Abstract

This four-wave prospective longitudinal study evaluated stability of language in 324 children from early childhood to adolescence. Structural equation modeling supported loadings of multiple age-appropriate multi-source measures of child language on single-factor core language skills at 20 months and 4, 10, and 14 years. Large stability coefficients (standardized indirect effect = .46) were obtained between language latent variables from early childhood to adolescence and accounting for child nonverbal intelligence and social competence and maternal verbal intelligence, education, speech, and social desirability. Stability coefficients were similar for girls and boys. Stability of core language skill was stronger from 4 to 10 to 14 years than from 20 months to 4 years, so early intervention to improve lagging language is recommended.

The development in “child development” normally draws our attention to two complementary aspects of whether children remain the same or change over time. One aspect is continuity/discontinuity and concerns consistency in mean level in a group of children over time. For example, children as a group normally improve in many components of language as they grow. The other aspect is stability/instability and concerns consistency in individual differences over time. For example, stability in language obtains when some children display a relatively high level of language at one point in time vis-à-vis their peers and continue to display high levels at later points in time, while other children display low levels at all times. This article is principally concerned with long-term stability of individual differences in child language.

The study of stability in child development is important for many reasons (Bornstein, Tamis-LeMonda, & Haynes, 1999; McCall, 1981; Wohlwill, 1973). Stability can enlighten about individual differences (whether children maintain their relative order through time in terms of their language informs about individual children); stability can edify about the origins, nature, and overall ontogenetic course of a psychological phenomenon (if language is stable it contributes to understanding how language functions and develops); stability can help to establish that a measure constitutes a meaningful individual-differences metric (stable language skills imply that performance over time is regular and not simply test-specific or spurious); and stability can signal developmental status and so affect the child’s environment and experience (insofar as language is ontogenetically stable, children who do well or poorly at one time are likely to do well and poorly again later, and people respond in different ways to children who are consistently low or high in their language).

This study also addressed three issues directly related to stability in child language. Language is multidimensional and componential, encompassing expressive and receptive domains of phonology, morphology, semantics, syntax, and pragmatics. Empirically, language stability studies normally examine single measures of individual components, which have generally proved stable in the short-term; however, estimates of language stability vary with the domain and with measure, method, source, and context as well as the age at assessment and the temporal interval between assessments (for a review and references, see Supporting Materials). The different methods for studying child language – recording what children say, seeking out those people closest to children (like their parents) to report about them, and testing children – each offers a unique perspective with implications for stability (maternal reports of child language might be stable, but observations not). Beside the method and source of information, when a stability assessment begins (a characteristic may not be stable at an early age but stabilize at a later age) and the time interval between assessments (the shorter the inter-assessment interval, normally the greater the stability estimate) both affect stability. Because, different assessment contents, procedures, and intervals contribute to different stability estimates of child language, and no one approach is superior to others under all situations, we re-visited the issue of stability in language development from early childhood to adolescence adopting a latent variable approach that capitalizes on the shared contributions of diverse methods. Examining latent variables of child language at each of several ages was a second purpose of the study.

The prevailing multidimensional and componential conceptualization assumes that language domains are partially independent of one another. However, different domains of language also covary suggesting that core language skill contributes to all domains. In this study, we determined whether and how well several different language domains, measures, and sources converge on single latent variables of a core child language skill at each of four ages and whether these latent variables were stable in a longitudinal assessment. Latent variables rely on empirical covariation among their indicators, and there is evidence in the child language literature that supports such covariation. In one multimethod approach, principal components analysis of five diverse language measures yielded a single factor that accounted for 65% of their common variance (Johnson et al., 1999). In a second, seven assorted measures of language were found to intercorrelate and to constitute a general factor of language (Colledge et al., 2002). In a third, analysis of nine distinct language measures yielded a general factor that accounted for 30% of the total variance (Trouton, Spinath, & Plomin, 2002). In a fourth, items reflecting sundry language components were examined at four time points across the age range of 6 to 14 years; at each wave, evidence of a dominant single factor emerged (Tomblin & Zhang, 2006). Thus, variance in many different measures of language appears to be attributable to a single common factor. Here we re-examined this proposition with multiple language measures at each of four ages between early childhood and adolescence.

Language development is acknowledged to differ in typically developing girls and boys (Feldman et al., 2000; Van Hulle, Goldsmith, & Lemery, 2004). Girls’ (usually slight but consistent) mean-level advantage might be based on different gender-related developmental timetables, treatment, interests, and learning opportunities (Bornstein, Hahn, & Haynes, 2004). Girls and boys might also differ in language stability. Perhaps girls’ early advantage in communication proffers some environmental advantages (e.g., more communicative children elicit more verbal responses and linguistic opportunities from others) which then maintain girls’ relatively higher position (i.e., stability). Third, therefore, we evaluated whether long-term stability in the child language latent variables (core child language skill) differed by child gender.

Stability is usually ascribed to temporal consistency of a characteristic in the individual. However, a deeper understanding of stability and its accurate attribution necessitate simultaneous examination of factors that influence or confound it. Stability of core child language skill might reflect a related but different stable characteristic in the child (nonverbal intelligence; Tamis-LeMonda, & Bornstein, 1990), stability might reflect a stable environment that consistently supports language consistency (maternal language addressed to the child; Bornstein et al., 1999), or stability might reflect the interaction of the two. Most studies of language stability do not take other endogenous or exogenous factors into consideration to rule out sources of stability alternative to the child and to assign stability to the child more unambiguously. Fourth, therefore, we assessed whether core child language skill is stable in itself, or if any of multiple candidate general and specific third variables that covary with child language (children’s nonverbal intelligence and social competence as well as maternal verbal intelligence, education, speech, and social desirability bias) account for language stability in the child.

In overview, this study adds to the extant child development and language literatures by assessing multiple language domains using age-appropriate measures and multiple sources to evaluate their empirical covariation in latent variables at each of several ages across childhood and the long-term stability between latent variables of language from the end of infancy to early adolescence in a relatively large sample. We assessed measurement models and the fit of two structural models to the data: one for the common convergences of multiple measures from different sources on single latent variables of core child language skill at 20 months and 4, 10, and 14 years, respectively, and the stability between those latent variables, and the second model for stability among the language latent variables controlling multiple general and specific covariates. Gender differences in stability were also assessed.

Method

Brief summaries of the methods follow; details about participants, procedures, measure and instrument psychometrics, and scoring are available in the Supporting Materials.

Participants

Altogether, 324 European American firstborn, healthy, typically developing, monolingual American English-speaking children (150 girls and 174 boys) participated. On average, children were 20.09 months (SD = 0.23, n = 306), 4.05 years (SD = 0.09, n = 265), 10.26 years (SD = 0.17, n = 229), and 13.87 years of age (SD = 0.27, n = 186) at the first, second, third, and fourth assessment waves. Mothers averaged 31.06 years old (SD = 6.37) at the first assessment and varied widely in education attainment. Family SES ranged from 14 to 66 (M = 50.09, SD = 13.06) on the Hollingshead (1975) Four-Factor Index of Social Status.

Procedures

At 20 months and 4 years, we obtained samples of children’s spontaneous speech derived from transcripts of videorecorded sessions. At all 4 ages, multiple measures of age-appropriate domains of language were obtained from maternal report and experimenter assessment.

20 months

Child observation: Children’s language was derived from verbatim transcripts of their spontaneous speech in a free-play interaction with their mothers at home. Two measures of each child’s language were calculated using the Codes for Human Analysis of Transcripts (CHAT, MacWhinney, 2000): mean length of utterance (MLU), the complexity of speech, and different word roots (DWR), a count of the number of different lexical items in the child’s speech. Maternal report: The Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales - Interview Edition, Survey Form (VABS; Sparrow, Balla, & Cicchetti, 1984) Communication Domain was used to obtain mothers’ estimates of their children’s receptive and expressive communication skills. Mothers also completed the Early Language Inventory (ELI; Bates, Bretherton, & Snyder, 1988), a forerunner of the MacArthur Communicative Development Inventories (CDI; Fenson, Thal, & Bates, 1990; Fenson et al., 1993, 1994), that provides a measure of children’s expressive vocabulary. Experimenter assessment: An experimenter administered the Verbal Comprehension Scale ‘A’ and the Expressive Language Scale of the Reynell Developmental Language Scales-Second Revision (RDLS; Reynell & Gruber, 1990). Children’s standard language scores for comprehension and production were used.

4 years

Child observation: Measures of children’s spontaneous language were derived from verbatim transcripts of their videorecorded storytelling. Children’s MLU and DWR were calculated in the same manner described for 20 months. Maternal report: As at 20 months, the VABS was again used to obtain mothers’ estimates of children’s communication skills. Experimenter assessment: An experimenter administered two verbal subtests of the Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scale of Intelligence-Revised (WPPSI-R; Wechsler, 1989): Information and Similarities.

10 years

Maternal report. The VABS was again used to obtain mothers’ estimates of children’s communication skills. Experimenter assessment: An experimenter administered three verbal subtests (Information, Similarities, and Vocabulary) of the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children, 3rd Edition (WISC III; Wechsler, 1991) and two subtests (Letter-Word Identification and Passage Comprehension) from the Woodcock–Johnson Psycho-Educational Battery–Revised (WJ–R; Woodcock & Johnson, 1990) Test of Achievement.

14 years

Maternal report: The VABS was again used to obtain mothers’ estimates of children’s communication skills. Experimenter assessment: An experimenter administered three subtests (Letter-Word Identification, Passage Comprehension, and Dictation) from the WJ–R.

Covariates

Based on the extensive body of research on factors associated with child language, we included six candidate general and specific covariates that might promote and sustain language stability. We assessed the possibilities that child nonverbal intelligence might underlay language competence and performance (Tamis-LeMonda, & Bornstein, 1990), child social competence might influence their language during experimenter assessments, mothers’ verbal intelligence and education (obtained from the Hollingshead) might influence child language, mothers’ speech during mother-child interactions might influence child speech (Bornstein et al., 1992; Bornstein, Tamis-LeMonda, Hahn, & Haynes, 2008; Vibbert & Bornstein, 1989), and mothers’ social desirability might bias maternal reports.

Results

Analytic Plan

Details of preliminary analyses and a more thorough analytic plan are available in the Supporting Materials. Briefly, we fit structural equation models (SEMs) using Maximum Likelihood Functions and followed the mathematical models of Bentler and Weeks (1980) as implemented in EQS 6.1 (Bentler, 2006). Missing data (25.2% of the total data points were missing completely at random; Little’s MCAR test χ2(909) = 979.90, ns) were handled in EQS using full information maximum likelihood (Jamshidian & Bentler, 1999).

Model fit was assessed using the robust Yuan-Bentler (Y-B) scaled χ2 statistic, robust comparative fit index (CFI), the standardized root mean squared residual (SRMR; Browne & Cudeck, 1993), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). Cutoff values ≈.95 for CFI and ≈.09 and ≈ .06 for SRMR and RMSEA, respectively, are indicative of a relatively good fit between a hypothesized model and observed data (Hu & Bentler, 1999). We gave greater weight to the incremental fit indices than to χ2 because the χ2 value is known to be sensitive to sample size (Cheung & Rensvold, 2002) and the size of the correlations in the model (Miles & Shelvin, 2006). Standardized path coefficients are presented in text and figures.

To obtain stability estimates across ages, an a priori model in which language indicators at each of the four ages loaded on their respective latent variables, and each language latent variable was a function of the immediately preceding language latent variable, was hypothesized and tested. After fitting the a priori model on the full sample, we performed multiple-group analysis on girls and boys to test for gender differences in stability. If the Δχ2 between the unconstrained and constrained models was nonsignificant (p > .05) and the ΔCFI ≤ .01 (Cheung & Rensvold, 2002; Vandenberg & Lance, 2000), the model was deemed to fit equally well in girls and boys.

Finally, the language stability model was reassessed controlling multiple general and specific covariates. General covariates (maternal education and verbal intelligence) were presumed to be associated with all child language variables, regardless of the child’s age. Specific covariates were presumed to be associated with specific types of child language variables (e.g., maternal reports) or specific ages (e.g., 20 months). Consequently, general covariates were included as observed variables in the model, and specific covariates were controlled by removing shared variance in the relevant language indicators before fitting the model.

Language from 20 Months to 4 Years to 10 Years to 14 Years

Descriptive statistics

Table 1 shows the Ms, SDs, and ranges of language measures for the total sample. Children scored well within the normal range on maternal report and experimenter assessments of their language. The standard deviations and ranges on all language measures indicate considerable variation in child language, as are commonly found in the literature.

Table 1. Child Language Measures: Descriptive Statistics and Pair-wise Variance Covariance Matrix.

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20 months | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 1. MLU | 1.01 | ||||||||||||||||||||

| 2. DWR | .51 | .99 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 3. VABS Communication | .29 | .56 | 1.00 | ||||||||||||||||||

| 4. ELI | .39 | .62 | .70 | 1.00 | |||||||||||||||||

| 5. Reynell Comprehension | .23 | .42 | .47 | .51 | 1.00 | ||||||||||||||||

| 6. Reynell Expression | .40 | .74 | .68 | .80 | .58 | 1.00 | |||||||||||||||

| 4 years | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 7. MLU | .10 | .21 | .31 | .33 | .22 | .33 | 1.00 | ||||||||||||||

| 8. DWR | .05 | .17 | .22 | .25 | .15 | .18 | .44 | 1.00 | |||||||||||||

| 9. VABS Communication | .11 | .34 | .48 | .49 | .39 | .47 | .17 | .08 | 1.00 | ||||||||||||

| 10. WPPSI-R Verbal Information | .03 | .17 | .35 | .36 | .47 | .36 | .22 | .20 | .43 | 1.05 | |||||||||||

| 11. WPPSI-R Verbal Similarity | .07 | .24 | .34 | .36 | .37 | .37 | .16 | .04 | .38 | .54 | 1.02 | ||||||||||

| 10 years | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 12. VABS Communication | .10 | .14 | .24 | .24 | .27 | .20 | .14 | .04 | .30 | .26 | .20 | 1.04 | |||||||||

| 13. WJ-R Passage Comprehension | .07 | .09 | .26 | .29 | .34 | .30 | .16 | .14 | .37 | .48 | .34 | .43 | 1.01 | ||||||||

| 14. WJ-R Letter-Word Identification | .03 | .19 | .26 | .37 | .29 | .35 | .21 | .05 | .38 | .38 | .44 | .38 | .62 | 1.07 | |||||||

| 15. WISC III Verbal Information | −.01 | .08 | .21 | .20 | .30 | .20 | .17 | .13 | .29 | .42 | .39 | .27 | .56 | .53 | .99 | ||||||

| 16. WISC III Verbal Similarity | −.02 | .13 | .29 | .33 | .33 | .32 | .19 | .18 | .35 | .50 | .44 | .27 | .49 | .52 | .60 | 1.01 | |||||

| 17. WISC III Vocabulary | .02 | .17 | .32 | .32 | .37 | .33 | .19 | .18 | .40 | .53 | .45 | .33 | .66 | .56 | .69 | .60 | 1.00 | ||||

| 14 years | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 18. VABS Communication | −.06 | .08 | .11 | .10 | .16 | .09 | .07 | .16 | .42 | .24 | .22 | .41 | .42 | .35 | .32 | .34 | .33 | 1.00 | |||

| 19. WJ-R Passage Comprehension | −.01 | .13 | .19 | .27 | .31 | .25 | .27 | .10 | .46 | .47 | .43 | .35 | .65 | .64 | .60 | .49 | .67 | .38 | 1.00 | ||

| 20. WJ-R Letter-Word Identification | −.11 | .09 | .15 | .20 | .21 | .24 | .19 | .05 | .39 | .38 | .31 | .25 | .50 | .80 | .47 | .47 | .50 | .21 | .54 | 1.00 | |

| 21. WJ-R Dictation | −.07 | .06 | .12 | .18 | .25 | .18 | .21 | .01 | .48 | .35 | .31 | .35 | .56 | .72 | .50 | .40 | .51 | .36 | .56 | .67 | 1.00 |

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| M | 1.35 | 2.20 | 103.73 | 135.05 | 105.66 | 100.44 | 5.46 | 8.40 | 106.92 | 11.93 | 10.67 | 106.92 | 116.56 | 115.87 | 13.90 | 13.73 | 13.72 | 99.34 | 119.14 | 114.65 | 99.07 |

| SD | 0.32 | 1.49 | 12.84 | 108.67 | 20.09 | 18.94 | 1.73 | 3.34 | 9.31 | 2.87 | 2.52 | 12.42 | 11.04 | 14.20 | 3.09 | 2.65 | 3.15 | 11.77 | 16.93 | 13.82 | 16.11 |

| Range | 0-2.88 | 0-8.40 | 74-141 | 0-487 | 64-136 | 64-136 | 0-13.35 | 0-15.88 | 81-138 | 3-19 | 3-18 | 75-129 | 86-150 | 84-150 | 5-19 | 4-19 | 4-22 | 70-121 | 91-176 | 91-157 | 71-153 |

Note. MLU = mean length of utterance in morphemes. DWR = Different word roots. VABS = Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales. ELI = Early Language Inventory. WPPSI-R = Wechsler Preschool and Primary Scales of Intelligence-Revised. WISC-III = Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children-Third Edition. WJ-R = Woodcock-Johnson Psycho-Educational Battery–Revised. In the pair-wise variance covariance matrix, all variables are scaled by constants so that variables’ variances were ≈ 1.

Stability of core language skill

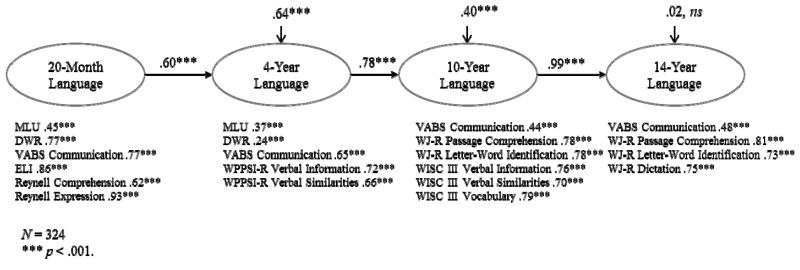

The a priori model fit the data well: robust Y-B scaled χ2(186) = 463.19, p < .001, Robust CFI = 1.00, SRMR = .08, RMSEA = .00. Figure 1 presents the standardized solution of this stability model. Table 1 also displays the pair-wise variance covariance matrix of the 21 language measures on the total sample.

Figure 1.

Model of stability among child language latent variables from ages 20 months to 14 years. Numbers associated with single-headed arrows are standardized path coefficients; numbers associated with dependent variables are disturbances, the amount of variance not accounted for by paths in the model. Indicators of each language latent variable are listed below the latent variable with their factor loadings.

All indicators of child language loaded significantly on their factors at each age, which indicated that various measures of language formed stable, single factors of a core language skill at each age. Much of the variance in various language measures was explained by its respective factor: The average percentages of variance explained by their language factors were 56%, 31%, 52%, and 50%, respectively, for the 20-month, 4-, 10-, and 14-year language measures. Stability of core child language skills was large between each succeeding time point and was larger between 4 and 10 years, Δχ2(1) = 13.08, p < .001, and 10 and 14 years, Δχ2(1) = 16.93, p < .001, than between 20 months and 4 years. The stabilities between 4 and 10 years and 10 and 14 years did not differ, Δχ2(1) = 0.05, ns. The standardized estimate of core language skill stability from 20 months to 14 years, with indirect effects mediated by interim core language skills, was .46, p < .001; 21% of the variance in the 14-year core language skill was accounted for by the 20-month core language skill, as mediated through 4- and 10-year core language skills.

Stability of core language skill X gender

A preliminary multi-group model, in which no parameter estimates were constrained to be equal between girls and boys, fit the data, robust Y-B scaled χ2(372) = 699.92, p < .001, Robust CFI = 1.00, SRMR = .10, RMSEA = .00, suggesting that the same “model form” (Bollen, 1989) could be applied to both genders and more restrictive tests were appropriate. To test gender differences on stability estimates, we first demonstrated that the four language latent variables in the model were similar constructs for girls and boys (i.e., metric invariance: no gender difference on factor loadings) and that variances of the language latent variables were comparable across gender. Homogeneity of factor variance was tested to assure that any difference in stability estimates would not be caused by restricted range of factor variance in either group. We conducted a series of nested models that sequentially introduced constraints on factor loadings, factor variance, and finally the stability estimates (Bollen, 1989; Steenkamp & Baumgartner, 1998; Taris, Bok, & Meijer, 1998).

The difference in χ2 statistics of the two nested models testing measurement invariance, the constrained model with invariance constraints on all factor loadings and the unconstrained model with no invariance constraints, was not significant, Δχ2(17) = 16.83, ns, ΔCFI = .00. Full metric invariance was established for all four language latent variables suggesting that the four language latent variables were similar constructs for girls and boys. The differences in χ2 statistics of the two nested models testing homogeneity of factor variance, the constrained model (with invariance constraints on all factor loadings and the four factor variances) and the unconstrained model (with invariance constraints only on factor loadings), was not significant, Δχ2(4) = 2.13, ns, ΔCFI = .00. Homogeneity of factor variances was established for both genders.

To compare stability estimates across gender, we computed a final multi-group analysis. The difference in χ2 statistics of two nested models, the more constrained model (with invariance constraints on factor loadings, factor variances, and the three stability coefficients) and the less constrained model (with invariance constraints only on factor loadings and factor variances), was not significant, Δχ2(3) = 6.90, ns, ΔCFI = .00; this indicates that stability coefficients of core language skill were similar for girls and boys. Across ages from 20 months to 14 years, the standardized estimates of core language skill stability from the multi-group model without imposing any invariance constraints were .54 and .43 for girls and boys, respectively, ps < .001.

Stability of core language skill, controlling covariates

As a check against threats to the validity of the model, we explored whether several covariates were associated with specific child language measures. Table SM1 shows descriptive statistics of the covariates for the total sample. We calculated concurrent correlations of (1) child nonverbal intelligence with all language measures; (2) child social competence with observation and experimenter reports on the Reynell scales at 20 months, MLU and DWR at 20 months and 4 years, WPPSI-R scales at 4 years, WISC-III scales at 10 years, and WJ-R subtests at 10 and 14 years; (3) maternal MLU and DWR with child MLU and DWR, respectively, at 20 months and 4 years; and (4) maternal social desirability bias with maternal reports on the ELI at 20 months and VABS at all four ages. Several covariates related to child language at the zero-order level (see Table SM1). To test whether the stability model of core language skill held controlling for specific covariates and the two general covariates, we re-evaluated the a priori model (Figure 1) using adjusted language scores with the shared variance with specific covariates removed, and adding the two general covariates as exogenous variables to the SEM. Direct paths from maternal education and verbal intelligence to all four child language latent variables were added to the model. Figure 2 shows the final covariate model; it fit the data well: robust Y-B scaled χ2(220) = 583.51, p < .001, Robust CFI = 1.00, SRMR = .09, RMSEA = .00. The standardized estimate of core language skill stability from 20 months to 14 years, with indirect effects mediated by interim language measures, was .33, p < .001, controlling for child social competence and nonverbal intelligence and maternal verbal intelligence, education, speech, and social desirability bias. Controlling for specific and general covariates, the stability of core language skill was still large between successive longitudinal waves over a 12-year interval.

Figure 2.

Covariate model of stability among child language latent variables from ages 20 months to 14 years. Numbers associated with single-headed arrows are standardized path coefficients; numbers associated with double-headed arrows are standardized covariance estimates; numbers associated with dependent variables are disturbances, the amount of variance not accounted for by paths in the model. Indicators (adjusted scores controlling for specific covariates) of each language latent variable are listed below the latent variable with their factor loadings.

Discussion

Clear evidence emerged for strong long-term stability of individual variation in core language skill from the end of infancy to adolescence. Stability did not differ between girls and boys. Long-term stability also obtained independent of child sociability and nonverbal intelligence and maternal intelligence, education, speech, and social desirability bias. When multiple domains, measures, and sources are assessed at a variety of child ages, core language skill emerges as a robust and stable individual-differences characteristic of typically developing children. Multiple assessments take more aspects of core language skill into account, and latent variables give more precise estimates of the underlying construct by removing the unshared variance (specific variance and measurement error; Kline, 1998) of the indicators. This study points to the value of measuring diverse components of language in different ways using multiple informants to obtain a picture of children’s core language skill and its development.

Different language measures from different data sources satisfactorily converged on consistent and coherent pictures of underlying language latent variables at each of four ages and in girls and boys over more than 12 years of development from the end of infancy to adolescence. Our data reveal that fair amounts of variance are accounted for at each age, and these results add to the validity of the model. This is another indication that disparate language measures from different sources tap the same underlying construct. Latent variables incorporate the perspectives of multiple methods, domains, and reporters of child language. Language at different ages manifests differently, but latent variables at each age are allowed to have different age-appropriate indicators and different loadings for the same indicators. Using latent variables therefore allows for the measurement of core language skills to vary (appropriately) across time (as the construct does) but keeps comparability presumptive to stability assessment.

Development is governed by genetic and biological factors in combination with environmental influences and experiences. Stability of language could be attributable to factors in the individual or stability might emerge through the individual’s transactions with a consistent environment or both. Individuals are also active agents in their own development (e.g., Bornstein, Toda, Azuma, Tamis-LeMonda, & Ogino, 1990; Lerner, Lewin-Bizan, & Warren, 2011). For example, a verbally precocious child may elicit richer language input, thereby maintaining the child’s linguistic advantage. We did not measure (and so eliminate) all possible factors in children (brain function, motivation, persistence), but we did measure and so eliminate (i.e., control) as factors in stability child nonverbal intelligence and social competence. A consistent environment or experience can also carry stability. In this regard, we included as covariates maternal verbal intelligence, education, and speech to the child as representative of diverse experiential and environmental factors known to affect child language. The extent to which stability of core language skill in children reflects those circumstances is somewhat clarified as well by the multiple-covariate follow-up analyses we brought to bear on our original stability findings. Significant long-term stability obtained (but was slightly reduced) separate and apart from all these endogenous and exogenous covariates. The fact that stability of core language skill persisted, even under multiple controls, suggests that general language ability is a highly conserved and robust individual characteristic. Language development is almost certainly predicted by a complex interplay of genetic and biological dispositions in combination with socialization and experience. The covariates employed in this study were diverse, but not comprehensive of all predictors of language stability and did not account for gene-environment interactions. It is also possible that some early experience of the child before the start of this study set the child’s language development on a particular course (e.g., a sensitive period for environmental exposure; Bornstein, 1989), as in a cascade (Bornstein, Hahn, & Suwalsky, 2013; Bornstein, Hahn, & Wolke, 2013; Masten & Cicchetti, 2010). Development in some domains can be viewed as a hierarchically organized series of abilities that become increasingly differentiated over time. In development, each ability incorporates prior ones. Language may be so hierarchically organized, as later appearing skills subsume and build on earlier appearing ones (Lewontin, 2005).

Finally, we found no systematic differences in core language skill stability between girls and boys. The fact that stability of core language skill from the end of infancy to adolescence transcends gender further underscores the robustness of the basic result and suggests that the mechanisms underlying stability of core language skill are likely similar for both groups of children.

Questions of stability and change have framed debates in theory and research across the history of developmental science (Lerner et al., 2011). Our models suggest that the common variance in multiple measures of language ability at each age (core language skill) is stable across time, and that the unshared variance (measurement error and measure-specific variance) was not stable across time, as indicated by the lack of covaried error terms across time. To be stable, however, does not mean to be immutable or impervious to change or intervention. For example, our relatively robust estimate of stability (.46) from 20 months to 14 years leaves 79% of the variance in the 14-year core language skill unexplained by the 20-month core language skill through 4- and 10-year language. Similarly, the .78 stability coefficient from 4 to 10 years leaves 39% of the variance in the 10-year core language skill unexplained by 4-year language. Language is ultimately modifiable and plastic. Children can change in their relative standing with respect to language, just as they do more evidently in their mean level, as they grow. In our study, as children aged past age 4 years there was less change (instability) in language, so early intervention to improve lagging language skills is recommended. The nearly total stability from 10 to 14 years implies that changing core language skill this late in development is rare, whereas the .60 coefficient between 20 months and 4 years implies that 64% of the variance in 4-year core language skill was not explained by 20-month language. Hence, core language skill is likely to be more malleable at earlier ages. In language acquisition, development appears to balance the advantages of stability with the adaptive value of early susceptibility to change.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, NICHD.

References

- Bates E, Bretherton I, Snyder L. From first words to grammar: Individual differences and dissociable mechanisms. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge, England: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM. EQS 6 structural equations program manual. Multivariate Software; Encino, CA: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Bentler PM, Weeks DG. Linear structural equations with latent variables. Psychometrika. 1980;45:289–308. [Google Scholar]

- Bollen KA. Structural equations with latent variables. Wiley; New York: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH. Sensitive periods in development: Structural characteristics and causal interpretations. Psychological Bulletin. 1989;105:179–197. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.105.2.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH, Hahn C-S, Haynes OM. Specific and general language performance across early childhood: Stability and gender considerations. First Language. 2004;24:267–304. [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH, Hahn C-S, Wolke D. Systems and cascades in cognitive development and academic achievement. Child Development. 2013;84:154–162. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01849.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH, Hahn C-S, Suwalsky JTD. Physically developed and exploratory young infants contribute to their own long-term academic achievement. Psychological Science. 2013 doi: 10.1177/0956797613479974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH, Tal J, Rahn C, Galperín CZ, Pêcheux M-G, Lamour M, Azuma H, Toda S, Ogino M, Tamis-LeMonda CS. Functional analysis of the contents of maternal speech to infants of 5 and 13 months in four cultures: Argentina, France, Japan, and the United States. Developmental Psychology. 1992;28:593–603. [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH, Tamis-LeMonda CS, Hahn C-S, Haynes OM. Maternal responsiveness to very young children at three ages: Longitudinal analysis of a multidimensional modular and specific parenting construct. Developmental Psychology. 2008;44:867–874. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.44.3.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH, Tamis-LeMonda CS, Haynes OM. First words in the second year: Continuity, stability, and models of concurrent and predictive correspondence in vocabulary and verbal responsiveness across age and context. Infant Behavior and Development. 1999;22:65–85. [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH, Toda S, Azuma H, Tamis-LeMonda CS, Ogino M. Mother and infant activity and interaction in Japan and in the United States: II. A comparative microanalysis of naturalistic exchanges focused on the organization of infant attention. International Journal of Behavioral Development. 1990;13:289–308. [Google Scholar]

- Browne MW, Cudeck R. Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In: Bollen KA, Long JS, editors. Testing structural equation models. Sage; Beverly Hills, CA: 1993. pp. 136–162. [Google Scholar]

- Cheung GW, Rensvold RB. Evaluating goodness-of-fit indexes for testing measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling. 2002;9:233–255. [Google Scholar]

- Colledge E, Bishop DVM, Koeppen-Schomerus G, Price TS, Happé FGE, Eley TC, Dale PS, Plomin R. The structure of language abilities at 4 years: A twin study. Developmental Psychology. 2002;38:749–757. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.38.5.749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldman HM, Dollaghan CA, Campbell TF, Kurs-Lasky M, Janosky JE, Paradise JL. Measurement properties of the MacArthur Communicative Development Inventories at ages one and two years. Child Development. 2000;71:310–322. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenson L, Dale PS, Reznick JS, Bates E, Thal DJ, Pethick SJ. Variability in early communicative development. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development. 1994;59:1–173. Serial No. 242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenson L, Dale P, Reznick JS, Thal D, Bates E, Hartung J, Pethick S, Reilly J. The MacArthur Communicative Development Inventories: User’s guide and technical manual. Singular Publishing Group; San Diego: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Fenson L, Thal D, Bates E. San Diego State University; San Diego: 1990. Normed values for the ‘Early Language Inventory’ and three associated parent report forms for language assessment. Technical Report. [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead AB. The four-factor index of social status. Yale University; 1975. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Hu LT, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 1999;6:1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Jamshidian M, Bentler PM. ML estimation of mean and covariance structures with missing data using complete data routines. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics. 1999;24:21–24. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson CJ, Beitchman JH, Young A, Escobar M, Atkinson L, Wilson B, Brownlie EB, Douglas L, Taback N, Lam I, Wang M. Fourteen-year follow-up of children with and without speech/language impairments: Speech/language stability and outcomes. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 1999;42:744–760. doi: 10.1044/jslhr.4203.744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford Press; New York: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Lerner RM, Lewin-Bizan S, Warren AEA. Concepts and theories of human development. In: Bornstein MH, Lamb ME, editors. Developmental science: An advanced textbook. 6th ed. Psychology Press; New York: 2011. pp. 3–49. [Google Scholar]

- Lewontin R. The triple helix. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- MacWhinney B. The CHILDES Project: Tools for Analyzing Talk. Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS, Cicchetti D. Developmental cascades. Development and Psychopathology. 2010;22:491–495. doi: 10.1017/S0954579410000222. doi:10.1017/S0954579410000222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCall RB. Nature–nurture and the two realms of development: A proposed integration with respect to mental development. Child Development. 1981;52:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Miles J, Shelvin M. A time and a place for incremental fit indices. Personality and Individual Differences. 2006;42:869–874. [Google Scholar]

- Reynell JK, Gruber CP. Reynell Developmental Language Scales U. S. Edition. Western Psychological Services; Los Angeles, CA: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Sparrow SS, Balla DA, Cicchetti DV. Vineland Adaptive Behavior Scales Survey Form Manual (Interview Edition) American Guidance Service; Circle Pines, MN: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Steenkamp JEM, Baumgartner H. Assessing measurement invariance in cross-national consumer research. Journal of Consumer Research. 1998;25:78–90. [Google Scholar]

- Tamis-LeMonda CS, Bornstein MH. Language, play, and attention at one year. Infant Behavior and Development. 1990;13:85–98. [Google Scholar]

- Taris TW, Bok IA, Meijer ZY. Assessing stability and change of psychometric properties of multi-item concepts across different situations: A general approach. The Journal of Psychology. 1998;132:301–316. [Google Scholar]

- Tomblin JB, Zhang X. The dimensionality of language ability in school-age children. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2006;49:1193–1208. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2006/086). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trouton A, Spinath FM, Plomin R. Twins early development study (TEDS): A multivariate, longitudinal genetic investigation of language, cognition and behavior problems in childhood. Twin Research: The Official Journal of the International Society for Twin Studies. 2002;5:444–448. doi: 10.1375/136905202320906255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandenberg RJ, Lance CE. A review and synthesis of the measurement invariance literature: Suggestions, practices, and recommendations for organizational research. Organizational Research Methods. 2000;3:4–69. [Google Scholar]

- Van Hulle C, Goldsmith H, Lemery K. Genetic, environmental, and gender effects on individual differences in toddler expressive language. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research. 2004;47:904–912. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2004/067). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vibbert M, Bornstein MH. Specific associations between domains of mother-child interaction and toddler referential language and pretense play. Infant Behavior and Development. 1989;12:163–184. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. The Psychological Corporation; San Antonio, TX: 1989. Wechsler preschool and primary scale of intelligence--Revised: Manual. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. The Wechsler intelligence scale for children—third edition. The Psychological Corporation; San Antonio, TX: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Wohlwill JF. The study of behavioral development. Academic Press; New York: 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Woodcock RW, Johnson MB. Woodcock-Johnson Psycho-Educational Battery – Revised. Riverside; Chicago: 1990. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.