Abstract

Objective

This study compares current public attitudes about drug addiction with attitudes about mental illness.

Methods

A web-based national public opinion survey (N=709) was conducted to compare attitudes about stigma, discrimination, treatment effectiveness, and policy support.

Results

Respondents hold significantly more negative views toward persons with drug addiction compared to those with mental illness. More respondents were unwilling to have a person with drug addiction marry into their family or work closely with them on a job. Respondents were more willing to accept discriminatory practices, more skeptical about the effectiveness of available treatments, and more likely to oppose public policies aimed at helping persons with drug addiction.

Conclusions

Drug addiction is often treated as a sub-category of mental illness, and health insurance benefits group these conditions together under the rubric of behavioral health. Given starkly different public views about drug addiction and mental illness, advocates may need to adopt differing approaches for advancing stigma reduction and public policy.

INTRODUCTION

Prior research indicates pervasive and persistent negative attitudes among Americans toward persons with mental illness. Data from the General Social Survey (GSS) comparing public views in 1999 and 2006 indicated surprisingly little change overtime in high rates of stigma -- in particular, the desire for social distance and perceptions about the dangerousness of persons with serious mental illness.1 Less information is available on public attitudes toward persons with drug addiction, and available data are dated. These data suggest that views of individuals with drug addiction are more negative when compared with mental illnesses.2 In the current environment, widespread efforts aimed to integrate services and policies for treating addiction into the mainstream of what we now refer to as “behavioral health.” From a clinical and delivery system perspective, this approach makes sense given sizable share of individuals with mental illness with co-occurring substance use disorder.3 It is unclear, however, whether this push toward integration reflects how the general public conceptualizes these conditions. We know little about how public attitudes about drug addiction differ from attitudes about mental illness. In this study, we conducted a web-based national public opinion study (N=709) to compare public attitudes in four domains: stigma; discrimination; treatment effectiveness and policy support.

DATA & METHODS

We designed and fielded a national public opinion survey (N=709) of adults ages 18+ between October 30 and December 2, 2013 using the survey research firm GfK Knowledge Networks (GfK). GfK has recruited obtained informed consent from a probability-based online panel of 50,000 adult members, including persons living in cell phone-only households, using equal probability sampling with a sample frame of residential addresses covering 97% of U.S. households. To minimize concerns about priming, the order of the survey items was randomized. The survey completion rate, defined as the proportion of GfK panel members randomly selected for this study who completed the survey, was 70.1%. The GfK panel recruitment rate was 16.6%.

Respondents were asked their attitudes about either drug addiction or mental illness. We used a split sample approach so that half of our 709 survey respondents were randomly assigned to answer each survey question with reference to drug addiction (N=347) and half with reference to mental illness (N=362). We compared their socio-demographic characteristics confirming no significant differences between these two groups (see Reviewer Technical Appendix).

First, we asked two stigma questions measuring desire for social distance from persons with drug addiction or mental illness. Respondents randomized to the mental illness version of the questions were asked: “[W]ould you be willing to have a person with mental illness marry into your family?” and “[W]ould you be willing to have a person with mental illness start working closely with you on a job?” For respondents randomized to the drug addiction variants of these items, the words “mental illness” were replaced by “drug addiction.” The question wording for these items was adapted from the 2006 General Social Survey.1 Second, to measure respondent attitudes about the acceptability of discrimination, we included three survey items (as above, with separate mental illness and drug addiction variants): “[D]iscrimination against people with drug addiction/mental illness is a serious problem”; “[E]mployers should be allowed to deny employment to a person with drug addiction/mental illness”, and “[L]andlords should be able to deny housing to a person with drug addiction/mental illness.” Third, we asked respondents about two items measuring their attitudes about the effectiveness of treatment: “[T]he treatment options for persons with drug addiction/mental illness are effective at controlling symptoms” and “[M]ost people with drug addiction/mental illness can, with treatment, get well and return to productive lives.” The latter item has been used in the GSS as a measure of recovery.1 Finally, we gauged respondent support for four different policy items: insurance parity, and government spending on treatment, housing, and job support. These items were worded as follows: “[D]o you favor or oppose requiring insurance companies to offer benefits for the treatment of drug addiction/mental illness that are equivalent to benefits for other medical services?”, “[Do] you favor or oppose increasing government spending on the treatment of drug addiction/mental illness?”, “[D]o you favor or oppose increasing government spending on programs to subsidize housing costs for people with drug addiction/mental illness?” and “[D]o you favor or oppose increasing government spending on programs that help people with drug addiction/mental illness find jobs and provide on-the-job support as needed?” All responses were measured using 7-point Likert scales.

We used Pearson chi-square to test whether public attitudes differed based whether respondents viewed the drug addiction or mental illness version of the item. In addition, we ran logistic regression models to examine the associations between respondent attitudes and their socio-demographic characteristics including age, gender, race and education, and their self-identified political affiliation (i.e., Republican, Independent, Democrat). All analyses incorporated survey weights to produce nationally representative estimates by accounting for panel selection deviations, panel non-response and attrition, and survey-specific non-response. (In the Reviewer Technical Appendix, we provided weighted and unweighted socio-demographic characteristics of survey respondents compared with national rates in the population using the 2013 U.S. Current Population Survey.) This study was determined to be exempt by the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health Institutional Review Board on September 4, 2013 (#00005331).

RESULTS

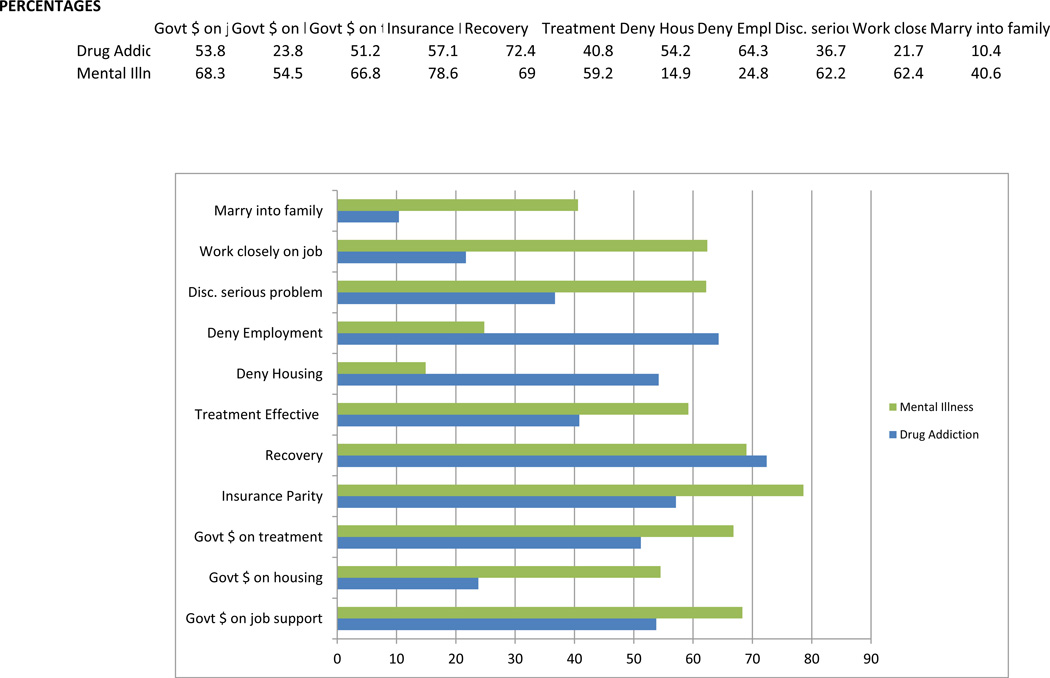

As the Figure indicates, Americans hold significantly more negative attitudes toward persons with drug addiction compared to persons with mental illness. We identified very high levels of desire for social distance in both groups; however, far more respondents were unwilling to have a person with drug addiction marry into their family (90% vs. 59%; p<.001) or work closely with them on a job (78% vs. 38%; p<.001) compared with a person with mental illness.

FIGURE.

Public Attitudes about Persons with Drug Addiction (N=347) Mental Illness (N=362), 2013

7-pt Likert scales were collapsed to dichotomous stigma, discrimination, treatment effectiveness, and policy support measures. Pearson chi-square used to test whether attitudes differed based whether respondents viewed the drug addiction or mental illness version of each survey item. *p<.05; **p<.01; ***p<.001

Respondents were also more likely to view discrimination against persons with drug addiction as “not a serious problem” compared with discrimination against persons with mental illness (63% vs. 38%; p<.001). Sixty-four percent of respondents thought employers should be allowed to deny employment to persons with drug addiction compared with 25% who held a similar view for persons with mental illness (p<.001). Similarly, 54% thought landlords should be allowed to deny housing to a person with drug addiction compared to only 15% who had a similar view for persons with mental illness (p<.001).

With regard to beliefs about treatment effectiveness and recovery, respondents were significantly more likely to view treatment options for persons with drug addiction as ineffective in controlling symptoms compared with treatment options for persons with mental illness (59% vs. 41%, p<.05). However, a roughly equal share rejected the concept that persons with these conditions could, with treatment, get well and return to productive lives (28% vs. 31%).

Respondents reported higher levels of opposition to public policies directed at helping people with drug addiction compared to persons with mental illness. Respondents were significantly more likely to oppose insurance parity for drug addiction compared with mental illness (43% vs. 21%, p<.001), to oppose increased government spending on drug addiction treatment compared to treatment for mental illness (49% vs. 33%, p<.001), to oppose increased government spending on programs to subsidize housing costs for people with drug addiction compared to mental illness (76% vs. 45%, p<.001), and to oppose government spending on job support programs for people with drug addiction compared with mental illness (46% vs. 32%, p<.01).

Finally, we found that political affiliation was, in almost all cases, significantly associated with support for the four policies in both the drug addiction sample and the mental illness sample controlling for respondent demographic characteristics. In both the drug abuse and mental illness arms, respondents self-identifying as Democrats were significantly less likely than Republicans and Independents to oppose equivalent insurance benefits or to oppose increased government spending on treatment, housing and job support (results not shown and available from authors upon request).

DISCUSSION

These findings indicate that the American public holds significantly more negative attitudes toward persons with drug addiction compared with persons with mental illness, and those attitudes translate into lower support for policies to improve equity in insurance coverage or for government funding toward improving treatment rates, housing and job support options. Less sympathetic views may result at least in part from societal ambivalence over whether to regard substance abuse problems as medical conditions to be treated (similar to other chronic health conditions such as diabetes or heart disease) or personal failings to be overcome. More so than mental illness, addiction is often viewed as a moral shortcoming,1 and the illegality of drug use reinforces this perspective. It is likely that socially unacceptable behavior accompanying drug addiction (e.g., impaired driving, crime) heightens society’s condemnation.

The only dimension in which attitudes did not differ was the belief in the potential for recovery. However, the belief in recovery may be driven by a pull-yourself-up-by-your-bootstraps attitude in the context of drug addiction rather than an embrace of the philosophy that has driven the recovery movement in the context of persons with lived experience with mental illness.

One potential limitation of our approach is that, when asked about “mental illness,” some respondents may have included their views on drug addiction embedded in their responses, which would have the practical effect of masking even greater differences in attitudes. Another limitation is that we are not able distinguish among specific conditions within mental illness and drug addiction. We would expect that the desire for social distance from persons with schizophrenia versus an anxiety disorder might differ, or that public perceptions about the acceptability of discrimination might depend on whether a person had developed an addiction to prescription pain medication following a back injury versus a heroin addiction. Likewise, we do not compare public attitudes on alcohol abuse in this study. Understanding public attitudes is critical given that the prevalence of alcohol dependence is much higher than for any other drug.4

CONCLUSION

While the behavioral health field is increasingly emphasizing integration, our results suggest that it may be necessary for advocates to adopt differing approaches for advancing stigma reduction and policy goals given underlying differences in beliefs and attitudes about drug addiction and mental illness among the public. One approach to stigma-reduction holds promise. Research on HIV5,6 supports the notion that increasing public recognition about treatability can reduce stigma and discrimination toward those affected. It would be worthwhile to better understand how portrayal of addiction as treatable might lower stigma among a general public who has grown accustom to seeing media portrayals of untreated individuals with mental illness or drug addiction as disheveled, often homeless and potentially dangerous.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Drs. Barry and McGinty gratefully acknowledge funding from AIG Inc. (PI: Barry), Dr. Barry acknowledges funding from NIDA R01 DA026414 (PI: Barry) and Drs. Barry, McGinty and Goldman gratefully acknowledge funding from NIMH 1R01MH093414-01A1 (PI: Barry). The data for this study were collected through Time-Sharing Experiments for the Social Sciences (TESS), National Science Foundation (grant 0818839). Dr. Pescosolido gratefully acknowledges support from an infrastructure grant from the College of Arts and Sciences, Indiana University.

Contributor Information

Colleen L Barry, Email: cbarry@jhsph.edu, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Health Policy and Managment, 624 N. Broadway, Hampton House 403, Baltimore, Maryland 21205.

Emma Elizabeth McGinty, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health - Health Policy and Management, Baltimore, Maryland.

Bernice Pescosolido, Indiana University.

Howard H. Goldman, University of Maryland School of medicine, 10600 TROTTERS TRAIL, POTOMAC, Maryland 20854

REFERENCES

- 1.Pescosolido BA, Martin JK, Long JS, Medina TR, Phelan JC, Link BG. A Disease Like Any Other? A Decade of Change in Public Reactions to Schizophrenia, Depression, and Alcohol Dependence. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2010;167:1321–1330. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09121743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Link BG, Phelan JC, Bresnahan M, Stueve A, Pescosolido BA. Public Conceptions of Mental Illness: Labels, Causes, Dangerousness and Social Distance. American Journal of Public Health. 1999;89(9):1328–1333. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.9.1328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kessler RC, Nelson CB, McGonagle KA, Edlund MJ, Frank RG, Leaf PJ. The Epidemiology of Co-occurring Addictive and Mental Disorders: Implications for Prevention and Service Utilization. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1996;66(1):17–31. doi: 10.1037/h0080151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Summary of Findings from the 2000 National Household Survey on Drug Abuse. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Department of Health and Human Services; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wolfe WR, Weiser SD, Leiter K, et al. The Impact of Universal Access to Antiretroviral Therapy on HIV Stigma in Botswana. American Journal of Public Health. 2008;98(10):1865–1871. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2007.122044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abadia-Barrero CE, Castro A. Experiences of Stigma and Cccess to HAART in Children and Adolescents living with HIV/AIDS in Brazil. Social Science and Medicine. 2006;62(5):1219–1228. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.