Abstract

Glutamyl-tRNA (Glu-tRNAGlu) is the common substrate for both protein translation and heme biosynthesis via the C5 pathway. Under normal conditions, an adequate supply of this aminoacyl-tRNA is available to both pathways. However, under certain circumstances, Glu-tRNAGlu can become scarce, resulting in competition between the two pathways for this aminoacyl-tRNA. In Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans, glutamyl-tRNA synthetase 1 (GluRS1) is the main enzyme that synthesizes Glu-tRNAGlu. Previous studies have shown that GluRS1 is inactivated in vitro by hydrogen peroxide (H2O2). This raises the question as to whether H2O2 negatively affects in vivo GluRS1 activity in A. ferrooxidans and whether Glu-tRNAGlu distribution between the heme and protein biosynthesis processes may be affected by these conditions. To address this issue, we measured GluRS1 activity. We determined that GluRS1 is inactivated when cells are exposed to H2O2, with a concomitant reduction in intracellular heme level. The effects of H2O2 on the activity of purified glutamyl-tRNA reductase (GluTR), the key enzyme for heme biosynthesis, and on the elongation factor Tu (EF-Tu) were also measured. While exposing purified GluTR, the first enzyme of heme biosynthesis, to H2O2 resulted in its inactivation, the binding of glutamyl-tRNA to EF-Tu was not affected. Taken together, these data suggest that in A. ferrooxidans, the flow of glutamyl-tRNA is diverted from heme biosynthesis towards protein synthesis under oxidative stress conditions.

Keywords: heme, oxidative stress, acidophilic, aminoacyl-tRNA

1. Introduction

Heme is a fundamental molecule for living organisms, as the cofactor for several proteins and enzymes involved in cellular processes, such as transport of gases, redox reactions and electron transport [1,2]. Despite its significant roles, heme synthesis must be carefully balanced due to the potentially toxic effects of both heme itself and its intermediates [3,4,5,6]. Heme synthesis occurs by a universally conserved metabolic pathway for synthesizing tetrapyrroles, which starts with δ-aminolevulinic acid (ALA) [1,2]. There are two ways to synthesize ALA. While animals, fungi and α-proteobacteria use the Shemin pathway, plants, archaea and most bacteria use the C5 pathway [2]. In the Shemin pathway, ALA is formed from the condensation of glycine and succinyl-CoA, a reaction that is catalyzed by ALA synthase (ALAS). In the C5 pathway, ALA is synthesized from Glu-tRNAGlu in two steps. First, the glutamate moiety of Glu-tRNAGlu is reduced to glutamate semialdehyde (GSA) by glutamyl-tRNA reductase (GluTR), and then GSA is converted to ALA by the glutamate semialdehyde 1-2 aminomutase (GSAM) [1,2]. In organisms that use the C5 pathway, Glu-tRNAGlu is a common substrate for heme and protein synthesis and must be partitioned between these two processes [7,8]. This distribution is likely determined at least partially by the demand for Glu-tRNAGlu from each pathway, which in turn depends on the physiology of each particular organism. In chemolithoautotrophic bacteria like Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans that use the C5 pathway to synthesize tetrapyrroles, high demand for Glu-tRNAGlu for heme biosynthesis is expected, due to the high cytochrome content required for respiration using poor electron donors, such as ferrous ions [9,10]. This bacterium has a complex system of glutamyl-tRNA formation composed of two non-discriminating glutamyl-tRNA synthetases (GluRS1 and GluRS2) and up to four tRNAGlu isoacceptors, with GluRS1 serving as the main enzyme for Glu-tRNAGlu formation [9,11,12]. Three out of four glutamyl-tRNAs can act as donors for both heme and protein synthesis, while the fourth is not a substrate of GluTR and likely acts exclusively in protein synthesis [12]. The above underscores the importance of maintaining a balanced Glu-tRNAGlu supply to each of these metabolic pathways in this organism. Under conditions that reduce the supply of Glu-tRNAGlu, both heme and protein synthesis could be compromised. Thus, increased competition between heme and protein biosynthesis pathways for this substrate might change the distribution of Glu-tRNAGlu toward one process or the other. Since it is known that A. ferrooxidans GluRS1 is inactivated in vitro by H2O2 [13], we wondered whether inactivating this enzyme might also occur in vivo, potentially lowering the pool of Glu-tRNAGlu in the cell and affecting the partitioning of Glu-tRNAGlu towards heme vs. protein synthesis. To investigate this question, we determined the effect of H2O2 on GluRS1 activity and heme content in A. ferrooxidans. We found that treating A. ferrooxidans with H2O2 effectively decreased the intracellular activity of GluRS1 and correlated with reduced intracellular heme levels. To provide insight into the fate of Glu-tRNAGlu under this condition, we determined the in vitro effect of H2O2 on the deacylation of Glu-tRNAGlu by GluTR and the binding of Glu-tRNAGlu to elongation factor Tu (EF-Tu). We observed that upon treatment with H2O2, the activity of purified GluTR, as well as its activation by GSAM, was reduced, while the binding of Glu-tRNAGlu to EF-Tu was not affected. Whether these effects of H2O2 on GluTR and EF-Tu occur in vivo is yet to be determined. We speculate that oxidative stress may reduce intracellular Glu-tRNAGlu concentration, potentially further reducing the partition of this aminoacyl-tRNA towards heme synthesis. Conversely, distribution of the substrate towards protein synthesis might be less affected.

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Hydrogen Peroxide Inactivates Glutamyl-tRNA Synthetase 1 (GluRS1) and Reduces Heme Levels in A. ferrooxidans

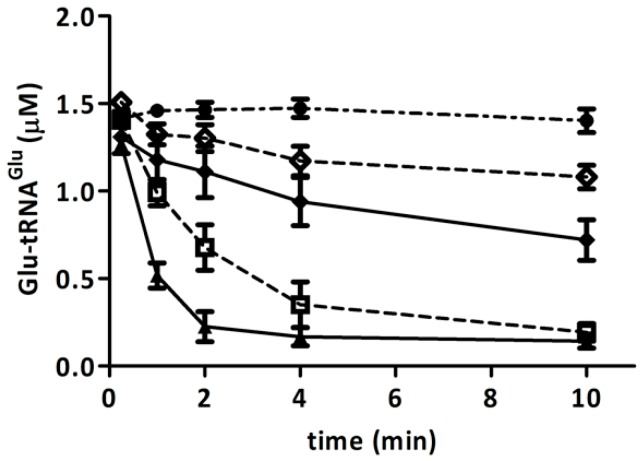

Given that GluRS1 is inactivated by H2O2 in vitro [13], we sought to determine whether GluRS1 activity is decreased in vivo in A. ferrooxidans exposed to H2O2. Cellular extracts from A. ferrooxidans treated with 1 mM H2O2 were obtained, and the specific activity of GluRS1 was evaluated in these extracts by the aminoacylation of tRNA2Glu, a specific substrate of GluRS1 [9,11]. Glu-tRNA2Glu formation was decreased by around 80% in this extract relative to the control (Figure 1). Thus, we can conclude that H2O2 also inactivates GluRS1 in vivo. Along with inactivating GluRS1, treating A. ferrooxidans with H2O2 also affected heme levels. After treating the cells with H2O2 for 2.5 h, intracellular heme concentration fell from 17.2 ± 0.75 pmol/µg of protein in control cells to 12.9 ± 0.23 pmol/µg. Inactivating GluRS1 by H2O2 exposure, then may reduce intracellular availability of Glu-tRNAGlu. Under such conditions, competition between the heme and protein biosynthesis pathways for Glu-tRNAGlu may increase. As a first step to test this hypothesis, we evaluated the effect of H2O2 on the deacylation of Glu-tRNAGlu by GluTR and its binding to EF-Tu (see below).

Figure 1.

Glutamyl-tRNA synthetase 1 (GluRS1) activity in A. ferrooxidans extracts. Specific activity of GluRS1 in extracts from A. ferrooxidans treated with 1 mM H2O2 for 30 min was measured. Control extract was prepared from cells not treated with H2O2. The mean ± SD values for pmol of Glu-tRNA2Glu/µg protein formed after 15 min in three different extracts for each condition are shown.

2.2. Glutamyl-tRNA Reductase (GluTR) from A. ferrooxidans Is Inactivated by Hydrogen Peroxide

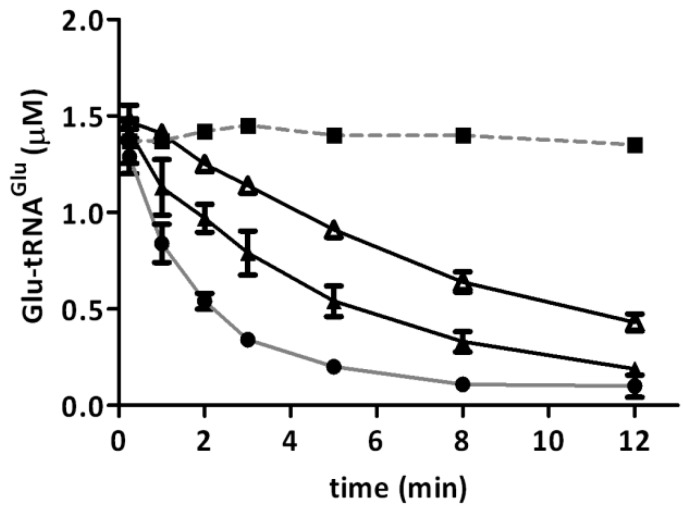

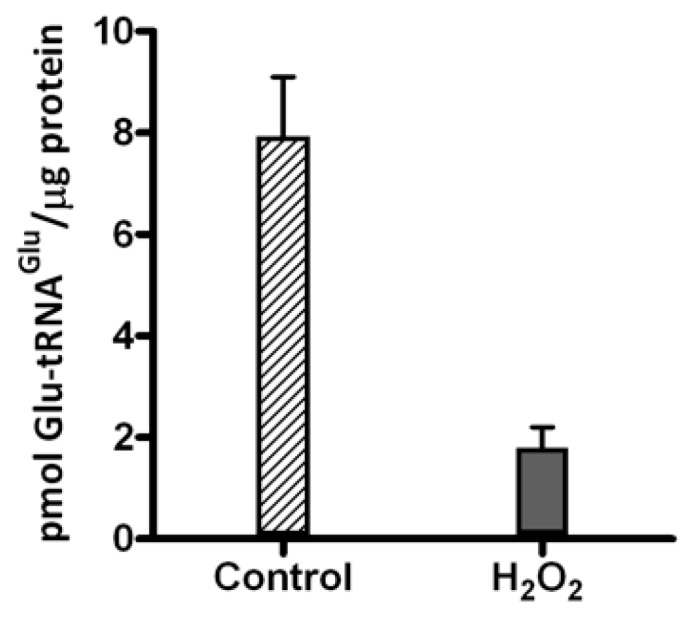

GluTR is the first enzyme committed to the biosynthesis of heme and is a key regulatory enzyme of the C5 pathway [14,15,16]. Therefore, in order to determine whether Glu-tRNAGlu is diverted from heme biosynthesis under experimental conditions, we determined the effect of H2O2 on the activity of the recombinant purified enzyme. The deacylation of Glu-tRNA2Glu catalyzed by GluTR was used to measure the enzymatic activity. We found that the presence of H2O2 decreased GluTR activity (Figure 2). Additionally, we observed that higher levels of heme bound to A. ferrooxidans GluTR [17] enhanced inactivation by H2O2. Enzyme preparations with one molecule of heme bound per four GluTR subunits (heme/protein ratio of 1/4) had an increased inactivation rate compared to enzymes with one heme per twelve GluTR subunits (heme/protein ratio of 1/12) (Table 1).

Figure 2.

Inactivation of glutamyl-tRNA reductase (GluTR) by H2O2. Recombinant purified GluTR from A. ferrooxidans was incubated with H2O2 for 20 min at 37 °C. After treatment, activity was measured as the depletion of Glu-tRNA2Glu by GluTR (1 µM) that was untreated (●) or treated with 250 μM (▲) or 500 μM H2O2 (Δ). Black squares (■) represent the control without enzyme. Each curve represents the mean of three independent determinations. For each point, standard deviation was no higher than 13%.

Table 1.

Inactivation rates (kobs) of GluTR by H2O2. Numbers in parentheses represent the relative standard deviation of three experimental replications. kobs is the first-order inactivation rate obtained from the slope of ln N/N0 against time. For detailed procedures, see Materials and Methods (GluTR Activity).

| Type of GluTR (H2O2) | GluTR (1/4) 250 µM H2O2 | GluTR (1/4) 500 µM H2O2 | GluTR (1/12) 500 µM H2O2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| kobs (s−1) | 3.18 × 10−4 ± (4.43 × 10−5) | 6.96 × 10−4 ± (4.49 × 10−5) | 4.82 × 10−4 ± (2.29 × 10−5) |

2.3. Hydrogen Peroxide Decreases the Stimulation of GluTR by Glutamate Semialdehyde 1-2 Aminomutase (GSAM)

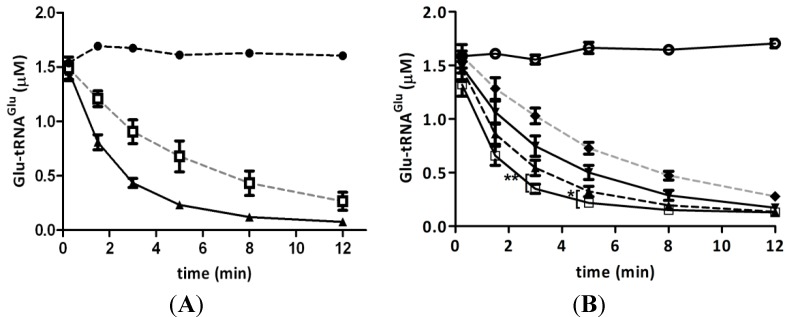

In E. coli and Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, GluTR activity is stimulated upon formation of a complex with GSAM [18,19]. As the amount of Glu-tRNAGlu devoted to heme biosynthesis depends on GluTR activity, we evaluated whether recombinant GluTR activity is stimulated by recombinant A. ferrooxidans GSAM. We found that GSAM effectively stimulated GluTR activity (Figure 3A). This effect was observed only when GluTR contained a heme/protein ratio of 1/12. To further investigate whether H2O2 affected the stimulation of GluTR by GSAM, the deacylation of Glu-tRNA2Glu was assayed after treating these enzymes with H2O2. As shown in Figure 3B, the stimulation of GluTR by GSAM was reduced when GSAM was treated with H2O2. These data, in turn, indicated that both GluTR activity and the stimulation of this enzyme by GSAM were reduced by treatment with H2O2. If these effects take place in vivo, a reduced partitioning of Glu-tRNAGlu to heme biosynthesis might occur after treating A. ferrooxidans with H2O2. These results are consistent with the reduced heme levels observed in cells treated with H2O2 (see above).

Figure 3.

Stimulation of GluTR by glutamate semialdehyde 1-2 aminomutase (GSAM). (A) The effect of GSAM on GluTR activity was analyzed by determining the deacylation of Glu-tRNA2Glu catalyzed by GluTR (1 µM heme/protein ratio of 1/12) alone (□) or in the presence of GSAM (▲). Black circles (●) correspond to deacylation of Glu-tRNA2Glu without enzyme; (B) The effect of H2O2 on GSAM stimulation of GluTR activity was evaluated by the deacylation of Glu-tRNA2Glu catalyzed by GluTR (1 µM, heme/protein ratio of 1/12) in the presence of GSAM when GluTR (▼), GSAM (▲) or both enzymes (♦) were treated with 300 μM H2O2. Control (□) represents enzyme not treated with H2O2. Open circles (○) correspond to deacylation of Glu-tRNA2Glu without enzymes. Asterisks represent statistically significant differences (** p = 0.008; * p = 0.035).

2.4. Elongation Factor Tu (EF-Tu) Is not Affected by Treatment with H2O2

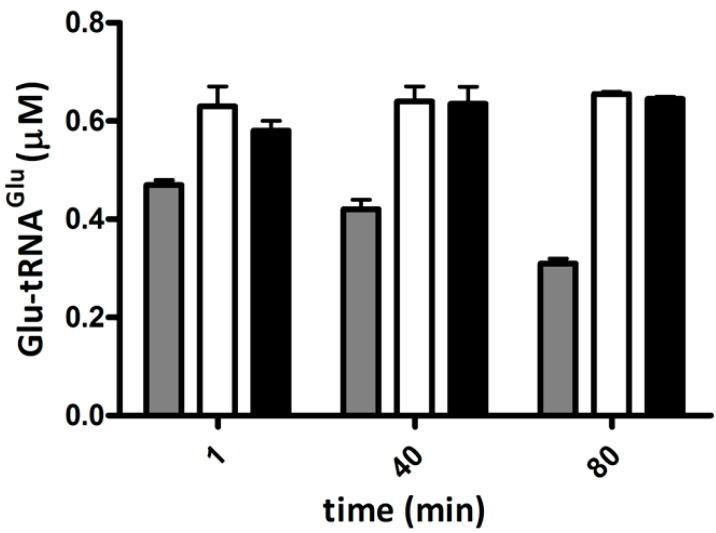

The amount of Glu-tRNAGlu dedicated to protein synthesis depends in part on its binding to EF-Tu. As a measure of Glu-tRNAGlu binding to EF-Tu, we assessed the protection of Glu-tRNAGlu by EF-Tu against spontaneous deacylation. Purified recombinant EF-Tu from A. ferrooxidans was incubated with H2O2, and then the ability of this protein to protect Glu-tRNAGlu from spontaneous deacylation was tested. EF-Tu treated with H2O2 was still able to protect Glu-tRNAGlu from deacylation (Figure 4), implying that the ability of EF-Tu to bind Glu-tRNAGlu was not altered by H2O2.

Figure 4.

Protection of Glu-tRNA2Glu by elongation factor Tu (EF-Tu) against deacylation. Remaining Glu-tRNA2Glu over time was determined in the presence of EF-Tu, treated with 500 μM H2O2 (black bars) or untreated (open bars) at 37 °C. The spontaneous deacylation of Glu-tRNA2Glu without EF-Tu was use as a control (gray bars).

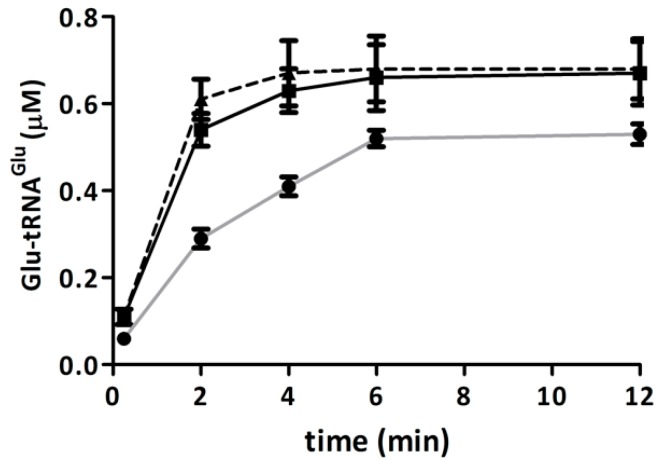

Since class I aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases are stimulated by EF-Tu [20], and this stimulation depends on the binding of the aminoacyl-tRNA to EF-Tu, we measured the effect of H2O2 on the activation of purified recombinant GluRS1 by purified recombinant EF-Tu. We observed that EF-Tu exposed to H2O2 retained its ability to stimulate GluRS1 activity (Figure 5). Taken together, the data suggest that treating recombinant purified EF-Tu with H2O2 does not affect the binding of Glu-tRNAGlu.

Figure 5.

Activity of GluRS1 in presence of EF-Tu. The aminoacylation of tRNA2Glu catalyzed by GluRS1 was determined in the absence (●) or presence of EF-Tu, treated with 500 μM H2O2 (▲) or untreated (■).

2.5. Competition of GluTR and EF-Tu for Glu-tRNAGlu Is Affected by H2O2

The observation that, after treatment with H2O2, recombinant GluTR was inactivated while recombinant EF-Tu maintained its ability to bind Glu-tRNAGlu, led us to test to whether EF-Tu would compete with GluTR for Glu-tRNAGlu. We evaluated the protection of Glu-tRNAGlu by EF-Tu against the deacylation catalyzed by GluTR. We found that EF-Tu effectively protected Glu-tRNAGlu from deacylation by GluTR, indicating that GluTR and EF-Tu compete for Glu-tRNAGlu (Figure 6). Furthermore, when GluTR and EF-Tu were both treated with H2O2, there was increased protection against the deacylation of Glu-tRNAGlu (Figure 6). In the event that this competition takes place in vivo, it is possible that under oxidative stress, Glu-tRNAGlu would be diverted from the heme biosynthesis pathway.

Figure 6.

Competition between GluTR and EF-Tu for Glu-tRNAGlu. The deacylation of Glu-tRNA2Glu catalyzed by GluTR (0.5 µM) in presence of EF-Tu is shown. Deacylation was monitored when GluTR was untreated (▲,♦) or previously treated (□,◊) with 300 μM H2O2 and in the presence of EF-Tu, treated (◊) or untreated (♦) with 300 μM H2O2. The deacylation of Glu-tRNA2Glu in the absence of GluTR or EF-Tu was used as a control (●). Each curve is the mean of three experimental replications. For each point, the standard deviation was no higher than 15%.

2.6. Discussion

Glu-tRNAGlu is a shared substrate for the biosynthetic pathways of proteins and porphyrins. Therefore, these pathways likely compete for Glu-tRNAGlu. Indeed, it has been described that partial inhibition of protein synthesis increases heme production [7]. This competition might be more pronounced under conditions that affect the availability of Glu-tRNAGlu. A. ferrooxidans is a chemolithotrophic bacterium with an elevated requirement for Glu-tRNAGlu for the synthesis of heme used in respiration processes. We previously demonstrated that GluRS1, the main enzyme that generates Glu-tRNAGlu for heme and protein synthesis in A. ferrooxidans, is inactivated by H2O2. Here we have shown that endogenous GluRS1 is also inactivated upon treatment of the cells with H2O2. This inactivation of GluRS1 in cells exposed to H2O2 might imply a reduction in intracellular Glu-tRNAGlu levels. A concomitant reduction in heme levels in A. ferrooxidans after treatment with H2O2 was also observed. In E. coli, reduced GluRS activity was also correlated with decreased Glu-tRNAGlu levels [21]. Reduced Glu-tRNAGlu availability could increase competition for this substrate and thereby affect its partition to heme and protein biosynthetic pathways. Thus, we hypothesize that oxidative stress might enhance competition between these biosynthetic pathways for use of Glu-tRNAGlu. Our data using recombinant purified proteins from A. ferrooxidans revealed that upon treatment with H2O2, both GluTR activity and GluTR stimulation by GSAM are reduced. Furthermore, we observed that H2O2 had no effect on the binding of Glu-tRNAGlu to EF-Tu. When competing for the substrate, treatment of these molecules with H2O2 favored the binding of Glu-tRNAGlu to EF-Tu over GluTR. Although it remains to be shown empirically, these data lead us to speculate that under oxidative stress, the partitioning of Glu-tRNAGlu to protein translation might be favored over heme biosynthesis. Although increased heme turnover cannot be ruled out, this conjecture correlates well with the lower heme levels in cells treated with H2O2. Since heme and its precursors generate ROS [3,4,5,6], reduced partitioning of Glu-tRNAGlu to heme biosynthesis in A. ferrooxidans could favor cell survival when exposed to oxidative stress. It has been described that in Cucumis sativus, the ROS producer methyl viologen decreases ALA synthesis, likely by inactivating GluTR and inhibiting GluTR–GSAM complex formation [22]. Furthermore, other mechanisms to avoid the accumulation of toxic heme intermediates exist. In Salmonella enteric and Rhodobacter sphaeroides, H2O2 affects the transcription of genes for heme biosynthesis. In S. enteric, H2O2 decreases the transcription of hemA, which encodes GluTR, and induces the expression of hemH, which encodes ferrochelatase, the last enzyme in the heme biosynthetic pathway [23]. In R. sphaeroides, hemA is down-regulated when this bacterium is treated with H2O2 [24]. In B. subtilis, a mutation in per increases expression of the operon hemAXCDBL, which encodes the enzymes for heme biosynthesis. Secretion of overproduced porphyrins then takes place, preventing toxicity [25]. Thus, different strategies seem to have been developed in nature to overcome the potential negative effects of the accumulation of heme and its intermediates, particularly under oxidative stress conditions.

3. Experimental Section

3.1. Bacterial Strains and Culture Conditions

A. ferrooxidans ATCC 23270 was grown aerobically at 30 °C in a modified 9K medium (0.40 g/L MgSO4·7H2O, 0.10 g/L (NH4)2SO4, 0.04 g/L K2HPO4·3H2O and 33.3 g/L FeSO4). For production and purification of recombinant proteins, E. coli BL21 [DE3] or JM109 were grown in Luria–Bertani medium at 37 °C. When necessary, 100 µg/mL ampicillin were added to LB medium.

3.2. Overproduction and Purification of Proteins

All recombinant proteins from A. ferrooxidans were overexpressed in E. coli BL21 [DE3]. Recombinant GluRS and EF-Tu were expressed as GST-fusion proteins and purified by affinity chromatography using glutathione agarose as described [9,12,13,17]. After purification, the Glutathione-S-Transferase (GST) tag was removed by digestion with thrombin according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Purification of His6-tagged GluTR and GSAM was carried out with a Ni2+ affinity resin column. To obtain recombinant GluTR with reduced heme content, the protein was expressed in E. coli BL21 [DE3] in the presence of 100 µM orthophenanthroline before inducing expression with 1 mM isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) [9,17]. Purity of proteins was assessed by polyacrylamide-SDS gel electrophoresis and Coomassie blue staining. One major protein band was observed in all purified proteins except in GSAM, in which one major protein (>80%) of the expected molecular mass and two minor proteins were detected.

3.3. Preparation and Purification of tRNA Transcripts

A. ferrooxidans tRNA2Glu (UUC) was prepared by in vitro transcription [26]. The DNA template was prepared by PCR amplification of the tRNA2Glu gene cloned in pUC18. The in vitro transcription reaction mixture contained 40 mM Tris–HCl pH 8.0, 22 mM MgCl2, 2 mM spermidine, 5 mM dithiothreitol (DTT), 0.05 mg/mL bovine serum albumin (BSA), 4 mM each nucleotide triphosphate (NTP), 20 mM guanosine monophosphate (GMP), 1 U pyrophosphatase, 25 ng/µL tRNA2Glu and 0.12 ng/µL T7 RNA polymerase. The reaction was incubated for 5 h at 42 °C. Afterwards, the tRNA was purified by anionic exchange using Qiagen-tip100 columns following the recommendations of the manufacturer.

3.4. Preparation of A. ferrooxidans Cellular Extracts

A. ferrooxidans cells were collected by centrifugation, and the pellet was suspended in 10 mM H2SO4 and treated with 1 mM H2O2 for 30 min at 30 °C. After exposure to H2O2, the cells were washed twice with 10 mM H2SO4 and suspended in 60 mM HEPES (4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid) pH 8, 300 mM NaCl. The cell suspension was sonicated and the cellular debris removed by centrifugation at 15,000× g for 30 min. Next, the supernatant was ultracentrifuged at 150,000× g for 90 min to obtain cellular extracts. Proteins were measured using the Bradford procedure and the cellular extracts stored in aliquots at −80 °C until use.

3.5. GluRS Activity

The activity of endogenous GluRS1 from A. ferrooxidans was measured in cellular extracts with buffer containing 5 mM ATP, 100 µM [14C] Glu, 100 mM HEPES KOH pH 7.2, 30 mM KCl, 12 mM MgCl2, 3.7 µg cellular extract and 8.4 µM tRNA2Glu. The activity of recombinant purified GluRS1 from A. ferrooxidans was measured at 37 °C in 100 mM HEPES KOH pH 7.2, 30 mM KCl, 12 mM MgCl2, 5 mM ATP, 50 μM [14C] Glu and 0.1 μM GluRS1 [11,13]. The reaction was started by adding 2.6 µM tRNA2Glu. Aliquots were removed at different times, [14C] Glu-tRNA2Glu was precipitated with 15% trichloroacetic acid (TCA), and radioactivity was measured in a scintillation counter. When GluRS1 activity in the presence of EF-Tu was measured, 5 µM EF-Tu treated with or without H2O2 was included.

3.6. GluTR Activity

The activity of purified GluTR was determined by measuring the deacylation of Glu-tRNA2Glu. Because of the instability of the reaction product glutamate semialdehyde, it is described as the method of choice to assess the activity of this enzyme [9,15,17,22]. Aminoacylated [14C] Glu-tRNA2Glu was prepared with GluRS1 using 40 µM [14C] Glu and 10 µM tRNAGlu. After preparation, [14C] Glu-tRNA2Glu was precipitated and stored at −80 °C. GluTR activity was measured at 37 °C in 30 mM HEPES–KOH pH 7.2, 4 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.1 µg/µL BSA, 10% glycerol, 2 mM NADPH, 0.5–1.0 μM GluTR and 1–2 µM [14C] Glu-tRNA2Glu. The reaction was started by adding [14C] Glu-tRNA2Glu, and at different times aliquots were removed and the remaining [14C] Glu-tRNA2Glu/mg protein measured after precipitation with 15% TCA. To measure the inactivation rate of GluTR by H2O2, the reaction was started by adding H2O2, and at different times, aliquots were taken to determine GluTR activity. The remaining GluTR activity was determined by comparing the enzyme activity of the treated GluTR with the activity of the enzyme under the same conditions without the addition of H2O2. The remaining activity was plotted as ln N/N0 against time, where N0 and N are activity at time zero and at a given time, respectively. The slope of the lines obtained represents the first-order inactivation rate (kobs). Competition assays between GluTR and EF-Tu for Glu-tRNAGlu were carried out by measuring GluTR activity in the presence of 10 µM EF-Tu. The effect of GSAM (9 µM) on GluTR activity was measured by adding 0.1 mM pyridoxal phosphate.

3.7. Binding of Glutamyl-tRNAGlu to EF-Tu

To evaluate the binding of EF-Tu to Glu-tRNA, we measured the spontaneous deacylation of [14C] Glu-tRNA2Glu in the presence of EF-Tu as described [27,28]. To activate EF-Tu, the protein was incubated at 37 °C for 30 min in a reaction mixture containing 500 mM HEPES–KOH pH 7.2, 200 mM MgCl2, 0.8 M NH4Cl, 4.3 mM GTP, 3.2 μM phosphoenolpyruvate and 0.15 μM pyruvate kinase. The mixture for measuring the deacylation of Glu-tRNA2Glu in the presence of EF-Tu contained 30 mM HEPES–KOH pH 7.2, 4 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.1 µg/µL BSA, 1 μM Glu-tRNA2Glu and 5 μM EF-Tu. The assay was started by adding EF-Tu and was performed at 37 °C.

3.8. Protein Oxidation

Treatment of GluTR, EF-Tu and GSAM with H2O2 was performed at 37 °C for 20 min in 100 mM HEPES–KOH pH 7.2, 30 mM KCl, 12 mM MgCl2 and 250–500 µM H2O2. After treatment, H2O2 was removed by incubation with 0.1 nM catalase for 5 min at 37 °C.

3.9. Heme Measurement

Heme content was measured in the 12,000× g supernatant of formic acid extracts from A. ferrooxidans as absorbance at 398 nm [29] in an Epoch spectrophotometer (Biotek Instruments Inc., Winooski, VT, USA).

4. Conclusions

The data presented here show that H2O2 reduces heme levels and inactivates GluRS in A. ferrooxidans cells. Furthermore, our results concerning the effect of H2O2 on the enzymatic activity of GluTR, the stimulation exerted on GluTR by GSAM and the binding of Glu-tRNAGlu to EF-Tu allowed us to establish a model in which a limited supply of Glu-tRNAGlu generated by oxidative stress this aminoacyl-tRNA changes its fate, favoring the channeling of Glu-tRNAGlu to the biosynthesis of proteins instead of the biosynthesis of heme. Even though additional experiments in vivo are required to probe these statements and we cannot rule out alternative explanations, this could represent a way to avoid the accumulation of heme and its toxic intermediaries, which is more relevant under oxidative stress, when the cellular detoxifying system of oxidizing species is being depleted. In this context, beside the further investigation to establish how in vivo, the oxidative stress affects the delivery of Glu-tRNAGlu towards the protein and heme syntheses would be interesting analyzed if the partition of this substrate to the tetrapyrroles biosynthesis is also affected in other organism with high demand of heme under oxidative stress. Leptospirillum ferriphilum is an adequate model since it to be characterized by their high heme content [9,10] and share with A. ferrooxidans an ecological niche with a high heavy metal content, which generates ROS [30,31,32]. However, both bacteria have different strategies to respond to oxidative stress [33]. While in A. ferrooxidans a reduction in the production of ROS seems to be the major response, in L. ferriphilum the repairing of damaged molecules takes place [33].

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from Fondecyt, Chile 1110203 to Omar Orellana; 1120746 to Gloria Levicán; and from National Institutes of Health (NIH), USA GM065183 to Michael Ibba. Carolina Farah was the recipient of a graduate studies fellowship from Conicyt, Chile and a short-term foreign laboratory visit from Becas Chile and MECESUP UCH0714, Chile. We thank Assaf Katz for critical review of the manuscript.

Author Contributions

Carolina Farah performed most of the experimental work and contributed to discussion of the results. Gloria Levicán provided her expertise in acidophilic microorganisms and to interpretation of the results. Michael Ibba provided his expertise in the enzymatic analysis of aminoacyl-tRNA-related enzymes; contributed to carrying out several of the experiments; and contributed to discussion of the results. Omar Orellana contributed to framing the general problem; designing and providing resources for the experiments; and carrying out the project.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Heinemann I.U., Jahn M., Jahn D. The biochemistry of heme biosynthesis. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2008;474:238–251. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2008.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Panek H., O’Brian M.R. A whole genome view of prokaryotic haem biosynthesis. Microbiology. 2002;148:2273–2282. doi: 10.1099/00221287-148-8-2273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sadrzsdeh S., Graf E., Panter S., Hallaway P.E., Eaton J.W. Hemoglobin: Abiologic fenton reagent. J. Biol. Chem. 1984;259:14354–14356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pazos M., Andersen M., Skibsted L.H. Heme-mediated production of free radicals via preformed lipid hydroperoxide fragmentation. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008;56:11478–11484. doi: 10.1021/jf802359t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hiraku Y., Kawanishi S. Mechanism of oxidative DNA damage induced by δ-aminolevulinic acid in the presence of copper ion. Cancer Res. 1996;56:1786–1793. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fotinos N., Convert M., Piffaretti J., Gurny R., Lange N. Effects on Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria mediated by 5-aminolevulinic acid and 5-aminolevulinic acid derivatives. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2008;52:1366–1373. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01372-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nakayashiki T., Nishimura K., Tanaka R., Inokuchi H. Partial inhibition of protein synthesis accelerates the synthesis of porphyrin in heme-deficient mutants of Escherichia coli. Mol. Gen. Genet. 1995;249:139–146. doi: 10.1007/BF00290359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Francklyn C.S., Minajigi A. tRNA as an active chemical scaffold for diverse chemical transformations. FEBS Lett. 2010;584:366–375. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2009.11.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Levicán G., Katz A., de Armas M., Nuñez H., Orellana O. Regulation of a glutamyl-tRNA synthetase by the heme status. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:3135–3140. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611611104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yarzabal A., Brasseur G., Bonnefoy V. Cytochromes c of Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2002;209:189–195. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1097(02)00514-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Salazar J.C., Ahel I., Orellana O., Tumbula-Hansen D., Krieger R., Daniels L., Söll D. Coevolution of an aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase with its tRNA substrates. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:13863–13868. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1936123100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Levicán G., Katz A., Valenzuela P., Soll D., Orellana O. A tRNAGlu that uncouples protein and tetrapyrrole biosynthesis. FEBS Lett. 2005;579:6383–6387. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2005.09.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Katz A., Banerjee R., de Armas M., Ibba M, Orellana O. Redox status affects the catalytic activity of glutamyl-tRNA synthetase. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2010;398:51–55. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.06.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li J., Brathwaite O., Cosloy S, Russell C.S. 5-Aminolevulinic acid synthesis in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 1989;171:2547–2552. doi: 10.1128/jb.171.5.2547-2552.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kang Z., Wang Y., Gu P., Wang Q., Qi Q. Engineering Escherichia coli for efficient production of 5-aminolevulinicacid from glucose. Metab. Eng. 2011;13:492–498. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2011.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schobert M., Jahn D. Regulation of heme biosynthesis in non-phototrophic bacteria. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2002;4:287–294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.De Armas M., Levicán G., Katz A., Moser J., Jahn D., Orellana O. Cellular levels of heme affect the activity of dimeric glutamyl-tRNA reductase. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2011;405:134–139. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Luer C., Schauer S., Mobius K., Schulze J., Schubert W., Heinz D.W., Jahn D., Moser J. Complex Formation between glutamyl-tRNA reductase and glutamate-1-semialdehyde 2,1-aminomutase in Escherichia coli during the initial reactions of porphyrin biosynthesis. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:18568–18572. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M500440200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nogaj L.A., Beale S.I. Physical and kinetic interactions between glutamyl-tRNA reductase and glutamate-1-semialdehyde aminotransferase of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii. J. Biol. Chem. 2005;280:24301–24307. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502483200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang C., Perona J., Ryu K., Francklyn C., Hou Y. Distinct kinetic mechanisms of the two classes of aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases. J. Mol. Biol. 2006;361:300–311. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaspy I., Rotem E., Weiss N., Ronin I., Balaban N.Q., Glaser G. HipA-mediated antibiotic persistence via phosphorylation of the glutamyl-tRNA-synthetase. Nat. Commun. 2013;4:3001. doi: 10.1038/ncomms4001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aarti D., Tanaka R., Ito H., Tanaka A. High light inhibits chlorophyll biosynthesis at the level of 5-aminolevulinate synthesis during de-etiolation in cucumber (Cucumis sativus) cotyledons. Photochem. Photobiol. 2007;83:171–176. doi: 10.1562/2006-03-06-RA-835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Elgrably-Weiss M., Park S., Schlosser-Silverman E., Rosenshine I., Imlay J., Altuvia S. A Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium hemA mutant is highly susceptible to oxidative DNA damage. J. Bacteriol. 2002;184:3774–3784. doi: 10.1128/JB.184.14.3774-3784.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zeller T., Moskvin O.V., Li K., Klug G., Gomelsky M. Transcriptome and physiological responses to hydrogen peroxide of the facultatively phototrophic bacterium Rhodobacter sphaeroides. J. Bacteriol. 2005;187:7232–7242. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.21.7232-7242.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Faulkner M.J., Ma Z., Fuangthong M., Helmann J. Derepression of the Bacillus subtilis PerR peroxide stress response leads to iron deficiency. J. Bacteriol. 2012;194:1226–1235. doi: 10.1128/JB.06566-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sampson J.R., Uhlenbeck O.C. Biochemical and physical characterization of an unmodified yeast phenylalanine. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1988;85:1033–1037. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.4.1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roy H., Becker H.D., Mazauric M., Kern D. Structural elements defining elongation factor Tu mediated suppression of codon ambiguity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:3420–3430. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ling J., Ran So B., Yadavalli S.S., Roy H., Shoji S., Fredrick K., Musier-Forsyth K., Ibba M. Resampling and editing of mischarged tRNA prior to translation elongation. Mol. Cell. 2000;33:654–660. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.01.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kuross S.A., Rank B.H., Hebbel R.P. Excess heme in sickle erythrocyte inside-out membranes: Possible role in thiol oxidation. Blood. 1988;4:876–882. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Flora J.S., Mittal M., Mehta A. Heavy metal induced oxidative stress & its possible reversal by chelation therapy. Indian J. Med. Res. 2008;128:501–523. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.</i>Stohs S.J., Bagchi D. Oxidative mechanisms in the toxicity of metal ions. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1995;18:321–336. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(94)00159-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.López-Archilla A.I., Marin I., Amils R. Microbial community composition and ecology of an acidic aquatic environment: The tinto river, Spain. Microb. Ecol. 2001;41:20–35. doi: 10.1007/s002480000044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cortés A., Flores R., Norambuena J., Cardenas J.P., Quatrini R., Orellana O., Levicán G. Comparative study of redox stress response in the acidophilic bacteria Leptospirillum ferriphilum and Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans. In: Qiu G., Jiang T., Qin W., Liu X., Yang Y., Wang H., editors. Biohydrometallurgy, Biotech Key to Unlock Mineral Resources Value. Central South University Press; Changsha, China: 2011. pp. 354–357. [Google Scholar]