Significance

Auxin is the central hormone that governs diverse developmental processes in plants. Auxin response is regulated by auxin response transcription factor (ARF) and Aux/IAA transcriptional repressor. ARF and Aux/IAA form homo-oligomers and also hetero-oligomers for transcriptional regulation of auxin-response genes. Mechanistic understanding of how ARF and Aux/IAA change their association states is not well established. This work reports, to our knowledge, the first structure of the oligomerization domain of IAA17, and describes the key determinant that dictates the switch between homo- and hetero-oligomers. While Aux/IAA and ARF use a common scaffold and interface for homotypic and heterotypic associations, the charge composition at the interface determines the affinity and the oligomerization states. Based on the results, we propose a refined model of auxin-induced transcriptional regulation.

Keywords: auxin, auxin response factor, Aux/IAA, NMR spectroscopy, protein structure

Abstract

Auxin is the central hormone that regulates plant growth and organ development. Transcriptional regulation by auxin is mediated by the auxin response factor (ARF) and the repressor, AUX/IAA. Aux/IAA associates with ARF via domain III−IV for transcriptional repression that is reversed by auxin-induced Aux/IAA degradation. It has been known that Aux/IAA and ARF form homo- and hetero-oligomers for the transcriptional regulation, but what determines their association states is poorly understood. Here we report, to our knowledge, the first solution structure of domain III−IV of Aux/IAA17 (IAA17), and characterize molecular interactions underlying the homotypic and heterotypic oligomerization. The structure exhibits a compact β-grasp fold with a highly dynamic insert helix that is unique in Aux/IAA family proteins. IAA17 associates to form a heterogeneous ensemble of front-to-back oligomers in a concentration-dependent manner. IAA17 and ARF5 associate to form homo- or hetero-oligomers using a common scaffold and binding interfaces, but their affinities vary significantly. The equilibrium dissociation constants (KD) for homo-oligomerization are 6.6 μM and 0.87 μM for IAA17 and ARF5, respectively, whereas hetero-oligomerization reveals a ∼10- to ∼100-fold greater affinity (KD = 73 nM). Thus, individual homo-oligomers of IAA17 and ARF5 spontaneously exchange their subunits to form alternating hetero-oligomers for transcriptional repression. Oligomerization is mainly driven by electrostatic interactions, so that charge complementarity at the interface determines the binding affinity. Variable binding affinity by surface charge modulation may effectively regulate the complex interaction network between Aux/IAA and ARF family proteins required for the transcriptional control of auxin-response genes.

The plant hormone auxin regulates various developmental processes in plants, including morphogenesis, organogenesis, apical dominance, vascular differentiation, and tropic responses to environmental stimuli such as light and gravity (1, 2). Auxin signaling is mediated by Aux/IAA repressor proteins that bind to auxin response factors (ARFs) for transcriptional regulation (3). In the absence of auxin, Aux/IAA associates with ARF and represses its transcriptional activity. When auxin is released, Aux/IAA interacts with the F-box protein Transport Inhibitor Response 1 (TIR1) that assembles into an SKP1−Cullin−F-box-type E3 ligase complex that causes Aux/IAA degradation (4, 5). Elevated auxin levels are thus detected by reductions in cellular Aux/IAA levels, resulting in derepression of ARF-mediated gene expression.

The Arabidopsis thaliana genome encodes 29 Aux/IAA and 23 ARF proteins. Aux/IAA is comprised of four conserved domains I, II, III, and IV. Domain I is involved in transcriptional repression and recruits the transcriptional corepressor TOPLESS (TPL) protein (6), whereas domain II interacts with the auxin coreceptor TIR1 and directs proteasome-mediated degradation of Aux/IAA (7). Domains III and IV together mediate protein-protein interactions between Aux/IAA and ARF proteins (8, 9). ARF consists of an N-terminal DNA binding domain, a variable middle region that functions as a transcriptional activator or a repressor, and C-terminal domain III−IV that mediates protein−protein interactions with Aux/IAA. The C-terminal domains III−IV exhibit high sequence homology across the Aux/IAA and ARF family proteins, and promote both their homotypic (Aux/IAA−Aux/IAA or ARF−ARF) and heterotypic (Aux/IAA−ARF) associations. It has been generally known that the association of domain III−IV between Aux/IAA and ARF is responsible for the transcriptional repression (10, 11), but what controls their association states remains poorly understood.

Although the interaction between Aux/IAA and ARF is of great biological significance, a detailed structural characterization of domain III−IV has been hampered owing to its aggregative tendency to form heterogeneous oligomers. Previous analysis of multiple sequence alignments predicted a structural link between domain III−IV and the Phox and Bem 1 (PB1) domain (12). The PB1 domain, a protein interaction module involved in diverse biological processes, forms a heterodimer in a front-to-back manner via well-conserved acidic and basic residues at the interfaces (13). The essential residues at the dimer interface of PB1 were highly conserved in domain III−IV of Aux/IAA and ARF family proteins, suggesting that they would be important for oligomerization. Indeed, mutation of the conserved residues has recently allowed for determination of the crystal structure of domain III−IV in ARF family proteins (14, 15). Here we report, to our knowledge, the first solution structure of domain III−IV of Arabidopsis Aux/IAA17 (IAA17), and characterize the molecular interactions involved in its homotypic and heterotypic associations. Domain III−IV of IAA17 adopts a compact β-grasp fold with a highly dynamic helix that appears to be unique among the Aux/IAA family proteins. The binding thermodynamics reveal a higher affinity for the IAA17−ARF5 heterodimer than for individual homodimers. Based on structural and thermodynamic analyses, we propose a refined model for transcriptional control during the auxin response.

Results

Domain Design and Structure Determination.

Domain III−IV of wild-type IAA17 (IAA17III−IV) oligomerized in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. S1A). The 1H-15N HSQC spectrum of IAA17III−IV revealed a small set of broad signals owing to the large size and chemical exchanges arising from oligomerization (Fig. S2A). Based on the sequence homology between IAA17III−IV and PB1 domains, we selected a highly conserved Lys114 residue on the basic surface, and Asp183 and Asp187 residues on the acidic surface for charge-neutralizing mutations. A K114M mutation (IAA17M1) or D183N/D187N mutation (IAA17M2) resulted in an exclusively monomeric protein (Fig. S1B). HSQC spectra of monomeric IAA17M1 and IAA17M2 showed well-dispersed signals, which is typically observed in folded proteins (Fig. S2 B and C). We determined the solution structure of monomeric IAA17M2 using NMR spectroscopy. Backbone and side chain assignments were obtained using a suite of 3D heteronuclear correlation NMR spectroscopy. 3D 13C-separated NOE and 15N-separated NOE restraints were used for the structure calculation using the Xplor-NIH program (16). Residual dipolar couplings (RDCs) of IAA17M2 were measured in 6.5% neutral gel alignment medium. The structure was determined using 2,141 NMR restraints including 1,858 experimental NOE restraints, 183 dihedral angle restraints, 51 backbone 1DNH RDC restraints, and 49 hydrogen bonding restraints (Table 1).

Table 1.

Restraints and structural statistics of IAA17M2

| Experimental restraints | <SA>* |

| Nonredundant NOEs | 1858 |

| Dihedral angles, ϕ/ψ/χ | 84/84/15 |

| Hydrogen bonds | 49 |

| Residual dipolar coupling, 1DNH | 51 |

| Total number of restraints | 2,141 (19.3 per residue) |

| rms deviation from experimental restraints | |

| Distances (Å) (1858) | 0.053 ± 0.002 |

| Torsion angles (°) (183) | 0.87 ± 0.07 |

| Residual dipolar coupling R-factor (%)† | |

| 1DNH (%) (51) | 2.9 ± 0.5 |

| rms deviation from idealized covalent geometry | |

| Bonds (Å) | 0.004 ± 0 |

| Angles (°) | 0.50 ± 0.03 |

| Impropers (°) | 0.51 ± 0.02 |

| Coordinate precision (Å)*‡ | |

| Backbone | 0.48 ± 0.08 |

| Heavy atoms | 0.98 ± 0.17 |

| Ramachandran statistics (%)ठ| |

| Most favorable regions | 91.5 ± 1.0 |

| Allowed regions | 8.5 ± 1.0 |

For ensemble of the final 20 simulated annealing structures.

The magnitudes of axial and rhombic components of the alignment tensor were −11.5 Hz and 0.55, respectively.

Residues 112−217, excluding residues 150−178 with internal motions.

Calculated using the program PROCHECK (33).

Structure and Dynamics of IAA17M2.

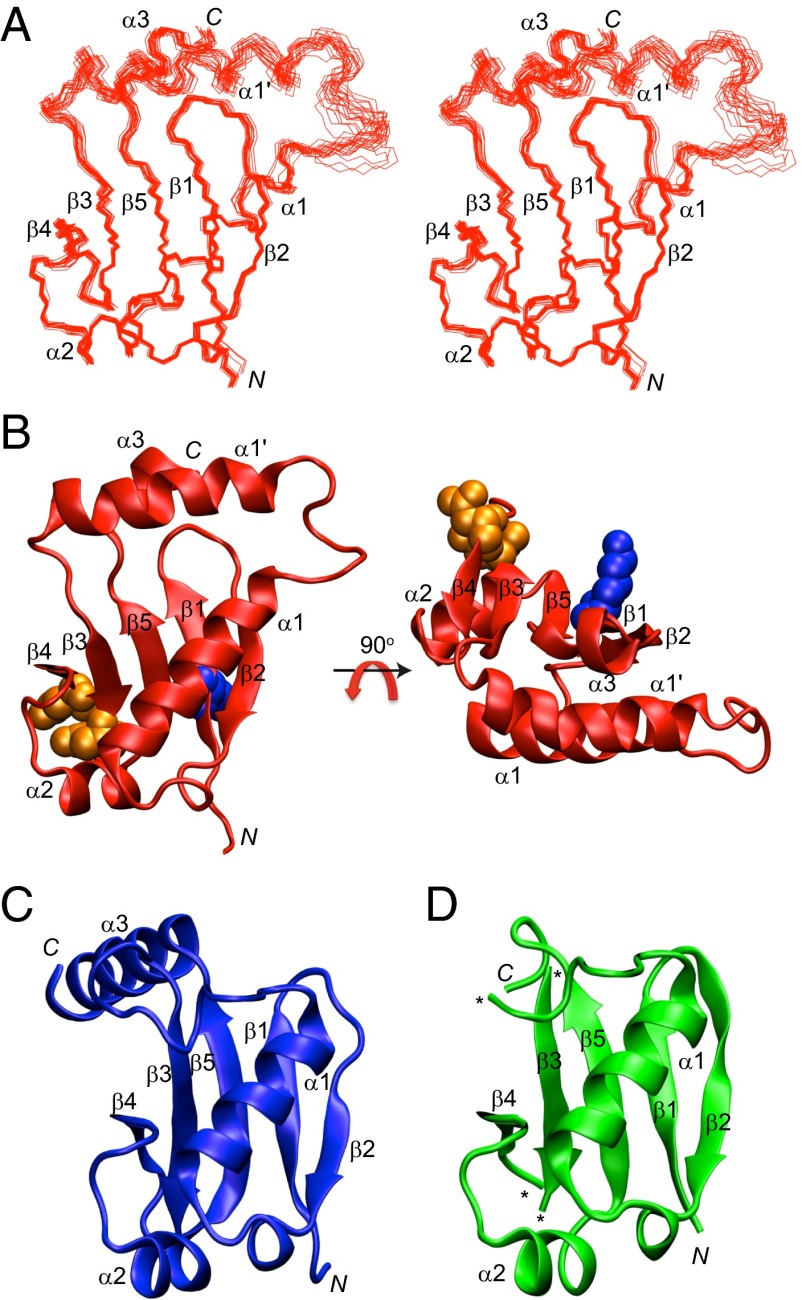

IAA17M2 is comprised of five β strands and four α helices, which form a PB1-like β-grasp fold. Superposition of the backbone atoms for the ensemble of the final 20 simulated annealing structures of IAA17M2 demonstrates that the secondary structures are well ordered except for the α1′ and α3 helices (Fig. 1A). Domain III forms a β1−β2−α1 fold as an antiparallel β sheet, whereas domain IV forms a β3−β4−α2−β5−α3 fold as an antiparallel β sheet. β1 of domain III and β5 of domain IV form a parallel β sheet, joining the two domains into a compact β-grasp fold (Fig. 1B). The conserved residues Asp183 and Asp187 are located on the flank of the β sheet, and point away from the other conserved Lys114 residue (Fig. 1B). The overall structural architecture of IAA17M2 is similar to that of the domain III−IV of ARF5 (ARF5III−IV) and ARF7 (ARF7III−IV), except for the new α1′ helix in IAA17M2 (Fig. 1 C and D) (14, 15). In Arabidopsis thaliana, approximately half of the Aux/IAA family proteins contain a long insert sequence between domains III and IV, which varies in lengths and amino acid compositions, whereas none of the ARF family proteins carries the insert sequence (Fig. S3). Notably, IAA17 contains the longest insert sequence with more than 15 extra residues compared with ARF5 and ARF7. The insert region forms the α1′ helix connecting α1 of domain III and β3 of domain IV (Fig. 1B). Unexpectedly, most of the α1′ helix manifested fast motions in the picosecond to nanosecond time scale, based on the 15N relaxation data of the backbone amide groups. Reduced 1H−15N heteronuclear NOE data as well as increased 15N R1 and decreased 15N R2 relaxation data collectively indicated that the α1′ helix and its preceding loop were highly mobile (Fig. S4). To investigate if the dynamic α1′ helix affects folding or oligomerization of IAA17M2, we prepared IAA17M2(Δ159−169) that removed the α1′ helix. When the HSQC spectra were compared between IAA17M2 and IAA17M2(Δ159−169), the backbone amide chemical shifts were mostly identical except for the missing residues from the α1′ helix (Fig. S5). This result indicates that IAA17III−IV adopts the same β-grasp scaffold without the insert helix, and also that the α1′ helix is not tightly packed on to the β-grasp fold. We then measured the binding affinities of the mutant for the homodimer (IAA17:IAA17) and the heterodimer (IAA17:ARF5) formation (see next sections for details). The binding affinities for the dimerization little changed by the absence of the α1′ helix (Fig. 2 and Fig. S6). Taken together, our results imply that the insert α1′ helix is not likely critical for the proper folding of IAA17M2, and for the formation of a homodimer and a heterodimer with ARF5.

Fig. 1.

Structures of domain III−IV of IAA17, ARF5, and ARF7. (A) Superposition of the backbone atoms of the final 20 simulated annealing structures of IAA17M2. (B) Front and top views of the solution structure of IAA17M2 as a ribbon diagram representation. The conserved residues Lys114 (blue), Asp183 and Asp187 (orange) are shown as a space-filling representation. (C and D) Crystal structure of ARF5III−IV (PDB ID 4CHK; ref. 14; C), and ARF7III−IV (PDB ID 4NJ7; ref. 15; D) as a ribbon diagram representation. The asterisks denote the missing residues in the coordinate.

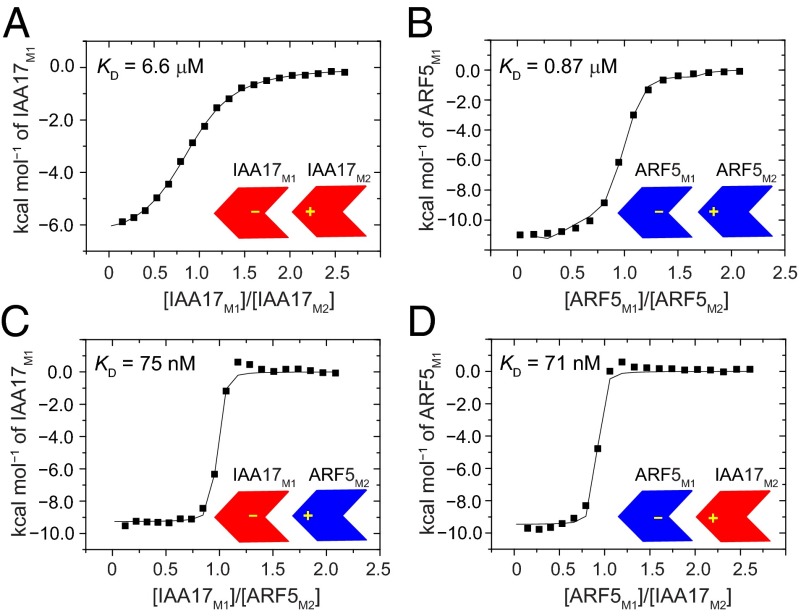

Fig. 2.

ITC of the homodimer and heterodimer formation of IAA17III−IV and ARF5III−IV. Integrated heats of injection (solid squares) and the least squares best fit curves (black line), derived from a simple one-site binding model for the titration between IAA17M1 and IAA17M2 (A), ARF5M1 and ARF5M2 (B), IAA17M1 and ARF5M2 (C), and ARF5M1 and IAA17M2 (D). The thermodynamic parameters for each complex formation are listed in Table 2.

Homotypic Oligomerization of IAA17.

The IAA17 mutants in this study were designed to remove either a positive charge (IAA17M1) or negative charges (IAA17M2), so that individual mutants alone behaved as a monomer but together effectively formed a dimer (Fig. S1B). We measured the equilibrium dissociation constant (KD) for the dimerization between IAA17M1 and IAA17M2 using isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC), and the KD value was obtained as 6.6 μM (Fig. 2A and Table 2). Size exclusion chromatography (SEC) of wild-type IAA17III−IV revealed an increasing oligomer size upon concentration, such that 1.5, 2.0, and 3.7 appeared as average subunit numbers of the oligomer ensemble at 3 μM, 12 μM, and 103 μM, respectively (Fig. S1A). This indicates that wild-type IAA17III−IV can use both positive and negative interfaces simultaneously to form oligomers extending in a front-to-back manner. We used a numerical analysis based on a monomer−oligomer equilibrium model to determine the populational distribution of the oligomers at a given concentration. Briefly, we assumed that a single equilibrium constant (KD = 6.6 μM) governs the entire exchange process in the oligomer ensemble, and compared the experimental average subunit numbers with those calculated from equilibrium oligomer populations (see Materials and Methods for detail). The experimental oligomer sizes of IAA17III−IV at 103 μM could be reproduced using an eight-state model (equilibria between a monomer and oligomers up to an octamer, Table S1). The eight-state model provided the monomer and oligomer populations at varying concentrations as follows: IAA17III−IV at 1 μM was largely monomeric (88%) with a dimer (11%) and higher-order oligomers (1%) as minor species. At 10 μM, a monomer (54%) coexisted with a dimer (25%) and higher-order oligomers (21%). Lastly, at 100 μM, the monomer population (21%) was reduced, and the dimer (18%) and higher-order oligomers (61%) appeared as predominant species. In summary, IAA17 is predicted to be largely monomeric at concentrations below 1 μM, whereas oligomers of varying sizes increase at higher concentrations.

Table 2.

Thermodynamic parameters for the homodimer and heterodimer formation between domains III−IV of IAA17 and ARF5 obtained by isothermal titration calorimetry at 25 °C

| Description M1 + M2 | KD (μM) | ΔG (kcal/mol) | ΔH (kcal/mol) | −TΔS (kcal/mol) |

| IAA17 + IAA17 | 6.6 ± 0.3 | −7.1 ± 0.0 | −9.7 ± 0.1 | 2.6 ± 0.1 |

| ARF5 + ARF5 | 0.87 ± 0.07 | −8.3 ± 0.0 | −11.1 ± 0.1 | 2.8 ± 0.1 |

| IAA17 + ARF5 | 0.075 ± 0.03 | −9.7 ± 0.2 | −9.3 ± 0.1 | −0.4 ± 0.2 |

| ARF5 + IAA17 | 0.071 ± 0.05 | −9.8 ± 0.4 | −9.5 ± 0.2 | −0.3 ± 0.4 |

Titrations were carried out using mutant proteins that removed either the positively charged interaction surface (M1 mutant) or the negatively charged interaction surface (M2 mutant).

We note that KD measurements using the mutants are based on an assumption that mutations did not influence the binding at interaction surfaces on the opposite side. Also, numerical analysis used to characterize the oligomerization states implicitly assumes that association extending IAA17 oligomers does not exhibit positive or negative cooperativity. To address the validity of the underlying assumptions, we examined the interaction between wild-type IAA17III−IV and IAA17M1 (or IAA17M2). The KD values revealed 5.9 ± 1.7 μM and 5.8 ± 0.9 μM for IAA17M1 and IAA17M2, respectively, which remarkably well reproduced the KD value (6.6 ± 0.3 μM) between IAA17M1 and IAA17M2. This result indicates that mutations introduced into IAA17M1 or IAA17M2 little altered the binding of the interaction surface. We further monitored the binding between wild-type IAA17III−IV and the mutants at varying concentrations of IAA17III−IV, and the KD values remained constant. Given that IAA17III−IV forms an ensemble of oligomers that change sizes and populations by concentration, the uniform binding affinity between heterogeneous oligomers and the mutants suggests an absence of apparent cooperativity. Taken together, we propose that the single KD value measured between IAA17M1 and IAA17M2 represents the association events during IAA17 oligomerization.

Interaction Between IAA17 and ARF5.

Mutations that prevented the oligomerization of IAA17III−IV similarly produced a monomeric form of ARF5III−IV. A single mutant, K797A (ARF5M1), and a double mutant, D847N/D851N (ARF5M2), produced monomeric proteins (Fig. S7). Using the ARF mutants, we measured the binding affinity of the ARF5M1:ARF5M2 homodimer as well as the heterodimer between IAA17 and ARF5 using calorimetry. Note that the heterodimer can form in two different ways (IAA17M1:ARF5M2 and ARF5M1:IAA17M2) depending on which protein employs the positive interface for the complex formation. The KD values for the ARF5 homodimer formation was 0.87 μM, an eightfold stronger binding than that of the IAA17 homodimer (Fig. 2B and Table 2). The affinity for the heterodimer formation was stronger than that of both homodimers, with the KD values measured as 75 nM and 71 nM for IAA17M1:ARF5M2 and ARF5M1:IAA17M2 complexes, respectively (Fig. 2 C and D and Table 2). Thus, the affinity of the heterodimer was 90 times higher than that of the IAA17 homodimer, and 12 times higher than that of the ARF5 homodimer.

We note that cysteines in IAA17 and ARF5 were mutated to alanines or serines in the calorimetric measurement to avoid the use of reducing agents. Cys203 of IAA17 was mutated to an alanine, since the side chain was buried in the hydrophobic core region in the solution structure. As Cys203 was conserved among half of Aux/IAA family proteins (Fig. S3), we used IAA17M1 and IAA17M2 without C203A mutations to confirm the binding. The measured KD value (6.3 ± 0.3 μM) was very similar to that of C203A mutants (KD = 6.6 ± 0.3 μM), validating that the cysteine mutation did not affect the interaction of IAA17. Three cysteine residue (Cys825, Cys866, and Cys869) of ARF5 were mutated to serines, because they were all exposed to solvents in the crystal structure (14). The cysteine residues varied widely among ARF family proteins, and none of them contributed to the positive or negative binding surface in the crystal structure. Thus, it is most likely that that the cysteine mutations in this study little affected the interaction of ARF5.

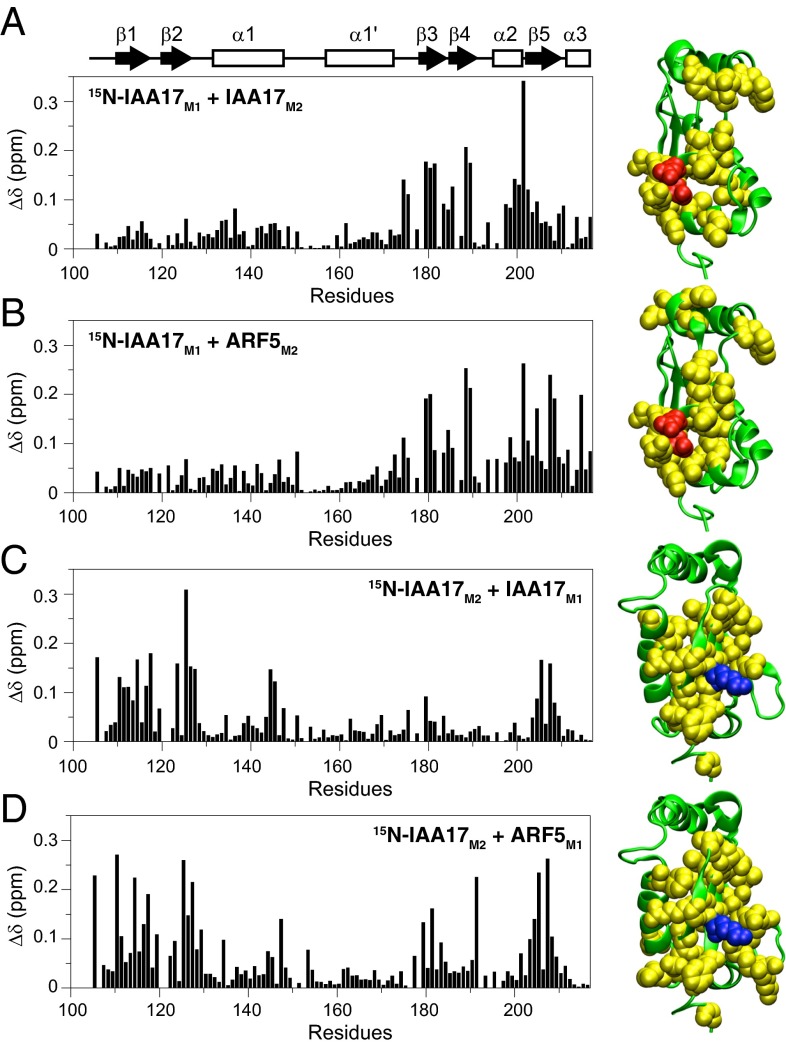

To understand the structural basis for the preferential heterodimer formation, we compared the binding interface of the homodimer with that of the heterodimer. 15N-labeled IAA17M1 titrated with IAA17M2 or ARF5M2 showed large chemical shift perturbations mainly in the β3−β4−α2 region that contained Asp183 and Asp187 (Fig. 3 A and B). In addition, 15N-labeled IAA17M2 titrated with IAA17M1 or ARF5M1 showed large chemical shift perturbations mostly in the β2−β1−β5 region that contained Lys114 (Fig. 3 C and D). The similar chemical shift perturbation profiles indicate that IAA17 used largely the same binding interfaces for the homodimer formation, and for the heterodimer formation with ARF5. Previously published crystal structures of ARF5III−IV and ARF7III−IV contained oligomers extending in a front-to-back manner (14, 15). The binding interface of the ARF5III−IV oligomer could be mapped on to IAA17III−IV based on the sequence alignment (Fig. 4, Upper). Notably, the interfacial residues derived from the crystal structure largely overlapped with residues that exhibited large chemical shift perturbations. This suggests that the homo-oligomer of IAA17III−IV and the hetero-oligomer between IAA17III−IV and ARF5III−IV adopt a similar structural arrangement as was observed in the crystal structure. When the binding interface of IAA17 was extrapolated from the crystal structure of ARF5, positive surface was formed by Lys114, Arg124, Lys125, Arg205, and Arg207, and negative surface was formed by Asp183, Asp185, Asp187, and Asp193. The negatively charged residues were highly conserved among Aux/IAA and ARF family proteins (Fig. S3), suggesting that they provide key electrostatic interactions for both homotypic and heterotypic associations. Lys114 and Arg124 at the positive surface were similarly well conserved, whereas Lys125, Arg205, and Arg207 were mostly conserved in Aux/IAA family proteins, but not in ARF family proteins. In addition, interfacial residues surrounding the highly conserved region revealed variances: they were generally well conserved between Aux/IAA family proteins, but exhibited significant variations between ARF family proteins. The biased sequence homology may explain previous observations that Aux/IAA−Aux/IAA interactions appeared to be less specific compared with ARF−ARF or Aux/IAA−ARF interactions (8, 17).

Fig. 3.

Weighted average 1HN/15N chemical shift perturbation [Δδ = ([(ΔδHN)2 + (ΔδN)2/25]/2)1/2] as a function of residue number upon homodimer and heterodimer formation between 15N-IAA17M1 and IAA17M2 (A), 15N-IAA17M1 and ARF5M2 (B), 15N-IAA17M2 and IAA17M1 (C), and 15N-IAA17M2 and ARF5M1 (D). The structure of IAA17M2 is shown in green as a ribbon diagram representation. Residues with Δδ > 0.08 are shown in yellow with the conserved Lys114 in blue, and Asp183 and Asp187 in orange as a space-filling representation.

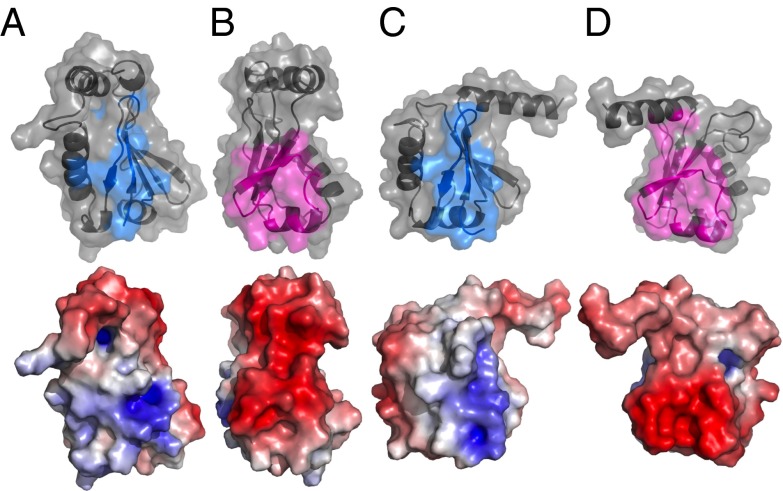

Fig. 4.

Molecular surface representations of the positive binding interface (A) and negative binding interface (B) of IAA17III−IV and the positive binding interface (C) and negative binding interface (D) of ARF5III−IV. (Upper) The ribbon diagram representation with a transparent molecular surface, where the interfacial residues are colored in cyan and magenta. The interfacial residues are obtained from the crystal structure of the ARF5III−IV oligomer using the PDBePISA program (34) (http://pdbe.org/pisa), and mapped on to the IAA17III−IV based on the sequence alignment. (Lower) The molecular surfaces of IAA17III−IV and ARF5III−IV color-coded by electrostatic potential, ±7 kT. The orientations for the positive and negative molecular surfaces are kept the same as those presented in Fig. 3.

We examined in detail the electrostatic potential of interaction surfaces between IAA17III−IV and ARF5III−IV. Both IAA17III−IV and ARF5III−IV exhibited distinct positive and negative surfaces at the interfaces, but the charge density and distribution were quite different. IAA17III−IV exhibited highly localized positive charges near Lys114, whereas it exhibited a wide distribution of dense negative charges on the opposite side (Fig. 4 A and B, Lower). In contrast, ARF5III−IV presented a relatively dispersed distribution of positive charges near Lys797 (the Lys114 counterpart in ARF5), but highly concentrated negative charges on the opposite side (Fig. 4 C and D, Lower). The heterodimer is thus expected to achieve favorable electrostatic interactions compared with individual homodimers due to an optimal combination of oppositely charged interfaces.

Discussion

It is known that the interplay between ARF and Aux/IAA repressor plays a key role in the regulation of auxin-response gene expression (18). The structural mechanism underlying the transcriptional regulation, however, has remained poorly understood. We have shown that domains III−IV of IAA17 and ARF5 share the same PB1-like β-grasp folds, differing mainly in the long insertion sequence of IAA17 that adopts a dynamic helical conformation. It is puzzling that deletion of the insertion helix little perturbed the structure or interactions of IAA17 in this study, although it represents the major difference between domains III−IV of IAA17 and ARF family proteins. A full understanding of functional implications of the insertion would require systematic binding studies that use an IAA17 mutant without the insertion and its potential partner proteins including Aux/IAA, ARF, etc. Further, in vivo experiments would be crucial to judge upon the relevance of the insertion for IAA17 function. Nevertheless, it is tempting to speculate that the insertion helix may modulate the binding specificity of Aux/IAA, considering the diversity of insertion sequences and sizes. Functional significances of insertion loops are well known in the protein kinase family, where the insertions provide specific interactions for substrate binding, distinguishing between different kinases (19). The fact that the insertion of IAA17 adopts a mobile helix also adds weight to the speculation, as fast time-scale dynamics are often linked to biologically relevant interactions and functions (20, 21). Until more experimental evidences are accumulated, the question remains to be answered whether the insertions of Aux/IAA serve as the target recognition sites or merely survived as evolutionary vestiges.

The chemical shift perturbation profiles indicate that IAA17 employs largely the same binding interface for the Aux/IAA−Aux/IAA and the Aux/IAA−ARF interactions. The binding interfaces were consistent with the oligomer found in the crystal structure, suggesting that the homo- and hetero-oligomers would extend in a similar structural arrangement. We attribute the differences in the binding affinity to the charge content and composition at the interaction surfaces. Considering that the single and double mutations used in this study abolished the oligomerization of IAA17 and ARF5, the charge distribution at the interfaces is postulated to be critical for the association. We hypothesize that charge modulation at the interaction surface may be a general strategy to tailor the binding affinity between Aux/IAA and ARF family proteins without perturbing their complex structures. It is notable that equilibrium binding favors the heterodimer formation over individual homodimers, so that the repression of ARF5 by IAA17 is a thermodynamically downhill process. When auxin is depleted and IAA17 accumulates, formation of the higher-affinity hetero-oligomer is preferred for transcriptional repression. Upon auxin release and IAA17 degradation, the equilibrium shift re-establishes ARF5 homo-oligomers to resume transcriptional activation. It has been reported that the transcriptional regulation of auxin-response genes involves a complex network of interactions between over 50 Aux/IAA and ARF family proteins (17). Variable binding affinity by surface charge modulation may be effective to modulate the complex interaction network and regulate the transcriptional control of auxin-response genes.

Numerical analysis of IAA17 oligomerization revealed that IAA17 oligomers were in dynamic equilibrium determined by the protein concentration. We extended the analysis to predict the oligomerization state of IAA17 in cell. Comprehensive analysis of protein expression in budding yeast reported that the protein concentration in cell was ∼1 μM in average, ranging from 2 nM to 30 μM (22, 23). IAA17 (1 μM) is expected to populate a monomer (∼90%) and a dimer (∼10%). The monomer population decreases to ∼70% at 5 μM concentration of IAA17, and to ∼50% at 10 μM concentration of IAA17. IAA17 is not supposed to be highly abundant in cell, but the local concentration may fluctuate over a wide range, given the densely-packed and crowded cellular environment. Considering that IAA17 is rapidly expressed and accumulated upon the clearance of auxin from the cell, we speculate that the local concentration of IAA17 may transiently reach high enough to form oligomers. Formation of extended IAA17 oligomers bears potential benefits such as facilitated cellular trafficking of Aux/IAA into nucleus, and promoting target search for ARF proteins.

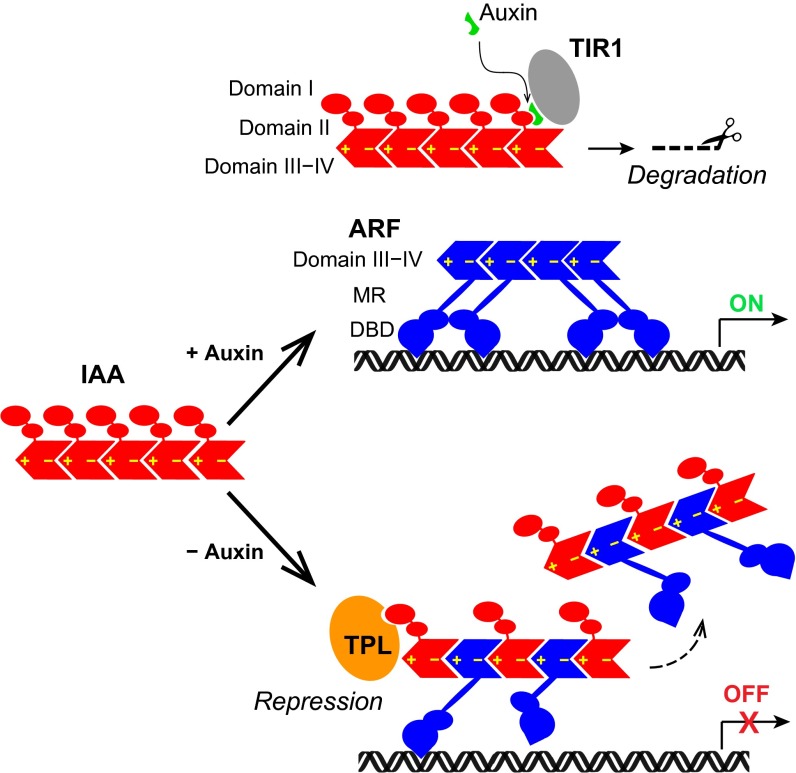

It is believed that ARF functions as a dimer or a higher-order oligomer, and Aux/IAA disrupts the ARF oligomer to repress its transcriptional activity. In addition to domain III−IV, the DNA binding domain of ARF is also known to form a functional homodimer (24). The equilibrium binding constant is not available, but small-angle X-ray scattering data suggests an estimated KD of ∼20 μM, which is much weaker than that between domain III−IV. We postulate that ARF monomers first oligomerize through domain III−IV, and the DNA binding domain further stabilizes the association. Given that IAA17 can form a tight heterodimer using both positive and negative interfaces, it may insert itself into the ARF5 oligomer to form a hetero-oligomer of alternating subunits (Fig. 5). In this model, the transcriptional repression can be achieved by (i) compromised DNA binding of ARF5 due to an improper positioning between ARF subunits within the hetero-oligomer, and (ii) participation of the corepressors such as TPL recruited by IAA17. By forming hetero-oligomers, ARF monomers keep high local concentrations even during the transcriptional repression state, so that functional ARF oligomers can rapidly reestablish upon Aux/IAA degradation and promptly express auxin-response genes. Switching between homo- and hetero-oligomers via subunit exchange driven by thermodynamic equilibrium may thus account for the mechanism that modulates auxin-response gene expression.

Fig. 5.

A model of transcriptional control from the interaction between Aux/IAA and ARF. In the presence of auxin, Aux/IAA is subject to proteosomal degradation and ARF forms an active oligomer to turn on the gene expression. In the absence of auxin, Aux/IAA and ARF form hetero-oligomers for transcriptional repression. Insertion of Aux/IAA into the ARF homo-oligomer impairs the interaction between the N-terminal DNA binding domain (DBD) and the auxin response element, leading to transcriptional repression. In addition, association of the corepressor TPL with Aux/IAA represses the gene expression. MR, middle region.

Materials and Methods

Sample Preparation and NMR Spectroscopy.

We used IAA17III−IV (G109−L217) and ARF5III−IV (T789−G885) with mutations to generate monomeric proteins as follows: K114M for IAA17M1, D183N/D187N for IAA17M2, K797M for ARF5M1, and D847N/D851N for ARF5M2. IAA17M2 was used for structure calculation and dynamics using MMR spectroscopy. Details of sample preparation and NMR spectroscopy are provided in Supporting Information.

Structure Calculation.

Interproton distance restraints were derived from the NOE spectra and classified into distance ranges according to the peak intensity. ϕ/ψ torsion angle restraints were derived from backbone chemical shifts using the program TALOS+ (25). Structures were calculated by simulated annealing in torsion angle space using the Xplor-NIH program (16). The target function for simulated annealing included a covalent geometry, a quadratic van der Waals repulsion potential (26), square-well potentials for interproton distance and torsion angle restraints (27), hydrogen bonding, RDC restraints (28), harmonic potentials for 13Cα/13Cβ chemical shift restraints (29), a multidimensional torsion angle database potential of mean force (30), and a radius of gyration term (31). The radius of gyration represented a weak overall packing potential, and structures were displayed using the VMD-X-PLOR software (32).

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry.

ITC was performed at 25 °C using an iTC200 calorimeter (GE Healthcare). 0.1 mM of IAA17M1 or ARF5M1 was placed in the cell and titrated with 1 mM IAA17M2 or ARF5M2. Twenty consecutive 2-μL aliquots of protein were titrated into the cell. The duration of each injection was 4 s, and injections were made at intervals of 150 s. The heats associated with the dilution of the substrates were subtracted from the measured heats of binding. ITC titration data were analyzed with the Origin version 7.0 program provided with the instrument.

Characterization of the Oligomerization State.

We assumed that individual monomer and oligomers were in exchange with one another in full equilibrium using a single equilibrium constant (KD = 6.6 μM). Starting with a two-state model (monomer−dimer equilibrium), we calculated the equilibrium populations of individual states and thereby obtained the average oligomer size at given concentrations. If the calculated oligomer size failed to reproduce the experimental values from SEC, higher-order oligomers (trimer, tetramer, etc.) were introduced to the model in turn until the calculated and experimental values matched. At each round, the equilibrium populations were recalculated in a recursive manner to ensure that full equilibrium conditions were met between all participants.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the high-field NMR facility at the Korea Basic Science Institute and the National Center for Inter-University Research Facilities. This work was supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (2013R1A1A2010856) and the Research Institute of Agriculture and Life Sciences.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

Data deposition: Atomic coordinates and NMR restraints of the reported solution structure have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.pdb.org (PDB ID code 2MUK), and the BioMagResBank, www.bmrb.wisc.edu (accession no. 25217).

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1419525112/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Vanneste S, Friml J. Auxin: a trigger for change in plant development. Cell. 2009;136(6):1005–1016. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berleth T, Sachs T. Plant morphogenesis: Long-distance coordination and local patterning. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2001;4(1):57–62. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5266(00)00136-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chapman EJ, Estelle M. Mechanism of auxin-regulated gene expression in plants. Annu Rev Genet. 2009;43:265–285. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-102108-134148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dharmasiri N, Dharmasiri S, Estelle M. The F-box protein TIR1 is an auxin receptor. Nature. 2005;435(7041):441–445. doi: 10.1038/nature03543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kepinski S, Leyser O. The Arabidopsis F-box protein TIR1 is an auxin receptor. Nature. 2005;435(7041):446–451. doi: 10.1038/nature03542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Szemenyei H, Hannon M, Long JA. TOPLESS mediates auxin-dependent transcriptional repression during Arabidopsis embryogenesis. Science. 2008;319(5868):1384–1386. doi: 10.1126/science.1151461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tan X, et al. Mechanism of auxin perception by the TIR1 ubiquitin ligase. Nature. 2007;446(7136):640–645. doi: 10.1038/nature05731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kim J, Harter K, Theologis A. Protein-protein interactions among the Aux/IAA proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94(22):11786–11791. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.22.11786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guilfoyle T, Hagen G, Ulmasov T, Murfett J. How does auxin turn on genes? Plant Physiol. 1998;118(2):341–347. doi: 10.1104/pp.118.2.341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ouellet F, Overvoorde PJ, Theologis A. IAA17/AXR3: Biochemical insight into an auxin mutant phenotype. Plant Cell. 2001;13(4):829–841. doi: 10.1105/tpc.13.4.829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tiwari SB, Hagen G, Guilfoyle T. The roles of auxin response factor domains in auxin-responsive transcription. Plant Cell. 2003;15(2):533–543. doi: 10.1105/tpc.008417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guilfoyle TJ, Hagen G. Getting a grasp on domain III/IV responsible for Auxin Response Factor-IAA protein interactions. Plant Sci. 2012;190:82–88. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2012.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sumimoto H, Kamakura S, Ito T. Structure and function of the PB1 domain, a protein interaction module conserved in animals, fungi, amoebas, and plants. Sci STKE. 2007;2007(401):re6. doi: 10.1126/stke.4012007re6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nanao MH, et al. Structural basis for oligomerization of auxin transcriptional regulators. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3617. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Korasick DA, et al. Molecular basis for AUXIN RESPONSE FACTOR protein interaction and the control of auxin response repression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(14):5427–5432. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1400074111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schwieters CD, Kuszewski J, Clore GM. Using Xplor–NIH for NMR molecular structure determination. Prog Nucl Magn Reson Spectrosc. 2006;48(1):47–62. doi: 10.1016/s1090-7807(02)00014-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vernoux T, et al. The auxin signalling network translates dynamic input into robust patterning at the shoot apex. Mol Syst Biol. 2011;7:508. doi: 10.1038/msb.2011.39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guilfoyle TJ, Hagen G. Auxin response factors. Curr Opin Plant Biol. 2007;10(5):453–460. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2007.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Knighton DR, et al. Crystal structure of the catalytic subunit of cyclic adenosine monophosphate-dependent protein kinase. Science. 1991;253(5018):407–414. doi: 10.1126/science.1862342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jarymowycz VA, Stone MJ. Fast time scale dynamics of protein backbones: NMR relaxation methods, applications, and functional consequences. Chem Rev. 2006;106(5):1624–1671. doi: 10.1021/cr040421p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sapienza PJ, Lee AL. Using NMR to study fast dynamics in proteins: Methods and applications. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2010;10(6):723–730. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2010.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ghaemmaghami S, et al. Global analysis of protein expression in yeast. Nature. 2003;425(6959):737–741. doi: 10.1038/nature02046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lu P, Vogel C, Wang R, Yao X, Marcotte EM. Absolute protein expression profiling estimates the relative contributions of transcriptional and translational regulation. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25(1):117–124. doi: 10.1038/nbt1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boer DR, et al. Structural basis for DNA binding specificity by the auxin-dependent ARF transcription factors. Cell. 2014;156(3):577–589. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shen Y, Delaglio F, Cornilescu G, Bax A. TALOS+: A hybrid method for predicting protein backbone torsion angles from NMR chemical shifts. J Biomol NMR. 2009;44(4):213–223. doi: 10.1007/s10858-009-9333-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nilges M, Gronenborn AM, Brünger AT, Clore GM. Determination of three-dimensional structures of proteins by simulated annealing with interproton distance restraints. Application to crambin, potato carboxypeptidase inhibitor and barley serine proteinase inhibitor 2. Protein Eng. 1988;2(1):27–38. doi: 10.1093/protein/2.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Clore GM, et al. The three-dimensional structure of α1-purothionin in solution: Combined use of nuclear magnetic resonance, distance geometry and restrained molecular dynamics. EMBO J. 1986;5(10):2729–2735. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1986.tb04557.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Clore GM, Gronenborn AM, Tjandra N. Direct structure refinement against residual dipolar couplings in the presence of rhombicity of unknown magnitude. J Magn Reson. 1998;131(1):159–162. doi: 10.1006/jmre.1997.1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kuszewski J, Qin J, Gronenborn AM, Clore GM. The impact of direct refinement against 13C α and 13C β chemical shifts on protein structure determination by NMR. J Magn Reson B. 1995;106(1):92–96. doi: 10.1006/jmrb.1995.1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Clore GM, Kuszewski J. χ1 rotamer populations and angles of mobile surface side chains are accurately predicted by a torsion angle database potential of mean force. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124(12):2866–2867. doi: 10.1021/ja017712p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kuszewski J, Gronenborn AM, Clore GM. Improving the packing and accuracy of NMR structures with a pseudopotential for the radius of gyration. J Am Chem Soc. 1999;121(10):2337–2338. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schwieters CD, Clore GM. The VMD-XPLOR visualization package for NMR structure refinement. J Magn Reson. 2001;149(2):239–244. doi: 10.1006/jmre.2001.2300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Laskowski RA, MacArthur MW, Moss DS, Thornton JM. PROCHECK: A program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structures. J Appl Cryst. 1993;26(2):283–291. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Krissinel E, Henrick K. Inference of macromolecular assemblies from crystalline state. J Mol Biol. 2007;372(3):774–797. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.