ abundances remained in the same proportions in gland V61%,27°02.OS as in the other V61%,27° glands. Likewise, the abundances of most of the additional transcripts that associated with the core, adaptive-reactive network in V82%,29° (Table 1) also were considerably higher in gland V61%,27°02.OS than their V61%,27° median values (Figure 10.B). These findings imply that the core, adaptive-reactive network remained intact in gland V61%,27°02.OS, even though its activity had increased in reaction to crosstalk from the immunopathological process.

7. Crosstalk between Cells Expressing mRNAs for PRL, IL-4, IFN-γ, and IL-10

The abundance of IFN-γ mRNA increased exponentially as the abundance of PRL mRNA increased across the first five V68%,37° glands (R2=0.993, P =.0003, Figure 12.A). This relationship accords with the pro-TH1 influences that PRL exerts in other systems. However, in gland V68%,37°02.OS, where PRL mRNA was most abundant, the abundance of IFN-γ mRNA was 100-fold less than predicted by the exponential growth relationship across the first five glands. Notably, the abundance of IL-4 mRNA increased exponentially as the abundance of PRL mRNA increased across the entire sample of glands (R2=0.996, P <.0001), such that it was highest in gland V68%,37°02.OS. This relationship accords with reports that PRL supports expression of IL-4,43,44 and it therefore suggests that epithelial cells which expressed PRL mRNA formed a network with TH2-reminiscent cells which expressed IL-4 mRNA. The relationships also suggest that TH1-reminiscent cells or NKT cells expressing IFN-γ mRNA (referred to as TH1/NKT-reminiscent cells for purposes of this communication) received contradictory crosstalk from the PRL-mediated epithelial-TH2-reminiscent network, i.e., positive crosstalk associated with expression of PRL mRNA and negative crosstalk associated with expression of IL-4 mRNA, and that the highest level of IL-4 mRNA expression was associated with abrogation of PRL-associated support for IFN-γ mRNA expression.

Figure 12.

Relationships between abundances of selected transcripts and abundances of mRNAs for PRL and IL-10 in glands from V68%,37°. A. PRL mRNA. The regression of IFN-γ mRNA abundances calculated across the first four glands fell short of the P < .05 criterion, but the projection for gland V68%,37°02.OS (⊗) was nearly identical to the observed value. The regression calculated through gland V68%,37°02.OS was highly significant (dotted line). The regression of BAFF mRNA abundances calculated across all six glands was significant, but it obscures a significant negative association (ρ = −0.961, P = .0386) between the abundance of BAFF mRNA and the abundance of IL-4 mRNA across the first four glands. B. IL-10 mRNA. Abundances in glands V68%,37°02.OS and V68%,37°03.OS (⊕) were omitted from the regression analyses to minimize type 1 and type 2 errors. Values for gland V68%,37°02.OS projected by regressions calculated over the first four glands were similar to the observed values for mRNAs for IL-1α, CTLA-4, CD8, and IL-6.

Positive and negative associations between the abundance of IFN-γ mRNA and the abundances of other transcripts also played out in V72%,32°, where the abundance of IFN-γ mRNA reached higher levels than in any other group. The multiphasic relationship between the abundance of IFN-γ mRNA and the abundances of mRNAs for IL-10 and PRL in V72%,32° (shown in Supplemental Figure 1) is illustrated on an expanded scale in Figure 13.A. As across the first five V68%,37° glands, the abundances of IFN-γ mRNA and IL-4 mRNA increased with increasing abundance of PRL mRNA across the first four V72%,32° glands; these increases may reflect development of the PRL-mediated epithelial-TH2 network in association with accumulation of TH1/NKT-reminiscent cells. The abundance of IFN-γ mRNA decreased as the abundance of IL-10 mRNA increased across the next five V72%,32° glands (R2=0.944, P=.0012). The phase of decreasing IFN-γ mRNA abundances accords with the TH1/TH2 paradigm.60 It also accords with the TH1/IL-17 paradigm,61,62 as IL-17A mRNA was associated with the core, adaptive-reactive network in V72%,32°; but the association of IFN-γ mRNA with IL-10 mRNA was stronger (ρ=−0.929) than the association with IL-17A mRNA (ρ = −0.740). The abundance of IFN-γ mRNA in the tenth gland, V72%,32°01.OD, was considerably higher than predicted by the inverse relationship; the unique transcript abundance profile of this gland is described in Section II.C.9.

Figure 13.

Relationships between the abundances of IFN-γ mRNA and the abundances of mRNAs for IL-10 and PRL in glands from groups V61%,27° and V72%,32°. Dark areas in projections onto rear and side walls indicate ranges of IL-10 mRNA abundances and IFN-g mRNA abundances over which regressions were calculated. A. Group V72%,32°. The abundance of PRL mRNA was significantly related to the abundance of IL-10 mRNA across the first nine glands. The abundance of IFN-γ mRNA increased with increasing abundance of PRL mRNA across the first four glands and decreased with increasing abundance of IL-10 mRNA across the next five glands. B. Group V61%,27°. The abundance of IFN-γ mRNA decreased with increasing abundance of IL-10 mRNA across the first five glands. The value the regression projected for gland V61%,27°02.OS was similar to the observed value.

Also in accord with the TH1/TH2 paradigm, the abundance of IFN-γ mRNA decreased exponentially (R2 = 0.994, P=.0061) as the abundance of IL-10 mRNA increased across the V61%,27° glands (Figure 13.B). Moreover, IFN-γ mRNA was not detectable in glands from V82%,29°, the group with the highest abundances of mRNAs for IL-10 and IL-17A.

8. Positive- and Negative Crosstalk to a TH1/NKT-Reminiscent-TNF-α Network in V72%,32°

The numbers of RTLA+ cells and the abundances of mRNAs for TNF-α, CCL2, CCL4, CD3ε, CD3ζ, IL-1RA, and IL-18R increased exponentially with increasing abundance of IFN-γ mRNA across first four V72%,32° glands (Figure 14). Similar to IFN-γ, mRNA, the abundance of IL-18R mRNA decreased exponentially as the abundance of IL-10 mRNA increased across the next five glands. While the abundances of mRNAs for IFN-γ and IL-18R decreased, the abundances of mRNAs for CCL4, CD3ε, CD3ζ and IL-1RA remained associated with each other. This sequence of associations suggests that: 1) the TH1/NKT reminiscent cells engaged in crosstalk with a network comprising epithelial cells expressing mRNAs for CCL2 and CCL4, MMΦDC lineage cells, and, perhaps, additional cell types, expressing mRNAs for TNF-α, CD80, CD86, IL-1RA and MMP-9; and 2) elements of this network persisted as negative crosstalk associated with increasing levels of IL-10 mRNA expression suppressed expression of mRNAs for IFN-γ and IL-18R

Figure 14.

Relationships between the abundances of selected transcripts and the abundances of mRNAs for IL-10 and IFN-γ in glands from group V72%,32°. Increasing abundances of IFN-γ mRNA across the first four glands were associated with increases in the abundances of mRNAs for IL-18R, TNF-α, IL-1RA, CD3ε, CD3ζ, CCL4, and CCL2 and with increases in the number of T cells, marked by RTLA. Increasing abundances of IL-10 mRNA across the next five glands were consistent with increasing abundances of core, adaptive-reactive network transcripts, e.g., CD8 mRNA and associations with the abundances of mRNAs for iNOS, CD1d, and IL-17A, as well as with mRNAs for CD4,CD25, MHC II, IL-4, and BAFF. Abundances of transcripts in gland V72%,32°01.OD were omitted from the regression analyses to reduce the possibility of type 1 or type 2 errors. Like the abundance of IFN-γ mRNA (Figure 13.A), the abundance of IL-17A mRNA in gland V72%,32°01.OD, was considerably higher than projected by the linear regressions; this conclusion was confirmed by projections of multiple linear regressions. It may be noted that IL-17A mRNA abundances with gland V72%,32°01.OD included are strongly and significantly described by three-parameter exponential growth regression. According to such a model, the high abundance of IL-17A mRNA in gland V72%,32°01.OD would be a predictable development, rather than an emergent phenomenon.

Additional quantitative relationships indicate that the core, adaptive-reactive network received both positive crosstalk and negative crosstalk from the TH1/NKT-reminiscent-TNF-α network during both phases of its development in V72%,32°. While the abundances of mRNAs for IL-1α and IL-10 remained in similar proportions across V58%,17°, V61%,27°, V68%,37°, and V82%,29° (Supplemental Figure 1), the proportions were different in V72%,32°, where IL-1α mRNA was considerably more abundant and IL-10 mRNA considerably less abundant. These findings imply that crosstalk from the TH1/NKT-reminiscent-TNF-α network suppressed the core, adaptive-reactive network’s expression of IL-10 mRNA and augmented its expression of IL-1α mRNA.

9. Emergence of Novel Profiles in Glands V68%,37°03.OS and V72%,32°01.OD

Gland V68%,37°03.OS, the V68%,37° gland in which IFN-γ mRNA was most abundant, had a disproportionately high abundance of IL-10 mRNA (Figure 12.B). As noted above, a high abundance of IL-10 mRNA also coincided with high abundances of mRNAs for IFN-γ, PRL, and IL-4 mRNA in gland V72%,32°01.OD (Figure 14). The abundances of most of the other core, adaptive-reactive network transcripts in both glands remained in similar proportions as in the other glands of their respective groups. Moreover, glands V68%,37°03.OS and V72%,32°01.OD each contained notably fewer T cells than the other glands of their respective groups.

Despite their qualitative similarities, the profiles differed quantitatively. Most notably, IL-10 mRNA was 5.4-fold more abundant in gland V68%,37°03.OS, while IFN-γ mRNA was 13.5-fold more abundant in gland V72%,32°01.OD. The quantitative differences suggest that some additional source of IL-10 mRNA expression had emerged in gland V68%,37°03.OS and that some additional source of IFN-γ mRNA expression had emerged in gland V72%,32°01.OD. While IL-17A mRNA was associated with the core, adaptive-reactive network across the first nine V72%,32° glands, it was 1.9-fold more abundant than this association predicted in gland V72%,32°01.OD; this discrepancy suggests that an additional source of IL-17A mRNA expression had emerged coincidently with the additional source of IFN-γ mRNA expression. Thus, the profile in gland V72%,32°01.OD contradicts the TH1/TH17 paradigm as well as the TH1/TH2 paradigm; qualitatively; it appears reminiscent of IL-17+, IFN-γ+ γδ T cells found in mice.63

10. BAFF mRNA-Expressing Cells, the PRL-Mediated Epithelial-TH2 Network, and the PRL-Mediated Epithelial-TH1 Network

BAFF is typically expressed by MMΦDC lineage cells in immune inductive tissues, where it promotes B cell activation and proliferation. The abundance of BAFF mRNA could, like the abundance of IL-4 mRNA, be described as having increased exponentially as the abundance of PRL mRNA increased across the V68%,37° glands (Figure 12A). However, this description may obscure a more complex sequence of interactions. Across the first four glands, where the abundances of mRNAs for BAFF and IL-4 were near or below their median values, the abundance of BAFF mRNA was negatively associated with the abundance of IL-4 mRNA (ρ=−.961, P =.0386). These relationships imply that the PRL-mediated epithelial - TH2 network engaged in crosstalk with BAFF-expressing MMΦDC lineage cells; negative crosstalk between the program for IL-4 mRNA expression and the program for BAFF mRNA expression played out across the lower range of PRL mRNA abundances, but the negative crosstalk was abrogated across the higher range of PRL mRNA abundances, and positive crosstalk emerged. As positive crosstalk influencing BAFF mRNA expression may have operated both in gland V68%,37°03.OS and in gland V68%,37°02.OS, it would not have depended on the negative crosstalk to TH1/NKT-reminiscent cells that uniquely emerged in gland V68%,37°02.OS.

11. Crosstalk between the Core, Adaptive-Reactive Network and Other Cells and Networks in Glands V68%,37°02.OS and V68%,37°03.OS

The core, adaptive-reactive network developed independently as the PRL-mediated epithelial-TH2 network developed and TH1/NKT-reminiscent cells accumulated across the first four V68%,37° glands. The abundances of most of the core, adaptive-reactive network transcripts in glands V68%,37°02.OS and V68%,37°03.OS (except IL-10 mRNA, which, as noted above, was associated dually with the network and with an additional source in gland V68%,37°03.OS) remained in proportions similar to the proportions in the other V68%,37° glands (Figure 12.B). These associations imply that, like BAFF-expressing cells, the core, adaptive-reactive network engaged in positive crosstalk with the PRL-mediated epithelial - TH2 network in glands V68%,37°02.OS and V68%,37°03.OS.

12. Correlation Clusters Reminiscent of Immune Inductive Tissues

The role BAFF plays in B cell inductive tissue was noted above. Likewise, associations of CCL21 mRNA with mRNAs for CD4, CXCL13, CD3ε, and CD3ζ in V61%,27° were noted above to be reminiscent of immune inductive tissue. As also already noted, CCL21 mRNA was associated with mRNAs for CD3ζ, CCL28, and PRL in V58%,17°. In V68%,37°, CCL21 mRNA was associated with mRNAs for CD3ε and CD3ζ. In V82%,29°, CCL21 mRNA was associated with mRNAs for CD3ε and CCL28, as well as with the core, adaptive-reactive network transcripts. In V72%,32° (Supplemental Table 4, Figure 7), CCL21 mRNA sorted to a cluster that included mRNAs for IRF-1, IL-15, IL-18, LTβ, and E selectin, and this cluster engaged in crosstalk with the core, adaptive-reactive network, the TH1/NKT-reminiscent-TNF-α network, and cells expressing VCAM-1 mRNA. These associations indicate that apparently healthy lacrimal glands may contain cells which are capable of recapitulating characteristic functions of organized immune inductive tissues.

D. Associations between Environmental Variables and Network Functions

1. Empirical Descriptions

The median abundance of IL-6 mRNA (associated with the core, adaptive-reactive network) can be empirically described as having increased exponentially with exposure to increasing dryness (R2 = 0.997, P ≤.0001). This relationship is projected across the range of temperature exposures in Figure 15.A. With the caveat that data are not available for IL-18 mRNA in V58%,17° nor for lipophilin CL mRNA in V61%,27°, the median abundances of mRNAs for CCL21, IL-18, MMP-9, CCL28, and lipophilin CL can be empirically described as having increased exponentially with increasing exposure to increasing temperature (0.822 ≤ R2 ≤ 1.000, 0.0337 ≥ P ≥.0005). These relationships are projected across the range of dryness exposures in Figure 15.B.

Figure 15.

Relationships between abundances of selected transcripts and environmental dryness and high temperature. Median abundances and abundances in individual glands that appeared as outliers are presented. A. Abundances of transcript that could be described as changing with increasing exposure to dryness. B. Abundances of transcripts that could be described as changing with exposure to increasing temperature. Continuous surfaces represent the domains over which median abundances could be described as conforming to empirical exponential growth curves or heuristics. Discontinuities represent domains in which surfaces could not be projected because median abundances in one or more groups were augmented above or displaced below the values predicted by their respective heuristics. Smaller font indicates transcripts that behaved similarly to the plotted transcripts.

2. Exponential Growth Heuristics and Crosstalk

The exponential growth functions also are useful heuristics for describing relationships between transcripts’ abundances and the environmental variables that were not monotonic. Thus, abundances can be described as having been displaced from their heuristics’ predictions in one group or another. Most such cases coincided with the emergence of crosstalk between cells or networks. For example, the median abundance of PRL mRNA increased according to an exponential temperature heuristic, but it was augmented above the heuristic’s prediction in V58%,17° (Figure 15.B, Supplemental Figure 3). The median abundance of CD8 mRNA increased according to an exponential dryness heuristic, but, like the abundance of PRL mRNA, it was augmented above its heuristic’s prediction in V58%,17° (Figure 15.A, Supplemental Figure 2). The augmentation of PRL mRNA expression in V58%,17° coincided with the association of PRL mRNA in the correlation cluster that also comprised mRNAs for CD3ζ, CCL21, and CCL28 (Figure 4). The augmentation of CD8 mRNA expression coincided with the possible association of CD8 mRNA with CD25 mRNA in a network independent of the core, adaptive-reactive network (Section II.C.2).

Although median abundances of CCL21 mRNA could be empirically described as having increased exponentially with exposure to increasing temperature (Figure 15.B, Supplemental Figure 3), the value in V61%,27° fell perceptibly above the regression, and the value in V82%,29° fell perceptibly below the regression. Augmentation of CCL21 mRNA expression in V61%,27° coincided with an association with the TH3-reminiscent correlation cluster (Sections II.C.4 – II.C.5, Figure 5). Suppression of CCL21 mRNA in V82%,29° coincided with an interplay between positive crosstalk associated with the core, adaptive-reactive network and negative crosstalk associated with cells expressing mRNAs for IL-15 and IL-18.

The median abundances of mRNAs for IL-4, BAFF, and APRIL increased according to dryness heuristics but can be described as having been augmented above their heuristics’ predictions in V68%,37°; IL-4 mRNA can be described as also having been augmented above its heuristic’s prediction in V72%,32° (Figure 15.A, Supplemental Figure 2). The augmentation of the median abundances of mRNAs for IL-4 and BAFF in V68%,37° coincided with the high abundance of PRL mRNA (associated with the high temperature V68%,37° had experienced) and development of the PRL-mediated epithelial - TH2 network (Sections II.C.7 and II.C.10; Figure 6).

The median abundance of IL-10 mRNA increased according to an exponential dryness heuristic, but it was suppressed below its heuristic’s prediction in V72%,32. In contrast, the median abundances of mRNAs for CTLA-4, IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-2, CCL2, CCL4, MHC II, and TGF-β2, and the median number of RTLA+ cells also increased according to exponential dryness heuristics, but, like IL-4 mRNA, all were augmented above their heuristics’ predictions in V72%,32°° (Figure 15.A, Supplemental Figure 2). The median abundances of mRNAs for CD3ε, CD3ζ, and CXCL8 increased according to exponential temperature heuristics, but they, also, were augmented above their heuristics’ predictions in V72%,32° (Figure 15.B, Supplemental Figure 3). The median abundance of IFN-γ mRNA decreased with increasing dryness according to an exponential decay heuristic, but it was augmented markedly above its heuristic’s prediction in V72%,32° (Figure 15.A, Supplemental Figure 2). The displacements of the core, adaptive-reactive network transcripts and associated transcripts, IFN-γ mRNA, and mRNAs for CD3ε, CD3ζ, and CXCL8 coincided with crosstalk between the core, adaptive-reactive network, the PRL-mediated epithelial - TH2 network, and the TH1/NKT-reminiscent - TNF-α network (Section II.C.7 – II.C.8, Figure 7).

III. HOW DETERMINED, ADAPTIVE NETWORK RESPONSES MAY LEAD TO DIVERSE IMMUNOPATHOLOGICAL STATES

The new findings and analyses reported above introduce the concept that, at least by early adult life, each lacrimal gland has become a dynamic system comprising immune cells that engage in crosstalk with each other and with epithelial cells under the influences of physiological signals related to environmental dryness, high temperature, and perhaps also low temperature. As will be discussed in this section, several of the networks may have adaptive value but also may be antecedents of different types of chronic immunopathological infiltrate, with diverse impacts on the glands’ physiological function.

A. Possible Adaptive Value of the Core Network and of TH2-Reminiscent Cells

Both the core, adaptive-reactive network and at least one of the cell types (TH2-reminiscent cells) with which it engages in positive crosstalk may have adaptive value in opposing TH1 cell-mediated autoimmune responses. Certain regulatory MMΦDC lineage cells exert their influences through IL-4, which suppresses IFN-γ expression. IL-10 and IL-17A also suppress IFN-γ expression. IL-10 is, like IL-4, expressed by TH2 cells, and it also is expressed by TR1 cells, regulatory B cells, and regulatory MMΦDC cells. IL-17A is commonly associated with inflammatory pathogenesis, as it increases expression of IL-1 and of various chemokines, but it also is well known to suppress IFN-γ expression. Foxp3+ cells, presumed to be regulatory T cells, are present in murine lacrimal glands,64 but their phenotypes have not yet been characterized. In gland V68%,37°02.OS, a high level of IL-4 mRNA expression was associated with abrogation of PRL-associated support for IFN-γ mRNA expression. The core, adaptive-reactive network accounted for most of the IL-10 mRNA expression in V61%,27°, V68%,37°, V72%,32°, and V82%,29° and also for most of the IL-17A mRNA expression in V72%,32° and V82%,29°. Increasing abundances of IL-10 mRNA were significantly associated with decreasing abundances of IFN-γ mRNA in V61%,27° and in a subset of the V72%,32° glands. Moreover, IFN-γ mRNA was not detectable in V82%,29°, where median abundances of mRNAs for IL-10 and IL-17A were highest.

1. Counter-regulatory, Anticipatory, or Corollary?

It would be plausible to hypothesize that the core, adaptive-reactive network developed as a counter-regulatory response to desiccation-induced inflammation of the cornea and conjunctiva. It appears that TH1 cells effect the transformation from an innate inflammatory ocular surface response to an autoimmune process, and autoreactive, pathogenic TH1 cells can be detected in the draining lymph nodes. If such cells traffic to the lacrimal glands, they would have the potential to propagate the inflammatory process.65 The theoretical prediction that they provoke a counterregulatory activation of the core, adaptive-reactive network is consistent with the finding that the network engages in crosstalk with other cells and networks in other settings. However, if the activity of the core, adaptive-reactive network in V82%,29° had increased reactively, in response to the arrival of increasing numbers of TH1 cells, it appears to have maintained itself and developed further even after it had effectively suppressed TH1 activity.

3. Physiological Signals Related to Dryness

It also would be plausible to hypothesize that the core, adaptive-reactive network is activated by autonomic secretomotor neurotransmission triggered by activation of cold receptors or nocioceptors in the cornea and conjunctiva. Findings from preliminary experiments with an ex vivo acinar cell model are consistent with a neurally-mediated mechanism, as the β-adrenergic receptor agonist, isoproterenol, increases expression of mRNAs for CCL2 and CCL4,66 both of which recruit both T cells and MMΦDC lineage cells. The findings in Figure 2 both confirm that epithelial cells express mRNAs for CCL2 and CCL4 in vivo and also indicate that acinar cells are the predominant cell type expressing CCL2 mRNA. Like the core, adaptive-reactive network transcripts, the abundances of mRNAs for CCL2 and CCL4 could be described as having increased according to exponential dryness heuristics. They were significantly associated with the core, adaptive-reactive network transcripts in V82%,29°, and hypothetical associations with the network in other settings cannot be rejected (Table 1). Moreover, mRNA for the primary CCL4 receptor, CCR5, is one of the core, adaptive-reactive network transcripts.

In view of findings suggesting that meibomian gland dysfunction leading to increased evaporation and tear fluid hyperosmolarity frequently precedes signs of aqueous insufficiency,10–13 it should be noted that cold receptors would be activated by the heat loss of evaporation,67 thus eliciting a response that is anticipatory rather than counter-regulatory. However, a neurally-mediated mechanism can be predicted to also involve negative crosstalk, as the muscarinic cholinergic receptor agonist, carbachol, attenuates, but does not entirely abrogate, the ability of isoproterenol to increase expression of mRNAs for CCL2 and CCL4.66 The median abundances of mRNAs for CCL2 and CCL4 were elevated above their heuristics’ predictions in V72%,32°, and the abundances of both also were elevated in glands V61%,27°02.OS, V68%,37°02.OS, and V72%,32°01.OD—three of the four glands that appeared as outliers. Therefore, it would be plausible to predict that epithelial cells expressing CCL2 and CCL4 contributed to the crosstalk which promoted development of the core adaptive-reactive network in each setting.

3. Physiological Signals Related to High Temperature

It is not a straightforward task to formulate hypotheses for how physiological signals related to high temperature might elicit increases in the expression of such transcripts as PRL mRNA, CCL21 mRNA, IL-18 mRNA, and lipophilin CL mRNA. The abundances of the various high temperature-responsive transcripts appeared to increase concurrently with each other, but not coordinately. The signals that elicit these increases might include hormones associated the physiological heat stress response, most notably PRL.68 Of the transcripts that became more abundant in association with exposure to increasingly high temperature, only mRNAs for PRL and lipophilin CL have so far been clearly localized to epithelial cells (Figure 2). However, our preliminary studies with ex vivo models have not shown that ambient PRL levels consistently influence expression of either transcript (unpublished data). The failure to demonstrate a consistent influence in ex vivo models does not necessarily preclude a role for hormonal prolactin, however, as responses may be mediated by complex local signaling interactions not yet reconstituted in the models. A plausible-seeming hypothesis, yet to be tested, is that hormonal PRL influences resident immune cells that engage in crosstalk with the epithelial cells and lead the epithelial cell to up-regulate expression of PRL and lipophilin CL.

B. TH3-Reminscent Cells and Constitutive, Adaptive Immunoregulation

In addition to TH2-reminiscent cells and IL-10-expressing cells of the core adaptive-reactive network, the TH3-reminiscent cells (whose signature correlation cluster was detected in V61%,27° and V68%,37°) also can be predicted to exert regulatory influences in the lacrimal gland. The abundance of TGF-β1 mRNA did not vary in a simple relationship with dryness or temperature across the five groups of rabbits. As variations in the numbers of other cells (TH1/NKT-reminiscent cells in V72%,32° and TH2-reminiscent cells in V82%,29°) accounted for most of the variation in CD4 mRNA abundance, the failure to detect the TH3-reminiscent signature in other groups cannot be taken to imply that TH3-reminiscent cells were absent from group V72%,32° and group V82%,29°. Rather, it is more likely that TH3-reminiscent cells were present constitutively.

C. Crosstalk and Inflammatory Pathogenesis

Crosstalk between the core, adaptive-reactive network and other cells and networks was associated with obvious immunopathological changes in gland V61%,27°02.OS. Interestingly, the pathological process appeared not to involve IFN-γ, as IFN-γ mRNA expression was suppressed in association with the high level of IL-10 mRNA expression in that gland (Figure 13.B). The relationships between the numbers of RTLA+ cells and abundances of mRNAs for TGF-β1, IL-4, and CD4 across the V61%,27° glands (Figure 10) support estimates that TH3-reminiscent cells and TH2-reminiscent cells accounted for roughly similar numbers of T cells in gland V61%,27°02.OS. In contrast, T cells associated with the core, adaptive-reactive network can have accounted for only a small proportion of the total number of T cells in gland V61%,27°02.OS. It is plausible to hypothesize that ongoing, exponential accumulation of TH2-reminiscent cells drove development of the pathological process. The competing hypothesis, that some adventitious event, such as infection or trauma triggered the process, also deserves consideration. In either case, it also is plausible that the incipient process elicited a reactive increase in the activity of the core, adaptive-reactive network, and that the network, in turn, contributed mitogenic cytokines (IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-2, and IL-6) that accelerated the process.

D. Crosstalk Promoting Elements of Ectopic Immune Inductive Tissue