Abstract

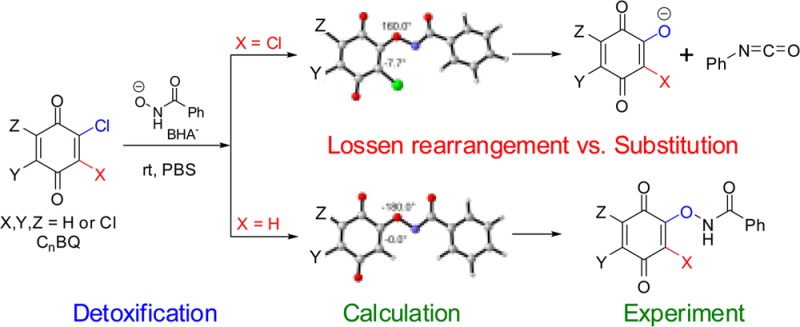

The classic Lossen rearrangement is a well-known reaction describing the transformation of an O-activated hydroxamic acid into the corresponding isocyanate. In this study, we found that chlorinated benzoquinones (CnBQ) serve as a new class of agents for the activation of benzohydroxamic acid (BHA), leading to Lossen rearrangement. Compared to the classic one, this new kind of CnBQ-activated Lossen rearrangement has the following unique characteristics: (1) The stability of CnBQ-activated BHA intermediates was found to depend not only on the degree but also on the position of Cl-substitution on CnBQs, which can be divided into two subgroups. (2) It is the relative energy of the anionic CnBQ–BHA intermediates that determine the rate of this CnBQ-activated rearrangement, which is the rate-limiting step, and the Cl or H ortho to the reaction site at CnBQ is crucial for the stability of the anionic intermediates. (3) A pKa–activation energy correlation was observed, which can explain why the correlation exists between the rate of the rearrangement and the acidity of the conjugate acid of the anionic leaving group, the hydroxlated quinones. These findings may have broad implications for future research on halogenated quinoid carcinogens and hydroxamate biomedical agents.

Introduction

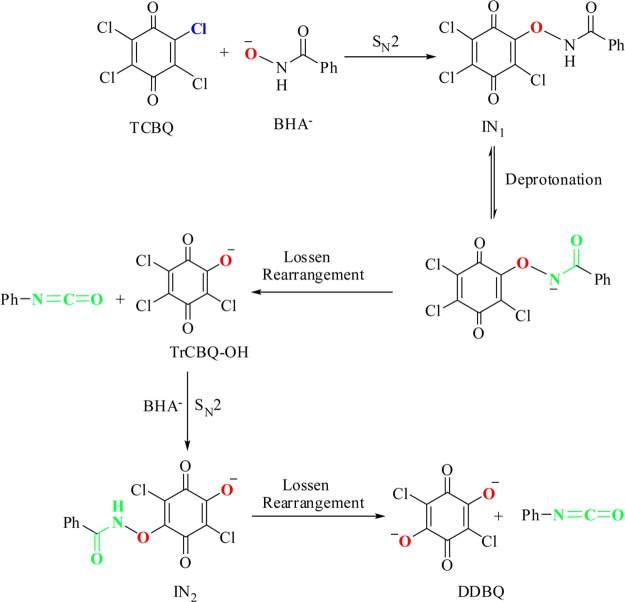

The Lossen rearrangement, which was first reported by Lossen in 1872, is a thermal or alkaline conversion of hydroxamic acid into isocyanate via the intermediacy of its O-activated (such as O-acyl, -sulfonyl, or -phosphoryl) derivative.1−8 It has been established that the O-activation of hydroxamic acids is essential for Lossen rearrangement to take place.1−4 Recently, we found that benzohydroxamic acid (BHA) was able to dechlorinate tetrachloro-1,4-benzoquinone (TCBQ) via an unusually mild and facile Lossen rearrangement mechanism (Scheme 1).9 In that study, TCBQ and other tetrahalogenated quinones were found to serve as a unique class of activating agents for in situ activation of free hydroxamic acids. Compared with the classic Lossen rearrangement reactions, this novel variation of the Lossen rearrangement reaction took place at room temperature and under neutral or even weakly acidic pH and is responsible for the detoxification of the carcinogenic tetrahalogenated quinones. However, some key issues of the chloroquinone-activated Lossen rearrangement mechanism remained unclear. First, in that study, neither TCBQ O-activated BHA intermediates (e.g., IN1 in Scheme 1) nor the initial transient rearrangement product of BHA, phenyl isocyanate (Ph-NCO), was directly isolated and identified due to their extreme instability. Second, it was not clear whether this kind of Lossen rearrangement reaction is a general mechanism for enhancing dechlorination of all chlorinated benzoquinones. Third, it was unclear what the major difference of the halogenated quinone-activated Lossen rearrangement is as compared to the classic one.

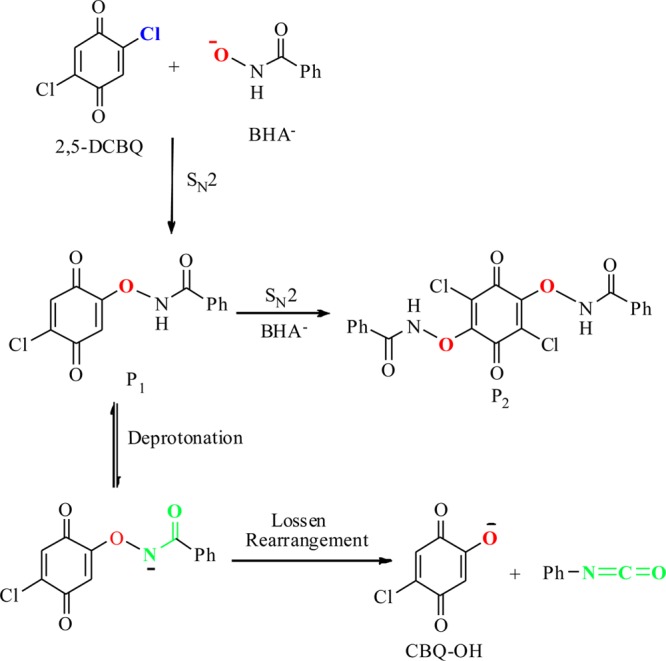

Scheme 1. Proposed Mechanism for the Dramatic Acceleration of TCBQ Hydrolysis by BHA: Suicidal Nucleophilic Attack Coupled with an Unusual Double Lossen Rearrangement9.

Therefore, in the present study, we tried to address the following questions: (i) Is it possible to get the more stable O-chloroquinonated BHA intermediates which are then unequivocally characterized when TCBQ is substituted with other less chlorinated quinones, and if so, (ii) do these intermediates decompose via the same Lossen rearrangement, and if so, under what experimental conditions? (iii) What is unique for the halogenated quinone-mediated Lossen rearrangement as compared to the classic one? (iv) Is there a correlation between the pKa values of the corresponding conjugate acids of the leaving groups, the hydroxylated choroquinones (Cn–1BQ-OH, n = 1–4), and the stability of the O-chloroquinonated BHA intermediates, and what is the underlying reason? (v) What is the potential biological and environmental relevance of this novel halogenated quinone-activated Lossen rearrangement? To answer the above questions, in this study, a combined experimental and theoretical investigation was conducted to systematically examine the reactions of all seven homologous series of chlorinated 1,4-benzoquinones (CnBQ, n = 1–4) with BHA.

Results and Discussion

Just as described in our previous study,9 the proposed TCBQ O-activated BHA intermediate, IN1, was unable to be isolated and identified. The instability is possibly due to the unusually rapid and facile decomposition via Lossen rearrangement to 2,3,5-trichloro-6-hydroxy-1,4-benzoquinone (TrCBQ-OH) and Ph-NCO. For the classic Lossen rearrangement reactions activated by the acyl, sulfonyl, or phosphoryl group, it has been found that the rearrangement rate is directly proportional to the acidity of the conjugate acid of the leaving group.1−4 Due to the strong acidity of TrCBQ-OH (pKa: 1.0910) and 2,5-dichloro-3,6-dihydroxy-1,4-benzoquinone (DDBQ, pKa1: 0.5811 or 0.7612), which are the conjugate acids of the leaving anions in that study, it was expected that the rearrangement of the postulated reaction intermediates should be very fast so that the intermediates rearrange rapidly once formed.

If there indeed exists such a correlation between the rearrangement rate and the acidity of the corresponding rearranged products, Cn–1BQ-OH, we would speculate that when TCBQ is replaced with the less chlorinated benzoquinones, for example, 2,5-dichloro-1,4-benzoquinone (2,5-DCBQ), the rearrangement rate of 2,5-DCBQ O-activated BHA derivatives should be much slower because of the weak acidity of 2-chloro-5-hydroxy-1,4-benzoquinone (CBQ-OH, pKa: 3.63, measured in this work) and 2,5-dihydroxy-1,4-benzoquinone (pKa1: 2.95),12 which are the conjugate acids of the leaving group for the reaction of 2,5-DCBQ/BHA, as compared to TrCBQ-OH and DDBQ in TCBQ/BHA. If this is the case, then we might further speculate that if the reaction between 2,5-DCBQ and BHA took place in a way similar to that for TCBQ/BHA, the 2,5-DCBQ O-activated BHA intermediates of 2,5-DCBQ/BHA, the counterparts of IN1 and IN2 (Scheme 1), might be stable enough for direct detection and identification.

Isolation and Identification of the Relatively Stable O-Chloroquinonated BHA Derivatives of 2,5-DCBQ/BHA

The reaction of 2,5-DCBQ with BHA was first studied by quadrupole time-of-flight electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (Q-TOF-ESI-MS). We found that the major ion peak for 2,5-DCBQ/BHA at a molar ratio of 1:1 is at m/z 157 (Figure S1A, Supporting Information (SI)), which was initially assigned to the molecular peak of 2-chloro-5-hydroxy-1,4-benzoquinone (CBQ-OH), the counterpart of TrCBQ-OH (Scheme 1). Subsequent quantitative HPLC analysis, however, revealed that the yield of CBQ-OH was only 2%, and the major ion peak at m/z 157 might be the fragment ion of an unknown product. Special attention was then paid to the weak ion peak at m/z 276, which was neglected at first due to its low abundance (only 5% of the major ion peak) (Figure S1A, SI). Another weak ion peak at m/z 377 was also observed in the MS spectra of 2,5-DCBQ/BHA (1:2) (Figure S1B, SI). On the basis of molecular mass calculations, the weak ion peaks at m/z 276 and m/z 377 should actually correspond to the single- (P1 in Scheme 2) and double-substituted (P2 in Scheme 2) adducts of 2,5-DCBQ with BHA, respectively.

Scheme 2. Proposed Mechanism for 2,5-DCBQ/BHA Reaction.

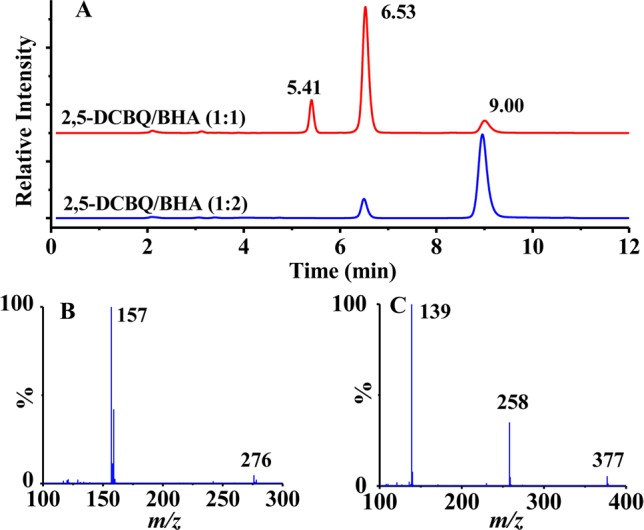

To test whether this assignment is the case, the reaction of 2,5-DCBQ/BHA was then investigated in detail by HPLC/Q-TOF-ESI-MS. It was found that the addition of 2,5-DCBQ to BHA at different molar ratios indeed rapidly led to the formation of the two final products P1 and P2. The major reaction product for 2,5-DCBQ/BHA at a 1:1 ratio is P1 with the retention time of 6.53 min (Figure 1A), which shows the molecular ion [M – H]− at m/z 276 and the fragment ion at m/z 157; both of them are one-chlorine-isotope peak clusters (Figure 1B). The major product for 2,5-DCBQ/BHA at ≤1:2 ratios is P2 with the retention time of 9.00 min (Figure 1A), which has the molecular ion [M – H]− at m/z 377 and the fragment ions at m/z 258 and m/z 139 (Figure 1C). Although the collision energy was lowered to 3.0 V, the abundance of molecular ion peak of P1 or P2 was still much lower than their respective fragment ion peaks, indicating that the two products were readily fragmented even under very mild MS conditions. P1 or P2 was further identified by 1H and 13C NMR as the single- and double-substituted 2,5-DCBQ adducts with BHA, respectively (Figure S2, Figure S3, and Table S1 in Supporting Information).

Figure 1.

Isolation and identification of the relatively stable O-chloroquinonated BHA derivatives of 2,5-DCBQ/BHA. HPLC chromatograms of 2,5-DCBQ/BHA (1:1 or 1:2) in CH3COONH4 buffer (pH 7.4, 0.1 M) at 275 nm (A); MS spectrum of P1 at the retention time of 6.53 min in the HPLC chromatogram (B); MS spectrum of P2 at the retention time of 9.00 min in the HPLC chromatogram (C).

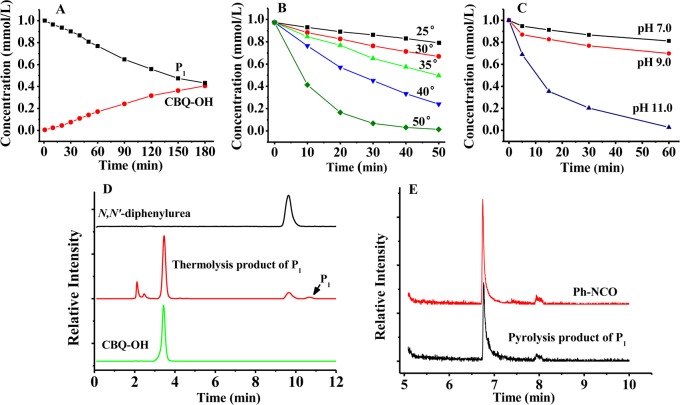

Decomposition of P1 via Lossen Rearrangement at Higher Temperature or Alkaline pH

An interesting question to investigate is whether the stable 2,5-DCBQ O-activated BHA derivative P1 would decompose through the same Lossen rearrangement. We found that aqueous P1 decomposed with a half-life of approximately 2.5 h at room temperature in neutral buffer (pH 7.0) (Figure 2A), which is in contrast to the extremely rapid decomposition of IN1 in the TCBQ/BHA reaction. Interestingly, the slow decomposition of P1 was markedly accelerated by higher temperature or alkaline pH (Figure 2B and 2C), which is consistent with the classic Lossen rearrangement reaction. The experimental activation energy of the rearrangement of P1 was calculated to be 23.46 kcal/mol, according to the measured initial kinetics at 25/30/35/40 °C and the Arrhenius equation. Further, we found that decomposition of P1 in aqueous buffer is just through the same Lossen rearrangement mechanism, because the analysis by TLC and HPLC (Figure 2D) showed that the major decomposition products are aniline, N,N′-diphenylurea, and CBQ-OH, which are typical products of Lossen rearrangement reactions.

Figure 2.

Decomposition of P1 via Lossen rearrangement at higher temperature or alkaline pH. The formation of CBQ-OH was accompanied by the relatively slow decomposition of P1 in neutral solution (A, pH 7.0) at 25 °C. The decomposition of P1 in aqueous buffer was markedly accelerated (B) at higher temperature and (C) under alkaline conditions. (D) HPLC chromatogram of the thermolysis of P1 in buffer solution (pH 8.0) at 60 °C, compared to that of N,N′-diphenylurea and CBQ-OH as references. (E) The GC/MS chromatogram of pyrolysis product phenyl isocyanate of P1, compared to that of authentic phenyl isocyanate.

Unfortunately, we still failed to directly detect and identify the transient Ph-NCO due to its extreme instability in aqueous buffer. So, to detect this initial Lossen rearrangement product, the key evidence for Lossen rearrangement, we performed the decomposition of P1 under nonaqueous conditions (for details on how to detect Ph-NCO via pyrolysis of P1, see Supporting Information). As expected, Ph-NCO was detected by GC/MS with a retention time at 6.75 min (Figure 2E) and a characteristic MS spectra with peaks at m/z 119 (100%), 91 (41%), and 64 (24%), the same as that for authentic Ph-NCO.

Proposed Molecular Mechanism for the Reaction of 2,5-DCBQ/BHA and Comparison with That of TCBQ/BHA

On the basis of the above experimental results, the reaction pathways for 2,5-DCBQ/BHA in aqueous solution was proposed as the following (Scheme 2): a nucleophilic reaction takes place between 2,5-DCBQ and the benzohydroxamate anion (BHA–) (at high 2,5-DCBQ/BHA molar ratios), forming the relatively stable single-substituted P1 (pKa 5.0, measured in this work) at room temperature and under neutral pH. Following loss of a proton from nitrogen to form the anionic intermediate of P1, a slow decomposition undergoes Lossen rearrangement to form CBQ-OH and Ph-NCO. The rearrangement rate is markedly enhanced under alkaline pH or at higher temperatures. Once formed, the rearranged product Ph-NCO rapidly hydrolyzes to form aniline, which then reacts with another Ph-NCO to yield N,N′-diphenylurea. When BHA is in excess, a second nucleophilic reaction between P1 and BHA occurs, forming the double-substituted P2.

Comparative analysis of the reaction mechanisms between TCBQ/BHA and 2,5-DCBQ/BHA indicated that the stability of O-chloroquinonated BHA derivatives seems to determine the reaction pathway. At high molar ratios (≥1), the reaction pathway of 2,5-DCBQ/BHA is the same as that of TCBQ/BHA, entailing a nucleophilic attack and then a Lossen rearrangement. The only difference is that the rearrangement rate of the relatively stable derivative P1 is much slower than that of the transient intermediate IN1 in TCBQ/BHA. Therefore, when BHA is in excess, P1 is trapped by excessive BHA– to give the double-substituted product P2, while IN1 rearranges rapidly into TrCBQ-O– (8, Table S2, SI) and Ph-NCO. Then TrCBQ-O– reacts with excessive BHA– via the second nucleophilic attack coupled with the second Lossen rearrangement to give the final product DDBQ (9, Table S2, SI).

Isolation and Identification of Other O-Chloroquinonated BHA Derivatives

Similar relatively stable 1:1 adducts with BHA were isolated and identified, when 2,5-DCBQ was replaced by its isomer 2,6-DCBQ, which showed the molecular ion peak [M – H]− at m/z 276, and the fragment ion at m/z 157, both of which were one-chlorine-isotope peak clusters (Figure S4A and S4B, SI), but not with another isomer 2,3-DCBQ. Instead, the rearranged product 2-chloro-3-hydroxy-1,4-benzoquinone (2, Table S2, SI) was isolated from 2,3-DCBQ/BHA, which showed the molecular ion peak [M – H]− at m/z 157 (Figure S4A and S4D, SI). Thus, it would be interesting to know why these O-activated BHA derivatives of these DCBQ isomers have different stabilities.

As mentioned above, it was reported that there might be a correlation between the rate of Lossen rearrangement and the acidity of the conjugate acid of the leaving group.1−4 In the current work, the corresponding conjugate acids of the leaving group for the O-activated BHA adducts with three DCBQ isomers (2,5-, 2,6-, and 2,3-DCBQ) (in 1:1 ratio) should be 2-chloro-5-hydroxy- (3, Table S2, SI), 2-chloro-6-hydroxy- (4, Table S2, SI), and 2-chloro-3-hydroxy-1,4-benzoquinone (2, Table S2, SI); their pKa values are found to be 3.63 (expt), 3.65 (calcd), and 2.28 (expt), respectively (Table S2, SI). From these data, we speculated that when the pKa value is ≤2.5, then the O-chloroquinonated BHA derivatives might be unstable and may quickly decompose through Lossen rearrangement to form the corresponding Cn–1BQ-OH and Ph-NCO, but when the pKa value is >2.5, then the O-chloroquinonated BHA derivatives might be stable enough to be isolated and identified.

To test the above hypothesis, we studied the reactions between BHA and two other chlorinated benzoquinones: One is the less chlorinated 2-chloro-1,4-benzoquinone (2-CBQ), and the other is the more chlorinated 2,3,5-trichloro-1,4-benzoquinone (TrCBQ). If the above hypothesis were true, then we would expect that 2-CBQ should be able to form relatively more stable 1:1 adduct with BHA because the pKa of its corresponding 2-hydroxy-1,4-benzoquinone (1, Table S2, SI) is 4.0–4.2.13−15 For TrCBQ, if substituted at the 5-chloro position by BHA, we would expect it should also be able to form a relatively stable 1:1 adduct with BHA because the pKa of its corresponding 2,3-dichloro-5-hydroxy-1,4-benzoquinone (5, Table S2, SI) is 2.89, but if substituted at the 2- or 3-chloro position, then no stable 1:1 TrCBQ–BHA adducts would be isolated because the pKa values of the corresponding Cn–1BQ-OH are 1.88 (2,5-dichloro-3-hydroxy-1,4-benzoquinone, 6, Table S2, SI) and 1.5716 (2,6-dichloro-3-hydroxy-1,4-benzoquinone, 7, Table S2, SI), respectively. We found that this was indeed the case (see Figure S5 in Supporting Information for details on how to isolate and characterize the products of other CnBQ/BHA).

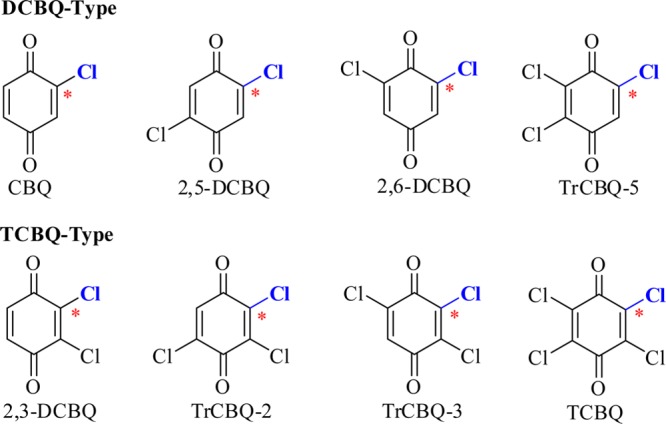

Therefore, we can expect that the stability of the O-chloroquinonated BHA derivatives should follow the general rule that the more acidic the conjugate acids of the leaving groups, the faster the rearrangement rates. This also suggests that although the reactions of CnBQ/BHA (1:1) follow the same pathway, the rearrangement rate of the O-chloroquinonated BHA derivatives are very different. On the basis of the difference between the stability of the O-chloroquinonated BHA derivatives, CnBQs can be classified as two subgroups (Figure 3): TCBQ-type and DCBQ-type. The former, containing 2,3-DCBQ, TrCBQ-2, TrCBQ-3, and TCBQ, reacts with BHA just as for TCBQ/BHA to form the transient CnBQ/BHA (1:1) intermediate, which is unable to be isolated and identified by LC/MS due to its rapid decomposition via rearrangement, while the corresponding CnBQ/BHA (1:1) derivatives of the latter, containing CBQ, 2,5-DCBQ, 2,6-DCBQ, and TrCBQ-5, are stable enough to be isolated and identified under our experimental conditions because of the slow decomposition rate just as for 2,5-DCBQ/BHA.

Figure 3.

CnBQs are classified by the stability of the CnBQ-activated intermediates with BHA (1:1, * reaction site).

DFT Study of the Reaction Mechanism of CnBQ/BHA

Although we performed an extensive experimental study on the reactions of CnBQ/BHA, some questions raised were not yet solved satisfactorily: (i) What is unique for the halogenated quinone-mediated Lossen rearrangement as compared to the classic one? (ii) Why is the stability of the O-chloroquinonated BHA derivatives so different? (iii) Why is there a correlation between the rearrangement rates of the O-chloroquinonated BHA derivatives and the pKa of the rearranged products Cn–1BQ-OHs?

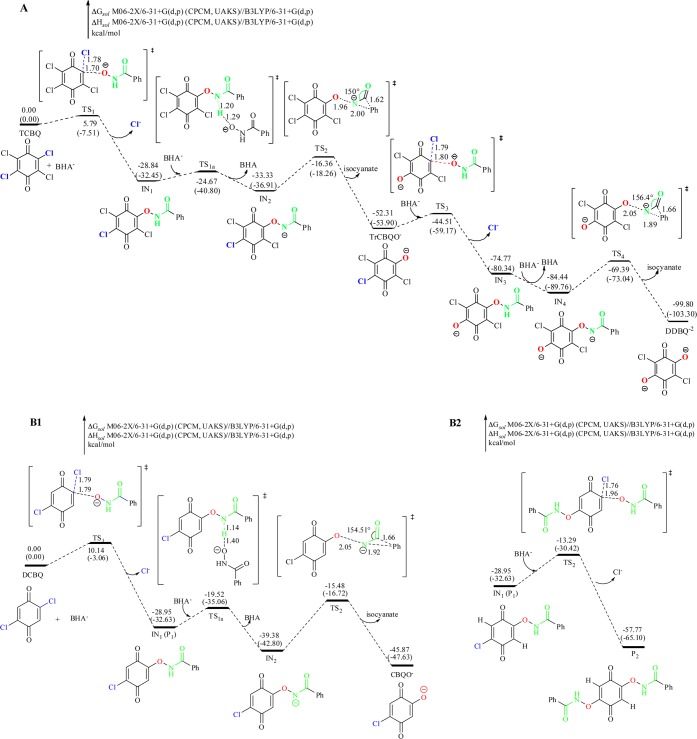

To pursue answers to these questions, we performed a theoretical investigation on the intermediates and energies of the reactions of CnBQ/BHA (1:1). The calculation of the reaction of TCBQ/BHA (Figure 4A) reproduces the experimental results very well. The first step is the nucleophilic attack of BHA– on TCBQ via the transition state (T)-TS1 (T, short for TCBQ) forming the neutral intermediate (T)-IN1 with an energy barrier of 5.79 kcal/mol, and then the second step is deprotonation of N–H of (T)-IN1 forming the anionic intermediate (T)-IN2 with an energy barrier of 4.17 kcal/mol. Subsequent conversion of (T)-IN2 into TrCBQ-O– (via (T)-TS2) requires an activation energy of 16.97 kcal/mol. When BHA is in excess, TrCBQ-O– further reacts with BHA through the second Lossen rearrangement, yielding DDBQ and another molecule of Ph-NCO. From the potential energy surface of the overall reaction pathway, it is easy to find that the first Lossen rearrangement ((T)-IN2 to TrCBQ-O–) is the rate-determining step but can be overcome easily under room temperature. This is consistent with the experimental results that TCBQ reacts with BHA completely at room temperature to form the rearranged products within 1 min.9

Figure 4.

DFT study of the reaction mechanism of CnBQ/BHA. The potential energy surface of the reactions of TCBQ/BHA (A); 2,5-DCBQ/BHA (1:1, B1) and (1:2, B2).

The calculation data of the reaction of 2,5-DCBQ/BHA are also very consistent with the experimental results (Figure 4B). When the reaction molar ratio of 2,5-DCBQ/BHA is 1:1, the activation and deprotonation steps are facile with an activation energy of 10.14 and 9.43 kcal/mol, respectively. The subsequent Lossen rearrangement ((D)-IN2 (D, short for DCBQ) to CBQ-O–) is also the rate-determining step with a calculated activation energy of 23.90 kcal/mol (Figure 4B1), which is in complete agreement with the experimental activation energy of 23.46 kcal/mol and is 6.93 kcal/mol higher than that of the first Lossen rearrangement of TCBQ/BHA. Therefore, compared with (T)-IN2, the anionic 2,5-DCBQ O-activated BHA intermediates (D)-IN2 should not quickly decompose via Lossen rearrangement and can be isolated as substituted adduct P1.

When BHA is in excess, accompanied by the slow rearrangement of (D)-IN2, the second nucleophilic attack of BHA– to form double-substituted product P2 occurs (Figure 4B2), which is facile with an activation energy of 15.66 kcal/mol, 8.24 kcal/mol lower than that of the concurrent Lossen rearrangement step ((D)-IN2 to CBQ-O–). This can explain why the 2,5-DCBQ O-activated BHA intermediates did not prefer Lossen rearrangement (but rather nucleophilic substitution) as (T)-IN2 when BHA is in excess. This is also in good agreement with the experimental results: Quantitative determination by HPLC using the purified authentic P1 and P2 as standard reference showed that the reaction of 2,5-DCBQ/BHA (1:1) led to the formation of 83% P1 and 6% P2 within 1 min, while the reaction of 2,5-DCBQ/BHA (1:2) yielded 78% P2 and 16% P1.

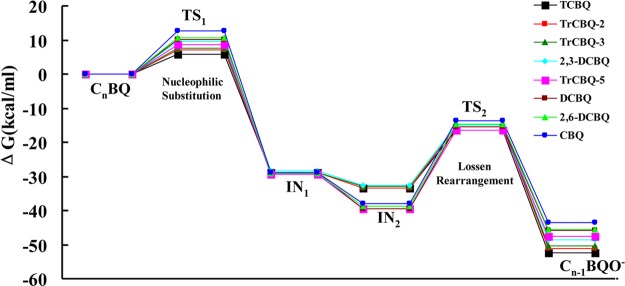

The DFT calculations for other CnBQ/BHA reactions were also performed. The calculation results of the first nucleophilic reaction coupled with Lossen rearrangement when the molar ratio of CnBQ/BHA is 1:1 are summarized in Figure 5 and Table S3 (SI). The reaction of CnBQ/BHA (1:1) entailed a facile nucleophilic attack (CnBQ to IN1 via TS1) with the activation energy of 5–13 kcal/mol and facile deprotonation of N–H to form its corresponding anionic CnBQ-activated BHA intermediate IN2 and a subsequent rate-determining Lossen rearrangement (IN2 to Cn–1BQ-OH via TS2) with the activation energy of 16–25 kcal/mol.

Figure 5.

Potential energy (ΔG) surface of the reactions of CnBQ/BHA (1:1).

Careful examination of the potential energy profiles of the Lossen rearrangement pathway of CnBQ/BHA (1:1) in Figure 5 reveals that the discrepancy of activation energies in the rearrangement step (IN2 to TS2) is mainly due to the relative energies of anionic intermediates IN2 (ΔΔG > 6 kcal/mol), rather than the relative energies of the transition state TS2 (ΔΔG < 1 kcal/mol). Interestingly, it was observed that the relative energies of IN2 fall into two subgroups: IN2 of 2,3-DCBQ, TrCBQ-2, TrCBQ-3, and TCBQ have relative energies lower than that of IN2 of CBQ, 2,5-DCBQ, 2,6-DCBQ, and TrCBQ-5, which is in agreement with our above experimental classification (TCBQ-type and DCBQ-type in Figure 3). From the structures of these two groups of CnBQ, a specific distinction is observed: TCBQ-type have an o-chlorine adjacent to the reaction site while DCBQ-type CnBQs have an o-hydrogen.

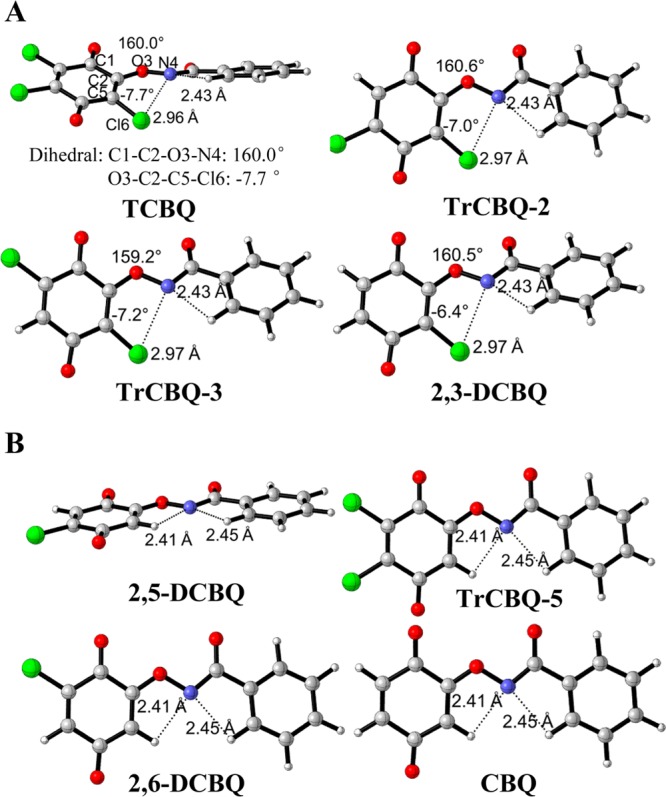

It has been shown that the rate of Lossen rearrangement of hydroxamic acids is related to the electron-withdrawing substituents in R′ of diacyl hydroxylamines (R-C(=O)NH-O-R′) when R and R′ are aryl groups.17−19 Compared with that of the rearrangement activation energy of R-C(=O)NH-O-R′, which showed that when R′ is o-NO2 (or Br, Cl)-C6H4, the activation energy is about 1 kcal/mol less than that when R′ is C6H5 and o-CH3OC6H4;18 however, the discrepancy between the activation energy of DCBQ-type IN2 and TCBQ-type IN2 is relatively large (about 5 kcal/mol). This suggests that the electron-withdrawing effect of the o-chlorine substituent in the quinoid ring might not be the sole feasible factor to influence the rearrangement rate. Therefore, we re-examined in-depth the structures of (T)-IN2 and (D)-IN2 (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Structures of IN2 of TCBQ-type (A) and of DCBQ-type (B).

From the structure of (T)-IN2 (Figure 6A), it was observed that the electrostatic repulsion between the anionic nitrogen and the neighboring chlorine atom made the benzamide twist out 20° from the quinone plane, and the chlorine atom moved about 7.7° from the quinone plane in the opposite direction. The twisted structure of the anionic intermediate (T)-IN2 is unstable, because it breaks the resonance of the quinone and benzamide parts; therefore, it easily undergoes rearrangement. However, (D)-IN2 is a planar molecule (Cs symmetry, Figure 6B) with no electrostatic repulsion, so the conjugation interaction stabilizes the anion intermediate. This kind of stereoelectronic effect is also present in IN2 of all other TCBQ-type or DCBQ-type CnBQ (Figure 6). Thus, this suggests that chlorine or hydrogen at a position ortho to the reaction site might be the pivotal factor to determine the relative energy and then the rearrangement rate, which is the unique feature of these halogenated quinone-mediated Lossen rearrangements.

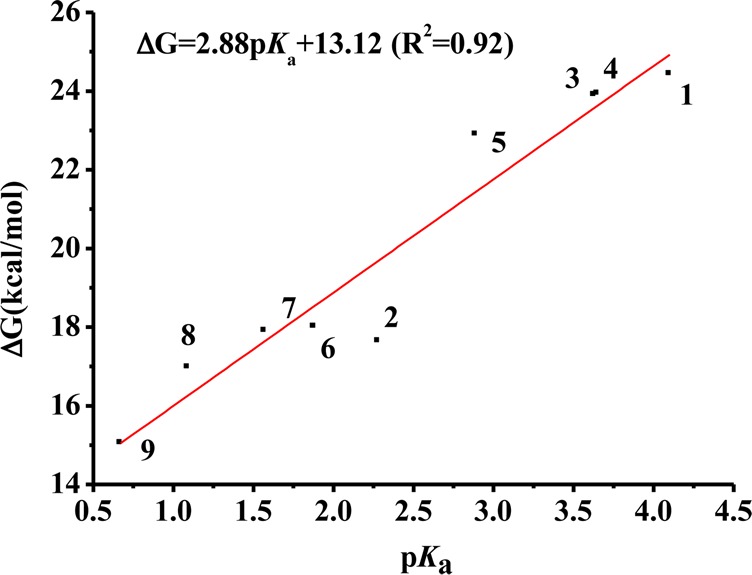

Correlation between the Rate of Lossen Rearrangement and the Acidity of Cn–1BQ-OH

It is obvious that the rate of rearrangement was determined by the stability of the anionic CnBQ O-activated BHA intermediate. Then, why is there the relationship between the Lossen rearrangement rate and the pKa of Cn–1BQ-OH? To answer this question, we calculated the pKa of all Cn–1BQ-OHs (Table S2, SI), and interestingly, we found that the pKa of Cn–1BQ-OH has a good linear relationship with the activation energy for the Lossen rearrangement of CnBQ/BHA (Figure 7). The pKa–activation energy correlation indicates that the pKa of the corresponding Cn–1BQ-OH might also be taken into account in consideration of the “ortho effect”. For DCBQ-type Cn–1BQ-OH, the acidity is only affected by the electron-withdrawing effect of m- or p-chlorine. However, the acidity of TCBQ-type Cn–1BQ-OH is mainly influenced by o-chlorine. It seems reasonable that the o-chlorine effect might be much stronger than m- or p-chlorine.

Figure 7.

pKa–activation energy correlation between the pKa of Cn–1BQ-OH and the activation energy for the Lossen rearrangement of CnBQ/BHA. For the numbering of the hydroxylated benzoquiones, see Table S2, SI. The experimental pKa values were preferred for linear fitting.

Summary

In this study, through a combined experimental and theoretical investigation, we found that all seven isomers of chlorinated benzoquinones (CnBQs) can serve as a new class of agents for the activation of free hydroxamic acids, leading to Lossen rearrangement. Compared to the classic one, this newly discovered CnBQ-activated Lossen rearrangement has the following three unique characteristics: (1) The stability of CnBQ-activated BHA intermediates was found to (i) be dependent not only on the degree but also on the position of chloro-substitution on the quinone structure of CnBQ, which can be divided into two subgroups: TCBQ- and DCBQ-type, and to (ii) follow the general rule in the correlation between the rearrangement rates and the acidity of the rearranged products, the hydroxlated benzoquinones, whose pKa values vary remarkably from 0.6 to 4.2. (2) The deprotonation of N–H to form its anionic CnBQ-activated BHA intermediate is necessary for successive rearrangement. Interestingly and unexpectedly, we found that it is the relative energy of the anionic intermediates that determine the rate of this CnBQ-activated Lossen rearrangement, which is the rate-limiting step (while for classic Lossen rearrangement, the rate-limiting step has been generally considered to be the activation of the hydroxamic acid by various activating agents), and the chlorine or hydrogen ortho to the reaction site at CnBQ is crucial for the stability of the anionic intermediates. (3) There exists a pKa–activation energy correlation for this CnBQ-activated Lossen rearrangement reaction, which can explain why the correlation exists between the rate of the rearrangement and the acidity of the conjugate acid of the anionic leaving group.

Potential Biological and Environmental Implications

Halogenated quinones represent a class of toxicological intermediates that can create a variety of hazardous effects in vivo, including acute hepatoxicity, nephrotoxicity, and carcinogenesis.20−22 Chlorinated benzoquinones (CnBQs) are the major genotoxic and carcinogenic quinoid metabolites of the widely used pesticides chlorophenols such as the wood preservative pentachlorophenol (PCP) and 2,4,5-trichlorophenol. CnBQs have also been observed as reactive oxidation intermediates or products in processes used to oxidize or destroy chlorophenols and other polychlorinated persistent organic pollutants (POPs) in various chemical and enzymatic systems.20−22 Recently, several CBQs were identified as new chlorination disinfection byproducts in drinking water and in swimming pool waters.23,24

Hydroxamic acids have attracted considerable interest recently because of their capacity to inhibit a variety of enzymes, such as metalloproteases and lipoxygenase, and transition metal-mediated oxidative stress.4,9,25,26 Many of the activities of these hydroxamic acids are thought to be due to their metal-chelating properties. In addition to metal chelation, hydroxamic acids are considered to be good α-nucleophiles.

We have shown previously that hydroxyl (or alkoxyl) and carbon-centered quinone ketoxy radicals (leading to DNA damage) and chemiluminescence can be produced during the metal-independent decomposition of H2O2 (or organic hydroperoxides) by TCBQ and other halogenated quinoid carcinogens.27−32 Recently, we found that the formation of these reactive free radicals and TCBQ-induced cellular toxicity were markedly inhibited by benzohydroxamic acid (BHA) and other hydroxamic acids,33,34 via the unusually facile two-consecutive-step Lossen rearrangement mechanism.9 It has been well documented that such radical damage processes (radical oxidations) occur as autocatalyzed chain reactions.35 Whereas, most often, the focus of radical suppression is by inhibiting radical propagation,36 the presented strategy relies on inhibiting radical initiation reactions, i.e., the halogenated quinone-supported homolytical cleavage of peroxides. This is conceptually similar to the iron-chelating efforts for prevention of food spoilage.37

As demonstrated in the present and previous study, hydroxamic acids, in addition to BHA, might be especially suited for detoxification of halogenated quinone carcinogens via the Lossen rearrangement mechanism. Of particular interest in this regard is the fact that two hydroxamic acids are already approved for clinical applications, deferoxamine for iron overload and suberoylanilide hydroxyamic acid (Vorinostat), recently approved for cutaneous T-cell lymphoma.4,9,25,26 Thus, further investigation is needed to determine whether hydroxamic acids can be used safely and effectively as prophylactics for the prevention or treatment of human diseases such as liver and bladder cancer associated with the toxicity of polyhalogenated quinoid carcinogens.

Experimental and Computational Methods

Chemicals

2,5-Dichloro-1,4-benzoquinone (2,5-DCBQ), 2,6-dichloro-1,4-benzoquinone (2,6-DCBQ), 2-chloro-1,4-benzoquinone (2-CBQ), tetrachloro-1,4-benzoquinone (TCBQ), benzohydroxamic aicd (BHA), phenyl isocycanate (Ph-NCO), N,N′-diphenylurea, and aniline were used as purchased. 2-Chloro-5-hydroxy-1,4-benzoquinone (CBQ-OH), 2,3-dichloro-1,4-benzoquinone (2,3-DCBQ), and 2,3,5-trichloro-1,4-benzoquinone (TrCBQ) were synthesized by our research group according to the literature methods.38,39

Analysis of the Reaction of 2,5-DCBQ/BHA

The reaction products of 2,5-DCBQ/BHA were analyzed with high-performance liquid chromatography combined with electrospray ionization quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry (HPLC/ESI-Q-TOF-MS). The HPLC system was equipped with a photodiode array detector. For direct MS analysis, a small portion (20 μL) of reaction solution of 1 mM 2,5-DCBQ with 1, 2, or 4 mM BHA in 1 mL of Chelex-treated CH3COONH4 buffer (100 mM, pH 7.0) at room temperature during the reaction period of 0–30 min was injected into the mass spectrometer. All other MS experimental parameters were the same as described previously.9 The yield of 2-chloro-5-hydroxy-1,4-benzoquinone (CBQ-OH) from 2,5-DCBQ/BHA was quantified by HPLC using synthesized CBQ-OH as standard according to the previous method.28 For HPLC/MS analysis, the reaction solution was injected into an LC-18 C18 column (5 μm, 4.6 × 250 mm) eluted by the mobile phase (50 mM aqueous acetic acid and acetonitrile at 50:50) at a rate of 1.0 mL/min, and the chromatographic eluant was monitored at 200–600 nm and then led to the mass spectrometer through a splitter.

Isolation of the Major Reaction Products (P1 and P2) of 2,5-DCBQ/BHA and the Identification of Decomposition Products of P1 in Aqueous Solution

P1 and P2 were isolated by both semipreparative HPLC and column chromatography. Milligram-scale collection of P1 and P2 (Scheme 2) was performed with semipreparative HPLC apparatus equipped with a UV detector. The reaction solution of 2,5-DCBQ/BHA (1:1 or 1:2, 1 mM 2,5-DCBQ) in 1 mL of Chelex-treated CH3COONH4 buffer (100 mM, pH 7.0) at room temperature after a reaction time of 5 min was injected into a Prep-C18 semipreparative HPLC column (15 cm × 10.0 mm, 3 μm). The mobile phase was 50 mM aqueous acetic acid–acetonitrile (50:50) at a flow rate of 3.0 mL/min. The fractions were monitored at 275 nm and collected manually. Then collected fractions were evaporated to eliminate acetonitrile and then extracted with ethyl acetate. The collected ethyl acetate layer was dried over anhydrous MgSO4 and evaporated to dryness under vacuum. Gram-scale P1 and P2 were isolated by column chromatography. A solution of 2,5-DCBQ (5 mM, 0.885 g) in acetonitrile (10 mL) was added dropwise to 100 mL of Chelex-treated CH3COONH4 buffer (100 mM, pH 7.0) containing BHA (5 mM, 0.685 g) at room temperature. After the mixture was stirred for 5 min, the solid was separated by filtration and purified by silica gel column chromatography with tetrahydrofuran/petroleum ether (1:9) as eluent. Preparation of P2 was carried out as for P1 except that the molar ratio of 2,5-DCBQ/BHA was 1:2 and the purification was carried out by recrystallization from tetrahydrofuran/petroleum ether. Product P1 was golden-yellow and P2 was purple-red, and their purity was 98% as determined using HPLC. 1H NMR and 13C NMR spectra of P1 and P2 were recorded at 400 and 101 MHz, respectively, using tetramethylsilane ((CH3)4Si) as internal standard and DMSO-d6 as solvent. Product P1: 1H NMR δ = 6.50 (s, 1H), 7.36 (s, 1H), 7.54 (m, 2H), 7.64 (m, 1H), 7.88 (m, 2H), 12.85 (s, 1H); 13C NMR δ = 127.7, 128.8, 130.6, 132.6, 143.5, 158.3, 165.8, 178.7, 179.4. Product P2: 1H NMR δ = 6.32 (s, 2H), 7.55 (m, 4H), 7.64 (m, 2H), 7.89 (m, 4H), 12.85 (s, 2H); 13C NMR δ = 127.7, 128.8, 130.5, 132.6. 158.4, 165.5, 180.5. For details, see Supporting Information.

P1 (1 mM) in PB buffer (0.1 mM, pH 8.0) was heated in 60 °C water bath for 2 min and then spotted on analytical thin-layer chromatography (TLC) plates or injected into an HPLC instrument. TLC was carried out on silica gel plates with F-254 indicator. Reactions were monitored by TLC using ethyl acetate–petroleum ether (2:1) as the developing solvent with P1, and reagent-grade N,N′-diphenylurea and aniline as standard references. The product spots on TLC keeping pace with N,N′-diphenylurea or aniline were scraped and extracted with ether for MS analysis. MS showed that N,N′-diphenylurea ([M + H]+ at m/z 213) and aniline ([M + H]+ at m/z 94) were formed during the thermolysis. P1’s thermolysis products were also detected using HPLC with a mobile phase of 50 mM aqueous acetic acid–acetonitrile at 60:40, and the chromatographic eluant was monitored at 275 nm. Sample retention times were compared to those of 2-chloro-5-hydroxy-1,4-benzoquinone (CBQ-OH) and N,N′-diphenylurea as standard references. The thermolysis kinetics of P1 was quantified based on HPLC by the external standardization with isolated P1 and synthesized CBQ-OH.

Computational Methods

All of the computations were performed using Gaussian 09.40 Geometry optimization and corresponding harmonic vibration frequency calculations were executed without any constraints using the B3LYP method41−44 with 6-31+G(d,p) basis set45−48 in the gas phase. All transition states were characterized by one imaginary vibration frequency and the intermediates with no imaginary frequency. Intrinsic reaction coordinate (IRC) calculations were performed on the transition state structures to confirm that the transition state was connected to the correct reactant and product along the reaction paths. Solvent effects were included by performing single-point energy calculations (Esol) on the gas-phase optimized geometries with the CPCM49−52 model and UAKS radii in water at M06-2X/6-31+G(d,p) level of theory. Truhlar’s M06-2X53,54 functional was developed for computations involving main-group thermochemistry, kinetics, and noncovalent interactions, which are important in this work. All of the energies discussed in this paper and the Supporting Information are relative Gibbs free energies (ΔGsol) in water solution at 298 K. The relative enthalpy (ΔHsol) values in solution are also provided for reference. The gas-phase thermal corrections (Hcorr_gas, and Gcorr_gas) were calculated at 298.15 K and 1 atm and used to obtain the enthalpy (Hsol) and free energy (Gsol) values in solution for each structure. Computed molecular structures were drawn with the CYLview program (http://www.cylview.org).

pKa values of Cn–1BQ-OH were computed according to the following formula. To reduce the error of computation, as Klamt et al. had reported,55 we made a linear fitting between the computational and experimental pKa values with five known pKa values of 1 (pKa = 4.1, the average value of the literature data of pKa = 4.0–4.213−15), 7 (pKa =1.5716), 8 (pKa = 1.0910), 9 (pKa1= 0.67, the average value of the literature data of pKa1 = 0.5811 and 0.76;12 pKa2 = 2.88, the average value of the literature data of pKa1 = 2.5812 and 3.1811), 2 (pKa = 2.28), and 3 (pKa =3.63) measured in this work (eq 2). The pKa values of the compounds 1–9 in solution are shown in Table S2, SI. For the activation energies of the reactions of CnBQ/BHA (1:1), see Tables S3, SI.

| 1 |

| 2 |

Acknowledgments

The work in this paper was supported by the Strategic Priority Research Program of CAS Grant No. XDB01020300, NSF China Grants (21237005, 21321004, 20925724, 21077058; 21477139, 21407163), Tianjin Municipal Science and Technology Commission (12JCYBJC16000, 14JCZDJC40300), The Foundation of State Key Laboratory of Environmental Chemistry and Ecotoxicology (KF2012-15), Postdoctoral Science Foundation of China (2014M561078), and NIH Grants (ES11497, RR01008, and ES00210) (B.Z.).

Supporting Information Available

The details on analysis of the reactions of other chlorinated benzoquinones with BHA, the experimental measurement of pKa values of P1 and some hydroxylated chloroquinoid products, the NMR data of P1 and P2, and GC/MS detection of phenyl isocyanate from P1 pyrolysis. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Funding Statement

National Institutes of Health, United States

Supplementary Material

References

- Bauer L.; Exner O.. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 1974,13, 376. [Google Scholar]

- Li J. J.Name reactions: A collection of detailed reaction mechanisms; 3rd expanded ed.; Springer: Berlin, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z.Comprehensive organic name reactions and reagents; John Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Pereira M. M. A.; Santos P. P.. The chemistry of hydroxylamines, oximes, and hydroxamic acids; Rappoport Z., Liebman J. F., Eds.; Wiley: Chichester, England, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Dube P.; Nathel N. F. F.; Vetelino M.; Couturier M.; Aboussafy C. L.; Pichette S.; Jorgensen M. L.; Hardink M. Org. Lett. 2009, 11, 5622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoshino Y.; Okuno M.; Kawamura E.; Honda K.; Inoue S. Chem. Commun. 2009, 2281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orth E. S.; da Silva P. L. F.; Mello R. S.; Bunton C. A.; Milagre H. M. S.; Eberlin M. N.; Fiedler H. D.; Nome F. J. Org. Chem. 2009, 74, 5011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jasikova L.; Hanikyrova E.; Skriba A.; Jasik J.; Roithova J. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 77, 2829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu B. Z.; Zhu J. G.; Mao L.; Kalyanaraman B.; Shan G. Q. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2010, 107, 20686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osman A. M.; Posthumus M. A.; Veeger C.; van Bladeren P. J.; Laane C.; Rietjens I. M. C. M. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 1998, 11, 1319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabir M. K.; Tobita H.; Matsuo H.; Nagayoshi K.; Yamada K.; Adachi K.; Sugiyama Y.; Kitagawa S.; Kawata S. Cryst. Growth Des. 2003, 3, 791. [Google Scholar]

- Mostafa S. I. Transition Met. Chem. (Dordrecht, Neth.) 1999, 24, 306. [Google Scholar]

- Von Sonntag J.; Mvula E.; Hildenbrand K.; Von Sonntag C. Chemistry 2004, 10, 440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey S. I.; Ritchie I. M. Electrochim. Acta 1985, 30, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Schuchmann M. N.; Bothe E.; von Sonntag J.; von Sonntag C. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 1998, 2, 791. [Google Scholar]

- Lente G.; Espenson J. H. New J. Chem. 2004, 28, 847. [Google Scholar]

- Renfrow W. B.; Hauser C. R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1937, 59, 2308. [Google Scholar]

- Bright R. D.; Hauser C. R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1939, 61, 618. [Google Scholar]

- Berndt D. C.; Shechter H. J. Org. Chem. 1964, 29, 916. [Google Scholar]

- Bolton J. L.; Trush M. A.; Penning T. M.; Dryhurst G.; Monks T. J. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2000, 13, 135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song Y.; Wagner B. A.; Witmer J. R.; Lehmler H. J.; Buettner G. R. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2009, 106, 9725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu B. Z.; Shan G. Q. Chem. Res. Toxicol. 2009, 22, 969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y. L.; Qin F.; Boyd J. M.; Anichina J.; Li X. F. Anal. Chem. 2010, 82, 4599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y. L.; Anichina J.; Lu X. F.; Bull R. J.; Krasner S. W.; Hrudey S. E.; Li X. F. Water Res. 2012, 46, 4351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marks P. A.; Breslow R. Nat. Biotechnol. 2007, 25, 84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li N. N.; Zhao D.; Kirschbaum M.; Zhang C.; Lin C. L.; Todorov I.; Kandeel F.; Forman S.; Zeng D. F. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2008, 105, 4796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu B. Z.; Kalyanaraman B.; Jiang G. B. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007, 104, 17575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu B. Z.; Zhao H. T.; Kalyanaraman B.; Liu J.; Shan G. Q.; Du Y. G.; Frei B. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007, 104, 3698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu B. Z.; Shan G. Q.; Huang C. H.; Kalyanaraman B.; Mao L.; Du Y. G. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2009, 106, 11466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu B. Z.; Mao L.; Huang C. H.; Qin H.; Fan R. M.; Kalyanaraman B.; Zhu J. G. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2012, 109, 16046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao J.; Huang C. H.; Kalyanaraman B.; Zhu B. Z. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2013, 60, 177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin H.; Huang C. H.; Mao L.; Xia H. Y.; Kalyanaraman B.; Shao J.; Shan G. Q.; Zhu B. Z. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2013, 63, 459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu B. Z.; Har-El R.; Kitrossky N.; Chevion M. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 1998, 24, 360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witte I.; Zhu B. Z.; Lueken A.; Magnani D.; Stossberg H.; Chevion M. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2000, 28, 693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermans I.; Spier E. S.; Neuenschwander U.; Turra N.; Baiker A. Top Catal. 2009, 52, 1162. [Google Scholar]

- von Gadow A.; Joubert E.; Hansmann C. F. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1997, 45, 632. [Google Scholar]

- Let M. B.; Jacobsen C.; Meyer A. S. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 2369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saby C.; Male K. B.; Luong J. H. Anal. Chem. 1997, 69, 4324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Male K. B.; Luong J. H. Electrophoresis 2003, 24, 1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frisch M. J.et al. Gaussian 09, Revision B.01; Gaussian, Inc., Wallingford, CT, 2009.

- Becke A. D. J. Chem. Phys. 1993, 98, 1372. [Google Scholar]

- Becke A. D. Phys. Rev. A 1988, 38, 3098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becke A. D. J. Chem. Phys. 1993, 98, 5648. [Google Scholar]

- Lee C.; Yang W.; Parr R. G. Phys. Rev. B 1988, 37, 785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hehre W. J.; Ditchfield R.; Pople J. A. J. Chem. Phys. 1972, 56, 2257. [Google Scholar]

- Hariharan P. C.; Pople J. A. Theor. Chim. Acta 1973, 28, 213. [Google Scholar]

- Clark T.; Chandrasekhar J.; Spitznagel G. W.; von Schleyer P. R. J. Comput. Chem. 1983, 4, 294. [Google Scholar]

- Spitznagel G. W.; Clark T.; Chandrasekhar J.; von Schleyer P. R. J. Comput. Chem. 1982, 3, 363. [Google Scholar]

- Barone V.; Cossi M. J. Phys. Chem. A 1998, 102, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Cossi M.; Rega N.; Scalmani G.; Barone V. J. Comput. Chem. 2003, 24, 669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takano Y.; Houk K. N. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2005, 1, 70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klamt A.; Schüürmann G. J. Chem. Soc., Perkin Trans. 2 1993, 3, 799. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y.; Truhlar D. G. Acc. Chem. Res. 2008, 41, 157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Y.; Truhlar D. G. Theor. Chem. Acc. 2008, 120, 215. [Google Scholar]

- Klamt A.; Eckert F.; Diedenhofen M.; Beck M. E. J. Phys. Chem. A 2003, 107, 9380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.