Abstract

Alterations in apical junctional complexes (AJCs) have been reported in genetic or acquired biliary diseases. The vitamin D nuclear receptor (VDR), predominantly expressed in biliary epithelial cells in the liver, has been shown to regulate AJCs. The aim of our study was thus to investigate the role of VDR in the maintenance of bile duct integrity in mice challenged with biliary-type liver injury. Vdr−/− mice subjected to bile duct ligation (BDL) displayed increased liver damage compared to wildtype BDL mice. Adaptation to cholestasis, ascertained by expression of genes involved in bile acid metabolism and tissue repair, was limited in Vdr−/− BDL mice. Furthermore, evaluation of Vdr−/− BDL mouse liver tissue sections indicated altered E-cadherin staining associated with increased bile duct rupture. Total liver protein analysis revealed that a truncated form of E-cadherin was present in higher amounts in Vdr−/− mice subjected to BDL compared to wildtype BDL mice. Truncated E-cadherin was also associated with loss of cell adhesion in biliary epithelial cells silenced for VDR. In these cells, E-cadherin cleavage occurred together with calpain 1 activation and was prevented by the silencing of calpain 1. Furthermore, VDR deficiency led to the activation of the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) pathway, while EGFR activation by EGF induced both calpain 1 activation and E-cadherin cleavage in these cells. Finally, truncation of E-cadherin was blunted when EGFR signaling was inhibited in VDR-silenced cells. Conclusion: Biliary-type liver injury is exacerbated in Vdr−/− mice by limited adaptive response and increased bile duct rupture. These results indicate that loss of VDR restricts the adaptation to cholestasis and diminishes bile duct integrity in the setting of biliary-type liver injury. (Hepatology 2013;58:1401–1412)

Biliary epithelial cells form a protective physical barrier between liver parenchyma and the toxic compounds that are secreted in bile. The cohesion of biliary epithelial cells is maintained by apical junctional complexes (AJCs), such as tight junctions and adherens junctions. Disturbance of adherens junction integrity during development leads to defective bile duct structure that translates into cholestasis, as in the arthrogryposis, renal dysfunction, and cholestasis (ARC) syndrome.1 Mutations in the claudin-1 gene, a gene encoding a tight junction protein, cause sclerosing cholangitis, as evidenced in the neonatal ichthyosis and sclerosing cholangitis (NISCH) syndrome.2 In the NISCH syndrome, sclerosing cholangitis has been assigned to the increase in cellular permeability that has been evidenced in biliary epithelial cells with diminished claudin-1 expression.3 In acquired cholestatic diseases, such as primary biliary cirrhosis, tight junctions between biliary epithelial cells are also disrupted.4

Tight junctions control the paracellular movement of ions and solutes between cells,5 while adherens junctions govern the physical epithelial barrier by enabling direct cell-to-cell interactions.6 The formation of AJCs is a dynamic process regulated by transcriptional and posttranslational mechanisms.7 As an example, the formation of adherens junctions is induced by vitamin D through the activation of PKC in keratinocytes.8 In colon cancer cells, the transcription of E-cadherin, zonula occludens-1, claudin-1, and claudin-2 is controlled by vitamin D through the activation of the vitamin D nuclear receptor (VDR).9,10 Consistently, Vdr knockout mice challenged with dextran sodium sulfate display AJCs alterations leading to intestinal barrier disruption.9

In the liver, the expression of VDR is restricted to nonparenchymal cells, such as biliary epithelial cells.11,12 In these cells, VDR has a direct protective function by promoting epithelial antibacterial defense that may be beneficial in cholestatic settings.11 Moreover, extrahepatic signals triggered by the vitamin D-VDR axis may also protect hepatocytes from cholestatic injuries by controlling the expression of genes involved in bile acid metabolism and transport.13,14 The potential involvement of VDR in cholestatic diseases is highlighted by the association of VDR polymorphisms with increased susceptibility to primary biliary cirrhosis.15 Therefore, we tested the hypothesis that VDR may protect the liver from biliary-type hepatic injury by controlling AJCs.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Vdr−/+ heterozygous mice (B6.129S4-Vdrtm1Mbd/J) were obtained from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA).16 Vdr−/− knockout and Vdr+/+ wildtype mice were generated by heterozygous breeding. Animals were housed in a conventional facility and had free access to water. Mineral ion levels were normalized in Vdr−/− mice by feeding a rescue diet (TD96348, Harlan Laboratories, Indianapolis, IN) containing 2% calcium, 1.25% phosphorus, 20% lactose, and 2.2 IU vitamin D/g from weaning.17 C57BL/6J wildtype mice (Janvier Europe, St Berthevin, France) were fed either a regular chow diet or the rescue diet from weaning. All experiments were performed according to national guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals and protocols were approved by the Ethics Committee in Animal Experiment Charles Darwin of UPMC (Approval number: Ce5/2010/024).

Animal Surgery

Experiments were performed using Vdr−/− mice, wildtype littermates, or C57BL/6J wildtype mice at 8 to 10 weeks of age. Biliary-type liver injury was performed under isoflurane anesthesia by double ligation and section of the common bile duct (BDL). Sham-operated mice underwent laparotomy with exposure of the common bile duct, without ligation. A group of C57BL/6J wildtype mice under regular chow diet was injected intraperitoneally with 1α-hydroxyvitamin D3 (1α(OH)D3; 31 nmol/kg) or vehicle (olive oil) 1 day before and 1 and 2 days after surgery, as described.13 Three days after surgery, liver of all mice was collected under isoflurane anesthesia and blood was withdrawn from the vena cava. Liver samples were fixed in 4% formalin and embedded in paraffin for histology. Aliquots of the liver were embedded in TissueTek O.C.T. Compound (Electron Microscopy Sciences, Hatfield, PA) for cryosections, or snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C for RNA, protein, and bile acid analyses.

Cell Culture and Transient Transfection

The human biliary epithelial cell line Mz-ChA-118 was cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM), supplemented with 1 g/L glucose, 10 mmol/L Hepes, and 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), under 95% air and 5% CO2 at 37°C. The culture medium was renewed every 48 hours. For transient transfection experiments, Mz-ChA-1 cells were seeded into 12-well plates (100,000 cells/well). Cells were transfected using Lipofectamine 2000 (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA) with either human VDR, Calpain 1, or epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) ON-TARGETplus SMART pools small interfering RNA (siRNA), or with a nontargeting siRNA (Thermo Scientific, Waltham, MA). Six hours after transfection, cells were transferred overnight to serum-free medium and were maintained in culture for a total of 72 hours after transfection. For investigations of the EGFR pathway, Mz-ChA-1 cells were incubated in serum-free medium for 24 hours before starting the experiments and then treated with EGF (50 ng/mL; PeproTech, Rocky Hill, NJ) for 5 minutes to 48 hours. In some experiments, cells were preincubated with an EGFR inhibitor, AG1478 (10 μM; Calbiochem, Merck, Darmstadt, Germany).

Biochemistry and Bile Acid Measurement

Plasma concentrations of bile acids, aspartate, and alanine aminotransferases were determined with a Beckman Coulter AU640 analyzer. Bile acid pool composition and tetrahydroxylated bile acids were measured in the liver by high-performance liquid chromatography coupled to tandem mass spectrometry (HPLC-MS/MS) as described.19

Histology, Immunohistochemistry, and Immunocytology

For histology, sections (5 μm) of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded liver tissue were stained with hemalun, phloxin, safran (HPS) or Sirius red. For immunohistochemistry, cryosections of liver tissue were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 minutes at room temperature. Briefly, sections were permeabilized and blocked in 0.02% Surfact-Amps X100 (Thermo Scientific) with 100 mM glycine and 1% albumin for 1 hour at room temperature. Sections were then incubated overnight at 4°C with a primary antibody against E-cadherin. Secondary antibody was a Cyanine 3 (Cy3)-conjugated goat anti-rat antibody (dilution 1:100; Life Technologies) and DAPI was used for nuclei staining (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Liver tissue section immunostained for E-cadherin were then analyzed by an investigator unaware of the mouse genotype (D.F.). Typical bile ducts displayed membranous E-cadherin expression between biliary epithelial cells. Bile ducts were considered as ruptured when E-cadherin staining was absent between at least two adjacent biliary epithelial cells. For immunocytology, Mz-ChA-1 cells were grown on glass, fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 minutes, permeabilized and blocked in 0.02% Surfact-Amps X100 (Thermo Scientific) with 1% albumin and 10% goat serum for 1 hour at room temperature. Cells were then incubated overnight at 4°C with a primary antibody against E-cadherin. Primary antibody was revealed by an Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated goat anti-mouse secondary antibody (dilution 1:200; Life Technologies) and DAPI was used for nuclei staining. All antibodies used for immunodetection are listed in Supporting Table 1.

Immunoblot

Liver samples and Mz-ChA-1 cells were either disrupted with tungsten carbide beads and a TissueLyser apparatus (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) or directly lysed in RIPA buffer, respectively. RIPA lysis buffer was composed of 50 mmol/L Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 450 mmol/L NaCl, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 1% NP-40, and supplemented with 1 mM orthovanadate and a protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN). After centrifugation for 15 minutes at 4°C, supernatants were collected and protein concentration was determined using the BCA Protein Assay (Thermo Scientific). Equal amounts of proteins were resolved by 8% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and then processed for conventional western blot, using 0.2 μm nitrocellulose membranes and the antibodies listed in Supporting Table 1.

Quantitative Polymerase Chain Reaction (qPCR)

Total RNA was extracted from liver samples using TissueLyser apparatus and RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen). Complementary DNA was synthesized from 1 μg of total RNA using random hexamer primers and 200 U of Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (Life Technologies) for 1 hour at 37°C. qPCR was performed using the Platinum SYBR Green qPCR SuperMix-UDG (Life Technologies) on a LightCycler 1.5 (Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland). Sequences of primers used in qPCR are listed in Supporting Table 2. Results are reported relative to a calibrator according to the 2-ΔΔCt method with glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (Gapdh) used as the reference gene.

Protein Identification by Mass Spectrometry

Whole liver protein extracts were immunoprecipitated with an antibody directed against E-cadherin (Supporting Table 1). Precipitated proteins were submitted to SDS-PAGE, silver stained, and extracted from gel before mass spectrometry analysis, as described in the Supporting Material.

Statistical Analysis

Comparisons were made using Student t test. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results

BDL-Induced Liver Injury Is Exacerbated in Vdr−/− Mice

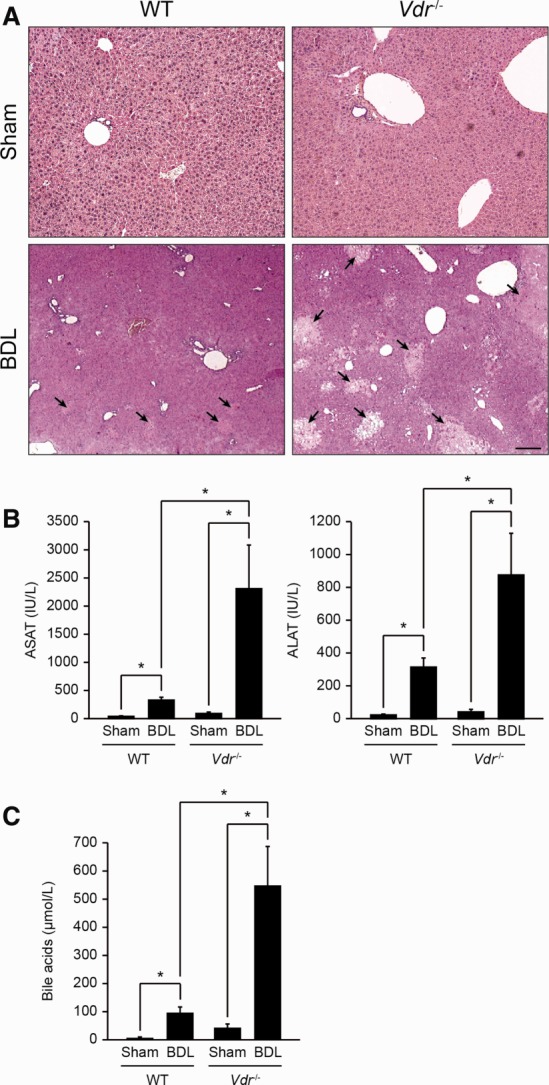

Vdr−/− mice displayed more hepatic damage than wildtype mice at histological examination of the liver 3 days after BDL (Fig. 1A). Accordingly, aminotransaminase activities were higher in Vdr−/− mice compared to control mice (Fig. 1B). Plasma bile acid levels were increased four times more in Vdr−/− mice than in wildtype mice after BDL (Fig. 1C). These observations indicate that Vdr−/− mice display more severe hepatic injury after biliary-type liver disease. To ascertain the potential protective role of VDR activation, wildtype mice submitted to BDL were injected with 1α(OH)D3, as described.13 Aminotransaminase activities and bile acid plasma levels were not significantly modified by exposure to 1α(OH)D3 (Supporting Fig. 1). Taken together, these results indicate that the absence of VDR is a susceptibility factor to biliary-type liver injury.

Fig 1.

Liver injury in Vdr−/− mice. (A) Liver samples were collected from Sham or BDL, wildtype (WT), and Vdr−/− mice 3 days post-BDL and stained by HPS. Liver was morphologically normal in WT and Vdr−/− sham mice (upper panels). After BDL the number and extent of bile infarcts (arrows) were higher in Vdr−/− (right lower panel) than in WT (left lower panel) mice. Scale bar = 50 μm. (B) Blood samples were collected from Sham or BDL, WT, and Vdr−/− mice 3 days post-BDL. Panel shows plasma concentrations of aspartate aminotransferase (left histogram), and alanine aminotransferase (right histogram). Data represent means ± SEM of 5-6 animals. *P < 0.05. (C) Blood samples were collected from Sham or BDL, WT, and Vdr−/− mice 3 days post-BDL. Panel shows plasma concentrations of bile acids. Data represent means ± SEM of 5-6 animals. *P < 0.05.

Vdr−/− Mice Are Unable to Develop Adaptive Response

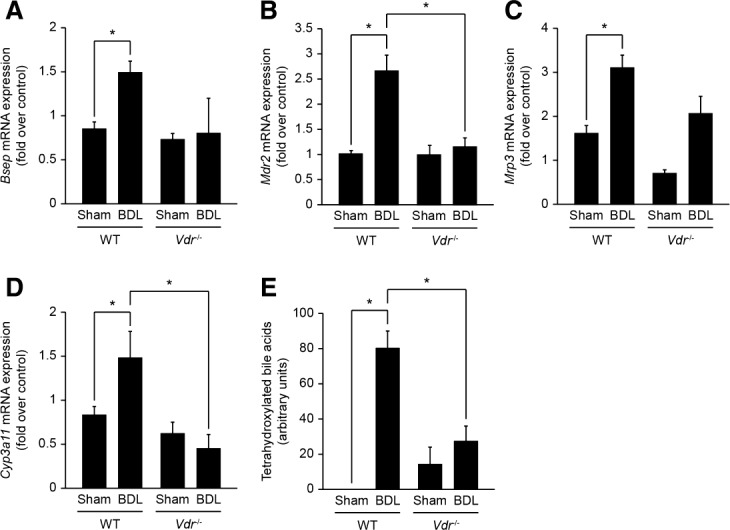

The extent of hepatic damage following biliary-type liver injury is limited by adaptive changes in bile acid metabolism and transport.20 The expression of cholesterol 7-alpha-hydroxylase (Cyp7a1) and sterol 12-alpha-hydroxylase (Cyp8b1) messenger RNA (mRNA) was decreased to a similar extent in both genotypes after BDL (Supporting Fig. 2). Consistently, the bile acid pool composition was similar in Vdr−/− and wildtype BDL mice (Supporting Fig. 3). Transcript levels of Na+-taurocholate cotransporting polypeptide (Ntcp) were also similarly decreased in both genotypes after BDL (Supporting Fig. 2). By contrast, the expression of the bile salt export pump (Bsep) and the phospholipid flippase (Mdr2), which is increased in cholestatic settings,21 was unchanged in Vdr−/− mice after BDL (Fig. 2A,B). Expression of the multidrug resistance-associated protein 3 (Mrp3) mRNA was induced in both genotypes after BDL, but this increase was less prominent in Vdr−/− mice (Fig. 2C). Finally, the expression of cytochrome P450 3a11 (Cyp3a11) mRNA increased in wildtype but not in Vdr−/− mice after BDL (Fig. 2D). The absence of Cyp3a11-mediated response in Vdr−/− mice was confirmed by the lack of a significant increase in hepatic tetrahydroxylated bile acids after BDL (Fig. 2E).22 Functional loss of liver parenchyma and of bile ducts during biliary-type liver injury is limited by tissue scarring and ductular reaction, respectively.23,24 Accordingly, liver of mice from both genotypes presented slight collagen deposits in the periportal area 3 days post-BDL. No difference, however, was evident between Vdr−/− mice and control littermates based on Sirius red staining (Fig. 3A). At mRNA levels, the expression of Tgf-β, α-Sma and type I collagen (Col1a1) was significantly increased in wildtype mice, but was not modified in Vdr−/− mice after BDL (Fig. 3B-D). Furthermore, histological examination of the liver suggested that Vdr−/− mice developed less ductular reaction than wildtype mice in response to BDL (Fig. 3E). This result was supported by the analysis of cytokeratin 19 (Ck19) mRNA expression, which was significantly increased after BDL in wildtype animals but not in Vdr−/− mice (Fig. 3F). Altogether, these results indicate that Vdr−/− mice are unable to display an effective adaptive response to biliary-type liver injury.

Fig 2.

Adaptive changes in bile acid metabolism and transport in Vdr−/− mice after BDL. Liver samples of Sham or BDL, wildtype (WT), and Vdr−/− mice were analyzed 3 days post-BDL by qPCR for mRNA expression of Bsep (A), Mdr2 (B), Mrp3 (C), and Cyp3a11 (D). Data were normalized to Gapdh and represent means ± SEM of 5-6 animals. *P < 0.05. (E) Tetrahydroxylated bile acids were analyzed by mass spectrometry in liver samples of Sham or BDL, WT, and Vdr−/− mice 3 days post-BDL. Data represent means ± SEM of 5-6 animals and are expressed as arbitrary units. Total tetrahydroxylated bile acids represent no more than 4% of the total bile acid pool in the setting of BDL.22 *P < 0.05.

Fig 3.

Fibrogenic and ductular response in Vdr−/− mice after BDL. Liver samples were collected from Sham or BDL, wildtype (WT), and Vdr−/− mice 3 days post-BDL. (A) Collagen deposits evaluated by Sirius red staining were increased 3 days post-BDL but were not different between genotypes. Scale bar = 50 μm. mRNA expression of Tgf-β (B), α-Sma (C), and Col1a1 (D) were analyzed by qPCR. Data were normalized to Gapdh and represent means ± SEM of 5-6 animals. *P < 0.05. (E) Compared with WT mice, Vdr−/− mice displayed little ductular reaction 3 days post-BDL (arrowheads). Scale bar = 25 μm. mRNA expression of Ck19 (F) was examined by qPCR. Data were normalized to Gapdh and represent means ± SEM of 5-6 animals. *P < 0.05.

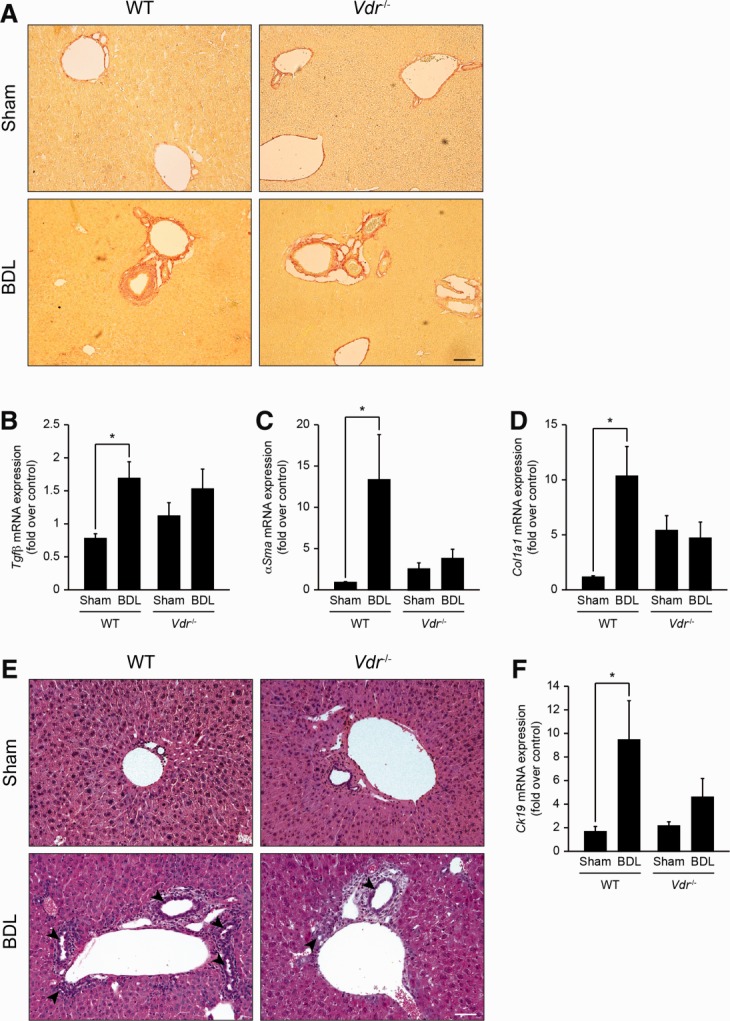

Vdr−/− Mice Develop Prominent Bile Duct Alterations

Liver damage in biliary-type liver injury results from the release of toxic bile from leaky bile ducts.25,26 Because VDR controls AJCs in other epithelia,9,10 we assessed hepatic E-cadherin expression by immunostaining in Vdr−/− and wildtype mice. In sham-operated mice of both genotypes, E-cadherin expression was evident at the membrane of biliary epithelial cells. After BDL, biliary epithelial cells displayed an altered staining pattern of E-cadherin, corresponding to bile duct disruption. Ruptured bile ducts were two times more frequent in Vdr−/− mice than in wildtype mice (Fig. 4A). These results suggest that alteration of adherens junctions leads to AJCs defects in the biliary epithelial cells of Vdr−/− mice submitted to biliary-type liver injury. Moreover, these observations suggest that the increased liver injury observed in these mice is related to the disruption of cell-cell interactions between biliary epithelial cells. E-cadherin protein content in whole liver, however, was not significantly different between wildtype and Vdr−/− mice after BDL. Yet Vdr−/− mice were characterized by a marked increase in the expression of a lower weight E-cadherin signal after BDL (Fig. 4B). Analysis of this 100-kDa protein signal by mass spectrometry indicated that it corresponded to a truncated form of E-cadherin that was previously described to promote cellular dissociation (Fig. 4C).27 These results therefore suggest that the bile duct rupture observed in Vdr−/− mice is related to a loss of adherens junctions in biliary epithelial cells caused by E-cadherin truncation.

Fig 4.

E-cadherin expression in Vdr−/− mice. (A) Representative immunostaining of E-cadherin in the liver of Sham or BDL, wildtype (WT), and Vdr−/− mice 3 days post-BDL. E-cadherin staining was interrupted (arrows) more often in BDL Vdr−/− (lower right panel) than in WT mice (lower left panel), indicative of higher incidence of bile duct rupture (33.0 ± 0.04% and 14.8 ± 0.08% of bile ducts, respectively). Scale bar = 10 μm. (B) Liver samples were collected from Sham or BDL, WT, and Vdr−/− mice 3 days post-BDL and were assessed for E-cadherin expression by immunoblot. β-Actin was used as an internal control. (C) Whole liver protein extracts were immunoprecipitated with an antibody directed against E-cadherin. After gel migration, the 100-kDa protein signal was extracted and submitted to mass spectrometry analysis. The full E-cadherin protein sequence is shown, with dark boxes representing the peptides identified by mass spectrometry. The underlined sequence corresponds to the calpain cleavage site consensus sequence.

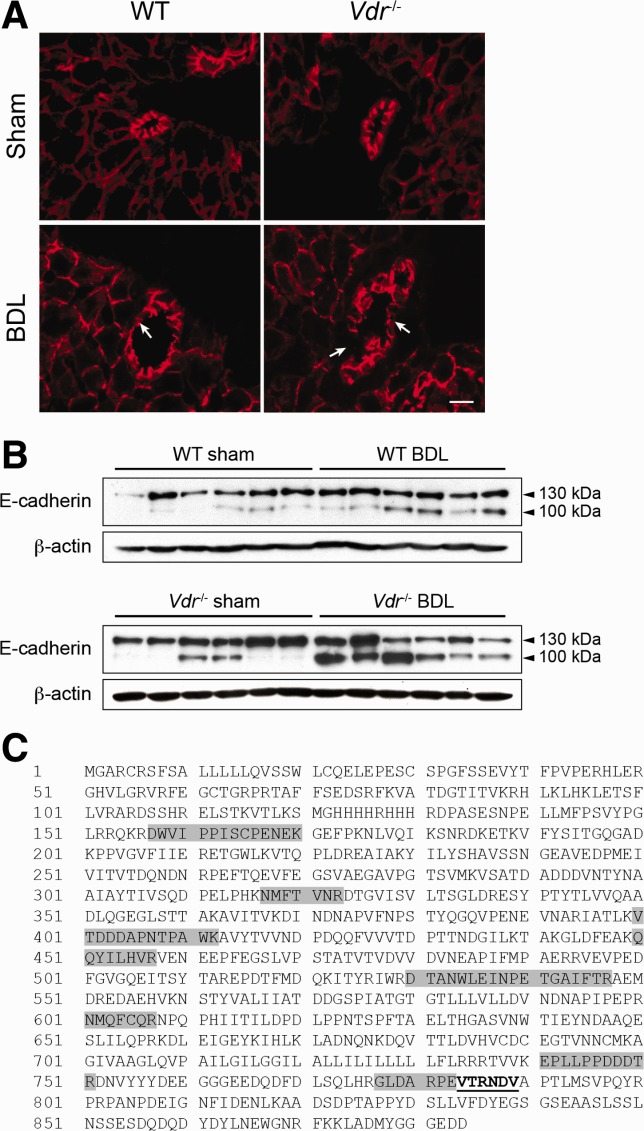

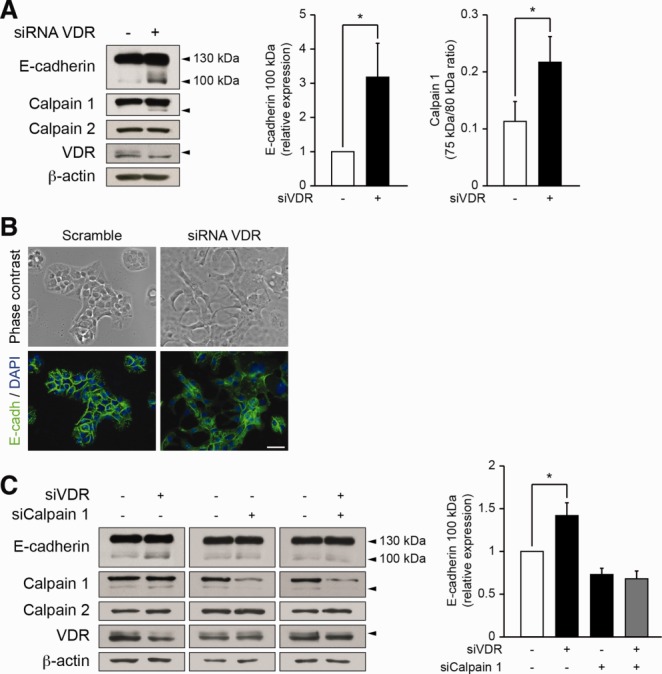

VDR Silencing Leads to E-cadherin Cleavage in Biliary Epithelial Cells

To investigate the impact of VDR on E-cadherin cleavage in biliary epithelial cells, we down-regulated VDR by siRNA in a biliary epithelial cell line. As shown in Fig. 5A, E-cadherin cleavage occurred in cells with diminished VDR expression. Furthermore, diminished VDR expression in biliary epithelial cells was associated with both the loss of regular E-cadherin membrane staining and the disruption of cell-cell contacts (Fig. 5B). Because the 100-kDa truncated form of E-cadherin has been shown to result from a calpain-mediated cleavage,28 we analyzed the effect of VDR down-regulation on calpain activation. A 75-kDa autocleaved fragment specific for calpain 1 activation was detected in biliary epithelial cells with diminished VDR expression,29 while no modification was found for calpain 2 (Fig. 5A). In biliary epithelial cells that were down-regulated for both VDR and calpain 1, no induction of E-cadherin cleavage could be observed, indicating that the E-cadherin cleavage observed in VDR-deficient cells is mediated by calpain 1 (Fig. 5C).

Fig 5.

E-cadherin cleavage in biliary epithelial cells with diminished VDR expression. Biliary epithelial cells were transfected either with scramble or VDR siRNA for 3 days and were subjected to (A) detection of E-cadherin, Calpain 1, Calpain 2, VDR, and β-actin expression by immunoblot. Histograms represent the densitometric analysis of relative E-cadherin 100 kDa and activated Calpain 1 expression. Data represent means ± SEM of at least six independent experiments. *P < 0.05. (B) Morphologic analysis and E-cadherin (green) localization by immunocytofluorescence. Nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). Scale bar = 25 μm. (C) Biliary epithelial cells were transfected either with scramble, VDR siRNA, Calpain 1 siRNA, or a combination of VDR and Calpain 1 siRNA for 3 days. Total protein extracts were then subjected to detection of E-cadherin, Calpain 1, Calpain 2, VDR, and β-actin expression by immunoblot. Histogram represent the densitometric analysis of relative E-cadherin 100 kDa expression. Data represent means ± SEM of six independent experiments.

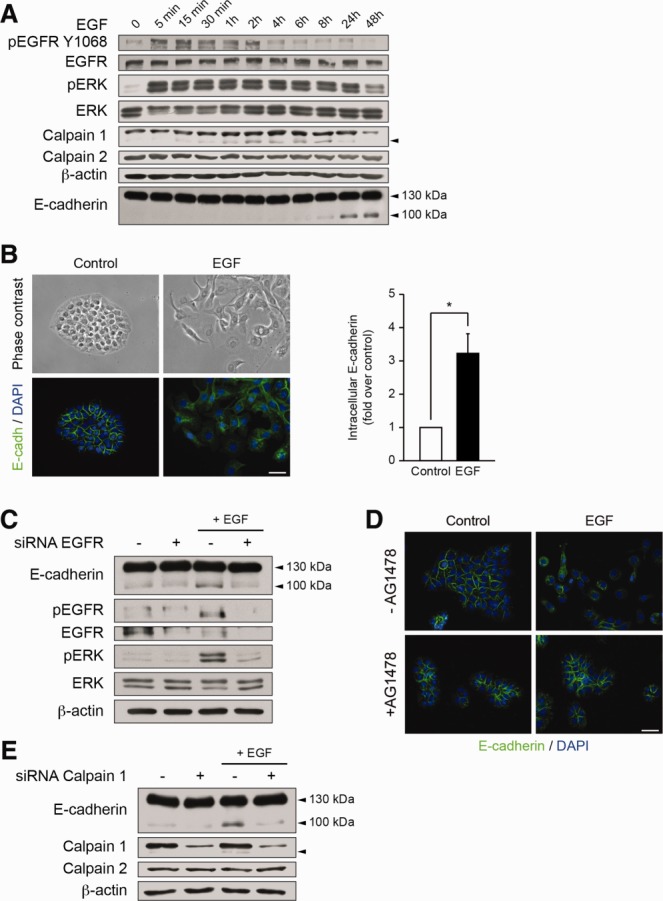

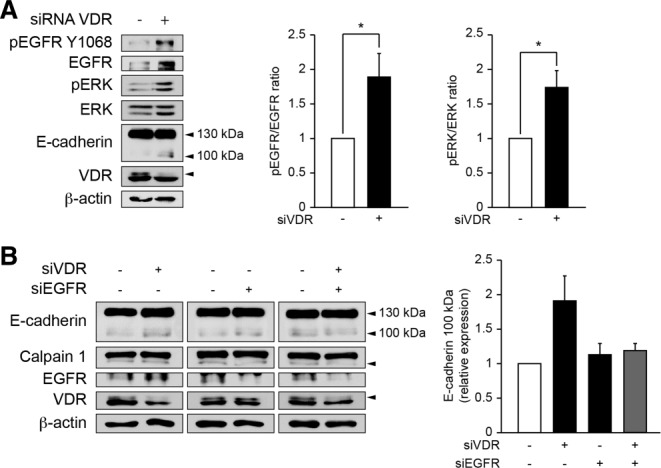

VDR Down-Regulation Activates Calpain 1 Through the EGFR Signaling Pathway in Biliary Epithelial Cells

Calpain activation may be triggered by the EGFR pathway in fibroblasts.30 Thus, we tested the potential of EGF to induce calpain 1 activation and E-cadherin cleavage in biliary epithelial cells. Time-course analysis showed that EGF induced calpain 1 activation, which preceded E-cadherin truncation (Fig. 6A). Consistently, biliary epithelial cells lost their cell-to-cell contacts, while E-cadherin staining became mainly intracellular (Fig. 6B). The effect of EGF on calpain 1 activation and subsequent E-cadherin truncation was abrogated when EGFR expression was diminished by siRNA (Fig. 6C). Furthermore, pharmacological inhibition of EGFR signaling by AG1478 maintained adherens junctions integrity in biliary epithelial cells treated with EGF (Fig. 6D). In biliary epithelial cells silenced for calpain 1, EGF was unable to induce E-cadherin cleavage (Fig. 6E). Thus, these results demonstrate that the EGFR pathway triggers calpain 1 activation, resulting in E-cadherin cleavage in biliary epithelial cells. Because the vitamin D-VDR axis has been shown to negatively regulate the EGFR pathway,31,32 we next analyzed the activation status of the EGFR pathway in VDR-silenced cells. EGFR signaling was increased in cells with diminished VDR expression as ascertained by higher EGFR, phosphorylated EGFR, and phosphorylated ERK protein levels (Fig. 7A). In biliary epithelial cells down-regulated for both VDR and EGFR, calpain 1 activation and E-cadherin cleavage were blunted when compared to VDR-silenced cells (Fig. 7B). These findings therefore indicate that downregulation of VDR triggers the EGFR signaling pathway, resulting in calpain 1-activation and subsequent E-cadherin cleavage.

Fig 6.

E-cadherin cleavage in biliary epithelial cells with activated EGFR-signaling pathway. (A) Biliary epithelial cells were incubated with EGF (50 ng/mL) for various periods of time. Whole cell protein extracts were then submitted to pEGFR Y1068, EGFR, pERK, ERK, Calpain 1, Calpain 2, E-cadherin, and β-actin immunoblot. Representative gels of five different experiments are shown. (B) Morphologic analysis of biliary epithelial cells and E-cadherin localization by immunocytofluorescence 48 hours after EGF treatment. Histogram represents the results of a blinded analysis estimating the number of cells with intracellular E-cadherin staining. Scale bar = 25 μm. (C) Biliary epithelial cells were transfected either with scramble or EGFR siRNA before being incubated with EGF for 24 hours. Total protein extracts were then submitted to pEGFR Y1068, EGFR, pERK, ERK, E-cadherin, and β-actin immunoblot. (D) E-cadherin localization in biliary epithelial cells is evidenced by immunocytofluorescence 2 days after EGF treatment, in the presence or absence of the EGFR inhibitor, AG1478. Scale bar = 25 μm. (E) Biliary epithelial cells were transfected either with scramble or Calpain 1 siRNA before being incubated with EGF for 24 hours. Total protein extracts were then submitted to E-cadherin, Calpain 1, Calpain 2, and β-actin immunoblot. Representative gels of five different experiments are shown.

Fig 7.

EGFR-signaling in biliary epithelial cells with diminished VDR expression. (A) Biliary epithelial cells were transfected either with scramble or VDR siRNA for 3 days. Total protein extracts were then submitted to pEGFR Y1068, EGFR, pERK, ERK, E-cadherin, VDR, and β-actin immunoblot. Histograms represent the densitometric analysis of the pEGFR to EGFR ratio and of the pERK to ERK ratio. Data represent means ± SEM of six independent experiments. *P < 0.05. (B) Biliary epithelial cells were transfected either with scramble, VDR siRNA, EGFR siRNA, or a combination of VDR and EGFR siRNA for 3 days. Total protein extracts were then subjected to detection of E-cadherin, Calpain 1, EGFR, VDR, and β-actin by immunoblot. Histogram represents the densitometric analysis of relative E-cadherin 100 kDa expression. Data represent means ± SEM of three independent experiments.

Discussion

In this study we show that loss of VDR exacerbates biliary-type liver injury. The hypothesis that VDR has a broad protective role in biliary-type liver injury was raised following our previous observation that VDR protects biliary epithelial cells by inducing innate defenses.11 In addition, the vitamin D-VDR axis has been shown to control genes involved in bile acid metabolism and transport, the regulation of which is crucial to protect the liver from cholestatic injury.13,14 However, VDR activation by acute vitamin D exposure did not provide protection towards BDL. Yet a chronic increase in vitamin D intake by means of rescue diet feeding led to a reduction in hepatic damage in wildtype mice submitted to BDL (Supporting Fig. 4). Because the rescue diet is also enriched in calcium, phosphorus, and lactose, the detailed molecular and cellular mechanisms triggering such a protective effect remain unknown. According to our observations, we can only speculate that the chronic intake of an increased exogenous vitamin D dose protects the liver from biliary injury. Taken together, our observations indicate that the absence of VDR is accountable for the observed susceptibility towards biliary-type liver injury.

The extent of injury following toxic bile accumulation in the liver parenchyma is counterbalanced by adaptive mechanisms.26 Vdr−/− mice were unable to efficiently adapt to biliary-type liver injury by modifying hepatocellular gene expression when compared to wildtype mice. Because VDR expression is absent from hepatocytes,11,12 the observation of a defective adaptation to cholestasis suggests that the triggering signals originate from non-parenchymal liver cells or extra-hepatic cells.13,14 Furthermore, only wildtype mice displayed a significant ductular proliferation assessed by increased Ck19 mRNA levels. Proliferating biliary epithelial cells have signaling activities towards hepatocytes,33 thus lack of ductular reaction in Vdr−/− mice may directly impact liver adaptive mechanisms to BDL. Moreover, ductular reaction may represent an evacuation route for bile in cholestatic settings.34 Thus, the absence of significant ductular reaction may increase toxic accumulation in Vdr−/− mice. These observations suggest that VDR has an indirect effect on hepatocytes that is required for the liver to adapt to biliary-type hepatic injury.

The release of toxic bile in liver parenchyma is directly related to the ability of biliary epithelial cells to maintain sealed ducts. Because VDR has been shown to control AJCs in other epithelia,9,10 we analyzed E-cadherin staining in mice submitted to BDL. Vdr−/− mice displayed more bile duct ruptures that paralleled defective E-cadherin staining, suggesting that VDR is required in biliary epithelial cells to ensure cell-cell interactions. The absence of VDR led to a strong increase in plasma bile acids and aminotransferases after BDL, further suggesting extensive bile spillover and subsequent increased hepatic toxicity. While no significant change could be observed in E-cadherin protein expression, we showed that a truncated form of E-cadherin was increased in Vdr−/− mice submitted to BDL. This truncated form of E-cadherin has been shown to induce epithelial cell dissociation,27 suggesting that the cleavage of E-cadherin leads to bile duct rupture. Moreover, we have shown that E-cadherin cleavage results from calpain 1-activation, as evidenced in biliary epithelial cells invalidated for VDR. The truncated form of E-cadherin was detected by immunoblot in whole liver lysates, suggesting that E-cadherin cleavage also occurs in hepatocytes. Calpain activation in hepatocytes may result from the release of activated calpain from biliary epithelial cells. Indeed, autoactivation of calpains was previously described as a self-perpetrating injury mechanism in the liver of rats submitted to chemical intoxication.35 Thus, our observations suggest that calpain activation and subsequent E-cadherin cleavage triggered by the absence of VDR leads to enhanced liver injury.

The EGFR pathway controls calpain 2-activation through ERK in fibroblasts.30 Herein, we show that EGF activates calpain 1 in biliary epithelial cells. Consistent with the observation that the vitamin D-VDR axis downregulates EGFR expression,31,32 we demonstrate that invalidation of VDR in biliary epithelial cells results in EGFR pathway activation. Furthermore, the cleavage of E-cadherin is not observed in biliary epithelial cells silenced for both VDR and EGFR. Taken together, these results indicate that loss of VDR controls E-cadherin cleavage in biliary epithelial cells by activating calpain 1 through the EGFR signaling pathway.

VDR gene polymorphisms have been associated with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD),36,37 a condition commonly associated with primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC).38 Increased intestinal permeability, a feature of IBD, may result from AJCs perturbations as evidenced in Vdr−/− mice submitted to dextran sodium sulfate.9 Intestinal permeability by allowing bacterial products to be released in the general circulation may aggravate PSC. First, bacterial products have been shown to exacerbate the immune attack against biliary epithelial cells.39 Second, endotoxins can trigger fibrosis by stimulating dedicated receptors on nonparenchymal liver cells.40 Accordingly, our data indicate that sham-operated Vdr−/− mice have an increased expression of profibrotic genes (i.e., α-Sma and Col1a1) compared to sham-operated wildtype mice. Finally, endotoxins may directly favor the disruption of biliary epithelial cell AJCs,41 a feature that has been documented in a mouse model of PSC.42 Thus, the vitamin D/VDR axis may be involved in the phenotypic features of PSC by both an indirect effect on intestinal permeability and a direct effect on nonparenchymal liver cells.

In conclusion, our data suggest that loss of VDR sensitizes the liver to biliary-type hepatic injury. VDR may be involved in such a process by controlling biliary epithelial cell innate immunity, through the induction of antibacterial defense11 and by ensuring epithelial cohesion, as demonstrated herein. The respective involvement in biliary diseases of VDR expressed in nonparenchymal liver cells or cells of extrahepatic origin remains, however, to be fully determined.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Cedric Broussard, from the proteomic platform of the Paris Descartes University (3P5), for excellent technical assistance in protein mass spectrometry identification. The authors thank Sylvie Dumont and Fatiha Mérabtène, from the histomorphology platform of IFR65 (UPMC), and the PHEA animal facility team for technical support.

Supporting Information

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article.

References

- 1.Cullinane AR, Straatman-Iwanowska A, Zaucker A, Wakabayashi Y, Bruce CK, Luo G, et al. Mutations in VIPAR cause an arthrogryposis, renal dysfunction and cholestasis syndrome phenotype with defects in epithelial polarization. Nat Genet. 2010;42:303–312. doi: 10.1038/ng.538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hadj-Rabia S, Baala L, Vabres P, Hamel-Teillac D, Jacquemin E, Fabre M, et al. Claudin-1 gene mutations in neonatal sclerosing cholangitis associated with ichthyosis: a tight junction disease. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:1386–1390. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grosse B, Cassio D, Yousef N, Bernardo C, Jacquemin E, Gonzales E. Claudin-1 involved in neonatal ichthyosis sclerosing cholangitis syndrome regulates hepatic paracellular permeability. Hepatology. 2012;55:1249–1259. doi: 10.1002/hep.24761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sakisaka S, Kawaguchi T, Taniguchi E, Hanada S, Sasatomi K, Koga H, et al. Alterations in tight junctions differ between primary biliary cirrhosis and primary sclerosing cholangitis. Hepatology. 2001;33:1460–1468. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2001.25086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hartsock A, Nelson WJ. Adherens and tight junctions: structure, function and connections to the actin cytoskeleton. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2008;1778:660–669. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2007.07.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hermiston ML, Gordon JI. In vivo analysis of cadherin function in the mouse intestinal epithelium: essential roles in adhesion, maintenance of differentiation, and regulation of programmed cell death. J Cell Biol. 1995;129:489–506. doi: 10.1083/jcb.129.2.489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meng W, Takeichi M. Adherens junction: molecular architecture and regulation. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2009;1:a002899. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a002899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gniadecki R, Gajkowska B, Hansen M. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 stimulates the assembly of adherens junctions in keratinocytes: involvement of protein kinase C. Endocrinology. 1997;138:2241–2248. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.6.5156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kong J, Zhang Z, Musch MW, Ning G, Sun J, Hart J, et al. Novel role of the vitamin D receptor in maintaining the integrity of the intestinal mucosal barrier. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2008;294:G208–216. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00398.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Palmer HG, Gonzalez-Sancho JM, Espada J, Berciano MT, Puig I, Baulida J, et al. Vitamin D(3) promotes the differentiation of colon carcinoma cells by the induction of E-cadherin and the inhibition of beta-catenin signaling. J Cell Biol. 2001;154:369–387. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200102028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.D'Aldebert E, Biyeyeme Bi Mve MJ, Mergey M, Wendum D, Firrincieli D, Coilly A, et al. Bile salts control the antimicrobial peptide cathelicidin through nuclear receptors in the human biliary epithelium. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:1435–1443. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.12.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gascon-Barre M, Demers C, Mirshahi A, Neron S, Zalzal S, Nanci A. The normal liver harbors the vitamin D nuclear receptor in nonparenchymal and biliary epithelial cells. Hepatology. 2003;37:1034–1042. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2003.50176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ogura M, Nishida S, Ishizawa M, Sakurai K, Shimizu M, Matsuo S, et al. Vitamin D3 modulates the expression of bile acid regulatory genes and represses inflammation in bile duct-ligated mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2009;328:564–570. doi: 10.1124/jpet.108.145987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schmidt DR, Holmstrom SR, Fon Tacer K, Bookout AL, Kliewer SA, Mangelsdorf DJ. Regulation of bile acid synthesis by fat-soluble vitamins A and D. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:14486–14494. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.116004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vogel A, Strassburg CP, Manns MP. Genetic association of vitamin D receptor polymorphisms with primary biliary cirrhosis and autoimmune hepatitis. Hepatology. 2002;35:126–131. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.30084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li YC, Pirro AE, Amling M, Delling G, Baron R, Bronson R, et al. Targeted ablation of the vitamin D receptor: an animal model of vitamin D-dependent rickets type II with alopecia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:9831–9835. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.18.9831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li YC, Amling M, Pirro AE, Priemel M, Meuse J, Baron R, et al. Normalization of mineral ion homeostasis by dietary means prevents hyperparathyroidism, rickets, and osteomalacia, but not alopecia in vitamin D receptor-ablated mice. Endocrinology. 1998;139:4391–4396. doi: 10.1210/endo.139.10.6262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Knuth A, Gabbert H, Dippold W, Klein O, Sachsse W, Bitter-Suermann D, et al. Biliary adenocarcinoma. Characterisation of three new human tumor cell lines. J Hepatol. 1985;1:579–596. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(85)80002-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Debray D, Rainteau D, Barbu V, Rouahi M, El Mourabit H, Lerondel S, et al. Defects in gallbladder emptying and bile Acid homeostasis in mice with cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator deficiencies. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:1581–1591. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.02.033. e1586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Trauner M, Boyer JL. Bile salt transporters: molecular characterization, function, and regulation. Physiol Rev. 2003;83:633–671. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00027.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zollner G, Fickert P, Silbert D, Fuchsbichler A, Marschall HU, Zatloukal K, et al. Adaptive changes in hepatobiliary transporter expression in primary biliary cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2003;38:717–727. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(03)00096-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marschall HU, Wagner M, Bodin K, Zollner G, Fickert P, Gumhold J, et al. Fxr(-/-) mice adapt to biliary obstruction by enhanced phase I detoxification and renal elimination of bile acids. J Lipid Res. 2006;47:582–592. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M500427-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alvaro D, Mancino MG. New insights on the molecular and cell biology of human cholangiopathies. Mol Aspects Med. 2008;29:50–57. doi: 10.1016/j.mam.2007.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kinnman N, Housset C. Peribiliary myofibroblasts in biliary type liver fibrosis. Front Biosci. 2002;7:d496–d503. doi: 10.2741/A790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rahner C, Stieger B, Landmann L. Structure-function correlation of tight junctional impairment after intrahepatic and extrahepatic cholestasis in rat liver. Gastroenterology. 1996;110:1564–1578. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v110.pm8613064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wagner M, Fickert P, Zollner G, Fuchsbichler A, Silbert D, Tsybrovskyy O, et al. Role of farnesoid X receptor in determining hepatic ABC transporter expression and liver injury in bile duct-ligated mice. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:825–838. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)01068-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vallorosi CJ, Day KC, Zhao X, Rashid MG, Rubin MA, Johnson KR, et al. Truncation of the beta-catenin binding domain of E-cadherin precedes epithelial apoptosis during prostate and mammary involution. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:3328–3334. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.5.3328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rios-Doria J, Day KC, Kuefer R, Rashid MG, Chinnaiyan AM, Rubin MA, et al. The role of calpain in the proteolytic cleavage of E-cadherin in prostate and mammary epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:1372–1379. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208772200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Melloni E, Michetti M, Salamino F, Minafra R, Pontremoli S. Modulation of the calpain autoproteolysis by calpastatin and phospholipids. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;229:193–197. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.1779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Glading A, Chang P, Lauffenburger DA, Wells A. Epidermal growth factor receptor activation of calpain is required for fibroblast motility and occurs via an ERK/MAP kinase signaling pathway. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:2390–2398. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.4.2390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cordero JB, Cozzolino M, Lu Y, Vidal M, Slatopolsky E, Stahl PD, et al. 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D down-regulates cell membrane growth- and nuclear growth-promoting signals by the epidermal growth factor receptor. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:38965–38971. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M203736200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McGaffin KR, Chrysogelos SA. Identification and characterization of a response element in the EGFR promoter that mediates transcriptional repression by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 in breast cancer cells. J Mol Endocrinol. 2005;35:117–133. doi: 10.1677/jme.1.01813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alvaro D, Mancino MG, Glaser S, Gaudio E, Marzioni M, Francis H, et al. Proliferating cholangiocytes: a neuroendocrine compartment in the diseased liver. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:415–431. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.07.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Beaussier M, Wendum D, Fouassier L, Rey C, Barbu V, Lasnier E, et al. Adaptative bile duct proliferative response in experimental bile duct ischemia. J Hepatol. 2005;42:257–265. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2004.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Limaye PB, Apte UM, Shankar K, Bucci TJ, Warbritton A, Mehendale HM. Calpain released from dying hepatocytes mediates progression of acute liver injury induced by model hepatotoxicants. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2003;191:211–226. doi: 10.1016/s0041-008x(03)00250-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Naderi N, Farnood A, Habibi M, Derakhshan F, Balaii H, Motahari Z, et al. Association of vitamin D receptor gene polymorphisms in Iranian patients with inflammatory bowel disease. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:1816–1822. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2008.05525.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Simmons JD, Mullighan C, Welsh KI, Jewell DP. Vitamin D receptor gene polymorphism: association with Crohn's disease susceptibility. Gut. 2000;47:211–214. doi: 10.1136/gut.47.2.211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pollheimer MJ, Halilbasic E, Fickert P, Trauner M. Pathogenesis of primary sclerosing cholangitis. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2011;25:727–739. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2011.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Karrar A, Broome U, Sodergren T, Jaksch M, Bergquist A, Bjornstedt M, et al. Biliary epithelial cell antibodies link adaptive and innate immune responses in primary sclerosing cholangitis. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:1504–1514. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.01.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Seki E, De Minicis S, Osterreicher CH, Kluwe J, Osawa Y, Brenner DA, et al. TLR4 enhances TGF-beta signaling and hepatic fibrosis. Nat Med. 2007;13:1324–1332. doi: 10.1038/nm1663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sheth P, Delos Santos N, Seth A, LaRusso NF, Rao RK. Lipopolysaccharide disrupts tight junctions in cholangiocyte monolayers by a c-Src-, TLR4-, and LBP-dependent mechanism. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2007;293:G308–318. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00582.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fickert P, Fuchsbichler A, Wagner M, Zollner G, Kaser A, Tilg H, et al. Regurgitation of bile acids from leaky bile ducts causes sclerosing cholangitis in Mdr2 (Abcb4) knockout mice. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:261–274. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional Supporting Information may be found in the online version of this article.