Introduction

In all cells, the topological problems associated with DNA replication, transcription and repair are managed by a class of enzymes known as DNA topoisomerases1. Many bacteria retain a unique topoisomerase, DNA gyrase, which maintains genomes in a negatively-supercoiled state using an ATP-dependent DNA duplex strand passage mechanism2. A key intermediate in gyrase’s catalytic cycle is the formation of an enzyme-mediated, double-stranded break in which a tyrosine resident in each of the two GyrA subunits of the heterotetrameric enzyme becomes covalently attached to the DNA3. This “cleavage complex” is potentially cytotoxic and is stabilized by the action of clinically-used antibiotics such as the fluoroquinolones4.

Despite their clinical success, fluoroquinolone efficacy is being eroded by increasing levels of antibiotic resistance. In 2007, there were an estimated 9.2 million new Mycobacterium tuberculosis infections, 4.9% of which were caused by multidrug-resistant strains5. The challenge of designing new antibiotics to combat rising resistance can be assisted by high-resolution structures of antibiotic targets; to this end, we have solved the crystal structure of the 59kDa M. tuberculosis DNA gyrase GyrA N-terminal domain (MtGyrA59), the principal drug-binding region of the enzyme. A comparative structural analysis of the M. tuberculosis and E. coli GyrA N-terminal domains reveals previously unobserved structural flexibility in a key hotspot for fluoroquinolone resistance.

Materials and Methods

Protein Purification

The coding region for residues 34–500 of M. tuberculosis GyrA (corresponding to residues 27–525 of the homologous E. coli subunit) was amplified from genomic DNA (American Type Culture Collection) and cloned into a derivative of pET28b with an N-terminal, tobacco etch virus (TEV) protease-cleavable hexahistadine tag. Protein was overexpressed in E. coli BL21-CodonPlus(DE3)-RIL cells (Stratagene) by inducing log-phase cells with 0.25 mM isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside for 14 h at 25°C. Cells were harvested by centrifugation, resuspended in 20 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 800 mM NaCl, 30 mM imidazole, 10% glycerol with protease inhibitors, and frozen dropwise into liquid nitrogen.

For purification, cells were sonicated and centrifuged, and the clarified lysate was passed over a Ni2+ affinity column (Amersham Biosciences). His-tagged protein was eluted with 20 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 400 mM NaCl, 500 mM imidazole and 10% glycerol, then concentrated and exchanged into the same buffer containing 30mM imidazole, followed by incubation overnight at 4° C with hexahistidine-tagged TEV protease6. This mixture was passed over a Ni2+ affinity column, and the flow-through was collected, concentrated and run over an S-200 gel filtration column (Amersham Biosciences) in 50 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 500 mM KCl, 10% glycerol, and 2 mM 2-mercaptoethanol. Peak fractions were pooled and concentrated by ultrafiltration (Millipore Centriprep-10).

Crystallization

Purified MtGyrA59 at 11 mg/ml was dialyzed overnight at 4° C against 10 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 50mM KCl, and 1mM Tris(2-carboxyethyl)-phosphine. Crystals were grown in hanging drop format by mixing 1 μl of protein with 1 μl well of solution containing 26% 2-methyl-2,4-pentanediol, 100 mM Tris pH 9.0, and 1 mM Ciprofloxacin. Crystal reproducibility was extremely erratic, and crystal formation proved not to be drug dependent. For harvesting, crystals were transferred to a cryoprotectant solution containing well solution plus 25% glycerol for 1 minute, followed by looping and flash-freezing in liquid nitrogen.

X-ray diffraction data collection and structure determination

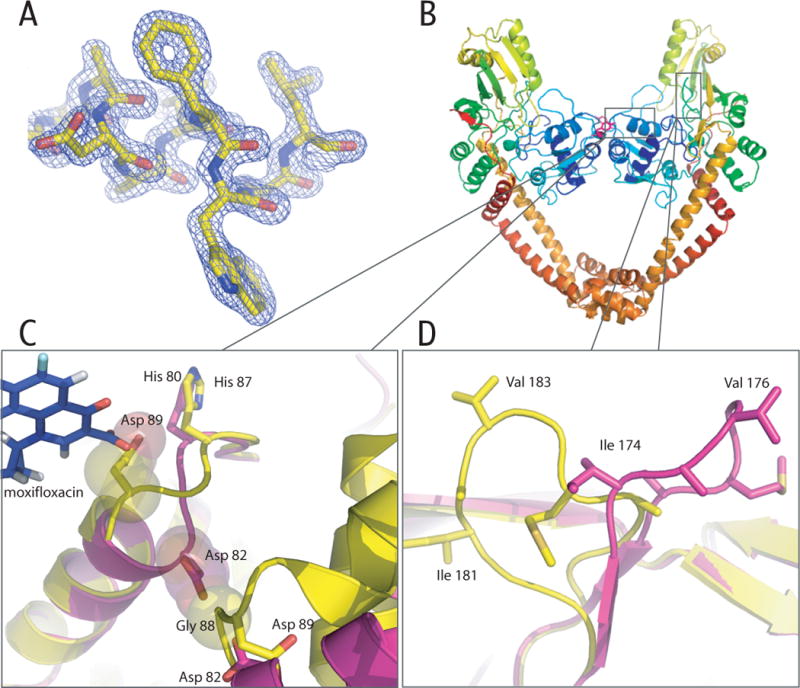

A single native dataset was collected at Beamline 8.3.1 at the Advanced Light Source at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory7. Data were indexed and reduced as P1 using HKL20008. Phasing by molecular replacement with a poly-serine model of the E. coli GyrA NTD (residues 2–523, PDB 1AB4) with PHASER9,10 revealed two MtGyrA59 protomers per asymmetric unit. Density modification and initial building were performed by PHENIX11; subsequent cycles of manual rebuilding and refinement were performed using COOT12. TLS parameters were analyzed with the TLSMD server and six TLS groups were introduced in the last stages of refinement13. The structure consists of residues 2–467(chain A) and 4–467(chain B) of MtGyrA. The final model (Figure 1A) was refined to 1.60 Å resolution, with a final Rwork/Rfree of 17.8/20.1%. Molprobity14 analysis showed a total of 98.4% of residues in the most favored regions of Ramachandran space, with none in disallowed regions. (Table I). The atomic structure and coordinate files have been deposited with the PDB, ID code 3ILW.

Figure 1.

MtGyr59 structure. A) Representative electron density from a refined 2Fo-Fc map contoured at 2σ. B) Cartoon representation (Pymol18) of the MtGyr59 dimer. The active site Tyrosine (Tyr129) is highlighted pink. C) Structural alignments of the MtGyr59 (yellow) and EcGyrA59 (fuchsia) helix α4 region. Gly88 and Asp82 are shown as space filling spheres to highlight the clashes that would occur if MtGyr59 region adopted the same structure as seen in EcGyrA599. Asp89 of MtGyrA59 is also shown, together with moxifloxacin superposed from the S. pneumoniae topo IV co-crystal structure15, to highlight how the MtGyr59 loop would clash with bound drug. D) Overlay of the DNA bending loop region between MtGyr59 (yellow) and EcGyrA59 (fuchsia).

Table I.

Data Collection and Refinement Statistics

| Data Collection | |

| Beamline | ALS 8.3.1 |

| Wavelength (Å) | 1.1 |

| Space Group | P1 |

| Cell Dimension (Å) a, b, c | 61.23, 70.05, 97.81 |

| α, β, γ (°) | 109.96, 91.16, 114.16 |

| Resolution (Å) | 50.00-1.60 |

| Rmerge (%)a | 5.7 (47.8)b |

| I/σ (I) | 20.6 (1.95) |

| Redundancy | 3.6 (2.8) |

| Completeness (%) | 99.0 (43.5) |

| Unique Reflectionsc | 152754 |

| Refinement | |

| Rwork (%)d | 17.8 |

| Rfree (%)e | 20.1 |

| No. atoms | |

| Protein | 7265 |

| Water | 406 |

| Glycerol Molecules | 7 |

| B factor (Å2) | |

| Protein | 28.18 |

| Water | 34.89 |

| RMSD | |

| Bond lengths (Å) | 0.017 |

| Bond Angles (°) | 1.562 |

| Ramachandran (%)f | |

| Favored regions | 98.4 |

| Allowed regions | 1.6 |

| Outliers | 0 |

, where Ii(hkl) is the intensity of an observation and <I(hkl)> is the mean value for its unique reflection. Summations cover all reflections.

The values in parentheses indicate the highest resolution shell.

Nobs/Nunique.

Rfree was calculated same way as Rwork, but with the reflections excluded from refinement. The Rfree set was chosen using default parameters in PHENIX11.

Categories were defined by Molprobity.

Results and Discussion

At 1.6 Å, the MtGyrA59 structure determined here is the highest resolution yet obtained for a type II topoisomerase domain. MtGyrA59 assembles into a heart-shaped dimer (Figure 1B), with an overall fold that closely resembles the structure of the homologous E. coli GyrA NTD (44% sequence identity, 1.27 Å rmsd). One notable difference between the two proteins is in the loop connecting helices α3 and α4 (Gly88-Ala92), a region prone to acquiring quinolone-resistance mutations. The position of this loop in MtGyrA59 deviates significantly from its location in E. coli GyrA NTD9, and in the quinolone- and DNA- bound structure of the homologous region of S. pneumoniae topoisomerase IV15, likely due to crystal-packing influences (Figure 1C). Superposition of MtGyrA59 on the topo IV fluoroquinolone-DNA structure reveals that the position of Asp89 in MtGyrA59 is likely to clash with moxifloxacin as bound by S. pneumoniae topo IV. The novel loop conformation is present in both subunits in the asymmetric unit, suggesting that this region is more conformationally dynamic than previously suspected, at least in MtGyrA.

MtGyrA59 and the E. coli GyrA NTD also differ significantly in the loop encompassing Ile181 (Ile174 in E. coli) (Figure 1D), a region that has been shown to bend DNA in S. cerevisiae topoisomerase II16. Interestingly, conformational diversity has been observed in other regions that interact with DNA. The loop bearing the active site tyrosine differs significantly between E. coli GyrA (residues 129–131) and the paralogous subunit of topoisomerase IV9,17. These examples demonstrate that the critical DNA-engaging regions of the GyrA NTD are structurally malleable, a property that may ultimately play an important role in modulating inhibitor potency. Studies of MtGyrA and other type II topoisomerase homologs bound to drug and DNA substrates will be needed to address this issue in the future.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the NIH (PO1 AI68135 and RO1 CA077373).

References

- 1.Schoeffler AJ, Berger JM. DNA topoisomerases: harnessing and constraining energy to govern chromosome topology. Q Rev Biophys. 2008;41(1):41–101. doi: 10.1017/S003358350800468X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mizuuchi K, Fisher LM, O’Dea MH, Gellert M. DNA gyrase action involves the introduction of transient double-strand breaks into DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1980;77(4):1847–1851. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.4.1847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tse YC, Kirkegaard K, Wang JC. Covalent bonds between protein and DNA. Formation of phosphotyrosine linkage between certain DNA topoisomerases and DNA. J Biol Chem. 1980;255(12):5560–5565. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hooper DC. Mechanisms of fluoroquinolone resistance. Drug Resist Updat. 1999;2(1):38–55. doi: 10.1054/drup.1998.0068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Organization WH. Global tuberculosis control – epidemiology, strategy, financing. WHO report 2009. 2008 WHO/HTM/TB/2009.411. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kapust RB, Tozser J, Fox JD, Anderson DE, Cherry S, Copeland TD, Waugh DS. Tobacco etch virus protease: mechanism of autolysis and rational design of stable mutants with wild-type catalytic proficiency. Protein Eng. 2001;14(12):993–1000. doi: 10.1093/protein/14.12.993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.MacDowell AA, Celestre RS, Howells M, McKinney W, Krupnick J, Cambie D, Domning EE, Duarte RM, Kelez N, Plate DW, Cork CW, Earnest TN, Dickert J, Meigs G, Ralston C, Holton JM, Alber T, Berger JM, Agard DA, Padmore HA. Suite of three protein crystallography beamlines with single superconducting bend magnet as the source. J Synchrotron Radiat. 2004;11(Pt 6):447–455. doi: 10.1107/S0909049504024835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Otwinowski Z, M W. Processing of X-ray diffraction data collected in the oscillation mode. Methods in Enzymology. 1997;276:307–326. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(97)76066-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cabral JHM, Jackson AP, Smith CV, Shikotra N, Maxwell A, Liddington RC. Crystal structure of the breakage-reunion domain of DNA gyrase. 1997;388(6645):903. doi: 10.1038/42294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McCoy AJ, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Adams PD, Winn MD, Storoni LC, Read RJ. Phaser crystallographic software. 2007;40(4):658. doi: 10.1107/S0021889807021206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Adams PD, Grosse-Kunstleve RW, Hung L-W, Ioerger TR, McCoy AJ, Moriarty NW, Read RJ, Sacchettini JC, Sauter NK, Terwilliger TC. PHENIX: building new software for automated crystallographic structure determination. 2002;58(11):1948. doi: 10.1107/s0907444902016657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Emsley P, Cowtan K. Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. 2004;60(12):2126. doi: 10.1107/S0907444904019158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Painter J, Merritt EA. TLSMD web server for the generation of multi-group TLS models. 2006;39(1):109. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lovell Simon C, D IW, Arendall W Bryan, III, de Bakker Paul I W, Word J Michael, Prisant Michael G, Richardson Jane S, Richardson David C. Structure validation by Calpha geometry: &phis;,psi and Cbeta deviation. Proteins: Structure, Function, and Genetics. 2003;50(3):437–450. doi: 10.1002/prot.10286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Laponogov I, Sohi MK, Veselkov DA, Pan XS, Sawhney R, Thompson AW, McAuley KE, Fisher LM, Sanderson MR. Structural insight into the quinolone-DNA cleavage complex of type IIA topoisomerases. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009 doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dong KC, Berger JM. Structural basis for gate-DNA recognition and bending by type IIA topoisomerases. Nature. 2007;450(7173):1201–1205. doi: 10.1038/nature06396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Corbett KD, Schoeffler AJ, Thomsen ND, Berger JM. The structural basis for substrate specificity in DNA topoisomerase IV. J Mol Biol. 2005;351(3):545–561. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.DeLano WL. The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System. DeLano Scientific; Palo Alto, CA, USA: 2002. [Google Scholar]