Abstract

Adolescence is a period of heightened vulnerability for the onset of internalizing psychopathology. Characterizing developmental patterns of symptom stability, progression, and co-occurrence is important in order to identify adolescents most at risk for persistent problems. We use latent growth curve modeling to characterize developmental trajectories of depressive symptoms and four classes of anxiety symptoms (separation anxiety, social phobia, GAD, and physical anxiety) across early adolescence, prospective associations of depression and anxiety trajectories with one another, and variation in trajectories by gender. A diverse sample of early adolescents (N=1065) was assessed at three time points across a one-year period. All classes of anxiety symptoms declined across the study period and depressive symptoms remained stable. In between-individual analysis, adolescents with high levels of depressive symptoms experienced less decline over time in symptoms of physical, social, and separation anxiety. Consistent associations were observed between depression and anxiety symptom trajectories within-individuals over time, such that adolescents who experienced a higher level of a specific symptom type than would be expected given their overall symptom trajectory were more likely to experience a later deflection from their average trajectory in other symptoms. Within-individual deflections in physical, social, and GAD symptoms predicted later deflections in depressive symptoms, and deflections in depressive symptoms predicted later deflections in separation anxiety and GAD symptoms. Females had higher levels of symptoms than males, but no evidence was found for variation in symptom trajectories or their associations with one another by gender or by age.

Keywords: adolescence, anxiety, depression, development, trajectories, growth curve model

Adolescence is a period of heightened vulnerability for the onset of internalizing psychopathology. The prevalence of depression is only 2.8% in children under the age of 13 and doubles to 5.6% among adolescents aged 13–18 (Costello, Erkanli, & Angold, 2006). The incidence of major depression peaks between the ages of 15 and 18 (Hankin et al., 1998), and an increase in rates of depressive symptoms among females occurs between the ages of 13 and 15 (Nolen-Hoeksema & Girgus, 1994; Twenge & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2002). The gender difference in depression is first observable during the early adolescent period and becomes pronounced by late adolescence (Hankin et al., 1998). Onset of many anxiety disorders also occurs during this time period, including social anxiety disorder, panic disorder, and generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) (Beesdo et al., 2007; Cambell, Brown, & Grisham, 2003; Last, Perrin, Hersen, & Kazdin, 1992; Wittchen, Kessler, Pfister, & Lieb, 2000). Adolescent anxiety disorders and depression portend a wide range of negative consequences across the life-course, including risk of recurrent episodes in adulthood (Copeland, Shanahan, Costello, & Angold, 2009; Fombonne, Wostear, Cooper, Harrington, & Rutter, 2001a; Pine, Cohen, Gurley, Brook, & Ma, 1998), suicidality (Brent et al., 1993; Fombonne, Wostear, Cooper, Harrington, & Rutter, 2001b), and poor psychosocial functioning (Fombonne et al., 2001b; Gotlib, Lewinsohn, & Seeley, 1998). Sub-threshold symptoms of anxiety and depression are also associated with heightened risk of later psychopathology (Fergusson, Horwood, Ritter, & Beautrais, 2005; Georgiades, Lewinsohn, Monroe, & Seeley, 2006; Pine, Cohen, Cohen, & Brook, 1999).

Although adolescence is a period of vulnerability for internalizing psychopathology, most adolescents do not become clinically anxious or depressed. Characterizing developmental patterns of symptom stability, progression, and co-occurrence is important in order to identify adolescents most at risk for persistent problems. In a five-year prospective study of adolescents followed from age 10 to 18, Hale and colleagues (2008) found evidence for decreases in symptoms of panic disorder, separation anxiety, GAD, and phobias, with the exception of social phobia symptoms which remained relatively constant (Hale, Raaijmakers, Muris, van Hoof, & Meeus, 2008). Similar findings have been in observed in several prospective community studies, indicating that most types of anxiety symptoms decrease across early to middle adolescence (Burstein, Ginsburg, Petras, & Ialongo, 2010; Crocetti, Klimstra, Keijsers, Hale, & Meeus, 2009; Van Oort, Greaves-Lord, Verhulst, Ormel, & Huizink, 2009). In contrast, symptoms of depression increase developmentally across this period, particularly for girls (Ge, Conger, & Elder, 2001; Twenge & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2002; Van Oort et al., 2009), suggesting that anxiety and depression symptoms follow different developmental trajectories during adolescence.

These divergent patterns are perplexing, because symptoms of anxiety and depression are highly co-occurring, and both concurrent and sequential comorbidity between anxiety disorders and major depression are common in children and adolescents (Angold, Costello, & Erkanli, 1999; Wittchen et al., 2000). This raises important questions about the relationship between symptoms of anxiety and depression during adolescence. Numerous studies have attempted to disentangle the temporal sequencing of anxiety and depression using a cross-lagged approach to examine whether the presence of anxiety predicts subsequent increases in depression, whether the presence of depression predicts subsequent increases in anxiety, or both. Virtually all of these studies find that children and adolescents with an anxiety disorder are at elevated risk for the onset of major depression and that prediction from anxiety to depression is stronger than the reverse (Costello, Mustillo, Erkanli, Keeler, & Angold, 2003; Merikangas et al., 2003; Pine et al., 1998; Wittchen et al., 2000). Similar findings have been observed in studies that examine cross-lagged associations between anxiety and depression symptoms. For example, Cole (1998) found that symptoms of anxiety at one time point predicted increases in depressive symptoms at a subsequent time point, but depressive symptoms did not predict increases in anxiety in a sample of third- and sixth-grade children (Cole, Peeke, Martin, Truglio, & Seroczynski, 1998). However, beginning in adolescence major depression is associated in some studies with future onset of anxiety disorders (Fergusson & Woodward, 2002; Kim-Cohen et al., 2003), and specifically predicts future onset of GAD (Moffit, Harrington, et al., 2007; Pine et al., 1998). Bidirectional associations between anxiety and depression symptom trajectories have also been observed during adolescence, such that adolescents with increasing symptoms of anxiety tend to exhibit increasing symptoms of depression across time, and vice versa (Hale, Raaijmakers, Muris, van Hoof, & Meeus, 2009; Leadbeater, Thompson, & Gruppuso, 2012).

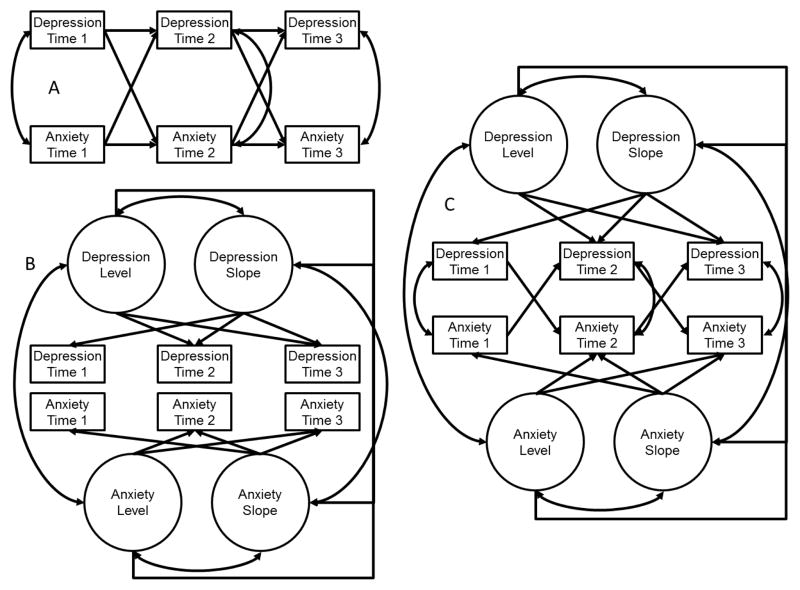

Prior studies have utilized diverse methods for examining the prospective association between anxiety and depression. For example, Cole et al. (1998) tested an auto-regressive cross-lagged panel model, which tested how anxiety and depression at one time point predicted anxiety and depression at the next time point. This model presumes that associations between anxiety and depression occur as a result of a cascading, point-to-point process, such that change in anxiety at a later time point is related to prior status in depression (over and above prior level of anxiety), or vice versa. On the other hand, Hale and colleagues (2009) and Leadbeater and colleagues (2012) tested associations between latent trajectories of anxiety and depression with parallel process growth curve models, which take the same repeated observations of anxiety and depression that could be used in a cross-lagged panel model as indicators of an unobserved latent developmental trajectory. This model assumes that associations between anxiety and depression occur as a result of larger developmental processes, and that anxiety influences depression either because the level of one is associated with the rate of development in the other, or because the rates of development in both are correlated. However, both of these approaches have limitations. Auto-regressive models do not distinguish between and within-individual variance, which means that associations between variables represent a mixture of between-individual differences in symptoms (i.e. because some adolescents have higher anxiety than others over time in general), and within-individual differences (i.e. how deviations from an adolescent’s typical anxiety symptoms influence later depression). Parallel process growth models focus only on between-individual differences in symptom associations, and ignore within-individual associations.

We argue that examining within-individual associations is equally important as examining between-individual associations. It is often of interest to not only understand for whom symptoms change, but also when are they expected to change and why. Frequently, decisions about when to intervene are drawn from between-individual studies. For example, a trajectory studies might show that higher baseline social anxiety is associated with increases in depressive symptoms over time, and an intervention might be developed to reduce social anxiety as a means of preventing increases in depression. However, such studies are making conclusions about within-individual processes (i.e. that decreasing social anxiety will reduce depressive symptoms) from between-individual data. However, within-individual analyses that examine how associations vary across time within the same individual provide an opportunity to examine these types of questions more directly (Fleeson, 2007). Auto-regressive latent trajectory models (also called ALT models) allow researchers to simultaneously test hypotheses about between- and within-individual differences in change over time (Bollen & Curran, 2004; Curran & Hussong, 2003). In other words, they may be used to test whether between-individual differences in the level of anxiety or depression influences the rate of change in the other, as well as how within-individual differences in point-to-point levels of each are associated over time. Prior research has demonstrated the utility of these types of models to examine how environmental or behavioral factors predict trajectory deflections in psychopathology (e.g., King, Molina, & Chassin, 2009). Although prior studies have examined latent trajectory models to identify groups of adolescents who follow similar patterns of anxiety disorder and major depression comorbidity over time (Olino, Klein, Lewinsohn, Rohde, & Seeley, 2010) as well as latent growth models to determine how between-individual differences in anxiety and depression symptom trajectories are associated with one another (Hale et al., 2009; Leadbeater et al., 2012), we are unaware of studies that have examined both the between-individual and within-individual associations of symptom trajectories with one another. Thus our study was designed to compare these approaches (i.e., approaches examining only between-individual effects, including an autoregressive cross-lagged panel model and a parallel process growth curve model, and the ALT model which examines both between- and within-individual effects) to studying change over time in anxiety and depression in early adolescence. Characterizing anxiety and depression symptom trajectories and their associations with one another over time is a necessary first step before substantive predictors of between- and within-individual differences in these trajectories can be identified.

Importantly, trajectories of anxiety and depression symptoms in early adolescence, as well as their associations with one another, may differ by gender. Evidence from several prospective community studies suggests that cross-lagged associations between anxiety disorders and major depression are stronger for females than males. The continuity of depression, GAD, social phobia, and specific phobia was significantly greater for females than males from age 9 to 16 in the Great Smoky Mountain Study (Costello et al., 2003). Moreover, the presence of an anxiety disorder predicted subsequent onset of depression, and the presence of depression predicted later onset of anxiety disorder across this age range, but only for females (Costello et al., 2003). In the Dunedin Study, strong continuity was observed between internalizing disorders at age 11 and age 15 for females but not males (McGee, Feehan, Williams, & Anderson, 1992). A similar pattern was found in a longitudinal community study of late adolescents and early adults, such that the association between anxiety and later onset of depression and between depression and later onset of anxiety was stronger for females than males (Merikangas et al., 2003). Existing evidence thus suggests stronger continuity and symptom progression of anxiety and depression for females than males. However, we are unaware of previous research examining gender differences in the relationship between symptom trajectories, particularly during the early adolescent risk period.

We address this gap in the literature using data from a three-wave prospective study of early adolescents. First, we examine developmental trajectories of depressive symptoms and four classes of anxiety symptoms (separation anxiety, social phobia, GAD, and physical anxiety) across early adolescence. Second, we examine how trajectories of anxiety symptoms are related to trajectories of depressive symptoms and whether these relationships vary across anxiety symptom types. We examine three modeling approaches for characterizing longitudinal associations between symptoms of depression and anxiety: auto-regressive, parallel process, and ALT models. Finally, we investigate gender differences in trajectories of anxiety and depressive symptoms and in the co-variation of symptom trajectories.

Method

Participants

Adolescents were recruited from the total enrollment of two middle schools (Grades 6–8; ages 10–15) in a small, urban community in central Connecticut with the exception of students in self-contained special education classrooms and technical programs who did not attend school for the majority of the day. The parents of all eligible children (N = 1,567) in the participating middle schools were asked to provide active consent for their children to participate in the study. Parents who did not return written consent forms to the school were contacted by telephone. We received IRB permission to obtain verbal consent from parents over the phone for their child to participate in the study, as this was the only feasible method for obtaining active parental consent. No differences were observed between children whose parents returned the consent form compared to those who provided verbal consent. Twenty-two percent of parents did not return consent forms and could not be reached to obtain consent, and 6% of parents declined to provide consent. All youths provided assent for participation. The overall participation rate in the study at Time 1 was 72% (N = 1,065). Of participants who were present at Time 1, 217 (20.4%) did not participate at the Time 2 assessment, and 330 (31.0%) did not participate at Time 3, largely due to transient student enrollment in this district. Data from the school district indicate that over the 4-year period from 2000–2004, 22.7% of students had left the district (Connecticut Department of Education, 2006). An additional 121 participants were present at the Time 2 assessment and 40 at the Time 3 assessment who did not participate at Time 1. The total sample at each wave is as follows: Time 1 (N=1,065), Time 2 (N=1,034), Time 3 (N=811). Of these, 1,437 had data on anxiety or depression from at least one observation and were included in analyses.

The Time 1 sample included 51.2% (N = 545) boys and 48.8% (N = 520) girls. Participants were evenly distributed across grade level (mean age = 12.2, SD = 1.0). The race/ethnicity composition of the sample was as follows: 13.2% (N = 141) non-Hispanic White, 11.8% (N = 126) non-Hispanic Black, 56.9% (N = 610) Hispanic/Latino, 2.2% (N = 24) Asian/Pacific Islander, 0.2% (N = 2) Native American, 0.8% (N = 9) Middle Eastern, 9.3% (N = 100) Biracial/Multiracial and 4.2% (N = 45) Other racial/ethnic groups. Twenty-seven percent (N = 293) of participants reported living in single-parent households. The community in which the participating middle schools reside is relatively low SES, with a per capita income of $18,404 (Connecticut State Department of Education, 2005 based on data from 2001). School records indicated that 62.3% of students qualified for free or reduced lunch in the 2004–2005 school year. There were no differences across the two schools in demographic variables.

Measures

Anxiety symptoms

Anxiety symptoms were assessed using the Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC; March, Parker, Sullivan, Stallings, & Conners, 1997) and the Penn State Worry Questionnaire for Children (PSWQ; Chorpita, Tracey, Brown, Collica, & Barlow, 1997). The MASC is a 39-item widely used measure of anxiety in children. The MASC assesses physical symptoms of anxiety, harm avoidance, social anxiety, and separation anxiety and is appropriate for children ages 8 to 19. Each item presents a symptom of anxiety, and participants indicate how true each item is for them on a four-point Likert scale ranging from never true (0) to very true (3). The MASC has high internal consistency and test-retest reliability across 3-month intervals, and established convergent and divergent validity (Muris, Merckelbach, Ollendick, King, & Bogie, 2002). The MASC sub-scales demonstrated good reliability in this sample for physical symptoms (α = 0.78) and social anxiety (α = 0.81) and demonstrated adequate reliability for separation anxiety (α = 0.68).

The PSWQ-C is a 14-item measure that assesses the frequency, severity, and controllability of worry. Items are rated on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from never true (0) to always true (3), with higher scores reflecting greater engagement in worry. This measure was adapted from the adult version of the PSWQ (Meyer, Miller, Metzger, & Borkovec, 1990) and demonstrates sound psychometric properties, including high internal consistency, excellent test-retest reliability and high convergent and discriminant validity (Chorpita et al., 1997). The PSWQ-C successfully differentiates children with GAD from children without anxiety or mood disorders (Chorpita et al., 1997) and demonstrated good reliability in this sample (α = 0.85).

Depressive symptoms

The Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI; Kovacs, 1992) is a widely used self-report measure of depressive symptoms in children and adolescents. The CDI includes 27 items consisting of three statements (e.g., I am sad once in a while, I am sad many times, I am sad all the time) representing different levels of severity of a specific symptom of depression. The CDI has sound psychometric properties, including internal consistency, test-retest reliability, and discriminant validity (Kovacs, 1992; Reynolds, 1994). The item pertaining to suicidal ideation was removed from the measure at the request of school officials and the Institutional Review Board (IRB). The 26 remaining items were summed to create a total score ranging from 0 to 52. The CDI demonstrated good reliability in this sample (α = .82).

Procedure

Participants completed study questionnaires during their homeroom period. Seven months elapsed between the Time 1 (November 2005) and Time 2 (June 2006) assessments, and an additional 5 months elapsed between Time 2 and Time 3 (November 2006) assessments. Participants who contributed data at any time point were included in the data analysis, and missing data were handled during model estimation (see Analytic Strategy for details). Participants were assured of the confidentiality of their responses and the voluntary nature of their participation. The study was approved by the IRB at Yale University.

Analytic Strategy

All analyses were conducted using MPlus 6.1 (Muthén & Muthén, 2008a) with the MLR estimator, accounting for missing data by using full information maximum-likelihood estimation (FIML) (Little & Rubin, 1987). FIML utilizes all available data, rather than the covariance matrix, to obtain parameter estimates. It is superior to complete case analysis because it provides superior power to detect effects due to the increased sample size, and is robust to missing data when data are missing at random (Schafer & Graham, 2002). To test whether varying permutations of each model improved model fit, we used Satorra’s chi-square difference tests for MLR chi-square (Satorra, 2000). In terms of assessing model fit, researchers frequently cite Hu & Bentler (Hu & Bentler, 1999) as providing rules for model fit, when their work more appropriately provides a starting point for determining adequate model fit (Marsh, Hau, & Wen, 2004). There has been robust debate about how to utilize different relative fit indices to determine whether a structural equation model reproduces the covariance matrix (Barrett, 2007; Millsap, 2007). Moreover, recent research has suggested that even the more stringent relative criteria suggested by Hu & Bentler (1999), such as RMSEA < .05, can suggest that a model is well-fitting even when it is not (Chen, Curran, Bollen, Kirby, & Paxton, 2008). Thus we assessed model fit using a combination of chi-square, relative fit indices (including the Tucker Lewis Index (TLI), comparative fit index (CFI), the root-mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), the Bayseian Information Criteria (BIC), model residuals, and model modification indices.

We analyzed the associations between anxiety and depression symptoms in four series of models, one for each class of anxiety symptoms (GAD, physical symptoms, separation anxiety, and social anxiety). Model fitting proceeded as follows. First, we first estimated unconditional growth curve models to understand how symptoms of anxiety and depression changed across the year of assessments. Next, we estimated a series of bivariate models to understand how anxiety and depression symptoms covaried across time. The first model was an autoregressive cross-lagged panel model, with the cross-lagged associations first fixed, and then freed across time. Next we tested a parallel process growth curve model, with the intercept fixed to Time 1. Finally, we tested an ALT model (Bollen & Curran, 2004), which added cross-lagged associations among the residual variances. We did not add auto-regressive associations among the residuals because not all authors agree that these are necessary, in part because these effects imply some change process over and above what is captured by the latent growth trajectory (Voelkle, 2008). We compared these models to determine which produced the best fit to the data. Then we added gender, and single-parent household status to the final model to control for their effects on the model, and added age to control for cohort effects and tested whether the estimated parameters in each final model were equal across gender using the Wald test for parameter constraints.

Results

Attrition

Analyses comparing participants who completed all assessments to those who did not revealed that participants who completed the Time 1 but not the Time 2 assessment were more likely to be female, χ(1)2 = 6.85, p < .01, and from a single-parent household, χ(1)2 = 8.93, p < .01, but did not differ in grade level, race/ethnicity, Time 1 anxiety, or Time 1 depression (p-values > 0.10) from those who completed both assessments. Participants who were lost to follow-up by the Time 3 assessment were more likely to be from a single-parent household, χ(1)2 = 26.92, p < .001, and had higher Time 1 symptoms of depression, F(1, 1065) = 9.63, p = .002, than adolescents who were present at all three assessments but did not differ in gender, race/ethnicity, or Time 1 anxiety symptoms.

Descriptive statistics

The means and standard deviations of each type of anxiety symptom and depressive symptoms are shown in Table 1, separately for males and females.

Table 1.

Means and standard deviations of anxiety and depressive symptoms by gender.

| Total Sample | Males | Females | Gender Difference | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | t-value | |

| Time 1 | |||||||

| Depressive Symptoms | 9.67 | (6.44) | 9.11 | (6.37) | 10.25 | (6.47) | 2.88* |

| GAD Symptoms | 14.62 | (7.38) | 13.12 | (6.84) | 16.10 | (7.61) | 6.50* |

| Social Anxiety Symptoms | 8.48 | (5.63) | 7.22 | (5.31) | 9.83 | (5.67) | 7.75* |

| Separation Anxiety Symptoms | 6.61 | (4.51) | 5.71 | (4.20) | 7.56 | (4.64) | 6.80* |

| Physical Anxiety Symptoms | 9.22 | (5.64) | 8.25 | (5.36) | 10.25 | (5.77) | 5.88* |

| Time 2 | |||||||

| Depressive Symptoms | 10.64 | (8.15) | 9.70 | (8.18) | 10.73 | (7.74) | 1.90+ |

| GAD Symptoms | 14.20 | (7.21) | 12.85 | (6.94) | 15.03 | (7.33) | 4.37* |

| Social Anxiety Symptoms | 7.55 | (5.96) | 6.26 | (5.69) | 8.67 | (5.95) | 6.05* |

| Separation Anxiety Symptoms | 5.76 | (4.77) | 5.08 | (4.92) | 6.28 | (4.58) | 3.71* |

| Physical Anxiety Symptoms | 8.32 | (6.51) | 7.20 | (6.45) | 9.10 | (6.38) | 4.33* |

| Time 3 | |||||||

| Depressive Symptoms | 9.41 | (7.85) | 9.07 | (8.24) | 9.70 | (7.62) | 0.95 |

| GAD Symptoms | 13.05 | (6.41) | 12.00 | (6.10) | 13.99 | (6.74) | 3.67* |

| Social Anxiety Symptoms | 6.74 | (5.91) | 5.70 | (5.46) | 7.81 | (6.28) | 4.39* |

| Separation Anxiety Symptoms | 5.48 | (4.73) | 5.07 | (5.01) | 5.84 | (4.67) | 1.93 |

| Physical Anxiety Symptoms | 7.69 | (6.35) | 6.67 | (6.29) | 8.32 | (6.45) | 3.12* |

Significant at the .05 level, 2-sided independent samples t-test

Coefficient approached significance at the .10 level, 2-sided independent samples t-test

Unconditional Growth Curve Models

We first examined average patterns of change in anxiety and depression symptoms across one year of early adolescence (measured at three time points: month 0, month 7 and month 12), and included age and gender as predictors of slopes and intercepts. Table 2 summarizes these findings.

Table 2.

Unconditional Univariate Growth Model Mean and Variance Estimates

| Mean | SE | Variance | SE | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| Depressive Symptoms Intercept | 9.85 | 0.19 | 32.59 | 4.21 |

| Depressive Symptoms Slope | 0.10+ | 0.14 | 9.01 | 2.31 |

| Intercept-Slope Covariance | −4.16+ | 2.70 | -- | -- |

|

|

||||

| General Anxiety Disorder Intercept | 14.78 | 0.22 | 28.67 | 4.37 |

| General Anxiety Disorder Slope | −0.80 | 0.14 | 4.07 | 2.19 |

| Intercept-Slope Covariance | −5.48 | 2.76 | -- | -- |

|

|

||||

| Social Anxiety Symptoms Intercept | 8.46 | 0.16 | 20.01 | 2.12 |

| Social Anxiety Symptoms Slope | −0.90 | 0.10 | 4.39 | 1.15 |

| Intercept-Slope Covariance | −2.37++ | 1.28 | -- | -- |

|

|

||||

| Separation Anxiety Symptoms Intercept | 6.58 | 0.13 | 13.88 | 1.39 |

| Separation Anxiety Symptoms Slope | −0.65 | 0.09 | 3.91 | 0.78 |

| Intercept-Slope Covariance | −3.28 | 0.87 | -- | -- |

|

|

||||

| Physical Anxiety Symptoms Intercept | 9.27 | 1.36 | 21.56 | 2.24 |

| Physical Anxiety Symptoms Slope | −0.79 | 0.11 | 4.67 | 1.36 |

| Intercept-Slope Covariance | −2.73 | 1.36 | -- | -- |

Note: All coefficients were significant except:

Coefficient was not significant, p > .10, 2-sided test

Coefficient approached significance, p < .10, 2-sided test.

Depressive Symptoms

On average, although the slope of depressive symptoms was positive, we did not observe statistically significant change in symptoms over the observed time period. However, there was significant variability across adolescents in the rate of change over time, with some adolescents exhibiting increases in depressive symptoms and others exhibiting decreases over time. An adolescent whose growth in depressive symptoms was 1 standard deviation above the mean rate of change would have reported a CDI score by the end of the year that was nearly 12 points higher than their Time 1 score. Finally, the slope and intercept of depression were uncorrelated, such that initial level of depressive symptoms was unrelated to the rate of change over time.

Anxiety Symptoms

All four types of anxiety symptoms decreased, on average, across the year of assessment. Adolescents differed in their rate of decline, however, such that some adolescents declined more than others, and some adolescents experienced increases in symptoms over the course of the year. The intercepts and slopes of each type of anxiety symptoms were negatively correlated, meaning that adolescents with higher initial levels of anxiety symptoms at Time 1 exhibited greater declines over the course of the year. The one exception was social anxiety symptoms, where the intercept and slope were only marginally negatively associated.

Prospective associations between anxiety and depressive symptoms

We next tested a sequence of models examining the prospective association between anxiety and depressive symptoms across the one year study period, estimating an unconditional autoregressive panel model (AR), a parallel process growth model, and an ALT model in turn, separately for the association between depression and each type of anxiety symptom. The autoregressive panel models and the ALT models both provided adequate to good fit to the data, while the fit of the parallel process models were poor. Moreover, the fit of the ALT models were all substantially improved with the addition of the set of covariates, while the fit of the AR models were somewhat less improved. We also tested whether freeing the cross-lags in the ALT and AR models improved model fit, and in all cases model fit was not significantly improved. By multiple fit criteria, both the unconditional and conditional ALT models fit the data better than the AR models and the parallel process models (see Supplementary Online Table 1). Thus, we describe the ALT model throughout the remainder of the results. For parsimony, the final ALT models were specified with covariance of slope and intercept of depression and the effects of the covariates on the slope of depression (all non-significant) fixed to zero. Doing this did not result in worsened model fit by BIC, model residuals or any other indicators of fit, and provided increased degrees of freedom. Results from the final models are shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

Trajectory level and time specific associations between anxiety symptoms and depressive symptoms

| Depressive Symptoms | GAD | Physical Symptoms | Separation Anxiety | Social Anxiety | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Between-individual regression effects | Estimate | SE | Estimate | SE | Estimate | SE | Estimate | SE |

| Depression Intercept predicting Anxiety slope | −0.08+ | 0.05 | 0.15* | 0.05 | 0.13* | 0.04 | 0.11* | 0.04 |

| Anxiety intercept Depression predicting slope | −0.04* | 0.05 | 0.03 | 0.07 | −0.07 | 0.06 | −0.03 | 0.06 |

| Within-individual regression effects | ||||||||

| Depression → Anxiety | 0.10* | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.03 |

| Anxiety → Depression | 0.11* | 0.03 | 0.17* | 0.05 | 0.19* | 0.06 | 0.10* | 0.04 |

|

|

||||||||

| Between-individual residual covariances | ||||||||

| Anxiety slope/intercept | −4.55+ | 2.51 | −2.54 | 1.17 | −2.87* | 0.90 | −2.58* | 1.21 |

| Depression slope/intercept | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Intercepts covariance | 9.59* | 2.54 | 7.18* | 7.56 | 0.47 | 1.88 | 4.30* | 2.00 |

| Slope covariance | −1.32 | 1.03 | −0.69 | 1.27 | −0.52 | 0.81 | −0.16 | 0.96 |

|

|

||||||||

| Within-individual covariance | ||||||||

| Anxiety with depression | 9.21* | 1.06 | 8.52* | 2.20 | 5.21* | 1.62 | 5.94* | 1.59 |

Significant at the .05 level, 2-sided test, controlling for age, gender and single parent household

Coefficient approached significance, p < .10 level, 2-sided test, controlling for age, gender and single parent household.

GAD

Variance in the slope of GAD symptoms was marginally related to initial levels of depressive symptoms, suggesting that adolescents who reported greater depression symptoms at the first interview increased somewhat less on GAD symptoms over time.

Within time, the residual variances of GAD and depressive symptoms were moderately correlated (r = .32 – .50, p < .001), indicating that within-individual differences, or deviations from trajectories at specific time points, were associated. There were also bidirectional associations among these residuals, such that elevations in depressive symptoms over and above an adolescent’s average trajectory at one time point were associated with time-specific increases in GAD symptoms in the next assessment (β = .10, p < .01), and vice-versa (β = .09, p < .01). Figure 1 illustrates this effect.

Figure 1.

Illustration of the three unconditional models tested.

Age (β = .13, p < .01), gender (β = .10, p < .01) and single-parent household (β = .12, p < .01) were all associated with the intercept of depression, such that older adolescents, females, and those from single-parent households reported more depressive symptoms at the initial time point. The covariates were unrelated to the slope or intercept of GAD symptoms.

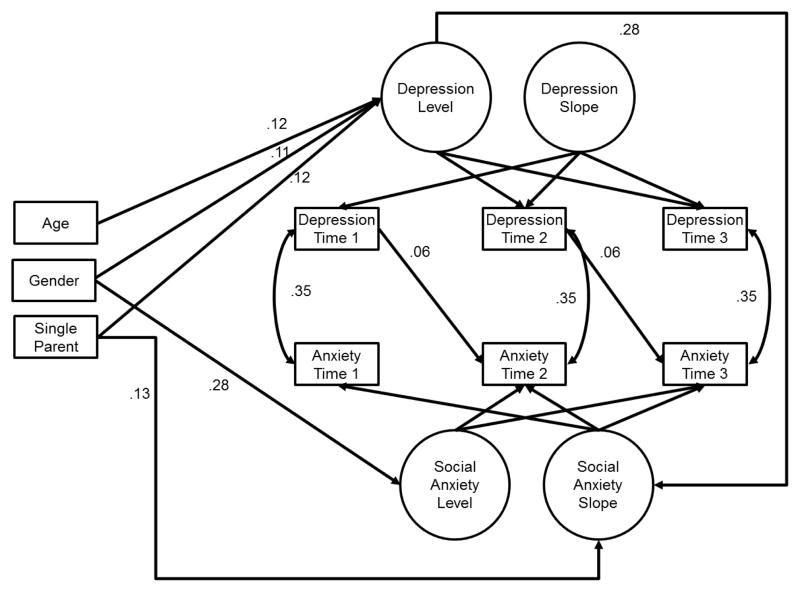

Social anxiety symptoms

Among the latent growth factors, the intercepts of depression and social anxiety symptoms were correlated (r = .20, p < .01), but the correlation between their growth factors was not significant (r = −.04, p = .87). Higher initial levels of depressive symptoms predicted growth in social anxiety symptoms over time (β = 0.28, p = .01). Because social anxiety symptoms declined on average over time, we estimated the predicted slope of social anxiety symptoms at low, mean and high levels of initial depressive symptoms to better understand this effect. An intercept is estimated for each parameter in a growth curve model, providing an estimate of the mean level when all predictors of that parameter are at zero. Thus, for this model, the intercept of the slope of social anxiety is interpreted as the expected rate of change in social anxiety symptoms for an adolescent with no initial depressive symptoms. This intercept was −1.14 (which corresponds to a 2.28 point decline in social anxiety across the course of the year). We estimated the predicted slope of social anxiety at mean levels of depressive symptoms and at 1 standard deviation above the mean. The predicted slope of social anxiety at mean levels of depression was estimated at −0.47 and at 1 SD above the mean of initial depression was −0.03. In other words, higher initial depressive symptoms were related to a trend towards a slower rate of decline in social anxiety symptoms over time.

Within time, the residual variances of social anxiety symptoms and depressive symptoms were moderately correlated (r = .23 – .47, p < .001). There were also prospective associations among the residuals, such that elevations in social anxiety symptoms over and above the average trajectory in one year were associated with time-specific increases in depressive symptoms in the next year (β = .07, p < .01), but not vice-versa.

Females reported higher levels of social anxiety symptoms at the first time point, (β =.28, p < .01), and adolescents from single-parent households exhibited greater increases in social anxiety over time compared to those living with two caregivers (β = .12, p < .05).

Separation anxiety symptoms

Among the latent growth factors of depression and separation anxiety symptoms, the intercepts were uncorrelated (r = .02, p = .80), as were the slopes (r = −.14, p =.55). Higher depressive symptoms at Time 1 were associated with changes in separation anxiety symptoms over time (β = .36, p < .01), but the initial level of anxiety was not associated with changes in depressive symptoms over time. As above, we estimated the predicted separation anxiety slope at low, average and high levels of initial depressive symptoms. At low levels of initial depressive symptoms, separation anxiety symptoms declined the most, and the slope became less steep as depressive symptoms increased. Finally, initial levels of separation anxiety symptoms were associated with the rate of change in separation anxiety, (r = −.48, p < .001), such that adolescents with the highest levels of initial symptoms showed the greatest declines over time.

Within time, the residual variances of separation anxiety and depressive symptoms were moderately correlated (r = .28 – .51, p < .001), indicating that within-individual differences were associated. Moreover, elevations in separation anxiety symptoms over and above the average trajectory were associated with deflections from depressive trajectories (β = .11, p < .01), but not vice versa.

Females reported higher levels of separation anxiety symptoms at baseline, (β = .24, p < .01), as did younger adolescents (β = −.17, p < .001). Moreover, males reported slower decreases (because the average slope was negative) in separation anxiety over time (β = −.18, p < .01).

Physical anxiety symptoms

Among the latent growth factors of depression and physical anxiety symptoms, the intercepts were correlated (r = .37, p < .001), but the slopes were not (r = −.26, p = .64). Higher initial levels of depressive symptoms predicted slower declines in physical anxiety symptoms over time (β = 0.43, p < .05). We estimated predicted growth in physical anxiety symptoms in a manner similar to our approach for social and separation anxiety symptoms. High initial depressive symptoms were related to a slower rate of decline in physical anxiety symptoms over time.

Within time, the residual variances of GAD and depressive symptoms were moderately correlated (r = .34 – .45, p < .001), indicating that deviations from average trajectories at specific time points were associated. There were also prospective associations among the residuals, such that elevations in physical anxiety symptoms over and above the average trajectory in one year were associated with time-specific increases in depressive symptoms in the next year (β = .13, p < .001), but not vice-versa.

Females reported higher levels of separation anxiety symptoms at the first time point, (β = .21, p < .001), but covariates were unassociated with change in physical anxiety over time.

Moderation by gender

Finally, we tested whether any of the associations among the latent growth factors or the residuals differed by gender. For these analyses, we allowed the factor means and variances to differ across gender (to allow for gender differences in trajectories, reported above), and compared models where all correlational and regression parameters of interested were constrained to be equal across gender with a fully freed model. We followed an omnibus model testing strategy, comparing the fit of models where all parameters were allowed to vary across gender with models where all parameters were forced to be equal. This reduced the number of statistical tests and the chance for Type 1 error. When the omnibus test was significant, we examined each specific parameter in turn to determine which parameter differed by gender. Controlling for age and single parent status, we found no evidence of gender moderation that reached the .05 significance level at either the between or within individual level.

Discussion

Adolescence is a period of substantial vulnerability with regards to internalizing psychopathology, particularly major depression. Although anxiety and depression are strongly associated with one another during this developmental period, few studies have characterized the dynamics of anxiety and depression symptom trajectories and their associations with one another across early adolescence. Previous research suggests that adolescents with an anxiety disorder are at elevated risk for future depression (Costello et al., 2003; Merikangas et al., 2003; Pine et al., 1998; Wittchen et al., 2000), and in some studies, major depression is associated with later risk for anxiety disorder onset, particularly GAD (Fergusson & Woodward, 2002; Kim-Cohen et al., 2003; Moffit, Caspi, et al., 2007; Pine et al., 1998). Recent work has also examined latent growth trajectories of anxiety and depressive symptoms over time, using approaches that examine between-individual cross-lagged associations (Cole et. al, 1998; Hale et al., 2009; Leadbetter et al., 2012). We extend these previous studies by using latent growth curve modeling to characterize trajectories of anxiety and depression symptom change across early adolescence, investigate the associations between anxiety and depressive symptom trajectories across time, and evaluate the degree to which within-individual deviations from average trajectories in anxiety and depression are related to one another. Our findings reveal a more complex set of inter-relationships between anxiety and depressive symptoms in early adolescence than has previously been described.

Our first goal was to examine developmental trajectories of anxiety and depressive symptoms. We found that most adolescents experience declines in anxiety symptoms across early adolescence. This pattern was observed for symptoms of GAD, social anxiety, separation anxiety, and physical anxiety. These findings are consistent with several recent prospective studies that have also observed declines in anxiety symptoms over the early adolescent period (Burstein et al., 2010; Crocetti et al., 2009; Hale et al., 2008; Van Oort et al., 2009). Declines in symptoms of separation anxiety over time were particularly pronounced for adolescents with high initial levels of separation anxiety symptoms. In contrast, we found no change in the mean level of depressive symptoms over the one-year study period. Although developmental increases in symptoms of depression during early to mid-adolescence have been frequently documented (Ge et al., 2001; Twenge & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2002; Van Oort et al., 2009), a similar pattern of non-significant changes in adolescent-reported depressive symptoms was reported in a school-based sample of early adolescents followed for several years (Garber, Keiley, & Martin, 2002), and other studies of early adolescents have also found stability in adolescent reports of depressive symptoms (Garrison, Jackson, Marsteller, McKeown, & Addy, 1990). One explanation for the stability in depressive symptoms observed here is that our early adolescent sample has yet to enter the risk window when depressive symptoms begin to increase more drastically in mid-adolescence (Ge et al., 2001; Hankin et al., 1998).

Our second objective was to investigate associations between anxiety and depressive symptoms, both between individuals and within individuals, over time. In between-individual analysis, adolescents with higher initial levels of depressive symptoms exhibited slower declines in physical, separation and social anxiety symptoms over time, above and beyond the effects of age and gender. This means that experiencing depressive symptoms appears to arrest declines in multiple forms of anxiety symptoms over time. Slower declines in physical anxiety symptoms among adolescents with high levels of depressive symptoms may reflect overlap in symptoms of anxiety and depression (e.g., psychomotor agitation) or be the result of cognitive processes, such as anxiety sensitivity. High levels of anxiety sensitivity have been observed in adolescents with depressive symptoms (Weems, Hammond-Laurence, Silverman, & Ferguson, 1997), and consistent evidence suggests that anxiety sensitivity is associated with vulnerability to anxiety pathology in youths, particularly to panic attacks and other physical manifestations of anxiety (Lau, Calamari, & Waraczynski, 1996; Pollock et al., 2002; Weems, Hammond-Laurence, Silverman, & Ginsburg, 1998). Depressive symptoms may influence social anxiety trajectories in adolescence because of the strong influence of peer relationships on social anxiety during this developmental period. Affiliation with a peer group, positive relationships with a best friend, and engagement in dating relationships all protect against social anxiety in early adolescence (LaGreca & Harrison, 2005), and adolescents with high levels of depressive symptoms engage in a variety of negative interpersonal behaviors—such as reassurance seeking—that generate stressors in their interpersonal relationships and result in diminishing friendship quality over time (Joiner, Alfano, & Metalsky, 1992; Prinstein, Borelli, Cheah, Simon, & Aikins, 2005). Similar social mechanisms may also explain the relationship between symptoms of depression and slower decline in separation anxiety symptoms during early adolescence, although this possibility remains to be examined empirically. The identification of cognitive (e.g., rumination; McLaughlin & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2011), affective (e.g., chronic negative affect; Chorpita, 2002), environmental (e.g., trauma exposure, stressful life events; Rudolph et al., 2005), and neurobiological factors (e.g., pubertal timing; Graber, Seeley, Brooks-Gunn, & Lewinsohn, 2004) that underlie transitions between anxiety and depression symptoms during early adolescence is an important direction for future research.

A more nuanced pattern emerged when we examined the associations between anxiety and depression symptom trajectories within individuals over time, an approach that has not previously been used to investigate the development of internalizing psychopathology during early adolescence. Our findings argue for the importance of such an approach. The most consistent associations between symptoms of anxiety and depression in our sample were observed in within-individual analysis—in other words, when adolescents experienced a higher level of a specific type of symptom at a particular time than would be expected given their overall symptom trajectory, they were also likely to experience a later deflection from their average trajectory in other symptoms. Adolescents who experienced an elevation in symptoms of social anxiety and physical anxiety relative to their average trajectory experienced subsequent deflections from their average trajectory of depressive symptoms, but not vice versa. The association between elevations in social anxiety and future elevations in depressive symptoms is consistent with previous between-individual prospective studies showing that adolescent social anxiety disorder predicts the future onset of major depression and poor prognosis of depression recovery (Beesdo et al., 2007; Stein et al., 2001). Panic disorder is also associated with the later onset of major depression (Gorman & Coplan, 1996; Roy-Byrne et al., 2000). However, we are unaware of previous studies linking within-individual elevations in social and physical anxiety symptoms to later elevations in depressive symptoms. In contrast, deflections from average trajectory of depression predict later deflections in separation anxiety symptoms, but not vice versa, suggesting greater avoidance of social situations outside the family among adolescents with higher levels of depressive symptoms at a particular point in time than is typical for them. Youths with high levels of depressive symptoms are more likely to be the targets of peer victimization and bullying than those with low levels of depression (Hodges, Malone, & Perry, 1997; Vernberg, 1990), which might be one mechanism explaining greater reluctance to engage in social activities outside the family among adolescents with elevated depressive symptoms. Future research is needed to identify mechanisms linking depressive symptoms to future elevations in separation anxiety. Finally, we observed bidirectional associations between within-individual elevations in symptoms of GAD and depression. Previous studies in both adolescents and adults indicate that depression is associated more strongly with future GAD than with other anxiety disorders (Moffit, Harrington, et al., 2007; Pine et al., 1998), and our results are consistent with this pattern. Together, these findings highlight the importance of identifying social, environmental, and intrapersonal factors that result in changes in symptom levels for an adolescent relative to his/her typical symptom trajectory and developing strategies to determine when such deflections have occurred in order to deliver interventions at those points when adolescents are most vulnerable to accelerating increases in symptomatology. They further suggest that even small increases in depression and anxiety symptoms during early adolescence might be important clinically, as they can be early signs of a trajectory of increasing symptom over time.

Our third goal was to examine gender differences in both developmental trajectories of anxiety and depressive symptoms and associations of symptoms with one another across time. In this sample, gender differences in overall levels of symptoms were more pronounced than differences in the associations of anxiety and depression across time. Generally, females reported higher levels of both depression and anxiety of all types, but there were no differences in the rates of change in depression or anxiety over time. Thus, across at least this one-year period in early adolescence, males and females had parallel trajectories of internalizing symptoms, with females reporting higher levels of symptoms. Several previous prospective epidemiological studies of youth psychopathology have reported greater heterotypic continuity between anxiety disorders and major depression (i.e., stronger prospective associations between anxiety disorders and subsequent major depression) in females as compared to males (Costello et al., 2003; McGee et al., 1992; Merikangas et al., 2003). At the level of symptom trajectories, we found no gender differences in the prospective associations between anxiety and depression, in contrast to what has been reported in previous studies. This might be due to the fact that our follow-up period was shorter than in previous longitudinal studies or because our sample was younger, on average, than in some previous studies that have observed stronger associations between depression and anxiety for females than males (e.g., Merikangas et al., 2003). Perhaps most notably, these previous studies focused on diagnostic outcomes, whereas our analyses focus on associations of symptom trajectories.

These findings should be interpreted in light of several study limitations. First, our analysis focused on self-reported symptoms of depression and anxiety rather than diagnoses of anxiety disorders or major depression. Although the validity of the self-report measures used in this study is well-established (Timbremont, Braet, & Dreessen, 2004; Wood, Piacentini, Bergman, McCracken, & Barrios, 2002), future research is needed to evaluate the relationships between onset, persistence, and recurrence of anxiety disorders and major depression during early adolescence. Second, adolescents with high levels of depressive symptoms at Time 1 were more likely to be lost to follow-up by the Time 3 assessment than adolescents with lower levels of symptoms. This likely contributed to our finding that the average level of depressive symptoms did not change over time in this sample. It is possible that we would have observed greater increases in depressive symptoms over time if we had been able to assess the entire Time 1 sample at both of the follow-up assessments. Moreover, our prospective models cover a relatively small age span, and only include two follow up time points. This precluded testing developmental hypotheses about sensitive periods for the association between depressive and specific forms of anxiety symptoms, including whether the association is stronger earlier or later in adolescence. The study design also limits the scope of what we may conclude about the associations among depression and anxiety symptoms to the period of early adolescence. Finally, we were unable to collect information about pubertal stage in this sample. Early developmental timing of puberty has been shown to predict depression in females (Graber et al., 2004). The degree to which developmental timing of puberty influences both the trajectories of anxiety and depressive symptoms across adolescence, and their association with one another, is an important topic for future research.

Although early adolescence is a developmental period of increasing risk for major depression, most adolescents experience declines in anxiety symptomatology during this period. Study findings suggest that these declines over time are less marked for adolescents with high levels of depressive symptoms. Associations between symptoms of depression and anxiety over time were particularly strong when examined within individuals over time, such that adolescents with higher levels of anxiety or depressive symptoms at a particular time than would be expected given their overall symptom trajectory experienced subsequent elevations in other types of internalizing symptoms. These findings suggest that symptom elevations at one point in time can lead to a cascade of increases in other types of internalizing symptoms over time and highlight the importance of identifying these early shifts in symptom trajectories in order to prevent symptom acceleration and, ultimately, the onset of anxiety and mood disorders.

Supplementary Material

Figure 2.

Illustration of the conditional ALT model of depression and social anxiety 1 year. Non-significant paths and residual covariances among latent variables are not shown for the sake of simplicity.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by a grant from the National Institutes of Health (K01-MH092526 to McLaughlin).

References

- Angold A, Costello EJ, Erkanli A. Comorbidity. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1999;40:57–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett P. Structural equation modeling: Adjudsting model fit. Personality and Individual Differences. 2007;42:815–824. [Google Scholar]

- Beesdo K, Bittner A, Pine DS, Stein MB, Hofler M, Lieb R, Wittchen HU. Incidence of social anxiety disorder and the consistent risk for secondary depression in the first three decades of life. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2007;64(8):903–912. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.8.903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollen KA, Curran PJ. Autoregressive latent trajectory (ALT) models: A synthesis of two traditions. Sociological Methods and Research. 2004;32:336–383. [Google Scholar]

- Brent DA, Perper J, Moritz G, Allman C, Friend A, Roth C, Baugher M. Psychiatric risk factors for adolescent suicide: A case-control study. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1993;32:521–529. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199305000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burstein M, Ginsburg GS, Petras H, Ialongo N. Parent psychopathology and youth internalizing symptoms in an urban community: A latent growth model analysis. Child Psychiatry and Human Development. 2010;41:61–87. doi: 10.1007/s10578-009-0152-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cambell LA, Brown TA, Grisham JR. The relevance of age of onset to the psychopathology of GAD. Behavior Therapy. 2003;34:31–48. [Google Scholar]

- Chen F, Curran P, Bollen KA, Kirby J, Paxton P. An empirical evaluation of the use of fixed cutoff points in RMSEA test statistic in structural equation models. Sociological Methods and Research. 2008;36:462–494. doi: 10.1177/0049124108314720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chorpita BF. The tripartite model and dimensions of anxiety and depression: An examination of structure in a large school sample. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2002;30:177–190. doi: 10.1023/a:1014709417132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chorpita BF, Tracey SF, Brown TA, Collica TJ, Barlow DH. Assessment of worry in children and adolescents: An adaptation of the Penn State Worry Questionnaire. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1997;35:569–581. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(96)00116-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole DA, Peeke LG, Martin JM, Truglio R, Seroczynski AD. A longitudinal look at the relation between depression and anxiety in children and adolescents. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66:451–460. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.3.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Copeland WE, Shanahan L, Costello EJ, Angold A. Childhood and adolescent psychiatric disorders as predictors of young adult disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2009;66:764–772. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello EJ, Erkanli A, Angold A. Is there an epidemic of child or adolescent depression? Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2006;47(12):1263–1271. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01682.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello EJ, Mustillo S, Erkanli A, Keeler G, Angold A. Prevalence and development of psychiatric disorders in childhood and adolescence. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003;60:837–844. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.8.837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crocetti E, Klimstra T, Keijsers L, Hale WW, Meeus W. Anxiety trajectories and identity development in adolescence: A five-wave longitudinal study. Journal of Youth and Adolescence. 2009;38:839–849. doi: 10.1007/s10964-008-9302-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran PJ, Hussong AM. The use of latent trajectory models in psychopathology research. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2003;112:526–544. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.112.4.526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Horwood J, Ritter EM, Beautrais AL. Subthreshold depressive symptoms in adolescence and mental health outcomes in adulthood. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2005;62:66–72. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.1.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fergusson DM, Woodward LJ. Mental health, educational, and social role outcomes of adolescents with depression. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2002;59:225–231. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.3.225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleeson W. Studying personality processes: Explaining change in between-persons longitudinal and within-person multilevel models. In: Robins RW, Fraley RC, Krueger RF, editors. Handbook of research methods in personality psychology. New York, NY, US: Guilford Press; 2007. pp. 523–542. (2007) [Google Scholar]

- Fombonne E, Wostear G, Cooper V, Harrington R, Rutter M. The Maudsley long-term follow-up of child and adolescent depression: 1. Psychiatric outcomes in adulthood. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2001a;179:210–217. doi: 10.1192/bjp.179.3.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fombonne E, Wostear G, Cooper V, Harrington R, Rutter M. The Maudsley long-term follow-up of child and adolescent depression. 2. Suicidality and social dysfunction in adulthood. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2001b;179:218–223. doi: 10.1192/bjp.179.3.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garber J, Keiley MK, Martin NC. Developmental trajectories of adolescents’ depressive symptoms: Predictors of change. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70:79–95. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.1.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrison CZ, Jackson KL, Marsteller F, McKeown RE, Addy CL. A longitudinal study of depressive symptomatology in young adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1990;29:581–585. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199007000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge X, Conger RD, Elder GH. Pubertal transition, stressful life events, and the emergence of gender differences in adolescent depressive symptoms. Developmental Psychology. 2001;37:404–417. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.37.3.404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgiades K, Lewinsohn PM, Monroe SM, Seeley JR. Major Depressive Disorder in Adolescence: The Role of Subthreshold Symptoms. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2006;45(8):936–944. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000223313.25536.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorman JM, Coplan JD. Comorbidity of depression and panic disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 1996;57(Suppl 10):34–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gotlib IH, Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR. Consequences of depression during adolescence: Marital status and marital functioning in early adulthood. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1998;107(4):686–690. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.107.4.686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graber JA, Seeley JR, Brooks-Gunn J, Lewinsohn PM. Is Pubertal Timing Associated With Psychopathology in Young Adulthood? Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2004;43:718–726. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000120022.14101.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hale WW, Raaijmakers Q, Muris P, van Hoof A, Meeus W. Developmental trajectories of adolescent anxiety disorder symptoms: A 5-year prospective community study. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2008;47:556–564. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181676583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hale WW, Raaijmakers QAW, Muris P, van Hoof A, Meeus WHJ. One factor or two parallel processes? Comorbidity and development of adolescent anxiety and depressive disorder symptoms. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2009;50:1218–1226. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02115.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hankin BL, Abramson LY, Moffitt TE, Silva PA, McGee R, Angell KE. Development of depression from preadolescence to young adulthood: Emerging gender differences in a 10-year longitudinal study. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1998;107:128–140. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.107.1.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hodges EVE, Malone MJ, Perry DG. Individual risk and social risk as interacting determinants of victimization in the peer group. Developmental Psychology. 1997;33:1032–1039. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.33.6.1032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indices in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Joiner TE, Jr, Alfano MS, Metalsky GI. When depression breeds contempt: Reassurance seeking, self-esteem, and rejection of depressed college students by their roommates. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1992;101:165–173. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.101.1.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim-Cohen J, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Harrington H, Milne BJ, Poulton R. Prior juvenile diagnoses in adults with mental disorder: developmental follow-back of a prospective-longitudinal cohort. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003;60(7):709–717. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.7.709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King KM, Molina BS, Chassin L. Prospective relations between growth in drinking and familial stressors across adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2009;118:610–622. doi: 10.1037/a0016315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M. Children’s Depression Inventory manual. North Tonawanda, NY: Multi-Health Systems; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- LaGreca AM, Harrison HM. Adolescent peer relations, friendships, and romantic relationships: Do they predict social anxiety and depression? Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2005;34:49–61. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3401_5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Last CG, Perrin S, Hersen M, Kazdin AE. DSM-III-R anxiety disorders in children: Sociodemographic and clinical characteristics. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1992;31:1070–1076. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199211000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lau JJ, Calamari JE, Waraczynski M. Panic attack symptomatology and anxiety sensitivity in adolescents. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 1996;10:355–364. [Google Scholar]

- Leadbeater BJ, Thompson K, Gruppuso V. Co-occurring trajectories of symptoms of anxiety, depression, and oppositional defiance from adolescence to young adulthood. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2012;41:719–730. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2012.694608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little RJA, Rubin DB. Statistical analysis with missing data. New York: John Wiley and Sons; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- March JS, Parker JDA, Sullivan K, Stallings P, Conners CK. The Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC): Factor structure, reliability, and validity. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1997;36:554–565. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199704000-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh HW, Hau KT, Wen Z. In search of golden rules: Comment on hypothesis-testing approaches to setting cutoff values for fit indexes and dangers in overgeneralizing Hu and Bentler’s (1999) findings. Structural Equation Modeling. 2004;11:320–341. [Google Scholar]

- McGee R, Feehan M, Williams S, Anderson J. DSM-III disorders from age 11 to age 15 years. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 1992;31(1):50–59. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199201000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin KA, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Rumination as a transdiagnostic factor in depression and anxiety. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2011;49:186–193. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2010.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas KR, Zhang H, Avenevoli S, Acharyya S, Meuenschwander M, Angst J. Longitudinal trajectories of depression and anxiety in a prospective community study: The Zurich Cohort Study. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2003;60:993–1000. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.9.993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer TJ, Miller ML, Metzger RL, Borkovec TD. Development and validation of the Penn State Worry Questionnaire. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1990;28:487–495. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(90)90135-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millsap RE. Structural equation modeling made difficult. Personality and Individual Differences. 2007;42:875–881. [Google Scholar]

- Moffit TE, Caspi A, Harrington H, Milne BJ, Melchior M, Goldberg DA, Poulton R. Generalized anxiety disorder and depression: childhood risk factors in a birth cohort followed to age 32. Psychological Medicine. 2007;37:441–452. doi: 10.1017/S0033291706009640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffit TE, Harrington H, Caspi A, Kim-Cohen J, Goldberg DA, Gregory AM, Poulton R. Depression and generalized anxiety disorder: Cumulative and sequential comorbidity in a birth cohort followed prospectively to age 32 years. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2007;64:651–660. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.6.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muris P, Merckelbach H, Ollendick T, King N, Bogie N. Three traditional and three new childhood anxiety questionnaires: their reliability and validity in a normal adolescent sample. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2002;40:753–772. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(01)00056-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus 5.1. Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén; 2008a. [Google Scholar]

- Nolen-Hoeksema S, Girgus JS. The emergence of gender differences in depression during adolescence. Psychological Bulletin. 1994;115(3):424–443. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.115.3.424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olino TM, Klein DN, Lewinsohn PM, Rohde P, Seeley JR. Latent trajectories of depressive and anxiety disorders from adolescence to adulthood: descriptions of classes and associations with risk factors. Comprehensive Psychiatry. 2010;51:224–235. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pine DS, Cohen E, Cohen P, Brook JS. Adolescent depressive symptoms as predictors of adult depression: Moodiness or mood disorder? American Journal of Psychiatry. 1999;156(1):133–135. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.1.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pine DS, Cohen P, Gurley D, Brook J, Ma Y. The risk for early adulthood anxiety and depressive disorders in adolescents with anxiety and depressive disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1998;55:56–64. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.1.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollock RA, Carter AS, Avenevoli S, Dierker LC, Chazan-Cohen R, Merikangas KR. Anxiety sensitivity in adolescents at risk for psychopathology. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2002;31:343–353. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3103_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prinstein MJ, Borelli JL, Cheah CSL, Simon VA, Aikins JW. Adolescent girls’ interpersonal vulnerability to depressive symptoms: a longitudinal examination of reassurance-seeking and peer relationships. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2005;114:676–688. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.114.4.676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds WM. Assessment of depression in children and adolescents by self-report measures. In: Reynolds WM, Johnston HF, editors. Handbook of depression in children and adolescents. New York: Plenum Press; 1994. pp. 209–234. [Google Scholar]

- Roy-Byrne PP, Stang PE, Wittchen HU, Ustun B, Walters EE, Kessler RC. Lifetime panic-depression comorbidity in the National Comorbidity Survey. British Journal of Psychiatry. 2000;176:229–235. doi: 10.1192/bjp.176.3.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satorra A. Scaled and adjusted restricted tests in multi-sample analysis of moment structures. In: Heijmans RDH, Pollock DSG, Satorra A, editors. Innovations in multivariate statistical analysis. A Festschrift for Heinz Neudecker. London: Kluwer Academic; 2000. pp. 233–247. [Google Scholar]

- Schafer JL, Graham JW. Missing data: Our view of the state of the art. Psychological Methods. 2002;7:147–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein MB, Fuetsch M, Muller N, Hofler M, Lieb R, Wittchen HU. Social anxiety disorder and the risk of depression: a prospective community study of adolescents and young adults. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2001;58:251–256. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.3.251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timbremont B, Braet C, Dreessen L. Assessing depression in youth: Relation between the Children’s Depression Inventory and a structured interview. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2004;33:149–157. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3301_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Twenge JM, Nolen-Hoeksema S. Age, gender, race, socioeconomic status, and birth cohort differences on the children’s depression inventory: a meta-analysis. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2002;111(4):578–588. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.111.4.578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Oort FVA, Greaves-Lord K, Verhulst FC, Ormel J, Huizink AC. The developmental course of anxiety symptoms during adolescence: the TRAILS study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2009;50:1209–1217. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02092.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vernberg EM. Psychological adjustment and experiences with peers during early adolescence: Reciprocal, incidental, or unidirectional relationships? Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1990;18:187–198. doi: 10.1007/BF00910730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voelkle MC. Reconsidering the use of Autoregressive Latent Trajectory (ALT) models. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2008;43:564–591. doi: 10.1080/00273170802490665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weems CF, Hammond-Laurence K, Silverman WK, Ferguson C. The relation between anxiety sensitivity and depression in children and adolescents referred for anxiety. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1997;35(10):961–966. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(97)00049-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weems CF, Hammond-Laurence K, Silverman WK, Ginsburg GS. Testing the utility of the anxiety sensitivity construct in children and adolescents referred for anxiety disorders. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology. 1998;27:69–77. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp2701_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittchen HU, Kessler RC, Pfister H, Lieb R. Why do people with anxiety disorders become depressed? A prospective-longitudinal community study. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2000;102:14–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood JJ, Piacentini JC, Bergman RL, McCracken J, Barrios V. Concurrent validity of the anxiety disorders section of the Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV: Child and parent versions. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2002;31:335–342. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3103_05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.