Abstract

Objective

Acute stroke is a serious concern in Emergency Department (ED) dizziness presentations. Prior studies, however, suggest that stroke is actually an unlikely cause of these presentations. Lacking are data on short- and long-term follow-up from population-based studies to establish stroke risk after presumed non-stroke ED dizziness presentations.

Methods

From 5/8/2011 to 5/7/2012, patients ≥ 45 years of age presenting to EDs in Nueces County, Texas, with dizziness, vertigo, or imbalance were identified, excluding those with stroke as the initial diagnosis. Stroke events after the ED presentation up to 10/2/2012 were determined using the Brain Attack Surveillance in Corpus Christi (BASIC) study, which uses rigorous surveillance and neurologist validation. Cumulative stroke risk was calculated using Kaplan-Meier estimates.

Results

1,245 patients were followed for a median of 347 days (IQR 230- 436 days). Median age was 61.9 years (IQR, 53.8-74.0 years). After the ED visit, fifteen patients (1.2%) had a stroke. Stroke risk was 0.48% (95% CI, 0.22%-1.07%) at 2 days; 0.48% (95% CI, 0.22%-1.07%) at 7 days; 0.56% (95% CI, 0.27%-1.18%) at 30 days; 0.56% (95% CI, 0.27%-1.18%) at 90 days; and 1.42% (95% CI, 0.85%-2.36%) at 12 months.

Interpretation

Using rigorous case ascertainment and outcome assessment in a population-based design, we found that the risk of stroke after presumed non-stroke ED dizziness presentations is very low, supporting a non-stroke etiology to the overwhelming majority of original events. High-risk subgroups likely exist, however, because most of the 90-day stroke risk occurred within 2-days. Vascular risk stratification was insufficient to identify these cases.

Introduction

Dizziness is a common reason that patients present to the emergency department (ED).1, 2 In these presentations, substantial concern exists regarding central nervous system (CNS) causes, particularly ischemic stroke.3-5 In fact, public service campaigns about stroke urge patients with sudden dizziness to call for an ambulance.6, 7 Further reflecting increasing concern about CNS causes is the substantial rise in the use of head CT in ED dizziness visits over time.1, 8

Despite this substantial concern, large cross-sectional studies suggest that the proportion of acute dizziness presentations that are caused by stroke is low (around 3%), and is particularly low (0.7%) in the absence of accompanying CNS signs or symptoms.1, 2, 9, 10 However, it remains possible that the proportion of dizziness cases with cerebrovascular causes (stroke or TIA) may be higher than reported previously because posterior circulation vascular events are known to closely mimic a variety of other causes of dizziness and ischemic causes are usually missed by head CT. If stroke masquerading as a non-CNS disorder is common among acute dizziness presentations, then a high rate of stroke in the follow-up period – perhaps approaching the risk that occurs after a stroke or TIA (4.0% to 18.5% at 90 days)11-16 – would be expected.

Prior studies have assessed the risk of stroke in the time period after ED dizziness presentations.17-19 However these studies used retrospective designs, administrative databases, and International Classification of Diseases 9th edition (ICD-9) codes for case capture and outcome determination. The aim of the current study was to determine the cumulative risk of stroke after ED dizziness presentations using a cohort analysis nested within prospective, population-based studies of dizziness and stroke which apply several methods for optimal case capture and a validated method for stroke outcome determination.

Methods

Study design and Setting

The Dizziness Evaluation and Treatment in Corpus Christi, Texas (DETECT) project is an ED dizziness surveillance study in Nueces County, Texas. Patients presenting to any of the six adult care EDs in the county between May 8, 2011 and May 7, 2012 were identified. Corpus Christi makes up > 95% of the Nueces County population and is an urban environment on the Texas Gulf Coast. The population of the county is approximately 340,000.20 It is a non-immigrant community, with very little migration of individuals.21 Sixty-one percent of the population is Mexican American, 33% is non-Hispanic White, and 6% is of other racial-ethnic background.20 A substantial majority (89%) of Nueces county residents who live in a Spanish speaking household also speak English “very well” or “well”.20 There is no large academic medical center in Corpus Christi. In addition, the community is about 200 miles from Houston and 150 miles from San Antonio, and the surrounding counties are sparsely populated, allowing for complete case capture of acute disease. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the University of Michigan, the Corpus Christi hospitals, and the Texas Department of State Health Services (TDSHS).

Identification of Dizziness Visits

Adult patients aged ≥45 years presenting to the ED with dizziness symptoms were identified using both active and passive surveillance. Multiple methods of case capture were used to reduce selection bias. For active surveillance, trained research associates screened ED triage logs that were specifically designed for this study. The log contained clinical information regarding the patient’s reason for visit (RFV) as documented at initial encounter by ED staff and also the subjective assessment (SA) at the time of triage. RFV is typically a brief statement of chief complaint(s), whereas SA is typically written as a short narrative. Information is entered using free-text. Both of these data points were included because prior data assurance steps discovered that the initial RFV information could later be replaced with the diagnosis for admitted patients. The primary screen for active surveillance consisted of review of the RFV and SA sections for any of the following symptoms: dizziness, vertigo, or imbalance. For passive surveillance, two methods were used for case capture. First, an automated search of the ED administrative databases for dizziness-specific ICD-9 codes [780.4, 386.XX, 438.85, 781.2] recorded as principal or additional diagnoses was performed. Second, abstractors for the Brain Attack Surveillance in Corpus Christi (BASIC) project, an on-going surveillance study in this same community (see methods for BASIC below), searched for documentation of dizziness symptoms in visits meeting the BASIC criteria for stroke.

For all dizziness visits that were identified by active or passive surveillance, the ED physician record was reviewed. Dizziness was classified as a principal reason for the visit when the ED physician record had a dizziness symptom documented as one of the top three complaints or a dizziness diagnosis (e.g., dizziness not otherwise specified, vertigo not otherwise specified, benign positional vertigo, vestibular neuritis) was made. Exclusion criteria included out of county residents, institutionalized persons, dizziness caused by trauma, and dizziness that was not a principal reason for the visit.

For all visits with dizziness as a principal reason for the visit, information on demographics, history of present illness (HPI), past medical history (PMH), first recorded blood pressure, examination findings, diagnostic tests, diagnoses, consultations, and admission status was abstracted from the ED record. If not explicitly documented, HPI, PMH, examination, testing, and consultation items were considered not present or performed. The first recorded diagnosis on the ED physician note was considered the primary diagnosis. Neuro-imaging information was abstracted for studies performed in the ED or during a hospitalization that resulted from the ED visit.

Identification of Outcomes

Subsequent strokes among the DETECT subjects were identified through October 2, 2012 by merging the DETECT data with the data from the BASIC project. BASIC is an on-going stroke surveillance study conducted in Nueces County, Texas, since 2000. The methods of the BASIC project have been published previously.22 Briefly, cases of potential stroke among patients ≥45 years of age were captured by active and passive surveillance of all six hospitals in the county. Cases were ascertained actively by searching admission logs for a set of validated screening terms, and passively via ED and hospital discharge records using International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) discharge codes for stroke (codes 430-438, excluding codes 433.+ and 434.+0, where x = 1 to 9, 437.0, 437.2, 437.3, 437.4, 437.5, 437.7, 437.8, and 438). Validation of potential stroke cases was performed by board certified neurologists who reviewed ED and hospital source documentation and applied international criteria.23 DETECT and BASIC data were merged using Link Plus, a probabilistic record linkage program developed at the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Matching variables were first name, middle name, last name, date of birth, medical record number, zipcode, social security number, and gender. Manual review was used to determine match status for all potential matches. The location of the acute infarction was abstracted from the radiology report. The National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) was either recorded from the chart or abstracted using a previously validated approach based on the first documented physician examination.24

Deaths during the follow-up period were identified by merging dizziness visits captured in this study with a 2010-2012 Nueces County vital statistics database obtained from TDSHS. The databases were merged with the Link Plus program using the following variables: first name, middle name, last name, date of birth, zipcode, and gender. Manual review was used to determine match status for all potential matches.

Statistical Analysis

Demographic information, medical history, and stroke risk factors were summarized with percentages or medians and interquartile ranges (IQR), tabulated by stroke status during follow-up. Time to stroke in days was calculated by subtracting the DETECT presentation date from the date of the BASIC stroke presentation, with cases censored at death or on October 2, 2012, whichever came first. Cumulative risk for stroke after dizziness presentation was determined using the Kaplan-Meier product limit estimates. Excluded from the Kaplan-Meier analysis were cases validated as stroke for their index dizziness presentation, using ED and hospitalization records (if relevant), as our aim was to determine stroke risk among patients with a non-stroke dizziness event. In individuals with multiple dizziness presentations, only the first visit was used.

To explore whether clinical risk stratification may help identify patients at high risk of stroke, patients were categorized into levels of cerebrovascular risk using two separate schemes: the ABCD2 score and the Framingham Heart Study (FHS) stroke risk score.25, 26 Both schemes had to be modified in this study based on available data. The modified ABCD2 score was calculated for each subject by assigning points as follows: age 60 years or older = 1; systolic blood pressure ≥ 140 or diastolic blood pressure ≥ 90 = 1; clinical features (symptoms or exam findings of unilateral weakness =2, speech disturbance without weakness =1); and history of diabetes =1.25 The original ABCD2 score also assigned 0-2 points based on the duration of symptoms. Since symptom duration was not readily available from chart abstraction, we assigned each patient 2 points as has been done previously.27 The modified ABCD2 score was reported categorized as 0-3 (low), 4-5 (intermediate), or 6-7 (high).25

The FHS risk score algorithm was used to classify patients into long-term risk categories. 26 FHS is calculated by adding values assigned to the following risk factors which vary based on gender: age, systolic blood pressure (varying based on treatment status), diabetes, current smoking, cardiovascular disease (history of myocardial infarction, angina pectoris, coronary insufficiency, intermittent claudication, or congestive heart failure), atrial fibrillation, and left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) on electrocardiogram. We were not able to include a score for LVH because electrocardiograms were not collected. Patients in the current study were assumed to have treated blood pressure when a history of hypertension was documented. The cardiovascular disease variable was modified because we did not collect information on angina pectoris or intermittent claudication. The FHS stroke risk score was derived in a stroke free cohort so a prior history of stroke variable was not included. To account for a prior history of stroke in our population, we counted a past history of stroke as a component of the cardiovascular disease variable. Long-term cerebrovascular risk was then divided into categories of low (<10%), intermediate (10%-20%), and high-risk (>20%), as used previously,28 based on their estimated 10-year risk of stroke using the FHS algorithms.26 For these scales, HPI and PMH items were considered not present unless explicitly documented as present. The scheme scores were not calculated for patients with missing data.

All analyses were performed using Stata, version 12.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

Results

There were 5,004 dizziness visits identified between May 7, 2011 and May 6, 2012. Active surveillance captured 3,623 (72.4%) visits and passive surveillance captured 2,709 (54.1%) (1,328 of the visits were captured by both methods). Excluded were 1,958 visits due to age (i.e., age <45 years) and 223 that were not eligible (i.e., primary residence out of county, trauma, or institutionalized). An additional 1,465 visits were excluded because dizziness was not a principal symptom on the physician form (1,351), the patient left before being seen (77), or the records were missing or not available (37). Thus the final number of dizziness visits was 1,358, representing 1,273 unique individuals (85 repeat visits).

Of these 1,273 first captured dizziness cases, a validated stroke was the cause of the index presentation in 28 (2.2%; 95% CI, 1.5%-3.2%), of which 25 were ischemic and 3 were intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH). These 28 patients were excluded from subsequent analysis.

Characteristics of the final cohort of 1,245 patients with an index non-stroke dizziness event are presented in Table 1. Median age of the cohort was 61.8 years (interquartile range [IQR] 53.8-73.9) and 61.0% were female. A head CT was performed in 50.8%, and an MRI in 2.6%. Consultation with a neurologist was documented in 1.3% (16). A dizziness or vertigo symptom diagnosis was recorded in 80.8% (1,006) of the visits, and was the first listed diagnosis in 66.7% (830). A peripheral vestibular diagnosis was recorded in 7.9% (98) of the visits, and was the first listed diagnosis in 1.5% (19).

Table 1.

Patient demographic and clinical characteristics from the time of the emergency department presentation for dizziness, by subsequent stroke status.

| No Stroke During Follow-up N, %, unless otherwise specified N = 1,230 |

Stroke During Follow-up N, %, unless otherwise specified N = 15 |

|

|---|---|---|

| Age, median, IQR | 61.8 (53.7 to 73.7) | 72.4 (59.3 to 83.7) |

| Female | 750 (61.0%) | 9 (60.0%) |

| Ethnicity | ||

| Mexican American | 644 (52.4%) | 7 (46.7%) |

| Non-Hispanic White | 505 (41.1%) | 8 (53.3%) |

| Other | 81 (6.6%) | 0 (0%) |

| Systolic Blood Pressure in mmHg, median, IQRa | 147 (130 to 163) | 148 (143 to 160) |

| Hypertension | 728 (59.2%) | 8 (53.3%) |

| Diabetes | 343 (27.9%) | 7 (46.7%) |

| Cardiovascular disease b | 171 (13.9%) | 5 (33.3%) |

| Current smoker | 232 (18.9%) | 0 (0%) |

| Prior stroke | 85 (6.9%) | 6 (40.0%) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 45 (3.7%) | 1 (6.7%) |

| Modified ABCD2 score risk categories c | ||

| Low-risk | 588 (47.8%) | 3 (20.0%) |

| Intermediate-risk | 595 (48.4%) | 11 (73.3%) |

| High-risk | 11 (0.9%) | 1 (6.7%) |

| Long-term cerebrovascular risk categories d | ||

| Low-risk | 634 (53.1%) | 3 (20.0%) |

| Intermediate-risk | 311 (26.1%) | 8 (53.3%) |

| High-risk | 248 (20.8%) | 4 (26.7%) |

| Symptoms | ||

| Dizziness, any | 1,165 (94.7%) | 15 (100%) |

| Vertigo, any | 513 (41.7%) | 8 (53.3%) |

| Imbalance, any | 289 (23.5%) | 7 (46.7%) |

| More than 1 | 613 (49.8%) | 9 (60.0%) |

| Neuro-imaging Studies at Index Visit | ||

| Head CT | 620 (50.4%) | 12 (80.0%) |

| Head MRI | 29 (2.4%) | 2 (13.3%) |

| Neurologist Consultation | 16 (1.3%) | 0 (0%) |

| Number of Diagnoses, median IQR | 2 (2 to 3) | 2 (1 to 3) |

| First Listed Diagnosis | ||

| Dizziness or Vertigo NOS | 816 (66.3%) | 14 (93.3%) |

| Peripheral vestibular disorder | 19 (1.5%) | 0 (0%) |

| Other | 395 (32.1%) | 1 (6.7%) |

| Admitted to the hospital | 142 (11.5%) | 1 (6.7%) |

IQR, interquartile range; NOS, not otherwise specified; CT, computerized tomography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

Data missing for 36 visits.

Cardiovascular disease considered any of myocardial infarction, coronary artery disease, congestive heart failure.

Category not determined in 36 patients due to missing data.

Category not determined in 37 patients due to missing data.

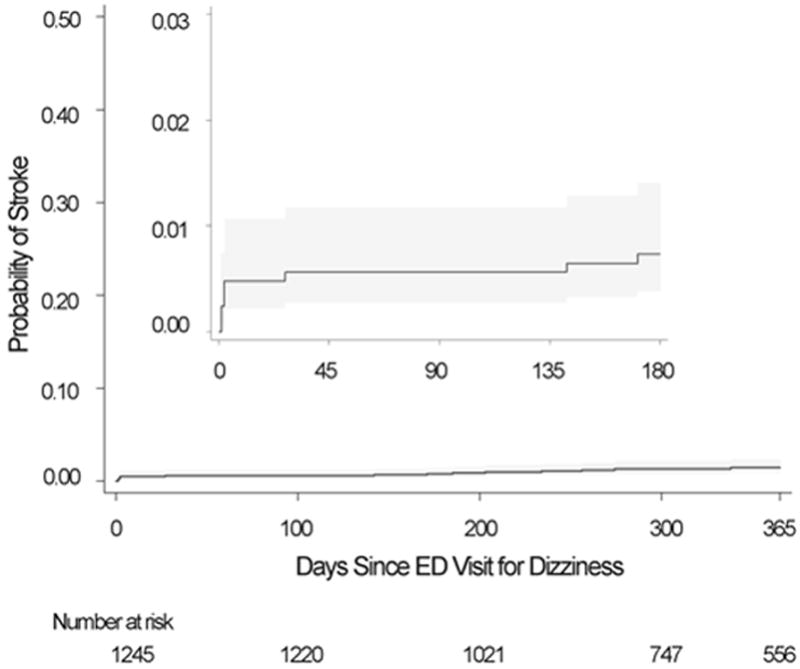

The median follow-up period was 347 days (IQR 231- 436 days). Of these 1,245 presumed non-stroke dizziness patients, 15 patients (1.2%; 95% CI, 0.7% to 2.0%) had a stroke identified during the follow-up period (15 ischemic stroke, 0 ICH). Median time to stroke was 142 days (IQR 2-234, range 1 to 338 days). Six of the 15 patients had the stroke event ≤2 days from the time of the index dizziness presentation. Stroke risk after dizziness presentation was 0.48% at 2 days; 0.48% at 7 days; 0.56% at 30 days; 0.56% at 90 days; 0.73% at 6 months; and 1.42% at 12 months (Table 2) (Figure). A majority (86%) of the 90-day risk occurred within 2 days. The overall incidence rate of stroke in the follow-up period was 13.2 per 1,000 person years (95% CI, 7.9 to 21.9).

Table 2.

Cumulative risk of validated stroke event after dizziness presentation to the emergency department. (N = 1,245)

| Cumulative Risk of Validated Stroke Event (95% CI) |

|

|---|---|

| 2-day | 0.48% (0.22%-1.07%) |

| 7-day | 0.48% (0.22%-1.07%) |

| 30-day | 0.56% (0.27%-1.18%) |

| 90-day | 0.56% (0.27%-1.18%) |

| 180-day | 0.73% (0.38%-1.41%) |

| 365-day | 1.42% (0.85%-2.37%) |

Figure 1.

Cumulative incidence curve depicting stroke risk after emergency department dizziness presentations. (Shaded areas represent 95%confidence intervals)

Stroke location based on imaging reports and other clinical details are presented in Table 3. Cerebellar, brainstem, or thalamic infarction location each occurred in one patient. Cerebrovascular risk categorization is reported in Table 1 and more specifically detailed for patients who had a subsequent stroke in Table 3. Stroke frequency in the low-risk categories was approximately 0.5% (3 of 637 for the modified ABCD2 score, and 3 of 591 for the long-term score). Of the six patients who had a stroke within 2 days, all were classified as intermediate-risk by the modified ABCD2 score. Overall, only 1 of the 15 strokes was classified as high-risk by the modified ABCD2 score and only 4 of the 15 by the long-term score.

Table 3.

Description of validated stroke cases that occurred in the time period following an emergency department dizziness presentation.

| Index Dizziness Visit | Subsequent Validated Stroke Visit | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient, age | Blood Pressure | Modified ABCD2 Category (Score) | Long-term Risk Category | Diagnoses | Time to Stroke, days | Imaging Results a | NIHSS score b |

| 1, ≥90 years c | 160/79 | Intermediate (4) | Intermediate | Dizziness/Vertigo, dehydration | 1 | HCT: NAD MRI: Acute infarct right frontal, left parietal |

4 |

| 2, 85 years | 147/65 | Intermediate (5) | High | Dizziness | 1 | HCT: NAD MRI: Acute infarct left frontal |

6 |

| 3, 62 years | 144/87 | Intermediate (5) | Intermediate | Dizziness, headache, diabetes mellitus, hyperglycemia | 1 | HCT: NAD MRI: Acute infarct left cerebellar peduncle |

0 |

| 4, 74 years | 148/75 | Intermediate (5) | High | Dizziness, vertigo acute, severe hyperglycemia, dehydration | 2 | HCT: NAD MRI: Acute to subacute infarct right parietal-occipital |

6 |

| 5, 59 years | 176/108 | Intermediate (4) | Intermediate | Dizziness, questionable aneurysm | 2 | HCT: NAD MRI: NAD by radiologist. Stroke pontomedullary junction by neurologist d |

2 |

| 6, 49 years | 209/93 | Intermediate (4) | Intermediate | Dizziness, orthostatsis, hypertensive urgency | 2 | HCT: not performed MRI: Acute infarct right temporal, right posterior limb. |

2 |

| 7, 83 years | 148/70 | Intermediate (5) | High | Dizziness, generalized weakness, chronic kidney disease, hyperkalemia, accidental overdose on sleep pills | 27 | HCT: Subacute to chronic right frontal infarct MRI: NAD. |

11 |

| 8, 53 years | 154/71 | Low (3) | Low | Dizziness, vertigo, hypothyroidism | 142 | HCT: NAD MRI: NAD |

7 |

| 9, 81 years | 146/63 | High (6) | High | Dizziness | 171 | HCT: NAD MRI: Acute infarct left MCA distribution |

27 |

| 10, 74 years | 160/87 | Intermediate (4) | Intermediate | Vertigo | 185 | HCT: NAD MRI: Acute infarct left temporal/parietal |

1 |

| 11, 88 years | 142/70 | Intermediate (4) | Intermediate | Dizziness/ vertigo acute | 203 | HCT: NAD MRI: Not performed |

17 |

| 12, 59 years | 130/70 | Low (2) | Low | Generalized weakness | 234 | HCT: NAD MRI: Not performed |

5 |

| 13, 60 years | 168/72 | Intermediate (4) | Intermediate | Vertigo, hyperglycemia | 256 | HCT: NAD MRI: Acute infarct left corona radiata |

3 |

| 14, 72 years | 103/43 | Low (3) | Low | Dizziness, hypotension | 274 | HCT: Age indeterminate left thalamus infarct MRI: Not performed |

2 |

| 15, 59 years | 143/75 | Intermediate (4) | Intermediate | Vertigo | 338 | HCT: NAD MRI: NAD |

3 |

HCT = head computerized tomography scan; MRI = magnetic resonance imaging scan of brain; NAD = no acute disease; NIHSS = National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale

As determined on final report by radiologist, unless otherwise indicated.

Median (Interquartile range) of NIHSS = 4 (2-7).

To protect patient identity, exact ages of persons 90+ are not reported.

Radiologist report stated no acute disease. Treating neurologist reported acute stroke on MRI.

Additional count data for the 6 patients with a stroke event within 2 days of the index presentation: female, 4; diabetes, 5; high cholesterol, 0; Mexican-American, 4; hypertension, 2; cardiovascular disease, 1; atrial fibrillation, 0; prior history of stroke, 2.

Discussion

This study found that stroke risk is low after an ED visit for dizziness that was presumed to be non-stroke in origin. Though prior studies have estimated a low proportion of stroke diagnosis at the time of a dizziness presentation,1, 2, 9, 10 the subsequent risk of stroke in the remaining patients has not been previously assessed using a cohort design with data collected from prospective, population-based surveillance studies and validated stroke classification methods.The very low subsequent risk of stroke in this study substantiates the prior cross-sectional studies that suggested a low prevalence of acute stroke as the cause of ED presentations of dizziness.

In addition to the population-based design, there were other advantages of this study compared with prior studies on this topic. First, we used multiple case capture methods. We searched for dizziness symptoms documented at two points early in the presentation process: the initial encounter and the triage assessment. Visits were also identified by searching administrative databases for dizziness specific ICD-9 codes listed as principal or additional diagnoses. Further, we reviewed the ED physician record of each captured visit to ensure that dizziness was a principal part of the presentation. Prior studies captured cases only using ICD-9 code databases without additional capture methods or manual review of the encounter.17-19 Multiple capture methods are necessary because patients with a primary symptom of dizziness receive a variety of ICD-9 diagnoses,1 and there is concern that some of these diagnoses (e.g., migraine, gastritis, encephalopathy, presyncope) could be misdiagnosed strokes.4 Another important advantage of our study was the rigorous surveillance for stroke events and the classification of all strokes using validated procedures including neurologist review of the medical records.

Compared with the previous California-based study on this topic,17 our estimate of stroke risk was somewhat higher (30-day risk of 0.56% compared with approximately 0.30% in Kim et al; 180-day risk of 0.73% versus 0.63% in Kim et al). Conversely, the risk in our study was somewhat lower than that from the Taiwan-based studies (180-day risk of 1.0%).18, 19 The confidence intervals in these studies overlap the point estimates, however, so the differences may be due to chance. A difference in the stroke risk in our population could result from our symptom based dizziness capture method, outcome validation method, or the characteristics of our population including patients ≥45 years of age and a high proportion of Mexican Americans who are at higher stroke risk than non-Hispanic whites.29

An important and consistent finding is that all of the studies reporting stroke risk after dizziness presentations have found that a large proportion of the risk occurs within a short period after the initial presentation. Both the California-based study and the Taiwan-based study found that this high proportion of the risk in the immediate time period was unique to stroke events because the same finding was not observed with cardiovascular outcomes.17, 19 The Taiwan-based study also found that this high proportion was unique to dizziness visits because the steep rise in stroke risk was not observed for non-dizziness visits.18, 19 This finding suggests that despite the overall low risk, a small subgroup of patients presenting with dizziness presumed to be non-stroke in etiology is likely at high short-term stroke risk. Although the relation of the ED dizziness visit to the stroke cannot be determined with certainty, the large proportion of events that occur within a short time period suggests the possibility that the index event in a small minority of cases was either a stroke or TIA masquerading as another disorder.

Identifying the dizziness patients at high risk is important, but prior studies found that age was the only variable associated with subsequent stroke.17, 19 Combinations of traditional risk factors may stratify the subsequent stroke risk in dizziness patients. 18 We had limited power to formally compare patients with and without stroke to try to identify those at highest risk, though we did explore the utility of using existing cerebrovascular risk classification schemes. In this study, none of the 6 patients who had a stroke within 2-days of the index presentation was in a low-risk category. This information may be useful to identify patients at very low risk of subsequent stroke, though additional validation studies are required. Identification of those at high risk remains a challenge, since about half of the population was categorized as intermediate to high risk by the risk stratification aids. Thus, our study corroborates prior studies indicating that current risk stratification methods do not adequately identify a high-risk group.27, 30 Therefore, more nuanced approaches, perhaps incorporating more details regarding specific eye movement findings in patients with active symptoms, may be necessary.30, 31 However, these prior studies suggesting that eye movement findings can identify high risk subjects used neurology specialists to perform or interpret the examination.30, 31 Neurologist consultation is likely to be infrequent in routine care settings, as it was in our community, and therefore this strategy may not be feasible for widespread use. An additional challenge to developing decision support in dizziness presentations is that the number of outcome events is very small, so that future work validating assessment tools will need large sample sizes.

Our study provides detail about the findings on neuro-imaging studies that were obtained at the subsequent stroke visits. In dizziness presentations, it is likely that the most feared causes or future events are specifically a basilar artery occlusion or a large cerebellar stroke that could result in herniation. However, we found that only 3 of the 15 subsequent strokes had acute cerebrovascular lesions of the cerebellum, brainstem, or thalamus on imaging studies. Though posterior circulation strokes could be under recognized and caution in drawing conclusions is advised based on the low number of strokes in this study, these findings indicate that the subsequent risk of a cerebellar, brainstem, or thalamic stroke is much less than the overall risk of stroke in this population. The risk would therefore be even lower for the subsequent occurrence of a basilar artery occlusion or a large cerebellar stroke resulting in herniation. The findings regarding the relatively lower occurrence of posterior circulation strokes also suggests that either most of the subsequent strokes are not related to the index dizziness presentation or, if related, that the dizziness stemmed from anterior circulation ischemia or a separate posterior circulation ischemic event related to the subsequent stroke by mechanism (e.g., cardioembolism).

The population in this study had a higher proportion of visits with a dizziness or vertigo symptom diagnosis compared with a prior national sample of ED dizziness visits (80.8% versus 20%), and a slightly higher proportion of visits that received a peripheral vestibular diagnosis (7.9% versus 6.1%).1 These differences may relate to several factors including the prior study’s limitation on the number of diagnoses abstracted from the medical record, our multiple methods to capture cases using symptoms or ICD-9 codes, and the additional criteria we used to focus the population on patients with principal dizziness. The EDs in the current study also use template documentation systems for the physician report which could influence the diagnoses recorded.

Limitations

The population was limited to patients age 45 years and older. Inclusion of younger adults could have increased the absolute number of subsequent strokes identified but would have likely lowered the cumulative incidence of subsequent stroke because of the lower stroke risk in younger people. It is possible that some dizziness encounters were missed if the symptoms were not conveyed or documented effectively. It is unlikely that a substantial number of dizziness cases were missed due to a language barrier because most (89%) of the Nueces county residents who live in a Spanish speaking household also speak English “very well” or “well”.20 Since any missed dizziness visits may or may not have had a subsequent stroke, it is not possible to determine the direction of this ascertainment bias. The stroke classification in this study was based on the application of validated stroke criteria by study investigators who reviewed source documents. It is possible that we missed or misclassified stroke patients, either at the index visit or a subsequent visit, if the medical evaluation, or documentation of the evaluation, was not sufficient to meet the criteria of our study. It is possible that posterior circulation strokes are more likely to be misclassified than anterior circulation strokes.32 It is also possible that we missed strokes in patients who did not present to a Nueces County ED for medical attention, though prior research suggests very few out-of-hospital strokes occur in this community.29 The proportion of patients receiving a CT scan at the dizziness visit was high. This factor may have impacted the identification of ICH cases. However, it is unlikely that it impacted overall acute stroke frequency since CT is an insensitive test for ischemic stroke, the most common stroke type.33 Based on available data, we needed to modify the ABCD2 and FHS stroke risk scoring schemes, and thus these were no longer considered validated estimators of actual risk. The cerebrovascular risk scoring methods did not include information regarding current use of antiplatelet or anticoagulant medications. Case selection may have been overly inclusive resulting in lower stroke risk estimates. Cases were not excluded from the main analysis for any diagnoses other than acute stroke for the following reasons: the validity of other diagnoses was uncertain, other common diagnoses do not preclude a patient from also having a stroke, and posterior circulation stroke is known to masquerade as a variety of other disorders.4, 34

Conclusions

The risk of stroke after acute presentations for presumed non-stroke dizziness is low. The low risk supports a non-stroke etiology to the original dizziness event in the overwhelming majority of cases. However, high-risk subgroups exist in this patient population. Efficient and effective clinical tools that physicians can use to estimate the risk of stroke in individual patients presenting with dizziness are needed for accurate bedside stroke risk assessments.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH K23RR024009, NIH R01NS038916, NIH R01HL098065, and NIH R01NS070941

References

- 1.Kerber KA, Meurer WJ, West BT, Fendrick AM. Dizziness presentations in U.S. emergency departments, 1995-2004. Acad Emerg Med. 2008;15:744–750. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2008.00189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Newman-Toker DE, Hsieh YH, Camargo CA, Jr, Pelletier AJ, Butchy GT, Edlow JA. Spectrum of dizziness visits to US emergency departments: cross-sectional analysis from a nationally representative sample. Mayo Clin Proc. 2008;83:765–775. doi: 10.4065/83.7.765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eagles D, Stiell IG, Clement CM, et al. International survey of emergency physicians’ priorities for clinical decision rules. Acad Emerg Med. 2008;15:177–182. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2008.00035.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Savitz SI, Caplan LR, Edlow JA. Pitfalls in the diagnosis of cerebellar infarction. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14:63–68. doi: 10.1197/j.aem.2006.06.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.D’Onofrio G, Jauch E, Jagoda A, et al. NIH Roundtable on Opportunities to Advance Research on Neurologic and Psychiatric Emergencies. Ann Emerg Med. 2010;56:551–564. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2010.06.562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.American Stroke Association. [online]. Available at: http://www.strokeassociation.org/STROKEORG/WarningSigns/Warning-Signs_UCM_308528_SubHomePage.jsp.

- 7.Suspect A Stroke? Act FAST. Call 999. FAST A5 leaflet [online] Available at: http://www.stroke.org.uk/information/about_stroke/recognising_symptoms/index.html.

- 8.Saber Tehrani AS, Coughlan D, Hsieh YH, et al. Rising annual costs of dizziness presentations to U.S. emergency departments. Academic emergency medicine : official journal of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. 2013;20:689–696. doi: 10.1111/acem.12168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kerber KA, Brown DL, Lisabeth LD, Smith MA, Morgenstern LB. Stroke among patients with dizziness, vertigo, and imbalance in the emergency department: a population-based study. Stroke. 2006;37:2484–2487. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000240329.48263.0d. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Navi BB, Kamel H, Shah MP, et al. Rate and predictors of serious neurologic causes of dizziness in the emergency department. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87:1080–1088. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2012.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burn J, Dennis M, Bamford J, Sandercock P, Wade D, Warlow C. Long-term risk of recurrent stroke after a first-ever stroke. The Oxfordshire Community Stroke Project. Stroke. 1994;25:333–337. doi: 10.1161/01.str.25.2.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coull AJ, Lovett JK, Rothwell PM. Population based study of early risk of stroke after transient ischaemic attack or minor stroke: implications for public education and organisation of services. Bmj. 2004;328:326. doi: 10.1136/bmj.37991.635266.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lisabeth LD, Ireland JK, Risser JM, et al. Stroke risk after transient ischemic attack in a population-based setting. Stroke. 2004;35:1842–1846. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000134416.89389.9d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moroney JT, Bagiella E, Paik MC, Sacco RL, Desmond DW. Risk factors for early recurrence after ischemic stroke: the role of stroke syndrome and subtype. Stroke. 1998;29:2118–2124. doi: 10.1161/01.str.29.10.2118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Johnston SC, Gress DR, Browner WS, Sidney S. Short-term prognosis after emergency department diagnosis of TIA. Jama. 2000;284:2901–2906. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.22.2901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ois A, Gomis M, Rodriguez-Campello A, et al. Factors associated with a high risk of recurrence in patients with transient ischemic attack or minor stroke. Stroke. 2008;39:1717–1721. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.505438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim AS, Fullerton HJ, Johnston SC. Risk of vascular events in emergency department patients discharged home with diagnosis of dizziness or vertigo. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;57:34–41. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2010.06.559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee CC, Su YC, Ho HC, et al. Risk of stroke in patients hospitalized for isolated vertigo: a four-year follow-up study. Stroke. 2011;42:48–52. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.597070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee CC, Ho HC, Su YC, et al. Increased risk of vascular events in emergency room patients discharged home with diagnosis of dizziness or vertigo: a 3-year follow-up study. PLoS One. 2012;7:e35923. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.United States Census Bureau. [1/15/2014];American Fact Finder [online] Available at: http://factfinder2.census.gov/faces/nav/jsf/pages/index.xhtml.

- 21.Morgenstern LB, Steffen-Batey L, Smith MA, Moye LA. Barriers to acute stroke therapy and stroke prevention in Mexican Americans. Stroke. 2001;32:1360–1364. doi: 10.1161/01.str.32.6.1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morgenstern LB, Smith MA, Sanchez BN, et al. Persistent Ischemic stroke disparities despite declining incidence in mexican americans. Annals of neurology. 2013 doi: 10.1002/ana.23972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gillum RF, Fortmann SP, Prineas RJ, Kottke TE. International diagnostic criteria for acute myocardial infarction and acute stroke. Am Heart J. 1984;108:150–158. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(84)90558-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Williams LS, Yilmaz EY, Lopez-Yunez AM. Retrospective assessment of initial stroke severity with the NIH Stroke Scale. Stroke. 2000;31:858–862. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.4.858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnston SC, Rothwell PM, Nguyen-Huynh MN, et al. Validation and refinement of scores to predict very early stroke risk after transient ischaemic attack. Lancet. 2007;369:283–292. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60150-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.D’Agostino RB, Wolf PA, Belanger AJ, Kannel WB. Stroke risk profile: adjustment for antihypertensive medication. The Framingham Study. Stroke. 1994;25:40–43. doi: 10.1161/01.str.25.1.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Navi BB, Kamel H, Shah MP, et al. Application of the ABCD2 score to identify cerebrovascular causes of dizziness in the emergency department. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2012;43:1484–1489. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.646414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wilson PW, Nam BH, Pencina M, D’Agostino RB, Sr, Benjamin EJ, O’Donnell CJ. C-reactive protein and risk of cardiovascular disease in men and women from the Framingham Heart Study. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165:2473–2478. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.21.2473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morgenstern LB, Smith MA, Lisabeth LD, et al. Excess stroke in Mexican Americans compared with non-Hispanic Whites: the Brain Attack Surveillance in Corpus Christi Project. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;160:376–383. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Newman-Toker DE, Kerber KA, Hsieh YH, et al. HINTS outperforms ABCD2 to screen for stroke in acute continuous vertigo and dizziness. Academic emergency medicine : official journal of the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine. 2013;20:986–996. doi: 10.1111/acem.12223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Newman-Toker DE, Saber Tehrani AS, Mantokoudis G, et al. Quantitative video-oculography to help diagnose stroke in acute vertigo and dizziness: toward an ECG for the eyes. Stroke; a journal of cerebral circulation. 2013;44:1158–1161. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.000033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kuruvilla A, Bhattacharya P, Rajamani K, Chaturvedi S. Factors associated with misdiagnosis of acute stroke in young adults. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2011;20:523–527. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2010.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chalela JA, Kidwell CS, Nentwich LM, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography in emergency assessment of patients with suspected acute stroke: a prospective comparison. Lancet. 2007;369:293–298. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60151-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Edlow JA, Newman-Toker DE, Savitz SI. Diagnosis and initial management of cerebellar infarction. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7:951–964. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70216-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]