Abstract

A series of chiral cyclometalated platinum(II) complexes, [Pt((−)-L1)(Dmpi)]Cl ((−)-1), [Pt((+)-L1)(Dmpi)]Cl ((+)-1), [Pt((−)-L2)(Dmpi)]Cl ((−)-2), [Pt((+)-L2)(Dmpi)]Cl ((+)-2), [Pt3((−)-L2)2(Dmpi)4](ClO4)4 ((−)-3), and [Pt3((+)-L2)2(Dmpi)4](ClO4)4 ((+)-3) [(−)-L1 = (−)-4,5-pinene-6′-phenyl-2,2′-bipyridine, (+)-L1 = (+)-4,5-pinene-6′-phenyl-2,2′-bipyridine), (−)-L2 = (−)-1,3-bis(2-(4,5-pinene)pyridyl)benzene, (+)-L2 = (+)-1,3-bis(2-(4,5-pinene)pyridyl)benzene, Dmpi = 2,6-dimethylphenyl isocyanide], have been designed and synthesized. In aqueous solutions, (−)-1 and (+)-1 aggregate into one-dimensional helical chain structures through Pt···Pt, π–π, and hydrophobic–hydrophobic interactions. (−)-3 and (+)-3 represent a novel helical structure with Pt–Pt bonds. The formation of helical structures results in enhanced and distinct chiroptical properties as evidenced by circular dichroism spectra. Circularly polarized luminescence (CPL) was observed from the aggregates of (−)-1 and (+)-1 in water, as well as (−)-3 and (+)-3 in dichloromethane. The CPL activity can be switched reversibly (for (−)-1 and (+)-1) or irreversibly (for (−)-3 and (+)-3) by varying the temperature.

Short abstract

A series of chiral cyclometalated platinum(II) complexes have been synthesized and characterized. These complexes show enhanced and distinct chiroptial properties due to intermolecular helical packing and an intramolecular helical structure, leading to tunable electronic circular dichroism and circularly polarized luminescence.

Introduction

Circularly polarized luminescence (CPL) spectroscopy is the counterpart of circular dichroism (CD) in the characterization of emission.1 While CD spectroscopy has been widely used to investigate structural properties of the ground electronic states of a system, CPL has been proven to be powerful in studying the structural properties of the luminescent excited states. In some applications, CPL provides additional information concerning molecular dynamics and energetics by probing processes that occur between the excitation event and the emission.2 In spite of the fact that there are still many unresolved issues regarding the measurement and theoretical characterization, it is widely believed that CPL has great potential for the monitoring of chiral environments due to its high sensitivity and specificity.3 Moreover, CPL also has potential applications in photonic devices, such as light-emitting diodes, optical amplifiers, and optical information storage.4

So far, the research field of CPL has been dominated by chiral lanthanide complexes.5 The intraconfigurational f ↔ f transitions from lanthanide metal ions, particularly those that obey magnetic dipole selection rules (J = 0 ± 1, except 0 ↔ 0), generally have large luminescence dissymmetry factors, glum(λ),6 which facilitate the detection of the CPL signal.1c However, in recent years, there has been a growing interest in developing new CPL-active materials based on organic molecules or transition-metal complexes.7,8 Various strategies have been used to create CPL-emitting organic materials, including attaching chiral side chains to conjugated polymers, embedding organic chromophores in a chiral matrix, and developing inherently chiral conjugated molecules. The pinene group, a naturally occurring chiral element, is frequently introduced into pyridine ligands, leading to novel helical configurations and interesting circularly polarized luminescence.9

CPL switches based on supramolecular systems are particularly interesting because CPL emission can be turned “‘on’” and “‘off’” by an external stimulus, including anion or ion pairing, temperature, solvent polarity, concentration, light irradiation, and mechanical stirring.10 Maeda et al. demonstrated that conformation changes by inversion (flipping) of two pyrrole rings as a result of anion binding can control the chiroptical properties of the anion receptors.10a Okano et al. showed that hydrogels with embedded Rhodamine B dye exhibited stir-induced circularly polarized luminescence, the sense of which can be controlled by switching the stir direction from clockwise (CW) to counterclockwise (CCW) with slow cooling from the sol to gel states.10b These CPL switches may have potential applications for advanced chiroptical materials, such as chiroptical memory, light-emitting devices, and multifunctional sensors.11

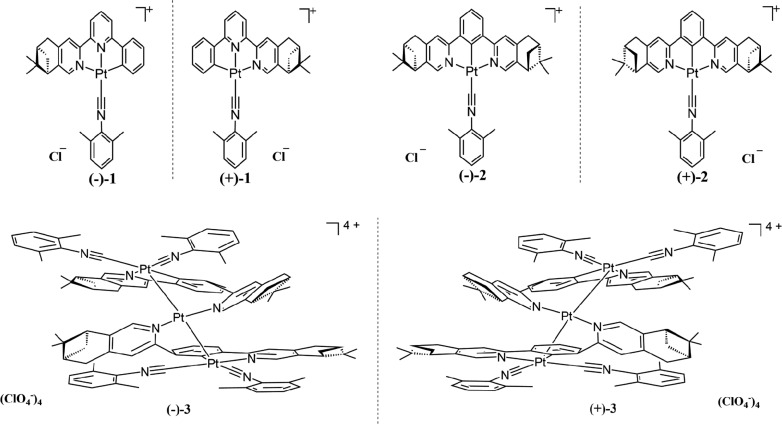

Cyclometalated platinum(II) complexes have long been the subject of intense investigation as luminescent materials due to their intriguing stimulus-responsive structural and spectroscopic properties.12−15 Moreover, cyclometalated platinum(II) complexes have been proven to be biologically active as antitumor agents and DNA intercalators.16 Therefore, cyclometalated platinum(II) complexes with CPL emission would be very useful in organic light-emitting diodes (OLEDs) and chiral probes in biological systems. However, CPL emission from platinum(II) complexes has seldom been reported before,8b mainly due to the weak chirality of the distorted square planar coordination configuration of platinum(II) ion. In this work, we designed and synthesized a series of chiral cyclometalated platinum(II) complexes, namely, [Pt((−)-L1)(Dmpi)]Cl ((−)-1), [Pt((+)-L1)(Dmpi)]Cl ((+)-1), [Pt((−)-L2)(Dmpi)]Cl ((−)-2), [Pt((+)-L2)(Dmpi)]Cl ((+)-2), [Pt3((−)-L2)2(Dmpi)4](ClO4)4 ((−)-3), and [Pt3((+)-L2)2(Dmpi)4](ClO4)4 ((+)-3) [(−)-L1 = (−)-4,5-pinene-6′-phenyl-2,2′-bipyridine, (+)-L1 = (+)-4,5-pinene-6′-phenyl-2,2′-bipyridine), (−)-L2 = (−)-1,3-bis(2-(4,5-pinene)pyridyl)benzene, (+)-L2 = (+)-1,3-bis(2-(4,5-pinene)pyridyl)benzene, Dmpi = 2,6-dimethylphenyl isocyanide] (Chart 1). In aqueous solutions, (−)-1 and (+)-1 aggregate into one-dimensional helical chain structures through Pt···Pt, π–π, and hydrophobic–hydrophobic interactions. (−)-3 and (+)-3 represent a novel helical structure with Pt–Pt bonds. The formation of helical structures results in enhanced and distinct chiroptical properties. CPL was observed from the aggregates of (−)-1 and (+)-1 in water, as well as (−)-3 and (+)-3 in dichloromethane. The CPL activity can be switched reversibly (for (−)-1 and (+)-1) or irreversibly (for (−)-3 and (+)-3) by varying the temperature. These CPL-active materials based on our chiral Pt(II) complexes may have potential applications in photonic devices or biosensors.

Chart 1. Molecular Structures of (−)-1, (+)-1, (−)-2, (+)-2, (−)-3, and (+)-3.

Experimental Section

General Methods

All reagents were purchased from commercial suppliers and used as received. Caution! Perchlorates are potentially explosive and must be handled with great care and in small amounts. Collision and friction must be avoided. 2,6-Dimethylphenyl isocyanide may cause irritation. All reactions should be performed in a fume hood. Compounds (−)-L1, (+)-L1, (−)-L2, (+)-L2, Pt((−)-L1)Cl, Pt((+)-L1)Cl, Pt((−)-L2)Cl, and Pt((+)-L2)Cl were prepared according to the methods reported previously.12c,12d Mass spectra were acquired on an LCQ Fleet ESI mass spectrometer. The NMR spectra were obtained on a Bruker DRX-400, DRX-500, or DRX-600 spectrometer. Chemical shifts are reported relative to CH3OH/CD3OD (δ(1H) = 3.31 ppm, δ(13C) = 49.0 ppm) or CH2Cl2/CD2Cl2 (δ(1H) = 5.32 ppm, δ(13C) = 53.8 ppm). Coupling constants are given in hertz. UV–vis absorption spectra were measured on a UV-3600 spectrophotometer (using a 10 mm quartz cell for a concentration of 5 × 10–5 mol·L–1, using a 1 mm quartz cell for concentrations of 5 × 10–4 and 5 × 10–3 mol·L–1). Elemental analysis was performed on a PerkinElmer 240C analyzer. Photoluminescence (PL) spectra were measured by a Hitachi F-4600 PL spectrophotometer. The electronic circular dichroism (ECD) spectra of the Pt(II) complexes measured in aqueous, methanol, and/or dichloromethane solutions were recorded on a Jasco J-810 spectropolarimeter (using a 10 mm quartz cell for a concentration of 5 × 10–5 mol·L–1, using a 1 mm quartz cell for concentrations of 5 × 10–4 and 5 × 10–3 mol·L–1). The high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) images were obtained by employing a JEOL JEM-2100 transmission electron microscope with an acceleration voltage of 200 kV. The scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images were obtained on a Hitachi S-4800 scanning electron microscope at 20 kV. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was carried out by a PHI 5000 VersaProbe (U1VAC-PHI), and binding energies were measured relative to the C 1s peak (284.8 eV) of internal hydrocarbon. The resonance light scattering (RLS) spectra were obtained by synchronously scanning the excitation and emission monochromators (namely, Δλ = 0.0 nm) of a Hitachi F-4600 fluorescence spectrophotometer in the wavelength region from 300 to 800 nm. CPL and total luminescence spectra were recorded on an instrument described previously,17 operating in a differential photon-counting mode. The light source for excitation was a continuous wave 1000 W xenon arc lamp from a Spex Fluorolog-2 spectrofluorometer, equipped with excitation and emission monochromators with a dispersion of 4 nm/mm (SPEX, 1681B). To prevent artifacts associated with the presence of linear polarization in the emission,18 a high-quality linear polarizer was placed in the sample compartment and aligned so that the excitation beam was linearly polarized in the direction of emission detection (z-axis). The key feature of this geometry is that it ensures that the molecules that have been excited and that are subsequently emitting are isotropically distributed in the plane (x, y) perpendicular to the direction of emission detection. The optical system detection consisted of a focusing lens, long-pass filter, and 0.22 m monochromator. The emitted light was detected by a cooled EMI-9558B photomultiplier tube operating in photocounting mode. All measurements were performed with quartz cuvettes with a path length of 1.0 cm.

[Pt((−)-L1)(Dmpi)]Cl ((−)-1)

To a vigorously stirred solution of Pt((−)-L1)Cl (1 mmol, 560 mg) in 20 mL of dichloromethane precovered by 40 mL of water was added a small excess of 2,6-dimethylphenyl isocyanide (1.05 mmol, 138 mg) dissolved in 8 mL of dichloromethane. After reaction for 1 h at room temperature, the aqueous phase was separated, the solvents were evaporated, and red powders were obtained (95%). The pure product was obtained after several recrystallizations in MeOH/H2O solution. MS (ESI) (m/z): [M]+ calcd for C32H30N3Pt, 651.2; found, 651.5. Anal. Calcd for C32H30ClN3Pt ((−)-1): C, 55.93; H, 4.40; N, 6.12. Found: C, 55.90; H, 4.37; N, 6.10. 1H NMR (600 MHz, MeOD-d4, room temperature (rt)): δ 7.83 [s, 1H, H(11)], 7.68 [t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H, H(4)], 7.60 [s, 1H, H(8)], 7.59 [d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H, H(5)], 7.26 [d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H, H(3)], 7.13 [d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H, H(31)], 6.94 [d, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H, H(30, 32)], 6.90 [d, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H, H(14)], 6.76 [d, J = 6.6 Hz, 1H, H(17)], 6.65 [t, J = 6.6 Hz, 1H, H(15)], 6.43 [t, J = 6.6 Hz, 1H, H(16)], 3.14 [d, J = 18.0 Hz, 2H, H(19)], 2.85–2.89 [m, 1H, H(21b)], 2.60 [t, J = 5.4 Hz, 1H, H(22)], 2.38–2.41 [m, 1H, H(20)], 1.95 [s, 6H, H(34, 35)], 1.46 [s, 3H, H(24)], 1.22 [d, J = 10.8 Hz, 1H, H(21a)], 0.64 [s, 3H, H(25)]. 13C NMR (151 MHz, MeOD-d4, rt): δ 165.0 [C(2)], 156.0 [C(6)], 155.7 [C(7)], 153.3 [C(10)], 150.1 [C(9)], 148.0 [C(8)], 147.8 [C(13)], 144.1 [C(4)], 139.7 [C(18)], 137.9 [C(17)], 136.4 [C(26)], 136.0 [C(29), C(33)], 132.5 [C(16)], 132.0 [C(31)], 130.0 [C(30), C(32)], 127.3 [C(14)], 127.1 [C(15)], 127.0 [C(28)], 125.9 [C(11)], 121.3 [C(5)], 121.1 [C(3)], 46.0 [C(22)], 40.7 [C(20)], 40.1 [C(23)], 34.4 [C(19)], 32.2 [C(21)], 25.9 [C(24)], 22.1 [C(25)], 19.8 [C(34), C(35)]. XPS (eV): 73.0 (Pt 4f7/2), 76.4 (Pt 4f5/2).

[Pt((−)-L2)(Dmpi)]Cl ((−)-2)

To a vigorously stirred solution of Pt((−)-L2)Cl (1 mmol, 650 mg) in 50 mL of dichloromethane was slowly added an equivalent amount of 2,6-dimethylphenyl isocyanide (1 mmol, 131 mg) dissolved in 30 mL of dichloromethane over 1 h. After the reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for 4 h, the solvent was removed under reduced pressure, and the residue was purified by flash chromatography on an Al2O3 column with DCM/MeOH (20/1, v/v) as the eluent to give a yellow solid (70%). MS (ESI) (m/z): [M]+ calcd for C39H40N3Pt, 745.3; found, 745.6. Anal. Calcd for C39H40ClN3Pt ((−)-2): C, 59.95; H, 5.16; N, 5.38. Found: C, 59.93; H, 5.13; N, 5.35. 1H NMR (600 MHz, CD2Cl2-d2, rt): δ 8.25 [s, 2H, H(7)], 7.67 [s, 2H, H(10)], 7.55 [d, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H, H(3)], 7.45 [t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H, H(23)], 7.36 [t, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H, H(4)], 7.32 [d, J = 7.8 Hz, 2H, H(22)], 3.18–3.21 [m, 4H, H(11)], 2.81–2.83 [m, 2H, H(14)], 2.77–2.80 [m, 2H, H(13b)], 2.60 [s, 6H, H(24)], 2.38–2.41 [m, 2H, H(12)], 1.44 [s, 6H, H(16)], 1.28 [d, J = 10.2 Hz, 2H, H(13a)], 0.71 [s, 6H, H(17)]. 13C NMR (151 MHz, CD2Cl2-d2, rt): δ 168.5 [C(1)], 166.3 [C(5)], 152.1 [C(9)], 150.2 [C(7)], 145.6 [C(8)], 144.7 [C(2)], 136.2 [C(21)], 131.3 [C(23)], 129.1 [C(20), C(22)], 127.2 [C(4)], 126.1 [C(18)], 124.1 [C(3)], 121.0 [C(10)], 45.0 [C(14)], 39.9 [C(12)], 39.6 [C(15)], 33.9 [C(11)], 31.8 [C(13)], 25.8 [C(16)], 21.6 [C(17)], 19.5 [C(24)]. XPS (eV): 72.9 (Pt 4f7/2), 76.2 (Pt 4f5/2). The compound (−)-2-OTf was obtained by replacement of Cl with a OTf anion. An aqueous solution (10 mL) of silver trifluoromethanesulfonate (0.22 mmol, 56.5 mg) was added to a 20 mL dichloromethane solution of (−)-2 (0.2 mmol, 156.2 mg). After vigorous stirring for 15 min, the organic phase was separated and evaporated under vacuum.

[Pt3((−)-L2)2(Dmpi)4](ClO4)4 ((−)-3)

A mixture of (−)-2 (1 mmol, 781 mg) and excess 2,6-dimethylphenyl isocyanide (2 mmol, 262 mg) was stirred in 40 mL of dichloromethane at room temperature. After vigorous stirring for 24 h, an aqueous solution of AgClO4 (2 mmol, 414 mg) was added, and the resulting mixture was allowed to react for another 24 h. The organic layer was separated, and the aqueous phase was extracted twice with dichloromethane (20 mL × 2). The organic layers were combined, washed twice with water, and then dried over anhydrous sodium sulfate. After removal of the solvent under reduced pressure, the residue was washed with n-hexane twice, and green-yellow crystals were isolated by recrystallization in chloroform at 273 K (50%). MS (ESI) (m/z): [M]4+ calcd for C96H98N8Pt3, 487.0; found, 487.7. Anal. Calcd for C96H98Cl4N8O16Pt3 ((−)-3): C, 49.13; H, 4.21; N, 4.77. Found: C, 49.11; H, 4.19; N, 4.74. 1H NMR (400 MHz, CD2Cl2-d2, 273.15 K): δ 9.29 [s, 2H, H(17)], 7.79 [s, 2H, H(11)], 7.73 [d, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H, H(5)], 7.39–7.44 [m, 8H, H(8), H(4), H(38), H(14)], 7.25 [d, J = 7.6 Hz, 4H, H(37), H(39)], 7.21 [t, J = 7.6 Hz, 2H, H(48)], 7.04 [d, J = 7.6 Hz, 4H, H(47), H(49)], 6.52 [d, J = 7.2 Hz, 2H, H(3)], 3.36–3.41 [m, 2H, H(19b)], 3.20–3.25 [m, 2H, H(19a)], 2.71–2.75 [m, 6H, H(21b), H(29), H(26b)], 2.46 [s, 12H, H(41), H(42)], 2.42–2.44 [m, 2H, H(20)], 2.22–2.32 [m, 6H, H(22), H(26a), H(28b)], 2.17 [s, 12H, H(51), H(52)], 1.98–2.02 [m, 2H, H(27)], 1.33 [s, 6H, H(24)], 1.11 [s, 6H, H(32)], 1.06–1.09 [m, 2H, H(21a)], 0.57 [s, 6H, H(25)], 0.33 [s, 6H, H(31)], −0.53 [m, 2H, H(28a)]. 13C NMR (100 MHz, CD2Cl2-d2, 273.15 K): δ 164.2 [C(7)], 160.0 [C(13)], 152.6 [C(9)], 149.5 [C(15)], 148.2 [C(43)], 148.0 [C(17)], 147.7 [C(33)], 147.2 [C(1)], 145.0 [C(8)], 144.5 [C(10)], 143.0 [C(2)], 142.8 [C(16)], 136.6 [C(36), C(40)], 136.0 [C(46), C(50)], 131.9 [C(4)], 131.5 [C(3)], 131.1 [C(48)], 129.1 [C(37), C(39)], 128.7 [C(47), C(49)], 127.9 [C(38)], 127.1 [C(5)], 125.2 [C(45)], 124.7 [C(35)], 123.4 [C(14)], 122.3 [C(11)], 119.4 [C(6)], 44.5 [C(22)], 43.9 [C(29)], 39.6 [C(20)], 39.2 [C(30)], 39.0 [C(27)], 38.8 [C(23)], 34.0 [C(19)], 33.1 [C(26)], 32.0 [C(21)], 30.1 [C(28)], 25.6 [C(24)], 25.2 [C(32)], 22.1 [C(31)], 21.4 [C(25)], 19.2 [C(41), C(42)], 18.8 [C(51), C(52)]. XPS (eV): 73.3 (Pt 4f7/2), 76.7 (Pt 4f5/2).

X-ray Structure Determination

Yellow needles of complex (−)-1 were grown in acetonitrile/dichloromethane (1/1, v/v) solution at room temperature. Yellow rods of racemic 2-OTf were obtained by diffusion of diethyl ether into the acetonitrile solution of a mixture of (−)-2-OTf and (+)-2-OTf at room temperature, whereas green-yellow blocks of complexes (−)-3 and (+)-3 were isolated by recrystallization in the chloroform solution at 273 K. Moreover, the green-yellow crystal (−)-3′ (a different polymorph of (−)-3) can be obtained by evaporation of a mixed methanol/CD2Cl2 (1/1, v/v) solution at 273 K. Because of the poor diffracting ability of the very small needle crystal, the structure determination of (−)-1 is unsatisfactory, but it does provide accurate connectivity and packing information as well as valid bond distances and angles involving the heavy atoms in the structure. Single-crystal X-ray diffraction measurements were carried out on a Bruker SMART APEX charge-coupled device (CCD)-based diffractometer operating at room temperature. Intensities were collected with graphite-monochromatized Mo Kα radiation (λ = 0.71073 Å) operating at 50 kV and 30 mA using the ω/2θ scan mode. The data reduction was made with the Bruker SAINT package.19 Absorption corrections were performed using the SADABS program.20 The structures were solved by direct methods and refined on F2 by full-matrix least-squares using SHELXL-97 with anisotropic displacement parameters for all non-hydrogen atoms in all structures. Hydrogen atoms bonded to the carbon atoms were placed in calculated positions and refined in the riding mode, with C–H = 0.93 Å (methane) or 0.96 Å (methyl) and Uiso(H) = 1.2Ueq(Cmethane) or Uiso(H) = 1.5Ueq(Cmethyl). The water hydrogen atoms were located in the difference Fourier maps and refined with an O–H distance restraint [0.85(1) Å] and Uiso(H) = 1.5Ueq(O). All computations were carried out using the SHELXTL-97 program package.21 CCDC 989466–989469 and 1006137 contain the supplementary crystallographic data for this paper. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif.

Results and Discussion

Synthesis and Characterization

The precursors Pt((−)-L1)Cl and Pt((−)-L2)Cl were prepared according to the methods reported previously.12c,12d Complexes (−)-1 and (−)-2 can be obtained through ligand metathesis reaction of Pt((−)-L1)Cl and Pt((−)-L2)Cl with 2,6-dimethylphenyl isocyanide at room temperature.14b The unprecedented pair of trimeric helical complexes (−)-3 and (+)-3 were isolated at 273 K when excess 2,6-dimethylphenyl isocyanide was reacted with complexes (−)-2 and (+)-2, followed by addition of excess AgClO4 aqueous solution. Compounds (+)-1, (+)-2, and (+)-3 were obtained with the same procedures as for (−)-1, (−)-2, and (−)-3, respectively. All the complexes ((−)-1, (−)-2, and (−)-3) have been fully characterized by elemental analysis, NMR, XPS, and ESI mass spectrometry (Figures S1–S22, Supporting Information).

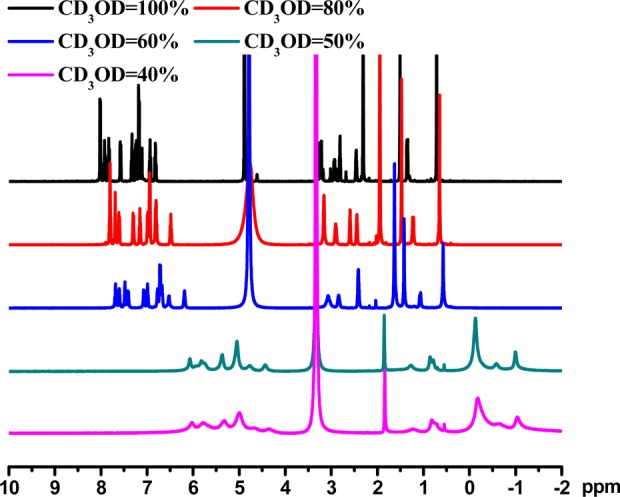

Except (−)-1 and (+)-1, all these complexes are insoluble in water. (−)-1 and (+)-1 show aggregation behaviors in aqueous solutions. The 1H NMR spectra of (−)-1 show broadening and upfield shifts in the mixed solution of CD3OD and D2O (Figure 1), suggesting the presence of molecular association through Pt···Pt, π–π, and hydrophobic–hydrophobic interactions when D2O was added. Similar upfield shifts have also been found in other related deaggregation–aggregation systems, in which broad and featureless NMR signals are exhibited in the more polar solvents.22 Upon increasing the concentration of water to ca. 10–2 mol·L–1, (−)-1 and (+)-1 form hydrogels (Figure S23, Supporting Information). SEM and TEM also demonstrate fibrillar structures with an in-plane orientation, characteristic for aggregation of platinum(II) complexes (Figure S24, Supporting Information).22b No aggregation effect was observed for (−)-2, (+)-2, (−)-3, and (+)-3.

Figure 1.

1H NMR spectra of (−)-1 in a mixed solution of CD3OD and D2O in the ratios shown (Bruker DRX-500, rt).

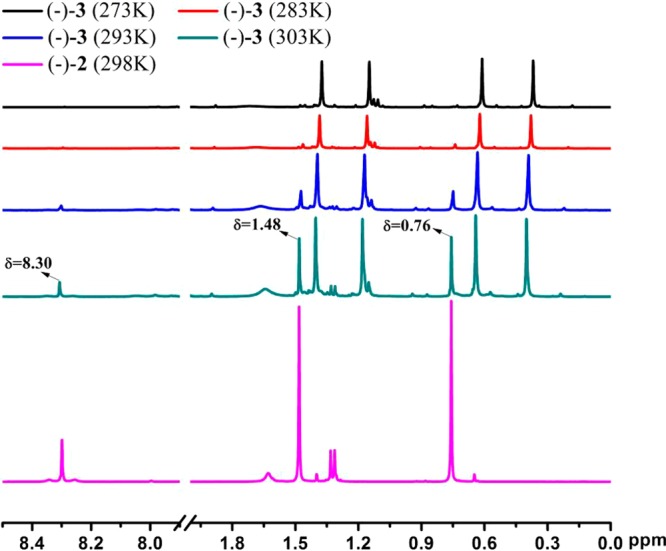

(−)-3 and (+)-3 are very stable in the solid state but partially decompose in dichloromethane solution at room temperature. As shown in Figure 2, complex (−)-3 starts to partially decompose at 293 K and turns into complex (−)-2, as evidenced by additional peaks at ca. 8.30, 1.48, and 0.76 ppm after decomposition. Therefore, all the spectroscopic data of (−)-3 and (+)-3 were measured at 273 K except where otherwise noted.

Figure 2.

1H NMR spectra of (−)-3 in CD2Cl2 at different temperatures and (−)-2 in CD2Cl2 at room temperature (Bruker DRX-500).

Crystal Structures

Complex (−)-1 crystallizes in the P21 space group of the monoclinic system (Table 1). Two isolated molecules are included in the asymmetrical unit of complex (−)-1 (Figure 3a). The Pt–C (1.86–2.02 Å) and Pt–N (1.91–2.12 Å) (Table S1, Supporting Information) bond lengths and relevant angles are in the typical ranges for Pt(C^N^N) isocyanide complexes (C^N^N denoted as (−)-L1).14 The rings of 2,6-dimethylphenyl isocyanide are almost coplanar with the Pt(C^N^N) unit, with dihedral angles between the two planes of 2.93° and 3.94°. The molecules are further slip-stacked in head-to-head mode along the a axis with effective π–π contacts (3.379 Å) (Figure 3b). The molecules are aligned in a zigzag style. The Pt···Pt distances between adjacent Pt atoms are 3.812 and 4.129 Å, respectively, indicating that no Pt···Pt interactions are involved.

Table 1. Crystallographic Data of (−)-1, 2-OTf, (−)-3, (+)-3, and (−)-3′.

| (−)-1 | 2-OTf | (−)-3 | (+)-3 | (−)-3′ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| formula | C64H70Cl2N6O5Pt2 | C40H40F3N3O3PtS | C100H108Cl16N8O19Pt3 | C100H108Cl16N8O19Pt3 | C96H102Cl4N8O18Pt3 |

| Mr | 1464.34 | 894.90 | 2878.41 | 2878.41 | 2382.93 |

| cryst syst | monoclinic | monoclinic | orthorhombic | orthorhombic | orthorhombic |

| space group | P21 | C2/c | P21212 | P21212 | P21212 |

| a, Å | 7.321(4) | 19.598(6) | 17.1747(11) | 17.2735(14) | 19.4956(15) |

| b, Å | 27.917(13) | 18.956(6) | 31.1089(17) | 31.0196(17) | 21.2065(17) |

| c, Å | 14.261(8) | 10.500(3) | 11.8402(12) | 11.8157(12) | 11.5739(9) |

| α, deg | 90.00 | 90.00 | 90.00 | 90.00 | 90.00 |

| β, deg | 98.997(8) | 115.869(4) | 90.00 | 90.00 | 90.00 |

| γ, deg | 90.00 | 90.00 | 90.00 | 90.00 | 90.00 |

| V, Å3 | 2879(2) | 3509.9(19) | 6326.1(8) | 6331.1(9) | 4785.0(6) |

| Z | 2 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| T, K | 296(2) | 296(2) | 291(2) | 291(2) | 291(2) |

| radiation λ, Å | 0.71073 | 0.71073 | 0.71073 | 0.71073 | 0.71073 |

| Dcalcd, g/cm–3 | 1.689 | 1.694 | 1.511 | 1.510 | 1.654 |

| μ, mm–1 | 5.003 | 4.117 | 3.707 | 3.704 | 4.557 |

| F(000) | 1452 | 1784 | 2844 | 2844 | 2360 |

| cryst size, mm3 | 0.20 × 0.08 × 0.04 | 0.20 × 0.15 × 0.10 | 0.28 × 0.20 × 0.18 | 0.27 × 0.23 × 0.17 | 0.26 × 0.22 × 0.20 |

| θ range, deg | 1.46–25.00 | 1.58–24.99 | 1.31–26.00 | 1.35–26.00 | 1.42–28.37 |

| no. of reflns measd | 20390 | 11475 | 37780 | 50622 | 33844 |

| no. of unique reflns | 9518 | 3075 | 12407 | 12412 | 11906 |

| Rint | 0.1269 | 0.0586 | 0.0246 | 0.0192 | 0.0509 |

| no. of reflns with F2 > 2σ(F2) | 6587 | 2867 | 10650 | 10804 | 10158 |

| no. of params | 594 | 264 | 691 | 691 | 624 |

| goodness-of-fit on F2 | 1.301 | 1.046 | 1.073 | 1.016 | 1.048 |

| R1 [F2 > 2σ(F2)] | 0.2044 | 0.0450 | 0.0498 | 0.0447 | 0.0494 |

| wR2 (all data) | 0.3894 | 0.1379 | 0.1242 | 0.1149 | 0.1272 |

| Δρmax, Δρmin, e Å–3 | 3.658, −3.440 | 1.427, −1.524 | 1.979, −1.828 | 1.693, −0.765 | 0.715, −1.577 |

Figure 3.

X-ray crystal structures of (−)-1 (a, b) and (−)-3 and (+)-3 (c). H atoms, solvent molecules, and anions are omitted for clarity, and the percentage of thermal ellipsoid probability is 30%.

Attempts to grow single crystals for (−)-2 and (+)-2 were not successful. However, we were able to obtain a racemic crystal of 2-OTf by substituting the Cl with OTf. As shown in Figure S25 (Supporting Information), the coordination environment of Pt(II) atoms in 2-OTf is very similar to that of (−)-1, showing a slightly distorted square-planar configuration. However, the torsion angle (17.33°) between the ring of 2,6-dimethylphenyl isocyanide and the Pt(N^C^N) plane in 2-OTf is more salient relative to that of (−)-1 (N^C^N denoted as (−)-L2). In the packing diagram of 2-OTf, two isolated molecules ((−)-2 and (+)-2 cations appear alternately) are slip-stacked in head-to-tail mode along the c axis (Figure S26, Supporting Information). Owing to the steric hindrance of pinene groups in 2-OTf, the neighbor molecules could not approach each other closely in a face-to-face manner and the nearest Pt···Pt distance is 6.01 Å, suggesting that neither distinct Pt···Pt nor π–π interactions are present.

The crystals of (−)-3 and (+)-3 recrystallized in CHCl3 at 273 K reside in the P21212 space group of the orthorhombic system (Table 1). In the trimeric structure of (−)-3, two Pt ions (top and bottom) coordinate with two carbon atoms of 2,6-dimethylphenyl isocyanide and one carbon atom and one nitrogen atom of the N^C^N ligands. These two Pt ions are bridged by the central Pt ion, which is coordinated to nitrogen atoms of the N^C^N ligands (Figure 3c). The coordination number of the top and bottom Pt ions (Pt1 and Pt1A in Figure 3c) is five, and both of them exhibit the distorted tetragonal pyramid geometry, while the coordination environment of the central Pt ion (Pt2 in Figure 3c) with four-coordinate atoms is a distorted square-planar geometry. For the same N^C^N ligand, one side pyridine ring presents a twist of 44.63° relative to the central benzene plane, and the configuration of such torsion is suited to coordinate to Pt2 (Figure 3c). In addition, the two pyridine rings coordinated to the central Pt ion (Pt2) show a significant twisted angle of 71.85°. The two chiral N^C^N ligands are thus wrapped around the Pt ions in a helical fashion. The Pt–Pt bond distances (dPt1–Pt2 and dPt1A–Pt2) are both 2.886 Å, which is significantly less than the sum of van der Waals radii (3.4 Å) of two Pt atoms and indicates the presence of a Pt–Pt bond similar to other polynuclear Pt complexes.23 Furthermore, Pt1–Pt2–Pt1A deviates significantly from a linear geometry with a bond angle of 158.47°. As manifested in the molecular packing diagram (Figure S27, Supporting Information), no significant intermolecular interactions were observed for (−)-3 in virtue of great steric hindrance of neighboring trinuclear molecules. Complex (+)-3 exhibits a mirror structure to that of (−)-3, in accordance with their enantiomeric nature (Figure 3c).

By using different crystallization solvents (mixed methanol/CD2Cl2 solution), a different polymorph of (−)-3 was obtained (denoted as (−)-3′). The molecular structure of (−)-3′ is essentially identical to that of (−)-3 (Figure S28, Supporting Information). The trimetallic molecule of (−)-3′ displays a similar helical configuration, with the Pt–Pt bond length being 2.875 Å and the Pt–Pt–Pt angle being 160.74°. However, the angle of molecular arrangement in the ab plane in (−)-3′ is different from that of (−)-3 (64.23° for (−)-3 and 53.39° for (−)-3′, as shown in Figure S27 and Figure S28). Moreover, as compared to (−)-3, the molecules are more compact along the b axis in (−)-3′ (Figure S27 and Figure S28), which can also be reflected by the difference in their cell lengths.

UV–Vis Absorption and Emission Spectra

The UV–vis absorption spectra of (−)-1, (+)-1, (−)-2, (+)-2, (−)-3, and (+)-3 are shown in Figure 4, and spectroscopic data are summarized in Table S2 (Supporting Information). All these complexes exhibit characteristic absorption bands for typical cyclometalated platinum(II) complexes, i.e., intraligand (IL) transitions (ε > 104 L·mol–1·cm–1) in the region of 200–310 nm and metal-to-ligand charge transfer (MLCT) mixed with ligand-to-ligand charge transfer (LLCT) transitions (ε > 103 L·mol–1·cm–1) in the region of 330–450 nm.13,14 (−)-1 (in MeOH) and (−)-2 and (−)-3 (in dichloromethane) are emissive at room temperature (Figure S29–S30, Table S2, Supporting Information). The high-energy emissive state of (−)-1 in methanol solution (λem = 521 nm) can be assigned to the combination of 3MLCT and 3LLCT excited states,14 while the highly structured emission spectra of (−)-2 and (−)-3 can be mainly assigned as the ligand-centered 3π–π* state.13,14b The profiles of emission spectra of complexes (−)-2 and (−)-3 are similar in dichloromethane solution (Figure S30), indicating that the presence of Pt–Pt bonds in (−)-3 and (+)-3 does not change the nature of the frontier orbitals.

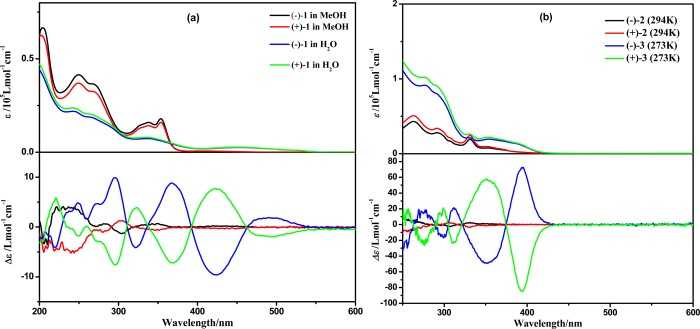

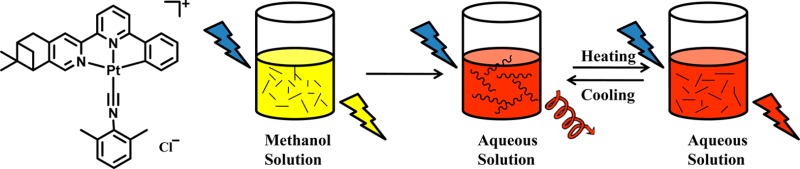

Figure 4.

(a) UV–vis absorption and ECD spectra of (−)-1 and (+)-1 in MeOH and H2O at 5 × 10–5 mol·L–1. (b) UV–vis absorption and ECD spectra of (−)-2 and (+)-2 in dichloromethane at 5 × 10–5 mol·L–1 (294 K) and (−)-3 and (+)-3 in dichloromethane at 2.5 × 10–5 mol·L–1 (273 K).

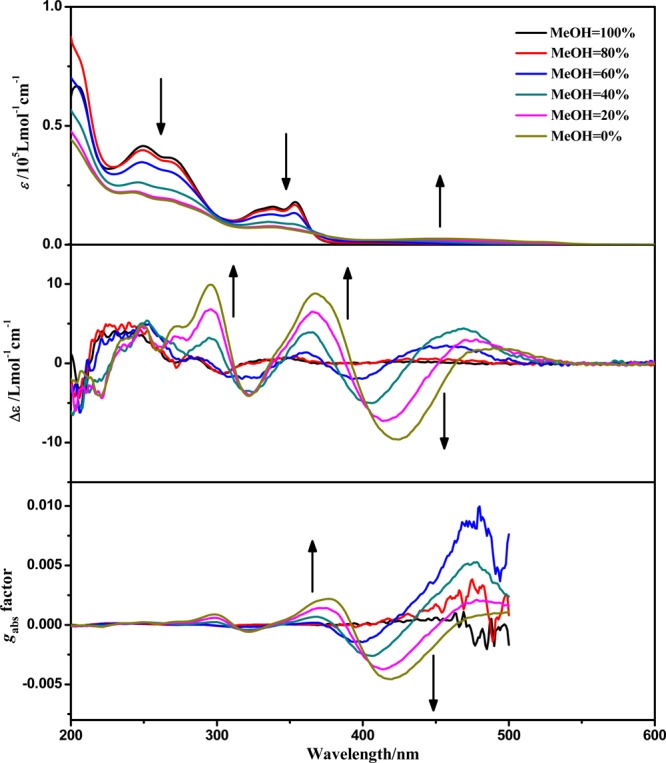

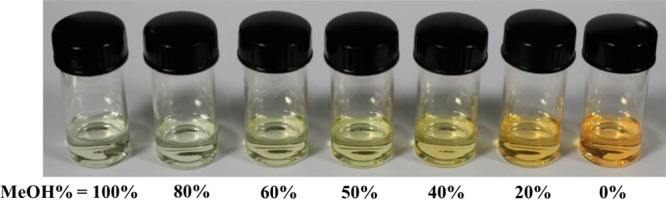

When (−)-1 was dissolved in water, the absorption intensity in the range of 200–380 nm decreased while a new low-energy absorption in the range of 420–550 nm emerged with increasing H2O content, resulting from different degrees of aggregation in mixed solvents with various ratios (Figure 5). One clear isosbestic point at 366 nm can be distinguished, indicating a clean conversion between the nonaggregate state and aggregate species. The color difference of the solution can intuitively reflect the aggregation process (Figure 6). As the content of H2O increased, the color of the solution changed from pale yellow to orange. The orange solution can be attributed to formation of aggregate species though Pt···Pt, π–π, and hydrophobic–hydrophobic interactions. As a consequence, the absorption at around 500 nm is assigned to a metal–metal-to-ligand charge transfer (MMLCT) transition.14 When excited at 420 nm, a low-energy emission (λem = 640 nm) was observed (Figure S29, Supporting Information) in aqueous solution which can be attributed to the 3MMLCT excited state.14b As expected, the excitation spectra exhibited an emergence of a low-energy band with increasing content of H2O, which is in line with a 1MMLCT transition of the absorption spectra (Figure S29). The UV–vis absorption and photoluminescence of (−)-1 with various concentrations in aqueous solution have also been carried out (Figure S31 and Figure S32, Supporting Information). Within the concentration range of 5 × 10–5 to 5 × 10–3 mol·L–1, only a small change of the extinction coefficient was found, suggesting that well-defined aggregates have formed even in the diluted solution and therefore the aggregation is insensitive to concentration changes. Similar observations have been reported in the previous work that cyclometalated platinum(II) complexes can oligomerize in water even at a dilution of 2 × 10–5 mol·L–1.14b Similarly, the emission spectra of (−)-1 in water were concentration-independent, and the emission maximum remained at 640 nm.

Figure 5.

UV–vis absorption and ECD spectra and gabs factors of (−)-1 (5 × 10–5 mol·L–1) in a mixed solution of MeOH and H2O in the ratios shown.

Figure 6.

Photograph of (−)-1 (10–4 mol·L–1) in a mixed solution of MeOH and H2O in the ratios shown (under ambient light).

This solvent-induced aggregation of (−)-1 was further evidenced by the enhanced signal of RLS spectra (Figure S33, Supporting Information). Upon increasing the H2O content, the intensity of the RLS signal in the range from 350 to 600 nm was significantly strengthened, indicating the formation of aggregates in the solution and therefore the chromophores were strongly coupled.24

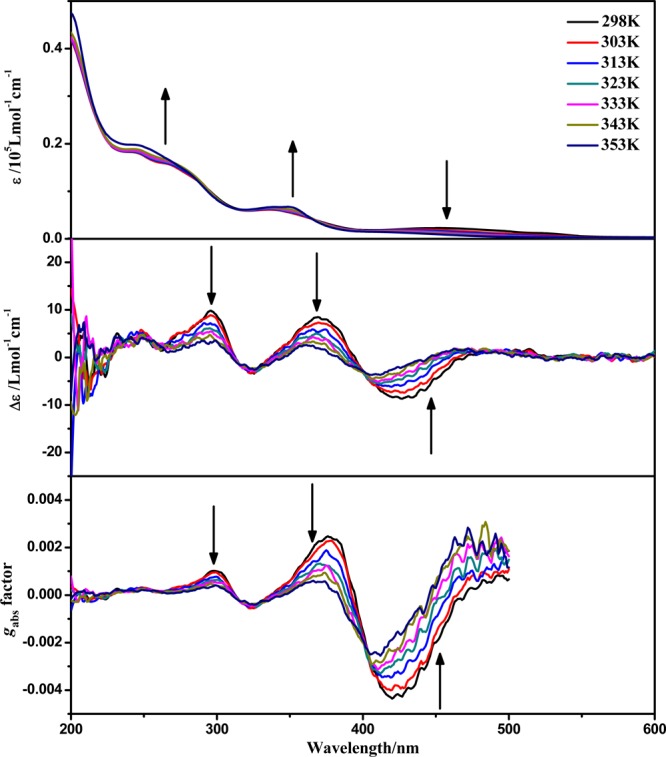

As shown in Figure 7, the aggregation of (−)-1 is also sensitive to temperature. Upon increasing the temperature, the absorption peak at 460 nm associated with the MMLCT transition shows a slight drop in intensity; concomitantly the peaks at 350 and 250 nm related to the MLCT/LLCT transition become more intense. An isosbestic point can be found at 366 nm, resembling the solvent-induced absorption variance. These changes can be ascribed to the attenuation of Pt···Pt and π–π interactions at higher temperature, leading to the deaggregation of the molecules.22 The emission intensity also presents a drastic drop, and the emission maximum has a slight blue shift upon increasing the temperature (Figure S34, Supporting Information), which further corroborates the deaggregation of molecules.22

Figure 7.

UV–vis absorption and ECD spectra and gabs factors of (−)-1 in H2O at 5 × 10–5 mol·L–1 with different temperatures.

The UV–vis absorption spectra and emission spectra of (−)-3 measured at different temperatures above 273 K show a continuous variance due to decomposition (Figure S35 and S36, Supporting Information). As shown in Figure S35, when the temperature changes from 273 to 294 K, the absorbance at 394 nm decreases, while the absorptions of the peaks at 331 and 291 nm increase. Although the emission maximum of (−)-3 shows a small change upon increasing the temperature, the emission intensity of the shoulder peak at 525 nm exhibits a distinct drop (Figure S36).

ECD Spectra

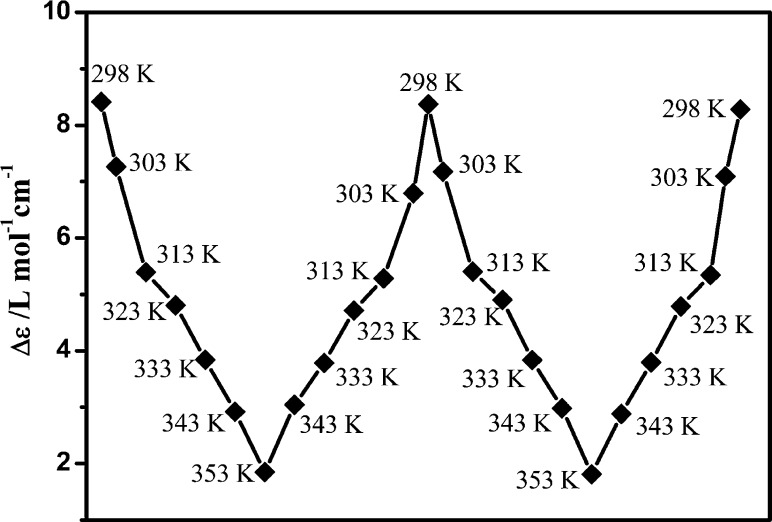

Figure 4 shows the ECD spectra of (−)-1, (+)-1, (−)-2, (+)-2, (−)-3, and (+)-3. The ECD spectrum of (−)-1 shows moderate Cotton effects (positive, 240, 284, and 346 nm; negative, 303 nm) in methanol solution; however, a significantly different and enhanced ECD spectrum (positive, 250, 300, 370, and 480 nm; negative, 320 and 420 nm) was observed in water. The anisotropy gabs factor6 becomes higher with increasing H2O content (Figure 5), and it reaches +0.0022 at 377 nm and −0.0046 at 420 nm in pure aqueous solution, which are 1 order of magnitude larger than those of the methanol solution at the corresponding wavelengths. Owing to the dissociation of molecules upon increasing the temperature, the chiral signals of (−)-1 in water solution decrease upon increasing the temperature of the sample from 298 to 353 K (Figure 7).22b When monitored at 370 nm, the chiral signals of (−)-1 can be reversibly tuned by changing the temperature, and no distinct degeneration can be found, indicating the persistence of temperature-induced ECD switching (Figure 8). In addition, concentration-dependent ECD spectra of (−)-1 in aqueous solution have been obtained (Figure S31, Supporting Information). The ECD signals and anisotropy gabs factors were virtually unchanged upon increasing the concentration, suggesting that well-ordered aggregates were formed in the diluted aqueous solution. Therefore, the chiral environment of (−)-1 is solvent and temperature dependent but insensitive to the concentration in water.

Figure 8.

Reversible process of temperature-induced ECD switching (monitored at 370 nm) of (−)-1.

The ECD spectrum of (−)-2 in a dichloromethane solution shows weak positive Cotton effects at 330 and 255 nm and a weak negative Cotton effect at 307 nm (Figure 4b). However, the ECD spectrum of (−)-3 exhibits two extremely intense bands at 350 and 395 nm in addition to the series of Cotton effects in the range of 250–320 nm (Figure 4b). The gabs factor6 of (−)-3 is −0.0026 at 346 nm and +0.0071 at 401 nm, which are about 15 times larger than those of (−)-2 at the corresponding wavelengths. The intensity of the Cotton effect of (−)-3 decreases upon increasing the temperature from 273 to 294 K owing to decomposition (Figure S35, Supporting Information).

The significant enhancement of chirality of (−)-1 and (+)-1 from MeOH to H2O solutions, and from (−)-2 and (+)-2 to (−)-3 and (+)-3, could be elucidated from their structural changes. For (−)-1 and (+)-1 in MeOH solutions, the molecules are dissociated and the chirality of the slightly distorted square-planar complexes is rather weak. When (−)-1 and (+)-1 are dissolved in water, the molecules are inclined to aggregate into one-dimensional chain structures through Pt···Pt, π–π, and hydrophobic–hydrophobic interactions, as already reported in the literature14b and also evidenced by the appearance of an MMLCT in the absorption and emission spectra. Due to the steric hindrance of the bulky pinene groups in (−)-1 and (+)-1, the adjacent molecules have to be staggered from each other alongside the Pt···Pt chain, thus forming a helix and enhancing the chiral environment. Increasing the temperature disrupts the helical aggregation and subsequently results in a less pronounced chiral environment. As a consequence, the strong ECD signals of (−)-1 and (+)-1 in water should come from helical chirality of aggregated chromophores rather than intrinsic chirality of the separated molecules. Intermolecular Pt···Pt, π–π, and hydrophobic–hydrophobic interactions can be strengthened or weakened by variations of the solvent (MeOH/H2O) ratios and temperature, producing aggregates of (−)-1 and (+)-1 with different helicity degrees and resulting in different ECD signals. For (−)-3 and (+)-3, the helical structures, which enhance the chiroptical activity, have been revealed by the single-crystal X-ray diffraction studies.

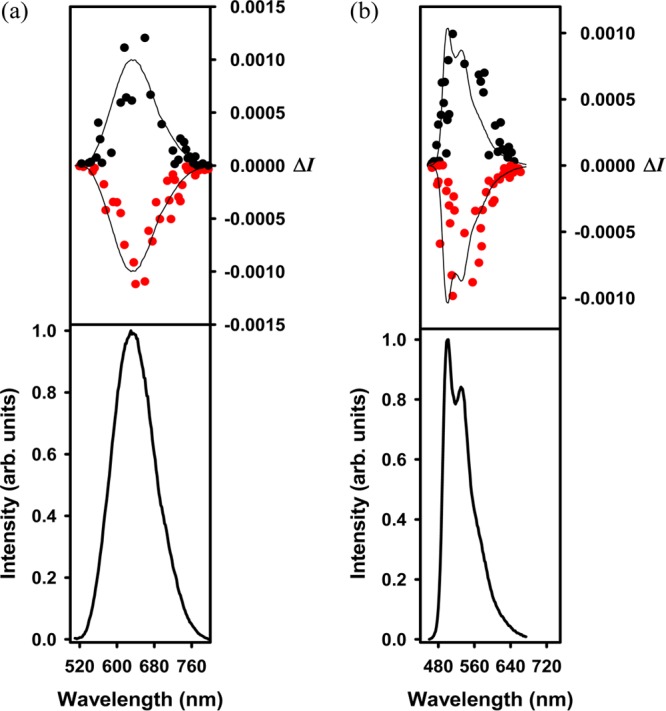

CPL

According to the temperature/solvent-induced variance of chirality in the ground state as evidenced in the ECD spectra, the chiral signals were enhanced through formation of an intramolecular helical structure or intermolecular helical aggregation. Therefore, we envision that interesting CPL activity in the corresponding excited state would be present. Therefore, the CPL spectra of (−)-1 and (+)-1 were measured in 1 mM MeOH and H2O solutions, whereas the CPL spectra of (−)-2, (+)-2, (−)-3, and (+)-3 were measured in 1 mM dichloromethane solutions. Although (−)-1 and (+)-1 in MeOH solutions and (−)-2 and (+)-2 in dichloromethane solutions did not exhibit any CPL activity at 295 K, we were able to observe a measurable CPL activity for (−)-1 and (+)-1 in aqueous solutions at 295 K, as well as for (−)-3 and (+)-3 in dichloromethane solutions at 278 K (Figure 9). The glum(6) values around the maximum emission wavelength are −0.0018/+0.0012 for (−)-1/(+)-1 at 295 K and +0.0024/–0.0024 for (−)-3/(+)-3 at 278 K, respectively. Interestingly, the CPL activity was lost for aqueous solutions of (−)-1 and (+)-1 at 353 K (no conclusive CPL signal was detected; the data points are scattered and non-mirror-symmetric) (Figure S37, Supporting Information) but can be recovered upon cooling to 295 K. The CPL activity of the MeOH solution of (−)-3 and (+)-3 was weakened at 295 K (glum = +0.0016/–0.0016) as compared to that at 278 K (Figure S37), in agreement with the above-mentioned observation that part of the helical trinuclear complexes were decomposed into mononuclear complexes with weak chirality upon increasing the temperature. This process is irreversible.

Figure 9.

Circularly polarized luminescence (upper curves) and total luminescence (lower curves) spectra of (a) (−)-1 and (+)-1 (left panel) in 1 mM aqueous solutions at 295 K and (b) (−)-3 and (+)-3 (right panel) in 1 mM dichloromethane solutions at 278 K.

It is noteworthy that, although CPL signals of platinum(II) complexes have been reported recently,8b the Pt atom is not the stereogenic center in these systems, and the CPL activity comes from the helical organic luminophore. However, in our study, the Pt atoms play a key role in the formation of helical aggregations or helical structures, which control the circularly polarized luminescent behavior of the chiral platinum(II) complexes. The asymmetric centers on the pinene groups are remote from the metal atom and have little direct effect on the CPL spectra, but they could have an influence on chiral coordination or the helical arrangement, causing measurable CPL signals. We have also observed the CPL-active 3MMLCT excited state, which is unprecedented in the literature to the best of our knowledge. Moreover, we demonstrated a very novel temperature-dependent tuning of the CPL activity.

Conclusions

In conclusion, two chiral cyclometalated platinum(II) complexes, [Pt((−)-L1)(Dmpi)]Cl ((−)-1) and [Pt((+)-L1)(Dmpi)]Cl ((+)-1), and [Pt((−)-L2)(Dmpi)]Cl ((−)-2) and [Pt((+)-L2)(Dmpi)]Cl ((+)-2), have been synthesized and characterized. (−)-1 and (+)-1 aggregated in water via Pt···Pt, π–π, and hydrophobic–hydrophobic interactions. (−)-2 and (+)-2 reacted with excess 2,6-dimethylphenyl isocyanide to give the trimetallic helical complexes [Pt3((−)-L2)2(Dmpi)4](ClO4)4 ((−)-3) and [Pt3((+)-L2)2(Dmpi)4](ClO4)4 ((+)-3). Significant enhancement and/or alteration of chirality was observed for (−)-1 and (+)-1 in aqueous solutions and (−)-3 and (+)-3, as revealed in the ECD spectroscopic study. The enhancement and/or alternation of chirality for (−)-1 and (+)-1 in aqueous solutions and (−)-3 and (+)-3 led to a detectable CPL activity for these platinum(II) complexes. More interestingly, the CPL activity can be switched reversibly (for (−)-1 and (+)-1) or irreversibly (for (−)-3 and (+)-3) due to deaggregation or decomposition upon increasing the temperature. Extension of this work to other chiral luminescent Pt(II) complexes and studies aimed at utilizing these complexes in photonic devices or biosensors are under way and will be reported in due course.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants 91022031 and 21021062), Major State Basic Research Development Program (Grants 2013CB922100 and 2011CB808704), and Doctoral Fund of the Ministry of Education of China (Grant 20120091130002). G.M. thanks the National Institutes of Health, Minority Biomedical Research Support (Grants 1 SC3 GM089589-05 and 3 S06 GM008192-27S1), and the Henry Dreyfus Teacher-Scholar Award for financial support.

Supporting Information Available

Synthesis and characterization of complexes (+)-1, (+)-2, and (+)-3, X-ray crystallographic data for complexes (−)-1, 2-OTf, (−)-3, (+)-3, and (−)-3′ in CIF format, NMR, ESI mass, and XPS spectra for the complexes, photographs and SEM and TEM images of hydrogels of (−)-1, X-ray crystal structures and packing diagrams of 2-OTf, (−)-3, and (−)-3′, emission spectra of (−)-1, (−)-2, and (−)-3, RLS spectra of (−)-1, UV–vis absorption and ECD spectra and gabs factors of (−)-3 at various temperatures, CPL and total luminescence spectra of (−)-1 and (+)-1 in 1 mM aqueous solution at 353 K and (−)-3 and (+)-3 in 1 mM MeOH solution at 295 K, selected bond lengths and angles of complexes (−)-1, 2-OTf, (−)-3, (+)-3, and (−)-3′, and absorption and emission data of complexes (−)-1, (−)-2, and (−)-3. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Funding Statement

National Institutes of Health, United States

Supplementary Material

References

- a Riehl J. P.; Muller G.. Handbook on the Physics and Chemistry of Rare Earths; North-Holland Publishing Co.: Amsterdam, 2005; Vol. 34, pp 289–357. [Google Scholar]; b Riehl J. P.; Muller G.. Circularly Polarized Luminescence Spectroscopy and Emission-Detected Circular Dichroism. In Comprehensive Chiroptical Spectroscopy, 1st ed.; Berova N., Polavarapu P. L., Nakanishi K., Woody R. W., Eds.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, 2012; Vol. 1, Instrumentation, Methodologies, and Theoretical Simulations, Chapter 3, pp 65–90. [Google Scholar]; c Petoud S.; Muller G.; Moore E. G.; Xu J.; Sokolnicki J.; Riehl J. P.; Le U. N.; Cohen S. M.; Raymond K. N. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 77–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riehl J. P. Tech. Instrum. Anal. Chem. 1994, 14, 207–240. [Google Scholar]

- Carr R.; Evans N. H.; Parker D. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012, 41, 7673–7686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Peeters E.; Christiaans M. P. T.; Janssen R. A. J.; Schoo H. F. M.; Dekkers H. P. J. M.; Meijer E. W. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1997, 119, 9909–9910. [Google Scholar]; b Grell M.; Bradley D. D. C. Adv. Mater. 1999, 11, 895–905. [Google Scholar]

- For selected examples, see:; a Maupin C. L.; Parker D.; Williams J. A. G.; Riehl J. P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998, 120, 10563–10564. [Google Scholar]; b Gregoliński J.; Starynowicz P.; Hua K. T.; Lunkley J. L.; Muller G.; Lisowski J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 17761–17773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Lunkley J. L.; Shirotani D.; Yamanari K.; Kaizaki S.; Muller G. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 13814–13815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Yuasa J.; Ohno T.; Miyata K.; Tsumatori H.; Hasegawa Y.; Kawai T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 9892–9902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Kitchen J. A.; Barry D. E.; Mercs L.; Albrecht M.; Peacock R. D.; Gunnlaugsson T. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 704–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The degree of CPL is given by the luminescence dissymmetry ratio, glum(λ) = 2ΔI/I = 2(IL – IR)/(IL + IR), where IL and IR refer, respectively, to the intensities of the left and right circularly polarized emissions. The ECD anisotropy factor is defined as gabs = Δε/ε, where Δε is the molecular extinction coefficient of the ECD spectrum and ε is the molecular extinction coefficient of the UV–vis absorption spectrum.

- a Field J. E.; Muller G.; Riehl J. P.; Venkataraman D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 11808–11809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Ikeda T.; Masuda T.; Hirao T.; Yuasa J.; Tsumatori H.; Kawai T.; Haino T. Chem. Commun. 2012, 48, 6025–6027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Sánchez-Carnerero E. M.; Moreno F.; Maroto B. L.; Agarrabeitia A. R.; Ortiz M. J.; Vo B. G.; Muller G.; de la Moya S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 3346–3349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Coughlin F. J.; Westrol M. S.; Oyler K. D.; Byrne N.; Kraml C.; Zysman-Colman E.; Lowry M. S.; Bernhard S. Inorg. Chem. 2008, 47, 2039–2048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Shen C.; Anger E.; Srebro M.; Vanthuyne N.; Deol K. K.; Jefferson T. D. Jr.; Muller G.; Williams J. A. G.; Toupet T.; Roussel C.; Autschbach J.; Réau R.; Crassous J. Chem. Sci. 2014, 5, 1915–1927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Ziegler M.; Monney V.; Stoeckli-Evans H.; von Zelewsky A.; Sasaki I.; Dupic G.; Daran J.-C.; Balavoine G. G. A. J. Chem. Soc., Dalton Trans. 1999, 667–676. [Google Scholar]; b Schaffner-Hamann C.; von Zelewsky A.; Barbieri A.; Barigelletti F.; Muller G.; Riehl J. P.; Neels A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 9339–9348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Mamula O.; Lama M.; Telfer S. G.; Nakamura A.; Kuroda R.; Stoeckli-Evans H.; Scopelitti R. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 2527–2531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Oyler K. D.; Coughlin F. J.; Bernhard S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007, 129, 210–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Maeda H.; Bando Y.; Shimomura K.; Yamada I.; Naito M.; Nobusawa K.; Tsumatori H.; Kawai T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 9266–9269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Okano K.; Taguchi M.; Fujiki M.; Yamashita T. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 12474–12477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Gopal A.; Hifsudheen M.; Furumi S.; Takeuchi M.; Ajayaghosh A. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 10505–10509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Maeda H.; Bando Y. Pure Appl. Chem. 2013, 85, 1967–1978. [Google Scholar]; e Yuasa J.; Ueno H.; Kawai T. Chem.—Eur. J. 2014, 20, 8621–8627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Satrijo A.; Meskers S. C. J.; Swager T. M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006, 128, 9030–9031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Hayasaka H.; Miyashita T.; Tamura K.; Akagi K. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2010, 20, 1243–1250. [Google Scholar]; c Kumar J.; Nakashima T.; Tsumatori H.; Mori M.; Naito M.; Kawai T. Chem.—Eur. J. 2013, 19, 14090–14097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Kozhevnikov V. N.; Donnio B.; Bruce D. W. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 6286–6289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Wenger O. S. Chem. Rev. 2013, 113, 3686–3733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Zhang X.-P.; Wu T.; Liu J.; Zhang J.-X.; Li C.-H.; You X.-Z. J. Mater. Chem. C 2014, 2, 184–194. [Google Scholar]; d Zhang X.-P.; Wu T.; Liu J.; Zhao J.-C.; Li C.-H.; You X.-Z. Chirality 2013, 25, 384–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams J. A. G. Top. Curr. Chem. 2007, 281, 205–268. [Google Scholar]

- a Lai S.-W.; Lam H.-W.; Lu W.; Cheung K.-K.; Che C.-M. Organometallics 2002, 21, 226–234. [Google Scholar]; b Lu W.; Chen Y.; Roy V. A. L.; Chui S. S.-Y.; Che C.-M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 7621–7625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider J.; Du P.; Jarosz P.; Lazarides T.; Wang X.; Brennessel W. W.; Eisenberg R. Inorg. Chem. 2009, 48, 4306–4316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang P.; Leung C.-H.; Ma D.-L.; Sun R. W.-Y.; Yan S.-C.; Chen Q.-S.; Che C.-M. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 2554–2558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunet E.; Jiménez L.; de Victoria-Rodriguez M.; Luu V.; Muller G.; Juanes O.; Rodríguez-Ubis J. C. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 2013, 169, 222–234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dekkers H. P. J. M.; Moraal P. F.; Timper J. M.; Riehl J. P. Appl. Spectrosc. 1985, 39, 818–821. [Google Scholar]

- SAINT-Plus, version 6.02; Bruker Analytical X-ray Systems: Madison, WI, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Sheldrick G. M.SADABS, an Empirical Absorption Correction Program; Bruker Analytical X-ray Systems: Madison, WI, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Sheldrick G. M. Acta Crystallogr., Sect. A: Found. Crystallogr. 2008, 64, 112–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Po C.; Tam A. Y.-Y.; Wong K. M.-C.; Yam V. W.-W. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 12136–12143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Wong K. M.-C.; Yam V. W.-W. Acc. Chem. Res. 2011, 44, 424–434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Mascharak P. K.; Williams I. D.; Lippard S. J. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1984, 106, 6428–6430. [Google Scholar]; b Sakai K.; Tanaka Y.; Tsuchiya Y.; Hirata K.; Tsubomura T.; Iijima S.; Bhattacharjee A. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1998, 120, 8366–8379. [Google Scholar]; c Forniés J.; Fortuño C.; Ibáñez S.; Martín A. Inorg. Chem. 2006, 45, 4850–4858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Albinati A.; Balzano F.; de Biani F. F.; Leoni P.; Manca G.; Marchetti L.; Rizzato S.; Barretta G. U.; Zanello P. Inorg. Chem. 2010, 49, 3714–3720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Pasternack R. F.; Collings P. J. Science 1995, 269, 935–939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Leung S. Y.-L.; Yam V. W.-W. Chem. Sci. 2013, 4, 4228–4234. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.