Significance

New radiocarbon (14C) dates on American mastodon (Mammut americanum) fossils in Alaska and Yukon suggest this species suffered local extirpation before terminal Pleistocene climate changes or human colonization. Mastodons occupied high latitudes during the Last Interglacial (∼125,000–75,000 y ago) when forests were established. Ecological changes during the Wisconsinan glaciation (∼75,000 y ago) led to habitat loss and population collapse. Thereafter, mastodons were limited to areas south of the continental ice sheets, where they ultimately died out ∼10,000 14C years B.P. Extirpation of mastodons and some other megafaunal species in high latitudes was thus independent of their later extinction south of the ice. Rigorous pretreatment was crucial to removing contamination from fossils that originally yielded erroneously “young” 14C dates.

Keywords: extinctions, Pleistocene, radiocarbon, megafauna, Beringia

Abstract

Existing radiocarbon (14C) dates on American mastodon (Mammut americanum) fossils from eastern Beringia (Alaska and Yukon) have been interpreted as evidence they inhabited the Arctic and Subarctic during Pleistocene full-glacial times (∼18,000 14C years B.P.). However, this chronology is inconsistent with inferred habitat preferences of mastodons and correlative paleoecological evidence. To establish a last appearance date (LAD) for M. americanum regionally, we obtained 53 new 14C dates on 36 fossils, including specimens with previously published dates. Using collagen ultrafiltration and single amino acid (hydroxyproline) methods, these specimens consistently date to beyond or near the ∼50,000 y B.P. limit of 14C dating. Some erroneously “young” 14C dates are due to contamination by exogenous carbon from natural sources and conservation treatments used in museums. We suggest mastodons inhabited the high latitudes only during warm intervals, particularly the Last Interglacial [Marine Isotope Stage (MIS) 5] when boreal forests existed regionally. Our 14C dataset suggests that mastodons were extirpated from eastern Beringia during the MIS 4 glacial interval (∼75,000 y ago), following the ecological shift from boreal forest to steppe tundra. Mastodons thereafter became restricted to areas south of the continental ice sheets, where they suffered complete extinction ∼10,000 14C years B.P. Mastodons were already absent from eastern Beringia several tens of millennia before the first humans crossed the Bering Isthmus or the onset of climate changes during the terminal Pleistocene. Local extirpations of mastodons and other megafaunal populations in eastern Beringia were asynchrononous and independent of their final extinction south of the continental ice sheets.

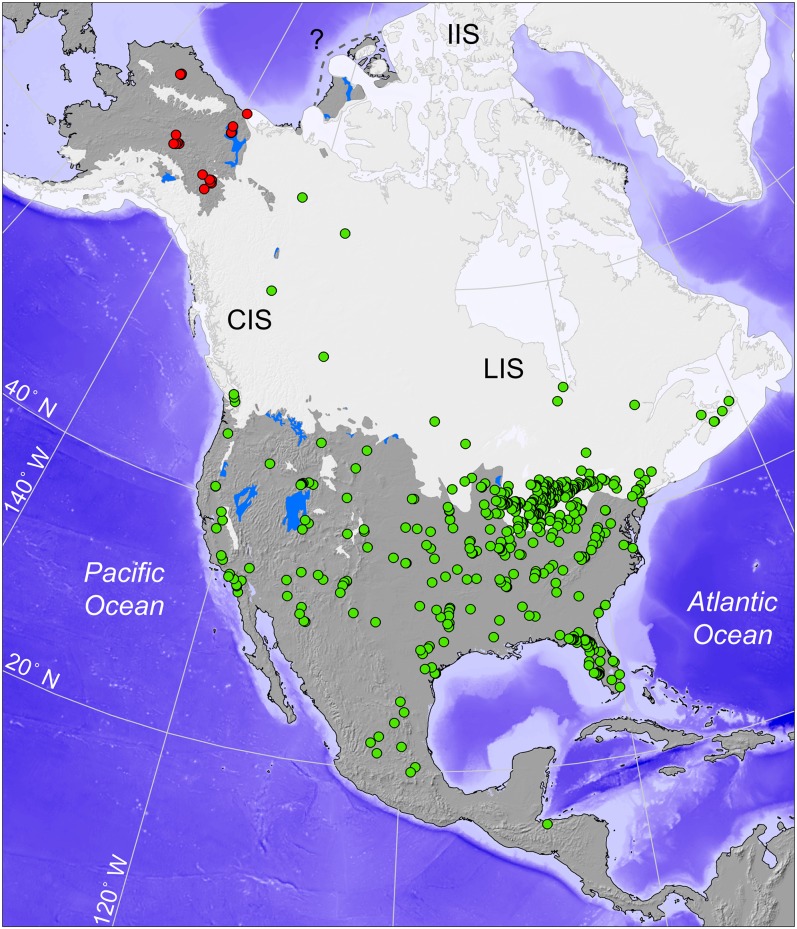

Last appearance dates (LADs) are crucial for evaluating hypotheses regarding the timing and causes of species disappearance in the fossil record (1). In principle, species extinction and local extirpation chronologies can be rigorously established by determining LADs using a variety of radiometric dating methods. In practice, however, problematic and incomplete chronological data inevitably affect the precision and accuracy of LADs. This may in turn affect how potential extinction mechanisms are evaluated. A case in point is the radiocarbon (14C) record of Pleistocene American mastodon (Mammut americanum) fossils from the unglaciated regions of Alaska and Yukon in northwest North America, collectively known as eastern Beringia (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Known fossil localities of M. americanum across North America [Table S1, with late Pleistocene glacial limits (white) and glacial/pluvial lakes (light blue) following ref. 22]. CIS, Cordilleran Ice Sheet; IIS, Innuitian Ice Sheet; LIS, Laurentide Ice Sheet. Dashed line and question mark denote uncertainty over northwest LIS limits (23). Localities with fossils analyzed in this study in Alaska and Yukon (northwest North America) are designated by red circles. Locality data for American mastodons across the continent, designated as green circles, are from refs. 5–8, 11–17, 19, 20, and 24 (see Table S1) in addition to collections data from the United States National Park Service, Royal Ontario Museum, and Royal British Columbia Museum.

The American mastodon was one of roughly 70 species of mammals in North America that died out during the late Quaternary extinctions (2, 3). American mastodon appears in the North American fossil record roughly 3.5 million years ago and was the terminal member of a lineage that arose from its presumed ancestor Miomastodon merriami, which had crossed the Bering Isthmus from Eurasia during the middle Miocene (4). Over the course of the late Pleistocene (∼125,000–10,000 y ago), M. americanum became widespread, occupying many parts of continental North America, as well as peripheral areas as mutually remote as the tropics of Honduras and the Arctic coast of Alaska (5−8) (Fig. 1). Despite their Old World roots, and unlike American populations of their distant relative the woolly mammoth (Mammuthus primigenius) (9), there is no evidence that American mastodons managed to cross the Bering Isthmus westward into Eurasia (4).

The rich and well-dated record of American mastodons living in the midlatitudes, particularly near the Great Lakes and Atlantic coast regions, demonstrates they were among the last members of the megafauna to disappear in North America near the end of the Pleistocene (4, 10–13). The current LAD for mastodons south of the former Laurentide and Cordilleran ice sheets is ∼10,000 14C years B.P. (B.P. = years before A.D. 1950), based on enamel and ultrafiltered bone collagen from the Overmyer specimen from northern Indiana (11). Paleoenvironmental data from this region are consistent with the view that American mastodons preferentially inhabited coniferous or mixed forests or lowland swampy habitats in what can plausibly be regarded as the most persistent portion of their late Pleistocene geographic range (14–16) (Fig. 1 and Table S1). Mastodon remains at archeological sites south of the former continental ice sheets underscore the prominent role this mammal species has played in ongoing discussions of the late Quaternary extinctions (17).

American mastodon and woolly mammoth differed in both habitat and dietary preference. As large grazers that relied on grasses and forbs, woolly mammoths were well adapted to semiarid, generally treeless steppe-tundra habitats that were widespread in eastern Beringia during Pleistocene glacial intervals (18). Conversely, mastodons were browsing specialists, relying on woody plants and preferentially inhabiting coniferous or mixed woodlands with lowland swamps (4). The large, bunodont teeth of mastodons were effective at stripping and crushing twigs, leaves, and stems from shrubs and trees (4). Plant remains from purported coprolites and stomach contents found in association with several mastodon skeletons found south of the former continental ice sheets include masticated or partially digested stick fragments, twigs, deciduous leaves, conifer needles, and conifer cones (4, 19). In places where American mastodons and woolly mammoths coexisted during the late Pleistocene, stable isotope and other paleoecological data establish these two proboscideans occupied and exploited distinct environmental niches and did not compete for the same resources (16, 20).

In light of their preferred diet and habitat, the Arctic and Subarctic during the late Pleistocene would seem to be unlikely places for mastodon populations to live. Indeed, their fossils are quite rare; in the course of more than a century of collecting, American mastodon accounts for <5% of all proboscidean fossils recovered in Alaska and Yukon (7). Nevertheless, American mastodons certainly lived at high latitudes, either in small numbers or, more probably, for limited intervals. The likeliest proposed scenario is that American mastodons occupied the Arctic and Subarctic region only intermittently, during warm, Pleistocene interglacial periods, when widespread boreal forests and muskeg wetlands were established (21). During the Wisconsinan glaciation, when much of high-latitude North America was ice covered (22, 23), mastodons were probably absent in the cold, dry, unglaciated refugium of eastern Beringia. Indeed, this hypothesis was put forth decades before the advent of radiocarbon dating (24).

It is thus surprising that the meager published 14C record has complicated, rather than corroborated, the long-standing hypothesis (24) that mastodons were Pleistocene interglacial residents of the Arctic and Subarctic and were absent during glacial periods (Table 1). Two previously published finite 14C dates, obtained from molars collected in the Klondike area of central Yukon, imply mastodon persistence through the late Pleistocene to ∼18,000 14C years B.P., well into the Marine Isotope Stage (MIS) 2 full-glacial period (7, 25) (Table 1 and Table S2). In contrast, published dates on fossils from the Ikpikpuk River, Alaska (26), and Herschel Island, Yukon (27), are nonfinite (i.e., greater than ∼50,000 y B.P., the effective limit of 14C dating methods) and were interpreted to mean that mastodons lived along the Arctic coast only during the Last Interglacial (MIS 5: ∼125,000–75,000 y ago). If American mastodons did survive in eastern Beringia during the MIS 2 full-glacial period, and possibly even as late as the terminal Pleistocene as suggested by the two finite ages on Yukon molars (7, 25) (Table 1), their local extirpation was presumably driven by one or more of the catastrophic factors proposed for the rest of the continental-scale extinctions ∼13,000–10,000 14C years B.P., such as the first colonization by early humans (2, 17), abrupt climate change (28, 29), or extraterrestrial impact (30, 31).

Table 1.

Radiocarbon (14C) dates on American mastodon fossils from Alaska and Yukon

| Specimen no. | 14C years B.P. | Lab no. | Details |

| Previously published radiocarbon dates | |||

| Yukon | |||

| CMN 33897 | 24,980 ± 1300 | Beta 16163 | ref. 7 |

| YG 33.2 | >45,130 | Beta 189291 | ref. 27 |

| YG 43.2 | 18,460 ± 350 | TO 7745 | ref. 25 |

| Alaska | |||

| UAMES 2414 | >50,000 | CAMS 91805 | ref. 26 |

| New radiocarbon dates on previously published Yukon specimens | |||

| CMN 33897 | >51,700 | UCIAMS 78694 | UF |

| YG 43.2 | >49,200 | UCIAMS 75320 | UF |

| New specimens with single radiocarbon dates | |||

| Yukon | |||

| CMN 8707 | >51,700 | UCIAMS 78700 | UF |

| CMN 11697 | >51,700 | UCIAMS 78698 | UF |

| CMN 15352 | 45,700 ± 2500 | UCIAMS 78695 | UF |

| CMN 31898 | 50,300 ± 3500 | UCIAMS 78696 | UF |

| CMN 33066 | >49,900 | UCIAMS 78697 | UF |

| CMN 42551 | >51,700 | UCIAMS 78699 | UF |

| CMN 42552 | >41,100 | UCIAMS 78703 | UF |

| F:AM: 104842 | 42,100 ± 1300 | UCIAMS 88773 | UF |

| YG 50.1 | >41,100 | AA 84994 | STD |

| YG 139.5 | >41,100 | AA 84985 | STD |

| YG 357.1 | >41,100 | AA 84995 | STD |

| YG 361.9 | >49,900 | UCIAMS 72419 | UF |

| Alaska | |||

| F:AM: 103281 | >50,800 | UCIAMS 88775 | UF |

| F:AM: 103292 | 46,100 ± 2100 | UCIAMS 88771 | UF |

| F:AM: 103295 | >46,900 | UCIAMS 88774 | UF |

| UAMES 7666 | >50,800 | UCIAMS 88767 | UF |

| UAMES 7667 | 51,300 ± 4000 | UCIAMS 88766 | UF |

| UAMES 30197 | >51,700 | UCIAMS 117242 | UF |

| UAMES 30198 | >51,200 | UCIAMS 117243 | UF |

| UAMES 30199 | >46,400 | UCIAMS 117235 | UF |

| UAMES 30200 | 47,000 ± 2300 | UCIAMS 117241 | UF |

| UAMES 30201 | >47,500 | UCIAMS 117232 | UF |

| UAMES 34126 | >46,100 | UCIAMS 117237 | UF |

| New specimens with multiple radiocarbon dates | |||

| Yukon | |||

| CMN 333 | 40,600 ± 1000 | UCIAMS 78701 | UF |

| >47,800 | UCIAMS 83803 | UF | |

| >49,500 | UCIAMS 83804 | UF | |

| YG 26.1 | 39,200 ± 3200 | AA 84981 | STD |

| >50,300 | UCIAMS 78705 | UF | |

| >51,700 | UCIAMS 78704 | UF | |

| Alaska | |||

| F:AM: 103277 | 29,610 ± 340 | OxA-25402 | UF |

| 33,810 ± 460 | UCIAMS 88772 | UF | |

| 47,100 ± 2500 | OxA-X-2490–48 | SAA | |

| F:AM: 103291 | 35,240 ± 610 | UCIAMS 88776 | UF |

| 42,800 ± 2400 | OxA-X-2515–35 | SAA | |

| 44,900 ± 2600 | OxA-X-2515–34 | SAA | |

| UAMES 2414 | >50,000 | CAMS 91805 | STD |

| >48,100 | UCIAMS 117234 | UF | |

| UAMES 7663 | 20,440 ± 130 | OxA-25401 | UF |

| 33,090 ± 470 | UCIAMS 88768 | UF | |

| 43,000 ± 2200 | OxA-X-2457–7 | SAA | |

| 48,200 ± 2600 | OxA-X-2492–15 | SAA | |

| UAMES 9705 | 38,800 ± 1100 | CAMS 53904 | STD |

| >51,700 | UCIAMS 117239 | UF | |

| UAMES 11095 | >51,200 | UCIAMS 117233 | UF |

| >54,000 | CAMS 91808 | STD | |

| UAMES 12047 | 51,700 ± 3200 | CAMS 92090 | STD |

| >48,800 | UCIAMS 117240 | UF | |

| UAMES 12060 | 36,370 ± 790 | AA-48275 | STD |

| 49,800 ± 3300 | UCIAMS 117236 | UF | |

| UAMES 34125 | 31,780 ± 360 | UCIAMS 117238 | UF |

| >50,100 | OxA-29838 | UF | |

All nominally finite radiocarbon dates are reported to 1σ. Specimen collection repositories: CMN, Canadian Museum of Nature; F:AM, Frick Collection of the American Museum of Natural History; UAMES, University of Alaska Museum Earth Sciences Collection; YG, Yukon Government Paleontology Program. Radiocarbon laboratories: AA, Arizona Accelerator Mass Spectrometry Laboratory; Beta, Beta Analytic Radiocarbon Laboratory; CAMS, Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory Center for Accelerator Mass Spectrometry; OxA, Oxford Radiocarbon Accelerator Unit; TO, Isotrace Laboratory the Canadian Centre for Accelerator Mass Spectrometry; UCIAMS, University of California, Irvine Keck Carbon Cycle Accelerator Mass Spectrometry Laboratory. Fraction dated: SAA, single amino acid hydroxyproline (35); STD, standard collagen gelatin pretreatment without ultrafiltration (49); UF, ultrafiltered collagen (32, 34).

Testing the Radiocarbon Record of Arctic and Subarctic Mastodons

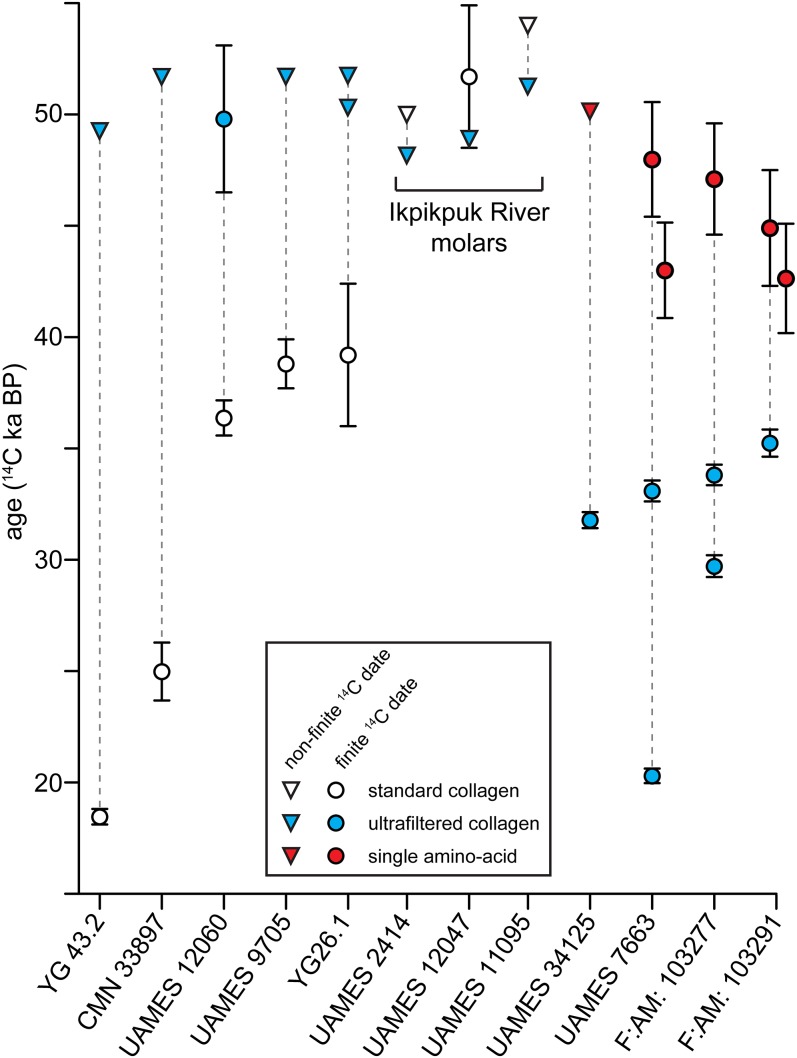

To rigorously establish a plausible LAD for American mastodons in eastern Beringia, and to shed light on extinction processes, we undertook a broad program of 14C dating on fossils recovered from this region (Fig. 2, Table 1, Materials and Methods, Table S2, SI Materials and Methods, and Figs. S1−S3). If the hypothesis that mastodons survived in eastern Beringia into the MIS 2 full glacial is correct, at least some of the dates within our new dataset should fall within the expected range (∼25,000–10,000 14C years B.P.). Conversely, if none are found, it is reasonable to suspect that the finite dates previously reported were erroneous, perhaps as a result of young carbon contamination or methodological limitations.

Fig. 2.

Summary of the effects of different mastodon bone collagen pretreatments on 14C dates. Age (ka) = 103 years B.P. White, blue, and red symbols denote, respectively, standard collagen, ultrafiltered collagen, and single amino acid hydroxyproline. Finite 14C ages (circles) have 1σ laboratory uncertainty bars. Nonfinite 14C dates (triangles) should be interpreted as “greater than” the indicated age. The three paired dates clustered at ∼50,000 14C years B.P. are from Ikpikpuk River (Alaska) molar specimens that were not treated with museum chemical consolidants.

Here we report 14C dates on fossils of American mastodons from Alaska and Yukon recently recovered from field localities as well as others found in museum collections. This dataset represents the vast majority of Alaskan and Yukon mastodon fossils available in public repositories. We also redated previously reported specimens that originally yielded finite 14C dates. Importantly, we exploit recent methodological advances in collagen pretreatment (32–34) and 14C dating of single amino acids (SAAs) (35), which have markedly improved the reliability of 14C date determinations on bone and teeth (see Materials and Methods and SI Materials and Methods). Our study represents the most exhaustive and focused dataset bearing on American mastodon LADs for Arctic and Subarctic North America (or any other region) to date.

Results

Fifty-three new 14C dates were obtained from thirty-six M. americanum fossils from Alaska and Yukon (Table 1 and Table S2). All high-latitude Pleistocene mastodon fossils that we have dated are either beyond the effective limit of 14C dating or, if results were analytically finite, they are so close to the effective limit of 14C dating that they may be reasonably interpreted as suspect or nonfinite. Here it is especially important to note that some of our newly studied specimens initially yielded anomalously young finite ages (∼40,000–20,000 14C years B.P.) that we suspected might be erroneous because they were seeming outliers within the overall dataset. Subsequent redating of those specimens, using more stringent collagen pretreatment techniques and SAAs, in turn, yielded 14C dates that were effectively nonfinite in all cases (Table 1, Fig. 2, and SI Materials and Methods). On this evidence, we are confident that all of the mastodon fossils in our dataset are indeed older than the effective limit of 14C dating (>50,000 y B.P.).

This dataset includes new nonfinite 14C dates on specimens from Yukon that were previously reported to date to the MIS 2 full-glacial period (Table 1 and Fig. 2). The fact that every new fossil dates near to or beyond the effective limit of radiocarbon dating permits the rejection of previous interpretations favoring local survival of mastodons in eastern Beringia during the MIS 2 full glacial (7, 25). Our new 14C data strongly imply that American mastodons had already disappeared from eastern Beringia tens of millennia before MIS 2, and well before the arrival of humans (28) or the onset of the dramatic climatic and environmental changes associated with the terminal Pleistocene ∼13,000–10,000 14C years B.P. (28–30). Furthermore, our data are consistent with the small number of previously published nonfinite (or effectively nonfinite) ages from northern, glaciated regions of Canada (7, 8) (Fig. 1) that demonstrates the presence of mastodons before the establishment of Wisconsinan continental ice sheets (MIS 4–2).

Discussion

Problematic Radiocarbon Dates and Contamination.

We hypothesized that some of the initial, anomalously “young” (<40,000 14C years B.P.) dates we obtained were due to contamination from natural postmortem sources or materials routinely used in museum conservation. Subsequent analysis of ultrafiltered collagen or SAAs confirmed this hypothesis. On redating, the same specimens yielded effectively nonfinite dates, demonstrating that these samples were in fact contaminated with exogenous carbon (Table 1 and Fig. 2). In the case of some particularly problematic specimens, the 14C dates obtained from SAAs were roughly 10 millenia older than age estimates based on ultrafiltered collagen alone. Our results are an apt demonstration that, where there is very little original 14C left in a sample, either due to the actual age of the specimen or the quality of its preservation, even a miniscule amount of contamination can substantially change the results of 14C age determination (33).

Mastodon Dispersal, Extirpation, Retraction, and Extinction.

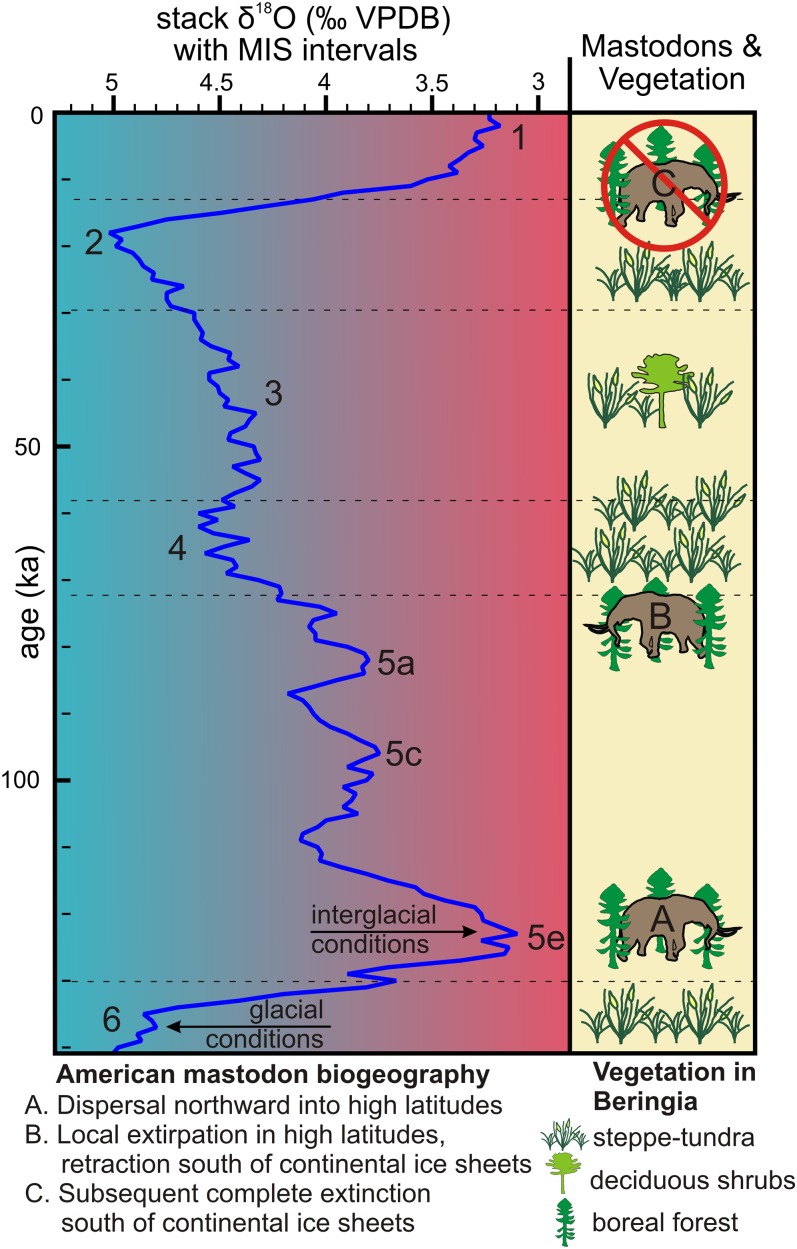

The fundamental revision of the chronology for American mastodons in the Arctic and Subarctic offered here has implications that go beyond correction and amplification of the 14C record. The new chronology prompts us to examine related lines of evidence to develop a more robust picture of mastodon population dispersal and collapse in high-latitude North America tens of thousands of years earlier than previously thought (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Summary of late Pleistocene climatic changes, Marine Isotope Stages, vegetation in eastern Beringia, and inferred biogeographic history of American mastodons. Age (ka) = 103 years ago. The marine δ18O data for foraminifera are from ref. 36, and vegetation data are from refs. 21 and 37.

Ecological and habitat constraints.

If American mastodons were shrub/tree browsing specialists, then it is reasonable to assume that they only dispersed northward to inhabit the high latitudes during relatively warm and wet periods, particularly during the Last Interglacial (MIS 5) when forests and wetlands formed across the region (Fig. 3, noting refs. 21, 36, and 37). However, their residency would have been temporary. Subsequent advance of the Laurentide and Cordilleran ice sheets during the Wisconsinan glacial interval of MIS 4 (∼75,000 y ago) would have displaced Pleistocene megafauna, including American mastodons, from much of high-latitude North America. In unglaciated eastern Beringia, woody plants, forests, and perennial wetlands were largely eliminated amid increasingly arid conditions, as revealed by regional aeolian deposits including loess and sand wedges, and associated paleoecological proxies (37). Cold, dry glacial conditions resulted in steppe-tundra vegetation dominated by herbaceous plants and graminoids on well-drained soils across Alaska and Yukon (18, 37). Thus, subsequent to MIS 5, the kinds of habitats and browse preferred by mastodons would have become largely absent in eastern Beringia, with true interglacial conditions returning only in the Holocene, <10,000 14C years B.P. (28). Together with our radiocarbon data, we infer from these considerations that M. americanum in eastern Beringia experienced major habitat loss ∼75,000 y ago during the onset of Wisconsinan glacial conditions of MIS 4. These climatically induced ecological changes were too severe for Arctic and Subarctic mastodon populations, resulting in local extirpation by “over-chill” and subsequent population retraction to areas south of the continental ice sheets.

High-latitude interglacial faunas.

Expansion of boreal forest environments during the MIS 5 interglacial into eastern Beringia probably facilitated concomitant northward range extension of several North American megafaunal species having habitat preferences similar to those of mastodons, including Jefferson’s ground sloth (Megalonyx jeffersonii) and giant beaver (Castoroides ohioensis) (38–40). Indeed, American mastodon and Jefferson’s ground sloth fossils cooccur within a pre-Wisconsinan Subarctic context near Yellowknife, NT, in an area that was later glaciated by the Laurentide ice sheet (38). As in the case of American mastodons, it is likely that Jefferson’s ground sloth and giant beaver also suffered pronounced habitat loss and local extirpation during the transition to MIS 4 glacial conditions. The inability of these taxa to survive in the Arctic and Subarctic outside of interglacial intervals is in good agreement with the general model of temperate taxa contracting to a more southerly distribution during glacial periods (41). By contrast, Holarctic woolly mammoth populations experienced a pronounced bottleneck during the MIS 5 interglacial, with retraction to small, isolated refugia at least partly because of replacement of the former steppe tundra by forests (42). Thus, the environmental conditions that facilitated dispersal of American mastodons into high latitudes during the last interglacial were at the same time detrimental to woolly mammoths.

Beringian biogeography.

Our new 14C dates, supported by the absence of American mastodon, Jefferson’s ground sloth, and giant beaver fossils in Eurasia, suggest that these species never inhabited eastern Beringia when the Bering Isthmus was exposed during the Wisconsinan glaciation (MIS 4–2). During Pleistocene interglacials including MIS 5, the Bering Isthmus would have been flooded by the Bering Sea (43) and therefore unavailable for overland dispersals. These data underscore the variable role that Beringia has played in mammalian paleobiogeography. Beringia has classically been regarded as a biological refugium, a dispersal corridor between the Palearctic and Nearctic ecozones, and a center of evolutionary origin (44). However, Beringia can also be seen as a biogeographic gate, open mostly to Holarctic fauna adapted to glacial conditions that could successfully disperse across the Bering Isthmus when it was exposed (i.e., Mammuthus), but generally closed for North American fauna that were adapted to forested habitats during interglacials when the Isthmus was flooded. For megafauna such as mastodons, eastern Beringia was the biogeographic end point for interglacial range expansions from more southerly parts of North America.

Asynchronous high-latitude extirpations.

If post-MIS 5 interglacial range contraction was something that affected Pleistocene forest-adapted taxa generally (i.e., Mammut, Castoroides, Megalonyx), then their local extirpations may well have occurred independently and asynchronously in different parts of North America, possibly over lengthy intervals. The model for independent and asynchronous local extirpations in eastern Beringia is supported by the limited radiocarbon record currently available for other rare megafauna that demonstrate their failure to survive in this region beyond the Last Glacial Maximum (∼18,000 14C years B.P.). Such species include stag-moose (Alces latifrons), western camels (Camelops hesternus), short-faced bear (Arctodus simus), and scimitar cats (Homotherium serum) (37). Population fluctuation and steady decline over several tens of millennia before their eventual extinction are also revealed by ancient DNA-based results from other late Pleistocene megafauna (45). LADs for several megafauna in eastern Beringia reveal a pattern of individualistic response to Quaternary environmental change (41, 46), involving local extirpation of high-latitude populations followed by subsequent population retraction to the south en route to their complete loss near the terminal Pleistocene.

Over-chill, not over-kill.

A further outcome of our revised chronology for American mastodon extirpation in northwest North America is that M. americanum was not among the megafaunal species encountered by early humans immigrating eastward across the Bering Isthmus into Alaska, at least not until they reached regions south of the continental ice sheets. Indeed, archaeological evidence for human colonzation in eastern Beringia indicates that this occurred during the latest Pleistocene, ∼12,500 14C years B.P. (18), long after mastodons had become locally extirpated. While the degree to which humans affected American mastodon populations south of the continental ice sheets remains controversial, we conclude that humans played no role in the disappearance of American mastodons from eastern Beringia.

We end with a mystery.

If American mastodons were able to disperse through the boreal forest to eastern Beringia during the Last Interglacial, what factor(s) prevented their return northward during the Pleistocene−Holocene warming transition? Mastodon records from deglaciated regions on the southern fringes of the Laurentide ice sheet (i.e., New York and southern Ontario) suggest that their return northward was well underway as climates warmed at the end of the Pleistocene. Given the known habitat preferences of American mastodons, the postglacial boreal forests that were rapidly becoming established across Canada should have been sufficient ecologically to enable reoccupation of favorable parts of high-latitude North America. Why, then, were mastodons stopped in their tracks, failing to go all of the way to the Arctic and Subarctic?

Conclusions

The final coup de grâce for American mastodons may have been dealt by one or more of the factors usually invoked in Pleistocene megafaunal extinction, such as paleoindian hunters and rapid environmental changes. Whatever the case, it is clear that the factors that directly led to extirpation of Arctic and Subarctic mastodon populations were not the same as those that caused their final extinction south of the continental ice sheets. On a continental scale, American mastodon populations were shaped by geographically complex, lengthy, and punctuated processes that involved northward dispersal during the Last Interglacial, followed by local extirpation and retraction to the south during the following Wisconsinan glacial. This kind of patterning has not been contemplated by most models of North American megafaunal extinction, which tend to concentrate on factors that are immediately correlative with conditions experienced during the terminal Pleistocene. Future modeling efforts would be well advised to treat LADs based on previously published 14C dates on fossils with caution, and, where necessary, submit doubtful cases to advanced preparation and analytical treatments such as the ones used here.

Materials and Methods

This study is based on positively identified fossil M. americanum bones and teeth from well-established Pleistocene vertebrate fossil localities of Alaska and Yukon (7, 18, 47, 48) (see Table 1, Tables S1 and S2, and Fig. 1). We rejected tusks and isolated postcranial bones because they may be confused with those of woolly mammoths (Figs. S1−S3).

Specimens from the Fairbanks (Alaska) and Klondike (Yukon) regions were recovered from active placer gold-mining operations, which release large numbers of well-preserved Pleistocene vertebrate fossils from permafrost (7, 18, 48). Specimens from the North Slope (Alaska) (47) and Old Crow (Yukon) (7) regions north of the Arctic Circle were collected from point bars and riverbanks, which are lined by highly fossiliferous, unconsolidated, permafrost sediments.

Fossils selected for 14C dating were sampled using handheld, rotating/cutting tools in the laboratories of the Yukon Paleontology Program, the University of Alaska Museum, Canadian Museum of Nature, and the American Museum of Natural History. Samples were then shipped to appropriate facilities for collagen preparation and radiocarbon analysis (Table 1 and Table S2). Details on sample collagen pretreatment and radiocarbon analysis are described in SI Materials and Methods. At the Arizona Accelerator Mass Spectrometry Laboratory and Center for Accelerator Mass Spectrometry at the Lawrence Livermore Laboratory, collagen from fossil samples was prepared using standard Longin (49) methods. At the Keck Carbon Cycle AMS facility at the University of California, Irvine, collagen from fossil samples was prepared using ultrafiltration methods (32). At the Oxford Radiocarbon Accelerator Unit, collagen from fossil samples was prepared using ultrafiltration methods (34), and SAAs from the collagen were extracted from samples suspected to be contaminated with exogenous carbon (35).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The Yukon Palaeontology Program thanks the many Yukon placer gold miners and the Vuntut Gwitchin who have provided generous support for our research on Yukon mastodons and other Pleistocene mammals. Earl Bennett of Whitehorse graciously donated a partial mastodon skeleton from his private fossil collection, inspiring G.D.Z. to learn more about when mastodons roamed the Yukon. We thank Paul Matheus and Molly Yazwinski for help with field collection on the North Slope of Alaska; Alice Telka (Paleotec Services, Ltd.) for her careful sampling of molar specimen Canadian Museum of Nature (CMN) 333; and Kieran Shepherd, Margaret Currie, and Clayton Kennedy for samples of specimens from the CMN collections. Kevin Seymour (Royal Ontario Museum) and Grant Keddie (Royal British Columbia Museum) provided mastodon location data from their provincial collections. We also thank Elizabeth Hall and Susan Hewitson for their continued field and collections work on Yukon fossils. The Bureau of Land Management Arctic Field Office sponsored the collection of the Alaska North Slope specimens.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission. J.W.W. is a guest editor invited by the Editorial Board.

See Commentary on page 18405.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1416072111/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.MacPhee RDE, et al. Radiocarbon chronologies and extinction dynamics of the Late Quaternary mammalian megafauna of the Taimyr Peninsula, Russian Federation. J Archaeol Sci. 2002;29(9):1017–1042. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Martin PS. Twilight of the Mammoths: Ice Age Extinctions and the Re-wilding of North America. Univ California Press; Berkeley, CA: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barnosky AD, Koch PL, Feranec RS, Wing SL, Shabel AB. Assessing the causes of late Pleistocene extinctions on the continents. Science. 2004;306(5693):70–75. doi: 10.1126/science.1101476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Saunders J. North America Mammutidae. In: Shoshani J, Tassy P, editors. The Proboscidea: Evolution and Palaeoecology of Elephants and Their Relatives. Oxford Univ Press; London: 1996. pp. 271–279. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Graham RW, et al. Faunmap Working Group Spatial response of mammals to Late Quaternary environmental fluctuations. Science. 1996;272(5268):1601–1606. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5268.1601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lucas SG, Alvarado GE. Fossil Proboscidea from the upper Cenozoic of Central America: Taxonomy, evolutionary and paleobiogeographic significance. Rev Geol Am Central. 2010;42:9–42. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Harington CR. Annotated Bibliography of Quaternary Vertebrates of Northern North America, With Radiocarbon Dates. Univ Toronto Press; Toronto: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harington CR. Vertebrates of the last interglaciation in Canada: A review, with new data. Geogr Phys Quat. 1990;44:375–387. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Debruyne R, et al. Out of America: Ancient DNA evidence for a new world origin of late quaternary woolly mammoths. Curr Biol. 2008;18(17):1320–1326. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.07.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Meltzer DJ, Mead JI. The timing of late Pleistocene mammalian extinctions in North America. Quat Res. 1983;19:130–135. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Woodman N, Athfield NB. Post-Clovis survival of American mastodon in the southern Great Lakes Region of North America. Quat Res. 2009;72:359–363. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feranec RS, Kozwolski AL. New AMS radiocarbon dates from Late Pleistocene mastodons and mammoths in New York State, USA. Radiocarbon. 2012;54:275–279. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dreimanis A. Extinction of mastodons in eastern North America: Testing a new climatic-environmental hypothesis. Ohio J Sci. 1968;68(6):257–272. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shoshani J. Distribution of Mammut americanum in the New World. Curr Res Pleistocene. 1990;7:125–127. [Google Scholar]

- 15.McAndrews JH, Jackson LJ. 1988. Age and environment of late Pleistocene mastodont and mammoth in southern Ontario. Late Pleistocene and Early Holocene Paleoecology and Archaeology of the Eastern Great Lakes Region, Bulletin of the Buffalo Society of Natural Sciences, eds Laub RS, Miller NG, Steadman DW (Buffalo Soc Nat Sci, Buffalo, NY), Vol 33, pp 161−172.

- 16.Yansa CH, Adams KM. Mastodons and mammoths in the Great Lakes region, USA and Canada: New insights into their diets as they neared extinction. Geogr Compass. 2012;6(4):175–188. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Haynes G. The catastrophic extinction of North American mammoths and mastodons. World Archaeol. 2002;33(3):391–416. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guthrie RD. Frozen Fauna of the Mammoth Steppe. Univ Chicago Press; Chicago: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Laub RS. 2003. The Hiscock Site: Late Pleistocene and Holocene Paleoecology and Archaeology of Western New York State, Bulletin of the Buffalo Society of Natural Sciences (Buffalo Soc Nat Sci, Buffalo, NY), Vol 37.

- 20.Metcalfe JZ, Longstaffe FJ, Hodgins G. Proboscideans and paleoenvironments of the Pleistocene Great Lakes: Landscape, vegetation, and stable isotopes. Quat Sci Rev. 2013;76:102–113. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Muhs DR, Ager TA, Begét JE. Vegetation and paleoclimate of the last interglacial period, central Alaska. Quat Sci Rev. 2001;20:41–61. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ehlers J, Gibbard PL, Hughes PD, editors. 2011. Quaternary Glaciations—Extent and Chronology: A Closer Look, Developments in Quaternary Science, ed van der Meer JJM (Springer, Heidelberg), Vol 15.

- 23.Lakeman TR, England JH. Late Wisconsinan glaciation and postglacial relative sea-level change on western Banks Island, Canadian Arctic Archipelago. Quat Res. 2013;80:99–112. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sternberg CM. New records of mastodons and mammoths in Canada. Can Field Nat. 1930;44:59–65. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Storer JE. 2002. Vertebrate paleontology of the Dawson City area. Field Guide to Quaternary Research in Central and Western Yukon Territory, Occasional Papers in Earth Sciences 2, eds Froese DG, Duk-Rodkin A, Bond JD (Heritage Branch, Gov Yukon, Whitehorse, YT, Canada), pp 24−25.

- 26.Rohland N, et al. Proboscidean mitogenomics: Chronology and mode of elephant evolution using mastodon as outgroup. PLoS Biol. 2007;5(8):e207. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zazula GD, Hare PG, Storer JE. New radiocarbon-dated fossils from Herschel Island: Implications for the palaeoenvironments and glacial chronology of the Beaufort Sea Coastlands. Arctic. 2009;62(3):273–280. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guthrie RD. New carbon dates link climatic change with human colonization and Pleistocene extinctions. Nature. 2006;441(7090):207–209. doi: 10.1038/nature04604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Graham RW, Lundelius EL., Jr . Coevolutionary disequilibrium and Pleistocene extinctions. In: Martin P, Wright HEJ, editors. Quaternary Extinctions: A Prehistoric Revolution. Univ Arizona Press; Tucson, AZ: 1984. pp. 223–249. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Firestone RB, et al. Evidence for an extraterrestrial impact 12,900 years ago that contributed to the megafaunal extinctions and the Younger Dryas cooling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(41):16016–16021. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706977104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meltzer DJ, Holliday VT, Cannon MD, Miller DS. Chronological evidence fails to support claim of an isochronous widespread layer of cosmic impact indicators dated to 12,800 years ago. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(21):E2162–E2171. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1401150111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Beaumont W, Beverly R, Southon J, Taylor RE. Bone preparation at the KCCAMS laboratory. Nucl Instrum Meth B. 2010;268:906–909. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wood RE, Bronk Ramsey C, Higham TFG. Refining background corrections for radiocarbon dating of bone collagen at ORAU. Radiocarbon. 2010;52(2-3):600–611. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brock F, Higham T, Ditchfield P, Bronk Ramsey C. Current pre-treatment methods for AMS radiocarbon dating at the Oxford Radiocarbon Accelerator Unit (ORAU) Radiocarbon. 2010;52(1):103–112. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nalawade-Chavan S, et al. New single amino acid hydroxyproline radiocarbon dates for two problematic American Mastodon fossils from Alaska. Quat Geochronol. 2014;20:23–28. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lisiecki LE, Raymo ME. A Pliocene-Pleistocene stack of 57 globally distributed benthic δ18O records. Paleoceanography. 2005;20:PA1003. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zazula GD, Froese DG, Elias SA, Kuzmina S, Mathewes RW. Early Wisconsinan (MIS 4) arctic ground squirrel middens and a squirrel-eye-view of the mammoth-steppe. Quat Sci Rev. 2011;30:2220–2237. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stock C, Richards HG. A megalonyx tooth from the Northwest Territories, Canada. Science. 1949;110(2870):709–710. doi: 10.1126/science.110.2870.709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McDonald HG, Harington CR, De Iuliis G. The ground sloth Megalonyx from Pleistocene deposits from Old Crow Basin, Yukon, Canada. Arctic. 2000;53(3):213–220. [Google Scholar]

- 40.McDonald HG, Glotzhober RC. New radiocarbon dates for the giant beaver, Castoroides ohioensis (Rodentia, Castoridae), from Ohio and its extinction. In: Farley GH, Choate JR, editors. Unlocking the Unknown; Papers Honoring Dr. Richard Zakrzewski, Fort Hays Studies, Special Issue 2. Fort Hays State Univ; Hays, KS: 2008. pp. 51–59. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stewart JR, Dalén L. Is the glacial refugium concept relevant for northern species? Clim Change. 2008;86:19–22. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Palkopoulou E, et al. Holarctic genetic structure and range dynamics in the woolly mammoth. Proc Biol Sci. 2013;280(1770):20131910. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2013.1910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hu A, et al. Influence of Bering Strait flow and North Atlantic circulation on glacial sea-level changes. Nat Geosci. 2010;3:118–121. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sher A. Traffic lights at the Beringian crossroads. Nature. 1999;397:103–104. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lorenzen ED, et al. Species-specific responses of Late Quaternary megafauna to climate and humans. Nature. 2011;479(7373):359–364. doi: 10.1038/nature10574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Grayson DK. Deciphering North American Pleistocene extinctions. J Anthropol Res. 2007;63:185–213. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mann DH, Groves P, Kunz ML, Reanier RE, Gaglioti BV. Ice-age megafauna in Arctic Alaska: Extinction, invasion and survival. Quat Sci Rev. 2013;70:91–108. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Froese DG, et al. The Klondike goldfields and Pleistocene environments of Beringia. GSA Today. 2009;19:4–10. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Longin R. New method of collagen extraction for radiocarbon dating. Nature. 1971;230(5291):241–242. doi: 10.1038/230241a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.