Abstract

Background

Although obesity and mental health disorders are two major public health problems in adolescents that affect academic performance, few rigorously designed experimental studies have been conducted in high schools.

Purpose

The goal of the study was to test the efficacy of the COPE (Creating Opportunities for Personal Empowerment) Healthy Lifestyles TEEN (Thinking, Emotions, Exercise, Nutrition) Program, versus an attention control program (Healthy Teens) on: healthy lifestyle behaviors, BMI, mental health, social skills, and academic performance of high school adolescents immediately after and at 6 months post-intervention.

Design

A cluster RCT was conducted. Data were collected from January 2010 to May of 2012 and analyzed in 2012–2013.

Setting/participants

A total of 779 culturally diverse adolescents in the U.S. Southwest participated in the trial.

Intervention

COPE was a cognitive–behavioral skills-building intervention with 20 minutes of physical activity integrated into a health course, taught by teachers once a week for 15 weeks. The attention control program was a 15-session, 15-week program that covered common health topics.

Main outcome measures

Primary outcomes assessed immediately after and 6 months post-intervention were healthy lifestyle behaviors and BMI. Secondary outcomes included mental health, alcohol and drug use, social skills, and academic performance.

Results

Post-intervention, COPE teens had a greater number of steps per day (p=0.03) and a lower BMI (p=0.01) than did those in Healthy Teens, and higher average scores on all Social Skills Rating System subscales (p-values <0.05). Alcohol use was 11.17% in the COPE group and 21.46% in the Healthy Teens group (p=0.04). COPE teens had higher health course grades than did control teens. At 6 months post-intervention, COPE teens had a lower mean BMI than teens in Healthy Teens (COPE=24.72, Healthy Teens=25.05, adjusted M= −0.34, 95% CI= −0.56, −0.11). The proportion of those overweight was significantly different from pre-intervention to 6-month follow-up (Chi square=4.69, p=0.03), with COPE decreasing the proportion of overweight teens, versus an increase in overweight in control adolescents. There were no differences in alcohol use at 6 months (p=0.06).

Conclusions

COPE can improve short- and more long-term outcomes in high school teens.

Trial registration

This study is registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov NCT01704768.

Introduction

Obesity and mental health disorders are two substantial public health problems that threaten the health outcomes and academic performance of adolescents.1,2 The prevalence rates of obesity and mental health/psychosocial problems are even higher in minority teens, with the two conditions often co-existing.3–6 Thirty-two percent of youth are now overweight (i.e., a gender and age-specific BMI at or above the 85th percentile) or obese (i.e., gender- and age-specific BMI at or above the 95th percentile).7 Obese teens are more likely to exhibit poor social skills and nutritional habits, inadequate academic performance, depression, stress, and anxiety than non-obese youth.8,9

Further, approximately one in four teens has a mental health disorder, yet <25% of the 15 million youth affected receive treatment.10,11 Multiple factors contribute to obesity in adolescents, including decreased physical activity, poor nutrition, and depression.12–16 Because of the time that youth spend in learning environments, schools are an outstanding venue to provide teens with skills to improve their healthy lifestyle behaviors, mental health, social skills, and academic performance.17

Few rigorously designed intervention studies have been conducted with high school adolescents to simultaneously target improvements in healthy lifestyle behaviors, psychosocial outcomes, and academic performance.18 Of those intervention studies conducted in high schools, the majority have targeted a single health outcome, such as substance abuse or depression. Therefore, it is largely unknown whether more-comprehensive health promotion programs also can be effective in improving adolescents’ health as well as their psychosocial skills and academic performance.19

Further, intervention studies with high school teens have several important limitations, including lack of attention control or comparison groups, small sample sizes, and large attrition rates (i.e., >20%).20,21 In addition, many of the adolescent intervention studies that have been conducted measured outcomes immediately after the intervention and at <6 months post-intervention, so it is unknown whether the interventions sustained their effects for a longer period of time.21 Recent systematic reviews of treatment and prevention studies for adolescent obesity conclude that more research is urgently needed in school-based settings, especially with culturally diverse groups.20–22

Another review noted that strong conclusions about the efficacy of school-based obesity prevention programs cannot be drawn because there are few published studies, and the ones that have been published have major methodologic flaws.23 The public health problems of obesity and psychosocial/mental health adverse outcomes along with health disparities among teens highlight the need for evidence-based interventions in high schools to improve their health and academic performance.

The primary aim of this cluster RCT was to test the short- and longer-term efficacy of the COPE (Creating Opportunities for Personal Empowerment) Healthy Lifestyles TEEN (Thinking, Emotions, Exercise, Nutrition) Program (referred to here as COPE), versus an attention control program (Healthy Teens), on the healthy lifestyle behaviors, BMI, psychosocial outcomes, social skills, and academic performance of high school adolescents aged 14–16 years. It was hypothesized that adolescents who received the COPE program would have healthier lifestyle behaviors and decreased BMI as well as improved mental health, social skills, and academic outcomes immediately following and at 6 months after the intervention than teens who received the attention control program.

Methods

Participants

Adolescents aged 14–16 years, primarily freshmen and sophomores, who were enrolled in required health education courses, were recruited during their classes in 11 high schools from two school districts in the Southwestern U.S. The choice of schools was designed to provide diversity across race/ethnicity as well as SES. Inclusion criteria consisted of: teens of any gender, ethnicity/race, or SES; teens who assented to participation with a custodial parent who gave consent for their teen to participate; and those who could read and speak English. Exclusion criteria consisted of teens with a medical condition that would prevent them from participating in the physical activity component of the program. The university’s IRB approved the study, and an independent data and safety monitoring board monitored the research. A certificate of confidentiality was obtained in order to obtain data relating to teen alcohol and illicit drug use.

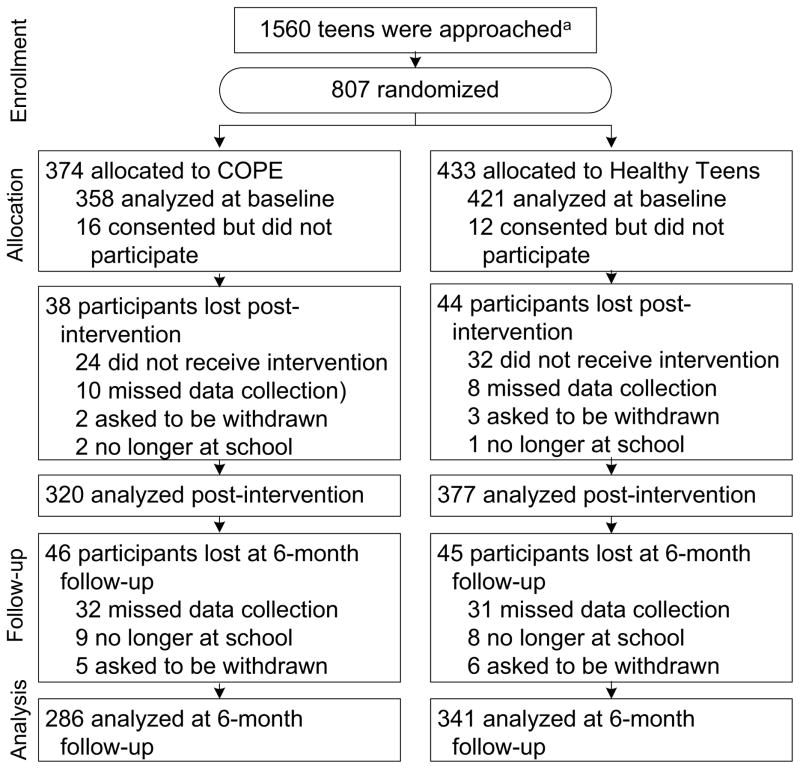

All teens in the selected health education courses in the 11 high schools were invited to participate in the study (Figure 1). Health is a required course for graduation in all 11 high schools that participated in this study. Research team members introduced the study to all students in each participating health class and sent consent/assent packets home with those teens who expressed interest in study participation. Teens who returned a signed assent and parent consent were enrolled in the study. All students in the health classes received either the COPE or Healthy Teens program; however, the study measures were obtained on only the students enrolled in the trial.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of school and participant selection

A total of 779 teens were enrolled in the study from January 2010 to December 2012. Teen demographic variables are described in Table 1. There were 521 (68.3%) that self-identified as Hispanic. Just over half of the sample was female (n=401, 51.5%).

Table 1.

Baseline findingsa and demographics, n (%) unless otherwise indicated

| Characteristic | n (%) | p-Value | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | COPE | Healthy Teens | |||||

| (N=779) | (n=358) | (n=421) | |||||

| Age, years, M (SD)b | 14.74 | (0.73) | 14.75 | (0.76) | 14.74 | (0.70) | 0.89 |

| Genderc | |||||||

| Female | 402 | (51.60) | 195 | (54.50) | 207 | (49.20) | 0.14 |

| Male | 377 | (48.40) | 163 | (45.50) | 214 | (50.80) | |

| Ethnicityc | |||||||

| Hispanic or Latino | 521 | (68.30) | 271 | (77.40) | 250 | (60.50) | 0.00 |

| Racec | |||||||

| American Native | 27 | (3.50) | 10 | (2.80) | 17 | (4.0) | 0.00 |

| Asian | 31 | (4.0) | 7 | (2.0) | 24 | (5.70) | |

| Black | 77 | (9.90) | 30 | (8.40) | 47 | (11.20) | |

| White | 110 | (14.10) | 31 | (8.70) | 79 | (18.80) | |

| Hispanic | 526 | (67.50) | 275 | (76.80) | 251 | (59.60) | |

| Otherd | 8 | (1.0) | 5 | (1.40) | 3 | (0.70) | |

| BMI, M (SD)b | 24.43 | (5.92) | 24.93 | (6.18) | 24.01 | (5.65) | 0.03 |

| CDC BMI Categoriesc | |||||||

| Underweight | 14 | (1.80) | 1 | (.30) | 13 | (3.10) | 0.02 |

| Healthy Weight | 433 | (55.60) | 196 | (54.70) | 237 | (56.30) | |

| Overweight | 148 | (19.0) | 72 | (20.10) | 76 | (18.10) | |

| Obese | 182 | (23.40) | 88 | (24.60) | 94 | (22.30) | |

| Unreported | 2 | (0.30) | 1 | (0.30) | 1 | (0.20) | |

| Steps per day, M (SD)b | 9975 | (5261) | 9990 | (5326) | 9959 | (5203) | 0.95 |

| Beck Youth Inventories, M (SD)b | |||||||

| Anxiety | 48.43 | (9.99) | 49.00 | (10.51) | 47.94 | (9.49) | 0.14 |

| Depression | 46.55 | (9.57) | 46.55 | (10.20) | 46.55 | (9.02) | 0.99 |

unadjusted Ms

t-test

Chi-Square

Other includes: Middle Eastern, Mexican/Irish/Cherokee/Caucasian, Erithrean, Mixed, Somali, Pakistani, and unreported

Design

This study was a prospective, blinded, cluster RCT that tested the efficacy of the COPE Program in improving the healthy lifestyle behaviors, BMI, psychosocial health, and academic performance of 779 high school teens. Schools within each of the two school districts were randomly assigned to receive either the COPE Program or the attention control Healthy Teens program. Random assignment of schools versus individual classrooms to study group was conducted in order to decrease the possibility of cross-group contamination between students in the same school, which would have threatened the study’s internal validity. Data were collected from January 2010 to December of 2012 and analyzed in 2012–2013. Teen participation in the study is delineated in Figure 1.

Interventions

The COPE program is a manualized 15-session educational and cognitive–behavioral skills-building program guided by Cognitive Theory, with physical activity as a component of each session. The COPE intervention was originally developed by the first author in 2002 and pilot-tested three times with white, Hispanic, and African-American adolescents as a group intervention in high school settings. COPE sessions are detailed in Table 2. Each session of COPE contains 15–20 minutes of physical activity (e.g., walking, dancing, kick-boxing movements), not intended as an exercise training program, but rather to build beliefs in the teens that they can engage in and sustain some level of physical activity on a regular basis.

Table 2.

COPE Content

| Session # | Session Content | Key Content in the COPE Intervention |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Introduction of the COPE Healthy Lifestyles TEEN program and goals. | |

| 2 | Healthy Lifestyles and the Thinking, Feeling, Behaving triangle. | CBSB |

| 3 | Self-esteem. Positive thinking/self-talk. | CBSB |

| 4 | Goal-setting; problem-solving | CBSB |

| 5 | Stress and Coping. | CBSB |

| 6 | Emotional and behavioral regulation. | CBSB |

| 7 | Effective communication. Personality and communication styles. | CBSB |

| 8 | Barriers to goal progression and overcoming barriers. Energy balance. Ways to increase physical activity and associated benefits. | CBSB and Physical Activity Information |

| 9 | Heart rate. Stretching. | Physical Activity information |

| 10 | Food groups and a healthy body. Stoplight diet: red, yellow, and green. | Nutrition information |

| 11 | Nutrients to build a healthy body. Reading labels. Effects of media and advertising on food choices. | Nutrition information |

| 12 | Portion sizes. “super size.” Influence of feelings on eating. | Nutrition information |

| 13 | Social eating. Strategies for eating during parties, holidays, and vacations. | Nutrition information |

| 14 | Snacks. Eating out. | Nutrition information |

| 15 | Integration of knowledge and skills to develop a healthy lifestyle plan; Putting it all together | CBSB |

CBSB, cognitive–behavioral skills building; COPE (COPE Healthy Lifestyles TEEN Program), Creating Opportunities for Personal Empowerment Healthy Lifestyles Thinking, Emotions, Exercise, Nutrition Program

Pedometers were used throughout the intervention in order to reinforce the physical activity education component of COPE. Students were asked to increase their step counts by 10% each week regardless of baseline levels and to keep track of their daily steps on a tracking sheet so they could calculate a weekly average and determine if they met their weekly goal. After a full-day training workshop on COPE, the teens’ high school health teachers integrated and taught the 15 COPE sessions once a week in their health course for 15 weeks. Teens received a COPE manual with homework activities for each of the 15 sessions that reinforced the content and skills in the program. A parent newsletter describing the content of the COPE program also was sent home with the teens four times during the course of the 15-week program, and the teens were instructed to review each newsletter with their parent(s) as part of their homework assignments.

The Healthy Teens program was designed as a 15-week attention control program to control for the time the health teachers in the COPE group spent delivering the experimental content to their students. Health teachers received a full-day training workshop on the Healthy Teens content. The content was manualized and focused on safety and common health topics/issues for teens, such as road safety, dental care, infectious diseases, immunizations, and skin care. Control teens also received a manual with homework assignments each week that focused on the topics being covered in class and were asked to review with his or her parent a newsletter that was sent home with the teens four times during the program.

The control program was administered in a format like that of the COPE intervention and included the same number and length of sessions as the experimental program, but there was no overlap of content between the two programs. Attention control students were provided with a pedometer for use only during the first week and post-intervention week (i.e., Week 16) in order to determine their average weekly steps for assessment purposes during those 2 weeks. COPE students, by contrast, used their pedometers and completed weekly step logs throughout the entire intervention period.

Assessment of Intervention Fidelity

Observers rated approximately 25% of the teachers’ intervention sessions using an observation instrument of intervention fidelity that was developed for use in the study. Inter-rater reliability of 90% for the fidelity observations between raters was maintained. In addition, teachers recorded the tasks accomplished in each intervention session as well as time spent on each task, impressions of the flow, and content and acceptance of the sessions in an intervention diary.

Outcomes Assessment

The primary outcomes were the adolescents’ healthy lifestyle behaviors as measured by physical activity that was captured by pedometer steps; the Healthy Lifestyles Behavior Scale (HLBS); and BMI. The pedometer used to measure steps (Yamex SW-200) is considered the standard in the healthcare and research industry due to its reliability and accuracy. The outcome of pedometer steps was measured immediately post-intervention. The HLBS is a self-report measure with 15 items that tap healthy behaviors (e.g., I exercise regularly; I talk about my worries or stressors) on a 5-point Likert scale that ranges from 1, strongly disagree to 5, strongly agree. The HLBS has construct validity and Cronbach alphas reported at ≥ 0.80.24 Secondary outcomes included depressive and anxiety symptoms, social skills, substance use, and academic performance. (i.e., grade in the health course).

Heights and weights were obtained to calculate the teens’ BMI. Height was measured with a stadiometer and weight was measured with a Tanita scale. Subscales of the Beck Youth Inventory II©, a widely used and valid and reliable instrument, were used to assess the teens’ self-reported depressive and anxiety symptoms over time.25 Social skills were measured by the Social Skills Rating System©, which includes valid and reliable subscales of students’ social behaviors that are objectively rated by teachers post-intervention.26 Substance use was measured by students’ reports using questions from the Youth Risk Behavior Survey.17

Academic performance was measured by the students’ health course grade obtained from school records. Acculturation, a variable that was included as a possible control variable because of the anticipated large number of Hispanic adolescents in this study, was measured with The Acculturation, Habits, and Interests Multicultural Scale for Adolescents (AHIMSA), which has established construct validity and a reliability27 with this sample of 0.86.

Data Analysis

Sample size for the study was based on a power analysis for teen outcomes based on published research and pilot data. A number of simulations were run to assess power for the omnibus ANOVA tests and the a priori comparison of between-group differences at each time point, varying both the class size and the intraclass correlation coefficient. The sample size was further increased by 25% to allow for losses to follow-up. Linear mixed models and repeated measures ANCOVAs with baseline measures entered as covariates were used to assess the study’s outcomes.

There were significant teen baseline differences between the groups on race/ethnicity (greater percentage of Hispanic teens in COPE); weight (higher BMI in COPE); acculturation (COPE teens had lower assimilation and greater integration and separation scores); and hours of TV watched on a school day (COPE teens watched more TV). Therefore, these variables were entered as covariates in the ANCOVA analyses. Repeated logistic regression models using generalized estimating equations (GEEs) were used to analyze the binary outcomes. Analyses were performed using all available data (i.e., intent to treat), including participants who subsequently dropped out of the study. Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS Proc Mixed and Proc Genmod, version 9.2.

Results

Approximately 50% of eligible teens participated in this study (Figure 1). Recruitment from the various schools ranged from 20.88% to 66.47%. Recruitment levels for Cohorts 1–3 were 44.85%, 44.78%, and 62.17%, respectively.

Immediate Post-intervention Outcomes

There was a significant difference between groups for physical activity as measured by daily pedometer steps (Table 3). COPE teens had significantly greater steps per day than did those in Healthy Teens (COPE M=13,681; Healthy Teens M= 9619). No self-reported differences existed on the HLBS (F1,669=0.49, p=0.48). There also was a significant difference between groups for BMI. The COPE teens had a lower mean BMI than those in Healthy Teens (COPE= 24.57, Healthy Teens= 24.77, adjusted M= −0.20 [95% CI= −0.35, −0.05]).

Table 3.

Outcomesa

| Outcome | COPE Estimate M (95% CI) | Healthy Teen Estimate M (95% CI) | Between-Group Differences (95% CI) | F Value or Chi-Square | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Steps per day | 13681 (11829, 15533) | 9619.17 (7832.45, 11406) | 4061.83 (1437, 6686.66) | 9.34b | 0.00 |

| BMI | |||||

| Post Intervention | 24.57 (24.46, 24.68) | 24.77 (24.67, 24.87) | −0.20 (−0.35, −0.05) | 6.69b | 0.01 |

| 6-Month Follow-up | 24.72 (24.55, 24.88) | 25.05 (24.90, 25.20) | −0.34 (−0.56, −0.11) | 8.43b | 0.00 |

| Social Skills Rating Scale: Subscales | |||||

| Cooperation | 15.50 (14.93, 16.06) | 14.59 (14.07, 15.11) | 0.904 (0.129, 1.68) | 5.25b | 0.02 |

| Assertion | 13.30 (12.67, 13.93) | 10.41 (9.81, 11.02) | 2.89 (2.00, 3.77) | 41.25b | <0.001 |

| Academic Competence | 97.97 (96.35, 99.59) | 95.69 (94.21, 97.18) | 1.47 (0.05, 2.89) | 4.03b | 0.05 |

| Health Grade | 2.80 (2.63, 2.97) | 2.46 (2.27, 2.65) | 0.335 (0.08, 0.59) | 6.73b | 0.01 |

| Substance Use in Past 30 Days | |||||

| Alcohol, ≥1 drink(s) | 0.13 (0.09, 0.18) | 0.20 (0.16, 0.25) | 0.63 (0.51, 0.73) | 4.28c | 0.04 |

| Marijuana | 0.02 (0.04, 0.10) | 0.02 (0.06, 0.12) | 0.57 (0.41, 0.72) | 0.72c | 0.40 |

| Proportion Overweight | |||||

| Pre-intervention | 0.44 (0.39, 0.49) | 0.41 (0.36, 0.46) | |||

| Post Intervention | 0.42 (0.37, 0.47) | 0.41 (0.36, 0.45) | |||

| 6-Month Follow-up | 0.41 (0.36, 0.47) | 0.43 (0.38, 0.48) | |||

| Pre-intervention to 6-Month Follow-up | 0.45 (0.42, .50) | 4.69c | 0.03 | ||

| Beck Youth Inventories | |||||

| Anxiety at 6 months | 47.40 (46.50, 48.31) | 46.95 (46.11, 47.79) | 0.46 (−0.79, −1.70) | 0.52b | 0.47 |

| Depression at 6 months | 47.03 (46.21, 47.85) | 46.55 (45.80, 47.29) | 0.49 (−0.63, −1.60) | 0.73b | 0.39 |

Outcomes reported are at post-intervention except as indicated

F-test

Chi-Square

There were significant differences between groups for three subscales of the Social Skills Rating System. COPE teens had higher average scores on all three subscales: (1) Cooperation (COPE adjusted M=15.50 [95% CI=14.93, 16.06]; Healthy Teens adjusted M=14.59 [95% CI=14.07, 15.11]); (2) Assertion (COPE adjusted M=13.30 [95% CI=12.67, 13.93]; Healthy Teens adjusted M=10.41 [95% CI=9.81, 11.02]); and (3) Academic Competence (COPE adjusted M=97.97 [95% CI=96.35, 99.59]; Healthy Teens adjusted M=95.69 [95% CI=94.21, 97.18]). In addition, COPE teens on average earned a higher grade in the health course than did those in Healthy Teens (COPE adjusted M=2.80 [95% CI=2.63, 2.97]; Healthy Teens adjusted M=2.46 [95% CI=2.27, 2.65]).

Post-intervention alcohol use was significantly different between the groups (Chi-square 4.28, p=0.04). Alcohol use was 11.17% in the COPE group and 21.46% in the Healthy Teens group. No self-reported differences existed on either the Beck Youth Inventory for Anxiety (F1,682=0.10, p=0.75) or for Depression (F1,687=1.58, p=0.21), although each group did decrease their scores from pre- to post-intervention on at least one measure. For anxiety, COPE pre-intervention F=49.00 (10.51); post-intervention F=47.64 (8.97); the Healthy Teens pre-intervention F=47.94 (9.49); post-intervention F=46.91 (8.29). For depression, COPE pre-intervention F=46.55 (10.20); post-intervention F=46.57 (8.07); Healthy Teens pre-intervention F=46.55 (9.02); post-intervention F=45.88 (8.07).

Among COPE teens, 78% of the COPE teens reported that the program was helpful on the post-intervention evaluation questionnaire with hundreds of comments regarding specifically how COPE helped them. Students reported that the most-helpful program elements in COPE were the content on stress and coping, nutrition, and exercise. Among parents, 92% indicated that the program was helpful for their teens, and 94% of parents reported that they would recommend the program to family or friends. A total of 82% of parents agreed that information shared with them through the COPE newsletters was helpful.

6-Month Post-Intervention Outcomes

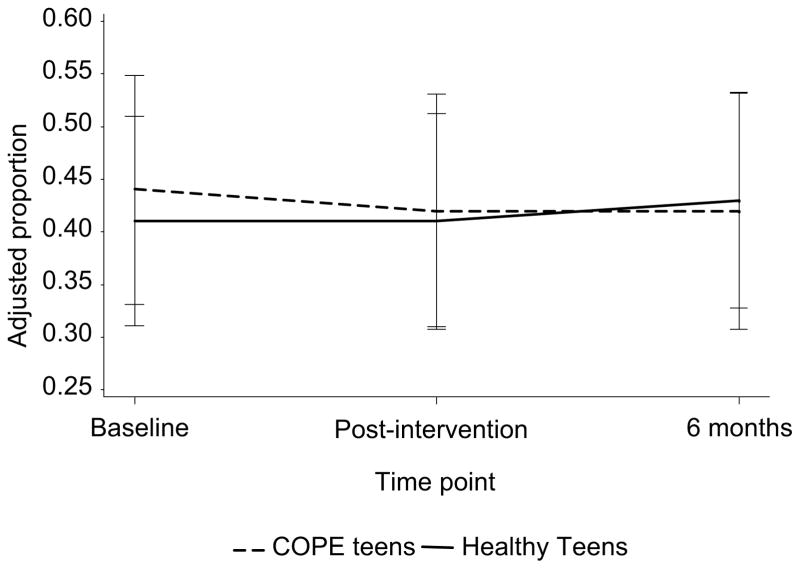

There was a significant difference between groups for BMI at the 6-month post-intervention follow-up assessment. COPE teens had a lower mean BMI than those in Healthy Teens (COPE=24.72, Healthy Teens=25.05, adjusted M= −0.34 [95% CI= −0.56 to −0.11]). Further, there was a significant change in the proportion of overweight between the groups from pre-intervention to 6-month follow-up (Chi-square=4.69, p=0.03). COPE teens decreased from 0.4411 to 0.4156; those in Healthy Teens increased from 0.4101 to 0.4311, adjusting for the covariates (Figure 2). For the COPE teens in the healthy weight category at baseline, 143 (97.3%) remained in the healthy weight category at 6 months; and four (2.7%) moved to the overweight category. For those in Healthy Teens, 187 (91.2%) remained in the healthy weight category at 6 months; 15 (7.3%) progressed to the overweight category; and three (1.5%) moved to the obese category.

Figure 2.

Percentage of overweight for the COPE and Healthy Teens groups across time

COPE (COPE Healthy Lifestyles TEEN Program), Creating Opportunities for Personal Empowerment Healthy Lifestyles Thinking, Emotions, Exercise, Nutrition Program

There were no significant differences between the groups at 6 months post-intervention on self-reported outcomes of anxiety or depression. For marijuana, 8.7% of those in COPE and 8.5% of those in Healthy Teens reported use in the past 30 days (Chi-square=0.01, p=0.93). At 6 months post-intervention, there was no difference in alcohol use between the two groups (COPE, 11.9%; Healthy Teens, 17.1%; Chi-square=3.47, p=0.06).

Discussion

Findings from this study indicate that COPE had a positive impact on physical activity, BMI, psychosocial outcomes, and grade performance in high school adolescents. To our knowledge, this is the first study to show improvements over time in multiple outcomes with a manualized teacher-delivered cognitive–behavioral skills-building intervention integrated into a high school health education curriculum. Whereas other studies22 have found short-term positive effects on health knowledge and BMI with multicomponent interventions that typically include nutrition education, physical activity and behavior modification, the current study indicates that multiple immediate and 6-month outcomes can be positively affected by teaching adolescents cognitive–behavioral skills, which include cognitive reappraisal, emotional and behavioral regulation, stress and coping, and learning how to set goals and problem-solve barriers to living a healthy lifestyle.

Recent findings from the national 2011 Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) indicated that the percentage of high school students who are obese increased during 2009–2011.17 Because overweight/obesity predisposes teens to adverse health outcomes compared to their non-overweight counterparts, including type 2 diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, sleep apnea, asthma and a shortened life span, there is an urgent need to develop and test interventions that can prevent and reduce this problem.28–30 In addition, overweight and obese teens have a higher prevalence of school and mental health problems, including academic problems, decreased social skills, increased depressive and anxiety disorders, and a greater number of reported suicide attempts.11,16,31–35

At 6 months, COPE teens had a significantly lower BMI. In addition, fewer teens who were in the healthy weight category at baseline in COPE versus Healthy Teens progressed to the overweight category at 6 months, and none became obese. These findings indicate that a cognitive–behavioral skills-building intervention combined with nutrition education and a brief period of physical activity may be an effective way to prevent overweight and obesity in teens.

It is alarming that the latest YRBS also found that 38% of youth reported drinking alcohol and 7.8% reported attempting suicide, both increases from the prior survey.17,36 As a result, the YRBS concluded that more effective school-based programs are needed to improve teen health outcomes. Because prior work has shown that lower self-esteem and higher levels of anxiety and depression are related to less healthy lifestyle beliefs and behavior choices,37,38 the building of cognitive–behavioral skills in adolescents may be a key strategy for improving not only their healthy lifestyle behaviors and physical health, but also their social skills and mental health outcomes.

In the national agenda for improving the state of obesity, it is unfortunate that mental/psychosocial health has been largely missing as a key construct to target in healthy lifestyle programs. Further, most obesity prevention and treatment studies have focused on school-age children in school settings.39–45 Thus, there is little evidence to guide high schools in health curricula that can positively influence not only adolescent healthy lifestyle behaviors, but also their psychosocial health and academic performance.

Unlike prior studies that have shown reductions in depression and anxiety when COPE was implemented by the current research team members,37,46 no significant differences were found between the COPE and Healthy Teens groups on these outcomes in this trial. However, there were numerous comments written by COPE students on their program evaluation indicating that COPE helped them to deal effectively with stress and anger as well as feel better about themselves. Less-than-adequate intervention fidelity by some of the teachers in this study may have influenced the lack of differential findings on these outcomes.

Limitations

Random assignment of schools to intervention conditions was conducted. However, a limitation of this study was that the two groups of students differed on some variables at baseline (e.g., weight, TV viewing time). As a result, these variables were used as covariates in the analyses. Another limitation of the trial was teacher intervention fidelity. The study team observed incidents of decreased fidelity to the intervention that occurred at least once, in approximately half of the classrooms. Immediate corrective measures by the team were instituted with the teachers when deviations from fidelity occurred.

The decision was made to have teachers deliver COPE because it is more feasible, cost-effective, and sustainable for high school educators who teach health to implement the program, avoiding the need for hiring additional personnel or relying on study team members to continue to deliver the intervention in the future. In the midst of school budget reductions across the country, sustainability of the COPE intervention, long after funding for the study has ended, would be enhanced by training teachers to deliver COPE. Studies have indicated that teachers may be better at sustaining longer-term positive outcomes because interventions may be reinforced in classrooms.47 However, studies also note that the effectiveness of interventions is linked to implementation quality and fidelity.48 Therefore, it is imperative for future studies to monitor teacher implementation and provide added supports to increase intervention fidelity.

Although there is a small body of evidence to support positive academic outcomes with mental health/social skills–building interventions and physical activity programs, the majority of these studies were conducted with school-aged children.19,49 The measurement of academic outcomes in future studies, including standardized test scores, when conducting school-based health promotion programs also is essential since public education has been pressured to improve academic performance of students, and added content must be justified as not only efficacious, but also cost-effective.

Conclusion

Findings from the current trial provide evidence that a teacher-delivered cognitive–behavioral skills-building intervention can positively affect a variety of important outcomes for high school adolescents at risk for a multitude of problems. Routine integration of COPE into health education curricula by teachers in real-world high school settings has the potential to improve health, psychosocial, and academic outcomes in high-risk populations of teens.

Acknowledgments

Special thanks go to Kim Weberg, Kristine Hartmann, Alan Moreno, Krista Oswalt, Megan Paradise, and Jonathon Rose for all of their efforts on and dedication to this study.

This study was funded by the NIH/ National Institute of Nursing Research 1R01NR012171.

Footnotes

No financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.CDC. Youth risk behavior surveillance-U.S., 2005. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2006;55(SS-5):1–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Evans D, Seligman M. Introduction. In: Evans D, Foa E, Gur R, et al., editors. Treating and preventing adolescent mental health disorders: What we know and what we don’t know. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press; 2005. pp. xxv–xl. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ogden C, Carroll M, Curtin L, et al. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in the U.S. 1999–2004. JAMA. 2006;295(13):1549–55. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.13.1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Flegal KM, Ogden CL, Carroll MD. Prevalence and trends in overweight in Mexican-American adults and children. Nutr Rev. 2004;62(7 Pt 2):s144–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2004.tb00085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roberts RE, Roberts CR, Chen YR. Ethnocultural differences in prevalence of adolescent depression. Am J Community Psych. 1997;25(1):95–110. doi: 10.1023/a:1024649925737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saluja G, Iachan R, Scheidt PC, et al. Prevalence of and risk factors for depressive symptoms among young adolescents. Archives Pediatrics Adolescent Med. 2004;158(8):760–5. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.158.8.760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ogden C, Lamb M, Carroll M, Flegal K. Obesity and socioeconomic status in children and adolescents: U.S., 2005–2008. NCHS Data Brief. 2010 Dec;2010(51):1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Daniels DY. Examining attendance, academic performance, and behavior in obese adolescents. J School Nursing. 2008;24:379–87. doi: 10.1177/1059840508324246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vila G, Zipper E, Dabbas M, et al. Mental disorders in obese children and adolescents. Psychosomatic Med. 2004;66(3):387–94. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000126201.12813.eb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Melnyk BM, Moldenhauer Z, editors. The KySS Guide to Child and Adolescent Mental Health Screening, Early Intervention and Health Promotion. Cherry Hill NJ: National Association of Pediatric Nurse Practitioners; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stein REK, Zitner LE, Jensen PS. Interventions for adolescent depression in primary care. Pediatrics. 2006;118(2):669–82. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anderson P, Butcher K. Childhood obesity: trends and potential causes. The Future of Children. 2006;16(1):19–45. doi: 10.1353/foc.2006.0001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aaron D, Jekal Y, LaPorte R. Epidemiology of physical activity from adolescence to young adulthood. World Rev Nutr Diet. 2005;94:36–41. doi: 10.1159/000088204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rennie K, Johnson L, Jebb S. Behavioural determinants of obesity. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2005;19(3):343–58. doi: 10.1016/j.beem.2005.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goran M, Gower B, Nagy T, Johnson R. Developmental changes in energy expenditure and physical activity in children: Evidence for a decline in physical activity in girls before puberty. Pediatrics. 1998;101(5):887–91. doi: 10.1542/peds.101.5.887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goodman E, Whitaker R. A prospective study of the role of depression in the development and persistence of adolescent obesity. Pediatrics. 2002;109(3):497–504. doi: 10.1542/peds.110.3.497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.CDC. Youth risk behavior surveillance—U.S. 2011. MMRW Surveill Summ. 2012;61(SS-4):1–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Melnyk B, Small L, Moore N. The worldwide epidemic of child and adolescent overweight and obesity: calling all clinicians and researchers to intensify efforts in prevention and treatment. Worldviews Evid Based Nurs. 2008;5(3):109–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-6787.2008.00134.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murray N, Low B, Hollis C, Cross A, Davis S. Coordinated school health programs and academic achievement: A systematic review of the literature. J Sch Health. 2007;77(9):589–600. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2007.00238.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jain A. Treating obesity in individuals and populations. BMJ. 2005;331(7529):1387–90. doi: 10.1136/bmj.331.7529.1387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jerum A, Melnyk B. Effectiveness of interventions to prevent obesity and obesity-related complications in children and adolescents. Pediatr Nurs. 2001;27(6):606–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kelly S, Melnyk B. Systematic review of multicomponent interventions with overweight middle adolescents: implications for clinical practice and future research. Worldviews on Evidence-based Nursing. 2008;5(3):113–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-6787.2008.00131.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kropski J, Keckley P, Jensen G. School-based obesity prevention programs: an evidence-based review. Obesity. 2008;16:1009–18. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Melnyk BM. Healthy Lifestyles Behavior Scale. Hammondsport, NY: COPE for HOPE, Inc; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beck JS, Beck AT, Beck JJ. Youth Inventories for Children and Adolescents: Manual. 2. San Antonio, Texas: Harcourt Assessment; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gresham FM, Elliot SN. Social skills rating system manual. Minneapolis, MN: NCS Pearson, Inc; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Unger BJ, Gallaher P, Shakib S, et al. The AHIMSA acculturation scale: A new measure of acculturation for adolescents in a multicultural society. J Early Adolescence. 2002;22:225–51. [Google Scholar]

- 28.American Academy of Pediatrics. Clinical practice guideline: diagnosis and management of childhood obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Pediatrics. 2002;109(4):704–12. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.4.704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Freedman D, Dietz W, Srinivasan S, Berenson G. The relation of overweight to cardiovascular risk factors among children and adolescents: the Bogalusa Heart Study. Pediatrics. 1999;103(6 Pt 1):1175–82. doi: 10.1542/peds.103.6.1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stabouli S, Kotsis V, Papamichael C, Constantopoulos A, Zakopoulos N. Adolescent obesity is associated with high ambulatory blood pressure and increased carotid intimal-medial thickness. J Ped. 2005;147(5):651–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2005.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Falkner NH, Neumark-Sztainer D, Story M, et al. Social, educational, and psychological correlates of weight status in adolescents. Obesity Res. 2001;9(1):32–42. doi: 10.1038/oby.2001.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Friedlander SL, Larkin EK, Rosen CL, Palermo TM, Redline S. Decreased quality of life associated with obesity in school-aged children. Archives Pediatrics Adolescent Med. 2003;157(12):1206–11. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.157.12.1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sjoberg RL, Nilsson KW, Leppert J. Obesity, shame, and depression in school-aged children: a population-based study. Pediatrics. 2005;116(3):e389–92. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Strauss RS. Childhood obesity and self-esteem. Pediatrics. 2000;105(1):e15. doi: 10.1542/peds.105.1.e15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bell S, Morgan S. Children’s attitudes and behavioral intentions toward a peer presented as obese. Does a medical explanation for the obesity make a difference? J Ped Psychology. 2002;25:137–45. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/25.3.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hoelscher D, Day R, Lee E, et al. Measuring the prevalence of overweight in Texas schoolchildren. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(6):1002–8. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.6.1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Melnyk B, Jacobson D, Kelly S, et al. Improving the mental health, healthy lifestyle choices and physical health of hispanic adolescents: a randomized controlled pilot study. J School Health. 2009;79(12):575–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2009.00451.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Melnyk BM, Small L, Morrison-Beedy D, et al. Mental health correlates of healthy lifestyle attitudes, beliefs, choices, and behaviors in overweight adolescents. J Pediatric Health Care. 2006;20(6):401–6. doi: 10.1016/j.pedhc.2006.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Harrell J, Gansky S, McMurray R, et al. School-based interventions improve heart health in children with multiple cardiovascular disease risk factors. Pediatrics. 1998;102(2 Pt 1):371–80. doi: 10.1542/peds.102.2.371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Harrell J, McMurray R, Baggett C, et al. Energy costs of physical activities in children and adolescents. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2005;37(2):329–36. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000153115.33762.3f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Harrell J, McMurray R, Bangdiwala S, et al. Effects of a school-based intervention to reduce cardiovascular disease risk factors in elementary-school children: the Cardiovascular Health in Children (CHIC) study. Pediatrics. 1996;128(6):797–805. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(96)70332-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Harrell J, Pearce P, Markland E, et al. Assessing physical activity in adolescents: common activities of children in 6th–8th grades. J Am Acad Nurse Pract. 2003;15(4):170–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7599.2003.tb00259.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Huhman M, Potter L, Wong F, et al. Effects of a mass media campaign to increase physical activity among children: year-1 results of the VERB campaign. Pediatrics. 2005;116(2):e277–284. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-0043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lyznicki J, Young D, Riggs J, Davis R. Council on Scientific Affairs AMA. Obesity: assessment and management in primary care. Am Fam Physician. 2001;63(11):2185–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nader P, Sellers D, Johnson C, et al. The effect of adult participation in a school-based family intervention to improve Children’s diet and physical activity: the Child and Adolescent Trial for Cardiovascular Health. Prev Med. 1996;25(4):455–64. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1996.0077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lusk P, Melnyk BM. The Brief Cognitive–Behavioral COPE Intervention for Depressed Adolescents: Outcomes and Feasibility of Delivery in 30-Minute Outpatient Visits. J American Psychiatric Nurses Association. 2011;17(3):226–36. doi: 10.1177/1078390311404067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Adi YAK, Janmohamed K, Stewart-Brown S. Systematic review of the effectiveness of interventions to promote mental wellbeing in children in primary education: Report 1: Universal Approaches Non-violence related outcomes. Coventry: University of Warwick; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Derzon J, Sale E, Springer J, Brounstein P. Estimating intervention effectiveness: Synthetic projection of field evaluation results. J Prim Prev. 2005;26(4):321–343. doi: 10.1007/s10935-005-5391-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Evans D, Clark N, Feldman C, et al. A school health education program for children with asthma aged 8–11 years. Health Educ Q. 1987;14(3):267–279. doi: 10.1177/109019818701400302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]