Abstract

Background

Prenatal air pollution exposure inhibits fetal growth, but implications for postnatal growth are unknown.

Methods

We assessed weights and lengths of US infants in the Project Viva cohort at birth and 6 months. We estimated third-trimester residential air pollution exposures using spatiotemporal models. We estimated neighborhood traffic density and roadway proximity at birth address using geographic information systems. We performed linear and logistic regression adjusted for sociodemographic variables, fetal growth, and gestational age at birth.

Results

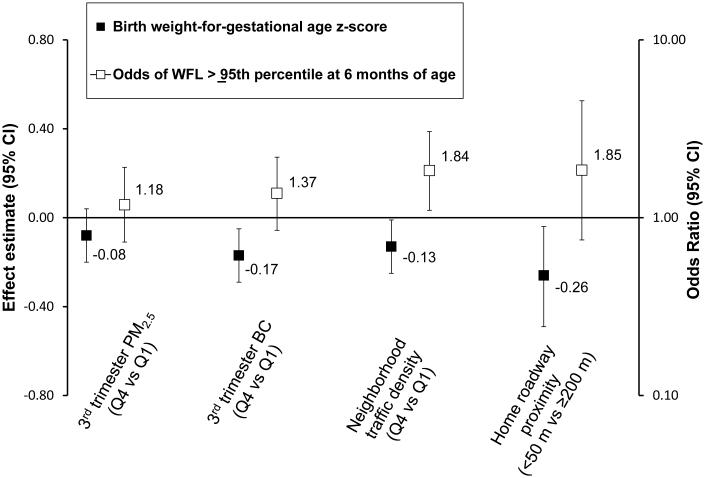

Mean birth weight-for-gestational age z-score (fetal growth) was 0.17 (SD = 0.97; n=2,114), 0-6 month weight-for-length gain was 0.23 z-units (SD = 1.11; n=689), and 17% had weight-for-length ≥95th percentile at 6 months of age. Infants exposed to the highest (vs. lowest) quartile of neighborhood traffic density had lower fetal growth (−0.13 units [95% confidence interval (CI) = −0.25 to −0.01]), more rapid 0-6 month weight-for-length gain (0.25 units [95% CI = 0.01 to 0.49]), and higher odds of weight-for-length ≥95th percentile at 6 months (1.84 [95% CI = 1.11 to 3.05]). Neighborhood traffic density was additionally associated with an infant being in both the lowest quartile of fetal growth and highest quartile of 0-6 month weight-for-length gain (Q4 vs. Q1, OR = 3.01 [95% CI = 1.08 to 8.44]). Roadway proximity and third-trimester black carbon exposure were similarly associated with growth outcomes. For third-trimester PM2.5, effect estimates were in the same direction, but smaller and imprecise.

Conclusions

Infants exposed to higher traffic-related pollution in early life may exhibit more rapid postnatal weight gain in addition to reduced fetal growth.

Many studies have found associations of particulate and gaseous air pollution during late pregnancy with reduced measures of fetal growth at birth.1, 2 Pollution components of particle mass with an aerodynamic diameter of less than 2.5 μm (PM2.5) readily enter the lower airways and have been hypothesized to adversely influence fetal growth and development by inducing maternal oxidative stress, blood coagulation, vascular dysfunction, or inflammation, potentially inhibiting nutrient transfer from mother to fetus.3

Indirect evidence also suggests that air pollution exposure may promote obesity after birth. Prenatal exposure to tobacco smoke4 (a complex mix of particulate matter, gases and toxins) and to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons5 (a combustion byproduct of fossil fuel and biomass burning with hormonal properties) have both been associated with increased odds of childhood obesity. In rodent models, adult mice developed visceral adipocyte hypertrophy and increased central adiposity following long-term postnatal exposure to fine particulate matter.6 Reduced fetal growth and development of childhood obesity may have common mechanistic origins during the prenatal period.7 Also, the phenotype of reduced fetal growth followed by greater weight gain during infancy predicts cardiovascular disease risk later in life.8, 9 However, whether exposure to fine particulate matter during late pregnancy increases risk for childhood obesity in addition to reduced fetal growth is unknown.

In the present analysis of a large cohort of women and their offspring residing in the greater Boston area, our objective was to evaluate the extent to which neighborhood traffic density, home roadway proximity, and third-trimester exposures to PM2.5 and black carbon (a traffic-related component of PM2.5) were associated with fetal growth at birth, weight gain from 0 to 6 months of age, and the phenotype of reduced fetal growth and rapid infant weight gain. We hypothesized that prenatal air pollution exposure would be associated with both reduced fetal growth and greater postnatal weight gain.

METHODS

Study population and design

Study subjects were participants in Project Viva, a prospective observational cohort study of prenatal exposures, pregnancy outcomes, and offspring health. We recruited women during their first prenatal visit at Harvard Vanguard Medical Associates, a multi-specialty group practice in eastern Massachusetts. Details of recruitment procedures and study protocol have been previously published.10 Of 2,128 Project Viva participants with a live singleton offspring, 2,115 had data available for at least one exposure and one outcome studied here. We included a subset in each analysis based primarily on the number with outcome data available. Of 2,114 infants who had a birth weight-for-gestational age z-score, 1,175 attended a 6 month follow-up visit. Of those, weight and length were measured in 1,172 at 6 months; 689 also had a measure of length at birth. The sample size for analyses of fetal growth ranged from 1,838 to 2,083, 0-6 month weight-for-length gain from 617 to 684, and weight-for-length ≥95th percentile at 6 months from 1,030 to 1,143. Mothers of infants with (vs. without) a 6-month follow-up visit were more likely to have a lower pre-pregnancy BMI and to be white, older, educated, higher income, and non-smokers. Infants of these mothers had higher birth weight-for-gestational age z-score and longer gestation (eTable 1). Research measures of newborn length were missing primarily in infants who were born prematurely or on weekends or who were discharged home rapidly. Infants with (vs. without) a newborn length recorded had a higher birth weight-for-gestational age z-score and gestational age (data not shown).

Participants provided their residential address at enrollment and updated it at study visits that occurred at the end of the second trimester, soon after birth, and at 6 months postpartum. We included in analyses of air pollution exposures mother/infant pairs who lived at an address in our catchment area for at least 75% of each exposure time period.

Mothers provided written informed consent at enrollment and for their infants after birth, and Institutional Review Boards of the participating sites approved the study.

Assessment of participant characteristics

Using a combination of interviews and self-administered questionnaires, we collected information at study enrollment (median 9.9 weeks gestation) on mothers’ age, race/ethnicity, education, household income, smoking habits, and date of last menstrual period (LMP). We calculated mothers’ pre-pregnancy BMI from self-reported weight and height. We calculated total gestational weight gain as the difference between self-reported pre-pregnancy weight and the last weight recorded before delivery. At the end of the second trimester (median 28.1 weeks), women underwent a two-tiered (50 g non-fasting followed by 100 g fasting if abnormal) glucose screening test; we grouped these results into 4 categories of glucose tolerance, as previously described.11

Air pollution exposures

We estimated daily black carbon exposure at each residential address using a validated spatiotemporal land-use regression model (mean “out-of-sample” R2 was 0.73).12, 13 We modeled daily PM2.5 exposure at each residence using aerosol optical depth data (mean “out-of-sample” R2 was 0.87 for days with this information and 0.85 for days without).14 These models accounted for any moves during or after pregnancy. To obtain third-trimester exposure estimates, we averaged daily exposures from the 188th day after LMP to the day before birth.

While our daily estimates of PM2.5 and black carbon were temporally as well as spatially resolved, neighborhood traffic density and residential distance to roadway estimates were spatially resolved only. We used the 2002 road inventory from the Massachusetts Executive Office of Transportation to estimate traffic density and 2005 ESRI Street MapTM North America ArcGIS 10 Data and Maps to estimate roadway proximity. Neighborhood traffic density varied across and within road types and was calculated using the annual average of daily traffic (vehicles/day) multiplied by the length of road (km) within 100 m of the geocoded location of the participants’ residential address at the time of delivery. Home roadway proximity was calculated as distance to Census Feature Class Code A1 or A2 roads.

Assessment of fetal and postnatal growth

We obtained infant birth weight in grams and date of delivery from the hospital medical record. We calculated length of gestation in days by subtracting the date of the LMP from the date of delivery. If gestational age according to the second trimester ultrasound differed from that according to the LMP by more than 10 days, we used the ultrasound result to determine gestational duration. We determined birth weight-for-gestational age and sex z-score from a US national reference.15

Trained research assistants weighed infants at 6 months with a digital scale (Seca Model 881; Seca Corporation, Hamburg, Germany) and measured length at birth and 6 months with a Shorr measuring board (Shorr Productions, Olney, Maryland). We calculated age- and sex-specific weight-for-length z-score from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) 2000 growth chart data16 at birth and at 6 months.

Statistical analyses

We used linear regression to evaluate associations of air pollution exposures with birth weight-for-gestational age z-score and with change in weight-for-length z-score from 0 to 6 months of age. Both outcomes were normally distributed. We used logistic regression to evaluate the associations of air pollution exposures with weight-for-length ≥95th percentile at 6 months of age.

Because the traffic density and distance to roadway exposure metrics were not temporally resolved, we restricted analyses using traffic density and distance to roadway exposures to the 90% of participants who did not move during pregnancy for analyses of fetal growth and to the 85% of participants who did not move either during pregnancy or the first 6 months postpartum for analyses of infant weight gain. We a priori categorized proximity to major roadway as ≥ 200 m, 100 m to < 200 m, 50 m to < 100 m, and <50 m to account for the exponential spatial decay observed for traffic-related air pollution.17, 18 We considered each of the other exposures in quartiles. We first fit unadjusted models. Next we created a full multivariate model for each of the exposures and outcomes, which included as covariates characteristics know to be associated with infant size and growth – namely, household income (> $70,000 or ≤ $70,000), paternal BMI (continuous), maternal pre-pregnancy BMI (continuous), race/ethnicity (white, black, Asian, Hispanic, other), education (with or without college degree), pregnancy weight gain (continuous), smoking habits (smoked during pregnancy, formerly smoked, never smoked), and abnormal glucose tolerance (four categories11). We considered but did not include variables for maternal age, maternal height, infant sex, breastfeeding duration, season, and long-term time trend, as these were not confounders of the exposure-outcome relationships (i.e. the estimate for the primary exposure changed by <10%) or did not importantly change the results. Finally, we also conducted an analysis to examine the extent to which air pollution exposures were associated with the phenotype of slower fetal growth and more rapid infant weight gain in the same infant. To do this, we created a 4-level outcome of normal fetal growth/normal 0-6 month weight-for-length z-score (reference) vs. lower fetal growth/normal 0-6 month weight-for-length z-score, normal fetal growth/more rapid 0-6 month weight-for-length z-score, or lower fetal growth/more rapid 0-6 month weight-for-length z-score (outcome of interest). We defined lower vs. normal fetal growth as Q1 (vs. Q2-4) and more rapid vs. normal 0-6 month weight-for-length z-score as Q4 (vs. Q1-3). We a priori chose to use quartiles rather than a clinical cut-off (e.g. small-for-gestational age) to maximize the sample size in each quadrant.

In secondary analyses, we examined associations of fetal and infant growth with PM2.5 and black carbon exposure during the first trimester (date of the LMP to the 93rd day after LMP), second trimester (94th day after LMP to the 187th day after LMP), and 0-6 months postpartum (date of birth to the 182nd day after birth). To assess the possibility of spatial confounding, we included spatial covariates (median household income, percent below poverty, and percent college graduate) based on 1999 census tract data19 into the final models.

As is common in large longitudinal studies, many participants were missing data on one or more covariates. We used chained equations to impute missing values. We generated 50 imputed datasets and combined multivariable modeling results (Proc MI ANALYZE) in SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary NC).20

RESULTS

Population characteristics

Mean maternal age was 31.8 (SD = 5.2) years, and pre-pregnancy BMI was 24.9 (SD = 5.6) kg/m2; 67% of women were white, and 65% were college graduates. Mean infant birth weight-for-gestational age z-score was 0.17 (SD = 0.97) units, change in weight-for-length z-score from 0 to 6 months of age was 0.23 (SD = 1.11) units, and 17% had weight-for-length ≥95th percentile at 6 months of age (Table 1). Imputation of covariates had little or no influence on the distribution of participant characteristics (eTable 1).

Table 1.

Characteristicsa of 2,115 Project Viva mother-child pairs overall and by 3rd-trimester black carbon exposure.

|

Ouartiles of 3rd-trimester black carbon

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3rd-trimester black carbon (μg/m3); Mean (SD): |

Total

0.69 (0.24) |

Q1 (lowest)

0.40 (0.09) |

Q2

0.60 (0.04) |

Q3

0.76 (0.05) |

Q4 (highest)

1.01 (0.15) |

|

|

|||||

| Maternal age at enrollment (years) | 31.8 (5.2) | 32.8 | 32.3 | 31.4 | 30.8 |

| Prepregnancy BMI (kg/m2) | 24.9 (5.6) | 24.6 | 24.9 | 24.6 | 25.4 |

| Pregnancy weight gain (kg) | 15.5 (5.7) | 16.2 | 15.3 | 15.1 | 15.5 |

| College graduate; % | 65 | 76 | 66 | 63 | 53 |

| Household income >$70,000/year; % | 58 | 76 | 64 | 49 | 43 |

| Race/ethnicity; % | |||||

| White | 66 | 87 | 71 | 59 | 50 |

| Black | 17 | 5 | 14 | 22 | 25 |

| Hispanic | 7 | 2 | 8 | 7 | 13 |

| Asian | 6 | 4 | 6 | 7 | 6 |

| Other | 4 | 1 | 2 | 6 | 7 |

| Smoking; % | |||||

| Never | 68 | 67 | 68 | 70 | 69 |

| Former | 19 | 24 | 19 | 18 | 16 |

| During pregnancy | 13 | 9 | 13 | 13 | 15 |

| Glucose tolerance; % | |||||

| Normal | 83 | 82 | 81 | 85 | 82 |

| Failed GCT, normal OGTT | 9 | 11 | 9 | 7 | 8 |

| IGT | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 |

| GDM | 6 | 5 | 7 | 5 | 6 |

| Paternal BMI | 26.4 (4.1) | 26.6 | 26.3 | 26.4 | 26.3 |

| Infant gestational age (weeks) | 39.4 (1.9) | 39.5 | 39.4 | 39.5 | 39.5 |

| Birth weight-for-gestational age z-score | 0.17 (0.97) | 0.31 | 0.19 | 0.19 | 0.00 |

| Change in weight-for-length-z 0-6 months | 0.23 (1.11) | 0.15 | 0.24 | 0.19 | 0.33 |

| Weight-for-length ≥95th percentile at 6 months; % | 17 | 15 | 14 | 19 | 19 |

| 3rd-trimester PM2.5 (μg/m3) | 11.7 (1.6) | 11.0 | 11.5 | 12.1 | 12.5 |

| Neighborhood traffic densityb | 1,526 (2,141) | 646 | 1,135 | 1,601 | 2,744 |

| Home distance to roadway (m)c; % | |||||

| ≥ 200 | 88 | 95 | 91 | 86 | 79 |

| 100 - 199 | 6 | 3 | 6 | 6 | 10 |

| 50 - 99 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 5 |

| < 50 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 7 |

Mean (SD), unless otherwise indicated.

Vehicles/day x km of road within 100 m of residential address for participants who did not move during pregnancy

For participants who did not move during pregnancy

Birth weight-for-gestational age z-score n= 2,114; change in weight-for-length z-score 0-6 months, n=689; weight-for-length at 6 months, n=1,153; 3rd-trimester black carbon, n=2,084; 3rd-trimester PM2.5, n=1,839; traffic density, n=1,886; distance to roadway, n=1,895; for all other characteristics, imputed data are shown (n = 2,115). Nonimputed data are available in eTable 1. Abbreviations: GCT: Glucose tolerance test; OGTT: Oral glucose tolerance test; IGT: Impaired glucose tolerance; GDM: Gestational diabetes mellitus

Third-trimester mean black carbon concentration was 0.7 µg/m3 (SD = 0.2; range = 0.1-1.6), a value typical for many US cities (range 0.2-1.9 µg/m3 for 2005-2007).21 Third-trimester mean PM2.5 concentration was 11.7 µg/m3 (SD = 1.6; range = 7.5-16.8). For context, the Environmental Protection Agency standard for annual PM2.5 exposure was 15 µg/m3 at the time. For participants who did not move during pregnancy, mean neighborhood traffic density was 1,526 (SD = 2,141, range = 0-30,860) vehicles/day χ km of road within 100 m of residential address (Table 2); most (88%) lived ≥ 200 m from a major roadway, and few (3%) lived < 50 m from a major roadway. Exposures were moderately correlated (Spearman correlation coefficients = 0.11-0.52) (eTable 2). Mothers who lived at addresses with lower black carbon exposure were somewhat older, more highly educated, had higher household income, and were more likely to be white and nonsmokers (Table 1).

Table 2.

Adjusted associations of air pollution exposure measures with birth weight-for-gestational age z-score (fetal growth), change in weight-for-length z-score from birth to 6 months, and weight-for-length ≥95th percentile at 6 months

| Estimate (95% CI) of fetal growtha | ||||

|

| ||||

| Exposure |

Quartile 1

(lowest)b |

Quartile 2 | Quartile 3 |

Quartile 4

(highest) |

| 3rd-trimester black carbon | −0.03 (−0.15 to 0.08) | 0.03 (−0.09 to 0.14) | −0.17 (−0.29 to −0.05) | |

| 3rd-trimester PM2.5 | −0.02 (−0.14 to 0.10) | 0.03 (−0.09 to 0.15) | −0.08 (−0.2 to 0.04) | |

| Traffic densityc | −0.07 (−0.19 to 0.05) | −0.09 (−0.20 to 0.03) | −0.13 (−0.25 to −0.01) | |

| Exposure | ≥ 200m | 100m - 199m | 50m - 99m | <50m |

| Distance to roadwayc | 0.08 (−0.09 to 0.26) | −0.03 (−0.28 to 0.21) | −0.26 (−0.49 to −0.04) | |

|

| ||||

| Change in weight-for-length z-score birth to 6 months of age (95 CI)d | ||||

|

| ||||

| Exposure |

Quartile 1

(lowest)b |

Quartile 2 | Quartile 3 |

Quartile 4

(highest) |

| 3rd-trimester black carbon | 0.08 (−0.15 to 0.31) | 0.07 (−0.16 to 0.31) | 0.16 (−0.09 to 0.41) | |

| 3rd-trimester PM2.5 | 0.10 (−0.16 to 0.35) | 0.14 (−0.11 to 0.39) | 0.10 (−0.15 to 0.34) | |

| Traffic densitye | 0.22 (−0.02 to 0.46) | 0.25 (0.00 to 0.49) | 0.25 (0.01 to 0.49) | |

| Exposure | ≥200m | 100m - 199m | 50m - 99m | <50m |

| Distance to roadwaye | −0.04 (−0.38 to 0.31) | 0.03 (−0.49 to 0.54) | 0.18 (−0.35 to 0.70) | |

|

| ||||

| Odds Ratio (95% CI) for weight-for-length ≥95th percentile at 6 months of aged | ||||

|

| ||||

| Exposure |

Quartile 1

(lowest)b |

Quartile 2 | Quartile 3 |

Quartile 4

(highest) |

| 3rd-trimester black carbon | 0.93 (0.58 to 1.5) | 1.41 (0.89 to 2.24) | 1.37 (0.85 to 2.19) | |

| 3rd-trimester PM2.5 | 1.10 (0.67 to 1.81) | 1.30 (0.8 to 2.13) | 1.18 (0.73 to 1.92) | |

| Traffic densitye | 1.57 (0.94 to 2.61) | 0.97 (0.56 to 1.68) | 1.84 (1.11 to 3.05) | |

| Exposure | ≥200m | 100m - 199m | 50m - 99m | <50m |

| Distance to roadwaye | 0.78 (0.34 to 1.77) | 0.78 (0.26 to 2.30) | 1.85 (0.75 to 4.55) | |

Adjusted for household income, paternal BMI, and maternal education, race/ethnicity, prepregnancy BMI, gestational weight gain, gestational diabetes, and smoking

Reference category

Restricted to participants who did not move during pregnancy

Adjusted for above and infant birth weight-for-gestational age z-score and gestational age. Reference group is weight-for-length <95th percentile at 6 months of age

Restricted to participants who did not move during pregnancy or 0-6 months postpartum

Prenatal pollution and fetal growth measures at birth

Among infants exposed to the highest (vs. lowest) quartile of black carbon during the third trimester, we observed lower fetal growth in unadjusted models (birth weight-for-gestational age z-score = −0.31 [95% confidence interval (CI) = −0.43 to −0.19]) and covariate-adjusted models (−0.17 [−0.29 to −0.05]). Neighborhood traffic density and roadway proximity were similarly associated with lower fetal growth. Third-trimester PM2.5 had weaker associations with fetal growth, and effect estimates were imprecise (Table 2; Figure).

Figure 1.

Associations of prenatal air pollution exposure with birth weight for gestational age z-score (fetal growth) and odds of weight-for-length ≥95th percentile at 6 months of age. All estimates are adjusted for household income, paternal BMI, and maternal education, race/ethnicity, prepregnancy BMI, gestational weight gain, gestational diabetes, and smoking habits. The odds ratios for weight-for-length ≥95th percentile are additionally adjusted for birth weight-for-gestational age z-score and gestational age. WFL indicates weight-for-length; BC indicates black carbon.

Pollution and infant weight gain

Infants in the highest (vs. lowest) quartile of neighborhood traffic density had greater weight-for-length gain from 0 to 6 months of age (unadjusted weight-for-length z-score change = 0.23 [95% CI = −0.00 to 0.47]; covariate-adjusted, 0.29 [0.04 to 0.53]). Estimates were attenuated slightly when models were additionally adjusted for fetal growth and gestational age (0.25 [0.01 to 0.49]), which are potentially on the pathway between prenatal air pollution exposure and infant weight gain. Living less than 50 m from a major roadway or being in the highest quartile of third trimester black carbon or PM2.5 exposure was also associated with 0-6-month weight-for-length gain, although effect estimates were imprecise (Table 2).

Infants in the highest (vs. lowest) quartile of neighborhood traffic density also had greater odds of weight-for-length ≥95th percentile at 6 months in unadjusted (1.71 [1.05 to 2.76]), covariate-adjusted (1.78 [1.08 to 2.94]), and fetal-growth- and gestational-age-adjusted (1.84 [1.11 to 3.05]) models. Living less than 50 m from a major roadway or being in the highest quartile of third-trimester black carbon or PM2.5 exposure was also associated with higher odds of weight-for-length ≥95th percentile, although effect estimates were imprecise (Table 2; Figure). Associations with 0-6 month weight-for-length gain and weight-for-length ≥95th percentile were generally stronger for the traffic-related markers of pollution than for PM2.5.

Pollution and the phenotype of lower fetal growth and rapid infant growth

The odds of having the phenotype of lower fetal growth and more rapid 0-6 month weight-for-length gain (as compared with normal fetal growth and normal 0-6 month weight-for-length gain) was greater for infants exposed to higher traffic density (Q4 vs. Q1 adjusted OR 3.01 [95% CI = 1.08 to 8.44]) and higher levels of third-trimester black carbon (Q4 vs. Q1 OR 2.00 [0.82 to 4.84]) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Adjusteda odds of normal fetal growth/normal gain in 0-6 month weight-for-length z-score (WFL-z) (reference) vs. lower fetal growth/normal gain in 0-6 month WFL-z, normal fetal growth/more rapid gain in 0-6 month WFL-z, or lower fetal growth/more rapid gain in 0-6 month WFL-z (outcome of interest) for infants in the highest (vs. lowest) quartile of exposure to black carbon during the 3rd trimester and neighborhood traffic density. Lower versus normal fetal growth defined as Q1 (vs. Q2-4) and more rapid versus normal 0-6 month WFL-z defined as Q4 (vs. Q1-3).

| Normal fetal growth and normal gain in 0-6 month WFL-zb |

Lower fetal growth and normal gain in 0-6 month WFL-z |

Normal fetal growth and more rapid gain in 0-6 month WFL-z |

Lower fetal growth and more rapid gain in 0-6 month WFL-z |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3rd-trimester black carbon |

0.93 (0.47 to 1.87) | 1.94 (1.05 to 3.60) | 2.00 (0.82 to 4.84) | |

| Neighborhood traffic density |

1.57 (0.80 to 3.08) |

2.96 (1.50 to 5.85) | 3.01 (1.08 to 8.44) |

Adjusted for household income, paternal BMI, and maternal education, race/ethnicity, prepregnancy BMI, gestational weight gain, gestational diabetes, smoking habits, and gestational age.

Reference category

Secondary analyses

The magnitudes of the associations of first-and second-trimester black carbon and PM2.5 exposure with reduced fetal growth were similar to those third-trimester exposures. When considering associations of first and second trimester and 0-6 month postnatal black carbon and PM2.5 exposure with more rapid infant weight gain (0-6 month weight-for-length gain and weight-for-length ≥95th percentile at 6 months), effect estimates were generally smaller than for third-trimester exposures (data available upon request). For example, change in weight-for-length z-score from 0 to 6 months of age was 0.07 (95% CI = −0.18 to 0.32) among infants exposed to the highest (vs. lowest) quartile of black carbon during the first 6 months of life versus 0.16 (−0.09 to 0.41) among infants exposed to the highest (vs. lowest) quartile of black carbon during the third trimester.

When we included census tract covariates (median household income, percent below poverty, and percent with bachelor’s degree ) in the final model, associations of air pollution exposure with fetal growth were somewhat attenuated whereas associations with infant weight gain were unchanged (data available upon request). For example, among infants exposed to the highest (vs. lowest) quartile of neighborhood traffic density, birth weight-for-gestational age z-score was −0.09 z-units lower (95% CI = −0.22 to 0.04) (vs. final model −0.13 [−0.25 to −0.01]), 0-6 month weight-for-length gain was 0.26 z-units higher (0.00 to 0.52) (vs. final model, 0.25 [0.01 to 0.49]), and odds of weight-for-length ≥95th percentile at 6 months was 1.93 times higher (1.12 to 3.34) (vs. final model, OR = 1.84 [1.11 to 3.05]).

DISCUSSION

Prenatal exposure to traffic-related pollution was associated with reduced fetal growth at birth and rapid infant weight gain in our analysis of data from a large, prospective cohort. Among infants with the highest exposures to traffic-related pollution, the combination of lower fetal growth and more rapid weight gain in infancy was three times as likely as the combination of normal fetal and postnatal growth. This pattern raises the possibility that prenatal air pollution exposure entrains a “thrifty phenotype” of small size at birth followed by rapid gain in adiposity.22

Mechanistically, air pollution may reduce fetal growth through maternal, placental, or fetal oxidative stress and related DNA damage, inflammation, blood coagulation, or vascular dysfunction, thereby inhibiting nutrient transfer from mother to fetus.3 Air pollution may directly induce weight gain via adipose tissue inflammation and hypertrophy6 or neuroinflammation with consequent brain remodeling and altered satiety signals.23

Our finding of an association between higher prenatal air pollution exposure and reduced fetal growth is consistent with prior studies.1, 2 We demonstrated fairly large associations between prenatal black carbon and traffic density exposures and early growth while accounting for well-specified sociodemographic information obtained by in-person interview and questionnaire. For example, infants in the highest (vs. lowest) quartile of third-trimester black carbon exposure had an adjusted mean 0.17 units lower (95% CI = −0.29 to −0.05) birth weight-for-gestational age z-score, which translates to an 86 g (18 to 127) lower birth weight for a full-term newborn at the 50th percentile for weight.15 This difference is smaller than the 175-200g decreased birth weight observed in newborns with mothers who smoked (vs. did not smoke) prenatally,24 but larger than the 20-40g decrease in birth weight typically associated with a 20 µg/m3 increase in PM10 or PM2.5.1, 2 The larger effect estimates may result partially from spatial confounding, as effect estimates were attenuated when neighborhood census tract covariates were added to the final adjusted model. Alternatively, they may reflect more precise exposure estimates as a result of using a well-specified spatiotemporal land-use regression black carbon model. As reviewed by Stieb, et al,1 48 of 62 prior studies of air pollution and birth weight measured exposures at a centrally-located monitor.

Of note, we observed a more pronounced black carbon as compared to PM2.5 effect in our cohort. This could reflect the fact that we applied a land-use regression model matched to a subject’s residential address to estimate black carbon exposure, whereas we used an aerosol-optical-depth model to estimate PM2.5 exposure in 10 × 10 km blocks. Also, because satellite data became available after we began recruitment, sample sizes were smaller for analyses of PM2.5 exposure, which may have limited our power to see an association. Additional studies are needed to determine whether black carbon and other traffic-related pollutants may be more strongly associated with fetal growth than air pollution from other sources.

While the relationship of prenatal air pollution exposure with restricted fetal growth has been fairly well-established, the extent to which such exposure may impact growth during childhood has not been well-studied. In our cohort, higher neighborhood traffic density was associated with more rapid weight-for-length gain from 0 to 6 months of age and increased odds of weight-for-length ≥95th percentile at 6 months of age. Our results are in line with other cohort studies that have demonstrated an association between prenatal exposure to tobacco smoke (comprised of particulate matter, gases and toxins) and offspring weight gain4 and between prenatal exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon (a combustion byproduct of fossil fuel and biomass burning) and obesity at 5 years of age.5

The sample size for all postnatal growth models was substantially smaller (by about half) compared with the fetal growth models. As was the case for fetal growth, the association between black carbon and other direct measures of traffic (traffic density and distance to roadway) with infant weight gain was generally stronger than for PM2.5.

A limitation of our analyses of infant weight gain was the difficulty in distinguishing the timing of effects in relation to gestation. The traffic density and distance to roadway metrics were spatially but not temporally resolved, which made us unable to differentiate prenatal versus postnatal effects of these exposures. Our black carbon and PM2.5 models were able to estimate unique prenatal and postnatal exposure estimates, and associations of black carbon with infant weight gain were stronger for third trimester than for 0-6-month postnatal exposures, but the exposure metrics were moderately correlated (r=0.66), and confidence intervals around the effect estimates overlapped. Further research is needed to determine whether late pregnancy, when the majority of fetal growth occurs,25 or cumulative prenatal and postnatal exposure, as represented by the traffic density and distance to roadway metrics, may be vulnerable exposure windows for air pollution and infant weight gain.

In rare instances, our data showed non-monotonic associations between an exposure and health outcome. For example, odds of weight-for-length ≥95th percentile at 6 months was greater for infants in the second as compared with the third quartile of traffic density. Exposure misclassification is one possible explanation; as is typical in air pollution epidemiology, our residential exposure estimates were long-term and did not incorporate time-activity patterns. Non-monotonic associations could alternatively be due to spatial or other unmeasured confounders not correlated equally with the exposure across all four quartiles. However, even with the addition of several spatial covariates to the final adjusted model, these non-monotonic effects remained.

The potential for spatial autocorrelation is minimized in the Project Viva cohort because addresses of the participants were distributed over a wide area. The 2,112 geocoded participant addresses at the time of delivery were located in 636 different census tracts, with 215 of these tracts having only one address. However, the potential for unmeasured spatial confounding is a risk in all environmental epidemiologic studies, and distinguishing the role of spatial factors versus pollution is challenging, as the two are closely correlated. The addition of census-tract covariates to our final adjusted model resulted in attenuation of effect estimates in analyses of fetal growth but not infant weight gain, suggesting that the former might be more heavily influenced by spatial confounding.

In the present study, infants with higher prenatal exposure to traffic-related pollution were more likely to be in the lowest quartile of fetal growth but highest quartile of weight-for-length gain during the first 6 months of life. The extent to which air pollution exposure may be associated with this “thrifty phenotype” may have important implications for future cardiometabolic disease risk.26 For example, rodents with reduced fetal growth had impaired insulin sensitivity in adulthood when growth during infancy was faster.9 In our cohort, infants in the lowest quartile of fetal growth and highest quartile of weight-for-length z-score at 6 months of age had the highest blood pressures at 2-4 years of age.8 Tobacco smoke exposure has been associated with reduced fetal growth and rapid postnatal weight gain4 and with an adverse cardiometabolic profile in adulthood.27 Further studies in this cohort and others will help to elucidate whether air pollution exposure is associated with later cardiometabolic disease following this thrifty phenotype in early life.

Strengths of our study included use of a large, prospective cohort with several measures of air pollution exposure and inclusion of multiple potential confounding variables. Our well-specified spatiotemporal black carbon land-use-regression model and our use of a birth weight-for-gestational age z-score outcome were particular strengths. Limitations of the study included inability to differentiate effects of gestational versus postnatal exposures for traffic density and distance to roadway. Also, lack of information on mother’s time-activity patterns may have reduced the accuracy of the air pollution models and biased results toward the null.28 Also, generalizability may be limited, as mothers in our cohort were generally well educated and mostly white, although the proportions of racial/ethnic minorities in Project Viva were higher than in Massachusetts as a whole, according to the 2000 census.29

In conclusion, higher third-trimester black carbon exposure and neighborhood traffic density predicted reduced fetal growth in Boston-area infants. Higher neighborhood traffic density in early life was also associated with greater weight gain in infancy. Additional studies are necessary to determine the extent to which this pattern may contribute to future cardiovascular disease risk.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Wei Perng for helpful input regarding statistical modeling. We appreciate the work of past and present Project Viva staff and the ongoing participation of the Project Viva mothers and children.

Source of Funding : The authors have received support from the National Institutes of Health (K24HD069408, R37HD034568, P30DK092924, P03ES000002, P01ES009825, R01AI102960, K12DK094721-02), the Environmental Protection Agency (RD83479801), the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (T32HS000063), the Harvard School of Public Health, and the Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute. This publication’s contents are solely the responsibility of the grantee and do not necessarily represent the official views of the US EPA. Further, US EPA does not endorse the purchase of any commercial products or services mentioned in the publication.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Stieb DM, Chen L, Eshoul M, Judek S. Ambient air pollution, birth weight and preterm birth: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Environ Res. 2012 Aug;117:100–111. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2012.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dadvand P, Parker J, Bell ML, et al. Maternal exposure to particulate air pollution and term birth weight: a multi-country evaluation of effect and heterogeneity. Environ Health Perspect. 2013 Mar;121(3):267–373. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1205575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kannan S, Misra DP, Dvonch JT, Krishnakumar A. Exposures to airborne particulate matter and adverse perinatal outcomes: a biologically plausible mechanistic framework for exploring potential effect modification by nutrition. Environ Health Perspect. 2006 Nov;114(11):1636–1642. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oken E, Levitan EB, Gillman MW. Maternal smoking during pregnancy and child overweight: systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Obes (Lond) 2008 Feb;32(2):201–210. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rundle A, Hoepner L, Hassoun A, et al. Association of childhood obesity with maternal exposure to ambient air polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons during pregnancy. Am J Epidemiol. 2012 Jun 1;175(11):1163–1172. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sun Q, Yue P, Deiuliis JA, et al. Ambient air pollution exaggerates adipose inflammation and insulin resistance in a mouse model of diet-induced obesity. Circulation. 2009 Feb 3;119(4):538–546. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.799015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rogers I. The influence of birthweight and intrauterine environment on adiposity and fat distribution in later life. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2003 Jul;27(7):755–777. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Belfort MB, Rifas-Shiman SL, Rich-Edwards J, Kleinman KP, Gillman MW. Size at birth, infant growth, and blood pressure at three years of age. J Pediatr. 2007 Dec;151(6):670–674. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2007.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lim K, Armitage JA, Stefanidis A, Oldfield BJ, Black MJ. IUGR in the absence of postnatal "catch-up" growth leads to improved whole body insulin sensitivity in rat offspring. Pediatr Res. 2011 Oct;70(4):339–344. doi: 10.1203/PDR.0b013e31822a65a3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oken E, Baccarelli AA, Gold DR, et al. Cohort Profile: Project Viva. Int J Epidemiol. 2014 Mar;16 doi: 10.1093/ije/dyu008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fleisch AF, Gold DR, Rifas-Shiman SL, et al. Air Pollution Exposure and Abnormal Glucose Tolerance during Pregnancy: The Project Viva Cohort. Environ Health Perspect. 2014 Apr;122(4):378–383. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1307065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gryparis A, Coull B, Schwartz J, Suh H. Semiparametric latent variable regression models for spatio-teomporal modeling of mobile source particles in the greater Boston area. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series C (Applied Statistics) 2007;56(2):183–209. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zanobetti A, Coull BA, Gryparis A, et al. Associations between arrhythmia episodes and temporally and spatially resolved black carbon and particulate matter in elderly patients. Occup Environ Med. 2014 Mar;71(3):201–207. doi: 10.1136/oemed-2013-101526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kloog I, Koutrakis P, Coull B, Joo Lee H, Schwartz J. Assessing temporally and spatially resolved PM2.5 exposures for epidemiological studies using satellite aerosol optical depth measurements. Atmospheric Environment. 2011;45:6267–6275. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Oken E, Kleinman KP, Rich-Edwards J, Gillman MW. A nearly continuous measure of birth weight for gestational age using a United States national reference. BMC Pediatr. 2003 Jul 8;3:6. doi: 10.1186/1471-2431-3-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.National Center for Health Statistics 2000 CDC growth charts: United States. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/growthcharts/2000growthchart-us.pdf. Date accessed: 4/9/14. [PubMed]

- 17.Karner AA, Eisinger DS, Niemeier DA. Near-roadway air quality: synthesizing the findings from real-world data. Environ Sci Technol. 2010 Jul 15;44(14):5334–5344. doi: 10.1021/es100008x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhu Y, Hinds WC, Kim S, Sioutas C. Concentration and size distribution of ultrafine particles near a major highway. J Air Waste Manag Assoc. 2002 Sep;52(9):1032–1042. doi: 10.1080/10473289.2002.10470842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.U.S. Census Bureau Census 2000 Summary File 3. 2000 http://www.census.gov/census2000/sumfile3.html. Date accessed: 4/9/14.

- 20.Rubin DB. Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. Wiley-Interscience; Hoboken, N.J.: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Environmental Protection Agency Observational Data for Black Carbon. 2012 http://www.epa.gov/blackcarbon/2012report/Chapter5.pdf. Date accessed: 4/9/14.

- 22.Hales CN, Barker DJ. Type 2 (non-insulin-dependent) diabetes mellitus: the thrifty phenotype hypothesis. Diabetologia. 1992 Jul;35(7):595–601. doi: 10.1007/BF00400248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bolton JL, Smith SH, Huff NC, et al. Prenatal air pollution exposure induces neuroinflammation and predisposes offspring to weight gain in adulthood in a sex-specific manner. FASEB J. 2012 Nov;26(11):4743–4754. doi: 10.1096/fj.12-210989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lumley J. Stopping smoking. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1987 Apr;94(4):289–292. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1987.tb03092.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cunningham FG, Williams JW. Williams obstetrics. 23rd McGraw-Hill Medical; New York: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Symonds ME, Sebert SP, Hyatt MA, Budge H. Nutritional programming of the metabolic syndrome. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2009 Nov;5(11):604–610. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2009.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cupul-Uicab LA, Skjaerven R, Haug K, Melve KK, Engel SM, Longnecker MP. In utero exposure to maternal tobacco smoke and subsequent obesity, hypertension, and gestational diabetes among women in the MoBa cohort. Environ Health Perspect. 2012 Mar;120(3):355–360. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1103789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nethery E, Leckie SE, Teschke K, Brauer M. From measures to models: an evaluation of air pollution exposure assessment for epidemiological studies of pregnant women. Occup Environ Med. 2008 Sep;65(9):579–586. doi: 10.1136/oem.2007.035337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.United States Census Bureau. American Factfinder 2000 Available: http://factfinder2.census.gov/faces/nav/jsf/pages/index.xhtml. Date accessed: 4/9/14.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.