Abstract

OBJECTIVE

Our goal was to determine if multiple courses of antenatal betamethasone affect auditory neural maturation in 28 to 32 weeks’ gestational age infants.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

A retrospective cohort study was performed to compare auditory neural maturation between premature infants exposed to 1 course of betamethasone and infants exposed to ≥2 courses of betamethasone. Inclusion criteria included all 28 to 32 weeks’ gestational age infants delivered between July 1996 and December 1998 who had auditory brainstem response testing performed (80-dB click stimuli at a repetition rate of 39.9/second) within 24 hours of postnatal life as part of bilirubin-auditory studies. Infants with toxoplasmosis, rubella, cytomegalovirus, herpes infections, chromosomal disorders, unstable conditions, exposure to antenatal dexamethasone, and exposure to <1 complete course of betamethasone were excluded. Auditory waveforms were categorized into response types on response replicability and peak identification as types 1 through 4 (type 1 indicating most mature). Absolute and interpeak wave latencies were measured when applicable. Categorical and continuous variables were analyzed by using the χ2 test and Student’s t test, respectively.

RESULTS

Of 174 infants studied, 123 received antenatal steroids. Of these, 50 received 1 course and 29 received ≥2 courses of betamethasone. There were no significant differences in perinatal demographics between the 2 groups. After controlling for confounding variables, there was no significant difference in mean absolute wave latencies, mean interpeak latencies, or distribution of response type between the 2 groups. There also was no significant difference in any auditory brainstem response parameters between infants exposed to 1 course of betamethasone (n = 50) and infants exposed to >2 courses of betamethasone (n = 17).

CONCLUSION

Compared with a single recommended course of antenatal steroids, multiple courses of antenatal betamethasone are not associated with a deleterious effect on auditory neural maturation in 28 to 32 weeks’ gestational age infants.

Keywords: antenatal betamethasone, auditory neural, maturation, auditory brainstem evoked, response, premature infants

Animal studies have demonstrated that repeated courses of antenatal corticosteroids delay myelination and cellular development in the central nervous system.1–3 In addition, recent studies using smaller doses of corticosteroids, comparable to those in human clinical trials involving antenatal corticosteroids, have demonstrated alteration of nuclear transcription factors that regulate brain cell differentiation, alteration of neuronal cytoskeleton, and morphologic alteration of synapses.4–6 As a result, the second National Institutes of Health consensus development conference in August 2000 on the effect of repeat courses of corticosteroids on fetal maturation emphasized the concern for possible deleterious effects of multiple courses of corticosteroids on the developing central nervous system of premature infants.7 The consensus report concluded that the use of multiple courses of antenatal corticosteroids should be limited to patients enrolled in clinical research and that clinical studies are required to evaluate the acute and chronic effects of multiple courses of antenatal corticosteroids on the developing brain in premature infants.

Limited existing human data based on observational studies suggest that multiple courses of antenatal corticosteroids are associated with long-term adverse effects on the developing brain.8,9 These data also suggest that the long-term adverse effect on the developing brain may be specific to the corticosteroid preparation used, and that repeated courses of betamethasone may not be associated with long-term abnormal neurologic outcome.8–10 However, no data exist regarding acute, short-term effects of multiple courses of betamethasone on brain maturation in premature infants.

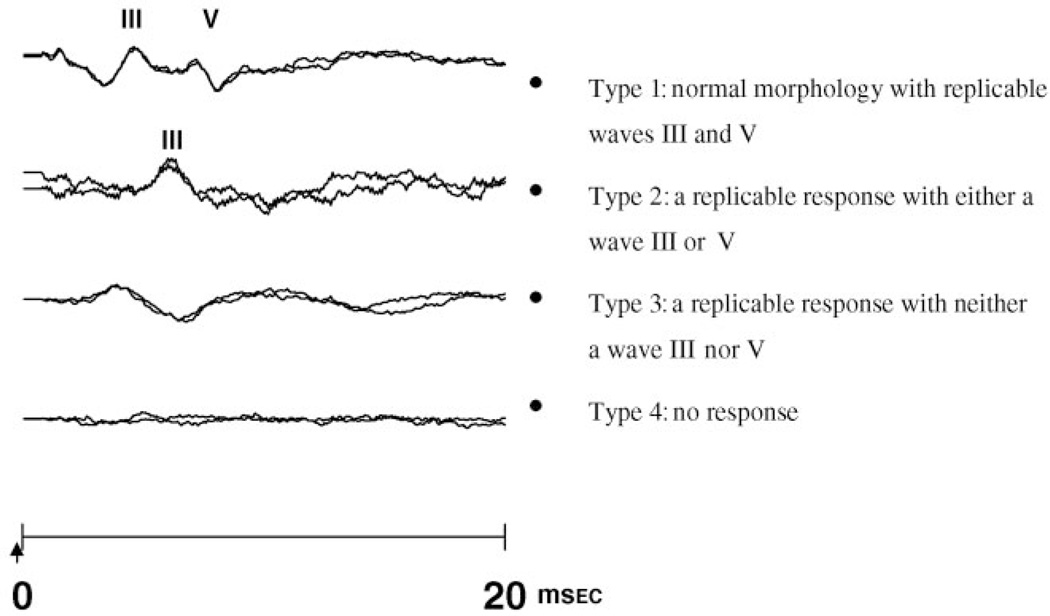

Auditory brainstem evoked response (ABR) is a noninvasive neurophysiologic assessment of brainstem maturation in premature infants. The ABR waveform in mature neonates is comprised of 3 waves (I, III, and V). Electrophysiologic data have shown that wave I is generated peripherally in the auditory nerve.11 Wave III reflects the firing of axons exiting the cochlear nuclear complex in the brainstem, whereas wave V primarily reflects an action potential generated by axons from the lateral lemniscus at a more rostral brainstem location.11 There is a rapid maturation of the ABR that parallels the critical period of brainstem myelination, neuronal development, and axonal growth. With increasing gestational age, maturation of the ABR is characterized by improving detectability of the response peaks and shortening of the absolute wave latencies and interpeak latencies.12,13 The decrease in wave I latency reflects the maturation of the peripheral auditory system, whereas the decreases in waves III and V latencies reflect the combined effects of peripheral and central maturation in the auditory system. The decrease in interpeak latencies reflects changes in nerve conduction velocity. Both absolute and interpeak latencies are influenced by degree of myelination, axonal growth, and synaptic function. Because waves I, III, and V are not always detectable in premature infants ≤32 weeks’ gestational age, the waveform can also be categorized as a response type based on the replicability of the response and the presence of wave III or wave V (Fig 1).13 The response type also demonstrates progressive maturation with increasing gestational age. There is limited literature about the direct effect of glucocorticosteroids on auditory brainstem responses in humans.14,15 In adults, hydrocortisone administration was shown to acutely reduce absolute latencies, but there was no longterm follow-up assessment. We previously demonstrated that there was no significant difference in auditory neural maturation between premature infants who were exposed to antenatal steroids and infants who were not exposed to antenatal steroids as measured by the ABR within 24 hours of birth.15 However, because there was considerable variation in the total maternal dosage, any dose-dependent effects may have been obscured. This study seeks to determine whether multiple courses of antenatal betamethasone have any effect on auditory neural maturation in infants 28 to 32 weeks’ gestational age.

FIGURE 1.

ABR waveform response types 1 through 4. The arrow indicates initiation of sound stimulus.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

Study Design

This was a retrospective cohort study comparing auditory neural maturation of premature infants exposed to multiple courses of antenatal betamethasone with premature infants exposed to a single complete course of betamethasone.

Study Population

All infants 28 to 32 weeks’ gestational age at birth admitted to the NICU of Golisano Children’s Hospital from July 1996 to December 1998 and who had an ABR performed within the first 24 hours of postnatal life as part of our ongoing ABR/bilirubin studies13,16 were potentially eligible for this study. Infants with craniofacial anomalies, chromosomal disorders, TORCH (toxoplasmosis, other infections, rubella, cytomegalovirus infection, and herpes simplex) infection or those who were too clinically unstable for ABR testing within the first 24 hours after birth were excluded. In addition, infants exposed to antenatal dexamethasone or <1 complete course of antenatal betamethasone therapy (total: 24 mg) were excluded from this study.

Gestational age was assessed by obstetrical dating criteria or, when obstetrical data were inadequate, by Ballard examination. At the time of the study, the recommended antenatal glucortocoid regimen consisted of the administration to the mothers of two 12-mg doses of betamethasone given intramuscularly 24 hours apart. If the mother had not delivered 1 week after receipt of the single course, weekly courses of betamethasone were considered. Infants whose mothers had been given 1 full complete course of betamethasone at any time before birth to accelerate fetal lung maturation constituted the 1-course antenatal betamethasone group (group I). The infants who received ≥2 complete courses of betamethasone constituted the multiple-course antenatal betamethasone group (group II). Among the multiple-course antenatal betamethasone group, infants were subdivided into those who received 2 completed courses (group IIa) and those who received >2 completed courses of betamethasone (group IIb). Data were collected on mode of delivery, chorioamnionitis, in utero exposure to cocaine and other illicit drugs, use of antenatal magnesium sulfate, 5-minute Apgar score <5, and mechanical ventilation at the time of ABR testing.

ABR

ABRs were recorded with a Biological Navigator evoked-response system, with the subjects lying supine in the isolette and skin temperature >35.5°C. Testing was performed once during the first 12 to 24 hours of postnatal life by audiologists skilled in the administration of ABR tests to NICU infants. Electrode sites were mastoid (reference), midline on high forehead or crown of the head (active), and shoulder (ground). An audiologist inspected the ear canals and removed any visible vernix or debris before each ABR test. Electrode gel was applied to silver/silver chloride electrodes. Bilateral monaural ABR tests were performed by using 80 dB normal hearing level broadband click stimuli with supraaural earphones. The clicks were presented at a repetition rate of 39.9/ second, and 3 runs of 2000 repetitions were recorded for each ear. The 2 most replicable runs for each ear were averaged and used for analysis. The ABRs were analyzed by the audiologists without knowledge of gestational age or antenatal steroid status.

Because ABR waves I, III, and V cannot be detected in all premature infants ≤32 weeks’ gestational age, ABR waveforms were categorized into response types on the basis of response replicability and peak identification: type 1, a waveform with normal morphology and replicable waves III and V; type 2, a replicable response with either a wave III or V; type 3, a replicable response with neither a wave III or V; and type 4, a waveform with no replicable response (Fig 1). If the waveform was type 1 or 2, latencies for waves I, III, and V and interpeak latencies I to III, III to V, and I to V were measured. The response for the better ear was used for final analysis. The study was approved by the Human Subject Review Board, and informed consent was obtained from parents before ABR testing.

Sample-Size Calculations and Statistical Analysis

An approximate sample size was determined for the number of neonates to be studied on the basis of earlier findings of ABR maturation study.13 On the basis of earlier findings, 15 subjects in each group would allow detection of actual difference of 0.7 milliseconds (equal to >0.75 SD) for absolute latencies and interpeak latencies for infants 28 to 32 weeks’ gestational age with an α level of .05 and a power of .80.

Student’s t test was used to analyze continuous variables using Stata (Stata Corp, College Station, TX). A χ2 or Fisher’s exact test, as appropriate, was used to analyze nominal variables. Multiple regression analysis was performed to assess the independent relations of multiple variables with measured ABR parameters. All tests were 2 sided, and a P value of <.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Demographics

A total of 174 infants 28 to 32 weeks’ gestational age were eligible for this study. Of these, 123 received antenatal steroids, whereas 51 infants did not. Of 123 infants who received antenatal steroids, 29 infants who received <1 complete course of betamethasone, 5 infants who received antenatal dexamethasone therapy, and 6 infants who received between 1 and 2 courses of betamethasone were excluded. For 4 outborn infants, it was unclear whether infants received a partial or complete course of antenatal steroid therapy, thus they were also excluded. Of the remaining 79 infants, 50 infants (group I) received 1 complete course of antenatal betamethasone, whereas 29 infants (group II) received ≥2 courses of antenatal betamethasone. Of 29 infants, 17 infants (group IIb) received >2 courses of betamethasone (mean dosage: 80 mg; range: 60–144 mg). Among group I infants, 95% of infants received the last dose of betamethasone >24 hours but less than a week before delivery. Among group II infants, 100% of infants received the last dose of betamethasone >24 hours but less than a week before delivery. The demographics of the study patients as a function of exposure to 1 or ≥2 courses of antenatal betamethasone are shown in Table 1. There were no significant differences between group I and group II in gestational age at birth (P = .4), birth weight (P = .9), small for gestational age (P = .6), gender distribution (P = .6), race (P = .1), exposure to antenatal magnesium sulfate (P = .7), maternal chorioamnionitis (P = .9), in utero exposure to illicit drugs (P = .3), rate of cesarean-section delivery (P = .4), 5-minute Apgar score <5 minutes (P = .4), or use of mechanical ventilation (P = .2) at the time of testing.

TABLE 1.

Demographic Profile of the Study Population as a Function of 1 or ≥2 Courses of Antenatal Betamethasone

| 1 Course of Betamethasone (N = 50), Group I |

≥2 Courses of Betamethasone (N = 29), Group II |

2 Courses of Betamethasone (N = 12), Group IIa |

>2 Courses of Betamethasone (N = 17), Group IIb |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Birth weight, ga | 1396 ± 272 | 1400 ± 265 | 1501 ± 321 | 1335 ± 206 |

| Gestational age, wka | 30.2 ± 1.2 | 30.4 ± 1.2 | 30.4 ± 1.5 | 30.3 ± 0.99 |

| Small for gestational age, % | 6 | 10 | 8 | 12 |

| Gender, % maleb | 46 | 52 | 66 | 41 |

| Race, % blackb | 34 | 18 | 33 | 6c |

| Exposure to magnesium sulfate, %b | 70 | 66 | 66 | 64 |

| Maternal chorioamnionitis, %b | 24 | 24 | 42 | 12 |

| In utero exposure to illicit drugs, %b | 10 | 4 | 0 | 5 |

| Rate of delivery by cesarean section, %b | 44 | 35 | 25 | 41 |

| Apgar score <5 at 5 min, %b | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Mechanical ventilation on day 1, %b | 56 | 42 | 58 | 29c |

Group I versus II and group I versus IIb.

Mean ± SD using t test.

Proportions were analyzed by using the χ2 test.

The P value was significant when compared with 1 course of betamethasone.

Wave Latencies

There were no significant differences in absolute latencies and interpeak latencies between group I and group II (P > .23; Table 2). The differences in absolute latencies and interpeak latencies between the infants in the 2 groups remained insignificant when controlled for gestational age, birth weight, race, maternal treatment with magnesium sulfate, chorioamnionitis, in utero exposure to illicit drugs, and 5-minute Apgar score <5 using a multiple regression model. For comparison, absolute latencies and interpeak latencies for infants 28 to 32 weeks’ gestational age (mean ± SD: 30.6 ± 1.2 weeks) who did not receive antenatal steroids (n = 51; Table 2) are given. There was no significant difference in absolute latencies and interpeak latencies between infants who did not receive antenatal steroids and infants who received 1 or multiple courses of antenatal betamethasone.

TABLE 2.

Absolute Latencies and Interpeak Latencies as a Function of 1 or ≥2 Courses of Antenatal Betamethasone in Infants 28 to 32 Weeks’ Gestational Age

| No Antenatal Steroids (N = 51), Mean ± SD |

1 Course of Betamethasone (N = 50), Group I, Mean ± SD |

≥2 Courses of Betamethasone (N = 29), Group II, Mean ± SD |

>2 Courses of Betamethasone (N = 17), Group IIb, Mean ± SD |

Pa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Absolute latencies, msec | |||||

| Latency I | 2.91 ± 0.6 | 2.94 ± 0.48 | 3.34 ± 0.84 | 2.95 ± 0.51 | NS |

| Latency III | 6.3 ± 0.64 | 6.26 ± 0.80 | 6.34 ± 0.40 | 6.23 ± 0.36 | NS |

| Latency V | 9.5 ± 0.8 | 9.50 ± 1.05 | 9.69 ± 0.62 | 9.5 ± 0.49 | NS |

| Interpeak latencies, msec | |||||

| Latency I–III | 3.22 ± 0.61 | 3.05 ± 0.81 | 2.86 ± 0.43 | 2.93 ± 0.4 | NS |

| Latency III–V | 2.95 ± 0.57 | 3.11 ± 0.45 | 3.06 ± 0.37 | 3.09 ± 0.36 | NS |

| Latency I–V | 6.27 ± 1.0 | 5.84 ± 0.80 | 6.19 ± 0.68 | 6.3 ± 0.67 | NS |

NS indicates nonsignificant.

Group I versus II and group I versus IIb using t test.

Response Types

The frequency distribution of response types are shown in Table 3. The difference in the frequency distribution of response types between the infants in group I and group II remained insignificant (P = .7) after controlling for possible confounders, as above.

TABLE 3.

Frequency Distribution of ABR Response Types as a Function of Exposure to 1 or ≥2 Courses of Antenatal Betamethasone

| Response Types | No Antenatal Steroids (N = 51), % |

1 Complete Course of Betamethasone (N = 50), Group I, % |

≥2 Courses of Betamethasone (N = 29), Group II, % |

>2 Courses of Betamethasone (N = 17), Group IIb, % |

P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 42 | 48 | 45 | 65 | NS |

| 2 | 18 | 16 | 10 | 6 | |

| 3 | 28 | 22 | 24 | 23 | |

| 4 | 12 | 14 | 21 | 6 |

NS indicates nonsignificant.

Subgroup Analysis

On subgroup analysis of the data for infants who received >2 courses of betamethasone (group IIb) compared with infants who received 1 course of betamethasone (group I), there was no difference in any of the demographic characteristics except for race and use of mechanical ventilation on the first day (Table 1). Infants exposed to >2 courses of antenatal betamethasone were less likely to be mechanically ventilated on day 1 (P = .05). No differences in absolute or interpeak latencies between these subgroups (P > .25; Table 2) were found even after controlling for potential confounding factors. There was also no difference in the frequency distribution of response types (P = .5; Table 3).

In additional analysis to evaluate the effect of time interval from the last dose of antenatal steroid, there was no significant difference (P > .23) in absolute latencies and interpeak latencies between infants who were exposed to the last dose of betamethasone >72 hours before delivery (n = 19) and infants who were exposed to the last dose of betamethasone ≤72 hours before delivery (n = 60).

There was also no linear correlation between absolute latencies or interpeak latencies and amount of maternal betamethasone dosage (R2 < 0.09; P > .22)

DISCUSSION

Both animal studies and observational studies of premature infants suggest that repeated courses of antenatal steroids may result in long-term neurodevelopmental impairment.8,9,17 As a result, the second National Institutes of Health consensus development conference in August 2000 concluded that the use of multiple courses of antenatal corticosteroids should be limited to patients enrolled in clinical research studies. The only published randomized, controlled trial of such treatment was stopped early because of the concern raised by the consensus group.18 Approximately half of the original number of patients was enrolled before closing the study. The investigators found that the infants of women who received multiple antenatal courses of steroids had less severe respiratory distress syndrome (RDS), but there was a trend toward an increase in the incidence of intraventricular hemorrhage and chorioamnionitis. Because of the apparent lack of efficacy for the primary outcome and the decision to “do no harm,” the study was terminated early. No other trials have been completed to date.

The use of the ABR as a surrogate marker for central nervous system effects of multiple courses of antenatal steroids is based on the demonstrated effects of steroids on neuronal differentiation and synapse formation.4–6 The ABR is a noninvasive assessment of brainstem maturation in premature infants. The 3 waves that comprise the waveform represent activity at different levels of the auditory pathway. By evaluating the wave latencies, which are influenced by the degree of myelination, axonal growth, and synaptic function, inference can be made about the possible effects of antenatal steroids. As in the published randomized, controlled trial, we could find no evidence for either a beneficial or a harmful effect of multiple courses of betamethasone on in utero brainstem maturation compared with single courses.

By using ABR, we previously demonstrated that antenatal steroid therapy is not associated with acute adverse effects on auditory neural maturation in infants 24 to 32 weeks’ gestational age.15 However, there was considerable variation in the total maternal dosage that might have obscured any dose-dependent effects. In our analysis, a trend toward an increased prevalence of more mature response types was found in infants who received >2 courses of antenatal betamethasone compared with those who received fewer courses. There was no effect, either beneficial or deleterious, on absolute and interpeak latencies. This may reflect a similar lack of effect on maturation of other parts of the brain.

These findings are inconsistent with the findings from animal studies.16 One explanation may be the difference between humans and laboratory animals in the timing of the brain growth spurt and the complexity of brain development. In humans, most of the neuronal division is completed by 24 weeks’ gestation. After 24 weeks, cell division in the brain involves mainly the oligodendroglial cells that will lay down myelin.19 Secondly, the adverse effects on developing brain may be specific to the corticosteroid preparation and may not be associated with betamethasone. French et al20 in an observational study involving premature infants showed that multiple courses of betamethasone were not associated with abnormal neurologic outcome in premature infants at 3 years of age. Similarly, Baud et al9 in a retrospective cohort study reported that ≥1 courses of antenatal betamethasone was associated with a lower risk of cystic periventricular leukomalacia compared with no antenatal steroid therapy or ≥1 courses of antenatal dexamethasone. Recently, Spinillo et al8 in a prospective observational study reported that the risk of periventricular leukomalacia and abnormal neurodevelopmental outcome in premature infants was associated with multiple courses of dexamethasone but not to multiple courses of betamethasone.

Antenatal steroids are used primarily for their beneficial effect on lung maturation. Although the only published randomized trial suggests that multiple courses of antenatal steroids in infants 24 to 32 weeks’ gestational age are not beneficial overall, subgroup analysis demonstrated that multiple courses were associated with beneficial pulmonary effects in infants ≤28 weeks’ gestation.18 The meta-analysis of observational studies in premature infants also found that multiple courses of antenatal steroids were associated with a decreased incidence of RDS and patent ductus arteriosus.21 Similarly, we found that fewer infants who were exposed to multiple courses required mechanical ventilation on the first day compared with infants exposed to 1 course of betamethasone.

The major limitation of our study is its retrospective nature. However, ABR measurements and response type assignments were performed by audiologists without knowledge of the infant’s antenatal steroid status. Because our analyses were limited to infants who were exposed in utero to betamethasone, the findings may not be generalizable to premature infants exposed to dexamethasone. Although congenital middle ear effusion may affect absolute latencies, the prevalence of congenital middle ear effusion as evaluated by tympanometry or pneumatic otoscope is low (<8%) in term neonates.22 In premature infants, it is technically difficult to accurately evaluate middle ear disease by using tympanometry or pneumatic otoscope. We, therefore, used 80 db to decrease the interference from middle ear disease and external noise sources, including noise from any form of respiratory support. All subjects passed otoacoustic emission test at 34 to 35 weeks’ postmenstrual age, indicating normal middle ear function.

Findings from this study suggest that ABR may be a surrogate outcome marker that can be used to assess the potential effect of prenatal exposure to steroids or other drugs with central nervous system interactions. A decreased incidence of RDS and patent ductus arteriosus, in the absence of either short- or longer-term adverse neurologic effects, suggests that randomized trials of multiple courses of betamethasone in premature infants should be considered.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was partially supported by National Institutes of Health grant K-23 DC 006229-02.

We thank Mark Orlando, PhD, Kathleen Merle, MS, Todd M. Gibson, AuD, Teri D. Holt, MS, Matthew Macdonald, AuD, Lynette McRae, MA, Diane S. Puccia, MA, and Catherine Papso Seeger, MS, for performing ABR on premature infants. We also thank Kristina Mossgraber for collecting maternal information.

Abbreviations

- ABR

auditory brainstem evoked response

- RDS

respiratory distress syndrome

Footnotes

The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Matthews SG. Antenatal glucocorticoids and programming of the developing CNS. Pediatr Res. 2000;47:291–300. doi: 10.1203/00006450-200003000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dunlop SA, Archer MA, Quinlivan JA, Beazley LD, Newnham JP. Repeated prenatal corticosteroids delay myelination in the ovine central nervous system. J Matern Fetal Med. 1997;6:309–313. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6661(199711/12)6:6<309::AID-MFM1>3.0.CO;2-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Uno H, Lohmiller L, Thieme C, et al. Brain damage induced by prenatal exposure to dexamethasone in fetal rhesus macaques. I. Hippocampus. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1990;53:157–167. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(90)90002-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Antonow-Schlorke I, Kuhn B, Muller T, et al. Antenatal betamethasone treatment reduces synaptophysin immunoreactivity in presynaptic terminals in the fetal sheep brain. Neurosci Lett. 2001;297:147–150. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(00)01605-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schwab M, Antonow-Schlorke I, Kuhn B, et al. Effect of antenatal betamethasone treatment on microtubule-associated proteins MAP1B and MAP2 in fetal sheep. J Physiol. 2001;530:497–506. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.0497k.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Slotkin TA, Zhang J, McCook EC, Seidler FJ. Glucocorticoid administration alters nuclear transcription factors in fetal rat brain: implications for the use of antenatal steroids. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1998;111:11–24. doi: 10.1016/s0165-3806(98)00115-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Anonymous. Antenatal corticosteroids revisited: repeat courses. NIH Consensus Statement. 2000;17:1–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spinillo A, Viazzo F, Colleoni R, Chiara A, Maria Cerbo R, Fazzi E. Two-year infant neurodevelopmental outcome after single or multiple antenatal courses of corticosteroids to prevent complications of prematurity. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191:217–224. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2003.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Baud O, Foix-L’Helias L, Kaminski M, et al. Antenatal glucocorticoid treatment and cystic periventricular leukomalacia in very premature infants. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:1190–1196. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199910143411604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kumar P, Seshadri R. Neonatal morbidity and growth in very low birth-weight infants after multiple courses of antenatal steroids. J Perinatol. 2005;25:698–702. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7211393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moller AR, Jannetta PJ, Moller MB. Neural generators of brainstem evoked potentials: results from human intracranial recordings. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1981;90:591–596. doi: 10.1177/000348948109000616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hecox K, Burkard R. Developmental dependencies of the human brainstem auditory evoked response. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1982;388:538–556. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1982.tb50815.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Amin SB, Orlando MS, Dalzell LE, Merle KS, Guillet R. Morphological changes in serial auditory brain stem responses in 24 to 32 weeks’ gestational age infants during the first week of life. Ear Hear. 1999;20:410–418. doi: 10.1097/00003446-199910000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Born J, Schwab R, Pietrowsky R, Pauschinger P, Fehm HL. Glucocorticoid influences on the auditory brain-stem responses in man. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1989;74:209–216. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(89)90007-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Amin SB, Orlando MS, Dalzell LE, Merle KS, Guillet R. Brainstem maturation after antenatal steroids exposure in premature infants as evaluated by auditory brainstem-evoked response. J Perinatol. 2003;23:307–311. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7210898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Amin SB, Ahlfors C, Orlando MS, Dalzell LE, Merle KS, Guillet R. Bilirubin and serial auditory brainstem responses in premature infants. Pediatrics. 2001;107:664–670. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.4.664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aghajafari F, Murphy K, Matthews S, Ohlsson A, Amankwah K, Hannah M. Repeated doses of antenatal corticosteroids in animals: a systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186:843–849. doi: 10.1067/mob.2002.121624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guinn DA, Atkinson MW, Sullivan L, et al. Single vs weekly courses of antenatal corticosteroids for women at risk of preterm delivery: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2001;286:1581–1587. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.13.1581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dobbing J. The later growth of the brain and its vulnerability. Pediatrics. 1974;53:2–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.French NP, Hagan R, Evans SF, Godfrey M, Newnham JP. Repeated antenatal corticosteroids: size at birth and subsequent development. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;180:114–121. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(99)70160-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aghajafari F, Murphy K, Willan A, et al. Multiple courses of antenatal corticosteroids: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;185:1073–1080. doi: 10.1067/mob.2001.117635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Doyle KJ, Kong YY, Strobel K, Dallaire P, Ray RM. Neonatal middle ear effusion predicts chronic otitis media with effusion. Otol Neurotol. 2004;25:318–322. doi: 10.1097/00129492-200405000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]