Abstract

Objective

To explore risk factors for postpartum weight retention at one year after delivery in predominantly low income women.

Methods

Data were collected from 774 women with complete height and weight information from participants in the NICHD Community Child Health Network, a national five-site, prospective cohort study. Participants were enrolled primarily in the hospitals immediately after delivery. Maternal interviews conducted at 1, 6, and 12 months postpartum identified risk factors for weight retention and included direct measurement of height and weight at 6 and 12 months. Logistic regression assessed the independent contribution of postpartum weight retention on obesity.

Results

Women had a mean prepregnancy weight of 161.5 lbs (BMI 27.7kg/m2). Women gained a mean of 32 lbs while pregnant and had a 1 year mean postpartum weight of 172.6 lbs (BMI 29.4kg/m2). Approximately 75% of women were heavier 1 year postpartum than they were prepregnancy, including 47.4% retaining over 10 lbs and 24.2% over 20 lbs. Women retaining at least 20 lbs were more often African American, younger, poor, less educated, or on public insurance. Race and socioeconomic disparities were associated with high pre-pregnancy BMI and excessive weight gain during pregnancy, associations which were attenuated by breastfeeding at 6 months and moderate exercise. Of the 39.8 with normal prepregnancy BMI, one third became overweight or obese 1 year postpartum.

Conclusion

Postpartum weight retention is a significant contributor to the risk for obesity 1 year postpartum, including for women of normal weight prepregnancy. Postpartum, potentially modifiable behaviors may lower the risk.

Introduction

The epidemic of obesity is perhaps the most pressing health concern today. According to the latest data from the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) from 2012, 35.1% of women over 20 years of age are obese (BMI ≥30 kg/m2) and another 33.9% are overweight (BMI ≥25 kg/m2).(1) Obesity is associated with reduced fertility, increased maternal and fetal risks during childbearing, and long term health risks for women.(2,3,4,5,6,7) Excess weight increases maternal risk of coronary artery disease, ischemic stroke, type 2 diabetes mellitus, osteoarthritis, gallbladder disease, hypertension, and some cancers including breast and colon.(8)

As a result, current recommendations include counseling women to achieve a normal weight status prior to becoming pregnant and to adhere to the Institute of Medicine (IOM) guidelines for gestational weight gain. However, many women never lose the weight gained during a gestation, placing them at heightened risk for subsequent overweight and obesity in ensuing pregnancies and lifelong. Although addressing the obesity epidemic is critical for improving women’s health, prior studies on risk factors for postpartum weight retention have shown conflicting results such as on the issue of parity (9,10), and have not attempted to quantify the co-occurrence of potentially modifiable behaviors that are associated with postpartum weight retention. A clear understanding of the risk factors for postpartum weight retention is needed to start to combat the problem. The purpose of this study was to investigate the contribution of postpregnancy weight retention to obesity in young women at one year postpartum and to better understand modifiable factors that can lead to tailored interventions during and after pregnancy. In a national sample of predominantly low-income women drawn from the NICHD Community Child Health Network (CCHN), we evaluated risk factors for postpartum weight retention.

Materials and Methods

Data were drawn from a national prospective cohort study conducted by the NICHD Community Child Health Network (CCHN). The CCHN is a group of community organizations and universities partnering to gain new insights into the contributors to the disparities in maternal health and child development. A five year observational study was completed according to principles of community-based participatory research in order to better understand multiple levels of maternal stress, resiliency, and allostatic load in the interconception period. The CCHN study enrollment sites include three urban (Baltimore, Los Angeles, and Washington, DC), one mixed urban/suburban (Lake County, IL) and one rural location (Eastern North Carolina).

Most participants were enrolled in the hospitals after delivery. Eligible participants were women aged 18 to 40 and with a live birth of greater than or equal to 20 weeks of gestation. Women were excluded if they were unable to give informed consent. As one of the study objectives was to assess outcomes after future pregnancies, women who could not become pregnant or were unlikely to become pregnant were excluded. These exclusions were: surgical sterilization following the current delivery and having four or more children. The final sample comprised mostly low income women who were African American, White, or Hispanic (both English and Spanish speakers). Inclusion criteria for this secondary analysis additionally specified the availability of prepregnancy height and weight data, height at 6 months, 1 year or both, and weight data at one year postpartum along with no subsequent pregnancy within one year postpartum.

Medical records were reviewed for the prepregnancy BMI and delivery information. Patients completed a brief baseline interview at enrollment, followed by three extensive in-home interviews at 1 month, 6 months, and 12 months postpartum. Interviews were conducted in English and Spanish in accordance with respondent preference. Maternal height was measured by the interviewer at 6 months, 12 months or both while maternal weight was obtained by the interviewer at 6 months and 12 months postpartum.

Insurance status was coded as private or public insurance at the time of delivery as listed in the medical record. Respondents self identified as African American, White, Hispanic, or other. The preferred language to conduct the interviews was used to delineate English-speaking and Spanish-speaking. Women provided their relationship status and whether the pregnancy had been planned on the initial screening interview while in the hospital. Education was defined by the highest level of schooling completed by the 1 month postpartum interview. Income level was characterized as poor at <200% Federal Poverty Level or non-poor at >200% Federal Poverty Level based on self report of household income and number of family members at the 1 month postpartum interview.

Weight was evaluated using the UC-321 Precision Person Health digital scale that allowed a maximal weight of 350 lbs on both the 6 month and 12 month visit. Interviewers were instructed to place the scale on a hard surface, have the women take off her shoes, then have the participant stand on the scale and remain still until the measurement was displayed on the scale monitor. The weight was then recorded. For practical purposes, as the interviewers had to carry the scale to each patients’ home, a scale that could measure weights greater than 350 lbs was not used. Height was measured in centimeters by study personnel on either the 6 month or 12 month visit or both. Interviewers determined the height by having women remove their footwear and stand on a flat hard surface near a smooth vertical wall. The participant stood with heels against the wall with their feet and knees together. A wooden triangle was placed with the flat side against the wall and the perpendicular side along the head. A Post-It note was then placed at the right angle of the triangle. Height was measured with a rigid measuring tape from the bottom edge of the Post-It note straight to the floor and recorded. BMI was categorized according to the Institute of Medicine criteria of underweight <18.5 kg/m2, normal 18.5 to 24.9 kg/m2, overweight 25.0 to 29.9 kg/m2, and obese ≥30.0 kg/m2.

After the Institute of Medicine recommendations, women were considered to have gained an excessive amount of gestational weight if their prepregnancy BMI was normal and they gained more than 35 lbs, they were overweight prior to pregnancy and they gained more than 25 lbs, or they were obese prior to pregnancy and they gained more than 20 lbs.(11)

Women reported whether they were exercising at the 6-month interview. The amount of exercise was categorized based on the International Physical Activity Questionnaire with modifications to account for the postpartum state.(12) Moderate exercise was defined as: a) 3 or more days of vigorous activity of at least 20 minutes per day; b) 5 or more days of moderate activity and/or walking of at least 30 minutes per day; or c) 5 or more days of any combination of walking, moderate or vigorous activities achieving a minimum total physical activity of at least 600 MET-minutes/week. Vigorous exercise was defined as) vigorous-intensity activity on at least 3 days achieving a minimum total physical activity of at least 1500 MET-minutes/week or b) 7 or more days of any combination of walking, moderate-intensity or vigorous-intensity activities achieving a minimum total physical activity of at least 3000 MET-minutes/week (12) Moderate activity was defined as “activities that take moderate physical effort and make you breathe somewhat harder than normal.” Vigorous activity was described as “activities that take hard physical effort and make you breathe much harder than normal.” Any amount of exercise that did not meet the criteria for moderate or high was considered low.

At the 1-month and 6-month interviews, mothers were queried whether they ever breastfed the child, and if so, for how long. For those mothers who were still breastfeeding at the 6 month interview, duration was approximated as the age of the child at the date of the interview. Breastfeeding included both partial and exclusive. Women were asked about their smoking status and their average hours of nightly sleep at 6 months. Women also reported about their use of birth control and if they were working outside the home at the 1 year interview.

Bivariate analysis examined the relation between postpartum weight retention (<19 lbs and ≥20 lbs) and key variables. Differences in the distribution for each covariate by exposure status were assessed using Student’s t-tests, Wilcoxon-rank sum, and chi-square analysis. Multivariable analysis was executed using nested linear regression. This method quantifies the additional contribution of the added variable group to the amount of variation in the dependent variable (postpartum weight retention ≥20 lbs) explained by the model. C-statistics were calculated. In successive models, we regressed ≥20 lbs of weight retention at 1 year postpartum on 1) nonmodifiable maternal factors such as age and race, 2) other socioeconomic demographics such as type of insurance, marital status, poverty level, weight gain during pregnancy and prepregnancy BMI and 3) potentially modifiable postpartum behaviors, such as, breastfeeding, working outside the home, and average of hours of nightly sleep. This cut off was selected for the regression model because ≥20 lbs of weight retention constituted a more than 10% increase in weight for majority of women in the study, which is clinically relevant and similar to the definition of weight retention used in other recent studies.(13,14) The variables included in each model were based on the results of bivariate analysis. When variables were highly correlated (i.e., insurance, poverty, income), only the variable with the largest variance explained was included in the multivariable model to avoid multicollinearity. For model comparison, we used the bootstrap method to calculate the 95% confidence interval of the C-statistic for each model. Throughout the data analysis, P values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant. Analyses were conducted using SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). Institutional Review Board approval was obtained at each site.

Results

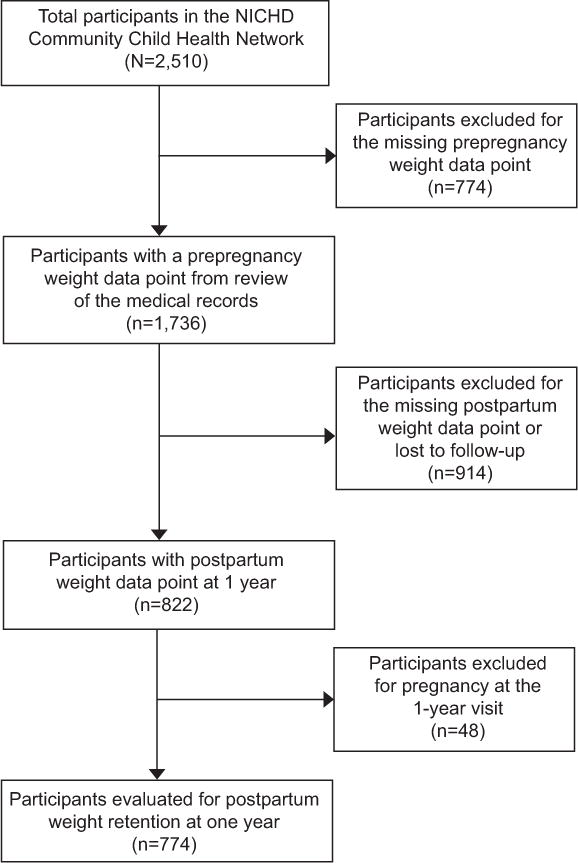

Of the 2,510 mothers enrolled in CCHN, 774 had prepregnancy height and weight data, postpartum height and weight data, and did not become pregnant again within 1 year postpartum. (Figure 1) There were no statistically significant differences in the demographic characteristics of age, race, parity, or income level between the 774 women who had complete BMI data and no subsequent pregnancy within one year and the other 1,736 study participants. Data from the subset of 774 women was then used for the analysis.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the study population. NICHD, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

Almost half the sample was African American, the remainder split between Whites and Hispanics. Hispanics were further divided into mostly Spanish (64%) versus English speakers (36%). Mean age was 26±5.8 (range 18–42) years. Most women delivered a term infant with a normal birth weight (>2500 grams or 5.5 lbs). About one third had not planned the pregnancy and about one third were enrolled after delivering their first child. (Table 1)

Table 1.

Study Participants (n=744)

| Characteristic | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Maternal age at delivery | 26.2±5.8 years |

| Race: African American White Hispanic Other |

46% 24.7% 27.8% 1.5% |

| Gestational age at delivery | 38.3±2.1 weeks |

| Delivery at <37 weeks of gestation | 6.7% |

| Neonatal birth weight | 7.1±1.4 lbs |

| Parity: Nulliparous Multiparous |

33.4% 66.6% |

| Diabetes during pregnancy | 6.6% |

| Level of education: <12 years >12 years |

69.2% 30.8% |

| Planned pregnancy: Yes No |

35.9% 64.1% |

| SES: ≥200% FPLˆ <200% FPL |

60.6% 39.4% |

| Smoking during

pregnancy: Yes No |

5.7% 94.3% |

Federal Poverty Level

The meanprepregnancy weight was overweight: 161.5 (range 82–345) lbs with a BMI of 27.7 (range 15.8–54.6) kg/m2. (Table 2) More than half the sample had an unhealthy weight prior to pregnancy with 4.0% of women underweight, 39.8% normal, 26.4 % overweight, and 29.8% obese. At 1 year postpartum, 2.7% were underweight, 29.8% were normal, 26.1% were overweight, and 41.3% were obese. The number of obese women significantly increased from 237 (29.8%) prepregnancy to 320 (41.3%) at 1 year postpartum (p<.001).

Table 2.

Sample characteristics by weight retention and bivariate analysis at 1 year postpartum

| Total (N=774) | Weight retention <20

lbs (n=587) |

Weight retention ≥20

lbs (n=187) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| Characteristics | p value | |||

| Age (yr) | 26.2±5.8 | 26.7±5.9 | 24.4±5.0 | <.001 |

| GA age (wk) | 38.3±2.1 | 38.3±1.9 | 38.4±2.4 | 0.67 |

| Prepregnancy weight (lb) | 161.5±46.2 | 158.2±45.8 | 171.8±46.1 | <.001 |

| Prepregnancy BMI (kg/m2) | 27.7±7.2 | 27.3±7.1 | 29.0±7.4 | 0.0052 |

| Baby weight (g) | 3235.1±619.6 | 3213.2±625.6 | 3304.0±597.2 | 0.126 |

| Delivery weight (lb) | 191.7±45.7 | 184.6±43.0 | 214.1±46.7 | <.001 |

| Postpartum weight at 1 year (lb) | 172.6±50.1 | 160.9±44.5 | 209.2±49.1 | <.001 |

| Postpartum BMI at 1 year (kg/m2) | 29.4±7.9 | 27.7±7.1 | 35.0±7.6 | <.001 |

| Weight gain during pregnancy (lb) | 32.0±15.9 | 28.5±12.6 | 42.7±19.9 | <.001 |

| Weight retention at 6 month (lb) | 12.0±20.3 | 5.2±15.0 | 33.2±20.3 | <.001 |

| Weight retention at 1 year (lb) | 11.1±21.0 | 2.7±14.3 | 37.4±16.2 | <.001 |

| Breast feeding duration (weeks) | 13.7±13.8 | 15.2±14.3 | 8.9±11.0 | <.001 |

|

| ||||

| Prepregnancy BMI | <.001 | |||

| Underweight (<18.5) | 31 (4.0) | 23 (3.9) | 8 (4.3) | |

| Normal (18.5–24.99) | 308 (39.8) | 258 (44.0) | 50 (26.7) | |

| Overweight (25–29.99) | 204 (26.4) | 141 (24.0) | 63 (33.7) | |

| Obese (≥30) | 231 (29.8) | 165 (28.1) | 66 (35.3) | |

| Race | <.001 | |||

| AA | 359 (46.4) | 241 (41.1) | 118 (63.1) | |

| White | 193 (24.9) | 168 (28.6) | 25 (13.4) | |

| Hispanic (English spoken) | 81 (10.5) | 59 (10.1) | 22 (11.8) | |

| Hispanic (Spanish spoken) | 141 (18.2) | 119 (20.3) | 22 (11.8) | |

| Education | <.001 | |||

| Less than HS | 129 (16.7) | 99 (16.9) | 30 (16.0) | |

| High school | 289 (37.3) | 204 (34.8) | 85 (45.5) | |

| Some college | 220 (28.4) | 161 (27.4) | 59 (31.6) | |

| College or above | 123 (15.9) | 110 (18.7) | 13 (7.0) | |

| Missing | 13 (1.7) | 13 (2.2) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Insurance | <.001 | |||

| Public | 469 (60.6) | 331 (56.4) | 138 (73.8) | |

| Others | 305 (39.4) | 256 (43.6) | 49 (26.2) | |

| Income | 0.004 | |||

| 200% poverty line or less | 530 (68.5) | 386 (65.8) | 144 (77.0) | |

| >200% poverty line | 244 (31.5) | 201 (34.2) | 43 (23.0) | |

| Marital status | <.001 | |||

| Married | 265 (34.2) | 229 (39.0) | 36 (19.3) | |

| Single in relationship | 333 (43.0) | 240 (40.9) | 93 (49.7) | |

| Single not in relationship | 133 (17.2) | 90 (15.3) | 43 (23.0) | |

| Missing | 43 (5.6) | 28 (4.8) | 15 (8.0) | |

| Employment | 0.006 | |||

| Working | 331 (42.8) | 263 (44.8) | 68 (36.4) | |

| Not working | 421 (54.4) | 303 (51.6) | 118 (63.1) | |

| Missing | 22 (2.8) | 21 (3.6) | 1 (0.5) | |

| Diabetes | 0.325 | |||

| Yes | 51 (6.6) | 40 (6.8) | 11 (5.9) | |

| No | 708 (91.5) | 538 (91.7) | 170 (90.9) | |

| Missing | 15 (1.9) | 9 (1.5) | 6 (3.2) | |

| Sleep hours | 0.674 | |||

| ≤5 hr | 170 (22.0) | 131 (22.3) | 39 (20.9) | |

| > 5 hr | 604 (78.0) | 456 (77.7) | 148 (79.1) | |

| Smoking | 0.021 | |||

| Yes | 128 (16.5) | 85 (14.5) | 43 (23.0) | |

| No | 645 (83.3) | 501 (85.3) | 144 (77.0) | |

| Missing | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0) | |

| Vigorous exercise | 0.841 | |||

| Yes | 273 (35.3) | 206 (35.1) | 67 (35.8) | |

| No | 500 (64.6) | 380 (64.7) | 120 (64.2) | |

| Missing | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0) | |

| Moderate exercise | 0.024 | |||

| Yes | 443 (57.2) | 350 (59.6) | 93 (49.7) | |

| No | 327 (42.2) | 233 (39.7) | 94 (50.3) | |

| Missing | 4 (0.5) | 4 (0.7) | 0 (0) | |

| Planned pregnancy | <.001 | |||

| Yes | 263 (34.0) | 221 (37.6) | 42 (22.5) | |

| No | 469 (60.6) | 338 (57.6) | 131 (70.1) | |

| Missing | 42 (5.4) | 28 (4.8) | 14 (7.5) | |

| Hormonal birth control postpartum | 0.184 | |||

| Yes | 452 (58.4) | 335 (57.1) | 117 (62.6) | |

| No | 322 (41.6) | 252 (42.9) | 70 (37.4) | |

| Parity | 0.018 | |||

| Nulliparous | 256 (33.1) | 184 (31.3) | 72 (38.5) | |

| Multiparous | 511 (66.0) | 400 (68.1) | 111 (59.4) | |

| Missing | 7 (0.9) | 3 (0.5) | 4 (2.1) | |

| Breast feeding (ever) | 0.028 | |||

| Yes | 615 (79.5) | 477 (81.3) | 138 (73.8) | |

| No | 159 (20.5) | 110 (18.7) | 49 (26.2) | |

| Breast feeding at 1 month | <.001 | |||

| Yes | 336 (43.4) | 279 (47.5) | 57 (30.5) | |

| No | 385 (49.7) | 271 (46.2) | 114 (61.0) | |

| Missing | 53 (6.8) | 37 (6.3) | 16 (8.6) | |

| Breast feeding at 6 months | <.001 | |||

| Yes | 169 (21.8) | 152 (25.9) | 17 (9.1) | |

| No | 602 (77.8) | 432 (73.6) | 170 (90.9) | |

| Missing | 3 (0.4) | 3 (0.5) | 0 (0) | |

Data are mean±standard deviation or n (%) unless otherwise specified.

Strikingly, among the 39.8% women who had a normal BMI prior to pregnancy, 29.6% became overweight and 2% became obese by 1 year postpartum. Of the 26.5% women who were already overweight before pregnancy, 43.9% became obese by 1 year postpartum while 96.9% of the women who were obese prior to the pregnancy, remained obese at 1 year postpartum (p<.001).

Women gained a mean of 32 lbs during pregnancy. At 1 year postpartum, women retained a mean of 11.1 lbs (average 12 month postpartum BMI 29.4 kg/m2). Of the 774 women at 1 year postpartum, 579 (74.8%) were heavier than prepregnancy. Three hundred and sixty seven (47.4%) had retained 10 lbs or more and 187 (24.2%) had retained 20 lbs or more.

During the pregnancy, 416 (53.7%) of women gained more weight than the national recommendations.(15) Thirty-seven percent of normal weight women, 64.8% of overweight women, and 63% of obese women had excessive weight gain during the pregnancy. Women who gained more than the recommended amount during pregnancy were significantly more likely to be over 20 lbs heavier than their prepregnancy weight (p<0.001. Women with a normal prepregnancy weight who had excessive weight gain during pregnancy were also significantly more likely to retain over 20 lbs of weight postpartum (p=0.003).

Women who retained ≥20 lbs of postpartum weight were more likely to: be African American, be younger, have a high school education, be poor, receive Public Aid, and to work outside the home. Women who retained more than 20 lbs were less likely to: be in a relationship with the baby’s father, have planned the pregnancy, have breast fed or exercise (Table 2). As expected, women who started the pregnancy with an overweight or obese BMI were at greater risk of retaining more than 20 lbs postpartum. However, approximately one in six women who started the pregnancy with a normal BMI also retained more than 20 lbs weight at 1 year postpartum.

We defined three sets of variables based on the strength of the bivariate relationships and/or face validity, and then ordered these sets from least to most amenable to intervention. Then we conducted a series of nested linear regression models to predict postpartum weight retention in those who retained ≥20 lbs of postpartum weight (Table 3).

Table 3.

Multivariable Logistic Regression for women who retained ≥20 lbs postpartum at one year postpartum

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||||

| Variable | Adjusted Odds Ratio | 95% Confidential Interval | Adjusted Odds Ratio | 95% Confidential Interval | Adjusted Odds Ratio | 95% Confidential Interval | |||

| Age | 0.96* | 0.92 | 0.99 | 0.95* | 0.91 | 0.99 | 0.96 | 0.91 | 1.00 |

| African American | 2.21* | 1.31 | 3.71 | 1.75 | 0.95 | 3.23 | 1.51 | 0.81 | 2.81 |

| Hispanic-English | 1.65 | 0.82 | 3.33 | 1.40 | 0.63 | 3.12 | 1.36 | 0.61 | 3.03 |

| Hispanic-Spanish | 0.96 | 0.51 | 1.83 | 1.16 | 0.56 | 2.41 | 1.03 | 0.48 | 2.21 |

| Unplanned Pregnancy | 1.32 | 0.86 | 2.03 | 1.25 | 0.76 | 2.05 | 1.28 | 0.76 | 2.14 |

| Weight Gain During Pregnancy | 1.08* | 1.06 | 1.10 | 1.08* | 1.06 | 1.10 | |||

| Prepregnancy BMI: Underweight | 1.82 | 0.67 | 4.97 | 1.54 | 0.52 | 4.51 | |||

| Prepregnancy BMI: Overweight | 3.24* | 1.93 | 5.46 | 3.25* | 1.90 | 5.55 | |||

| Prepregnancy BMI: Obese | 3.75* | 2.22 | 6.34 | 3.72* | 2.17 | 6.38 | |||

| Public Insurance | 1.50 | 0.90 | 2.50 | 1.40 | 0.81 | 2.39 | |||

| Single: In a Relationship | 1.30 | 0.74 | 2.27 | 1.12 | 0.63 | 2.00 | |||

| Single: Not in a Relationship | 1.20 | 0.60 | 2.42 | 1.08 | 0.53 | 2.20 | |||

| Working at 6 Months | 0.72 | 0.47 | 1.12 | ||||||

| Breastfeeding at 6 Months | 0.46* | 0.24 | 0.87 | ||||||

| Sleeps < 5 Hours | 1.08 | 0.65 | 1.79 | ||||||

| Smokes at 6 Months | 1.14 | 0.66 | 1.98 | ||||||

| Moderate Exercise | 0.61* | 0.40 | 0.93 | ||||||

| Hormonal Birth Control Use | 0.88 | 0.50 | 1.54 | ||||||

|

| |||||||||

| C Statistics (95% CI) | 0.65 (0.62–0.68) | 0.80 (0.76–0.84) | 0.82 (0.78–086) | ||||||

| N | 731 | 712 | 684 | ||||||

p<.05

Model 1 identifies significant relations between maternal age and race. Older maternal age was protective against excessive postpartum weight retention (≥ 20 lbs) (OR 0.96; 95%CI 0.92–0.99). African-American race (OR 2.21; 95%CI 1.31–3.71) was highly related to weight retention while White race, Hispanic, and other race were not. Maternal age and race alone accounted for 65% of the variation in postpartum weight retention.

Older maternal age remains protective against excessive postpartum weight retention in Model 2. In addition, model 2 indicates that each additional pound of weight gain during pregnancy above the IOM recommendation increases the odds of excessive weight retention (≥ 20 lbs) by 8% at one year postpartum. Having a prepregnancy weight in the overweight BMI category was associated with an increase in the odds of postpartum weight retention of about 3.2-fold while those who were obese prior to pregnancy had a 3.8-fold higher risk of retaining weight at one year postpartum. Of note, because poverty level was highly correlated with public insurance, it was dropped from this model. Neither public insurance nor single parenthood contributed to higher risk of excessive postpartum weight retention in our population. Overall, Model 2 explains 80% of the variation in postpartum weight retention, a significant increase over Model 1 of 15%.

Model 3, the final model, includes all model 1 and 2 variables and adds lifestyle behaviors. Moderate exercise was associated with a decrease in the odds of postpartum excessive weight retention (OR=0.16; 95% CI 0.40–0.93). Breastfeeding until 6 months was also a decrease in the risk of excessive postpartum weight retention (OR=0.46; 95% CI 0.24–0.87). Postpartum lifestyle behaviors, as measured in CCHN, did not account for much additional variation in postpartum excessive weight retention, with a small improvement only in the group that was obese prepregnancy. The final model explained 82% of the variation in postpartum weight retention, indicating a very strong explanatory model overall.

Discussion

Our study confirms that pregnancy is a risk factor for women becoming overweight and obese, as many women do not lose the weight gained during pregnancy. Some other risk factors for postpartum weight retention in this predominantly low income population included younger age, being African American, high prepregnancy BMI, excessive weight gain during pregnancy, not breastfeeding, and lack of exercise postpartum. Unlike prior studies, we did not find lack of sleep or lower parity to be associated with postpartum weight retention.(15,16,17)

There have been studies on the prevention of excessive pregnancy weight gain that have shown limited success. (18,19). A review of 4 randomized controlled trials and 5 nonrandomized trials of strategies that focused on modifying gestational weight gain through physical activity and diet counseling showed that in all trials the intervention groups had lower gestational weight gains than the control groups.(20) Of particular note, given our findings that a significant number of women with a normal prepregnancy weight become overweight or obese by 1 year postpartum, interventions for preventing excessive pregnancy weight gain were more successful in normal weight women than in women already overweight or obese.

The benefits of breast feeding are well-known for both the mother and infant. Women who breast feed have decreased postpartum blood loss and more rapid involution of the uterus.(21) They also have less postpartum depression.(22) Our study also showed that women who met the American Academy of Pediatrics recommendation for 6 months of breast feeding were significantly less likely to have retained the weight gained in pregnancy at 1 year postpartum. The substantial benefit of breast feeding to maternal and child health should be communicated to women by health care providers during the pregnancy and reiterated postpartum.

One of the limitations of our study was the number of women who were excluded because a prepregnancy BMI was not available. However, we compared demographic characteristics between women with and without a prepregnancy BMI and found no statistically significant differences. Also this group of women was not selected randomly from the general population and they were oversampled for low income and preterm birth. While there is no reason to believe these women differ from other postpartum women in other ways, this may make the study less generalizable. Some of the socially undesirable variables such as smoking were self-reported which may be underreported. While we show an salutary effect of breastfeeding and exercise only in the group that was obese prior to pregnancy, this limited effect may be an artifact of CCHN’s measurement strategy, in that we could not separate partial from exclusive breastfeeding, and physical activity was self-reported and may be overreported. Nonetheless, we are encouraged to see that small changes have benefit among the most overweight (who are most at risk). As in any study, there may be other unexplored variables, but our model was very strong for explaining excessive postpartum weight retention (≥ 20 lbs).

In our opinion, providers of health care for pregnant women need to know the IOM recommendations, actively discuss weight gain during pregnancy with all patients–including those of normal weight–monitor weight gain, encourage daily exercise, and support nutrition counseling. Postpartum, health care providers should emphasize the target of breast feeding for six months and adopting a regular program of moderate exercise, particularly in women at high risk for postpartum weight retention: pregnancy at a younger age, African American race, high prepregnancy BMI and excessive weight gain during pregnancy. As obesity and its health consequences are critical national health issues, creative, synergistic interventions are urgently needed.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure: The authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Obesity and Overweight. Available at http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/overwt.htm. Retrieved June 2014.

- 2.Lashen H, Fear K, Sturdee DW. Obesity is associated with increased first trimester and recurrent miscarriage: matched case-control study. Hum Reprod. 2004;19:1644–6. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Weiss JL, Malone FD, Emig D, Ball RH, Nyberg DA, Comstock CH, et al. Obesity, obstetric complications and cesarean delivery rate: a population based screening study. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190:1091–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2003.09.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Waller DK, Mills JL, Sompson JL, Cunningham GC, Conley MR, Lassman ML, et al. Are obese women at higher risk for producing malformed offspring? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1994;170:541–8. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(94)70224-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cedergren MI, Kallen BA. Maternal obesity and infant heart defects. Obes Res. 2003;11:1065–71. doi: 10.1038/oby.2003.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Watkins ML, Rasmussen SA, Honeru MA, Botto LD, Moore CA. Maternal obesity and risk for birth defects. Pediatrics. 2003;111:1152–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nohr EA, Bech BH, Davies MJ, Frydenberg M, Henriksen TB, Olsen J. Prepregnancy obesity and fetal death: a study within the Danish National Birth Cohort. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:250–9. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000172422.81496.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chescheir NC. Global obesity and the effect on women’s health. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:1213–1222. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182161732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gunderson EP, Abrams B, Selvin S. The relative importance of gestational gain and maternal characteristics associated with the risk of becoming overweight after pregnancy. Inter J Obes Related Metabolic Disorders. 2000;24:1660–1668. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schauberger CW, Roonery BL, Brimer LM. Factors that influence weight loss in the puerperium. Obstet Gynecol. 1992;79:424–9. doi: 10.1097/00006250-199203000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Institute of Medicine. Weight gain during pregnancy: reexamining the guidelines. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Craig CL, Marshall AL, Sjostrom M, Bauman AE, Booth ML, Ainsworth BE, et al. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise. 2003;35:1381–95. doi: 10.1249/01.MSS.0000078924.61453.FB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vasconcelos CM, Costa FS, Almeida PC, Araujo JE, Sampaio HA. Risk factors associated with weight retention in the postpartum period. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet. 2014;36(5):222–7. doi: 10.1590/s0100-7203201400050007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rode L, Kjaergaard H, Ottesen B, Damm P, Hegaard HK. Association between gestational weight gain according to body mass index and postpartum weight in a large cohort of Danish women. Matern Child Health J. 2012;16(2):406–13. doi: 10.1007/s10995-011-0775-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gunderson EP, Abrams B, Selvin S. The relative importance of gestational gain and maternal characteristics associated with the risk of becoming overweight after pregnancy. Inter J Obesity. 2000;24:1660–68. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gunderson EP, Rifas-Shiman SL, Oken E, Rich-Edward JW, Kleinman KP, Taveras EM, et al. Association of fewer hours of sleep at 6 months postpartum with substantial weight retention at 1 year postpartum. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;167:178–87. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwm298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosenberg L, Palmer JR, Wise LA, Horton NJ, Kumanyika SK, Adams-Campbell LL. A prospective study of the effect of childbearing on weight gain in African-American women. Obesity Research. 2003;11:1526–35. doi: 10.1038/oby.2003.204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Phelan S, Phipps MG, Abrams B, Darroch F, Schaffner A, Wing RR. Randomized trial of a behavioral intervention to prevent excessive gestational weight gain: the Fit for Delivery Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2011 doi: 10.3945/ajcn.110.005306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vinter CA, Jenson DM, Ovesen P, Beck-Nielson H, Jorgensen JS. A randomized controlled trial of lifestyle intervention in 360 obese pregnant women. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:2502–7. doi: 10.2337/dc11-1150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Streuling I, Beyerlein A, von Kries R. Can gestational weight gain be modified by increasing physical activity and diet counseling? A meta-analysis of interventional trials. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;92:678–87. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2010.29363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Breastfeeding. Breastfeeding and the use of human milk. Pediatrics. 2012;129:e827–41. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-3552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Henderson JJ, Evans SF, Straton JA, Priest SR, Hagan R. Impact of postnatal depression on breastfeeding duration. Birth. 2003;30(3):175–80. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-536x.2003.00242.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]