Abstract

Research following introduction of the MDCK model system to study epithelial polarity (1978) led to an initial paradigm that posited independent roles of the trans Golgi network (TGN) and recycling endosomes (RE) in the generation of, respectively, biosynthetic and recycling routes of plasma membrane (PM) proteins to apical and basolateral PM domains. This model dominated the field for 20 years. However, studies over the past decade and the discovery of the involvement of clathrin and clathrin adaptors in protein trafficking to the basolateral PM has led to a new paradigm. TGN and RE are now believed to cooperate closely in both biosynthetic and recycling trafficking routes. Here, we critically review these recent advances and the questions that remain unanswered.

Keywords: Epithelial polarity, Sorting, Clathrin, Adaptor, Endosome

1. Introduction

The ability to generate apical and basolateral plasma membrane (PM) domains is a key property of epithelial cells, essential to carry out vectorial functions in secretion and absorption. These vectorial functions are, in turn, necessary for the maintenance of the internal medium and survival of the organism. Epithelial cells generate their strikingly polarized phenotype through an epithelial polarity program (EPP). The EPP coordinates the activity of polarity proteins (Crumbs, Par and Scribble Complexes), polarity lipids (PIP2, PIP3) and positional information provided by cell–cell and cell–adhesion molecules to assemble epithelial-specific tight junctions, cytoskeletal re-arrangements and a Polarized Trafficking Machinery [1]. The Polarized Trafficking Machinery achieves the major goal of the EPP, i.e. to localize different proteins at the apical and basolateral domains of the PM, by sorting newly synthesized proteins into distinct Biosynthetic Routes (Fig. 1A), and endocytic receptors into distinct Recycling/transcytotic Routes (Fig. 1B), to perform key metabolic functions for the cell or the organism at apical or basolateral domains of the PM.

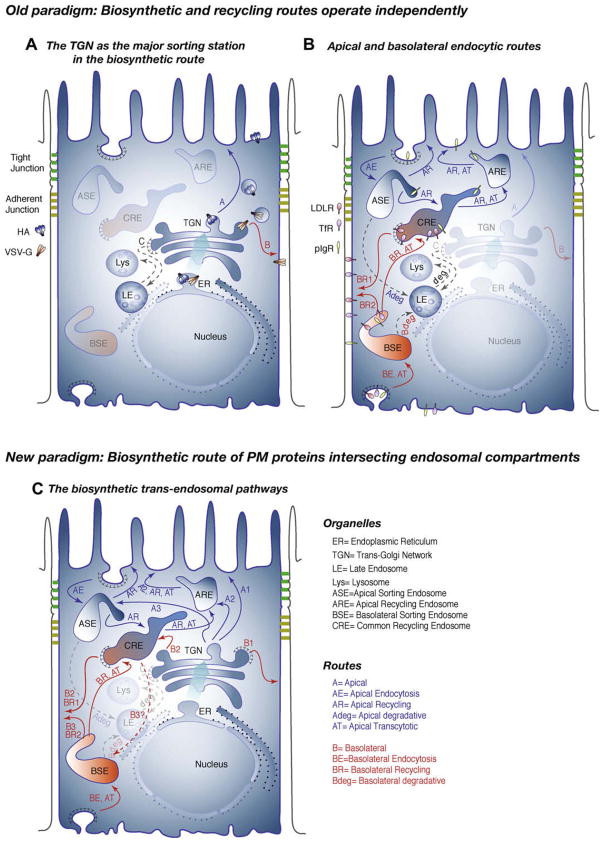

Fig. 1.

Biosynthetic and recycling routes in MDCK cells: the new paradigm. (A and B) The early paradigm. Early studies suggested the concept that biosynthetic and recycling routes of plasma membrane (PM) proteins were totally segregated, with separate sorting centers. Studies with viral envelope glycoproteins as model PM proteins suggested the concept that the TGN was the major sorting station in the biosynthetic route. Here, apical and basolateral PM proteins were sorted into different carrier vesicles that were then targeted to and fused with the corresponding PM domains (routes A and B). Only lysosomal hydrolases (route C) and some receptors involved in immunological defense were believed to use a direct route from TGN to endosomes. Recycling PM proteins (e.g. low-density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR), TfR) are internalized into separate sets of apical and basolateral sorting endosomes (ASE and BSE), where they are segregated from soluble proteins targeted to late endosomes (LE) and the degradation (deg) pathway in lysosomes (Lys). They are then mixed in deeper common recycling endosomes (CRE), the main sorting center in the recycling route, and sorted into different recycling routes to the apical and basolateral PM (routes AR and BR1). The apical recycling route includes an intermediate compartment called the apical recycling endosome (ARE), which is also an intermediate in the apical transcytotic (AT) route of the pIgR. A fast basolateral recycling route was also described from BSE (route BR2). (C) The new paradigm. Studies in the past decade have established the existence of a variety of routes followed by newly synthesized PM proteins to the different sets of apical and basolateral endosomes. Many basolateral proteins are transported (via route B2) to CRE (e.g. VSVG, TfR in recently polarized MDCK) where they are sorted to the basolateral membrane (route BR1). Other PM proteins (e.g. LDLR, TfR in fully polarized MDCK) may bypass this compartment presumably using a direct route from TGN to PM (route B1). A route from CRE to BSE (route B3?) remains hypothetical and has been proposed for pIgR. Apical proteins can follow a route that traverses ARE (e.g. endolyn; route A2) or ASE (e.g. influenza hemagglutinin (HA); route A3).

The first glimpse on how newly synthesized proteins are sorted in epithelial cells was provided by studies carried out before the cloning era. These studies used the envelope glycoproteins of RNA viruses that bud asymmetrically from polarized MDCK monolayers in vitro, as model apical and basolateral PM proteins [2–4]. They demonstrated that newly synthesized apical (influenza hemagglutinin (HA)) and basolateral (vesicular stomatitis virus G (VSVG)) proteins were synthesized at the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), transported to the Golgi apparatus and sorted at the trans Golgi network (TGN), into different populations of transport vesicles that fused with the corresponding PM domains (reviewed in [5]) (Fig. 1A).

Parallel studies in MDCK and other epithelial cell lines (e.g. human intestinal cell line Caco-2) demonstrated that epithelial cells possess an extensive endosomal system that can internalize as much as 40% of the PM per hour [6] (Fig. 1B) and can sort recycling and transcytosing PM proteins from soluble proteins targeted for degradation (reviewed by [7]). The individual routes followed by endocytic receptors such as transferrin receptor (TfR) and low-density lipoprotein receptor (LDLR) and the transcytotic polyimmunoglobulin receptor (pIgR) have been documented in elegant live imaging experiments [8,9]. These experiments showed that internalized apical and basolateral PM proteins are segregated from soluble proteins targeted for lysosomal degradation [10] in apical and basolateral sorting endosomes1 (ASE and BSE), also called Apical and Basolateral Early Endosomes (AEE or BEE), and are mixed in deeper common recycling endosomes (CRE) where they are sorted into different apical and basolateral recycling routes (see Refs. [9,12]. The apical recycling route includes an additional compartment, the apical recycling endosome (ARE) [13], an apical pericentriolar structure with a pH more neutral than CRE [8] that is also involved in basolateral-to-apical transcytosis [13,14] and the apical biosynthetic route [15] (reviewed by [16]). Functionally, BSE and CRE are defined as the compartments reached by basolaterally added transferrin (Tf) after 2.5 and 25 min, respectively [17]. A substantial fraction of Tf internalized into BSE (65%) quickly returns to the basolateral surface while the remaining 35% reaches CRE and accumulates there at steady state since the recycling kinetics from this compartment are slower than those of BSE [18]. A subset of receptors, such as low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1 (LRP1), rapidly recycles from BSE using a specific sorting machinery provided by a sorting nexin [19]. CRE is also reached by apical PM proteins [8,9,12] and thus is the major sorting site for apical and basolateral PM proteins in the endocytic route. For 20 years, this recycling route was believed to operate largely independently of the biosynthetic route, which utilized the TGN as its major sorting compartment [20]. However, work over the past decade has demonstrated that newly synthesized PM proteins may move from the TGN to RE, where they are efficiently sorted into apical and basolateral transport routes (Fig. 1C).

2. The trans-endosomal route for newly synthesized PM proteins

Trafficking routes between TGN and endosomes (and vice versa) have long been described but were believed to be specialized transport routes for lysosomal proteins via mannose 6-phosphate receptor (M6PR) [21] or for PM receptors involved in immunological defense, such as histocompatibility class II antigen-invariant chain complexes [22]. However, biochemical studies over the past decade have provided growing evidence for the participation of endosomal compartments in biosynthetic trafficking of PM proteins in both yeast [23] and mammalian cells (for recent reviews see [15,24]. In MDCK cells, radioactive pulse-chase and cell fractionation experiments [13,25,26] detected newly synthesized proteins in endosomal fractions before arrival at the cell surface. More recently, additional evidence for the trans-endosomal route has emerged from endosomal ablation experiments [27–30], live-cell imaging [28,31,32] and quantitative confocal microscopy [33] and polarized trafficking assays for newly synthesized and recycling PM proteins [34]. Proteins detected in endosomal compartments during biosynthetic delivery include basolateral proteins such as TfR [26,31,34], asialoglycoprotein receptor (AGPR) [25,35], pIgR [27], VSVG protein [28,31,34] and E-cadherin [30,32], and apical proteins such as p75 neurotrophin receptor, endolyn, HA, glycosyl-phosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchored proteins [29] and the intestinal hydrolases sucrase-isomaltase and lactase-phlorizin hydrolases [33].

Initial reports supporting the trans-endosomal route were received with skepticism as they did not define precisely the nature of the endosomal compartments involved and EM [36] and early live imaging studies following green fluorescent protein (GFP)-tagged PM proteins [37–39] failed to detect trans-endosomal trafficking. Skepticism was compounded by the fact that the conclusions from biochemical pulse-chase experiments and cell fractionation required the isolation of pure endosomal populations, an experimentally difficult task. It was also argued that, even if this trans-endosomal route existed, it might be a minor detour pathway rather that a major route to the PM. The percentage of a fast moving protein detected in a particular compartment does not necessarily reflect the proportion of the protein traveling through that compartment. An attempt to circumvent this problem has been to study the effects on biosynthetic trafficking of ablating different classes of endosomal compartments with horse radish peroxidase (HRP), used either as fluid phase endosomal marker or coupled to the appropriate membrane-bound endosomal marker (e.g. Tf-HRP), followed by treating the cells with diamino benzidine and H2O2 to induce the formation of an insoluble precipitate. The method was originally introduced to purify endosomes based on density shift [40] and was modified by Apodaca et al. [13] to isolate apical endosomal compartments and by Orzech et al. [27] to study the involvement of endosomes in biosynthetic basolateral traffic of pIgR. Examples of endosomal ablation include incubation of MDCK cells with HRP, which reach mainly early endosomes but not CRE or ARE, or with membrane-bound ligands such as Tf-HRP or wheat germ agglutinin (WGA) coupled to HRP (WGA-HRP) added either apically or basolaterally for different times to reach ASE (or AEE), BSE (or BEE) or CRE [17,27–29]. For instance, basolaterally added Tf-HRP for 5 or 20 min is used to label BSE or CRE [17,28], while apically added WGA-HRP for 15 min is used to label ASE (or AEE) but not ARE [29]. The arrival of basolateral and apical PM proteins at the respective PM domain is then followed biochemically using pulse-chase and surface biotinylation, flow-cytometry or imaging of GFP-tagged PM proteins. These experiments have shown that ablation of CRE with basolaterally loaded Tf-HRP selectively inhibited (85%) the basolateral delivery of VSV G protein [28] but not the apical delivery of influenza HA or endolyn [29]. By contrast, the apical delivery of HA and a GPI-anchored version of endolyn was inhibited (~50%) by ablation of ASE (or AEE) with WGA-HRP [29]. Interestingly, the apical trafficking of p75 neurotrophin receptor (p75) or endolyn (anchored normally via a transmembrane domain) was not affected by ablation of either CRE or ASE (or AEE), but was inhibited by expression of dominant negative myosinVb tail, believed to be involved in transport from ARE to the apical membrane [29]. These experiments suggest that different PM proteins migrate through specific endosomal compartments before arrival to their respective PM domain.

However, ablation experiments have limited resolution and are not free of artifacts, leading to potential interpretation problems. Early experiments showed that the basolateral route of pIgR is sensitive to inhibition by endosome ablation with WGA-HRP added apically and by HRP added basolaterally, interpreted at that moment as biosynthetic trafficking through CRE or ARE and BEE [27]. These initial experiments do not allow to resolve the route followed by pIgR towards BEE (e.g. direct from the TGN or indirect via CRE?) and more recent evidence suggested that apically added WGA-HRP affects ASE but neither ARE nor CRE [27]. Furthermore, Henry and Sheff reported that RE ablation with Tf-HRP resulted in mis-sorting of newly synthesized VSVG to the apical plasma membrane rather than in the entrapment of the protein at RE [17] reported by other studies [28,29]. Hence, this type of experiment, they reasoned, might not allow one to discern between two very different conclusions: (i) the cargo itself traverses the ablated compartment or (ii) the cargo is blocked at a proximal compartment, e.g. the TGN, because an essential component of the TGN sorting machinery (in this example) is trapped in the ablated endosomal compartment and cannot recycle to the TGN. Thus, they suggest that ablation experiments may have indirect effects on trafficking and must be interpreted with caution.

Given the problems associated with pulse-chase/cell fractionation and endosomal ablation approaches, the most direct approach to identify a trans-endosomal route for a given PM protein is quantitative live-cell imaging in combination with physiologically relevant strategies to block or interfere the function of a particular group of endosomes. To date, two main approaches, based on temperature-sensitive trafficking blocks, have been utilized to follow the fate of GFP-tagged cargo proteins previously accumulated at the ER or the TGN: (i) ER block using temperature sensitive (ts) VSVG-GFP: ts VSVG reversibly accumulates in the ER at 39 °C; a luminal patch in VSVG is responsible for the temperature sensitivity and can be modularly coupled to a variety of cytoplasmic domains of different basolateral proteins to study their intracellular routing [41] (ii) TGN block at 20 °C: a given GFP-tagged apical or basolateral protein expressed by vector microinjection is accumulated at the TGN using the 20 °C temperature block and then released by temperature shift to follow the post-TGN trafficking [42,43]. A major difficulty in assessing transport from TGN to RE is the fact that CRE are very closely apposed to the TGN in the perinuclear region and passage through CRE can be very fast. Thus, initial application of this approach to study the transport of VSVG-GFP from TGN to RE was not quantitative [28] and therefore failed to measure the magnitude of this process. One solution to this problem was the utilization of techniques to acutely inhibit the machinery involved in exit of basolateral proteins from RE: this approach is discussed in detail below [31].

3. Apical and basolateral sorting signals are required for polarized trafficking

The almost simultaneous discovery of apical and basolateral signals in late 1980s and early 1990s demonstrated that transport to the plasma membrane of both apical and basolateral proteins was signal-mediated. Early transfection experiments in MDCK cells suggested that influenza HA and VSV G protein had sorting information within their anchoring or cytosolic domains [44–46]. Since then, considerable progress has been made in understanding the nature of apical and basolateral sorting signals [5]. Apical sorting signals involve information contained in either the luminal (N-glycans, O-glycans), membrane-bound (GPI, transmembrane domain of HA) or cytoplasmic (dynein binding sites in rhodopsin) domains of the cargo protein [15]. Functional expression of apical information can require [47] or be independent of glycosylation [48,49]. The sorting roles of carbohydrates and the participation of sorting lectins in the apical pathway remain relatively unknown [50,51], although some important progress has recently taken place [15]. Basolateral signals and their decoding mechanisms are better understood. Simple motifs contained in the cytoplasmic domain of the cargo protein, most frequently similar to tyrosine – (YxxΦ; Φ is a bulky hydrophobic residue) or dileucine – based endocytic signals (Table 1) direct basolateral sorting [52–59]. In spite of their similarity with endocytic signals, sometimes collinear with them [19,57,60], tyrosine motifs in basolateral sorting signals often do not have the ability to promote internalization at the PM. This is the case with the distal basolateral sorting signal of the LDLR and the sorting signal of VSVG protein [55,56]. Other basolateral signals are constituted by single leucine/acidic patch motifs as in CD147 [61] or by sequences not yet resembling any other basolateral signal, e.g. TfR, Neural Cell Adhesion Molecule [62], pIgR [63], epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) [64], ErbB2 [65], and transforming growth factor α (TGF-α) [66].

Table 1.

Variations in basolateral sorting signals.

| Protein | Motifs | Comments | References |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||

| VSVG |

|

AP1B-dependent during biosynthetic trans-endosomal traffic through CRE. Not endocytic. Unknown adaptor at the TGN (AP3?). Sensitive to M-μ1B | [31,34,56,75,92] |

| AGPR-H1 |

|

AP1B-dependent. Biosynthetic or recycling? Endocytic. Sensitive to M-μ1B | [60,102] |

| lgp120/Lamp-1 |

|

[57,102] | |

| LDLR (proximal) |

|

Colinear with endocytic motif, but requires distal acidic residues. Low capacity BL sorting. Mediates AP1B-dependent biosynthetic traffic via CRE in mutants lacking the distal signal (LDLR-C27) | [54,55] |

| LRP1 (proximal) |

|

TGN sorting to AP1B/RE (CRE), unknown adaptor. SNX17-dependent BL recycling from BSE. Not endocytic. Somatodendritic sorting in neurons | [19] |

| LRP1 (distal) |

|

AP1B-dependent biosynthetic and recycling traffic from CRE. Endocytic. Somatodendritic sorting in neurons | [19] |

| FcRII-B2 |

|

Dileucine-based (Y not required). Endocytic. AP1B-independent. Unknown decoding machinery | [54,58,88,97] |

| E-cadherin |

|

Not endocytic. AP1B-interaction via PIPK1γ containing a YxxF motif. AP1B-dependent recycling. Unknown decoding machinery at TGN. Biosynthetic and Rab11-dependent trans-endosomal via Rabl 1 compartments. | [30,32,82,101] |

| Chloride channel-2 (ClC-2) |

|

AP1B-dependent. Biosynthetic or recycling? | [115] |

| Unconventional | |||

| LDLR (distal) |

|

Unconventional Y-based BL signal. High capacity, dominant. Directs post-TGN traffic bypassing CRE. AP1B-dependent during recycling. Insensitive to M-μ1B. Operates in biosynthetic and recycling pathways. Unknown adaptor in the TGN | [54,55,102] |

| plgR |

|

BFA-sensitive BL sorting. AP1A-dependent. AP1B undefined. Biosynthetic trans-endosomal route. BL sorting at both biosynthetic and recycling pathways | [27,63,95] |

| TfR |

|

AP1B-dependent in biosynthetic and recycling routes. Biosynthetic trans-endosomal route. GDNS signals during biosynthetic but not recycling | [81] |

| Epidermal growth factor (EGFR) |

|

Unknown decoding machinery. Distinct from VSVG | [64,68] |

| ERbB2 |

|

Bipartita. AP1B-dependent Biosynthetic or recycling? | [65] |

| CD147 |

|

Bipartitat involving single leucine. AP1B-independent. Unknown decoding machinery. | [61] |

| Transforming growth factor α (TGF-α) |

|

Bipartitita involving dileucine. AP1B-independent and Naked-2-dependent basolateral sorting | [66,99,100] |

Residues tested by site-directed mutagenesis: Red, predominant; Green, minor contribution.

Studies in perforated MDCK cells showed that basolateral signal peptides blocked selectively the transport of basolateral proteins out of the TGN [67], thus demonstrating a requirement for specific trafficking information in the basolateral routes between TGN and the PM. An extension of this approach that used membrane-permeant peptides to interfere the basolateral traffic in live cells [68], demonstrated that the TGN can discriminate between different basolateral proteins, indicating diversification of sorting-mediated basolateral pathways [31,34,69]. Interestingly, function-blocking peptides also provided evidence for the utilization of different sorting machinery and carrier vesicles for subclasses of PM proteins transported from the ER and the Golgi complex [68], presumably reflecting the function of variants in the ER exiting machinery [70].

4. Clathrin-mediated basolateral exocytosis

The similarity of basolateral sorting signals and endocytic motifs of receptors internalized by clathrin-mediated endocytosis has long suggested that clathrin might be involved in basolateral trafficking but only recently the participation of clathrin has been conclusively demonstrated. Clathrin-coated buds containing γ-adaptin had been observed both on the TGN [71] and endosomal membranes of non-polarized cells [72] and in deep endosomes of polarized MDCK cells containing TfR and pIgA cargoes [73]. These endosomal clathrin-coated domains were suspected of participating in polarized recycling as BFA treatment dispersed γ-adaptin staining and abrogated the basolateral recycling of TfR [73]. Early cell fractionation studies in non-polarized cells detected newly synthesized VSVG in clathrin-coated vesicles while en route to the PM [74] but a requirement of clathrin for such transport was not demonstrated. In MDCK cells, clathrin-coated buds containing newly synthesized VSVG were observed near the Golgi by immuno gold EM [75]. Until recently the only well accepted role of clathrin-coated vesicles in exocytosis was in the transport of lysosomal hydrolases by M6PR at the level of the TGN [21]. More recent experiments in non-polarized cells revealed that knock-down of AP1A and of the clathrin adaptor EGFR pathway substrate clone 15 (Eps15), both colocalizing at the TGN, interferes with post-TGN transport of M6PR to endosomes and VSVG protein to the PM [76]. A role of clathrin in the recycling pathway on non-polarized cells is supported by recent in vitro reconstitution assays [77] and RNAi silencing [78]. However, acute functional inactivation of clathrin by crosslinking did not inhibit recycling of TfR in CHO cells [79].

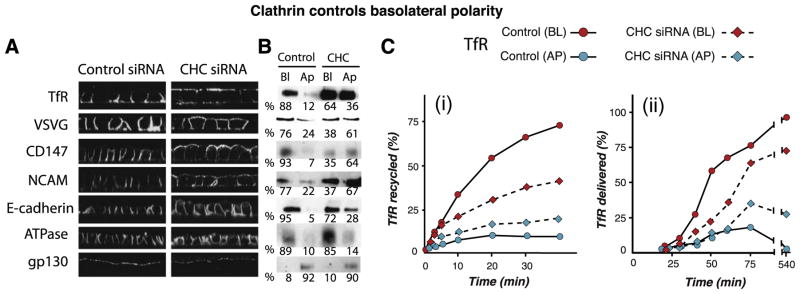

Only recently dedicated functional experiments provided the first direct evidence that clathrin is required for basolateral PM protein sorting [80] (Fig. 2). Knock-down of clathrin heavy chain in MDCK cells caused loss of basolateral polarity due to a specific defect in the transport and sorting, both in the biosynthetic and recycling routes, mostly affecting the polarity of LDLR and TfR that depend on both pathways. Strikingly, the number of affected proteins covered a broad range of basolateral signals, including TfR (tyrosine-independent signal [81]; VSVG (tyrosine signal [56]); E-cadherin (dileucine motif [82]); NCAM (tyrosine-independent signal [62]) and CD147 (single leucine plus acidic cluster signal [61]).

Fig. 2.

Clathrin plays a key role in basolateral trafficking. Knock-down experiments demonstrate a key role of clathrin in basolateral polarity. Confocal microscopy (A) and domain-selective biotinylation (B) show that PM proteins representing most known basolateral sorting signals (Table 1) are depolarized upon clathrin depletion with siRNA. Na,K-ATPase is an exception and apical proteins are not affected. Numbers in B represent the percent of each protein distributed apically (Ap) or basolaterally (Bl). (C) Recycling (i) and biosynthetic (ii) assays for TfR show that both routes are disrupted by clathrin depletion (see Deborde et al. [80] for details).

Clathrin-dependent sorting involves a variety of adaptors, the best known of which are the AP adaptors, heterotetrameric complexes that recognize cargo and mediate vesicle formation at different locations along the exocytic and endocytic routes [83,84]. AP-2 (α, β2, μ2, σ2) mediates endocytosis from the plasma membrane, while AP-1 (γ, β1, μ1, σ1), AP-3 (δ, β3, μ3, σ3) and AP-4 (ε, β4, μ4, σ4) mediate sorting at the TGN and/or endosomes. To date, the only clathrin-associated AP adaptor shown to be involved in basolateral sorting is AP1B, a variant of the AP1 expressed by some epithelial cells [85,86]. AP4, which lacks a clathrin-binding domain, has also been proposed as a basolateral sorting adaptor [87], but its role remains relatively obscure.

AP1B differs from the ubiquitous adaptor AP1A only in the possession of a different medium chain, μ1B, 79% identical to μ1A [85]. μ1B is expressed broadly by epithelial tissues and by a number of epithelial cell lines including MDCK, Caco-2, HT-29, Hec-1-A, and RL-95-2 cells. Interestingly, early studies showed that LLC-PK1 cells express apically a subset of PM proteins that are sorted basolaterally in MDCK cells [88]. LLC-PK1 cells lack AP1B [85] but when transfected with μ1B they assemble AP1B and redirected those PM proteins to the basolateral membrane, resulting in an “MDCK-like” phenotype [86,89]. Conversely, a more recent study has shown that transient or permanent knock-down of μ1B in MDCK cells results in apical expression of a subset of PM proteins, e.g. LDLR, TfR, VSV G protein, that are normally basolateral in MDCK cells. AP1B is not a general basolateral sorting adaptor in all epithelia [85]. It is absent in hepatocytes [90] and retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) [91]. One consequence of RPE cells’ lack of μ1B is that they express at their apical membrane the Coxsackie-Adenovirus Receptor (CAR), normally concentrated at the lateral PM and at Tight Junctions; this explains the normally very low adenovirus infectivity of many epithelia and the very high susceptibility of RPE to infection by these viruses [91]. Future studies are likely to find that variations in the expression of this adaptor in different epithelia may be at the core of important aspects of their physiological diversity.

5. The site of function of AP1B defines a particular trans-endosomal route

The site of function of AP1B was not as clearly apparent in the early studies and indeed it was initially proposed that AP1B worked at the TGN [86]. Non-overlapping distributions of AP1A and AP1B in MDCK cells, assessed by transfection with HA-tagged μ1A and μ1B were interpreted as localization to different TGN subdomains [75,92]. However, targeting studies in LLC-PK1 cells demonstrated that these cells (which lack AP1B) target newly synthesized LDLR correctly to the basolateral membrane but missort LDLR and TfR during post-endocytic recycling [89]. This study also reported that HA-μ1B transfected into LLC-PK1 cells colocalizes better with Tf-loaded RE rather than with TGN markers, suggesting that AP1B sorts basolateral proteins preferentially in the recycling route due to its localization at RE. Subsequent experiments confirmed this notion and provided evidence that AP1B recruits to RE two subunits of the exocyst complex (Sec8 and Exo70) [92], previously shown to participate in basolateral delivery [93]. An interesting turn in this story was provided by experiments showing that VSVG traveled through Tf-loaded endosomes after exiting the TGN [28], suggesting that AP1B might also sort newly synthesized basolateral proteins that use the trans-endosomal route. However, because the imaging and endosomal ablation assays were not totally conclusive (as discussed above), the physiological importance of the trans-endosomal route remained unclear.

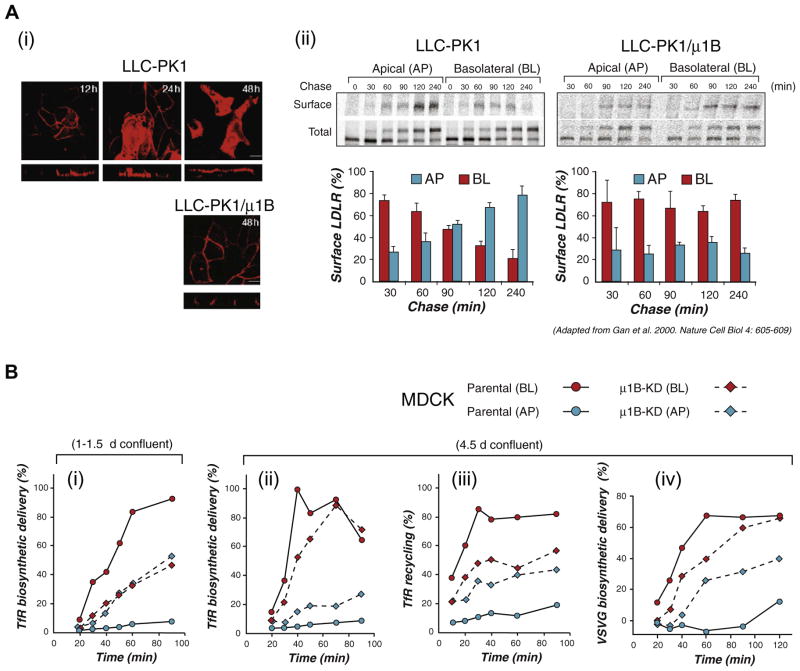

These uncertainties were addressed by AP1B knock-down studies in MDCK cells [34] (Fig. 3) and experiments with AP1B function-blocking antibodies in FRT cells [31] (Fig. 4). Cell fractionation experiments in wild type MDCK cells showed that μ1B sedimented with CRE markers but not with TGN markers and that μ1B-silenced MDCK cells missorted VSVG and TfR apically in the biosynthetic route, demonstrating that correct biosynthetic delivery of these two PM proteins was AP1B-dependent [34] (Fig. 3A–C). Interestingly, whereas biosynthetic delivery of VSVG was AP1B-dependent at all stages of MDCK cell polarization (Fig. 3B, iv), that of TfR was AP1B-dependent only in recently polarized cells (1–3 days of confluency), but not after 4.5 days in culture (Fig. 3B; i and ii), demonstrating that polarized MDCK cells developed an efficient AP1B-independent mode of delivery for TfR. The clathrin adaptor involved in this AP1B-independent route, which is also clathrin-dependent [80], is still unknown.

Fig. 3.

AP1B functions in both biosynthetic and recycling routes of some basolateral PM proteins. Targeting assays in cells lacking AP1B reveal that both basolateral biosynthetic and recycling pathways may require intact AP1B function. (A) Early work in LLC-PK1 cells, which lack AP1B, showed that newly synthesized LDLR was correctly targeted to the basolateral membrane, but relocalized to the apical surface with time, as shown by (i) confocal microscopy and (ii) biotin targeting assays. By contrast, newly synthesized LDLR is targeted basolaterally in MDCK cells and stays basolaterally with time. These experiments suggested that AP1B sorted LDLR in the recycling route (see Gan et al. [89] for details). (B) An MDCK cell line was generated in which the medium subunit of AP1B (μ1B) was knocked-down. (i) These μ1B-KD MDCK cells fail to sort human TfR, expressed via adenovirus vectors, in the biosynthetic route when they are confluent for just one day. (ii) However, biosynthetic trafficking of TfR becomes largely AP1B-independent in MDCK cells confluent for four days. (iii) Basolateral recycling of TfR is disrupted by AP1B knock-down in MDCK cells confluent for 4 days, indicating that AP1B mainly operates in the recycling route of this protein in fully polarized MDCK. (iv) The biosynthetic route of VSV G protein is disrupted in 4d-confluent μ1B-KD MDCK cells suggesting that this protein travels through CRE in fully polarized MDCK cells (see Gravotta et al. [34] for details).

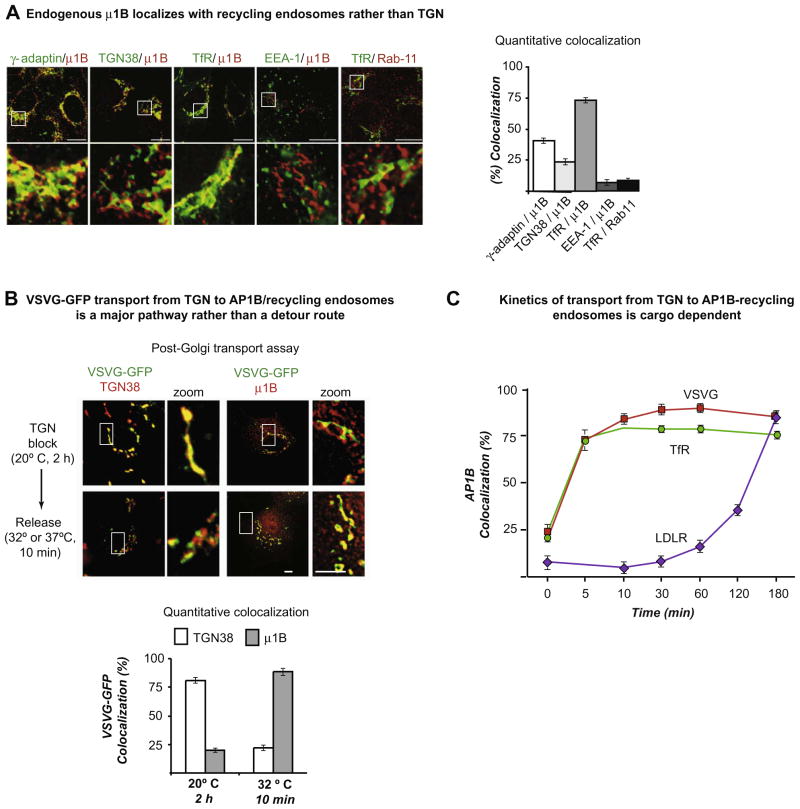

Fig. 4.

A function-blocking antibody demonstrates that AP1B sorts basolateral proteins at Recycling Endosomes. (A) Double indirect immunofluorescence of μ1B with indicated markers and quantitative colocalization analysis in epithelial FRT cells. Endogenous μ1B localizes better with TfR, a marker of RE that normally accumulates in CRE, and poorly with TGN38, EEA1, and Rab11 that are markers of TGN, sorting endosomes, and apical RE, respectively. (B and C) Post-TGN transport of basolateral cargo assessed by quantitative colocalization with TGN38 and μ1B. FRT cells were microinjected with expression vectors for green fluorescent protein (GFP)-tagged VSVG, TfR or LDLR together with the antibody against μ1B that blocks the μ1B-dependent traffic along both the biosynthetic trans-endosomal and the recycling pathways. After a 2 h incubation at 20 °C to block TGN exit, the cells were incubated for the indicated times at either 32 °C (for VSVG) or 37 °C (for TfR or LDLR) and quantitative colocalization with either TGN38 or μ1B was assessed. (B) Most of VSVG-GFP that leaves the TGN accumulates in the μ1B compartment. The same occurs with TfR-GFP but not with LDLR-GFF (not shown). (C) Kinetics of transport from the TGN to the μ1B compartment. After releasing the 20 °C block, VSVG-GFP and TfR-GFP enter the μ1B/RE compartment within 5 min and continue to accumulate there, reaching and keeping a plateau during the next 3 h, whereas the LDLR-GFP begins to accumulate at μ1B/RE compartment only after a lag period of 1 h, reflecting a block of its post-endocytic recycling through this compartment (see Cancino et al. [31] for details).

Complementary studies using a function-blocking antibody that decorated μ1B by immunofluorescence in FRT cells further reinforced these conclusions [31]. These studies showed for the first time that endogenous AP1B predominantly localizes to TfR-containing perinuclear CRE (Fig. 4A). Furthermore, pulse-chase live imaging experiments using cDNAs encoding three basolateral proteins coupled to GFP, performed in recently polarized FRT cells (1 day after reaching confluency), that employed a 20 °C block to synchronize post-TGN traffic [42,43], demonstrated that AP1B-containing perinuclear CRE, closely adjacent to the TGN, were an obligate station for newly synthesized VSVG and TfR but not for LDLR. Co-microinjection of anti-μ1B antibodies blocked biosynthetic traffic and post-endocytic recycling traffic of AP1B-dependent cargo at the CRE (Fig. 4B). Quantitative analysis of the movement of GFP-tagged PM proteins between TGN (assessed by TGN38 staining) and CRE (assessed as μ1B immunoreactivity) demonstrated that antibody addition did not block exit of any of these proteins from the TGN. Rather, it promoted accumulation of ~80% of GFP-VSVG and GFP-TfR at CRE within 5 min after exiting the TGN; the antibody also blocked LDLR exit from CRE but only ~60 min after the protein was released from the TGN, delivered to the cell surface and reinternalized into CRE by endocytosis (Fig. 2C). Because the AP1B antibody blocked none of the AP1B cargos, these experiments definitively demonstrated that AP1B works at CRE, not at the TGN.

Early studies on the sorting of LDLR and pIgR suggested that these PM proteins might use similar sorting signals at TGN and endosomes during biosynthetic delivery and post-endocytic recycling to the PM [94,95], while TfR seemed to use different motifs in these two routes [81]. The possibility that the use of similar sorting signals in both pathways might be attributed to a common sorting compartment only became apparent when evidence for the trans-endosomal pathway became available, and therefore it is relatively recent.

The experiments by Gravotta et al. [34] and by Cancino et al. [31] constitute the strongest and most definitive evidence for the basolateral sorting role of AP1B at CRE and for the physiological relevance of the trans-endosomal route to the PM. They demonstrated that: (i) AP1B sorts basolateral proteins in CRE in both bio-synthetic and recycling routes; (ii) different PM proteins have different ability to transit through RE in their biosynthetic routes; (iii) trans-endosomal traffic is not a detour pathway but a major route, reflecting an important cooperative sorting role of the TGN and CRE; (iv) MDCK develop an AP1B-independent route to the basolateral PM, likely a direct route from the TGN, as they become fully polarized. The experiments also suggest hypotheses that need to be tested by further experimental work, e.g. (i) some AP1B-dependent cargo, such as LDLR, use the same sorting signals at the TGN and RE, as suggested by early trafficking experiments [94] but different adaptors at each location; (ii) other AP1B cargo, e.g. TfR [81], use different motifs and different adaptors at each location; (iii) both classes of proteins rely on AP1B, once they have reached CRE, to be sorted towards the basolateral route [31].

6. Future directions

The advances in our knowledge of basolateral trafficking have been considerable but many open questions remain.

The functional and structural relationships between the two major sorting compartments need to be reassessed. TGN and CRE are very close and tightly interact with each other, as recently illustrated in FRT cells [31] but available data do not inform on whether transport between both compartments involves vesicles, tubular connections or maturation of TGN into CRE, all mechanisms suggested for intra-Golgi transport [96,97]. It is not even known whether transport between the TGN and CRE is sorting signal-mediated. Solving these questions will require a variety of approaches such as high resolution live imaging in 3D, correlative light-electron microscopy [98] and tomography [96,97], and competition experiments with basolateral signal peptides [67,68].

Although there is clear evidence for the passage of basolateral proteins through the CRE, there is only scant evidence for the passage of apical PM proteins through this compartment. The single most clear example is a mutant VSVG protein lacking its basolateral signal [28,99]; recent evidence suggests the passage of the enzymes sucrase-isomaltase and lactase-phlorizin hydrolases through a compartment containing Rab8 [33], which previous work has localized to CRE [17,100]. Apical pathways emerging from CRE are also evidenced by transcytosis of pIgR [8,9] and apical mis-sorting of basolateral mutants [34,89]. Indeed, many apical proteins may move to the apical surface through other endosomal compartments, e.g. ARE and ASE, as shown by endosomal ablation experiments [29]. These proteins would therefore have their major sorting site at the TGN.

Careful ultrastructural and live imaging work is needed to determine how basolateral PM proteins reaching the CRE from the PM mix with basolateral cargo arriving from the TGN. Furthermore, although clathrin has now been shown to be crucially involved in basolateral trafficking, the structural details of its participation are currently unknown. Ultrastructural and live imaging analyzes are required to determine whether conventional coated vesicles or some other form of clathrin-mediated transport is used by basolateral proteins leaving the TGN and CRE. This is particularly important because there are reports that show the basolateral protein VSVG leaving the perinuclear area in tubular transporters in non-polarized cells [38,39]. A controversial report [101] showed VSVG-RFP leaving the perinuclear region of MDCK cells in tubular elements that also contained apical cargo, GFP-GPI, and suggested, based on domain-selective transport inhibition by the mild fixative tannic acid and PI-PLC treatment, that apical transport of GPI-anchored proteins occurred through a transcytotic route. However, subsequent work using more conventional biotinylation and live imaging approaches [102,103] appeared to support the original finding that GPI-anchored proteins are delivered vectorially from the Golgi complex to the apical domain [104]. This bibliography should be reassessed taking into account the current evidence for the close proximity of TGN and CRE and their cooperation in apical-basolateral sorting. Under the new paradigm, tubules carrying trans-endosomal cargos such as VSVG to the basolateral membrane are predicted to emerge from CRE rather than the TGN.

The number of basolateral signals has been growing and the function of many, but not all of them, is dependent on clathrin [80]. What mechanisms mediate basolateral trafficking of the latter group, which includes Na,K ATPase? One possibility might be ankyrin G, recently reported to participate in post-Golgi transport to the basolateral membrane [105]. Among the basolateral proteins that use clathrin-dependent exocytic mechanisms, only a subset of them have basolateral signals that require AP1B (Table 1) [80]. Hence, clathrin adaptors other than AP1B must be involved in basolateral sorting, even recognizing the same motifs. This is particularly true in cell types such as hepatocytes and RPE, which lack AP1B [90,91]. Neurons, which also lack AP1B, segregate LRP1 to the somatodendritic region by decoding tyrosine-based motifs that in MDCK and FRT cells direct AP1B-dependent basolateral sorting [19]. Yeast two hybrid interactions have been detected between some basolateral signals and AP3 or AP4 [106] and some functional evidence suggest a role of AP4 in basolateral sorting [87] and AP3 in post-Golgi trafficking to PM in non-polarized cells [107]. Further work is necessary to clarify the role of these adaptors in biosynthetic and recycling routes for different classes of basolateral proteins. Other adaptors and accessory proteins might be also involved considering the variety of basolateral pathways and sorting mechanisms reported. Diverging pathways from the TGN to the basolateral PM include those of VSVG, EGFR, TfR, LDLR and Na/KATPase [31,34,68,69]. Basolateral sorting of TGF-α is independent of AP1B but requires Naked2 as a basolateral adaptor [108,109]. Unlike other basolateral proteins, E-cadherin appears to utilize a non-conventional recycling route to the basolateral membrane that include passage through both Tf positive RE and Rab11 positive ARE [30,32]. E-cadherin has a dileucine motif and was initially believed to traffic independently of AP1B [82], but more recently was found to interact indirectly with μ1B through type Iγ phosphatidylinositol phosphate kinase (PIPKIγ) that contains a YxxΦ motif, involving AP1B in its basolateral recycling [110].

Many questions remain on how exactly AP1B recognizes basolateral signals. Yeast 2 hybrid assays have shown that VSVG’s tyrosine-containing basolateral signal interacts with AP1B [106], but they have provided no clear answer yet to whether other “AP1B-dependent” signals, such as the tyrosine motif of LDLR (distal signal), and the tyrosine-independent motif of TfR (Table 1), interact directly or indirectly (e.g. via a piggy-back mechanism) with AP1B. Thus, tyrosine motifs are not all equal. This is shown by experiments with a mutant form of μ1B, M-μ1B, which lacks certain residues in the pocket responsible for recognition of tyrosine motifs. M-μ1B can rescue basolateral sorting in LLC-PK1 cells of only a subset of proteins, such as AGPR-H1 and Lamp-1 [111], but not VSVG [106], suggesting that the first two proteins interact with a binding site in AP1B different from the conserved pocket that interacts with tyrosine motifs in all AP adaptors [84,112]. Careful analysis of the interaction of basolateral signals and AP adaptors by yeast two hybrid and yeast three hybrid assays, in combination with carefully executed targeting assays, are necessary to elucidate the precise mechanisms of basolateral sorting-mediated by each signal and AP adaptor.

Another important question is why AP1B performs important sorting functions that cannot be replaced by AP1A, even when they differ in just a few residues of the medium (μ1) subunit. While AP1A is reportedly recruited to TGN and endosomal compartments, AP1B, as discussed above, appears to be recruited exclusively to endosomal compartments, particularly CRE. Currently, there is no information on how AP1B is recruited to CRE. Different AP proteins to different subcellular compartments can be mediated by different phosphatidylinositols [113]. AP1A’s membrane recruitment is mediated by interactions with cargo signals, not yet characterized, with activated ARF-1 and phosphatidylinositol 4 phosphate (PtdIns4P), enriched in TGN membranes [114–116]. AP1B is released from RE to the cytosol by BFA treatment and membrane-permeant basolateral sorting signal peptides of LDLR and VSVG, suggesting that ARF-1 and cargo interactions are involved in its recruitment to CRE ([31] and unpublished observations).

A group of open questions remain regarding the roles of several components of the basolateral trafficking machinery, e.g. small GTPases, exocyst, and myosin’s in AP1B-dependent and AP1B-independent routes to the basolateral PM. Rab8 [17,100], Rab10 [117] and Rab13 [99] are emerging as candidates to regulate these routes. Activated Rab8 caused mis-sorting of newly synthesized VSVG and LDLR to the apical domain and disrupted the perinuclear localization of AP1B [100] but did not alter recycling of TfR [17]. Furthermore, immunogold EM localized Rab8 more extensively to Tfn-containing recycling endosomes (RE) rather than to the TGN [100]. Rab8 seems thus to regulate basolateral delivery of AP1B-dependent cargo such as VSVG and LDLR [100] at the level of the biosynthetic route but not the recycling route [17]. Given that LDLR does not traverse AP1B/RE in its biosynthetic delivery, Rab8 might be required for returning to the TGN some crucial element of the sorting machinery that recycles between the TGN and RE [17]. Interference with Rab10 function by expression of dominant mutants inhibits biosynthetic traffic and causes apical mis-sorting of basolateral cargo such VSVG at early stages of epithelial polarization, suggesting a possible cooperation of Rab10 and Rab8 [117]. Rab13 partially colocalizes with TGN38 at the TGN and TfR receptors in RE and its mutants provoke redistribution of TGN38 and selective inhibition of VSVG and LDLR-C27 basolateral transport, without affecting FcR and LDLR-(Y28), suggesting a role in transport between TGN and RE [99]. All these GTPases likely cover different stages of the trafficking process but the specific details of how and where they function remain to be elucidated.

Several other components of the basolateral machinery also await further analysis. Exocyst components required for basolat-eral delivery of LDLR [93] might play a role related with AP1B function in RE, as AP1B promotes their recruitment to CRE [92]. Protein kinase D (PKD) has been involved in the fission events that generate basolateral carriers at the TGN [118]. Dominant-negative PKD promotes the formation of tubules at the TGN [118] but not at AP1B/RE [31], thus suggesting that other fission mediators, such as dynamin or CtBP3/BARS [119], might operate in RE. MyosinVI, a unique actin-based motor protein that is apparently recruited to CRE via Rab8 and optineurin, was also found to be required for basolateral trafficking of AP1B cargo in MDCK cells, as expression of dominant negative form caused apical mis-sorting of VSVG protein [120]. Myosin II was also shown to participate in TGN exit of basolateral proteins but it is not clear whether it plays a role in the biosynthetic or recycling route [121]. A role of AP1B in the regulation of basolateral SNARES is also emerging but, again, it is still poorly understood. Basolateral SNAREs include the t-SNARE syntaxin 4 and the v-SNARE cellubrevin, which is sensitive to cleavage by tetanus toxin [106]. Cellulobrevin localizes to the basolateral membrane and to CRE and its cleavage with tetanus toxin provoked scattering of AP1B and apical relocation of some AP1B cargos, such as TfR and a truncated version of LDLR lacking the distal sorting signal (LDLR-CT27) [106]. Unexpectedly, tetanus toxin treatment affected the steady state localization of neither VSVG nor LDLR, even when these proteins are also AP1B cargos.

In summary, the discovery of role for clathrin and clathrin adaptors in basolateral trafficking has helped understand several aspects of basolateral protein trafficking but has opened new exciting questions regarding their role in trans-endosomal and direct routes from the TGN to the basolateral membrane. Improved methodologies to carry out live imaging of basolateral proteins, in combination with cell biological and structural techniques to analyze the interaction of sorting signals with their sorting adaptors are expected to provide answers to these questions.

Acknowledgments

A.G.’s work is supported by FONDAP grant# 13980001, CONICYT grant PFB12/2007 and the Millennium Institute for Fundamental and Applied Biology (MIFAB) financed by the Ministerio de Planificación y Cooperación (MIDEPLAN) de Chile. ERB’s work was supported by NIH grants GM34107 and EY08538, by the Dyson Foundation and by the Research to Prevent Blindness Foundation.

Abbreviations

- ASE and BSE

apical and basolateral sorting endosomes

- AGPR

asialoglycoprotein receptor

- ClC-2

chloride channel-2

- CRE

common recycling endosomes

- EGFR

epidermal growth factor

- EPP

epithelial polarity program

- ER

endoplasmic reticulum

- GPI

glycosyl-phosphatidylinositol

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- HA

influenza hemagglutinin

- HRP

horse radish peroxidase

- LDLR

low-density lipoprotein receptor

- LRP1

low-density lipoprotein receptor-related protein 1

- M6PR

mannose 6-phosphate receptor

- PM

plasma membrane

- pIgR

polyimmunoglobulin receptor

- PKD

protein kinase D

- RE

recycling endosomes

- Tf

transferrin

- TfR

Tf receptor

- TGN and TGF-α

trans Golgi network and transforming growth factor α

- VSVG

vesicular stomatitis virus G

- WGA

wheat germ agglutinin

Footnotes

The nomenclature we use here to name endosomes in polarized cells is based on the nomenclature used in non-polarized cells [11] where early endosomes are classified into superficial “sorting endosomes” that sort membrane proteins from soluble proteins targeted to late endosomes and deeper “recycling endosomes” that recycle membrane proteins back to the cell surface.

References

- 1.Tanos B, Rodriguez-Boulan E. The epithelial polarity program: machineries involved and their hijacking by cancer. Oncogene. 2008;27:6939–6957. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cereijido M, Robbins ES, Dolan WJ, Rotunno CA, Sabatini DD. Polarized monolayers formed by epithelial cells on a permeable and translucent support. J Cell Biol. 1978;77:853–880. doi: 10.1083/jcb.77.3.853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rodriguez Boulan E, Sabatini DD. Asymmetric budding of viruses in epithelial monlayers: a model system for study of epithelial polarity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1978;75:5071–5075. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.10.5071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rodriguez Boulan E, Pendergast M. Polarized distribution of viral envelope proteins in the plasma membrane of infected epithelial cells. Cell. 1980;20:45–54. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(80)90233-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rodriguez-Boulan E, Musch A. Protein sorting in the Golgi complex: Shifting paradigms. Biochem Biophys Acta. 2005;1744:455–464. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2005.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.von Bonsdorff CH, Fuller SD, Simons K. Apical and basolateral endocytosis in Madin–Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells grown on nitrocellulose filters. EMBO J. 1985;4:2781–2792. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1985.tb04004.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mostov KE, Cardone MH. Regulation of protein traffic in polarized epithelial cells. Bioessays. 1995;17:129–138. doi: 10.1002/bies.950170208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang E, Brown PS, Aroeti B, Chapin SJ, Mostov KE, Dunn KW. Apical and basolateral endocytic pathways of MDCK cells meet in acidic common endosomes distinct from a nearly-neutral apical recycling endosome. Traffic. 2000;1:480–493. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2000.010606.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown PS, Wang E, Aroeti B, Chapin SJ, Mostov KE, Dunn KW. Definition of distinct compartments in polarized Madin–Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells for membrane-volume sorting, polarized sorting and apical recycling. Traffic. 2000;1:124–140. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2000.010205.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bomsel M, Prydz K, Parton RG, Gruenberg J, Simons K. Endocytosis in filter-grown Madin–Darby canine kidney cells. J Cell Biol. 1989;109:3243–3258. doi: 10.1083/jcb.109.6.3243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maxfield FR, McGraw TE. Endocytic recycling. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5:121–132. doi: 10.1038/nrm1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thompson A, Nessler R, Wisco D, Anderson E, Winckler B, Sheff D. Recycling endosomes of polarized epithelial cells actively sort apical and basolateral cargos into separate subdomains. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:2687–2697. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-09-0873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Apodaca G, Katz LA, Mostov KE. Receptor-mediated transcytosis of IgA in MDCK cells is via apical recycling endosomes. J Cell Biol. 1994;125:67–86. doi: 10.1083/jcb.125.1.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barroso M, Sztul ES. Basolateral to apical transcytosis in polarized cells is indirect and involves BFA and trimeric G protein sensitive passage through the apical endosome. J Cell Biol. 1994;124:83–100. doi: 10.1083/jcb.124.1.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weisz OA, Rodriguez-Boulan E. Apical trafficking in epithelial cells: Signals, clusters and motors. J Cell Sci. 2009 doi: 10.1242/jcs.032615. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Ijzendoorn SC, Hoekstra D. The subapical compartment: a novel sorting centre? Trends Cell Biol. 1999;9:144–149. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(99)01512-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Henry L, Sheff DR. Rab8 regulates basolateral secretory, but not recycling, traffic at the recycling endosome. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:2059–2068. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-09-0902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sheff DR, Daro EA, Hull M, Mellman I. The receptor recycling pathway contains two distinct populations of early endosomes with different sorting functions. J Cell Biol. 1999;145:123–139. doi: 10.1083/jcb.145.1.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Donoso M, et al. Polarized traffic of LRP1 involves AP1B and SNX17 operating on Y-dependent sorting motifs in different pathways. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20:481–497. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-08-0805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Griffiths G, Simons K. The trans Golgi network: sorting at the exit site of the Golgi complex. Science. 1986;234:438–443. doi: 10.1126/science.2945253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ghosh P, Dahms NM, Kornfeld S. Mannose 6-phosphate receptors: new twists in the tale. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:202–212. doi: 10.1038/nrm1050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Trowbridge IS, Collawn JF, Hopkins CR. Signal-dependent membrane protein trafficking in the endocytic pathway. Annu Rev Cell Biol. 1993;9:129–161. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cb.09.110193.001021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Harsay E, Schekman R. A subset of yeast vacuolar protein sorting mutants is blocked in one branch of the exocytic pathway. J Cell Biol. 2002;156:271–285. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200109077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Folsch H, Mattila PE, Weisz OA. Taking the scenic route: biosynthetic traffic to the plasma membrane in polarized epithelial cells. Traffic. 2009;10:972–981. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2009.00927.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Leitinger B, Hille-Rehfeld A, Spiess M. Biosynthetic transport of the asialoglycoprotein receptor H1 to the cell surface occurs via endosomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:10109–10113. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.22.10109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Futter CE, Connolly CN, Cutler DF, Hopkins CR. Newly synthesized transferrin receptors can be detected in the endosome before they appear on the cell surface. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:10999–11003. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.18.10999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Orzech E, Cohen S, Weiss A, Aroeti B. Interactions between the exocytic and endocytic pathways in polarized Madin-Darby canine kidney cells. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:15207–15219. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.20.15207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ang AL, Taguchi T, Francis S, Folsch H, Murrels JL, Pyapert M, Warren G, Mellman I. Recycling endosomes can serve as intermediates during transport from the Golgi to the plasma membrane of MDCK cells. J Cell Biol. 2004;167:531–543. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200408165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cresawn KO, Potter BA, Oztan A, Guerriero CJ, Ihrke G, Goldenring JR, Apodaca G, Weisz OA. Differential involvement of endocytic compartments in the biosynthetic traffic of apical proteins. EMBO J. 2007;26:3737–3748. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Desclozeaux M, Venturato J, Wylie FG, Kay JG, Joseph SR, Le HT, Stow JL. Active Rab11 and functional recycling endosome are required for E-cadherin trafficking and lumen formation during epithelial morphogenesis. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2008;295:C545–556. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00097.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cancino J, Torrealba C, Soza A, Yuseff MI, Gravotta D, Henklein P, Rodriguez-Boulan E, Gonzalez A. Antibody to AP1B adaptor blocks biosynthetic and recycling routes of basolateral proteins at recycling endosomes. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:4872–4884. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-06-0563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lock JG, Stow JL. Rab 11 in recycling endosomes regulates the sorting and basolateral transport of E-cadherin. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:1744–1755. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-10-0867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cramm-Behrens CI, Dienst M, Jacob R. Apical cargo traverses endosomal compartments on the passage to the cell surface. Traffic. 2008;9:2206–2220. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2008.00829.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gravotta D, Deora A, Perret E, Oyanadel C, Soza A, Schreiner R, Gonzalez A, Rodriguez-Boulan E. AP1B sorts basolateral proteins in recycling and biosynthetic routes of MDCK cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:1564–1569. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0610700104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Laird V, Spiess M. A novel assay to demonstrate an intersection of the exocytic and endocytic pathways at early endosomes. Exp Cell Res. 2000;260:340–345. doi: 10.1006/excr.2000.5006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Griffiths G, Pfeiffer S, Simons K, Matlin K. Exit of newly synthesized membrane proteins from the trans cisterna of the Golgi complex to the plasma membrane. J Cell Biol. 1985;101:949–964. doi: 10.1083/jcb.101.3.949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hedman K, Goldenthal KL, Rutherford AV, Pastan I, Willingham MC. Comparison of the intracellular pathways of transferrin recycling and vesicular stomatitis virus membrane glycoprotein exocytosis by ultrastructural double-label cytochemistry. J Histochem Cytochem. 1987;35:233–243. doi: 10.1177/35.2.3025294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hirschberg K, Miller CM, Ellenberg J, Presley JF, Siggia ED, Phair RD, Lippincott-Schwartz J. Kinetic analysis of secretory protein traffic and characterization of Golgi to plasma membrane transport intermediates in living cells. J Cell Biol. 1998;143:1485–1503. doi: 10.1083/jcb.143.6.1485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Keller P, Toomre D, Diaz E, White J, Simons K. Multicolour imaging of post-Golgi sorting and trafficking in live cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:140–149. doi: 10.1038/35055042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Courtoy PJ, Quintart J, Baudhuin P. Shift of equilibrium density induced by 3, 3′-diaminobenzidine cytochemistry: a new procedure for the analysis and purification of peroxidase-containing organelles. J Cell Biol. 1984;98:870–876. doi: 10.1083/jcb.98.3.870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lippincott-Schwartz J, Roberts TH, Hirschberg K. Secretory protein trafficking and organelle dynamics in living cells. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2000;16:557–589. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.16.1.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kreitzer G, Marmorstein A, Okamoto P, Vallee R, Rodriguez-Boulan E. Kinesin and dynamin are required for post-Golgi transport of a plasma-membrane protein. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:125–127. doi: 10.1038/35000081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kreitzer G, Schmoranzer J, Low SH, Li X, Gan Y, Weimbs T, Simon SM, Rodriguez-Boulan E. Three-dimensional analysis of post-Golgi carrier exocytosis in epithelial cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2003;5:126–136. doi: 10.1038/ncb917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gottlieb TA, Gonzalez A, Rizzolo L, Rindler MJ, Adesnik M, Sabatini DD. Sorting and endocytosis of viral glycoproteins in transfected polarized epithelial cells. J Cell Biol. 1986;102:1242–1255. doi: 10.1083/jcb.102.4.1242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gonzalez A, Rizzolo L, Rindler M, Adesnik M, Sabatini DD, Gottlieb T. Nonpolarized secretion of truncated forms of the influenza hemagglutinin and the vesicular stomatitus virus G protein from MDCK cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:3738–3742. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.11.3738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sabatini DD. In awe of subcellular complexity: 50 years of trespassing boundaries within the cell. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2005;21:1–33. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.21.020904.151711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fiedler K, Simons K. The role of N-glycans in the secretory pathway. Cell. 1995;81:309–312. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90380-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Marzolo MP, Bull P, Gonzalez A. Apical sorting of hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) is independent of N-glycosylation and glycosylphosphatidylinositol-anchored protein segregation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:1834–1839. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.5.1834. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bravo-Zehnder M, Orio P, Norambuena A, Wallner M, Meera P, Toro L, Latorre R, Gonzalez A. Apical sorting of a voltage- and Ca2+-activated K+ channel alpha – Subunit in Madin–Darby canine kidney cells is independent of N-glycosylation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:13114–13119. doi: 10.1073/pnas.240455697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rodriguez-Boulan E, Gonzalez A. Glycans in post-Golgi apical targeting: sorting signals or structural props? Trends Cell Biol. 1999;9:291–594. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(99)01595-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Potter BA, Hughey RP, Weisz OA. Role of N- and O-glycans in polarized biosynthetic sorting. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2006;290:C1–C10. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00333.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brewer CB, Roth MG. A single amino acid change in the cytoplasmic domain alters the polarized delivery of influenza virus hemagglutinin. J Cell Biol. 1991;114:413–421. doi: 10.1083/jcb.114.3.413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hunziker W, Harter C, Matter K, Mellman I. Basolateral sorting in MDCK cells requires a distinct cytoplasmic domain determinant. Cell. 1991;66:907–920. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(91)90437-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Matter K, Yamamoto EM, Mellman I. Structural requirements and sequence motifs for polarized sorting and endocytosis of LDL and Fc receptors in MDCK cells. J Cell Biol. 1994;126:991–1004. doi: 10.1083/jcb.126.4.991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Matter K, Hunziker W, Mellman I. Basolateral sorting of LDL receptor in MDCK cells: the cytoplasmic domain contains two tyrosine-dependent targeting determinants. Cell. 1992;71:741–753. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90551-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Thomas DC, Brewer CB, Roth MG. Vesicular stomatitis virus glycoprotein contains a dominant cytoplasmic basolateral sorting signal critically dependent upon a tyrosine. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:3313–3320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Geffen I, Fuhrer C, Leitinger B, Weiss M, Huggel K, Griffiths G, Spiess M. Related signals for endocytosis and basolateral sorting of the asialoglycoprotein receptor. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:20772–20777. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hunziker W, Fumey C. A di-leucine motif mediates endocytosis and basolateral sorting of macrophage IgG Fc receptors in MDCK cells. EMBO J. 1994;13:2963–2969. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06594.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Matter K, Mellman I. Mechanisms of cell polarity: sorting and transport in epithelial cells. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1994;6:545–554. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(94)90075-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Honing S, Hunziker W. Cytoplasmic determinants involved in direct lysosomal sorting, endocytosis, and basolateral targeting of rat lgp120 (lamp-I) in MDCK cells. J Cell Biol. 1995;128:321–332. doi: 10.1083/jcb.128.3.321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Deora AA, Gravotta D, Kreitzer G, Hu J, Bok D, Rodriguez-Boulan E. The basolateral targeting signal of CD147 (EMMPRIN) consists of a single leucine and is not recognized by retinal pigment epithelium. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:4148–4165. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-01-0058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Le Gall AH, Powell SK, Yeaman CA, Rodriguez-Boulan E. The neural cell adhesion molecule expresses a tyrosine-independent basolateral sorting signal. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:4559–4567. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.7.4559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Aroeti B, Kosen PA, Kuntz ID, Cohen FE, Mostov KE. Mutational and secondary structural analysis of the basolateral sorting signal of the polymeric immunoglobulin receptor. J Cell Biol. 1993;123:1149–1160. doi: 10.1083/jcb.123.5.1149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.He C, Hobert M, Friend L, Carlin C. The epidermal growth factor receptor juxtamembrane domain has multiple basolateral plasma membrane localization determinants, including a dominant signal with a polyproline core. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:38284–38293. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104646200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dillon C, Creer A, Kerr K, Kumin A, Dickson C. Basolateral targeting of ERBB2 is dependent on a novel bipartite juxtamembrane sorting signal but independent of the C-terminal ERBIN-binding domain. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:6553–6563. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.18.6553-6563.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dempsey PJ, Meise KS, Coffey RJ. Basolateral sorting of transforming growth factor-alpha precursor in polarized epithelial cells: characterization of cytoplasmic domain determinants. Exp Cell Res. 2003;285:159–174. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4827(03)00035-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Musch A, Xu H, Shields D, Rodriguez-Boulan E. Transport of vesicular stomatitis virus G protein to the cell surface is signal mediated in polarized and nonpolarized cells. J Cell Biol. 1996;133:543–558. doi: 10.1083/jcb.133.3.543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Soza A, Norambuena A, Cancino J, de la Fuente E, Henklein P, Gonzalez A. Sorting competition with membrane-permeable peptides in intact epithelial cells revealed discrimination of transmembrane proteins not only at the trans-Golgi network but also at pre-Golgi stages. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:17376–17383. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M313197200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Farr GA, Hull M, Mellman I, Caplan MJ. Membrane proteins follow multiple pathways to the basolateral cell surface in polarized epithelial cells. J Cell Biol. 2009;186:269–282. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200901021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Miller EA, Beilharz TH, Malkus PN, Lee MC, Hamamoto S, Orci L, Schekman R. Multiple cargo binding sites on the COPII subunit Sec24p ensure capture of diverse membrane proteins into transport vesicles. Cell. 2003;114:497–509. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00609-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Robinson MS. Cloning and expression of gamma-adaptin, a component of clathrin-coated vesicles associated with the Golgi apparatus. J Cell Biol. 1990;111:2319–2326. doi: 10.1083/jcb.111.6.2319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Le Borgne R, Griffiths G, Hoflack B. Mannose 6-phosphate receptors and ADP-ribosylation factors cooperate for high affinity interaction of the AP-1 Golgi assembly proteins with membranes. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:2162–2170. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.4.2162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Futter CE, et al. In polarized MDCK cells basolateral vesicles arise from clathrin-gamma-adaptin-coated domains on endosomal tubules. J Cell Biol. 1998;141:611–623. doi: 10.1083/jcb.141.3.611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rothman JE, Bursztyn-Pettegrew H, Fine RE. Transport of the membrane glycoprotein of vesicular stomatitis virus to the cell surface in two stages by clathrin-coated vesicles. J Cell Biol. 1980;86:162–171. doi: 10.1083/jcb.86.1.162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Folsch H, Pypaert M, Schu P, Mellman I. Distribution and function of AP-1 clathrin adaptor complexes in polarized epithelial cells. J Cell Biol. 2001;152:595–606. doi: 10.1083/jcb.152.3.595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Chi S, Cao H, Chen J, McNiven MA. Eps15 mediates vesicle trafficking from the trans-Golgi network via an interaction with the clathrin adaptor AP-1. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:3564–3575. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-10-0997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Li J, Peters PJ, Bai M, Dai J, Bos E, Kirchhausen T, Kandror KV, Hsu VW. An ACAP1-containing clathrin coat complex for endocytic recycling. J Cell Biol. 2007;178:453–464. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200608033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hinrichsen L, Harborth J, Andrees L, Weber K, Ungewickell EJ. Effect of clathrin heavy chain- and alpha-adaptin-specific small inhibitory RNAs on endocytic accessory proteins and receptor trafficking in HeLa cells. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:45160–45170. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307290200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Moskowitz HS, Heuser J, McGraw TE, Ryan TA. Targeted chemical disruption of clathrin function in living cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2003;14:4437–4447. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-04-0230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Deborde S, Perret E, Gravotta D, Deora A, Salvarezza S, Schreiner R, Rodriguez-Boulan E. Clathrin is a key regulator of basolateral polarity. Nature. 2008;452:719–723. doi: 10.1038/nature06828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Odorizzi G, Trowbridge IS. Structural requirements for basolateral sorting of the human transferrin receptor in the biosynthetic and endocytic pathways of Madin-Darby canine kidney cells. J Cell Biol. 1997;137:1255–1264. doi: 10.1083/jcb.137.6.1255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Miranda KC, Khromykh T, Christy P, Le TL, Gottardi CJ, Yap AS, Stow JL, Teasdale RD. A dileucine motif targets E-cadherin to the basolateral cell surface in Madin-Darby canine kidney and LLC-PK1 epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:22565–22572. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M101907200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Bonifacino JS. The GGA proteins: adaptors on the move. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5:23–32. doi: 10.1038/nrm1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Owen DJ, Collins BM, Evans PR. Adaptors for clathrin coats: structure and function. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2004;20:153–191. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.20.010403.104543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ohno H, et al. Mu1B, a novel adaptor medium chain expressed in polarized epithelial cells. FEBS Lett. 1999;449:215–220. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00432-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Folsch H, Ohno H, Bonifacino JS, Mellman I. A novel clathrin adaptor complex mediates basolateral targeting in polarized epithelial cells. Cell. 1999;99:189–198. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81650-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Simmen T, Honing S, Icking A, Tikkanen R, Hunziker W. AP-4 binds basolateral signals and participates in basolateral sorting in epithelial MDCK cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:154–159. doi: 10.1038/ncb745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Roush DL, Gottardi CJ, Naim HY, Roth MG, Caplan MJ. Tyrosine-based membrane protein sorting signals are differentially interpreted by polarized Madin-Darby canine kidney and LLC-PK1 epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:26862–26869. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.41.26862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Gan Y, McGraw TE, Rodriguez-Boulan E. The epithelial-specific adaptor AP1B mediates post-endocytic recycling to the basolateral membrane. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:605–609. doi: 10.1038/ncb827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Koivisto UM, Hubbard AL, Mellman I. A novel cellular phenotype for familial hypercholesterolemia due to a defect in polarized targeting of LDL receptor. Cell. 2001;105:575–585. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00371-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Diaz F, Gravotta D, Deora A, Schreiner R, Schoggins J, Falck-Pedersen E, Rodriguez-Boulan E. Clathrin adaptor AP1B controls adenovirus infectivity of epithelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:11143–11148. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811227106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Folsch H, Pypaert M, Maday S, Pelletier L, Mellman I. The AP-1A and AP-1B clathrin adaptor complexes define biochemically and functionally distinct membrane domains. J Cell Biol. 2003;163:351–362. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200309020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Grindstaff KK, Yeaman C, Anandasabapathy N, Hsu SC, Rodriguez-Boulan E, Scheller RH, Nelson WJ. Sec6/8 complex is recruited to cell-cell contacts and specifies transport vesicle delivery to the basal-lateral membrane in epithelial cells. Cell. 1998;93:731–740. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81435-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Matter K, Whitney JA, Yamamoto EM, Mellman I. Common signals control low density lipoprotein receptor sorting in endosomes and the Golgi complex of MDCK cells. Cell. 1993;74:1053–1064. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90727-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Aroeti B, Mostov KE. Polarized sorting of the polymeric immunoglobulin receptor in the exocytotic and endocytotic pathways is controlled by the same amino acids. EMBO J. 1994;13:2297–2304. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06513.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Trucco A, et al. Secretory traffic triggers the formation of tubular continuities across Golgi sub-compartments. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6:1071–1081. doi: 10.1038/ncb1180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Marsh BJ, Volkmann N, McIntosh JR, Howell KE. Direct continuities between cisternae at different levels of the Golgi complex in glucose-stimulated mouse islet beta cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:5565–5570. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401242101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Polishchuk RS, Polishchuk EV, Marra P, Alberti S, Buccione R, Luini A, Mironov AA. Correlative light-electron microscopy reveals the tubular-saccular ultrastructure of carriers operating between Golgi apparatus and plasma membrane. J Cell Biol. 2000;148:45–58. doi: 10.1083/jcb.148.1.45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Nokes RL, Fields IC, Collins RN, Folsch H. Rab13 regulates membrane trafficking between TGN and recycling endosomes in polarized epithelial cells. J Cell Biol. 2008;182:845–853. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200802176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Ang AL, Folsch H, Koivisto UM, Pypaert M, Mellman I. The Rab8 GTPase selectively regulates AP-1B-dependent basolateral transport in polarized Madin-Darby canine kidney cells. J Cell Biol. 2003;163:339–350. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200307046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Polishchuk R, Di Pentima A, Lippincott-Schwartz J. Delivery of raft-associated, GPI-anchored proteins to the apical surface of polarized MDCK cells by a transcytotic pathway. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6:297–307. doi: 10.1038/ncb1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Paladino S, Pocard T, Catino MA, Zurzolo C. GPI-anchored proteins are directly targeted to the apical surface in fully polarized MDCK cells. J Cell Biol. 2006;172:1023–1034. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200507116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Hua W, Sheff D, Toomre D, Mellman I. Vectorial insertion of apical and basolateral membrane proteins in polarized epithelial cells revealed by quantitative 3D live cell imaging. J Cell Biol. 2006;172:1035–1044. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200512012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Lisanti MP, Caras IW, Gilbert T, Hanzel D, Rodriguez-Boulan E. Vectorial apical delivery and slow endocytosis of a glycolipid-anchored fusion protein in transfected MDCK cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:7419–7423. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.19.7419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Kizhatil K, Davis JQ, Davis L, Hoffman J, Hogan BL, Bennett V. Ankyrin-G is a molecular partner of E-cadherin in epithelial cells and early embryos. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:26552–26561. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703158200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Fields IC, Shteyn E, Pypaert M, Proux-Gillardeaux V, Kang RS, Galli T, Folsch H. V-SNARE cellubrevin is required for basolateral sorting of AP-1B-dependent cargo in polarized epithelial cells. J Cell Biol. 2007;177:477–488. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200610047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Nishimura N, Plutner H, Hahn K, Balch WE. The delta subunit of AP-3 is required for efficient transport of VSV-G from the trans-Golgi network to the cell surface. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:6755–6760. doi: 10.1073/pnas.092150699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Li C, Franklin JL, Graves-Deal R, Jerome WG, Cao Z, Coffey RJ. Myristoylated Naked2 escorts transforming growth factor alpha to the basolateral plasma membrane of polarized epithelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:5571–5576. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401294101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Li C, Hao M, Cao Z, Ding W, Graves-Deal R, Hu J, Piston DW, Coffey RJ. Naked2 acts as a cargo recognition and targeting protein to ensure proper delivery and fusion of TGF-alpha containing exocytic vesicles at the lower lateral membrane of polarized MDCK cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:3081–3093. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-02-0172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Ling K, Bairstow SF, Carbonara C, Turbin DA, Huntsman DG, Anderson RA. Type Igamma phosphatidylinositol phosphate kinase modulates adherens junction and E-cadherin trafficking via a direct interaction with mu 1B adaptin. J Cell Biol. 2007;176:343–353. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200606023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Sugimoto H, et al. Differential recognition of tyrosine-based basolateral signals by AP-1B subunit mu1B in polarized epithelial cells. Mol Biol Cell. 2002;13:2374–2382. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E01-10-0096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Bonifacino JS, Dell’Angelica EC. Molecular bases for the recognition of tyrosine-based sorting signals. J Cell Biol. 1999;145:923–926. doi: 10.1083/jcb.145.5.923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.De Matteis MA, Godi A. PI-loting membrane traffic. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6:487–492. doi: 10.1038/ncb0604-487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]