Abstract

The extracytoplasmic function sigma factor σH is responsible for the heat and oxidative stress response in Corynebacterium glutamicum. Due to the hierarchical nature of the regulatory network, previous transcriptome analyses have not been able to discriminate between direct and indirect targets of σH. Here, we determined the direct genome-wide targets of σH using chromatin immunoprecipitation with microarray technology (ChIP-chip) for analysis of a deletion mutant of rshA, encoding an anti-σ factor of σH. Seventy-five σH-dependent promoters, including 39 new ones, were identified. σH-dependent, heat-inducible transcripts for several of the new targets, including ilvD encoding a labile Fe-S cluster enzyme, dihydroxy-acid dehydratase, were detected, and their 5′ ends were mapped to the σH-dependent promoters identified. Interestingly, functional internal σH-dependent promoters were found in operon-like gene clusters involved in the pentose phosphate pathway, riboflavin biosynthesis, and Zn uptake. Accordingly, deletion of rshA resulted in hyperproduction of riboflavin and affected expression of Zn-responsive genes, possibly through intracellular Zn overload, indicating new physiological roles of σH. Furthermore, sigA encoding the primary σ factor was identified as a new target of σH. Reporter assays demonstrated that the σH-dependent promoter upstream of sigA was highly heat inducible but much weaker than the known σA-dependent one. Our ChIP-chip analysis also detected the σH-dependent promoters upstream of rshA within the sigH-rshA operon and of sigB encoding a group 2 σ factor, supporting the previous findings of their σH-dependent expression. Taken together, these results reveal an additional layer of the sigma factor regulatory network in C. glutamicum.

INTRODUCTION

Corynebacterium glutamicum is a high-GC-content Gram-positive soil bacterium that belongs to the order Actinomycetales, which includes the genera Mycobacterium and Streptomyces. While C. glutamicum has been used in industrial production of the amino acids l-glutamate and l-lysine (1, 2), recent studies demonstrate its use as a platform for microbial production of other valuable compounds, including organic acids, diamines, and biofuels (3–9). Furthermore, C. glutamicum is also important as a model organism for closely related pathogenic species, such as Corynebacterium diphtheriae and Mycobacterium tuberculosis.

In bacteria, extracytoplasmic function (ECF) σ factors that direct RNA polymerase (RNAP) to specific promoters play a pivotal role in cellular response to environmental stress conditions (10, 11). In C. glutamicum, σH, one of five ECF σ factors encoded in the genome, is responsible for the response to heat shock and oxidative stress. Involvement of C. glutamicum σH in the heat shock response was first demonstrated in transcriptional regulation of the ATP-dependent protease subunits ClpP1/ClpP2 and ClpC, which are involved in protein quality control (12). Furthermore, σH is required for upregulation of the trxB gene encoding thioredoxin reductase in response to oxidative stress caused by diamide, and the sigH mutant is more susceptible to diamide than the wild type (13). Our previous microarray analyses of sigH-deficient and sigH-overexpressing strains revealed that the σH regulon additionally includes various genes implicated in protection of cells against oxidative damage, such as several molecular chaperones, Fe-S cluster assembly proteins, methionine sulfoxide reductase, and some dehydrogenases (14).

The σH regulon of C. glutamicum partially resembles the regulons of σH orthologs in Actinomycetales, i.e., M. tuberculosis σH and Streptomyces coelicolor σR (15–21). Moreover, the consensus promoter sequence recognized by these σH orthologs is almost identical to that recognized by C. glutamicum σH (22, 23). Activity of the σH orthologs is regulated by stress-sensitive, reversible binding to an anti-σ factor (22, 23), which is encoded by the gene immediately downstream of the σ factor gene. The anti-σ factor RsrA for σR in S. coelicolor is a founding member of the Zn-containing anti-σ (ZAS) family and possesses a conserved HXXXCXXC motif which is required for Zn association and redox sensing (18, 23). Thus, the σR-RsrA regulatory system represents bacterial thiol-based sensor-regulators (24). It was recently reported that in C. glutamicum, rshA lying immediately downstream of sigH encodes an anti-σ factor of σH and that the sigH regulon genes are upregulated in the rshA mutant (25). A microarray analysis of a deletion mutant of the anti-σ factor RshA reveals that σH also controls genes encoding the DNA repair system and components of proteasome machinery (25).

The C. glutamicum σH regulon also includes genes for the stress-induced regulators HspR for molecular chaperones (14), ClgR for ATP-dependent proteases and DNA repair (26), SufR for Fe-S cluster assembly proteins (27), and WhiB-like proteins putatively involved in gene expression in the stationary phase (28, 29). Moreover, genes encoding a primary-like σ factor, σB (14), and another ECF σ factor, σM (27), are under the control of σH. Thus, σH is positioned at the top layer of the transcriptional regulatory network controlling cellular stress responses. Because of the complex hierarchical nature of the regulatory network, genes directly regulated by σH are tentatively predicted by the upstream presence of the consensus promoter sequence (G/T)GGAA-N17–20-(T/C)GTT (14, 25).

In this study, we performed a chromatin immunoprecipitation in conjunction with microarray (ChIP-chip) analysis to comprehensively identify the direct targets of σH in C. glutamicum. The ChIP-chip analysis using an rshA mutant reveals 74 new σH regulon members, some of which are shown to be subject to σH-dependent regulation in response to heat shock. The new targets of σH are related to the availability of cofactors such as the Fe-S cluster and flavins. An uptake system for Zn, which also functions as a cofactor, is also identified as a new member of the σH regulon. In addition to σB and σM, the primary σ factor, σA, is newly added to the σH regulon, revealing regulatory interaction among the σ factors. These findings provide new insights into the functions of σH in the stress response and in the structure of the transcriptional regulatory network in C. glutamicum. Moreover, the C. glutamicum σH regulon defined here has some components in common with the S. coelicolor σR regulon, which has been recently identified by ChIP-chip analysis (30), indicating functional conservation of the σH orthologs among Actinomycetales.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains, plasmids, oligonucleotides, and culture conditions.

Strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Table S1 in the supplemental material. Oligonucleotide primers used are listed in Table S2. For genetic manipulation, Escherichia coli strains were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium at 37°C. C. glutamicum strains were grown in nutrient-rich A medium (31) with 4% glucose at 33°C. When appropriate, the media were supplemented with antibiotics. The final antibiotic concentrations for E. coli were 50 μg of ampicillin ml−1 and 50 μg of kanamycin ml−1; for C. glutamicum kanamycin at 50 μg ml−1 was used. Heat shock treatment of exponentially growing C. glutamicum strains in A medium containing 1% glucose was performed at 45°C for 15 min as described previously (14).

Construction of mutant strains.

The FLAG-coding sequence was introduced to the 5′ end of the sigH gene by overlapping PCR using overlapping primer pairs (see Table S2 in the supplemental material), as described previously (32). The resulting DNA fragment was cloned into suicide vector pCRA725 (3), yielding pCRC623. Similarly, for deletion mutants of sigH and rshA, two suicide plasmids, pCRC624 and pCRC625, which carry the upstream and downstream regions of these genes, respectively, were constructed based on pCRA725. For deletion of the rshA gene of a strain chromosomally carrying FLAG-tagged sigH, the upstream and downstream regions of rshA were amplified by PCR using genomic DNA extracted from the FLAG-sigH strain as a template and cloned into pCRA725, yielding pCRC626. To introduce a point mutation into the −10 region of the znuC1 promoter, the mutated promoter and the upstream and downstream regions of the promoter were cloned into pCRA725, yielding pCRC627. These suicide plasmids were introduced into C. glutamicum by electroporation. Screening for the mutants using the conditional lethal effect of the sacB gene on pCRA725 was performed as described previously (3). Introduction of the tag into the sigH gene on the chromosome was confirmed by direct sequencing of a PCR product, which was amplified using primers rshAFW_del and rshARV_del (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). Deletion of the respective gene was confirmed by PCR using primers listed in Table S2.

Overexpression of znuC1B1.

To construct a znuC1-znuB1 (znuC1B1) overexpression strain, the coding region and the ribosome binding site of the znuC1 gene were amplified by PCR using primers znuCBFW_IP-znuCBRV_IP. The PCR product was cloned into the KpnI site of the isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG)-inducible vector pCRB12iP, which carries the LacI repressor gene lacIq and the tac promoter (33), yielding pCRC628. Overexpression of znuC1B1 in strains carrying pCRC628 was induced by supplementation of 0.5 mM IPTG.

RNA extraction and qRT-PCR.

Total RNA was extracted from C. glutamicum cells using a Qiagen RNeasy minikit (Qiagen) as described previously (34). Quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed using an Applied Biosystems 7500 Fast real-time PCR system (Life Technologies, CA) and Power SYBR green PCR master mix with murine leukemia virus (MuLV) reverse transcriptase and the RNase inhibitor of a GeneAmp RNA PCR kit (Life Technologies) as described previously (34). Ratios were normalized to the value for the 16S rRNA. The comparative threshold cycle method (Life Technologies) was used to quantify relative expression.

ChIP.

C. glutamicum cultures at the late exponential phase and the onset of the stationary phase (at optical densities at 610 nm [OD610s] of up to 2.5 and 7.0, respectively) were fixed with formaldehyde. ChIP was performed basically as described previously (32), except that the monoclonal anti-FLAG tag antibody (Sigma), instead of anti-Strep-Tag II antibody, was used. Cross-links of immunoprecipitated samples and of total DNA samples were reversed by incubation at 65°C overnight. Samples were then treated with RNase A and proteinase K. DNA was extracted with phenol-chloroform and purified with a MinElute PCR purification kit (Qiagen).

Microarray analyses.

We used an Agilent eArray platform (Agilent Technologies, Palo Alto, CA) to design a C. glutamicum oligonucleotide microarray. Two sets of probes were designed. One was used for global gene expression analysis, and the other was for ChIP-chip analysis. For global gene expression analysis, a set of 60-mer oligonucleotide probes specific for all of the open reading frames (ORFs) on both chromosome and a plasmid pCGR1 were designed and synthesized in duplicate (total, 6,742 probes). For ChIP-chip analysis, a set of 60-mer oligonucleotide probes covering the entire chromosome, on average, every 170 bases was designed (18,462 and 18,449 probes on plus and minus strands, respectively). The regions for RNA genes including rRNA and tRNA were excluded to avoid biased signals because these regions repeatedly contain similar sequences. In addition, the region highly transcribed often causes false positives in the ChIP-chip analysis (35). Each array contained both probe sets.

For transcriptome analysis, the cDNAs were reverse transcribed from 10 μg of total RNAs and labeled with Cy3 using a SuperScript indirect cDNA labeling system (Life Technologies). The labeled cDNA (1.7 μg) was mixed with Gene Expression Blocking Agent and Hi-RPM hybridization buffer, both of which were provided in a Gene Expression hybridization kit (Agilent), and hybridized to microarrays in an Agilent Technologies microarray chamber at 65°C for 17 h in a rotating Agilent hybridization oven. After hybridization, microarrays were washed with GE wash buffer 1 (Agilent) at room temperature for 1 min and with GE wash buffer 2 (Agilent) at 37°C for 1 min. Immediately after slides were washed, they were scanned on an Agilent DNA microarray scanner (G2505C) at a resolution of 5 μm using a single-color scan setting for slides with a 4 by 44,000 array (four arrays and 44,000 probes per slide). The photomultiplier tube (PMT) was set to 100% for Cy3 channels. The scanned images were quantified with Feature Extraction software, version 10.5.5.1 (Agilent), using default parameters (protocol GE1_105_Dec08). Feature-extracted data were analyzed using GeneSpring GX, version 12.0, software from Agilent. Normalization of the data was done in GeneSpring GX using the recommended percentile shift normalization (50th percentile).

For ChIP-chip analysis, DNA samples were blunted with T4 DNA polymerase, ligated to linkers, and amplified by PCR as described previously (32). Amplified DNA from reference DNA and immunoprecipitated DNA were differentially labeled with Cy3 and Cy5, respectively, by using a comparative genomic hybridization (CGH) labeling kit (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Equal amounts (2.5 μg) of each labeled DNA were mixed with Agilent blocking agent and Agilent hybridization buffer, both of which were provided in an Agilent Oligo aCGH kit/ChIP-on-chip hybridization kit. The mixture was heated at 95˚C for 3 min, immediately transferred to heat block at 37°C, and incubated for 30 min. After centrifugation at 17,900 × g for 1 min, the hybridization mixture was hybridized to microarrays in an Agilent Technologies microarray chamber at 65°C for 24 h in a rotating Agilent hybridization oven at 20 rpm. After hybridization, microarrays were washed with Oligo aCGH/ChIP-on-chip wash buffer 1 (Agilent) at room temperature for 5 min, with Oligo aCGH/ChIP-on-chip wash buffer 2 (Agilent Technologies) at 31°C for 5 min, with acetonitrile for 10 s, and with stabilization and drying solution (Agilent) for 30 s at room temperature. Slides were scanned immediately after being washed and placed within an Agilent ozone barrier slide cover with an Agilent DNA microarray scanner (G2505C) at a resolution of 5 μm using a two-color scan setting for 4- by 44,000-array slides. Scanning was done in both channels, and the PMT was set to 100% for the Cy3 and Cy5 channels. The scanned images were quantified with Feature Extraction software, version 10.5.5.1 (Agilent), using default parameters (protocol GE2_105_Dec08). Log2 ratios for each probe were determined as rProcessedSignal/gProcessedSignal (processed signal for the red channel/processed signal for the green channel; Cy5/Cy3). The entire procedure was carried out at three times, and the results were averaged. Creation of plots of the log2 ratios against probe location, extraction of ChIP-chip peaks, and determination of genomic locations for the peaks were performed using MochiView, version 1.45 (36). Peak extraction was performed using the following setting: for smoothing, smoothing window flank span of 500 bp; minimum weighted location count for inclusion, 1.01; maximum gap for data interpolation, 500 bp; for peak-finding setting, first-pass filter; peak location width, 350 bp; minimum value for peak inclusion, 0.35 and 0.45 for the exponential-phase and the stationary-phase cultures, respectively; second-pass filter scan distance, 600 bp; minimum peak height change, 0.8; minimum distance between peak midpoint, 100 bp; number of significance sampling, 0. ChIP-chip peaks not extracted were manually identified. The chromosomal sequences corresponding to the ChIP-chip peaks were extracted and analyzed using MEME (37) to define the σH-dependent promoter sequence. The ChIP-chip peak regions were manually searched for the conserved sequence motif obtained (GGAA-N18–20-GTT) to find additional and/or correct promoter sequences.

Determination of the intra- and extracellular concentrations of flavins.

Cells were grown in the minimal BT medium (BTM) (38) supplemented with 1% glucose at 33°C and harvested by centrifugation. Intracellular flavins were extracted as described previously (39). Briefly, the cells were lysed by suspending them with buffer containing 5.0 M guanidium thiocyanate, 0.1 M EDTA, and 0.5% sodium lauryl sarkosinate and incubating the samples at 70°C. The extracts and the culture supernatant were analyzed by a high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) system with a fluorescence detector (excitation, 470 nm; emission, 530 nm) (39).

5′ RACE.

For the identification of the transcriptional start points (TSPs), 5′ rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE) was carried out as described previously (33). Briefly, the total RNA extracted from the wild type after heat treatment was poly(A) tailed. cDNA was synthesized using a SMARTer RACE cDNA amplification kit (Clontech, CA) with the supplied oligo(dT)-anchored primer. The cDNA was amplified with universal primer A (supplied with kit) and gene-specific primers (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). The PCR products were cloned into a pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega). At least 10 clones of each 5′ RACE PCR product were sequenced.

Construction of promoter-lacZ fusions.

The promoter regions of the sigH, rshA, and sigA genes were amplified by PCR from C. glutamicum R chromosomal DNA using primers listed in Table S2 in the supplemental material. Mutations in the −10 region of the σA- and σH-dependent promoters of the sigA gene were introduced by overlapping PCR using primers listed in Table S2. The fragments amplified were phosphorylated and cloned upstream of the lacZ gene in pCRA741 (40). Direction and sequence of the inserted fragment were confirmed by DNA sequencing. The plasmids were isolated as nonmethylated DNA from E. coli JM110, introduced into C. glutamicum, and subsequently integrated into strain-specific island 7 (SSI7) on the chromosome of C. glutamicum R by markerless gene insertion methods, as described previously (3).

β-Galactosidase assay.

The cells permeabilized with toluene were incubated with o-nitrophenyl-β-galactoside, and their activities were measured in Miller units as previously described (41).

Microarray data accession number.

All genome-wide data have been deposited in NCBI's Gene Expression Omnibus under accession number GSE52078.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

rshA, located downstream of sigH, encodes an anti-σ factor of σH.

Previously, it was reported that the rshA gene located immediately downstream of the sigH gene encodes an anti-σ factor of σH in C. glutamicum ATCC 13032 (25). Although no such ORF has been annotated in the genome of C. glutamicum R (42), which was used as the wild-type strain in this study (see Table S1 in the supplemental material), reinspection of the genome revealed a small (267-bp) ORF (cgR_6064) encoding a protein with 100% amino acid sequence identity with the anti-σ factor RshA, as has been reported previously (25). As σH is constitutively active in the rshA mutant, expression of the σH regulon is upregulated in the absence of any stress (25). We confirmed that the expression level of mtr (cgR_1832), one of the components of the σH regulon in C. glutamicum R (14), was upregulated more than 10-fold by deletion of the rshA gene during normal growth (data not shown). Then, the gene expression profile of the wild type during the exponential phase was compared with that of the rshA deletion mutant using DNA microarrays (see Tables S3 to S5 in the supplemental material). In total, 74 genes were found upregulated 2-fold or more in the rshA deletion mutant compared to the level of the wild type. Among them, 34 genes have been previously shown to be upregulated by overexpression of σH or deletion of rshA under normal growth conditions (14, 25). These results not only confirmed that RshA is the anti-σH but also showed that there are σH regulon genes yet to be identified.

Identification of the σH-dependent promoters at a genome-wide level by ChIP-chip analysis.

Expression of the genes upregulated in the rshA mutant was not necessarily directed by the σH-dependent promoter. Furthermore, expression of genes under the control of the σH-dependent promoter was not necessarily upregulated in the rshA mutant as it is possible that an additional promoter(s) and/or an additional transcription factor(s) plays a pivotal role in expression of the genes. Hence, we performed ChIP-chip analysis using the rshA mutant, in which the σH expressed is potentially fully active to bind to its target promoters, to identify direct target genes of σH. For the analysis, we constructed a strain expressing σH with an N-terminal FLAG tag in the background of the wild type and the rshA mutant. Growth of the resulting strains was comparable to that of their parental strains. The heat shock response of the σH regulon in the wild type carrying FLAG-σH was comparable to that in the wild type (data not shown) although expression of sigH was upregulated 2-fold via unknown mechanisms by the introduction of the FLAG tag. Thus, the FLAG-tagged σH was confirmed to be functionally equivalent to the native σH. A Western analysis using anti-FLAG tag antibody demonstrated that a protein with the expected molecular mass of 24.3 kDa was expressed in the σH-FLAG strains (data not shown).

The rshA deletion mutant cells expressing the FLAG-tagged σH in the late exponential phase and the onset of the stationary phase were used for ChIP-chip analysis. We identified 88 genomic regions corresponding to the ChIP-chip peaks under both conditions (see Table S6 in the supplemental material). Of these regions, 71 were located upstream of annotated genes. The height of the ChIP-chip peaks obtained using the cells at the stationary phase tended to be greater than that obtained using cells in the late exponential phase (data not shown). Six peaks were additionally detected from the stationary-phase samples (see Table S6), with four of them located upstream of the annotated genes. Thus, in total, 75 ChIP-chip peaks were identified upstream of the genes. The other peaks were located in an intragenic region. As expected, our ChIP-chip analysis detected almost all of the known σH-dependent promoters, e.g., those for clpB and dnaK, encoding molecular chaperones (14, 27) (see Table S6). No peak was found upstream of groES-groEL1 and groEL2 for other molecular chaperones known to be indirectly affected by overexpression of σH (14). These findings confirmed the specificity of the ChIP-chip analysis. However, interactions of σH-RNAP with a few known σH-dependent promoters for dnaJ2, clpP1, and clpC, encoding a molecular chaperone and proteases, were not detected although expression of these genes was upregulated in the rshA mutant. Thus, affinity of σH-RNAP to these promoters may be unexpectedly low.

The 350-bp regions around the ChIP-chip peaks found upstream of coding regions were analyzed with MEME (37) to find a conserved motif. The motif obtained (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material) was consistent with the consensus promoter sequence (GGAA-N18–20-GTT) (see Table S6 in the supplemental material) which is recognized by σH orthologs in C. glutamicum (14), M. tuberculosis (43), and S. coelicolor (19). This analysis newly identified σH-dependent promoters upstream of 38 genes (see Table S6). Considering putative operon structures, 74 genes were newly included in the σH regulon. Some of these genes (11 genes) were found upregulated 2-fold or more in the rshA mutant compared to the wild type (see Tables S3 and S6). A manual search for the consensus promoter sequence in the other ChIP-chip peaks in the intragenic region identified possible promoter sequences (see Table S6). Most of the promoters were found on the antisense strand although their physiological roles are unknown. The promoter sequences newly identified by our ChIP-chip analysis (“novel” in the column labeled “σH regulon” in Table S6 in the supplemental material) were highly conserved in the orthologous regions in the genome of the type strain ATCC 13032 (44), suggesting their functional significance.

σH upregulates genes encoding Fe-S cluster-containing enzymes.

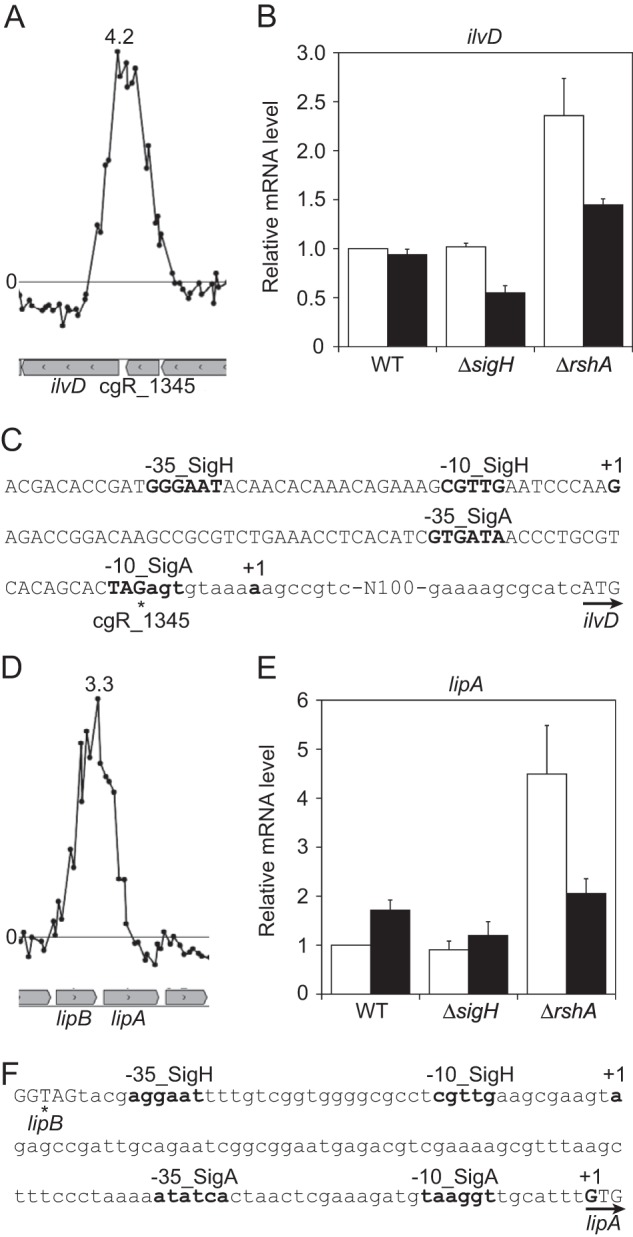

Of the σH regulon genes identified by ChIP-chip, ilvD (cgR_1344) and lipA (cgR_2089) encode Fe-S cluster-containing enzymes, namely, dihydroxyl-acid dehydratase and lipoic acid synthase, respectively. The consensus promoter sequence was found in the regions corresponding to the ChIP-chip peaks upstream of these genes (Fig. 1A, C, D, and F). Although upregulation of these genes in the rshA mutant has been previously observed, the putative σH-dependent promoter was predicted upstream of only lipA (25). By 5′ RACE analysis using RNA extracted from heat-treated cells, a transcriptional start point (TSP) of ilvD was determined to be guanine at 188 nucleotides (nt) upstream of the ilvD start codon and 10 nt downstream of the −10 region of the σH-dependent promoter identified in this study (Fig. 1C), confirming that the promoter identified was functional and induced by heat stress. The 5′ RACE analysis also revealed two TSPs for lipA: adenine at 94 nt upstream of the lipA start codon (GUG) and the first guanine of the start codon (Fig. 1F). The former is located 10 nt downstream of the −10 region of the σH-dependent promoter. The heat shock responses of these genes in the wild type, the sigH mutant, and the rshA mutant were compared by qRT-PCR analysis (Fig. 1B and E). Both ilvD and lipA genes were upregulated in the rshA mutant compared to the wild type before heat shock, indicating that these genes are upregulated by σH in the mutant. On the other hand, these transcripts were detected in the sigH mutant as well as in the wild type under the nonstress conditions, indicating that these genes can also be expressed in a σH-independent manner. In this context, a σA-dependent promoter of the ilvD gene has been reported previously (45), and a σA-dependent promoter-like sequence was found upstream of the TSP at the start codon of lipA in this study (Fig. 1C and F). It should be also noted that multiple ECF σ factors may be redundantly involved in recognition of the same promoter. The expression level of ilvD in the wild type was not enhanced by heat shock, while that in the sigH and rshA mutants was downregulated (Fig. 1B). Therefore, it is conceivable that the σH-independent promoter of ilvD is repressed by heat shock, and thereby the σH-dependent induction is counteracted in the wild type. Expression of lipA in the wild type was enhanced by heat shock, while the heat shock response was minimal in the sigH mutant (Fig. 1E). This indicates that lipA is upregulated in response to heat shock in a σH-dependent manner although unknown mechanisms seem to be involved in the heat-responsive downregulation observed in the rshA mutant.

FIG 1.

σH upregulates genes encoding Fe-S cluster-containing enzymes. (A and D) The ChIP-chip peaks found upstream of ilvD and of lipA. The log2 ratio of the Cy5 signal (ChIP-enriched DNA) divided by Cy3 signal (total genomic DNA) of each probe is plotted against the chromosomal location of the probes (x axis). Genes are indicated in the boxed arrows below the graphs. The image was created using MochiView, version 1.45 (36). Representative data are shown. The highest enrichment ratio (Cy5/Cy3) is indicated in each plot. (B and E) qRT-PCR analysis of transcript levels of ilvD and of lipA and lipB in the wild type (WT) and the sigH and rshA mutants grown in nutrient-rich A medium before (white) and after (black) heat shock treatment at 45°C for 15 min. The transcript levels before heat shock in the wild type were taken as 1. Mean values obtained from at least three independent cultivations are shown with standard deviations. (C and F) Nucleic acid sequences of the upstream regions of ilvD and of lipA. The transcriptional start points (TSPs) (+1) and the −35 and −10 regions of the σA- and σH-dependent promoters are indicated in boldface. The TSP from the σA-dependent promoter of ilvD has been previously determined (45). The terminal and start codons of cgR_1345 and ilvD (C) and those of lipB and lipA (F) are indicated with asterisks and arrows, respectively.

Dihydroxy-acid dehydratase encoded by ilvD catalyzes a step of the biosynthetic pathway for branched-chain amino acids. This enzyme is a stress-labile enzyme due to its Fe-S cluster (46, 47). E. coli exposed to hyperbaric oxygen or nitric oxide becomes auxotrophic for branched-chain amino acids due to inactivation of IlvD (48–50). However, involvement of any ECF σ factors in ilvD expression has never been reported in bacteria to our knowledge.

LipA catalyzes sulfur insertion into an octanoyl moiety that is ligated to an apoprotein by lipoate-protein ligase LipB (51, 52). Lipoic acid acts as a cofactor of pyruvate dehydrogenase, 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase, and H protein of the glycine cleavage system (51, 53). Like IlvD, LipA is also known to be an unstable enzyme, particularly under aerobic conditions where the Fe-S center of the protein becomes oxidized (54, 55).

C. glutamicum σH-dependent upregulation of ilvD and lipA is likely to replenish the unstable enzymes carrying the Fe-S cluster and an unstable cofactor lipoic acid under stress conditions. In this context, it should be noted that the suf operon encoding proteins involved in Fe-S cluster biosynthesis is also included in the σH regulon (14). Induction of genes for biosynthesis of stress-sensitive cofactors, including the Fe-S cluster, lipoic acid, coenzyme A (CoA), and NAD, and of those for enzymes carrying the cofactors by alternative sigma factors have been known (30, 56). C. glutamicum σH regulon also includes genes for synthesis of some of these cofactors and those for the enzymes (see Table S6 in the supplemental material). Thus, it is conceivable that the σ factors involved in heat and/or oxidative stress response in diverse bacteria appear to have a similar role in replenishment of the labile molecules.

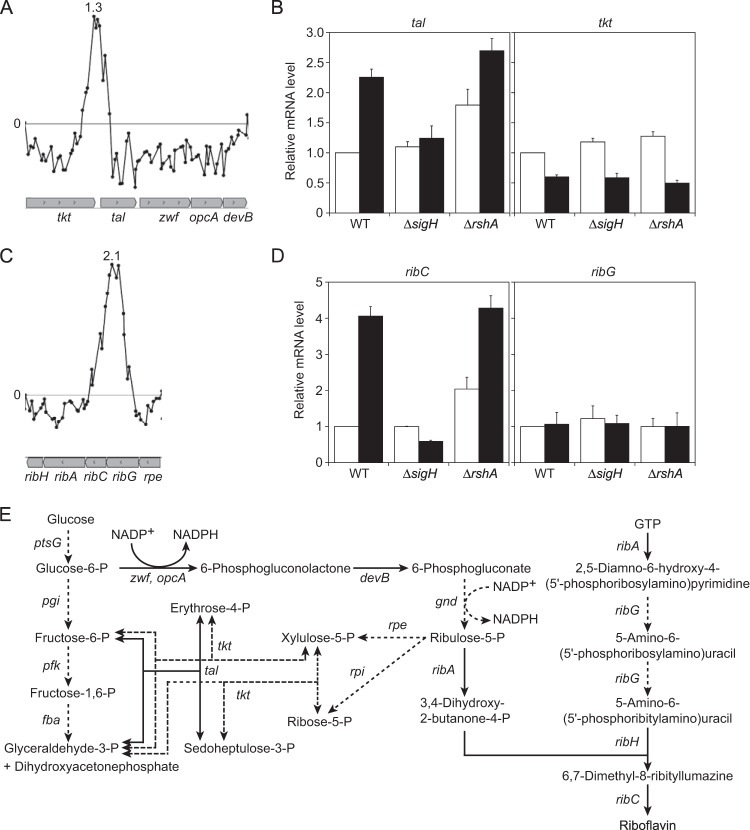

σH upregulates PPP genes.

The gene cluster tkt-tal-zwf-opcA-devB encodes the following enzymes involved in the pentose phosphate pathway (PPP) (Fig. 2A and E): transketolase, transaldorase, glucose-6-phosphate 1-dehydrogenase, putative subunit of glucose-6-phosphate 1-dehydrogenase, and 6-phosphogluconolactonase. The expression of these genes is repressed by binding of GntR1 to the tkt promoter region (57). The binding of GntR1 is inhibited, and all of the genes in this cluster are upregulated in the presence of gluconate (57), which is phosphorylated to 6-phosphogluconate and entered into the PPP. Despite the deduced operon structure, the ChIP-chip peak and the consensus promoter sequence for σH were found upstream of the tal gene (Fig. 2A; see also Table S6 in the supplemental material). The microarray analysis showed that expression of tal-zwf-opcA-devB but not tkt was slightly but significantly upregulated in the rshA mutant compared to the level in the wild type under normal growth conditions (see Table S3). Comparison of the heat shock responses of tal among the wild type and sigH and rshA mutants demonstrated that heat induction of tal is dependent on σH (Fig. 2B). On the other hand, the expression level of tkt was somewhat downregulated in response to heat shock in a σH-independent manner (Fig. 2B). Differential expression of tal was not observed in the previous study of a C. glutamicum rshA mutant, but expression of its downstream genes (zwf-opcA-devB) was upregulated more than 1.5-fold in the mutant (25). This led the authors to wrongly predict the σH-dependent promoter upstream of zwf (25). The existence of the internal promoter upstream of tal was further supported by the finding that a TSP specifically determined at 83 nt upstream of the tal start codon by 5′ RACE using RNA extracted from heat-treated cells was mapped at 10 nt downstream of the −10 region of the internal promoter. These results demonstrate that the upregulation of tal-zwf-opcA-devB in the rshA mutant is attributable to the σH-dependent internal promoter located upstream of tal in the tkt-tal-zwf-opcA-devB operon under the GntR1-mediated control of the tkt promoter. Therefore, the cluster of PPP genes is regulated by the two promoters in response to carbon source and heat/oxidative stress.

FIG 2.

σH upregulates genes involved in the PPP and riboflavin biosynthesis. (A and C) The ChIP-chip peaks found within the tkt-tal-zwf-opcA-devB cluster and the ribGCAH genes. The description of the panels is the same as in the legend to Fig. 1A and D. (B and D) qRT-PCR analysis of transcript levels of tal and tkt and of ribC and ribG in the wild type and the sigH and rshA mutants before (white) and after (black) heat shock treatment as described in the legend to Fig. 1B and E. The transcript levels before heat shock in the wild type were taken as 1. Mean values obtained from at least three independent cultivations are shown with standard deviations. (E) The metabolic pathway from glucose to riboflavin via the PPP is depicted. The genes upregulated in the rshA mutant compared to the wild type are indicated by italic bold letters. The reactions catalyzed by enzymes which are upregulated and unchanged in the rshA mutant are indicated by solid and dashed arrows, respectively.

The σH-dependent upregulation of the PPP genes in C. glutamicum is likely to be required to provide NADPH for the thioredoxin/thioredoxin reductase system under the control of σH. It should also be noted that the PPP provides a substrate (ribulose-5-phosphate) for biosynthesis of flavins, as described later. S. coelicolor possesses the same PPP gene cluster as that in C. glutamicum, and the recent ChIP-chip analysis has indicated the presence of a σR-dependent promoter upstream of the transaldolase gene and suggested the role of σR in NADPH generation (30). Proteome analysis of stress-induced proteins has identified the corresponding transaldolase (58).

σH enhances riboflavin biosynthesis.

The ribGCAH gene cluster encodes the following enzymes involved in riboflavin biosynthesis from ribulose-5-phosphate and GTP (Fig. 2E): bifunctional riboflavin-specific deaminase/reductase (RibG), the α-chain of riboflavin synthase (RibC), bifunctional GTP cyclohyrolase II/3,4-dihydroxy-2-butanone-4-phosphate synthase (RibA), and the β-chain of riboflavin synthase (RibH). Although there is no intergenic region between ribG and ribC, a ChIP-chip peak was found upstream of the ribC gene (the intragenic region of the ribG gene) (Fig. 2C). Expression of ribCAH in the cluster was upregulated in the rshA mutant compared to the level in the wild type (see Tables S3 and S6 in the supplemental material). These results indicate that the ribCAH genes are cotranscribed from the σH-dependent internal promoter within the ribGCAH operon. Although the upregulation of the ribCAH genes in the rshA mutant has been previously observed (25), no promoter sequence has been assigned upstream of the ribC gene. The 5′ RACE analysis using RNA extracted from heat-treated cells determined a TSP of ribC to be adenine at 235 nt upstream of the start codon of ribC. The TSP was close to the ChIP-chip peak identified. The σH-dependent promoter-like sequence, with one mismatch in the −10 region element, was identified upstream of the TSP (see Table S6). Furthermore, ribC exhibited σH-dependent heat induction while ribG did not (Fig. 2D). These findings confirmed that the ribCAH genes are under the control of σH. In contrast to expression of ilvD and lipA (Fig. 1B and D), expression of tal and ribC in the rshA mutant was further upregulated by heat shock (Fig. 2B and D). Their expression levels in the rshA mutant after heat shock were comparable to those in the wild type. Thus, additional, different factors may be coordinated with the σH-dependent heat shock response of various genes.

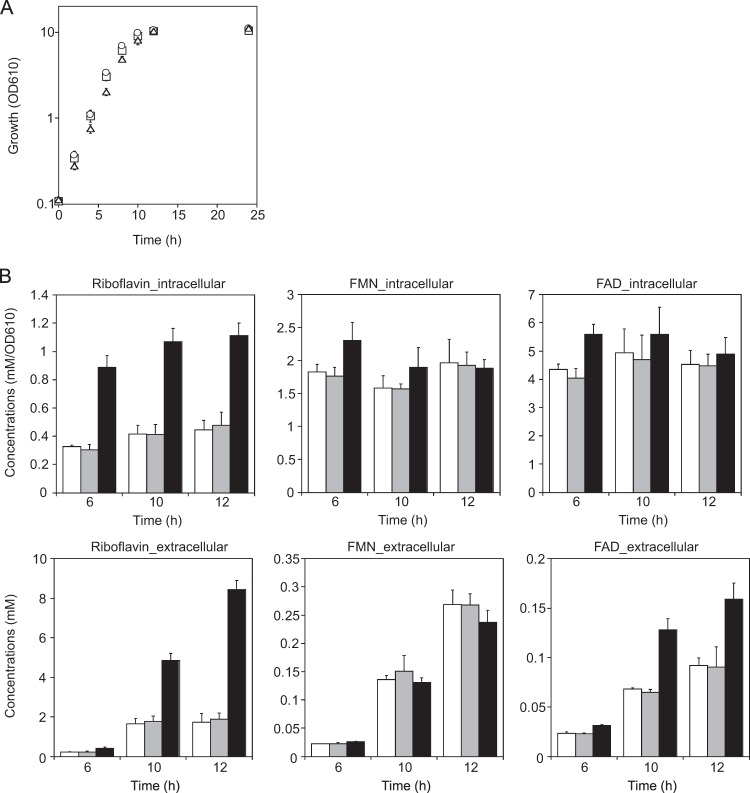

Upon induction of the σH regulon in response to heat and oxidative stress, demand for flavin cofactors and NADPH increases as a consequence of the induction of flavin-dependent oxidoreductases and the thioredoxin/thioredoxin reductase system (14). In this context, it is interesting that the genes involved in the PPP (tal-zwf-opcA-devB) as described above and riboflavin synthesis (ribCAH) are coordinately regulated by σH (Fig. 2B, D, and E). We observed that the stationary-phase culture of the rshA mutant became a much brighter yellow than that of the wild type (data not shown), suggesting that the upregulation of the σH regulon results in overproduction of flavin compounds. Then, intracellular and secreted extracellular concentrations of riboflavin and flavin nucleotides (flavin mononucleotide [FMN] and flavin adenine dinucleotide [FAD]) of the wild type and the sigH and rshA mutants during growth in minimal medium (BTM) containing 1% glucose were determined (Fig. 3). The growth of the rshA mutant under these conditions was slightly slower than that of the other two strains (Fig. 3A). The cultures were sampled at the exponential (6 h) and stationary (10 h for the wild type and the sigH mutant; 12 h for the rshA mutant) phases. The intracellular levels of the flavins in the wild type were almost unchanged during the period of cultivation (Fig. 3B, upper panels, white bars), while the extracellular ones increased in the stationary phase (Fig. 3B, bottom panels, white bars). In the sigH mutant, the levels of intra- and extracellular flavins were comparable to those of the wild type throughout the cultivation period (Fig. 3B, white and gray bars), indicating that σH is not necessary for biosynthesis of the flavins at the wild-type levels under normal growth conditions. As expected, in the rshA mutant the intra- and extracellular levels of riboflavin were 2.5-fold higher than those in the wild type (Fig. 3B, left panels, white and black bars). On the other hand, the intra- and extracellular levels of FMN and FAD were comparable among the three strains, except that the extracellular FAD level of the rshA mutant was 2-fold higher than that of the wild type at the stationary phase. As observed for the other two strains, the intracellular levels of the flavins of the rshA mutant were almost constant, and the extracellular ones increased with growth (Fig. 3B). The intracellular levels of FMN and FAD of all the strains were much higher than those of riboflavin (Fig. 3B, upper panels), whereas the extracellular levels of the flavin nucleotides were less than 10% of those of riboflavin (Fig. 3B, bottom panels). Taken together, these findings indicate that riboflavin biosynthesis is enhanced by activation of σH but that intracellular levels of the flavin nucleotides are strictly maintained. It is likely that excess intracellular riboflavin is actively excreted although no riboflavin exporter has been reported in bacteria (59). Because it is known that riboflavin generates superoxide during auto-oxidation (60), the intracellular riboflavin level should be kept low.

FIG 3.

Riboflavin biosynthesis is enhanced in the rshA mutant. (A) Growth of the wild type (squares) and the sigH (circles) and rshA (triangles) mutants in BTM supplemented with 1% glucose. Mean values obtained from three independent cultivations are shown with standard deviations. (B) Intracellular and extracellular (levels of riboflavin, FMN, and FAD of the wild type (white) and the sigH (gray) and rshA (black) mutants during growth in BTM supplemented with 1% glucose. Mean values obtained from at least three independent cultivations are shown with standard deviations.

In bacteria, genes involved in biosynthesis and transport of riboflavin are generally under the control of feedback regulation mediated by the conserved FMN-sensing RFN riboswitch element, which consists of the 5′ untranslated region of the transcript (61, 62). Binding of FMN to the element causes premature transcription termination and precludes access to the ribosome-binding site. However, as shown for the ribGCAH operon in C. glutamicum, riboflavin biosynthetic genes have also been shown to be regulated by environmental stress (21, 63), and some are regulated via internal promoters found in the operons (56, 64). Thus, bacterial riboflavin biosynthesis is controlled in a flavin-dependent and -independent manner.

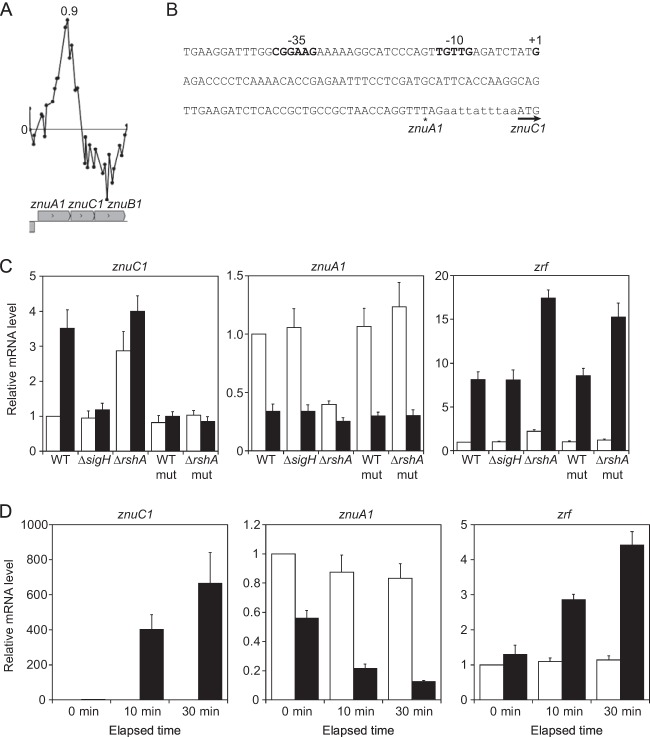

σH upregulates a Zn uptake transporter.

The ChIP-chip analysis newly identified the σH consensus promoter sequence in the upstream region of znuC1 (Fig. 4A and B). znuC1 is the second gene in the znuA1C1B1 operon (cgR_2535-cgR_2536-cgR_2537) encoding the ABC-type transporter ZnuA1B1C1 for Zn uptake. ZnuA1, ZnuB1, and ZnuC1 are Zn-binding protein, permease, and ATPase component, respectively. The microarray analysis showed that expression of znuC1 and znuB1 was upregulated in the rshA mutant compared to the wild type, but znuA1 was downregulated in the mutant (see Tables S3 and S5 in the supplemental material). This indicates that components of the ZnuA1B1C1 transporter are distinctly regulated by at least two promoters located upstream of znuA1 and znuC1. Actually, the 5′ RACE analysis revealed a TSP at 94 nt upstream of the start codon of znuC1 in the coding region of znuA1. The position is 10 nt downstream of the −10 region of the σH-dependent promoter identified (Fig. 4B). Moreover, znuC1 exhibited σH-dependent heat induction while znuA1 did not (Fig. 4C).

FIG 4.

σH upregulates a Zn uptake transporter. (A) The ChIP-chip peak found within the znuA1C1B1 genes. The description of the panels is the same as in the legend to Fig. 1A and D. (B) Nucleic acid sequence of the upstream region of the znuC1 gene. The TSP (+1) and the −35 and −10 regions of the znuC1 promoter are indicated in boldface. The terminal and start codons of the znuA1 and znuC1 genes, respectively, are indicated with an asterisk and an arrow. (C) qRT-PCR analysis of transcript levels of znuC1, znuA1, and zrf in the wild type and the sigH and rshA mutants and in the wild type and the rshA mutant carrying the mutated PznuC1 (mut) before (white) and after (black) heat shock treatment as described in the legend to Fig. 1B and E. The transcript levels before heat shock in the wild type were taken as 1. Mean values obtained from at least three independent cultivations are shown with standard deviations. (D) Effects of overexpression of znuC1B1 on expression of the Zur regulon. Changes in transcript levels of znuC1, znuA1, and zrf in the control strain (white) and a znuC1B1-overexpressing strain (black) after IPTG supplementation were analyzed using qRT-PCR. The mRNA levels are presented relative to the value obtained from the control strain before IPTG supplementation (0 min). Mean values obtained from at least three independent cultivations are shown with standard deviations.

The promoter activity of znuA1 is repressed by binding of Zn-bound Zur, which belongs to the ferric uptake repressor (Fur) family, under Zn-replete conditions (65). When Zn is depleted, Zn-free Zur is released from the promoter, and expression of the znuA1C1B1 operon is derepressed. In addition to znuA1C1B1, genes encoding another ABC-type transporter for Zn uptake, ZnuA2B2C2 (cgR_0042-cgR_0041 and cgR_0043), a P-loop GTPase (cgR_0812), and an oxidoreductase (cgR_0813) are included in the Zur regulon and upregulated in response to Zn deficiency (65). Furthermore, recently, we demonstrated that zra (cgR_0148) and zrf (cgR_1359), which encode a metal-translocating P-type ATPase and a cation diffusion facilitator, respectively, are also under the control of Zur (66). It should be noted, however, that these novel regulon genes encode Zn exporters and are repressed by Zn-free Zur and derepressed under excess Zn conditions (66). Thus, C. glutamicum Zur acts as a Zn-sensing transcriptional repressor of both Zn-inducible and Zn-repressible genes involved in Zn homeostasis in distinct ways. Since the Zn uptake system genes znuC1B1 were found to be upregulated by σH as described above, we focused on the effects of rshA deletion on the Zn-responsive genes under the control of Zur. The microarray analysis revealed no difference in expression of the Zn-repressible genes between the rshA mutant and the wild type (see Table S7 in the supplemental material), except for that of the znuA1 gene downregulated in the rshA mutant as described above. On the other hand, zrf, one of the two Zn-inducible genes, was upregulated 2.7-fold in the rshA mutant, but expression of another gene, zra, was not affected by rshA deletion (see Table S7). As no ChIP-chip peak was found upstream of the Zur regulon genes except for znuC1 (data not shown), the effects of rshA deletion on expression of the Zn-responsive genes, znuA1 and zrf, are probably indirect through physiological changes caused by the upregulation of the SigH regulon including the Zn uptake system genes znuC1B1.

This was examined by a mutational analysis of the σH-dependent promoter of znuC1 (PznuC1) in the coding region of znuA1. A point mutation (GTT to GTG), which has no effect on the amino acid sequence of ZnuA1, was introduced into the −10 region of PznuC1 (Fig. 4B) in the genome of the wild type and the rshA mutant. As expected, the upregulation of znuC1 in the wild type after heat shock was abolished by the mutation in the PznuC1 promoter (Fig. 4C), confirming that the mutation inactivated PznuC1. Expression of znuC1, znuA1, and zrf in the rshA mutant carrying the mutated PznuC1 was comparable to that in the wild type under nonstress conditions (Fig. 4C, white bars). These findings demonstrate that the downregulation of znuA1 and upregulation of zrf in the rshA mutant in the absence of stress are attributed to the upregulation of znuC1B1 by PznuC1 under the control of σH.

To examine whether an increase in the expression of znuC1B1 affects the Zur-mediated regulation in the wild-type background, we constructed a znuC1B1-overexpressing strain and compared expression of the Zur regulon in the strain to that in the control strain carrying a vector only. Plasmid pCRC628 carrying znuC1B1 under the control of both the tac promoter and LacI repressor was introduced into the wild type. The culture of the plasmid-carrying strains was supplemented with IPTG at the exponential phase. Expression of znuC1 increased over 400-fold 10 min after of the supplementation, while that in the control strain was not changed (Fig. 4D). Under these conditions, znuA1 was downregulated with the increase in the expression levels of znuC1B1 (Fig. 4D), whereas expression of the other Zur-mediated Zn-repressible genes was not affected (data not shown). In contrast, expression of a Zur-mediated Zn-inducible gene, zrf, but not another gene, zra (data not shown), was upregulated with the increase in znuC1B1 expression (Fig. 4D). The differential effects of overexpression of znuC1B1 on the Zur regulon were consistent with those of rshA deletion. These findings indicate that the upregulation of znuC1B1, not the entire znuA1C1B1 operon, from the internal σH-dependent promoter results in changes in the action of Zur, probably through potentiation of Zn uptake.

While the downregulation of the first gene, znuA1, of the znuA1C1B1 operon in the rshA mutant under normal growth conditions was abolished by the mutation in PznuC1, the downregulation of znuA1 after heat shock in the wild type was not affected by either deletion of the sigH gene or the mutation introduced into the PznuC1 promoter (Fig. 4C, black bars). zrf was upregulated by heat shock in the wild type (Fig. 4C), as has been previously observed (14). This upregulation was also not affected by either deletion of the sigH gene or the mutation introduced into PznuC1 (Fig. 4C) although it was enhanced through unknown mechanisms by deletion of the rshA gene. These findings indicate that the changes in the expression of a part of the Zur regulon caused by heat shock are independent of σH action on znuC1B1 expression.

The Bacillus subtilis Zn uptake system, ZosA, a P-type metal-transporting ATPase, is upregulated in response to oxidative stress caused by H2O2 and diamide (67). An increase in the intracellular Zn levels by the upregulation of ZosA may protect thiols from oxidation by replacing highly reactive metals, e.g., iron and copper, with the less reactive Zn (67). This may also prevent the propagation of free radical chain reactions. Interestingly, B. subtilis zosA is regulated by the peroxide-responsive transcriptional regulator PerR (67) but not by Zur, which regulates other Zn uptake systems in response to Zn availability (68). In contrast, in C. glutamicum, Zur and σH control a Zn-uptake ABC-type transporter in response to Zn availability and heat/oxidative stress, respectively, suggesting that the transporter ZnuA1B1C1 plays an important role in control of Zn homeostasis to adapt to various stress conditions. Our disc diffusion assays showed that the mutation in PznuC1 had no effect on sensitivity of the wild type to oxidative stress caused by diamide, menadione, and plumbagin under high- and low-Zn conditions (data not shown), whereas the sigH mutant showed enhanced sensitivity to the stress. Hence, a further study is required for understanding of a physiological role of the σH-mediated enhancement of the Zn uptake system in the stress response of C. glutamicum.

rshA is transcribed from the internal promoter driven by σH, located in the sigH-rshA operon.

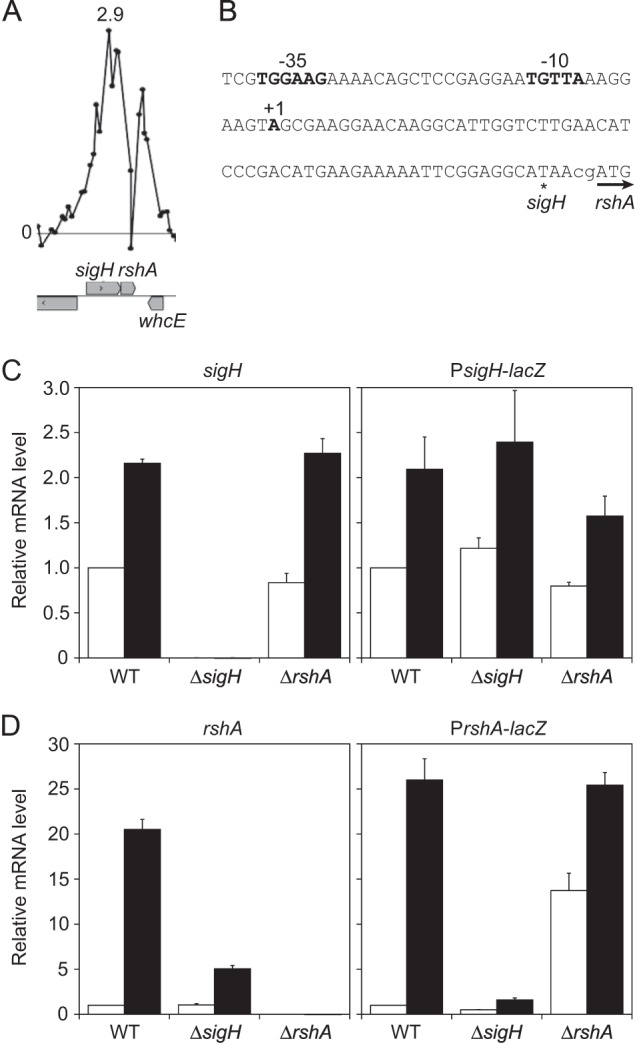

A recent study using Northern and primer extension analyses demonstrated that sigH and rshA constitute an operon under the σA-dependent promoter and that rshA is separately transcribed from the putative σH-dependent promoter upstream of rshA (25). Consistent with the results, our ChIP-chip analysis revealed that σH binds to the intragenic region, but not the upstream region, of its own gene (Fig. 5A). The same σH consensus promoter as reported was found in the corresponding ChIP-chip peak region (25) (Fig. 5A and B). By 5′ RACE using total RNA extracted from the wild-type cells subjected to heat shock, the TSP of the rshA gene was determined to be an adenine 63 bp upstream of the start codon, which is located at the expected distance from the σH-dependent promoter identified (Fig. 5B) and very close to the TSP reported in the previous study (25).

FIG 5.

The rshA gene is under the control of the σH-dependent promoter. (A) The ChIP-chip peak upstream of the rshA gene. Because the result was obtained from ChIP-chip using the rshA deletion mutant, the enrichment ratio of the probes corresponding to the region deleted was background level. The description of the panel is the same as in the legend to Fig. 1A and D. (B) Nucleic acid sequence of the upstream region of the rshA gene. The TSP (+1) and the −35 and −10 regions of the rshA promoter are indicated in boldface. The terminal and start codons of the sigH and rshA genes, respectively, are indicated with an asterisk and an arrow. The heat shock response of sigH (C) and rshA (D) in the wild type and the sigH and rshA mutants was determined by changes in transcript levels of the corresponding genes (left panels) and the lacZ gene (right panels) fused to the promoter region of the sigH and rshA) genes. Transcript levels before (white) and after (black) heat shock were compared using qRT-PCR. The transcript levels before the heat shock in the wild type were taken as 1. Mean values obtained from at least three independent cultivations are shown with standard deviations.

Although the sigH gene has been previously shown to be upregulated after heat shock (14), the heat shock response of the rshA gene has never been tested. Here, we determined changes in rshA expression in response to heat shock by qRT-PCR analysis. While expression of sigH in the wild type was upregulated about 2-fold after heat shock, that of rshA was upregulated more than 20-fold (Fig. 5C and D, left panels), indicating that expression of the two genes is independently regulated in response to heat shock. The degree of the heat-responsive upregulation of rshA expression in the sigH deletion mutant was markedly lower than that in the wild type, indicating that σH plays an important role in the heat induction of rshA. The 5-fold increase in the expression level of rshA upon heat shock in the sigH mutant, in which the rshA promoter was removed, may be due to the promoter located upstream of the sigH gene, which exhibited a σH-independent heat shock response (Fig. 5C) (see also below).

Furthermore, activity of these promoters in the sigH and rshA mutants was determined. The upstream regions of sigH and rshA, corresponding to positions −415 to +18 and −444 to +15, respectively, with respect to the start codon of the genes, were fused to the promoterless lacZ gene. The resulting fusions (PsigH-lacZ and PrshA-lacZ) were integrated into a strain-specific region in the chromosome of the wild type and the sigH and rshA mutants. Because β-galactosidase was found to be heat labile (data not shown), activities of the promoter-lacZ fusion in the strains were compared by measuring levels of the lacZ transcript using qRT-PCR (Fig. 5C and D, right panels). The heat-inducible changes in the levels of the lacZ transcript of the PsigH- and PrshA-lacZ fusions were comparable to those in the expression levels of sigH and rshA (Fig. 5C and D, compare right and left panels). Thus, the changes in the promoter activity determined by the transcript level of lacZ well reflect those in the expression levels of the corresponding genes. The PsigH activity in the wild type was comparable to levels in the sigH and rshA mutants irrespective of heat shock treatment (Fig. 5C), indicating that σH is not involved in the regulation of its own promoter activity. The expression levels of the PrshA-lacZ fusion in the sigH and rshA mutants were half and 13-fold that in the wild type, respectively, before heat shock (Fig. 5D, white bars), suggesting that PrshA is highly dependent on σH. PrshA activity in the wild type was upregulated more than 20-fold upon heat shock, as was the expression level of rshA (Fig. 5D). Meanwhile, the degree of the induction by heat shock was markedly decreased in the sigH mutant. PrshA-lacZ expression in the rshA mutant was upregulated 1.5-fold after heat shock, and it was comparable to that in the wild type. Based on these results, the σH-dependent promoter upstream of the rshA gene is involved in the heat-responsive induction. That PrshA activity in the sigH mutant was still detectable and heat inducible implies involvement of a σ factor other than σH in this induction.

In sharp contrast to the situation of C. glutamicum sigH, its orthologs in M. tuberculosis and S. coelicolor are subject to autoregulation. The sigR gene in S. coelicolor is under the control of two promoters: the primary σ factor HrdB-dependent promoter and the σR-dependent one (69). The σR-dependent promoter yields an isoform of σR with an N-terminal extension of 55 amino acids to σR constitutively expressed from the HrdB-dependent promoter. The isoform of σR is susceptible to proteases ClpP1/ClpP2, which are expressed from the σR-dependent promoter (69). Thus, σR is subject to positive feedback regulation at the transcriptional level and negative feedback regulation at the protein level. σH in mycobacteria is likely to be under the same regulation (15, 16, 30, 70). However, because of the absence of the alternative initiation codon, N-terminal extension of the C. glutamicum σH is unlikely. Four promoters, all of which are likely σA dependent, were recently found, and one of them is likely to be controlled by the SOS response regulator LexA (25, 71). LexA may be involved in the σH-independent increase of sigH transcript level in response to heat shock (Fig. 5C).

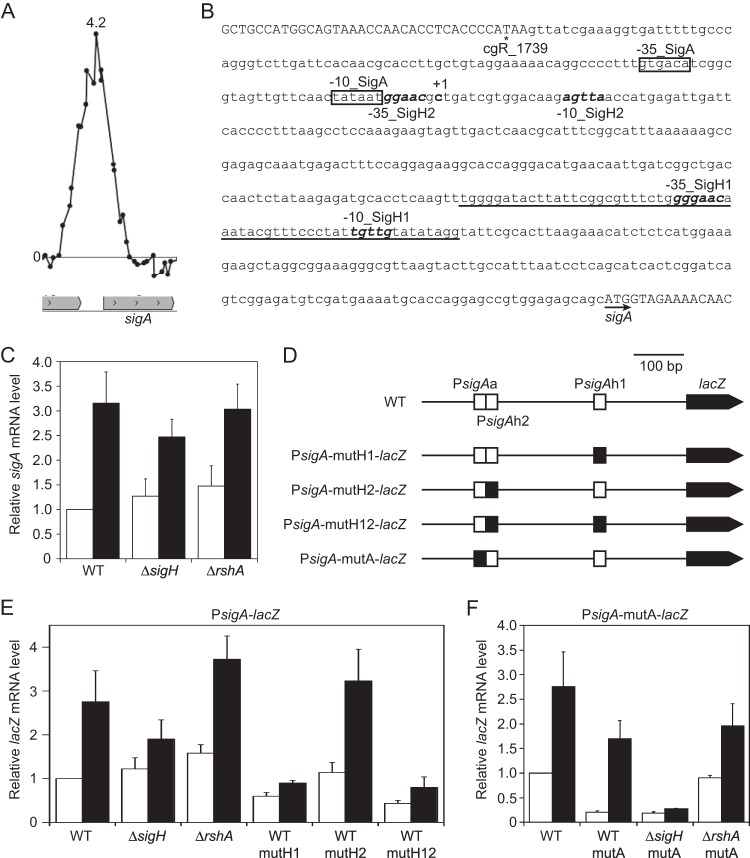

σH-mediated heat shock response of the housekeeping σ factor, σA.

A large ChIP-chip peak was found upstream of the sigA gene (Fig. 6A), which encodes the housekeeping σ factor σA, and two putative σH-dependent promoter sequences (PsigAh1 and PsigAh2) were identified in the corresponding region (Fig. 6B; see also Table S6 in the supplemental material). The −10 regions of these putative σH-dependent promoters are located 149 and 364 bp upstream of the start codon (Fig. 6B). It has been reported that sigA is transcribed from the σA-dependent promoter and that its TSP is located 380 bp upstream of the start codon (72) (Fig. 6B, +1 site). Hence, the newly identified σH-dependent promoters are located downstream of the known σA-dependent promoter. The heat shock response of sigA in the wild type and sigH and rshA mutants was monitored by qRT-PCR analysis. Expression of sigA in the wild type was upregulated 3-fold in response to heat shock (Fig. 6C). The effects of deletion of either sigH or rshA on sigA expression before and after heat shock were small, but the heat induction of sigA appeared to be partially dependent on σH (Fig. 6C).

FIG 6.

Characterization of the novel σH-dependent promoter in the upstream region of the sigA gene. (A) The ChIP-chip peak upstream of the sigA gene. The description of the panel is the same as in the legend to Fig. 1A and D. (B) Nucleic acid sequence of the upstream region of the sigA gene. The intergenic region between sigA and cgR_1739 is indicated in lowercase letters while the coding region of the genes is indicated in uppercase. The start and terminal codons of sigA and cgR_1739 are indicated with an arrow and an asterisk, respectively. The TSP of sigA is indicated with +1. The −10 and −35 regions of the known σA-dependent promoter are boxed. Those of the newly found σH-dependent promoters are indicated in bold and italic letters. The sequence of the microarray oligonucleotide probe with the highest enrichment ratio in the ChIP-chip peak in panel A is underlined. (C) Changes in transcript levels of sigA in the wild type and the sigH and rshA mutants after heat shock. (D) The PsigA-lacZ fusion constructs. The σA- and σH-dependent promoters (PsigAa, PsigAh1, and PsigAh2), with or without mutations in their −10 regions, are indicated with filled or open squares, respectively. (E) Changes in transcript levels of lacZ derived from the PsigA-lacZ fusions after heat shock in the wild type and the sigH and rshA mutants. Changes in the transcript levels of lacZ of the PsigA-lacZ fusions carrying mutations in the σH-dependent promoter region (mutH1, mutH2, and mutH12) are also indicated. (F) Changes in transcript levels of lacZ derived from the PsigA-lacZ fusion carrying mutations in the −10 region of the σA-dependent promoter (PsigA-mutA-lacZ) in the wild type and the sigH and rshA mutants after heat shock. In panels C, E, and F, transcript levels before (white) and after (black) the heat shock treatment as described in the legend to Fig. 1B and E were compared using qRT-PCR. The transcript levels before heat shock in the wild type were taken as 1. Mean values obtained from at least three independent cultivations are shown with standard deviations.

The sigA promoter activity in the wild type, the sigH mutant, and the rshA mutant background was monitored by determining the transcript level of lacZ fused to the upstream region of sigA (position +15 to −629 with respect to the start codon) (Fig. 6D). The expression of PsigA-lacZ in response to heat shock was largely consistent with that of sigA (Fig. 6C and E). To separately examine the heat shock response of an activity of the σH-dependent (PsigAh1 and PsigAh2) and the σA-dependent (PsigAa) sigA promoters, the most conserved sequence of the −10 region of each promoter was mutated to inactivate the promoters (Fig. 6D). The −10 regions of PsigAh1 and the PsigAh2 promoters, TGTTG and AGTTA, respectively, were mutated to TCAAT and ACAAA, respectively (designated mutH1 and mutH2 or, in combination, mutH12; the mutated nucleotides are shown in bold). The −10 region of PsigAa, TATAAT, was mutated to GCGAAT (designated mutA). First, effects of the mutations introduced in the PsigAh1 and PsigAh2 promoters on expression PsigA-lacZ in response to heat shock in the wild type were examined (Fig. 6D and E, mutH1, mutH2, and mutH12). Expression of the PsigA-lacZ fusion carrying mutated PsigAh1 (mutH1) in the wild type was downregulated compared to that of the native PsigA-lacZ promoter; however, the mutated promoter, similar to the native one in the sigH mutant, still showed a slight heat shock response (Fig. 6E). On the other hand, the mutations in PsigAh2, even in the combination with those in PsigAh1, had no effect on the expression of the PsigA-lacZ fusion (Fig. 6E, mutH2 and mutH12), suggesting that the PsigAh2 promoter is not functional under the conditions used in this study. Alternatively, it is possible that the PsigAh2 promoter is not a functional promoter but is the consequence of fortuitous concordance to the σH promoter sequence. In this context, the oligonucleotide probe with the highest enrichment value in the ChIP-chip peak corresponded to the PsigAh1 region (Fig. 6A and B). These results also suggest that the increase in the expression of sigA and PsigA-lacZ in the sigH mutant after heat shock is derived from changes in the σA-dependent sigA promoter (PsigAa).

Next, the heat shock response of the σH-dependent sigA promoter (PsigAh) was examined using a PsigA-lacZ fusion carrying the mutated σA-dependent promoter (Fig. 6D, PsigA-mutA-lacZ). Expression of lacZ of PsigA-mutA-lacZ in the wild type before heat shock was 5-fold lower than that of the native PsigA-lacZ fusion (Fig. 6F). Consistent with this, the β-galactosidase activity of the mutated PsigA-lacZ fusion in the wild type after overnight culture was 5-fold lower than that of the native one (data not shown). These findings indicate that the contribution of PsigAh1 to the total expression of sigA is much smaller than that of the PsigAa promoter. The expression level of PsigA-mutA-lacZ in the wild type before heat shock was comparable to that in the sigH mutant but 4-fold lower than that in the rshA mutant (Fig. 6F, white bars). After heat shock, PsigA-mutA-lacZ expression was upregulated almost 10-fold in the wild type, while the heat shock response of the PsigA-mutA-lacZ promoter was minimal in the sigH mutant (Fig. 6F). PsigA-mutA-lacZ expression in the rshA mutant increased 2-fold after heat shock to reach the wild-type level. These results indicate that the PsigAh1 promoter is a σH-dependent heat shock-responsive promoter. It is likely that the strong activity of PsigAa masks the PsigAh1-mediated heat induction of sigA in the wild type.

It is interesting that the primary σ factor, RpoD, in E. coli is also controlled by the heat-responsive σ factor RpoH (73, 74). In B. subtilis, the sigA gene, encoding the primary σ factor σA, is under the control of both σA and an alternative σ factor, σH, involved in sporulation (75–77). Furthermore, the recent ChIP-chip analysis of S. coelicolor σR revealed that σR directly upregulates hrdB encoding the primary σ factor in response to oxidative stress caused by diamide (30). σR-dependent transcription maintains HrdB expression levels under the stress conditions, where σR-independent transcription is inhibited (30). Thus, it is likely that in diverse bacteria, the σ factor activated in response to some stress signals is involved in upregulation of the primary σ factor gene. Taken together with the fact that sigB is included in the σH regulon in C. glutamicum, these findings suggest that the stress-responsive σ factor σH promotes transcription from not only its direct target promoters but also the primary(-like) σ factor-dependent promoters indirectly.

Conclusions.

Our transcriptome and ChIP-chip analysis using the rshA mutant revealed several new members of the C. glutamicum σH regulon. Particularly, the newly identified internal promoters, like those of tal, ribC, and znuC1, highlight the advantage of the ChIP-chip analysis. The σH-dependent regulation of these genes seems to be involved in cellular adaptation to stress by augmentation of biomolecules vulnerable to heat and oxidative stress and/or by preventing propagation of oxidative damage. Comparison of the regulon members of C. glutamicum σH with those of S. coelicolor σR confirms functional conservation of the σH orthologs among Actinomycetales, as has been predicted (30). However, on the other hand, the genes first identified as components of the σH regulon, including ilvD, ribCAH, and znuC1B1, indicate the diversity of the genes regulated by the orthologous σ factors. Several genes with unknown functions were also identified as components of the σH regulon (see Table S6 in the supplemental material). Investigations of the regulation and function of these genes will improve our understanding of molecular mechanisms of stress response in C. glutamicum.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Crispinus A. Omumasaba (Research institute of Innovative Technology for the Earth [RITE]) for critical reading of the manuscript and Norihiko Takemoto (RITE) for technical assistance with HPLC experiments.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/JB.02248-14.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kumagai H. 2000. Microbial production of amino acids in Japan. Adv Biochem Eng Biotechnol 69:71–85. doi: 10.1007/3-540-44964-7_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hermann T. 2003. Industrial production of amino acids by coryneform bacteria. J Biotechnol 104:155–172. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1656(03)00149-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Inui M, Kawaguchi H, Murakami S, Vertès AA, Yukawa H. 2004. Metabolic engineering of Corynebacterium glutamicum for fuel ethanol production under oxygen-deprivation conditions. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol 8:243–254. doi: 10.1159/000086705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wendisch VF, Bott M, Eikmanns BJ. 2006. Metabolic engineering of Escherichia coli and Corynebacterium glutamicum for biotechnological production of organic acids and amino acids. Curr Opin Microbiol 9:268–274. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2006.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith KM, Cho KM, Liao JC. 2010. Engineering Corynebacterium glutamicum for isobutanol production. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 87:1045–1055. doi: 10.1007/s00253-010-2522-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yamamoto S, Suda M, Niimi S, Inui M, Yukawa H. 2013. Strain optimization for efficient isobutanol production using Corynebacterium glutamicum under oxygen deprivation. Biotechnol Bioeng 110:2938–2948. doi: 10.1002/bit.24961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schneider J, Wendisch VF. 2010. Putrescine production by engineered Corynebacterium glutamicum. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 88:859–868. doi: 10.1007/s00253-010-2778-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mimitsuka T, Sawai H, Hatsu M, Yamada K. 2007. Metabolic engineering of Corynebacterium glutamicum for cadaverine fermentation. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 71:2130–2135. doi: 10.1271/bbb.60699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Okino S, Suda M, Fujikura K, Inui M, Yukawa H. 2008. Production of d-lactic acid by Corynebacterium glutamicum under oxygen deprivation. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 78:449–454. doi: 10.1007/s00253-007-1336-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lonetto MA, Brown KL, Rudd KE, Buttner MJ. 1994. Analysis of the Streptomyces coelicolor sigE gene reveals the existence of a subfamily of eubacterial RNA polymerase sigma factors involved in the regulation of extracytoplasmic functions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 91:7573–7577. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.16.7573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Helmann JD. 2002. The extracytoplasmic function (ECF) sigma factors. Adv Microb Physiol 46:47–110. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2911(02)46002-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Engels S, Schweitzer JE, Ludwig C, Bott M, Schaffer S. 2004. clpC and clpP1P2 gene expression in Corynebacterium glutamicum is controlled by a regulatory network involving the transcriptional regulators ClgR and HspR as well as the ECF sigma factor σH. Mol Microbiol 52:285–302. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2003.03979.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim TH, Kim HJ, Park JS, Kim Y, Kim P, Lee HS. 2005. Functional analysis of sigH expression in Corynebacterium glutamicum. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 331:1542–1547. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.04.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ehira S, Teramoto H, Inui M, Yukawa H. 2009. Regulation of Corynebacterium glutamicum heat shock response by the extracytoplasmic-function sigma factor SigH and transcriptional regulators HspR and HrcA. J Bacteriol 191:2964–2972. doi: 10.1128/JB.00112-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaushal D, Schroeder BG, Tyagi S, Yoshimatsu T, Scott C, Ko C, Carpenter L, Mehrotra J, Manabe YC, Fleischmann RD, Bishai WR. 2002. Reduced immunopathology and mortality despite tissue persistence in a Mycobacterium tuberculosis mutant lacking alternative sigma factor, SigH. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 99:8330–8335. doi: 10.1073/pnas.102055799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Raman S, Song T, Puyang X, Bardarov S, Jacobs WR Jr, Husson RN. 2001. The alternative sigma factor SigH regulates major components of oxidative and heat stress responses in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J Bacteriol 183:6119–6125. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.20.6119-6125.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Manganelli R, Dubnau E, Tyagi S, Kramer FR, Smith I. 1999. Differential expression of 10 sigma factor genes in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Mol Microbiol 31:715–724. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01212.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Paget MS, Bae JB, Hahn MY, Li W, Kleanthous C, Roe JH, Buttner MJ. 2001. Mutational analysis of RsrA, a zinc-binding anti-sigma factor with a thiol-disulphide redox switch. Mol Microbiol 39:1036–1047. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02298.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paget MS, Kang JG, Roe JH, Buttner MJ. 1998. sigmaR, an RNA polymerase sigma factor that modulates expression of the thioredoxin system in response to oxidative stress in Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2). EMBO J 17:5776–5782. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.19.5776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Park JH, Roe JH. 2008. Mycothiol regulates and is regulated by a thiol-specific antisigma factor RsrA and sigma(R) in Streptomyces coelicolor. Mol Microbiol 68:861–870. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06191.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kallifidas D, Thomas D, Doughty P, Paget MS. 2010. The sR regulon of Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) reveals a key role in protein quality control during disulphide stress. Microbiology 156:1661–1672. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.037804-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Song T, Dove SL, Lee KH, Husson RN. 2003. RshA, an anti-sigma factor that regulates the activity of the mycobacterial stress response sigma factor SigH. Mol Microbiol 50:949–959. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03739.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kang JG, Paget MS, Seok YJ, Hahn MY, Bae JB, Hahn JS, Kleanthous C, Buttner MJ, Roe JH. 1999. RsrA, an anti-sigma factor regulated by redox change. EMBO J 18:4292–4298. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.15.4292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Antelmann H, Helmann JD. 2011. Thiol-based redox switches and gene regulation. Antioxid Redox Signal 14:1049–1063. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Busche T, Šilar R, Pičmanová M, Pátek M, Kalinowski J. 2012. Transcriptional regulation of the operon encoding stress-responsive ECF sigma factor SigH and its anti-sigma factor RshA, and control of its regulatory network in Corynebacterium glutamicum. BMC Genomics 13:445. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-13-445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Engels S, Ludwig C, Schweitzer JE, Mack C, Bott M, Schaffer S. 2005. The transcriptional activator ClgR controls transcription of genes involved in proteolysis and DNA repair in Corynebacterium glutamicum. Mol Microbiol 57:576–591. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04710.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nakunst D, Larisch C, Hüser AT, Tauch A, Pühler A, Kalinowski J. 2007. The extracytoplasmic function-type sigma factor SigM of Corynebacterium glutamicum ATCC 13032 is involved in transcription of disulfide stress-related genes. J Bacteriol 189:4696–4707. doi: 10.1128/JB.00382-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Choi WW, Park SD, Lee SM, Kim HB, Kim Y, Lee HS. 2009. The whcA gene plays a negative role in oxidative stress response of Corynebacterium glutamicum. FEMS Microbiol Lett 290:32–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2008.01398.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kim TH, Park JS, Kim HJ, Kim Y, Kim P, Lee HS. 2005. The whcE gene of Corynebacterium glutamicum is important for survival following heat and oxidative stress. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 337:757–764. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.09.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim MS, Dufour YS, Yoo JS, Cho YB, Park JH, Nam GB, Kim HM, Lee KL, Donohue TJ, Roe JH. 2012. Conservation of thiol-oxidative stress responses regulated by SigR orthologues in actinomycetes. Mol Microbiol 85:326–344. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2012.08115.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Inui M, Murakami S, Okino S, Kawaguchi H, Vertès AA, Yukawa H. 2004. Metabolic analysis of Corynebacterium glutamicum during lactate and succinate productions under oxygen deprivation conditions. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol 7:182–196. doi: 10.1159/000079827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Toyoda K, Teramoto H, Inui M, Yukawa H. 2011. Genome-wide identification of in vivo binding sites of GlxR, a cyclic AMP receptor protein-type regulator in Corynebacterium glutamicum. J Bacteriol 193:4123–4133. doi: 10.1128/JB.00384-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Toyoda K, Teramoto H, Gunji W, Inui M, Yukawa H. 2013. Involvement of regulatory interactions among global regulators GlxR, SugR, and RamA in expression of ramA in Corynebacterium glutamicum. J Bacteriol 195:1718–1726. doi: 10.1128/JB.00016-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Toyoda K, Teramoto H, Inui M, Yukawa H. 2008. Expression of the gapA gene encoding glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase of Corynebacterium glutamicum is regulated by the global regulator SugR. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 81:291–301. doi: 10.1007/s00253-008-1682-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Waldminghaus T, Skarstad K. 2010. ChIP on chip: surprising results are often artifacts. BMC Genomics 11:414. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-11-414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Homann OR, Johnson AD. 2010. MochiView: versatile software for genome browsing and DNA motif analysis. BMC Biol 8:49. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-8-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bailey TL, Elkan C. 1994. Fitting a mixture model by expectation maximization to discover motifs in biopolymers. Proc Int Conf. Intell Syst Mol Biol 2:28–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Teramoto H, Suda M, Inui M, Yukawa H. 2010. Regulation of the expression of genes involved in NAD de novo biosynthesis in Corynebacterium glutamicum. Appl Environ Microbiol 76:5488–5495. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00906-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Takemoto N, Tanaka Y, Inui M, Yukawa H. 2014. The physiological role of riboflavin transporter and involvement of FMN-riboswitch in its gene expression in Corynebacterium glutamicum. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 98:4159–4168. doi: 10.1007/s00253-014-5570-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Inui M, Suda M, Okino S, Nonaka H, Puskás LG, Vertès AA, Yukawa H. 2007. Transcriptional profiling of Corynebacterium glutamicum metabolism during organic acid production under oxygen deprivation conditions. Microbiology 153:2491–2504. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2006/005587-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Miller JH. 1972. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yukawa H, Omumasaba CA, Nonaka H, Kós P, Okai N, Suzuki N, Suda M, Tsuge Y, Watanabe J, Ikeda Y, Vertès AA, Inui M. 2007. Comparative analysis of the Corynebacterium glutamicum group and complete genome sequence of strain R. Microbiology 153:1042–1058. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2006/003657-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fernandes ND, Wu QL, Kong D, Puyang X, Garg S, Husson RN. 1999. A mycobacterial extracytoplasmic sigma factor involved in survival following heat shock and oxidative stress. J Bacteriol 181:4266–4274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kalinowski J, Bathe B, Bartels D, Bischoff N, Bott M, Burkovski A, Dusch N, Eggeling L, Eikmanns BJ, Gaigalat L, Goesmann A, Hartmann M, Huthmacher K, Kramer R, Linke B, McHardy AC, Meyer F, Mockel B, Pfefferle W, Pühler A, Rey DA, Ruckert C, Rupp O, Sahm H, Wendisch VF, Wiegrabe I, Tauch A. 2003. The complete Corynebacterium glutamicum ATCC 13032 genome sequence and its impact on the production of L-aspartate-derived amino acids and vitamins. J Biotechnol 104:5–25. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1656(03)00154-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Holátko J, Elišáková V, Prouza M, Sobotka M, Nešvera J, Pátek M. 2009. Metabolic engineering of the l-valine biosynthesis pathway in Corynebacterium glutamicum using promoter activity modulation. J Biotechnol 139:203–210. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2008.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Flint DH, Emptage MH, Finnegan MG, Fu W, Johnson MK. 1993. The role and properties of the iron-sulfur cluster in Escherichia coli dihydroxy-acid dehydratase. J Biol Chem 268:14732–14742. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Flint DH, Tuminello JF, Emptage MH. 1993. The inactivation of Fe-S cluster containing hydro-lyases by superoxide. J Biol Chem 268:22369–22376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ren B, Zhang N, Yang J, Ding H. 2008. Nitric oxide-induced bacteriostasis and modification of iron-sulphur proteins in Escherichia coli. Mol Microbiol 70:953–964. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06464.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hyduke DR, Jarboe LR, Tran LM, Chou KJ, Liao JC. 2007. Integrated network analysis identifies nitric oxide response networks and dihydroxyacid dehydratase as a crucial target in Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 104:8484–8489. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610888104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Brown OR, Yein F. 1978. Dihydroxyacid dehydratase: the site of hyperbaric oxygen poisoning in branch-chain amino acid biosynthesis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 85:1219–1224. doi: 10.1016/0006-291X(78)90672-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cronan JE, Zhao X, Jiang Y. 2005. Function, attachment and synthesis of lipoic acid in Escherichia coli. Adv Microb Physiol 50:103–146. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2911(05)50003-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]