Abstract

The objective of the present study was to examine prospective, bidirectional associations among posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms, coping style, and alcohol involvement (use, consequences), in a sample of trauma-exposed students just entering college. We also sought to test the mechanistic role that coping may play in associations between PTSD symptoms and problem alcohol involvement over time. Participants (N=734) completed measures of trauma exposure, PTSD symptoms, coping, and alcohol use and consequences in September of their first college year (Y1) and again each September for the next two years (Y2–3). We observed reciprocal associations between PTSD and negative coping strategies. In our examination of a mediated pathway through coping, we found an indirect association from alcohol consequences and PTSD symptoms via negative coping, suggesting that alcohol consequences may exacerbate posttraumatic stress over time by promoting negative coping strategies. Trauma characteristics such as type (interpersonal vs. non-interpersonal) and trauma re-exposure did not moderate these pathways. Models also were invariant across gender. Findings from the present study point to risk that is conferred by both PTSD and alcohol consequences for using negative coping approaches, and through this, for posttraumatic stress. Interventions designed to decrease negative coping may help to offset this risk, leading to more positive outcomes for those students who enter college with trauma exposure.

Introduction

Posttraumatic Stress and Alcohol involvement in College Students

Trauma exposure and posttraumatic stress (PTSD) are surprisingly common in college students. As many as ¾ of college students report having experienced a traumatic event, and rates of PTSD in college samples are similar (i.e. around 8–9%) to those in general community samples (Humphrey & White, 2000; Lauterbach & Vrana, 2001; Marx & Sloan, 2003; McDevitt-Murphy, Weathers, Flood, Eakin, & Benson, 2007; Read et al., 2011; Smyth et al., 2008). As such, trauma and posttraumatic stress represent a significant mental health issue affecting this population (Bachrach & Read, 2012; Duncan, 2000; Elhai & Simons, 2007; Flood et al., 2009; Green et al., 2005). Also common in college students is heavy and problematic alcohol involvement (Dawson, Grant, Stinson, & Chou, 2004; Wu, Pilowsky, Schlenger, & Hasin, 2007) which can lead to hazardous outcomes both acutely (O’Malley & Johnston, 2002) and in the longer-term (Arria, Vincent, & Caldeira, 2009; McCabe, West, & Wechsler, 2007).

In clinical populations, posttraumatic stress and problem drinking long have been linked to one another (McFarlane et al., 2009; Ouimette, Ahrens, Moos, & Finney, 1997; Shipherd, Stafford, & Tanner, 2005). In recent years, a small but a burgeoning literature also has identified such a link in college samples (e.g., Haller & Chassin, 2012; Read et al., 2012; Read, Wardell, & Colder, 2013; Stappenbeck, Bedard-Gilligan, Lee, & Kaysen, 2013).

Several theories have been forwarded to explain these associations. Prominent among these are self-medication models and vulnerability models (e.g., Chilcoat & Breslau, 1998). Self-medication models assert that drinking occurs in those with PTSD as an effort to alleviate (medicate) PTSD symptoms (e.g., Khantzian, 2003; Saladin et al., 1995.) whereas vulnerability models suggest that problem alcohol use may exacerbate PTSD symptoms with more use associated with more symptoms over time (Giaconia et al., 2000; Stewart & Conrod, 2008). Capturing elements of both self-medication and vulnerability models are social learning conceptualizations, which emphasize reciprocal associations between these phenomena, with each affecting the other over time as learning occurs.

The Role of Coping

Coping is an individual difference variable that describes a habitual way of approaching challenges (Menaghan, 1983), and that has been implicated in the etiology of both PTSD and problem drinking. Coping also often is included in models of connectedness between psychological distress and alcohol involvement (e.g., Cooper et al., 1992; Hruska & Delahanty, 2012). As such, the delineation of the role of coping may shed light on the unique and shared course of PTSD and alcohol outcomes, and may point to important directions for intervention.

Coping approaches have been characterized in many ways, with the most basic of these being positive and negative coping. These two dimensions of coping have been shown both conceptually and empirically to be distinct constructs that are differentially related to functional outcomes (Carver et al., 1989; Lazarus & Folkman, 1984; Moos & Holahan, 2003; Moos, 1997). Positive coping tends to be approach- or problem-focused (e.g., strategizing, consulting with others for advice). In contrast, negative coping is marked by avoidance (e.g., ignoring the problem) or other maladaptive efforts (e.g., self-blame, venting) that worsen rather than resolve the challenge (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984; Hruska & Delahanty, 2012; Park, Armeli, & Tennen, 2004; Veenstra et al., 2007). Negative coping in particular has been linked to the development of PTSD symptoms following trauma (Ehlers & Clark, 2000; Ullman et al., 2007; Witvliet, Phipps, Feldman, & Beckham, 2004), and to problem drinking (e.g., Moos & Moos, 2006; Corbin, Farmer, & Nolen-Hoekseman, 2013; Dermody, Chong, & Manuck, 2013; Park et al., 2004).

To date, the literature has tended to focus on how coping may influence deleterious PTSD and drinking outcomes, neglecting the ways in which coping may be affected by or may even serve to maintain these clinical conditions.

Bidirectional Pathways

As noted, learning models posit bidirectional associations between PTSD and alcohol use and problems. These models also highlight other patterns of bidirectionality that are relevant to how PTSD and alcohol involvement may be sustained and maintained over time.

For example, these models suggest that coping – particularly negative coping – may both influence and be influenced by posttraumatic stress symptoms in a feed-forward, reciprocal pattern (e.g., Foa & Kozak, 1986; Snyder & Pulvers, 2001). In such cases, learned maladaptive coping approaches contribute to the development and maintenance of posttraumatic stress, and conversely, PTSD symptoms may compromise an individual’s ability to learn and to implement effective coping strategies. A small handful of empirical studies have tested these theorized reciprocal associations. These studies have found PTSD to predict negative coping over time, and also have found coping to contribute to PTSD and psychological distress more broadly several months later (e.g. Badour et al., 2012; Littleton, Axsom, & Grills-Taquechel, 2011). The bidirectional course of PTSD and coping over longer periods of time has not been studied.

Pathways between alcohol involvement and coping also may be reciprocal. Theories of stress and coping suggest that when psychological, emotional, or instrumental resources are taxed, effective coping strategies will be compromised and perhaps supplanted with other, less adaptive approaches (Hobfoll, 1989). In line with this, as hazardous alcohol use often represents a drain on personal resources (friend/family conflict, physical health effects, academic/work problems), resources may be drawn away from efforts to successfully adapt to trauma, increasing reliance on negative coping strategies. In turn, greater negative coping may then promote further problematic alcohol use. Surprisingly, the prospective influence of alcohol involvement on coping strategies has not to our knowledge been examined. Nor have reciprocal paths between coping and alcohol involvement been tested.

PTSD and Alcohol Involvement Consequences: Coping as Intermediary

In addition to the reciprocal role that coping may play in maintaining PTSD symptoms and alcohol involvement over time, coping also has been viewed as a factor that may serve to link relations between PTSD and problem drinking prospectively. To date, coping has been studied as a mechanism of PTSD- alcohol associations mostly in the context of a self-medication framework (Khantzian, 2003). Specifically, in response to stress, an individual may turn to maladaptive (e.g., negative, avoidance-based) coping approaches, which then lead to problem alcohol use (Brown, Read, & Kahler, 2003; Ouimette et al., 1997; 1999; Staiger et al., 2009; Yeater, Austin, Green, & Smith, 2010). However, coping may play a role in the path from alcohol involvement to PTSD outcomes as well. As noted, consequences from drinking may compromise coping resources, resulting in poorer post-trauma adaptation and greater PTSD symptoms. Though some studies have examined coping as a mediator of PTSD on drinking outcomes (Veenstra et al., 2007; Yeater et al., 2010), there have been no prospective tests of coping as a mediator of the reverse pathway, whereby alcohol influences PTSD outcomes.

Whether and how coping may play a role in the course of PTSD-alcohol associations has important clinical implications. Coping skills interventions designed to decrease negative coping and to increase positive coping approaches can facilitate reductions in both PTSD symptoms (e.g., Falsetti & Resnick, 2000), and problem drinking (e.g., Miller, Wilbourne, & Hettema, 2003). If found to be an intervening variable, coping could be targeted to reduce shared risk, or to disrupt the cycle of PTSD and problem drinking. Delineation of the risk or protective role of coping may be critical at the transition into college, as at this time students are developing and refining their own coping approaches in the context of a new environment and new challenges.

Trauma Characteristics

From the extant literature, it is clear that it is trauma-related PTSD symptoms, rather than trauma exposure alone that are the active mechanism in associations with drinking outcomes (Breslau & Davis, 1992; Epstein, Saunders, Kilpatrick, & Resnick, 1998; Stewart & Conrod, 2003). Nonetheless, particular aspects of the trauma(s) still may exert an important influence on PTSD-alcohol associations as these pathways may differ depending on the nature and history of the trauma. For example, trauma re-exposure is the rule rather than the exception in college and other samples (Briere & Runz, 1987; Hanson, Kilpatrick, Falsetti, & Resnick, 1995; Orcutt, Erickson., & Wolfe, 2002; Roodman & Clum, 2001). Such re-exposure has been shown to exert a particularly toxic influence on a range of psychosocial outcomes including PTSD and substance use (Ford et al., 2010; Kaltman et al., 2005; Norris, 1992; Read et al., 2011; Zayfert, 2012). As such, relations among PTSD, coping, and alcohol outcomes over time may vary for those who are re-exposed to trauma during that period.

Another trauma characteristic that may be an important moderator of PTSD, coping, and alcohol associations is trauma type. Specifically, evidence suggests that interpersonal traumas (e.g., sexual assault, child abuse, partner violence) may be particularly pathogenic relative to non-interpersonal traumas (e.g., motor vehicle accident, natural disaster), and as such, may be relevant to PTSD-alcohol pathways over time (Foa et al., 1989; Forbes et al., 2012; Ford et al., 2011). Indeed, some data show that the course of PTSD differs for those with interpersonal traumas relative to other trauma types (Chung & Breslau, 2008; Forbes et al., 2012).

Gender

Though the literature has been mixed, at least some prior work has found gender differences in pathways between PTSD and drinking (e.g., Bornavolova et al., 2009; Sonne, Back, Zuniga, Randall, & Brady, 2003; Stewart et al., 2002). Further, some data also show differences between men and women in the role of coping in PTSD-alcohol associations (Lehavot et al., 2014). Accordingly, in this study we tested our models for gender invariance.

The Present Study

The objective of the present study was to delineate the role of coping in prospective associations between PTSD symptoms and alcohol use and consequences in a sample of trauma-exposed young adults matriculating into college. Assessing students over a two-year period, we examined how negative and positive coping approaches were prospectively associated with PTSD symptoms and alcohol involvement. We also tested mediational pathways from PTSD and alcohol use and consequences in Year 1 to these same outcomes in Year 3, though Year 2 coping to examine coping’s mechanistic role in these pathways. We expected that PTSD symptoms at the time of college matriculation would be associated with greater negative coping the following year, which in turn would predict more alcohol consequences in the third college year. We also expected that alcohol consequences at matriculation would be indirectly associated with increases in PTSD symptoms, through the influence of negative coping. The literature has highlighted that associations between PTSD and alcohol outcomes are relevant to problematic use rather than general consumption. As such, we did not predict prospective pathways to and from PTSD, coping and alcohol use. As the literature on the role of coping in PTSD – drinking relations has focused primarily on negative coping, we did not formulate specific hypotheses regarding the meditational role of positive coping, though these pathways were tested in our prospective models.

We also examined trauma characteristics and gender as moderators of our theorized pathways. Specifically, we modeled the effects of trauma re-exposure and trauma type on coping pathways of interest. Given the large literature suggesting a unique toxicity for both re-victimization and interpersonal traumas, we posited that paths would be stronger for those whose trauma histories were characterized by these features. We also tested our models for gender invariance. Given that the literature is both sparse and mixed, we forwarded no specific hypotheses about the ways in which gender might moderate pathways of interest.

Method

Participants

Participants were incoming freshmen at two mid-size public universities in the northeastern (Site 1) and southeastern (Site 2) United States. The present analysis included students with prior trauma exposure at the time of college entry, and was comprised of 734 (73% female) participants. At T1, the average age was 18.11 (SD=0.46). Seventy-one percent of the participants identified as Non-Hispanic Caucasian (n = 519), 11% as Asian (n =80), 11% as Black (n =80), 3% as Hispanic/Latino (n = 24), and 3% as multiracial (n = 24), and less than 1% (n = 3) as other. Four participants did not report ethnicity.

Procedure

Participants in this study were drawn from a larger longitudinal study of PTSD and substance use over the course of college. Procedures for deriving this longitudinal sample have been described in detail in other published reports (see Read, Ouimette, White, Colder, & Farrow, 2011; Read et al., 2012; Read et al., 2013), but below we provide a brief overview.

Initial screening and longitudinal sample selection

A screen was used to identify eligible participants for the longitudinal portion of the study (below). In the summer prior to matriculation, all incoming students were invited to complete an eligibility screening survey either online or by paper-and-pencil. This screening survey assessed DSM-IV-TR Criterion A trauma exposure and PTSD symptoms. Participants received a $5 gift card upon survey completion. Comparable to other online surveys with similar methodologies (e.g., Neighbors, Geisner, & Lee, 2008; Lewis et al., 2007), we achieved a 58% response rate, with a final screening pool of 3,014 from which we drew our longitudinal sample.

Based on responses to the eligibility screen, students were selected for participation in the longitudinal study. Because we aimed to recruit an enriched sample with sufficient representation of students with PTSD symptoms, we invited all (n=649) students who endorsed (1) at least one Criterion A trauma and (2) at least one symptom from each of the three PTSD symptom clusters (i.e., B, C, and D; “partial PTSD” see Schnurr et al., 2000). We also randomly selected another 585 students who did not meet trauma criteria. Thus, this enriched sample included those both with and without trauma exposure and PTSD symptoms at baseline. E-mails with a link to the baseline (Freshman Year September; Y1) survey were sent to this selected sample (N = 1,234). Eighty-one percent (N=1,002) of those invited to participate completed the baseline survey.

The present sample

As the objective of this study was to model ongoing reciprocal associations among PTSD symptoms, coping, and alcohol outcomes over time. We included only participants with trauma exposure as it is only these individuals who could conceivably develop PTSD. Thus, our sample was comprised of 734 students who reported at least one lifetime Criterion A trauma (A1 and A2) at Y1. This included participants both with and without PTSD symptomatology. Assessments completed at the September time point in each of three academic years were used for analyses. In Year 1, participants were paid $20 for survey completion. This increased by $5.00 in each year of the study so that payments were $25 and $30 for Years 2 and 3, respectively. All payments were made in gift cards to local retailers.

Measures

Trauma Exposure

The Traumatic Life Events Questionnaire (TLEQ; Kubany et al., 2000©)† was used to assess trauma exposure. The DSM-IV-TR defines trauma as exposure to a traumatic event (A.1), accompanied by fear, helplessness, or horror (A.2). The TLEQ is a 21-item self-report questionnaire that assesses a range of traumatic experiences consistent with the DSM-IV-TR definition, including the subjective responses that comprise Criterion A.2. This measure has demonstrated good psychometric properties, and has been used with a range of populations, including college students (Kubany et al., 2000). This measure was used for sample selection (see above), to identify those in the sample who had experienced new traumas during the period of follow-up, and also to characterize the nature (i.e., interpersonal versus non-interpersonal) that participants had experienced.

Re-exposure to trauma was determined by examining whether any Criterion A events was endorsed at later time points. We also classified traumas according to their type; with data from the TLEQ, we categorized traumas as either interpersonal or non-interpersonal following the work of Lilly and Valdez (2012). Interpersonal trauma was defined as an event in which an individual is personally assaulted or violated by another human being (Lilly & Valdez, 2012; Orcutt, Pickett, & Pope, 2005). Eleven items of the TLEQ map onto this definition including being robbed or present during a robbery; hit or beaten by a stranger; threatened with death or caused serious physical harm; physically punished in a way that resulted in significant physical harm; slapped, punched, kicked or beaten up by a partner; childhood sexual assault by person 5 or more years older; childhood sexual assault by an age peer; adolescent sexual assault; adult sexual assault; other unwanted sexual attention and being stalked.

Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms

Posttraumatic stress symptoms were assessed at each time point using the PTSD Checklist-Civilian Version (PCL-C; Weathers, Huska, & Keane, 1991; Weathers, Litz, Herman, Huska, & Keane, 1993). This 17-item measure assesses re-experiencing symptoms, avoidance/numbing symptoms, and arousal symptoms of the PTSD construct consistent with the DSM-IV-TR. Used widely in both patient and non-patient populations, including college students, the PCL-C corresponds strongly to gold-standard interview measures of PTSD (Andrykowski, Cordova, Studts, & Miller, 1998; Blake et al., 1995; Lang, Laffaye, Satz, Dresselhaus, & Stein, 2003). Participants reported according to a 5-point scale how much they have been bothered by each of the 17 symptoms in the past month. Using empirically derived cut-scores from Blanchard, Jones, Buckley, Forneris (1996), each symptom was re-coded from the 5-point Likert-type scale to a dichotomous scale, so that symptoms were identified as either present (1) or absent (0) depending on the original 5-point rating endorsed by the participant. Thus, the possible range of PCL scores is 0–17. Items were summed to obtain a total symptom count. This method is most consistent with how clinical diagnostic interviews would classify symptom scores, and is more rigorous in its classification of PTSD, as recorded scores includes only symptoms that fall above an empirically determined severity threshold. Observed PCL scores in this sample ranged from 0 to 17 at each time point. Internal reliability in this sample was strong (Cronbach’s alphas from .87 to .91 across assessments).

Alcohol use

All participants were provided with a standard drink measurement chart to increase accuracy of reporting. Information about typical past month consumption was taken from a measure based on the Daily drinking Questionnaire (DDQ; Collins, Parks, & Marlatt, 1985). In this measure, participants estimate the number of drinks they consume on a typical Monday, Tuesday, etc. in the past month. From this we calculated a typical, past month weekly quantity score. Scores on this index ranged from 0 to 60.

Alcohol problems

Problems from alcohol use were assessed with the 48-item Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire (YAACQ; Read et al., 2006). This measure assesses a broad range of consequence types ranging in severity. Eight domains of alcohol-related problems are assessed: social/interpersonal, academic/occupational, risky behavior, impaired control, poor self-care, diminished self-perception, blackout drinking, and physiological dependence. All domains load on a single higher-order consequence factor. This measure shows good internal and test-retest reliability, and strong concurrent validity with other alcohol problems measures (Read et al. 2006; Read et al., 2007). Participants provided yes (coded 1) or no (coded 0) responses, indicating whether they had experienced that problem in the past month. A total alcohol problems score was created by summing responses to all of the items. Participants who reported that they had not consumed alcohol in the past month received a score of zero on this scale. Cronbach’s alpha for the YAACQ ranged from .93 to .95 across the three time points. Scores on this measure ranges were from zero (all time points) to between 41 and 46 (for Yrs1, 2, and 3) indicating ample variability in this measure.

Coping

We used the 28-item Brief COPE (Carver, 1997) to assess coping approaches. Participants rated on a Likert-type scale the extent to which they use various strategies to cope with stress. This measure has been used in a variety of clinical and non-clinical populations (Gilts et al., 2012; Hur et al., 2012; Meyer, 2001) including college students (Miyazaki et al., 2008; Schnider et al., 2007). Following work by Littman (2006), we created two subscales from the 28 COPE items, which reflected positive (e.g., “I take action to try to make the situation better”, “I try to come up with a strategy about what to do”) and negative coping (e.g., “I give up trying to deal with it”, “I criticize myself”). These subscales showed good internal reliability; alphas ranged from .81–.83 (positive coping), and .71–.74 (negative coping) across the time points. The correlation between the two subscales (r= .10) was significant (p <.01) and positive (see Table 1). Higher scores on each subscale represent greater use of that coping strategy. Observed ranges across time points were from 1–4 for both positive and negative coping.

Table 1.

Means and Standard Deviations for Model Variables

| Model Variable |

Total Sample Mean (SD) |

Females Mean (SD) |

Males Mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. PTSD Symptoms Y1 | 4.60 (4.06) | 4.71 (4.09) | 4.32 (3.98) |

|

|

|||

| 2. Negative Coping Y1** | 2.18 (0.40) | 2.21 (0.40) | 2.12 (0 .40) |

|

|

|||

| 3. Positive Coping Y1 | 2.65 (0.54) | 2.67 (0.56) | 2.59 (0.51) |

|

|

|||

| 4. Alcohol Cons Y1 | 5.93 (7.76) | 5.83 (7.68) | 6.19 (8.33) |

|

|

|||

| 5. Alcohol Quantity Y1** | 6.39 (9.39) | 5.66 (8.49) | 8.37 (11.24) |

|

|

|||

| 6. PTSD Symptoms Y2 | 2.79 (3.81) | 2.92 (3.80) | 2.45 (3.82) |

|

|

|||

| 7. Negative Coping Y2* | 2.13 (0.42) | 2.16 (0.42) | 2.08 (0.41) |

|

|

|||

| 8. Positive Coping Y2 | 2.63 (0.54) | 2.65 (0.53) | 2.56 (0.55) |

|

|

|||

| 9. Alcohol Cons Y2 | 4.55 (7.64) | 4.57 (7.36) | 4.49 (8.40) |

|

|

|||

| 10. Alcohol Quantity Y2*** | 6.52 (9.45) | 5.66 (7.79) | 8.86 (12.64) |

|

|

|||

| 11. PTSD Symptoms Y3 | 2.45 (3.77) | 2.49 (3.85) | 2.35 (3.55) |

|

|

|||

| 12. Negative Coping Y3** | 2.13 (0.43) | 2.16 (0.43) | 2.04 (0.42) |

|

|

|||

| 13. Positive Coping Y3*** | 2.62 (0.53) | 2.67 (0.53) | 2.50 (0.50) |

|

|

|||

| 14. Alcohol Cons Y3 | 3.90 (6.67) | 3.61 (6.20) | 4.70 (7.72) |

|

|

|||

| 15. Alcohol Quantity Y3*** | 6.00 (8.72) | 5.17 (7.15) | 8.28 (11.73) |

|

|

|||

Note. Asterisks denote gender differences.

p<.05

p<.01

p<.001

Data Analytic Approach

Management of Missing Data

Complete data were provided by 685 (93%) participants at year 1 (Y1), 651 (89%) participants at year 2 (Y2), and 653 (89%) participants and year 3 (Y3). There were no differences between participants who had complete data at all time points (n = 580) and those who were missing some data (n = 154) on age, ethnicity, gender, trauma type (interpersonal vs. non interpersonal) or re-traumatization status (p > .05). There were also no differences between participants with missing data and those without missing data on PTSD symptoms, positive and negative coping, or alcohol problems (p > .05). However, participants with missing data reported slightly less Y1 alcohol use (M=5.05, SD=9.67) than participants who had no missing data (M=6.75, SD=9.28; p = .045). We used full information maximum likelihood with robust estimation for our analyses. This approach includes cases with some missing data and uses all available information, resulting in less biased estimates than list-wise deletion of cases with missing data (Enders, 2010; Muthén & Muthén, 2012).

Descriptive Analysis

We first examined descriptive statistics, bivariate associations and distributional properties of each variable at the three time points. The positive and negative coping variables approximated normal distributions. The PTSD symptoms, and alcohol use and problems variables were moderately skewed and kurtotic (skewness ranged from 0.81 to 2.76; kurtosis ranged from 0.16 to 10.52). Thus, we used robust estimation to adjust our model fit and standard error estimates to accommodate this non-normality. No extreme outlying observations were detected when examining the distribution of each variable.

Given that we also were interested in whether pathways among PTSD, coping, and alcohol involvement were different for women and men, we also tested model variables for gender differences. These differences (PTSD symptoms, positive and negative coping, and alcohol use and problems) were examined with t-tests. Using chi-square analyses, we also examined differences in our model grouping variables (interpersonal vs. non-interpersonal trauma, re-victimization status).

Prospective Analysis

To examine the prospective associations among PTSD symptoms, coping, alcohol use, and alcohol consequences, we specified a cross-lagged panel model using observed variables in Mplus version 7 (Muthén & Muthén, 2012). These models are widely used in longitudinal studies to examine the prospective associations from one variable to another variable (i.e., cross-lags) while controlling for stability over time within variables (i.e., autoregressive effects) as well as concurrent associations (i.e., covariances; Kenny, 2005). We chose this approach because it allowed us to examine bi-directional, reciprocal relationships among these variables while simultaneously exploring the indirect associations between PTSD and alcohol consequences via coping strategies. To specify the cross-lagged panel model, we modeled PTSD symptoms, alcohol use and consequences, and positive and negative coping at all three time points, and estimated all autoregressive paths from Y1 to Y2 and from Y2 to Y3. We also estimated the cross-lagged associations among the PTSD, alcohol use/consequences and coping constructs. However, we did not model cross-lagged paths between the positive and negative coping constructs (e.g., there was no path from negative coping at Y1 to positive coping at Y2). Finally, we freely estimated the within time-point covariances (Y1) and residual covariances (Y2 and Y3) among all of the variables.

We considered common fit indices to evaluate model fit, including the normed chi-square index (χ2/df), Root-Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), and the Tucker-Lewis index (TLI). A model’s fit was considered good if χ2/df < 3.0, RMSEA < .05, CFI > .95, and TLI > .95. (Hu & Bentler, 1999; Kline, 2005). We planned to consult modification indices if model fit was not adequate to identify potential sources of misfit. Because modification indices provide data-driven suggestions for model re-specification and as such, must be applied judiciously (Hoyle, 1995; Kline, 2005), we conservatively adopted the guideline of 10 (Muthen & Muthen, 2012), a value which suggests a modification that will add substantial change to overall model fit. We also considered only modification indices that made clear conceptual sense.

In order to examine the possible mediational role of coping in the association between PTSD symptoms and alcohol consequences, we used bootstrapping to derive bias-corrected confidence intervals (CIs) for the specific indirect associations. A 95% CI that does not contain zero suggests a statistically significant indirect association. First, because the self-medication hypothesis suggests that PTSD may lead to alcohol consequences due to maladaptive coping strategies, we tested the indirect paths from PTSD symptoms at Y1 to alcohol consequences at Y3 via positive and negative coping at Y2. As noted, we planned also to test the opposite direction of this effect – that alcohol consequences might exacerbate PTSD symptoms through their effect on coping strategies. Thus, we also tested the indirect associations from alcohol consequences at Y1 to PTSD symptoms at Y3 as mediated by Y2 positive and negative coping.

We also examined trauma-related moderators (trauma re-exposure, interpersonal vs. non-interpersonal trauma history) of the PTSD-Coping-Alcohol Involvement pathways. To do this, we estimated multiple group models and used nested chi-square tests to examine model equivalence between (1) those who had been re-exposed to trauma during the period of assessment (n=352 between Y1 and Y2; n=244 between Y2 and Y3) and those who had not; and (2) those whose traumas were interpersonal in nature (n=333), versus those whose trauma was non-interpersonal. For trauma re-exposure, this was done separately for the paths from Y1 to Y2 and from Y2 to Y3, and participants were grouped according to whether they reported a new trauma during the relevant time frame for each of these tests. Finally, we again applied a multiple groups modeling approach to test the model for gender invariance, to ascertain whether pathways differed for men and for women. A program developed by Crawford and Henry (2003) was used to calculate scaled chi-square difference tests for the nested models given that robust ML estimation was used (Satorra & Bentler, 2001).

Results

Descriptive Statistics and Bivariate Correlations

The most frequently reported traumas in this sample were sudden unexpected loss of a loved one (n=465, 63.4%), life threat to a loved one (n=310, 42.4), childhood exposure to family violence (n=203, 27.7%), motor vehicle or other accident (n=186, 25.3%), sexual victimization (n= 142, 19.3%), and threats of interpersonal violence (n= 122, 16.6%). Sixty percent (n=417) of students in this sample reported re-exposure to a criterion A trauma during the two year assessment period. Approximately ½ of the participants (n=371, 50.6%) reported a history of interpersonal trauma.

See Table 1 for means and standard deviations of study variables by gender. Bivariate correlations among model variables are presented in Table 2. As would be expected, we observed significant gender differences on typical quantity of alcohol consumption at every time point (all ps. < .05). We also observed statistically significant differences on negative coping at each time point, and positive coping at T3, with women showing higher scores on these variables. In terms of gender differences in our grouping variables, results of chi-square analyses showed that men and women differed in interpersonal victimization histories, χ2(1, N = 734) = 8.46, p = 0.004; fifty-eight percent (n=309) of the women in this trauma-exposed sample reported a history of interpersonal victimization, compared to forty-six percent (n=91) of men. Women (68%, n=342) also were more likely to be re-exposed to trauma than were men (41%, n=75), χ2(1, N = 688) = 41.45, p < .001.

Table 2.

Bivariate correlations among model variables.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. PTSD Symptoms Y1 | ||||||||||||||||

| 2. Negative Coping Y1 | .33** | |||||||||||||||

| 3. Positive Coping Y1 | −.09* | .03 | ||||||||||||||

| 4. Alcohol Cons Y1 | .21** | .33** | −.12** | |||||||||||||

| 5. Alcohol Quantity Y1 | .09* | .20** | −.10** | .63** | ||||||||||||

| 6. PTSD Symptoms Y2 | .36** | .25** | −.07 | .17** | .09* | |||||||||||

| 7. Negative Coping Y2 | .25** | .47** | −.02 | .23** | .13** | .34** | ||||||||||

| 8. Positive Coping Y2 | −.04 | −.10** | .55** | −.13** | −.13** | −.06 | .10** | |||||||||

| 9. Alcohol Cons Y2 | .10* | .22** | −.01 | .53** | .38** | .19** | .33** | −.05 | ||||||||

| 10. Alcohol Quantity Y2 | .00 | .12** | −.06 | .45** | .61** | .03 | .12** | −.11** | .60** | |||||||

| 11. PTSD Symptoms Y3 | .37** | .18** | −.01 | .06 | .00 | .41** | .27** | −.01 | .12** | .01 | ||||||

| 12. Negative Coping Y3 | .17** | .46** | .01 | .22** | .14** | .26** | .51** | −.05 | .26** | .12** | .33** | |||||

| 13. Positive Coping Y3 | −.06 | −.07 | .49** | −.10* | −.08* | −.03 | −.01 | .57** | −.03 | −.07 | −.02 | .10* | ||||

| 14. Alcohol Cons Y3 | .12** | .18** | −.03 | .42** | .36** | .13** | .20** | −.10** | .55** | .39** | .16** | .29** | −.06 | |||

| 15. Alcohol Quantity Y3 | −.01 | .08* | −.07 | .37** | .51** | .03 | .09* | −.09* | .42** | .66** | .00 | .12** | −.06 | .62** |

Note. Y = Year

p < .01

p < .05.

The baseline sample was recruited to have a strong representation of students with posttraumatic stress symptoms, and so at baseline approximately 21% (n=151) of the sample met criteria for PTSD according to scoring guidelines from Blanchard et al. (1996). Another 21% (n=152) met criteria for “partial” PTSD (i.e., at least one symptom in each symptom cluster; Mylle & Maes, 2004; Schnurr et al., 2000).

Cross-lagged Panel Model

Model fit and modification

The initial cross-lagged panel model with PTSD symptoms, coping, and alcohol consequences at the three time points did not fit the data well, χ2 (29) = 173.77, p <.001, χ2/df = 5.99, RMSEA = .08, TLI=.79, CFI=.94. Modification indices suggested that the direct autoregressive paths from Y1 to Y3 should be estimated for the negative coping, positive coping, and PTSD symptoms variables (modification indices ranged from 30.97 to 42.52). This suggests that change patterns in these variables may be complex, with students showing year-to-year fluctuations in change. Accordingly, we re-specified the model to estimate the direct paths from Y1 to Y3. The addition of these parameters resulted in a final model that fit the data well, χ2 (26) = 59.23, p <.001, χ2/df = 2.28, RMSEA = .04, TLI=.95, CFI=.99.

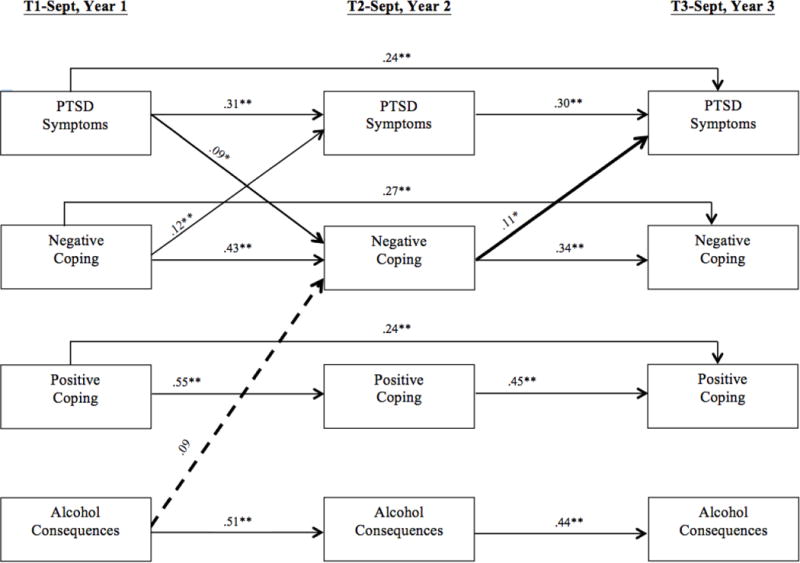

Direct Associations

Figure 1 shows the final modified model. Although all paths were retained in the model regardless of level of significance, only paths that were statistically significant (p > .05) are depicted in the figure for clarity. The alcohol use variable did not have any significant direct or indirect associations with PTSD symptoms or either coping variable. Given the absence of associations with any model variables, the alcohol use variables are omitted from Figure 1, although they were included in the final model.

Figure 1.

Cross-lagged panel model of the prospective associations among PTSD symptoms, coping, and alcohol consequences. Alcohol use at each time point was also included in the model but was omitted from the figure for simplicity due to a lack of statistically significant cross-lagged associations with the other variables in the model. Statistically significant (p < .05; solid arrows) paths are shown. All nonsignificant paths (p > .05) were retained in the final model but were omitted form the figure for clarity. The path from Y1 alcohol consequences to Y2 negative coping (dashed arrow) was not significant but is depicted in the figure to illustrate a significant indirect path from alcohol consequences to PTSD symptoms via negative coping (bolded lines), which was statistically significant (95% CI does not contain zero). The other indirect effects were not significant. **p < .01, *p < .05.

The prospective associations among negative coping and PTSD symptoms were reciprocal. Negative coping significantly predicted increased PTSD symptoms from Y1 to Y2 and from Y2 to Y3, suggesting that negative coping contributes to a worsening of PTSD symptoms. Similarly, PTSD symptoms had a significant prospective effect on negative coping from Y1 to Y2, in that higher levels of PTSD symptoms at Y1 were associated with an increase in negative coping strategies at Y2. We also observed a similar trend for the path from Y2 PTSD symptoms to Y3 negative coping, though this path did not did not reach statistical significance (p=.10). Positive coping and PTSD symptoms were not reciprocally related to one another.

The path from alcohol consequences at Y1 to negative coping at Y2 was not statistically significant (p=.07). However, this path is shown in the figure because it was part of a significant indirect path to PTSD symptoms at Y3 (see below). We also observed a similar prospective effect for the hypothesized path from Y2 alcohol consequences to Y3 negative coping which also did not quite meet .05 statistical significance criterion (p=.07).

Indirect Associations

There were no significant indirect associations from Year 1 PTSD symptoms to Year 3 consequences via positive or negative coping at Year 2 (95% CIs contain zero). In contrast, we did find that the indirect effect from alcohol consequences at Y1 to PTSD symptoms at Y3 via negative coping at Y2 – although weak – was statistically significant, B = .005, 95% CI [<.001, .015], β = .010, suggesting that alcohol consequences may prospectively increase negative coping which then in turn exacerbates PTSD symptoms.ˆ The indirect association via positive coping at Y2 was not significant (95% CI contains zero).

Trauma Characteristics

Next, we tested the effects of trauma characteristics (re-exposure, interpersonal vs. non-interpersonal) on our models using multiple groups modeling. In our first test, the nested model test revealed that paths were invariant across trauma re-exposure status for both years of the study: for Y1 to Y2 (n=371 without re-exposure, n=352 with re-exposure), Δ χ2 (23) = 18.06, p=.75; for Y2 to Y3 (n=445 without re-exposure, n=244 with re-exposure), Δ χ2 (26) = 33.31, p=.15. Paths also were invariant across baseline trauma type (n=399 interpersonal, n=333 non-interpersonal), Δ χ2 (49) = 56.84, p=.21.

Gender

Finally, we tested our models for gender invariance. We found no evidence for gender differences in these models; the nested model test indicated that the path coefficients did not vary across sex (n=535 women, n=197 men), Δ χ2 (49) = 58.06, p=.18.

Discussion

With this study, we sought to understand both unidirectional and bidirectional associations among coping, PTSD, and alcohol involvement in a sample of trauma-exposed young adults as they entered college, and to test potential moderators of these associations. Several interesting findings regarding these pathways emerged. First, with regard to reciprocal paths, our data show a process of mutual influence between PTSD symptoms and negative coping. PTSD symptoms at matriculation predicted increased negative coping in Y2, which then predicted increases in PTSD symptoms in Y3. Similarly, negative coping at Y1 predicted later increases in PTSD symptoms; however, the effect from Y2 PTSD symptoms to Y3 negative coping did not meet conventional criteria for statistical significance. These patterns of reciprocity are consistent with learning models of PTSD outlined by Foa and others (Foa & Kozak, 1986; Syder & Pulver, 2001) and tested in a small body of empirical work (e.g. Badour et al., 2012; Littleton et al., 2011). In these models, maladaptive coping approaches are shaped by the experience of PTSD symptoms, and then these coping approaches further contribute to the development and maintenance of PTSD symptoms. Further, these associations appear to be consistent across gender, and independent of whether re-victimization had occurred during the assessment period, and whether the trauma related to PTSD symptoms was interpersonal in nature. In this study, we examined a longer time frame than has been examined previously, demonstrating that these reciprocal influences can be far-reaching.

In contrast, we saw no evidence of reciprocal associations between PTSD symptoms and positive coping. Whereas some studies have found positive coping to buffer against the development or worsening of PTSD symptoms (Schuettler & Boals, 2011; Gerber, Boals, & Schuettler, 2011; Moore et al., 2010; Wang et al., 2013), we did not observe such a buffering effect. PTSD also did not appear to exert a deleterious effect on positive coping, as might be expected. One possible reason for this is that the PTSD symptoms students reported at matriculation were based on lifetime trauma exposure and thus, these symptoms may have been going on for some time prior to college entry. As such, students may have had time to develop strong and relatively robust positive coping strategies that allowed them to manage these symptoms to function in the college environment. Though a large literature has examined the influence of coping (particularly negative coping) on alcohol outcomes, there has been very little examination of how problem drinking may influence coping approaches. This is a contribution of the present study.

One of the objectives of this study was to examine the possible intervening role that negative coping plays in the course of PTSD symptoms and alcohol consequences. Our findings shed light on this pathway. Alcohol consequences reported at the start of the first college year were associated (albeit, marginally) with increased negative coping at the beginning of the second college year, which in turn was associated with increased PTSD symptoms a year later. A prospective effect for the hypothesized path from Y2 alcohol consequences to Y3 negative coping was observed, but fell just below the statistical significance criterion. The associations between alcohol consequences and PTSD symptoms are particularly notable given that they were observed after controlling for stability in coping and PTSD symptoms, and could be seen over a fairly long period of assessment. Our indirect pathway findings suggest that trauma-exposed students who enter college with high levels of alcohol-related consequences are at risk for the development of maladaptive coping strategies that may contribute to harmful psychological outcomes, including posttraumatic stress, months and even years down the road.

We did not find a similar mediated path in the prospective association between baseline PTSD symptoms and alcohol problem outcomes in Year 3. This may have been a function of the length of time between our assessments. Indeed, in our own and other work, self-medication associations between PTSD and drinking outcomes are most evident when assessed more closely together in time, or when dynamic changes in PTSD or drinking behaviors are explicitly modeled (Breslau, Davis, & Schultz, 2003; Kaysen et al., 2013; Read, Wardell, & Colder, 2013; Read, Brown, & Kahler, 2004; Read et al., 2012). This suggests that problem drinking in response to PTSD symptoms tends to be temporally acute, rather than chronic. As such, self-medication pathways – even indirect ones – are less likely to be observed across longer time periods.

In this study, we examined reciprocal associations among PTSD, coping, and alcohol use and consequences. This allowed us to examine unique associations among these variables, and specifically to examine pathways to and from alcohol consequences, isolating these effects from those attributable to alcohol consumption. Notably, only alcohol consequences showed a significant prospective influence in our model (i.e., the indirect association between Y1 alcohol consequences and Y3 PTSD symptoms via Y2 negative coping). Alcohol use was not prospectively associated with coping or with PTSD in our analyses. This is consistent with a large literature that suggests that the negative affect drinking pathway is one that is relevant to problem drinking and alcohol consequences, rather than just alcohol consumption (Carey & Correia, 1997; Cooper, Frone, Russell, & Mudar, 1995; Kuntsche et al., 2005; Merrill & Read, 2010).

Consistent with prior work, rates of re-exposure in this sample were quite high, with approximately half of those who entered college with a criterion A trauma reporting trauma re-exposure at some point during the two years that followed. Similarly, more than half of the sample reported exposure to interpersonal trauma. Yet despite the ubiquity of these potentially harmful trauma characteristics in this sample, these did not moderate the observed PTSD-coping-alcohol pathways. Moreover, despite gender difference that we observed both in rates of interpersonal traumas, and likelihood of re-victimization, our models showed evidence of gender invariance, suggesting that these associations play out similarly for men and women.

Limitations and Future Directions

This study had limitations, many of which point to directions for future research. To begin with, it was the objective of this study to examine the role of coping in the course of PTSD and alcohol consequences over an extended period of time. Accordingly, our assessments were spaced approximately one year apart. As noted above, it will be interesting to see whether these associations differ when examined over shorter periods. Over the last several years, a number of studies have used methods such as ecological momentary assessment to examine PTSD-alcohol associations at the daily or weekly level (e.g., Bisby et al., 2009; Simpson et al., 2012). Extending the use of these methods to include coping will be an interesting direction for future research, and may shed blight on some of the shorter-term processes in these associations.

Further, in this study we focused on PTSD-alcohol-coping associations at the transition into college. It is important to bear in mind that associations observed here may not necessarily reflect associations for individuals at other developmental junctures and life stages. Replication of this work with younger adolescents and older adults is needed in order to understand how and for whom PTSD-alcohol associations unfold across the lifespan. In addition, it also will be interesting to apply models such as those that we examined here to other substances such as nicotine or illicit drugs to determine whether these pathways generalize to other drugs.

In this study we provide an empirical test of theorized prospective models of association among PTSD, alcohol outcomes, and coping that seldom have been tested in the literature. Yet, it is important to bear in mind that the effect sizes that we observed for the structural paths, though statistically significant and of potential theoretical relevance, nonetheless were small. As such, conclusions regarding clinical implications of these findings should be drawn with caution.

Finally, in this study we are not able to rule out possible third-variable explanations for the associations that were observed. For example, though we can ascertain from this study that alcohol consequences at one time point are significantly linked to negative coping at a later time point, we do not know whether or to what extent this association may be driven by other factors (e.g., changes in peer networks or social support, other life stressors) not included in the model. Moving forward, the inclusion of additional, theoretically relevant influences on PTSD-coping-alcohol associations will broaden our understanding of these pathways.

Conclusions

A large literature has highlighted the developmental significance of the transition into college, underscoring this as a time during which risk for longer-term negative outcomes can be identified and intervened on. Findings from the present study point to risk that is conferred by both PTSD and alcohol consequences for negative coping, and through this (at least for the path from alcohol consequences), for posttraumatic stress. Interventions designed to decrease negative coping may help to offset this risk, leading to more positive outcomes for the large number of students who enter college with a history of trauma.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01DA018993) to Dr. Jennifer P. Read.

We would like to thank Drs. Jennifer E. Merrill, Sherry Farrow, Craig Colder, Ashlyn Swartout, Jackie White and the members of the UB Alcohol Research Lab for their many efforts to support data collection for this study. We also would like to thank the participants for sharing their experiences.

Footnotes

Footnote

It is not possible to request more decimal places for the confidence intervals in MPLUS output, so we report the lower boundary of the CI as <.001. Accordingly, we applied a method to verify that the lower boundary of the confidence interval was indeed greater than zero and was not exactly zero or rounded up from a value slightly less than zero. This method, recommended by the developer of MPLUS, involves rescaling the variables in the model by a constant so that the decimal places will be shifted for the estimates of the indirect associations and confidence intervals. Using this method leads to the conclusion that our 95% CI does not contain zero.

The TLEQ was used with permission from WPS. WPS, 12031 Wilshire Boulevard, Los Angeles, California 90025, U.S.A, Format adapted by J. Read, SUNY at Buffalo,

References

- Andrykowski MA, Cordova MJ, Studts JL, Miller TW. Posttraumatic stress disorder after treatment for breast cancer: Prevalence of diagnosis and use of the PTSD Checklist—Civilian Version (PCL—C) as a screening instrument. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66:586–590. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.66.3.586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arria AM, Vincent KB, Caldeira KM. Measuring liability for substance use disorder among college students: Implications for screening and early intervention. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 2009;35:233–241. doi: 10.1080/00952990903005957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachrach RL, Read JP. The role of posttraumatic stress and problem alcohol involvement in university academic performance. Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2012;68:843–859. doi: 10.1002/jclp.21874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badour CL, Blonigen DM, Boden MT, Feldner MT, Bonn-Miller MO. A longitudinal test of the bi-directional relations between avoidance coping and PTSD severity during and after PTSD treatment. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2012;50:610–616. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2012.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisby JA, Brewin CR, Leitz JR, Curran HV. Acute effects of alcohol on the development of intrusive memories. Psychopharmacology. 2009;204:655–666. doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1496-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blake DD, Weathers FW, Nagy LM, Kaloupek DG, Gusman FD, Charney DS, Keane TM. The development of a clinician-administered PTSD scale. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1995;8:75–90. doi: 10.1002/jts.2490080106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard EB, Jones-Alexander J, Buckley TC, Forneris CA. Psychometric properties of the PTSD Checklist (PCL) Behavior Research and Therapy. 1996;34:669–673. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(96)00033-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornovalova MA, Ouimette P, Crawford AV, Levy R. Testing gender effects on the mechanisms explaining the association between post-traumatic stress symptoms and substance use frequency. Addictive Behaviors. 2009;34:685–692. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N, Davis GC. Posttraumatic stress disorder in an urban population of young adults: Risk factors and chronicity. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 1992;149:671–675. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(93)90009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N, Davis GC, Schultz LR. Posttraumatic stress disorder and the incidence of nicotine, alcohol, and other drug disorders in persons who have experienced trauma. Archives of general psychiatry. 2003;60(3):289–294. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.3.289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briere J, Runtz M. Post sexual abuse trauma data and implications for clinical practice. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 1987;2:367–379. doi: 10.1177/088626058700200403. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brown PJ, Read JP, Kahler CW. Comorbid posttraumatic stress disorder and substance use disorders: Treatment outcomes and the role of coping. In: Ouimette Paige, Brown Pamela J., editors. Trauma and substance abuse: Causes, consequences, and treatment of comorbid disorders. Washington, DC, US: American Psychological Association; 2003. pp. 171–188. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carey KB, Correia CJ. Drinking motives predict alcohol related problems in college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 1997;58:100–105. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1997.58.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS. You want to measure coping but your protocol’s too long: Consider the Brief COPE. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 1997;4:92–100. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm0401_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS, Scheier MF, Weintraub JK, Jagdish K. Assessing coping strategies: a theoretically based approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1989;56:267. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.56.2.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chilcoat HD, Breslau N. Investigations of causal pathways between PTSD and drug use disorders. Addictive Behaviors. 1998;23:827–840. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.10.913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung H, Breslau N. The latent structure of post-traumatic stress disorder: tests of invariance by gender and trauma type. Psychological Medicine. 2008;38(4):563–574. doi: 10.1017/S0033291707002589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins LR, Parks GA, Marlatt GA. Social determinants of alcohol consumption: The effects of social interaction and model status on the self-administration of alcohol. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1985;53:189–200. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.53.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Russell M, Skinner JB, Frone MR, Mudar P. Stress and alcohol use: Moderating effects of gender, coping, and alcohol expectancies. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1992;101:139–152. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.101.1.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper ML, Frone MR, Russell M, Mudar P. Drinking to regulate positive and negative emotions: A motivational model of alcohol use. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;69:990–1005. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.69.5.990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corbin WR, Farmer NM, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Relations among stress, coping strategies, coping motives, alcohol consumption and related problems: A mediated moderation model. Addictive Behaviors. 2013;38:1912–1919. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crawford JR, Henry JD. The Depression Anxiety Stress Scales: Normative data and latent structure in a large non-clinical sample. British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2003;42:111–131. doi: 10.1348/014466503321903544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson DA, Grant BF, Stinson FS, Chou PS. Another look at heavy episodic drinking and alcohol use disorders among college and non-college youth. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2004;65:477–488. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.477. DOI not available. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dermody SS, Chong J, Manuck S. An evaluation of the stress-negative affect model in explaining alcohol use: The role of components of negative affect and coping style. Substance Use & Misuse. 2013;48:297–308. doi: 10.3109/10826084.2012.761713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan R. Childhood maltreatment and college drop-out rates: Implications for child abuse. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2000;15:987–995. doi: 10.1177/088626000015009005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers A, Clark D. A cognitive model of posttraumatic stress disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2000;38:319–345. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(99)00123-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elhai JD, Simons JS. Trauma exposure and posttraumatic stress disorder predictors of mental health treatment use in college students. Psychological Services. 2007;4:38–45. doi: 10.1037/1541-1559.4.1.38. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Enders CK. Applied missing data analysis. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Falsetti SA, Resnick H. Treatment of PTSD using cognitive and cognitive behavioral therapies. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2000;14:261–285. [Google Scholar]

- Fisher BS, Cullen FT, Turner MG. The sexual victimization of college women. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice, National Institute of Justice and Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Flood Amanda M, McDevitt-Murphy Meghan E, Weathers Frank W, Eakin David E, Benson Trisha A. Substance use behaviors as a mediator between posttraumatic stress disorder and physical health in trauma-exposed college students. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2009;32:234–243. doi: 10.1007/s10865-008-9195-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Kozak MJ. Emotional processing of fear: Exposure to corrective information. Psychological Bulletin. 1986;99:20–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes D, Fletcher S, Parslow R, Phelps A, O’Donnell M, Bryant RA, Creamer M. Trauma at the hands of another: longitudinal study of differences in the posttraumatic stress disorder symptom profile following interpersonal compared with noninterpersonal trauma. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2012;73:372–376. doi: 10.4088/JCP.10m06640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes D, Fletcher S, Parslow R, Phelps A, O’Donnell M, Bryant RA, Creamer M. Trauma at the hands of another: longitudinal study of differences in the posttraumatic stress disorder symptom profile following interpersonal compared with noninterpersonal trauma. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2012;73:372–376. doi: 10.1037/1541-1559.4.1.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford JD, Elhai JD, Connor DF, Frueh BC. Poly-victimization and risk of posttraumatic, depressive, and substance use disorders and involvement in delinquency in a national sample of adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2010;46:545–552. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.11.212. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.11.212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fromme K, Corbin W, Kruse M. Behavioral risks during the transition from high school to college. Developmental Psychology. 2008;44:1497–1504. doi: 10.1037/a0012614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerber MM, Boals A, Schuettler D. The unique contributions of positive and negative religious coping to posttraumatic growth and PTSD. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality. 2011;3:298–307. doi: 10.1037/a0023016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Giaconia RM, Reinherz HZ, Hauf AC, Paradis AD, Wasserman MS, Langhammer DM. Comorbidity of Substance Use and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorders in a Community Sample of Adolescents. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2000;70(2):253–262. doi: 10.1037/h0087634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilts Chelsea D, Parker Patricia A, Pettaway Curtis A, Cohen Lorenzo. Psychosocial moderators of presurgical stress management for men undergoing radical prostatectomy. Health Psychology. 2012 doi: 10.1037/a0030189. Advance online publication: 10.1037/a0030189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green BL, Krupnick JL, Stockton P, Goodman L, Corcoran C, Petty R. Effects of adolescent trauma exposure on risky behavior in college women. Psychiatry: Interpersonal and Biological Processes. 2005;68:363–378. doi: 10.1521/psyc.2005.68.4.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haller M, Chassin L. The influence of PTSD symptoms on alcohol and drug problems: Internalizing and externalizing pathways. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2012;5:484–489. doi: 10.1037/a0029335. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson RF, Kilpatrick DG, Falsetti SA, Resnick HS. Violent crime and mental health. In: Freedy JR, Hobfoll SE, editors. Traumatic stress: From theory to practice. New York, NY US: Plenum Press; 1997. pp. 129–161. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll SE. Conservation of resources: A new attempt at conceptualizing stress. American Psychologist. 1989;44:513–524. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.44.3.513.v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoyle RH, editor. Structural equation modeling: Concepts, issues, and applications. Sage Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Hruska B, Delahanty DL. Application of the stressor vulnerability model to understanding posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and alcohol-related problems in an undergraduate population. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2012;26:734–746. doi: 10.1037/a0027584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Humphrey JA, White JW. Women’s vulnerability to sexual assault from adolescence to young adulthood. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2000;27:419–424. doi: 10.1016/S1054-139X(00)00168-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hur YM, MacGregor AJ, Cherkas LW, Frances MK, Spector TD. Age differences in genetic and environmental variations in stress-coping during adulthood: A study of female twins. Behavior Genetics. 2012;42:541–548. doi: 10.1007/s10519-012-9541-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaltman S, Krupnick J, Stockton P, Hooper L, Green BL. Psychological impact of types of sexual trauma among college women. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2005;18:547–555. doi: 10.1002/jts.20063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaysen D, Atkins DC, Simpson TL, Stappenbeck CA, Blayney JA, Lee CM, Larimer ME. Proximal Relationships Between PTSD Symptoms and Drinking Among Female College Students: Results From a Daily Monitoring Study. 2013 doi: 10.1037/a0033588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA. Encyclopedia of Statistics in Behavioral Science. Wiley & Sons LTD; 2005. Cross-Lagged Panel Design. [Google Scholar]

- Khantzian EJ. The self-medication hypothesis revisited: The dually diagnosed patient. Primary Psychiatry. 2003;10:47–48. [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. 2. New York, NY, US: Guilford Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kubany ES, Haynes SY, Leisen MB, Owens JA, Kaplan AS, Watson SB, Burns K. Development and preliminary validation of a brief broad-spectrum measure of trauma exposure: The Traumatic Life Events Questionnaire. Psychological Assessment. 2000;12:210–224. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.12.2.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuntsche E, Knibbe RA, Gmel G, Engels RCME. Why do young people drink? A review of drinking motives. Clinical Psychology Review. 2005;25:841–61. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang A, Laffaye C, Satz L, Dresselhaus T, Stein M. Sensitivity and specificity of the PTSD Checklist in detecting PTSD in female veterans in primary care. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2003;16:257–264. doi: 10.1023/A:1023796007788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauterbach D, Vrana S. The relationship among personality variables, exposure to traumatic events, and severity of posttraumatic stress symptoms. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2001;14:29–45. doi: 10.1023/A:1007831430706. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, appraisal, and coping. Springer Publishing Company; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Lehavot K, Stappenbeck CA, Luterek JA, Kaysen D, Simpson TL. Gender differences in relationships among PTSD severity, drinking motives, and alcohol use in a comorbid alcohol dependence and PTSD sample. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2014;28:42–52. doi: 10.1037/a0032266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis MA, Neighbors C, Oster-Aaland L, Kirkeby BS, Larimer ME. Indicated prevention for incoming freshmen: Personalized normative feedback and high-risk drinking. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:2495–2508. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lilly MM, Valdez CE. Interpersonal trauma and PTSD: The roles of gender and a lifespan perspective in predicting risk. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2012;4:140. doi: 10.1037/a0022947. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Littleton H, Axsom D, Grills-Taquechel AE. Longitudinal evaluation of the relationship between maladaptive trauma coping and distress: Examination following the mass shooting at Virginia Tech. Anxiety, Stress & Coping: An International Journal. 2011;24:273–290. doi: 10.1080/10615806.2010.500722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littman JA. The COPE inventory: Dimensionality and relationships with approach- and avoidance- motives and positive and negative traits. Personality and Individual Differences. 2006;41:273–284. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2005.11.032. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marx BP, Sloan DM. The effects of trauma history, gender, and race on alcohol use and posttraumatic stress symptoms in a college student sample. Addictive Behaviors. 2003;28:1631–1647. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2003.08.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe SE, West BT, Wechsler H. Alcohol use disorders and non-medical use of prescription drugs among U.S. college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs. 2007;68:543–547. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01733.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarlane AC, Browne D, Bryant RA, O’Donnell M, Silove D, Creamer M, Horsley K. A longitudinal analysis of alcohol consumption and the risk of posttraumatic symptoms. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2009;118:166–172. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDevitt-Murphy ME, Weathers FW, Flood AM, Eakin DE, Benson TA. The utility of the PAI and the MMPI-2 for discriminating PTSD, depression, and social phobia in trauma-exposed college students. Assessment. 2007;14:181–195. doi: 10.1177/1073191106295914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDevitt-Murphy Meghan E. Significant other enhanced cognitive-behavioral therapy for PTSD and alcohol misuse in OEF/OIF veterans. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 42:40–46. doi: 10.1037/a0022346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menaghan EG. Individual coping efforts and family studies: Conceptual and methodological issues. Marriage & Family Review. 1983;6:113–135. doi: 10.1300/J002v06n01_06. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Merrill JE, Read JP. Motivational pathways to unique types of alcohol consequences. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2010;24:705–11. doi: 10.1037/a0020135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Messman-Moore TL, Brown AL. Child maltreatment and perceived family environment as risk factors for adult rape: Is child sexual abuse the most salient experience? Child Abuse & Neglect. 2004;28:1019–1034. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer B. Coping with severe mental illness: Relations of the Brief COPE with symptoms, functioning, and well-being. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 2001;23:265–277. doi: 10.1023/A:1012731520781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Wilbourne PL, Hettema JE. What works? A summary of alcohol treatment outcome research. In: Hester RK, Miller WR, editors. Handbook of Alcoholism Treatment Approaches: Effective Alternatives. 3. New York: Guilford Press; 2003. pp. 13–64. [Google Scholar]

- Miyazaki Yasuo, Bodenhorn Nancy, Zalaquett Carlos, Ng Kok-Mun. Factorial structure of the brief cope for international students attending U.S. colleges. College Student Journal. 2008;42:795–806. [Google Scholar]

- Moore SA, Varra AA, Michael ST, Simpson TL. Stress-related growth, positive reframing, and emotional processing in the prediction of post-trauma functioning among veterans in mental health treatment. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2010;2:93–96. doi: 10.1037/a0018975. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moos RH. The Coping Responses Inventory: A measure of approach and avoidance coping skills. In: Zalaquett CP, Wood RJ, editors. Evaluating stress: A book of resources. Lanham, MD: US Scarecros Education; 1997. pp. 51–65. [Google Scholar]

- Moos RH, Holahan CJ. Dispositional and contextual perspectives on coping: Toward an integrative framework. Journal of clinical psychology. 2003;59(12):1387–1403. doi: 10.1002/jclp.10229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moos RH, Moos BS. Rates and predictors of relapse after natural and treated remission from alcohol use disorders. Addiction. 2006;101:212–222. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01310.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide. Vol. 6. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Mylle J, Maes M. Partial posttraumatic stress disorder revisited. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2004;78(02):37–48. 00218–5. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neighbors CL, Geisner IM, Lee CM. Perceived marijuana norms and social expectancies among entering college student marijuana users. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2008;22:433–438. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.22.3.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norris FH. Epidemiology of trauma: Frequency and impact of different potentially traumatic events on different demographic groups. Journal of Counseling and Clinical Psychology. 1992;60:409–418. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.60.3.409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Malley PM, Johnston LD. Epidemiology of alcohol and other drug use among American college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2002;14:23–39. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ouimette PC, Ahrens C, Moos RH, Finney JW. Posttraumatic stress disorder in substance abuse patients: Relationship to 1-year posttreatment outcomes. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1997;11:34–47. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.11.1.34. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ouimette PC, Finney JW, Moos RH. Two-year posttreatment functioning and coping of substance abuse patients with posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1999;13:105–114. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.13.2.105. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Park CL, Armeli S, Tennen H. The daily stress and coping process and alcohol use among college students. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2004;65:126–135. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2004.65.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rich CL, Gidycz CA, Warkentin JB, Loh C, Weiland P. Child and adolescent abuse and subsequent victimization: A prospective study. Child abuse & neglect. 2005;29:1373–1394. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2005.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read JP, Brown PJ, Kahler CW. Substance Use and Post-traumatic stress disorder: Symptom interplay and effects on outcome. Addictive Behaviors. 2004;29:1665–1672. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.02.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read JP, Colder CR, Merrill JE, Ouimette P, White J, Swartout A. Trauma and posttraumatic stress symptoms influence alcohol and other drug problem trajectories in the first year of college. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2012;80:426–439. doi: 10.1037/a0028210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read JP, Kahler CW, Strong D, Colder CR. Development and preliminary validation of the Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire. Journal of Studies on Alcohol. 2006;67:169–178. doi: 10.15288/jsa.2006.67.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read JP, Merrill J, Kahler CW, Strong DS. Predicting Functional Outcomes Among College Drinkers: Reliability and Predictive Validity of the Young Adult Alcohol Consequences Questionnaire. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:2597–2610. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.06.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read JP, Ouimette P, White J, Colder C, Farrow S. Rates of DSM IV-TR trauma exposure and posttraumatic stress disorder among newly matriculated college students. Trauma: Theory, Research, and Practice. 2011;3:148–156. doi: 10.1037/a0021260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read JP, Wardell JD, Colder CR. Reciprocal associations between PTSD symptoms and alcohol involvement in college: A three-year trait-state-error analysis. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2013;122:984–997. doi: 10.1037/a0034918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read JP, Wardell JD, Vermont L, Colder CR, Ouimette P, White JJ. Transition and change: The prospective effects of posttraumatic stress on smoking trajectories in the first year of college. Health Psychology. 2013;32:757–767. doi: 10.1037/a0029085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roodman AA, Clum GA. Revictimization rates and method variance: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review. 2001;21(99):183–204. 00045–8. doi: 10.1016/S0272-7358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saladin ME, Brady KT, Dansky BS, Kilpatrick DG. Understanding comorbidity between PTSD and substance use disorders: Two preliminary investigations. Addictive Behaviors. 1995;20:643–655. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(95)00024-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satorra A, Bentler PM. A scaled difference chi-square test statistic for moment structure analysis. Psychometrika. 2001;66:507–514. doi: 10.1007/BF02296192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnider Kimberly R, Elhai Jon D, Gray Matt J. Coping style use predicts posttraumatic stress and complicated grief symptom severity among college students reporting a traumatic loss. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2007;54:344–350. doi: 10.1037/0022-0167.54.3.344. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schnurr PP, Ford JD, Friedman MJ, Green BL, Dain BJ, Sengupta A. Predictors and outcomes of posttraumatic stress disorder in World War II veterans exposed to mustard gas. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:258–268. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.68.2.258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuettler D, Boals A. The path to posttraumatic growth versus posttraumatic stress disorder: Contributions of event centrality and coping. Journal of Loss and Trauma. 2011;16:180–194. doi: 10.1080/15325024.2010.519273. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shipherd JC, Stafford J, Tanner LR. Predicting alcohol and drug abuse in Persian Gulf War veterans: What role do PTSD symptoms play? Addictive Behaviors. 2005;30:595–599. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2004.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson TL, Stappenbeck CA, Varra AA, Moore SA, Kaysen D. Symptoms of posttraumatic stress predict craving among alcohol treatment seekers: Results of a daily monitoring study. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2012;26:724–733. doi: 10.1037/a0027169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyth JM, Hockemeyer JR, Heron KE, Wonderlich SE, Pennebaker JW. Prevalence, type, disclosure, and severity of adverse life events in college students. Journal of American College Health. 2008;57:69–76. doi: 10.3200/JACH.57.1.69-76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snell Deborah L, Siegert Richard J, Hay-Smith E Jean C, Surgenor Lois J. Associations between illness perceptions, coping styles and outcome after mild traumatic brain injury: Preliminary results from a cohort study. Brain Injury. 2011;25:1126–1138. doi: 10.3109/02699052.2011.607786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snyder CR, Pulvers KM. Copers coping with stress: Two against one. In: Snyder CR, editor. Coping with stress: Effective people and processes. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2001. pp. 285–301. [Google Scholar]

- Sonne SC, Back SE, Zuniga CD, Randall CL, Brady KT. Gender differences in individuals with comorbid alcohol dependence and posttraumatic stress disorder. The American Journal on Addictions. 2003;12:412–423. doi: 10.1080/10550490390240783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staiger PK, Melville F, Hides L, Kambouropoulos N, Lubman DI. Can emotion-focused coping help explain the link between posttraumatic stress disorder severity and triggers for substance use in young adults? Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2009;36:220–226. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2008.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]