Abstract

OBJECTIVE

To assess the determinants of exclusive breastfeeding abandonment.

METHODS

Longitudinal study based on a birth cohort in Viçosa, MG, Southeastern Brazil. In 2011/2012, 168 new mothers accessing the public health network were followed. Three interviews, at 30, 60, and 120 days postpartum, with the new mothers were conducted. Exclusive breastfeeding abandonment was analyzed in the first, second, and fourth months after childbirth. The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale was applied to identify depressive symptoms in the first and second meetings, with a score of ≥ 12 considered as the cutoff point. Socioeconomic, demographic, and obstetric variables were investigated, along with emotional conditions and the new mothers’ social network during pregnancy and the postpartum period.

RESULTS

The prevalence of exclusive breastfeeding abandonment at 30, 60, and 120 days postpartum was 53.6% (n = 90), 47.6% (n = 80), and 69.6% (n = 117), respectively, and its incidence in the fourth month compared with the first was 48.7%. Depressive symptoms and traumatic delivery were associated with exclusive breastfeeding abandonment in the second month after childbirth. In the fourth month, the following variables were significant: lower maternal education levels, lack of homeownership, returning to work, not receiving guidance on breastfeeding in the postpartum period, mother’s negative reaction to the news of pregnancy, and not receiving assistance from their partners for infant care.

CONCLUSIONS

Psychosocial and sociodemographic factors were strong predictors of early exclusive breastfeeding abandonment. Therefore, it is necessary to identify and provide early treatment to nursing mothers with depressive symptoms, decreasing the associated morbidity and promoting greater duration of exclusive breastfeeding. Support from health professionals, as well as that received at home and at work, can assist in this process.

Keywords: Breastfeeding; Weaning; Bottle Feeding; Depression, Postpartum; Risk Factors; Socioeconomic Factors; Cross-Sectional Studies

Abstract

OBJETIVO

Avaliar os determinantes ao abandono do aleitamento materno exclusivo.

MÉTODOS

Estudo longitudinal baseado em coorte de nascimentos realizado em Viçosa, Minas Gerais. Acompanharam-se 168 puérperas provenientes da rede pública de saúde em 2011/2012. Foram realizadas três entrevistas com as puérperas: aos 30, 60 e 120 dias após o parto. O abandono do aleitamento materno exclusivo foi analisado no segundo e quarto meses após o parto. Aplicou-se escala Edinburgh Post-Natal Depression Escale para identificar os sintomas depressivos no primeiro e segundo encontros, adotando-se o ponto de corte ≥ 12. Foram investigadas variáveis socioeconômicas, demográficas, obstétricas, condições emocionais e rede social da puérpera durante a gestação e puerpério.

RESULTADOS

As prevalências de abandono do aleitamento materno exclusivo aos 30, 60 e 120 dias após o parto foram 53,6% (n = 90), 47,6% (n = 80) e 69,6% (n = 117), respectivamente, e sua incidência no quarto mês em relação ao primeiro foi 48,7%. Sintomas de depressão pós-parto e parto traumático associaram-se com abandono do aleitamento materno exclusivo no segundo mês após o parto. No quarto mês, mostraram significância as variáveis: menor escolaridade materna, não possuir imóvel próprio, ter voltado a trabalhar, não ter recebido orientações sobre amamentação no puerpério, reação negativa da mulher com a notícia da gestação e não receber ajuda do companheiro com a criança.

CONCLUSÕES

Fatores psicossociais e sociodemográficos se mostraram fortes preditores do abandono precoce do aleitamento materno exclusivo. Dessa forma, é necessário identificar e tratar precocemente as nutrizes com sintomatologia depressiva, reduzindo a morbidade a ela associada e promovendo maior duração do aleitamento materno exclusivo. Os profissionais de saúde, bem como o apoio recebido no lar e no trabalho, podem beneficiar esse processo.

INTRODUCTION

Breastfeeding offers benefits to infants’ health from a nutritional, gastrointestinal, immunological, psychological, and developmental perspective, and it also offers a platform for establishing mother-infant bonding. 22 To combat early malnutrition and decrease infant morbidity and mortality, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) until the sixth month of life and complementary breastfeeding until age two years or beyond. 23

However, at least 85.0% of mothers worldwide do not follow these recommendations, and only 35.0% of infants aged < 4 months are exclusively breastfed. 22 In Brazil, this rate is only 23.3%. a

The principal factors that determine breastfeeding abandonment are low income, 17 low education level 13 and maternal employment, 20 as well as psychosocial factors, particularly lack of assistance from partners for infant care 13 and symptoms of postpartum depression. 8

The possible negative association between postpartum depression and breastfeeding has been widely discussed in the current literature regarding the determinants of feeding practices in the first year postpartum (including breastfeeding and its duration). Studies show that the depressive symptoms negatively affect the EBF and duration of breastfeeding. 6 , 8 , 10 , 11

The factors hindering the maintenance of breastfeeding in mothers with depression and anxiety include antidepressant use, sleep deprivation, apathy, and depressive mood. 24 Some behaviors of depressed mothers, such as remoteness and disengagement from child care, negatively impact their infants. This less intense mother-infant interaction exposes infants to problems in emotional, behavioral, and cognitive development as well as malnutrition and physical health problems. 8

Identifying the main factors that lead to early breastfeeding abandonment can guide interventions that aim to improve EBF rates at six months postpartum.

The aim of this study was to evaluate the factors determining EBF abandonment.

METHODS

This was a longitudinal study based on data from the cohort “Condições de saúde e nutrição de crianças no primeiro ano de vida do município de Viçosa: um estudo de coorte” (“Health and nutrition conditions in infants in the first year of life in the city of Viçosa: a cohort study”). b

All the mothers of infants born in the city of Viçosa, MG, Southeastern Brazil in the period October 2011 to April 2012 were included. Exclusion criteria were hospitalization of the infant in the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU), the presence of syndromes or malformations that could compromise breastfeeding, twin pregnancy, and refusal to participate in the study.

Participants were invited to join the study around the 30th day after delivery, when the infants received scheduled vaccines. The other assessments were performed 60 and 120 days postpartum, also when the infants received scheduled vaccinations.

We followed 168 new mothers, which corresponds to 38.3% of the population of live births during the data collection period, and 19.1% of the live births in the city in the year of 2011 (n = 888). c

The outcome variable was early EBF abandonment, assessed at two and four months after giving birth. EBF was defined as infants receiving only breast milk from their mothers, no other liquids or solids, with the exception of drops or syrups containing vitamins, mineral supplements or medications. 23

Symptoms of postpartum depression, the main exposure variable, was evaluated at 30 and 60 days postpartum using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale developed by Cox, Holden, and Sagovsky 5 (1987) and validated for the Brazilian population. 18

This scale is the methodology most commonly used to identify symptoms or risk of postpartum depression and has a high correlation with other well-established measures of depression. 10 It consist of 10 questions with scores ranging from zero to three that correspond to the presence or intensity of depressive symptoms. The maximum total score is 30. 18 The cutoff considered was ≥ 12, 5 , 16 with 72.0% sensitivity, 88.0% specificity, positive-predictive value of 78.0%, and 83.0% accuracy. 18

The scale was completed by almost all the participants, and was administered orally by the interviewer to new mothers with low educational levels 5 or to those who requested it.

The socioeconomic and demographic variables investigated were as follows: age and maternal education, number of people in the household, home ownership, income, mothers studying or work outside of the home at four months after delivery, smoking, and alcohol use. Income was considered to be the monthly income of everyone residing in the household, including benefits received and informal employment.

The following obstetric variables were analyzed: parity, presence of breastfeeding guidelines during pregnancy and the postpartum period, delivery type, traumatic delivery, and infant birth weight.

The emotional conditions and social network of the new mothers during pregnancy and after delivery were also verified. The following issues were investigated: whether the pregnancy was planned, the reaction of the partner and the woman when they learned about the pregnancy, and emotional support from the partner during this period. The new mothers were asked if their partners helped in infant care in the first month after delivery and if they received emotional support from relatives or friends in the first two months after delivery.

Descriptive statistics were represented by means (standard deviation), median (range), and rates of prevalence and incidence. Bivariate analyses were performed using the Pearson’s Chi-square test, the linear trend test or Fisher’s test, when necessary.

Multivariate analysis was performed using Poisson regression with robust variance adjustment, obtaining a prevalence ratio and its respective 95% confidence interval. This type of regression was chosen because the dependent variable had > 10.0% prevalence; in this case, the odds ratio overestimates the rate of prevalence. 2 The stepwise backward selection procedure was used, where all variables with p-values of < 0.20 in bivariate analysis were inserted into the multivariate model. The criteria for permanence in the model were a 5% significance level, importance to adjustment, or control variables. The heterogeneity or linear trend was evaluated by Wald test for each variable in the model. Survival analysis was applied to assess the time elapsed between birth and EBF abandonment. This method presents the accumulated odds of survival versus survival time, 4 in other words, the proportion of mothers who practiced EBF versus the time that they persisted with it. Thus, survival time in this study was the time in months until EBF abandonment.

The analysis was performed using the survival curve, a graphic representation of the survival function on the vertical axis versus the survival time on the horizontal axis. The Kaplan-Meier technique was used to construct the curve, using survival times grouped into intervals of months. 4

The survival curve was built in bivariate analysis, according to the presence of depressive symptoms in the first or second month after childbirth. The data were entered and analyzed in Stata 9.1 software.

Assessments were conducted on 168 new mothers at 30, 60, and 120 days postpartum. The median age was 25 years (range 13-44 years). Of the participants, d 20.2% (n = 34) were adolescents (age < 20 years), and 38.7% (n = 65) had < 8 years of education.

The average birth weight of the infants was 3,234.6 g (SD = 466.6 g) and approximately 29.0% had low birth weight (≤ 2,500 g).

The study was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the Universidade Federal de Viçosa (official register 011202-CEP/UFV, 12/16/2011). All patients participating in the study signed the free and informed consent form.

RESULTS

The incidence of EBF abandonment in the first, second, and fourth month after birth was 53.6% (n = 90), 47.6% (n = 80), and 69.6% (n = 117), respectively. The incidence in the fourth month compared with the first was 48.7%; among the 78 infants receiving EBF in the first month after childbirth, 38 were given other foods in the fourth month.

In the bivariate analysis, mothers who resided in households with five or more residents, had a traumatic delivery, had an unplanned pregnancy, and showed symptoms of postpartum depression had a higher chance of EBF abandonment at two months. At four months, EBF abandonment was more common among mothers who had less education, had gone back to work, had not received breastfeeding guidance in the postpartum period, had an unplanned pregnancy, were not pleased with or were indifferent to the news of the pregnancy, and those whose partners did not help in infant care in the first month (Table 1, Table 2, and Table 3).

Table 1. Prevalence and prevalence ratio for exclusive breastfeeding abandonment before two and four months after giving birth, according to socioeconomic and demographic characteristics. Viçosa, MG, Southeastern Brazil, 2011-2012.

| Variable | n | % | 2 months | 4 months | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||||

| Prevalence (%) | PR | 95%CI | pa | Prevalence (%) | PR | 95%CI | pa | |||

| Age (years) | ||||||||||

| ≥ 20 | 34 | 79.8 | 47.3 | 1 | 0.478 | 67.16 | 1 | 0.165 | ||

| 13 |- 20 | 134 | 20.2 | 52.9 | 1.14 | 0.79;1.65 | 79.41 | 1.18 | 0.95;1.45 | ||

| Income | Continuous variable | 0.99 | 0.99;1 | 0.837 | Continuous variable | 0.99 | 0.99;1 | 0.146 | ||

| Education (years) | ||||||||||

| ≥ 12 | 28 | 16.7 | 32.1 | 1 | 0.199 | 39.3 | 1 | 0.000 | ||

| 9 to 11 | 75 | 44.6 | 50.7 | 1.57 | 0.87;2.82 | 72.0 | 1.83 | 1.13;2.97 | ||

| 0 to 8 | 52 | 31.0 | 50.8 | 1.57 | 0.87;2.85 | 80.0 | 2.03 | 1.26;3.28 | ||

| Homeownership | ||||||||||

| Yes | 100 | 59.5 | 47.0 | 1 | 0.846 | 65.0 | 1 | 0.112 | ||

| No | 68 | 40.5 | 48.5 | 1.03 | 0.74;1.42 | 76.5 | 1.17 | 0.96;1.43 | ||

| Number of persons in household | ||||||||||

| 2 to 4 | 116 | 69.1 | 42.2 | 1 | 0.037 | 65.52 | 1 | 0.082 | ||

| ≥ 5 | 52 | 30.9 | 59.6 | 1.41 | 1.03;1.92 | 78.85 | 1.20 | 0.99;1.46 | ||

| Returned to study or work after 4 months | ||||||||||

| No | – | – | – | – | – | – | 64.3 | 1 | 0.013 | |

| Yes | – | – | – | – | – | 85.5 | 1.32 | 1.09;1.59 | ||

| Smoking | ||||||||||

| No | 159 | 94.6 | 46.5 | 1 | 0.240 | 68.55 | 1 | 0.197 | ||

| Yes | 9 | 5.4 | 66.7 | 1.43 | 0.87;2.34 | 88.89 | 1.29 | 1;1.67 | ||

| Alcoholic beverages | ||||||||||

| No | 154 | 91.7 | 45.7 | 1 | 0.456 | 68.83 | 1 | 0.448 | ||

| Yes | 14 | 8.3 | 57.1 | 1.22 | 0.75;1.98 | 78.57 | 1.14 | 0.85;1.53 | ||

a Pearson’s Chi-square test.

Table 2. Prevalence and prevalence ratio for exclusive breastfeeding abandonment before two and four months after giving birth, according to obstetric conditions and infant health. Viçosa, MG, Southeastern Brazil, 2011-2012.

| Variable | n | % | 2 months | 4 months | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||||

| Prevalence (%) | PR | 95%CI | pa | Prevalence (%) | PR | 95%CI | pa | |||

| Prematurity | ||||||||||

| No | 169 | 95.2 | 47.5 | 1 | 0.890 | 69.4 | 1 | 0.736 | ||

| Yes | 8 | 4.8 | 50.0 | 1.05 | 0.51;2.14 | 75.0 | 1.08 | 0.71;1.63 | ||

| Birth weight (g) | ||||||||||

| ≥ 3,000 | 119 | 70.8 | 47.0 | 1 | 0.821 | 67.2 | 1 | 0.289 | ||

| < 3,000 | 49 | 29.2 | 48.9 | 1.04 | 0.73;1.46 | 75.5 | 1.12 | 0.91;1.37 | ||

| Delivery type | ||||||||||

| Normal | 57 | 34.1 | 49.1 | 1 | 78.9 | 1 | 0.055 | |||

| Caesarean section | 110 | 65.9 | 46.4 | 0.94 | 0.67;1.31 | 0.735 | 64.5 | 0.81 | 0.67;0.99 | |

| Traumatic delivery | ||||||||||

| No | 115 | 76.7 | 43.5 | 1 | 0.021 | 66.1 | 1 | 0.058 | ||

| Yes | 35 | 23.3 | 65.7 | 1.51 | 1.09;2.07 | 82.9 | 1.25 | 1.02;1.53 | ||

| Parity | ||||||||||

| Multiparous | 65 | 38.7 | 43.0 | 1 | 0.349 | 76.9 | 1 | 0.103 | ||

| Primiparous | 103 | 61.3 | 50.5 | 1.17 | 0.83;1.64 | 65.0 | 0.84 | 0.69;1.02 | ||

| Received guidance on breastfeeding in prenatal care | ||||||||||

| Yes | 78 | 46.7 | 51.3 | 1 | 0.413 | 73.1 | 1 | 0.342 | ||

| No | 89 | 53.3 | 44.9 | 0.87 | 0.63;1.20 | 66.3 | 0.90 | 0.74;1.10 | ||

| Received guidance on breastfeeding in the postpartum period | ||||||||||

| Yes | 120 | 71.4 | 43.3 | 1 | 0.079 | 65.0 | 1 | 0.039 | ||

| No | 48 | 28.6 | 58.3 | 1.34 | 0.98;1.34 | 81.2 | 1.25 | 1.03;1.51 | ||

a Pearson’s Chi-square test.

Table 3. Prevalence and prevalence ratio for exclusive breastfeeding abandonment before two and four months after giving birth, according to emotional conditions and social network. Viçosa, MG, Southeastern Brazil, 2011-2012.

| Variable | n | % | 2 months | 4 months | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||||

| Prevalence (%) | PR | 95%CI | pa | Prevalence (%) | PR | 95%CI | pa | |||

| Planned Pregnancy | ||||||||||

| Yes | 76 | 45.2 | 38.1 | 1 | 0.026 | 61.8 | 1 | 0.046 | ||

| No | 92 | 54.8 | 55.4 | 1.45 | 1.03;2.04 | 76.1 | 1.23 | 0.99;1.51 | ||

| Partner’s reaction to the news of the pregnancy | ||||||||||

| Pleased | 143 | 85.1 | 46.1 | 1 | 0.363 | 76.1 | 1 | 0.091 | ||

| Others | 25 | 14.9 | 50.0 | 1 | 0.82;1.22 | 84.0 | 1.25 | 1.01;1.53 | ||

| Mother’s reaction to the news of the pregnancy | ||||||||||

| Pleased | 135 | 80.4 | 45.1 | 1 | 0.201 | 65.9 | 1 | 0.034 | ||

| Others | 33 | 19.6 | 57.6 | 1.09 | 0.94;1.27 | 84.8 | 1.28 | 1.06;1.55 | ||

| Partner’s support in pregnancy | ||||||||||

| Significant/± | 157 | 93.5 | 43.5 | 1 | 0.271b | 68.1 | 1 | 0.113b | ||

| Little/None | 11 | 6.5 | 63.6 | 1.36 | 0.84;2.20 | 90.9 | 1.33 | 1.07;1.65 | ||

| Partner’s help in infant care | ||||||||||

| Yes | 48 | 28.6 | 45.7 | 1 | 0.800 | 58.3 | 1 | 0.044 | ||

| No | 120 | 71.4 | 48.1 | 1.05 | 0.70;1.57 | 74.2 | 1.27 | 0.97;1.65 | ||

| Emotional support from relatives or friends | ||||||||||

| Yes | 161 | 96.4 | 47.8 | 1 | 0.917 b | 70.2 | 1 | 0.856b | ||

| No | 6 | 3.6 | 50.0 | 1.04 | 0.46;2.37 | 66.7 | 0.94 | 0.53;1.69 | ||

| PPD Symptoms | ||||||||||

| No | 141 | 83.9 | 42.5 | 1 | 0.003 | 66.7 | 1 | 0.055 | ||

| Yes | 27 | 16.1 | 74.1 | 1.74 | 1.29;2.33 | 85.2 | 1.27 | 1.04;1.55 | ||

PPD: Postpartum depression

a Pearson’s Chi-square test.

b Fisher exact test.

Multiple regression analysis for the second month after childbirth showed that only the variables depressive symptoms and traumatic delivery maintained their significance in the model. In the fourth month after birth, early interruption of EBF was associated with lower maternal education levels, lack of homeownership, returning to work, not receiving guidance on breastfeeding in the postpartum period, mother’s negative reaction to the news of pregnancy, and not receiving help in infant care child from her partner (Table 4).

Table 4. Results for multivariate analyses of the model for exclusive breastfeeding abandonment at two and four months after giving birth. Viçosa, MG, Southeastern Brazil, 2011-2012.

| Variable Time in months after delivery | PRadjusted | 95%CI | pa |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 months | |||

| PPD Symptoms | |||

| No | 1 | 0.002 | |

| Yes | 1.61 | 1.19;2.19 | |

| Traumatic delivery | |||

| No | 1 | 0.035 | |

| Yes | 1.40 | 1.02;2.91 | |

| 4 months | |||

| Education (years) | |||

| ≥ 12 | 1 | ||

| 9 to 11 | 2.01 | 1.28;3.17 | 0.002 |

| 0 to 8 | 2.15 | 1.36;3.38 | 0.001 |

| Home ownership | |||

| Yes | 1 | ||

| No | 1.23 | 1.02;1.48 | 0.025 |

| Returned to work or study at four months | |||

| No | 1 | ||

| Yes | 1.33 | 1.09;1.63 | 0.004 |

| Received guidance on breastfeeding in the postpartum period | |||

| Yes | 1 | ||

| No | 1.21 | 1.01;1.45 | 0.038 |

| Mother’s reaction to the news of the pregnancy | |||

| Pleased | 1 | ||

| Others | 1.29 | 1.09;1.52 | 0.002 |

| Partner’s help with infant care | |||

| Yes | 1 | ||

| No | 1.33 | 1.04;1.70 | 0.023 |

PPD: Postpartum depression

a Wald test.

PPD: Postpartum depression

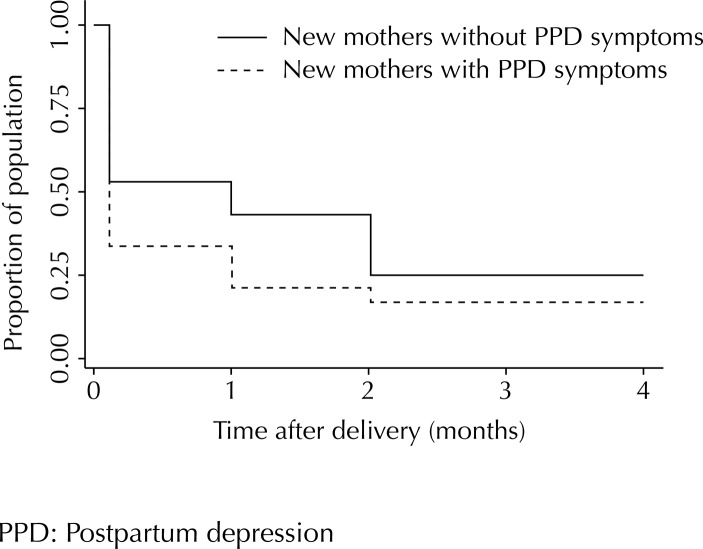

The Figure presents the survival curve showing EBF abandonment throughout the monitoring period, according to the presence of depressive symptoms.

Figure. Exclusively breastfed infants according to symptoms of postpartum depression. Viçosa, MG, Southeastern Brazil, 2011-2012.

DISCUSSION

A high incidence of EBF abandonment was found, with only about 30.0% of new mothers exclusively breastfeeding four months after birth. Although low, this value was higher than that found in Brazil (23.3%). a

Despite the increase in breastfeeding rates and EBF in Brazil after the implementation of the National Program to Encourage Breastfeeding in the early 1980s, a there is still a strong tendency toward early EBF abandonment, and the proportion of exclusively breastfed infants falls short of the WHO recommendations, which is serious in terms of child health.

In the present study, the incidence of EBF abandonment in the second month (47.6%) was less than that in the first month (53.6%). This is because, after the first month, the assisted new mothers were encouraged and guided according to ethical principles so as to exclusively breastfeed their infants until the sixth month.

The only variables that maintained their significance in the multivariate model for EBF abandonment at two months postpartum were symptoms of postpartum depression and traumatic delivery, indicating that emotional vulnerability is an important risk factor in this period.

Furthermore, the incidence of EBF abandonment among mothers with depressive symptoms was noticeably higher than in those without depressive symptoms, for all the months evaluated (Figure). In the second month after childbirth, 57.0% of the new mothers without depressive symptoms were exclusively breastfeeding their infants, compared with only 25.0% of those with depressive symptoms.

This result is explained by the fact that typical depressive symptoms may affect breastfeeding maintenance, such as anhedonia (decrease or loss of interest in previously enjoyable activities), insomnia, fatigue, irritability, agitation, psychomotor delay, feelings of unworthiness or guilt, and loss of concentration. 6 The chances that mothers with depressive symptoms or stress will maintain breastfeeding or EBF are decreased between four and 16 weeks after childbirth. 6 , 10 , 17

Depressive symptoms were associated with EBF abandonment only in the second month after childbirth. In the fourth month, despite the higher rate of EBF abandonment among the mothers with depressive symptoms (33.0%, compared with 15.0% of those without depressive symptoms) (Figure), this variable was not maintained in the multivariate model. This fact may result from the decreased prevalence of depressive symptoms between the first to the second month (14.3% and 9.5%, respectively), and it is possible that the prevalence of depressive symptoms decreased even more in the fourth month, similar to the results of the study by Haga et al. 10

Furthermore, according to ethical principles, the women diagnosed with depressive symptoms in this study were referred to appropriate treatment. Therefore, it is expected that four months after giving birth, they were already receiving treatment, and that the frequency of depressive symptoms was lower.

Traumatic delivery was also associated with EBF abandonment two months after giving birth. Although no studies with similar results were found in the literature, this relationship can be explained by the fact that dissatisfaction with childbirth is extremely significant for women and for increased psychological vulnerability to mood disorders in the postpartum period. 4

Mothers with lower education level and who had not received guidance on breastfeeding in postpartum period were the ones that most frequently abandoned EBF four months after delivery. Indeed, greater access to information about the benefits of EBF is a decisive factor in the nursing mother’s decision to breastfeed exclusively. 13

In Brazil, a major cause of early weaning is the lack of knowledge on the part of the mothers on breastfeeding practices, the quality of their milk, and its importance for the healthy development of the infant. 1 Formal support provided by health professionals in the postpartum period can positively influence the duration of breastfeeding 16 and promote EBF. 14 , 15

It is imperative that health professionals and services promote breastfeeding, highlighting the advantages of breastfeeding for the infant, mother, and family, and provide guidance on breastfeeding. 22 A study shows that mothers who were not well informed about breastfeeding planned to breastfeed for less time. 12 In this context, the Family Health Strategy (FHS) in Brazil is seen to be in an advantageous position to adopt guidelines on breastfeeding among pregnant and lactating women. 6

Lower income is associated with breastfeeding abandonment. 16 However, contrary to expectations, this relationship was not observed in the present study. The socioeconomic variables associated with the early EBF abandonment at four months postpartum were low maternal education levels, lack of homeownership, and returned to work before four months.

With regard to the association between greater abandonment of breastfeeding at four months postpartum among mothers whose family did not own their residence, it is possible that the form of occupation directly impacts the allocation of family income, especially in the population with lower purchasing power, which may direct a substantial portion of income towards paying rent. e Thus, home ownership seems to better represent the situation of socioeconomic vulnerability than actual income in this sample.

With regard to maternal employment, recent studies show that the rates of breastfeeding 19 and EBF 9 rapidly decline when women return to work. Consequently, maternity leave is an important protective factor for breastfeeding. Viana et al 21 found that mothers who worked outside the home and were given maternity leave had higher prevalence of EBF than those who worked outside their home but did not receive this benefit.

In Brazil, mothers are provided with 120 days of maternity leave without risk to employment or wages. f In 2010, the Congress approved, through the Citizen Company Program, extension of maternity leave from 120 days to 180 days by granting tax incentives. g However, data from the Brazilian Revenue Service show that as of February 2012, the rate of participation among organizations eligible for the program was only 10.0%. h According to Viana et al 21 many women who have paid employment do not receive maternity leave, either because employers are not in compliance with the law, or because they are in informal employment contracts.

Lack of information about pumping and storing breast milk to be offered to the child during the mother’s absence aggravates the situation related to the short period of maternity leave and informal work. 21

The mother’s immediate reaction other than “pleased” to news of the pregnancy was also a predictor of abandoning EBF by four months, which can be explained by the fact that women who want and plan a pregnancy are more dedicated to motherhood and the infant.

Nursing mothers who did not receive assistance from their partners for infant care also abandoned EBF. The association between partner support and the best indicators for breastfeeding was described in a study by Inoue et al 13 wherein positive attitude and support from the father favored longer duration of breastfeeding. Another study showed that mothers who talk to their partner about the infant’s health are more likely to continue EBF for six months. 14

This indicates that early identification and treatment of nursing mothers with depressive symptoms is necessary for decreasing associated morbidities, promoting better quality of life, and promoting longer duration of EBF. Health professionals are of great importance in this context because they can help women with depressive symptoms to receive the treatment needed to continue breastfeeding, as well as encourage and support EBF.

Moreover, there is a clear need for a support network that protects and promotes breastfeeding at home, especially involving the partners; in the workplace, by offering spaces suitable for breastfeeding, pumping and storing milk, as well as extending maternity leave to six months; and in health services, with health education activities focusing on breastfeeding and raising infants.

The main limitations of this study were losses in follow-up, typical of longitudinal studies, and possible selection biases. Of all the infants born in the municipality in 2011, 18.9% were followed up (n = 888 c ). At 30 days postpartum, 259 new mothers agreed to participate in the study. Of these, 200 returned for the second meeting at 60 days postpartum, and 168 composed the final sample, attending the third meeting at 120 days postpartum. Therefore, there was a loss of 91 women, 35.1% of the initial sample. However, there was no difference between the groups of loss and follow-up in terms of mean age (p = 0.4797), education (p = 0.47541), income (p = 0.9281; Student’s t test), and status of living with a partner (p = 0.222; Chi-square test).

HIGHLIGHTS.

The present study investigated the determinants of discontinuation of exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) up to four months after delivery. The World Health Organization and the Ministry of Health recommend EBF until the age of six months, and a nutritional complementation with breast milk from 6 to 24 months because of the benefits of this practice for child development.

Discontinuation of EBF was correlated with symptoms of postpartum depression and the occurrence of traumatic childbirth in the second month after birth; in the fourth month, discontinuation was correlated with low education of the mother, lack of ownership of the property of residence, return to work, lack of guidance on breastfeeding at the postpartum, discontentment of the companion with the pregnancy, and lack of support of the companion for child rearing.

Health care professionals should be trained to identify early signs of postpartum depression and encourage and support the EBF, considering that mothers with less education and without guidance are likely to breastfeed their children for less time. The Humanization of Childbirth Program is a positive step towards providing greater support to women, considering that 23.3% of pregnant women reported traumatic delivery and that trauma was positively correlated with the early discontinuation of EBF.

Maternity leave is a protective factor against breastfeeding. In addition to the extension of the period of maternity leave to 180 days with federal incentives for female employers, the authors indicate the need for offering suitable spaces for breastfeeding during working hours and for conducting the withdrawal of milk for proper storage.

These measures may stimulate EBF until the age of six months and the nutritional complementation for up to 24 months.

Rita de Cássia Barradas Barata

Scientific Editor

Funding Statement

Research supported by the Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de Minas Gerais (FAPEMIG – Protocol APQ 00846-11, de 2011 – Demanda Universal).

Footnotes

Research supported by the Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de Minas Gerais (FAPEMIG – Protocol APQ 00846-11, de 2011 – Demanda Universal).

Master’s funding for Machado MCM and Assis KF and doctoral funding for Oliveira FCC granted by Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES).

Ministério da Saúde, Secretaria de Atenção à Saúde, Departamento de Ações Programáticas e Estratégicas. II Pesquisa de Prevalência de Aleitamento Materno nas Capitais Brasileiras e Distrito Federal. Brasília (DF); 2009 [cited 2014 Ago 13]. (Série C. Projetos, Programas e Relatórios). Available from: http://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoes/pesquisa_prevalencia_aleitamento_materno.pdf

Birth cohort conducted in Viçosa, Minas Gerais. The objective was to understand the health conditions of the children born in the city between October 2011 and October 2012, evaluating their growth and development throughout the first year of life.

Ministério da Saúde. DATASUS. Informações de Saúde – TABNET. Estatísticas Vitais. Nascidos vivos. Minas Gerais. Ano de 2011. Available from: http://tabnet.datasus.gov.br/cgi/tabcgi.exe?sinasc/cnv/nvmg.def

World Health Organization. Los adolescentes. In: El estado físico: uso e interpretación de la antropometría. Geneva: WHO, 1995. p. 308-366. (Série de Informes Técnicos, 854).

Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. Censo Demográfico 2010: características da população e dos domicílios: resultados do universo. Rio de Janeiro; 2011.

Presidência da República, Casa Civil, Subchefia para Assuntos Jurídicos. Constituição da República Federativa do Brasil. Brasília (DF); 1988 [cited 2014 Ago 13]. Available from: http://www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/constituicao/constituicaocompilado.htm

Brasil. Decreto nº 7.052 de 23 de dezembro de 2009. Regulamenta a Lei nº 11.770, de 9 de setembro de 2008, que cria o Programa Empresa Cidadã, destinado à prorrogação da licença-maternidade, no tocante a empregadas de pessoas jurídicas. Diario Oficial Uniao. 24 dez 2009; Seção 1, p. 15.

Ministério da Fazenda, Secretaria da Receita Federal do Brasil [homepage]. Brasília (DF); s.d. [cited 2014 Ago 13]. Available from: http://www.receita.fazenda.gov.br

Based on the master’s dissertation of Machado MCM, titled: “Fatores associados ao estado emocional materno no período pós-parto e sua relação com a prática da amamentação”, presented to the Postgraduate Program in Nutritional Sciences in the Departamento de Nutrição e Saúde, Universidade Federal de Viçosa, in 2013.

REFERENCES

- 1.Azevedo DS, Reis ACS, Freitas LV, Costa PB, Pinheiro PNC, Damasceno AKC. Conhecimento de primíparas sobre os benefícios do aleitamento materno. Rev RENE. 2010;11(2):53–62. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barros AJ, Hirakata VN. Alternatives for logistic regression in cross-sectional studies: an empirical comparison of models that directly estimate the prevalence ratio. 2110.1186/1471-2288-3-21BMC Med Res Methodol. 2003;3 doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-3-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barros FC, Victora CG. Epidemiologia da saúde infantil: um manual para diagnósticos comunitários. São Paulo: Hucitec/UNICEF; 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Clement S. Psychological aspects of caesarean section. 10.1053/beog.2000.0152Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2001;15(1):109–126. doi: 10.1053/beog.2000.0152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cox JL, Holden JM, Sagovsky R. Detection of postnatal depression. Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. 10.1192/bjp.150.6.782Br J Psychiatry. 1987;150(6):782–786. doi: 10.1192/bjp.150.6.782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cruz EBS, Simões GL, Faisal-Cury A. Rastreamento da depressão pós-parto em mulheres atendidas pelo Programa de Saúde da Família. 10.1590/S0100-72032005000400004Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet. 2005;27(4):181–188. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cruz SH, Germano JA, Tomasi E, Facchini LA, Piccini RX, Thumé E. Orientações sobre amamentação: a vantagem do Programa de Saúde da Família em municípios gaúchos com mais de 100.000 habitantes no âmbito do PROESF. 10.1590/S1415-790X2010000200008Rev Bras Epidemiol. 2010;13(2):259–267. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dennis CL, McQueen K. The relationship between infant-feeding outcomes and postpartum depression: a qualitative systematic review. 10.1542/peds.2008-1629Pediatrics. 2009;123(4): doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Franco SC, Nascimento MBR, Reis MAM, Issler H, Grisi SJFE. Aleitamento materno exclusivo em lactentes atendidos na rede pública do município de Joinville, Santa Catarina, Brasil. 10.1590/S1519-38292008000300008Rev Bras Saude Matern Infant. 2008;8(3):291–297. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haga SM, Ulleberg P, Slinning K, Kraft P, Steen TB, Staff A. A longitudinal study of postpartum depressive symptoms: multilevel growth curve analyses of emotion regulation strategies, breastfeeding self-efficacy, and social support. 10.1007/s00737-012-0274-2Arch Womens Ment Health. 2012;15(3):175–184. doi: 10.1007/s00737-012-0274-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hasselmann MH, Werneck GL, Silva CVC. Symptoms of postpartum depression and early interruption of exclusive breastfeeding in the first two months of life. 10.1590/S0102-311X2008001400019Cad Saude Publica. 2008;24(Suppl 2) doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2008001400019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Idris NS, Sastroasmoro S, Hidayati F, Sapriani I, Suradi R, Grobbee DE, et al. Exclusive breastfeeding plan of pregnant Southeast Asian women: what encourages them? 10.1089/bfm.2012.0003Breastfeed Med. 2012;8(3):317–320. doi: 10.1089/bfm.2012.0003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Inoue M, Binns CW, Otsuka K, Jimba M, Matsubara M. Infant feeding practices and breastfeeding duration in Japan: a review. 1510.1186/1746-4358-7-15Int Breastfeed J. 2012;7(1) doi: 10.1186/1746-4358-7-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaneko A, Kaneita Y, Yokoyama E, Miyake T, Harano S, Suzuki K, et al. Factors associated with exclusive breast-feeding in Japan: for activities to support child-rearing with breast-feeding. 10.2188/jea.16.57J Epidemiol. 2006;16(2):57–63. doi: 10.2188/jea.16.57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khresheh R, Suhaimat A, Jalamdeh F, Barclay L. The effect of a postnatal education and support program on breastfeeding among primiparous women: a randomized controlled trial. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2011.02.001Int J Nurs Stud. 2011;48(9):1058–1065. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2011.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Labarere J, Gelbert-Baudino N, Ayral AS, Duc C, Berchotteau M, Bouchon N, et al. Efficacy of breastfeeding support provided by trained clinicians during an early, routine, preventive visit: a prospective, randomized, open trial of 226 mother-infant pairs. 10.1542/peds.2004-1362Pediatrics. 2005;115(2): doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nishioka E, Haruna M, Ota E, Matsuzaki M, Murayama R, Yoshimura K, et al. A prospective study of the relationship between breastfeeding and postpartum depressive symptoms appearing at 1-5 months after delivery. 10.1016/j.jad.2011.04.027J Affect Disord. 2011;133(3):553–559. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Santos MFS, Martins FC, Pasquali L. Escalas de auto- avaliação de depressão pós-parto: estudo no Brasil. Rev Psiquiatr Clin. 1999;26(2):90–95. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Skafida V. Juggling work and motherhood: the impact of employment and maternity leave on breastfeeding duration: a survival analysis on growing up in Scotland data. 10.1007/s10995-011-0743-7Matern Child Health J. 2012;16(2):519–527. doi: 10.1007/s10995-011-0743-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Valdés V, Puggin E, Schooley J, Catalán S, Aravena R. Clinical support can make the difference in exclusive breastfeeding success among working women. 10.1093/tropej/46.3.149J Trop Pediatr. 2000;46(3):149–154. doi: 10.1093/tropej/46.3.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vianna RPT, Rea MF, Venancio SI, Escuder MM. A prática de amamentar entre mulheres que exercem trabalho remunerado na Paraíba, Brasil: um estudo transversal. 10.1590/S0102-311X2007001000015Cad Saude Publica. 2007;23(10):2403–2409. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2007001000015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.World Health Organization. UNICEF Global strategy for infant and young child feeding. Geneva: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 23.World Health Organization Part 1: Definitions; Indicators for assessing infant and young child feeding practices: conclusions of a consensus meeting held; 6-8 November 2007; Washington, DC, USA. Geneva: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zauderer C. Postpartum depression and breastfeeding: what should a new mother do? 10.1111/j.1552-6909.2011.01244_15.xJ Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2011;40(Suppl 1) [Google Scholar]