Abstract

Urogenital schistosomiasis, Schistosoma haematobium worm infection, afflicts millions of people with egg-triggered, fibrotic bladder granulomata. Despite the significant global impact of urogenital schistosomiasis, the mechanisms of bladder granulomogenesis and fibrosis are ill defined due to the prior lack of tractable animal models. We combined a mouse model of urogenital schistosomiasis with macrophage-depleting liposomal clodronate (LC) to define how macrophages mediate bladder granulomogenesis and fibrosis. Mice were injected with eggs purified from infected hamsters or vehicle prepared from uninfected hamster tissues (xenoantigen and injection trauma control). Empty liposomes were controls for LC: 1) LC treatment resulted in fewer bladder egg granuloma-infiltrating macrophages, eosinophils, and T and B cells, lower bladder and serum levels of eotaxin, and higher bladder concentrations of IL-1α and chemokines (in a time-dependent fashion), confirming that macrophages orchestrate leukocyte infiltration of the egg-exposed bladder; 2) macrophage-depleted mice exhibited greater weight loss and bladder hemorrhage postegg injection; 3) early LC treatment postegg injection resulted in profound decreases in bladder fibrosis, suggesting differing roles for macrophages in fibrosis over time; and 4) LC treatment also led to egg dose-dependent mortality, indicating that macrophages prevent death from urogenital schistosomiasis. Thus, macrophages are a potential therapeutic target for preventing or treating the bladder sequelae of urogenital schistosomiasis.—Fu, C.-L., Odegaard, J. I., Hsieh, M. H. Macrophages are required for host survival in experimental urogenital schistosomiasis.

Keywords: clodronate

Schistosoma haematobium has infected over 112 million people worldwide, making it the most prevalent schistosome species for humans (1). Bladder fibrosis caused by chronic S. haematobium infection, also known as urogenital schistosomiasis, accounts for 10 million cases of hydronephrosis and 150,000 deaths annually due to urinary tract obstruction-induced renal failure (1). Despite the tremendous human impact of S. haematobium infection, our understanding of the underlying mechanisms of urogenital schistosomiasis and the host response remains inadequate. Much of this lack of knowledge is due to the historical dearth of good mouse models for urogenital schistosomiasis. To address this scientific need, we developed the first tractable mouse model of urogenital schistosomiasis (2). In this model, S. haematobium eggs are injected into the mouse bladder wall. This results in rapid infiltration of the mouse bladder by leukocytes with subsequent formation of granulomata that are reminiscent of human urogenital schistosomiasis. Although macrophages and epithelioid cells (activated macrophages) are the defining cell types of all granulomata, regardless of inciting agent, the mechanistic roles of these cells in the bladder sequelae of urogenital schistosomiasis are largely unknown.

We hypothesized that macrophages play a central role in schistosomal bladder pathogenesis. In order to elucidate the contributions of macrophages to the development of S. haematobium egg-induced bladder granulomata and related pathophysiology, we combined our mouse model of urogenital schistosomiasis with the use of the macrophage-depleting agent liposomal clodronate (LC). Herein, we show, through this conditional macrophage-depletion approach, that macrophages are essential for starting and directing the immunopathology of urogenital schistosomiasis. Macrophage depletion at different times postegg exposure resulted in varying fibrotic outcomes, indicating that these leukocytes mold fibrosis in a temporally dependent fashion. Strikingly, macrophages play a host-protective role in this setting because depletion of these cells results in egg dose-dependent mortality. These data demonstrate that macrophages are critical for host survival during the acute bladder phase of urogenital schistosomiasis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethics statement

All animal work was conducted according to relevant U.S. and international guidelines. Specifically, all experimental procedures were carried out in accordance with the Administrative Panel on Laboratory Animal Care (APLAC) protocol and the institutional guidelines set by the Veterinary Service Center at Stanford University (Animal Welfare Assurance A3213-01 and USDA License 93-4R-00). Stanford APLAC and institutional guidelines are in compliance with the U.S. Public Health Service Policy on Humane Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. The Stanford APLAC approved the animal protocol associated with the work described in this publication.

Mice

Seven to 8-wk-old female C57BL/6 mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME, USA). All experimental procedures were carried out in accordance with the APLAC protocol and the institutional guidelines set by the Veterinary Service Center at Stanford University.

S. haematobium egg isolation

S. haematobium-infected Lakeview Golden (LVG) hamsters were obtained from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Schistosomiasis Resource Center of the U.S. NIH (Biomedical Research Institute, Rockville, MD, USA). The hamsters were killed at the point of maximal liver and intestinal Schistosoma egg levels (18 wk postinfection) (3), at which time livers and intestines were minced, homogenized in a Waring blender, resuspended in 1.2% NaCl containing antibiotic-antimycotic solution (100 U penicillin, 100 µg/ml streptomycin, and 0.25 µg/ml amphotericin B; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), passed through a series of stainless steel sieves with sequentially decreasing pore sizes (450, 180, and 100 µm), and finally retained on a 45 µm sieve. To exclude possible confounding effects of hamster xenoantigens present in egg preparations, control injections were performed using similarly prepared liver and intestine lysates from age-matched, uninfected LVG hamsters (Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA, USA).

S. haematobium egg injection

Seven to 8-wk-old female C57BL/6 mice were anesthetized with isoflurane, midline lower-abdominal incisions were made, and the bladders exteriorized. Freshly prepared S. haematobium eggs (1000, 1500, or 3000 eggs in 50 µl PBS, experimental group) were injected submucosally into the anterior aspect of the bladder dome (4). Abdominal incisions were then closed with 4-0 VICRYL Suture (Ethicon, Somerville, NJ, USA), and the surgical sites were coated with topical antibiotic ointment.

Macrophage depletion

Macrophages were systemically depleted, or not depleted, through intraperitoneal injections of 200 μl LC or vehicle liposomes, or no i.p. injections. The following day, mice underwent bladder wall injection with 25 μl PBS, LC, or vehicle liposomes, each mixed with 25 μl S. haematobium eggs (1000, 1500, or 3000 eggs) or vehicle control (mock egg preparations of liver and intestinal tissues from uninfected hamsters). This approach helped maintain local depletion of macrophages. Depending on the planned experimental time course, mice were either killed 2 d later or subsequently administered combinations of LC or vehicle liposomes by intraperitoneal injection (200 μl), bladder wall injection (25 μl), and/or intravesical delivery (200 μl) to sustain macrophage depletion and then killed. Clodronate and vehicle liposomes (1 mg/ml solutions) were purchased from ClodronateLiposomes.com (Haarlem, The Netherlands).

Microultrasonography

On d 5 postbladder wall injection, mice were anesthetized using vaporized isoflurane, and their abdominal walls were depilated. Transabdominal images of the bladder were then obtained using a VisualSonics Vevo 770 high-resolution ultrasound microimaging system with an RMV 704 scanhead (40 MHz) (FujiFilm VisualSonics, Toronto, ON, Canada, and Small Animal Imaging Facility, Stanford Center for Innovation in In-Vivo Imaging, Stanford, CA, USA).

Bladder histopathologic analysis and collagen measurement

Mice were killed at various time points after bladder wall injection, and their bladders were processed for routine histology. Qualitative morphologic analyses were conducted on hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)- and Masson’s Trichrome-stained sections. Total collagen content was determined from fresh-frozen (70°C) bladder homogenates using the Sircol Soluble Collagen Assay Kit (Biocolor, Carrickfergus, United Kingdom) and Hydroxyproline Assay Kit (Chondrex Incorporated, Redmond, WA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Collagen concentrations were determined using standard curve analyses. Statistical comparisons were conducted using Student’s t tests.

Analysis of bladder-associated leukocytes

Antibodies

Anti-mouse-CD3-PE/Cy7 (clone 145-2C11; BioLegend, San Diego, CA, USA), anti-CD45 (B220)-FITC (clone RA3-6B2; BioLegend), anti-CD4-Pacific Blue (clone RM4-4; BioLegend), and anti-CD8 α-Alexa Fluor 647 (clone 53-6.7; BioLegend) were used to stain mouse lymphocyte subsets. Mouse myeloid cell subsets were stained by anti-F4/80-FITC (clone BM8; eBioscience, San Diego, CA, USA), anti-CD11b-APC-Cy7 (clone M1/70; BioLegend), anti-Ly-6G(Gr-1)-Pacific Blue (clone 1A8; BioLegend), anti-anti-Ly-6C-PerCP/Cy5.5 (clone HK1.4; BioLegend), anti-CD301-Alexa Fluor 647 (clone ER-MP23; Bio-Rad AbD Serotec, Raleigh, NC, USA), and anti-Siglec-F-PE-CF594 (clone E50-2440; BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA, USA).

Immunofluorescence staining and flow cytometry

Freshly excised bladders from egg- and vehicle-injected mice were minced and incubated with agitation in 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (Thermo Scientific HyClone, Waltham, MA, USA), 20 mM 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (pH 7), and 125 U/ml (1 mg/ml) collagenase VIII (Sigma-Aldrich) in RPMI 1640 medium for 1 h at 37°C (2). The tissue was then passed through a 70 µm nylon cell strainer to remove undigested tissue and macrocellular debris. After erythrocyte lysis (8.02 mg/ml NH4Cl, 0.84 mg/ml NaHCO3, and 0.37 mg/ml EDTA in distilled water), 106 cells were incubated with mouse anti-CD16/CD32 antibody (clone 2.4G2; BioLegend) for 20 min and then stained with fluorochrome-labeled antibodies for an additional 30 min at 4°C. Cells were analyzed using a BD LSRII flow cytometer and BD FACSDiva software (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA). Data were analyzed using FlowJo v7.2.4 (Tree Star, Ashland, OR, USA).

Cytokine analysis

Rapidly excised bladders were placed immediately on ice, minced in RNAlater solution (QIAGEN, Venlo, The Netherlands), and stored at −80°C. For protein analysis, 50 mg tissue was sonicated to homogeneity in 1 ml of ice-cold tissue extraction reagent (Biosource, San Diego, CA, USA) supplemented with 1 mM phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride. Clarified bladder extracts and serum samples were assayed using a mouse 26-plex cytokine kit (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Samples were read using a Luminex 200 (Luminex, Austin, TX, USA) with a lower cutoff of 100 beads per sample (Human Immune Monitoring Core, Stanford University).

Clodronate liposome treatment of thioglycollate-elicited macrophages

Seventy-two hours after intraperitoneal injection of 4% thioglycollate, 7- to 8-wk-old female C57BL/6 mice were administered intraperitoneal clodronate liposome or control liposomes. Twenty-four hours later, peritoneal exudate cells (PECs) were collected and stained with fluorochrome-labeled antibodies. Then, stained cells were analyzed by LSRII cytometer (Becton-Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). For clodronate-treated samples, statistical significance was assessed using a Student's 2-tailed t test to compare each dose to the PBS/liposome-injected control.

Limulus amebocyte lysate assays

The endotoxin activities of serum samples were determined using the LAL (limulus amebocyte lysate) Chromogenic Endotoxin Quantitation kit (catalog No.88282; Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL, USA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. In brief, serum samples were diluted to 1:10 with endotoxin-free water and then heated by placing the sample in a water bath or heat block at 70°C for a minimum of 15 min. Before adding the samples, the microplate was equilibrated in a heating block for 10 min at 37°C. Next, 50 μl of the standard or unknown heating samples were dispensed into the appropriate microplate well, and the plate was covered with the lid to incubate at 37°C; 5 min later, 50 μl LAL was added to each well. Then, the plate was shaken for 10 s and incubated at 37°C for 10 min. After exactly 10 min, 100 μl substrate solution was added to each well and incubated for another 6 min. The absorbance at 405–410 nm was measured on a plate reader after adding 50 μl 25% acetic acid to each well. The corrected absorbance was calculated by subtracting the average absorbance of the blank replicates from the average absorbance of all individual standard and sample replicates. The endotoxin concentrations in the serum samples were determined by the standard curve.

RESULTS

Macrophages are required for host survival after deposition of S. haematobium eggs in the bladder

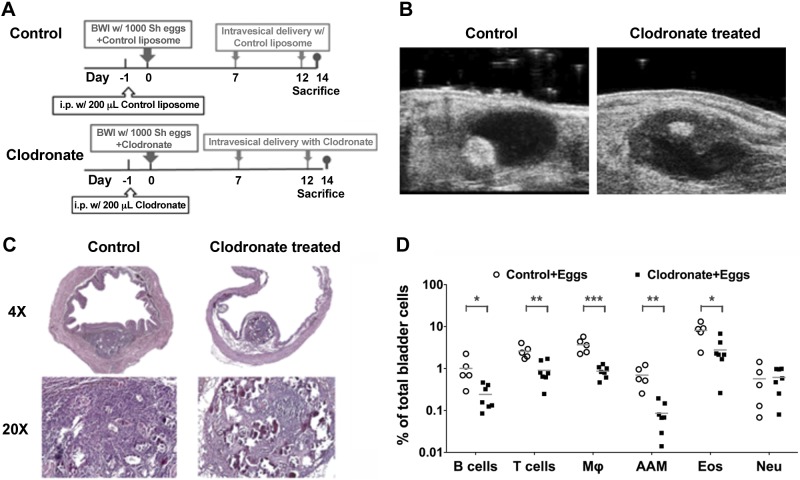

Using previously described methods, mice underwent bladder wall injection with S. haematobium eggs (2, 4). In order to deplete macrophages systemically and sustain low levels of local (bladder) macrophages, clodronate-containing or control liposomes were administered on d −1, 0, 7, and 12 as described in Fig. 1A. Successful induction of S. haematobium egg granulomata in injected mouse bladders was confirmed by transabdominal ultrasonography on d 5 postbladder wall injection (Fig. 1B). Granulomata in control liposome-treated bladders were readily identified as large, round echogenic masses in the bladder walls impinging into otherwise dark, urine-filled, ovoid bladder lumens. In contrast, LC-treated bladders had granulomata with small, echogenic cores and hypoechoic peripheral zones barely impinging into the bladder lumens.

Figure 1.

Macrophage depletion alters the host response to S. haematobium eggs in the bladder. A) Treatment protocol for mice undergoing egg injection and macrophage depletion. Mice received either control liposomes or LC given i.p. on d −1, bladder wall injection with control liposomes mixed with 1000 S. haematobium eggs, or LC mixed with 1000 eggs on d 0, followed by intravesical administration of control liposomes or LC on d 7 and 12. Mice were killed on d 14. B) Macrophage depletion of egg-injected bladders leads to sonographically apparent changes in granulomata. Mice underwent transabdominal microultrasonography on d 5 post-bladder wall injection (regimen shown in A). Granulomata are visible as highly echogenic masses within the ovoid bladder wall. Egg-injected bladders demonstrated smaller granulomata with hypoechoic peripheral zones after LC treatment. C) Macrophage depletion of egg-injected bladders leads to histologically apparent disruption in granuloma architecture. Typical histologic appearance of H&E staining of bladders 14 d postegg injection is shown. LC treatment of egg-injected bladders (regimen shown in A) leads to multiple paucicellular areas in granulomata and the lamina propria compared to controls. D) Macrophage depletion of egg-injected bladders leads to decreased granuloma infiltration by multiple nonmacrophage leukocyte subsets. Mice were killed on d 14 after egg injection and treatment with clodronate-loaded or control liposomes (regimen shown in A) and bladders harvested, homogenized into single cell suspensions, and subjected to flow cytometry specific for B cells, T cells, macrophages (Mϕ), AAMs, eosinophils (Eos), and neutrophils (Neu). Significance was assessed using a Student’s 2-tailed t test to compare both groups. Data shown are pooled from 3 experiments. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.005.

Macrophages generally recover from 4 to 6 d after clodronate treatment (5, 6). In order to suppress macrophage reconstitution in the bladder, LC was given transurethrally twice before the date on which mice were killed. Histologic analyses showed that macrophage depletion of egg-injected bladders disrupts the cellular and tissue architecture of granulomata (Fig. 1C). Specifically, LC-treated mice exhibited bladder granulomata with numerous paucicellular, edematous areas, consistent with the sonographic appearance of echogenic granuloma cores with hypoechoic peripheral regions. In contrast, control-injected bladders featured more densely cellular granulomata in the lamina propria, likewise consistent with ultrasound findings of densely echogenic lesions in the bladder wall. Thus, we utilized flow cytometry to determine whether granuloma cell populations differed between these 2 groups. Interestingly, we observed that proportions of alternatively activated macrophages (AAMs), macrophages in general, eosinophils, and T cells were significantly decreased after LC treatment (Fig. 1D).

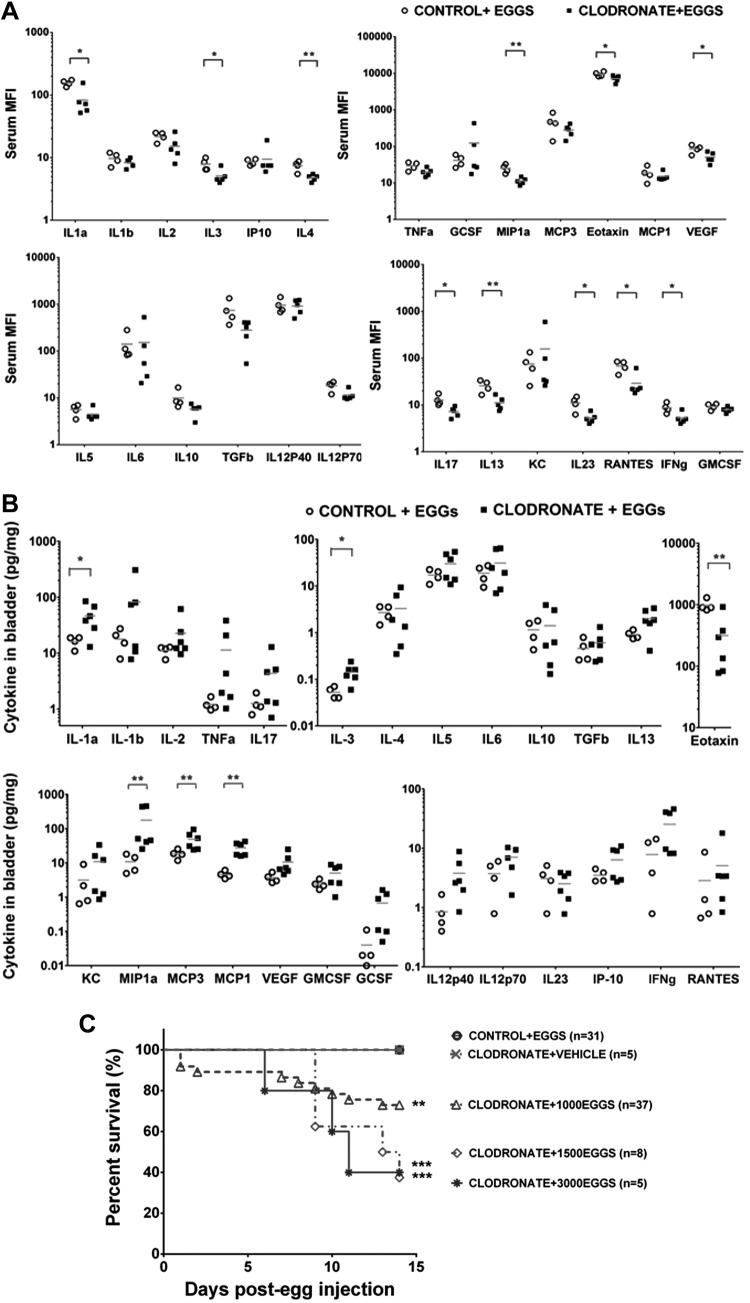

We postulated that systemic cytokine alterations, akin to those seen during sepsis, could be associated with clodronate-induced macrophage dysfunction in the context of schistosomal bladder pathogenesis. Mice were administered clodronate-containing or control liposomes on d −1, 0, 7, and 11 relative to bladder wall injection with 1000 eggs (essentially the same protocol as Fig. 1A), and sera were collected on d 14. Luminex analyses of sera revealed that clodronate treatment led to significant decreases in systemic levels of numerous cytokines, including IL-1α, IL-3, IL-4, IL-13, IL-17, IL-23, RANTES, IFN-γ, MIP-1α, eotaxin, and VEGF (Fig. 2A). In summary, macrophage depletion led to suppression of cytokines associated with leukocyte recruitment (RANTES, MIP-1α, and eotaxin), vascular repair (VEGF), and type 1 (IFN-γ), type 2 (IL-4 and IL-13), and Th17 (IL-17 and IL-23) immune responses. Thus, macrophage depletion led to a broad, complex effect beyond the conventional type 2 immune responses associated with schistosome innate immunity. Although macrophages are being specifically depleted, many of the reduced cytokines are known to be produced by other cells, e.g., lymphocytes, further supporting the concept that macrophages are required for their recruitment and activation. It is noteworthy that we did not observe either nonspecific immune skewing of cytokines or a cytokine storm.

Figure 2.

Macrophage depletion alters the cytokine and systemic physiologic response to S. haematobium eggs in the bladder. The systemic cytokine milieu of S. haematobium egg-exposed mice is altered by macrophage depletion. Mice were killed on d 14 after egg injection and treatment with clodronate-loaded or control liposomes (regimen shown in Fig. 1A) and sera harvested and subjected to 26-plex cytokine Luminex assays. Data shown are pooled from 2 independent experiments. *P < 0.05. A) Depletion of macrophages alters the bladder cytokine microenvironment. Mice manipulated as described in Fig. 1A were killed on d 14, and bladders were harvested, homogenized, and subjected to 26-plex cytokine Luminex assays. Significance was assessed using a Student’s 2-tailed t test to compare both groups. Data shown are pooled from 2 independent experiments. Horizontal bars indicate mean values. B) Macrophage depletion leads to rapid, single S. haematobium egg dose-dependent mortality. Mice underwent intraperitoneal injection with liposomes and bladder wall injection with liposomes mixed with different doses of S. haematobium eggs as the regimen described in (A). Student’s 2-tailed t test to compare each dose to the Control liposome-injected control was performed. Data shown are pooled from 7 experiments. C) Macrophage depletion leads to rapid, single S. haematobium egg dose-dependent mortality. Mice underwent intraperitoneal injection with liposomes and bladder wall injection with liposomes mixed with different doses of S. haematobium eggs as the regimen described in (A). Student’s 2-tailed t test to compare each dose to the Control liposome-injected control was performed. Data shown are pooled from 7 experiments. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.005.

Eotaxin was decreased in both the circulation (Fig. 2A) and bladders (Fig. 2B) of macrophage-depleted, egg-injected mice. Interestingly, macrophage depletion led to increases in bladder levels of IL-1α, IL-3, MCP-1, MCP-3, and MIP-1α. Moreover, the sera of macrophage-depleted, egg-injected mice featured suppression of several cytokines that were not decreased in bladder tissue, namely IL-1α, IL-13, IL-17, IL-23, RANTES, and MIP-1α. This suggests that the tissue context in which egg antigens are encountered results in disparate cytokine responses. This may reflect a “division of labor” among various anatomic compartments of a host dealing with schistosome infections.

Strikingly, the early administration of systemic and subsequent intravesical LC after a single, large egg dose (3000 eggs) caused death in 60% of mice (Fig. 2C). LC treatment of mice receiving lower egg doses (1000 eggs) resulted in less overall mortality. In contrast, no deaths occurred among egg-injected mice treated with control liposomes or control vehicle-injected mice treated with LC. Thus, macrophages are critical to host survival after bladder exposure to S. haematobium eggs.

Macrophage depletion alters sterile peritonitis-associated leukocyte infiltration

Given the dramatic phenotype seen following clodronate treatment, we next sought to confirm, through another experimental approach, whether clodronate liposome induces apoptosis of cells other than macrophages. intraperitoneal injection of thioglycollate is widely used to elicit sterile leukocyte infiltration of the peritoneal cavity (7). PECs were isolated by peritoneal lavage of mice 4 d after they were injected with thioglycollate and 24 h after exposure to clodronate liposome. PECs were then stained and analyzed by flow cytometry (Supplemental Fig. 1). As expected, macrophages were efficiently depleted by clodronate. Except for neutrophils, almost all cell types were decreased after clodronate exposure. However, the magnitude of nonmacrophage leukocyte depletion was much lower than that of macrophages and statistically insignificant (except for CD8+ T cells). We speculate that the depletion of macrophages by clodronate may decrease local levels of chemokines and thereby inhibits chemokine recruitment of nonmacrophage leukocytes to tissues where macrophages are present.

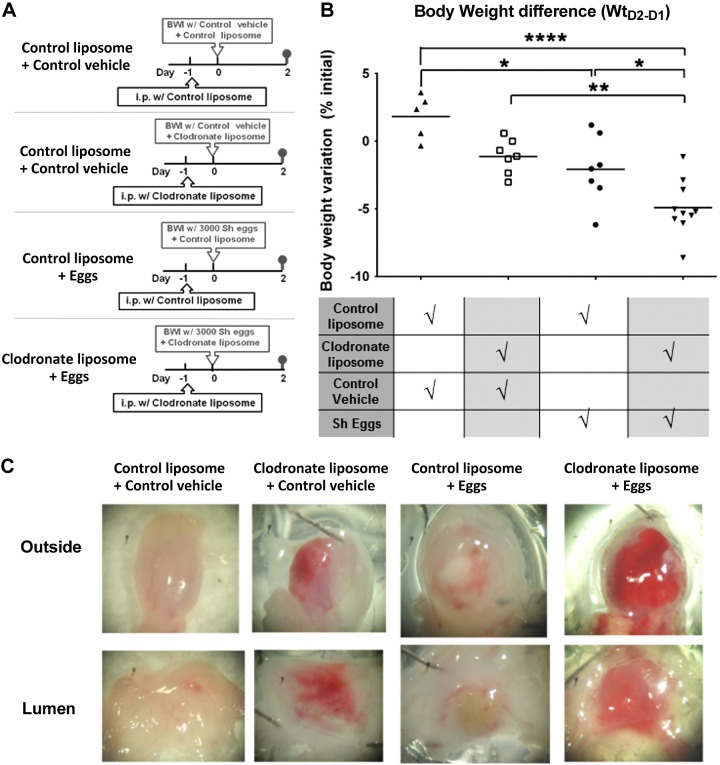

Macrophages modulate acute pathophysiology of the S. haematobium egg-exposed bladder

To further investigate the role of macrophages in host survival early after bladder contact with S. haematobium eggs, we shortened the regimen of LC treatment as described in Fig. 3A and examined acute postegg injection-induced changes in body weight and bladder morphology. Body weights on the first postoperative day decreased by similar levels across treatment groups (bladder wall injection with eggs or control vehicle mixed with LC or vehicle liposomes; data not shown). However, compared to controls, clodronate-treated, egg-injected mice exhibited significant weight loss on postoperative d 2 relative to d 1 (Fig. 3B). Macroscopically, extensive erythematous and hemorrhagic areas were apparent on the serosal and luminal sides of bladders from LC-treated, egg-injected mice (Fig. 3C). The bladders of LC-treated, control vehicle-injected mice merely showed mild erythema and hemorrhage. In contrast, the bladders of control liposome-treated, egg-injected mice featured only faint serosal erythema and did not exhibit hemorrhage. Histologic analyses of the bladders of LC-treated, egg-injected mice demonstrated severe edema and hemorrhage in areas adjacent to granulomata and underlying urothelia (Fig. 3D). The urothelia in these areas were frequently ulcerated and fragmented. In contrast to the catastrophic loss of tissue integrity seen in clodronate-treated, egg-injected mice, the urothelia from LC-treated, control vehicle-injected mice were intact and much less hemorrhagic (Fig. 3D); similar findings were observed in control liposome-treated, egg-injected mice (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Macrophages preserve bladder integrity and prevent weight loss after acute bladder exposure to S. haematobium eggs. A) Treatment protocol for mice undergoing egg injection and short-term macrophage depletion. Mice received either control liposomes or LC given intraperitoneally on d −1, bladder wall injection with control liposomes mixed with 3000 S. haematobium eggs, LC mixed with vehicle control (mock egg solution prepared from uninfected hamster tissues), or LC mixed with 3000 eggs on d 0. Mice were killed on d 2. B) Macrophages prevent acute weight loss following bladder exposure to S. haematobium eggs. Mice manipulated as described in (A) were weighed 1 and 2 d following bladder wall injection. Significance was assessed using 1-way ANOVA analysis. Data shown are pooled from 4 experiments. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.005. Horizontal bars indicate mean values. C) Macrophages preserve gross tissue integrity following bladder exposure to S. haematobium eggs. Representative photographs are shown of bladder explants taken 2 d after bladder wall injection of mice manipulated as described in (A). Explants have been bivalved, gently stretched open, and pinned down. Representative serosal and luminal views are shown. Data are representative of 1 of 4 independent experiments. D) Macrophages preserve microscopic tissue integrity following bladder exposure to S. haematobium eggs. Representative micrographs of H&E-stained sections of bladder explants obtained 2 d after bladder wall injection of mice manipulated as described in (A). Data are representative of 1 of 4 independent experiments. E) Depletion of macrophages alters the bladder cytokine microenvironment. Mice manipulated as described in (A) were killed on d 2, and bladders were harvested, homogenized, and subjected to 26-plex cytokine Luminex assays. Significance was assessed using a Student’s 2-tailed t test to compare both groups. Data shown are pooled from 2 independent experiments. *P < 0.05. Horizontal bars indicate mean values. F) Endotoxemia develops in macrophage-depleted, egg-injected mice. Sera were collected 2 d postegg or vehicle injection from mice that underwent clodronate or control liposome treatment (see A). The sera were subjected to LAL assays. Significance was assessed using 1-way ANOVA analysis. Data shown are pooled from 2 experiments. *P < 0.05. Horizontal bars indicate mean values.

Next, we assessed whether the cytokine microenvironment in the acutely S. haematobium egg-exposed bladder was altered by the depletion of macrophages. Twenty-six cytokines in total bladder homogenates were measured by Luminex assays 2 d following bladder injection (Fig. 3E). Depletion of macrophages in egg-injected mice led to reductions in multiple cytokines and growth factors relative to control liposome-treated, egg-injected mice, including proinflammatory cytokines (IL-1β), type 1 cytokines (IFN-γ and IL-2), type 2 cytokines (IL-3, IL-4, and eotaxin), and growth factors (VEGF). Decreases in cytokines were mediated by clodronate reduction of egg-induced macrophage activity because cytokine levels in the bladders of clodronate-treated, egg-injected mice were comparable to those of clodronate-treated, control vehicle-injected mice (data not shown). Interestingly, monocyte-recruiting chemokines (keratinocyte chemoattractant [KC, also known as CXCL1] MIP-1α, and MCP-3) remained at equivalent levels in macrophage-depleted, egg-injected mice as compared to control liposome-treated, egg-injected mice. Two of these chemokines, MIP-1α and MCP-3, were increased in the bladder at 14 d postbladder wall injection (Fig. 2B), indicating a time-dependent aspect to the expression of these chemokines. A number of cytokines were decreased in both the d 14 postinjection circulation (Fig. 2A) and d 2 postinjection bladders (Fig. 3E) of macrophage-depleted, egg-injected mice (e.g., IL-3, IL-4, eotaxin, VEGF, and MIP-1α), representing factors important for type 1 (IFN-γ) and type 2 immunity (IL-4 and eotaxin) and vascular repair (VEGF). However, numerous cytokines were decreased selectively in the d 2 postinjection bladder, including IL-1β and IL-2. These cytokines did not feature altered expression in the d 14 postinjection bladder, again emphasizing the dynamic temporal kinetics of expression of bladder cytokines following egg exposure. Importantly, mice injected with control vehicle combined with either control liposomes or LC did not demonstrate differences in bladder cytokine levels relative to each other, excluding a nonspecific effect of liposomes, whether “empty” or loaded with clodronate, on the noninflamed bladder (i.e., not egg exposed; data not shown).

The combination of weight loss, decreased systemic cytokine secretion, and egg-induced mortality among clodronate- vs. control-treated mice led us to suspect that macrophage depletion-associated cytokine dysregulation was contributing to sepsis. We hypothesize that disruption of the bladder barrier is a mechanism for bacterial translocation from the urine in the bladder lumen into the circulation. This results in leakage of LPS into the circulation (endotoxemia), thereby causing sepsis. Thus, we next investigated whether macrophage-depleted, egg-injected animals developed endotoxemia. Sera were collected 2 d postegg or postvehicle injection from mice that underwent clodronate or control liposome treatment (Fig. 3A). The sera were subjected to LAL assays, which revealed that systemic endotoxin levels were significantly higher among surviving, macrophage-depleted, egg-injected mice relative to macrophage-depleted, vehicle-injected mice as well as control liposome-treated, egg-injected mice (Fig. 3F).

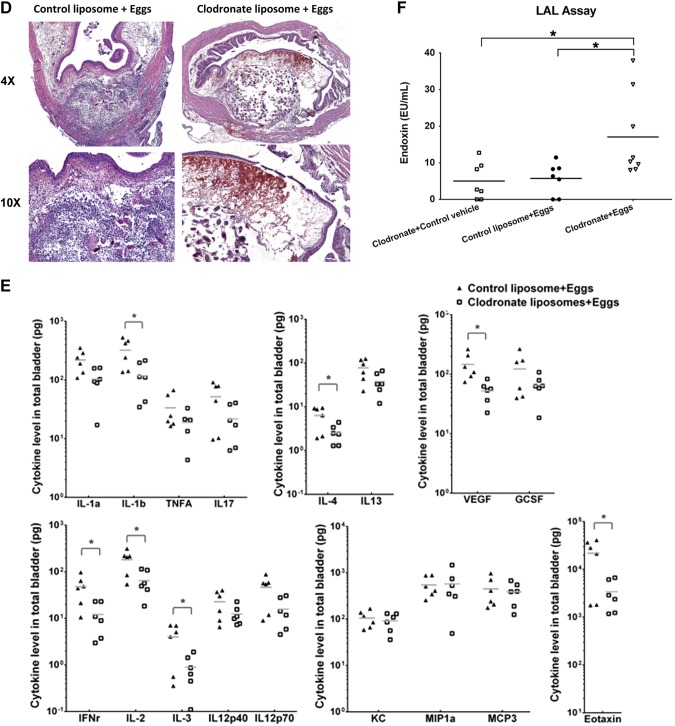

Macrophages are necessary for the fibrotic response to S. haematobium eggs

Macrophages are found in close proximity to collagen-producing myofibroblasts (8, 9) and indisputably play a key role in the fibrosis of organs other than the bladder (10). Given this body of literature and our observations that the local bladder microenvironment is modulated by macrophage depletion and the absence of macrophages results in increased mortality of S. haematobium egg-exposed mice, we next assessed whether macrophages modulate schistosomal bladder fibrosis, a tissue response that may affect host survival in the face of S. haematobium egg deposition.

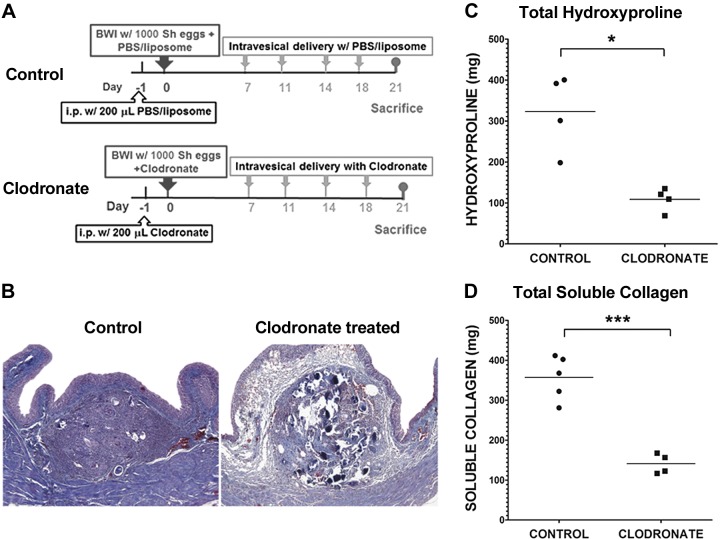

Egg-injected mice were treated with control or clodronate-loaded liposomes as described in Fig. 4A. Masson’s Trichrome staining revealed that in control liposome-exposed, egg-injected bladders, mature collagen was demonstrable throughout granulomata with variable extension into the surrounding bladder tissue by d 14 postegg injection (Fig. 4B). These control-injected bladders exhibited dense collagen staining in fibrotic granulomata within the lamina propria. However, there was sparse collagen staining in the granulomata and surrounding regions of lamina propria in LC-injected bladders. Accordingly, total bladder hydroxyproline (Fig. 4C) and soluble collagen content (Fig. 4D) were markedly decreased in the clodronate- vs. control-treated bladders. Our data demonstrate that the depletion of macrophages directly alleviates the severity of S. haematobium egg-induced bladder fibrosis. Hence, macrophages are essential for progression of schistosomal bladder fibrosis.

Figure 4.

Macrophages are necessary for the fibrotic response to S. haematobium eggs in the bladder. A) Treatment protocol for mice undergoing egg injection and medium-term macrophage depletion. Mice underwent i.p. injection with control liposomes or LC on d −1, bladder wall injection with control liposomes mixed with 1000 S. haematobium eggs, or LC mixed with 1000 eggs on d 0, followed by intravesical administration of control liposomes or LC on d 7, 11, 14, and 18. Mice were killed on d 21. B) The spatial distribution of collagen in schistosomal bladder granulomata and the associated lamina propria is disrupted by depletion of macrophages. Masson’s Trichrome staining is shown of mouse bladders injected 21 d earlier with S. haematobium eggs and treated with either control liposomes or LC (see A). Data are representative of 1 of 2 independent experiments. C and D) Collagen deposition in S. haematobium egg-exposed bladders is suppressed by depletion of macrophages. Mice underwent bladder wall injection and treatment with either control liposomes or LC (see A). Twenty-one days after bladder wall injection, bladders were harvested and subjected to either soluble collagen (C) or hydroxyproline assays (D). Significance was assessed using a Student’s 2-tailed t test to compare both groups. Data shown are pooled from 2 independent experiments. *P < 0.05; ***P < 0.005. Horizontal bars indicate mean values.

Macrophages play differing roles over time in schistosomal bladder inflammation and fibrosis

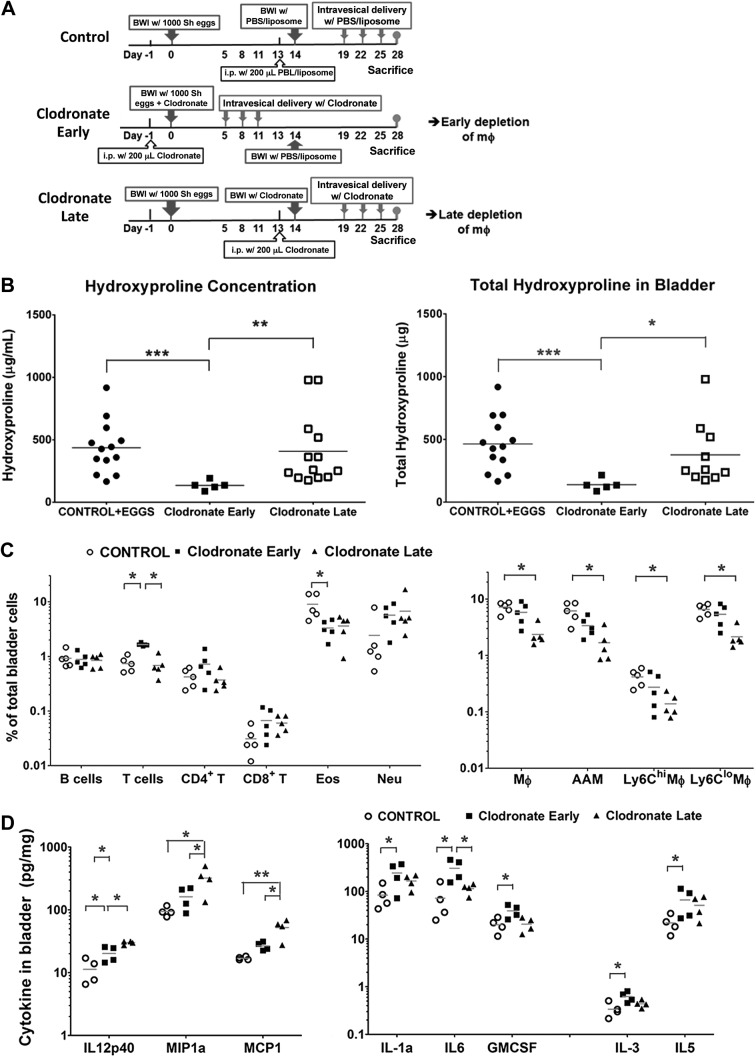

In our previous work, we showed the presence of CD68+ macrophages in schistosomal bladder granulomata that qualitatively appeared to increase in number over time (2). This suggests that differential macrophage activation in the bladder may indeed occur as a function of time. Thus, we investigated whether administering LC at different time points relative to egg injection (beginning just prior to egg injection vs. 2 wk later) could result in variable fibrosis outcomes (Fig. 5A). Through the use of hydroxyproline assays, we observed that LC treatment early after egg injection led to decreased fibrosis at d 28 postinjection compared to control liposome treatment (Fig. 5B). Importantly, we also found that, in contrast to early administration of LC, late administration after egg injection of the bladder wall does not alleviate fibrosis at 4 wk postegg injection (Fig. 5B). This indicates that macrophage regulation of schistosomal bladder fibrosis indeed evolves over time.

Figure 5.

Depletion of macrophages at different times after bladder exposure to S. haematobium eggs reveals distinct roles for these cells during the acute phase of inflammation-associated injury vs. the late fibrosis phase. A) Treatment protocol for mice undergoing egg injection and early vs. late macrophage depletion. Mice underwent bladder wall injection with control liposomes mixed with 1000 S. haematobium eggs on d 0, i.p. injection with control liposomes on d 13, bladder wall injection with control liposomes (PBS/liposome) on d 14, followed by intravesical administration of control liposomes on d 19, 22, and 25 (Control). Other mice (Clodronate Late) underwent the same regimen as Control mice except that they received LC rather than control liposomes and 1000 S. haematobium eggs on d 0 instead of vehicle controls. Clodronate Early mice began their intraperitoneal and intravesical LC schedule 2 wk earlier than Clodronate Late mice; these mice underwent intraperitoneal injection with clodronate on d −1, bladder wall injection with 1000 S. haematobium eggs mixed with clodronate on d 0, followed by intravesical administration of LC on d 5, 8, and 11, and bladder wall injection with PBS/liposome on d 14. All mice were killed on d 28. B) Early vs. late macrophage depletion after schistosome egg exposure differentially affects bladder fibrosis as assessed by hydroxyproline assays. Bladder hydroxyproline content was influenced differently by clodronate treatment depending on the timing of administration (see A), regardless of hydroxyproline concentration or total bladder hydroxyproline. Data shown are pooled from 2 independent experiments. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.005. Horizontal bars indicate mean values. C) Early vs. late macrophage depletion after schistosome egg exposure differentially affects bladder infiltration by leukocyte subsets. Single cell suspensions were prepared from the bladders of mice manipulated as described in (A), stained with fluorochrome-labeled antibodies specific for different leukocyte subsets, and subjected to flow cytometry. The representation of various leukocyte subsets in bladders [B cells, T cells, CD+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, macrophages (Mϕ), AAMs, eosinophils (Eos), neutrophils (Neu), and Ly6Clo and Ly6Chi macrophages (Ly6Clo Mϕ and Ly6Chi Mϕ)] is shown expressed as a percentage of total bladder cells. Results were compared by 1-way ANOVA. Data shown are pooled from 2 independent experiments. *P < 0.05. D) Early vs. late macrophage depletion after schistosome egg exposure differentially affects bladder expression of cytokines. Homogenized bladder protein was prepared from mice manipulated as described in (A) and subjected to 26-plex cytokine Luminex assays. Only cytokines showing statistically significant differences in expression are shown. Data shown are pooled from 2 independent experiments. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01. Horizontal bars indicate mean values.

We then assessed how the timing of LC regimens modulates the cellular composition of granulomata. All macrophage lineages examined (CD301+CD11b+F4/80+Siglec-F−Gr-1− AAMs and Ly6Chi CD11b+F4/80+Siglec-F−Gr-1− and Ly6Clo CD11b+F4/80+Siglec-F−Gr-1− macrophages) were decreased in the bladders of mice administered clodronate beginning 2 wk postegg injection as compared to those given clodronate starting just prior to egg injection (Fig. 5C). Conversely, macrophage levels from all examined lineages recovered by d 28 in the bladders of mice receiving early LC treatment. Remarkably, compared to control-treated bladders, both early and late clodronate treatments resulted in lower proportions of bladder eosinophils (albeit only statistically significant for early treatment). However, bladder proportions of T cells were significantly higher in the early clodronate treatment group vs. controls as well as compared to the late clodronate treatment group. These changes were not reflected among CD4+ and CD8+ T cell subsets.

We next compared how the loss of macrophages at various times after egg exposure affects bladder cytokine levels. Macrophage-related chemokines, specifically MIP-1 and MCP-1, were significantly higher in the bladders of mice given clodronate late after egg exposure (Fig. 5D) than those of the liposomal control and early clodronate treatment groups. IL-12p40 also showed a similar pattern among the treatment groups. Proinflammatory cytokines, namely IL-1α, IL-6, and granulocyte macrophage-CSF, were increased in the bladders of mice administered clodronate around the time of egg exposure relative to those of the control liposome group (IL-1α and granulocyte macrophage-CSF) and of the control liposome and late clodronate treatment groups (IL-6). The type 2 cytokines IL-3 and IL-5 were also higher in the bladders of the mice exposed to clodronate around the time of egg injection compared to those of the control liposome group. The other 18 cytokines tested did not show any significant differences across the various treatment regimens (data not shown).

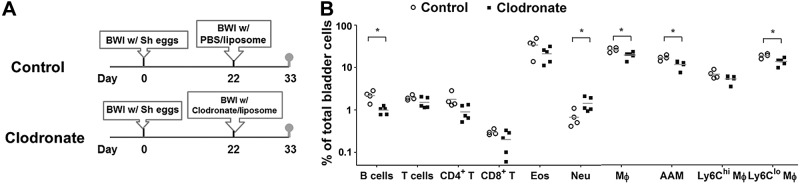

Unlike early initiation of clodronate administration relative to egg injection and killing of animals 2 wk after the final dose of clodronate (Clodronate Early, Fig. 5A), an interval that allows sufficient time for macrophage reconstitution to occur, the late commencement of clodronate treatment postegg injection followed by killing of animals 3 d after the last dose of clodronate (Clodronate Late, Fig. 5A) may not reveal whether delayed macrophage depletion leads to durable changes in the cellular composition of schistosomal bladder granulomata. Thus, we analyzed the cellular composition of bladders 11 d after clodronate treatment given 22 d postegg injection (Fig. 6A). This approach showed that the levels of bladder macrophages in mice administered clodronate late after egg exposure were lower than the control group (Fig. 6B). In particular, CD301+ AAMs and Ly6C-expressing low (Ly6Clo) macrophages were significantly lower following delayed clodronate administration. The proportions of bladder B lymphocytes in mice given clodronate late after egg injection were also lower than those of mice administered control liposomes. In contrast, bladder neutrophil representation was significantly higher in the late clodronate-treated group compared to the control group.

Figure 6.

Late macrophage depletion in S. haematobium egg-exposed mice results in durable alterations in bladder-infiltrating leukocyte populations, even after a period sufficient for macrophage reconstitution. A) Treatment protocol for mice undergoing egg injection and late macrophage depletion, followed by a period to permit macrophage reconstitution prior to killing. Mice underwent bladder wall injection with S. haematobium eggs and LC or control liposomes on d 1 and 22, respectively. All mice were killed on d 33. B) Late-infiltrating bladder macrophages play a crucial role in recruiting B cells and suppressing neutrophil influx following S. haematobium egg exposure. Single cell suspensions were prepared from the bladders of mice manipulated as described in (A). The cellular composition of these bladders was analyzed by flow cytometry [B cells, T cells, CD+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, macrophages (Mϕ), AAMs, eosinophils (Eos), neutrophils (Neu), and Ly6Clo and Ly6Chi macrophages (Ly6Clo Mϕ and Ly6Chi Mϕ)]. Significance was assessed using a Student’s 2-tailed t test to compare both groups. Data shown are pooled from 2 independent experiments. *P < 0.05. Horizontal bars indicate mean values.

DISCUSSION

Diseases featuring tissue fibrosis, the excessive and disorganized deposition of collagen in organs, account for nearly 45% of all deaths in the developed world (11). Numerous forms of tissue fibrosis also feature local infiltration by macrophages. Macrophages are almost always found in close proximity with collagen-producing myofibroblasts (8, 9), and the pathogenesis of fibrosis is tightly regulated by macrophages in many organs other than the bladder (10). Macrophage-associated fibrotic diseases are diverse and include idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, bleomycin-induced fibrosis, and schistosomiasis (12). However, the temporal relationships between macrophage activity and schistosomal bladder fibrosis, a common sequela of chronic S. haematobium infection, are inadequately defined. Herein, we tested the hypothesis that macrophages are crucial to schistosomal bladder granuloma formation and fibrosis by combining a recently described model of S. haematobium egg-induced bladder pathology with use of LC. The work presented in this study indicates that macrophages maintain bladder tissue integrity and prevent sepsis-associated mortality following S. haematobium egg deposition in the bladder. Macrophages execute these time-dependent functions by organizing granuloma formation, including orchestrating, via systemic and regional cytokine expression, which leukocytes infiltrate granulomata and how collagen accumulates in regions of associated extracellular matrix.

Despite the fact that S. haematobium is the most prevalent human schistosome worldwide, our understanding of the underlying mechanisms of infection and host responses remains inadequate. Specifically, the role of macrophages in different stages of initiation and the maintenance of schistosome-induced bladder fibrosis are not well defined. One of the main reasons for this dearth of knowledge is the lack of good mouse models for urogenital schistosomiasis. To address this scientific need, we developed the first tractable mouse model of urogenital schistosomiasis (2). In this model, purified S. haematobium eggs are injected into the mouse bladder wall. This results in rapid infiltration of the mouse bladder by leukocytes with subsequent formation of granulomata as observed in human urogenital schistosomiasis. The synchronous nature of this model bypasses the difficulties of predicting the exact onset of egg-induced granuloma formation and fibrosis following natural infection by skin penetration of cercariae. Our model can thereby accurately define the initiation of inflammation because it is triggered by bladder wall injection of eggs, and as a result, reliably forecasts the temporal kinetics of consequent fibrosis (2). We further leveraged the precision of our model by combining it with the use of the macrophage-depleting agent, LC, to inducibly deplete macrophages at various times after bladder wall injection. This approach allowed us to assess macrophage function during distinct phases of S. haematobium egg deposition-induced inflammation and fibrosis.

Liposome-encapsulated clodronate is one of the most effective agents for depleting mononuclear phagocytic populations in rodents. It has been widely applied to suppress macrophage activity in various models of autoimmune diseases (13), transplantation (14), neurologic disorders (15), and gene therapy (16). However, such treatment targets all mononuclear phagocytes, including monocytes, macrophages, and myeloid dendritic cells, and anti-inflammatory macrophages may also be depleted when LC is administrated systemically. In preliminary experiments, we found that multiple systemic (intraperitoneal) doses of LC led to very high mortality rates among S. haematobium egg-injected mice (data not shown). Conversely, multiple intravesical administrations of LC, without a preceding i.p. dose, failed to effectively deplete bladder macrophages (data not shown). Consequently, instead of exclusive, repeated systemic or local administration, we treated mice with a single i.p. dose of clodronate liposomes (to induce systemic macrophage depletion) followed by maintenance of local macrophage depletion by bladder wall injection (4) and intravesical delivery (17) of the agent. We used transabdominal microultrasonography to examine granuloma formation 5 d postbladder wall injection. This technique helped ensure that bladder wall injection was successful in all cases, and also facilitated in vivo observation of the early architectural structure of bladder granulomata after macrophage depletion. The resulting microsonographic findings constituted our initial evidence that depletion of macrophages could affect the formation of bladder granulomata during the initial inflammatory phase.

Exposure of phagocytes to clodronate liposomes results in apoptosis (18). Effective clearance of apoptotic cells by professional phagocytes (e.g., macrophages) requires Fas/CD95-induced chemokines to serve as “find-me” signals for these dying cells (19). Thus, the local increases in bladder MIP-1α and MCP-1 following early and late clodronate treatment may have been due to the following sequence of events: 1) clodronate-induced apoptosis; 2) release of apoptotic body-associated chemokines, maresins, resolvins, and lipoxins [reviewed by Buckley, Gilroy, and Serhan (20), and Serhan (21)]; and 3) chemotaxis of macrophages (in response to maresins, resolvins, lipoxins, and chemokines) to the bladder to eliminate apoptotic bodies (Fig. 2B). In contrast, clodronate treatment of egg-injected mice decreased bladder expression of the eosinophil chemoattractant eotaxin-1/CCL11 relative to control liposome-treated animals (Fig. 2B). This was associated with a decrease in bladder infiltration by eosinophils (Fig. 1D). Given the specificity of clodronate for phagocytes, we speculate that reduction of macrophages, one of the major eotaxin-producing cells, was responsible for these observed effects.

Duffield et al. (22) have described functionally distinct subpopulations of macrophages that coexist in tissues; these macrophages play critical roles in both the injury and recovery phases of inflammatory scarring in a carbon tetrachloride-induced liver fibrosis model. Their study showed that the deletion of macrophage populations either during injury or during repair and resolution has dramatically different effects on the overall fibrotic response. To our knowledge, the data presented herein are the first to delineate the distinct roles of macrophages in the initial inflammatory/injury phase and subsequent fibrosis phase of urogenital schistosomiasis. In that respect, our data have parallels to the findings of Duffield et al. (22). We also found that depletion of macrophages around the time of bladder wall injection markedly reduced hydroxyproline levels, a reflection of the severity of bladder fibrosis. In contrast, depletion of macrophages at late time points postegg injection did not ameliorate fibrosis (Fig. 5B). Conversely, Duffield et al. (22) reported that in carbon tetrachloride-induced liver fibrosis, depletion of macrophages during the recovery phase led to persistent and even worsened fibrosis compared to the control group. Differences between our findings and data derived from the carbon tetrachloride-liver fibrosis model may be due to numerous factors. First, Duffield et al. (22) specifically eliminated CD11b+ cells through a diphtheria toxin-based transgenic system, whereas clodronate depletes phagocytes, including, in our hands, CD301+ AAMs and Ly6Chi and Ly6Clo macrophages. This is consistent with our previous data demonstrating that multiple genes associated with macrophage activation and classical and alternative activation in particular, including those encoding for IL-4, arginase-1, IL-13 receptor α2, IL-10 receptor α, MPEG1, CHI3L3, and MRC1, are up-regulated in the bladder following S. haematobium egg injection (23). Regardless of whether Ly6Clo macrophages are derived from Ly6Chi macrophages and the lineage of classical vs. AAMs, these macrophage subsets may have counteracting influences on tissue fibrosis that are disrupted by clodronate exposure. Second, the lipoxin, maresin, and resolvin profile released by dying macrophages [reviewed by Buckley, Gilroy, and Serhan (20), and Serhan (21)] may vary between our study and the work of Duffield et al. (22) due to differences in the spectrum of killed macrophages. This could result in infiltration of damaged tissue by different macrophage subsets, with resulting dissimilarities in fibrosis resolution. Certainly, characterization of the potential role of lipoxins, maresins, and resolvins in our model is worthy of additional study. Third, the kinetics of carbon tetrachloride-induced liver fibrosis and the nature of its reliance on macrophages are likely different than those of S. haematobium egg-triggered bladder fibrosis. Finally, we speculate that strain differences (FVB/N vs. C57BL/6) may also contribute to variation in observed fibrosis phenotypes.

Another potential basis for differences between our data and findings of Duffield et al. (22) is the reconstitution of macrophages following and in between doses of macrophage-ablative agents. We speculate that there may also be differences in bladder vs. liver with regard to resident macrophage populations and the kinetics of tissue infiltration by circulating monocyte precursors. By eliminating blood monocytes with clodronate liposome and monitoring their repopulation, Sunderkötter et al. (5) showed that monocytes were maximally depleted 18 h after liposome application. However, monocytes (Ly-6Chi) began to reappear in the circulation sometime between 24 and 30 h and reached baseline counts before 48 h, although the steady-state distribution of Ly-6Clo vs. Ly-6C hi monocytes was not reestablished until between 4 and 7 d. Thus, in order to examine the possible effect of macrophage recovery on bladder granuloma cell composition after early and late depletion of macrophages, we decided to analyze bladder-associated cells more than 10 d after the final dose of clodronate. In the early clodronate treatment group, all bladder macrophage lineages, including Ly6Clo macrophages, were present at levels seen in the control liposome-treated group (Fig. 5C). However, when clodronate administration was delayed until 22 d after egg injection, levels of bladder Ly6Clo macrophages and AAMs were lower than control liposome-treated bladders, even 11 d after the final dose of clodronate (Fig. 6B). Ramachandran et al. (24) indicated that the level of Ly6Clo macrophages, so-called restorative macrophages, is highly correlated to resolution of carbon tetrachloride-induced liver fibrosis. Our data are consistent with this observation, given that delayed administration of clodronate after egg injection (2–3 wk), a period late in bladder fibrosis, decreased bladder representation of Ly6Clo macrophages at 3 and 11 d following the final dose of clodronate (Figs. 5C and 6B). The relative numbers of Ly6Clo macrophages may be increased compared to Ly6Chi macrophages in the late stages of schistosomal bladder fibrosis because delayed administration of clodronate following egg injection did not deplete Ly6Chi macrophages 11 d after the last dose (33 d postegg injection, Fig. 6B).

Although macrophages are widely recognized to have a profibrotic, pathogenic role in inflammation, they are also postulated to feature protective functions during Schistosoma oviposition in host tissues. This was true in our model because increased egg burdens in the absence of macrophages resulted in higher mortality (Fig. 2C). Given that LC treatment with a low egg dose (1000 eggs per mouse) decreased systemic levels of IL-1α, VEGF, IL-3, IL-4, IL-13, IL-17, IL-23, RANTES, IFN-γ, MIP-1α, and eotaxin compared to control liposome treatment (Fig. 2A), it is possible that these cytokines are critical in macrophage prevention of egg-induced death. We conjecture that the decreased bladder and systemic VEGF levels in egg-injected, macrophage-depleted mice contributed to host mortality, perhaps by abrogating host maintenance or restoration of vascular homeostasis, as evidenced by the extensive hemorrhage observed in these animals. Considering the known chemotactic functions of RANTES, MIP-1α, and eotaxin, it is plausible that reduction of levels of these chemokines was responsible for the observed decreased recruitment of T cells, macrophages, and eosinophils to the bladders of clodronate- vs. control liposome-treated mice. Depressed serum levels of numerous proinflammatory (IL-1α and IL-17), type 1 (IL-23 and IFN-γ), and type 2 (IL-3, IL-4, and IL-13) cytokines may reflect a generalized immunosuppression that contributed to egg-triggered, opportunistic endotoxemia (Fig. 3F), sepsis, and ultimately death (Fig. 2C).

Our approaches and the data derived from them have important pitfalls. First, our model of urogenital schistosomiasis features synchronous granulomata that evolve after the injection of a one-time bolus of eggs. This artificial technique does not recapitulate the kinetics of natural worm oviposition in the host bladder. Therefore, it is important not to over-interpret our findings regarding the temporal dependence of macrophage activity. Nevertheless, if anything, this renders some of our findings that much more surprising because a single injection of eggs into the bladder wall was enough to cause host death following macrophage depletion. Second, others have reported that LC depletes phagocytic cells besides macrophages (25, 26). Yet, LC exposure of thioglycollate-elicited PECs did not significantly deplete B or CD3+ T lymphocytes, eosinophils, or neutrophils, suggesting that the effects of clodronate on bladder infiltration by nonmacrophage leukocytes after egg injection were indirect (i.e., effects on macrophage-derived chemokine secretion) rather than due to direct cytotoxicity (Supplemental Fig. 1). Finally, reconstitution of macrophages after administration of clodronate can confound the interpretation of data obtained using this agent. However, we attempted to mitigate this potential confounder by administering repeated doses of clodronate for longer-term experiments. Even if macrophage reconstitution occurred despite multiple doses of clodronate, it likely decreased the magnitude of our observed effects when comparing clodronate to control treatment. Ergo, any macrophage reconstitution would lead to underestimates of the effects of clodronate. When we studied whether a generous period of macrophage reconstitution following clodronate treatment (11 d; Fig. 6) would result in restoration of a baseline profile of bladder leukocytes, there were residual effects on the B cell, neutrophil, and macrophage composition of these bladders, indicating that macrophage reconstitution has a limited impact on this aspect of schistosomal bladder pathogenesis.

We speculate that macrophages coordinate the infiltration of bladder granulomata with collagen and cells in order to rapidly sequester eggs and their toxins, which prevents uncontrolled, systemic immune derangements such as cytokine storm and undesirable physiologic effects, namely weight loss. Another conjectured function of the extracellular matrix and cells comprising bladder granulomata is to maintain tissue integrity in the face of egg toxins, complement, vascular dilatation and leakiness, and noxious leukocyte mediators that would otherwise disrupt the urothelia, blood vessels, and other critical bladder structures. Through these homeostatic functions, macrophages may also minimize tissue necrosis and thereby reduce the risk for bacterial superinfection, endotoxemia, and sepsis.

CONCLUSIONS

Our findings suggest that macrophages indeed choreograph the host response to S. haematobium eggs in the bladder. This central role in mediating fibrosis and leukocyte infiltration evolves over time. Furthermore, macrophages are essential for host survival and defense against the deposition of S. haematobium eggs, potentially through prevention of weight loss, sepsis, tissue compromise, and death.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by U.S. National Institutes of Health (Grant DK087895) (to M.H.H.). The authors gratefully acknowledge technical support from the Stanford Human Immune Monitoring Center with Luminex analysis. They are also indebted to De’Broski Herbert for providing useful comments regarding the manuscript.

Glossary

- AAM

alternatively activated macrophage

- APLAC

Administrative Panel on Laboratory Animal Care

- H&E

hematoxylin and eosin

- LAL

limulus amebocyte lysate

- LC

liposomal clodronate

- LVG

Lakeview Golden

- PEC

peritoneal exudate cell

Footnotes

This article includes supplemental data. Please visit http://www.fasebj.org to obtain this information.

REFERENCES

- 1.van der Werf M. J., de Vlas S. J., Brooker S., Looman C. W., Nagelkerke N. J., Habbema J. D., Engels D. (2003) Quantification of clinical morbidity associated with schistosome infection in sub-Saharan Africa. Acta Trop. 86, 125–139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fu C.-L., Odegaard J. I., Herbert D. R., Hsieh M. H. (2012) A novel mouse model of Schistosoma haematobium egg-induced immunopathology. PLoS Pathog. 8, e1002605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Botros S. S., Hammam O. A., El-Lakkany N. M., El-Din S. H., Ebeid F. A. (2008) Schistosoma haematobium (Egyptian strain): rate of development and effect of praziquantel treatment. J. Parasitol. 94, 386–394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fu C. L., Apelo C. A., Torres B., Thai K. H., Hsieh M. H. (2011) Mouse bladder wall injection. J. Vis. Exp. (53): e2523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sunderkötter C., Nikolic T., Dillon M. J., Van Rooijen N., Stehling M., Drevets D. A., Leenen P. J. (2004) Subpopulations of mouse blood monocytes differ in maturation stage and inflammatory response. J. Immunol. 172, 4410–4417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Danenberg H. D., Fishbein I., Gao J., Mönkkönen J., Reich R., Gati I., Moerman E., Golomb G. (2002) Macrophage depletion by clodronate-containing liposomes reduces neointimal formation after balloon injury in rats and rabbits. Circulation 106, 599–605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schleicher U., Bogdan C. (2009) Generation, culture and flow-cytometric characterization of primary mouse macrophages, in Macrophages and Dendritic Cells, Methods in Molecular Biology (Reiner N. E., ed.), Vol. 531 pp. 203–224, Humana Press, New York: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leicester K. L., Olynyk J. K., Brunt E. M., Britton R. S., Bacon B. R. (2004) CD14-positive hepatic monocytes/macrophages increase in hereditary hemochromatosis. Liver Int. 24, 446–451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Thompson R. W., Pesce J. T., Ramalingam T., Wilson M. S., White S., Cheever A. W., Ricklefs S. M., Porcella S. F., Li L., Ellies L. G., Wynn T. A. (2008) Cationic amino acid transporter-2 regulates immunity by modulating arginase activity. PLoS Pathog. 4, e1000023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wynn T. A., Barron L. (2010) Macrophages: master regulators of inflammation and fibrosis. Semin. Liver Dis. 30, 245–257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wynn T. A. (2008) Cellular and molecular mechanisms of fibrosis. J. Pathol. 214, 199–210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Barron L., Wynn T. A. (2011) Fibrosis is regulated by Th2 and Th17 responses and by dynamic interactions between fibroblasts and macrophages. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol. 300, G723–G728 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barrera P., Blom A., van Lent P. L., van Bloois L., Beijnen J. H., van Rooijen N., de Waal Malefijt M. C., van de Putte L. B., Storm G., van den Berg W. B. (2000) Synovial macrophage depletion with clodronate-containing liposomes in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 43, 1951–1959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carlos C. P., Mendes G. E., Miquelin A. R., Luz M. A., da Silva C. G., van Rooijen N., Coimbra T. M., Burdmann E. A. (2010) Macrophage depletion attenuates chronic cyclosporine A nephrotoxicity. Transplantation 89, 1362–1370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Katzav A., Bina H., Aronovich R., Chapman J. (2013) Treatment for experimental autoimmune neuritis with clodronate (Bonefos). Immunol. Res. 56, 334–340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hashimoto D., Chow A., Greter M., Saenger Y., Kwan W. H., Leboeuf M., Ginhoux F., Ochando J. C., Kunisaki Y., van Rooijen N., Liu C., Teshima T., Heeger P. S., Stanlev E. R., Frenette P. S., Merad M. (2011) Pretransplant CSF-1 therapy expands recipient macrophages and ameliorates GVHD after allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation. J. Exp. Med. 208, 1069–1082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.GuhaSarkar S., Banerjee R. (2010) Intravesical drug delivery: challenges, current status, opportunities and novel strategies. J. Control. Release 148, 147–159 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yang D.-M., Teng H. C., Chen K. H., Tsai M. L., Lee T. K., Chou Y. C., Chi C. W., Chiou S. H., Lee C. H. (2009) Clodronate-induced cell apoptosis in human thyroid carcinoma is mediated via the P2 receptor signaling pathway. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 330, 613–623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cullen S. P., Henry C. M., Kearney C. J., Logue S. E., Feoktistova M., Tynan G. A., Lavelle E. C., Leverkus M., Martin S. J. (2013) Fas/CD95-induced chemokines can serve as “find-me” signals for apoptotic cells. Mol. Cell 49, 1034–1048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Buckley C. D., Gilroy D. W., Serhan C. N. (2014) Proresolving lipid mediators and mechanisms in the resolution of acute inflammation. Immunity 40, 315–327 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Serhan C. N. (2014) Pro-resolving lipid mediators are leads for resolution physiology. Nature 510, 92–101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Duffield J. S., Forbes S. J., Constandinou C. M., Clay S., Partolina M., Vuthoori S., Wu S., Lang R., Iredale J. P. (2005) Selective depletion of macrophages reveals distinct, opposing roles during liver injury and repair. J. Clin. Invest. 115, 56–65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ray D., Nelson T. A., Fu C.L., Patel S., Gong D. N., Odegaard J. I., Hsieh M. H. (2012) Transcriptional profiling of the bladder in urogenital schistosomiasis reveals pathways of inflammatory fibrosis and urothelial compromise. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 6, e1912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ramachandran P., Pellicoro A., Vernon M. A., Boulter L., Aucott R. L., Ali A., Hartland S. N., Snowdon V. K., Cappon A., Gordon-Walker T. T., Williams M. J., Dunbar D. R., Manning J. R., van Rooijen N., Fallowfield J.A., Forbes S. J., Iredale J. P. (2012) Differential Ly-6C expression identifies the recruited macrophage phenotype, which orchestrates the regression of murine liver fibrosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, E3186–E3195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leenen P. J. M., Radosević K., Voerman J. S., Salomon B., van Rooijen N., Klatzmann D., van Ewijk W. (1998) Heterogeneity of mouse spleen dendritic cells: in vivo phagocytic activity, expression of macrophage markers, and subpopulation turnover. J. Immunol. 160, 2166–2173 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gommet C., Billecocq A., Jouvion G., Hasan M., Zaverucha do Valle T., Guillemot L., Blanchet C., van Rooijen N., Montagutelli X., Bouloy M., Panthier J. J. (2011) Tissue tropism and target cells of NSs-deleted rift valley fever virus in live immunodeficient mice. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 5, e1421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.