Abstract

The fitness effects of symbionts on their hosts can be context-dependent, with usually benign symbionts causing detrimental effects when their hosts are stressed, or typically parasitic symbionts providing protection towards their hosts (e.g. against pathogen infection). Here, we studied the novel association between the invasive garden ant Lasius neglectus and its fungal ectosymbiont Laboulbenia formicarum for potential costs and benefits. We tested ants with different Laboulbenia levels for their survival and immunity under resource limitation and exposure to the obligate killing entomopathogen Metarhizium brunneum. While survival of L. neglectus workers under starvation was significantly decreased with increasing Laboulbenia levels, host survival under Metarhizium exposure increased with higher levels of the ectosymbiont, suggesting a symbiont-mediated anti-pathogen protection, which seems to be driven mechanistically by both improved sanitary behaviours and an upregulated immune system. Ants with high Laboulbenia levels showed significantly longer self-grooming and elevated expression of immune genes relevant for wound repair and antifungal responses (β-1,3-glucan binding protein, Prophenoloxidase), compared with ants carrying low Laboulbenia levels. This suggests that the ectosymbiont Laboulbenia formicarum weakens its ant host by either direct resource exploitation or the costs of an upregulated behavioural and immunological response, which, however, provides a prophylactic protection upon later exposure to pathogens.

Keywords: symbiosis, host–parasite interactions, grooming behaviour, immune gene expression, Laboulbenia formicarum, Metarhizium brunneum

1. Introduction

Host–symbiont interactions are common in nature and comprise long-term associations that range from mutualism (mutual benefit) to parasitism (exploitation of the host by the symbiont) [1,2]. The fitness consequences for the two partners of a symbiosis are not necessarily fixed, but may vary over time or in response to environmental conditions. Such context-dependent changes in the strength and even direction of symbiotic interactions [3–5] mean that symbionts clearly assigned to the parasitic end of the symbiosis continuum may also be able to provide some positive effects for their hosts, at least temporarily, or under particular environmental conditions [6,7]. For instance, numerous cases have been described where associations with certain endoparasites [8], viruses [9] and bacteria [10,11]—including the intracellular bacterium Wolbachia [12–14]—may protect their hosts from infection by various types of pathogens, such as viruses [12,13], bacteria [8–10], protozoa [13] and pathogenic fungi [11,14]. Social insects, especially ants, interact with a wide range of different symbiotic organisms, including mutualisms with food- and shelter-providing plants [15], sap-feeding insects like aphids [16] and intracellular bacteria [17], as well as even antibiotic-producing bacteria (fungus growing ants [18]). In addition to these mutualistic associations, ants suffer infection from a diverse range of micro- and macroparasites [19], against which they have evolved elaborate disease defences, at both the individual [20,21] and group levels (reviewed in [22]).

Lately, a novel association has been established in several populations of the invasive garden ant Lasius neglectus [23,24] with the ectosymbiotic fungus Laboulbenia formicarum [25,26]. Both species were recently introduced to Central Europe—the host L. neglectus probably originates from Asia Minor [27–29], whereas the symbiont Laboulbenia originates from North America, where it has a host range of various native ant species [25]. Reports of Laboulbenia exist for only a minority of L. neglectus populations (four out of more than 160 [25]), but where Laboulbenia is present, it has quickly spread throughout the population within a few years of its introduction (reaching 100% prevalence in Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer, L'Escala and Gif-Sur-Yvette, while Douarnenez shows a more complex multipartite association [25]; S.T. & M.K. 2012, personal observation). Fungi of the order Laboulbeniales attach to the integument of their arthropod host, where they produce small fruiting bodies (thalli) [30] that can cover a great percentage of the host's cuticle (figure 1). Even though little is known about their exact interactions with their hosts and subsequent fitness consequences [31,32], they are described as obligate ectoparasites that require a living host for survival, from which they exploit resources for their own growth and reproduction [33], either via absorption through pores in their host's integument or through active penetration [30,31]. It is thus intriguing how L. neglectus populations with Laboulbenia have managed to persist and successfully compete against native species, as, based on current knowledge, Laboulbenia is expected to compromise host fitness.

Figure 1.

Images of Laboulbenia-carrying Lasius neglectus workers. Electron microscopy images depicting (a) the head of a L. neglectus worker covered with several thalli of Laboulbenia formicarum and (b) close-up of a thallus attached to the eye of its ant host. Images of a L. neglectus worker with (c) a low Laboulbenia level (1–75 thalli) compared with (d) a high Laboulbenia level (more than 150 thalli).

We therefore set out an experimental study to investigate the host fitness consequences of this novel host–symbiont association. We expected to find the host ants paying a fitness cost, similar to reports for other Laboulbeniales associations [34–36], particularly when carrying high levels of Laboulbenia and when experiencing resource limitation conditions, where the host may not be able to compensate for any loss of resources exploited by the ectosymbiont. So far, no benefits for hosts associated with Laboulbeniales have been reported; however, Laboulbeniales members require living hosts for their own survival and reproduction, as transmission mainly occurs via interactions between live cohabitants, rather than via contaminated soil [37,38]. Laboulbeniales might therefore have evolved direct or indirect means to protect their hosts from threats to the life of their hosts, such as highly virulent insect pathogens like obligate killing entomopathogenic fungi, as host death would invariably also kill the attached Laboulbeniales. Entomopathogenic fungi of the genus Metarhizium are common soil-borne insect pathogens with a broad host range (generalists [39]) and a worldwide distribution [40], so that it is highly likely that they coexist in most host populations associated with the highly host-specific Laboulbeniales [41]. Both fungi need to adhere to the host cuticle before penetration of the integument. Sanitary actions by the ants (such as self-grooming) may therefore be an effective first-level defence against Laboulbeniales and Metarhizium due to mechanical removal and chemical inactivation [42–44]. Both fungi then penetrate the insect cuticle by physical pressure and production of histolytic enzymes [45,46]. Laboulbeniales usually forms a large haustorial bulb within or close to the host's integument [30], whereas Metarhizium produces small single-cell blastospores swamping the host's haemocoel [46]. Thus, even though both fungi cause wounding to the host, we would expect different host immune components to predominate. While Laboulbeniales may mainly induce pathways for encapsulating large non-self objects (e.g. the Phenoloxidase cascade), Metarhizium may also elicit more specific antimicrobial peptide (AMP) production. Importantly, upregulated immune defences due to an association with Laboulbeniales might impede the establishment of entomopathogenic infections and thus indirectly benefit the Laboulbeniales fungi.

To test for potential costs and benefits of this novel association of L. neglectus ants with Laboulbenia formicarum, we studied the ants’ survival under food restriction and after exposure to the entomopathogen Metarhizium brunneum, as well as their sanitary behaviour, and constitutive and induced immune components.

2. Material and methods

(a). Collection of Laboulbenia-carrying ants

Foraging workers of the unicolonial, invasive ant species L. neglectus [23] were sampled in 2012 from the supercolony in Saintes-Maries-de-la-Mer, France, which has a described association with Laboulbenia formicarum [25]. By using only foragers, we aimed at reducing the variation in our sample by focusing on the older worker class (based on age polyethism [47]). The Laboulbenia level (number of thalli; figure 1) was determined for each ant at 30× magnification under a stereomicroscope, while the ants were cold-anaesthetized. Laboulbenia prevalence had reached 100% in 2012 (from 28.8% reported in 2009 [25]), with ants carrying from a minimum of one thallus up to a maximum of 421 thalli on their bodies. Ants used in the experiments were kept in individual Petri dishes (diameter 3.5 cm) with a plastered base at a constant temperature of 23°C, 75% relative humidity and 14 L : 10 D cycle. Ants were fed with 10% sucrose solution ad libitum (except in the starvation treatment, where only water was provided).

(b). Exposure to the fungal pathogen Metarhizium

We exposed individual L. neglectus workers to a LD 50 dose of the entomopathogenic fungus M. brunneum (strain Ma 275, KVL 03–143; see [48] for details), by applying 0.3 µl of a 109 conidiospores ml−1 suspension in sterile 0.05% Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich), which had a germination rate of more than 95% (confirmed 24 h before the exposure), to their gaster (i.e. the abdominal segments posterior to the petiole). The sham control treatment consisted of an application of a 0.3 µl droplet of a 0.05% Triton X solution only.

(c). Survival analyses

We randomly chose 70 ants to measure survival under starvation conditions (i.e. access to water only) and 228 for survival after Metarhizium exposure (mean number of thalli per ant: 112; range: 1–421; no significant difference in thalli number between the ants used in these two treatments; t-test: t = 0.262, d.f. = 296, p = 0.794). Survival of the ants was monitored daily for two weeks. To confirm deaths caused by Metarhizium, ant corpses were surface sterilized [49] and monitored under humid conditions for three weeks. Out of the 129 dying ants, 91.5% (118) showed outgrowth of Metarhizium conidiospores, confirming an internal infection with the pathogen.

(d). Behavioural observations

To determine potential differences in behaviour of ants carrying few versus many Laboulbenia thalli, we analysed the behaviour of 29 low-level (L: 1–75 thalli) and 27 high-level (H: more than 150 thalli) Laboulbenia-carrying ants (figure 1c,d, respectively), after subjecting them to (i) no treatment (n = 10 L, 7 H), (ii) a sham control treatment (9 L, 10 H) or (iii) Metarhizium exposure (10 L, 10 H). Individual ants were filmed for 3 h after a 15 min acclimatization phase following treatment (camera Di-Li 970-O; software Debut video capture v. 1.64). Videos (total 168 h) were analysed using the software Biologic (http://www.sourceforge.net/projects/biologic/), to record the start and end time point for each behaviour. We then calculated the total duration of self-grooming and non-sanitary activity of the ants (i.e. time neither self-grooming nor resting out of total observation time).

(e). Gene expression

We analysed the expression levels of the four insect immune genes β-1,3-glucan binding protein (β-1,3-GBP), Prophenoloxidase (PPO), Hymenoptaecin (Hym) and Defensin 1 (Def1), and the reference gene 28S Ribosomal Protein S18a (RP S18a), by real-time qPCR for 31 low-level and 28 high-level Laboulbenia-carrying ants (as defined above), 2 days after (i) no treatment (n = 11 L, 8 H), (ii) a sham control treatment (9 L, 10 H) or (iii) Metarhizium exposure (11 L, 10 H). Sample preparation and gene expression analyses were performed as detailed in [50] and the electronic supplementary material. Expression levels of the immune genes were normalized to the reference gene before further statistical analysis.

(f). Survival tests

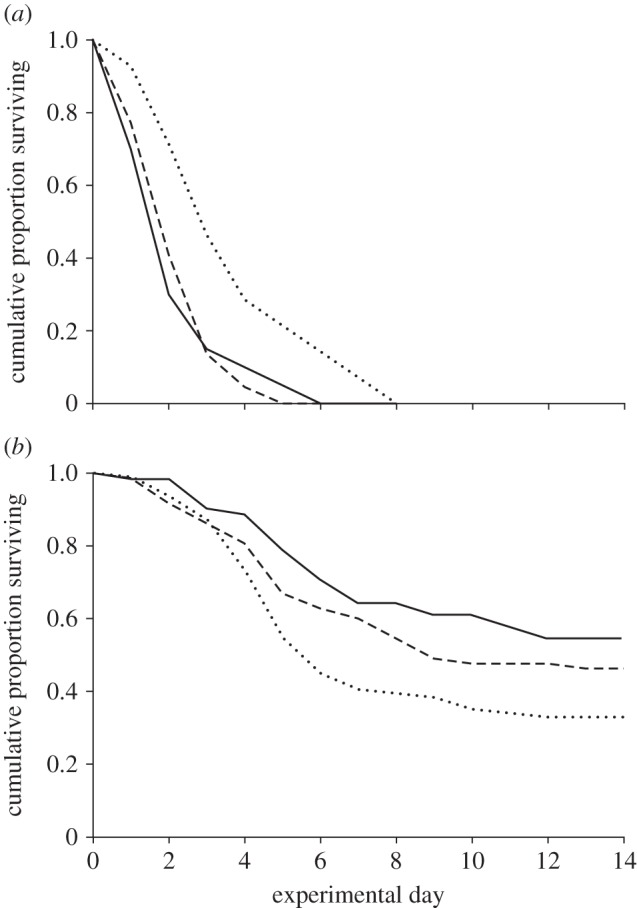

All statistical analyses were carried out in the program R v. 3.0.2 [51]. Survival data were analysed using Cox proportional regressions with ‘number of thalli’ as continuous and ‘treatment’ (starvation versus Metarhizium exposure) as categorical predictor. As we found a significant interaction between the main effects, which compromises their interpretation [52,53], we subsequently ran separate regressions for both treatments and adjusted the p-values by Holm's sequential Bonferroni procedure. For clarity of display, survival curves in figure 2 are grouped into three Laboulbenia levels (low: 1–75; medium: 76–150; high: more than 150 thalli).

Figure 2.

Survival of Laboulbenia-carrying ants under resource restriction and Metarhizium exposure. (a) Under starvation conditions, L. neglectus workers lived longer the lower the number of Laboulbenia formicarum thalli on their cuticles, whereas (b) after exposure with the entomopathogenic fungus M. brunneum, ants survived better the higher their thalli number. While statistics used the number of thalli as continuous predictor, visual representation separates survival curves of ants with low (1–75 thalli; dotted lines), medium (76–150 thalli; dashed lines) and high (more than 150 thalli; solid lines) levels of Laboulbenia.

General linear models (GLMs; with Gaussian errors structure) were run for behavioural and gene expression data, with ‘Laboulbenia level’ (low and high) and ‘treatment’ (no treatment, sham control and Metarhizium exposure) as categorical predictors. We further performed pairwise Pearson correlations to test for correlated immune gene expression and adjusted the p-values by Holm's sequential Bonferroni procedure. For further details on the statistical methods, see the electronic supplementary material.

3. Results

(a). Survival under starvation and Metarhizium exposure

Laboulbenia level had opposing effects on ant survival under starvation conditions and Metarhizium exposure, as revealed by a significant interaction between the two treatments (Cox proportional regression; overall model: LR χ2 = 126.90, d.f. = 3, p < 0.001; interaction [Laboulbenia level × treatment]: LR χ2 = 10.31, d.f. = 1, p = 0.001). Under starvation conditions, ants died significantly faster the higher the number of Laboulbenia thalli on their cuticles (LR χ2 = 5.23, d.f. = 1, p = 0.044; figure 2a), whereas survival of ants after exposure with Metarhizium was longer the higher their numbers of Laboulbenia thalli (LR χ2 = 4.46, d.f. = 1, p = 0.035; figure 2b). Under starvation, the risk of dying was increased by an estimated 3.2% per 10 Laboulbenia thalli, whereas it was decreased by an estimated 2.3% per 10 thalli after Metarhizium exposure.

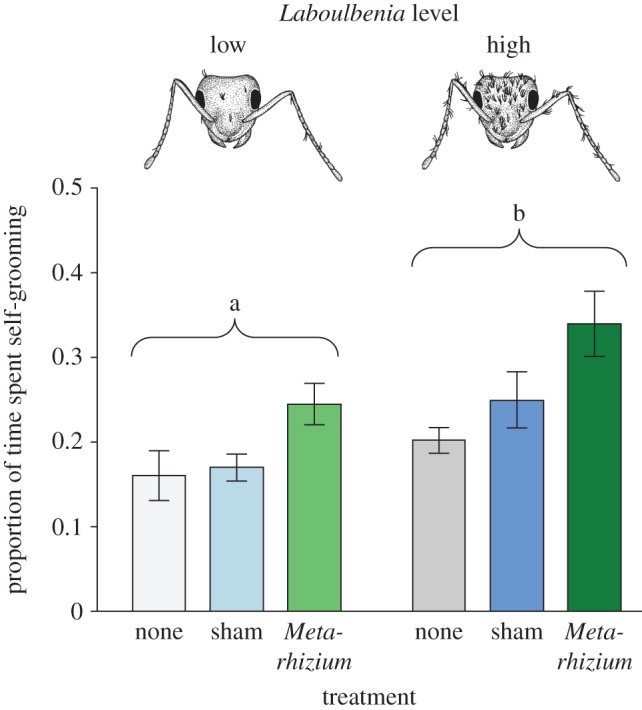

(b). Self-grooming behaviour

Self-grooming behaviour was performed for shorter time-spans by ants with low (1–75 thalli) rather than high (more than 150 thalli) levels of Laboulbenia (GLM; F = 4.747, d.f. = 5, p = 0.001; Laboulbenia level [low versus high]: F = 9.054, d.f. = 1, p = 0.004; figure 3). Moreover, ants carrying both low and high levels of Laboulbenia upregulated self-grooming behaviour when exposed to the pathogenic fungus Metarhizium (F = 7.161, d.f. = 2, p = 0.002), as compared with untreated ants (pairwise post hoc comparisons; Metarhizium versus untreated: p < 0.001) and sham control-treated individuals (Metarhizium versus sham: p = 0.010), which did not differ from each other (untreated versus sham: p = 0.326). Ants with low and high levels of Laboulbenia reacted equally to the treatment (no treatment, sham control and Metarhizium exposure), as indicated by a non-significant interaction between the two (Laboulbenia level × treatment: F = 0.015, d.f. = 2, p = 0.985). The non-sanitary activity of the ants was affected by neither Laboulbenia level nor treatment (GLM; F = 0.830, d.f. = 5, p = 0.535).

Figure 3.

Self-grooming behaviour of Laboulbenia-carrying ants. Lasius neglectus workers carrying high Laboulbenia levels (more than 150 thalli; dark colours) performed significantly longer self-grooming than individuals with low levels (1–75 thalli; pale colours). In addition, ants significantly increased their self-grooming performance after exposure with the entomopathogenic fungus M. brunneum (green), compared with both untreated (grey) and sham-treated (blue) individuals. Bars show mean ± s.e.m. Different letters indicate statistically significant differences between low and high Laboulbenia levels at α = 0.05 (significance groups of additional significant differences between treatments [Metarhizium exposure > sham/no treatment] not displayed).

(c). Immune gene expression

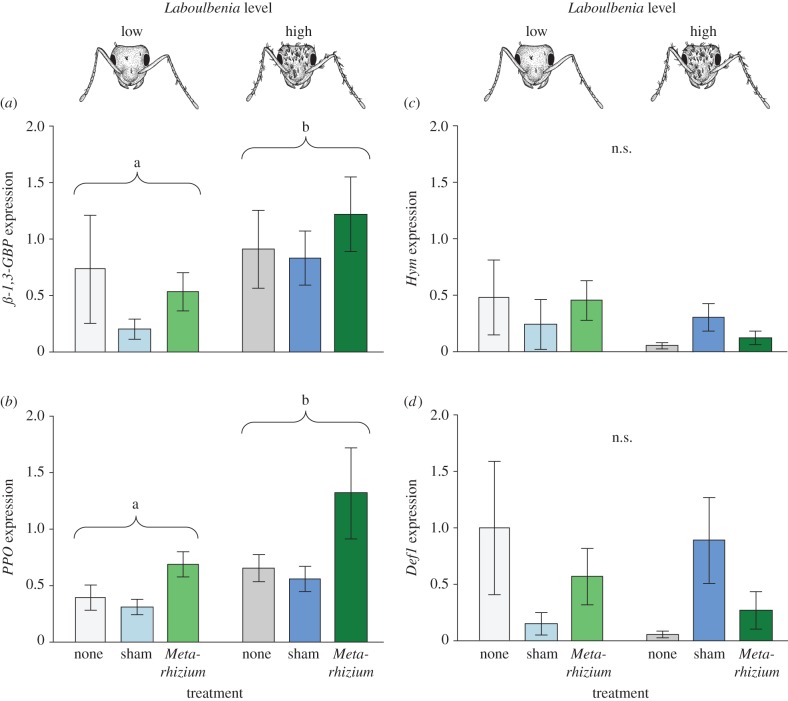

(i). β-1,3-glucan binding protein

Expression levels of the recognition molecule β-1,3-GBP were generally higher in ants carrying high Laboulbenia levels compared with individuals with low levels (GLM; F = 2.457, d.f. = 5, p = 0.045; Laboulbenia level [low versus high]: F = 8.584, d.f. = 1, p = 0.005; figure 4a). Treatment of the ants (no treatment, sham control or Metarhizium exposure) did not affect β-1,3-GBP expression (F = 1.814, d.f. = 2, p = 0.173), nor was there a significant interaction between Laboulbenia level and treatment (F = 0.387, d.f. = 2, p = 0.681).

Figure 4.

Immune gene expression of Laboulbenia-carrying ants. Expression of the immune genes (a) β-1,3-glucan binding protein (ß-1,3-GBP), (b) Prophenoloxidase (PPO), (c) Hymenoptaecin (Hym) and (d) Defensin 1 (Def1), normalized to the reference gene 28S RP S18a in L. neglectus workers. Expression levels of ß-1,3-GBP and PPO were significantly higher in ants carrying high (more than 150 thalli; dark colours) rather than low levels (1–75 thalli; pale colours) of Laboulbenia. Exposure with the entomopathogenic fungus M. brunneum (green) significantly increased the ants’ expression levels of PPO compared with untreated (grey) and sham-treated ants (blue), whereas ß-1,3-GBP expression was unaffected by treatment. Gene expression of Hym and Def1 were unaffected by both Laboulbenia level and treatment. Bars depict mean ± s.e.m. Different letters indicate statistically significant differences between ants with low and high Laboulbenia levels at α = 0.05 (significance groups of additional significant differences between treatments for PPO [Metarhizium exposure > sham/no treatment] not displayed); n.s. = non-significant.

(ii). Prophenoloxidase

Individuals carrying high levels of Laboulbenia also showed higher expression of the melanization cascade-regulating gene PPO than individuals with low levels (GLM; F = 3.313, d.f. = 5, p = 0.011; Laboulbenia level [low versus high]: F = 7.972, d.f. = 1, p = 0.007; figure 4b). PPO expression was also upregulated in ants exposed to the pathogenic fungus Metarhizium (F = 4.039, d.f. = 2, p = 0.023), as compared with completely untreated ants (pairwise post hoc comparisons; p = 0.022), as well as compared with sham control-treated individuals (p = 0.015), which did not differ from each other (untreated versus sham: p = 0.891). Ants carrying low or high levels of Laboulbenia reacted equally to the treatment, as shown by a non-significant interaction between Laboulbenia level and treatment (F = 0.414, d.f. = 2, p = 0.663).

(iii). Hymenoptaecin and Defensin 1

Laboulbenia level (low, high) and treatment (no treatment, sham control or Metarhizium exposure) had no significant effect on the gene expression of the two AMPs Hym and Def1 (GLM; Hym: F = 0.962, d.f. = 5, p = 0.450; Def1: F = 1.423, d.f. = 5, p = 0.231).

(iv). Correlations between immune genes

We found the expression of the receptor β-1,3-GBP and the melanization cascade-regulating gene PPO to be significantly positively correlated (Pearson correlation: r = 0.458, p = 0.002; figure 4a,b), with the two genes sharing 21% of their variation. The two AMPs Hym and Def1 even shared 48% of their variation (r = 0.694, p < 0.001; figure 4c,d). Moreover, β-1,3-GBP and Def1 shared 12% of their variation (r = 0.348, p = 0.028; figure 4a,d), while all other correlations were non-significant (p > 0.05).

4. Discussion

(a). Context-dependent costs and benefits of a high Laboulbenia level

Lasius neglectus workers with higher Laboulbenia levels suffered from increased mortality during starvation (figure 2a), suggesting that Laboulbenia draws resources from its host by (i) direct resource exploitation [33], (ii) eliciting energetically costly immune responses [54], (iii) tissue damage caused directly by the fungus or immunopathology [55], or (iv) a combination of these. A recent study on a different ant–Laboulbeniales system suggests that optimal food conditions can reduce such costs [36], as hosts might compensate for resource losses by increased food intake [56]. Different experimental conditions may therefore contribute to the described differences of host effects of Laboulbeniales—ranging from neutral effects [31,32,38] to confirmed costs such as moribund behaviour [57] and reduced longevity of the host [34,35,58] (but see [59]). To our knowledge, no study has previously reported a host benefit of Laboulbeniales, yet our data strongly suggest that increasing Laboulbenia formicarum levels provide L. neglectus with a survival benefit upon exposure to M. brunneum (figure 2b). However, as we had to rely on pre-existing, field-collected Laboulbenia levels, our study only provides correlative evidence and we cannot exclude potential confounding factors to have contributed to the observed effects. First, Laboulbenia level may correlate with host age, with older hosts expectedly having accumulated more Laboulbenia thalli [60], so that observed effects may rather reflect host age differences. As counteraction, we restricted worker age variation in our experiment by using only foragers, which typically comprise the older worker age group of the colony (age polyethism [47]). Second, field-collected workers with high Laboulbenia levels may represent the surviving ‘high-quality’ individuals. Yet, while this may explain their reduced susceptibility to Metarhizium, it is not in line with their higher mortality under starvation, revealing that ants carrying high Laboulbenia levels were not generally of better quality or condition. Our study has therefore disclosed an interesting pattern of context-dependent costs and benefits of Laboulbenia at the individual host level, which should be complemented by additional understanding at both the mechanistic level and the colony level of collective disease defences, expressed by social insects (social immunity [22]), but already challenges the traditional categorization of Laboulbenia as a mild ectoparasite [31–33].

(b). Interaction of Laboulbenia with host immunity and the pathogenic fungus Metarhizium

High Laboulbenia levels may mediate a reduced susceptibility to Metarhizium by competitive interactions between the two fungi and/or altered host behavioural and physiological defences. Fungus–fungus interactions can involve (i) indirect competition for space or host resources and (ii) direct competition through ‘chemical warfare’. An already existing coverage of the host surface by Laboulbenia (figure 1) may interfere with successful attachment of Metarhizium conidiospores, which is required for successful germination [46], due to reduced access to the host cuticle or even direct attachment on the Laboulbenia thalli. Laboulbenia may have further exploited host resources [33], which Metarhizium requires for growth, similar to resource competition being a likely mechanism for the antiviral protection conferred by several Wolbachia strains to their hosts [13,61]. Moreover, Laboulbenia may produce antimicrobial substances that inhibit Metarhizium growth, as described for endosymbiotic bacteria that protect their hosts against parasitoid infection through toxin production [62]. While such potential competitive interactions need further experimental assessment, our work already provides evidence for altered host defences. Similar to grooming alteration observed in another ant–Laboulbeniales system [36], L. neglectus workers carrying high levels of Laboulbenia performed increased self-grooming (figure 3), which might provide prophylactic protection in case of later exposure to pathogens like Metarhizium.

Moreover, ants with higher thalli numbers showed a higher and correlated immune gene expression at both the receptor (β-1,3-GBP [63]) and effector (PPO [64]) levels (figure 4a,b). β-1,3-GBP specifically binds fungal molecules and activates the Phenoloxidase cascade [65], which is important for wound healing and encapsulation of intruding pathogens [64]. As Laboulbeniales actively breaches the host integument for anchorage and often also to obtain resources from the haemocoel [30,31,33], it induces host wounding, the degree of which probably scales with thalli number. The observed increased PPO expression of ants with high Laboulbenia levels may further provide a kick-start for better fighting penetration of Metarhizium [50]. Though wounding can also trigger the expression of the AMPs Hym and Def1 [66], we found no association of Laboulbenia level and the expression of the two AMPs in our study (figure 4c,d). This deviation may arise as most studies analyse AMP production after acute wounding or pathogen infection [67,68], whereas Laboulbenia forms a chronic immune challenge. Alternatively, the host-specialist Laboulbenia formicarum [25] may have evolved ways to inhibit some host immune components. Though this is still elusive for Laboulbenia, the generalist pathogen Metarhizium, as well as some opportunistic pathogens, can interfere with the host immune system by making themselves insignificant or by producing toxins (e.g. against AMPs) [69–71]. This may also explain why Metarhizium treatment did not elicit changes in AMP production in our study (figure 4c,d), though we found further increase in PPO expression (figure 4b). We can therefore conclude that ants carrying high Laboulbenia levels seem to have stimulated behavioural and physiological host defences, probably providing prophylactic protection against later pathogenic Metarhizium infection, similar to described cases in wasps [8] and mice [9] after bacterial challenge. However, such chronically upregulated defences may imply costs and trade-offs in resource allocation for the host [56], explaining why ants with increasing Laboulbenia levels suffer higher mortality, particularly during food deprivation (figure 2a), when no resource compensation is possible.

(c). Potential effect of Laboulbenia association with an invasive ant species

The unusual biology of invasive ant hosts may shift the balance between costs and benefits of an association with Laboulbeniales, compared with native hosts. Invasive ants like L. neglectus cooperate across nests (unicoloniality [27]), allowing them to both quickly detect and dominate food sources over competing native species [72]. In addition to their extensive aphid tending [73], this makes starvation (i.e. the condition under which Laboulbenia can cause distinct survival costs; figure 2a) much less likely than in native ants, thereby probably reducing the costs of an association with Laboulbenia. At the same time, unicolonial species may profit more from a protective effect against Metarhizium infection, as (i) their reduced genetic diversity due to population founder effects, (ii) their absence of genetic population sub-structuring and (iii) the open exchange of individuals across nests puts them at a higher risk of disease transmission [74]. This may explain why Laboulbenia formicarum was found to show only intermediate prevalence levels (2–44%) in non-invasive ants in its native range [75], but has efficiently spread throughout the affected L. neglectus populations in Europe in very short time [25] (S.T. & M.K. 2012, personal observation), similar to the rapid fixation of Wolbachia in Drosophila populations in the US [76]. Laboulbenia formicarum also could not yet be detected on neighbouring native species alongside the invasive L. neglectus populations [25], although many of the 17 potential host ant species from its original range in North America are also ubiquitous in Europe and often occupy the same habitat as L. neglectus. We therefore propose that the prospective Laboulbenia-mediated protection against the common pathogen Metarhizium [40]—and potentially other pathogens—may even increase the invasive potential of both the affected L. neglectus population and its fungal ectosymbiont, Laboulbenia formicarum, similar to symbiont-mediated effects having contributed to the rapid invasion of other important pest species [77,78].

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Line V. Ugelvig for help with ant collection and statistical discussion, Xavier Espadaler for detailed information on the ant collection site, Birgit Lautenschläger for the electron microscopy images and Eva Sixt for ant drawings. We further thank Jørgen Eilenberg for the fungal strain, Meghan L. Vyleta for genetic strain characterization and immune gene primer development, Paul Schmid-Hempel for discussion, and Line V. Ugelvig, Xavier Espadaler and Christopher D. Pull for comments on the manuscript. S.C., M.K. and S.T. conceived the study; M.K. and A.V.G. performed the experiments; M.K. performed the statistical analysis; S.C. and M.K. wrote the manuscript with intense contributions of A.V.G. and S.T.; all authors approved the manuscript.

Data accessibility

All data are available in the DRYAD repository (http://dx.doi.org/10.5061/dryad.vm0vc).

Funding statement

Funding was obtained by the German Research Foundation (CR 118–2) and an ERC StG (243071) by the European Research Council (both to S.C.).

Conflict of interests

We have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Hughes DP, Pierce NE, Boomsma JJ. 2008. Social insect symbionts: evolution in homeostatic fortresses. Trends Ecol. Evol. 23, 672–677. ( 10.1016/j.tree.2008.07.011) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brownlie JC, Johnson KN. 2009. Symbiont-mediated protection in insect hosts. Trends Microbiol. 17, 348–354. ( 10.1016/j.tim.2009.05.005) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Offenberg J. 2001. Balancing between mutualism and exploitation: the symbiotic interaction between Lasius ants and aphids. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol. 49, 304–310. ( 10.1007/s002650000303) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McCreadie JW, Beard CE, Adler PH. 2005. Context-dependent symbiosis between black flies (Diptera: Simuliidae) and trichomycete fungi (Harpellales: Legeriomycetaceae). Oikos 108, 362–370. ( 10.1111/j.0030-1299.2005.13417.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bronstein JL. 1994. Conditional outcomes in mutualistic interactions. Trends Ecol. Evol. 9, 214–217. ( 10.1016/0169-5347(94)90246-1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thomas F, Poulin R, Guegan JF, Michalakis Y, Renaud F. 2000. Are there pros as well as cons to being parasitized? Parasitol. Today 16, 533–536. ( 10.1016/s0169-4758(00)01790-7) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fellous S, Salvaudon L. 2009. How can your parasites become your allies? Trends Parasitol. 25, 62–66. ( 10.1016/j.pt.2008.11.010) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Manfredini F, Beani L, Taormina M, Vannini L. 2010. Parasitic infection protects wasp larvae against a bacterial challenge. Microbes Infect. 12, 727–735. ( 10.1016/j.micinf.2010.05.001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barton ES, White DW, Cathelyn JS, Brett-McClellan KA, Engle M, Diamond MS, Miller VL, Virgin HW. 2007. Herpesvirus latency confers symbiotic protection from bacterial infection. Nature 447, U326–U327. ( 10.1038/nature05762) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Perry S, et al. 2010. Infection with Helicobacter pylori is associated with protection against tuberculosis. PLoS ONE 5, e0008804 ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0008804) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Scarborough CL, Ferrari J, Godfray HCJ. 2005. Aphid protected from pathogen by endosymbiont. Science 310, 1781 ( 10.1126/science.1120180) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hedges LM, Brownlie JC, O'Neill SL, Johnson KN. 2008. Wolbachia and virus protection in insects. Science 322, 702 ( 10.1126/science.1162418) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moreira LA, et al. 2009. A Wolbachia symbiont in Aedes aegypti limits infection with Dengue, Chikungunya, and Plasmodium. Cell 139, 1268–1278. ( 10.1016/j.cell.2009.11.042) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Panteleev DY, Goryacheva II, Andrianov BV, Reznik NL, Lazebny OE, Kulikov AM. 2007. The endosymbiotic bacterium Wolbachia enhances the nonspecific resistance to insect pathogens and alters behavior of Drosophila melanogaster. Russ. J. Genet. 43, 1066–1069. ( 10.1134/s1022795407090153) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heil M, McKey D. 2003. Protective ant–plant interactions as model systems in ecological and evolutionary research. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 34, 425–453. ( 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.34.011802.132410) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stadler B, Dixon AFG. 2005. Ecology and evolution of aphid-ant interactions. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 36, 345–372. ( 10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.36.091704.175531) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Feldhaar H, Straka J, Krischke M, Berthold K, Stoll S, Mueller MJ, Gross R. 2007. Nutritional upgrading for omnivorous carpenter ants by the endosymbiont Blochmannia. BMC Biol. 5, 48 ( 10.1186/1741-7007-5-48) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Currie CR, Scott JA, Summerbell RC, Malloch D. 1999. Fungus-growing ants use antibiotic-producing bacteria to control garden parasites. Nature 398, 701–704. ( 10.1038/19519) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schmid-Hempel P. 1998. Parasites in social insects. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rosengaus RB, Malak T, MacKintosh C. 2013. Immune-priming in ant larvae: social immunity does not undermine individual immunity. Biol Lett 9, 20130563 ( 10.1098/rsbl.2013.0563) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fernandez-Marin H, Zimmerman JK, Rehner SA, Wcislo WT. 2006. Active use of the metapleural glands by ants in controlling fungal infection. Proc. R. Soc. B 273, 1689–1695. ( 10.1098/rspb.2006.3492) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cremer S, Armitage SAO, Schmid-Hempel P. 2007. Social immunity. Curr. Biol. 17, R693–R702. ( 10.1016/j.cub.2007.06.008) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Van Loon AJ, Boomsma JJ, Andrasfalvy A. 1990. A new polygynous Lasius species (Hymenoptera; Formicidae) from central Europe. I. Description and general biology. Insectes Soc. 37, 348–362. ( 10.1007/BF02225997) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Espadaler X, Bernal V. 2013. Lasius neglectus: a polygynous, sometimes invasive, ant See http://www.creaf.uab.es/xeg/lasius/index.htm (accessed 17 January 2014).

- 25.Espadaler X, Lebas C, Wagenknecht J, Tragust S. 2011. Laboulbenia formicarum (Ascomycota, Laboulbeniales), an exotic parasitic fungus, on an exotic ant in France. Vie Milieu 61, 41–44. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Herraiz JA, Espadaler X. 2007. Laboulbenia formicarum (Ascomycota, Laboulbeniales) reaches the Mediterranean. Sociobiology 50, 449–455. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cremer S, et al. 2008. The evolution of invasiveness in garden ants. PLoS ONE 3, e0003838 ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0003838) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Seifert B. 2000. Rapid range expansion in Lasius neglectus (Hymenoptera, Formicidae)—an Asian invader swamps Europe. Dtsch Entomol. Z 47, 173–179. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ugelvig LV, Drijfhout FP, Kronauer DJC, Boomsma JJ, Pedersen JS, Cremer S. 2008. The introduction history of invasive garden ants in Europe: integrating genetic, chemical and behavioural approaches. BMC Biol. 6, 11 ( 10.1186/1741-7007-6-11) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tavares II. 1985. Laboulbeniales: (Fungi, Ascomycetes). Mycol. Mem. 9, 1–627. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Benjamin RK. 1971. Introduction and supplement to Roland Thaxter's contribution towards a monograph of the Laboulbeniaceae. Bibl. Mycol. 30, 1–155. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weir A, Beakes G. 1995. An introduction to the Laboulbeniales: a fascinating group of entomogenous fungi. Mycologist 9, 6–10. ( 10.1016/S0269-915X(09)80238-3) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Scheloske HW. 1969. Beiträge zur Biologie, Ökologie und Systematik der Laboulbeniales (Ascomycetes) unter besonderer Berücksichtigung des Parasit-Wirt-Verhältnisses. Parasitol. Schriftenr. 19, 1–176. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kamburov SS, Nadel DJ, Kenneth R. 1967. Observations on Hesperomyces virescens Thaxter (Laboulbeniales), a fungus associated with premature mortality of Chilocorus bipustulatus L in Israel. Isr. J. Agric. Res. 17, 131–136. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Riddick EW. 2010. Ectoparasitic mite and fungus on an invasive lady beetle: parasite coexistence and influence on host survival. Bull. Insectol. 63, 13–20. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Csata E, Erős K, Markó B. 2014. Effects of the ectoparasitic fungus Rickia wasmannii on its ant host Myrmica scabrinodis: changes in host mortality and behavior. Insect Soc. 61, 247–252. ( 10.1007/s00040-014-0349-3) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.De Kesel A. 1995. Relative importance of direct and indirect infection in the transmission of Laboulbenia slackensis (Ascomycetes, Laboulbeniales). Belgian J. Bot. 128, 124–130. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Whisler HC. 1968. Experimental studies with a new species of Stigmatomyces (Laboulbeniales). Mycologia 60, 65 ( 10.2307/3757314) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zimmermann G. 1993. The entomopathogenic fungus Metarhizium anisopliae and its potential as a biocontrol agent. Pest. Sci. 37, 375–379. ( 10.1002/ps.2780370410) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Roberts DW, St. Leger RJ. 2004. Metarhizium spp., cosmopolitan insect-pathogenic fungi: mycological aspects. Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 54, 1–70. ( 10.1016/S0065-2164(04)54001-7) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.DeKesel A. 1996. Host specificity and habitat preference of Laboulbenia slackensis. Mycologia 88, 565–573. ( 10.2307/3761150) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reber A, Purcell J, Buechel SD, Buri P, Chapuisat M. 2011. The expression and impact of antifungal grooming in ants. J. Evol. Biol. 24, 954–964. ( 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2011.02230.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hughes WOH, Eilenberg J, Boomsma JJ. 2002. Trade-offs in group living: transmission and disease resistance in leaf-cutting ants. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B 269, 1811–1819. ( 10.1098/rspb.2002.2113) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tragust S, Mitteregger B, Barone V, Konrad M, Ugelvig LV, Cremer S. 2013. Ants disinfect fungus-exposed brood by oral uptake and spread of their poison. Curr. Biol. 23, 76–82. ( 10.1016/j.cub.2012.11.034) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Meola S, Tavares II. 1982. Ultrastructure of the haustorium of Trenomyces histophthorus and adjacent host cells. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 40, 205–215. ( 10.1016/0022-2011(82)90117-3) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hajek AE, St. Leger RJ. 1994. Interactions between fungal pathogens and insect hosts. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 39, 293–322. ( 10.1146/annurev.en.39.010194.001453) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hölldobler B, Wilson EO. 1990. The ants. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tragust S, Ugelvig LV, Chapuisat M, Heinze J, Cremer S. 2013. Pupal cocoons affect sanitary brood care and limit fungal infections in ant colonies. BMC Evol. Biol. 13, 225 ( 10.1186/1471-2148-13-225) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lacey LA, Brooks WM. 1997. Initial handling and diagnosis of diseased insects. In Manual of techniques in insect pathology (ed. Lacey LA.), pp. 1–16. London, UK: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Konrad M, et al. 2012. Social transfer of pathogenic fungus promotes active immunisation in ant colonies. PLoS Biol. 10, e1001300 ( 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001300) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.R Development Core Team. 2013. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Underwood AJ. 1997. Experiments in ecology. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zar JH. 1999. Biostatistical analysis, 4th edn Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Schmid-Hempel P. 2003. Variation in immune defence as a question of evolutionary ecology. Proc. R Soc. Lond. B 270, 357–366. ( 10.1098/rspb.2002.2265) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sadd BM, Siva-Jothy MT. 2006. Self-harm caused by an insect's innate immunity. Proc. R. Soc. B 273, 2571–2574. ( 10.1098/rspb.2006.3574) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Moret Y, Schmid-Hempel P. 2000. Survival for immunity: the price of immune system activation for bumblebee workers. Science 290, 1166–1168. ( 10.1126/science.290.5494.1166) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gemeno C, Zurek L, Schal C. 2004. Control of Herpomyces spp. (Ascomycetes: Laboulbeniales) infection in the wood cockroach, Parcoblatta lata (Dictyoptera: Blattodea: Blattellidae), with benomyl. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 85, 132–135. ( 10.1016/j.jip.2004.01.005) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Strandberg JO, Tucker LC. 1974. Filariomyces forficulae: occurrence and effects on the predatory earwig, Labidura riparia. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 24, 357–364. ( 10.1016/0022-2011(74)90144-X) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Applebaum SW, Kfir R, Gerson U, Tadmor U. 1971. Studies on the summer decline of Chilocorus bipustulatus in Citrus groves of Israel. Entomophaga 16, 433–444. ( 10.1007/bf02370924) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.De Kesel A. 1993. Relations between host population density and spore transmission of Laboulbenia slackensis (Ascomycetes, Laboulbeniales) from Pogonus chalceus (Coleoptera, Carabidae). Belgian J. Bot. 126, 155–163. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Caragata EP, Rances E, Hedges LM, Gofton AW, Johnson KN, O'Neill SL, McGraw EA. 2013. Dietary cholesterol modulates pathogen blocking by Wolbachia. PLoS Pathog. 9, e1003459 ( 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003459) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Moran NA, Degnan PH, Santos SR, Dunbar HE, Ochman H. 2005. The players in a mutualistic symbiosis: insects, bacteria, viruses, and virulence genes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 102, 16 919–16 926. ( 10.1073/pnas.0507029102) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yek SH, Boomsma JJ, Schiøtt M. 2013. Differential gene expression in Acromyrmex leaf-cutting ants after challenges with two fungal pathogens. Mol. Ecol. 22, 2173–2187. ( 10.1111/mec.12255) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cerenius L, Söderhäll K. 2004. The prophenoloxidase-activating system in invertebrates. Immunol. Rev. 198, 116–126. ( 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2004.00116.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jiang H, Ma C, Lu Z-Q, Kanost MR. 2004. β-1,3-Glucan recognition protein-2 (βGRP-2) from Manduca sexta: an acute-phase protein that binds β-1,3-glucan and lipoteichoic acid to aggregate fungi and bacteria and stimulate prophenoloxidase activation. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 34, 89–100. ( 10.1016/j.ibmb.2003.09.006) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Erler S, Popp M, Lattorff HMG. 2011. Dynamics of immune system gene expression upon bacterial challenge and wounding in a social insect (Bombus terrestris). PLoS ONE 6, e0018126 ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0018126) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Korner P, Schmid-Hempel P. 2004. In vivo dynamics of an immune response in the bumble bee Bombus terrestris. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 87, 59–66. ( 10.1016/j.jip.2004.07.004) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Haine ER, Pollitt LC, Moret Y, Siva-Jothy MT, Rolff J. 2008. Temporal patterns in immune responses to a range of microbial insults (Tenebrio molitor). J. Insect Physiol. 54, 1090–1097. ( 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2008.04.013) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wang C, Leger RJS. 2006. A collagenous protective coat enables Metarhizium anisopliae to evade insect immune responses. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 103, 6647–6652. ( 10.1073/pnas.0601951103) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Huxham IM, Lackie AM, McCorkindale NJ. 1989. Inhibitory effects of cyclodepsipeptides, destruxins, from the fungus Metarhizium anisopliae, on cellular immunity in insects. J. Insect Physiol. 35, 97–105. ( 10.1016/0022-1910(89)90042-5) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Apidianakis Y, Mindrinos MN, Xiao WZ, Lau GW, Baldini RL, Davis RW, Rahme LG. 2005. Profiling early infection responses: Pseudomonas aeruginosa eludes host defenses by suppressing antimicrobial peptide gene expression. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 102, 2573–2578. ( 10.1073/pnas.0409588102) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Feener DJ. 2000. Is the assembly of ant communities mediated by parasitoids? Oikos 90, 79–88. ( 10.1034/j.1600-0706.2000.900108.x) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Paris CI, Espadaler X. 2009. Honeydew collection by the invasive garden ant Lasius neglectus versus the native ant L. grandis . Arthropod. Plant Interact. 3, 75–85. ( 10.1007/s11829-009-9057-8) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ugelvig LV, Cremer S. 2012. Effects of social immunity and unicoloniality on host–parasite interactions in invasive insect societies. Funct. Ecol. 26, 1300–1312. ( 10.1111/1365-2435.12013) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Nuhn TP, Vandyke CG. 1979. Laboulbenia formicarum Thaxter (Ascomycotina, Laboulbeniales) on ants (Hymenoptera, Formicidae) in Raleigh, North Carolina with a new host record. Proc. Entomol. Soc. Wash. 81, 101–104. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Turelli M, Hoffmann AA. 1991. Rapid spread of an inherited incompatibility factor in California Drosophila. Nature 353, 440–442. ( 10.1038/353440a0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Himler AG, et al. 2011. Rapid spread of a bacterial symbiont in an invasive whitefly is driven by fitness benefits and female bias. Science 332, 254–256. ( 10.1126/science.1199410) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hansen AK, Jeong G, Paine TD, Stouthamer R. 2007. Frequency of secondary symbiont infection in an invasive psyllid relates to parasitism pressure on a geographic scale in California. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73, 7531–7535. ( 10.1128/aem.01672-07) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data are available in the DRYAD repository (http://dx.doi.org/10.5061/dryad.vm0vc).