Abstract

During in vitro fertilization of wheat (Triticum aestivum, L.) in egg cells isolated at various developmental stages, changes in cytosolic free calcium ([Ca2+]cyt) were observed. The dynamics of [Ca2+]cyt elevation varied, reflecting the difference in the developmental stage of the eggs used. [Ca2+]cyt oscillation was exclusively observed in fertile, mature egg cells fused with the sperm cell. To determine how [Ca2+]cyt oscillation in mature egg cells is generated, egg cells were incubated in thapsigargin, which proved to be a specific inhibitor of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) Ca2+-ATPase in wheat egg cells. In unfertilized egg cells, the addition of thapsigargin caused an abrupt transient increase in [Ca2+]cyt in the absence of extracellular Ca2+, suggesting that an influx pathway for Ca2+ is activated by thapsigargin. The [Ca2+]cyt oscillation seemed to require the filling of an intracellular calcium store for the onset of which, calcium influx through the plasma membrane appeared essential. This was demonstrated by omitting extracellular calcium from (or adding GdCl3 to) the fusion medium, which prevented [Ca2+]cyt oscillation in mature egg cells fused with the sperm. Combined, these data permit the hypothesis that the first sperm-induced transient increase in [Ca2+]cyt depletes an intracellular Ca2+ store, triggering an increase in plasma membrane Ca2+ permeability, and this enhanced Ca2+ influx results in [Ca2+]cyt oscillation.

Keywords: in vitro fertilization; wheat (Triticum aestivum, L.) egg cell; cytosolic calcium; egg activation; thapsigargin; intracellular Ca2+ store; endoplasmic reticulum

1. Introduction

In the eggs of all animal species studied so far, fertilization induces an increase in cytosolic calcium ([Ca2+]cyt), which appears to be the primary intracellular signal responsible for the initiation of the development of the egg following fertilization [1,2,3,4,5,6]. Thus, the fertilizing spermatozoon triggers a common cascade of events by generating [Ca2+]cyt transients in the cytoplasm of the egg [7,8,9,10]. Although the pattern of this [Ca2+]cyt varies, the pulsatory rise in [Ca2+]cyt seems to be a universal phenomenon that marks the onset of egg activation among the mammalian species investigated thus far [11,12,13,14,15,16]. In sea urchin, however, a single, transient [Ca2+]cyt rise induced by fertilization was reported [17,18,19]. Therefore, one of the earliest events that occurs in the animal egg during fertilization is at least one increase in [Ca2+]cyt [20,21,22]. Furthermore, development of an inositol trisphosphate (InsP3)-induced calcium release mechanism during maturation of hamster oocytes has been demonstrated by Miyazaki et al. [13] and Fujiwara et al. [15]. From these studies, it seems to be clear that the release of Ca2+ from intracellular stores is mediated by InsP3 through the opening of InsP3-activated Ca2+-channels (InsP3receptors) on the endoplasmic reticulum.

Much less is known, however, about calcium signaling during egg activation in higher plants. This is mainly due to the inaccessibility of the female gametophyte for experimental manipulation, which makes the cellular/molecular study of fertilization-associated events in higher plants difficult (for a review, see [23,24]). Nonetheless, recently developed techniques, such as gamete isolation and in vitro fertilization of gamete pairs, offer the possibility of studying the first events associated with gamete fusion (for a review, see [25]). Exploiting a calcium-induced in vitro fertilization system, Digonnet et al. [26] reported first a fertilization-associated Ca2+ transient in the cytoplasm of the fertilized maize egg. Furthermore, recently, the protein, annexin p35, was identified in the egg cell and zygote of maize and shown to be involved in the exocytosis of cell wall materials (an important event during the development of the fertilized egg cell), which was found to be induced by a fertilization-triggered increase in cytosolic Ca2+ levels [27]. These findings suggested that egg activation in higher plants may involve mechanisms similar to those that had been found to act in mammalian fertilization and in that in a brown alga, Fucus (Phaeophyceae) [28,29].

Capitalizing on the Ca2+-selective vibrating electrode method, Antoine et al. [30] observed a Ca2+ influx spreading through the entire plasma membrane of the maize egg cell fertilized in vitro by using extracellular calcium. In this study, however, the introduction of the so-called calcium-sensitive ratio dyes into the egg’s cytoplasm, which would allow for precisely following the spatial and temporal changes in [Ca2+]cyt, was not possible, due to the failure of injecting the delicate egg cells, hence leaving important questions, such as the origin and the dynamics of the observed calcium signal, unanswered [31].

In the present study, dual-ratio imaging of cytosolic calcium [Ca2+]cyt was performed in order to investigate the characteristics of the calcium signal during fertilization in the wheat female gamete. Employing a microinjection technique elaborated by Pónya et al. [32] allowed for the injection of isolated wheat (Triticum aestivum, L.) egg cells with the calcium-sensitive ratio dye (fura-2 dextran) in liquid medium, thus making IVF (in vitro fertilization) possible following injection. This method was combined with the electrofusion procedure elaborated by Kranz et al. [33] for maize gamete fusion [33,34]. Combining these two techniques made it possible to gain quantitative data on the duration, amplitude and frequency of the [Ca2+]cyt changes observed in the fertilized wheat egg, which permits quantitative comparisons to be made between the characteristics of the calcium signal ensuing upon fertilization in the animal egg and in the female gamete of wheat, a higher land plant. In view of the structural changes that the ER goes through during the in situ development of the wheat egg [35], which could be correlated with a change in the calcium storage capacity of the ER and based on the observation made by Pónya et al. [36] that in the receptive wheat egg cell the main calcium store is the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), the dynamics of changes in [Ca2+]cyt in wheat female gametes isolated at different maturational stages and fertilized in vitro were followed. Egg protoplasts were isolated at different developmental stages defined according to the time (measured as days after emasculation; DAE) elapsed from emasculation, carried out at a certain developmental window of the male gametophyte. Three maturational windows were defined for the female gametes to be isolated for the experiments: (1) three DAE, at which isolated eggs were considered immature; (2) six DAE, yielding mature, receptive eggs; and (3) 11 DAE, the isolation of overmature female gametes.

The advantage of electrofusion, i.e., unlike the calcium-induced gamete fusion system [34], fusion is possible in calcium-free medium, was exploited to determine if and how intracellular calcium stored in intracellular calcium stores in the wheat egg plays a role in calcium signaling during fertilization with respect to the presence or omission of extracellular calcium in the fusion medium. For this purpose, IVF was carried out either in Ca2+-free fusion medium or in fusion medium containing CaCl2.

Based on previous findings of Pónya et al. [35] that the mature wheat egg has only a few vacuoles and an extensive, well-developed endoplasmic reticulum (ER) system shown by Pónya et al. [36] to be the main intracellular Ca2+ store in the female gamete of wheat and also on the preliminary result that [Ca2+]cyt elevation was also seen in egg cells incubated and fused in Ca2+ free medium (therefore, the calcium rise that was observed needed to have originated from an internal calcium store), the ER was assumed to be the origin of the repetitive [Ca2+]cyt transients observed in mature, fertilized wheat (T. aestivum, L.) egg cells. To test this hypothesis, a pharmacological approach was employed to examine the origin of the fertilization-associated [Ca2+]cyt change in the egg cytoplasm. Wheat female gametes were treated with thapsigargin, an inhibitor of Ca2+-pumps [37,38], which proved to be able to specifically block Ca2+-ATPases in the ER, while leaving the plasma membrane calcium-pumps unaffected, at least at a certain concentration (10 μM) of the drug added to the fusion medium.

2. Results

2.1. Imaging [Ca2+]cyt during in Vitro Fertilization (IVF) of Isolated Egg Cells Developed in Situ

The possibility of the injection of fura-2 dextran into egg cells isolated from wheat allowed for the dual-excitation-based ratio approach to be used to measure [Ca2+]cyt changes in the cytoplasm of the in vitro fertilized female gamete.

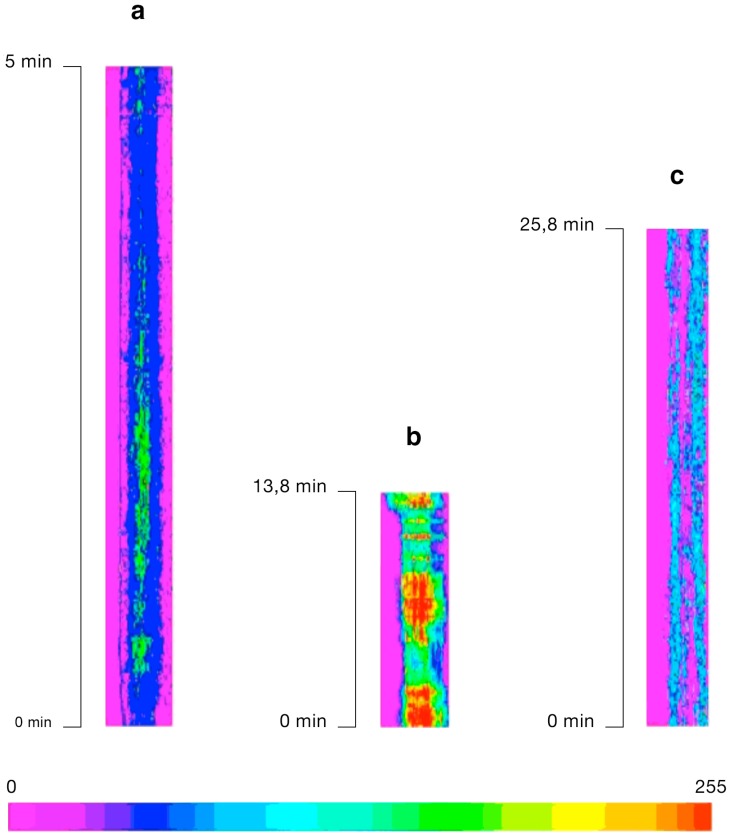

First, the [Ca2+]cyt response of immature egg cells isolated three days after emasculation (DAE) (i.e., shortly after the third mitosis of the female gametophyte was completed) to sperm incorporation was investigated. During the recording period, [Ca2+]cyt did not rise above the basal level estimated by applying the GPT transformation (Grynkiewicz, Poene and Tseng calibration for calcium ion concentration with fluorescence ratio dyes) [39] to the fluorescence ratio image sequences (n = 36). As shown in Figure 1a, [Ca2+]cyt rose only slightly above the basal level measured along an axis passing through the sperm entry site in immature egg cells isolated three DAE, whereas in Figure 1b, distinct (red) bands indicate the pulsatile elevations of [Ca2+]cyt in a receptive egg cell (irrespective of whether the axis along which the measurement was taken passed through the sperm entry site or through the region of origin of [Ca2+]cyt rise); whereas no [Ca2+]cyt elevation could be detected in overmature egg cells isolated 18 DAE (n = 17) (Figure 1c).

Figure 1.

Calcium dynamics in reconstructions of temporal sections obtained with the Line Image function of the Lucida software. The line trace plot is represented as pixel intensities converted into pseudocolor values in the Line Image. Rows in the Line Image correspond to successive images (x) along the active dimension, time (t). Thus, the Line Image is an (x,t) plot showing [Ca2+]cyt change along an axis through the “stack” image composed of the overlaid images taken successively during [Ca2+]cyt measurement. The increase in [Ca2+]cyt is represented by yellow-red bands. The bar represents a pseudocolor code of the pixel values digitized to 256 grey levels. (a) Line Image of an egg cell isolated three DAE, injected with fura-2 dextran and ratio-imaged following electrofusion with a sperm cell. The axis along which the [Ca2+]cyt changes were measured passed through the sperm entry site; (b) [Ca2+]cyt changes over time in a receptive egg cell (isolated six DAE) microinjected with fura-2 dextran and fertilized in vitro; (c) Time-lapse series of an axis “drawn” through time, the active dimension, in an overmature (18 DAE) egg cell fertilized in vitro following fura-2 dextran injection.

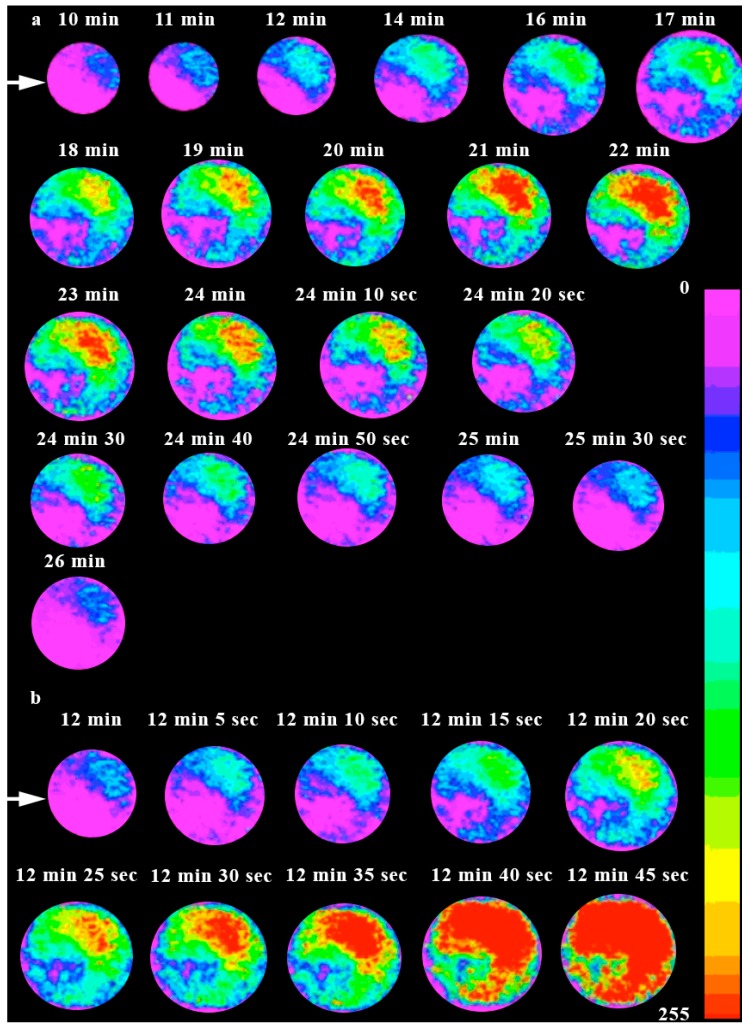

In the time series of ratio [Ca2+]cyt images shown in Figure 2a,b, changes in [Ca2+]cyt were observed to arise away from the sperm entry site. In the case of immature egg cells, this rise in [Ca2+]cyt was confined to a certain region of the cell away from the sperm entry site, whereas fully mature egg cells exhibited [Ca2+]cyt waves sweeping through the entire cell at the focal plane of sperm entry (Figure 2a, Figure 2b).

Figure 2.

[Ca2+]cyt ratio-imaging in immature and mature wheat egg cells at the focal plane of sperm incorporation. (a) The rise of a truncated [Ca2+]cyt transient confined to a distinct region of the cytoplasm of the female gamete of wheat isolated three DAE and fused with a sperm cell. [Ca2+]cyt elevation ensued approximately 10 min after sperm–egg fusion. Note that the site of the origin of the [Ca2+]cyt transient is away from the fusion site (indicated by the arrows) of the male gamete and that the diameter of the pseudocolor-coded image sequences changes, so as to enhance the representation of the change in [Ca2+]cyt elevation in such a way that the larger the diameter of the image, the higher the [Ca2+]cyt concentration; the arrow indicates the sperm entry site; (b) [Ca2+]cyt wave of a mature (six DAE) wheat egg cell sweeping through the whole cytoplasm of the cell approximately 12 min after plasmogamy. Note that the origin of the [Ca2+]cyt wave is away from the sperm entry site. The arrow shows the sperm entry site.

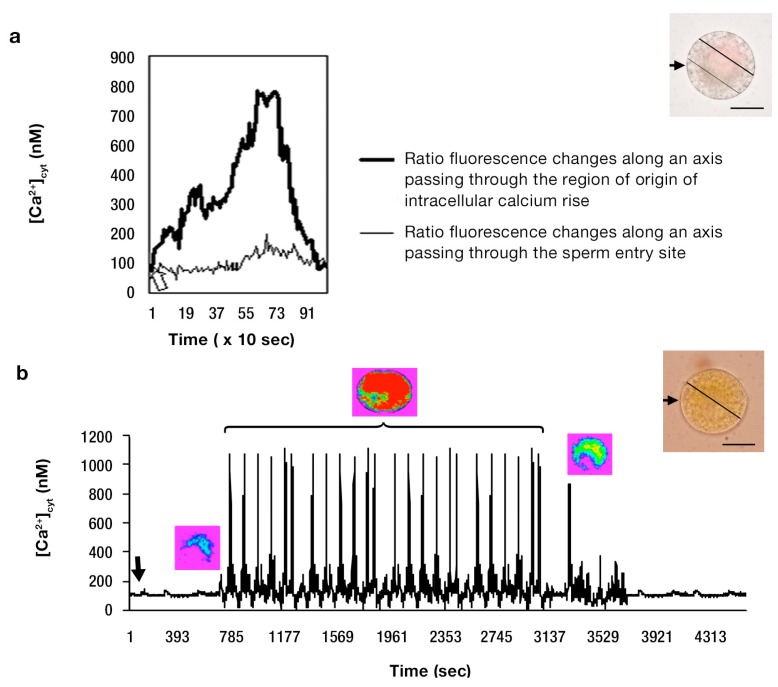

The finding that in the in vitro fertilized, immature egg protoplasts, the [Ca2+]cyt rise was confined to a distinct region of the cytoplasm away from the site of sperm incorporation (see Figure 2a) was corroborated by calculating (using the Lucida software, Kinetic Imaging, Merseyside, UK) the average fluorescence intensity along an axis (drawn with the computer mouse) passing through the region of the origin of the rise in [Ca2+]cyt across the time-series of the successive images. The quantitative data obtained were subsequently compared with those gained in the same way, but depicting average [Ca2+]cyt changes along an axis passing through the sperm entry site (i.e., along an axis drawn through the time-series of the stack of the successive images, which did not pass through the origin of the [Ca2+]cyt change (Figure 3a).

Figure 3.

The 340/380 nm excitation ratios of fura-2 dextran-injected wheat egg cells showing [Ca2+]cyt variations in response to the different maturational stages of the batch of the egg cells used for in vitro fertilization. (a) Typical, fertilization-associated [Ca2+]cyt rise in an in vitro fertilized wheat egg cell developed in situ and isolated three DAE (the arrow denotes 10 min after in vitro fertilization (IVF)). The bright field image (inset) at the right upper corner shows the lines (axes) of pixels along which the pixel intensities (i.e., the changes in calcium concentrations) were measured through the active dimension, time; the arrow shows the site of sperm incorporation, and the bar represents: 15 µm; (b) Representative [Ca2+]cyt changes occurring concomitantly upon in vitro fertilization of mature wheat egg cells (isolated at six DAE). This dynamics of the [Ca2+]cyt change could be seen in 66 out of 80 (81.5%) egg cells fertilized with the sperm (the arrow indicates the time at which fusion between the sperm and the egg cell occurred). The [Ca2+]cyt peak elicited by the sperm ensued 10 min after the in vitro fusion of the gametes of opposite sexes. The pseudo-colored images (insets) give a visual representation of the change in [Ca2+]cyt, whereas the bright-field image shows the axis along which the pixel intensities (i.e., the changes in calcium concentrations) were measured. The arrow shows the site of sperm entry, and the bar represents: 20 µm; (c) A slow [Ca2+]cyt rise induced by sperm cell fusion in an overmature egg cell isolated 11 DAE (the arrow shows the time lapse, 17 min, between sperm–egg fusion and the commencement of the slow [Ca2+]cyt elevation). The bright-field image at the right upper corner shows the axis along which the pixel intensities (i.e., the changes in calcium concentrations) were measured. The arrow shows the site of sperm entry, and the bar represents: 25 µm.

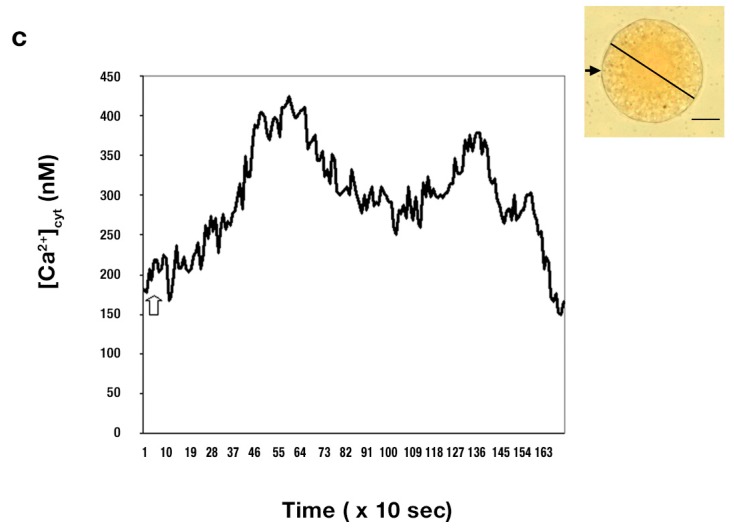

The resting level of [Ca2+]cyt in unfertilized, mature wheat egg cells was estimated from the ratio equation and found to be 109 ± 27 nM (n = 66), which approximately 10 ± 2 min (n = 66) after gamete fusion rose to 1100 ± 21 nM (n = 66) as the highest [Ca2+]cyt peak reached its summit, which was followed by a global elevation in [Ca2+]cyt, as was observed at the focal plane corresponding to the Sperm Entry Site (SES) throughout the whole cell (Figure 2b and Figure 3b). In receptive wheat (T. aestivum, L.) egg cells, the first [Ca2+]cyt rise was typically followed by several [Ca2+]cyt pulses, the oscillatory maximum of which was estimated to be 1180 ± 40 nM (n = 66), as the resting [Ca2+]cyt level had increased about 13-fold when the [Ca2+]cyt spikes reached their peak (Figure 3b). The magnitude of the average global [Ca2+]cyt rise did not exceed 442 ± 15 nM (n = 66) and usually corresponded to about a 10-fold increase (1100 ± 21 nM) (n = 66) (Figure 3b). The calculated propagation velocity of the wave front was found to be 0.9 ± 0.4 µm/s (n = 66). A typical measurement of [Ca2+]cyt in egg cells isolated at 11 DAE and fertilized with viable, mature sperm cells is depicted in Figure 3c. Isolated at this maturational stage, the fertilized egg protoplasts showed a delayed [Ca2+]cyt rise compared to that of receptive eggs. The last developmental stage at which changes in [Ca2+]cyt were elicited by the sperm cell in isolated egg cells was at 11 DAE. At this maturational stage, the [Ca2+]cyt rise occurred 10 ± 3 min (n = 45) later than in mature, fertilized egg cells (isolated six DAE) and presented a slow rise of [Ca2+]cyt, which reached a plateau at 424 ± 17 nM (n = 45) with a mean amplitude of 295 ± 22 nM (n = 45) 27 min post-fertilization (Figure 3c). The egg cells remained at this [Ca2+]cyt level for an additional 17 min, then at 44 ± 4 min (n = 45) after fusion, the level began to decrease, until [Ca2+]cyt could not be distinguished from the basal level (Figure 3c). Sperm-induced [Ca2+]cyt elevations characteristic of mature egg cells could not be observed in any of the cells (n = 45) isolated at this maturational stage.

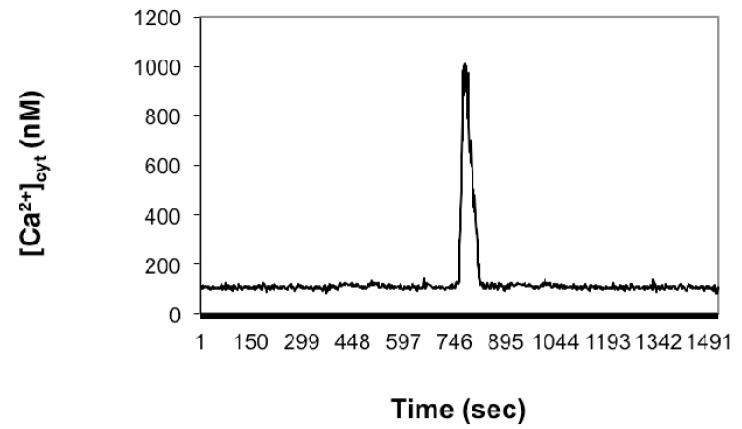

In order to assess the contribution to the [Ca2+]cyt dynamics of calcium influx across the plasma membrane of the mature egg cell, IVF was carried out in fusion medium without calcium or in IVF medium containing 10 µM (final concentration) of GdCl3, which had been previously demonstrated by Antoine et al. [30] to reproducibly and efficaciously inhibit Ca2+ influx in maize egg cells. As revealed by Figure 4, the secondary Ca2+ transients required extracellular Ca2+, because when sperm–egg cell fusion was performed in Ca2+-free IVF medium to which 10 µM (final concentration) of GdCl3 (widely used as an inhibitor of stretch-activated Ca2+-channels [30,40,41],) was added, no [Ca2+]cyt oscillation could be detected (n = 18); instead, a single [Ca2+]cyt rise occurred (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

[Ca2+]cyt dynamics in a receptive egg cell isolated six DAE and fertilized in vitro in fusion medium containing 10 µM (final concentration) of GdCl3. Time was measured from the successful incorporation of the sperm into the egg’s cytoplasm. The onset of the rise in [Ca2+]cyt elicited by the sperm ensued 12 ± 1.4 min, n = 18, following in vitro fusion of the sperm cell with the female gamete.

Suggesting that an increase in plasma membrane Ca2+ permeability is necessary for the onset of the [Ca2+]cyt peaks (using 1,2-bis-/2-aminophenoxy/-ethane-N,N,N',N'-tetraacetic acid (BAPTA) to chelate any external Ca2+ was not feasible, since it caused the loss of sperm membrane integrity within minutes after the introduction of the compound into the IVF medium, a finding corroborating that of Antoine et al. [41]), this observation is in agreement with the results of Antoine et al. [30], who measured Ca2+ influx through the egg cell plasma membrane using the Ca2+-selective vibrating probe. Although these cells (13 out of 15) were capable of cell wall regeneration, as is revealed by Figure 5, no cell division could be observed during their in vitro culture.

Figure 5.

Cell wall regeneration in an egg protoplast fused in vitro with the sperm in Ca2+-free IVF medium. The image was taken 2 h after the sperm–egg cytoplasmic continuity had been established. Scale bar, 12.5 µm.

A primary concern of the present study was to verify that the observed calcium rises had indeed physiological relevance in egg activation and in the continuation of the normal development of the fertilized egg; consequently, the measured changes in [Ca2+]cyt do not reflect a putative stress response induced by the experimental procedures (such as egg cell isolation, incubation off the maternal tissue, “excess” extracellular Ca2+ present in the IVF medium or the microinjection/electrofusion procedures) in the egg. For this purpose, numerous control experiments were carried out, such as to demonstrate that impaling the fragile egg gametoplasts with the injection needle, injection itself and withdrawing the microcapillary did not elicit “artificial” changes in [Ca2+]cyt, nor did the electrofusion procedure (without the sperm cell) trigger events leading to [Ca2+]cyt rise (see Figure S1a,b in the Supplementary). These control experiments unambiguously demonstrated that under our experimental conditions, it was possible to follow accurately the spatial-temporal changes in [Ca2+]cyt measured in wheat egg cells fertilized in vitro and that the measured [Ca2+]cyt changes are not due to stress responses, but indeed have physiological relevance to egg activation (see the Figures S1–S7 in the Supplementary).

2.2. Effect upon [Ca2+]cyt of Thapsigargin Added to the IVF Medium

Based on previous findings [36], the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) was assumed to be the origin of the observed [Ca2+]cyt rise in the fertilized egg cell. To test this hypothesis, thapsigargin, a tumor-promoting plant sesquiterpene lactone, was added to mature egg cells prior to and following in vitro fertilization, and its effect on [Ca2+]cyt dynamics was studied. Thapsigargin was previously shown to inhibit animal intracellular SERCA-type Ca2+ pumps present in the sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum [38,42] and found to have an inhibitory effect on calcium pumps residing in the ER and the plasma membrane (PM) in red beet [43].

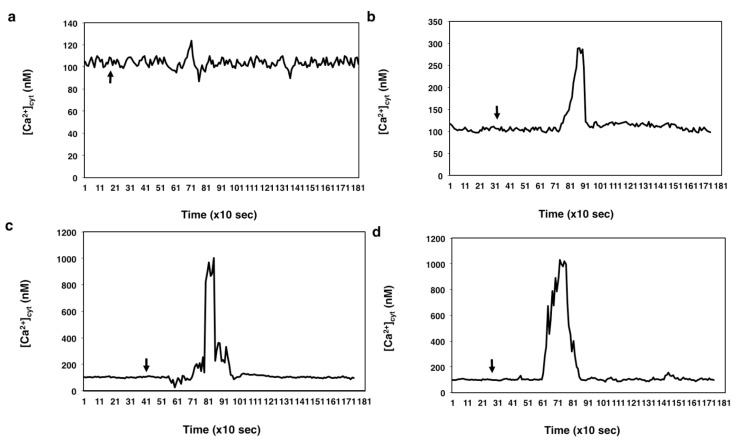

The ability of thapsigargin to deplete the calcium pumps in the wheat egg appeared to be concentration dependent, since the drug produced varying degrees of [Ca2+]cyt elevation when applied at different concentrations (Figure 6a–d).

Figure 6.

The effect of thapsigargin on [Ca2+]cyt measured in unfertilized egg cells incubated in calcium-free IVF medium. Thapsigargin was added to unfertilized eggs at: 0.1 μM (a), 1 μM (b), 10 μM (c) and at 50 μM (d). The arrows designate the times of the addition of the drug.

When applied at a 10 μM concentration, thapsigargin appeared to induce calcium release from an intracellular calcium store(s) in the wheat egg (n = 27). In unfertilized egg cells that were incubated in Ca2+-free IVF medium, the drug triggered a single Ca2+ peak with as high an amplitude as that caused by the sperm cell (Figure 6c). Increasing the concentration of the drug from 10 to 50 μM did not cause higher elevation in [Ca2+]cyt (1003 ± 11 nM, n = 27; 1003 ± 16, n = 22, respectively) compared to that triggered by incubating the cells in 10 μM thapsigargin, which suggests total depletion of the calcium pumps of the ER by thapsigargin added at 10 μM concentration to the cells (compare Figure 6c,d).

When the female gametoplasts were incubated in IVF medium containing 2 mM CaCl2, the drug, present at the same concentration (10 μM), caused a single [Ca2+]cyt rise, the peak value (1049 ± 13 nM, n = 15) of which was not significantly different from that observed when the cells were incubated in calcium-free IVF medium (1003 ± 11 nM, n = 27) (compare Figure 6c and Figure 7a), suggesting that at this concentration, thapsigargin does not exert an inhibitory effect on the plasma membrane calcium pumps.

Figure 7.

The effect of thapsigargin added at (a) 10 µM and at (b) 100 µM concentration on the cytosolic calcium level of unfertilized wheat egg cells incubated in IVF medium containing 2 mM CaCl2. Arrows: addition of thapsigargin.

However, the addition of 100 μM thapsigargin to unfertilized egg protoplasts incubated in IVF medium containing calcium (2 mM CaCl2) induced a [Ca2+]cyt rise, the peak value (1300 ± 22 nM, n = 17) of which was higher than that (1049 ± 13 nM, n = 15) produced by thapsigargin applied at a 10 μM concentration (compare Figure 7a,b) to the egg cells under the same conditions. This increase in [Ca2+]cyt was sustained and in none of the egg cells (n = 15) analyzed returned to the basal [Ca2+]cyt level.

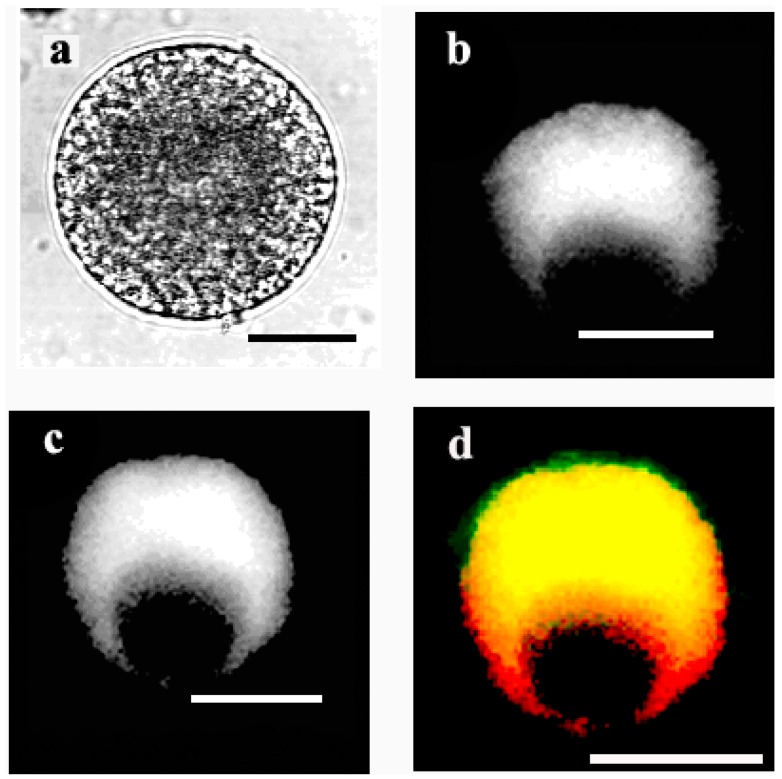

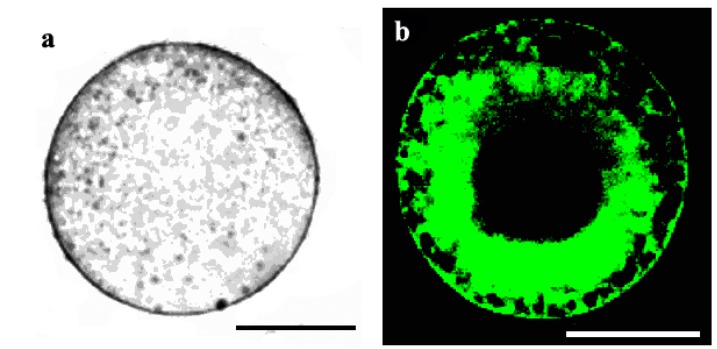

To reveal the localization of thapsigargin-sensitive calcium pumps in the wheat egg cell, the green-fluorescent BODIPY FL® thapsigargin was used. Female gametoplasts were stained with the fluorescence-labelled drug following microinjecting them with DiI (1,1'-dihexadecyl-3,3,3',3'-tetramethylindocarbocyanine perchlorate) (DiIC16(3)) which had been previously shown by Pònya et al. [36] to selectively label the endoplasmic reticulum membranes in the wheat egg. The images gained of the stained cells support the existence of thapsigargin-sensitive Ca2+-ATPase pumps tethered on the membrane meshwork of the endoplasmic reticulum (Figure 8a–d).

Figure 8.

Localization of thapsigargin-sensitive Ca2+-ATPase pumps in the wheat egg with fluorescent thapsigargin. (a) Transmission-light image of an egg cell; (b) stained with fluorescent BODIPY FL® thapsigargin, which was microinjected previously with 1,1'-dihexadecyl-3,3,3',3'-tetramethylindocarbocyanine perchlorate (DiI) to stain the ER membranes visualized in (c). (d) The overlay image of (b) and (c). Scale bars: 20, 25, 25 and 25 µm, respectively.

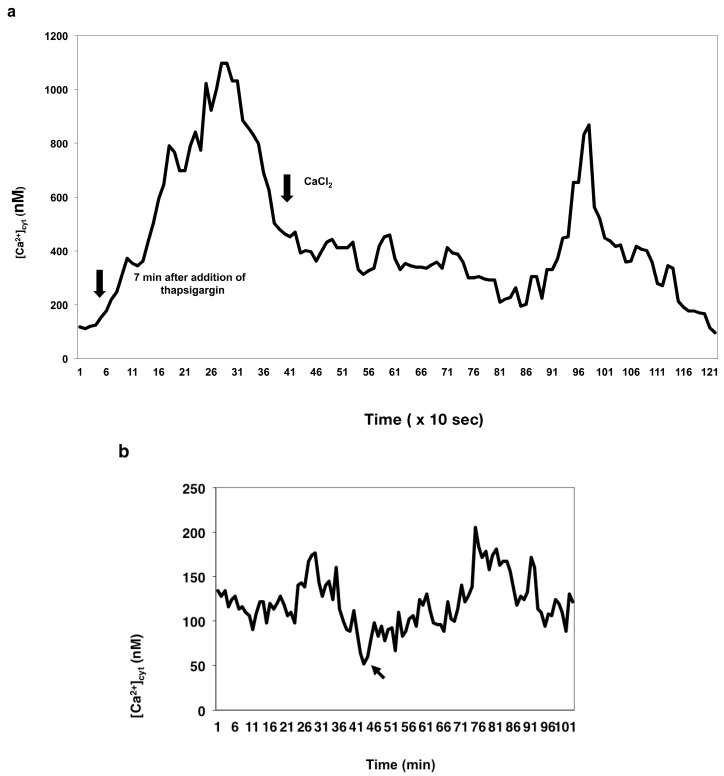

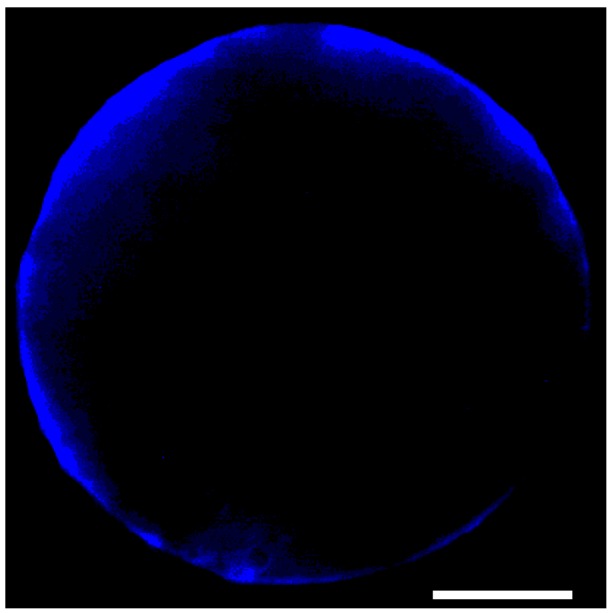

When mature egg cells were incubated in the presence of 100 μM BODIPY FL® thapsigargin (applied at the same concentration at which thapsigargin seemed to cause irreversible Ca2+ overload sof the treated cells; see Figure 7b), the fluoroprobe markedly stained both the ER and the plasma membrane, suggesting that at this concentration, thapsigargin inhibits the calcium pumps of both the ER and the plasma membrane (Figure 9a,b).

Figure 9.

Localization of thapsigargin-sensitive Ca2+-ATPase pumps with the green-fluorescent BODIPY FL® thapsigargin applied at a high (100 µM) concentration. (a) Transmission-light micrograph of an egg cell stained with BODIPY FL® thapsigargin; and (b) imaged using a confocal laser scanning (CLSM) microscope. Scale bars are: 21 and 23 µm, respectively.

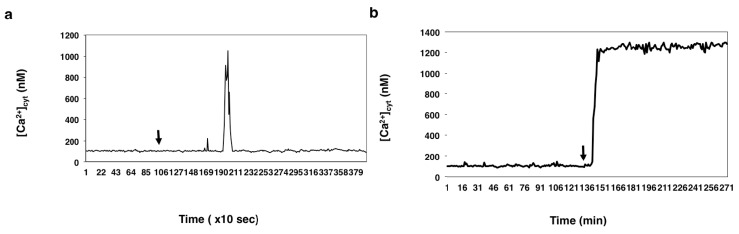

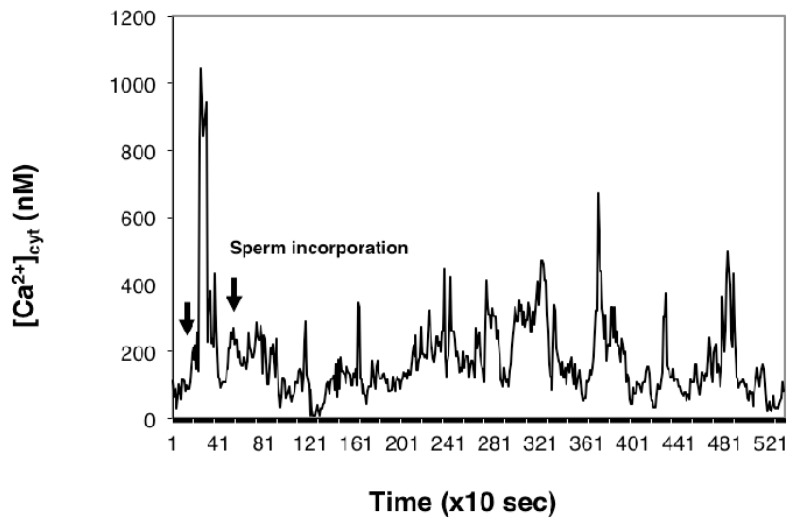

Thapsigargin activated an influx pathway for Ca2+ across the plasma membrane, because a second surge in Ca2+ was observed (in 23 out of 28 egg cells; 82.14%) when 2 mM CaCl2 was added to eggs previously incubated in thapsigargin in Ca2+-free IVF medium (Figure 10a,b).

Figure 10.

Thapsigargin treatment of isolated wheat egg cells hints at the involvement of an intracellular calcium store in the calcium release mechanism triggered by sperm fusion. (a) Thapsigargin activates divalent cation entry in wheat female gametoplasts. The graph represents the change in [Ca2+]cyt in an unfertilized wheat egg incubated in thapsigargin in Ca2+-free isolation medium followed by the addition of 2 mM CaCl2; (b) In the control experiment shown, no discernable change was observed in [Ca2+]cyt over a 60-min period when 2 mM CaCl2 was added to control eggs not previously treated with thapsigargin. The arrow shows the time when thapsigargin was added to the cell.

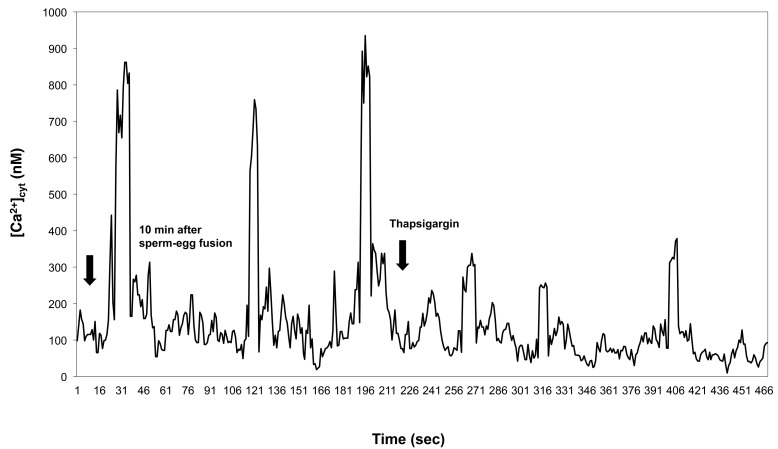

To examine the effect of thapsigargin on the Ca2+ transients at fertilization, mature egg cells treated with 10 μM thapsigargin were fused with sperm cells after [Ca2+]cyt had returned to near baseline level (approximately 8 min after adding thapsigargin to the IVF medium).

As Figure 11 depicts, in egg cells incubated in thapsigargin, the amplitude of the [Ca2+]cyt transients (that were observed in mature egg cells fused with the sperm) was substantially reduced.

Figure 11.

Thapsigargin reduces the amplitude of the sperm-induced transients. Representative [Ca2+]cyt measurement in which an egg cell following incubation in IVF medium containing 2 mM CaCl2 was treated with 10 μM thapsigargin and fertilized immediately after the thapsigargin-induced transient increase in [Ca2+]cyt. The first arrow on the left points to the time (7 min) that elapsed from the time of adding thapsigargin to the IVF medium.

Thapsigargin added following sperm–egg fusion did not produce an increase in [Ca2+]cyt comparable with that triggered by thapsigargin alone; [Ca2+]cyt transients continued for some time, and in all cases analyzed (n = 25), thapsigargin suppressed the sperm-induced [Ca2+]cyt transients observable during fertilization of the receptive wheat egg (Figure 12).

Figure 12.

Thapsigargin suppresses [Ca2+]cyt transients following sperm–egg fusion. Egg cells were fertilized in vitro followed by the addition of thapsigargin after the third sperm-induced [Ca2+]cyt transient ensued (the first arrow on the left indicates 10 min post-fertilization).

3. Discussion

3.1. [Ca2+]cyt Changes during IVF of Wheat Egg Cells

Antoine et al. [41] by simultaneously monitoring extracellular Ca2+ flux and [Ca2+]cyt by employing the Ca2+-vibrating probe and the calcium-sensitive dye fluo-3, found that inhibition of the rise in [Ca2+]cyt observed in the maize egg after sperm incorporation prevents both egg activation and a global Ca2+ influx, whereas inhibition of the Ca2+ influx does not impede [Ca2+]cyt elevation nor egg activation. These findings are in agreement with our observation that a single [Ca2+]cyt rise appeared sufficient to trigger egg activation in mature wheat egg cells fused with the sperm in calcium-free IVF medium, as demonstrated by cell wall formation. Antoine et al. [41] found that the measured Ca2+ influx preceded the detected rise in [Ca2+]cyt. However, when the Ca2+ channels in the egg’s plasma membrane were inhibited by Gd3+, the sperm cell still could fuse with the egg cell in spite of the blocked Ca2+ influx, and the cytoplasmic calcium increase still occurred, presumably due to calcium release from intracellular stores [31]. This observation is important from the angle that it allows the angiosperms to be included in the general model of multicellular organisms in which increased cytoplasmic calcium was shown to be sufficient to induce egg activation [31]. Together with the cytoplasmic calcium increase, the signs of egg cell activation (egg contraction and cell wall deposition) were also observed in Gd3+-treated cells [41], indicating that calcium influx is not a prerequisite for creating an increased [Ca2+]cyt. These authors proposed that the observed calcium influx instead might be needed for sperm incorporation and subsequent karyogamy. This hypothesis implies that in planta, the egg cell of flowering plants may have a significant extracellular calcium store at its disposal during fertilization. Indeed, Zhao et al. [44] using pyroantimonate precipitation showed that a putative extracellular source of calcium for fertilization could facilitate calcium uptake in the fertilized egg cell of rice via a pool of loosely bound calcium localized in the apoplast of the embryo sac.

Contrary to the observation made by Digonnet et al. [26], who measured only a single, long-lasting elevation in [Ca2+]cyt, our results show that when isolated at the time window of full receptivity, the wheat egg reveals oscillatory changes in [Ca2+]cyt upon sperm cell incorporation. Digonnet et al. [26] found that there were variations in the duration of the measured Ca2+ rise, which they surmised to reflect varying degrees of egg cell maturity, as had been reported by Mòl et al. [45]. Thus, the different pattern of calcium dynamics in the fertilized egg cell of maize and that of wheat egg may (at least in part) be explained by the differing maturational stages of the batch of the egg cells and/or by the different methods (calcium-induced fusion versus electrofusion) used to induce fusion between the gamete pairs. The possibility that the dynamics of calcium signaling of fertilization has species-specific characteristics in angiosperms cannot be excluded.

How the observed pulsatile [Ca2+]cyt is generated in the fertilized wheat egg cell remains to be elucidated. In the thoroughly studied animal systems, several models were proposed to expound the generation of repetitive [Ca2+]cyt rises in non-excitable cells [46,47]. These models differ as to the type of feedback mechanism surmised to regulate Ca2+ release and InsP3 production and as to whether both Ca2+ and InsP3 or only Ca2+ is thought to oscillate. Whether either of these models can be adopted in explaining the observed [Ca2+]cyt changes elicited by sperm incorporation into the wheat female gamete, or different mechanisms are involved, remains to be investigated. In the wheat egg cell, unlike many animal cells and maize, no [Ca2+]cyt wave arising at the site of sperm entry was apparent, neither could any local increase in [Ca2+]cyt be detected at the sperm entry site (Figure 2a,b). This finding is in agreement with that of Roberts et al. [28], who found no evidence for any localized increase in [Ca2+]cyt in the Fucus egg at the sperm entry site, and suggests a secondary messenger molecule that is responsible for transducing the cue delivered by the sperm cell deep into the cytoplasm-rich region of the egg.

The truncated, spatially-confined [Ca2+]cyt waves seen in immature egg cells (Figure 2a) might be explained by an insufficient calcium storage capacity of the intracellular calcium store(s) in immature egg cells. This hypothesis lends credit to the observation of Pònya et al. [36] that the Ca2+ storage capacity of the ER in the immature egg cell is much less than that in the receptive egg. The “atypical” [Ca2+]cyt dynamics revealed by overmature wheat (T. aestivum, L.) egg cells (Figure 3c) may be accounted for by a non-functioning (or insufficient) intracellular calcium store, but the possibility of InsP3-sensitive channel inactivation caused by protein kinases interfering with coincidence signaling cannot be ruled out (single-cell measurements of protein kinases in egg cells of flowering plants have not been achieved as of yet).

3.2. The Possible Origin of the [Ca2+]cyt Transients

In the present study, the advantage of electrofusion over calcium-induced fusion [48] (i.e., it does not require calcium in the fusion medium to bring about fusion) was exploited in order to establish the origin of the [Ca2+]cyt rise and the contribution of extracellular calcium to the observed [Ca2+]cyt elevations. This fusion method combined with a pharmacological approach allowed for addressing these questions. First, unfertilized wheat egg cells incubated in calcium-free IVF medium were treated with thapsigargin. Thapsigargin was mainly used in animal systems and shown to block ER/SR Ca-ATPases without interfering with the plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPases [37,38]. Its action is based on preventing reuptake from leaky stores, hence elevating [Ca2+]cyt in a variety of cell types without stimulating the production of inositol polyphosphates [49,50]. The specificity of thapsigargin action in animal cells is thought to depend on the presence of a recognition site for the inhibitor on all the SR/ER ATPases that is absent from the PM Ca2+-ATPase and other P-type ATPases [51]. In contrast, thapsigargin was found to have an inhibitory effect on both ER and PM calcium pumps in isolated membrane vesicles of red beet cells [43]. Our observations, nonetheless, suggest that thapsigargin at a certain concentration range selectively inhibits the transport activity of the ER calcium pump in the wheat egg cell, whereas it has little effect on the plasma membrane Ca2+-ATPase. This assumption is based on our findings that:

-

(1)

In the unfertilized egg incubated in IVF medium without extracellular Ca2+, thapsigargin at a 10 µM concentration caused a transient increase in [Ca2+]cyt which per se had to originate from an intracellular calcium store.

-

(2)

Since thapsigargin is an irreversible inhibitor of calcium pumps, the single and rapidly decreasing [Ca2+]cyt rise (see Figure 6c,d) suggests that thapsigargin, added at concentrations of 10 and 50 µM, did not interact with the plasma membrane calcium pumps, or if yes, not to the extent that would have prevented them from functioning properly, i.e., pumping the “extra” calcium out of the cytosol; otherwise, the [Ca2+]cyt would have remained at a high level for a much longer time (due to the irreversible depletion of both the ER and PM Ca2+-ATPase). It may be reasoned, however, that other intracellular Ca2+ pumps, such as those located, e.g., in the Golgi apparatus membrane or on vacuole membranes, may have remained unaffected by thapsigargin, which could still facilitate sequestering Ca2+ into the Golgi apparatus or into vacuoles. Indeed, Ordenes et al. [52] identified thapsigargin-sensitive Ca2+ pump activity present in the Golgi apparatus vesicles isolated from the elongation zone of etiolated pea epicotyl.

-

(3)

Nevertheless, imaging of fluorescent thapsigargin-stained egg cells at which the fluorophore was added at a concentration of 10 µM failed to reveal any thapsigargin-binding sites other than those localized in the ER membranes visualized by injecting DiI into the isolated wheat egg cells (see Figure 8a–d). Since imaging Dil injected into wheat egg cells proved to be a reliable and effective method in visualizing specifically the ER membranes in the wheat female gamete [36], this observation argues in favor of our hypothesis. Additionally, Pònya et al. [36] identified the ER by CTC (chlortetracycline) labelling to be the main calcium store in the wheat egg cell. Thus, it seems unlikely that calcium leaking from the ER into the cytoplasm upon the addition of thapsigargin could be sequestered into other cell organelles.

-

(4)

The observation that 10 µM thapsigargin treatment caused Ca2+ release in unfertilized egg cells incubated in IVF medium without or with calcium and that in the latter case, the [Ca2+]cyt transient was not significantly higher compared to that measured when cells were incubated in calcium-free medium (see Figure 6c and Figure 7a) suggests that thapsigargin at this concentration has little effect on the plasma membrane ATPase; otherwise the [Ca2+]cyt rise would have been much higher when extracellular calcium was present in the incubation medium due to the cell’s “succumbing” to the tremendous (20,000-fold: 0.1 µM intracellular versus 2 mM extracellular Ca2+ concentration) “Ca2+ pressure” on the cell membrane. In concert with this assumption, when applied to unfertilized egg cells incubated in IVF medium containing 2 mM CaCl2, thapsigargin at a high concentration (100 µM) caused a rapidly rising increase in [Ca2+]cyt, the peak value of which was higher than that observed in wheat egg cells treated with thapsigargin at 10 µM (compare Figure 7a,b). The plateau reached in [Ca2+]cyt was sustained during [Ca2+]cyt measurement (n = 17) and only slightly diminished due to photobleaching of the calcium-sensitive dye. This finding lends credit to the hypothesis that at this concentration, Ca2+ overload occurs in the cell, most probably due to the inhibitory effect exerted by thapsigargin on the plasma membrane calcium pumps.

It may, therefore, be concluded that the sensitivity of the ER and the PM calcium pumps to different concentrations of thapsigargin differs in the wheat egg, which may be explained (at least in part) by the proposed mode of action of the compound: thapsigargin, being highly hydrophobic, is believed to partition selectively into the phospholipid component of membranes, where it interacts with the hydrophobic domains of membrane proteins, hence affecting lipid-protein interactions and, consequently, general ATPase activity. The differing degree of sensitivity of the ER and the PM Ca2+-ATPase to thapsigargin could, therefore, be attributed to differences in hydrophobicity of the two types of membranes. This notion is corroborated by our finding that fluorescent thapsigargin at a 100 µM concentration stained both the ER and the plasma membrane (see Figure 9a,b).

In the present study, thapsigargin was used to explore the possibility that the first sperm-induced [Ca2+]cyt transient acts as a signal for an increase in plasma membrane Ca2+ permeability. We examined the hypothesis that the [Ca2+]cyt oscillation observed in mature egg cells following fertilization is due to an increased Ca2+ permeability and subsequent filling and periodic emptying of an intracellular Ca2+ store. The depletion of intracellular Ca2+ by thapsigargin in the analyzed egg cells increased Ca2+ influx through the cell’s plasma membrane, since an immediate elevation in [Ca2+]cyt could be observed when Ca2+ was added to unfertilized eggs previously treated with thapsigargin and incubated in IVF medium without extracellular calcium (Figure 10a). Refilling the ER with calcium seems to be a prerequisite for [Ca2+]cyt oscillation, as was shown by the suppression of the [Ca2+]cyt transients by thapsigargin added to the fusion medium preceding fertilization or after the sperm cell-induced [Ca2+]cyt transients ensued (Figure 11 and Figure 12).

These results hint that the repetitive Ca2+ transients observed in the mature, fertilized wheat egg protoplasts are produced by the release of Ca2+ from the ER that is filled by a thapsigargin-sensitive Ca2+ pump. The first sperm-induced [Ca2+]cyt transient depletes the ER in the receptive wheat egg and thereby enhances plasma membrane permeability to Ca2+. The transient emptying of the ER might then be due to Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release mediated by an increase in [Ca2+]cyt or by the accumulation of Ca2+ within the cisternae of the endoplasmic reticulum.

The present study demonstrates that repetitive Ca2+ transients in the in vitro fertilized, mature wheat egg cell are associated with Ca2+ influx across the plasma membrane, which can be suppressed by inhibiting the ability of the endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase to sequester Ca2+. The oscillation in [Ca2+]cyt seems to require extracellular calcium, since omitting extracellular calcium from the IVF medium suppressed it. Based on our findings, it might be speculated that in planta, the calcium depletion occurring dramatically following sperm–egg fusion in wheat synergids, as was demonstrated by Chaubal and Reger [53], supplies extracellular calcium needed for these repetitive calcium changes seen in the cytoplasm of the fertilized wheat egg cell. It may be hypothesized that calcium signaling, surmised to be involved in the cascade events of signal transduction leading to egg activation, is an event in the fertilized egg cell that sets in within seconds following sperm–egg fusion, hence somehow contributing to the avoidance of polyspermy. However, Digonnet et al. [26] observed that adhesion between the two gametes of opposite sexes in the course of fusion brought about by extracellular calcium lasted for 30 min without further membrane fusion, during which time, no variation in fluorescence emission signal occurred. Therefore, it appears that the [Ca2+]cyt changes detected in both species (maize and wheat) ensue after a relatively longer “lag period” (30 and 10–12 min in maize and wheat, respectively), rendering it doubtful that [Ca2+]cyt in these angiosperm species have (direct) relevance in mechanisms ensuring the avoidance of polyspermy. However, it appears to be clear that in a number of described systems, the intracellular calcium waves induce cortical vesicle fusion with the plasma membrane, leading to the elevation of the so-called “fertilization envelope”, which acts as a mechanical barrier to further sperm penetration, hence indirectly implying changes in [Ca2+]cyt. This is thought to be a slow block to polyspermy. Whether elevations observed in [Ca2+]cyt in the wheat egg have relevance in mechanisms ensuring the avoidance of polyspermy remains to be elucidated. In any case, the difference observed in the two species between the time lapse measured from plasmogamy to the onset of the elevation in [Ca2+]cyt may be explained by the different in vitro fusion systems used (although surmising a species-dependent variation of the dynamics of intracellular calcium changes cannot be disregarded).

4. Experimental Section

4.1. Plant Materials

The spring wheat (Triticum aestivum, L.) genotype “Siete Cerros” was grown in a growth chamber using a 16-h light period (light intensity: 350 Em−2·s−1) at 17/15 °C day/night temperature under 70% relative humidity.

4.2. Gamete Isolation

Emasculation of the spikes was always carried out precisely when approximately 80% of the microspores were in the late-uninucleate stage. The spikes were harvested at 3, 6, 11, 15 and 18 days after emasculation (DAE), and the ovaries were carefully removed using forceps. Subsequently, the egg cells were isolated from the ovules according to Pònya et al. [32]. The isolated cells were individually transferred with a microchip-controlled micropump (A203XVZ, World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL, USA) into droplets of mannitol (600 mOsm·kg−1), each dispensed in sterile plastic dishes covered with inert oil (voltalef PCTFE oil type 10S, Atochem, Newbury, Berkshire, UK) to avoid evaporation. Following the taking of samples from fresh pollen populations to check their viability [54], sperm cells were isolated using hypoosmotic shock [33] and placed via a micropump system to the egg cells incubated in fusion droplets.

4.3. Microinjection of Live Egg Cells and Visualizing the Fluorophores

The microinjection procedure employed to introduce the calcium-sensitive dye, fura-2 dextran (Mr = 10,000, Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA) into the female gametes has been described in detail by Pónya et al. [32]. The injected aliquots of the probe were about 1%–3% of the cell volume estimated by meniscus displacement, assuming the volume of a cone for the tip of the pipette. During the control experiments of the injection procedure, “blind” injections were performed, which were possible by positioning the microneedle in close proximity of the cell surface before switching to the epifluorescence mode of the microscope to launch the [Ca2+]cyt measurements. In this manner, the incremental positioning of the micromanipulator arm by the step motor could reproducibly drive the microcapillary into the cytoplasm of the firmly immobilized egg cell. The signal for injection was triggered by pushing a pedal, which generated a “start”-signal recorded by a computer.

4.4. The IVF Procedure

The electrofusion of selected pairs of isolated gametes was implemented following the method of Kranz et al. [33]. Electrofusion was carried out using a pair of platinum wire electrodes (diameter: 50 μm) on an electrode support controlled by hydraulic microdrives (MO-104, Narishige International Ltd., London, UK). Fusion between the gamete pairs was induced by single or multiple negative DC pulses (50 μs, 0.8 kV·cm−1) delivered by a cell fusion instrument (CF-150; BLS—Biological Laboratory Equipment, Budapest, Hungary) following the dielectric alignment of the gamete pairs on one of the electrodes by using an AC field (1 MHz, 75 V·cm−1). The fusion droplets were composed of 600 mOsmol mannitol containing 2 mM CaCl2 (pH 6.0). Thapsigargin and calcium-containing solutions were directly added by a microsyringe controlled by a micromanipulator to the fusion droplet in an equal volume of medium to ensure rapid and thorough mixing.

4.5. Cell Wall Detection

For cell wall visualization egg cells fused with the sperm were stained for 5 min in the dark in the IVF medium containing 0.001% Triton X-100 and calcofluor white M2R (Sigma–Aldrich, St. Luois, MO, USA), then washed twice in a 600 mOsmol/kg mannitol solution before observing them on an inverted microscope (Nikon Eclipse TE-300, Nikon Instruments Europe B.V., Amstelveen, The Netherlands) equipped with epifluorescence.

4.6. Measurement of Fura-2 Dextran Fluorescence

Fura-2 dextran-loaded egg cells were observed with a Zeiss Axiovert 35M inverted microscope equipped with a 75-W xenon epifluorescence burner (Osram Licht AG, Munich, Germany). The images were obtained using a Zeiss Plan-Neofluar 63× oil immersion objective (1.25 N.A. (numerical aperture); Carl Zeiss Microscopy, GmbH, Jena, Germany). A rotating filter wheel (Lambda-10, Sutter Instruments, Novato, CA, USA) and a shutter apparatus were used to alternate excitation wavelengths between 340 and 380 nm. A 400-nm dichroic mirror was positioned after the shutter assembly. The emitted light was collected using a 510-nm emission filter with a 10-nm half-bandwidth. Confocal images were produced by using a laser scanning confocal system (Model M-1024, Bio-Rad Microscience Division, Hemel Hempstead, Hertfordshire, UK) coupled with a BX50F4 research microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). The cells were excited at 488 nm, and the emitted fluorescence was detected at 500–530 nm.

4.7. Image Recording and Processing

The images were recorded and digitized using an on-chip integration CCD camera (CoolView, Photonic Science, East Sussex, UK). Switching between the excitation filters was under the control of a computer connected to both the filter wheel and to the camera. The rotating filter wheel was moved to the blank position between each active image capture cycle to minimize photobleaching. Images were captured at a resolution of 256 × 256 pixels and digitized to 256 grey levels. The dark current of the CCD detector was measured prior to each series of images and subtracted during live mode. Autofluorescence was detected at excitation wavelengths of 340 and 380 nm, at which fura-2 has a spectral shift depending on the Ca2+ binding/free-acid forms, respectively. Image processing and ratio calculation were performed with the Lucida 3.53 image processing software system (Kinetic Imaging, Ltd., Bromborough, UK). The resulting ratio images were color-coded to represent different calcium concentrations determined after calibration. An in vitro (extracellular) calibration of the ratio versus free [Ca2+] was performed using Ca2+-ethyleneglycol-bis(aminoethyl ether)-N,N'-tetraacetic acid (EGTA) buffers. For the in vitro calibration, the buffer contained 0.5 µM fura-2 dextran (Mr = 10,000), 120 mM KCl, 0.5 mM MgCl2, 20 mM 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES) (pH 7.2) and 0.2 mM EGTA (with or without CaCl2). To account for the spectral changes of fura-2 fluorescence in cells and in salt solutions, due to viscosity differences [55], 2 M sucrose was added to the calibration buffers in order to increase the viscosity of the standard solutions.

The fluorescent ratio-values were converted into Ca2+ concentrations (nM) by using the Grykiewicz, Poenie and Tsien formula [39], [Ca2+] = Kd × [((R − Rmin)/(Rmax − R))Sf2/Sb2], where: [Ca2+] = the concentration of calcium ions (nM); Kd = the dissociation constant of fura-2; R = the ratio recorded under appropriate physiological conditions; Rmin = the ratio recorded at zero external calcium; Rmax = the ratio recorded in the presence of excess calcium; Sf2 = the signal at 380 nm in zero calcium; Sb2 = the signal at 380 nm in excess calcium.

4.8. Procedure of 1,1'-Dihexadecyl-3,3,3',3'-tetramethylindocarbocyanine perchlorate (DiI) Injection

The microinjection procedure used for introducing DiIC16(3) obtained from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR, USA) into the egg cells was described in detail by Pònya et al. [36].

4.9. Thapsigargin Treatment

Thapsigargin was purchased from Sigma–Aldrich Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO, USA) and prepared in a 5 mM stock solution in DMSO, which was then diluted to the appropriate concentrations (0.1–100 µM) in the medium used for IVF.

4.10. Visualization of Thapsigargin-Binding Sites in the Wheat Egg

BODIPY FL® thapsigargin was obtained from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR, USA). For localizing thapsigargin-sensitive Ca2+ pumps, egg protoplasts were incubated for 5 min with BODIPY FL® thapsigargin diluted from a stock (1 mg/mL) solution dissolved in DMSO to reach the concentration of 1 µM in the fusion medium. The cells were washed twice before images were acquired through a 40× lens on a Nikon PCM 2000 microscope.

4.11. Ca2+ Influx Inhibition with Gadolinium

Four microliters of a 1 mM stock aqueous solution of GdCl3 purchased from Sigma–Aldrich were added to the fusion medium containing 2 mM CaCl2 to obtain a final concentration of 10 µM [30].

4.12. Culture Procedures

Following IVF, the fertilized egg cells were transferred to a drop of a modified Kao 90 medium consisting of Kao 90 solution [56] supplemented with zeatin (1 mg·L−1) adjusted with mannitol to 600 mOsmkg−1 and solidified with 1% (w/v) low-melting point agarose. To enhance the elongated growth of the fusion products (see [40]), 5 µM naphthalene 1-acetic acid (NAA, auxin, Sigma–Aldrich Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO, USA) was added to the medium on the third day of in vitro culture. The imaged fusion products were placed in 12-mm transwell inserts (Costar Corporation, Cambridge, MA, USA), hanging on the rims of 12-well dishes containing 1 mL of a microspore suspension from the winter barley cultivar “Igri”. The cultured cells were immobilized on a thin alginate layer.

5. Conclusions

Taken together, our experimental results suggest that the strategy of the wheat female gamete for altering its cytoplasmic calcium level relies on an intrinsically more stable mechanism of calcium homeostasis (calcium storage performed by the ER, instead of relying exclusively on calcium influx through the plasma membrane). Furthermore, the repetitive [Ca2+]cyt elevations in the mature angiosperm female gamete activated by the sperm cell appears to be comparable to the dynamics of [Ca2+]cyt oscillations triggered by an oscillation-inducing sperm protein (“oscillogen”) demonstrated to induce a characteristic series of Ca2+ oscillations in the mammalian egg at fertilization [57]. It seems that certain Ca2+ signatures identified in widely differing systems transcend the specific system that they are found in [58]. For instance, some fertilization-related Ca2+ wave signatures appear conspicuously similar [58]. Calcium fluctuations were also reported in tobacco central cells [59]. The findings presented here supply evidence that the spatial and temporal changes in [Ca2+]cyt may represent the initial steps in egg cell activation during fertilization in higher plants (for a review, see [60]).

Our observations may have ramifications for enhancing our understanding of the mechanisms of double fertilization in angiosperms with particular regard to the presumable interaction between the synergids and the egg cell during pollen tube penetration and discharge [61].

Acknowledgments

The financial support of the European Commission Research Directorates General under the arrangement of the Marie Curie Individual Fellowship Programme (Contract Number QLK5-CT-2002-51591) is herewith acknowledged. The authors wish to thank Vipen K. Sawhney, University of Saskatchewan (Saskatoon, SK, Canada) and Bernd Friebe, Kansas State University (Manhattan, KS, USA), for their very constructive suggestions on the manuscript.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary materials can be found at http://www.mdpi.com/1422-0067/15/12/23766/s1.

Author Contributions

Zsolt Pónya, Beáta Barnabás and Mauro Cresti defined the research theme. Zsolt Pónya and Ilaria Corsi designed methods and implemented the experiments. Zsolt Pónya, Richárd Hoffmann, Melinda Kovács, Anikó Dobosy and Attila Zoltán Kovács analyzed and discussed the data, interpreted the findings and wrote the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Steinhardt R., Zucker R., Schatten G. Intracellular calcium release at fertilization in the sea urchin egg. Dev. Biol. 1977;58:185–196. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(77)90084-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steinhardt R., Zucker R., Schatten G. Intracellular calcium release at fertilization in the ascidian egg. Dev. Biol. 1977;135:182–190. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(77)90084-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Speksnijder J.E., Corson D.W., Sardet C. Free calcium pulses following fertilization in the ascidian egg. Dev. Biol. 1989;135:182–190. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(89)90168-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Whitaker M.J., Patel R. Calcium and cell cycle control. Development. 1990;108:525–542. doi: 10.1242/dev.108.4.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kline D., Kline J.T. Repetitive calcium transients and the role of calcium in exocytosis and cell cycle activation in the mouse egg. Dev. Biol. 1992;149:80–89. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(92)90265-I. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stricker S.A. Comparative biology of calcium signaling during fertilization and egg activation in animals. Dev. Biol. 1999;211:157–176. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1999.9340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Whitaker M.J., Steinhardt R.A. Ionic regulation of egg activation. Q. Rev. Biophys. 1982;15:593–666. doi: 10.1017/S0033583500003760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jaffe L.F. Sources of calcium in egg activation: A review and hypothesis. Dev. Biol. 1983;99:265–276. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(83)90276-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nucitelli R. How do sperm activate eggs? Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 1991;25:1–16. doi: 10.1016/s0070-2153(08)60409-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Swann K., Ozil J.P. Dynamics of the calcium signal that triggers mammalian egg activation. Int. Rev. Cytol. 1994;152:183–222. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)62557-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eisen A., Reynolds G.T. Source and sinks for the calcium released during fertilization of single sea urchin eggs. J. Cell Biol. 1985;127:641–652. doi: 10.1083/jcb.100.5.1522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jaffe L.F. The role of calcium explosions, waves, and pulses in activating eggs. In: Metz C.B., Monroy A., editors. Biology of Fertilization. Volume 3. Academic Press; Orlando, FL, USA: 1985. pp. 12–165. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miyazaki S. Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate-induced calcium release and guanine nucleotide-binding protein-mediated periodic calcium rises in golden hamster eggs. J. Cell Biol. 1988;106:345–353. doi: 10.1083/jcb.106.2.345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chiba K., Kado R.T., Jaffe L.A. Development of calcium release mechanisms during starfish oocyte maturation. Dev. Biol. 1990;140:300–306. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(90)90080-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fujiwara T., Nakada K., Shirakawa H., Miyazaki S. Development of inositol trisphosphate-induced calcium release mechanism during maturation of hamster oocytes. Dev. Biol. 1993;156:69–79. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1993.1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mehlmann L.M., Kline D. Regulation of intracellular calcium in the mouse egg: Calcium release in response to sperm or inositol trisphosphate is enhanced after meiotic maturation. Biol. Reprod. 1994;51:1088–1098. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod51.6.1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Swann K., Whitaker M. The part played by inositol triphosphate and calcium in the propagation of the fertilization wave in sea urchin eggs. J. Cell Biol. 1986;103:2333–2342. doi: 10.1083/jcb.103.6.2333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stricker S.A., Centonze V.E., Paddock S.W., Schatten G. Confocal microscopy of fertilization-induced calcium dynamics in sea urchin eggs. Dev. Biol. 1992;149:370–380. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(92)90292-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gillot I., Whitaker M. Imaging calcium waves in eggs and embryos. J. Exp. Biol. 1993;184:213–219. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mohri T., Ivonnet P.I., Chambers E.L. Effect on sperm-induced activation current and increase of cytosolic Ca2+ by agents that modify the mobilization of [Ca2+]i I. Heparin and pentosan polysulfate. Dev. Biol. 1995;172:139–157. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1995.0011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shen S.S. Mechanisms of calcium regulation in sea urchin eggs and their activities during fertilization. Curr. Top. Dev. Biol. 1995;30:63–101. doi: 10.1016/s0070-2153(08)60564-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Whitaker M., Swann K. Lighting the fuse at fertilization. Development. 1993;117:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Antoine A.F., Dumas C., Faure J.E., Feijò J.A., Rougier M. Egg activation in flowering plants. Sex. Plan. Reprod. 2001;14:21–26. doi: 10.1007/s004970100088. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Russell S.D. Double fertilization. Int. Rev. Cytol. 1992;140:357–388. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kranz E., Dresselhaus T. In vitro fertilization with isolated higher plant gametes. Trends Plant Sci. 1996;1:82–89. doi: 10.1016/S1360-1385(96)80039-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Digonnet C., Aldon D., Leduc N., Dumas C., Rougier M. First evidence of a calcium transient in flowering plants at fertilization. Development. 1997;124:2867–2874. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.15.2867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Okamoto T., Higuchi K., Shinkawa T., Isobe T., Lörz H., Koshiba T., Kranz E. Identification of major proteins in maize egg cells. Plant Cell Physiol. 2004;10:1406–1412. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pch161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roberts S.K., Gillot I., Brownlee C. Cytoplasmic calcium and Fucus egg activation. Development. 1994;120:155–163. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Roberts S.K., Brownlee C. Calcium influx, fertilization potential and egg activation in Fucus serratus. Zygote. 1995;3:191–197. doi: 10.1017/S0967199400002586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Antoine A.F., Faure J.E., Cordeiro S., Dumas C., Rougier M., Feijò J.A. A calcium influx is triggered and propagates in the zygote as a wave front during in vitro fertilization of flowering plants. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2000;97:10643–10648. doi: 10.1073/pnas.180243697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weterings K., Russell S.D. Experimental analysis of the fertilization process. Plant Cell. 2004;16:S107–S118. doi: 10.1105/tpc.016873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pónya Z., Pv Fehér F., Av Mitykó J., Dudits D., Barnabás B. Optimisation of introducing foreign genes into egg cells and zygotes of wheat (Tritium aestivum L.) via microinjection. Protoplasma. 1999;208:163–172. doi: 10.1007/BF01279087. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kranz E., Bautor J., Lörz H. In vitro fertilization of single, isolated gametes of maize mediated by electrofusion. Sex. Plant Reprod. 1991;4:12–16. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kranz E., Lörz H. In vitro fertilization of maize by single egg and sperm cell protoplast fusion mediated by high calcium and high pH. Zygote. 1994;2:125–128. doi: 10.1017/S0967199400001878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pónya Z., Tímár I., Szabó L., Kristóf Z., Barnabás B. Morphological characterisation of wheat (T. aestivum L.) egg cell protoplasts isolated from immature and overaged caryopses. Sex. Plant Reprod. 1999;11:357–359. doi: 10.1007/s004970050164. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pónya Z., Kristòf Z., Ciampolin F., Faleri C., Cresti M. Structural change in the endoplasmic reticulum during the in situ development and in vitro fertilization of wheat egg cells. Sex. Plant Reprod. 2004;17:177–188. doi: 10.1007/s00497-004-0226-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Thastrup O., Cullen P.J., Bjørn K., Hanley M.R., Dawson A.P. Thapsigargin, a tumor promoter, discharges intracellular Ca2+ stores by specific inhibition of the endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1990;87:2466–2470. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.7.2466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sagara Y., Inesi G. Inhibition of the sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ transport ATPase by thapsigargin at subnanomolar concentrations. J. Biol. Chem. 1991;266:13503–13506. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Grynkiewicz G., Poenie M., Tsien R.Y. A new generation of calcium indicators with greatly improved fluorescence properties. J. Biol. Chem. 1985;260:3440–3450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vissenberg K., Feijó J.A., Weisenseel M.H., Verbelen J.P. Ion fluxes, auxin and the induction of elongation growth in Nicotiana tabacum cells. J. Exp. Bot. 2001;52:2161–2167. doi: 10.1093/jexbot/52.364.2161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Antoine A.F., Faure J.E., Dumas C., Feijó J.A. Differential contribution of cytoplasmic Ca2+ and Ca2+ influx to gamete fusion and egg activation in maize. Nat. Cell Biol. 2001;3:1120–1123. doi: 10.1038/ncb1201-1120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Treiman M., Caspersen C., Christensen S.B. A tool coming of age: thapsigargin as an inhibitor of sarco-endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPases. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 1998;19:131–135. doi: 10.1016/S0165-6147(98)01184-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thomson L.J., Hall J.L., Williams L.E. A study of the effect of inhibitors of the animal sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum-type calcium pumps on the primary Ca2+-ATPase of red beet. Plant Physiol. 1994;104:1295–1300. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.4.1295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhao J., Yu F.L., Lianf S.P., Zhou C., Yang H.Y. Changes of calcium distribution in egg cells, zygotes and two-celled proembryos of rice (Oryza sativa L.) Sex. Plant Reprod. 2002;14:331–337. doi: 10.1007/s00497-002-0127-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mòl R., Matthys-Rochon E., Dumas C. The kinetics of cytological events during double fertilization in Zea mays L. Plant J. 1994;5:197–206. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.1994.05020197.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Meyer T., Stryer I. Molecular model for receptor-stimulated calcium spiking. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1988;85:5051–5055. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.14.5051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Parker I., Ivorra I. Inhibition by Ca2+ of inositol trisphosphate-mediated Ca2+ liberation: A possible mechanism of oscillatory release of [Ca2+]i. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA. 1990;87:160–264. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.1.260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Faure J.E., Digonnet C., Dumas C. An in vitro system for adhesion and fusion of maize gametes. Science. 1994;263:598–1600. doi: 10.1126/science.263.5153.1598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jackson T.R., Patterson S.I., Thastrup O., Hanley M.R. A novel tumour promoter, thapsigargin, transiently increases cytoplasmic free Ca2+ without generation of inositol phosphates in NG115-401L neuronal cells. Biochem. J. 1988;253:81–86. doi: 10.1042/bj2530081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gouy H., Cefai D., Christensen S.B., Debré P., Bismuth G. Ca2+ influx in human T lymphocytes is induced independently of inositol phosphate production by mobilization of intracellular Ca2+ stores. A study with the Ca2+ endoplasmic reticulum-ATPase inhibitor thapsigargin. Eur. J. Immunol. 1990;20:2269–2275. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830201016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wictome L.E., Henderson I., Lee A.G., East J.M. Mechanisms of inhibition of the calcium pump of sarcoplasmic reticulum by thapsigargin. Biochem. J. 1992;283:525–529. doi: 10.1042/bj2830525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ordenes V.R., Reyes C., Wolff D., Orellana A. A thapsigargin-sensitive Ca2+ pump is present in the pea Golgi apparatus membrane. Plant Physiol. 2002;129:1820–1828. doi: 10.1104/pp.002055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chaubal R., Reger B.J. The dynamics of calcium distribution in the synergid cells of wheat after pollination. Sex. Plant Reprod. 1992;5:206–213. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Heslop-Harrison J., Heslop-Harrison Y. Evaluation of pollen viability by enzymatically induced fluorescence; intracellular hydrolysis of fluorescein diacetate. Stain Technol. 1970;45:115–120. doi: 10.3109/10520297009085351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Poenie M. Alteration of intracellular fura-2 fluorescence by viscosity: A simple correction. Cell Calcium. 1990;11:85–91. doi: 10.1016/0143-4160(90)90062-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kao K.N., Michayluk M.R. Nutritional requirements for growth of Vicia hajastana cells and protoplasts at a very low population density in liquid media. Planta. 1975;126:105–110. doi: 10.1007/BF00380613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Parrington J., Swann K., Shevchenko V.I., Sesay A.K., Lai F.A. Calcium oscillations in mammalian eggs triggered by a soluble sperm protein. Nature. 1996;379:354–368. doi: 10.1038/379364a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rudd J.J., Franklin-Tong V.E. Unravelling response-specificity in Ca2+ signalling pathways in plant cells. New Phytol. 2001;151:7–33. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-8137.2001.00173.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Peng X.B., Sun M.X., Yang H.Y. Comparative detection of calcium fluctuations in single female sex cells of tobacco to distinguish calcium signals triggered by in vitro fertilization. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2009;51:782–791. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2009.00857.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ge L.L., Tian H.Q., Russell S.D. Calcium function and distribution during fertilization in angiosperms. Am. J. Bot. 2007;94:1046–1060. doi: 10.3732/ajb.94.6.1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hamamura Y., Nishimaki M., Takeuchi H., Geitmann A., Kurihara D., Higashiyama T. Live imaging of calcium spikes during double fertilization in Arabidopsis. Nat. Commun. 2014;5:1–9. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]