Abstract

Most Americans know little about options for long-term services and supports and underestimate their likely future needs for such assistance. Using data from the 2012 National Health Interview Survey, we examined expectations about future use of long-term services and supports among adults ages 40–65 and how these expectations varied by current living arrangement. We found differences by living arrangement in expectations about both future need for long-term services and supports and who would provide such care if needed. Respondents living with minor children were the least likely to expect to need long-term services and supports and to require paid care if the need arose. In contrast, respondents living alone were the most likely to expect that it was “very likely” that they would need long-term services and supports and to rely on paid care. Overall, we found a disconnect between expectations of use and likely future reality: 60 percent of respondents believed that they were unlikely to need long-term services and supports in the future, whereas the evidence suggests that nearly 70 percent of older adults will need them at some point. These findings both underscore the need for programs that encourage people to plan for long-term services and supports and indicate that information about living arrangements can be useful in developing and targeting such programs.

In 2005 nearly eleven million community-dwelling people in the United States needed long-term services and supports to help address limitations in activities,[1] and the need for long-term services and supports will grow in the coming decades as the population ages.[2] An estimated 70 percent of Americans age 65 and older are projected to experience some level of need for long-term services and supports.[3] Those who survive to age sixty-five have a 46 percent chance of spending time in a nursing home.[4] These percentages may be underestimates, as rates of disability among today’s middle-aged adults (people ages 50–64) and “younger” older adults (those ages 60–69) are higher than those among their older counterparts at comparable ages.[5,6]

Most Americans know little about the options for getting long-term services and supports and underestimate their likely future needs for such assistance.[7] The majority of Americans do not know how much long-term services and supports cost or who pays for them.[8,9] Nearly 60 percent of adults ages forty and older underestimate the cost of nursing home care, and more than half do not expect to use Medicaid to pay for long-term services and supports—despite the fact that Medicaid pays for nearly two-thirds of all long-term services and supports in the United States.[10] Adults also overestimate the role that Medicare will play in paying for long-term services and supports, and just over one-third have set aside any money to pay for such assistance in the future.[11]

People’s assessments of personal risk are a vital determinant of planning for long-term services and supports and depend on age, health status, retirement goals, income, assets, and knowledge about long-term services and supports.[12,13] A 2007 study that examined financial literacy and retirement planning among baby boomers who were then ages 51–56 found that most respondents had low financial literacy, but those who were more financially knowledgeable were more likely to have thought about their needs for long-term services and supports.[14]

People with previous experiences of caregiving and those who perceive themselves to be at risk of needing long-term services and supports and who perceive long-term care insurance for such assistance to be affordable are more receptive to the need for financial planning, including considering that insurance.[15] In contrast, people who expect to rely on family members for care are less likely to purchase the insurance.[16]

The existing literature has contributed to the understanding of attitudes regarding planning for long-term services and supports but remains limited in key areas. The majority of studies have used descriptive analyses without adequate controls for demographic and other factors. Most studies have focused on particular aspects of general knowledge about long-term services and supports or long-term care insurance and have not comprehensively examined the factors that shape attitudes toward perceived future need for long-term services and supports. In particular, the potential role of current living arrangements is absent from much of the literature.

Since the middle of the twentieth century, and especially since the 1980s, there have been at least two major changes in those arrangements: increases in the proportions of multigenerational households and of single-parent households, and a decline in the share of “traditional” households containing two parents and their children.[17-19] At the same time, policies related to the 1999 Supreme Court Olmstead v. L.C. decision, Medicaid funding for home and community-based services, and Medicaid’s Money Follows the Person program have shifted the locus of care from institutional to community settings.

It is now increasingly possible for people with disabilities to age in the community instead of in institutional settings, provided that they have appropriate and supportive living arrangements in which to do so. Therefore, living arrangements are a potentially important determinant of where a person receives long-term services and supports and what form they might take.

The majority of all community-based long-term services and supports is provided by unpaid caregivers.[10] By 2040, approximately three-quarters of all older adults with severe disabilities will receive assistance from by unpaid caregivers,[2] despite the growth of paid home and community-based services. Because the majority of care is provided by family and friends in home settings, current living arrangements may offer important insights into people’s expectations about future use of long-term services and supports.

Some people may expect that those they live with will provide any needed care, and such expectations might prevent people from making plans for paid care to remain in the community. Indeed, a 2014 study found that nearly one-third of adults ages forty and older have made no plans about how to pay for long-term services and supports.[20] Beyond savings and private insurance, the same study found that other strategies for financing long-term services and supports include having one’s family pay for it, selling one’s home, and taking out a mortgage. Nearly 40 percent of those surveyed believed that Medicare would pay for long-term services and supports, while only 11 percent believed that Medicaid would.[20]

This disconnect between expectations and projected needs is a significant barrier to helping Americans become better prepared for their future and has contributed to the low uptake of private long-term care insurance.[7] A person’s decision not to invest in such insurance may also be driven by its high cost.[7,15]

The challenge of increasing uptake in long-term care insurance was supposed to be reduced by the Community Living Assistance Services and Supports (CLASS) Act legislation contained in the Affordable Care Act (ACA). The CLASS Act was designed to create an opt-out program through which employees could pay monthly premiums out of their paychecks to receive future long-term care benefits. This program likely would have increased uptake in long-term care insurance, but it would not have removed premium cost barriers. In any case, the CLASS Act was repealed.

In January 2013, in the wake of the act’s demise, the Commission on Long-Term Care was established. It was charged with developing a plan for the establishment, implementation, and financing of a comprehensive system of long-term services and supports. The commission ultimately did not produce such a plan, leaving planning for long-term services and supports to remain largely a personal responsibility. However, the commission concluded that the long-term services and supports system “is not sufficient for current or future needs.”[10]

Nearly two-thirds of the cost of long-term services and supports is financed by the federal and state governments through the Medicaid program.[10] This is financially unsustainable, given the projected dramatic increase in the need for long-term services and supports in the coming decades as a result of increases in older adult populations with chronic illness and dementia.[21] Thus, in the wake of growing demand and strained government resources, there is a need for programs that encourage people to make plans—financial and otherwise—for future use of long-term services and supports.

A better understanding of what drives future expectations about the use of long-term services and supports would be useful in designing policies and programs to encourage planning for such assistance. Moreover, knowing what those expectations are would make it possible to identify any gaps between them and likely future reality. This study used nationally representative survey data to examine whether current living arrangements were associated with expectations about future need for long-term services and supports and whether expectations about who will provide such assistance vary by current living arrangement.

Study Data And Methods

Data

Our data came from the 2012 wave of the Integrated Health Interview Series, a harmonized version of the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS).[22] The NHIS is a nationally representative survey of US civilians in noninstitutionalized households. Within households, one sample adult and, if applicable, one sample child are randomly chosen to answer questions in addition to those asked of everyone else in the household.

Questions on expectations about long-term services and supports were added to the survey in 2011 and are asked of all sample adults ages 40–65. We used data about all sample adults in that age group who answered questions on expectations about long-term services and supports (N = 11,796).

To assess expectations about needing long-term services and supports in the future, respondents were asked, “How likely is it that you may someday need help with daily activities like bathing, dressing, eating, or using the toilet due to a long-term condition?” The four response options ranged from “very likely” to “very unlikely.”

Regardless of their answer, respondents were also asked, “If you needed such help, who would provide this help?” The response options were “family,” “hiring someone,” “home health agency,” “nursing home or assisted living facility,” and “other.” Respondents could select multiple options. We also created a binary variable that indicated whether or not respondents expected to use more than one source of care.

The key independent variable was current living arrangement, categorized as with a spouse or partner only, alone, with a spouse or partner and a minor child or children only, with a minor child or children only, or with extended family members or unrelated others. The last category included adults living with roommates; adult-only families other than couples, such as adult siblings living together or parents living with adult children; at least one parent and a minor child or children living with other related adults; and related or unrelated adults living with one or more minor children but not with any of the children’s parents (as in the case of people raising their grandchildren).

For covariates we used sex, age, race or ethnicity (white, black or African American, Hispanic, and Asian or other), family income, educational attainment (less than high school degree, high school degree, some college, and four-year college degree or more), and employment status (employed versus unemployed or not in the labor force).

We also adjusted for the following health characteristics: self-rated physical health (fair or poor health versus good, very good, or excellent health), serious psychological distress (assessed by asking how often in the past thirty days the respondent had felt sad, restless, worthless, hopeless, nervous, and that everything was an effort; a score of thirteen or higher out of a possible twenty-four indicated serious psychological distress),[23] and the presence of an activity limitation (defined as needing help with personal care needs and limitations in the amount or kind of work or other activities the respondent was able to do).

Finally, we adjusted for whether the respondent had a close relative (a parent, spouse, sibling, or adult child) who, at the time of the survey, had needed help for at least a year with activities of daily living because of a chronic illness or disability.

Analysis

Bivarate analyses used chi-square tests of significance to assess differences in independent variables by type of living arrangement. We used ordered logistic regression models to estimate the odds of expecting to need long-term services and supports in the future, first adjusting only for living arrangement and then adjusting for the full list of covariates. Ordered logistic regression was appropriate for the categorical response options and allowed us to make use of variations across all four categories.[24] We present results from these models as odds ratios, which can be interpreted as the change in odds from one level (for example, “very unlikely”) to the next (“somewhat unlikely”).

Finally, we used logistic regression models to estimate the odds of using each source of long-term service and support by living arrangement, with all covariates adjusted for. All analyses used survey weights to account for the complex sampling design and to generate nationally representative estimates.

Limitations

This study should be considered in light of its limitations. The data were cross-sectional, so we could not control for the direction of causality between living arrangements and perceived future need for long-term services and supports. However, the majority of the respondents in the sample reported being in good health and having no activity limitations, so they were unlikely to be receiving long-term services and supports at the time of the survey.

Furthermore, we believe that for middle-aged adults, the majority of whom do not expect to need long-term services and supports, endogeneity is unlikely—that is, expectations about future care needs are unlikely to determine current living arrangements. To better ensure that living arrangements were not endogenous to our outcomes of interest, we conducted sensitivity analyses and found that our results were largely robust to various specifications. However, we did find differences by age group, which are discussed in the Study Results section and in online Appendix Exhibits 5 and 6.[25]

In addition, limited information is available about the exact composition of the extended households in our sample. The NHIS provides information on respondents’ relationship to the household head (for example, spouse, child, parent, or sibling). However, it is not possible to discern the exact relationships between other adults within a household. Given the increasing variation in living arrangements, future research should address this gap by collecting more detailed information on intrahousehold relationships and investigating differences between types of extended households—such as differences in expectations about long-term services and supports between a parent living with an adult child and an adult living with an unrelated adult.

Study Results

Sample Characteristics

The most common living arrangements in our sample were living with a spouse only or living alone (29 percent each). Women made up 53 percent of the sample but 75 percent of all parents living alone with a minor child or children. Both men and women living with minor children (with or without a spouse, but with no one else) were younger than the average.

Living arrangements differed by race or ethnicity. Eighty-three percent of respondents living with a spouse only, but just 72 percent of the full sample, were whites. Similarly, blacks made up a disproportionate percentage of households with a parent living alone with minor children, and Hispanics a disproportionate share of people living in extended family households.

Family income, educational attainment, and employment rates were highest among those living with a spouse and minor children only. Respondents living alone were most likely to report being in fair or poor health, being in psychological distress, and having activity limitations.

Eleven percent of the sample had a close relative who had needed long-term services and supports for at least a year at the time of the survey. However, this percentage also differed by living arrangement, with respondents who lived with minor children, with or without a spouse, being the least likely to have such a close relative. For full sample characteristics, see online Appendix Exhibit 1.[25]

Perceived Need For Long-Term Services And Supports

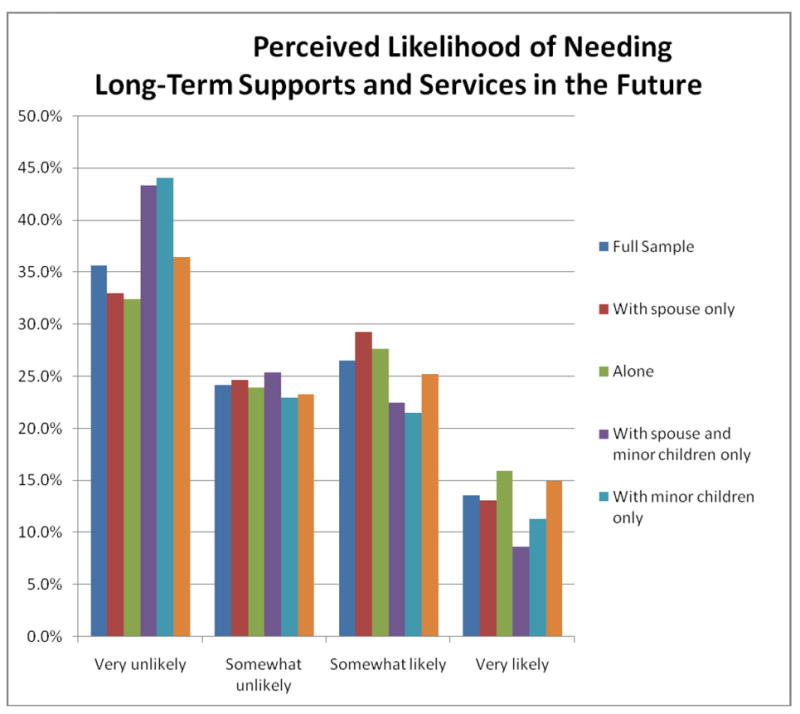

Sixty percent of the respondents believed that they were very or somewhat unlikely to need long-term services and supports in the future (Exhibit 1). Only 14 percent responded that they were very likely to need care.

EXHIBIT 1.

Perceived Likelihood Of Needing Long-Term Services And Supports In The Future, By Living Arrangement

Source/Notes: SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data from the 2012 National Health Interview Survey,. NOTES Analyses were weighted to approximate nationally representative estimates. The sample consisted of 11,796 respondents; the population was 34,480,308.All differences in perceived likelihood between living arrangements were significant (p< 0.001). “With spouse only” means living with a spouse or partner only. “With spouse and minor children only” means living with a spouse or partner and with a minor child or children only. “With minor children only” means living with a minor child or children only.

The perceived likelihood varied by living arrangement. Respondents who lived with minor children only or with a spouse and minor children only were the most likely to report that they were very unlikely to need long-term services and supports. People living alone were the most likely to describe themselves as very likely to need such assistance.

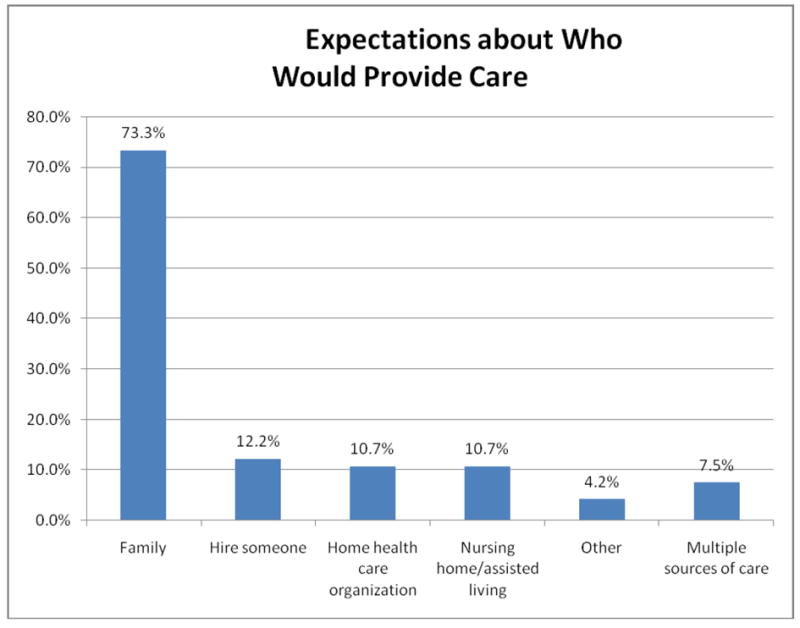

Expectations About Sources Of Care

When asked about expected sources of long-term services and supports, 73.3 percent of the respondents believed that their family would provide such assistance (Exhibit 2). The response options were not mutually exclusive, and 7.5 percent of respondents believed that they would use multiple sources of care. Of those respondents, more than 30 percent believed that they would use three or more sources of care (data not shown).

EXHIBIT 2.

Expectations About Who Would Provide Long-Term Services And Supports

Source/Notes: SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data from the 2012 National Health Interview Survey. NOTES Analyses were weighted to approximate nationally representative estimates. The sample consisted of 11,796 respondents; the population was 34,480,308.

Living Arrangements And Perceived Need For Long-Term Services And Supports

Respondents living alone or in extended households did not differ significantly from those living with a spouse only in their expectations about needing long-term services and supports in the future (Exhibit 3). However, those living with minor children only and those living with minor children and a spouse only had lower odds of expecting to need long-term services and supports. Those differences persisted after we adjusted for individual characteristics, although the strength of the association diminished.

Exhibit 3.

Odds of Expecting to Need Long-Term Supports and Services, By Respondents’ Characteristics

| Odds ratio | ||

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Unadjusted model | Fully adjusted model | |

| Living arrangement | ||

| With spouse only | Ref | Ref |

| Alone | 1.07 | 0.96 |

| With spouse and minor children only | 0.64**** | 0.85** |

| With minor children only | 0.67**** | 0.84*** |

| With extended family members or unrelated others | 0.92 | 0.96 |

| Sex and age | ||

| Female | 1.10** | |

| Age | 1.01**** | |

| Race or ethnicity | ||

| White | Ref | |

| Black or African American | 0.89* | |

| Hispanic | 0.98 | |

| Asian or other | 0.75*** | |

| 1.00 | ||

| High school degree | Ref | |

| Less than high school degree | 1.07 | |

| Some college | 1.02 | |

| Four-year college degree or more | 1.23**** | |

| Employment status | ||

| Employed | 0.96 | |

| 1.96**** | ||

| 1.65**** | ||

| 2.08**** | ||

| 1.98**** | ||

Source/Notes: SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data from the 2012 National Health Interview Survey. NOTES Analyses were weighted to approximate nationally representative estimates. The sample consisted of 11,796 respondents; the population was 34,480,308. The F-statistics are 22.97 for the unadjusted model and 48.71 for the fully adjusted model (both p < 0.001). “Spouse” means spouse or partner. “Children” means child or children.“Serious psychological distress,” “activity limitation,” and “close relative” are defined in the text. LTSS is long-term services and supports.

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

p < 0.001

Certain individual characteristics (notably, having an activity limitation or a close relative who had needed long-term services and supports for at least a year at the time of the survey) were associated with higher odds of expecting to need long-term services and supports. Being either black or Asian was associated with lower odds. (For complete results, including standard errors, see online Appendix Exhibit 2).[25]

There were significant differences by living arrangement in expected sources of care, should a need for long-term services and supports arise (Exhibit 4). After all covariates were adjusted for, living alone was associated with lower odds of expecting to rely on family and higher odds of expecting to use each of the other options, compared with living with a spouse only. Both living with a spouse and minor children only and living in an extended family setting were associated with higher odds of expecting to rely on family. Living with minor children only was associated with lower odds of expecting to rely on family and higher odds of expecting to use a nursing home or assisted living facility. There were no significant differences by living arrangement in expecting to use multiple sources of care. (For complete results, including standard errors, see online Appendix Exhibit 3.)[25]

Exhibit 4.

Expectations About Using Each Source Of Long-Term Service And Support

| Odds ratio

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Living arrangement | Family | Hiring someone | Home health agency | Nursing home or assisted living facility | Other | Multiple sources |

|

|

||||||

| With spouse only | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref | Ref |

| Alone | 0.35**** | 1.88**** | 1.72**** | 1.78**** | 2.15**** | 1.01 |

| With spouse and minor children only | 1.51**** | 0.56**** | 0.91 | 0.92 | 0.54*** | 0.81 |

| With minor children only | 0.62*** | 0.71 | 1.37 | 1.84** | 1.17 | 0.72 |

| With extended family members or unrelated others | 1.25*** | 0.69** | 0.97 | 1.13 | 1.01 | 1.07 |

Source/Notes: SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data from the 2012 National Health Interview Survey.NOTES Analyses were weighted to approximate nationally representative estimates. The sample consisted of 11,796 respondents; the population was 34,480,308.All models were adjusted for sex, age, race or ethnicity, family income, educational attainment, employment, health status, psychological distress, presence of an activity limitation, having a close relative who has needed long-term services and supports for at least a year at the time of the survey, and personal expectations of use of long-term services and supports. “Spouse” means spouse or partner. “Children” means child or children.

p < 0.05

p < 0.01,

p < 0.001

Living Arrangements And Expected Sources Of Care

To determine whether living arrangements were differentially associated with expected sources of care according to how much people expected to need long-term services and supports, we modeled expected sources of care for people who believed that they were very likely to need long-term services and supports. We found less diversity by living arrangements than in the full sample. This indicates that current living arrangements had less influence on expected sources of care for people who expected to need long-term services and supports. (For full results, see online Appendix Exhibit 4).[25]

Additionally, we conducted sensitivity analyses by age (people ages 40–49 versus those ages 50–65) and found differences by age cohort in the relationship between living arrangements and expectations about long-term services and supports. In particular, compared to the younger group, there were fewer differences in the older group in expectations about long-term services and supports by living arrangement. (For full results, see online Appendix Exhibits 5 and 6.)[25]

Discussion

These results provide insights into the expectations of middle-aged adults about their future use of long-term services and supports. The majority of respondents did not believe that they would need such assistance in the future, despite estimates that 70 percent of older Americans will need some form of long-term services and supports.[3]

As explained above, regardless of whether or not they expected to need long-term services and supports, respondents were asked who they would rely on for care, should the need arise. Respondents were nearly seven times as likely to expect family to help as they were to expect to rely on a home health agency or on a nursing home or assisted living facility (Exhibit 2). This aligns with the current reality that the majority of long-term services and supports are provided by unpaid caregivers who are family members or friends. Given the aging of the population, this finding may indicate an even larger burden on such caregivers in the future.

Living Arrangements

In several respects, future care expectations varied by current living arrangement. In particular, respondents living with minor children only or with a spouse and minor children only had the lowest odds of expecting to need long-term services and supports in the future (Exhibit 3). People living with minor children only and people living alone were the least likely to expect to rely on family for long-term services and supports in the future, and the most likely to expect to rely either on home health agencies or on nursing homes or assisted living facilities (Exhibit 4). Parents living alone with minor children and those living alone were the most likely to be low income (see online Appendix Exhibit 1.[25]). This might indicate that if these people do need long-term services and supports, they will be more likely to rely on public programs such as Medicaid to help them afford that care.

Policy makers should be especially concerned about the 29 percent of the sample who lived alone, because they were in the worst health and had the highest prevalence of activity limitations of any group in the sample. Therefore, they were likely to need long-term services and supports sooner than some of the other groups, and they had considerably lower odds of expecting to rely on family for support. They were also the only group to have higher odds of expecting to use each source of paid care system.

Policy makers should consider using this information to make projections about future spending needs for long-term services and supports. Parents living alone with minor children might also be of particular concern, as their current caregiving responsibilities may make it difficult for them to plan for their own future needs for long-term services and supports.

Respondents living with spouses and minor children only had higher odds of expecting to rely on family for support and lower odds of expecting to hire someone. In the unadjusted model, they were also the least likely to expect to need long-term services and supports in the future. This may be explained by their younger age and better health, relative to the rest of the sample, as well as by their current familial support system.

However, policy makers should be concerned that people in this group may lack motivation to make advanced plans for long-term services and supports. If they expect family to provide help, they may not be likely to plan or save for long-term services and supports, despite the fact that their household composition is likely to change in coming decades.

Respondents living in extended households primarily expected to rely on family, should a need for care arise. These households are becoming increasingly common,[17-19] but they are not well understood. Future research should attempt to better understand differences in expectations about long-term services and supports by the type of extended family structure and by the type of caregiving that takes place within these households.

In the case of our sample (people ages 40–65), it is likely that most caregiving currently happening within these households is being provided by the respondent to children, aging parents, or both (in the case of the so-called sandwich generation). Given that such arrangements are increasingly common, it would be useful to understand how they affect people’s expectations about their future care use. Furthermore, research should examine longitudinally the association between expectations about and actual use of long-term services and supports for all living arrangements.

Demographic Characteristics And Health Status

In addition to variations by living arrangement in expectations about long-term services and supports, we found differences by demographic characteristics and health status. As noted above, having an activity limitation or a close relative who had needed long-term services and supports for at least a year at the time of the survey were associated with higher odds of expecting to need long-term services and supports, and being either black or Asian was associated with lower odds (Exhibit 4).

This information can be used to design and target educational outreach campaigns for planning for long-term services and supports. For example, if knowing someone who has needed long-term services and supports for at least a year increases one’s odds of expecting to need such assistance oneself, it may be useful to provide personal narratives to engage people in thinking more realistically about their own potential future need for long-term services and supports.

Recommendations

Overall, more education is needed to encourage people to make plans about long-term services and supports and to inform consumers of the risks that needing such assistance may pose for their future financial security. One strategy for addressing these issues includes translating awareness of long-term care insurance into ownership of it. Only about 8 percent of Americans owns a long-term care insurance policy,[26] despite the high projected needs for long-term care.

Changing attitudes and beliefs about, and degree of preparedness for, long-term services and supports can happen through a multifaceted approach, one that targets consumers via educational awareness; engages financial consultants and employers, through employer-sponsored long-term care insurance; and builds on recent and current national efforts to reform the long-term services and supports system, including the CLASS Act, the Commission on Long-Term Care, and efforts to reimburse family members when they assume caregiver roles.[26]

Conclusion

Current living arrangements of middle-aged adults offer insights into expectations about future use of long-term services and supports. This is especially important, as the majority of long-term services and supports is provided in home and community-based settings, so people may base their expectations about future care on their current experiences with care in the home. Further, if a need for care arises, people are likely to receive long-term services and supports in their home, so their living arrangement will likely impact their experience receiving care.

Across all living arrangements, middle-aged adults appear to have unrealistically low expectations about needing long-term services and supports in general, and paid long-term services and supports in particular. This signals a need to develop programs that encourage planning for long-term services and supports. Such programs can be tailored by living arrangement and family structure.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The preparation of this article was supported by the Integrated Health Interview Series project at the Minnesota Population Center (National Institutes of Health Grant Nos. R01HD046697 and R24HD041023), funded through grants from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute for Child Health and Human Development. Additional support was provided to Carrie Henning-Smith by the University of Minnesota Interdisciplinary Doctoral Fellowship and to TetyanaShippee by the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health (Grant No. UL1TR000114).

Biographies

Carrie E. Henning-Smith (henn0329@umn.edu) is a PhD candidate in the Division of Health Policy and Management, School of Public Health, University of Minnesota, in Minneapolis.

Tetyana P. Shippee is an assistant professor in the Division of Health Policy and Management, School of Public Health, University of Minnesota.

Contributor Information

Carrie Henning-Smith, University of Minnesota School of Public Health – Division of Health Policy and Management.

Tetyana Shippee, University of Minnesota School of Public Health – Division of Health Policy and Management.

NOTES

- 1.Kaye HS, Harrington C, LaPlante MP. Long-term care: who gets it, who provides it, who pays, and how much? Health Aff (Millwood) 2010;29(1):11–21. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Johnson RW, Toohey D, Wiener JM. Washington (DC): Urban Institute; 2007. May, [2014 Oct 17]. Meeting the long-term care needs of the baby boomers: how changing families will affect paid helpers and institutions. [Internet]. (Retirement Project Discussion Paper No. 07-04). Available from: http://www.urban.org/UploadedPDF/311451_Meeting_Care.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kemper P, Komisar HL, Alecxih L. Long-term care over an uncertain future: what can current retirees expect? Inquiry. 2005–06;42(4):335–50. doi: 10.5034/inquiryjrnl_42.4.335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spillman BC, Lubitz J. New estimates of lifetime nursing home use: have patterns of use changed? Med Care. 2002;40(10):965–75. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200210000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Seeman TE, Merkin SS, Crimmins EM, Karlamangla AS. Disability trends among older Americans: National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys, 1988–1994 and 1999–2004. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(1):100–7. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.157388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martin LG, Freedman VA, Schoeni RF, Andreski PM. Trends in disability and related chronic conditions among people ages fifty to sixty-four. Health Aff (Millwood) 2010;29(4):725–31. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2008.0746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.MetLife Mature Market Institute. MetLife long-term care IQ: removing myths, reinforcing realities. New York (NY): The Institute; 2009. Sep, [2014 Oct 17]. [Internet]. Available from: https://www.metlife.com/assets/cao/mmi/publications/consumer/long-term-care-essentials/mmi-long-term-care-iq-removing-myths-survey.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 8.GfK NOP Roper Public Affairs and Media. Washington (DC): AARP; 2006. Dec, [2014 Oct 17]. The costs of long-term care: public perceptions versus reality in 2006. [Internet]. Available from: http://assets.aarp.org/rgcenter/health/ltc_costs_2006.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Glover Park Group. New York (NY): National Commission for Quality Long-Term Care; 2007. [2014 Oct 17]. Voters speak out on long-term care. [Internet]. Available from: http://www.newschool.edu/ltcc/pdf/Final_Survey_Report_20071203.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 10.US Senate Commission on Long-Term Care. Washington (DC): Government Printing Office; 2013. Sep 30, [2014 Oct 17]. Report to the Congress. [Internet]. Available from: http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/GPO-LTCCOMMISSION/pdf/GPO-LTCCOMMISSION.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tompson T, Benz J, Agiesta J, Junius D, Nguyen K, Lowell K. Chicago (IL): Associated Press-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research; 2013. [2014 Oct 17]. Long-term care: perceptions, experiences, and attitudes among Americans 40 or older. [Internet]. Available from: http://www.apnorc.org/PDFs/Long%20Term%20Care/AP_NORC_Long%20Term%20Care%20Perception_FINAL%20REPORT.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Finkelstein A, McGarry K. Multiple dimensions of private information: evidence from the long-term care insurance market. Am Econ Rev. 2006;96(4):938–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iwasaki M, McCurry SM, Borson S, Jones JA. The future of financing for long-term care: the Own Your Future campaign. J Aging Soc Policy. 2010;22(4):379–93. doi: 10.1080/08959420.2010.507584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lusardi A, Mitchell OS. Financial literacy and retirement preparedness: evidence and implications for financial education. Bus Econ. 2007;42(1):35–44. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schaber PL, Stum MS. Factors impacting group long-term care insurance enrollment decisions. J Fam Econ Iss. 2007;28(2):189–205. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brown JR, Goda GS, McGarry K. Long-term care insurance demand limited by beliefs about needs, concerns about insurers, and care available from family. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31(6):1294–302. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Taylor P, Passel J, Fry R, Morin R, Wang W, Velasco G, et al. Washington (DC): Pew Research Center; 2010. Mar 18, [2014 Oct 17]. The return of the multi-generational family household. [Internet]. Available from: http://pewsocialtrends.org/files/2010/10/752-multi-generational-families.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Angier N. The changing American family. New York Times; 2013. Nov 25, [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cherlin A. Demographic trends in the United States: a review of research in the 2000s. J Marriage Fam. 2010;72(3):403–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00710.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Robison J, Shugrue N, Fortinsky RH, Gruman C. Long-term supports and services planning for the future: implications from a statewide survey of Baby Boomers and older adults. Gerontologist. 2014;54(2):297–313. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnt094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Freedman VA, Spillman BC, Andreski PM, Cornman JC, Crimmins EM, Kramarow E, et al. Trends in late-life activity limitations in the United States: an update from five national surveys. Demography. 2013;50(2):661–71. doi: 10.1007/s13524-012-0167-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ruggles S, Alexander JT, Genadek K, Goeken R, Schroeder MB, Sobek M. Integrated Public Use Microdata Series: version 5.0 [machine-readable database] Minneapolis (MN): Minnesota Population Center; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kessler RC, Andrews G, Colpe LJ, Hiripi E, Mroczek DK, Normand SL, et al. Short screening scales to monitor population prevalences and trends in non-specific psychological distress. Psychol Med. 2002;32(6):959–76. doi: 10.1017/s0033291702006074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Long JS, Freese J. Regression models for categorical dependent variables using Stata. 2. College Station (TX): StataCorp LP; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 25.To access the Appendix, click on the Appendix link in the box to the right of the article online.

- 26.Carnick and Company. Colorado Springs (CO): Carnick and Company; 2001. May, [2014 Oct 17]. Long-term care: our next national crisis? A think tank sponsored by the National Endowment for Financial Education. [Internet]. Available from: http://www.carnick.com/ResourceLib/LTC_Final_Report.pdf. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.